1. Introduction

The keynote for the

14th International Conference on the Social Context of Death, Dying and Disposal, hosted by the University of Bath in September 2019, proved to be a charged site of public confrontation between the modern UK funeral industry and its discontents. After the Head of Insight and External Affairs at the funeral company

Dignity gave his presentation on consumer trends in the British funeral market (including rising rates of direct cremation

1 and pauper funerals), the audience stirred, and the first question was delivered from the back of the room:

Will you recognise that it is the patriarchal take-over of the funeral industry that has destroyed our culture’s relationship to death and created these problems?2

Subsequent questions, several from independent funeral directors, were similarly critical of the funeral industry in the UK and beyond.

Dignity has attracted significant attention over recent years, given its pursuit of market consolidation (acquiring over 350 individual companies), its high profit margins (just under 40%), and its consistent rises in funeral prices (an annual increase of 7% since 2002) (

Fletcher and McGowan 2020). At the conference, a contemporaneous collaboration between

Dignity and government regulators drew particular ire.

The specific castigation of contemporary death care communicated through the first question can only be understood when we know the identity of its asker: Zenith Virago, an Australian death educator, author, celebrant, ritualist, self-styled ‘deathwalker’, i.e., somebody who “walks with people through the dying process” (

Natural Death Care Centre 2017), and founder of the

Natural Death Care Centre in Byron Bay. Zenith has emerged as an internationally recognised figure in what we refer to with the umbrella term ‘New Death Movement’ (hereafter, ‘NDM’). Her description of the contemporary funeral industry as ‘patriarchal’ condenses one powerful line of critique in this movement against modern ways of ‘doing death’.

The NDM is a diverse and dispersed social–spiritual movement known by many names, including the “natural death movement” (

Olson 2018), “death positivity” (

Doughty 2011), the “home funeral movement”, or the “Happy Death Movement” (

Lofland 1978). It spans the gambit of those promoting death cafés, home hospice and funerals, shamanic ritual, medical history, and green burial. In broad terms, the NDM works to reframe society’s relationship to death via a return to “traditional” or “natural” ways of dying and death, such as at-home care of the body, shrouded burial, and community-led rituals. Over the last decade, the movement appears to have gained a new critical mass, with entry into the popular consciousness and the industry. For example,

The Atlantic declared that “death is having a moment” (

Hayasaki 2013) and the (

Global Wellness Summit 2019) (the peak international forum for wellness industry leaders) selected ‘Dying Well’ as one of its top ten trends.

The NDM has roots in earlier social movements, in particular 1970s groups concerned with death awareness, including the Death Acceptance Movement, the Death with Dignity Movement, and the Natural Death Movement (

Lofland 1978;

Troyer 2020). Not coincidentally, these movements arose during an age of both secularization and the rise of new religious movements, when religions—which had once provided people with rich rituals and meta-narratives on life and death—began to lose their hold on society (

Davies 2002). Despite this shrinking social role of religious institutions, the quest for meaning-making in the face of death was profound, and in the new spiritual approaches to death that emerged, gender was critical. For example, as Brenda

Mathijssen (

2017) describes for the Dutch context, in light of the 1970s secularisation, women acquired a more prominent role in the national death care industry, especially as ‘independent’ ritual coaches (see also

Mathijssen and Venhorst 2019).

However, the NDM does more than facilitate the re-ritualization of death. It mounts an overarching critique of death as it came to be managed in the West in the late 20th century. In this paper, we articulate the contours of this critique by investigating contemporary death care as a ‘Death Industrial Complex’, or DIC. This Complex stands accused of sequestering the realities of death from everyday life (

Giddens 1991;

Mellor and Shilling 1993), promoting a culture that denies our mortality (

Becker 1973), medicalising the dying process (

Burgess 1993) and professionalising posthumous care (

Howarth 1997), resulting in death becoming anthropocentric, clinical, and capitalist, to the detriment of the psycho-spiritual health of the dying, bereaved, broader community, and health of the planet. More fundamentally, the DIC is seen to distort humanity’s relationship to our own mortality, creating a deep cleave between society and nature. In contrast, the NDM proposes embracing, rather than denying, the natural rhythms of birth, growth, and decay. In this endeavour, gender plays a central, if sometimes overlooked, role. Not only are the leading figures and majority of members of the NDM women, but many also explicitly critique how the DIC appears to devalue feminine knowledge, embodied skills, caring labours, and qualities such as empathy and creativity. By promoting a feminine-coded care for nature in new death care practices and products, NDM works to build an alternative model of a good death within the Anthropocene.

In this article, we critically examine the activities of the NDM and ask how gender is positioned in the effort to re-make death care. This includes the care-taking prior to death, the dying process itself, and the handling of the body and memorialization afterwards. As we will show, gender is cast both as the genesis of issues in death care, as well as its solution, in a variety of products and services that explicitly emphasize feminine qualities and natural cycles, making the processes almost exclusively female. We consider two examples from different sectors of the NDM. The first involves the work of ‘death doulas’: (mostly) women who guide the dying, dead, and bereaved toward “good” or “positive” death experiences by creating new ritual traditions and caring practices. The second case study involves the emergence of arboreal necro-technologies designed to turn the deceased’s remains into trees, which are heavily marketed through fertility imagery. Read together, the two cases show death to be a site for revising humanity’s relationship to nature by checking an industry that is described as masculine and dominion driven, and by highlighting spiritual values often associated with the feminine. However, as we conclude, the re-feminization of death care is multifaceted, and NDM advocates inevitably operate within the same system they critique.

The article draws on the study of online platforms (from September 2020 to February 2021), such as the personal websites of death doulas, promotional websites of new necro-technologies, customer reviews and testimonials, and other related media coverage. Discourse analysis was used to identify key concepts and terms, as well as key imaginaries used. Complementary to this material, author Gould conducted fieldwork at five different NDM events and meet-ups in Australia during 2019 and virtual fieldwork in events and social media groups hosted by groups in the USA and UK during 2020. Gould undertook a three-day intensive death doula training course, conducted interviews with ten women who identify as part of the NDM, and participated in Death Cafes and community events for ‘Dying to Know Day’ (8 August 2019).

2. The Problem with Death Care

The New Death Movement defines itself in juxtaposition to how people “do death” in the contemporary West and the perceived harms of this system for the dying, the living, and the planet. This system has a history, one which Phillipe Ariès began to untangle in

Essais sur l’Histoire de la Mort en Occident (

Ariès 1975) and

L’Homme devant la Mort (

Ariès 1977). Ariès describes a shift in “death mentalities” between the early medieval period to the late 20th century, in which death transitioned from being “tame” to “wild”. In medieval times, death was a normal and customary part of life. People were aware of their mortality and prepared for their own deaths through ceremony, dying was a public event attended by all, including children, and mourning was short-lived and ritualized. Death was “both familiar and near, evoking no great fear or awe” (p. 13). However, by the time Ariès wrote his seminal works, death had become “wild” and “so frightful that we dare not utter its name” (ibid.). It had become something largely sequestered from everyday life, controlled within a scientific world view, and dominated by medical and funeral professionals.

Other scholars similarly described a changing attitude towards death over the past century. Anthony

Giddens (

1991) describes how in the period of late modernity, the organization and experience of death became privatized, with both dead bodies and discussions of dying removed from public view. Secularization and the shrinking scope of sacred rites further contributed to this sequestration, whereby communal responses to death were replaced by individual acts of grief and remembrance. Scholars have subsequently described how religious authority was superseded by science in the management of major rites of passage, both natal (birth) and fatal (death), producing a disenchanted model of dying (Harvey 1997;

Howarth 1996;

Rundblad 1995).

The gendered dimensions of this transformation up to the 20th century should not be overlooked. As the funeral industry professionalised in many locations around the world, care of the dead body shifted from the domestic space to the mortuary and from women carers to male mortuary professionals. The timeline of professionalisation varies between locations. In the USA, before the Civil War, so-called “shrouding women” were responsible for the care and treatment of a corpse, alongside the sick and dying (

Olson 2018, p. 195;

Trompette and Lemonnier 2009). In the United Kingdom, Glennys

Howarth (

1996, p. 56) describes a similar pattern of change in funerary culture after the Second World War. As a result of this shift, the “once simple and natural act of laying our dead to rest has been transmogrified into a largescale industrial operation that, like any other manufacturing process, requires the input of vast amounts of energy and raw materials and leaves a trail of environmental damage in its wake” (

Harris 2007, p. 6). Consequently, the practice of caring for the dead became a major commercial enterprise, in which people overwhelmingly die in institutions, their bodies are taken into custody by funeral companies who sanitize and (often) embalm them, expensive funeral services for a tightly-scripted last farewell are arranged, and bodies are buried in formal oak caskets or sent directly to crematoria.

The late 20th and early 21st centuries have witnessed a reverse trend. After decades or even centuries of being “displaced by men through gatekeeping techniques and professionalisation” (

Donely 2014, p. 16) women nowadays re-enter Western funeral industries in large numbers. This shift has coincided with a decrease in male clerical power, and an increase in feminine spirituality and women striving for formal religious office (

Woodhead 2007). In the current post-secular age, religious and spiritual ideas are being re-invented, especially those related to the domestic sphere (

Woodhead 2008). As religion—or better, spirituality—became ‘feminized’ (

Dubisch 2016;

Gemzoë and Keinänen 2016, pp. 16–17), so has the death care industry.

In working to reclaim power over death, the arguments forwarded by the NDM construct sharp juxtapositions between industry and hand-labour, masculinity and femininity, social artifice and nature, the DIC and a new way of doing death (see

Table 1). For example, the mission statement for

The Order of the Good Death calls for “honest, open engagement with death” in contrast to the “closed doors” of the status quo and a “death positive” culture in contrast to a “death phobic” one.

3 Elizabeth

Fournier (

2018, p. 2), self-styled ‘Green Reaper’ and author of

The Green Burial Guidebook, similarly contrasts the “typical ceremony run by a funeral company”, involving embalming and a casket burial at a traditional cemetery which “fails to provide satisfying ritual of mourning” and has “lasting financial and ecological burdens” with an approach to death that is “simple,” “hands-on” and “green”. The End of Life Doula

Directory (

2017), an organisation operating in Australia, draws particular contrast between “standard funeral industry-led Death Care” and home care, which is “more affordable, holistic and respectful to the environment”.

Critiques of DIC’s motivations are not new nor exclusive to the NDM. Perhaps the most damning takedown is Jessica Mitford’s investigative journalism classic

The American Way of Death (

Mitford 1963), which contends that death has become commercialised and needlessly expensive. Mitford particularly condemns the funeral industry for unscrupulous tactics of ‘up-selling’ to push unnecessary purchases on grieving families. In Australia today, the funeral, crematoria and cemeteries sector brings in AUD

$1.7 bn total revenue per year with 2.7% annual growth and a 19.3% profit margin (

IBIS World 2020). An average funeral in the Netherlands costs anywhere between €6500 and 8000, three to four times an average monthly net wage (

Mathijssen and Venhorst 2019, p. 57). Massive international funeral corporations operate internationally as monopolies and stand accused of multiple counts of anticompetition behaviours, opaque pricing, breaches of duty of care, and exploitative upselling practices (

Choice 2020). For those with limited financial resources, death can impose extreme burdens. Recent reports into the rise of so-called “pauper funerals” in the UK (

ITV News 2018) emphasize the extent to which death is structured by the inequalities of capitalism.

Others critique DIC for its environmental externalities. Conventional means of handling dead bodies consume nonrenewable resources and damage surrounding ecosystems. In many countries, formal burial in a cemetery entails the use of hardwoods, copper, bronze, and steel for coffins as well as reinforced concrete for lining graves (

Harker 2012), all technologies designed to resist decomposition (

Barnett 2018). Decomposed remains result in a presence of groundwater pollutants in soils (

Hart 2005), while above ground, formal lawn cemeteries consume many thousands of litres of water for maintenance. The practice of embalming has drawn particular critique, with nearly 800,000 gallons of formaldehyde-based embalming fluid buried in USA cemeteries alone every year. Cremation also produces high levels of airborne emissions of mercury and other heavy metals (

Green et al. 2012), and often consumes coal, natural gas, or other fuels (

Barnett 2018). In response to these detrimental effects of burial and cremation, new necro-technologies for handling the body have been developed over the past decades, the most successful one for now being natural burial which provides “an environmentally sensitive approach to the care of deceased people and the landscape” (

Clayden et al. 2010, p. 148; see also

Davies 2005). Other more innovate technologies include alkaline hydrolysis (dissolving the body in water and/or acid), natural organic reduction (composting), and promession/ecolation/cryomation (freeze drying and shattering the body).

Ecological charges speak more fundamentally to the psychological and spiritual dimensions of the NDM’s critique of modern death. For many NDM advocates, the sequestration of the dying and dead from life is, if not unnatural, then at least unhelpful. Here, Ernest Becker’s

The Denial of Death (1973) is a touchstone text. Becker’s key argument is that civilization is an elaborate, symbolic defence mechanism against our own mortality. In the past, religions provided such mechanisms, by controlling death via ritual and by promising an existence beyond our limited time on earth. With secularisation and the disappearance of ecclesial death rituals,

Mellor and Shilling (

1993, p. 427) argue that “modernity has deprived increasing numbers of people with the means of containing it in an overarching, existentially meaningful, ritual structure”. The strategies they find for “dealing with death” are denounced as “precarious and problematic… resulting in no less than an existential crisis” (ibid.). The modern age is certainly not without ritual. However, contemporary funerals, as one-size-fits-all products, have been critiqued as “McFunerals” (

Suzuki 2003) offered by “Funerals-R-Us” corporates (

Lynch 2004).

Given the arguments of the NDM and of scholars, a feminine approach to death, dying, and disposal might appear the ultimate solution to the ecological, economic and spiritual damages wrought by DIC. However, two critical notes need to be made about how this argument proceeds. First, the gendered relation between nature and death as forwarded by the NDM is not essential or constant, but a constructed relation of gendered discourse. These discourses maintain existing binaries, at times even strengthening them. As feminist scholars (e.g.,

Fausto-Sterling 2000;

Martin 1987;

Ortner 1972) have argued, dualisms between women (read: nature, irrationality, the body, impurity) and men (read: culture, rationality, the intellect, purity) erroneously appear naturalized and immutable, resulting in violence to that which exceeds or confuses their boundaries and limits to the power of those performing within the bounds of gendered archetype. For example, in the contemporary funeral sector, essentialist ideals of ‘feminine’ skills (such as communication, empathy, and caregiving), which were once used to exclude women, are now employed to justify their participation in the sector (

Pruitt 2017). Although the movement of women into the male-dominated funeral industry might be expected to improve women’s status in the workplace, it rather entrenches gender inequality (see

Donely 2014). Second, the strict dichotomy set up between NDM and DIC often does not hold up when we examine the messy inter-relation and interdependence of these communities and their financial motivations. In the coming sections, we will describe two examples that illustrate this last point. We will revisit this critique in the conclusion.

3. One: Death Doulas

Death doulas offer a holistic array of services across the human experience of death. These range from delivering death education in primary schools, to assisting people to pre-plan their funeral, and to tending the dying, creating rituals, and holding community ‘Day of the Dead’ memorial events. Many adopt a mission to break-down “death denialism” (

Becker 1973) by bringing it into public discourse, disseminating information about options for body disposal and commemoration, and facilitating end-of-life planning. Some are extremely popular. One of the movement’s breakout stars is Caitlin Doughty, a Los Angeles-based natural death care advocate, author of the New York Times bestseller

Smoke Gets in Your Eyes (

Doughty 2015), founder of advocacy group

The Order of the Good Death, and YouTube-star. Other doulas specialise in a particular stage of the dying/death/memorialisation process. The variety of names they employ—including “death doulas”, “death midwives”, “death maidens”, “end-of-life consultants”, “natural deathcare assistants” and “green reapers”—is part of their work of self-creation, within and against the modern funeral industry.

The term doula derives from the Ancient Greek

doulē for a female servant or helper, and the labours performed by doulas are particularly gendered. At a

Death Walking Training with Virago of the

Natural Death Care Centre, there were approximately twenty cis women and two trans people undertaking the course—not an uncommon split for these events. From the perspective of palliative care workers, the role of the doula has been likened to that of “the eldest daughter” (

Rawlings et al. 2018), who adopts the (traditionally unpaid) labours of caring for her parents through illness. Doulas further deploy gender to carve out a professional identity by drawing analogy between the take-over of birth by (male) obstetricians and hospitals and the take-over of death by (male) doctors and morticians. Indeed,

Olson (

2018) suggests that it is the very same generation of women who participated in the 1970s home-birth movement that are now leading the home funeral movement. Some in fact present themselves as “full-spectrum doulas”, who usher people through both natal and fatal transitions. As one Australian doula declares: “From opposite ends of the spectrum of life experiences, I travel life events with you!” (

ADC 2020).

While the positionalities and services of doulas are diverse, they coalesce around a return to so-called ‘traditional’ and ‘natural’ approaches to death, which have been lost under the DIC. These approaches are sometimes, but not always, aligned with environmentalism. They emphasise an honest confrontation with, if not an embrace of, natural cycles of life, death, and regeneration. In her public advocacy, Virago asks people to have an honest and pragmatic conversation about the reality of death, including conversations with loved ones about their end-of-life wishes, and even preparing oneself for the death of loved ones by mentally rehearsing the death of, for example, a parent or child. For many, death acceptance also means the rejection of preservationist techniques like embalming. For example,

Doughty (

2011) writes that the modern death system, with its caskets, vaults, and gravestones, offers “a false promise of everlasting preservation that we’ve been terrified into embracing”. She instead invites people to “consider choosing to decompose” by choosing natural burial. This method has, she writes, positive environmental outcomes, but also, Doughty writes, “if we work towards accepting, not denying, our decomposition, we can begin to see it as something beautiful. More than beautiful—ecstatic” (2011).

This honest confrontation with the practical realities of dying extends to how doulas approach the body. Countering popular perceptions of the corpse as scary or dangerous, many doulas carry out what some call ‘body work’: washing, dressing, and tending to the dead body, and encouraging families to do so also. This work is framed as a return to pre-industrial modes of death care and its embodied labours, including keeping the dead in the (funeral) ‘parlour’ of the home, and digging graves by hand. In his study of USA home funeral advocates,

Olson (

2018, p. 204) describes the emphasis that practitioners place on “the personal, intimate skill of practiced hands rather than skill with instruments”. Technologically unimpeded, skin-to-skin contact is held up as a route to a “deeper and more fulfilling form of grief” (ibid.). This practice is not only embraced as intimate and fulfilling, but also often presented as innate. At death walker training, Virago suggested that doulas and bereaved family members were more than capable of caring for dead bodies without specialised training, as generations before them have done (see also

Doughty 2011). Not all technologies are spurned. At home wakes, dry ice, refrigeration plates, and absorbent sheeting are used to preserve the body. Several NDM organisations in Australia loan out cooling beds and cold

Cuddle Cots (for infant use) to communities for this purpose (

End of Life Doula Directory 2017).

Ritual creation around the dying process, the funeral, and grief is seen as a key part of a ‘healthy’ relationship to death. This aspect of the work of doulas shows the impact of spiritual syncretism of the New Age, as practitioners freely blend elements of different spiritual and intellectual traditions, including readings from JRR Tolkien, Buddhist corpse meditation, reiki and crystal healing and essential oils. Candle lighting, as a nondenominational practice, shared across many religious traditions, is a common feature of the funeral services created by doulas and is often presented as an act of “calling in the spirit of the deceased”. One of the more significant influences is Zen Buddhism, as a source of philosophical inspiration, material for eulogies, and instruction in hospice care. Joan Halifax, a renowned Buddhist teacher, palliative care worker, and co-author of the 1977 study The Human Encounter with Death, for example, is actively engaged with the NDM, and her writings frequently appear in at their rituals.

Those involved in body work also look outside their own cultural traditions for inspiration. In Melbourne, one experimental funeral home that offers shrouded cremation and burial as an ecologically friendly option purchases its shrouds from an Islamic funeral service, and its practitioners learned shrouding techniques from a local Baha’i community. Similarly, in Seattle, USA, a group of women led by Sheri Mila Gerson and Leslie Shore are working with the Chevra Kadisha (Jewish Burial Society) to spread the techniques of

taharah to secular and nonreligious death care workers, in which the body is washed, cleansed, and then shrouded. And in Madison, USA, a group of future death doulas are trained in the practice of shrouding (see

Figure 1).

For many doulas, caring for the dying, dead, and bereaved is a spiritual calling; whether it can, or more pointedly

should, become a vocation is another, more troubling question. Many doulas operate as sole-traders or small businesses and charge for their services, often in set ‘packages’. For example, one doula advertises the “Carolynne’s Comfort: End of Life Doula” package, including “a holistic approach to honouring the outgoing journey”, “end of life plan coordination”, “information services, family support, and services co-ordination” (

Doula by Billy 2020). Prices for doula services are often only available upon request. In Australia, they average

$80 per hour for a one-off consultation, but extend to multi-day engagements around the death bed and funerals, for

$800 to

$2000. One doula uses a sliding scale, from free advice and

$20 per hour upwards, depending on the financial circumstances of the family she works with.

Those who do embark upon full-time doula work, however, may find it difficult to make a liveable wage because doulas are not generally well-known by the public and the demand for their services not well-established. Funeral directors serve as powerful mediators between bereaved publics and the industry (

Van Ryn et al. 2019), and the reception of doulas amongst the funeral industry and palliative care workers has been lukewarm at best and antagonistic at worst. Some doulas also reject payment and express discomfort about the commercialization of their practice. One ‘end-of-life doula’, named Maree, who Gould met at the doula training course in Melbourne, 2019, described her skillset as “knowledge that should be held in the community… something that you would once just go to the wise woman in the village for. Payment just makes it so… crass”.

Olson (

2018) describes similar concerns amongst some members of the USA home funeral movement, who worried that men entering the movement would change its ethos and push it toward renumeration. Similar tensions arise around the accreditation of doula services. In Australia, there are now several training courses, including the federally recognized

Cert IV in Doula Support Services run by the Australian Doula College. In the USA, the University of Vermont and the

International End of Life Doula Association (INELDA), among others, offer certification. Maree’s comments caused considerable consternation among other participants at a recent NDM event, some who pointed out that their work was of equal worth to funeral directors and thus should receive equal renumeration. Here, we see shades of capitalism’s tendency to appropriate and commodify its own counter-culture at work (

Fisher 2009, p. 9).

These debates speak more broadly to the tricky position of caring labours (waged and unwaged) for women under capitalism, a situation which will likely intensify as we enter “an era of the care economy” (

Hester 2018, p. 347). While the association of the deeply spiritual calling of the death doula with finance is distasteful for some, the expectation that women should provide these services for free also has the potential to devalue caring labours. Doulas thus appear trapped between the social and economic position of the funeral director and the community-based ‘wise woman’. Funeral directing is a calling for some, but it is also a stable, institutionalised occupation, supported by the broader DIC. On the other hand, the cultural imaginary of the community ‘wise woman’ is occupied by those standing outside the dominant system, who derive power from their alterity and from their knowledge of transitions between life and death, this world and the next (see

Federici 2004, p. 15 on the position of wise women or ‘witches’ in capitalism). For women drawn to becoming a doula, working out where to position oneself in relation to these archetypes is both a matter of principal and financial survival. In the work of death doulas, then, we see how feminine knowledge, skills, and spirituality are reclaimed as more natural ways of approaching death and a rebuke to DIC. However, the commodification of the doula (in ways that run parallel to the funeral director), complicate this practice as a form of gendered resistance to this industrialised model of death care.

4. Two: Becoming Trees

In 2003, Italian designers Raoul Bretzel and Anna Citelli created an innovative new product for the posthumous treatment of bodies. They named it

Capsula Mundi and launched it onto market under the slogan “Life never stops”. The product’s stated goal is twofold: to “reverse the wasteful and harmful trend of traditional burials” (

Collins 2017) and to transform cemeteries from “cold grey landscape[s] … into vibrant woodlands” (

Abend n.d.).

Capsula Mundi is a biodegradable egg-shaped pod, containing a deceased’s remains or whole body in a fetal position. After burial in the ground, the pod and its contents germinate, and from it, according to the designers, a tree will grow. In this way, death transforms into new life. Bretzel and Citelli explain,

In a culture that is far removed from nature, overloaded with objects, and focused on youth, death is often dealt with as a taboo. … It is time for humans to realise our integrated part in nature. … Capsula Mundi wants to emphasise that we are a part of nature’s cycle of transformation.

The designers describe death as a “beginning of a way back to nature”. With its strong message, refined aesthetics, and prolific online marketing campaign, Capsula Mundi has received significant media coverage from around the world. Indeed, several doulas and NDM advocates reported to the authors that every time Capsula Mundi re-surfaces on social media, they receive calls enquiring as to its availability for purchase.

Capsula Mundi is not the only product of this kind. Others, including the Spanish

Bios Urn and

Bios Incube, and the American

Living Urn,

Spíritree, and

EterniTrees, to name but a few, make similar promises to transform the remains of a loved one—person or animal—into arboreal artefacts. All are designed within and marketed to Western audiences, but their practical application is dependent on local legal frameworks regulating body disposal. They also vary in a few other important aspects.

Bios Urns offers high-tech pot plants, instead of trees, which people can keep in their homes. The system is linked to a specialised app, which helps monitor the soil, light exposure, and atmospheric temperature (

Boyd 2019). In this manner, the system not only extends the (after)life of the dead through the plant, but also ensures that the plant itself does not meet an untimely end.

Spíritree places ash above ground in a bowl, instead of interring the remains in the earth.

EterniTrees offers the option of planting multiple trees from one person’s cremated remains, as for each tree only a small cup of ashes is needed.

Living Urn works with already living trees instead of seeds or seedlings because the developers suggest that this is the only viable way for trees to grow in concert with ash. The developers also produce an ash-neutralizing agent, which they claim counteracts the harmful chemical properties of cremated remains (

Amelinckx 2016).

These arboreal necro-technologies sit within the strand of the NDM focused on promoting more sustainable methods for handling bodies. Specifically, these high-tech solutions continue on from a broader legacy of activism toward natural burial, also referred to as ecological, green, or woodland burial (

Clayden and Dixon 2007;

Davies and Rumble 2012). The exact definition of ‘natural’ between different actors in these communities is contested, but broadly describes a desire to become independent “from the ‘unnatural’ interference of commercial ventures” and to enter into “an alliance with the organic world” (

Davies and Rumble 2012, p. 1). This alliance is aptly emphasized in the two main symbols used for the

Capsula Mundi design: an egg and a tree, respectively emphasizing fertility and reproduction, and organic growth. The symbolism of the tree is particularly prominent in this domain. Throughout history and around the world, trees have played, and continue to play, a crucial role in religion and spirituality (

Clayden and Dixon 2007;

Crews 2003;

Macnaghten and Urry 2000;

Urban 2015). They loom particularly large in contemporary Wicca and neopagan religions as transdimensional objects, which connect heaven to earth and the underworld, as well as representing longevity, the beginning of life and fertility (

Lewis 1999).

In the arboreal necro-technologies, trees are represented as linking death to nature and life in three inter-related ways. First, trees symbolise the ongoing legacy of an individual and of their kinship group. The personification of certain species of trees can be used to symbolize a single person, such as a strong oak tree representing the watchful eye of a grandfather over a family (

Russell 1981). A more prominent use, however, is the iconography of tree as intergenerational family line (

Chevalier and Gheerbrant 1982;

Crews 2003). A USA-born woman named Elizabeth has incorporated her mother’s ashes into soil to grow a pot plant which she keeps at home. She shares: “Every day I go out to check on mum. I’m not going to let

it die” (

Boyd 2019, emphasis by author). By continuing to care for the pot plant, Elizabeth tends to the ongoing presence of her deceased mother in her life. As the plant grows, family and friends visit the plant, thereby upkeeping kinship relations between the living and the dead. In this way, the arboreal products come to stand not only “as a memorial for the departed”, but “as a legacy for posterity and the future of our planet” (

Zareva 2011). Pictures on the homepage of

Living Urn demonstrate this symbolism: they show a beautiful tree in autumn colours, a child lovingly touching the tree’s leaves, and a mother and child joined beside the tree. The images are coupled with the words: “Honour your loved ones, give back, grow a living memory” (

The Living Urn 2020).

Second, trees serve as symbolic shorthand for offsetting one’s carbon footprint.

Spíritree advertises their invention as “the only product in the market that connects the funeral tradition of commemoration with land preservation”, by “[arresting] CO2 indefinitely, thus having a truly negative carbon footprint” (

Spíritree 2015). Both life and death in the Anthropocene are extractive, consuming land and resources and generating carbon dioxide. Posthumously becoming a tree appears to solve both problems: it limits space devoted to the disposal of human bodies by transforming it into forested land, and it offsets (at least some of) the CO2 that was produced during a person’s lifetime. In this way, it adds to “planetary restoration” (

Bios Urn 2021). By offering the possibility to become a tree (as opposed to slowly-decaying coffin remains), the arboreal necro-technologies extend the moral responsibility of humans for nature beyond the end of an individual’s lifespan. As the designers of

Capsula Mundi put it: “Just because you’re dead doesn’t mean you should stop caring about the Earth” (

Amelinckx 2016).

Lastly, trees embody, quite literally, the afterlife of a loved one. In the Marie Curie magazine (

Marie Curie 2019), a UK-based care and support organization for patients with terminal illness, one can read the story of Clare, an Irish hospice worker, who would like to become a tree after she dies. She explains: “… the idea of what used to be me growing into a tree sounds like a good way to live on.... I like to imagine that one day someone will sit under my tree and read a good book or just enjoy the day.” Becoming a tree offers the possibility to return to the natural cycle of life and to become part of that cycle. The material affordances of trees make them a fertile material for this kind of symbolic work (

Crews 2003). Trees are alive like humans and animals, but unmovable; they are immobile like mountains, but also change and sway. They wax and wane with the seasons, and they provide shelter, food, shade, and materials. Additionally, the shape of trees calls the human body into imagination, with the branches as arms and fingers, the trunk as body, and the bark as skin. The ritual interconnection of death and rebirth in this manner is well-attested across cultures and through time. In their classic work

Death and the Regeneration of Life, Maurice Bloch and Jonathan Parry (

Bloch and Parry 1982, p. 9) describe how “almost everywhere religious thought consistently denies the irreversible and terminal nature of death by proclaiming it a new beginning”. What marks the arboreal necro-technologies as distinct innovation, however, is how they articulate this regeneration via the natural landscape, rather than in an other-worldly plane of existence. They thus promote so-called “ecological immortality” (

Davies 2005, p. 86; also

Brigham 2002) instead of immortality in heaven.

While it might be clear how these products fit into the NDM, the role of gender is less obvious. The producers and consumers of the tree products are equally male and female. There is contrasting research done by

Clayden and Dixon (

2007, p. 252), who found a more gendered pattern in tree choice at British natural burial sites, with men most prominently choosing oak and women silver birch; the types of trees chosen also do not seem to be gendered but rather dependent on other values such as the native nature of the tree in a particular context. Implicitly, however, gender is indeed significant. Again, this is most prominently displayed by the use of the tree as symbol for life and death, and as imaginary of a feminine embodiment of the natural world. For example, the symbolic work of trees (enduring legacy, offsetting CO2, and arboreal embodiment) is visually illustrated on the website of

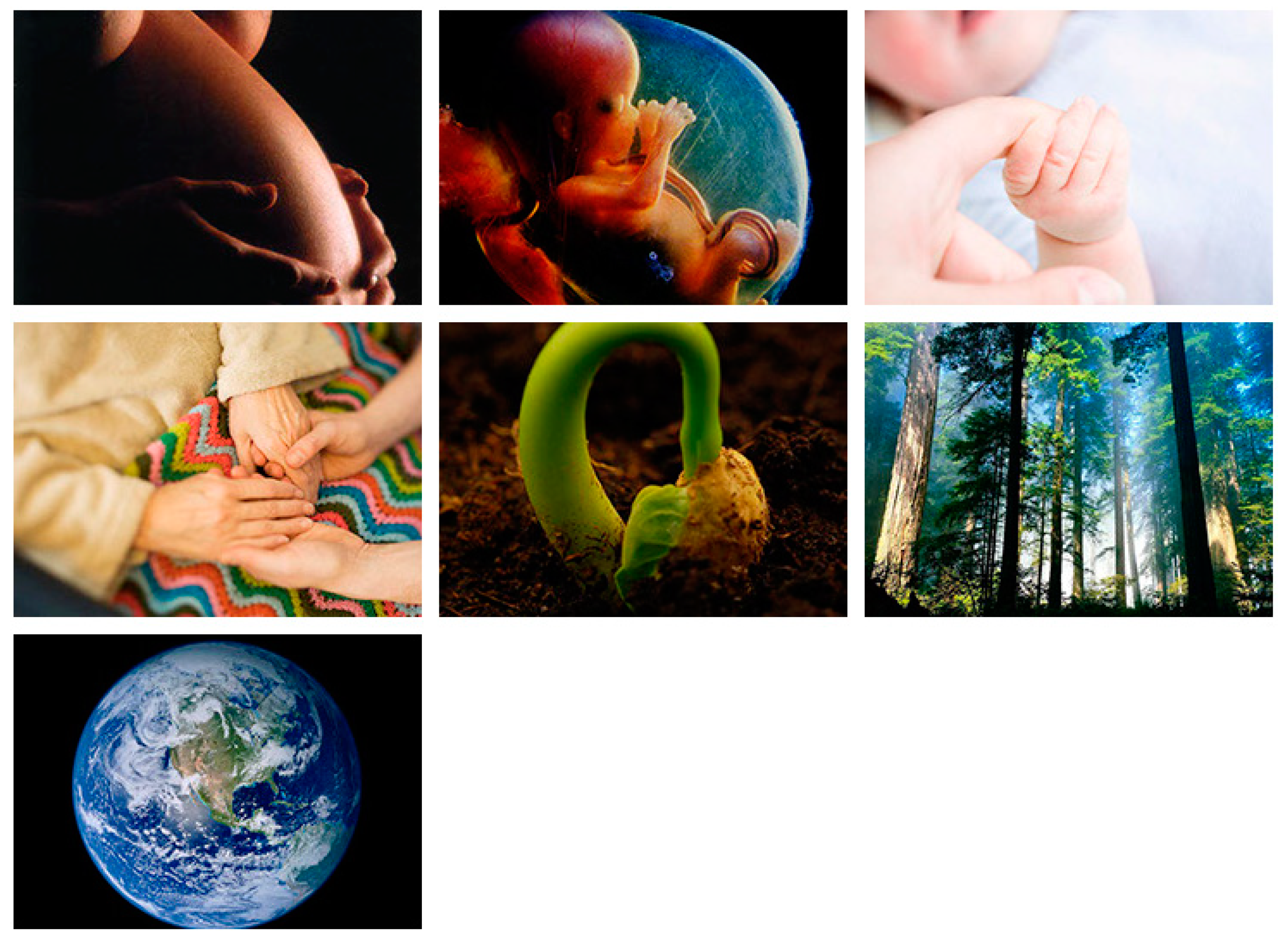

Spíritree, where a sequence of seven pictures connects the feminine reproductive ability to create and nourish life to our human ability to take care for nature and, eventually, the planet (see

Figure 2). This symbolism is highly gendered. As noted,

Capsula Mundi is designed to mimic an ovum or egg that sits beneath and supports the life of a tree. Less explicitly, the marketing of the many products emphasises feminine-coded qualities, including care for the family beyond death, the value of touch-based relationships to death, and an appeal to fertility, imagination and creativity. Here, the fatal becomes inextricably connected to the natal in a never-ending cycle, leading to planetary restoration.

This relation calls into question the presumed dualism between mind and body, and between the human and nonhuman, which casts trees as inanimate objects (

Haberman 2013) and severs them from kinship with humans. This nature/human division has already been shown to be contracted by ethnographic accounts of lived experiences (see for example

Descola and Pálsson 1996;

Kohn 2013). Arboreal necro-technologies forge intrinsic bonds between humans and nature, in life and death. This opens a new understanding of a tree as “a sentient being with whom one can develop a mutual beneficial relationship” (

Haberman 2013, p. 189). The result of this new understanding is a collaborative connection between humans and the natural system, in which humans become part of nature and its cycle, and vice versa (

Davies 2005).

In this manner, both the caring labours of doulas and the symbolism of new arboreal necro-technologies tie together women and nature to build an alternative model of a good death. However, just as doulas struggle to stand outside of the DIC while at the same time monetising their labours, vendors for tree-based necro-technologies operate on business models, all the while making public commitments to less profit-driven solutions for death care. The products discussed here invoke a pre-modern mode of death in which remains go straight into the ground and provide sustenance for other living creatures, but propose to deliver this ecological unity in very modern, highly technified, 21st century solutions. Product designers do not deny the contradictions of this approach. Moliné, the inventor of

Bios Urn and the associated app, mentioned in an interview: “We decided it was okay to bring the process of death and dying up to speed with 21st-century demands and request” (

Amelinckx 2016), and the designers of

Capsula Mundi believe “death is as closely related to consumerism as life” (

Erizanu 2018).

5. Discussion

The contemporary death care system (DIC) is an industrial venture on a dramatic scale, one designed to pass bodies between the hospital, morgue, and cemetery or crematorium

en masse. For many of those encountering this system, death is fundamentally flawed: damaging to the environment, economically exploitative, bereft of personal feeling, and harmful to the grieving process. The NDM represents a contemporary attempt to resolve this harm, by offerings services that promote a more holistic, spiritual, and personalised approach to death, and by re-establishing connections between humans and nature. The contrasts between DIC and NDM are nicely summarised by Australian ecofeminist Val

Plumwood (

2008, pp. 70–71). She describes the modern funeral industry as a symptom of “the western war of life against death” that entails “the loss of humbling but important forms of knowledge, of ourselves and of our world”. What we need to realize, she argues, is that we are all connected in webs of relations, between ourselves and the material and immaterial world around us, and between ourselves and those who have died. In this way, she argues, “we are, if we can permit ourselves to see and feel and understand it, always already other-than-human” (

Barnett 2018, p. 26). Gender is of crucial importance here. In response to the ‘masculine’ industry that has emerged in the past centuries, NDM adherents, such as Plumwood propose a re-feminizing of death care. Here, gender is both the genesis of and the solution to the detriments above.

In the above sections, we described two empirical examples of NDM services and products. In both cases, the distance between the human and nature is reduced through physical contact and embodied practices. Emphasis is placed on typically romanticized pre-industrial and often pre-Christian deathways, presenting death as a natural instead of cultural process. Professionals within the NDM position themselves and death in a way that resists current industrialized, modern, capitalist death practices. In this, gender is implicitly or explicitly highlighted. Death doulas present themselves as natural carers for the dying, the deceased, and their families, promoting “soft” qualities such as (spiritual) creativity, ritualization, care, and empathy. Producers of arboreal necro-technologies likewise draw on this symbolic field to market their innovations, with images of eggs, trees, and nature, highlighting feminine qualities such as fertility and nourishment.

In the illustrations, however, a particular tension arises. Although mounting a passionate critique of DIC, both green necro-technologists and doulas appear to largely work within, and in some cases even reinforce, the structures and operations of the contemporary funeral industry, including its gendered structures. The NDM empowers women by offering them new roles and figures of reference, but at the same time reproduces the gender stereotypes already in place. It seems that transcending the gendered archetypes set up by the DIC, even by way of distinction, appears an intensely challenging undertaking. This raises the questions to what extent the NDM, and its associated products and services, succeeds in challenging the gendered power structures of DIC, and what it brings to a new way of ‘doing death’.

In addition, as illustrated above, both doulas and arboreal necro-technology innovators struggle to work outside of, and hence transform, the DIC, and instead often find themselves existing on its fringes. Their use of social media is a case in point. The NDM is often savvy in its use of social media, with almost daily comments and communications via websites, blogs, and a multitude of online platforms. Hence, while the NDM positions itself against the modern death industry, it simultaneously makes effective use of its features, such as digitalization and marketing. Moreover, capitalism’s grip over death is difficult to escape, ever for those advocating change. Despite their anti-establishmentarian feelings, death doulas are forced to operate within and parallel to the “masculine” death industry in order to make a living wage. Death doulas are certainly not cheap, and while an arboreal necro-product is on average cheaper than a headstone, the prices are still mostly affordable for those with a higher income. The idealised “return” to a time when human life and death were in sync with nature is promoted and idealised, but done from within capitalist frameworks, techniques, and strategies. As Brenda Mathijssen and Claudia Venhorst (

Mathijssen and Venhorst 2019, pp. 51–52) indicate, this makes sense because the work of funeral directors nowadays requires often contradictory qualities: “One has to be both empathetic and business-like, independent and a team player, organised and creative. … It is difficult to reconcile a commercial, business-like attitude with an excess of empathy and care.”

The same tension arises when analysing the ecological aspects of death, dying and disposal. Although seeking to curb the ecological excesses of industrialized death care, the NDM does not relinquish its control over death or its sequestration from everyday life. For example, as Tony

Walter (

2020, p. 96) put it: “The only fully natural way for a large mammal such as a human to be disposed of is for it to lie on the ground and there be eaten by predators, bugs and worms.” Very few NDM adherents even approach this discourse, instead emphasizing the sanctity of human life, even when it is in concert with that of nonhuman life. Trees are the ultimate symbol of the natural as opposed to the industrial. However, in the carefully designed and marketed, app-controlled arboreal necro-technologies, this nature is human-designed and human-made, albeit in a less male-centred and ecologically friendly manner. The ‘nature of death’ has become artificial and man-made—exactly the characteristics that Anthropocene critics argue against.

It thus appears that the NDM is primarily a new cultural death approach, focusing on bringing us closer to nature, but in effect being primarily effective in its symbolism, representing death and death care as post-material, post-industrial, ecological, and feminine. In this way, NDM is successful in transforming the current funeral system, as it revaluates the intrinsic relations between body, death and nature. By emphasising female creative power, it informs, slowly but surely, our understanding of our own mortality. This is primarily done by offering new spiritual frameworks around death and death rituals. Similar to other New Age movements, NDM sees itself as “

the key to moving from all that is wrong with the world to all that is right” (

Heelas 1996, p. 16, original emphasis). To do this, NDM offers a new ritual framework for dying, death and disposal, one that draws on a lost connection to “traditional” religions as well as nature. This ritualization seems necessary, as it helps us to return to thinking and talking about death, to embracing and embodying death, and to “doing death” in a positive way. Interestingly, this ritualization does not solely concern itself with a person’s journey to an

afterlife such as a Heaven, but to the “after-death”: that what happens to nature after an individual has died, and to relatives grieving loss. In other words, theological immortality has shifted to natural immortality: the focus of attention has shifted “from the past to the present and from any eternal future in heaven to a long-term future for humanity on earth” (

Davies 2005, p. 77).

NDM thus seems to primarily offer a newfound spirituality that has emerged in response to a loss of established religions. Although both death studies scholars and NDM activists have framed this decline as a loss, it evidently also breeds new life. Prominent feminist and self-proclaimed witch Starhawk, who developed an earth-based spirituality intended to bring about environmental sustainability and social justice, argued how “patriarchal religions [red.: Judaism and Christianity] reinforce the domination of humans over nature just as they reinforce the domination of male over female, which has resulted in a long history of exploitation of both women and the environment” (

Urban 2015, p. 172). With the declining influence of these religions, other spiritualities, such as more neopagan worldviews, have gained ground, which see the natural world as filled with divine energy, mostly feminine. In line with this, new death attitudes have emerged which emphasize a ritualized and femininized return of humans to nature and death to life. In our Anthropocenic age, this re-feminization of death might just offer one solution to environmental damage brought about by humans—both alive and dead.