Spirituality and Health in Brazil: A Survey Snapshot of Research Groups

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodological Procedures

as a group of individuals that are hierarchically organized around one or, eventually, two leaders; with the organizing foundation of this hierarchy being: experience, prominence and leadership in the scientific or technological field; professional and permanent involvement in the research activity; work organized around common lines of research that are subordinate to the group (and not the other way around); and, to some degree, shared facilities and equipment. The concept of group may be that composed of only one researcher and his or her students.

- Institutionally certified group: certified and updated group that participates in the directory census.

- Not updated group: certified group with no updates for more than 12 (twelve) months. The leader has 12 (twelve) months to update a group in this situation. After this period, the group’s status will automatically change to “excluded” and can no longer be recovered in the database by the leader or the person representing the institution in which the research group is housed. The Research Officer can certify or withdraw certification from a not updated group, changing its status to “Certification Denied”. A not updated group does not participate in the directory’s censuses but is available for examination in the public search of the DRG portal (in Search Groups, Current Base) for a maximum period of 12 months. If there are no updates during this period, that group is excluded from the database.

- Predominant area of the group: area of knowledge that most closely matches the group’s research activities, among those existing in the classification of areas of knowledge used by CNPq. Even multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary groups must be related to an area that coordinates their activities. The research lines of a research group can be associated with up to three areas of knowledge and subareas or specialties.

- Research Lines: represent unified themes of scientific studies based on an investigative tradition, developing projects whose results are related to each other. Because research lines are subordinate to groups, groups can have one or more lines, and they do not necessarily need to be associated with all members of the group.

3. Results

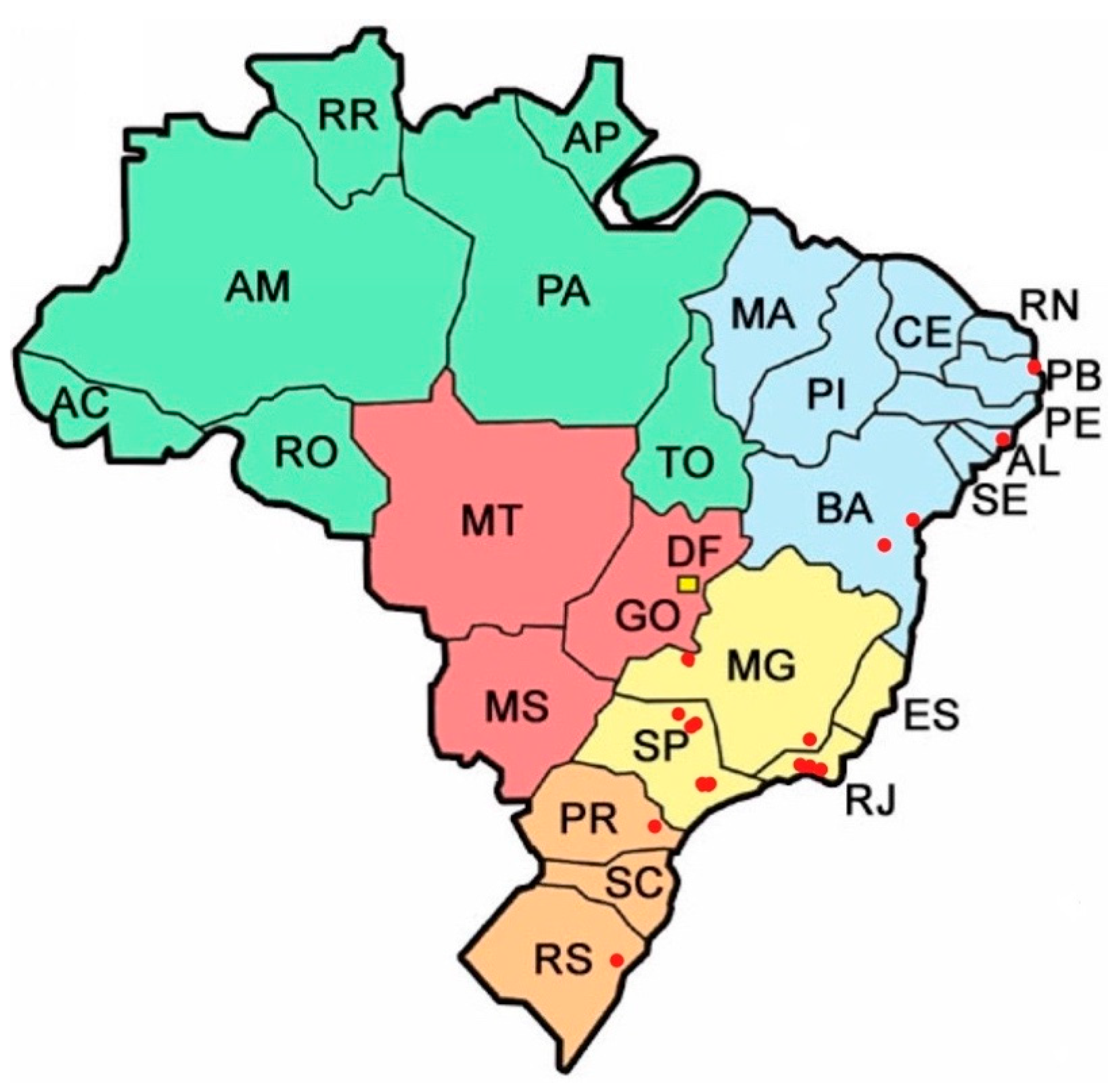

3.1. Geographical Location of Research Groups in Brazil

3.2. Categorization and Evolution of Groups and Lines of Research

3.3. Main Topics Investigated in the Groups and Lines of Research

- (a)

- Quality of life in several contexts and populations: in situations of illness (Carvalho et al. 2019), older people (Santos and Abdala 2014; Veras et al. 2019; Reis et al. 2016); people with HIV/AIDS (Gomes et al. 2020), and mental health (Lucchetti et al. 2018; Mainieri et al. 2017; Nwora and Freitas 2020).

- (b)

- The lack of S&H training for students and health professionals (Cavalheiro and Falcke 2014; Costa et al. 2019; Lucchetti and Granero 2010; Aguiar et al. 2017).

- (c)

- Integration of spirituality into healthcare (Esperandio 2014; Moreira-Almeida et al. 2006; Sens et al. 2019; Cunha and Comin 2019; Oliveira et al. 2018).

- (d)

- Relationship between spirituality/religiosity and health in the general population (Lucchetti et al. 2013; Cavalcanti et al. 2012; Moreira-Almeida et al. 2010).

- (e)

- Prayer and health (Esperandio and Ladd 2015); prayer and cancer patients (Paiva et al. 2015; Paiva et al. 2014).

- (f)

- (g)

- Meaning-making (Rocha et al. 2018a; Silva et al. 2020).

- (h)

- Creation and validation of instruments for assessing spirituality (Abdala et al. 2020; Esperandio et al. 2018; Oliveira da Silva et al. 2020a, 2020b; Curcio et al. 2015; Silva et al. 2018).

4. Discussion

4.1. Research Center on Spirituality and Health (NUPES)—Federal University of Juiz de Fora (UFJF)

4.2. Challenges and Potentialities of Research Groups in the Field of S&H: Some Considerations

4.2.1. A Starting Point that Should Be Considered by Beginners or “In-Process” Research Groups

4.2.2. Searching for a Consistent Conceptualization of “Spirituality” and “Religiosity”

4.2.3. Implications of the Conceptual Differentiation of Spirituality and Religiosity

4.2.4. A Promising Research Topic: The Relationship between Religious Cognition, Religious Behavior, and Health Outcomes

4.2.5. Models of Spiritual Care

4.2.6. Specificities of Spiritual Assistance and Spiritual Care Education

4.2.7. The Need for a Critical Perspective on the Field

4.2.8. Training of Professional Spiritual Caregivers to Work in Multidisciplinary Healthcare Teams

4.2.9. Political Implications Concerning Spirituality as a Public Health Issue

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdala, Gina Andrade, Maria Dyrce Dias Meira, Gabriel Tagliari Rodrigo, Morenilza Bezerra da Conceição Fróes, Matheus Souza Ferreira, Sammila Andrade Abdala, and Harold George Koenig. 2020. Religion, Age, Education, Lifestyle, and Health: Structural Equation Modeling. Journal of Religion and Health 2020: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, Paulo Rogerio, Silvio César Cazella, and Marcia Rosa Costa. 2017. A Religiosidade/Espiritualidade Dos Médicos de Família: Avaliação de Alunos Da Universidade Aberta Do SUS (UNA-SUS). Revista Brasileira de Educação Médica 41: 310–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- August, Hartmut, and Mary Esperandio. 2019. Attachment to god: Integrative review of empirical literature apego a deus: Revisão integrativa de literatura empírica. HORIZONTE—Revista de Estudos de Teologia e Ciências da Religião 17: 1039–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- August, Hartmut, and Mary Rute Gomes Esperandio. 2020. Teoria do apego e apego a deus no aconselhamento: Estudo de caso. Estudos Teológicos 60: 298–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandeira, Olívia, and Brenda Carranza. 2020. Reactions to the Pandemic in Latin America and Brazil: Are Religions Essential Services? International Journal of Latin American Religions 4: 170–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, Guilherme D., Fernanda P. Costa, João Alberto M. Peruchi, Geris Mazzutti, Igor G. Benedetto, Josiane F. John, Lia A. Zorzi, Marcius C. Prestes, Marina V. Viana, Moreno C. Santos, and et al. 2019. The Quality of End-of-Life Care after Limitations of Medical Treatment as Defined by a Rapid Response Team: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Journal of Palliative Medicine 22: 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcanti, Ana Paula Rodrigues, Carlos André Macêdo Cavalcanti, Carla Fernanda Ferreira-Rodrigues, Charlene Nayana Nunes Alves Gouveia, Deborah Dornellas Ramos, and Fagner José de Oliveira Serrano. 2012. Hipertensos de Baixa Renda e Recurso à Religiosidade como Estratégia de Controle. Diversidade Religiosa 2: 1–11. Available online: https://periodicos.ufpb.br/ojs2/index.php/dr/article/view/11857 (accessed on 14 October 2018).

- Cavalheiro, Carla Maria Frezza, and Denise Falcke. 2014. Espiritualidade Na Formação Acadêmica Em Psicologia No Rio Grande Do Sul. Estudos de Psicologia (Campinas) 31: 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq). 2020a. Manual do usuário: DGP—Diretório de Grupo de Pesquisa. O Diretório. Available online: http://lattes.cnpq.br/web/dgp/manual-do-usuario. www.rish.ch/pdf/Newsletter2006-2.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2018).

- Costa, Milena Silva, Raphael Tavares Dantas, Cecília Gomes dos Santos Alves, Eugênia Rodrigues Ferreira, and Arthur Fernandes da Silva. 2019. Espiritualidade e Religiosidade: Saberes de Estudantes de Medicina. Revista Bioética 27: 350–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, Waldecíria, Conceição Nogueira, and Teresa Freire. 2010. The Lack of Teaching/Study of Religiosity/Spirituality in Psychology Degree Courses in Brazil: The Need for Reflection. Journal of Religion and Health 49: 322–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, Vivian F., and Fabio S. Comin. 2019. ReligiositySpirituality (RS) in the Clinical Context: Professional Experiences of Psychotherapists. Temas Em Psicologia 27: 427–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curcio, Cristiane Schumann Silva, Giancarlo Lucchetti, and Alexander Moreira-Almeida. 2015. Validation of the Portuguese Version of the Brief Multidimensional Measure of Religiousness/Spirituality (BMMRS-P) in Clinical and Non-Clinical Samples. Journal of Religion and Health 54: 435–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esperandio, Mary. 2014. Teologia e a Pesquisa Sobre Espiritualidade e Saúde: Um Estudo Piloto Entre Profissionais da Saúde e Pastoralistas. HORIZONTE 12: 805–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esperandio, Mary, and Carlo Leget. 2020. Spirituality in palliative care in Brazil: An integrative literature review. REVER—Revista de Estudos da Religião 20: 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esperandio, Mary, and Kevin Ladd. 2015. I Heard the Voice. I Felt the Presence’: Prayer, Health and Implications for Clinical Practice. Religions 6: 670–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esperandio, Mary Rute Gomes, and Geilson Antonio Silva Machado. 2018. Brazilian Physicians’ Beliefs and Attitudes Toward Patients’ Spirituality: Implications for Clinical Practice. Journal of Religion and Health 58: 1172–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esperandio, Mary Rute Gomes, and Luciana Fernandes Marques. 2015. The psychology of religion in Brazil. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 25: 255–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esperandio, Mary Rute Gomes, and Tiago Silva Rosa. 2020. Avaliação da espiritualidade/religiosidade de pacientes em cuidados paliativos. Protestantismo em Revista 46: 168–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esperandio, Mary, Fabiana Escudero, Marcio Fernandes, and Kenneth Pargament. 2018. Brazilian Validation of the Brief Scale for Spiritual/Religious Coping—SRCOPE-14. Religions 9: 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esperandio, Mary Rute Gomes, Hartmut August, Juan José Camou Viacava, Stefan Huber, and Marcio Luiz Fernandes. 2019. Brazilian validation of Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS-10BR and CRS-5BR). Religions 10: 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinha, Daniele Corcioli Mendes, Stéphanie Marques de Camargo, Sabrina Piccinelli Zanchettin Silva, Shirlene Pavelqueires, and Giancarlo Lucchetti. 2013. Opinião Dos Estudantes de Enfermagem Sobre Saúde, Espiritualidade e Religiosidade. Revista Gaúcha de Enfermagem 34: 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, Antonio Marcos Tosoli, Sergio Corrêa Marques, Virginia Paiva Figueiredo Nogueira, Julio Cesar Cruz Collares-da-Rocha, Gerson Lourenço Pereira, Themistoklis Apostolidis, Luiz Carlos Moraes França, Karen Paula Damasceno dos Santos Souza, Magno Conceição das Merces, Pablo Luiz Santos Couto, and et al. 2020. A religiosidade para pessoas vivendo com HIV/Aids: Um estudo de representações sociais. Enfermagem Brasil 18: 750–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, Stefan, and Odilo W. Huber. 2012. The Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS). Religions 3: 710–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). 2010. Censo Demográfico 2010: Características gerais da população, religião e pessoas com deficiência. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE, pp. 1–215. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig, Harold G. 2012. Religion, Spirituality, and Health: The Research and Clinical Implications. ISRN Psychiatry 2012: 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucchese, Fernando A., and Harold G. Koenig. 2013. Religion, Spirituality and Cardiovascular Disease: Research, Clinical Implications, and Opportunities in Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Cardiovascular Surgery 28: 103–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucchetti, Giancarlo, and Alessandra Granero. 2010. Integration of Spirituality Courses in Brazilian Medical Schools. Medical Education 44: 527–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchetti, Giancarlo, Alessandra Lamas Granero Lucchetti, Daniele Corcioli Mendes Espinha, Leandro Romani de Oliveira, José Roberto Leite, and Harold G. Koenig. 2012. Spirituality and Health in the Curricula of Medical Schools in Brazil. BMC Medical Education 12: 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchetti, Giancarlo, Harold G. Koenig, José Roberto Leite, and Alessandra L. G. Lucchetti. 2013. Medical students, spirituality and religiosity-results from the multicenter study SBRAME. BMC Medical Education 13: 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchetti, Alessandra, Ricardo Barcelos-Ferreira, Dan G. Blazer, and Alexander Moreira-Almeida. 2018. Spirituality in Geriatric Psychiatry. Current Opinion in Psychiatry 31: 373–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainieri, Alessandra Ghinato, Julio Fernando Prieto Peres, Alexander Moreira-Almeida, Klaus Mathiak, Ute Habel, and Nils Kohn. 2017. Neural Correlates of Psychotic-like Experiences during Spiritual-Trance State. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging 266: 101–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, Ticiane Dionizio de Sousa, Silmara Meneguin, Maria de Lourdes da Silva Ferreira, and Helio Amante Miot. 2017. Quality of Life and Religious-Spiritual Coping in Palliative Cancer Care Patients. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mena-Chalco, Jesús Pascual, and Roberto Marcondes Cesar Junior. 2009. ScriptLattes: An Open-Source Knowledge Extraction System from the Lattes Platform. Journal of the Brazilian Computer Society 15: 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, Angelo Braga, Eliane Ramos Pereira, Bruna Maiara Ferreira Barreto, and Rose Mary Costa Rosa Andrade Silva. 2018. Counseling and spiritual assistance to chemotherapy patients: A reflection in the light of Jean Watson’s Theory. Escola Anna Nery 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menegatti-Chequini, Maria C., Everton de O. Maraldi, Mario F. P. Peres, Frederico C. Leão, and Homero Vallada. 2019. How Psychiatrists Think about Religious and Spiritual Beliefs in Clinical Practice: Findings from a University Hospital in São Paulo, Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry 41: 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministério da Educação. 2020a. Apresentação—Portal CNPq. Available online: http://www.cnpq.br/web/guest/apresentacao_institucional/ (accessed on 22 November 2018).

- Brazil, Ministério da Educação. 2020b. Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel. Available online: https://www.iie.org:443/Programs/CAPES (accessed on 22 November 2018).

- Moreira-Almeida, Alexander, and Giancarlo Lucchetti. 2016. Panorama das pesquisas em ciência, saúde e espiritualidade. Ciência e Cultura 68: 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira-Almeida, Alexander, Francisco Lotufo Neto, and Harold G Koenig. 2006. Religiousness and Mental Health: A Review. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria 28: 242–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira-Almeida, Alexander, Ilana Pinsky, Marcos Zaleski, and Ronaldo Laranjeira. 2010. Envolvimento Religioso e Fatores Sociodemográficos: Resultados de Um Levantamento Nacional No Brasil. Archives of Clinical Psychiatry (São Paulo) 37: 12–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NUPES—Núcleo de Pesquisa Em Espiritualidade e Saúde. n.d. Available online: https://www.ufjf.br/nupes/pesquisadores/ (accessed on 15 October 2020).

- Nwora, Emmanuel Ifeka, and Marta Helena de Freitas. 2020. Relações entre religiosidade e saúde mental na concepção de capelães. REVER—Revista de Estudos da Religião 20: 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, Raquel Aparecida de. 2017. Saúde e Espiritualidade Na Formação Profissional Em Saúde, Um Diálogo Necessário. Revista Da Faculdade de Ciências Médicas de Sorocaba 19: 54–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Oliveira, Joana. 2020. Cristião Rosas, médico: O aborto legal é um direito. A influência religiosa faz mal à saúde e põe vidas em risco. EL PAÍS. August 30. Available online: https://brasil.elpais.com/brasil/2020-08-30/cristiao-rosas-medico-o-aborto-legal-e-um-direito-a-influencia-religiosa-faz-mal-a-saude-e-poe-a-vida-em-risco.html (accessed on 15 October 2020).

- Oliveira da Silva, Cassiano Augusto, Ana Paula Rodrigues Cavalcanti, Kaline da Silva Lima, Carlos André Macêdo Cavalcanti, Tânia Cristina de Oliveira Valente, and Arndt Büssing. 2020a. Item Response Theory Applied to the Spiritual Needs Questionnaire (SpNQ) in Portuguese. Religions 11: 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira da Silva, Cassiano Augusto, Ana Paula Rodrigues Cavalcanti, Kaline da Silva Lima, Carlos André Macêdo Cavalcanti, Tânia Cristina de Oliveira Valente, and Arndt Büssing. 2020b. Spiritual Needs Questionnaire (SpNQ): Validity Evidence among HIV+ Patients in Northeast Brazil. Religions 11: 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, Rafael Moura, Rose Manuela Marta Santos, and Sérgio Donha Yarid. 2018. Espiritualidade/religiosidade e o humanizaSUS em Unidades de Saúde da Família. Revista Brasileira em Promoção da Saúde 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oman, Doug. 2013. Defining religion and spirituality. In Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 2nd ed. Edited by Raymond F. Paloutzian and Crystal L. Park. New York and London: The Guilford Press, pp. 24–47. [Google Scholar]

- Oman, Doug. 2018. What’s next?: Public health and spirituality. In Why Religion and Spirituality Matter for Public Health. Edited by Doug Oman. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 463–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiva, Carlos Eduardo, Bianca Sakamoto Ribeiro Paiva, Sriram Yennurajalingam, and David Hui. 2014. The Impact of Religiosity and Individual Prayer Activities on Advanced Cancer Patients’ Health: Is There Any Difference in Function of Whether or Not Receiving Palliative Anti-Neoplastic Therapy? Journal of Religion and Health 53: 1717–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paiva, Bianca Sakamoto Ribeiro, André Lopes Carvalho, Giancarlo Lucchetti, Eliane Marçon Barroso, and Carlos Eduardo Paiva. 2015. ’Oh, Yeah, I’m Getting Closer to God’: Spirituality and Religiousness of Family Caregivers of Cancer Patients Undergoing Palliative Care. Supportive Care in Cancer 23: 2383–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Crystal L. 2014. Meaning, Spirituality, and Health: A Brief Introduction. Revista Pistis Praxis 6: 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, Karine Costa Lima, and Adriano Furtado Holanda. 2019. Religião e Espiritualidade No Curso de Psicologia: Revisão Sistemática de Estudos Empíricos. Interação Em Psicologia 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peteet, John R., and Michael J. Balboni. 2013. Spirituality and religion in oncology: Spirituality and religion in oncology. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 63: 280–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, Camila Calhau Andrade, Edite Lago da Silva Sena, and Tânia Maria de Oliva Menezes. 2016. Experiences of Family Caregivers of Hospitalized Elderlies and the Experience of Intercorporeality. Escola Anna Nery—Revista de Enfermagem 20: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, Renata Carla Nencetti Pereira, Eliane Ramos Pereira, and Rose Mary Costa Rosa Andrade Silva. 2018a. The spiritual dimension and the meaning of life in nursing care: Phenomenological approach. REME: Revista Mineira de Enfermagem 22: e-1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, Renata Carla Nencetti Pereira, Eliane Ramos Pereira, Rose Mary Costa Rosa Andrade Silva, Angelica Yolanda Bueno Bejarano Vale de Medeiros, and Aline Miranda da Fonseca Marins. 2020. O sentido da vida dos enfermeiros no trabalho em cuidados paliativos: Revisão integrativa de literatura. Revista Eletrônica de Enfermagem 22: 56169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, Renata Carla Nencetti Pereira, Eliane Ramos Pereira, Rose Mary Costa Rosa Andrade Silva, Angelica Yolanda Bueno Bejarano Vale de Medeiros, Sueli Maria Refrande, and Neusa Aparecida Refrande. 2018b. Spiritual needs experienced by the patient’s family caregiver under oncology palliative care. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem 7: 2635–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, Neyde Cintra dos, and Gina Andrade Abdala. 2014. Religiosidade e qualidade de vida relacionada à saúde dos idosos em um município na Bahia, Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Geriatria e Gerontologia 17: 795–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sens, Guilherme Ramos, Gina Andrade Abdala, Maria Dyrce Dias Meira, Silvana Bueno, and Harold G. Koenig. 2019. Religiosity and Physician Lifestyle from a Family Health Strategy. Journal of Religion and Health 58: 628–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, Alexander Cangussu, Oscarina da Silva Ezequiel, Rodolfo Furlan Damiano, Alessandra Lamas Granero Lucchetti, Lisabeth Fisher DiLalla, J. Kevin Dorsey, and Giancarlo Lucchetti. 2018. Translation, Transcultural Adaptation, and Validation of the Empathy, Spirituality, and Wellness in Medicine Scale to the Brazilian Portuguese Language. Teaching and Learning in Medicine 30: 404–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, Annaterra Araújo, Antonio Marcos Tosoli Gomes, Ana Cristina Santos Duarte, and Sergio Donha Yarid. 2020. Influência do coping religioso-espiritual no luto materno. Enfermagem Brasil 19: 310–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, Gabriela Cruz Noronha, Dáfili Cristina dos Reis, Talita Prado Simão Miranda, Ruan Nilton Rodrigues Melo, Mariana Aparecida Pereira Coutinho, Gabriela dos Santos Paschoal, and Érika de Cássia Lopes Chaves. 2019. Religious/Spiritual Coping and Spiritual Distress in People with Cancer. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem 72: 1534–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veras, Sylvia Maria Cardoso Bastos, Tânia Maria de Oliva Menezes, Raúl Fernando Guerrero-Castañeda, Mateus Vieira Soares, Florencio Reverendo Anton Neto, Gildásio Souza Pereira, and Sylvia Maria Cardoso Bastos Veras. 2019. Nurse care for the hospitalized elderly’s spiritual dimension. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem 72: 236–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitorino, Luciano M., Raíssa Chiaradia, Gail Low, Jonas Preposi Cruz, Kenneth I. Pargament, Alessandra L. G. Lucchetti, and Giancarlo Lucchetti. 2018. Association of Spiritual/Religious Coping with Depressive Symptoms in High- and Low-risk Pregnant Women. Journal of Clinical Nursing 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Area of Knowledge | Number of Groups in the DRG | % in the DRG | RG with a Specific Focus or Research Line on Spirituality & Health | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Anthropology | 393 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | Bioethics | 5 | 0 | 1 |

| 3 | Education | 3595 | 9.6 | 1 |

| 4 | Nursing | 683 | 1.8 | 5 |

| 5 | Medicine | 1619 | 4.3 | 2 |

| 6 | Psychology | 884 | 2.4 | 3 |

| 7 | Public Health | 1079 | 2.9 | 1 |

| 8 | Theology | 104 | 0.3 | 2 |

| Total of selected research groups | 16 |

| Research Group or Research Line (RL) | Year of Creation | Localization | State | Area of Knowledge | Leaders | Research Line | Scientific Publications—Topics | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 RL | Palliative Care and Health- Related Quality of Life (9 RL) | 2011 | Pio XII Foundation Barretos | SP | Medicine | Paiva, BSR; Paiva, CE | Spirituality and Religiosity and their implications in the area of Health | Prayer; cancer patients and quality of life; health professionals and integration of S/R in care |

| 2 RG | Religiosity and Spirituality in Whole Health (RSWH) | 2013 | UNASP—Adventist University of São Paulo—SP | SP | Nursing | Meira, MDD; Abdala, GA | Health promotion in the family with attention to mental and spiritual health and health education | Lifestyle and religiosity; Quality of life; Adventism, religiosity and health of various populations |

| 3 RL | Research Group in Geriatrics and Gerontology (5 Research Lines) | 2014 | UFJF—Federal University of Juiz de Fora | MG | Medicine | Lucchetti, G; Lucchetti, ALG | Impact of religious and spiritual beliefs on physical and mental health of elderly/ repercussions for health professionals | Quality of life (of patients with chronic disease; elderly; pulmonary disease; mental health) teaching of S&H in graduation; Tools for approaching S/R in Health; Spiritual/ Religious coping in several populations: elderly, pregnant women, nursing professional; scale validation. Extensive production (linked to NUPES—see Section 4.1) |

| 4 RL | Qualitative Translational Research Center on Emotions and Spirituality in Health (5 Research Lines) | 2013/2016 | UFF—Fluminense Federal University—Niterói | RJ | Nursing | Pereira, ER; Silva, RMCRA | Spirituality and spiritual care | Spiritual care in nursing; elderly in long-term care facilities; meaning of life and nursing professional; cancer patients; people living with HIV |

| 5 RG | Spirituality/Religiosity in the context of Nursing and Health Care: Discursive Production and Social Representations | 2016 | UERJ—Rio de Janeiro State University | RJ | Nursing | Gomes, AMT; Marques, SC | Spirituality in the context of nursing and health care; Religiosity in the context of nursing and health care | Social representations of S/R in people living with HIV; drugs and treatment; spiritual/religious coping |

| 6 RG | Research Center in Bioethics and Spirituality—NUBE (2 Research Lines) | 2013/2018 | UESB—State University of Southwest Bahia—Jequié | BA | Bioethics | Yarid, SD | Spirituality and Health | Spiritual/Religious coping and maternal grief; ICU Health professionals and job well-being; S/R in the Brazilian Public Health System (SUS) |

| 7 RL | Center for Studies and Research on the Elderly—NESPI (7 Research Lines) | 1973/2017 | UFBA—Federal University of Bahia—Salvador | BA | Nursing | Menezes, TMO; Pedreira, LC | Spirituality and Health | 1 researcher—review and empirical studies on S/R and Health of elderly patients, family members and professionals |

| 8 RG | Spirituality and Health Research Group | 2019 | PUCPR Pontifical Catholic University of Paraná—Curitiba | PR | Theology | Esperandio, MRG (PUCPR); Freitas, MH (UCB) (Research prior to RG registration) | Bioethics and Palliative Care; Theology and Society, Mental health and therapeutic actions | Palliative care; spiritual care; spiritual/religious coping; scale validation; prayer; health professionals and integration of S/R in care; chaplaincy and mental health; health professionals |

| 9 RG | CURAS—Spirituality and Health Research Group | 2020 | UFPB—Federal University of Paraíba—João Pessoa | PB | Theology | Cavalcanti, APR (UFPB); Valente, TCO (UFRJ) (Research prior to RG registration) | Spirituality and Health | Patients living with HIV; scale validation |

| Research Group or Research Line (RL) | Year of Creation | Localization | Area of Knowledge | Number of Researchers | Researchers with Scientific Publication | Research Line | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Inter Psi—Laboratory of Psychosocial Studies: belief, subjectivity, culture & health (6 Research Lines) | 2010/2016 | USP—University of São Paulo—São Paulo | Psychology | 4 | Breno, M (1 production: health concepts of holistic therapists) | Belief, religiosity, spiritualities and health |

| 2 | Education and Health Studies (4 Research Lines) | 2014/2016 | UFCSPA—Federal University of Health Sciences of Porto Alegre | Health Education | 13 | Costa, MR (2 productions: teaching S/R for medical students; S/R in the Brazilian Public Health System—SUS) | Spirituality in Education and Health |

| 3 | ORÍ – Psychology, Health and Society Research Laboratory (3 Research Lines) | 2018 | USP—University of São Paulo—Ribeirão Preto | Psychology | 2 | Scorsolini-Comin, F (experience reports, case study, 2 empirical articles: psychotherapists; complaints of illness by Umbanda supporters (Also researcher at RG 6) | Religiosity/spirituality in health care |

| 4 | CuraRe: Collective of Studies on Religion and Healing (3 Research Lines) | 2018 | UFAL—Federal University of Alagoas | Anthropology | 6 | Rose, IS (2 productions: empirical research on Santo Daime and the Spiritism Center) | Religion, spirituality and health |

| 5 | Cardiovascular Health Research Group (7 Research Lines) | 2016/2020 | UFU—Federal University of Uberlândia | Nursing | 6 | Scalia, LAM (2 productions: experience report; empirical research on spiritism passes and health effects) | Spirituality/religiosity and cardiovascular health |

| 6 | Ethnopsychology (6 Research Lines) | 2020 | USP—University of São Paulo—Ribeirão Preto | Psychology | 2 | Scorsolini-Comin, F (experience reports, case study, 2 empirical articles: psychotherapists; complaints of illness by Umbanda supporters (Also researcher at RG 3) | Religiosity/spirituality in health care |

| 7 | Spirituality and Health Research Group | 2020 | UFRJ—Federal University of Rio de Janeiro | Collective Health | 6 | Moreira-Almeida, A (External researcher—UFJF—vast production linked to NUPES—see Section 4.1) | Environmental health and mental well-being; Well- being and mental disorders; Well-being and quality of life; Science and spirituality: personality and its contributions |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Esperandio, M.R.G. Spirituality and Health in Brazil: A Survey Snapshot of Research Groups. Religions 2021, 12, 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12010027

Esperandio MRG. Spirituality and Health in Brazil: A Survey Snapshot of Research Groups. Religions. 2021; 12(1):27. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12010027

Chicago/Turabian StyleEsperandio, Mary Rute Gomes. 2021. "Spirituality and Health in Brazil: A Survey Snapshot of Research Groups" Religions 12, no. 1: 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12010027

APA StyleEsperandio, M. R. G. (2021). Spirituality and Health in Brazil: A Survey Snapshot of Research Groups. Religions, 12(1), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12010027