Spirituality and Healthcare—Common Grounds for the Secular and Religious Worlds and Its Clinical Implications

Abstract

1. Introduction

- The personal quest for understanding answers to ultimate questions about life, meaning, and the relationship to the sacred or transcendent (King and Koenig 2009).

- The ways in which a person habitually conducts their life in relationship to the question of transcendence (Sulmasy 2009).

- A dynamic and intrinsic aspect of humanity, through which persons seek ultimate meaning, purpose, and transcendence, and experience relationship to self, family, others, community, society, nature, and the significant or sacred (Puchalski et al. 2014).

- A search for meaning, purpose, and transcendence and a connection to the significant or sacred (Sajja and Puchalski 2018).

- In a study involving medical schools in Brazil (Lucchetti et al. 2012), 54% of the directors or deans believed that spirituality should be taught to students (still deemed low); however, only 10% of all schools surveyed had dedicated courses.

- Although the practice of medicine requires a secular facade, an extensive study in the United States (Curlin et al. 2005) revealed that 55% of physicians declared their religious beliefs to clearly influence their clinical practice.

- Biofield healing (a secular counterpart of spiritual healing) fits well in the integrative model of healthcare, satisfying the desires of many patients; however, it remains outside the conventional framework, mainly because of its conceptual bases (Hufford et al. 2015).

- Spiritual experiences have important effects on biological, cognitive, and psychosocial domains; however, their role in the clinical setting has generated considerable discussion within the medical community (Giordano and Engebretson 2006).

2. Secular and Religious Intersection Concerning Spirituality and Healthcare

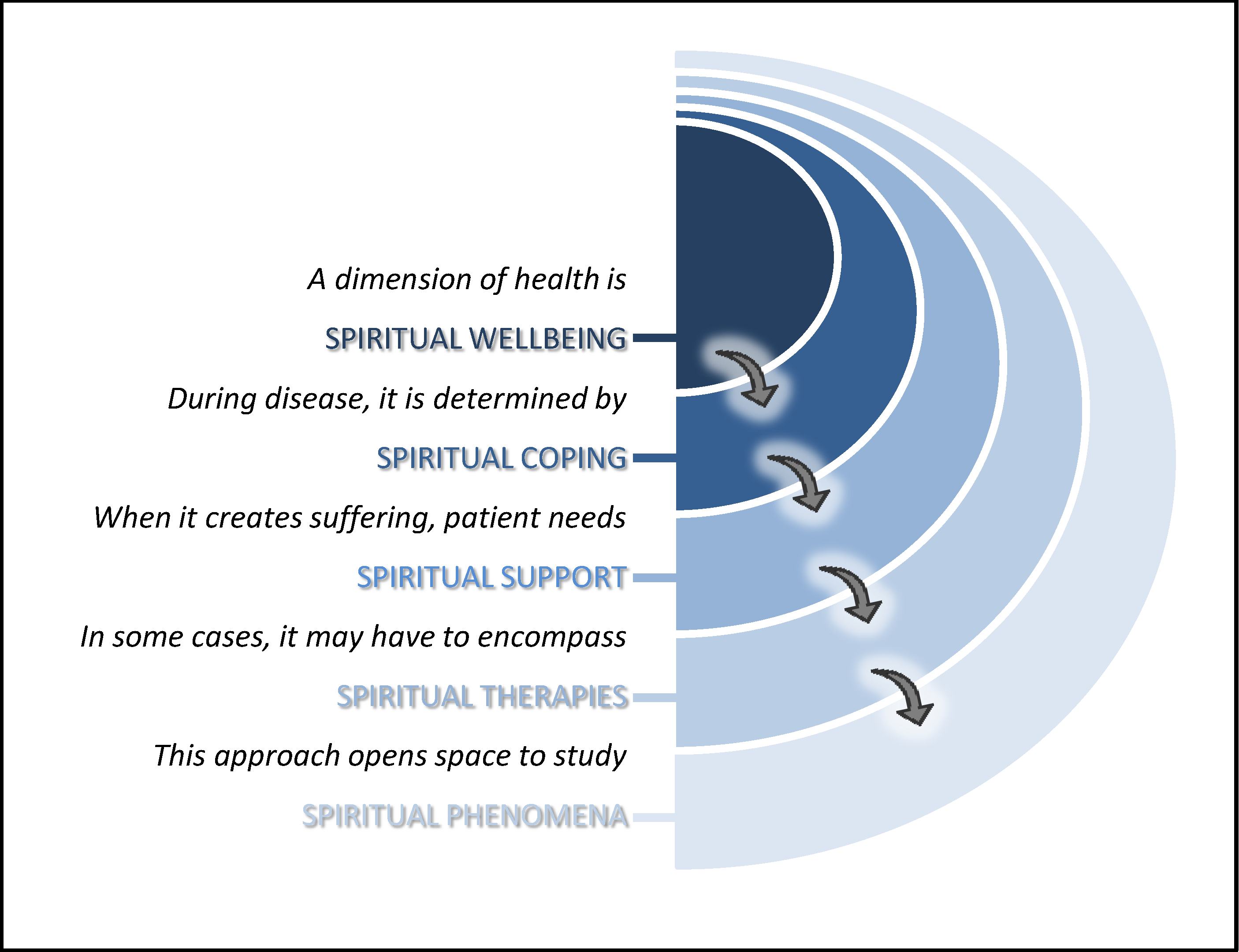

2.1. Spiritual Wellbeing

- Concept: a state of positive feelings, behaviours, and cognitions that provides the individual with a sense of identity, wholeness, satisfaction, joy, contentment, beauty, love, respect, constructive attitudes, inner peace and harmony, and purpose and direction in life (Gomez and Fisher 2003).

- Secular examples: positive thinking activating psycho-neuro-immune-endocrine pathways and balancing neurovegetative functions through modulation of stress (Saad and de Medeiros 2017).

- Religious examples: “your faith has healed you” (some biblical excerpts such as Mark 5:34); “a cheerful heart is good medicine, but a crushed spirit dries up the bones” (Proverbs 17:22); “[to fear the LORD and shun evil] will bring health to your body” (Proverbs 3:8).

- Common ground for both: independently of metaphysical issues, a positive and causal association exists between faith and positive parameters of physical and mental health, including longevity (Saad et al. 2019).

- Clinical implications: Healthcare staff should respect spiritual values and be attentive to the patient’s needs and beliefs related to the disease experience.

2.2. Spiritual Coping

- Concept: the cognitive and behavioural efforts to find or maintain meaning, purpose, and connectedness in the face of threatening or distressing situations (Clark and Hunter 2019). In other words, the faith-related attitudes used to deal with a crisis, or to modulate the resulting emotional distress.

- Secular examples: support from rationalistic and humanistic worldviews, liberal values, and analytic thinking for a meaningful and healthy life (Uzarevic and Coleman 2020).

- Religious examples: strength from prayer, sacred rituals, and religious symbols. Religious leaders, organisations, and communities are a primary source of support, comfort, guidance, and direct healthcare (WHO 2020).

- Common ground for both: the importance of restoring individual or cultural values to face an adverse experience.

- Clinical implications: healthcare professionals need to know about negative spiritual coping (anger, sorrow, guilt, stigma, struggle), which adversely affects the course of treatment by worsening stress. If needed, secular spiritual resources can be used.

2.3. Spiritual Support

- Concept: giving professional attention to the subjective spiritual and religious worlds of patients, concerning the relationship of the sacred to their illness, hospitalisation, and recovery or possible death (VandeCreek 2010).

- Secular examples: atheists and agnostics may need to discuss non-religious beliefs and questions about meaning and purpose, such as thinking about one’s legacy and life review (Crane 2017; Thiel and Robinson 2015).

- Religious examples: religious minister offering doctrinal counselling and sacraments in hospital, such as anointing of the sick for a Catholic patient near death.

- Common ground for both: spiritual needs are distinct from emotional and social ones, despite the interrelationship among them. Therefore, they are outside the range of psychological interventions.

- Clinical implications: spiritual support should be considered essential care; healthcare institutions should address questions regarding the spiritual dimension and they should have clear policies to foster resource aids (Hall 2020). For hospital quality accreditation, the Joint Commission International questions in its Standard PFR.1.2 claims: The hospital provides care that is respectful of the patient’s personal values and beliefs and responds to requests related to spiritual and religious beliefs1.

2.4. Spiritual Therapies

- Concept: mystical, religious, or spiritual practices performed for the benefit of health, as defined in the Medical Subject Headings2.

- Secular examples: procedures centred on the concept of a vital bioenergy, such as Yoga, Reiki, Qi Gong, and Johrei. This includes meditation (even if this practice has religious roots).

- Religious examples: procedures centred on the soul potentialities, such as blessings from various traditions and intercessory prayer.

- Common ground for both: the activation of inner hidden resources through a facilitator (the practitioner), regardless of the mechanisms of action that explain their effects.

- Clinical implications: despite the lack of uniformity on physiological responses and low clinical relevance of effects, a humanistic, comprehensive, and integrative healthcare approach should accompany patients in their aspirations and desires with sympathy and respect. Thus, healthcare providers should define their stance regarding the validity and utility of these approaches, as patients will inquire about them (Rindfleisch 2018).

2.5. Spiritual Phenomena

- Concept: unusual experiences that deviate from the generally accepted explanations of reality, the so-called parapsychological (psi) phenomena (Cardeña 2018).

- Secular examples: scientific reports on memories of alleged past lives, with many cases of a match, near-death experiences with elements not related to hallucination, and end-of-life experiences with the embarrassing terminal lucidity (Daher et al. 2017).

- Religious examples: mystical states, such as ecstatic enlightenment, possession trance, prophesy, and mediumship (after-death communication).

- Common ground for both: the acknowledgement of the consciousness expressions complexity and the attempt to gain a deeper understanding of human condition.

- Clinical implications: clinicians should accommodate patients’ specific desires and needs related to spiritual experiences, as the outcomes may be potentially health promoting (Giordano and Engebretson 2006). However, the practitioner must check if a strange behaviour is benign or pathological, through the differentiation between healthy spiritual experiences and mental disorders with religious content (Moreira-Almeida 2013).

3. Discussion

4. Implication and Limitations of the Present Rationalisation

- A secular hint to religiously-oriented professionals: you can hold your faith to get the strength to face the professional challenges, but keep in mind that, most of the time, clinical practice demands physicalist premises and reductionist methods; you can always follow your personal commitments by referring the patient to another colleague in sensitive cases, such as abortion or euthanasia.

- A religious hint to secularly-oriented professionals: although some religious interpretations can be harmful to healthcare, our role is to give the patients the best information and allow them to decide; the acknowledgement of religious values of a patient is a very important ingredient of cultural sensitivity, and the respect for such needs is key for a patient-centred approach.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Balboni, Michael J., Christina M. Puchalski, and John R. Peteet. 2014. The relationship between medicine, spirituality and religion: Three models for integration. Journal of Religion and Health 53: 1586–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bredle, Jason M., John M. Salsman, Scott M. Debb, Benjamin J. Arnold, and David Cella. 2011. Spiritual Well-Being as a Component of Health-Related Quality of Life: The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy—Spiritual Well-Being Scale (FACIT-Sp). Religions 2: 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardeña, Etzel. 2018. The experimental evidence for parapsychological phenomena: A review. American Psychologist 73: 663–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, Clayton C., and Jennifer Hunter. 2019. Spirituality, spiritual well-being, and spiritual coping in advanced heart failure: Review of the literature. Journal of Holistic Nursing 37: 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crane, Tim. 2017. The Meaning of Belief: Religion from an Atheist’s Point of View. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 224p, ISBN 9780674088832. [Google Scholar]

- Curlin, Farr A., John D. Lantos, Chad J. Roach, Sarah A. Sellergren, and Marshall H. Chin. 2005. Religious Characteristics of U.S. Physicians. Journal of General Internal Medicine 20: 629–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daher, Jorge Cecílio, Jr., Rodolfo Furlan Damiano, Alessandra Lamas Granero Lucchetti, Alexander Moreira-Almeida, and Giancarlo Lucchetti. 2017. Research on experiences related to the possibility of consciousness beyond the brain: A bibliometric analysis of global scientific output. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 205: 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhar, Neera, S. K. Chaturvedi, and Deoki Nandan. 2013. Spiritual health, the fourth dimension: A public health perspective. WHO South-East Asia Journal of Public Health 2: 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyson, Freeman J. 2012. Is Science Mostly Driven by Ideas or by Tools? Science 338: 1426–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, James, and Joan Engebretson. 2006. Neural and Cognitive Basis of Spiritual Experience: Biopsychosocial and Ethical Implications for Clinical Medicine. EXPLORE 2: 216–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, Rapson, and John W. Fisher. 2003. Domains of Spiritual Well-Being and Development and Validation of the Spiritual Well-Being Questionnaire. Personality and Individual Differences 35: 1975–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, Daniel E. 2020. We Can Do Better: Why Pastoral Care Visitation to Hospitals is Essential, Especially in Times of Crisis. Journal of Religion and Health 59: 2283–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herman, Joseph. 2001. Medicine: The science and the art. Medical Humanities 27: 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirpa, Meron, Tinsay Woreta, Hilena Addis, and Sosena Kebede. 2020. What matters to patients? A timely question for value-based care. PLoS ONE 15: e0227845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hufford, David J., Meredith Sprengel, John A. Ives, and Wayne Jonas. 2015. Barriers to the entry of biofield healing into “Mainstream” healthcare. Global Advances in Health and Medicine 4: 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hvidt, Niels Christian, and Elisabeth Assing Hvidt. 2019. Religiousness, Spirituality and Health in Secular Society: Need for Spiritual Care in Health Care? In Spirituality, Religiousness and Health—From Research to Clinical Practice. Edited by Giancarlo Lucchetti, Mario Fernando Prieto Peres and Rodolfo Furlan Damiano. Berlin: Springer, pp. 133–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, Kathleen S., Jennifer L. Hay, and Erica I. Lubetkin. 2016. Incorporating Spirituality in Primary Care. Journal of Religion and Health 55: 1065–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiràsek, Ivo. 2013. Verticality as Non-Religious Spirituality. Implicit Religion 16: 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, Michael B., and Harold G. Koenig. 2009. Conceptualising spirituality for medical research and health service provision. BMC Health Services Research 9: 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, Harold G. 2012. Religion, Spirituality, and Health: The Research and Clinical Implications. International Scholarly Research Network Psychiatry 2012: 278730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, Harold G. 2020. Maintaining Health and Well-Being by Putting Faith into Action During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Religion & Health 59: 2205–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, Jeff. 2018. The Discourse on Faith and Medicine: A Tale of Two Literatures. Theoretical Medicine and Bioethics 39: 265–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, Jeff. 2020. The Faith Community and the SARS-CoV-2 Outbreak: Part of the Problem or Part of the Solution? Journal of Religion & Health 59: 2215–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchetti, Giancarlo, Alessandra Lamas Granero Lucchetti, Daniele Corcioli Mendes Espinha, Leandro Romani de Oliveira, José Roberto Leite, and Harold G Koenig. 2012. Spirituality and Health in the Curricula of Medical Schools in Brazil. BMC Medical Education 12: 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McSherry, Wilfred, and Keith Cash. 2004. The Language of Spirituality: An Emerging Taxonomy. International Journal of Nursing Studies 41: 151–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Jon T. 2017. Multicultural and idiosyncratic considerations for measuring the relationship between religious and secular forms of spirituality with positive global mental health. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 9: 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira-Almeida, Alexander. 2013. Religion and health: The more we know the more we need to know. World Psychiatry 12: 37–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, Sadhu Charan. 2006. Medicine: Science or Art? Mens Sana Monographs 4: 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul Victor, Chitra G., and Judith V. Treschuk. 2020. Critical Literature Review on the Definition Clarity of the Concept of Faith, Religion, and Spirituality. Journal of Holistic Nursing 38: 107–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, James S. 2016. Advocating for a Bio-Psycho-Social-Spiritual Approach to Hospice and Palliative Care. Annals of Clinical Case Reports 1: 1006–7. [Google Scholar]

- Puchalski, Christina M., Robert Vitillo, Sharon K. Hull, and Nancy Reller. 2014. Improving the Spiritual Dimension of Whole Person Care: Reaching National and International Consensus. Journal of Palliative Medicine 17: 642–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinert, Katia Garcia, and Harold G. Koenig. 2013. Re-examining definitions of spirituality in nursing research. Journal of Advanced Nursing 69: 2622–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rindfleisch, James Adam. 2018. Biofield Therapies. In Integrative Medicine, 4th ed. Edited by David Rakel. Philadelphia: Elsevier Inc., pp. 1073–80.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, Marcelo, and Roberta de Medeiros. 2017. The Continuum of Mind-Body Interplay—From Placebo Effect to Unexplained Cures. Medical Science & Healthcare Practice 1: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Saad, Marcelo, Roberta de Medeiros, and Amanda Mosini. 2017. Are We Ready for a True Biopsychosocial–Spiritual Model? The Many Meanings of ‘Spiritual’. Medicines 4: 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saad, Marcelo, Jorge Cecílio Daher, and Roberta de Medeiros. 2019. Spirituality, Religiousness, and Physical Health: Scientific Evidence. In Spirituality, Religiousness, and Health—From Research to Clinical Practice. Edited by Giancarlo Lucchetti, Mario Fernando Prieto Peres and Rodolfo Furlan Damiano. Berlin: Springer, pp. 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajja, Aparna, and Christina Puchalski. 2018. Training Physicians as Healers. AMA Journal of Ethics 20: E655–E663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schumann, Cristiane, André Stroppa, and Alexander Moreira-Almeida. 2011. The contribution of faith-based health organizations to public health. International Psychiatry 8: 62–64. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6735024/ (accessed on 5 September 2020). [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Skinner, Daniel, and Kyle Rosenberger. 2018. Toward a More Humanistic American Medical Profession: An Analysis of Premedical Web Sites from Ohio’s Undergraduate Institutions. Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development 5: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sloan, Richard P., Emilia Bagiella, Larry VandeCreek, Margot Hover, Carlo Casalone, Trudi Jinpu Hirsch, Yusuf Hasan, Ralph Kreger, and Peter Poulos. 2000. Should physicians prescribe religious activities? New England Journal of Medicine 342: 1913–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulmasy, Daniel P. 2009. Spirituality, Religion, and Clinical Care. Chest 135: 1634–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiel, Mary Martha, and Mary Robinson. 2015. Spiritual Care of the Non-Religious. PlainViews 12: 1–12. Available online: https://www.professionalchaplains.org/Files/resources/reading_room/Spiritual_Care_Nonreligious.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2020).

- Toon, Peter. 2012. Health care is both a science and an art. The British Journal of General Practice 62: 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Unterrainer, Human-Friedrich, Karl Heinz Ladenhauf, M.L. Moazedi, Sandra Johanna Wallner-Liebmann, and Andreas Fink. 2010. Dimensions of Religious/Spiritual Well-Being and Their Relation to Personality and Psychological Well-Being. Personality and Individual Differences 49: 192–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzarevic, Filip, and Thomas J. Coleman, III. 2020. The Psychology of Nonbelievers. Current Opinion in Psychology. Pre-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VandeCreek, Larry. 2010. Defining and Advocating for Spiritual Care in the Hospital. Journal of Pastoral Care & Counseling 64: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walach, Harald. 2017. Secular spirituality—What it is. Why we need it. How to proceed. Journal for the Study of Spirituality 7: 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO (World Health Organization). 2020. Practical Considerations and Recommendations for Religious Leaders and Faith-Based Communities in the Context of COVID-19. WHO Reference Number: WHO/2019-nCoV/Religious_Leaders/2020.1. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1274420/retrieve (accessed on 5 September 2020).

- Wixwat, Maria, and Gerard Saucier. 2020. Being spiritual but not religious. Current Opinion in Psychology 40: 121–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | Joint Commission International Accreditation Standards for Hospitals, 5th ed. 2013. Available from http://www.jointcommissioninternational.org/assets/3/7/Hospital-5E-Standards-Only-Mar2014.pdf. |

| 2 | The vocabulary thesaurus for indexing articles can be found in the database PubMed. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mesh. |

| Expression | Secular Examples | Religious Examples | Common Ground for Both | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spiritual wellbeing | Positive thinking and psycho-neuro-immune-endocrine pathways | “your faith has healed you” (Mark 5:34 and other biblical excerpts) | Faith affects physiology, independently of metaphysical issues | Respect spiritual values and be attentive to patient’s feelings and beliefs |

| Spiritual Coping | Support from rationalistic and humanistic worldviews | Prayer, sacred rituals, religious symbols, and faith community | Restore individual or cultural values to face an adverse experience | Know about negative coping, which affects treatment and worsens stress |

| Spiritual Support | Discussions on non-religious beliefs related to meaning and purpose. | Religious minister offering doctrinal counselling and sacraments | Spiritual needs are distinct from emotional and social needs, despite their interrelationship | Healthcare institutions should address questions regarding the spiritual dimension |

| Spiritual Therapies | Procedures centred on the vital bioenergy: Yoga, Reiki, etc., including meditation | Procedures centred on the potentialities of the soul: blessings, intercessory prayer, etc. | Activation of inner hidden resources through a facilitator | Accompany patients in their aspirations and desires with sympathy and respect |

| Spiritual phenomena | Scientific reports: memories of past lives, near-death experience, and end-of-life experiences | Mystical states: ecstatic enlightenment, possession trance, mediumship, and prophesy | Acknowledgement of the complexity of consciousness expressions | Accommodate patients’ values, while checking for mental illness |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saad, M.; de Medeiros, R. Spirituality and Healthcare—Common Grounds for the Secular and Religious Worlds and Its Clinical Implications. Religions 2021, 12, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12010022

Saad M, de Medeiros R. Spirituality and Healthcare—Common Grounds for the Secular and Religious Worlds and Its Clinical Implications. Religions. 2021; 12(1):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12010022

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaad, Marcelo, and Roberta de Medeiros. 2021. "Spirituality and Healthcare—Common Grounds for the Secular and Religious Worlds and Its Clinical Implications" Religions 12, no. 1: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12010022

APA StyleSaad, M., & de Medeiros, R. (2021). Spirituality and Healthcare—Common Grounds for the Secular and Religious Worlds and Its Clinical Implications. Religions, 12(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12010022