This essay argues that the distinctive aesthetic practices of many African American Christian congregations, indexed by the phrase “the Black gospel tradition”, are shaped by a sacramentality of sound. I contend that the role music routinely plays in the experience of the holy uncovers sanctity in the sound itself, enabling it to function as a medium of interworldly exchange. As divine power takes an audible form, the faith that “comes by hearing” is confirmed by religious feeling—both individual and collective. This sacramentality of sound is buttressed by beliefs about the enduring efficacy of divine speech, convictions that motivate the intensive character of gospel’s songs, sermons, and shouts. The essay begins with a worship service from Chicago, Illinois’ Greater Harvest Missionary Baptist Church, an occasion in which the musical accompaniment for holy dancing brought sound’s sacramental function into particularly clear relief. In the essay’s second section, I turn to the live recording of Richard Smallwood’s “Hebrews 11”, a recording that accents the creative power of both divine speech and faithful utterances, showing how reverence for “the word of God” and the veneration of musical sound sustain each other. In the article’s final segment, I show how both the aforementioned performances articulate a sacramental theology of sound—the conviction that sound’s invisible force brings spiritual power to bear on the material world.

1. Ritual Sound

While worship services at Chicago’s Greater Harvest Missionary Baptist Church often become an ecstatic fusion of music and movement, an excerpt from a service in January 2016 reveals the theology that precedes these physical expressions of religious belief. At 8 p.m. on the first Sunday of each month, the church holds its customary communion service, a worship event designed around the celebration of the Lord’s Supper. This monthly observance is common among many Black protestant congregations. While it is customary to arrange the communion elements—trays, bread, wine, and sheets—before the service, Greater Harvest bids congregants to watch as the unadorned pulpit is transformed into a space for communion. During Greater Harvest’s communion service, deacons and deaconesses decked in white and red contribute to the sacred scene, walking one-by-one in a line. One deaconess sweeps the pulpit off with a small broom. Another group of deacons roll in a modified table whose sides fold down to reveal plates prepared with elements to be distributed to congregants. In so doing, they reveal the reverential preparation that has occurred before the service began. As one member of Greater Harvest notes: “the deaconesses who prepare the communion have an entire room dedicated for that purpose. While they do their work, there is no talking.”

2 Even before the pastor proclaims the words of institution, then, these sacred symbols echo the following invocation: “the Lord is in his holy temple; let all the earth keep silent before him.”

3 However, while the deaconesses acknowledge the presence of God through their silences on Saturday, on Sunday, the entire congregation incarnates that presence with joyful noise.

Among the dozens of Greater Harvest services that I have attended, the 8 p.m. service on Sunday, 5 January 2016 was most instructive. Between the sermon and the celebration of the communion service, the pastor, Elder Eric Thomas, began to sing the refrain of Margaret Douroux’s canonical gospel selection, “He Decided to Die.” Though located in Chicago’s Washington Park neighborhood, this sanctuary perceptibly moved toward the scene of the crucifixion as pastor, choir, and congregation incessantly sang, “He would not come down from the cross just to save himself. He decided to die just to save me.” As this assembly repeatedly elevated their vocal parts, the transcendent proximity that the Lord’s Supper offers to Christ’s Passion became a tangible reality in the liminal space of worship. While the performance of “He Decided to Die” continued, congregants used their bodies to offer praise and to incarnate divine presence. Joining a chorus of embodied demonstrations, two women stood and ran, in trance, around the sanctuary, foreshadowing the collective ecstasy that would soon emerge.

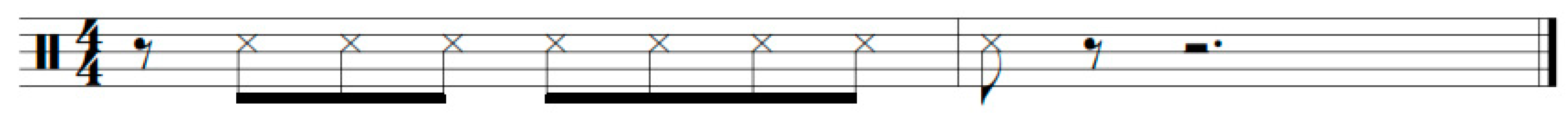

Soon enough, the performance of Douroux’s “He Decided to Die” gave way to an ecstatic period of holy dancing. Instead of reiterating that song’s material, the band began to play fast, repetitive musical patterns often used to accompany holy dancing; practitioners refer to this as “shouting music.” As they played, the pastor vented the feeling that seemed to course throughout the building, exclaiming “I feel the Holy Ghost” before turning to dance for a moment—transferring his weight between his feet in synchrony with the band’s “shouting music.” These are all actions that affirm that “the shout”, one common name for the gospel church’s holy dance, functions as an embodiment of divine presence. While his congregants sustained this physical form of praise, Elder Thomas rhythmically intoned phrases like “the blood of Jesus” and “got my joy”, turning the preceding song’s Eb major tonic into a reciting tone. The musicality of Thomas’s elevated speech amplified the repetitive shape of the “shouting music” by which he was accompanied. Later, while the musicians iterated the metric and tonal framework of the shouting music, Elder Thomas, himself a renowned organist, turned to the band and gestured with his hand the rhythm that is depicted in

Figure 1:

Elder Thomas then said, “I just felt that in my spirit.”

4 What was it that the pastor felt? This question’s musical answer emerged just a few moments later when the band started to play the material that is represented in

Figure 2, an elaborated version of the pattern that the pastor signaled to the band.

As

Figure 2 illustrates, the musicians turn a simple gestured rhythm into a riff, adding a pitch contour and harmonic scheme to it. However, the story is more complicated. It is likely that, by “playing” the rhythm in the air, Thomas summoned a shouting music formula that was already known and loved by members of the congregation. In either case, through this emphatic and empathetic musical transition, this team of musicians breathed new life into the collective embodiment of religious ecstasy.

As the bodies entrained to the musical framework constructed around this riff, an even greater sense of musical coordination served as proof of their pastor’s assertion that this music had arisen in his (and other congregants’) spirit. It was as if he could feel just what rhythm, just what riff, just what sound the people needed to access the highest form of communal praise. As more people partook of the spontaneous but regularized movements of the holy dance, believers used their bodies to articulate gospel’s fusion of musical sound and the Holy Spirit. By gesturing a very specific rhythmic phrase and exclaiming, “I just felt that in my spirit”, Thomas elevates musical syntax to the realm of sacrality, disclosing what Katherine Hagedorn calls a “theology of sound”: “talk about music [that] reveals deeply embedded ideologies about identity and territoriality—literally one’s place in the world.”

5 Thomas’s statement about the sound felt in his spirit exemplifies “how the function of sound is theorized by musicians and adherents within a religious context, such that ‘divinely targeted sound,’ as well as discourse about that sound, map the experience of divine transcendence onto a human grid.”

6 The bit of music depicted in

Figure 1, the evocative rhythm that inflected this moment in the service, is what Thomas says he felt in his spirit. This statement conjoins the invisible subject of the congregation’s belief with the audible object of collective experience, contending that the modification of what congregants hear will bring them closer to what they cannot see. Feeling, Thomas suggests, mediates between sight and sound. This scene from Greater Harvest offers an instructive example of how other congregations experience the Holy Spirit through music.

Thomas’s “theology of sound” bears striking resemblance to the snippet with which this essay began: “I love it when you play that Holy Ghost chord.” The sentiment that Thomas, both musician and pastor, expresses here feels quite similar to that of the parishioner who uttered the preceding words. Now, we have gone from a Holy Ghost chord to a Holy Ghost rhythm, or, a musical pattern “felt in one’s spirit.” In both cases, feeling the spirit and feeling the music become synonymous; musical sound becomes a channel of divine power. How, then, to categorize this convergence of the material and the divine, the sensuous and the spiritual? To answer this, I want to return to the context of the performance in question—a celebration of communion. What if one uses the concomitance of the Lord’s Supper and this period of ecstatic dancing to interpret sound’s function in this moment of corporate worship? To do so would be to contend that gospel’s embodied engagement with musical sound be understood in sacramental terms. That is my approach, an argument that builds from the philosopher James K. A. Smith’s proposal that “that there is a kind of sacramentality of Pentecostal worship that sees the material as a good and necessary mediator of the Spirit’s work and presence.”

7 Yes, I want to explain music’s peculiar power with reference to sacramentality. While sacraments are traditionally defined as “external signs instituted by Christ to give grace”, the notion of sacramentality has been applied much more broadly, naming the manifold media through which God is revealed; some call this the “sacramental principle.”

8 In many Black Protestant churches, sound occupies a primary place in the sacramental economy; this is evidenced by the forms of musical and emotive worship that are indexed by the term “the Black gospel tradition.”

9 On this, I agree with Louis Chauvet’s argument that “to theologically affirm sacramental grace is to affirm, in faith, that the risen Christ continues to take flesh in the world and in history and that God continues to come into human corporality.” Rather than any single liturgical element, the body, Chauvet contends “is acknowledged as the place of God, provided we understand the body…to be the archsymbol in which, in a way proper to each person, the connections to historical tradition, the present society, and the universe—connections which dwell in us and are the fabric of our identity—are knitted together.”

10 I claim that the robustly embodied engagement that practitioners have with the songs, sermons, and prayers that are conventional in these liturgical contexts expresses the grace that believers receive through these aesthetic forms. The intense forms of sociality that emerge in ecstatic moments of Black worship—in songs, sermons, and shouts—offer fleeting glimpses of the sacramental unity of the body of Christ.

Musical sound’s ability to direct collective attention to the presence of holiness becomes particularly clear when examining its instrumental forms. As it moves away from human speech, purely instrumental musical sound puts forth a transcendent manifestation of what Nina Eidsheim, following Pierre Schaeffer, has called “the acousmatic question.”

11 While it is quite clear that no one is

singing, the acousmatic question asks: who is

speaking through the instrument? As the Hammond organist for Rev. Clay Evans’ 2003 recording of the gospel standard, “All Night, All Day”, Elder Eric Thomas performed two, evocative solos of the tune in question; his solos punctuated the choir’s declaration of these treasured lyrics: “All night, all day the angels keep watching over me, me, my Lord.” Before the second solo, Rev. Evans’ said, “Eric, I want you to say it again on the organ.” In so doing, Rev. Evans affirmed that while organs, pipe and electric, mechanical and synthesized, often seem tethered to a chameleonized sonic politics, that is, a need or desire to sound like some other instrument—the work of the Hammond organ seems specifically preoccupied with sounding like the human voice. As Thomas’s organ spoke, it recruited bluesy melismatic passagework, using the full range of timbral techniques afforded by the Hammond organ’s drawbars, echoing and then exceeding the sung versions of the melody. Listening to the recording, one hears the efficacy of the organ’s speech: congregants shriek, using their voices and bodies to bear witness to the message of this song. Attending to that believer’s scream, one might wonder if she had sensed the presence of an angel—the emblem of protection, past or future—as the song mediated between the seen world and another. In this case, an instrumental solo’s pursuit of human vocality made it an even more effective channel of divine grace than the collected voices of the Fellowship Missionary Baptist Church Choir. This, perhaps counterintuitive, proposal is buttressed by the fact that the most arresting exclamations from members of the congregation seem to arise while Elder Thomas solos on the organ. That musical sound routinely elicits such wanton forms of religious reaction attests to its capacity to convey sacred force; this is sacramentality.

Yet, the use of sacramentality to name sound’s interworldly efficacy might seem dissonant with certain fundaments of Black Baptist theology and practice, one pervasive strain of which was forcefully articulated in Edward Thurston Hiscox’s highly influential

The Standard Manual for Baptist Churches (1890):

Christian ordinances, in the largest sense, are any institutions, or regulations of divine appointment, established as means of grace for the good of men, or as acts of worship for the honor of God. In that sense, not only are baptism and the Lord’s Supper ordinances, but preaching, prayer, hearing the word, fasting, and thanksgiving are also ordinances, since all are of divine appointment. But, in a narrower sense, it is common to say that

baptism and the

Lord’s Supper are the only ordinances appointed by Christ to be observed by his churches.

12

Crucially, Hiscox contends that these “emblematic and commemorative rites….are not

sacraments, as taught by some…”

13 However, this line of thought has not gone altogether unchallenged; Baptist polity affords great diversity, for, as Bill Leonard notes, “Baptists themselves often differ as to doctrinal definitions and approaches to ministry.”

14 While attending many of Greater Harvest’s Communion Services, I often heard Pastor Thomas refer to the communion elements as sacraments. That the notion of sacraments arises in Thomas’s discussions of the Lord’s Supper testifies to sacramentality’s place in his religious imagination, inviting one to understand his claim to feel a rhythm “in his spirit” as a sacramental assertion.

Pastor Thomas’s “theology of sound” is aptly understood as sacramental; it views musical sound as a means of grace, a conduit of divine presence that is acknowledged with the body. However, this theology is not Thomas’s alone. In fact, James Cone contends that “the truth of Black religion is not limited to the literal meaning of the words. Truth is also disclosed in the movement of the language and the passion created when a song is sung in the right pitch and tonal quality. Truth is found in shout, hum, and moan as these expressions move the people closer to the source of their being.”

15 What truth does sound convey? The presence of God on the side of the oppressed would seem to be Cone’s reply. Musical sound is uniquely suited to making this presence palpable. What does music have in common with divinity? I propose that musical sound’s invisible immanence is its most valuable sacred attribute; it is the condition of music’s operative and “sensibly perceptible … likeness” to the divine.

16 Alongside its systematic malleability—the fact that musical sound can be transformed in accordance with shared systems of organization—its sensible, yet invisible ontology enables it to evoke the holy, drawing congregants into an enfleshed experience of belief. While “ordinance” is the typical term for rites in Black Baptist worship, the modality that gospel congregants use to think about and use musical sound calls for a different category.

2. Musical Sound and the Power of the Word

Gospel’s sacramentality of sound is motivated by beliefs about the power of divine speech, convictions that come into particularly stark relief in Richard Smallwood’s song, “Hebrews 11”, which was premiered at his 2014 recording,

Anthology: Live. As its title suggests, the song is a rendering of a New Testament text; it is also an invitation to reimagine a familiar and foundational text as a source of musical sound. The opening moments of Smallwood’s “Hebrews 11” use a polyphonic melisma to herald the drama of this piece. The melisma’s canonic opening, the gravity of its

maestoso beginning, the mounting accumulation of choral sound, and the marked modulation from E<flat> minor to E<flat> major, work in tandem to gather the audience’s attention, building anticipation for the song’s first plain lyrics: “Now faith is the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things we cannot see.”

17 Unlike many Smallwood songs, which present original lyrics before summoning saintly texts, the

A section of this paraphrase begins with the first verse of Hebrews’ 11th chapter, asserting, from the outset, a particularly close relationship to its scriptural source. As it replaces the introduction’s sequential, chromatic complexity with a more conventional chord progression, the harmonic support of this opening statement reinforces the sheer centrality of Hebrews 11:1 to what I call “the gospel imagination.”

18How to characterize this scripture’s significance? The second verse offers an instructive reply. This song ever so slightly loosens the song’s connection to the scripture by rendering Hebrews 11:3 as, “by faith, the universe was created by God’s word, so what we view is formed by what we can’t see.”

19 In so doing, Smallwood altogether skips Hebrews 11:2 in order to conjoin verse 3 and verse 1. This compositional decision has theological and philosophical inspirations: it forges a musical, textual, and conceptual linkage between the first verse’s definition of faith as an unseen substance and the third verse’s assertion that holy words played a key role in making the material world. By placing this early accent on the creative power of divine speech, Smallwood exhorts believers to understand God’s word—read, spoken, and sung—as an efficacious force: the substance of faith.

With two escalating iterations of the interjection, “oh”, the song transitions into its

B section, a shift that produces a lyrical exchange between versions of Hebrews 11—from the scripture to the song. In this bridge, the choir proclaims, “by this same faith healing is mine. By this faith wholeness is mine. By faith mountains will move. Victoriously, I will come through.”

20 Iterated twice, these lyrics comprise the only original—that is, neither paraphrased nor quoted—text in the song. Moreover, while section

B is obviously the song’s middle section, this material’s formal location mirrors its role as a kind of transcendent conjunction. In its discussion of “this faith”—the faith described in the text as “the same faith” that those who sing and listen will use to achieve healing and wholeness, to move mountains, and to experience victory—“Hebrews 11” does more than merely cite scripture: it makes an argument about the mutability of time and space. In this way, Smallwood asserts that the contemporary singing of sacred words provides access to the world-making power of divine speech, using unseen energy to transform material circumstances.

Believers know this by their faith, a faith that both scripture and song define as the substance of things hoped for and the evidence of things not seen; but what is this substance? What is faith’s evidence? I would argue that, in this tradition, musical sound is one of the substances through which faith takes form. I mean to accent the way faith is shaped by, carried in, and expressed through musical sound. Additionally, although it cannot be seen, this sonic materiality is still substantial: it is a foundation of faith. As St. Paul wrote, “faith comes by hearing.”

21 When I spoke with Richard Smallwood about his music, he linked gospel song and divine speech:

I am adamant about making sure that whatever I write is scripturally correct. I just think, you know, gospel music is also the truth, so whatever we put out there for people to hear has to be the truth. I think so many times people put their own theology or their own personal opinions in their lyrics—and I think that it’s important that we put what the word of God

says, so that when people hear it they’ll hear what God

says.

22

Smallwood wants audiences who hear his music to hear what God says. Not what God

said, but what God

says. Note well Smallwood’s use of the present tense. Twice in this one reply Smallwood identifies an aural element in sacred writ; since “the word of God” speaks, his communicative desire is for audiences to “hear what God says”

23 through his music. How does this desire shape compositional strategy? In the third section of “Hebrews 11”, its vamp, Smallwood orchestrates a striking resonance with the song’s scriptural source. As the choir iterates the lyrics “by faith”, Smallwood interpolates the text from the rest of Hebrews 11:

(By faith) We understand the worlds were framed by God’s Word.

(By faith) Abel offered unto God a more excellent sacrifice than Cain, Hah!

(By faith) Enoch was translated, that he should not see death.

(By faith) Noah prepared an Ark, to the saving of his house.

(By faith) Isaac blessed Jacob and Esau, concerning things to come.

(By faith) The Children of Israel passed through the Red Sea, and by dry land.

(By faith) The walls of Jericho fell down, after they were compassed about seven days.

(By faith) The prophets, subdued kingdom, worked righteousness;

(By faith) Obtained promises; stopped the mouths of lions;

(By faith) Quenched the violence of fire; escaped the edge of the sword;

(By faith) Out of weakness, were made strong, became valiant in battle.

At the same time, Smallwood’s mode of vocalization is transformed; as he moves from song to speech, instead of the more characteristic sermonic movement from speech to song, he enacts an arresting inflection, calling heightened attention to this part of the song. When joined to the choir’s repeated lyric, these interpolations reanimate the remainder of Hebrews’ 11th chapter, actualizing the work of this song’s discourse on faith. Like the epistle, the vamp of Smallwood’s paraphrase defines faith through a host of exemplars—Abraham, Enoch, and Noah, among others. In so doing, this heightened moment of “Hebrews 11” forges an unlikely, sacramental kind of connection, “deepening our interior life by rendering it alive and passionate and bring[ing] us into relation and communion with others.”

25While one might call this song a paraphrase of its scriptural foundation, this is a case where the term “paraphrase” may be insufficient. If one were to compare the lyric of Smallwood’s vamp to the text of Hebrews 11, striking structural similarities would become apparent. The homology between the formal structure of the scripture and this section of the song points to deeper resonances between the two texts. For, while Hebrews is often referred to as the Epistle to the Hebrews, the content of this portion of the New Testament is essentially sermonic. As New Testament scholar Kenneth Schenck observes, Hebrews’ “discourse—the way the words of its text are presented to the reader—is a sermon that makes arguments.”

26 Hebrews might then be thought of as the transcript of a speech act, whether actual or imagined. Thinking of Hebrews in homiletic terms, instead of only in epistolary ones, invites the auditor to think rhetorically. For instance, New Testament scholar Ceslas Spicq argues that Hebrews 11 contains “the best example of anaphora in the entire bible.”

27 Both because of its grammar and its location in the bible, Hebrews 11 functions as the rhetorical climax of the text. Given such emphasis and such recursion, we might say that Hebrews 11 is

the vamp of the epistle. What is the effect of this structural similarity? What meaning arises from this song’s profound connection to scripture?

3. Sound and Sacramentality

In the song’s vamp, Smallwood helps listeners “hear what God says”, by mirroring the scripture’s rhetorical form. More than just a resourceful compositional decision, the structural similarity between these two versions of Hebrews 11 reveals Smallwood’s theology of musical sound, aptly summarized in one of his Facebook posts: “Music is spiritual. It comes from the spiritual realm and goes beyond our ears, and into our spirits. Spirit recognizes spirit.”

28 Here, Smallwood explains music’s peculiar affect with reference to otherworldly origins, in view of which, auditory perception is preceded by spiritual contact. Musicking, then, more than an ordinance of the church, must be an inherently transcendent endeavor. As the fuel for these efforts, musical sound functions sacramentally. Moreover, Smallwood describes sound as an interworldly material, an energy that travels between worlds sustaining connections between believers and the invisible subjects of their belief. This way of thinking about sound is sustained by scriptural traditions that depict divine speech as a source of transformative power. Indeed, at the live recording of “Hebrews 11”, between the song’s first ending and the reprise of its vamp, Smallwood exhorted his audience about the efficacy of faithful utterances:

The Bible says all you need is a grain the size of a mustard seed, and you can speak to the mountain, and that mountain has to move. It might be sickness, but it’s got to move. It might be depression, but it’s got to move. It might be heartache, but it’s got to move. It might be grief, but it’s got to move. When you use your faith, things begin to happen, things begin to change. There’s nothing impossible, as long as you have faith, faith!

29

As Smallwood weaves together treasured passages from Matthew 17:20; 21:18–22; and Mark 11:20–24, he uses these scriptures to interpret his setting of another. What emerges in the dialectic between Hebrews 11 and these other texts is a description of sound’s role in making and remaking the world. Smallwood’s expression resonates with many pericopes in both the Old and the New Testament. In Isaiah 55, the prophet describes God sending out a word that will not return as void, but, instead will accomplish the purpose for which it has been sent. In Psalm 120, the psalmist described God sending his word out to heal and to deliver. This same tradition is reanimated in the gospels, (see Matthew 8:5–13) in the request of the centurion who asks Jesus not to physically go to his house, but instead, to send his word out and heal his servant. In each case, there is a sense of sound that literally travels across space and time with the capacity to remake whatever it encounters. This preoccupation with the power of the word actualizes what Walter Ong fittingly termed “the presence of the word”, the contention that that the sounding word, and not the written word, “is the most productive of understanding and unity, the most personally human, and in this sense closest to the divine.”

30 Smallwood’s “Hebrews 11” exemplifies the sonic intimacy gospel music nourishes between believers and the divine, an affection that refracts back onto sound itself, imbuing this sensuous force with a spiritual presence.

When Smallwood drew an explicit link between his rendering of “Hebrews 11” and the aforementioned verses from the gospels of Mark and Matthew, he brought the words of Jesus to bear on gospel performance writ large. As he accented the power that can be unleashed by speech, he demonstrated a divine sanction for the robustly embodied way gospel congregants engage with songs, sermons, and prayers. In a sense, Smallwood’s exhortation uses passages from Mark and Matthew to teach his listeners that sound’s sacramentality was sanctioned by Jesus. Like the New Testament’s disciples, contemporary believers are to imagine that sound has a material force of great consequence. Of course, there is an important, phenomenal distance between the efficacy of divine speech and musical sound. However, I assert that the patterning of sound into gospel form is inspired by a conviction of the power of the word, even as gospel performance fosters a communal understanding of the word’s power. Like the vamp of Smallwood’s “Hebrews 11”, the gospel tradition is full of songs that endeavor to lend to sacred words a setting fit for the revelation of power. In song, as in speech, vocalization is paramount. It is the articulation of sound—musical and non-musical—that activates the power of the word. However, sound is more than what meets the ear; I agree with Nina Eidsheim that “not only aurality but also tactile, spatial, physical, material, and vibrational sensations are at the core of all music.”

31 In gospel churches, as choirs and ensembles, instrumentalists, and congregations proclaim the word through song, musical sound becomes an enveloping force, an agent of immersion, a sensible indication that “the Lord is in his holy temple.”

Alongside liturgical institutions such as baptism and the Lord’s supper, two widely adopted means of grace, sound serves as a primary conduit through which spiritual sustenance finds its way into the bodies and minds of believers. In this essay, I have argued that the theology that braids musical sound together with the Holy Spirit unfurls a deep sacramentality, a system of belief that inspires the escalating shape of sermons, songs, and prayers—collectively, these media constitute the Black gospel tradition. In the scene from Chicago’s Greater Harvest Missionary Baptist Church, music’s capacity to foment embodied ecstasy illustrated gospel’s power to reveal the sacramentality of sound. As music traveled into the pastor’s spirit, and from the pastor’s gesture into the congregation’s collective consciousness, sound’s kinesthetic force fortified a fleeting connection between worlds, seen and unseen. Smallwood’s “Hebrews 11” clarifies the source of sound’s power. Accenting the enduring force of divine speech, this song shows how beliefs about the power of the word sustain the sense that sound itself is efficacious. As this essay has shown, sound’s invisible materiality makes it an especially useful means of religious encounter. Musical organization systematizes sound’s malleability, turning musical syntax into an extension of the holy. At the intersection of music and divinity, a rhythm can be felt in one’s spirit and a sonority can be termed a Holy Ghost chord. Sound is regarded as sacramental.