Abstract

The presence of Apabhraṃśa in tantric Buddhist texts has long been noted by scholars, overwhelmingly explained away as an example of “Twilight language” (saṃdhā-bhāṣā). However, when one looks closer at the vast number of Apabhraṃśa verses in this canon, one finds recurring patterns, themes, and even tropes. This begs for deeper study, as well as establishing a taxonomy of these verses based on their place and use. This paper focuses on a specific subset of Apabhraṃśa verses: “goddess songs” in maṇḍala visualization rituals. These verses are sung by yoginīs at specific moments in esoteric Buddhist ritual syntax; while the sādhaka is absorbed in enstatic emptiness, four yoginīs call out to him with sexually charged appeals, begging him to return to the world and honor their commitments to all sentient beings. When juxtaposed with other Apabhraṃśa verses in tantric Buddhist texts, these songs express an immediacy and intimacy that stands out in both form and content from the surrounding text. This essay argues that Apabhraṃśa is a conscious stylistic choice for signaling intimate and esoteric passages in tantric literature, and so the vast number of Apabhraṃśa verses in this corpus should be reexamined in this light.

Keywords:

tantra; Buddhism; Apabhraṃśa; Prakrit; Old Bengali; dohās; diglossia; language register; ritual language 1. Introduction

Songs and other “inspired utterances” (gītis and udānas) occur in Buddhist literature dating back to the Pāli Canon, and also appear in the tantric texts composed near the end of Buddhism in India around the thirteenth century CE. These later texts attest to numerous verses composed in Apabhraṃśa,1 including dohās quoted from collections attributed to mahāsiddhas,2 verses sung in offering rituals,3 “password” verses,4 verses sung in initiations,5 and verses sung in worship.6 Scholars have long noted this presence of Apabhraṃśa material in the tantric Buddhist canon, usually explaining it away as another example of saṃdhā-bhāṣā, “Twilight language.”7 Davidson addresses the topic at length in his 2002 monograph Indian Esoteric Buddhism. In addition to observing Apabhraṃśa’s links to coded language (saṃdhā-bhāṣā), he makes the crucial point that these tantric Buddhist communities were clearly diglossic.8 Further, he argues that this shows a “clear statement of linguistic distance from the prior centers of power and civilization” (Davidson 2002, p. 273). On this point, Wedemeyer disagrees entirely, insisting that Buddhist tantras originated entirely within mainstream Buddhist institutions, with Apabhraṃśa being merely another instance of “contrived marginality.”9 Wedemeyer also notes that at this point in time, Apabhraṃśa was a “pan-Indic koine” and citing Sheldon Pollock, he proposes that this language was employed to “suggest rural simplicity and joyful vulgarity.”10 While Wedemeyer is correct in noting the semi-artificial and literary character of Apabhraṃśa during this time period, Davidson’s remarks on diglossia11 are far more acute and provide a more nuanced model for approaching the intentionality behind the use of this language. Indeed, rather than a “rural simplicity and joyful vulgarity,” the Apabhraṃśa verses in tantric Buddhist texts instead seem to be reserved for particularly intimate junctures and esoteric contexts, where the speaker speaks in a different language/register and level of discourse entirely. These dohās, “password” verses, and offering and initiation verses, speak directly to their subjects, an intimacy that contrasts markedly with the surrounding text. Indeed, in their use they resemble mantras and dhāraṇīs. This link between language register and esoteric content deserves a deeper analysis,12 and this paper will consider a particular subset of these Apabhraṃśa verses: “Goddess songs” in creation-stage mandala rituals. In these rituals, a group of four yoginīs call out to the sādhaka with Apabhraṃśa verses, appealing to him sexually and pleading for him to honor his commitments and finish his ritual practice. This trope occurs in the Hevajra Tantra, the Caṇḍamahāroṣaṇa Tantra, the Abhayapaddhati, the Buddhakapāla sādhanā in the Sādhanāmālā, the Kṛṣṇayamāri Tantra, and the Khasama Tantra. The pervasiveness of these verses alongside the other striking examples of Apabhraṃśa in this material (as well as tantric Śaiva works), highlight the need for a new theoretical conceptualization of the use value of Apabhraṃśa in tantric Buddhist texts.

2. Sanskrit Precedents: The Guhyasamāja Tantra and Kālacakra Tantra

As Harunaga Isaacson notes, the prototype for these Goddess songs is in the Guhyasamāja Tantra.13 The Guhyasamāja Tantra is unquestionably preeminent within the “Mahāyoga” stratum of tantric Buddhist texts, and can be dated to the 8th century CE at the earliest.14 The Guhyasamāja Tantra’s popularity is attested by the sheer number of commentaries composed in India and Tibet, and particularly in the Ārya school of exegesis the Guhyasamāja Tantra and its commentaries can be used to interpret the tantras as a whole.15 Furthermore, the Guhysamāja Tantra in particular is important for introducing transgressive sexual and alimentary practices into tantric Buddhist traditions.

The relevant verses in the Guhyasamāja Tantra are located in the seventeenth chapter, which, as Matsunaga notes, was probably appended after the composition of the first twelve chapters.16 These verses (17.72–5) model similar passages in later texts in terms of content as well as the broader ritual syntax and context. They occur after an extended passage of dialogue between the assembled Bodhisattvas and Buddhas concerning the secret mantra syllables, after which all of the assembled Bodhisattvas fall silent while the Buddhas “dwell in the vajra wombs of the consorts of Body, Speech, and Mind of all Buddhas.”17 While the Buddhas are dwelling in emptiness in this way, a group of four goddesses call out to the Buddha Vajradhara with verse:

tvaṃ vajracitta bhuvaneśvara sattvadhāto trāyāhi māṃ ratimanojña mahārthakāmaiḥ |kāmāhi māṃ janaka sattvamahāgrabandho yadīcchase jīvitum adya nātha ||(Māmakī)

O Vajra Mind, Lord of the World, Abode of Beings, Knower of the Mind of Passion, Save me with desires for the Great Goal!Love me now, O Father, Friend to the Great Multitude of Beings, if you want [me] to live, O Lord.

tvaṃ vajrakāya bahusattvapriyāṅkacakra buddhārthabodhiparamārthahitānudarśi |rāgeṇa rāgasamayaṃ mama kāmayasva yadīcchase jīvitum adya nātha ||(Buddhalocanā)

O Vajra Body, Host of Dear Ones to all Beings, Beholding the Welfare that is the Supreme Goal, Awakening, the Goal of Buddhas.Passionately desire my pledge of passion now, if you want [me] to live, O Lord.

tvaṃ vajravāca sakalasya hitānukampī lokārthakāryakaraṇe sadā sampravṛttaḥ |kāmāhi māṃ suratacarya samantabhadra yadīcchase jīvitum adya nātha ||(Vajranetrī)

O Vajra Speech, Compassionate for the Benefit of the World, always doing one’s duty for the Sake of the World.O Samantabhadra, amorous in conduct, love me, if you want [me] to live, O Lord.

tvaṃ vajrakāya samayāgra mahāhitārtha sambuddhavaṃśatilakaḥ samatānukampī |kāmāhi māṃ guṇanidhiṃ bahuratnabhūtaṃ yadīcchase jīvitum adya nātha || (17.72-5)18(Vajradayitā)

Immediately after these verses, the tathāgata Vajrapāṇi enters a samādhi, and then enters into union with the consort of all Buddhas. The entire universe becomes permeated with the seed of the Vajra pledges (samaya); the body, speech, and mind of all Buddhas. Ultimately, all beings are consecrated as Samantabhadra (Samantabhadra being the primordial Buddha in this esoteric tradition).19 It is significant that this passage resembles a visionary sādhanā, particularly when compared to a similar passage in the Kālacakra Tantra and its commentary, the Vimalaprabhā. The Kālacakra Tantra is particularly significant for being the last Buddhist tantra of its class composed in India (early 11th century).20 Furthermore, the Vimalaprabhā was so influential that it “served as the basis for all subsequent commentarial literature of that literary corpus.”21 The relevant verses appear in the fourth chapter, on sādhanā. The Vimalaprabhā divides this chapter into five “subchapters” (Skt: uddeśa, “explanation”), and we will focus on the third uddeśa, “The Origination of the Deities of Prāṇa.”22 The section begins with a quotation from the Kālacakra Tantra:O Vajra Body, Foremost in Pledges, Whose Goal is Great Welfare, Ornament of the Assembly of Perfect Buddhas, Equitably Compassionate.Love me, the Reservoir of Virtues, Containing Endless Jewels, if you want [me] to live, O Lord.

hoḥkārādyantagarbhe samasukhaphalade kāyavākcittavajraṃprajñārāgādrutaṃ tacchaśinam iva vibhuṃ vajriṇaṃ cekṣayitvā |gītaṃ kurvanti devyas tvam api hi bhagavan sarvasattvopakārīasmān rakṣā hi vajrin tridaśanaraguro kāmakāmārthinīś ca || 50 ||23“The vajras of the body, speech, and mind are in the beginning, end, and middle of the syllable hoḥ, which brings forth immutable bliss as a result. Having considered the lord vajrī as the moon, melted by passion for the wisdom [being], the goddesses sing, “Bhagavan, you are the benefactor of all sentient beings. O vajrin, the spiritual mentor of gods, protect us, desirous of pleasure.”24

This verse has many of the motifs we will see in the following texts, particularly where the goddesses sing out to the vajrin after seeing him “melted.” In response, these lustful goddesses attempt to draw him out of his enstatic dissolution, by appealing to his Buddhist “ego.” Furthermore, the Vimalaprabhā contextualizes this verse by citing other explicit verses from the “mūla tantra”, which illustrate the themes from the Guhyasamāja verses, as well as the other texts, discussed below:

locanā ‘haṃ jaganmātā niṣyande yogināṃ sthitā |me maṇḍalasvabhāvena kālacakrottha kāma mām ||I am Locanā, the mother of the world, present in the yogīs’ emission.Kālacakra, arise with the nature of my maṇḍala and desire me.māmakī bhaginī cāhaṃ vipāke yogināṃ sthitā |me maṇḍalasvabhāvena kālacakrottha kāma mām ||I am Māmakī, a sister, present in the yogīs’ maturation.Kālacakra, arise with the nature of my maṇḍala and desire me.pāṇḍarā duhitā cāhaṃ puruṣe yogināṃ sthitā |me maṇḍalasvabhāvena kālacakrottha kāma mām ||I am Pāṇḍarā, a daughter, present in the spirit of yogīs.Kālacakra, arise with the nature of my maṇḍala and desire me.tāriṇī bhāgineyāhaṃ vaimalye yogināṃ sthitā |me maṇḍalasvabhāvena kālacakrottha kāma mām ||I am Tāriṇī, a wife, present in the yogīs’ purity.Kālacakra, arise with the nature of my maṇḍala and desire me.śūnyamaṇḍalam ādāya kāyavākcittamaṇḍalam |spharayasva jagannātha jagad uddharaṇāśaya ||25O Protector of the world, whose intention is to deliver the world, perceiving an empty maṇḍala,expand the maṇḍalas of the body, speech, and mind.26

In these latter verses, there are numerous similarities with the verses from the Guhyasamāja Tantra. However, the sexual appeals of the yoginīs are supplemented with pleas for the Buddha Kālacakra, to emit the maṇḍalas and thus finish the sādhanā. In the following texts, these appeals also include an appeal for the sādhaka to remember his vows of compassion for all sentient beings. Both of these texts, the Guhyasamāja Tantra and Kālacakra Tantra, bracket in both dating and content late Indian anuttarayoga27 tantric Buddhist textual production. While the verses from the Guhyasamāja Tantra serve as the prototype for the Apabhraṃśa verses discussed in the remainder of this paper, the Kālacakra Tantra (and Vimalaprabhā) explicitly contextualizes them within the context of sādhanā. Specifically, these verses occur in the “creation stage” (Skt: utpattikrama) sadhana, where the practitioner recreates himself in the image of the text’s tutelary deity. After the practitioner dissolves into emptiness, the four goddesses call out to the sādhaka to arise out of this slumber, desire them, and complete the sādhanā. This ritual syntactic trope is underscored throughout the balance of this paper, with similar themes and vocabulary in the Apabhraṃśa verses. This begs the question: if this motif is commonplace in tantric Buddhist ritual syntax with Sanskrit exemplars, why are the verses in the following texts composed in Apabhraṃśa? This question will be revisited at the end of this paper.

3. The Hevajra Tantra

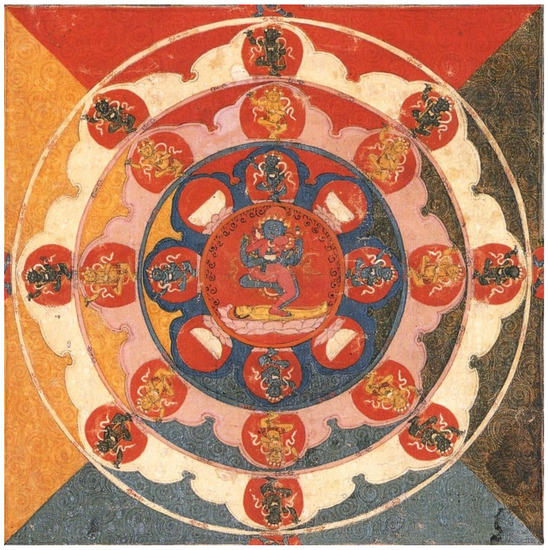

The Hevajra Tantra (dated to the 9th–10th century CE28), attests a great number of Apabhraṃśa verses, from verses used in offering rituals,29 rich descriptions of gaṇacakra rituals,30 encapsulations of tantric theory,31 “uplifting” encouragements,32 as well as a dohā attributed to the mahāsiddha Saraha.33 Within doxographies of tantric Buddhist texts the Hevajra Tantra is commonly classed within a different strata than the Guhyasamāja Tantra, i.e., Yoginī tantras as opposed to Mahāyoga tantras.34 As their name implies, the maṇḍalas of these tantras are overwhelmingly populated by goddesses and yoginīs, especially significant since they sing the Apabhraṃśa verses considered below. In the Hevajra Tantra the maṇḍala visualization instructions appear in the fifth chapter of the second half of the text, and model many of the key elements found in the following texts. After Buddha, Hevajra describes the structure of the maṇḍala (Figure 1) and how the sādhaka should visualize himself at its center surrounded by eight yoginīs, as Hevajra and his consort “dissolve out of great passion.” Thereupon, a subgrouping of four yoginīs urge35 him, with various songs, to return to the world out of his meditative state (samādhi):36

After these verses, the practitioner concludes the remainder of the ritual. These verses are clearly modelled on the verses sung by yoginīs in the Guhyasamāja Tantra; they both consist of four yoginīs or goddesses making sexual appeals to the tantric Buddha; however they also share with the Kālacakra Tantra the additional appeals to the Buddha to finish their practice. Furthermore, these verses all appear in various Hevajra sādhanās. In all five surviving sādhanās of Saroruha’s (Saraha’s) Hevajra lineage, these Goddess’ songs are all included or mentioned, along with other important Apabhraṃśa verses, in the Hevajra Tantra.40 These Goddess’ songs also appear in Ratnākaraśānti’s Bhramaharanāma Hevajrasādhana and in an ancillary sādhanā in the Kṛṣṇayamāri Tantra.41 In his commentary on Ratnākaraśānti’s text, Isaacson notes that the language choice for these Goddess’ songs is standard in the Yoginī tantra tradition, observing that “this should probably be seen as related to the concept in the Śaiva tradition of Apabhraṃśa as the language of direct, intense, mystical revelation by the yoginīs, and perhaps also simply to the fact that women (and particularly women supposed to be of lower social status) would have been not normally expected to speak Sanskrit.”42 Isaacson is certainly correct, and is probably referring to the Krama Mahānayaprakāśa of Śitikaṇṭha, and perhaps also the Mahārthamañjarī. It is also notable that Apabhraṃśa verses appear in Abhinavagupta’s Tantrasāra and Parātrīśika-vivaraṇa.43 There does seem to be a connection, underscored by the persistent choice of Apabhraṃśa for these Goddess songs in the following texts.uṭṭha bharāḍo karuṇamaṇḍa Pukkasī mahu paritāhiṃ |mahāsuajoe kāma mahuṃ chaḍḍahiṃ suṇṇasamāhi ||Arise, O Bhagavān, whose nature is Compassion! Save me, Pukkasī.I desire the union of Great Bliss, so abandon the Samādhi of Emptiness.tohyā vihuṇṇe marami hahuṃ uṭṭehiṃ tuhuṃ Hevajja |chaḍḍahi sunnasabhāvaḍā Śavaria sihyāu kajja ||37Without you I die, arise O Hevajra!Abandon the state of emptiness and fulfill Śavarī’s desires.loa nimantia suraapahu suṇṇe acchasi kīsa |hauṃ Caṇḍāli viṇṇanami tai viṇṇa ḍahami na dīsa ||Summon forth the world, O Amorous Lord! Why do you dwell within emptiness?I, Caṇḍālī, beg you, for without you I cannot perceive the world.indīālī uṭṭha tuhuṃ hauṃ jānāmi ttuha cittaḥ |ambhe Ḍombī cheamaṇḍa mā kara karuṇavicchittaḥ ||38O Sorcerer, arise! I know your mind.We Ḍombīs are cunning women, do not cut off your compassion.39

Figure 1.

Hevajra and yoginīs. Among the eight are the four who sing out to Hevajra with songs: in the upper-left is Caṇḍālī, upper-right Ḍombī, lower left Śavarī, and lower-right Pukkasī. (Himalayan Art Resource, Item 444).

4. The Caṇḍamahāroṣaṇa Tantra

A similar pattern occurs in the Caṇḍamahāroṣaṇa Tantra. The Caṇḍamahāroṣaṇa Tantra is a comparatively late Yoginī tantra composed centuries after the Hevajra Tantra, probably in late 13th century Nepal.44 The relevant Apabhraṃśa passages in this text occur in the fourth chapter, the “deity” chapter. Here, the Buddha Caṇḍamahāroṣaṇa describes the maṇḍala ritual, and how, after having visualized oneself as Caṇḍamahāroṣaṇa (Figure 2), one should visualize eight yoginīs surrounding him. Then, after “[inviting] the coming forth of Wisdom,” four yoginīs call out to him in song:45

pahu maitrī tu vivarjia hohi mā śunnasahāva |tojju viyoe phiṭumi sarve sarve hi tāva ca ||(Mohavajrī)

O Pervader, do not abandon Love, and be not by nature Empty!Without you I perish, and each and every thing as well.

ma karuṇācia iṭṭahi pahu mā hohi tu śunna |mā mojju deha sudukkhia hoi hai jīva vihuna ||(Piśunavajrī)

Do not abandon the mind of Compassion, O Pervader, and be not Empty!If you do, my suffering body will be devoid of life!

kī santu harisa vihohia śunnahi karasi paveśa |tojju nimantaṇa karia manua cchai lohāśeṣa ||(Rāgavajrī)

Why, O Accomplished One, do you enter Emptiness to give pain to Joy?The entire world rests in your heart, calling upon you.

yovanavuṇttim upekhia niṣphala śunnae ditti |śunnasahāva vigoia karahi tu mea sama ghiṭṭi ||(Īrṣyāvajrī)

Do not neglect youth with the fruitless view of Emptiness.Despise the empty nature and embrace me.46

Figure 2.

Caṇḍamahāroṣaṇa mandala. This portrayal is slightly different from what is prescribed in the Caṇḍamahāroṣaṇa Tantra; the deities are rotated 90 degrees clockwise. Clockwise from Top left: Piśunavajrī, Rāgavajrī, Īrṣyāvajrī, Mohāvajrī. (Himalayan Art Resource, Item 90915).

After hearing these verses,47 “as if in a dream” (svapneneva idaṃ śrutvā), the practitioner awakens and then runs to each yoginī in turn, and makes love to them while visualizing himself in different forms. Ultimately, the practitioner dissolves the entire maṇḍala and self-affirms his accomplishment in his practice.48 As in the maṇḍala ritual in the Hevajra Tantra, here the practitioner undertakes preparatory visualizations, and the yoginīs sing out to him to draw him out of his enstatic dream. After hearing these songs, the practitioner finishes the ritual, and by attaining the form of Caṇḍamahāroṣaṇa he has finished creation-stage practice.

5. The Buddhakapāla Tantra

The following verses occur in texts associated with the Buddhakapāla Tantra.49 In the commentary, the Abhayapaddhati, these verses appear in the seventh chapter, called the “Generation of Heruka and his maṇḍala” (maṇḍala-herukotpatti-bhāvanā-ākhyā).50 Furthermore the same verses also occur in a similar maṇḍala ritual in the Sādhanāmālā. The seventh chapter of the Abhayapaddhati is a long description and explication of this maṇḍala ritual (Figure 3). After an extended passage, we reach the trope and motif of dissolving into emptiness, described as a liquid. Then out of this liquid, four trembling goddesses (sphuritāś catasro devyaḥ), observing the Lord (prabhum apaśyantyaḥ), with concern for His various previous vows (pūrva-praṇidhi-veśeṣa-āpekṣayā), full-throatedly (sotkaṇṭhya) arouse the Lord with songs:51

kicce ṇiccaa visāagaü loa ṇimantia kāī |taha vattā ṇa jaï sambharasi uṭṭhahiṃ saala visāī ||How can you summon forth the world while lost in despondence?If you do not honor your commitments, the world leaps into despair.kajja appāṇa vi karia pia mā karasu viṇavi citta |bhavabhaa paḍiā saala jaṇu uṭṭhahi joinimitta ||52Doing one’s own duties, O Dearest, do not think conceptually!Worldly beings are falling into existential angst; Arise O Friend of Yoginīs!53pūvvapaï jjaha sambharasi mā kara kājja visāu |taï athaminne saala jaṇu pariavajja gaüsāu ||If you remember your prior pledges, do not neglect your commitments!While you’re absent, worldly beings on the Buddhist path lose their resolve.miche̐ māṇa vi mā karahi pia uṭṭhaï suṇasahāva |kāmahi joiṇi vinda tuhu phiṭṭaü ahavā bhāva ||54Do not think deludedly, O Dear One. Arise O Nature of Emptiness!55Embrace the horde of yoginīs, otherwise you maim the world.56

Figure 3.

Buddhakapāla surrounded by yoginīs within a maṇḍala. (Himalayan Art Resource, Item 88556).

Awakened by these songs, the practitioner then visualizes a hūṃ̐ syllable transforming into Śrī Heruka, and the following lines describe his appearance in great detail.57 Immediately following this visualization of Heruka, both sādhanās then describe a great maṇḍala populated with yoginīs, for the practitioner to visualize, along with other mainstays of creation-stage practice.58 At the end of the sādhanā in the Sādhanāmālā, the practitioner recites the Buddhakapāla mantra, and the text states that after six months of consistent Buddhakapāla practice, yogins attain success, “here there is no doubt.”59 The similarities with the verses from the Hevajra and Caṇḍamahāroṣaṇa Tantras are clear, underscoring that this is a ritual syntactic trope in tantric Buddhist practice.

6. The Kṛṣṇayamāri Tantra: Anuyoga and Mahāyoga

The final sādhanās appear in a text that does not easily fit into our received classification standards for tantric Buddhist texts. The Kṛṣṇayamāri Tantra seems to straddle both canons of the Mahāyoga tantras and Yoginī tantras.60 This ambiguity is made clear in its name; Kṛṣṇayamāri is closely related to the wrathful Buddha Yamāntaka/Vajrabhairava. As such, the Kṛṣṇayamāri Tantra would seem to be more accurately classified as a Mahāyoga tantra, a fact corroborated by its maṇḍala, comprising a majority of male Yamāris with four yoginīs (Figure 4).61 This is a clear contrast with the maṇḍalas of the previous texts in which yoginīs predominate; however, here as well, yoginīs call out to the practitioner in Apabhraṃśa verses. In addition, while the first sādhanā discussed here (anuyoga) exhibits the same ritual trope seen in the previous texts, the second sādhanā (mahāyoga) significantly subverts it. These Apabhraṃśa verses appear in the root verses of the Kṛṣṇayamāri Tantra, the anuyoga verses in the seventeenth chapter and the mahāyoga verses in the twelfth chapter.62 Chapter seventeen begins with the Buddha visualizing different Buddha-forms (buddhabimbaṃ), and then the text declares that the practitioner becomes the cakra-bearer by the practice of the four [Vajra] songs (associated with the four yoginīs).63 On the other hand, chapter twelve begins with the Buddha entering into different meditative concentrations (samādhi), each associated with one of the text’s four yoginīs (Vajracarcikā, Vajravārāhī, Vajrasarasvatī, and Vajragaurī), and thereupon recites each yoginī’s specific verse.64 However, the actual contextualization of these verses within detailed sādhanā instructions does not appear in the root verses. Instead, they are provided in the commentary composed by Kumāracandra.

Figure 4.

Kṛṣṇayamāri maṇḍala. In the center is the figure Yamāntaka/Dveṣavajrayamāri. Encircling him are the eight other yamāris: in the East Mohavajrayamāri, in the South Piśunavajrayamāri, in the West Rāgavajrayamāri, and in the North Īrsyāvajrayāmari. Between them in the intermediate directions are Mudgarayamāri, Daṇḍayamāri, Padmayamāri, and Khadgayamāri. In the corners outside of this circular array are the yoginīs, Vajracarcikā, Vajravārāhī, Vajrasarasvatī, and Vajragaurī, according to Kumāracandra’s description (Rinpoche and Dvivedī 1992, pp. 1–4, 8). (Himalayan Art Resource, Item 65464).

Anuyoga is the second phase of the four-fold yoga, defined in the root verses as the “arising of the stream of Vajrasattva” (after the generation of Vajrasattva in the first phase, “yoga”).65 Anuyoga begins with summoning and worshipping the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, and afterwards one visualizes the maṇḍala and numerous Sanskrit syllables stationed throughout. After dissolving the maṇḍala, one sees Vajrasattva, after which the four yoginīs appear. An important note here is that each of these yoginīs (Vajracarcikā, Vajravārāhī, Vajrasarasvatī, and Vajragaurī) are associated with long-standing Buddhist meditative states: loving kindness (maitrī), compassion (karuṇā), empathetic joy (muditā), and equanimity (upekṣā). These yoginīs then sing the verses sung by the Buddha at the beginning of chapter seventeen.66

uṭṭha bharāḍaü karuṇākoha |tihuaṇa saalaha pheḍahi moha ||(Vajracarcikā)

Arise, O Bhagavan, whose feigned wrath is compassion.Cut the delusion of the material world!

e caumāra parājia rāula |uṭṭha bharāḍā citteṃ vaüla ||(Vajravārāhī)

You’ve overcome the four Māras, O Royal One.Arise O Bhagavān, [my] mind is stricken.

loaṇimanti acchasi suṇṇe |uṭṭha bharāḍā loaha puṇṇe ||(Vajrasarasvatī)

Summon forth the world, you who dwells in emptiness.Arise O Bhagavan, by the merit of the world!

kaï tu acchasi sunaho viṃtti |bodhisahāva loaṇimaṃti ||67(Vajragaurī)

Why do you dwell in emptiness?O Nature of Enlightenment, summon forth the world!68

Immediately following these verses, the practitioner visualizes more syllables and the sādhanā culminates in one becoming the Buddha Dveṣayamāri.69 The next phase of the four-fold yoga is “atiyoga,” after which the practitioner enters the final phase of the four-fold yoga, “mahāyoga.” While the verses in anuyoga display the same conventions observed in the previous texts, the sādhanā of mahāyoga significantly subverts them. Mahāyoga is defined as the “entrance to the gnosis-cakra (jñāna-cakra), tasting its nectar, as well as the Great Worship and Praise.”70 In this sādhanā the practitioner beseeches the Buddhas for consecration, visualizes the assembly of Yamāris and yoginīs with their tutelary Buddhas, and engages in more subtle yoga within the visualized maṇḍala. Thereupon, the practitioner takes on the face or form (Skt. mukhena)71 of the maṇḍala’s four yoginīs in turn, and worships the maṇḍala with the songs uttered by the Buddha in chapter twelve of the root text:72

aḍeḍe kiṭṭayamāri guru raktalūva sahāva |haḍe tua pekhia bhīmi guru chaḍḍahi koha sahāva ||(Vajracarcikā)

A ḍe ḍe73 Black Yamāri Guru, you are wrathful in form and nature.Seeing you I grow frightened, O Guru, abandon this wrathful nature.74

païṇaccaṃte kaṃvi aï saggamaccapāālu |kiṭṭa bhinnāñjaṇa kohamaṇu ṇaccahi tuhu ve ālu ||75(Vajravārāhī)

You dance and upend everything in heaven, on earth, and in the underworld.Dark like black eyeliner, you dance like a Vetāla, O Fierce One.

kālākhavva pamāṇahā bahuviha ṇimmasi rua |vajjasarāssaï viṇṇamami ṇaccahi tuha mahāsuharua ||(Vajrasarasvatī)

You are black, short in stature, and take on various forms,You dance and you are of the nature of great bliss, I, Vajrasarasvatī supplicate you.

hrīḥ ṣṭrīḥ manteṇa pheḍahi kehu tihuaṇa bhānti |karuṇākoha bharāḍaü taha kuru jagu pekkhanti ||76(Vajragaurī)

With the mantra hrīḥ ṣṭrī, cut the delusion of the three realms!Therefore, O Great Lord, Whose Wrath is Compassion, do [your duties!], [for] the world looks on

In the root verses of chapter twelve, the Buddha recites these verses after entering the respective samādhis of the four yoginīs (i.e., the four brahmāvihāras), and in this sadhana, the practitioner does as well. Thus, the long-standing Buddhist brahmavihāras are imagined as yoginīs in a tantric context. Afterwards, the practitioner prostrates before each of the maṇḍala’s Yamāris and the ritual is complete.

7. Conclusions

“The Sanskrit in which the Tantras are written, is, as a rule, just as barbarous as their contents.”—Maurice Winternitz (1933, p. 401)

Scholars have long observed that tantric literature has an affinity for nonstandard language. John Newman has observed that the Sanskrit in the Kālacakra Tantra “is not Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit (Buddhist Ārṣa), nor is it simply substandard Sanskrit. It is Sanskrit into which various types of nonstandard forms have been intentionally introduced.”77 Furthermore, he accepts Puṇḍarīka’s explanation for this, specifically that these linguistic variations and “mistakes” are not due to ignorance or incompetence, but rather intentionally included to counter excessive attachment to “correct language,” and teach disciples to rely on inner meaning rather than the strict grammatical form.78 However, these variations and “mistakes” also became standard and expected in tantric literature; Szántó observes that the author(s) of the Catuṣpīṭha Tantra went out of their way to use ungrammatical forms to such an extent that the text itself is almost indecipherable, even to contemporary commentators.79 This use of nonstandard Sanskrit also reflects the general Buddhist resistance to Brahmanical religion and its concomitant linguistic ideology. An affinity for nonstandard Sanskrit is also a feature of Śaiva tantric texts. Remarking on the tantric Śaiva Siddhayogeśvarīmata, Törczök notes that “the more the language of the text differs from the classical Sanskrit of the orthodox, the more esoteric its teaching is.”80 Furthermore, in the Buddhakapāla Tantra, many of the chapters conclude with a capstone dohā in Apabhraṃśa. These are very direct, colloquial, and didactic verses that encapsulate (or challenge) the chapter’s content.81 On the other hand, in the Abhidhānottara Tantra, a band of assembled ḍākinīs delightedly sing to the practitioner in ecstatic Apabhraṃśa verse upon their successful initiation.82 As such, there is a clear intentionality behind the language register in tantric texts, allusive yet direct, used for emphasis, directness, and intimacy.

Within the context of these maṇḍala visualization rituals, these “Goddess songs” take on an extremely intimate register, expressing mingled sexual and altruistic passion on the part of the yoginīs. Within the liminal space of the maṇḍala, these yoginīs call out to the practitioner to embrace them and work for the benefit of all sentient beings, both sine qua non in tantric Buddhism (wisdom and compassion). This intentional language choice may reflect their social position, as Isaacson notes, however it also recalls the sociolinguistics of Sanskrit drama. In Sanskrit drama, one’s social positionality is indexed by their language register, with high class men speaking Sanskrit and women and social inferiors speaking varieties of Prakrit.83 The link between Prakrit and women in Sanskrit drama is clear, yet when juxtaposed with the other Apabhraṃśa verses in tantric Buddhist texts, this link is problematized. For example, in the Hevajra Tantra, the male Buddha Hevajra speaks directly to the assembled yoginīs in an Apabhraṃśa verse, to soothe and revive them after they are dumbstruck by his profound teachings.84 This diglossic85 shift between different languages and registers illustrates this intentionality acutely, yet while Wedemeyer is correct in noting the semi-artificial nature of Apabhraṃśa, it can hardly be dismissed as “contrived marginality” as he would insist.86 Instead it communicates an intimacy and directness, similar to the didactic (if allusive) dohās of Saraha and other mahāsiddhas. However, these verses are far more diverse and numerous throughout tantric Buddhist literature than these dohās, and they possess their own linguistic currency, similar to, but distinct from, mantras or dhāraṇīs.87 These verses and the use of Apabhraṃśa in tantric texts deserves a deeper dedicated study,88 but for the moment we can observe that in this literature Apabhraṃśa is reserved for particularly esoteric or direct intimate contexts.89

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

The Kṛṣṇayamāri Tantra’s seventeenth chapter ends with the text’s four yoginīs singing another Apabhraṃśa song. After the root text defines the four-fold yoga (KYT 17.8-11), Vajrasattva recites the intermediary verses of the chapter, which preach a variety of fairly common tantric Buddhist injunctions (e.g., maintaining loving kindness to all beings (13), not disrespecting the guru (12), respecting women (16), etc.). After hearing Vajrasattva’s speech, “all the assembled Buddhas whose forms were great supreme bliss” became silent and then burst forth with an upsurge of song (udāna).90 These seven verses are an apophatic description of the state of consciousness that arises from the practice of Vajrasattva (vajrasattvaprayogena): astonishing (suvismayam), eternal (śaśvataḥ), and devoid of material elements and bodily experience.91 Inspired by this Sanskrit udāna, Mahācarcikā and the other yoginīs respond with an udāna in Apabhraṃśa:92

ṇimmala śuddhadeho paramānaṃda |

puṇṇassāvego sambandha ||

This Supreme Joy is Stainless and Pure in Body,

It is divorced from both Merit and Sin.93

karuṇācittaṃ acchaï savva |

eku mahādhani tathatā davva ||

All that exists is the Mind of Compassion,

One great treasury of suchness and substance.

paramānanda saï asahāva |

mahāsuha bhāveṃ dhamma sahāva ||

Supreme Joy lacks inherent essence,

The nature of Dharma is Great Bliss.94

ṇaitahi bhaaṇa du pūrṇayāu |

palaaü attīṇaiva sabhāu ||95

Therefore there is neither form, merit, nor sin.

And also neither arising nor pure release.96

These verses do not follow the pattern of the songs from the rest of the texts cited so far, and Bhayani notes are considerably corrupt,97 making them very difficult to translate. These verses also likely presented issues for Kumāracandra, who glosses over only the two most obvious terms from verses twenty-nine and thirty (ṇimmala→nirmala, śuddha), and whose running commentary on verses thirty-one and thirty-two is extremely loose and boilerplate in content.98 These issues aside, these verses are significant for underscoring the connection between Apabhraṃśa verses and yoginīs in this text, and also serve as a capstone for the chapter as a whole. Furthermore, they stand out in the text like a mantra or dhāraṇī, highlighting the significance of this language in tantric Buddhist texts.

References

- Bhattacharyya, Benoytosh, ed. 1928. Sādhanamālā. Baroda: Oriental Institute, vol. II. [Google Scholar]

- Bhayani, H. C. 1997. Dohā-gīti-kośa of Saraha-pāda and Caryā-gīti-kośa: Restored Text, Sanskrit Chāyā and Translation. Ahmedabad: Prakrit Text Society. [Google Scholar]

- Bubeník, Vít. 1998. A Historical Syntax of Late Middle Indo-Aryan (Apabhraṃśa). Amsterdam and Philadephia: John Hopkins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Dalton, Jacob. 2005. A Crisis of Doxography: How Tibetans Organized Tantra during the 8th–12th Centuries. JIABS 28: 115–81. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, Ronald M. 2002. Indian Esoteric Buddhism: A Social History of the Tantric Movement. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, Ronald M. 2005. Tibetan Renaissance: Tantric Buddhism in the Rebirth of Tibetan Culture. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, Ronald M. 2017. Magicians, Sorcerers and Witches: Considering Pretantric, Non-sectarian Sources of Tantric Practices. Religions 8: 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorje, Chog, ed. 2009. Abhayapaddhati of Abhayākaragupta: Commentary on the Buddhakapālamahātantra. Sarnath and Varanasi: Central Institute of Higher Tibetan Studies. [Google Scholar]

- George, Christopher S. 1974. The Caṇḍamahāroṣaṇa Tantra, Chapters I-VIII. A Critical Edition and English Translation. American Oriental Series; v. 56. New Haven: American Oriental Society. [Google Scholar]

- Gerloff, Torsten. 2017. Saroruhavajra’s Hevajra Lineage: A Close Study of the Surviving Sanskrit Works. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Grimes, Samuel, and Péter-Dániel Szántó. 2018. Mahāsukhavajra’s Padmāvatī Commentary on the Sixth Chapter of the Caṇḍamahāroṣaṇatantra: The Sexual Practices of a Tantric Buddhist Yogī and His Consort. Journal of Indian Philosophy 46: 649–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatley, Shaman. 2016. Converting the Ḍākinī: Goddess Cults and Tantras of the Yoginīs between Buddhism and Śaivism. In Tantric Traditions in Transmission and Translation. Edited by David Gray and Ryan Richard Overbey. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Isaacson, Harunaga. 2002. Ratnākaraśānti’s Bhramaharanāma Hevajrasādhana: Critical Edition. Journal of the International College for Advanced Buddhist Studies (国際仏教学大学院大学研究紀要) 5: 151(80)–76(55). [Google Scholar]

- Isaacson, Harunaga. 2007. First Yoga: A commentary on the ādiyoga section of Ratnākaraśānti’s Bhramahara. In Pramāṇakīrtiḥ: Papers Dedicated to Ernst Steinkellner on the Occasion of His 70th Birthday. Edited by Ernst Steinkellner and Birgit Kellner. Wiener Studien Zur Tibetologie Und Buddhismuskunde. Heft 70. Wien: Arbeitskreis Für Tibetische Und Buddhistische Studien, Universität Wien. [Google Scholar]

- Kale, M. R. 2017. The Abhijñānaśākuntalam of Kālidāsa, With Commentary of Rāghavabhaṭṭa, Various Readings, Introduction, Literal Translation, Exhaustive Notes and Appendices. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. First published 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Kalff, Martin Michael. 1979. Selected Chapters from the Abhidhānottara Tantra: The Union of Female and Male Deities. Ph.D. dissertation, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Hong. 2010. The Buddhakapālatantra, Chapters 9 to 14. Sanskrit Texts from the Tibetan Autonomous Region, No. 11. Beijing: China Tibetology Pub. House. Hamburg: Asien-Afrika-Institut. [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga, Yūkei. 1978. The Guhyasamája Tantra: A New Critical Edition. Edited by Shohan. Ōsaka: Tōhō Shuppan. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, John. 1988. Buddhist Sanskrit in the Kālacakra Tantra. JIABS 11: 123–40. [Google Scholar]

- Pollock, Sheldon I. 2006. The Language of the Gods in the World of Men: Sanskrit, Culture, and Power in Premodern India. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rinpoche, Samdhong, and S. S. Bahulkar. 1994. Vimalaprabhā ṭīkā of Kalkin Śrī Puṇḍarīka on Śrī Laghukālacakra-tantrarāja by Śrīmañjusrīyaśas. Saranath and Varanasi: Central Institute of Higher Tibetan Studies, vol. ii. [Google Scholar]

- Rinpoche, Samdhong, and Vrajavallabha Dvivedī, eds. 1992. Kr̥ṣṇayamāritantram, with Ratnāvalīpañjikā of Kumaracandra. Sarnath and Varanasi: Central Institute of Higher Tibetan Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Sankrityayana, Rahul. 1957. Dohākoṣa. Patnā: Vihāra-Rāṣṭrabhāṣā-Pariṣad. [Google Scholar]

- Shastri, Mukunda Ram, ed. 1918. The Tantrasāra of Abhinava Gupta. Kashmir Series of Texts and Studies No. XVII. Bombay: Nirnaya-sagar Press. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, Jaideva, ed. 1988. Parātrīśikā-vivaraṇa: The Secret of Tantric Mysticism. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. [Google Scholar]

- Snellgrove, David. 1964. The Hevajra Tantra—A Critical Study, Part 2: Sanskrit and Tibetan Texts. London: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Szántó, Péter-Dániel. 2012a. Selected Chapters from the Catuṣpīṭhatantra: Introductory study with the annotated translation of selected chapters. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, Balliol College, Oxford, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Szántó, Péter-Dániel. 2012b. Selected Chapters from the Catuṣpīṭhatantra: Appendix volume with critical editions of selected chapters accompanied by Bhavabhaṭṭa’s commentary and a bibliography. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, Balliol College, Oxford, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Tagare, Ganesh Vasudev. 1987. Historical Grammar of Apabhraṃśa. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. First published 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Tanemura, Ryugen. 2015. Guhyasamāja. In Brill’s Encyclopedia of Buddhism. Edited by Jonathan A. Silk, Oskar Von Hinüber, Vincent Eltschinger, Richard Bowring and Michael Radich. Volume 1: Literature and Languages. Leiden: Brill, pp. 326–33. [Google Scholar]

- Thurman, Robert. 1993. Vajra Hermeneutics. In Buddhist Hermeneutics. Edited by Donald Lopez, Jr. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, pp. 119–48. First published 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Törzsök, Judit. 1999. The Doctrine of Magic Female Spirits: A Critical Edition of Selected Chapters of the Siddhayogeśvarīmata(tantra) with Annotated Translation and Analysis. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi, Ram Shankar, and Thakur Sain Negi. 2001. Hevajratantram with Muktāvalī Pañjikā of Mahāpaṇḍitācārya Ratnākaraśānti. Sarnath: Central Institute of Higher Tibetan Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, Vesna. 2001. The Inner Kālacakratantra: A Buddhist Tantric View of the Individual. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, Vesna. 2010. The Kālacakra Tantra: The Chapter on Sādhanā, Together with the Vimalaprabhā Commentary. Treasury of the Buddhist Sciences. New York: American Institute of Buddhist Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Wayman, Alex. 2008. The Buddhist Tantras: Light on Indo-Tibetan Esotericism. London and New York: Routledge. First published 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Wedemeyer, Christian K. 2013. Making Sense of Tantric Buddhism: History, Semiology, and Transgression in the Indian Traditions. South Asia across the Disciplines. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Winternitz, Maurice. 1933. A History of Indian Literature. Calcutta: University of Calcutta, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Mei. 2016. Some Remarks on the Concept of the Yoginī in the Abhayapaddhati of Abhayākaragupta. 東洋文化 96: 107–21. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Apabhraṃśa (apa + √bhraś, “degenerate language”) has two broad meanings. The first is its emic definition, used by grammarians to describe deviations from Pāṇinian Sanskrit (Bubeník 1998, pp. 27, 33–49). This paper will use the term in its etic, analytic sense to describe the stage of late Prakrit (Middle Indo-Āryan) as it evolved into the modern North Indian languages (New Indo-Āryan: Hindusthani, Bengali, etc.) (Tagare [1948] 1987, pp. 1–4). |

| 2 | Many of the chapters of the Buddhakapāla Tantra end in a capstone dohā encapsulating (or challenging) the chapter’s content, e.g., Buddhakapāla Tantra 9.9 and 13.24 (Luo 2010, pp. 5, 32). Both of these verses can be found in an edition of Saraha’s Dohākoṣa (Bhayani 1997, p. 35; Sankrityayana 1957, p. 24). |

| 3 | e.g., Hevajra Tantra II.4.93 (Snellgrove 1964, p. 74). These verses also appear throughout the sādhanās of Saroruha’s Hevajra lineage: Vajrapradīpa (Gerloff 2017, pp. 248, 255, 387, 391), Hevajrasādhanopāyikā (Gerloff 2017, pp. 111–12, 144), Dveṣavajrasādhana (Gerloff 2017, pp. 428–29, 461–62), and the Hevajraprakāśa (Gerloff 2017, pp. 526, 675). |

| 4 | e.g., Catuṣpīṭha Tantra 2.4.101 (Szántó 2012a, pp. 363–64). |

| 5 | e.g., Abhidhānottara Chapter 14. (Kalff 1979, pp. 321–22). |

| 6 | e.g., Catuṣpīṭha Tantra 2.3.108-13 (Szántó 2012b, pp. 123–28). |

| 7 | e.g., (Wayman [1973] 2008, pp. 133–35). |

| 8 | Davidson notes that these tantric traditions arose within multilingual and more importantly multiglossic communities, who were able to navigate between different language registers in different contexts (Davidson 2002, pp. 269–77). In a later article, Davidson considers the historical evidence for non-sectarian magicians and sorcerers, whose traditions were appropriated by later sectarian tantric groups, which is significant in the current context for the tantalizing yet somewhat ambiguous evidence associating them with registers of Prakrit (Davidson 2017, pp. 19–20, 27). |

| 9 | (Wedemeyer 2013, pp. 171, 3–5, 184). |

| 10 | (Wedemeyer 2013, p. 184, Pollock 2006, p. 104). |

| 11 | Diglossia differs from bilingualism in that diglossia refers to the use of different languages for different purposes, whereas bilingualism does not. |

| 12 | This pairing of language register with esoteric content also occurs in tantric Śaiva texts. In the tantric Śaiva Siddhayogeśvarīmata, Törzsök notes that “the more the language of the text differs from the classical Sanskrit of the orthodox, the more esoteric its teaching is” (Törzsök 1999, p. ii). |

| 13 | (Isaacson 2007, p. 301). |

| 14 | As Tanemura explains, the Guhyasamāja Tantra builds off the material of the Sarvatathāgatattvasaṃgraha, itself translated into Chinese in 723 CE (Tanemura 2015, p. 327). |

| 15 | (Thurman [1988] 1993, p. 133). |

| 16 | (Matsunaga 1978, p. xxix). |

| 17 | atha te sarve bodhisattvāḥ tūṣṇīṃ vyavasthitā abhūvan | atha bhagavantaḥ sarvatathāgatāḥ sarvatathāgatakāyavākcittavajrayoṣidbhageṣu vijahāra | (Matsunaga 1978, p. 109). Translations mine. |

| 18 | (Matsunaga 1978, p. 110). Translations mine. |

| 19 | atha bhagavān vajrapāṇis tathāgataḥ sarvakāmopabhogavajraśriyaṃ nāma samādhiṃ samāpannas tāṃ sarvatathāgatadayitāṃ samayacakreṇa kāmayan tūṣṇīm abhūt | athāyam sarvākāśadhātuḥ sarvatathāgatakāyavākcittavajrasamayaśukreṇa paripūrṇo vajrodakaparipūrṇakumbha iva saṃsthito ‘bhūt | athāsmin vajrākāśadhātau ye sattvās trikāyasamayasambhūtās trivajraśriyā saṃspṛṣṭāḥ sarve te tathāgatā arhantaḥ samyaksambuddhās trivajrajñānino ‘bhūvan | tataḥ prabhṛti sarvasattvāḥ samantabhadrasamantabhadra iti sarvatathāgatakāyavākcittavajreṇābhiṣiktā abhūvan || “Then the Blessed Tathāgata Vajrapāṇi entered the samādhi called ‘Vajra glory of the enjoyment of all desires,’ and along with the Samaya circle, enjoyed the Consort of all the Tathāgatas and fell silent. Then the entire spatial realm was permeated with the seed of the samayas of Vajra Body, Speech, and Mind of all Tathāgatas, like a jar filled with Vajra water. At that moment all sentients beings who arise from the samayas of the Three Bodies in the Vajra realm of Space were all touched by the glory of the Triple Vajra and become Buddhas, Arhats, and Perfect Buddhas. From that moment on all sentient beings were consecrated as Samantabhadra by the Vajra of the Body, Speech, and Mind of all Tathāgatas” (Matsunaga 1978, p. 110. Translations mine). |

| 20 | (Wallace 2001, p. 3). |

| 21 | (Wallace 2001, p. 3). |

| 22 | Skt: prāṇadevatotpādamahoddeśa. Translation from Wallace (2010, p. 79). |

| 23 | Sanskrit text from Rinpoche and Bahulkar (1994, p. 178). |

| 24 | Translation from Wallace (2010, p. 73). |

| 25 | Sanskrit text from Rinpoche and Bahulkar (1994, p. 179). |

| 26 | Translation from Wallace (2010, pp. 75–76). |

| 27 | As Dalton argues, this term is an incorrect Western back-translation from the Tibetan rnal ‘byor bla na med pa (Dalton 2005, pp. 160–61). In most scholarship, this is ‘anuttarayoga’. |

| 28 | (Davidson 2005, p. 41). |

| 29 | HT II.4.93 (Snellgrove 1964, p. 74). |

| 30 | HT II.4.2-5 (Snellgrove 1964, p. 62). |

| 31 | HT II.4.71 (Snellgrove 1964, p. 70). |

| 32 | HT II.4.67 (Snellgrove 1964, p. 70). |

| 33 | HT II.5.68 (Snellgrove 1964, p. 84). |

| 34 | As Dalton has shown, the common four-fold doxography of tantric Buddhist texts is best understood as a Tibetan innovation, which crystallized and formalized the looser Indian classification systems (Dalton 2005, pp. 118, 158–62). In particular, Dalton shows that, within India, the category “Yoginī/*Niruttarayoga” tantras became a distinct class of tantras distinct from Mahāyoga in the eleventh century (156). However, while many of the texts classified under this label don’t attest the term “yoginītantra” in their chapter colophons (including the Cakrasamvara, Hevajra, etc.), this is not true of the Buddhakapāla Tantra (Yang 2016, pp. 107–8; Luo 2010, pp. 5, 14, 17–18, 27, 33, 39). This is significant, as the Buddhakapāla Tantra is dated to the ninth or tenth centuries CE, and so predates the classification scheme by one or two centuries (Luo 2010, p. xxxi). |

| 35 | Throughout these texts, the Sanskrit term used is always a derivative of the causative root of √cud, “impel, urge.” |

| 36 | tato vajrī mahārāgād drutabhūtaṃ savidyayā | codayanti tato devyo nānāgītopahārataḥ || (Snellgrove 1964, p. 78). |

| 37 | In his commentary, Ratnākaraśānti glosses “sunnasabhāvaḍā” as “śūnyasvabhāvam, dravarūpatām ity arthaḥ,” roughly translated as “the nature of enlightenment, being the form of reality (drava)” (Tripathi and Negi 2001, p. 202). |

| 38 | HT II.5.20-3 (Snellgrove 1964, pp. 78–80). Translations mine, relying heavily on Ratnākaraśānti’s Muktāvalī (Tripathi and Negi 2001, pp. 201–2). |

| 39 | This verse departs from the others, and its precise interpretation presents some issues. Ratnākaraśānti glosses pāda c: ḍombikā vayaṃ chekā nāgarikāḥ | maṇḍa iti evaṃ jānīha | (Tripathi and Negi 2001, pp. 202–3). |

| 40 | i.e., the Hevajrasādhanopāyikā (Gerloff 2017, pp. 103–4, 111–14); As an explanatory sadhana, the Vajrapradīpā provides a Sanskrit gloss and commentary on these verses (Gerloff 2017, pp. 217–19, 364–65). Furthermore, the Vajrapradīpā also contains more Apabhraṃśa verses sung by yoginīs (Locanā and others), unattested in the Hevajra Tantra, listed under a “mudraṇam” section (Gerloff 2017, pp. 234–35, 375). The verses from the Hevajra Tantra do not appear explicitly in the Dveṣavajrasādhana; however, they are mentioned in passing (Gerloff 2017, p. 417). The mudraṇam verses, however, appear here (Gerloff 2017, pp. 424, 455). The verses from the Hevajra Tantra also appear in the Hevajraprakāśa (Gerloff 2017, pp. 498, 647–50), as well as the mudraṇam verses (Gerloff 2017, pp. 513, 665). These verses are absent from the Hevajra sādhanā in the Sādhanāmālā, however the sādhanā includes two dohās from Saraha’s dohākoṣa (Bhattacharyya 1928, pp. 381–84; Bhayani 1997, p. 49). |

| 41 | (Isaacson 2002, pp. 162–63). For the sādhanā in the Kṛṣṇayamāri Tantra, see Rinpoche and Dvivedī (1992, pp. 140–42). |

| 42 | (Isaacson 2007, p. 301). |

| 43 | These texts are particularly noteworthy, since these verses are cited as capstones at the end of the texts’ chapters and passages, similar to the Buddhakapāla Tantra. E.g., (Shastri 1918, pp. 7, 9, 19, 20, 33, 44, 62, 68, 91 (Tantrasāra)). From the Sanskrit text of the Parātrīśika-vivaraṇa in Singh’s translation and edition: e.g., (Singh 1988, pp. 7, 22–23, 32, 38, 75). |

| 44 | (Grimes and Szántó 2018, p. 651). |

| 45 | (George 1974, pp. 57–61). |

| 46 | (George 1974, p. 61). George’s translations have been edited in places. |

| 47 | One particularly notable element of these verses is their phonology. In contrast to the verses from the Hevajra Tantra and the other verses quoted in this paper, these verses from the Caṇḍamahāroṣaṇa Tantra strictly adhere to the phonological rules of Śaurasenī Prakrit/Apabhraṃśa. In particular, the distinctions between sibilants are respected; the term “śunnasahāva” in the second pāda of the first verse is a clear smoking gun. In contrast, the verses from the Hevajra Tantra attest the term “sunnasabhāvaḍā” in the third pāda of the second verse, while the Abhayapaddhati and Buddhakapāla sādhanā have “suṇasahāva” in the second pāda of the fourth verse. This is noteworthy because all of these texts originated broadly within Northeastern India and Nepal, where Gauḍī phonological features predominate (one of the hallmarks of Gauḍī and modern-day languages from this area is non-distinction and flux between sibilants). Given the Caṇḍamahāroṣaṇa Tantra’s Nepali provenance, this strict adherence to the phonological rules of Śaurasenī is peculiar and distinguishes it from the other texts considered in this essay. |

| 48 | (George 1974, p. 62). |

| 49 | I do not have access to the complete Sanskrit root text. Instead I am relying on the root Tantra’s commentary, the Abhayapaddhati in addition to a Buddhakapāla sādhanā in the Sādhanāmālā. |

| 50 | (Dorje 2009, p. 48). |

| 51 | (Dorje 2009, pp. 52–53). |

| 52 | Bhattacharyya’s Sanskrit chāyā glosses “viṇavi” as “dvayam api” (Bhattacharyya 1928, p. 501). While semantically an argument can be made for this gloss, etymologically “viṇṇa” has a clear Prakrit pedigree as a derivation from vi + √jñā. |

| 53 | Interestingly, the Tibetan translation of the Abhayapaddhati only includes this second verse from among the four original Apabhraṃśa verses in the Sanskrit text: bdag nyid bya ba byas nas ni | stong pa nyid la sems ma mdzad | skye kun srid pa ‘jigs par lhung | rnal ‘byor ma yi grogs po bzhengs ||: “Doing one’s own duties, do not dwell on emptiness. [While] the dreadful being of worldly existence falls, the darling of the yoginī rises” (Dorje 2009, p. 193). Translations mine. |

| 54 | The version in the Abhayapaddhati diverges phonologically in a number of places, e.g., 3cd: taha athaminnaṃ saala jaṇu pamiujja gaavasāu, 4ab: michaṃ māṇa vi mā karahi piucchatta suṇṇahābhāva (Dorje 2009, p. 53). |

| 55 | “suṇasahāva” is undoubtedly a bahuvrīhi compound, meaning “One whose Nature is Emptiness.” However, for the sake of clarity and aesthetics, I have chosen to translate is as “O Nature of Emptiness.” |

| 56 | (Bhattacharyya 1928, p. 501). Translations mine. |

| 57 | (Dorje 2009, pp. 53–54. Bhattacharyya 1928, p. 501). |

| 58 | (Dorje 2009, pp. 54–62. Bhattacharyya 1928, pp. 502–3). |

| 59 | sidhyanti ṣaṇmāsenaiva yogino nātra saṃśayaḥ (Bhattacharyya 1928, p. 503). |

| 60 | Hatley groups this text as a Yoginī Tantra (thus in the same textual stratum as the previous texts), while noting that it is also more commonly considered a Mahāyoga Tantra (Hatley 2016, p. 51; Dalton 2005, p. 155 fn.90). |

| 61 | Respectively: Mohavajrayamāri, Piśunavajrayamāri, Rāgavajrayamāri, Īrsyāvajrayāmari, Dveṣavajrayamāri, Mudgarayamāri, Daṇḍayamāri, Padmayamāri, Khadgayamāri. The yoginīs are: Vajracarcikā, Vajravārāhī, Vajrasarasvatī, and Vajragaurī (Rinpoche and Dvivedī 1992, p. 1). |

| 62 | (Rinpoche and Dvivedī 1992, pp. 122, 78–79). |

| 63 | (Rinpoche and Dvivedī 1992, p. 121). |

| 64 | “pūjāgītam udānayām āsa” (Rinpoche and Dvivedī 1992, pp. 38–39). |

| 65 | “tan niṣyandodayo deva anuyogaḥ pratīyate” KYT 17.9 (Rinpoche and Dvivedī 1992, p. 123). |

| 66 | (Rinpoche and Dvivedī 1992, p. 125). However, the verses in the root verses and the versions in the sādhanā instructions display many phonetic differences. |

| 67 | As in the Buddhakapāla verse 4b, I have chosen to translate this bahuvrīhi term as “Nature of Enlightenment,” cf. fn 55. (Rinpoche and Dvivedī 1992, pp. 121–22). |

| 68 | The Tibetan translation also differs from the original Apabhraṃśa, but far less so. The precise meaning of sunaho viṃtti is unclear, however Kumāracandra glosses the term as “emptiness,” (“śūnyatāyām ity arthaḥ,” Rinpoche and Dvivedī 1992, p. 122). |

| 69 | (Rinpoche and Dvivedī 1992, pp. 124–25). |

| 70 | jñānacakrapraveśaś ca amṛtāsvādam eva ca | mahāpūjā stutiś cāpi mahāyoga iti smṛtaḥ || KYT 17.11 (Rinpoche and Dvivedī 1992, p. 123). |

| 71 | The term mukhena here can possibly be interpreted as meaning that the sādhaka faces each yoginī while reciting the yoginī’s respective verse. However, based on the context from the root verses in chapter twelve where the Buddha explicitly sings these songs after entering into the respective samādhis of each yoginī, I think it is more likely that in the sādhanā of mahāyoga the sādhaka takes on the form of each yoginī by entering it’s the yoginī’s respective samādhi. |

| 72 | As with the anuyoga verses, here too there are many phonological divergences from the versions in the root text (Rinpoche and Dvivedī 1992, pp. 127–28). |

| 73 | The word “aḍeḍe” may be an elaborated Prakrit form of Skt. ari, “enemy” (yamāri = “Enemy of Death”). However, it is also perhaps untranslatable and onomatopoeic, hence in the Tibetan translation it is transliterated (a kyi kyi) (Rinpoche and Dvivedī 1992, p. 154). |

| 74 | The translation of pāda d presents numerous issues. Kumāracandra’s commentary glosses guru in the accusative case (gurum), chaḍḍahi as the second person imperative singular (Skt. tyaja), and koha sahāva as ko ‘yam svabhāvaḥ, all in the nominative singular (Rinpoche and Dvivedī 1992, p. 78). As such, a literal translation would be “Enlightened Nature, abandon the guru.” I have chosen to interpret guru in the vocative, and koha sahāva in the accusative. Furthermore, the Tibetan translation departs significantly from the Apabhraṃśa. Pāda d: “khro ba’i rang bzhin ‘de mthong mdzod” “Behold this wrathful nature” (Rinpoche and Dvivedī 1992, p. 154). I followed the Tibetan in my own translation. |

| 75 | Kumāracandra glosses saggamaccapāālu as svarga-martya-pātālāni (Rinpoche and Dvivedī 1992, p. 38). I take païṇaccaṃte as Apabhraṃśa for the Skt. pratinṛtyante. |

| 76 | (Rinpoche and Dvivedī 1992, pp. 78–79). |

| 77 | (Newman 1988, p. 132). |

| 78 | (Newman 1988, pp. 126–30). |

| 79 | “… the nearly total deconstruction of the language may have resulted from competition. Very coarsely put, the author was seeking to create a super-Aiśa form of the language to outdo his rivals. … we must also consider the somewhat disturbing but not implausible scenario that the more important role of a scripture is simply to exist rather than to make sense” (Szántó 2012a, p. 13). |

| 80 | (Törzsök 1999, p. ii). |

| 81 | e.g., Buddhakapāla Tantra 9.9 and 13.24 (Luo 2010, pp. 5, 32). |

| 82 | (Kalff 1979, pp. 321–22). |

| 83 | E.g., the anguished reunion of King Duṣyanta and Śakuntalā in Act V of the Abhijñānaśakuntalam. Here, the King Duṣyanta speaks consistently in Sanskrit, while Śakuntalā speaks in Mahārāṣṭrī Prakrit (Kale [1969] 2017, pp. 178–87). However, Prakrits are not reserved exclusively for women; at the beginning of Act VI the lowly fisherman speaks Māgadhī Prakrit to the two guardsmen (Kale [1969] 2017, pp. 196–98). |

| 84 | khiti jala pavana hūtāsānaha tumhe bhāiṇi devī | sunaha pavańcami tatum ahu jo ṇa jānaī kovi || HT II.4.67 (Snellgrove 1964, p. 70). |

| 85 | See (Davidson 2002, pp. 269–77). |

| 86 | (Wedemeyer 2013, p. 184). |

| 87 | With the crucial distinction that proper pronunciation and phonetic reproduction is not valued or necessary, as seen in the numerous versions of these verses through Tantric Buddhist literature. |

| 88 | In the interests of time I could not consult the verses from the Khasama Tantra. However I will address them in my dissertation, which will focus on Apabhraṃśa verses throughout Tantric Buddhist literature. |

| 89 | In the Appendix A this link particularly to yoginīs is emphasized. |

| 90 | atha bhagavantaḥ sarvatathāgatā mahāparamānandarūpiṇo vajrasattvasya vavanam upaśrutya tūṣṇīṃbhāvaṃ gatā idam udānam udānayām āsu (Rinpoche and Dvivedī 1992, p. 132). |

| 91 | (Rinpoche and Dvivedī 1992, pp. 132–34). |

| 92 | atha bhagavatyo mahācarcikādyā idam udānam udānayām āsu (Rinpoche and Dvivedī 1992, p. 135) |

| 93 | Pāda c of this verse is extremely corrupt and difficult to translate. Here I am relying on the Tibetan: “bsod nams sdig pa dag dang ma ‘brel bas” “Merit and sin are divorced from [this state]” (Rinpoche and Dvivedī 1992, p. 279). |

| 94 | Given the corruption in this verse I am relying on the Tibetan: “chos rnams gno bo bde da chen po’i dngos | mchog tu dga’i ba ‘di yi ngo bo nyid” (Rinpoche and Dvivedī 1992, p. 281). |

| 95 | KYT 17.29-32 (Rinpoche and Dvivedī 1992, p. 135). |

| 96 | Given the difficulty of translating this corrupt and opaque verse, I am following the Tibetan: “de la gzugs med bsod rnams med cing sdig ba med | skye ba dang ni ‘gag pa dag ni yod ma yin” (Rinpoche and Dvivedī 1992, p. 279). |

| 97 | (Rinpoche and Dvivedī 1992, p. 151). |

| 98 | (Rinpoche and Dvivedī 1992, pp. 135–36). |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).