1. Introduction: Theme and Approach

The chance encounter related in the opening vignette has formed the basso continuo of our work on Cemetery Tongerseweg in Maastricht. A highly engaged visitor to the cemetery—during our conversation, the man also relates that he occasionally fulfils volunteer tasks in the cemetery such as guiding around other visitors, and he sports a small container with a rosary which he regularly uses for prayers at the grave of his grandparents—feels that the cemetery consists of distinct spaces that seem to belong to identifiable groups. Even if the cemetery section to which our interlocutor refers may have become over the years the resting place of members of many more minority groups and may have lost its sharp edge of anticlericalism vis-à-vis a majoritarian Roman Catholicism, there still seem to linger the long shadows of memory, tradition and so forth, that define the atmosphere, the character of a cemetery section and make the section the rightful ritual space for some and out of bounds for others.

This raises questions for prevalent conceptualizations of the cemetery as a ritual space: Could it be the case that scholars have been overly focused on the cemetery as a unitary ritual space at the expense of internal divisions? And, could it be the case that scholars have not taken sufficient note of the historical dimension of the cemetery as a ritual space?

The spatial structure of a highly differentiated cemetery such as Maastricht Tongerseweg is something in need of explanation. How do internal divisions relate to divisions between groups and communities that use the cemetery? How deeply entrenched are those divisions, and what is the evidence for the (re)negotiation of identities? Finally, and perhaps most important of all, how does all of this play out in a historical perspective? In order to understand how practices, memories and traditions shape a complex cemetery such as Maastricht, we need to refine the concept of ritual space. It is certainly correct that space that is sequestered in certain ways becomes what is generally referred to as “the cemetery” as a ritual space. However, a ritual space thus understood falls into two interconnected but clearly distinguishable categories: on the one hand, there is a ritual space “as actualized”—the space where we conduct, participate in or perceive a specific ritual, be it in the context of a funeral, a visiting ritual and so forth. On the other hand, however, a ritual space thus understood uses and actualizes what can be referred to as ritual space “in potentiality”—a spatial structure that defines certain actions as mandatory, optional, transgressive and so forth. Ritual space in the latter sense is the result of historical processes, the sedimentation of past practices, memories and traditions; it is at least in part the result of distinctive ritual acts in the past. At the same time, it also provides the potentiality for distinctive ritual acts that we can observe in the here and now. It defines the atmosphere, the character of distinctive parts of a cemetery, such that distinctive ritual acts that are entirely fitting in one part of the cemetery may be contentious or offensive in others. For instance, a cemetery that contains parklike sections might be a fitting décor for sitting on a bench or in the grass, for sharing food and champagne to celebrate the life of a deceased, whereas it is hard to imagine such activities as acceptable in an Islamic part of the same cemetery.

When

Grimes (

2014, p. 256) explains that “a cemetery remains a ritual space even when no burial or ash-scattering is going on”, he gestures towards an understanding of the cemetery as a ritual space that we presuppose here. People do not simply step into a predetermined setting but contribute to the “spacing” of a cemetery, that is, the relational positioning of objects. The concept of “spacing” was developed by sociologist Martina

Löw (

2001, pp. 158–59) and can be summed up as the active placement of objects in space and the positioning of symbolic markers in relation to each other in perception, imagination or remembrance—a performance described as “synthesizing” (

Synthetisierungsleistung) (

Adelmann and Wetzel 2013, p. 181). This dynamic cocreation of space is a staple feature of the “spatial turn”, which has taken a particular interest in bordering processes. Again, the emphasis is on the processual and action-based creation of delimitations. In that context, an understudied text by Georg Simmel has been unearthed and only recently translated into English, which defines the boundary not as “a spatial fact with sociological consequences, but [as] a sociological fact that forms itself spatially” (

Simmel [1908] 1997, p. 143,

[1908] 2006, p. 23). It already encapsulated ideas later developed by Henri Lefebvre and others:

The idealist principle that space is our conception, or more precisely, that it comes into being through our synthetic activity with which we give form to sensory material, is specified here in such a way that the formation of space which we call a boundary is a sociological function. Of course, once it has become a spatial and sensory object that we inscribe into nature independently of its sociological and practical sense, then this produces strong repercussions on the consciousness of the relationship of the parties. Although this line only marks the diversity in the two relationships, that of the elements of a sphere among each other and that among those elements and the elements of another sphere, it becomes a living energy that forces the former together and will not allow them to escape their unity and pushes between them both like a physical force that emits outward repulsions in all directions.

This “living energy” is also visible enough in cemeteries, whose perimeter is clearly established, and which may have different sections, separated by hedges, walls or pathways (

Rugg 2000, pp. 261–63).

We would like to stress here that these “repulsions” do not simply reflect social boundaries and their changes over time but develop a spatial dynamic of their own, which must be discussed in terms of the dynamic cocreation of space by stakeholders, trying to realize (partly incompatible) legal, hygienic, political, aesthetic, religious and other values.

So, what we are concerned with in this article is ritual space in the aforementioned sense: wherever we speak, for the sake of brevity, of “ritual space”, we refer to ritual space in the sense of its potentiality-giving function.

Our research showcases an integrated approach that draws on the insights of symbolic anthropology and history to tackle the above questions. The methods we have employed range from in situ observations and interviews to the historical “mapping” of cemetery sections, archival and literature research, and the analysis of visual materials.

1 2. State of the Art and Literature

It hardly needs stating that our approach constructively engages with a host of literature in the fields of religious studies, ritual studies and death studies. In all three fields, the concept of space is either foundational or has become important in recent decades. The study of ritual, in particular, has had space and place at heart.

Van Gennep (

[1909] 1960) notes that all rites of passage are accompanied by a territorial passage (e.g., carrying the bride over the threshold or a procession with the newly dead to the cemetery), whereas

Smith (

1987) even entitled his major study of ritual

To take place. As we have indicated, in spite of all the interest in ritual space and place, the concept of ritual space needs further refinement. A good illustration of this is, for instance,

Grimes’ (

2014, pp. 256–62) long list of (alleged) “misconceptualizations” of ritual space in binary oppositions or

Alles’ (

2017) rejection of too rigid understandings of borders and boundaries that define ritual space. This has become even more pressing in view of the pluralization of societies in Northwestern Europe (e.g.,

Baumann 1992).

Post and Molendijk (

2007, p. 279) point at “the rise of increasingly multireligious urban ritual spaces”; an example

par excellence of these ritual spaces is public cemeteries. In this article, we look at the “pluralistic communities of the dead” (

Laqueur 2015, p. 294) in Maastricht’s municipal cemetery Tongerseweg from its establishment in 1812 until today. What have been the dynamics of this ritual space in a period of over two centuries?

In the fields of religious studies and death studies, the “spatial turn” (

Knott 2010) has become something of an orthodoxy. Academic scholars of death too have taken note of the concept of deathscapes (

Kong 1999;

Maddrell and Sidaway 2010) and understand cemeteries as sequestered places (

Hüppi 1968;

Rugg 2000;

Sörries 2009). Much of the current literature refers to Foucault’s 1967 talk (published much later as

Foucault 1986) “Des espaces autres”, in which he invents the category of “heterotopia”. Heterotopias are “real places … which are something like counter-sites, a kind of effectively enacted utopia in which the real sites, all the other real sites that can be found within the culture are simultaneously represented, contested, and inverted” (

Foucault 1986, p. 24).

Foucault reflects in the short text twice explicitly on cemeteries as instances of heterotopias. In the present context, we cannot review or engage the rich literature that comments on Foucault’s sometimes cryptic remarks (but see, e.g.,

Dehaene and De Cauter 2008;

Spanu 2020). Suffice it to say that we see our effort here as a constructive engagement with Foucault’s theory: our attempt to combine symbolic anthropological and historical research strategies dovetails with Foucault’s attempt to see the category of the spatial as the sedimentation of the historical. Our effort here tries to mine the potential of Foucault’s approach even where he (in our view) underutilizes the potential of the new category: most importantly, Foucault still talks of the cemetery as a unitary space, “where each family possesses its dark resting place” (

Foucault 1986, p. 25). Such depictions of the cemetery as a depot of (bourgeois) family history may reflect iconic French cemeteries such as Père Lachaise. Against this background, it is, we tend to think, doubly interesting to analyze with the case study of Tongerseweg Maastricht, a cemetery that followed at its inception French regulations, and has over the course of its 200-year history reached a point where it has to grapple with cultural and legal changes in Dutch society that have ended cemeteries’ monopoly as mandatory resting places, with all the reverberations of that change.

Foucault himself allows for heterotopias to juxtapose “several sites that are in themselves incompatible” (

Foucault 1986, p. 25), but does not relate this in any way to cemeteries (his examples are the theatre, the cinema and the garden) and curiously he does not, for all his usual interest in power constellations, present cemeteries or, for that matter, other heterotopias as historically contingent ritual spaces that are coproduced by different actors.

For all the heuristic value of Foucault’s concept of heterotopia, our approach highlights that the cemetery is less of a “counter site” but very much a continuation of the struggles, identity formations, appeals and positionings that characterize our society. Moreover, our approach highlights the internal divisions in the cemetery and the complex relationship with communities and groups.

Cemeteries are, in the words of

Tarrés et al. (

2018, p. 12), “spaces where communities can express their identities and their construction of otherness.” The modern cemetery is a social and public arena in which identities can be claimed in a more or less ostensive way, subsumed, suppressed, denied or contested (see also

Francis et al. 2005). The “new model of the cemetery” emerged at the end of the eighteenth and even more markedly in the beginning of the nineteenth century (

Ariès 1985, p. 216; cf.

Etlin 1984;

Worpole 2003). Under the influence of the Enlightenment, mainly for hygienic reasons, the graveyards were to be located outside of the towns. The new cemeteries had a predetermined layout of grave plots. Some were even parklike with a geometrical ordering of space, dividing it up into distinctive grave fields (

Kolnberger 2018;

Heemels 2010, pp. 127–28). The future cemeteries envisioned in the eighteenth century took terribly long to materialize (

Cappers 2012, p. 241). In the years just before the French Revolution, it followed from the plans that “the topography of the cemetery reproduces society as a whole,” according to Ariès (

Ariès [1977] 1981, p. 503). In his view, the “primary purpose of the cemetery is to present a microcosm of society” (

Ariès [1977] 1981, p. 503).

2 This idea of the modern cemetery as a “mirror image” of society has been taken up in the literature on cemeteries (e.g.,

Kamphuis 1999, passim;

Sörries 2009, p. 177).

Heemels (

2006) examined this with regard to the main cemetery of Roermond, another town in the province of Limburg (Netherlands), for the period between 1870 and 1940. He found that in the predominantly Catholic town, the social stratification was clearly reflected in the locations of burials around 1880, but less so around 1930, partly because this was affected by the earlier purchase of family graves (

Heemels 2006, pp. 154–58). Maastricht, with twice the number of inhabitants compared to Roermond, knew and knows greater diversity. As

Francis et al. (

2005, p. 195) note, “for members of minority and immigrant ethnic groups, cemeteries can play a significant role in creating a sense of community beyond the strictly familial.”. We are interested in the question of how the cemetery inscribes the identities of various communities in spatial terms.

At the same time, we argue that the spatial order of a cemetery as a ritual space should not be considered as a mere reflection of society. Clifford

Geertz’s (

1973, pp. 93–5) distinction between a model

of reality, in contrast to a model

for reality is still helpful here. In other words, we need to distinguish what is from normative ideals, from what actors believe ought to be. How space in the cemetery is divided up in bounded areas can also speak to aspirations or to “an idealized conception of the social order” (

Rugg 2013, p. 5) and feed back to the social relations of the living.

We want to make headway with an analysis of the complexities of such a process of “cocreation” of ritual space that gives full weight to the recognition of the cemetery being home to plural communities, whose diversity is reflected or enhanced, but also downplayed, mitigated or denied in the complex interactions that create the cemetery as a plural ritual space.

Those complexities have not been fully understood, even though helpful, partial observations have been noted in the literature. For instance,

Sutherland (

1978, p. 47) highlighted the interactive nature of the nexus between social organization and physical environment:

When we try to understand how societies use space, how they divide it up both conceptually and physically, we are looking at a combination of their form of social organization and their perception of the physical environment. Both of these elements, the social as well as the physical, will form a single interacting whole in which no one element can be said to determine the other.

Social identities or categories are marked by boundaries in physical space. They have to be understood in relative terms. The boundaries distinguishing one from the other are betwixt and between. They separate and connect at the same time. Because the boundaries need to stand out, being neither the one nor the other and both at once, and, therefore, are ambiguous, they happen to be addressed with ritual (

Leach [1976] 1978, pp. 41–4). Identities are always relational: “the identity

is in important senses the boundary” (

Jenkins 2008, p. 142). Cemeteries do not passively “track” societal developments; they are constructs that have been and are continuously shaped, actively, on the basis of social, political and economic ideas and ideals at different levels of government and on the basis of the aspirations and ideals of their users. As a result of explicit or implicit contestation, the cemetery can be conceived of as an arena (

Turner 1974, pp. 129–36). Cemeteries should be considered “temporal topographies” in which space and time coalesce (

Nielsen 2017). “As liminal, betwixt-and-between sites where geography and chronology are reshaped and history is made spatial, cemeteries are places of social, religious and ethnic continuity and belonging” (

Francis et al. 2005, p. 195). In order to tease out how cemeteries as ritual spaces produce communal identities, special attention should be given to processes of territorial segmentation.

The cemetery is often seen as the epitome of modernity. The churchyard, in contrast, has become associated with tradition.

Rugg (

2013, p. 9ff), however, argues that the binary opposition rests on stereotypes. She speaks of “false dichotomies” and relates that a churchyard can also be profitable and express social distinction, whereas a cemetery is not necessarily secular but can, in part or whole, be consecrated (ibidem). Although Rugg does not mention them, the stereotypical contrast fits well with Tönnies’ notions of civil society (

Gesellschaft) and community (

Gemeinschaft), respectively (see

Tönnies [1887] 2001). Cemetery Tongerseweg, as we will see, was also for the largest part consecrated.

3 The present article demonstrates the need for and usefulness of a fresh look at the nexus of ritual space and cemeteries with a case study, the monumental Cemetery Tongerseweg in Maastricht, The Netherlands. Tongerseweg is a particularly rich case study due to it being a municipal, public cemetery in a culture defined by Roman Catholicism: the cemetery has its roots in the burial reforms ushered in under French rule during the Napoleonic era, is still in active use after two hundred years and currently undergoes a new wave of redevelopment. After a short overview of the history of the cemetery (3), we will analyze Cemetery Tongerseweg in four episodes (nineteenth century (4), early twentieth century (5), late twentieth century (6), future planning (7)) as a pluralistic ritual space that is continuously (re)constituted and (re)negotiated by administrators, users and their allies. We continue (8) with a discussion of the relationship between ritual spaces and communities in which we propose a new “Arena Model” of this dynamic relationship. We end with a brief reflection on the applicability of the Arena Model beyond the case of Maastricht (9).

3. Cemetery Tongerseweg, Maastricht

Cemetery Tongerseweg was planned and realized in the early nineteenth century under French rule, in the name of the hygiene and societal reform. The decision to build a general cemetery to the west of the crowded medieval town center of Maastricht was made in 1805. The cemetery was to replace several cemeteries run by religious communities (Catholic, Lutheran, Calvinist, Jewish) in the old center and was to cater for the dead of all religions and social echelons (

Minis 1994,

2012;

Noten 1998). The French legal situation at the time was defined by a law from 1804, leaving municipalities the choice between separate cemeteries for the different religions or indeed a single communal one, with provisions for the different faiths. In that case, walls, hedges or canals should separate the different sections, which each should be given separate entrances.

4 In Maastricht, this was seen as an opportunity to fuse the different cemeteries into a single one, following the French example (cf.

Ariès [1977] 1981;

Van Helsdingen 1987; for further details, see

Cappers 2012, pp. 240, 253). In 1809, the site at the road towards Tongeren (in Belgium) was selected, then located in the village of Oud-Vroenhoven (

Bruijnesteijn van Coppenraet and Denessen 2002, p. 21). The main, Catholic part of the cemetery was consecrated on the 27th of January 1812 by Hendrik Partouns, vicar of the Roman Catholic Saint-Nicholas Church (

Minis 2012).

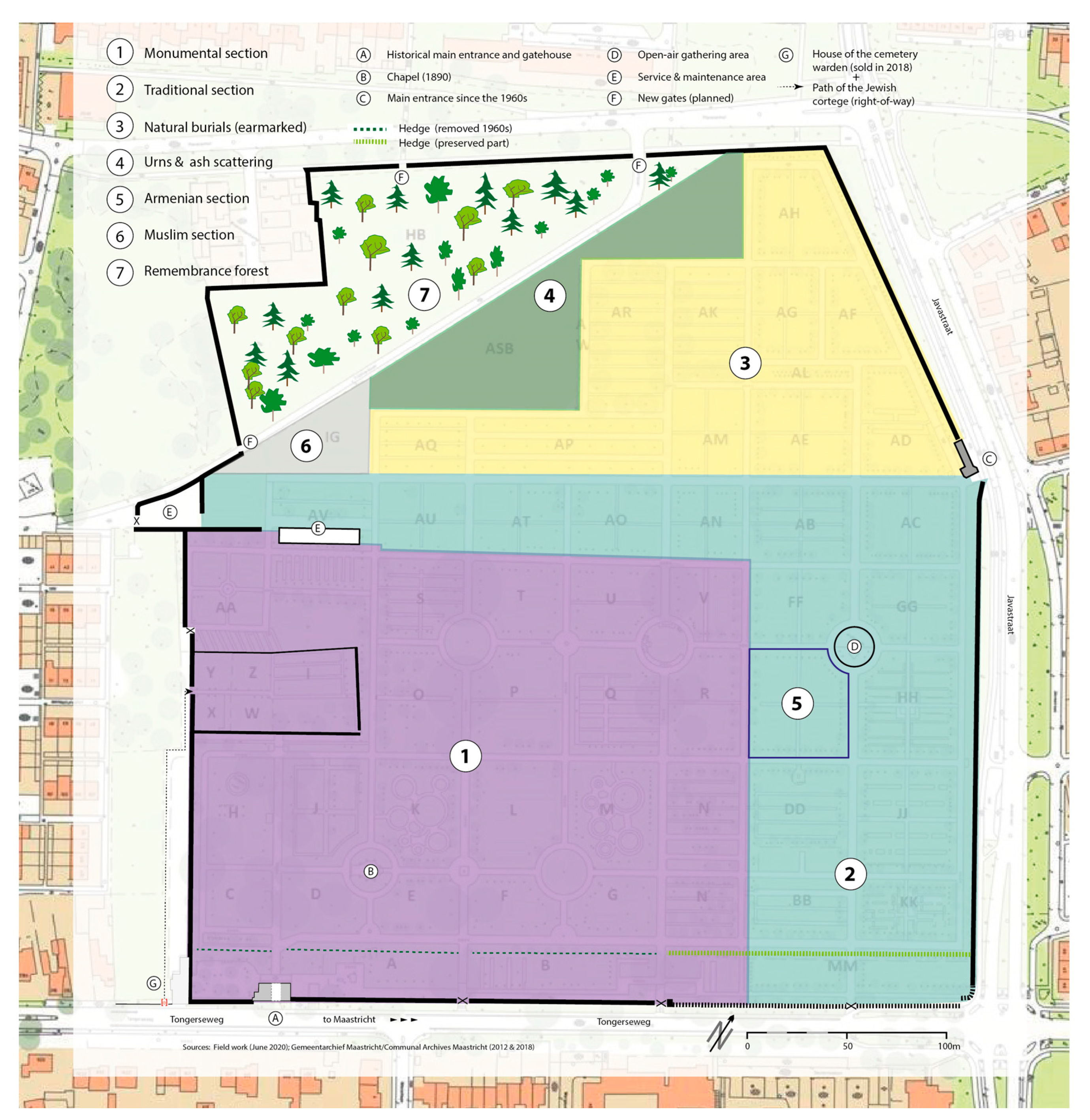

With growing needs, the cemetery was extended three times in the north-eastern direction, towards the city center of Maastricht (in 1857, 1910 and 1956; see

Figure 1) and is today part of Maastricht’s western perimeter. Each extension came with significant cemetery developments which related to changing religious, political, legal and economic circumstances. For instance, after the first extension, the Catholic dead could be buried in grave plots of three distinctive classes: the most expensive were alongside the pathways, whereas the cheapest plots were out of view and practically out of reach (

Heemels 2010, p. 130). Furthermore, a Catholic chapel was added to the cemetery in 1885, founded by the Clarenboets family and representing the four Catholic parishes of Maastricht of that time (

Van Raak 1995, p. 95). With the second extension, new grave fields were opened for Socialists and other “dissenters”. The third extension drastically altered the plan of the cemetery; a new main entrance was created at its northern perimeter, next to parking lots along the street (

Figure 1, C).

At present, over 125,000 people are buried in the over twelve hectares of consecrated and unconsecrated ground. As the numbers of traditional burials are decreasing, and the amount of people who opt for cremation is increasing, the story of the cemetery’s development does not end here. A new business plan (

Gemeente Maastricht 2018) prepares the cemetery for the future by making possible a fourth extension towards the Northwest. In the main section of this article, we will delve into these historical and future developments in more detail.

4. Nineteenth Century

By the mid-19th century, there was a clear separation of the Jewish section of the cemetery by means of a massive brick wall and a separate entrance, and a less solid—but nonetheless highly visible—separation of the Lutheran and Reformed Protestant sections vis-à-vis each other, and jointly from the main, Roman Catholic part of the cemetery (

Figure 2, C; and the brick wall in

Figure 3a). Protestants were part of the civic elite in Maastricht and the Province of Limburg, so the positioning of their graves near the entrance could signal social distinction. However, at the same time, the Protestant community was also religiously separated from the majoritarian Roman Catholic community. In order to underscore the distinctness of communities, a row of hedges was planted directly behind the Protestant cemetery sections (

Figure 2, B1 and B2; see also

Figure 3b and

Figure 4).

The separation of religious communities, however, cut across another type of community, the family. The cemetery still contains evidence that allows us to see users of the cemetery affirming family bonds as more important than religious community. A case in point is a group of three monumental sarcophagi (see

Figure 3b).

The grave of Pieter Daniël Eugenius MacPherson (grave A in

Figure 3b) is the earliest sarcophagus in the ensemble. Born in Armentières in 1792, he had been a member of the Council of State and governor of the Duchy of Limburg, of which Maastricht was the capital city. He died in Maastricht in 1846. His grave was created in a classicist style that was fashionable in the period, replete with classicist symbols of life and death (palm motifs, winged hour-glass, inverted torches), whilst avoiding overtly denominational Christian symbols. The hedge separating the sections would have extended directly behind MacPherson’s grave. The hedge would have been at least a meter in height (

Figure 3b), which would have affected the visibility, and thus explains the arrangement of, the inscriptions. Inscriptions memorializing the high office MacPherson fulfilled in public life face towards the entrance, whereas information about his birth and death are displayed at the back side, towards the hedge.

On the other side of the chasm where the hedge was located, we find two sarcophagi that are remarkably similar to MacPherson’s and were clearly intended to match and echo his on the other side of the hedge. They are the sarcophagi of MacPherson’s wife, Jonkvrouwe Rosa Maria Johanna van Meeuwen (1901–1889) (B), and his brother in law, Jonkheer meester Petrus Andreas van Meeuwen (1772–1848) (C), both members of the Roman Catholic Van Meeuwen dynasty of North Brabant. Their sarcophagi exhibit a comparably restrained classicist iconography at the expense of Christian symbolism. Again, the inscriptions are located in such a way that the epitaphs outlining the public roles of the deceased were best visible to the visitors of the Roman Catholic section, facing away from the hedge. The religious background of the deceased explains the positioning of their sarcophagi in the Roman Catholic section. But it is also clear from the design and spatial layout that with their sarcophagi, every attempt is made to reach out, as it were, across the hedge and emphasize family, rank and class as communities that bridge the divisions of religious communities.

6. End of the Twentieth Century and Onwards

With the cultural and political changes in the second half of the twentieth century—a marked easing of tensions between Socialism and Roman Catholicism after Vatican II—the dissenters’ cemetery section took on a new function: it became the resting ground for people with a variety of non-Christian religious and diverse ethnic backgrounds, such as Chinese-Vietnamese (Hoakieu) boat refugees who came to The Netherlands during the 1970s. When the first Muslims died and wanted to be buried in Maastricht in the 1980s, the cemetery management decided to reserve a space in the dissenters’ field for them as well. Tucked away in-between the Jewish section wall and the dissenters’ section (see

Figure 6), the Islamic graves were dug in such a way to abide by the ritual requirement of being buried facing Mecca.

Whilst the small number of deaths in the Muslim community would not have made a dedicated cemetery section necessary in the short term—the first major wave of young Muslim migrants came to The Netherlands as late as the 1960s to work

inter alia in Maastricht’s manufacturing industries—the mid-1990s saw the realization of a dedicated Islamic cemetery section (see

Figure 6). The change had not only been made necessary by the growing Islamic population in the town but also by a new law—the Burial and Cremation Act 1991 (

Wet op de lijkbezorging 1991), which stipulated that upon request, religious communities must be given a proportionate area of a municipal cemetery dedicated to them (Wet op de lijkbezorging, 1991, article 38). This largely reiterated the Burial Act of 1869, but the revision of 1991 sought to eliminate remaining obstacles for the various religious groups. In line with Islamic ritual prescriptions, Muslims were now granted “the legal possibility of burial without a coffin and within 36 hours”, a provision that led to an increase in Islamic burial plots (

Kadrouch-Outmany 2014, p. 89).

It is notable how some grave markers in this Islamic section evoke dual or multiple communities. A case in point is an Islamic grave of a Turkish woman who died in 2015 at the age of 27 (see

Figure 7). The grave is situated in the Islamic section of the Tongerseweg cemetery, already indicating the religious background of the deceased. Her religious identity is also clearly visible in the two prayer beads that are draped around the headstone, and the inscriptions

Rahman ve Rahim olan Allah’in adıyla and

Rahuna Fatiha. The first inscription means “In the name of God, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful”. It is the famous

basmalah that is recited before each

surah in the Qur’an. It is also used in everyday life in many parts of the Arabic world as a precursor for actions, to invite God’s blessings upon the action (

Fani and Hayes 2017). The second inscription is a petition for the visitor of the grave to recite the first chapter of the Qur’an (the

surah al-fatiha) to the soul of the deceased. Doing this is deemed good for both the visitor and the deceased, as

fatiha means victory (

Özdemir and Frank 2000, p. 102).

But, not only the Islamic background of the deceased woman is communicated by the headstone. At the same time, she and her mourners are introduced as members of both the Turkish and Dutch language communities. The above-mentioned inscription rahuna Fatiha is a phrase commonly spotted on Turkish graves and thus emphasizes the deceased’s position within the Turkish community. The inscription on the left side of the gravestone seems to be a personal message, written by a family member. Expressed in it is the wish that her soul will rest in heaven and the promise that she will always live in the hearts of those left behind. Underneath, a small text in Dutch refers to the deceased as “our beloved daughter, sister, aunt and sweet mama”. While the gravestone thus emphasizes the specific Islamic and Turkish backgrounds of the woman and her relatives, at the same time it speaks to a larger, primarily Dutch audience, thereby evoking membership of and addressing different communities at the same time.

7. Planning for the Future

At present, Cemetery Tongerseweg is again undergoing changes, as outlined in the current business plan for the cemetery (drawn up by the municipal administration under the responsibility of an elected political leadership (

Gemeente Maastricht 2018)) and in interviews held with the cemetery’s management. The intended changes are a result of three current developments in the Dutch context. First, the number of interments has been decreasing for a number of years, leading to a decline in the need for traditional graves. Second, as society becomes more diverse, there is a need to create space for different burial wishes. Third, the financial regulations around cemeteries in The Netherlands have been affected by the long-standing trend of New Public Management. As many other cemeteries in the country, Cemetery Tongerseweg is expected by the municipal administration to be as much as possible independent of subsidies. This has resulted in precarious economic circumstances for Cemetery Tongerseweg and has increased the need of defining new communities that wish to be interred in and thus continue to finance the cemetery. The current business plan stipulates the need for investments that result in less maintenance-intensive infrastructure and “an enhanced palette of products”. The income from Islamic and Armenian graves are considered so important that they receive a dedicated mention in the business plan’s financial paragraph (

Gemeente Maastricht 2018, p. 19). All in all, the business plan foresees a financially independent cemetery after the transition period in which the investment has been taking place.

At the same time, it is important to highlight the communicative and negotiating role of the cemetery management in implementing the regulation drawn up by the municipal administration. What we refer to here, summarily, as “cemetery management” is a surprisingly multilayered, hierarchical structure. At the level of the municipality, there is one dedicated employee whose main task is cemetery Tongerseweg; in addition, there is a secretary who deals with the day-to-day administration; furthermore, a caretaker whose main responsibility is the arrangement of burials, ash dispersals etc. Finally, there is a workforce of at least four gardeners to take care of the grave digging, greenery etc. For instance, in our interviews, the caretaker of cemetery Tongerseweg stressed his role vis-à-vis Islamic funeral attendees. He detailed how he tries to nudge those funeral attendees to merely begin covering the coffin with earth and let the rest be done by far more efficient machines, with the ultimate goal of reducing costs.

One of the measures outlined in the business plan is to create a “multifunctional mourning and remembrance park,” aimed at attracting and serving a broad clientele. The cemetery is being expanded to the northwest side (see

Figure 8). Here, the cemetery will reserve a space for the installation of a remembrance forest. This forest will expand over the decades, with people planting trees in remembrance of their deceased loved ones. The already existing

Section 2 and

Section 3 are being repurposed. Since 2015, no new graves are rented out in

Section 3, and it is expected that all existing graves can be cleared by 2040, so that the section can be changed into a field for scattering ashes, fields for urn graves and potentially a columbarium. In the meantime, existing grave fields that are becoming available will be transformed into meadows with benches and tables. New entrances are planned, and possibilities are explored of constructing a multifunctional pavilion for gatherings other than funeral ceremonies, in a clear bid to extend the functions of the cemetery to include recreation. Also, a new Islamic grave field will be constructed. The current Islamic field is nearly full, and with the prediction that the Islamic community in Maastricht will increase in the future, more grave spaces for this particular group are planned. Another grave field is currently being repurposed for members of the Armenian Apostolic community living in Maastricht and the wider Limburg province. Plans have been made to plant low hedges around the field, and to erect a

khachkar (Armenian cross) in the field.

At present, the Armenian community in Maastricht is relatively young. The actual number of deaths in the Armenian community does not yet justify a dedicated grave section. In recent years, only three deaths have taken place. Of these, only one member of the Armenian community has been buried at Cemetery Tongerseweg. This situation compares to the Muslim community in the 1980s, which was also too small for a separate section. In that case, changes in the legal system resulted in a separate section. In the case of the Armenian community, it is economic considerations that have pushed the cemetery management towards planning a dedicated ritual space for them.

Also, the single Armenian headstone that has been placed recently follows the pattern of the Islamic grave described above (cf.

Figure 7 and

Figure 9a,b). The Armenian grave also marks multiple identifications. It does not stand out from other Dutch graves at the cemetery, as it is similar in shape, size and material used. The deceased’s name and dates of birth and death are written in Latin script. At the same time, the large picture,

khachkar and Armenian letters on the grave indicate the Armenian background of the deceased. In front of the tombstone, temporary grave decorations (a signboard saying “Armenia” and a small wooden

khachkar; see

Figure 9b) similarly emphasize his Armenian identity. As a simple, yet distinctive grave, it remains to be seen whether or how this first grave will prove to be a model for future Armenian graves.

With all these new measures, the Cemetery Tongerseweg not only aims to market itself as the one-stop provider of diverse funeral wishes, it also aims at creating funerary demand. The Islamic and Armenian sections as well as the attempts to reshape the cemetery to include more “natural” burial areas all have to be understood in this light as attempts to emphasize the existence of and/or to create new communities to keep the cemetery viable and relevant.

8. Discussion

Cemeteries frequently are public spaces, sometimes walled or fenced-off and closed at night, but otherwise open to all. This does not preclude them from being ritual spaces, as outlined in the Introduction, with specific expectations of behavior during funerals, collective commemoration ceremonies and individual grave visits (

Bachelor 2004;

Francis et al. 2000,

2005;

Kjærsgaard and Venbrux 2016;

Schmied 2002). Of course, not every behavior at cemeteries is ritualized; cemeteries are also popular with tourists and flaneurs, who are nonetheless also expected to behave “properly” and can also be(come) “pilgrims” to certain graves (

Kmec 2020;

Rugg 2000, p. 264;

Venbrux 2010)

We would like to suggest that the inner divisions of Cemetery Tongerseweg over time develop in accordance with

Evans-Pritchard’s (

1940) concept of “segmentary opposition”. The dynamics implied in segmentary opposition make it a very suitable theoretical tool for a diachronic analysis of the cemetery as a ritual space. In the original context, as Evans-Pritchard points out, “The relation between tribes and between segments of a tribe which gives them political unity and distinction is one of opposition” (

Evans-Pritchard 1940, pp. 282–83). A segment can thus be in opposition to another segment, but both segments in turn can join in opposition to a third one. The Calvinists and the Lutherans had each a section; they formed two segments in opposition to each other. This distinction, however, disappeared when they stood as Protestants in opposition to the Roman Catholics. Next, they became a unity as Christians (the hedge separating them was removed) vis-à-vis the Muslims (spatially separated from them) who began to enter the cemetery around that point in time. The weakening of the ranks of the Catholics in the cemetery might in part be resolved by Armenian Christians, with a new section or segment, moving in.

As the Armenian example shows, this may be a win-win situation. There is, nonetheless, the possibility of a “re-pillarization” of Dutch society unintentionally effected by the actions of cemetery planners and managers. Rather than integration (

Krabben 2004), in actual fact, segregation appears to be taking place. What is more, the native Dutch opting for the cemetery decreases, whereas migrants are expected to follow a unilinear trajectory of pillarization as a means of emancipation.

As this article has shown, a cemetery is not only shaped by municipal councils, planners and managers, but it is also inventively customized and cocreated by its users. Our examples show different ways of articulating the position of one’s family (or deceased family member) as “different”: to overcome distinction by emphasis on high office and family unity across confessional divides (

Figure 3) or to transcend distinction by emphasis on common values (

Figure 5) and hybrid identities of migrant and host country culture (

Figure 7 and

Figure 9a,b).

The role of service-providers should not be underestimated either, as the design of individual gravestones is to a large extent predetermined by the funeral industry, but that discussion is beyond our scope here (

Schmitt et al. 2018). This cocreation of space is not only reflecting past and present changing social relations but also has a prospective dimension: the cemetery is an arena, in which people seek to achieve social recognition, visibility and respectability. It constitutes a means to display groupness (

Brubaker 2001) but also social bonds across groups. In an increasingly plural society, cemeteries continue to provide “order” and may thereby contribute to a “re-pillarization” or segregation.

We propose to view Cemetery Tongerseweg not as one single space but as a multitude of overlapping (ritual) spaces, just as society is not uniform but a multitude of intermeshed imagined and interpretive communities. The early nineteenth French “egalitarian” ideology did not, contrary to popular assumptions, seek to dissolve all communities in one large citizenship but rather encouraged emancipation and identity claims—while simultaneously aiming at building an overarching rational society. We find similar dialectics at work today, where diversity and integration are promoted concurrently. What is happening in Cemetery Tongerseweg is that it creates, builds, evokes and represents as well as relativizes and backgrounds communities; the cemetery is thus an arena of and for society.

Cemetery Tongerseweg is thus a hybrid space, on the one hand, a rigorously rational, economically minded administrative infrastructure, and on the other hand, emotionally charged at an individual as well as collective level. To use (

Tönnies [1887] 2001) ideal-types, the cemetery is clearly not just mirroring (rational) society but is also addressing (affective, normative) communities.

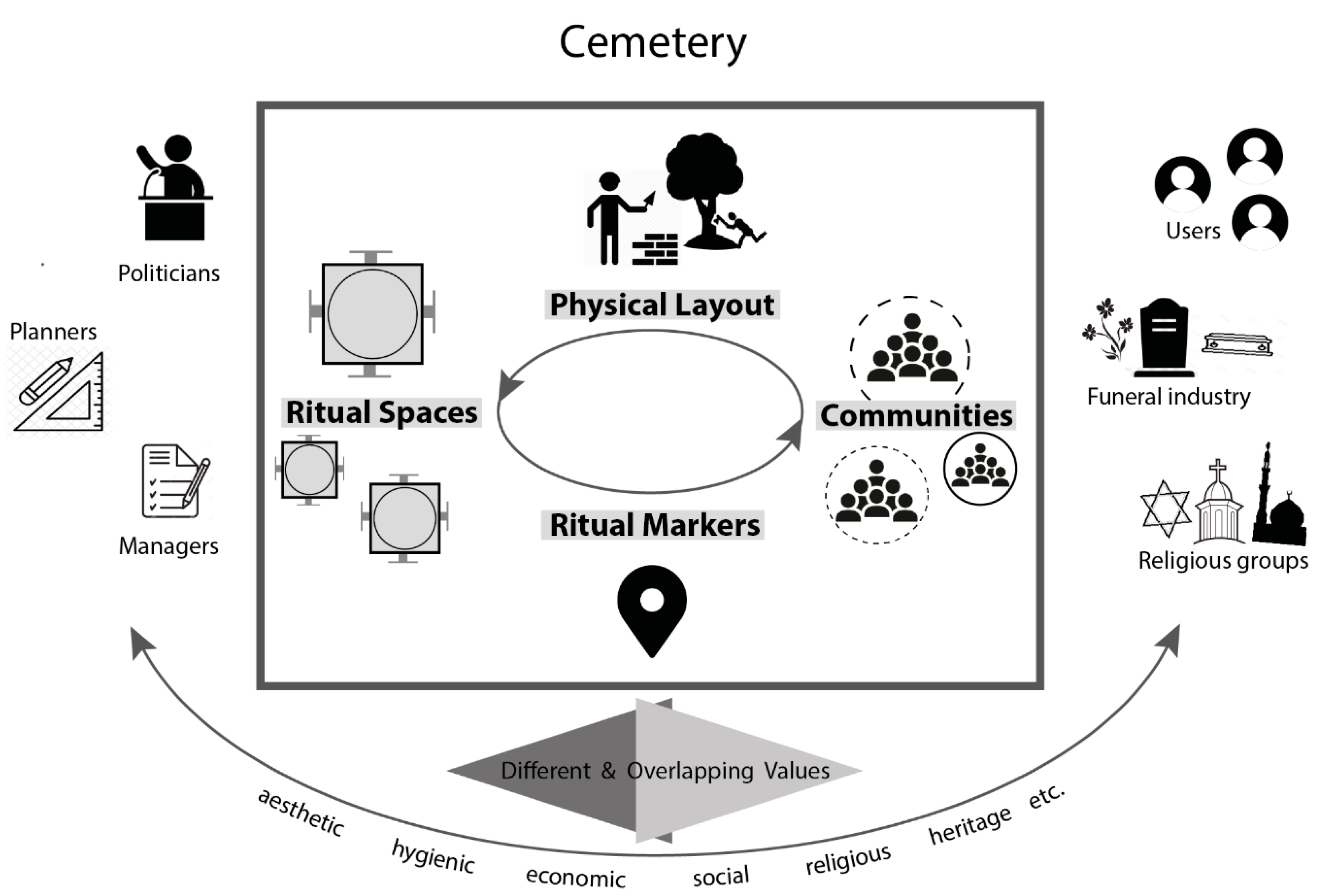

A model needs to be built to illustrate that and how ritual spaces and communities shape each other. The cemetery is the arena in which this is taking place; planners and users with their respective allies are cocreators of the ritual spaces in a cemetery. All of this goes beyond the opposition between the passive mirror analogy and the depiction of the cemetery as an idealized compensatory world that can be found in literature.

Building a model that gets the balance right is by no means easy. The required model needs to have explanatory value through idealization as well as enough detail to capture the complexities of cocreation. The following “Arena Model” of cemeteries as dynamic ritual spaces strikes in our view the desired balance and captures our discussion (

Figure 10):

Understanding ritual space is a complicated matter because the actors and factors engaged in processes of cocreating a ritual space are diverse and complex; moreover, we should view cemeteries as an ensemble, a plurality of ritual spaces. As

Figure 10 shows, the causality (if that is not the wrong word entirely) goes both ways, or rather runs in a circle: cemeteries as an ensemble of ritual spaces are reliant on pre-existing communities, but they also evoke, produce and maintain communities. And, to complicate things further, not only does the physical layout codetermine the ritual space at the disposal of its users, but the users respond and cocreate ritual space in placing a wide range of ritual markers (e.g., gravestones and semipermanent or transitory ritual props that can enhance, but also mitigate or even contradict, the communities created by the spatial layout).

All of this shows how different stakeholders and their allies cocreate ritual spaces in the cemetery by means of permanent, semi- or nonpermanent performative acts that range all the way from expansive gestures such as erecting walls or laying out paths to the smaller, less permanent performative acts such as the placement of a prayer bead.

9. Conclusions

At the end, it is time to look back: with an integrated approach that combines strategies from the tradition of symbolic anthropology and history, we have traced the development of a specific cemetery, Tongerseweg in Maastricht (The Netherlands), over the course of two hundred years, and we have suggested a model that can capture the complexities of cocreating the cemetery as an internally diverse ritual arena (in the sense of ritual space-in-potentiality).

In line with our approach, the method relies on thick description; if we were to locate our research on a spectrum between idiographic and nomothetic approaches, it would definitely stay close to the idiographic end. In what sense, then, can our results be said to have a more general applicability and where are the limitations? Obviously, our research project has focused on a highly complex, culturally diverse society. Also, the existence of different professional and nonprofessional roles bearing on Cemetery Tongerseweg has been taken as a given. Clearly, not all societies are so complex and culturally diverse, and not all societies have so clearly differentiated professional and nonprofessional roles. In short, the same issues may not arise in less diverse and less differentiated societies, and they may not arise where cemeteries are not constructed to aggregate different groups in society as Cemetery Tongerseweg was, in an effort to build a municipal cemetery in a largely Roman Catholic society following French regulations and expectations at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Having said that, the applicability of the arena model does extend beyond the specific case of this cemetery, for contingent historical reasons. Since the late eighteenth-century, Enlightenment inspired rulers and administrations all over Europe proposed a new spatial concept of burial grounds. Driven by hygienic concerns and scientific modes of management and rational organization, these reform movements sought to replace monoconfessional church-owned graveyards with modern cemeteries of a supraconfessional impetus. In France, Prussia, Austria, Russia and many other states, the symmetrical outlook of burial sites became a visible marker of progress and modernization. This benchmark of best practice was not implemented everywhere, of course. However, in expanding urban areas, it became the standard with some regional variations. The Maastricht case shows an adaptation of this pattern.

Where does the applicability of our model end? This is hard to tell in the abstract. As we have shown, the model derives from the specific case of Tongerseweg Maastricht. It certainly applies to other cemeteries in Europe. Further research would be needed to tell whether or not the Arena Model of ritual space is applicable further afield, and which changes would be necessary for it to be heuristically and analytically useful in different circumstances.

5