1. Introduction

“Here even a child will begin a story about his grandmother with the words: ‘in those days the river wasn’t here and the village was not where it is…’” The “here” in this evocative description by Amitav

Ghosh (

2016, p. 6) refers to the Bengal river delta, where the various branches of the Ganges, Padma, Brahmaputra and Meghna interweave and interlace as they find their way to the Bay of Bengal. As these different streams and currents find their course, they claim, shift, erode and reassemble land. Or, in the words of

Ghosh (

2016, pp. 5–6): “Overnight a stretch of riverbank will disappear, sometimes taking houses and people with it; but elsewhere a shallow mud bank will arise and within weeks the shore will have broadened by several feet”. This “eventfulness of the river” (

Khan 2019) is a recurring trope in descriptions of the Bengal delta.

Saikia (

2019, p. 511) for instance describes the Brahmaputra as a “living force”. He elaborates that “like many other rivers, it is alive, angry, intense, or fickle, sometimes volatile and at other times, peaceful” (

Saikia 2019, p. xxxii). Such descriptions not only highlight the energetic and erratic agency of the river as a more-than-human entity, but they also speak to pervasive forms of uncertainty and unknowability. This is nowhere as clear as in the case of the so-called

char lands, sandbanks in the river that disappear and re-emerge as the river changes course. The communities that inhabit these temporary islands continuously live through repetitious cycles of losing and regaining land, while the

chars themselves straddle the “ill-defined boundary between land, water, and the air” (

Lahiri-Dutt and Samanta 2013, p. 14).

In recent years, a growing awareness of anthropogenic climate change has led to a renewed scholarly interest in wet, fluid and amphibious spaces such as

chars. Indeed, both water and islands have been singled out as useful concepts to “think with” in the context of the Anthropocene (

Crate 2011;

Chandler and Pugh 2021a;

Hastrup and Hastrup 2016;

Helmreich 2011;

Jensen 2017;

Krause 2017;

Steinberg and Peters 2015;

Stensrud 2016). The climate crisis is very much tied to certain water-related disasters, including flooding, rising sea levels, melting ice, erosion, drought and excessive rainfall. Consequently, “water is often the medium through which the message of climate change is delivered” (

Jensen 2017, p. 225). Similarly, islands—especially sinking or disappearing islands—have also proven “particularly well suited to condensing global anxieties in the face of unprecedented environmental degradation” (

Harms 2015, p. 62). Far from merely conveying or illustrating the message of climate change, water and islands also frequently function as “theory machines” (

Helmreich 2011). Indeed, a growing idiom of wetness has been used to conjure the image of an open-ended, fluid, relational and variable world-in-formation where the fixities, boundaries, binaries and teleologies of coloniality and modernity have definitively lost their authority and explanatory power.

This paper brings the ethnographic literature on Bengali

chars1 in conversation with such amphibious strands of thinking, in order to make sense of the “radical uncertainty of climate change” (

Chakrabarty 2014, p. 14). However, instead of taking the wet and watery qualities of this landscape as a point of departure for theorizing uncertainty, I suggest that we need to pay better attention to the immaterial, opaque and spiritual powers that reside below and beyond the water. These more-than-human undercurrents, which are well-documented in the literature on

chars, provide my starting point for making sense of the relationship between uncertainty and adaptation in a riverine context of continuous variation. Whereas adaptation, especially in amphibious contexts, is often understood as the intuitive attunement to environmental rhythms (see also

Chandler and Pugh 2021b), I argue that such a perspective pays insufficient attention to the erratic and unknowable aspects that animate land/waterscapes. Instead, without wanting to dismiss the importance of local forms of environmental knowledge, I seek to foreground the many ways in which people struggle to know their surroundings (see also

Pearce 2020). This paper draws attention to such experiences of ambiguity and ambivalence by focusing on the spirit-geographies that “may run through continents, under the ocean, and within forests” (

Sheller 2021, p. 3).

The central question that guides this exploration is: “How do people’s experiences with the more-than-human forces that reside below and beyond the river shape forms of dwelling-in-uncertainty in the amphibious context of the Bengali char lands?” After offering a brief description of this amphibious context, I will subdivide the main question into three strands of inquiry. First, on a theoretical level, I ask what paying attention to such divine, immaterial and spiritual undercurrents might contribute to recent efforts to theorize the existential uncertainties of the Anthropocene through water. In doing so, I seek to move beyond reified solid–fluid distinctions and address explicit attention to the imponderable powers that “dematerialize the plane of existence” and often linger at the periphery of people’s perception and understanding of the world. Next, I move on to the specific context of chars, where I look at the ways in which divine and supernatural forces are understood to shape and warp cycles of losing and regaining land. While drawing from localized religious narratives, informed by both Hinduism and Islam, I ask how this underwater presence affords experiences of ambiguity and unknowability in the chars. Finally, in the last section, I look at how such forms of dwelling-in-uncertainty take shape on an embodied and material level. This section asks how people’s slippery entanglements with an increasingly imponderable river relate to the gendered ways in which char communities reproduce their homes and livelihoods over time and across ever-shifting landscapes.

My analysis is based on the ethnographic literature on the Bengal river delta and includes sources that focus on

chars in both India (

Harms 2014,

2015;

Lahiri-Dutt and Samanta 2013) and Bangladesh (

Hossain 2018;

Indra 2000;

Khan 2014a,

2014b,

2016;

Lein 2009;

Zaman 1988,

1999). It is beyond the scope of this paper to offer an exhaustive review of the literature on

chars. Instead, my reading of the aforementioned works has been informed by a specific focus on religion, gender and environmental change. While this paper relies primarily on secondary ethnographic sources, it was written in preparation and anticipation of future field research which has been postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. My interest in

char communities was first sparked during PhD research in Bangladesh which, although carried out almost exclusively in the capital city of Dhaka, also tangentially involved

char and riverbank communities. At the time, I conducted research with rural–urban migrants who worked as cycle-rickshaw drivers in Dhaka and often came from

char and riverbank communities that had been affected heavily by erosion

2. Throughout my research I came to realize that the mobility of my interlocutors could not be disconnected from that of the wider land/waterscape. This paper then, in many ways, reflects a first attempt to further come to terms—analytically—with the mobility and changeability of this riverine context.

It was a conscious decision not to limit the scope of this paper to

chars in Bangladesh, but to look at the Bengal delta more broadly. Indeed, for a paper that focuses on water, it seemed appropriate to use rivers rather than geo-political borders as a means for demarcation. Moreover, the deltaic ecology of Bengal

3, with its fluid, forested and low-lying marshlands, has often been linked to a specific set of cultural and religious practices. Of particular relevance to this paper is the region’s history of what has, for better or worse

4, been labeled as religious syncretism. Various historians have pointed out that the spread of Islam in the region coincided with a process of creative adaptation and translation that drew heavily on existing and overlapping forms of animism, Hinduism and Buddhism (

Eaton 1993;

Roy 1983;

Van Schendel 2009). As a consequence, Bengal knows many shrines, holy figures and festivals that are visited, worshipped and observed by Hindus and Muslims alike. At the same time, such localized religious practices have always existed in tension with (political) efforts to cement religious identities and allegiances, whether by colonial administrators, Muslim separatists or—more recently—Hindu nationalists (

Roy 2005, p. 2)

5. Although

char contexts have also, inevitably, been shaped by such wider tensions (see

Das 2021), the literature nonetheless suggests that people’s spiritual and embodied engagements with their amphibious surroundings continue to be shaped by a degree of “localized syncretism and hybridity” (

Harms 2014, p. 282).

2. Char lands: Between Land and Water

The myriad rivers of the Bengal delta have long constituted life-worlds that are neither territorially nor temporally fixed. Indeed,

Van Schendel (

2009, p. 7) portrays living in this environment as “living on a perennially moving frontier between land and water”. The history of habitation in this “land of silt and water”, then, is very much a history of people being forced “continually to put themselves dangerously in water’s way” (

Van Schendel 2009, p. 7). In his history of the Brahmaputra river,

Saikia (

2019, p. xxiii) similarly chronicles that “the people who made the floodplains their home tried to adjust the rhythm of their life to the tune of the river”. He goes on to elaborate that, for centuries, “farmers, fishers, graziers, traders, and soldiers learned the art of adaption to the ebb and flow of the river”, as they learned to recognize how land and water were inseparable (

Saikia 2019, p. xxiii). This act of balancing the perennially moving frontier between land and water is particularly important for

char dwellers, who have to “dance” with the “changeable moods of the river, trying to make the best of their vulnerable situation in a marginal environment” (

Lahiri-Dutt and Samanta 2013, p. 149). In many ways,

chars are thus representative of the fluidity of the land–water boundary that has long characterized the Bengal river delta as a whole.

This fluid and ever-shifting boundary between land and water complicates conventional framings of climate change, which often focus on events—such as flooding and erosion—that are to some extent normal in

char contexts. The scholarship on riverine realities in Bengal highlights how complicated it is to single out distinct moments of disaster amidst everyday realities of environmental change. For instance,

Shaw (

1992, p. 205) points out that experiences of flooding in Bangladesh often oscillate between flood-as-resource and flood-as-hazard, thereby blurring the “dichotomy between a predictable ‘normality’ and an unpredictable ‘hazard’”. Similarly,

Harms (

2015) has argued that the disappearance and erosion of land, far from signaling a unidirectional event, should be understood in relation to “circuits of displacement and emplacement”. This reality of movement, change and seasonal variability thus makes it difficult to disentangle the effects of climate change from familiar forms of ecological vulnerability and change (see

Khan 2014b, p. 296). Indeed, in this particular context, the impact of climate change seems to manifest itself in the continuation and intensification of existing conditions rather than in drastically new forms of vulnerability and risk. For

char dwellers, this means that they increasingly have to cope with extended periods of flooding, unpredictable patterns of erosion and the fragmentation of bigger islands into smaller ones (

Hossain 2018, p. 71).

In spite of these different vulnerabilities, it would be a mistake to frame

char contexts only in terms of environmental loss. In fact, the accretion of alluvial islands has long played an important role in accommodating populations affected by cyclones, floods and river erosion (

FAO 2011, p. 6). At the same time, (re)settlement on these islands has never been without contention, due to the widespread prevalence of land grabbing by powerful elites

6 (

Iqbal 2020;

Zaman 1991). In many ways,

chars function as “a sort of ‘endless’ agricultural frontier” (

Zaman and Alam 2021, p. 16), in the sense that they signal the continual reappearance, reappropriation and reclamation of lands. Whereas

chars were not always used for settled cultivation (

Chakraborty 2012;

Das 2021), the reclamation of alluvial islands became a popular mechanism for extending the tax and revenue base under British colonial rule (

Chakraborty 2012;

Iqbal 2010;

Zaman and Hossain 2021). Officially, these islands, together with other forested parts of the Bengal delta, were designated as “wastelands” after the introduction of the so-called Permanent Settlement in 1793 (

Iqbal 2010;

Mukherjee 2020). This piece of legislation was introduced by the British East India Company to stabilize property ownership and incentivize the landowning rural gentry to improve the agricultural productivity of their land by “fixing their tax obligations in perpetuity” (

Mukherjee 2020, p. 20). This fiction of permanency, however, was continuously undermined by the material fluctuations of Bengal’s riparian environment (

Mukherjee 2020, p. 29). Indeed, with regard to

char lands, it seems that the colonial state—in its efforts to cultivate and extract revenue from these “wastelands”—was forced to constantly revisit and work around its own legal provisions that insisted so strongly on qualities of permanence and fixity (

Iqbal 2010;

Mukherjee 2020).

The fact that

chars were effectively rendered anomalous under the Permanent Settlement highlights the troublesome relationship between the colonial state and the amphibious context of Bengal. In her work on the ecology of the Bengal delta,

Bhattacharyya (

2018, p. 4) describes how colonial interventions were aimed at molding the mobility of land and water masses into the “fixities of cartography, ownership and territorial sovereignty”. This resulted in the forcible legal, spatial and discursive separation of land and water. Moreover, by approaching land as more productive and useful than water, the colonial land revenue system also “began the long historical process of the definition of rivers as destructive in riverine Bengal and in need of control” (

Lahiri-Dutt and Samanta 2013, p. 11). These efforts thus sought to incapacitate water as a force of agency and change, as currents and rivers were encouraged—by dikes and walled-in embankments—to stay “within fixed courses to make the lands more permanent” (

Lahiri-Dutt and Samanta 2013, p. 11).

Chars expose the inevitable limitations of such endeavors and continue to offer a poignant reminder of both the fluid water–land boundary that colonial policies sought to render invisible and the forceful agency of the river itself.

3. Amphibious Uncertainties

Political, spatial and discursive efforts to fix the boundary between water and land also have epistemological repercussions.

Bhattacharyya (

2018, p. 5), for instance, argues that this forcible separation has led to “a collective amnesia about the mobility of this landscape”.

Saikia (

2019, p. xxviii) similarly observes that historians of the Bengal delta have been conditioned to take land as their point of departure, instead of thinking “like amphibians”. By stitching together “dry details of lands” they have effectively side-lined the river as a protagonist of history (

Saikia 2019, p. xxx). Such forms of forgetting are not unique to the context of Bengal. In fact, this disentanglement of land and water mirrors other forms of partitioning that characterize projects of modernity and coloniality, such as the separation of nature and society (

Latour 1993). However, now that the ongoing climate crisis has definitively exposed the fragility of such binaries, scholars have increasingly turned to concepts that express a greater degree of fluidity. For instance,

Krause and Strang (

2016, p. 633) argue that a focus on “watery relationships” can be instrumental in challenging the “conceptual and material boundedness and stability” of nature. Moreover, recent years have also seen attempts to give water and amphibious realities a more prominent role in conversations around climate change and the Anthropocene (

Crate 2011;

Hastrup and Hastrup 2016;

Helmreich 2011;

Jensen 2017;

Krause 2017;

Steinberg and Peters 2015;

Stensrud 2016).

This renewed interest in water and its qualities is unsurprising when considering that the climate crisis is very much tied to certain water-related disasters, including flooding, rising sea levels, melting ice, erosion, drought and excessive rainfall. Indeed, “water is often the medium through which the message of climate change is delivered” (

Jensen 2017, p. 225). This is also true for amphibious realities more generally, as oceans, tides and islands have been increasingly invoked to visualize and make sense of the Anthropocene. For instance,

Chandler and Pugh (

2021a, p. 1) suggest that thinking with islands can provide an antidote to the binaries of modernity—specifically the separation of humans and nature—as islands offer “key sites for understanding relational entanglements” in the Anthropocene. In a similar move,

Steinberg and Peters (

2015, p. 248) argue that the ocean provides the perfect spatial foundation for adding further depth to watery imaginations of a “world of flows, connections, liquidities, and becomings”, because it draws attention to the “chaotic but rhythmic turbulence of the material world”. Hence, this growing vocabulary of wetness is used to conjure an image of an open-ended, fluid, relational and turbulent world-in-formation, whilst also giving expression to the uncertainties of climate change. Indeed, according to

Hastrup and Hastrup (

2016, p. 3), such an explicit focus on water “highlights the need for rethinking the anthropological object in a fluid environment, by default connecting everybody across the globe in the anthropocene”.

Inevitably, there are limitations to the extent to which water, oceans and islands can be successfully used as “theory machines” in times of climate change. Whereas

Helmreich (

2011, p. 137) warns that “thinking with watery metaphors has become a prescriptivist enterprise”,

King (

2019, p. 8) observes that liquidity increasingly functions as a “totalizing metaphor”. The legitimate desire to break with Eurocentric epistemologies of coherence, stability and territoriality thus seems to have resulted in the analytical privileging of both fluidity and liquidity. Such a focus can easily obscure the fact that we are living in a world where nothing is solid or fluid per se. Rather, our world is perpetually transformed through vital processes of solid-becoming-fluid and fluid-becoming-solid (

Simonetti and Ingold 2018, p. 29). Likewise,

Peters and Steinberg (

2019, p. 293) point out that a focus on wetness alone disregards the fact that water and/or oceans are not simply liquid, but also solid (ice) and air (mist). Furthermore, this inclination to “think with” the wet and fluid qualities of our world helps to perpetuate the image of “water as a self-evidently “global” substance” (

Helmreich 2011, p. 137).

DeLoughrey and Flores (

2020, p. 132) argue that the theoretical work on maritime realities generally focuses on a “universalized ocean (as nonhuman nature) rather than a geographically and culturally specific place (as history)”. What becomes obscured by the image of a universalized ocean is the way in which human bodies that are racialized, sexed and gendered interact with more-than-human nature (

DeLoughrey and Flores 2020, p. 135). Moreover, a universalized idiom of wetness also seems to invoke a disembodied and generalized sense of existential uncertainty that is ostensibly shared by everyone connected through the Anthropocene.

There lies an epistemological risk in conflating fluidity and water with the “radical uncertainty of the climate” (

Chakrabarty 2014, p. 14). The question arises as to what extent such universalist metaphors for existential uncertainty resonate with communities who have long learnt to live without solid ground beneath their feet, inhabiting the world “not despite, but because of, fluctuations” (

Robertson 2018, p. 46). Indeed,

Robertson (

2018) suggests that for I-Kiribati navigators, environmental fluctuations and changes do not necessarily amount to forms of existential lost-ness, as navigators are used to attuning themselves to an oceanic environment that is constantly changing. The radical uncertainty of the climate might thus register differently in contexts of “continuous variation” (

Simonetti and Ingold 2018, p. 28). Furthermore, the imagery of the climate crisis as a pending existential crisis also erases the experiences of communities who have long been forced to deal with drastic and violent threats to their subsistence, survival and existence. Climate justice essayist

Mary Annaïse Heglar (

2019) argues that the strong emphasis on the climate crisis as an unprecedented, existential threat has obscured the fact that “history is littered with targeted—but no less deadly—existential threats for specific populations” (see also

Davis and Todd 2017;

Tuana 2019).

The question that emerges, then, is how we can “think with water” without drowning the diversified experiences of crisis, relatedness and adaptation that characterize the Anthropocene in a universalized ocean of uncertainty. How do we make sure that our theoretical engagements with water, oceans and islands do not merely reflect back our own thoughts?

Sheller (

2021) warns against forms of Anthropocene-thinking that rely too heavily on metaphors that have been soaked loose from their historical and political context. She is particularly critical of the way in which the theoretical usage of islands and archipelagos, which relies heavily on the work of Caribbean thinkers such as Edouard Glissant and Kamau Brathwaite, has been disconnected from the context of Caribbean praxis and politics in order to serve as “globalized philosophical devices” (

Sheller 2021, p. 2). Moreover, this focus on the material landscape and its solid-fluid forms averts attention away from the indistinct supernatural, immaterial or spiritual entities that constantly “dematerialize the physical plane of existence” (

Sheller 2021, p. 3). Inspired by

Brathwaite’s (

1975) poetic, oceanic imagery of “submerged mothers”,

Sheller (

2021, p. 3) argues that we need to pay greater attention to the ambiguous and opaque spirit-geographies that “may run through continents, under the ocean, and within forests”.

In the following sections, I take such more-than-human undercurrents as a point of departure for making sense of the way in which the radical uncertainties of the climate crisis become manifest in the amphibious context of Bengali char lands. Taking heed of such indistinct supernatural, immaterial or spiritual powers that reside below and beyond the water not only challenges probabilistic perspectives on climate change, but also helps to dematerialize the reified solid–fluid distinctions that continue to inform our understanding of the radical uncertainties of the Anthropocene. Indeed, such spiritual undercurrents gesture to experiences of uncertainty that transcend people’s struggles with the material land/waterscape they inhabit. Recognition of such spirit-geographies, moreover, also solicits attention to the fact that char dwellers are not merely balancing a perennially moving frontier between land and water, but are also caught up in an environment that—although fluid—is far from transparent. Hence, it paves the way for a perspective on climate change and adaptation that acknowledges the embodied and therefore gendered experiences of inhabiting a land/waterscape that is only knowable to some extent.

4. “Only God Knows”: Ambiguous Undercurrents

In recent years various scholars have reiterated the need for incorporating faith, religion and spirituality in analyses of climate change (

Bergmann 2009;

Donner 2007;

Haluza-DeLay 2014;

Hulme 2009;

Fair 2018;

Rubow and Bird 2016;

Stenmark 2015). For instance,

Hulme (

2009, p. 330) has argued that whereas “science has universalised and materialised climate change; we must now particularise and spiritualise it”. This call to spiritualize climate change is best understood as an attempt to account for the multiplicity of epistemes that help shape the truth of climate change. This growing awareness of the need for a plurality of perspectives has also led to a renewed interest in storytelling.

Stenmark (

2015, p. 935), for instance, argues that (religious) myths and stories can “help us judge and act in the midst of uncertainty”. To some extent, however, such an emphasis on story-telling as a mechanism for navigating uncertainty seems to overstate the sense-making potential of religious and spiritual narratives. Indeed,

Pearce (

2020) shows that local spirit stories in Ladakh often do not gravitate towards coherence or understanding. Instead, these stories “draw attention to areas of absence and irreducible doubt” and, as such, “reflect anxieties about the limitations of ordinary human knowledge and perception” (

Pearce 2020, p. 474). If we truly want to spiritualize climate change, we thus need to find ways to incorporate such experiences of unknowability into our understanding of crisis and adaptation; hence, taking seriously the many ways in which religion “gestures to that which lies beyond the limits of human knowledge” (

Premawardhana 2020, p. 43).

In the context of the Bengali

chars this element of ambiguity and unknowability becomes particularly clear from localized religious narratives that insist that there is “something” under the river that commands its currents and craves. For instance,

Hossain (

2018, p. 75) cites one of his interlocutors, a midwife for a local NGO, who contends that “there is, of course, something under the river, but we do not exactly know what it is.” Although the identity and ontological status of this underwater presence is not always specified, such claims do find resonance in both localized Hindu and Muslim traditions. While reflecting on Indian

char dwellers’ metaphorical and practical engagements with a more-than-human river,

Harms (

2014, p. 282) observes that these engagements “are instances of a localized syncretism and hybridity”.

Roy’s (

1983) work on Islamic syncretism in Bengal provides important context to such observations. Specifically,

Roy (

1983, p. 50) shows the linkages between those “deified animistic spirits like the tiger-god, the serpent-goddess, and the crocodile-goddess” that have long inhabited the Bengal delta and the localized Islamic tradition of

pirism.

Initially, the term

pir referred to sixteenth-century Muslim settlers who managed to establish themselves as figures of authority and guidance in Bengal and are closely associated with the intensification of forest clearance and land reclamation in the region (

Eaton 1993;

Van Schendel 2009).

Eaton (

1993, p. 219) describes how these charismatic figures were remembered for “their connection with the forest, a wild and dangerous domain that they were believed to have subdued; their connection with the supernatural world, a marvelous, powerful realm, with which they were believed to wield continuing influence; and their connection with mosques, which they were believed to have built, thereby institutionalizing the cult of Islam”. Today, the term

pir refers to a wide variety of entities, ranging from legendary historical figures, to

sufi guides and Islamic saints (

Roy 1983, pp. 50–51). The category also includes “metamorphosed Hindu and Buddhist divinities, and anthropomorphized animistic spirits and beliefs” (

Roy 1983, p. 51).

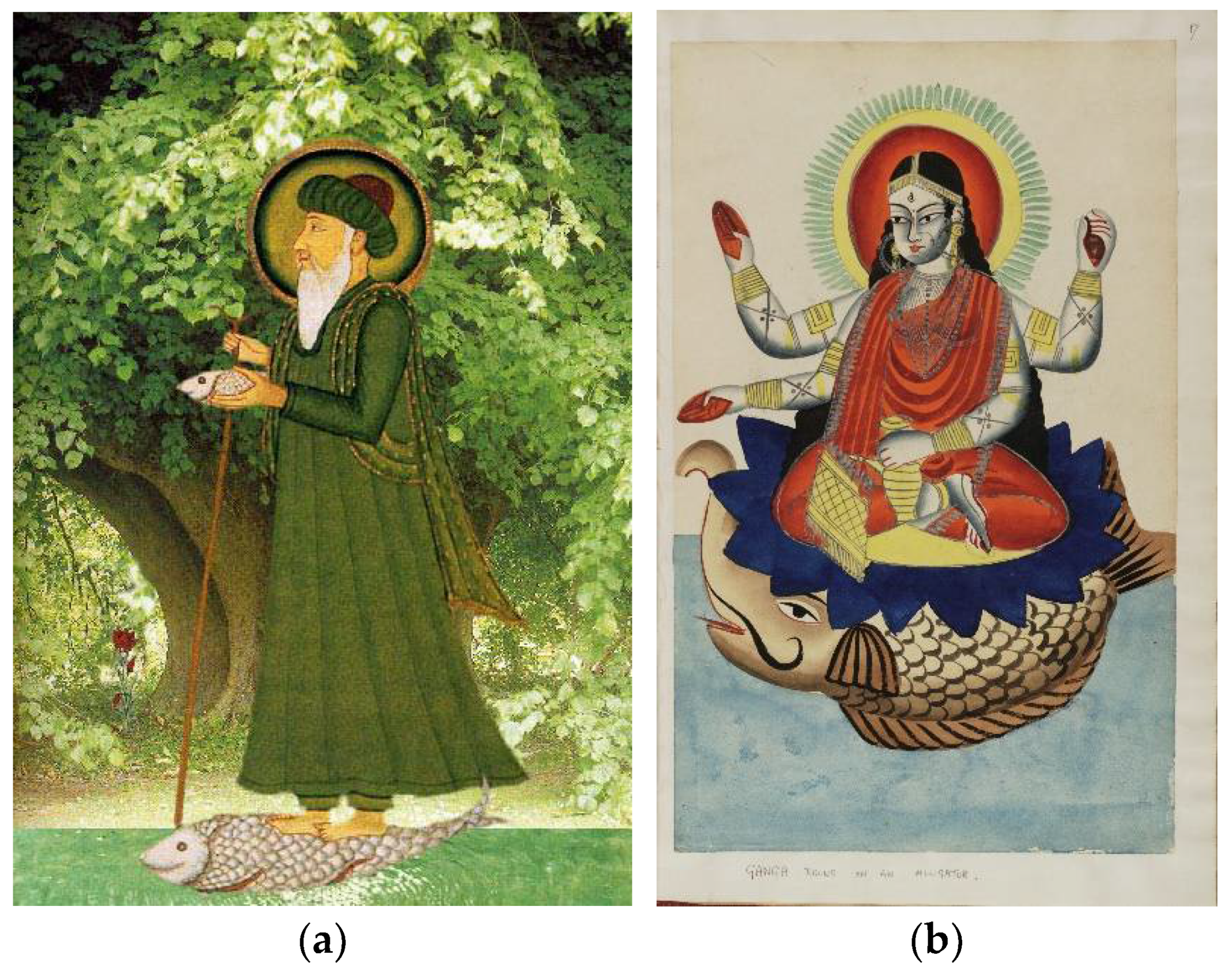

One

pir that is of particular relevance to the

char context is Khwaja Khizr. Khizr plays a role in both Islamic and Hindu mythology

7 and is “associated with beliefs in water-spirit” (

Roy 1983, p. 218). Often depicted as a white bearded man standing astride a fish (

Figure 1a), this living but invisible prophet is understood to control the water world (

Mukherjee 2008, p. 132). As is often the case with

pirs, the exact ontological status of Khwaja Khizr is shrouded in ambiguity. Indeed, scholars have alternately characterized him as a saint, prophet-saint or mysterious prophet-guide (

Omar 1993, p. 280). Although Khizr is not mentioned by name in the Qu’ran, his presence is associated with an enigmatic guide that makes his appearance in the eighteenth sura, a verse that narrates the allegorical story of the Prophet Moses’ search for truth (

Omar 1993, p). On his journey, Moses is accompanied by the mysterious figure of Khizr, whom he meets at the junction of two seas. Throughout their journey, Khizr carries out a variety of “inexplicable acts that fly in the face of mercy and wisdom” (

Khan 2016, p. 182). For instance, he creates a hole in the boat of a poor man that just provided passage to the two travelers. Although Moses is initially baffled by this seeming act of cruelty, Khizr later explains that it was necessary to temporarily put the man’s boat out of order to protect him from an evil king who wanted to confiscate his vessel (

Khan 2016, p. 182). The Qu’ranic story of Khizr (also known as Al-Khidr) thus highlights the finitude of human knowledge, teaching people that “since there is no end to the divine knowledge it is unwise to assume, as Moses did, that one may know it all” (

Omar 1993, p. 290).

In the context of Bengali

char lands this unknowability and inexplicability also extends to the figure of Khwaja Khizr himself, who is often envisioned as an underwater presence operating beyond the limits of human perception. As such, he is brought in relation to inexplicable cases of drowning (

Hossain 2018;

Khan 2016) and instances of river bank erosion (

Hossain 2018;

Khan 2016;

Shaw 1992;

Zaman 1999).

Hossain (

2018, p. 74) describes how one of his interlocutors, a young man from a

char in Northern Bangladesh, explained Khizr’s involvement in erosion. The man prefaced his story, which he had deduced from an Islamic sermon, by underscoring that although he did not know the exact cause of the hazards, he did believe that “there is a something under the river” (

Hossain 2018, p. 74). In the man’s localized narration, Khwaja Khizr featured as a prophet who had become immortal after drinking holy water from the ground. The storyteller explained that Khizr now lived underground, from where he ruled the water-world: “He is still alive. All the rivers listen to his command. He controls floods and river erosion when he wishes” (

Hossain 2018, p. 74). Likewise,

Zaman (

1999, p. 169) describes how Khizr appeared in local myths as the “outraged spirit” or “powerful king of all waters” who is “responsible for all hardship caused by erosion”. Sometimes, the living prophet was believed to be aided by “invisible manual workers” (

Shaw 1992, p. 208), who “dig under the soil below until big chunks fall down from above” (

Khan 2016, p. 186).

It should be noted that Khizr’s presence in the

chars, although well-documented, is also somewhat elusive.

Khan (

2016, p. 186), for instance, gives the example of an elderly

chaura man who is cited in the 2004 documentary film “Sand and Water” by Shaheen Dill-Riaz. The man underscored that he only knew of Khwaja Khizr through previous generations: “We haven’t seen it ourselves but it is really true. This lord of the water exists and so do his servants. In the winter months they measure how much earth they want to break away in the coming year. And when the monsoon floods come they fall upon the bank again” (

Khan 2016, p. 186). During her own fieldwork

Khan (

2016), moreover, observed that the presence of Khwaja Khizr seemed to be ebbing away from the particular

char where she carried out her research. Whereas in the past the

char dwellers used to observe “

Bera Bhasan”

8, a festival closely associated with Khwaja Khizr (see

Mukherjee 2008), this was no longer the case. When

Khan (

2016, p. 189) asked the

chaura women about Khizr, they professed “not to know anything” about him—or at least not in the same way as they knew about other holy figures. One senior lady further explained this lack of understanding: “He comes from the Book [a reference to the Qur’an] and that is where he lives. We common folk don’t have the book knowledge or courage to call on him” (

Khan 2016, p. 189). Khwaja Khizr, in this particular context, thus seemed to linger at the periphery of people’s understanding and knowledge of the world.

This degree of ambivalence also surrounds the river goddess Ganga (

Figure 1b), who is sometimes envisioned as Khizr’s consort (

Khan 2016). Indeed, in the context of

Khan’s (

2016) fieldwork, both of these divine powers were honored together during the festival of

Bera Bhasan and blamed together for the inexplicable drowning of young children. This potential for voraciousness also stands out in

Harms’ (

2014) work on localized interpretations of the river goddess Ganga at a coastal

char in the Indian part of the Ganges delta. The fact that the island was located at the place where the river and sea unite attracted numerous pilgrims who wanted to honor Ganga’s arrival on earth and immerse themselves in her waves (

Harms 2014, p. 283).

Harms (

2014, p. 284) however, observes that whereas the experiences of pilgrims were “unified by a sense of purity, auspiciousness and fertility imbued in the riverine goddess”, the islanders themselves often maintained a much more ambivalent relationship with Ganga Devi. Instead of nurturing and purifying, the goddess emerged in their narratives as a voracious and erratic entity, who would quite literally eat up their land (

Harms 2014, p. 291). This volatility was explained in terms of the “river’s grace” or the “river’s play” and brought in explicit relation to the cyclical experience of losing and regaining land. This becomes very clear from one of the following quotations that is presented by

Harms (

2014, p. 296): “One island will break, one island will come up. The grace of the river. One island breaks, but the soil is not eaten (up), the soil is broken (to pieces), again something else will be … this is what happens”. The prevailing notion that “Ganga gives and takes as she pleases” thus hints at the “continual presence of the unknowable” (

Pearce 2020, p. 489) in

char and riparian contexts.

Within the context of climate change, this deference to divine powers is often understood as evidence of a kind of “whatever will be, will be” attitude that indicates fatalism (

Rubow and Bird 2016). That this particular framing is also applied to

char contexts becomes clear from the fact that these sandbanks have often been described as the “land of Allah

jaane” (“only God knows”) (

Baqee 1998). This characterization also resonates with ethnographic examples that highlight emic understandings of river bank erosion as a curse or punishment from God. Indeed,

Zaman (

1988, p. 150) specifies how one of his interlocutors described erosion as “our

takdir (fate)” and stressed that

char dwellers had to “accept

Allahar ichha (the will of God)”. Although it is tempting to interpret these statements as a form of resignation or acquiescence, such an interpretation inevitably diminishes the resourceful ways in which

char dwellers have actually learnt to live with radical uncertainty. Instead, I would argue that these expressions speak to pervasive forms of unknowability that are perhaps difficult to grasp when having been conditioned, as many of us are, by the assumption that “the ground beneath one’s feet simply is there” (

Harms 2015, p. 75).

In the context of

chars, such forms of unknowability are very much rooted in cyclical experiences of losing and regaining land. Indeed, the belief that Allah, Ganga Devi and Khwaja Khizr all give and take away land as they please is affirmed by the various sequences of “migration, settlement and destruction” (

Harms 2015, p. 72) that

char dwellers move through on a regular basis. This also means that environmental loss is not necessarily experienced as a definitive or unidirectional event in

char contexts. Rather, land loss and return appear as two sides of the same coin, with divine powers ultimately deciding how the coin falls. This means that, even amidst pervasive uncertainty, there always looms the possibility of return. This becomes clear from the following quotation by one of

Hossain’s (

2018, p. 73) interlocutors, who insisted that “only Allah knows why hazards take place on the

chars”. His comment did not merely signal a degree of helplessness and resignation in the face of overwhelming losses, but left considerable room for experiences of return. The man emphasized how his current living place had been underwater a few years ago: “But, look at this place now. Floods left the area as a sandy char. I moved here and built my home. The river cannot flow without Allah’s command. The river erodes the

chars, but Allah saves us always” (

Hossain 2018, p. 73).

This openness to the possibility of divine intervention is often “treated as a barrier to climate adaptation” (

Fair 2018, p. 2). However, the assumption that underlies such interpretations is that people’s religious experiences are founded on a sense of certainty about what the future will bring

9. The above examples, however, have highlighted the myriad ways in which localized religious beliefs gesture “to that which lies beyond the limits of human knowledge” (

Premawardhana 2020, p. 43). The work of

Khan (

2014a), moreover, suggests that this belief in the possibility of return does not necessarily equate to existential at-peace-ness. Whereas experiences of cyclicality are often intuitively understood as harmonious and balanced,

Khan (

2014a) shows that the spiritual anticipation of return can be a profoundly ambivalent experience. This becomes particularly clear from her account of an Islamic sermon that she attended during her fieldwork in Sirajganj. To

Khan’s (

2014a) surprise, the preacher stressed that, in the advent of Judgment Day,

char dwellers would return to Earth as dogs to follow the Islamic anti-Christ, Dajjal.

Khan (

2014a, pp. 253–4) points out that this sermon and its curious promise of reincarnation, constituted a considerable break from otherwise linear eschatological trajectories in Islam. Moreover, considering the ambivalent status of dogs on the island as “repugnant others” and the reference to Dajjal, this promise of continuation and return did not necessarily present itself as something to hold out for. Rather, it seemed to signal a form of return to “a diminished form of life” (

Khan 2014a, p. 262).

The way in which

char dwellers anticipate the return of land is similarly shrouded in ambivalence. For instance,

Khan (

2014a, p. 258) cites an elderly woman who pondered the following: “If the earth (

mati) breaks so much, how do we stay

manush (human)?” This question unmistakably signals a deep, existential concern over conditions of environmental fluctuation and the possible intensification of suffering. It gives expression to the fear that the infinite cycle of land loss and return might spiral out or down in ways that could threaten the reproduction of lives and livelihoods on the

chars. This looming sense of disequilibrium alludes to the ways in which the disturbances and ruptures of the climate crisis might become recognizable amidst the ambivalences of an unpredictable and oftentimes erratic environment that is only knowable to some extent. Moreover, it also poses the question as to what climate adaptation means for both men and women, when such practices are inevitably premised on people’s slippery entanglements with a far from predictable or knowable river.

5. “Rolling Like Silt”: Gendered Experiences of Disequilibirum and Adaptation

In the previous section I have shown that

char dwellers find themselves existentially caught up in an environment that, although fluid, is far from transparent. Living with water, in this particular context, also implies living with ambiguous transcendental powers who often behave in ways that defy human interpretation. The question thus arises as to what adaptation means in a context that is shaped by more-than-human forces who destabilize categories of likeliness and unlikeliness and who continuously “dematerialize the plane of psychical existence” (

Sheller 2021, p. 3). Recent years have seen emphatic calls to incorporate “local” and “traditional” environmental knowledge into understandings of climate change adaptation. Yet, while such calls are very necessary, they do not really speak to the many ways in which landscapes and waterscapes present themselves as unknowable to their inhabitants. Indeed, in the context of

chars, there seems to be a disconnect between the well-intended advice by NGOs to “set aside money, food staples, and a portable mud stove” to prepare for instances of flooding and erosion (

Khan 2016, p. 184) and the gendered, embodied and existential experience of continuously having to put oneself “dangerously in water’s way” (

Van Schendel 2009, p. 7).

None of this means that

char communities are not constantly and skillfully making adjustments in order to craft a sense of continuity across ever-shifting

char lands. Indeed, villages and settlements that have been lost through riverbank erosion are often reconstituted in very similar ways after the land reappears.

Khan (

2014b, p. 295) for instance mentions a village that “was named after a village of the same name eroded by the river a long time ago and considered to have been reconstituted and eroded many times since”.

Indra (

2000), moreover, observes that houses were often built in such a way as to accommodate their immediate relocation in the case of erosion. Very few dwellings were constructed out of brick. Instead, the wall and ceiling sections often consisted of woven sheets of catkin, a type of coarse grass.

Indra (

2000, p. 11) elaborates that each of these modules could be transported rapidly “by no more than six to eight men”, with the result that a typical house could be “re-erected in a day or two, using only household labor”. This entailed moving the house itself, as well as furniture, animals and sometimes even trees. A similar degree of continuity was maintained through instances of severe flooding. Indeed,

Shaw (

1992, p. 204) describes how houses in flood prone areas would usually have a “false roof” where goods could be stored. Goats and cattle were moved to bamboo platforms, whereas whole families would retreat onto the bed to live and cook as soon as the water entered their houses (

Shaw 1992, p. 204).

Such adjustments, which take an extraordinary toll on women in particular, bear testimony to the ways in which communities learn to “dance” with the “changeable moods of the river, trying to make the best of their vulnerable situation in a marginal environment” (

Lahiri-Dutt and Samanta 2013, p. 149). At the same time, this “dance” does not seem to be harmonious or reciprocal. One of the

chaura men that

Zaman (

1988, p. 66) interviewed during his research described the experience of living with erosion as follows: “We have to keep rolling like silt”. He added: “For us, it is normal; we expect it to happen, and happen any time. You see, I have been displaced twelve times in the past twenty years; God knows how many more times I have to move before I die!” (

Zaman 1988, p. 66). This notion of “rolling with the river” seems to highlight the tension between disequilibrium and adaptation that is at the heart of the climate crisis. On the one hand, it gestures towards the positive possibility of being able to move with the river, while also alluding to the possibility of being overwhelmed or even consumed by the river and its imponderable forces. The metaphor thus leaves room for people’s intuitive attunement to the moods and rhythms of the river, while also gesturing towards its churning, spiraling and destabilizing qualities.

This destabilizing potential of the river does not only become manifest through instances of erosion, but also through inexplicable cases of drowning. As we have seen, such tragedies are frequently attributed to Khwaja Khizr, Ganga Devi or more amorphous water entities. This resonates with research conducted by

Blum et al. (

2009) on childhood drowning in a riverine community in Bangladesh.

Blum et al. (

2009, p. 1723) observed how interviewees would attribute instances of childhood drowning to dangerous river spirits who would lure, smack or pull children into the water, sometimes leaving “finger prints” in the process. While some people thought the river goddess Ganga, locally known as Gongima, to be responsible, others spoke about an unspecified evil force. Moreover, various mothers mentioned a mysterious form of forgetfulness, cast onto them by an evil spirit, that mesmerized them and made them forget or lose sight of their children (

Blum et al. 2009, p. 1723). Hence, the dangerous lure of the river is brought in explicit connection with lapses of memory or perception to explain cases of childhood drowning. The fact that it was women or mothers who were supposed to look after their children while also attending to various other chores speaks to the gendered burden of inhabiting this imponderable and elusive land/waterscape.

There are various ways in which the act of dancing, moving or rolling with the river is gendered. Women are not only uniquely exposed to this amphibious landscape, as they are believed to stand a higher risk of being pulled into the river by supernatural forces (

Shaw 1992, p. 208), but men and women also play different roles in crafting a sense of continuity amidst this variable landscape. It is important to note that the gendered division of labor on the

chars is quite distinct from that in mainland rural communities.

Zaman (

1988, p. 74) points out that whereas in rural Bangladesh it is usually considered desirable for women to work around the house, taking care of tasks such as cooking, childcare, raising poultry and post-harvest agricultural activities, this is not necessarily the case on the

chars. This difference is also manifest in practices of

purdah.

Purdah refers to a set of cultural practices—including veiling and seclusion—that are common throughout the South Asian region and are aimed at withdrawing the female body from public view. This practice, moreover, is also supposed to protect women from attracting

bhut (ghosts) or being pulled into the river by water spirits such as Khizr (

Shaw 1992, p. 208). In spite of these gendered risks, practices of purdah are often less restrictive on

char lands than in mainland communities, considering that the labor of women is much needed beyond the realm of the home.

Indra (

2000, p. 14) observes that “at certain times of the year, over a quarter of embankment households are headed by women”.

This overrepresentation of women on the

chars is caused by the long-term absence of male household members due to the practices of labor migration. Although both male and female

chauras engage in practices of migration, this strategy has been particularly common among men

10, especially during the lean season when opportunities for agricultural labor are scarce.

Lahiri-Dutt and Samanta (

2013, p. 169) observe that since most of the land on the

chars remains fallow during the lean season, “some agricultural workers go to the mainland to look for seasonal work, but women tend not to travel such long distances and instead stay back to look after the household.”

Hossain (

2018, p. 14) further elaborates that

char dwellers have long learnt to diversify their income strategies in order to cope with frequent floods, heavy monsoon rain and riverbank erosion. Livelihood strategies therefore often consist of a combination of farming, raising livestock, fishing and seasonal migration. Some men permanently work in households off the embankments (

Indra 2000, p. 14), whereas others travel to cities such as Dhaka to temporarily work as rickshaw pullers (

Hossain 2018, p. 221).

Sometimes such migration trajectories would evolve into something more permanent. For instance, when rural–urban migrants succeeded in bringing their wives and families with them to the city (

Hossain 2018, p. 226). However, due to increasing living costs in cities such as Dhaka, this is not particularly easy. More often than not, male migration patterns follow a circular logic and are aimed at fostering a sense of continuity across the different agricultural seasons. Indeed,

Hossain (

2018, p. 228) describes how for small peasant farmers, seasonal rural–urban migration was a “way of returning credit and saving capital for the following agriculture season”. Hence, migration trajectories are not just oriented away from the chars, but also offer a means to return to the islands. As such, they are part of the concerted efforts by

chauras to craft a sense of continuity across shifting

char lands. However, the burden of actually maintaining homes and households over time often falls on women.

Lein (

2009, p. 108) observes that whereas the shifting of homesteads in periods of erosion requires extra labor input from all household members, women are usually the ones to properly re-establish the household after relocation. They are responsible for constructing the raised mud platform that houses are built on, for making a new oven and establishing a new home garden (

Lein 2009, p. 108). Moreover, women also play a crucial role in mobilizing extended kin relations and negotiating opportunities for resettlement (

Lein 2009, p. 108). It is customary for those who have lost their land to settle rent-free on other people’s land, yet such patron–client arrangements require considerable negotiation and personal investment (

Lein 2009, p. 108).

From the above examples it becomes clear that

char women play a crucial role in fostering a sense of continuity through various cycles of loss and return. This work extends far beyond the actual moment of relocation. Indeed,

Indra (

2000, p. 13) points out that “having an established place gives people the physical means to extend women’s activities outside the household perimeter”.

Lahiri-Dutt and Samanta (

2013, p. 188–91) list some of the tasks that

char women, especially those belonging to poor or landless households, are commonly engaged in, including domestic work, agricultural wage labor, rearing animals, collecting fodder for domestic animals, fishing and collecting fuel for cooking. This considerable workload highlights how “dancing with the river” or “rolling like silt” is a gendered act. Indeed,

Lahiri-Dutt and Samanta (

2013, p. 131) observe that

char women “are overburdened with physical labor from dawn to dusk”, while also pointing out that women receive and give more kin help than the men. Whereas “men give money to kin, women give time or contacts” (

Lahiri-Dutt and Samanta 2013, p. 131).

Similarly, the work of

Lein (

2009, p. 108) makes clear that the ways in which the seemingly infinite cycle of land loss and return spirals down and outwards results in experiences of disequilibrium that are also very much gendered. Indeed, he observes that with the increased frequency of erosion, some women were holding out for a life beyond the

chars, as they felt that “the work of rebuilding and reestablishing of new homesteads had become too onerous over the last few years” (

Lein 2009, p. 108).

Lahiri-Dutt and Samanta (

2013, p. 191) similarly observe that “women somehow manage to bear the burdensome life of the chars while wanting to leave the area permanently as soon as their husbands can afford to”. These experiences of exhaustion thus highlight the tension between moving with the river and (nearly) being overwhelmed by it.

These various examples thus reiterate that the gendered and embodied act of “dancing with the river”, far from signaling a harmonious or reciprocal relation, is continuously destabilized by the churning and spiraling qualities of this amphibious landscape. On the one hand, this potential for being overwhelmed by an environment that is only knowable to some extent, seems to be inherent to

char geographies—as becomes clear from the connections that are forged between instances of childhood drowning and the lure of more-than-human underwater forces. However, at the same time, the gendered experiences of exhaustion that

Lein (

2009) foregrounds in his work unmistakably gesture towards the ways in which climate change and erosion shape and warp existing and familiar forms of uncertainty and unknowability. Dancing or even rolling with the river and its imponderable forces might be nothing new, but the quickening pace of this dance can nonetheless leave people overburdened and exhausted in ways that allude to a looming sense of disequilibrium.

6. Conclusions

Bengali

char lands highlight the complexities of understanding environmental loss and adaptation in the context of the Anthropocene. In many ways, these amphibious realities complicate the conventional images—of excessive floods, sinking islands and eroding river banks—that are used to capture the disastrous effects of the climate crisis, considering that

chars are simultaneously disappearing and reemerging. Even as the earth keeps breaking, it also continues to be reconstituted (

Khan 2014a, p. 262). Neither environmental loss nor adaptation can be understood as a linear or unidirectional relation in this context, as becomes clear from the fact that people’s material and spiritual engagements with this land/waterscape are very much rooted in the anticipation of both land loss and return. Instead, experiences of disequilibrium and adaptation are shaped by the way in which time contracts and expands between moments of erosion and reconstitution. In this paper I have explored what uncertainty means in a context such as this where categories of likeliness and unlikeliness are shaped and warped by an increasingly imponderable cyclicality.

Chakrabarty (

2014, p. 23) has provocatively argued that “the climate crisis is about waking up to the rude shock of the planet’s otherness”. The more-than-human forces that are associated with river bank erosion and inexplicable cases of drowning in

char contexts, provide an apt example of such forms of otherness. These immaterial, churning and spiraling underwater forces do not only gesture towards environmental realities that cannot “be tamed by human knowledge” (

Chakrabarty 2014, p. 4), but they also highlight that spiritual experiences do not always gravitate towards the sort of meaningful coherence that is often associated with religious storytelling. This element of unknowability is reinforced by the slippery ontological status of some of these underwater forces. Khwaja Khizr, for instance, cannot be tied to one particular religious tradition and, depending on the context, is viewed as either a saint, prophet-saint, mysterious prophet-guide, water spirit or water deity. Moreover, in the

char context, this invisible presence was sometimes simply referred to as “something under the river” (

Hossain 2018, p. 74) or as a force that people knew of, but could not quite grasp (see

Khan 2016). Such examples thus highlight how experiences of environmental vulnerability are tied up with unpredictable and unknowable forces that linger at the periphery of people’s perception and knowledge of the world.

By focusing explicitly on the divine, immaterial and spiritual powers that reside below and beyond the river, I have also tried to move beyond the reified fluid–solid distinctions that are so often invoked to frame, capture and theorize the uncertainties of the Anthropocene. Instead, I have addressed attention to those divine underwater forces—often described in terms of their playful, unpredictable or even erratic nature—that “dematerialize the physical plane of existence” (

Sheller 2021, p. 3). Whereas the relation between environmental loss and adaptation is often framed as a struggle between people and their material land/waterscape, this does not fully capture the situation in

char contexts. Indeed, it seems that

char dwellers are not necessarily struggling to hold on to a particular material place, but instead, are struggling to craft a sense of continuity amidst cyclical and spiraling experiences of land loss and return. As we have seen, men and women play different roles amidst this increasingly exhausting dance with an unpredictable river. Whereas the need to diversify income strategies has prompted many men to engage in practices of labor migration, women are often the ones responsible for maintaining homes and households across ever-shifting

char lands. They are the ones who have to keep up with the steps of the river’s quickening choreography, while also making sure that young children are not taken by its ominous undercurrents. The exhaustion and anxieties that coincide with this balancing act highlight the importance of paying attention to the embodied, emotional and gendered aspects of engaging with a land/waterscape that is only knowable to some extent.

There are various lines of questioning that could be developed further from this particular vantage point. For instance, whereas this paper has focused mostly on the way in which women are caught up in this amphibious landscape, further attention could be paid to the ways in which the embodied relation between masculinity and land is made and unmade by these shifting configurations of sand, silt and water. Moreover, the diverse ways in which people are exposed to this amphibious landscape are not only shaped by gender, but also by other structured positions, such as age, marital status, employment and landownership (see

Indra 2000). Diversifying our imagination of environmental vulnerabilities, however, also requires a diverse understanding of the way in which the existential uncertainties of the Anthropocene are experienced. The literature on

chars challenges some of the hegemonic framings of these uncertainties. It alludes to that fact that, whereas for many people in the global North, an awareness of the climate crisis might indeed manifest itself as a crude awakening to the planet’s unfathomable otherness, this does not necessarily hold true for communities who have never claimed to fully know the world or for whom the erratic agency of external forces has long been a familiar constant.