1. Introduction

For centuries, Poland has been an overwhelmingly Catholic country. After 1945, within the country’s new borders, there were about 23 million Catholics, which constituted 97.7% of the population (

The Catholic Church 2014). The communist authorities which ruled the country after 1945 used every method to achieve the secularization of society. One method was to limit religious investments, in particular the construction of new churches, which made them become structures of political significance. Apart from the lack of permits for the construction of new buildings, efforts were made to degrade existing churches by placing obscuring buildings in their immediate vicinity. The history of the struggle to build new churches is, therefore, a very interesting chapter in the entire history of the Catholic Church in Poland. This history proves that the course of religious architecture throughout the centuries is not only the outcome of theological, philosophical, cultural, and spatial thought but is also determined and limited by political realities and negotiations with the authorities. Nevertheless, it should be noted, that the situation of the Church in Poland was less constricted than in many other communist countries in central Europe at that time. In the German Democratic Republic and Czecho-Slovakia, the actions taken towards the secularization of the society were much more advanced and religious architecture did not develop at all (

Boryszewski 2001;

Neubert 2011).

This paper gives a unique insight into the history of the faithful’s efforts to build new centers of worship under communism and afterwards, when the political realities of the country changed. This study is based on the example of the Archdiocese of Częstochowa, which is a representative region, easily extrapolated to the whole of Poland.

The Częstochowa diocese was founded on 28 October 1925. It was created from part of the diocese of Kielce and the diocese of Włocławek. After 67 years, on 25 March 1992, the Częstochowa metropolis was established, including the archdiocese of Częstochowa and the dioceses of Radom and Sosnowiec. At that time, the Archdiocese of Częstochowa had 31 deaneries and 281 parishes. Since its inception, it has been divided into four pastoral regions: Częstochowa, Radomsko, Wieluń, and Zawiercie (

Figure 1). The area of the archdiocese is 6925 km

2 and the number of its inhabitants is 805,150 (

Archdiocese of Częstochowa 2011).

Currently, there are 312 parishes throughout the archdiocese (

Kuria Częstochowa 2021), 159 of which have parish church buildings constructed after 1945. In addition, in some parishes, there are filial churches (buildings that are part of the parish but are not its main church). There are 74 such structures across the four pastoral regions. In the Częstochowa region of the Częstochowa Archdiocese, there are 85 church buildings erected after 1945. There are 61 such facilities in the Radomsko region, 50 in Wieluń and 37 in Zawiercie (

Kuria Częstochowa 2021).

2. Methodology of Research

The analysis is based on the author’s own research conducted in the Archdiocese of Czestochowa. An inventory of the construction of each church building was made, the drawings were prepared and photographic documentation was prepared. Old drafts of churches, information about estimated yearly expenditure, and data from parish records were collected from each parish and considered. Interviews with priests, regarding the investment process, were conducted. The total area of sacral buildings, the area of the church used strictly for religious rituals and the number of active faithful were analyzed. Data was collected on over 200 churches built in the Archdiocese of Częstochowa after 1945, some of which are presented in this paper. The aim of the research was to determine the influence of the political situation in Poland on churches built after 1945.

3. The History of Sacral Architecture of the Archdiocese of Częstochowa

In the years 1945–1956, in the then Częstochowa diocese, only three churches were built from the ground up, and work on two construction sites started prior to the war was continued. In 1956, on the wave of a political thaw, ordinary Zdzisław Goliński began talks with the provincial authorities in Katowice, signaling the need to build 30 new churches in places where parishes had existed for years, and the faithful gathered most often outdoors, which was particularly troublesome in winter. Unfortunately, it was only possible to obtain a building permit for just four church buildings, which were revoked after a few months on very unreliable pretexts. In such conditions, various partial investor activities, like expanding the small existing chapels, were undertaken. Moreover, even illegal actions were considered in order to obtain new centers of worship. Some decided to construct churches without a building permit, which is evidenced by the letter from the Presidium of the National Council in Katowice to the bishop’s curia in 1959. The authorities reinforced their opinion about the religious architecture in the voivodship, within the administrative borders of the Częstochowa diocese: “

(…) Until the curia and its subordinate clergy stop (...) organizing illegal construction (...), the Presidium (...) will present a negative attitude to (...) applications for the construction of church buildings” (

Metropolitan Curia of Częstochowa 1959b). Additionally, permits were often not granted due to the lack of an existing parish in the area in question. Unfortunately, the establishment of a parish was also authorized by the same Presidium, which obviously did not tend to grant them due to the lack of a church building in the future parish. The cycle was hard to break. (

Metropolitan Curia of Częstochowa 1959a, pp. 47, 98). Thus, until 1964, no church building permits were issued. In 1965, only the burned-down church in Biała Górna was allowed to be rebuilt, and other efforts to establish new churches were ignored by the authorities. As a result, the grey area expanded, and even more illegal buildings were erected. An example of illegal religious construction is the church in Strzyżowice, erected as a farm building by a private investor. The Presidium of the National Council in Katowice wrote a letter to the bishop’s curia in 1968 stating, that the permitted farm building might have been erected as an illegal church. Doubts were raised as the “barn” had fine plaster and floors and many lighting points installed (

Metropolitan Curia of Częstochowa 1968, p. 165). In response, the curia stated that the object in question was erected as a farm building and the parish priest was legally applying for permission to adapt it for religious purposes (

Metropolitan Curia of Częstochowa 1968, p. 166). Another example of an illegal church is a building in Rzerzęczyce. In correspondence between the curia and the authorities, the bishop denied any knowledge of any violations and claimed it to be entirely at the initiative of the local faithful (

Metropolitan Curia of Częstochowa 1968, p. 206). This was the situation until 1970. After the events of December 1970, there was hope that the new party and state authorities would initiate changes in church–state relations. However, the following year, again, not a single building permit was issued. In a skillful propaganda move, the provincial authorities in Katowice issued a permit for a church in Wrzosowa near Częstochowa at the end of the year, which was bizarre because the church authorities had not applied for this church at all. Several dozen other, more needed buildings had been requested instead, including a church for the 20-thousand-strong “Tysiąclecie” district, where there was not a single center of worship for the inhabitants. In 1972, a building permit was issued for one chapel in Zawiercie. The first permit in the capital of the diocese—Częstochowa—was issued in 1973 and again it was not for a church in the district most in need—“Tysiąclecie”. This permit, after many years of very intensive efforts, was obtained three years later—in 1977. At the end of the 1970s, many years of neglect in the field of sacral investments weighed heavily on the faithful (Selection of documents 2008).

In 1956, 60% of the country’s population lived in rural areas. Between 1950 and 1984, populations in urban areas increased from 9.5 to 21.5 million. Progressing urbanization meant that more and more new churches in the cities were needed (

Cichońska et al. 2016). Therefore, the bishop of Częstochowa intensified his efforts: he sent letters to provincial and national authorities, wrote letters to be read in all parishes so that the faithful would know the situation, and also tried to put pressure on the authorities. Unfortunately, in 1979 no building permits were granted, and in 1980 only permission to build a small pre-funeral chapel was granted. The year 1980 was very significant, as it was a time of social and political changes related to the strikes which resulted in the establishment of the “Solidarity” movement. In November of 1980, as in previous years, the Częstochowa curia presented a plan for sacral construction for 1981. There were applications for the construction of nine churches in the largest urban centers of the diocese. This time, a building permit was issued for one church in the “Błeszno” district in Częstochowa. After an appeal, another facility in Sosnowiec was allowed (in the area of a former Częstochowa diocese, now outside the area of the Częstochowa Archdiocese). The following year, 1981, was a breakthrough in terms of issuing building permits. Two churches were allowed to be built in Częstochowa and one in Kuleje, as well as a chapel in the village of Nierada. Permission was also granted to build a theological seminary in Częstochowa, for which the church authorities had been applying for years. In addition, in the area that is currently outside the archdiocese of Częstochowa, one permit was obtained for the construction of a church in Będzin and two in Sosnowiec. The situation was similar in 1982, when a substantive dialogue was finally started between the state and church authorities. Out of eight proposed construction sites in the then Częstochowa province, the voivode granted preliminary permits for two: in Częstochowa and Myszków. The Katowice voivode also agreed to several of the 13 proposals presented by the curia. In the years 1985–1990, the authorities of both provinces were presented with several proposals to build churches, and permits were obtained for most of them. In 1989, considered to be the official end of communism in Poland, several dozen constructions were simultaneously carried out in the Częstochowa diocese, making up for many years of shortcomings. Since then, there have no longer been any formal obstacles in the field of sacral investments, and permits for the construction of Catholic churches have been obtained without any obstacles. However, after a great construction boom, which satisfied most of the parishes needs, the number of churches erected has significantly decreased. (

Selection of Documents 2008).

4. Stylistics of Contemporary Churches of the Archdiocese of Częstochowa

The style of sacral buildings erected after 1945 is very diverse. Buildings from the 1950s mostly show syncretism, referring to historical styles. Such are the churches of the Elevation of the Holy Cross in Częstochowa and the church of Our Lady of Succour to the Faithful in Kamyk (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

At the same time, modernist buildings were also erected. As early as 1948, a design for the Church of Divine Providence in Częstochowa was created, representing constructivism with functionalist roots. Another modernist building is the church erected in the 1960s in Biała Górna (

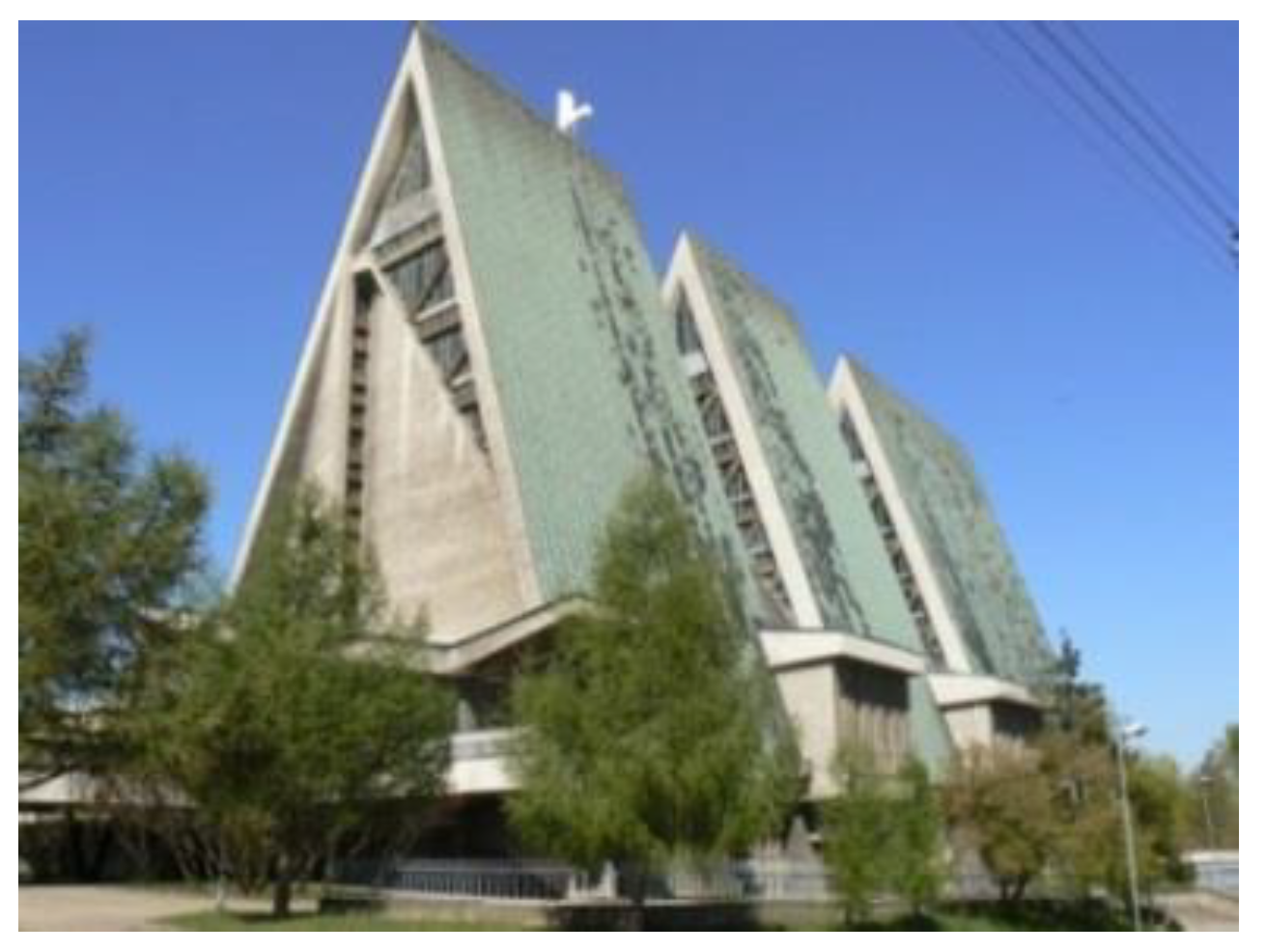

Figure 4). In the 1970s, virtually all the churches built were modernist buildings. The church in Biała Górna, despite its style, follows the traditional model of a Roman Catholic church through its elongated body and traditional tower, but the churches in Wrzosowa and Kuleje (

Figure 5) depart from this pattern completely and present very innovative forms devoid of traditional Christian symbolism.

In the 1980s, the stylistics differed significantly and, apart from the continuation of modernism, we can see structures in the regional style (

Figure 6), but also postmodern (

Figure 7) and neo-historic (

Figure 8). Unfortunately, there are also buildings whose style is difficult to define unequivocally. These are often structures that were built without designs or that differ significantly from their original designs.

After 1989, there were no longer any obstacles in applying for building permits for sacral buildings. At that time, 17 new churches were erected in the capital of the metropolis—Częstochowa. These are buildings much smaller than those built in the times of the People’s Republic of Poland, and therefore better suited to the dense parish network. Currently, there are 56 parishes in the city (

Kuria Częstochowa 2021). The style of the newest churches is also much more varied. In addition to modernist buildings (e.g., churches of St. Benedict, John, Matthew, Isaac, and Cristine—the First Martyrs of Poland, St. Maximilian Maria Kolbe, St. Jacek), buildings in the regional style were erected at that time (including St. John the Baptist, St. Jan Kanty), as well as buildings representing postmodernism (St. Kazimierz Królewicz, the unfinished church of Divine Mercy) and neo-modernism (e.g., the Church of the Blood of Christ). Similar diversity in sacral architecture existed in the remaining towns and villages of the Archdiocese of Częstochowa.

5. The Largest Churches of the Archdiocese of Częstochowa

One of the many negative effects of the restrictions on obtaining permission to build churches was the fact that when a building permit was finally obtained, church authorities decided to build a very large building because the prospect of obtaining another permit was uncertain. Sacral buildings were designed with a usable area exceeding 1000 m

2 and even 1500 m

2. Most of these structures were built between 1984–1992 (in 1988 in the whole of Poland, 173 churches, with an area of over 1500 m

2 and 66 churches with an area of more than 1000 m

2 were built) (

Cichońska et al. 2016). A fall in the number of very large structures was not recorded until 2000.

Most of these churches are now too large for the actual needs of their parishes, which have a much smaller territory. Territorially large parishes have been divided into several smaller ones, each with their own church. Due to the smaller number of parishioners, the areas of the naves and various auxiliary areas as well as the overall volume of the buildings are not fully used. Maintenance of such a large facility by a reduced number of faithful poses some financial problems. These issues will worsen over time as buildings age and wear and will require various refurbishments. Moreover, a further decline in the number of parishioners as a result of demographic changes and the secularization of society cannot be ruled out.

In the Archdiocese of Częstochowa, there are eight churches with a usable floor area of over 1000 m

2 and five of them have two levels. Six of these churches are in Częstochowa: the Church of St. Adalbert (

Figure 9), the Church of Our Lady Victorious, the Church of St. Stanislas, the Church of St. Albert Chmielowski, the Church of Sacred Heart of Jesus, the Church of blessed Ursula Ledóchowska. In addition: the Church of Virgin Mary Queen of Poland in Zawiercie and the Church of Virgin Mary Mother of the Church in Radomsko (

Figure 10).

In addition to the above-mentioned largest churches, there are many other large sacral buildings in the Archdiocese of Częstochowa, which are also worth mentioning. Examples are the churches of St. Peter and Paul, with an area of 750 m2, and St. Francis of Assisi with an area of 700 m2 that struggle with similar problems, although the scale of these problems is smaller.

In Western Europe, in the face of a decline in the number of the faithful, churches are changing their purpose. The closure of churches creates a characteristic phenomenon—churches are sold and then turned into apartments, libraries, or concert halls (

Białkiewicz 2008). An example is the adaptation of the Dutch church in Maastricht, which was converted into the Selexyz bookstore, or the conversion of a chapel into a residential house in Utrecht. As in England, where, for example, the church building in Bowness was converted into a house. In Poland, the situation is different. Churches are still needed and used for their primary purpose. In the case of large and very large churches, it may be possible to divide church buildings in such a way that the income from renting part of the church space provides the parish with sufficient funds to maintain the entire building. Demographic trends and the gradual decline in church attendance will require such measures in a relatively short time. Otherwise, church buildings, which are often works of architectural art, will fall into disrepair. Positive examples of changes in the use of sacral structures can be found in the Archdiocese of Częstochowa. The catechetical building in the church of St. Adalbert is rented to a primary school. In addition, music concerts are organized in the nave as part of the “Archisacra” festival. It seems that in the future it will be necessary to intensify efforts to change the methods of use and, for example, convert the lowest floors of two-story churches, such as St. Adalbert, into spaces for youth clubs, senior clubs, charity organizations, or artistic events.

6. Catechetical Points

In the communist era, it was easier for a Catholic community to obtain consent for the so-called catechetical center with an area of up to 600 m

2 than a typical church. Therefore, unable to obtain a building permit for the church, the parish priest would try to build such a small catechetical facility. The assumption was that there would be classrooms for religious instruction, toilets, and other auxiliary rooms. It was possible to locate a small chapel in such a building. The typical design project submitted to the authorities for consent was for several classrooms and a chapel. However during the construction phase, the chapel would be enlarged to the maximum (e.g., by connecting it with an adjacent classroom) and thus the local community gained a place where services could be held. It was a very practical solution, but it had many disadvantages. The external form of such a church, as a rule, resembled a school or residential building, and the place where the liturgy was held was the height of a classroom and often had insufficient usable space. Many such structures remained in Poland after the times of the People’s Republic of Poland. Today religion is taught in schools in Poland, so there is no longer a need for the catechetical part of the building. Often the former religious education rooms are partially or even completely unused, and the chapel, which is, in fact, a parish church, is not fully functional. Many of these facilities have been rebuilt in recent years, but are rarely fully satisfactory. Examples of such catechetical centers in the Archdiocese of Częstochowa are, among others: the Church of the Visitation of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Częstochowa (

Figure 11), the Church of St. Francis of Assisi in Blachownia, and the churches of the Immaculate Heart of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Czarny Las (

Figure 12), and St. John the Baptist in Kocin Stary (

Figure 13). There are of course more examples of this type of building and most of them do not fully meet the current parish requirements. Some use the catechetical part for commercial purposes. An example is the parish of the Visitation of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Częstochowa, where rooms are rented to a private Catholic high school. It is much more difficult in smaller towns, where most of the classrooms are empty. Finding a practical use for these facilities is a challenge for the future.

7. Filial Churches

Filial churches were built in territorially vast parishes to reduce the need for the faithful to travel to the parish church. The existence of such small structures in the area is desirable because the long distance from the church causes difficulties in reaching the services, especially for older parishioners as well as children and youth. Furthermore, other faithful are more willing to attend mass if getting to the church does not take much time and does not require troublesome travel arrangements. There are 75 filial churches in the archdiocese of Częstochowa. There are nine such buildings in the Częstochowa region. In addition, there are 28 such facilities in the Radomsko region, 25 in Wieluń, and 13 in Zawiercie. Most filial churches are found in less urbanized districts.

The research conducted by the author showed that all the filial churches were erected using the economic resources and volunteer labor of the local congregation. Most often, the plots were donated by one of the faithful or constituted communal areas. Funds were raised from the members’ congregation, and some of the materials came from donations. Sometimes different organizations participated in the construction, for example, the construction of the church of St. John the Baptist in Kocin Stary, the officers of the Volunteer Fire Department in the village made a large financial contribution and were heavily involved in construction works.

Only local building materials were used for construction, minimizing expensive transportation. Traditional technologies were used, mainly due to the relatively small size of the buildings, but also due to the low qualifications of the majority of construction workers (volunteer workers).

Thanks to the great involvement of the local community, the buildings were usually built quickly, sometimes a year was enough (e.g., the Church of St. Faustina in Lubojenka and the Church of St. Maksymilian Maria Kolbe in Borów), two years (Church of St. John the Baptist in Kocin old and the Church of St. John the Baptist in Turów), three (the chapel of St. Mary Magdalene in Huta Stara A (

Figure 14)) or a maximum of four years (St. Anthony of Padua in Władysławowo, the Church of St. Antoni of Padua between Olbrachcice and Ulesie). Rarely, construction took longer.

The finishing of the buildings of filial churches is usually quite modest. Many of them are still not finished, most often they do not have external plaster. This is a specific way to reduce construction costs. They have been used in this way for many years and it does not significantly affect their functionality. Most of the filial churches have no heating. This is due both to the financial capacity of users and real needs. These churches are used infrequently and for a short time, as the main celebrations are held in parish churches. In winter, users stay indoors in outerwear to avoid the cold. Due to the lack of heating, there is no need to increase the thermal insulation of walls, roofs, and other construction and finishing elements of buildings. So, paradoxically—the lack of thermal insulation does not increase the energy consumption of the building.

During the research, it was not possible to obtain specific data on the construction costs of individual facilities. However, it can be concluded that due to the participation of volunteers, virtually all construction works, and numerous donations in the form of materials, these costs were relatively low.

The maintenance of the facilities is based on the community work of the faithful. These are relatively new facilities, so they do not require costly renovations, and the residents carry out ongoing maintenance works free of charge. If necessary, duty hours for cleaning and decorating are organized. One of the few regular charges is electricity bills, which are not high due to the short time of use of the facility. The costs of operating the filial churches are relatively low and the local community bears them easily, saving on commuting to the parish church. Such sacral buildings bring other, non-material benefits to the inhabitants of small towns. These are sometimes the only places for collective meetings in the village, having a traditional and contemporary significance as a community building. The faithful often organize around such a center, and care for it in solidarity, set up various prayer groups, and unite around religious and community ideas.

For all of the above-mentioned reasons, filial churches can be considered very valuable for local communities due to the way they are built and operated.

8. Conclusions

After the extremely difficult years of the Polish People’s Republic for religious construction, the Catholic church in Poland inherited a large number of hastily built churches. The fear of possible revocation of a permit, uncertainty about further permits, the flourishing of the described grey area, and lack of planning related to any future catechetic needs resulted in the construction of overly large, uneconomic, and impractical churches and chapels. Moreover, it is worth mentioning, that at that time building materials were difficult to obtain and were of poor quality. Additionally, local designers and investors often had no experience in this type of construction.

Thus, the architecture of post-war churches in Poland cannot be discussed without reference to the main political background. As long as churches can be considered as a safe space for the faithful’s visible and invisible needs, and religious architecture has always been considered as the outcome of higher needs and thoughts, the knowledge of this brutal and very pragmatic reality of communistic life in Eastern Europe might question the primal assumption. The influence of politics on the size, appearance, and even presence of churches at all, was enormous. In these harsh times when erecting a church was a miracle in itself, all other requirements such as the aesthetical, theological, cultural, and symbolic, were secondary.

Therefore, the churches of the Archdiocese of Częstochowa, like the rest of the country, present a great variety of styles and functional solutions. Some of the structures show a conservative style, while others are highly innovative. Unfortunately, many buildings, for various reasons, cannot be described as relating to any architectural style. Their artistic value remains a matter of question. The filial churches took the lead in this area, as it was important that they were built in any form, and the inhabitants of small villages did not have to travel to the parish church. The structures built in 1945–1989 are the legacy of difficult times for church investors. It should be noted that the level of aesthetics of churches increases over time, churches built after 1989 look much better than those from the times of the Polish People’s Republic.

The intensive investment process lasting from the 1980s ended at the beginning of this century when the religious needs of the inhabitants of the entire archdiocese of Częstochowa seem to be satisfied. Virtually every larger town has a parish church, and filial churches were built in larger parishes.

Unfortunately, the number of church buildings did not translate into their quality. It is to be hoped that many of the existing defects will be rectified over time: churches will be thermo-renovated, and various repairs will be carried out. However, the aesthetics of most structures cannot be repaired and these churches will remain a sign of their times rather than structures that culturally, artistically, and qualitatively enhance the value of their environment.