Abstract

Georgian polyphonic chant and folk song is beginning to receive scholarly attention outside its homeland, and is a useful case study in several respects. This study focuses on the theological nature of its musical material, examining relevant examples in light of the patristic understanding of hierarchy and prototype and of iconography and liturgy. After brief historical and theological discussions, chant variants and paraliturgical songs from various periods and regions are analysed in depth, using a primarily geometrical approach, describing the iconography and significance of style, musical structure, contrapuntal relationships, melodic figuration, and ornamentation. Aesthetics and compositional processes are discussed, and the theological approach in turn sheds light on questions of historical development. It is demonstrated that Georgian polyphony is a rich repository of theology of the Trinity and the Incarnation, and the article concludes with broad theological reflections on the place of sound as it relates to text, prayer, and tradition over time.

1. Introduction: Theological and Methodological Frameworks

The Georgian Orthodox three-part polyphonic chant has begun to receive greater academic attention outside its homeland, and it provides interesting material for historical and musicological study. It is also an excellent case study for questions about the spirituality of Orthodox chant, its place among the sacred arts and in liturgical space, its relationship to prayer, and its concrete expression of theology. This article will discuss such aspects of Georgian chant by exploring examples1 within theological and iconographic-architectural frameworks, using historical and musicological analysis, contextual information, and patristic writings as tools for study and interpretation. Some of the same chant items will recur throughout the study as we explore the nature and significance of different details. We begin by establishing the frameworks and briefly describing the sources of the tradition, touching upon the difficult issue of dating the appearance of three-part polyphony in Georgia.

Much of the structural and theological discussion of Georgian chant relates to the concepts of hierarchy and prototype. The term hierarchy first occurs in the various works attributed to St. Dionysios the Areopagite, which some scholars attribute to the hand of the Georgian St. Peter the Iberian and which, in any case, have had an important place in Georgian theology, literature, and liturgy (Lourié 2010, 2016).2 The saint defines and describes the phenomenon as follows:

“Hierarchy is, in my judgment, a sacred order and science and operation, assimilated, as far as attainable, to the likeness of God, and conducted to the illuminations granted to it from God, according to capacity, with a view to the Divine imitation. Now the God-becoming Beauty, as simple, as good, as source of initiation, is altogether free from any dissimilarity, and imparts its own proper light to each according to their fitness, and perfects in most Divine initiation, as becomes the undeviating moulding of those who are being initiated harmoniously to itself. The purpose, then, of Hierarchy is the assimilation and union, as far as attainable, with God, having Him Leader of all religious science and operation, by looking unflinchingly to His most Divine comeliness, and copying, as far as possible, and by perfecting its own followers as Divine images, mirrors most luminous and without flaw, receptive of the primal light and the supremely Divine ray, and devoutly filled with the entrusted radiance, and again, spreading this radiance ungrudgingly to those after it, in accordance with the supremely Divine regulations” (Celestial Hierarchy, 3:1).

Hierarchy; therefore, has to do with deification,3 with communication of divinity (Purpura 2017), and in practice, it can be understood as a spiritual pattern that exists at all scales, not unlike a fractal on the physical level (Williams 2010). In his writings, the saint applies hierarchy to the angelic and ecclesiastical orders, but as the definition shows, it includes all beings. He specifies that God is the head of every hierarchy, thereby clarifying that hierarchies do not simply connect to one another in succession; each one exhibits “clinging love toward God” and has its source in Christ and its goal as union with the Trinity (Ecclesiastical Hierarchy, 1:3). Furthermore, hierarchies encompass all deifying activities. In the Ecclesiastical Hierarchy, the Areopagite continues his definition, stating that “every hierarchy, then, is a whole account of the sacred things falling under it, a complete summary of the sacred rites of this or that hierarchy” (Ecclesiastical Hierarchy, 1:3), and though he does not comment on music but only on liturgical texts, chant is a part of such rites, along with architecture, iconography, vestments, vessels, and any relevant object or action. I suggest that there are also further hierarchies that relate to lay piety and folk practices and hymns, such as the Svan examples that we will later explore. The ecclesiastical hierarchy includes a “multitude of divisible symbols”, and each hierarchy is “a kind of symbol adapted to our condition” (Ecclesiastical Hierarchy, 1:5), encompassing various needs and contexts. Human beings work to incorporate other created things through proper use and co-operation, as St. Maximus the Confessor describes in one of his texts on love (Berthold 1985, p. 38), and sacred art is a primary outcome. It is; therefore, important to keep in mind that hierarchy has to do with liturgical elements at least as much as with those who carry out the services. While the Celestial Hierarchy primarily describes hierarchical members, their work and relationships, the Ecclesiastical Hierarchy, while giving some explanations of the relevant hierarchs, focuses on liturgical commentary. Some attention has been given to this topic in architecture (Bogdanović 2011), iconography (Ivanovic 2011), and Byzantine art and ceremony in general (Woodfin 2010), but comparatively little practical discussion of the Areopagitic corpus has taken place, perhaps because of the many differing philosophical considerations, interpretations, modes of reception, and attitudes towards it (Ivanovic 2011). However, given the definition of hierarchy, its explanation as “the source of the order of sacred things” by St. John of Scythopolis (Rorem and Lamoreaux 1998, p. 145), and its further interpretation as a particular pattern type, Georgian chant calls for its application. It applies in two primary complementary ways: The tripartite structure of voices, styles, compositional process, and related aspects; and the specific hierarchical relationship among the voices, in which the middle and lowest reflect, follow, and translate the top-voice model melody in many ways. As St. Ekvtime the Confessor (1865–1944) states, “The mode [i.e., with model melody for any given mode] is the foundation of chanting[;] on the essence of its tune depend the movements of all the voices. Losing the mode is equal to losing the chant” (Sukhiashvili 2014a, p. 421). Yet, in religious folk songs, the middle voice often leads, and different types of compositions can shed light on particular hierarchies or powers within them. Other hierarchies (e.g., sections of a song or the relationship of dance, tune, and text) occur in this repertoire, which we will discuss near the end of this article.

Unlike hierarchy, the term prototype, also rendered archetype, does not generally occur in patristic works along with deliberate definitions, but its meaning is critical in discourses on icons and clear in context. In a treatise by St. John of Damascus, he describes different kinds of images and explains that an “image is not like archetype in every way” (Louth 2007, p. 25). Further on, he quotes St. Basil the Great, stating that the veneration bestowed upon an image passes to its prototype, that is, to the very person who is depicted; it likewise passes from saints and angels to God (Louth 2007, p. 35). Prototype also has a practical meaning, referring to physical icons and their canonical principles, from which other icons are copied and inspired, yet the analogical, theological sense, in which an icon is a “true likeness” by expressing “the sanctity and glory of the prototype”, rather than its outward form, is most relevant (Kenna 1985, p. 345). The outward form of an icon can be studied; however, in order to discern aspects that co-operate in the analogy, in the sanctity and glory. In chant, it is somewhat difficult to apply the term in the literal way, since there is no musical equivalent to an icon “not-made-by-hands” (Moody 2016, p. 53), but the study of a specific repertory can bring to light its own means of expression, both musical and theological (Moody 2015). As we will see, within the given tradition, prototype applies in practice to model melodies and evident musical principles. Theologically, it shows how liturgical song comprises incarnate prayer and worship carried out by human beings, no matter the language or musical tradition, and relates to that uttered by those who hierarchically precede them, that is, angels. Prototype also relates to hierarchy, and all copies of prototypes and all hierarchies come from, and lead back to, the Divine archetype according to St. Dionysios (Ecclesiastical Hierarchy, 1:1; Celestial Hierarchy, 2:4). He states that Jesus Christ is the “Source and Essence, and most supremely Divine Power of every Hierarchy”, and that in hierarchy, He “folds together our many diversities” (Ecclesiastical Hierarchy, 1:1). We will analyze the unfolding and folding of sound in Georgian chant, revealing prototypical structures, elements, and their significance. Like the complex surfaces of icons and textiles, chant can be characterized by the aesthetic term poikilia (Pentcheva 2010, p. 140), often translated as “variegation”, which we will describe in more detail in the discussion of ornamented examples. While the term relates to visual surfaces, it was nevertheless applied to music and poetry, though most scholarly discussions of such examples relate to the Classical period (LeVen 2013).

A third concept that underlies the entire interpretive framework in this study is that of the logoi of things. The logos of something is its reason for existence, God’s will for it, what it can communicate from God to human beings, and its “point of contact with the Godhead” (Lossky 1997, p. 98). St. Maximos the Confessor (d. 662), who commented on the Dionysian writings, who was exiled and buried in western Georgia,4 and whose writings played an important role in Georgian culture and theology (Mgaloblishvili and Khoperia 2009), is one of the foremost expounders on the logoi in creation. Symbolism and mystagogical interpretations, such as those that we will quote below from various Church Fathers, relate to contemplation of the logoi, and the connection of subsequent musical analyses to theological frameworks and interpretations also depends on this view of reality. Another underlying concept is that of exegesis, which refers to chanters’ interpretations of musical content, not unlike varied scriptural commentaries. The term is notably used in Byzantine chant (Lingas 2004; Touliatos 1989), but it can apply to any tradition. The concept is important since it allows for changes in speed, style, and other characteristics, is the basis for ornamented and melismatic repertoire, and lies behind the idea of a stable tradition with many embodiments. Thus, chanters feel that they sing “the same chants”, as we will see below, and such does not entail literal congruence in every detail. The belief in an unchanged tradition, then, is not a legendary idea, as such does not denote the sense that chanters across time and space sing the very same material in the very same manner. Hierarchy and prototype tie into this point, since choices based on knowledge and experience of principles lead the process, rather than any particular rendering. The topic of incongruity or disagreement about what may be a valid exegesis will be addressed through examples in several sections of this paper, and we will discover that this aspect has an interesting, even positive, place within the Dionysian framework.

A final methodological note is that it is useful to read sonic expressions in some ways as we would tangible ones, such as Georgian inscriptions, whose specific sizes, formats, self-references, and included crosses mark their prayerful function. The art historian Antony Eastmond considers them to be “textual icons, and states that “their overall form carries the same visual power and figural correspondence as icons in the Orthodox world. The blocks of text acted as mnemonic devices to imprint an icon of prayer on the mind of the viewer” (Eastmond 2015, p. 79). They hold “the same theological value as images, serving as representations of truth with access to the divine” (Eastmond 2015, p. 96). Sung and spoken texts, like their inscribed counterparts, can be similarly described as icons, and our analyses will specify recognizable forms and features that strike the ear as tangible expressions strike the eye and hand. This point has theological implications as well, since matter is as much a key component of making and hearing sound as of the production and reception of material objects. In order to create chant, solid, functional, resonating human bodies—not only brains, voices, mouths, and ears—and air, in which sound waves are formed, are necessary. St. Dionysios writes that, even through the lowest forms of matter, one can be “led to the immaterial archetypes” (Celestial Hierarchy, 2:4). This idea has to do with symbolism as it relates to God and the celestial hierarchy, and it can apply to expressive media and objects themselves and not simply to figures of speech. We will now consider the material sources and history of Georgian chant, including theological information from a medieval Georgian author. His thoughts will begin to fill in the framework just described while also aiding our understanding of historical development.

2. Embodied Tradition: Historical and Theological Sources and the Development of Georgian Ecclesiastical Polyphony

Besides later transcriptions and audio recordings, the historical record of Georgian chant is sparse in musical sources. Only six medieval neumed sources survive, all from the tenth century, and all other manuscripts contain only text and modal designations. Notation does not appear again until the eighteenth century (Oniani 2013). The neumatic systems that occur on both sides of the notation gap, through the twentieth century, are ekphonetic. Later neumes are idiomatic to each source (Graham 2008), but all tenth-century manuscripts employ the same notation. Oral transmission continued even after transcription into staff notation began in the nineteenth century, an effort that was led by several Georgian transcribers and master chanters after annexation by Russia and through the Soviet period (Graham 2007). Staff notation is now used, but like other repertories that include written notation, such as Byzantine chant (Khalil 2009), Georgian polyphony continues to have orally-transmitted components (Graham 2008). We will especially look at oral variation in the discussion of paraliturgical repertoire. While Georgian scholars have further analyzed neumatic notation types, Western scholars have not generally sought any connection between late and early Georgian sources, though sometimes between early Georgian and contemporaneous chant from elsewhere (Jeffery 1992). However, comparison of Georgian sources leads to interesting questions and conclusions about polyphony and the nature of oral tradition. Analysis of chant examples with the most variants and widest documentation reveals the structure and development of the tradition and provides rich material for theological explication. It is possible to ascertain certain points about the development of these examples and what they, and thereby Georgian chant in general, may have been like at least as early as the twelfth century, by reading primary sources concerning musical structure and professional activity; examining modal designations, notation, and text in manuscripts and printed sources; and considering audio recordings and the process of oral tradition, exploring the complex ways in which it relates to the extant neumes from all periods. The notation gap and different combinations of musical source types—neumes, texts, transcriptions, and audio recordings—at different periods presents a complicated situation, but we also need to look outside the sources in question. Other primary information can then guide interpretation of musical specimens. Subsequent theological interpretations do not depend on questions of history, but we will see that they in turn have historical importance, helping to date three-part polyphony in the Georgian context.

Let us begin with the neumatic sources. Ekphonetic notation types feature two lines of neumes, one below and one above the text. Scholars debate whether or not the tenth-century neumes represent polyphony, but those on the other side of the gap correspond to three-part singing. One recently-discovered twentieth-century example, which has a corresponding recording, appears to outline the middle and bottom voices of a Trisagion variant.5 In his recent work, the mathematician and chanter Zaal Tsereteli has compared the structures of heirmoi in tenth-century sources with those of nineteenth-century transcriptions. Previously, he proposed that there was no relation between these sources, but through statistical analysis he found a clear correspondence of phrase and structure (Tsereteli 2012). Georgian chants are based on genre-specific, top-voice model melodies for each of the eight modes, which are harmonized differently in each chant school and, as we shall see in later analyses, by individual chanters, and these are reflected in sources on both sides of the notation gap. We will look at the theology of this model-based, three-voiced form below. The Old Georgian term for harmony, “mortuleba”, is polysemantic, and the chanter and musicologist Magda Sukhiashvili considers its appearances in tenth-century sources to refer to polyphonic rendering of chant (Sukhiashvili 2015). Whether harmonization of any kind is as early as these sources or even earlier will be discussed later, and at this point, one may surmise that polyphony, considered in the global context of Christian chant traditions, could have developed in Georgia at least as early as in Western Europe (Shugliashvili 2013).

There are various explanations for the dearth of notated sources between the tenth and eighteenth-centuries, such as the havoc of successive invasions and political upheavals. However, many liturgical books survive, especially in Georgian monastic centers outside the country, such as Mt. Sinai and Jerusalem. It may be that notation declined as polyphony developed, or was perhaps implemented in order to facilitate its beginnings, but it seems that oral tradition took precedence at all stages, as shown by scribal notes and hagiography. For example, in the margin of an eleventh-century menaion, the chanter and translator St. Giorgi the Athonite states that the theotokia are not included in full because “By God’s grace we [Georgians] know them by heart”, while Greek books give the full text, which would be intoned by a canonarch (Sukhiashvili 2014b, p. 435). This comment is one of many references to memory and orality. Earlier hagiographic accounts, such as that of St. Grigol Khandzteli (759–861), describe their subjects as knowing “the [canons] of all the feasts very well” (Sukhiashvili 2014b, p. 435). These descriptions are not literary exaggerations and align with well-documented nineteenth and twentieth-century chanters (Graham 2008). Thus, oral transmission and preservation, and reliance on the same over written sources, was prevalent even for text. We may infer that such was the case regarding musical material as well, and the ekphonetic nature of all notated sources before the transcription movement, and of idiomatic neumes through the twentieth century, indicates this situation across ten centuries. Concerning the lack of notated manuscripts, then, it may be that notation was not widely used, as is the case in other Eastern traditions, such as Ethiopian chant (Shelemay et al. 1993).

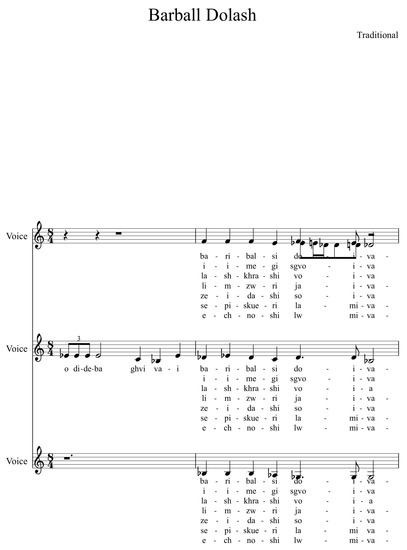

Regarding both practical and theological matters in Georgian chant, let us consider a passage from the preface to the translation of the Psalter by the twelfth-century Gelati Monastery theologian Ioane Petritsi.6 His oft-quoted reference to three parts in music, names included, has nevertheless been interpreted by some scholars as referring to parts of a range rather than to voices in polyphony. The passage is part of an exposition of Trinitarian theology, based on mystagogy of the liberal arts, which somewhat echoes certain ideas in Clement of Alexandria’s Miscellanies (Book I, Chapter XIII), but is far more specific in its purpose and in the various phenomena that it describes. This musical mystagogy appears after explications of arithmetic and of the three geometric principles of point, line and plane.

“Now, what about music? Is not, actually, our beloved book [the Psalter] altogether a music embellished by the Holy Spirit?! And any music requires three tunes or phthongs from which any wholeness is composed. They are called mzakhr [strained, high pitch], jir [middle], and bam [lower tension, bass], and, verily, all attunements of strings and voices make a pleasant melody through those three, because the beauty of any ornament derives from the irregularity of its adornments. The same is perceived in the number of the transcendentally Holy Trinity, for we say the ‘birthlessness’ of the Father, the birth of the Son, the [procession] of the transcendent Holy Spirit, and the unity of the Nature with differentiation of the Hypostases. Similarly, in the musical differentiation of mzakr, jir, and bam you will perceive a unity of composition. In fact, through the paradigmatic images, posited in His First Intellect, God has adorned and musically composed the order of the whole creation and has imposed ideas even on the prime matter looking to [introduce] a diversity even in the oneness of matter. Eventually, during wars and battles the best strategists used to arrange their armies in the shape of a triangle, deeming this shape invincible. In fact, wherever the power of seven is the third corresponding image (or: icon) of the first three. Why? Because, the first odd number is three, the second five and the third the renowned seven, which neither gives birth nor is born, for which reason, according to the teaching of the Italians, it was considered as the virgin [number] and was worshiped as such by them” (Gigineishvili 2014, pp. 221–22).

Readers may ask why Petritsi includes geometric and numeric figures since these aspects were already expounded. Analogy links the perhaps seemingly disparate illustrations, and such is especially so regarding the triangle. As the musicologist Nino Pirtskhalava also notes, he associates the three-voice structure with this shape, hence why the linear sense of range is not intended (Pirtskhelava 2014, p. 485).7 In addition, the voices are also called “tunes”, indicating that they could be sung independently, though the three together form a whole. Elsewhere, Petritsi mentions “simultaneously-sounding pitches”, and he employs much polysemantic harmonic language in his works, sometimes using the term in the horizontal or general Greek sense and sometimes in the vertical sense, calling for close, contextual readings. Thus, notwithstanding the practical relation of ideas in this passage, its theological purpose primarily reveals the musical phenomenon to which the author refers. The Trinity underlies all his “theories”, as he calls them, and a three-part polyphonic structure serves as sonic iconography, while a range of notes, sounded in horizontal patterns across time, does not. Following Petritsi’s order, the top voice is like the Father, bearing the model melody, from which the equally or sometimes more active middle voice, like the incarnate Son, is begotten and the co-operative, grounding bottom voice, like the Holy Spirit, proceeds. The middle voice often has a leading role, especially in paraliturgical song, and St. Dionysios ascribes an important mediating power to the middle member of a hierarchy (Celestial Hierarchy, 9:2). Along with this Trinitarian discussion, Petritsi’s geometrical analogies of the triangle and of point–line–surface figural construction are useful for musical analysis and for a theological understanding of sacred art and one’s prayerful engagement with it (Freedman 2019). Petritsi’s contemporaries would have shared the precise musical and iconographic experiences that correspond to his contemplations, and texts, icons, church buildings, and, as we are describing, at least general musical models, structure, and sensibilities have been carried forward from his time. If a three-voiced basis for musical knowledge was as commonplace as a triangle, polyphony was likely in practice for some time before Ioane Petritsi’s twelfth-century theological exegesis. We will return to this point and see that monophony is not necessarily an older phenomenon or predecessor to polyphony in Georgian contexts and from a global perspective, and it is important to note how the theological purpose of the passage helps to clarify the music that it describes.

Nineteenth and twentieth-century sources, such as transcribers’ notes and interviews, give further practical information, describing the oral transmission process and providing points on musical structure and history (Sukhiashvili 2014b). Chanters described a five-year curriculum: students began with “study voices”, singing in parallel fifths and octaves in order to sharpen the polyphonic paradigm, and then learned the three chant styles, called “modes” in English, not to be confused with the modes of the oktoechos, which are called “voices” in Georgian.8 First came what were considered the oldest and structurally essential chants: the plain mode variants. It is important to note that such entails model melodies and relatively simple contrapuntal style but can differ in harmonization and figuration (Graham 2012), as we will see in our examples. It may also be helpful to consider the three styles as existing on a continuum rather than as three separate entities, and chanters’ aesthetic choices affect the quantity, extent, and type of decoration in any rendering in any mode. After becoming proficient in all three voices, students could add and adjust the other parts after learning the top voice of new chants. They then learned the other two styles, the true and ornamented modes. Ornamented versions have striking features respective to Eastern and Western schools, such as a highly-ornamented, active middle voice, passing between chords, in the former and voice-crossing (called “going across the cross”) and diversion from model melodies (Graham 2013), with additional vowels, often over long melismas, in the latter. In simple variants, harmonization and bottom voice gestures differ, but as John Graham notes, shared features, such as model phrases, three-part structure, and cadence types point to the singing of developed polyphonic chant throughout Georgia before the 1220 Mongol invasion and subsequent separation (Graham 2016). Regional folk styles share features with the geographically-associated chant schools (Tsitsishvili 2010, pp. 295–97), and especially in the ornamented mode, improvisation is of great importance, especially in the Gelati and Shemokmedi traditions, and depends on chanters’ practical, not theoretical—and there are no extant Georgian music theory treatises—understanding of musical structures, principles, and rules. As the master chanter Artemi Erkomaishvili, whose style we will explore, described it, one “hears the end of the [chant] in advance, and if the goal is seen, it is not difficult to achieve it; whichever way you take and how many turns you may take up and down, you are sure to get there… However, the voices may be twisted, we know where to get, but it is impossible to twist the voices in one and the same manner twice” (Sukhiashvili 2014b, pp. 436–37). John Graham describes how chanters use cadence pitches, textual rhythm, and most interesting for this study, what we will call reflections and translations of model phrases, that is, inversions and the singing of the same melodic patterns in a different range, to guide their improvisations (Graham 2013). Yet, these examples do not demonstrate the height of decoration that historically existed. A further method of ornamentation, of which we have no extant examples, was the addition of up to three more voices to the foundational three-part structure, each part with its particular name and characteristics (Shugliashvili 2013). Several scholars have noted that ornamented variants are akin, not historically or directly, but as a musical phenomenon, to late Byzantine kalophonic chant (Shugliashvili 2010), yet an important difference is that, rather than being entirely new compositions, they still follow the “traces”, to use St. Ekvtime’s term, of the model melodies (i.e., their formulae and contour) (Sukhiashvili 2014b, pp. 447–48). This importance of model melodies is indicative of the mechanism of orality over notation in the development of the tradition. It is likely, then, that the co-existent variants and the oral pedagogical process reflect the historical development of Georgian chant, beginning with the plain mode versions or perhaps the study voices. Three-part polyphony is the prototypical, foundational, hierarchical pattern, with the top voice having structural but not chronological importance for chanters. It begets and sends forth the other two voices, not existing before or without them; there is no monophonic stage in the curriculum. The ekphonetic neumes of later sources were used by chanters working with this knowledge and background, and the tenth-century neumes could have been read in a similar cognitive and perceptive context; diachronic graphical comparisons of neume types could shed much light on this situation. I suggest that, while allowing for great variation and development, three-part structure gave triangular strength and stability to oral tradition across the centuries, depending on at least three singers’ memories and successful combinations of voices. Even when transcriptions emerged as a preservation measure, their very proponents nevertheless noted the necessity of oral transmission. Scores were understood as means to support and revitalize such learning but not to replace it. It was noted that chants sounded “out of tune” when choirs without the aural background sang from transcriptions (Graham 2007, p. 103). Yet, some kind of shared, somewhat precise, even if not entirely accurate, notation was needed in order to prevent the utter loss of repertoire under oppression and to make it possible for long-term preservation to occur when oral transmission was hampered. After yet further oppression in the Soviet period, the continued synergy of oral tradition and written score has been taking place since at least the late 1980’s. Thus, embodied polyphony has been a primary technology of preservation as well as an enduring pattern over time and across sacred and secular music. We will briefly consider similar patterns in other forms of sacred art and discuss the chant-related linguistic and artistic inculturation process of Christianity in Georgia before examining specific musical examples.

3. Inculturation and Aesthetics in Chant, Architecture, and Iconography: Contextualizing Sacred Polyphony Amidst Language, Space, and Material Culture

Archaeological traces of Christianity are evident in Samtavro and other parts of eastern Georgia from the second century onwards (Licheli 1998; Mgaloblishvili 1998), and it became the state religion of Eastern Georgia, that is, the kingdom of Iberia, in the first quarter of the fourth century. The religion also became widespread in the kingdom of Egrisi in Western Georgia, which had continuous cultural exchange with the Hellenistic world from the classical (Giorgadze and Inaishvili 2016; Tsetskhladze 1992) through Byzantine periods,9 and it is interesting that archaeological remains, churches, attributed apostolic burial sites, hagiographic summaries (Vinogradov 2017), and folk stories of specific apostolic episodes survive together (Makharadze and Ghambashidze 2014). The general Eastern Christian approach of inculturation, as opposed to acculturation, took place in Georgia (Doborjginidze 2014, p. 329), and while elements from surrounding cultures are present, local art, vernacular texts, and specific practices developed (Eastmond 2015; Schrade 2001). While it is sometimes difficult to ascertain whether a given element is Georgian, especially apart from language, since many cultural, literary, and practical elements are shared or follow indirect paths,10 specific characteristics of Georgian Christian expression are identifiable. It is understood that music was also an integral, though less easily documentable, part of the same process. Studying the linguistic, artistic, and even topographical inculturation process can help to contextualize, interpret, and understand associated chant material.

The linguistic inculturation process can be divided into two major stages: a “functional”, linguistically-legitimizing phase of initial assimilation and translation, ending in the tenth century, and a “qualitative” period of incorporating further knowledge, Byzantine influence, and precise use of language, characterized by the translation of many new works and retranslation of others, ending in the twelfth century (Doborjginidze 2014, p. 331). Ioane Petritsi’s work belongs to this second stage. The earliest Georgian liturgical books contain the Jerusalem rite, some containing notes about its use and translation by such figures as Ivane Zosime and Giorgi the Athonite, and such chant books are our only extensive hymnographic sources for Jerusalem liturgy in any language (Frøyshov 2008; Jeffery 1992). Two manuscripts of the iadgari (i.e., the Georgian Jerusalem hymnographic collection) are neumed, and Georgian churches kept contact with Jerusalem and followed the Palestinian typikon of the Byzantine rite (Mgaloblishvili 2014). The liturgical scholar Symeon Froyshov describes complementary ways of dividing the phases of liturgical inculturation, such as the multi-stage development of the Georgian recension of the Jerusalem rite through its final Byzantine form (Frøyshov 2008, pp. 264–67). Some texts underwent several shifts, such as the paschal canon, whose final form, reached by the twelfth century, was its fourth extant translation, two of which had been made before the tenth century (Frøyshov 2008, p. 240). Some early Jerusalem hymns nevertheless remain in the Byzantine rite and were not given new translations. While translations were being made, primarily from Greek, original hymnography was also composed, such as hymns by the aforementioned St. Grigol Khandzteli (ninth century); Mikaeli Modrekili’s iambic compositions and much other indigenous hymnography (tenth century) (Frøyshov 2008, p. 261); St. King Demet’re’s paraliturgical hymn to the Theotokos, displaying a particular poetic form (twelfth century), sung today according to at least five regional variants, one of which was recently documented (Kalandadze-Makharadze 2014);11 and octosyllabic redactions of hagiographical accounts (Pataridze 2013, p. 62). Two important forms of Georgian poetry, known as high and low verse, are octosyllabic, and further study of indigenous liturgical compositions, in comparison with Greek, Latin, Syriac, Ethiopian, and other literature, could lead to a greater understanding and discernment of specific cultural elements. Otherwise, such may not be noticed, or a common feature may be referred to as “Georgian.” Froyshov discusses the question of indigenous elements in the Jerusalem rite manuscripts, highlighting original hymnography, pointing out elements that may have come from Syriac sources, and discussing common language concerning the Incarnation, which some scholars had previously attributed to one language or another (Frøyshov 2008, pp. 261–64). Georgian musical features are recognizable today, as are architectural and iconographic ones, some of which also have practical or symbolic roots in Jerusalem.

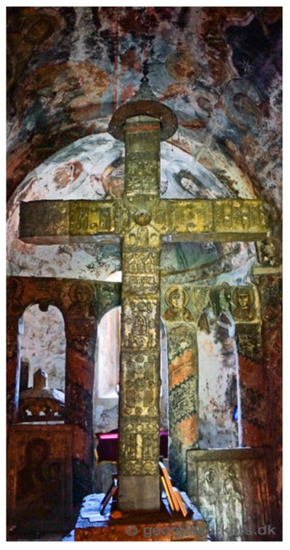

Jerusalem had an important place in Georgian Christian development in several aspects along with liturgical development. While the old capital, Mtskheta, became a New Jerusalem, with representative sacred sites, especially corresponding to the Holy Sepulchre and Golgotha (Mgaloblishvili 2014), such sites occur elsewhere, for instance, Imereti, and a monastic cell type, a tower containing an upper chapel and a lower cell, reflects the same symbolic geography (Gagoshidze 2015). The same hierotopy, that is, hierarchical pattern of sacred space (Lidov 2010), occurs on increasingly smaller scales, by southern church entrances marked by standing stone crosses, which also copy what was literally at the Jerusalem site according to Egeria’s fourth-century account, (Chichinadze 2014) and again inside churches, by altars and uniquely-Georgian pre-altar crosses (Gagoshidze 2014). Forms of the cross in these sites and contexts, often featuring triangular decoration and atop three-stepped pedestals (Figure 1), simultaneously symbolize the life-giving pillar from the tree in Mtskheta, the cross at Golgotha in Jerusalem, the true cross (pre-altar crosses sometimes containing relics of the same), and the cross opening the gate of Paradise (Gagoshidze 2015). Especially in pre-altar crosses, their unique structure, patterns, and decorations bear interesting reflections of musical traditions, including a Trinitarian structure, variations specific to regions or workshops, and aesthetic and geometric parallels. Though there is not space to discuss these features here across media, I have described some examples elsewhere (Freedman 2019), and we will analyze some of the relevant features in chant examples from the underlying structural and theological point of view. Three-part polyphony exists within this material and aesthetic milieu and contains its own Georgian elements, echoes of Jerusalem practice, and through cross-domain mapping, patterns, structures, and decorative trends found in material culture,12 a point that may be overlooked if chant texts alone are over-emphasized.

Figure 1.

Pre-altar Cross; photograph taken by Norma Mikeladze-Andersen; http://www.georgiske-kors.dk.

In order to further explore historical development, let us briefly consider contemporary variants of Jerusalem repertoire along with preceding historical documentation. The troparion of the Cross, though designated mode II in other Byzantine rite sources, follows the mode VI (plagal II) model melody in Georgian variants. Though assigned to mode II in the Jerusalem lectionary, it is plagal in tenth-century iadgari manuscripts. While there is an early Byzantine modal area that encompasses features of modes II, plagal II, and IV (Dubowchik 1996, p. 119), the Georgian system of model melodies for each mode suggests that this change may relate to Georgian musical development or categorization. While modal designations and gestures in monophonic repertoires are somewhat fluid, especially among medial modes or between authentic and plagal counterparts (Moran 2010), some melodies also possibly pre-dating modal codification (Jeffery 1992), the situation in Georgian chant is somewhat different since, with scale and range remaining consistent, each mode has one general melody for troparia and one for heirmoi; other chant types follow similar formulas in the respective mode, and others, such as the Trisagion and cherubic hymn, have their own dedicated melodies. The modal change of St. Andrew of Crete’s great canon, from mode VI to mode IV, took place in the eleventh century, coinciding with a new translation by St. Giorgi the Athonite, and it was translated again in the twelfth century by St. Arsen (Managadze 2006, p. 410). Today, its heirmoi have the mode VI model melody, but the “Have mercy on me, O God; have mercy on me” refrain sung between the troparia of each ode follows a mode IV formula. The decision to change the mode as part of the effort towards better translations may likewise stem from Georgian musical sensibilities and available material at any particular period, given the use of pre-existing heirmos translations by St. Giorgi, as the musicologist Khatuna Managadze notes (Managadze 2006, p. 410). By the twelfth century, such may relate to text setting and model melodies, especially since lexical, though not metrical, aspects of translation became quite Hellenophilic in the high Middle Ages (Doborjginidze 2014, p. 337).

This study will not analyze chants whose mode has changed, but it is important to note this phenomenon in conjunction with model melodies in Georgian chant development. Later, we will discuss the mode VI troparion model melody as it occurs in practice, but now let us consider late redactions of two Jerusalem chants.

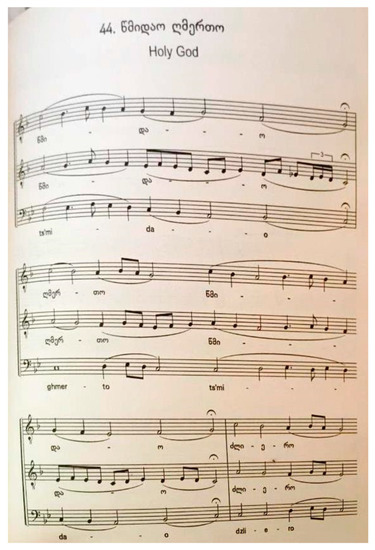

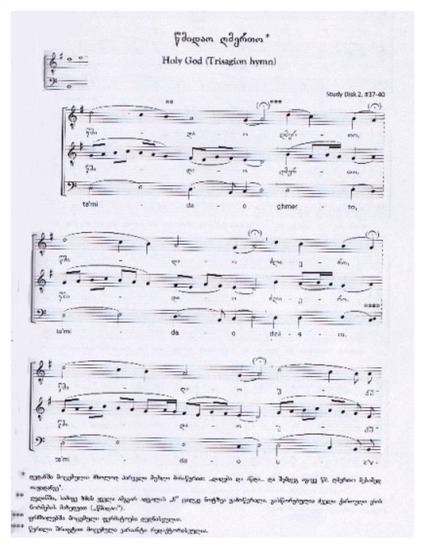

Though no medieval neumes survive for these, our examples are the paschal troparion13 (plagal I in Byzantine rite sources but no designation in the early Georgian lectionaries) and the Trisagion for the departed, also sung at Great Saturday matins and listed there in the lectionaries (not assigned to a mode) (Tarchnischvili 1959, p. 205). Variants from Svaneti (and for the troparion, also Lechkhumi, Samegrelo, and Rach’a) exist, adding to the number of regional, and sometimes family or personal, chant styles for comparison.

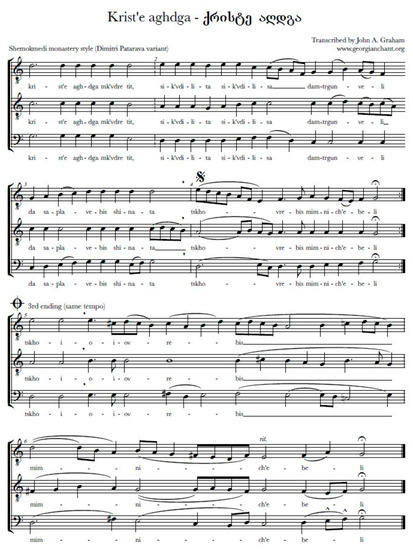

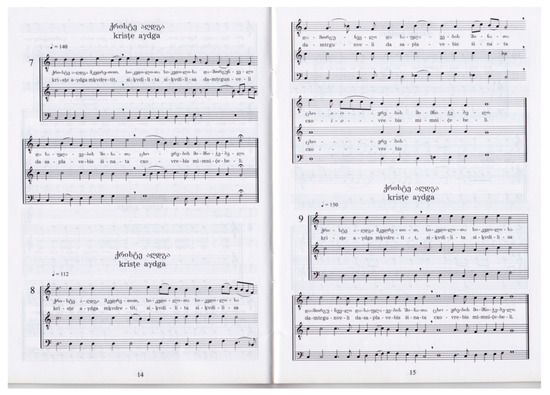

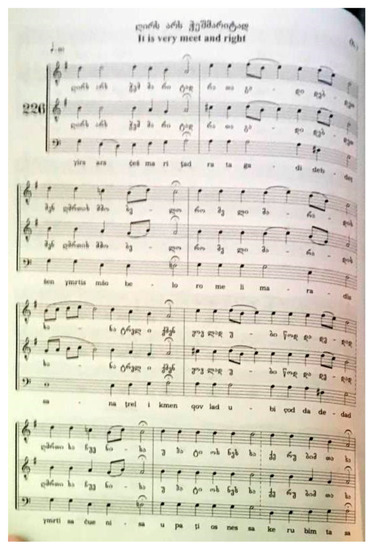

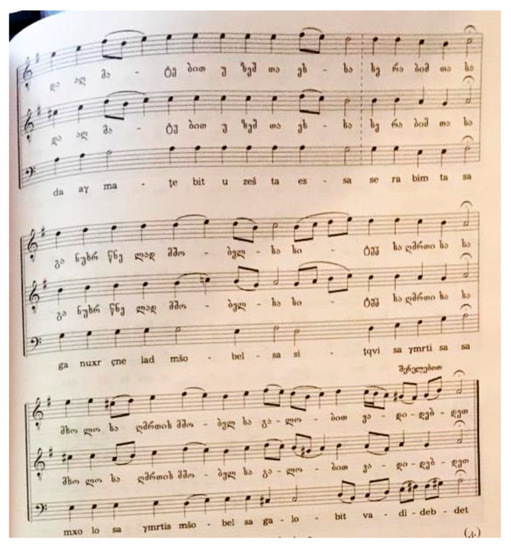

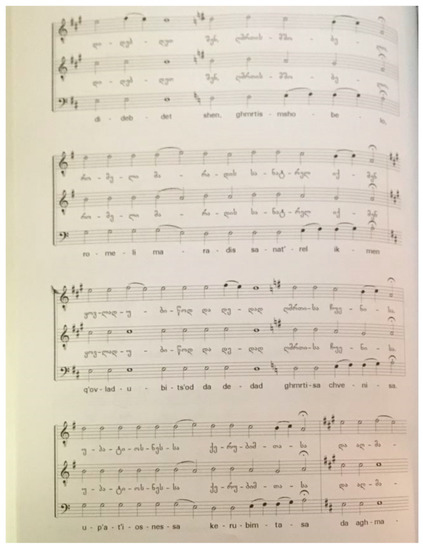

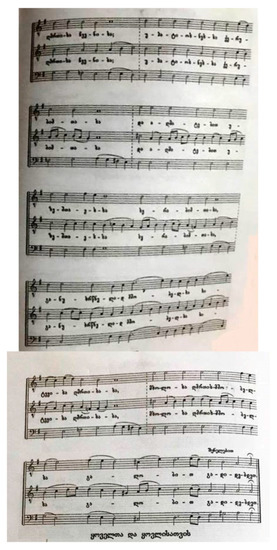

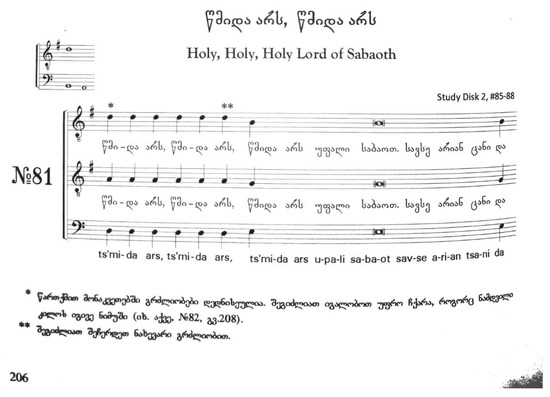

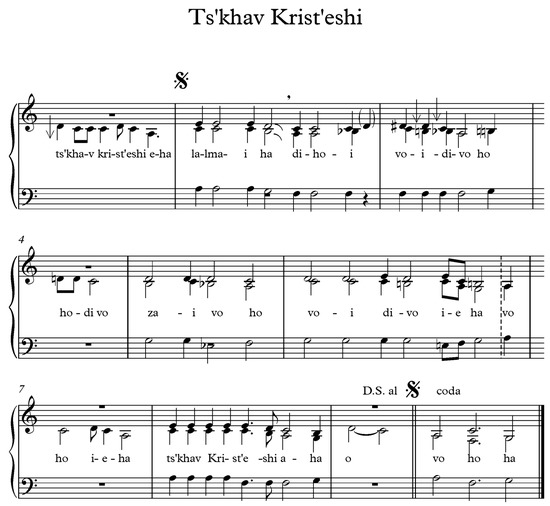

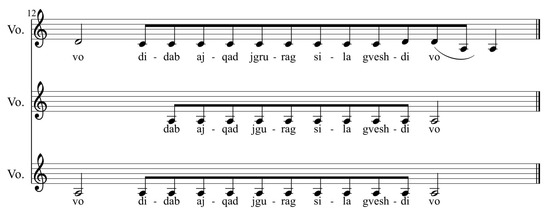

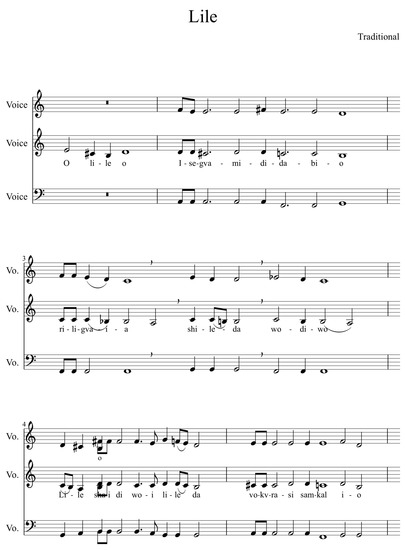

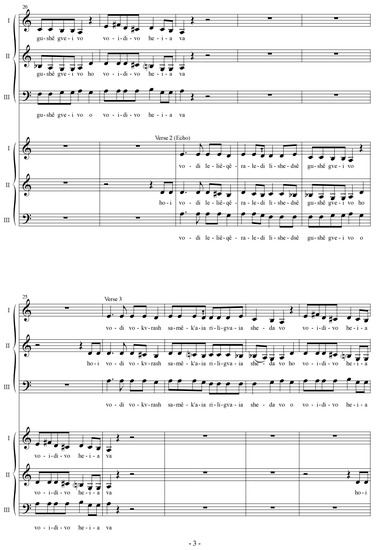

Six variants of the paschal troparion, representing different regions and degrees of ornamentation, are shown (Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5).14

Figure 2.

Paschal Troparion; Svetitskhoveli School.

Figure 3.

Paschal troparion; Gelati School.

Figure 4.

Paschal troparion; Shemokmedi School.

Figure 5.

Paschal Troparion; Svan variant.

The phrase division is the same in all despite the perhaps textually odd separation before, and beginning the next phrase with, the verb. The syllabic setting, often precise textual rhythm, is synchronous, except for expanded, decorated West Georgian endings. Plain mode variants have long notes at places that afford such expansion and decoration. The top voice model structure, which has an ABa′b′ form, is evident, remaining even when voice crossing occurs, passing between the top two voices. Varied harmonization and ornaments; however, often render different structures. The middle voice is also of interest, particularly in Western plain mode versions. Contour and direction are similar, despite the characteristic solo call gesture in the Svan setting. The middle voice has a leading function in Svan song, and this way of building polyphony exists in counterpoint to the top voice-based structure described above; yet, even in that context, the middle voice stands out, for instance by receiving the greatest ornamentation in chants from Kartli-K’akheti. The voice with striking or foundational features, then, may differ and such does not coincide with chronological precedence. Each voice is fundamental in particular ways. Interestingly, in Svan folk song, when monophonic variants occur, they are derived from polyphonic ones (Khardziani 2010), and it seems that this process of shedding voices has taken place on a larger scale in Meskhian (Samsonadze 2012) and Pshav-Khevsurian15 ritual song.

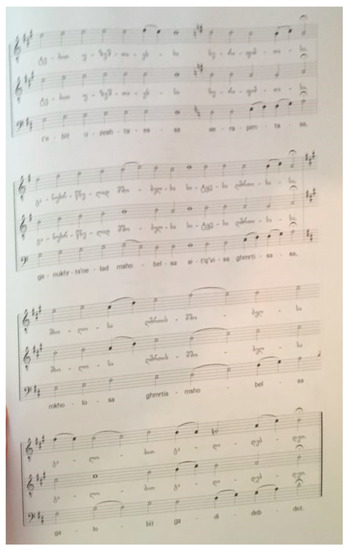

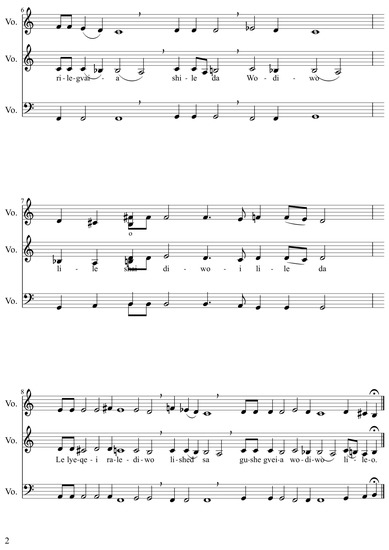

To aid further interpretations from this brief analysis, let us examine the Svan troparion and Trisagion variants (Figure 6 and Figure 7) in their local context.

Figure 6.

Funeral Trisagion; ornamented mode; Upper Svan variant.

Figure 7.

Trisagion; plain mode; Upper Svan variant, Lakhushdi Village.

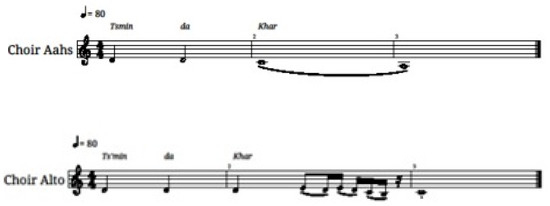

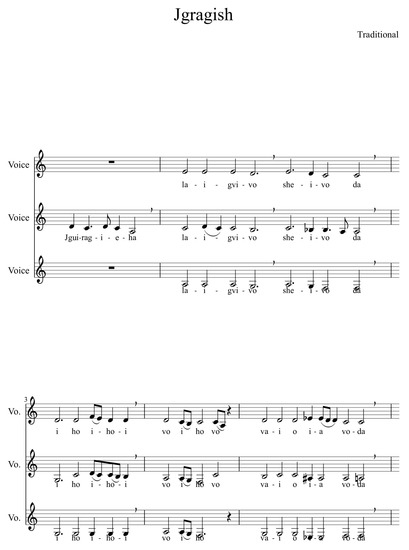

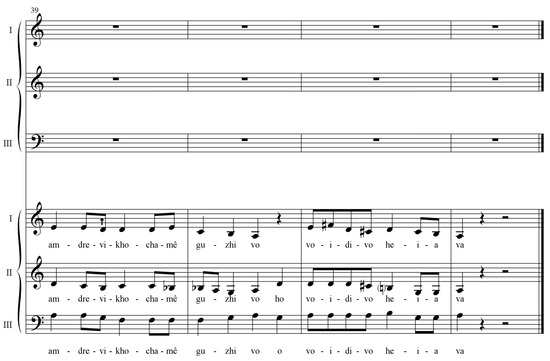

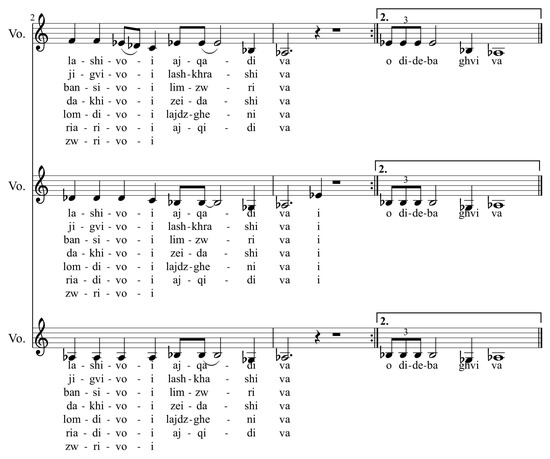

These are two of only four ecclesiastical texts with Svan variants, accompanied by occurrences of Svanified “Kyrie eleison” in folk hymns and one setting of a triple “Lord, Have Mercy” for the departed (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Triple Lord, Have Mercy; plain mode; Upper Svan variant, Lakhushdi Village.

Along with these chants, ritual round dances, folk hymns (some associated with specific medieval church buildings or villages), funeral songs, and prayers are sung to the present day; we will discuss some examples later. All exhibit three-part polyphony, and even extemporaneous spoken prayer is simultaneously uttered by three men (field notes, 25 July 2011; 28 August 2016; 24 July 2017). Some singers consider this paraliturgical repertoire to have pre-Christian origins, though they also deem it a part of their Christian faith and worship (field notes, 22 July 2011). Local veneration of Christ, the Theotokos, the Archangels, and various saints has its associated songs, high medieval churches, adorned icons, rituals, and manuscripts (field notes; Schrade 2001). The recently studied Kurashi Gospel contains the earliest known Svan specimens (this endangered Kartvelian language is primarily oral) in marginal notes, which include prayers written by fourteenth-eighteenth-century hands (Gippert 2013). Several, such as a fifteenth-century prayer, reflect the character of folk hymns in their ornamentation with vocables, primarily to extend vocatives, including those in the Trisagion and Kyrie Eleison (Gippert 2013, p. 100). A vocative “O Christ” occurs at the beginning of prayers for blessing (Gippert 2013, pp. 95–97) and even at the start of a note that does not seem to have sacred content (Gippert 2013, p. 98), and this same calling upon the Lord is a common opening element in inscriptions on icons (Chichinadze 2008) and Svan folk songs. It is surprising to find these written witnesses to what is considered an oral folk tradition with no traceable past. Let us now explore the ornamented Svan repertoire in light of the three Georgian chant styles.

Krist’e Aghsdga is likely the latest Svan chant, from the eighteenth or nineteenth century as John Graham suggests,16 since it is plain mode, existing without decorated variants, and I suggest that it developed from other Western variants which, like manuscripts, made their way into this mountainous region. Its harmonic progression shares features with the plain mode Trisagion and, besides the latter’s unison cadence, the “Lord, Have Mercy;” however, even the latter has been sung as a fifth (field notes, 24 July 2017). The Trisagion is likely somewhat older, since it has multiple versions, including that for the departed, which bears ornamental features. Svan chants have not been previously categorized according to the three styles, but the principles of decoration are clear. Some, such as rhythmic expansion and ornamented key pitches, occur in all Georgian chant schools. Others, such as the addition of vowels, are similar to what we find in Shemokmedi and Martvili chants (Kalandadze-Makharadze 2014; Shugliashvili et al. 2014). The parallel use of particular vocables and the concentric repetition of smaller cyclical figures inside larger ones are Western Kartvelian features, which we will continue to analyze. One decorated Trisagion17 has different tunes and more repetition, but vocable patterns, placement thereof, and phrase structure are the same, which is why one could consider it another variant of the same chant, not simply because it shares the same ecclesiastical text. Vocables and lexoids comprise a sustainable and stable aspect of Svan song; singers consider them to be the essence, text, and tune allowing for variation and improvisation (Mzhavanadze and Chamgeliani 2016, p. 50). I add call gestures, pattern, vocable placement, repetition, types of beginnings and endings, harmonic and melodic figures, stock texts, certain structures, such as the labyrinth, and a particular type of three-part counterpoint to the prototype of the icon of Svan religious song (Freedman 2017). All these elements become clear when exploring what may be the oldest repertoire, paraliturgical hymns to Christ and St. George and a group of round dances and hymns that share certain lines of text, the same tune, and/or the same dance, as discussed in the relevant section of this article. Concerning the funeral Trisagion, the division of phrases, cadential patterns, and structure of the ornamented variants are similar to those in Gelati and Svetitskhoveli counterparts, showing how some features, not entirely text-dependent since other variants differ (cf. the Trisagion structure types described below), are common across regions. In the small group of Svan Trisagia, precise sequences of pitches or melodies are not fundamental, but they are preserved in, created by, and varied through the counterpoint of the aforementioned prototypical aspects. The co-existing repertoire of ecclesiastical chant from other schools also follows musical principles, and many are the same, such as the employment of model phrases, space between voices, labyrinth structure, trends in modulation, and some harmonic gestures. Thus, not only are Jerusalem chants translated into the Georgian language but also into recognizable local music that has its own prototypes, which can only be understood through many copies.

We conclude this section with a few historical notes. If some form of Svan polyphony dates to pre-Christian times, and given its triangular stability, Georgian chant may have taken on polyphony as part of the inculturation process in each region at an early stage. As mentioned above, this process can be measured by textual sources and other art forms, such as architecture, which the art historian Erga Shneurson considers to be an artistic form of Georgian self-identity against the background of the surrounding Byzantine and Persian cultures (Shneurson 2012). The first, functional stage of linguistic inculturation established Georgian as the liturgical language; the Jerusalem lectionaries date from this period, as do some texts still in use. The second, qualitative stage included the creation of new terminology, that is, the “education” of the Georgian language in order to translate Greek semantics, in conjunction with the translation of new material and the revision or replacement of previous translations, in order to produce, as translators wrote, “icons” of the Greek texts (Doborjginidze 2014, p. 338). This stage is when we find the first neumes, the changing of some modal assignments, the references to harmony in chant manuscripts, and the works of Ioane Petritsi; thus, musical inculturation perhaps also underwent a second stage in the central Middle Ages. Being ekphonetic, the early neumes tell the chanter “where to get”, and Tsereteli’s work shows that the slope and destination correspond with variants from nine centuries later. When a translation was complete, specialized professionals put it to music; some propose that, by the twelfth century, this process entailed setting to model melodies and subsequent harmonization (Managadze 2006, p. 410). Some posit that Georgian polyphony dates to the division of the Kartvelian tribes in antiquity, though the passage from Xenophon sometimes employed to make this point is too vague to lend support (Graham 2015). Yet, the ethnomusicologist Joseph Jordania states that choral singing was the first human music and provides countless examples that demonstrate the worldwide presence of folk polyphony (Jordania 2011). It is not out of the question that Georgian music to which Christians arrived was polyphonic. The music that they brought with them was most likely monophonic, though intriguing musical language that seems to describe instrumental polyphony occurs in patristic sources, such as St. Ephraim the Syrian’s Hymns on Virginity (e.g., Hymn 30:1; translated in McVey 1989, p. 394). Though direct documentation of such is only as early as the nineteenth century, Georgian music entails polyphonic thinking; singers often find it difficult to sing isolated voice parts and will improvise additional voices to arias or unison Western and Byzantine music (Jordania 2006, p. 9; field notes, June, August 2014). Chant development includes much creativity, and translations that fit Byzantine meter when appropriate exist alongside those that do not. As shown by hagiography, canons, and rituals, Georgians may have sung paraliturgical songs and baptized folk traditions at an early stage, and/or these may have developed alongside, or out of, ecclesiastical chant and liturgy (Freedman 2017; Ghambashidze 2006). Regarding imported Greek monophony, they may have translated at least Kyrie Eleison into new musical idioms by the ninth century, and the aforementioned life of St. Grigol Khandzteli lists this as the only Greek text in use at the time (Lang 1995, p. 147). Folk settings occur in Western regions, including the aforementioned written and sung18 Svan examples.19 As with many human phenomena, it is impossible to firmly date the beginnings of polyphony; one can only roughly date occurrences as they are discovered and may yet find illuminating pilgrim’s accounts and scribal notes. The earliest known Christian Georgian inscriptions, which include recognizable forms of what is now commonly called the “Jesus prayer”, were found in Nazareth (ca. 330–427) (Tchekhanovets 2011, pp. 458–60), and Georgian polyphony, religious or otherwise, may have been sung by pilgrims in Palestine even as early as the mid-fourth century. Once textual translations were stable, ecclesiastical music could flourish, but vocable-rich song, which does not depend on written texts, could have existed earlier. Some Jerusalem texts occur in the Byzantine rite; the paschal troparion is one; the Trisagion is another, and its music has its own model melodies. These chants exist in a multitude of polyphonic variants with interesting similarities. As is the case now, it may have been in eighth-century Jerusalem, ninth-century Tao-Klarjeti, tenth-century Svaneti, eleventh-century Mt. Athos or Sinai, or twelfth-century Imereti, for any number of texts; that is, they may have been sung by Georgians in many ways, yet always in three plaited parts along the same path, which, as we saw, cannot be done in “one and the same manner twice.” Plain mode variants may have been solidified by the twelfth century, at the end of the second inculturation stage. What some consider the most well-preserved Kartvelian folk music, Svan ritual song, shares, or has developed, features along the same lines, giving us two interrelated repertoires that embody similar principles. We will view this repertoire in a complementary way below and see that musical developmental patterns may differ, and that ornamenting with vocables may be a foundational, rather than a decorative, feature. Chants in notated and textual second-stage sources are still being sung in one variant or another, each performance constituting a new construction by those who know how to build towards the same goal. If we could have chanters from across the centuries sing for each other as Bishop Aleksander Okropiridze did from across the country in the nineteenth century, we might receive the same puzzled response, given by a Gurian choir director after listening to Eastern variants: “Why did you bother to bring us here? You have the same chants that I know” (Graham 2007, p. 102). Thus, the Georgian offspring of Jerusalem chant has multiple forms of three-part exegesis within a threefold system of styles according to regional chant schools; overlapping variations within each style and region; and a polyphonic sound since at least the high Middle Ages, interpreted by chanters according to the liturgical text, knowledge of established musical principles, and work with each other and their forbears. Early and high medieval Georgian art depicts Jerusalem through symbolic shapes and the forms of contemporary Georgian churches, which display local features like the darbazi house structure, rather than through Byzantine or Hagiopolite models (Gagoshidze 2014). We have seen the same phenomenon in sound, where chants from Jerusalem are expressed not only in the Georgian language but also according to Georgian musical forms and ornaments. The spiritual and tangible significance of Jerusalem, along with its practices and texts, are continued not through exact replication of physical form, word, and melody, but through meaningful and effective intermedial translation and iconography. Let us now further examine prototypes in Georgian chant through more in-depth examples, leaving aside questions of history and fully taking up theological discussion.

4. Musical Prototypes: Model Melodies, Foundational Characteristics, and the Case of the Trisagion

We have briefly touched on Svan Trisagia and some of their prototypical elements, and this section will look at variants of this hymn throughout Georgia and from different periods. However, we will first address the prototype phenomenon in general through field recordings and practical descriptions.

The role of model melodies as prototypes for Georgian musicians can be well understood in practice. The aforementioned mode VI troparion melody is widely known and documented, and field recordings reveal an interesting cognitive aspect. Several hymns that use this melody were recorded from the same Gurian singers in the early twentieth century. In one example, the paschal processional hymn,20 the first two lines of the hymn are sung, followed by the substitution of text with the second half of a Palm Sunday troparion in the same mode. In another example, the troparion “O Heavenly King”,21 several lines of text are skipped, which leads to fewer repetitions of melodic formulae. It is likely, then, that the models and their formulaic phrases take precedence in memory and are available for the application of texts, whether read, recalled, interchanged, mixed, lengthened, or truncated. The Georgian musicologist Magda Sukhiashvili notes that the application of text to model melodies is not a static scheme but is based on experience and understanding of principles, of the “science of hymnography”, as it is called. She describes this kind of compositional process as explained by chanters and through comparative analyses of several troparia. St Polievktos Karbelashvili, who, along with his brothers, preserved many east Georgian chants in the 1880’s, called the joining of text to melodic formulae “threading”, and the model melodies remain against the historical background of changing styles and aesthetics (Sukhiashvili 2014a, pp. 422–23). Even in the most decorated variants, they act as axes around which decorations move to and fro (Sukhiashvili 2014a, p. 423). Thus, the model melodies act as prototypes or foundational surfaces for text, but unlike monophonic chant traditions, they do so joined with various principles of style and harmonization, as we have already begun to explore. We will now return to the Trisagion. After discussing patristic theology of this hymn, we will examine the musical characteristics along with the text, continuing to identify various elements as prototypical in particular ways and giving rise to various characteristics in specific variants. We will; thus, further explore theology through analysis.

The Trisagion occurs in two primary forms: The direct quotation from the Book of Isaiah (Is. 6:3), sung during the anaphora, which begins with “Holy, holy, holy” and is combined with the praise from the account of Palm Sunday (Matt. 21:9); and an expanded and supplicatory proclamation, “Holy God, holy Mighty, holy Immortal, have mercy on us”, which occurs at the end of the great doxology, during the synaxis of the Liturgy, during funerals and memorials, and at the beginning, middle, and end of services in the daily office (Simmons 1984, p. 42). A third form occurs as the ending phrases in groups of troparia to the Trinity and the troparion for the weekday midnight office, also used for the first three days of Holy Week. Later in this article, we will explore this third form in a single Georgian paraliturgical setting, since the full troparia simply follow the given model melodies. Let us first consider the second form, keeping in mind that all are described as angelic prototypes. The second form is an interesting case for this study since tradition holds that it is not only sung but directly taught to human beings by angels (St John of Damascus, Exact Exposition of the Orthodox Faith, Book II, 10). The Trisagion also holds symbolic and powerful significance, as demonstrated in liturgical commentaries. Referring to the anaphoral form, which is sung by members of the highest angelic hierarchy, St. Dionysios writes the following:

“This, then, according to my science, is the first rank of the Heavenly Beings which encircle and stand immediately around God; and without symbol, and without interruption, dances round His eternal knowledge in the most exalted ever-moving stability as in Angels; viewing purely many and blessed contemplations, and illuminated with simple and immediate splendors, and filled with Divine nourishment—many indeed by the first-given profusion, but one by the unvariegated and unifying oneness of the supremely Divine banquet, deemed worthy indeed of much participation and co-operation with God, by their assimilation to Him, as far as attainable, of their excellent habits and energies, and knowing many Divine things pre-eminently, and participating in supremely Divine science and knowledge, as is lawful. Wherefore the Word of God has transmitted its hymns to those on earth, in which are Divinely shewn the excellency of its most exalted illumination. For some of its members, to speak after sensible perception, proclaim as a “voice of many waters”, “Blessed is the glory of the Lord from His place” and others cry aloud that frequent and most august hymn of God, “Holy, Holy, Holy, Lord of Sabaoth, the whole earth is full of His glory.” These most excellent hymnologies of the supercelestial Minds we have already unfolded to the best of our ability in the “Treatise concerning the Divine Hymns”, and have spoken sufficiently concerning them in that Treatise, from which, by way of remembrance, it is enough to produce so much as is necessary to the present occasion, namely, “That the first Order, having been illuminated, from this the supremely Divine goodness, as permissible, in theological science, as a Hierarchy reflecting that Goodness transmitted to those next after it”, teaching briefly this, “That it is just and right that the august Godhead—Itself both above praise, and all-praiseworthy—should be known and extolled by the God-receptive minds, as is attainable; for they as images of God are, as the Oracles say, the Divine places of the supremely Divine repose; and further, that It is Monad and Unit tri-subsistent, sending forth His most kindly forethought to all things being, from the super-heavenly Minds to the lowest of the earth; as super-original Origin and Cause of every essence, and grasping all things super-essentially in a resistless embrace” (Celestial Hierarchy, 7:4).

Note that the saint describes and gives reasons for the transmission of angelic hymnody to the human hierarchies. He specifies that the source is “unvariegated” and that the angels worship “without symbol”, but a result of the transmission to, and assimilation by, human worshippers is variety and variegation. Yet, the human chanting of any form leads to unity and even to equality with the angels, including participation in the circular movement around God, as St Maximos the Confessor describes in two passages from his Mystagogy:

“The triple exclamation of holiness which all the faithful people proclaim in the divine hymn represents the union and the equality of honor to be manifested in the future with the incorporeal and intelligent powers. In this state human nature, in harmony with the powers on high through the identity of an inflexible eternal movement around God, will be taught to sing and to proclaim holy with a triple holiness the single Godhead in three Persons. By the Trisagion there comes about the union with the holy angels and elevation to the same honor, as well as the ceaseless and harmonious persistency in the sanctifying glorification of God”.(Berthold 1985, p. 201)

“The unceasing and sanctifying doxology by the holy angels in the Trisagion signifies, in general, the equality in the way of life and conduct and the harmony in the divine praising which will take place in the age to come by both heavenly and earthly powers, when the human body now rendered immortal by the resurrection will no longer weigh down the soul by corruption and will not itself be weighed down but will take on, by the change into incorruption, potency, and aptitude to receive God’s coming. In particular it signifies, for the faithful, the theological rivalry with the angels in faith; for the active ones, it symbolizes the splendor of life equal to the angels, so far as this is possible for men, and the persistence in the theological hymnology; for those who have knowledge, endless thoughts, hymns, and movements concerning the Godhead which are equal to the angels, so far as humanly possible”.(Berthold 1985, p. 209)

Thus, the hymn is prototypical, iconic, transformative, and eschatological. However, one may inquire regarding its universal nature since, in any given language and musical tradition, it exists in a different sonic form or, as in Georgian, many musical variants, as well as the several aforementioned textual forms. These many forms are, as suggested above, a result of hierarchical patterns and processes and can be described in Dionysian terms as “variegated sacred veils” (Celestial Hierarchy, 1:2) that reveal what they cover. They may symbolically reflect the aforesaid “many and blessed contemplations” of the angelic orders.

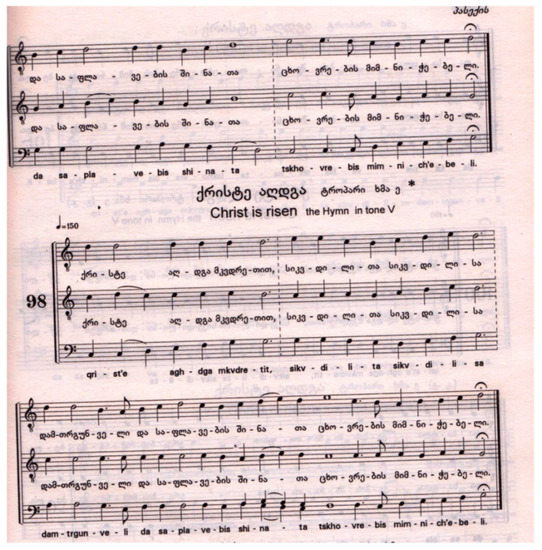

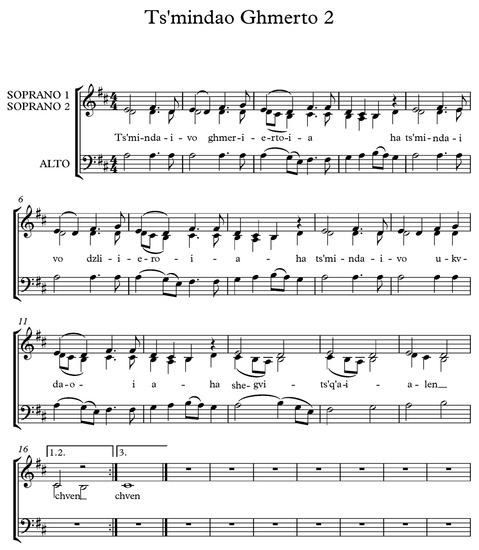

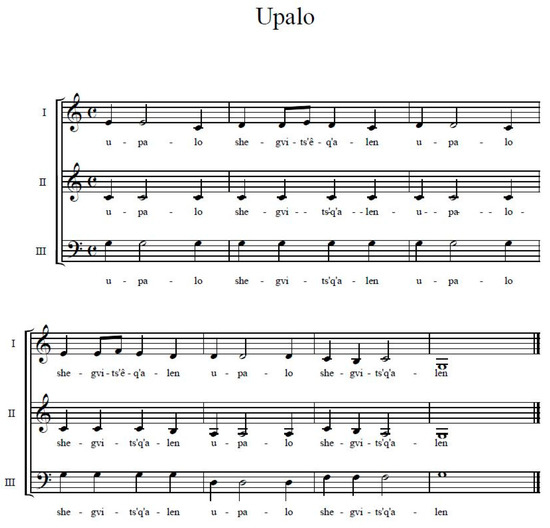

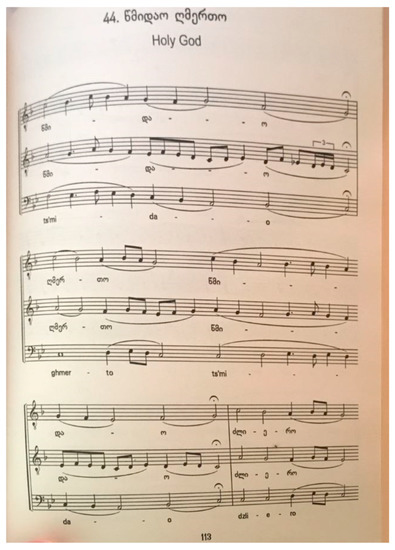

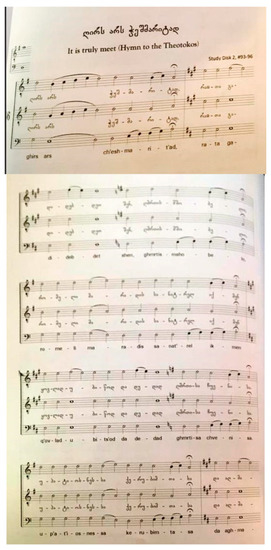

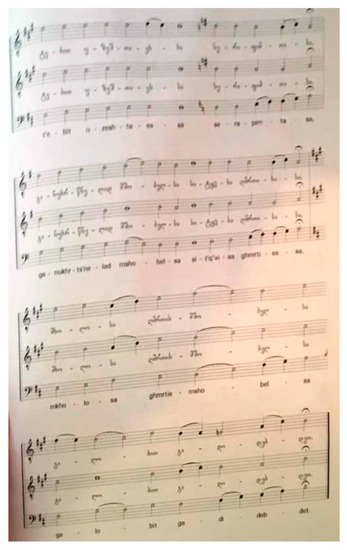

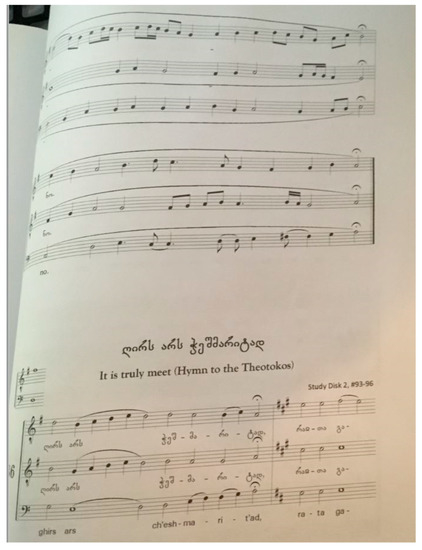

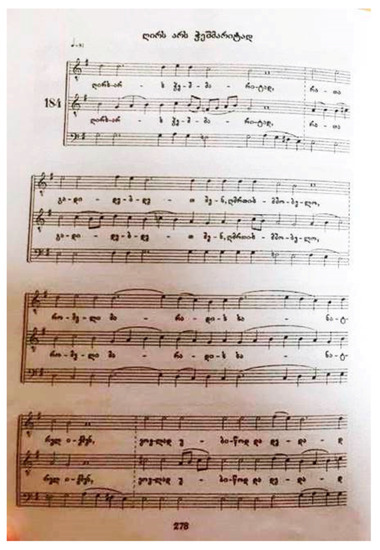

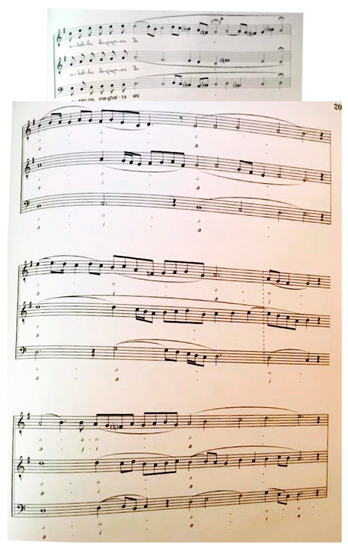

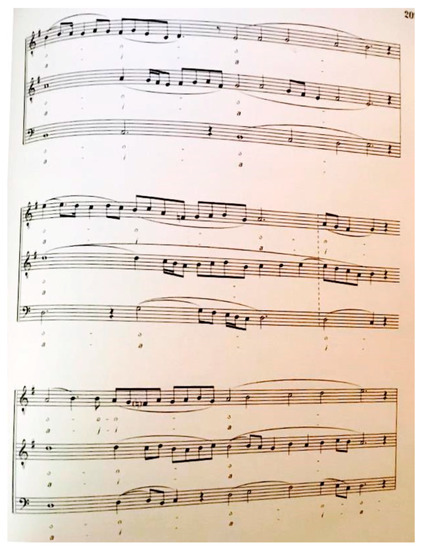

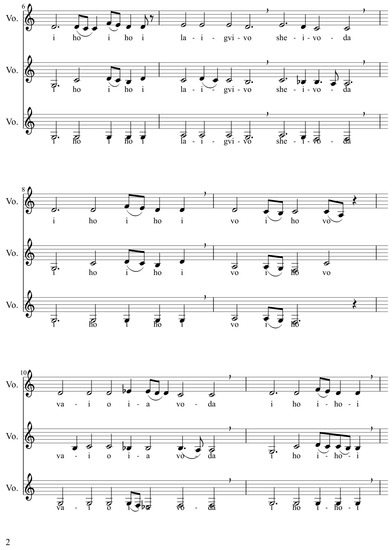

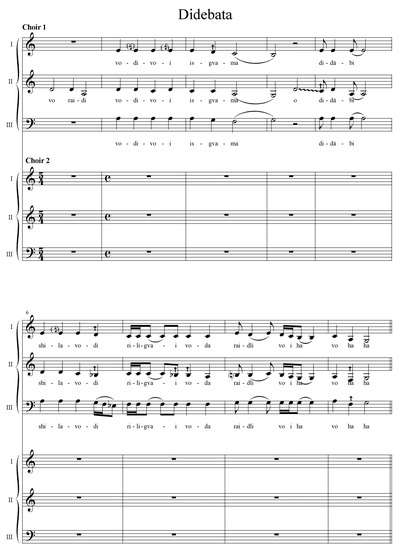

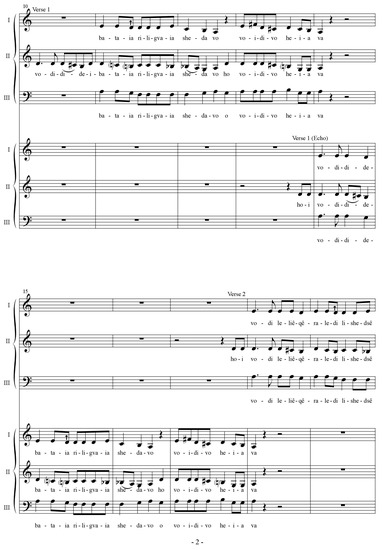

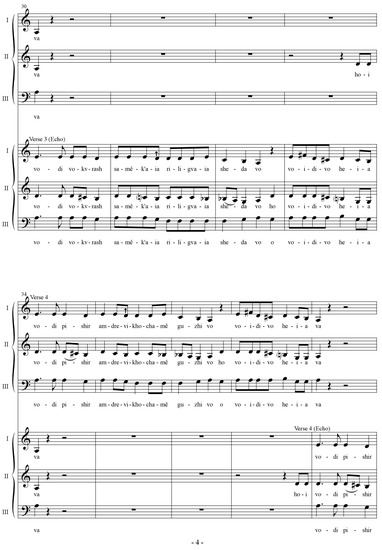

Let us now consider the second of the textual forms in its musical settings. The semantics, syntax, and, where linguistically appropriate, grammar of the text are generally shared across languages. Therefore, the text can be said to be a prototype with many sonic icons even where speech is concerned. It can be labelled with the structure AbAbAbC, A marking the repeated vocative “Ts’mindao”, b the other vocative, and C the imperative phrase; AAAB is the overall structure without divided vocative phrases. Yet, this text relates to given musical examples in a variety of ways. For liturgical examples, we will describe only the first iteration, though the hymn is sung four times at an ordinary Liturgy; some variants contain different settings for the third of these repetitions. The aforementioned ornamented Svan setting for the departed has the parallel musical structure AbAbAbC, as do Gelati and East Georgian funeral variants. Some liturgical settings, also in both Eastern and Western examples, join the final vocative to the imperative, rendering the structure AbAbAC (Figure 9 and Figure 10).22

Figure 9.

Trisagion; Svetitskhoveli School (Shugliashvili and Tsereteli 2012).

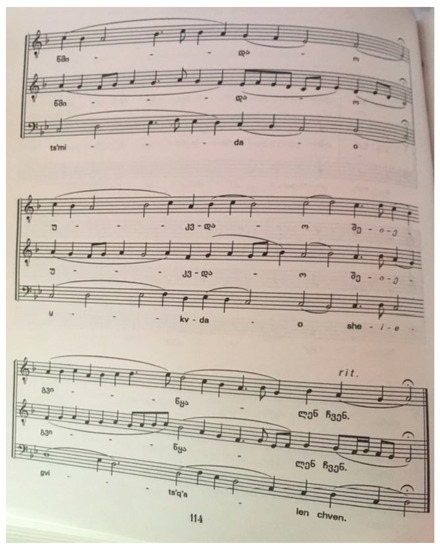

Figure 10.

Trisagion; Gelati School (Chkhikvishvili and Razmadze 2010).

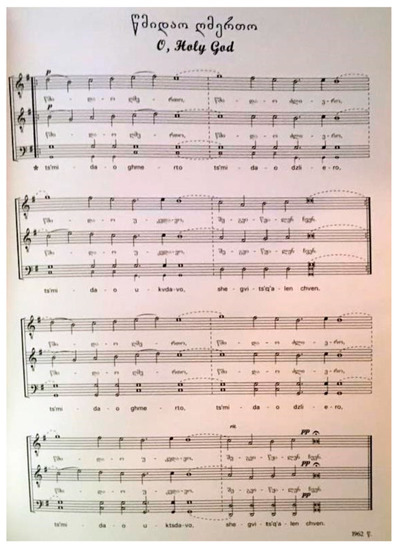

Yet other settings treat the text as a sort of ascending tricolon, again across Georgia, giving rise to such forms as Aa′B (Figure 11) and ABC.23

Figure 11.

Trisagion; Gelati School (Chkhikvishvili and Razmadze 2010).

The repetition can inspire yet further permutations, and the popular setting by the current patriarch, Ilia II, has the form AbbC (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Trisagion; composed by Patriarch Ilia II (Jangulashvili 2013).

A lower Svan variant repeats vocatives, rendering the textual structure ABACADEACDE and the musical form AaaBCB′, whose rhythm is like that of the above plain mode Upper Svan variant (field notes, November 2015). Like the above paschal troparion, these structures are further developed through harmonization, which, for instance, can turn a into a′ and a″. Principles of musical form, such as medial and final gestures, have a similar role (e.g., B and B′ in the Lower Svan Trisagion), and the same affect harmony, the middle ceasing its parallel motion and reflecting the top voice’s ascent, moving down a step in order to form the cadential fifth. Changes in ornamentation have similar effects in varying the repetitions, as in variants of the Svan funeral Trisagion, whose figures we will discuss below. Thus, as we previously saw with Svan vocables, principles and elements of musical composition direct the making of a chant alongside the text, and in rendering any given copy of a prototype, harmonic, contrapuntal, and decorative aspects work in synergy. The text, its sounds, and its structure act somewhat like the basic warp in a balanced textile, and the musical features act like multifarious ground and pattern or supplementary wefts. Pattern warps may also be added, such as additional vowels and vocables.

Returning to the topic of the angelic prototype of the Trisagion, while we discussed a theological, hierarchical basis for variants above, one may ask how it practically relates to the many forms sung by human beings. No language or tradition claims to have the original melody or to be concerned with recognizing it. In part, this state of things has to do with the nature of the relationship between icons and prototypes, in which many copies exist, employing various media and techniques, displaying different styles and details, and containing inscriptions in different languages. While questions about literal copying may be difficult to address, we can relate Trisagion variants to their prototype not in the way that an icon relates to its iconographic prototype but to its participation in its theological one, that is, to the depicted person. One may ask, then, where this puts human chanting in relation to that of angels. We have discussed the hierarchical transmission process and begun to analyze some of its results. We can conclude that the outcome is not simple repetition but the creation of hymns, using skills, language, and musical materials accordingly and in co-operation, within the spiritual hierarchical framework. Indeed, an angelic sound may not even be reproducible but only somehow translatable through a multitude of utterances, and angels may have taught translations, providing sonic parallels to the forms in which they appear, which humans can perceive but which are not indicative of their nature (St John of Damascus, Exact Exposition of the Orthodox Faith, Book II, 3). In his aforementioned Celestial Hierarchy, St. Dionysios discusses how and why angels and God are described using symbols, often quite incongruous (2:5), and the great variety of liturgical sounds and utterances can be understood as having a similar function. Furthermore, in his Divine Names, he writes that, through “supremely divine hymns”, that is, chant, “we are molded to the sacred songs of praise”, that is, angelic hymnody (1:3). Chant in the earthly hierarchy, insofar as it is inspired by that of the heavenly, becomes like unto it in a fitting way, which is not in every way bound up with its discernable characteristics. Chant, then, has an apophatic side, in which it is understood to point to incomprehensible sound and experience. Nevertheless, the saint states that we, unlike angels, need symbols, and humans help to create the same, though they are ordained by God and given as “sacred veils of the loving-kindness towards man” (Divine Names, 1:4). It is fruitful; therefore, to fold and unfold sonic symbols, studying all aspects of sacred song.

Other patristic works provide further insights on the idea that human and angelic worship are not by all means dissimilar, and St. Dionysios himself specifies that lower hierarchies participate in the characteristics of higher ones but to a fitting degree (Celestial Hierarchy, 4:3), and that every individual participates in God. Near the end of his Celestial Hierarchy, he provides this note: “I might add this not inappropriately, that each heavenly and human mind has within itself its own special first, and middle, and last ranks, and powers, manifested severally in due degree, for the aforesaid particular mystical meanings of the Hierarchical illuminations, according to which, each one participates, so far as is lawful and attainable to him, in the most spotless purification, the most copious light, the pre-eminent perfection” (10:3).

Regarding hierarchical participation, St Symeon of Thessalonike (1381–1429) applies the names and qualities of the highest angelic hierarchy—cherubim, seraphim, and thrones—to human beings who bear their characteristics, especially as they pray (Simmons 1984, pp. 9–13); it is understood that such are passed on to, and copied by, the human ecclesiastical hierarchy, monastics, and laypeople. Yet, strikingly, shared angelic and human co-operation also has a reciprocal aspect, and while St. Dionysios describes angels teaching men (Celestial Hierarchy, 4:4), St John Chrysostom states that angels also learn from humans (Homilies on the Gospel of John, II), grace working in synergy with all created beings (Loudovikos 2010, p. 15), with the Holy Spirit directing and inspiring everyone (Hildebrand 1980, p. 64). The forms of the Trisagion help to show this co-operation in practice.

The entire anaphora displays co-operation across all hierarchies, heavenly and earthly, angelic and human, priestly and lay, and the angelic-human relationship clearly occurs in the Trisagion. The first two phrases are the seraphic Trisagion as described by the Prophet Isaiah, while the refrain-like “Hosanna in the highest” and third phrase were the children’s worship of Christ at His entrance into Jerusalem. Children, to whom the Kingdom belongs, like angels, have an important role in leading worship and, as highlighted in Georgian hagiographic examples, confessing the faith (Lang 1995, pp. 40–43). The second form of the Trisagion hymn, though confirmed in its correct form by angels as mentioned above, was miraculously heard by a child, and it also contains distinctly human praise, as St. Symeon of Thessalonike again describes. He explains that the hymn was composed by the Church Fathers, giving the origin of each word or phrase, including the three “Holy’s” from the seraphim, and points out that all other phrases come from the Scriptures, primarily from the Prophet David in the Psalms, and were sung in the Spirit (Simmons 1984, pp. 41–42). He describes how an angel confirmed the form of the hymn to a child when Peter the Fuller attempted to add an element that was deemed to be heretical (Simmons 1984, p. 42), mentioning the importance of children as much as of prophets and demonstrating that angels not only provide hymnography but are understood to confirm the prototypical value of inspired human utterances. Human contributions can; therefore, be easily identified. Even angelic praises, when uttered by human beings, will, like the shouts of the children in first-century Jerusalem, come from particular voices in a particular language and in a particular style and form. Along this line, St Symeon also interprets instances when the Trisagion is sung “with melody” as symbolizing the Gospel being preached and filling the whole world (Simmons 1984, p. 38). Thus, as in preaching, a word or prototype leads to ever-increasing and varying expressions, covering the entire linguistic and associated sonic and cultural scope. Besides angelic and human co-operation in the Spirit, the Incarnation, Resurrection, and process of deification have implications for the nature of chant, which we will further reflect upon in the conclusion of this study. St. Dionysios explains that chant teaches us, constitutes worship, and, like all other aspects of hierarchy, helps to make the work of Christ effective, in the following passage from the Divine Names: