Abstract

Although the two parallel architectural forms, Han Buddhists and the Cistercian monasteries, seem, on the surface, to be very different—belonging to different religions, different cultural backgrounds, and different ways of construction—they share many similarities in the internal institutional model of monks’ lives and the corresponding architectural core values. The worship space plays the most significant role in both monastic life and layout. In this study, the Three Temples of Guoqing Si and the Church of the Royal Abbey of Santa Maria de Poblet are used as examples to elucidate the connotations behind the architectural forms, in order to further explore how worship spaces serve as an intermediary between deities, monks, and pilgrims. Based on field research and experience of monastic life, this comparative study highlights two fundamental similarities between the Three Temples and the Church: First, both worship spaces are derived from imperial prototypes, have a similar priority of construction, occupy the most important place in both sacred venues, and both serve as a reference for the development of monastic layout. Second, both worship spaces are composed of a similar programmed functional layout, including similar space dominators as well as itineraries. Beyond the surface similarities, this article further analyzes the reasons behind the three differences found. Due to their different understanding of deities, both worship spaces show different ways of worship, images of deities, and distances towards them.

1. Introduction

1.1. Study Background and Objectives

“Typical of the plan is first of all the arrangement of its buildings in three groups. The whole layout is arranged around three longitudinal axes. The structures lying along the central one form the group which stands as the official embodiment and expression of the idea on which the existence of the whole layout is based and will contain the chief halls to which the public have access.”(Prip-Møller 1937)

Since Chinese scholars first began to investigate Buddhist architectures in China (Liang 1961), the central axis has always been considered as a key issue. From its evolution and formation (Wang and Xu 2011), speculation on the basic spatial sequence (Su 2009), space configuration (Wang and Lu 2000), and its role in the development of the whole monastic layout (Wang 2016), it has emerged as a fundamental unit in Buddhist monasteries. Therefore, it has always received great attention through records (Liang 1932), drawing (Liang and Fairbank 1984; Zhang 2012), and mapping (Wang 2011).

However, the above studies mostly discuss the central axis from a single view of architectural meaning, but rarely from its essence of religious space. As a worship space, what is the internal relationship with deities, monks, and pilgrims? How is it related to the whole layout? How is the range of worship space defined? How is the worship itinerary generated?

At the same time, we have also seen that Western as well as Japanese scholars have been consciously forced to think about the connotations of religion in the study of Chinese Buddhist monasteries, from the daily rituals of monks (Boerschmann 1912), monastic layout (Itō 1931), space functions (Sekino and Tokiwa 1926), and itinerary of worship (Prip-Møller 1937).

However, in the Western context, the worship space refers to a church in a monastery. It is worth considering the fact that the worship space in Buddhist monasteries does share some similarities with the church. Despite their apparent different appearances, relatively little research has been done to thoroughly investigate the similarities and differences in the worship spaces of Buddhist and Christian monasteries. Furthermore, how can we define the range of worship spaces in both monasticisms?

The configuration of the central axis of Buddhist monasteries has gone from being centered on the pagoda to being centered on the main hall (Liu 2007). The main hall, where the central altar of the Buddhist image is located, is regarded as the most important sacred space (Sun 2017) and the climax of the whole layout, no matter the spiritual level or the architectural level (Prip-Møller 1937). In order to make the comparative research more scientific, this article regards the entrance to the main altar in the central axis space as a complete worship space based on the religious and spatial relationship between deities, monks, and pilgrims.

With the evolution of Western monasticism (King 1999), church architecture has also gone through evolution and transformation (Braunfels 1972); however, it has always been considered and constructed in a whole volume. It has maintained the religious function (Walsh 1932) and the direction of approach from the west to the east. Furthermore, the location of the church is always set next to a cloister with a solid façade. These all contribute to the realization of the independence and integrity of the church space as a worship space.

Buddhism and Christianity have always been studied comparatively from historical (Boisvert 1992), spiritual (Henry and Swearer 1989), and religious practice (Moon 1998) aspects, but there is not enough comparative analysis to illustrate their similarities and differences in terms of their architectural aspects. Therefore, the author believes that a comparative analysis of worship spaces in Buddhist and Christian monasteries could fill this historiographic gap and provide materials and reflection for a better comprehension of the similarities and the differences between the two spaces.

Because this is a wide-ranging topic, it is better to focus on detailed cases studies; therefore, two monasteries, a Buddhist monastery, the Guoqing Monastery, and a Cistercian monastery, the Royal Abbey of Santa Maria de Poblet, have been selected to conduct a comparative analysis. The reasons for their selection will be explained in the following sections.

1.2. Research Methods and Scope

Before discussing the worship spaces in the Guoqing Monastery (hereafter Guoqing Si) and the Royal Abbey of Santa Maria de Poblet (hereafter Poblet Monastery), it is fundamental to consider the following: Why have Han Buddhist and Cistercian monastic traditions been selected as the foci of this comparative analysis?

Many religions active in the world today impress upon their followers their respective teachings and methods of practice, but not all emphasize a strict cenobitic approach. Indeed, among the three largest world religions, only Buddhism and Christianity encourage and practice cenobitic life, whilst Islam criticizes and forbids it; the Quran teaches acceptance of life, not rejection or withdrawal, and by dint of this, monasticism and asceticism are not allowed in Islam. In comparison, Buddhism and Christianity share very similar attitudes towards their cenobitic practices. However, within both Buddhism and Christianity, one can see examples of many types of cenobitic life.

Christianity originated in the Middle East, and is the largest religion in the world. It is formed of three main branches; the Catholic Church, Protestantism, and the Orthodox Church. Catholicism can be considered as the most extensive of the Christian traditions, and has had a decisive influence across Western European culture and history, particularly in Italy, France, and Spain. Within this, the Order of Cistercians is the most influential of the monastic traditions. In contrast, Buddhism originated in ancient India, and has a widespread following across Asia, particularly in east Asia, as well as a significant number of devotees in Europe, Africa, and North America. China has the largest number of Buddhist monuments and Buddhists in the world.

With Han Buddhist and Cistercian having developed globally as the main monastic traditions, specific cenobitic traditions have in turn developed within each, with some clear similarities between them. Both monasticisms derived from the hermit tradition, whereby hermits lived in deserts and followed a self-sufficient lifestyle. Adherents to both have similar pursuits for a strict and austere religious life. It is also worth considering, therefore, whether there exists a further similarity in the architectural organization of the cenobitic lifestyle.

It is undeniable that there are many differences between the architecture of Han Buddhist and Cistercian monasteries. The purpose of this research is not to simply compile a catalog of similarities and differences, but rather to shed light on the reason behind common characteristics shared by both monastic spaces. In his preface to For the Sake of the World: The Spirit of Buddhist and Christian Monasticism, Patrick G. Henry mentioned a prediction made by Arnold J. Toynbee: “It seems more meaningful to cheer on the commons than point out the difference between Buddhism and Christianity. More than forty years ago, Arnold J. Toynbee predicted that when historians in the twenty-first century write about our own, they will be more interested in the interaction between Buddhism and Christianity than in the conflict between communist and democratic systems.” (Henry and Swearer 1989). The similarity is the start point of comparison, and comparison is the structure of analysis. In the comparison procedure, one case will intrigue questions for the other that this dynamic is originally built into it. “If you analyze a single thing, you learn more about it, but it confirms itself in a way there’s no dynamic built into the procedure. ... But you reveal sameness and difference and the layering of architectural expression when you compare two works that are from different points of view, answering more or less the same problem.” (Frampton 2015).

First emerging in France in the 11th century, following the rule of Saint Benedict (Benedict of Nursia 516), Cistercian monasteries quickly expanded in Western Europe in the 12th and 13th centuries. Almost in the same period, from the 11th to 13th centuries, the Song Dynasty of China witnessed the flourishing of Chan Buddhist monasteries. These followed the Imperial Edition of the Pure Rules of Baizhang (Dehui 1335) and became the dominant form of monasticism in Asia.

As these two traditions emerged, it is worth noting that both shared similar preferences in site selection: concealed in valleys, located in wilderness remote from villages, or in selected desolate and uninhabited sites near the sea. Such selections are closely related to similar preferences in the style of religious daily life; self-sufficient and the self-sustained, desiring to maintain their lives through their own works and actions, rather than by relying upon the support of wider society. Furthermore, following from the way in which both types of monastic life developed from a hermit origin, followers must also dedicate all their time to worship, meditation, work, and reading (Table 1 and Table 2); among these, worship is the most important.

Table 1.

Daily Routine for Buddhist Monastic Life (Guoqing Si).

Table 2.

Daily Routine for Cistercian Monastic Life (Poblet Monastery).

The essence of the monastery is the spatial layout and unity of the main buildings. Indeed, the very construction of the main buildings is done in such a manner as to reflect the relationships between deities, monks, and pilgrims. Typical spaces within the monastery include worship spaces, a Dharma room or chapter room, refectories, dormitories, and meditation halls. Among these, those with highest priority are the worship spaces, and thus these are often the most complex of all. It is possible to build a larger worship space as an aspect of cenobite life1, and this can be seen in both monastic traditions. To strictly follow their monastic rules, both Buddhists and Cistercians require an ideal layout for their monasteries, with Buddhists following the Illustrated Scripture of Jetavana Vihara of Sravasti in Central India as drawn in the 7th century (Figure 1), and Cistercians following the 8th century Plan of St. Gall (Figure 2). From both ideal layouts, we can find that the axis of worship is emphasized, and a functional partition is set to delineate between deities, monks, and pilgrims (Ho 1995; Horn et al. 1979). The more central an architectural aspect is in the layout of the monastery, the more sacred; the further to the outside, the more secular. At the heart of the monastery are the temple and the church—essentially considered the residences of Buddhas and God, located in the holiest place and constructed with the highest standard. They are the largest buildings in the monastery and within them are held the most significant and ordinary liturgies.

Figure 1.

Illustrated Scripture of Jetavana Vihara of Sravasti in Central India (667).

Figure 2.

Plan of St. Gall (816).

To further explore how the layout of these areas conveys the spirit of the deities and affects the lives of monks and pilgrims, the Three Temples of Guoqing Si2 and the Church of Poblet Monastery are taken as typical cases based on a preliminary comparative study of 20 Han Buddhist Monasteries in Southern China and 20 Cistercian Monasteries of Western Europe (Wang 2021). This study conducts a parallel analysis on how the Three Temples and the Church function, which can be used as a reference for the overall development of monastic layouts. How does the layout of these monasteries serve as the medium of communication among deities, monks, and pilgrims? What kind of dominators occupy the spaces? How do they materialize into concrete functional layouts, and how are they perceived by monks and pilgrims through worship itineraries?

2. Worship Spaces in Both Monasteries

2.1. The Three Temples in Guoqing Si

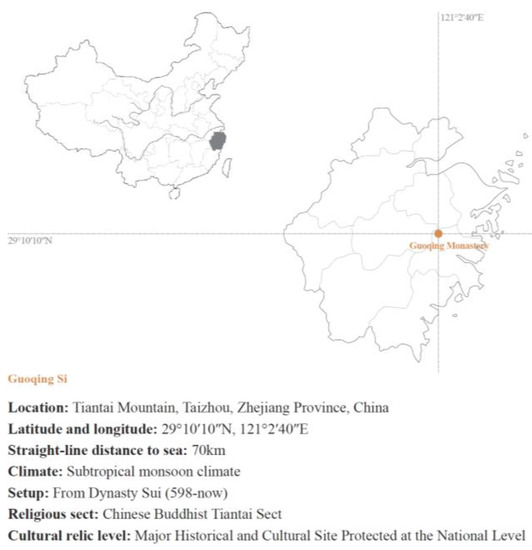

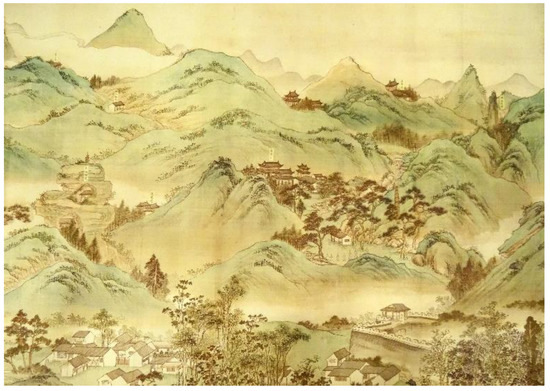

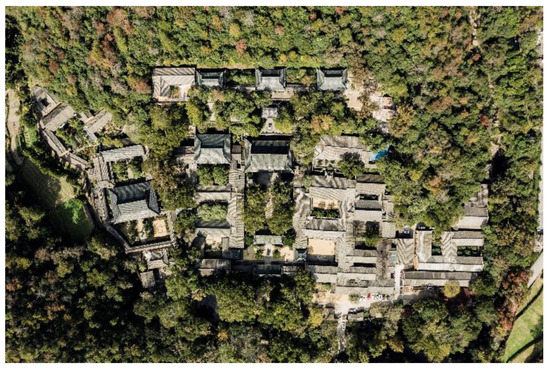

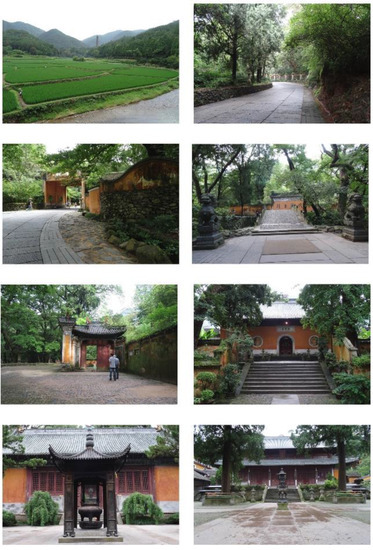

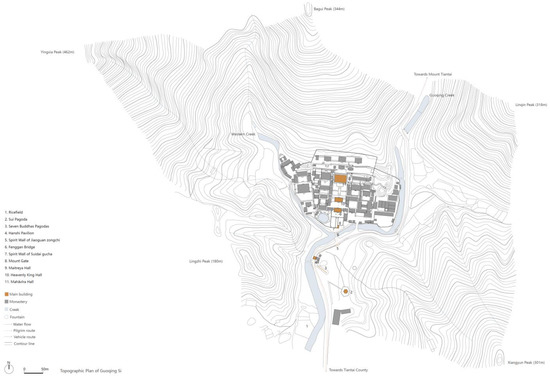

Guoqing Si is situated in Mount Tiantai, in Taizhou, Zhejiang Province (Figure 3). It was originally built in 598 during the Sui Dynasty and has witnessed more than 1400 years of history. It is the cradle of the Tiantai Buddhist sect, considered the first to evolve after the spread of Buddhism to China. The monastery is located in the valley among five peaks and is surrounded by two creeks (Zhang 1717) (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Diagram of the location of Guoqing Si.

Figure 4.

Drawing of Guoqing Si in Qing Dynasty.

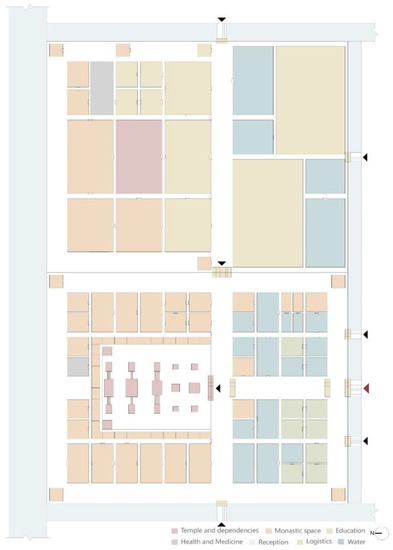

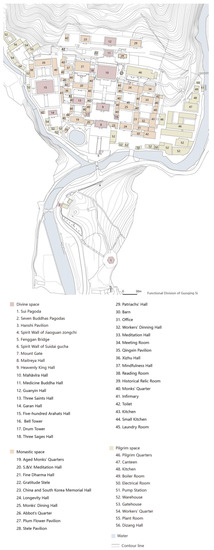

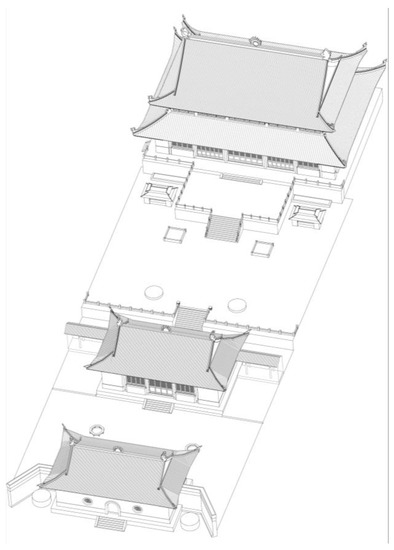

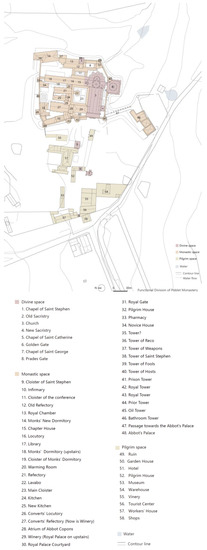

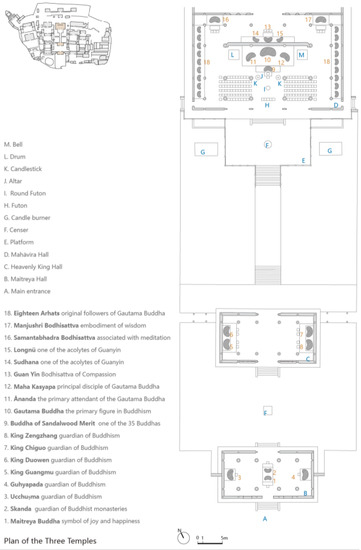

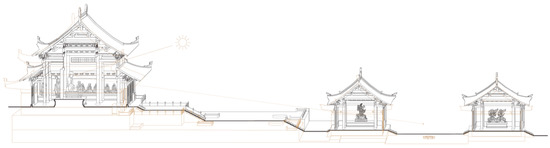

Guoqing Si covers an area of 17,501 square meters, with 22 main halls distributed in five axes. These can be separated into three main functions: divine space, monastic space, and pilgrim space (Figure 5). There are more than 60 buildings along these axes, which also perform the auxiliary function of helping to enclose the courtyard. The functional division of the monastery can be understood as the following: the western part is mainly for Buddhist rituals, sutra study, and monks’ day-to-day lives. The eastern part is mainly made of the supporting facilities for daily life at the monastery, as well as the residences of the abbot, monks, and pilgrims. From the south to the north, the buildings on the central axis are dedicated to the worship of Buddha. This includes the Three Temples. It is important to note that the use of three here is a generic term; the number may vary in different Buddhist monasteries. In Guoqing Si, the Three Temples refers to the main entrance towards the altar, comprised of the Maitreya Hall, the Heavenly King Hall, and the Mahāvīra Hall. The courtyard is called Mingtang (Bright temple), and it is an extension of the main hall space. The role of the courtyard is also reflected in its use in specific Buddhist rituals. For the purposes of comparing the sacred space of Guoqing Si to the Cistercian Church, three halls and two courtyards are considered as a whole volume (Figure 6), which is around 100 m long and around 30 m wide.

Figure 5.

Functional division of Guoqing Si.

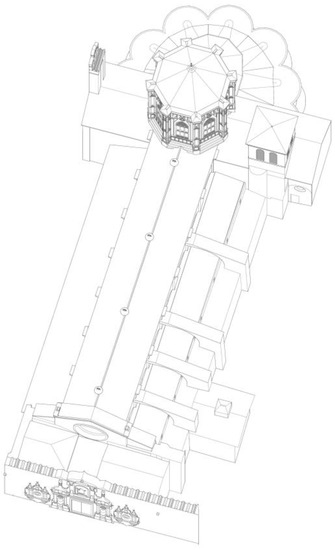

Figure 6.

Axonometric aerial view of the Three Temples.

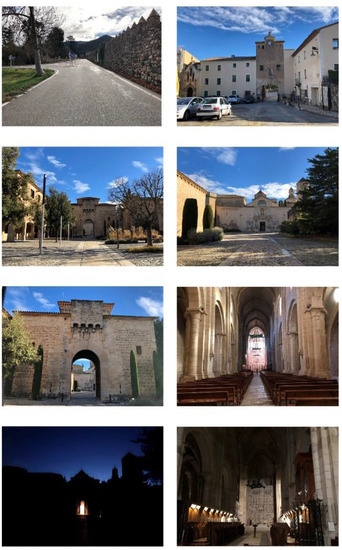

2.2. The Church in Poblet Monastery

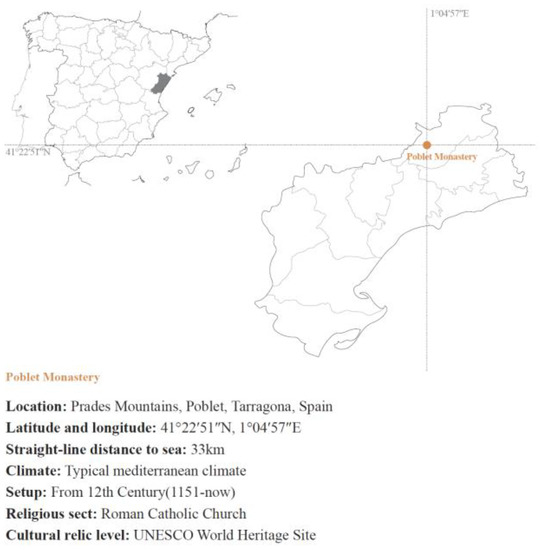

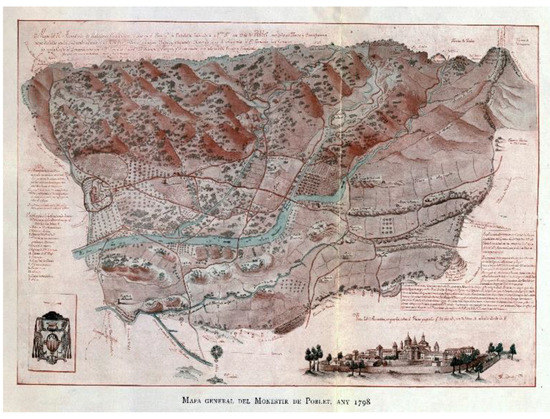

Poblet Monastery was built in 1151, and may be seen as the prototype for the Spanish Cistercian Monastery. It developed from French origin, where one can find its motherhouse, Fontfroide Monastery. Poblet Monastery is situated in the city of Vimbodí, Tarragona Province, at the foot of Mount Prade (Figure 7). It is surrounded by mountains on the east, south, and north, though the west side is open (Figure 8). Also, on the east side runs the Francolí River, which provides an abundance of high-quality water flowing from the nearby mountains. The monastery was constructed on the same land upon which the Roman house, la Granja Mitjana, previously stood (Altisent 1974).

Figure 7.

Diagram of the location of Poblet Monastery.

Figure 8.

General map of Poblet Monastery in 1798.

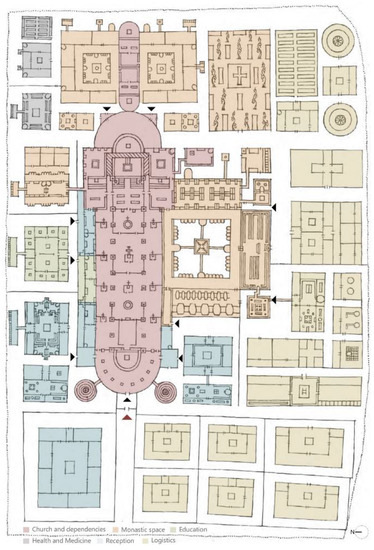

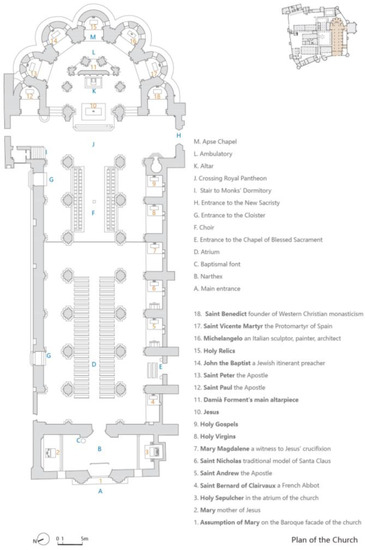

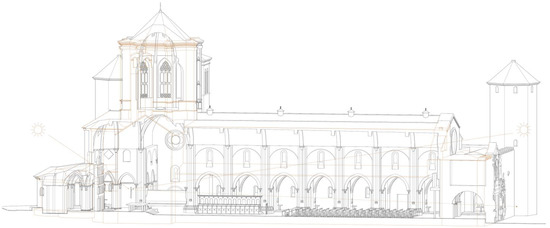

The scale of Poblet Monastery is similar to Guoqing Si, in that buildings cover an area of 18,887 square meters. It follows the typical layout of the Cistercian monastery, whereby auxiliary buildings are constructed around the Main Cloister, which includes spaces for use in a pilgrimage such as a hotel, pilgrim house, museum, warehouse, winery, and tourist center constructed between the defensive wall and the Wall of Peter IV. The Main Cloister is mainly composed of the divine space and monastic space. The Church and the New Sacristy are situated in the south side while buildings for monks are mainly set in the north side including the Chapter House, the Monks’ Dormitory, the Library, the Warming Room, the Refectory, the Kitchen, the Converts’ Locutory, and the Converts’ Refectory (Figure 9). Similar to the Three Temples, the Church occupies a volume (Figure 10) of 85 m by 21 m with a central nave and three aisles.

Figure 9.

Functional division of Poblet Monastery.

Figure 10.

Axonometric aerial view of the Church.

In two such different monasteries, both temple and church serve similar functions. It is worth considering the following two aspects: the roles of worship spaces in the entire monastic layouts, and the configuration of the internal layouts including how they connect deities, monks, and pilgrims.

3. Comparative Analysis

3.1. The Roles of Worship Spaces in the Monastic Layouts

Even though the Three Temples of Guoqing Si and the Church of Poblet Monastery were built in different countries during different periods, they share similarities in monastic layouts, space prototypes, and priority of construction within the overall structure.

3.1.1. Similar Roles in the Generation of Monastic Layouts

Each monastery takes their key space—the Three Temples at Guoqing Si and the Church at Poblet Monastery—as a reference point to develop the remainder of the spatial layout. Guoqing Si takes the Three Temples as the center point and extends the monastic layout in the east-west direction (Figure 11). Poblet Monastery extends towards the north side with the Church as the southern border (Figure 12). In addition to this, the functions of both the Three Temples and the Church are both the most important and most sacred. In the first instance, they are considered the houses of deities. Thus, they are used to hold Buddhist rituals such as the Liberation Rite of Water and Land, blessing ceremonies, holy day ceremonies such as the birthday of Śākyamuni Buddha, and the performance of religious ceremonies to help the souls of the deceased to find peace, as well as Catholic rituals like thanksgiving mass, baptism, funeral mass, marriage, forgiveness, etc. These two spaces also take the role of training schools for monks, by acting as a location where they can conduct prayers like Buddhist chanting and Christian offices, as well as teach doctrine to pilgrims. Thirdly, the spaces perform as a public spiritual place for pilgrims to visit, study, and receive great blessings and merit from the aforementioned ceremonies. In summation, both the Three Temples and the Church are comprised of three common parts: the altar and monks’ choir, space for pilgrims, and the entrance.

Figure 11.

The Three Temples as the central axis.

Figure 12.

Church as the southern border.

3.1.2. Similar Space Prototype

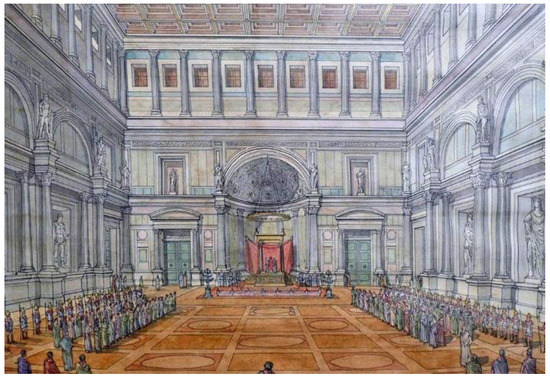

Similar layouts can be seen in the prototypes from which these designs originated. Indeed, both buildings originate from imperial architectural traditions. In the ancient world, imperial space was considered to be the most powerful space, akin to the idea of sacredness. Naturally, they became locations to imitate by both temple and church. Although there is no direct evidence to prove which specific pieces of imperial architecture these structures imitated, they have nonetheless all borrowed the concept of strict hierarchy from imperial buildings to arrange their internal spaces.

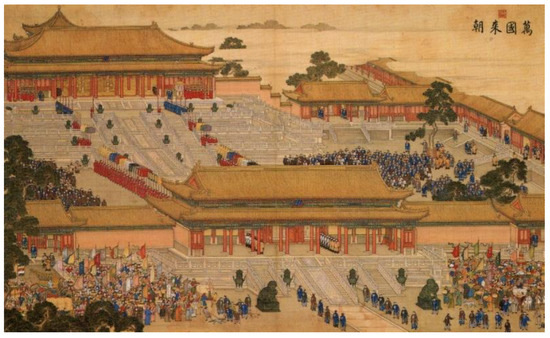

The Hall of Supreme Harmony (Taihe Dian) (Figure 13), constructed in the 15th century, is widely considered the most dignified building of the Forbidden City. Its layout set the throne at the geometric centerpoint of the structure, a location where the emperor sat and accepted the pilgrimage of the ministers waiting in the courtyard in front of him. Similarly, Mahāvīra Hall has two sets of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas statues arranged in the altar, separated by a wall reaching to the wooden beams of the roof. When there is a grand ceremony, pilgrims generally light incense and worship Buddha in the courtyard. Another example, Royal Hall (Aula Regia) (Figure 14) in Europe, shares great similarities with the Hall of Supreme Harmony: the King sat in the semicircular apse covered by a dome while the rest stood in front of him. Inside the Church, the altar is set in the east end, symbolizing the direction from whence God may come. Previously, pilgrims would stand in the vestibule in the west outside of the Church, however today they can sit in the central nave next to the entrance.

Figure 13.

Hall of Supreme Harmony, 万国来朝图, from the collection of The Palace Museum.

Figure 14.

Aula Regia, Reconstruction Sketch of Flavian Palace, Source J C Golvin.

The key similarity between the two buildings is that deitiesoccupy the highest and most important positions to ensure that they have the best view of the entire situation, thus allowing full control of any situation.

3.1.3. Similar Priority of Construction

Both the Three Temples as well as the Church get priority over other monastic buildings when it comes to construction, renovation, and restoration. The process of construction with regards to the internal layout of the buildings is also similar, with the process in both starting from the altar and extending out towards the entrance. When considering the entire monastery, the order of construction is also based on the division of functions amongst different zones; this is particularly important when economic potential may be restricted in the initial stages of establishing the monastery.

With a history of continuous expansion, destruction, restoration, and development of Guoqing Si (Guanding n.d.), it is clear that seven key construction works played large roles in the expansion and eventual spatial arrangement of the monastery (Figure 15). Initially, in the year 598 of the Sui Dynasty, the Main Hall was constructed at the center of the monastery. However, it was constructed during the humid season and building materials such as bamboo and wood were not used correctly (Guanding n.d.), meaning that in 605, four years after it was established, the buildings began to tilt and suffer from water leakage. It therefore required restoration works. The monastery later suffered during the great Anti-Buddhist Persecution (840–846), and during the late Tang Dynasty in the year 851, Emperor Xuanzong of Tang (685–762) ordered that Guoqing Si should be reconstructed. The Main Hall was to be rebuilt first, then the monks’ dormitories(佛殿初营,僧房未置。) (Shen 861). In 1005, Emperor Zhenzong of the Song Dynasty (1010–1063) bestowed a ton of gold to further restore and refurbish the monastery, and the Buddha statues were gilt (次参大佛殿,丈六金色释迦像,左右坐丈六弥陀、弥勒像,烧香礼拜。) (Shi n.d.). It was further renovated after Master Tan E (1285–1373) was reinstated by Emperor Taizu of Ming (1328–1398) to be the Abad of Guoqing Si in 1369 (Ding 1995). In 1733 in the early-mid Qing Dynasty, Emperor Shizong of Qing (1678–1735) issued an Imperial edict to reconstruct it once again, which reshaped the image of the monastery, and resulted in the basic layout of the current Guoqing Si (Ding 1995).

Figure 15.

Historical evolution of Guoqing Si.

In 1973, China and Japan resumed diplomatic relations. Japanese Prime Minister Tanaka Kakuei proposed to visit Guoqing Si, meaning the monastery once again had further restoration works under the support of Premier Zhou Enlai. Buddha statues in the Three Temples had their gold surface refurbished and some of them were even replaced by statues coming from Pekin.

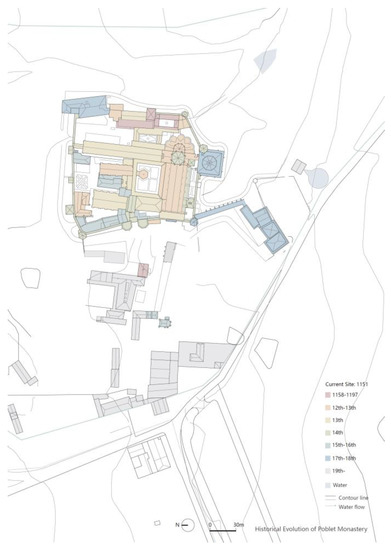

A similar history can be seen at the Poblet Monastery (Figure 16). The Church was largely built in two phases (Bassegoda Nonell 1983): the initial phase between 1151 and 1165 driven by the Count of Barcelona, Ramón Berenguer IV (1114–1162), and then again from 1165 through to the 12th century with the support of the King of Aragón and the Count of Barcelona, Alfonso II. This was analyzed in detail by José Luis Bozal González according to the marks left by stonecutters on the surface of the Church (Bozal González 2016). The Church can be divided into 4 parts: head, body, façade, and tower. The tower, situated on the top of the crossing of the central nave, was originally used as a bell tower. It was constructed in 1330 and was used in this way until the south tower of the Church was constructed in 1660, taking over as a bell tower. The form of the central nave was based on that of its motherhouse, the Church of Fontfroide Abbey, but it also took inspiration from the Abbey of Cluny, the grandest, most prestigious, and most well-endowed monastic institution in Europe, which had great influence on Europe from the second half of the 10th century through the early 12th. Alongside this, the Church of Poblet was also influenced by the Abbey of Saint-Denis, the prototype of gothic architecture.

Figure 16.

Historical evolution of Poblet Monastery.

It was completed in 1144 under the direction of the Abbot Sugar, then the Abbot Copons decided to reform the south-side aisle, raising the height of the roof and adding seven chapels. After a fire in 1575 and an earthquake in 1792, four buttresses were added to the south of the Church to support the wall of the central nave. However, the imbalance (Portal Liaño and González Moreno-Navarro 2013) of the structure caused by this reconstruction lead to cracks on the inner surface of the building, which has required a large amount of restoration in the past decade. All in all, the Church was the first aspect built in the Cloister (Bango Torviso et al. 1998). It also took the longest construction time, and has undergone many transformations and restorations since its initial development.

3.2. Programmed Functional Layouts

3.2.1. Similar Space Dominators

Both the Three Temples (Figure 17) and the Church (Figure 18) are essentially houses of deities, being devoted exclusively to worship and sacred rituals for monks, and serving as silent and sacred spaces for pilgrims. They are both dominated by visible and invisible powers, including supernatural, monastic, and social powers. Differences in their respective hierarchies are marked through the boundaries between their partitioned spaces.

Figure 17.

Plan of the Three Temples of Guoqing Si.

Figure 18.

Plan of the Church of Poblet Monastery.

Deities, who have supernatural power as beings of omniscience (all-knowing), omnipotence (all-powerful), and omnipresence (all-present), occupy the most important space in the Three Temples as well as in the Church. In the Three Temples, supernatural power refers to Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, Disciples, and Guardians of Buddhism. Their representatives are set in the corresponding place within the Three Temples according to their place within the hierarchy. Buddhas have to be adored at the end of the sacred axis, accompanied by Bodhisattvas. They are usually set at the center of kernel space in the enclosure, like Mahāvīra Hall. Eighteen Arhats stand on both sides of Buddhas while Guardians like Heng and Ha, and Four Heavenly Kings occupy the outer edge of the sacred space like Maitreya Hall and Heavenly King Hall. All of these symbolic statues in turn constitute a vivid and complete Buddhist world.

In the Church, the eastern end is the most sacred space and is where the cross of Jesus hangs above the altar. This in turn makes the cross the focus of all attention. It points to the east, the direction of Jesus’ arrival. The cross is illuminated by the rising sun when monks conduct office in the morning. Seven apses dedicated to saints are added at the head of the Church, which are behind the altarpiece. Seven chapels with holy saints are set in the south side of the Church, again illuminated by windows. In the Narthex, Mary and the Holy Sepulchre are arranged on each of the two sides. The assumption of Mary is located on the Baroque façade of the Church, symbolizing the welcoming of pilgrims to the world of God.

In both the Three Temples and the Church, monks occupy the place closest to the deities. As one of the three powers mentioned above, Monastic power can be roughly understood as comprising the roles of the abbot, monks, and pilgrims. A clear hierarchy exists among these three. Both cenobitic monasteries emphasize the absolute obedience of monks to the Abbots, which is also reflected in the arrangement of the space. The abbots generally occupy the second-best position by being placed below the representation of their respective deities. In Guoqing Si, during morning and evening chanting, the abbot performs the ritual of kneeling on the futon in the center of the Mahāvīra Hall, just in front of the altar, while in the Church the abbot sits behind the altar. Monks in turn stay on both sides of the Abbots, in a position which in Guoqing Si called Liangxu (两序) and in the Church is called Choir.

Pilgrims generally occupy the outermost position closest to the entrance. In the Three Temples, pilgrims normally stand in the courtyard (Mingtang) while in the Church, they sit in the atrium. When speaking about the role of pilgrims, it is worth noting that both monasteries are constructed by monks with the help of donation from pilgrims. With this in mind, some pilgrims hope that monks can sing a daily Mass for their soul (Altisent 1974), since they are the earthly representatives of their respective deities. In the mind of a pilgrim, making an offering to the monks and listening to their teachings is equivalent to making an offering to the deities themselves.

3.2.2. Similar Itineraries

In both monasteries, the itinerary of the journey to the monastery is mainly composed of two routes: mountain, and monastic. In turn, the two routes play different roles. The mountain route acts as a transition between the society and the monastery, and the monastic route becomes a structure which elucidates the relationship between deities and pilgrims. The purpose of the mountain route, with its beautiful natural landscape, is to relax pilgrims and help rid them of distractions. Then, upon entering the monasteries, the monastic route is full of order to reflect the majesty of the deities and the sacredness of the monastery. Usually, symmetrical space can better highlight the importance of the central axis.

A Chinese poem from the Tang Dynasty describes the experience of walking towards the Buddhist monastery in the early morning: “Early in the morning, I walked into this ancient monastery, the rising sunshine in the mountains. The forested curved path leading to a deeper place, lush and colorful flowers bloom around the Buddhist monastery. The mountain is so bright that the birds are more joyous, the lake is clear and refreshing. At this moment, all things are silent, leaving only the bell chime sound.”3 Pilgrimage is thus achieved by approaching the monastery step by step.

At the foot of Tiantai Mountain, the first thing pilgrims catch sight of is the large paddy fields. Behind that, Sui Pagoda is the most obvious sign indicating the final destination of Guoqing Si (Figure 19). Pilgrims encounter the Seven Buddhas Pagodas and Hanshi Pavilion on the winding mountain route which leads them towards the monastery. They reach Fenggan Bridge in front of the Mountain Gate and once they pass through the Mountain Gate, a journey of direct Buddha worship begins (Figure 20).

Figure 19.

Worship itinerary of Guoqing Si.

Figure 20.

Topographic plan of Guoqing Si.

At Poblet Monastery (Figure 21), pilgrimage is a process that takes place from dusk to dawn. Pilgrims from nearby villages walk along the monastic wall and go through the Prades Gate, the Golden Gate, then finally reach the square in front of the Church. In the early morning, dawn vaguely illuminates the outline of the Church, itself located in the wilderness. The main gate of the Church is opened, leading the pilgrims to the altar where the east end of the Church is lit by the sunshine through the window of the thick wall. (Figure 22).

Figure 21.

Worship itinerary of Poblet Monastery.

Figure 22.

Topographic plan of Poblet Monastery.

The itinerary set for monks and pilgrims to approach the altars helps to further develop respect and admiration towards their respective deities. It is no exaggeration to say that the longer the route, and the more filled with special and reverent experiences, the more this feeling can be enhanced. Further to this, the spatial layout of the route and monasteries themselves also has a great influence on the feelings of visiting pilgrims.

The terrain of the Three Temples, Maitreya Hall, Heavenly King Hall, and Mahāvīra Hall gradually rises. Such a layout not only corresponds to the mountainous surroundings but also highlights the importance of the Mahāvīra Hall, where the altar is located (Figure 23). In the Church, the position of the altar is higher than that of the Choir, and the position of the Choir is higher still than that of the pilgrims. The height difference, despite only being a single step, allows for the setting up of a separation between the sacred and the secular whilst still being convenient for people to reach (Figure 24).

Figure 23.

Axonometric section of the Three Temples.

Figure 24.

Axonometric section of the Church.

In both cases, deities are arranged at the end of the space, accessed by a one-way route. Spatial layout thus defines the order of importance among deities, monks, and pilgrims and delineates a specific journey to be taken. In their architectural details, both the Three Temples and the Church create a sacred itinerary for pilgrims and monks through height difference, enclosure, and image.

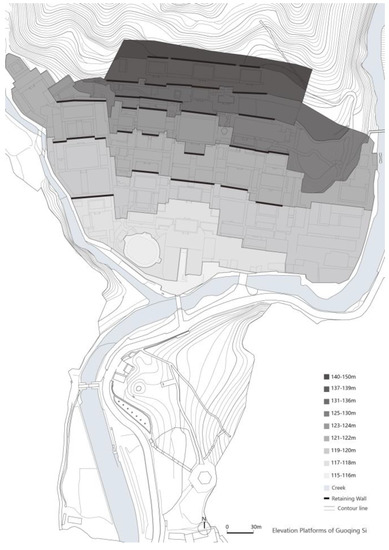

In Buddhist monasteries, the changes in the height of platforms reveal the hierarchy of importance and define the boundary between the sacred and the secular. The buildings of Guoqing Si are situated on eight different platforms of terrain (Figure 25). Take the central axis as an example: there are five temples and a main gate situated across the eight platforms of the terrain. Among them, the Mahāvīra Hall, with the largest dimensions, occupies two platforms. The height difference between the two platforms is around three metres, or approximately the same height as a single floor. Buildings on two sides of the central axis sit on one to two floors, according to their location on different terrain platforms. The Mahāvīra Hall is placed in the center, under its eaves sitting the eaves of each side building. This, therefore, highlights the importance of the Mahāvīra Hall, whilst steps between terrain platforms are further conducive to leading pilgrims on the continuous process of worshiping the Buddhas.

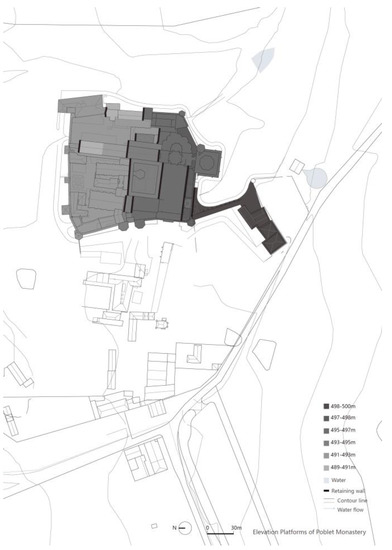

Figure 25.

Elevation platforms of Guoqing Si.

In Cistercian monasteries, even though buildings are normally constructed in a flat valley, the Church is similarly set in a higher place compared to the rest of the buildings. The Main Cloister is mainly situated on six terrain platforms (Figure 26). The height difference between each two terrain platforms is around one to two metres. Although the Abbot’s Palace is situated on the highest terrain, it is located outside the Main Cloister. Therefore, the Church and the New Sacristy occupy higher terrain than the Cloister, the Refectory, and the Novice House, showing their respective importance.

Figure 26.

Elevation platforms of Poblet Monastery.

Further to this, on the highest elevated platforms inside both the building of the Three Temples and the Church, one can find holy altars. Their high location both reveals and stresses their sacredness. Indeed, every sacred space defines a sacred object, which in turn marks the environment. The enclosed hall limits the space for monks to worship the Buddha while the niche is a symbolic residence of the Buddha. Pilgrims generally take the route of worship in the central axis, and the corridors on both sides of the Three Temples allow monks to bypass the Heavenly King Hall and avoid overlapping with the route of pilgrims on their journey to worship Buddha—they can enter directly from the side doors of the Mahāvīra Hall. In the Church, the Choir is located next to the altar and is mostly enclosed by huge stone pillars and wooden seats. This means that the monks’ daily office will not be interrupted by the pilgrims walking down the two side aisles.

Images are also important in affecting the perception of pilgrims on their itinerary of worship. In the Three Temples, the Maitreya Buddha with a big belly and smiling face sits inside the niche of the Maitreya Hall, which welcomes the coming pilgrims. The image of the Maitreya Buddha reduces pilgrims’ alertness. The solemn expressions of the four heavenly kings in the Heavenly King Hall reshape the majesty and order of the world of Buddhas. When pilgrims enter the Mahāvīra Hall and bow to the Buddha Shakyamuni, they complete their confession through a complete ritual. Similarly, in the Church, the statue of Mary with open hands on the west facade of the Church symbolizes the entrance to the sanctuary where pilgrims are welcome to go inside and receive a blessing from God. At the east end of the Church, above the altar, Christ is nailed to the cross, representing the transmission of life and death and showing the separation between the material world and the heavens. At this, the mood of the pilgrims changes from the initial sense of ease gained from both the mountain route and the entering into the monastery, towards a more serious and reflective nature upon facing the icon of Jesus.

4. Discussion of the Differences behind the Similarities

4.1. Integration and Independence

The way that worship spaces connect to the rest of the monastic layouts are mainly reflected in the following three aspects: open and closed, void and solid, disappearing and emphasizing.

The Three Temples have an image of openness, while the Church appears more closed. The core courtyard is in front of the main hall, which is considered the climax of the central axis sequence (Zhao 2013). It not only constitutes a key aspect of the worship itinerary, but also connects the eastern and western parts of Guoqing Si (Ding 1995).

In contrast, the Church maintains closed in the north and south façades, which are regarded as independently functioning volumes (Domènech i Montaner 1925). The core courtyard in Guoqing Si, as a void space, radiates a certain emptiness to the surrounding space, in contrast to the way in which the Church declares dominance over the entire complex through acting as a solid space.

The courtyard is an introverted external space (Hou 2011), arranged in the traditional layout of Buddhist monasteries (Liang 1961). Indeed, courtyards of different sizes have become the units of the monastery’s “organizational procedures” (Li 1982). To some extent, the courtyard is thus highly integrated into the spatial grammar of monastic layout (Ge 1979). The Church has been independent from other aspects of the complex from the beginning (Altisent 1974), and over time the building volume has been added and continuously strengthened (Finestres y de Monsalvo and Guitert i Fontseré 1947).

In the end, the boundaries of the Three Temples are blurred and melted into the overall spatial layout while the Church is constantly being strengthened, individualized, and emphasized in the monastery complex.

4.2. Different Understanding of Deities

4.2.1. Different Ways of Worship

Even though both cases share a similar functional layout and priority of construction, in considering both monastic traditions, different ways of worship are depicted. In the Three Temples, the courtyard serves as an exterior temple where ceremonies such as incense burning and rituals are held. This means that both exterior and interior spaces function as sacred spaces for monks and pilgrims to worship Buddhas. In contrast, the Church mostly holds ceremonies indoors.

In Guoqing Si, the spacious courtyard not only serves as a location for drying rice for the traditionally agricultural society, but it is also fundamental as a space where monks can perform all of their rituals. Take the three altars of ordination (novice monk, bhikkhu, and bodhisattva) as examples. These processes are usually held at the same time. Monks need to perform confession for at least three days and three nights. During this period, the ordained master must perform related rituals in both the main hall and courtyard, moving back and forth between the spaces as required by the role. It is important to note that both half and full prostrations are used by Buddhist monks. A half prostration involves kneeling and touching the earth with one’s hands and forehead. In full prostration, monks have to slide forward until completely lying down, pivoted the forearms on the elbows, and raise the hands with palms up, an action which symbolizes raising the Buddha’s feet above one’s head. The full prostration shows reverence to the Triple Gem (Buddha, Dharma, and monks). In full prostration, two meters’ distance must be maintained between each monk. Thus, half prostrations are generally held inside the temple, while full prostrations are held in the courtyard. Inside the Mahāvīra Hall, half prostration and circumambulation around the altar are usually undertaken by monks during morning and evening chanting. Consistent with the changing rituals, and apart from the fixed position of the Buddha statue, the futons used by monks can be moved according to the needs of different ceremonies.

In contrast, Cistercian monks and pilgrims normally perform rituals solely inside the Church. The exquisite furniture of the Choir is therefore fixed in place front of the altar. The design of the seat is such that it supports the way the monks pray. There is space for them to turn around and bow to the altar. It also satisfies them to sit while looking at each other, whilst at the same time, they can lean on the chairs when they stand up. Such postures are usually performed in daily offices, whilst during misars or certain festivals, the priest also circumambulates the altar. Bread and wine as symbols of the body and blood of Christ are delivered by monks to serve the pilgrims. Generally speaking, pilgrims will sit in the atrium, listen to the prayers of the monks, and stand up at appropriate times or kneel on wooden benches to pray.

In both worship spaces, specific religious behavior affects the definition of how space should be used. In turn, concrete forms of space and furniture regulate and standardize the sacred rituals. Such different ways of worship are the embodiment of the relationship among different space dominators and affect the formation of worship routes, which have to do with different understandings of deities in both monasticisms.

4.2.2. World of Buddhas vs. Immeasurable God

Even though the Three Temples and the Church share a lot of similarities in functions and composition of structure with regards to space dominators, their ways of visualizing the existence of deities are quite different. In expressing sacredness, Buddhist monasteries pay more attention to the depiction of Buddha statues. In contrast, the medieval Cistercian Church was a space devoted to visualization and imagination (Cassidy-Welch 2001).

The depictions of Buddha statues have become important features to demostrate the importance of the deity within different spaces. They are made as symbols to form a world of Buddhas, the size of which normally corresponds with the scale of the architecture. Buddhist monasteries build bodies for Buddhas, and they even have a reference book, Fo Shuo Zao Xiang Liang Du Jing (佛说造像量度经) (Gongbuchabu 1874) which defines a suitable size ratio of Buddha statues. Therefore, the space evolves with the scale of the Buddha statues within the monastery. It is worth noting that monks are not allowed to be idolaters. Buddhist monasteries build a world of Buddhas through murals and statues with the goal of breaking the image of Buddhas, which also helps us understand that there are countless incarnations of Buddha; no single image can be worshipped. The worship posture is to remind monks and pilgrims to keep humble at all times. Furthermore, excluding the main Buddha statues which are usually very tall, most Buddha statues are either slightly bigger or similar to human scale, like Luohan statues sitting on the platform in the Mahāvīra Hall. Pilgrims feel less or even no distance from Buddha, since at this scale they seem approachable (Figure 27).

Figure 27.

World of Buddhas of Guoqing Si.

For a medieval monk or nun, building an abbey was as much an act of spirituality as the meditation and contemplation carried out within it (Kinder 2000). In the Cistercian church, God Himself is immeasurable. Instead, it is the actual architecture that is considered as the symbol of God (Figure 28). For monks in the Middle Ages, architecture was one of the best tools to express their aesthetic idea, religious practice, and expectations for life. Statues are seen as idols and are not encouraged in the Church, in accordance with God’s commandment: “You shall not make for yourself a graven image or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth: you shall not bow down to them or serve them” (Exodus n.d.). With this limitation, therefore, how is the scale of God presented in the Church?

Figure 28.

Immeasurable God of Poblet Monastery.

The sacredness of space is represented through the use of light, which symbolizes how God has brought light to the world. Usually, windows in the Church are very small, sealed with a light-transmitting thin marble plate to prevent thieves from entering. On one hand, this is a limitation of the technology and methods in stone construction, but on the other hand, it is also a safety consideration. The interior space of the Church is portrayed as a container of light. The office of Martines takes part in the early morning when the sun rises in the east, while the office of Vispera is performed before sunset as the last sunshine of a day goes through the roseton on the west facade of the Church towards the Choir. Further to all of this, within the Church, the cross of Jesus is abstracted, simplified, and hung in the air to show its importance, uniqueness, and inaccessibility.

The relationships between deities and man are portrayed through space, and finally presented as different itinerary perceptions with different distances to deities.

4.2.3. Different Distances to Deities

Even though they share similar logic in shaping the atmosphere of the worship itinerary, in the two monasteries it is clear that the distance between deities and pilgrims is also different.

In the Buddhist worldview, the term Buddha meaning “enlightened person” means the state of being a Buddha can be reached through practice. The central axis with stairs to climb upward is the symbol of the step-by-step journey towards becoming Buddha. On the contrary, the statue of Jesus is small and is hung in the air, much higher than the flat ground upon which the pilgrims remain. This means the pilgrims’ distance to God is insurmountable, confirming the unique and unattainable nature of God and godhood.

In both monasteries, spatial forms perform as effective strategies to assure the legitimacy of sacredness. Pilgrims believe that their proximity to the deities will imbue the individual with power. The closer one can approach the deities, they believe, the stronger and more auspicious the connection between them (Kilde 2014).

In Buddhist monasteries, sacredness is achieved by taking advantage of the height of the natural environment. For example, the central axis of the Three Temples is constructed on the mountain. “One day I shall climb to the summit, seeing how small surrounding mountain tops appear as they lie below me.” (会当凌绝顶,一览众山小) (Du n.d.) The Cistercians create a contrast between the height of space and the human body, thereby making human surrender and admire. It imagines that the height of the building can be used to narrow the distance between humans and the heavens.

5. Conclusions

This research has considered the specific spatial relationship of deities, monks, and pilgrims, and found the external and internal common ground between two traditional worship spaces. Further on, it triggers more open discussions about the reasons behind the differences and similarities between the two, and considers an historical evolution. Further research also hopes to provide a dialogue bridge and a method for cross-cultural communication in considering the spatial and spiritual aspects.

“The conclusions drawn from an in-depth study of such a small social unit are not necessarily applicable to other units. However, such a conclusion can be used as a hypothesis or comparative material when conducting surveys elsewhere. This is the best way to get true scientific conclusions.” (Fei 2001) Inspired by the Peasant Life in China (江村经济), the possibility of popularization can be obtained through in-depth research on individual cases. Both places of worship represent human imaginings of deities. The relationships among pilgrims, monks, and deities are established through the functional layout, space dominators, and itinerary of worship. The research on their grammar structure aims to bring guiding principles for contemporary spiritual space; namely, how to define the scale of deities through the depiction of distance and finally affect pilgrims’ methods of adoration.

Externally, the Three Temples and the Church enjoy top priority in terms of construction, occupy key positions in the overall monasteries, and become the main reference for the development of monastic layouts. Internally, they share similar programmed functional layouts; defining the boundary between the sacred and the secular, highlighting the importance of deities within a space, and guiding pilgrims to complete their rituals of worship.

Based on the lives of similar monks, the article has found the external and internal similarities of both worship spaces. However, due to different understandings of deities themselves, both worship spaces and indeed both monastic traditions show different ways of worship, images of deities, and approaches to the distance between them and humanity. To further explore the reasons behind the similarities and differences that the comparative study has found, an open discussion may be considered: how can we reflect the different understandings of deities in both Buddhist and Cistercian monasteries? How have the worship spaces transformed through different periods, and what are their corresponding similarities and differences? In the development process, do they influence each other? These may require the emergence of more historical materials and archaeological results. The importance of research lies in understanding the relationship between deities and pilgrims from the view of the East and the West, and their specific materialization and expression in the architectural space.

The comparative study of the similarities and differences is the cross-cultural contact between the eastern and western spiritual spaces. Such interaction between Buddhism and Christianity helps to recognize the characteristics and differences of their respective cultures, and at the same time provides a bridge for communication and connections by way of their similarities.

Funding

This research was funded by CHINA SCHOLARSHIP COUNCIL, grant number 201406260218.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

This paper is conducted under the financial support from the China Scholarship Council, 2014–2018, File No.201406260218. It derives from the dissertation under the direction of José Ignacio Linazasoro and Fangji Wang. I am very grateful to them for their detailed guidance on the structure of the article. Besides, thanks to Aibin Yan and Shuishan Yu who have provided constructive comments on the article. During the process of investigation, Abbot Yunguan, Master Yanru of Guoqing Si and ex-Prior Lluc Torcal, Prior Rafael of Poblet Monastery, and Jordi Portal have generously provided great help and related research materials for the research. Considering the English Editing, Amelia-Rose Rubin has generously offered great help to me, which is appreciated.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | According to the Rule of Saint Benedict, there are four kinds of monks: Cenobites, Anchorites (or Hermits), Sarabaites and Landlopers. |

| 2 | Although Guoqing Si belongs to Tiantai sect, it was converted to Chan Buddhist in Song Dynasty, and later changed back to Tiantai sect. |

| 3 | 常建【唐】题破山寺后禅院“清晨入古寺,初日照高林。曲径通幽处,禅房花木深。山光悦鸟性,潭影空人心。万籁此俱寂,但余钟磬音。”. |

References

- Altisent, Agustín. 1974. Història de Poblet. Tarragona: Tarragona Abadía de Poblet. [Google Scholar]

- Bango Torviso, Isidro G., María Lucía Barrero, Julio David Pizarro, María del Carmen Muñoz Párraga, Concepción Abad Castro, María Teresa López de Guereñoo Sanz, Susana Calvo Capilla, Eduardo Carrero Santamaría, Elena Casas Castells, and Antonio García Flores. 1998. Monjes y Monasterios. El Cister en el Medievo de Castilla y León. Valladolid: Junta de Castilla y León. [Google Scholar]

- Bassegoda Nonell, Juan. 1983. Història de la restauració de Poblet: Destrucció i reconstrucció de Poblet, 1st ed. Tarragona: Tarragona Abadia de Poblet. [Google Scholar]

- Benedict of Nursia. 516. The Rule of Saint Benedict. Tarragona. [Google Scholar]

- Boerschmann, Ernst. 1912. Chinese Architecture and Its Relation to Chinese Culture. 1911 Annual report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. [Google Scholar]

- Boisvert, Mathieu. 1992. A Comparison of the Early Forms of Buddhist and Christian Monastic Traditions. Buddhist-Christian Studies 12: 123–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozal González, José Luis. 2016. Iglesia del Monasterio de Santa Maria de Poblet, Una hipótesis sobre las fases de su construcción basada en sus signos de cantero. Available online: http://www.signosdecantero.com/descargas/Santa_Mar%EDa_Poblet_JL_Bozal.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2021).

- Braunfels, Wolfgang. 1972. Monasteries of Western Europe, the Architecture of the Orders. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy-Welch, Megan. 2001. Monastic Spaces and Their Meanings: Thirteenth-Century English Cistercian Monasteries. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Dehui. 1335. Chi Xiu Baizhang Qing Gui. Available online: http://buddhism.lib.ntu.edu.tw/BDLM/sutra/chi_pdf/sutra19/T48n2025.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2021).

- Ding, Tiankui. 1995. Guo Qing Si Zhi, 1st ed. Shanghai: Hua Dong Shi Fan Da Xue Chu Ban She. [Google Scholar]

- Domènech i Montaner, Lluís. 1925. Historia y arquitectura del Monestir de Poblet. Barcelona: Montaner y Simón. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Fu. n.d. Available online: https://www.shicimingju.com/418.html (accessed on 4 November 2021).

- Exodus. n.d. Available online: https://biblia.com/bible/esv/exodus/20/4-5 (accessed on 4 November 2021).

- Fei, X. 2001. Jiangcun Jing Ji: Zhongguo Nong Min De Sheng Huo (江村经济: 中国农民的生活), 1st ed. Shang Wu Yin Shu Guan Wen Ku. Beijing: Shang Wu Yin Shu Guan. [Google Scholar]

- Finestres y de Monsalvo, Jaime, and Joaquin Guitert i Fontseré. 1947. Historia del Real Monasterio de Poblet, illustrada con disertaciones curiosas sobre la antiguedad de su fundación. Barcelona: Editorial Orbis. [Google Scholar]

- Frampton, Kenneth. 2015. A Genealogy of Modern Architecture: Comparative Critical Analysis of Built Form. Edited by Ashley Simone. Zürich: Lars Müller. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Ruliang. 1979. Guoqing Temple in Mount Tiantai. Journal of Tongji University 4: 10–22. [Google Scholar]

- Gongbuchabu. 1874. 佛说造像量度经 (Fo Shuo Zao Xiang Liang Du Jing). Available online: http://buddhism.lib.ntu.edu.tw/BDLM/sutra/chi_pdf/sutra10/T21n1419.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2021).

- Guanding. n.d. Guoqing Bailu. Available online: http://buddhism.lib.ntu.edu.tw/BDLM/sutra/chi_pdf/sutra19/T46n1934.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2021).

- Henry, Patrick Gillespie, and Donald K. Swearer. 1989. For the Sake of the World: The Spirit of Buddhist and Christian Monasticism. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, Collegeville: Liturgical Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, Puay-peng. 1995. The ideal monastery: Daoxuan’s description of the Central Indian Jetavana vihara. East Asian History (Canberra) 10: 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Horn, Walter, Ernest Born, and Saint Adalard. 1979. The Plan of St. Gall. California Studies in the History of Art. Berkeley: University of California Press, vol. 19. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Youbin. 2011. 中国建筑之道 (Zhongguo Jianzhu Zhi Dao). Beijing: China Architecture & Building Press. [Google Scholar]

- Itō, Chūta. 1931. Shina kenchikushi. Tōyōshi kōza. Tōkyō: Yūzankaku, vol. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Kilde, Jeanne Halgren. 2014. Sacred Power, Sacred Space: An Introduction to Christian Architecture and Worship. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kinder, Terryl Nancy. 2000. Architecture of Silence: Cistercian Abbeys of France. New York: H.N. Abrams. [Google Scholar]

- King, Peter. 1999. Western Monasticism: A History of the Monastic Movement in the Latin Church. Cistercian studies series, no. 185. Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Yunhe. 1982. Hua Xia Yi Jiang: Zhongguo Gu Dian Jian Zhu She Ji Yuan Li Fen Xi. Hong Kong: Guang Jiao Jing Chu Ban She; Hua Feng Shu Ju Fa Xing. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Sicheng. 1932. 蓟县独乐寺观音阁山门考 (Research on the Gate and Pavilion of Dule Temple in Ji County). 中国营造学社汇刊 (Journal of the Society for Research in Chinese Architecture) 3: 1–92. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Sicheng. 1961. 中国的佛教建筑 (Buddhist architecture in China). 清华大学学报 (Journal of Tsinghua University) 12: 53–54. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Sicheng, and Wilma Fairbank. 1984. A Pictorial History of Chinese Architecture. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Dunzhen. 2007. Liu Dunzhen Quan Ji, 1st ed. Beijing: Zhongguo Jian Zhu Gong Ye Chu Ban She. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, Simon Young-suck. 1998. Korean and American Monastic Practices: A Comparative Case Study. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press. [Google Scholar]

- Portal Liaño, Jorge, and José Luis González Moreno-Navarro. 2013. La iglesia del Real Monasterio de Santa María de Poblet: pasado y presente de un desequilibrio. Edited by Santiago, Huertay Fabián and López Ulloa. Madrid: Instituto Juan de Herrera. [Google Scholar]

- Prip-Møller, Johannes. 1937. Chinese Buddhist Monasteries, Their Plan and Its Function as a Setting for Buddhist Monastic Life. Copenhagen: G.E.C. Gad, London: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sekino, Tadashi, and Daijō Tokiwa. 1926. Shina Bukkyō shiseki. Tōkyō: Bukkyō Shiseki Kenkyūkai. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Huan. 861. 国清寺止观堂记 (The Note of Zhiguan Tang in Guoqing Monastery).

- Shi, Chengxun. n.d. 参天台五台山记 (Can Tiantai Wutai Shan Ji). Available online: http://tripitaka.cbeta.org/B32n0174_001 (accessed on 4 November 2021).

- Su, Bai. 2009. Zhongguo Gu Jian Zhu Kao Gu, 1st ed. Su Bai Wei Kan Jiang Gao Xi Lie. Beijing: Wen Wu Chu Ban She. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Dazhang. 2017. Zhongguo Fo Jiao Jian Zhu, 1st ed. Beijing: Zhongguo Jian Zhu Gong Ye Chu Ban She. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, Francis Edward. 1932. Church Architecture: Building for A Living Faith. Milwaukee: The Bruce Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Guixiang. 2011. 中国古建筑测绘十年 (Ten Years of Surveying and Mapping Ancient Chinese Architecture). Beijing: Tsinghua University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Guixiang. 2016. 中国汉传佛教建筑史: 佛寺的建造、分布与寺院格局、建筑类型及其变迁 (Zhongguo Han Chuan Fo Jiao Jian Zhu Shi: Fo Si De Jian Zao, Fen Bu Yu Si Yuan Ge Ju, Jian Zhu Lei Xing Ji Qi Bian Qian (The History of Chinese Buddhist Architecture)), 1st ed. Beijing: Tsinghua University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Weiqao. 2021. Tiempo y espacio: Investigación sobre el espacio monástico a través de la vida en los monasterios budistas y cistercienses = Time and space: Research on Monastic Space through Monks’ Life in Buddhist and Cistercian Monasteries. Thesis (Doctoral), E.T.S. Arquitectura (UPM). Available online: https://doi.org/10.20868/UPM.thesis.68991 (accessed on 4 November 2021).

- Wang, Weiren, and Zhu Xu. 2011. 中国早期寺院配置的形态演变初探:塔·金堂·法堂·阁的建筑形制 (Topological Study on the evolution of early Chinese Buddhist Monasteries: Layout of Pagoda, Buddha Hall, Lecture Hall and Pavilion Tower). 南方建筑(South Architecture) 1: 38–49. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Yuan, and Bingjie Lu. 2000. 中国古代佛教建筑的场所特征 (Characteristic of Chinese temple architecture place). 华中建筑(Hua Zhong Jian Zhu) 18: 131–33. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Lianyuan. 1717. Tiantai Shan Quan Zhi: 18 Juan. Available online: https://hollis.harvard.edu/primo-ex-plore/fulldisplay?docid=01HVD_ALMA212047190400003941&context=L&vid=HVD2&lang=en_US&search_scope=everything&adaptor=Local%20Search%20Engine&tab=everything&query=any,contains,%E5%A4%A9%E5%8F%B0%E5%B1%B1%E5%85%A8%E5%BF%97&offset=0 (accessed on 4 November 2021).

- Zhang, Yuhuan. 2012. Tu Jie Zhongguo Fo Jiao Jian Zhu, 1st ed. Beijing: Dang Dai Zhongguo Chu Ban She. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Nadong. 2013. 敦煌莫高窟初唐石窟所反映的佛寺核心院落主题 (The theme of the core courtyard of the Buddhist temple reflected in the early Tang Grottoes at Mogao Grottoes at Dunhuang). 中国建筑史论汇刊 (Journal of Chinese Architecture History) 1: 212–23. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).