Abstract

This article explores the role that local elites played in the development of the Mazu cult, a local goddess cult in Putian district in late imperial China. I argue that local elites were central in the promotion and transmission of the cult. Through compiling and writing key Confucian texts featuring Mazu, they reshaped, manipulated, and represented certain aspects of her cult in accordance with their interests. As a result of the activities of local elites, Mazu became associated with the Lin lineage, an influential local lineage. In this manner, Mazu came to be seen as an expression of the lineage’s authority, as well as an imperial protector embodying local loyalty to the state and a daughter who was the paradigm filial piety. In addition to the literary production, local elites, in particular the descendants from the Lin lineage, established an ancestral hall of Lin in the port of Xianliang dedicated to Mazu, further sanctioning divinely the local elites’ authority and privilege in the community. I conclude that the locally promoted version of goddess worship operated at the intersection of state interests, Confucian ideology, the agency of local elites, and the dynamics of popular religiosity.

1. Introduction

The focus of this study is the worship of Mazu, one of the most popular goddesses in the Chinese religious landscape. Originally, Mazu was believed to protect fishermen and sailors in the area around the southeast costal village of Meizhou, in the Putian district of Fujian province. Gradually, she became popular as a sea protector throughout southeast coastal China. In light of her increasing popularity, various imperial governments, from the Song dynasty (960–1271) onward, began to promote worship of the goddess by granting her a series of honorific titles, following an established practice through which the state bestowed official recognition to local deities. Along with the state promotion of her cult, Mazu has been worshiped by Chinese people from all backgrounds throughout Chinese history, and to this day, she remains a very popular deity. The images of Mazu are not uniform; they have experienced many transformations in different times and among different groups.

This article explores certain aspects of the multifaceted images and functions of Mazu, highlighting how these transformations have been shaped by local Confucian elites, particularly in the Lin lineage, as they sought to appropriate her in accordance with their concerns, needs, and agendas.1 More specifically, I explore how the predominant roles of Mazu as a state protector, a descendant from Lin’s family lineage, and a filial daughter were constructed by Confucian literati as idealized images of the goddess that benefited and reinforced certain local interests and patriarchal values. More specifically, these images embodied traditional virtues tied to women’s subordinate social and religious status in Chinese society.

As a popular goddess in China and elsewhere, Mazu has drawn considerable attention from scholars in the field of Chinese religions and cultures. For example, Li Xianzhang’s book, Study on Mazu Worship (Maso Shinkō ken kyū), provides a comprehensive historical survey of the Mazu cult and its spread in Taiwan and Japan, primarily through collecting and organizing primary sources on Mazu worship. Although Li’s study reveals the connection between imperial patronage and the popularity of the Mazu cult in late imperial China, it does not explore the complex role of local elites.

Additionally, Judith M. Boltz’s article, “In Homage to T’ien-fei”, examines the way that Daoist elites constructed the Mazu cult through a compilation of Daoist scriptures, in particular “a Taoist liturgical work entitled Taishang laojun shuo tianfei jiuku lingyan jing.”2 This appropriation of Mazu was part and parcel of Daoists priests’ deliberate attempt to normalize popular local deities as integral members of Daoism’s pantheon. In Boltz’s discussion of Daoist scriptures dedicated to Mazu, she also pays special attention to “Mazu’s manifestation as a filial daughter of Meizhou.”3 However, her study does not dig deep into the local elites’ role in promoting this manifestation.

Regarding local elites and Mazu worship, James Watson’s article, “Standardizing the Gods: The Promotion of T’ien Hou (Empress of Heaven) along the South China Coast, 960–1960”, investigates the historical transformation of the cult and its connection with two local lineages in the New Territories of Hongkong.4 His discussion of Mazu as a patron goddess for two local lineages, the Wen and Deng, demonstrates that local elites were important agents in promoting her worship as “a symbol of lineage hegemony.”5 However, his fieldwork data is restricted to the relationship of Mazu worship with two local lineages in San tin villages, and he does not discuss the role of local elites in promoting the Mazu worship in the Putian district during the Ming and Qing eras. Two Chinese scholars, Xu Xiaowang and Luo Chunrong, do mention the entwinement of Putian elites, the Lin lineage, and Mazu worship in late imperial China.6 However, their research does not address in detail the history of how Putian elites constructed Mazu images and disseminated certain aspects of her cult that corresponded with their interests through both textual representations and patronage of temples. This is precisely the goal of this article.

To arrive at a more complete picture of the promotion of Mazu worship, I start with a brief survey of literature compiled by Putian local elites featuring Mazu’s origin and legends, especially in reference to a fully developed hagiography of Mazu circulated during the late Ming period. That is followed by an examination of three important features of Mazu’s hagiographies. First, Confucian literati created a family lineage for Mazu, which shifted her social background from a female shaman growing up in a seafarer’s family to a filial daughter with a local prestigious lineage. This construction underpins the agenda of local literati in the Putian district, who sought to promote their own local powers and status by connecting Mazu with their own lineage. There were important reasons why local literati promoted Mazu and her legends in Chinese history. The Mazu cult was very popular at the grassroots and, once endorsed by the state, came to exert enormous influence on the course of the Chinese religious and political history. Starting from the Song dynasty, later generations of local literati from the Yuan and Ming added new elements to original records of Mazu’s cult. The whole process culminated with a full-blown hagiography of Mazu, compiled by late Ming and early Qing literati.

Second, Confucian literati crafted the image of Mazu as a state protector, emphasizing her supernatural assistance to imperial governments as part of a process of state canonization. Imperial governments attempted to tame or appropriate a local deity by integrating her into the celestial bureaucracy and stressing her contributions to the government. As part of this process of state canonization, local elites underlined the goddess’ loyalty to the state, a strategy which allayed imperial worries about the unruly and potentially autonomous nature of popular religion. Third, the image of Mazu as a model daughter that was constructed by local Confucian elites functioned to emphasize virtues and values, such as filial piety, at the core of Confucianism’s views of exemplary femininity and of harmonious family life.

Following my discussion of Confucian textual appropriations of Mazu, the last section of the article addresses another extra-textual way in which local elites promoted her devotion: The construction and renovation of Mazu temples. In particular, the establishment of the ancestral hall of the Lin lineage at the port of Xianliang in the Putian district demonstrates the integration of Mazu’s cult with ancestral worship, which the Lin elites promoted to expand their influence in the local community. Through the patronage of local elites, Mazu’s supernatural persona was finally shaped into an idealized image that represented established Confucian virtues and values, and closely connected with the social and political agenda of powerful lineage.

2. Literature Production and Local Literati from Putian

Before getting into the details of the textual construction and representations of Mazu worship, this section examines the historical process of compiling key texts featuring Mazu.7 These texts suggest the ideological stances of local literati, who were either Putian natives, or local or national degree-holders serving as officials elsewhere in the empire (See Table 1). The genre of hagiographical collections concerning Mazu seems to have appeared first during the Southern Song (1127–1279) and Yuan dynasties (1271–1368). Song texts with references to Mazu’s biography include Record of Rebuilding the Ancestral Temple at Shengdun as Timely Salvation Temple (Shengdun zumiao chongjian shunji miaoji), compiled by Liao Pengfei (dates unknown) in 1150; Tales of Puyang (Puyang bishi, 1214) by Li Junfu (dates unknown); and Record of Timely Salvation Temple for Sagely Consort (Shunji shengfei miaoji, 1229) by Ding Bogui (1171–1237).8 Two main Yuan texts centered on Mazu’s legend include Record on Building the Fanxi Hall of the Ancestral Temple, Timely Salvation, at Shengdun (Shengdun shunji zumiao xinjian fanxi dian ji, 1303) by Huang Yuan, a native of the Putian region; and Cheng Duanxue’s (1278–1334) Temple Inscription of Numinous Compassion (Lingci miaoji, 1332).9 Song and Yuan texts mainly compiled by Putian literati were the starting point for textual construction of the Mazu cult.

Table 1.

A table that includes the authors, the names, and the dates of texts.

One of the Ming texts that includes various mythical stories about Mazu is the Record of the Sagely Manifestation of the Celestial Consort (Tianfei xiansheng lu).10 Attributed to monk Shi Zhaocheng (c. 1644), who took charge of the Mazu temple at Meizhou Island, the text contains seven prefaces written by seven local literati from the Putian area, who probably were the actual compilers. Tianfei xiansheng lu is commonly known as the first well-developed hagiography of Mazu, and it became one of the most influential sources on the goddess’s origin and miraculous deeds. Its main body includes three parts: The prefaces by the Confucian literati, a record of the divine birth of the Celestial Consort and a description of miracles performed by her, entitled “Original Legends of Celestial Consort’s Birth” (Tianfei jiangsheng benzhuan), and finally, official enfeoffment documents, with references to a list of imperial titles conferred by different dynasties.11

A brief survey of the social background of the seven literati is crucial to understanding the historical process of textual construction of Mazu’s image. According to Li Xianzhang’s research, Tianfei xiansheng lu was compiled by a group of local literati, starting with Lin Raoyu (1560–1628) and Lin Lanyou (1594–1659) from the late Ming era.12 The author of the first preface is Lin Raoyu, who was the metropolitan graduate (jinshi) of the seventeenth year of the Wanli reign (1589) and later assumed the official position of minister of the Department of Rites (libu shangshu). As Lin Raoyu identifies himself in the preface, he was a direct descendent from the Lin lineage of Nine Governors (jiumu), which Tianfei xiansheng lu represented as Mazu’s family lineage.13 According to his preface, Lin Raoyu initiated the compilation of Tianfei xiansheng lu, based on a primary source entitled Record of Sagely Manifestation (Xiansheng lu). This primary source was given to Zhaocheng, the monk, later, as attested by Lin Raoyou’s preface: “It is such a pity that there is a lot of information missing in Xiansheng lu. I performed ablution for writing a preface so that later generations can compile and transmit it.”14

Lin Lanyou, the author of the second preface, was from the Xianyou and Putian regions and was the metropolitan graduate of the fourth year of the Chongzhen reign (1631). His preface is followed by two prefaces written by Huang Qiyou from the Putian district, who was the metropolitan graduate of the first year of the Chongzhen reign (1634); and Lin Mei (1618–1655), a Putian native with a metropolitan graduate degree bestowed during the sixteenth year of the Chongzhen reign (1643).

The process of compilation was continued in early Qing period (1674–1680) by Qiu Renlong (dates unknown), who was born and grew up in Meizhou Island and later moved to Juncheng. As stated in his preface, he was invited by Shi Zhaocheng to compile and edit Tianfei xiansheng lu:

The monk Zhaocheng came from the Meizhou Island to visit and invite me. He said “Record of Sagely Manifestation of Celestial Consort was hidden and hence had not been circulated. I sincerely ask you to edit it so as to make it eternal.” How could you think that I would decline his request? I burned incense and cleaned table for editing and compiling it.15

It is safe to conclude that Qiu was the last compiler, thereby making a great contribution to the completion of Tianfei xiansheng lu. Qiu finalized the first version approximately in the tenth year of the Kangxi reign (1671). Following Qiu’s preface, Lin Yousheng (date unknown) wrote the sixth preface. In the postscript of his preface, Lin Yousheng identifies himself as “the descent from the Lin lineage, the nephew of Mazu, who performed ablution for reading this text.”16 We see here how a succession of literati with local connections added their authority to the emerging text through their prefaces, legitimizing the constructed tradition. Once this process was completed, monk Shi Zhaocheng was responsible for publication and transmission of this first version of the Tianfei xiansheng lu.

This hagiographical collection was reprinted several times during the Qing dynasty. Each new edition, with substantial and interesting differences, was influenced by the changing social and political environments. With surrender of Zheng Keshuang (1670–1707), who used to reign over Taiwan, some new elements were added to the second edition of the text (from 1685), which was attributed to a monk named Shi Puri (dates unknown), a senior disciple of Zhaocheng.17 This second edition of Tianfei xiansheng lu contains a seventh preface written by Lin Linchang (dates unknown). As a direct descendent of the Lin lineage from the Putian district, he served as the metropolitan graduate of the ninth year of the Kangxi reign (1670) and was sent as an imperial envoy with Wang Ji (dates unknown) to perform investiture ceremonies for the king of Ryūkyū in 1683.18 This edition also introduces historical materials from the nineteenth to the twenty second year of the Kangxi reign (1680–1683).19 These elements include: (1) An imperial title granted in the nineteenth year of Kangxi reign and a record of sending an official to offer a sacrifice in the twenty third year of the Kangxi reign (1684); (2) memorials from Wang Ji, Lin Linchang, and Shi Lang, through which these three officials reported Mazu’s miracles and petitioned for imperial titles to reward her divine help; (3) eight episodes featuring miracles performed by Mazu, including her supernatural assistance in protecting the Qing army in its conquest of Taiwan. As such, this new edition began to reflect not just the work of local officials but also the efforts of the imperial government to sanction and promote Mazu.

In the Yongzheng era (around 1727), local literati compiled and published a third edition, adding some episodes featuring the general Wan Zhengse (1637–1691) and the governor of Fujian province, Yao Qisheng (1623–1683). The third edition was overseen by Shi Tongjun (dates unknown), Zhaocheng’s junior disciple. In response to the fact that Lin Lanyou and Lin Mei were leading figures in fighting against Qing government, the two prefaces written by them were deleted from this edition. Thus, this third edition illustrates how the production and circulation of texts, with particular sanctioned interpretations, were shaped by the social, political, and cultural contexts in which they were written or edited.

There are only two surviving editions of Tianfei xiansheng lu, a block-printed edition from the Yongzheng era (1727), and a block-printed edition from the Qianlong era (1778). After Mazu was conferred the imperial title of Celestial Empress, a printed edition of Record of Sagely Manifestation of Celestial Empress (Tianhou xiansheng lu) was circulated among the populace. Its content is similar to that of previous versions of Tianfei xiansheng lu. The only difference is that it reinstates the four prefaces that were deleted from the Yongzheng edition and adds some historical records with reference to the bestowal of the title of Celestial Empress upon her.20

The literary process of compiling Mazu’s hagiography continued during the late Qing dynasty. The later Qing version of Mazu’s hagiography is further elaborated and developed, on the basis of Tianfei xiansheng lu. For example, Lin Qingbiao (dates unknown), a local Putian literati from the Lin lineage of jiumu, who was a successful candidate in the civil service examinations at the provincial level during the sixth year of the Qianlong reign (1741), compiled Record of State Conferred Heavenly Empress (Chifeng tianhou zhi) in 1778.21 This text appears to have been compiled largely from an earlier edition of Tianfei xiansheng lu. It also adds historical records of imperial titles conferred upon Mazu in both Yongzheng and Qianlong eras. In addition, the two-volume Pictorial Record of Sagely Manifestation from Holy Mother of Celestial Empress (Tianhou shengmu shengji tuzhi) was compiled around 1826. The first volume includes historical records similar to those of Chifeng tianhou zhi, while the second volume contains a set of hagiographic paintings depicting the miracles performed by Mazu in support of the Qing armies in their conquest of Taiwan, as well as other miracles originally recorded in Tianfei xiansheng lu.22 This text is written in simple language and it features illustrations. These changes were ostensibly intended to facilitate comprehension by non-educated audiences, thereby further disseminating Mazu’s cult throughout late imperial China. A late Qing text, Veritable Facts of Filial Daughter Lin (Lin xiaonü shishi), was compiled by Chen Chiyang (1788–1859), a native of the Putian area who was a successful candidate in the civil service examinations at the national level during the fourteenth year of the Jiaqing reign (1809).23

In sum, as fully-developed Mazu hagiographies, these texts were mainly compiled by local literati from the Putian district, who supported the Mazu cult. Literati from the Lin lineage of jiumu, such as Lin Raoyu, Lin Lanyou, Lin Mei, Lin Yousheng, Lin Linchang, and Lin Qingbiao, played a pivotal role in creating a textual tradition around Mazu’s worship. We shall see that this literary production intended to promote the cult and reinterpret it in ways that facilitated integration into Confucian values and virtues, and validated a genealogical connection between Mazu and the Lin lineage. The following sections focus on three essential representations of Mazu that supported this integration and validation: The goddess as a descendant from a venerable family lineage, an imperial protector, and a filial daughter of Lin.

3. (Re)constructing Mazu’s Family Lineage: Her Descent from Putian’s Lin Lineage of jiumu

A key feature of the textual reinterpretation of Mazu was the creation of a family lineage for the goddess. The formation of Mazu’s family lineage was a protracted historical process, starting from the Song and unfolding into the Qing dynasty. According to several key texts from the Song dynasty, Mazu was born in the Lin’s family of Meizhou. At the onset, there was no information on Mazu’s family lineage beyond her surname, Lin. The reference about Mazu’s lineage first appeared in the late Song, and grew in popularity throughout the Ming and Qing eras. As Mazu’s hagiography developed, it gathered more and more details, and connected her family background to the famous Lin lineage of jiumu in the Putian area. More specifically, Confucian texts compiled in the Yuan dynasty began to highlight the social background of Mazu’s father, Lin Yuan. The process of constructing a prestigious family background for Mazu reached its full development in three texts I introduced in the previous section: Tianfei xiansheng lu (1626), Chifeng tianhou zhi (1788), and Lin xiaonü shishi (around the beginning of the nineteenth century). In this section, I will explore the historical process of developing Mazu’s family lineage in Mazu literature, as well as how prevalent Confucian ideology and local agency framed these lineage constructs.

The earliest account of Mazu’s family origin appears in Shengdun zumiao chongjian shunji miaoji, compiled by Liao Pengfei in 1150, during the Song dynasty.24 Liao’s record starts with a brief summary of Mazu’s origin:

The dynasty from which [the goddess] originated was unknown. The only thing known was that the goddess people worship was extremely numinous. It was said that she was the goddess who was capable of communicating with Heaven. Her surname was Lin and she lived at Meizhou Island. At first, she lived as a female shaman and had the ability to forecast fortune and misfortune. After she died, people built a temple for her in this island.25

The only information referring to family background of Mazu is that the goddess originally comes from the Lin family of Meizhou island. By the end of the Song period, Mazu’s family lineage was an established fixture of the Mazu legend. This is evident in Li Junfu’s Puyang bishi, which is a seven-volume miscellanea featuring legends of local deities and famous people. The seventh volume, dedicated to Mazu, firmly states that “she lived in Meizhou Island, and her surname is Lin.”26 A substantial part of this book includes legends featuring well-known Confucian literati from the Lin clan of Putian. For example, volumes one and four have accounts of famous officials of Lin in the Tang dynasty, such as Lin Pi (733–802) and his two sons, Lin Zao (?–805) and Lin Yun (755–?). Although Li’s book makes clear reference to Mazu’s social status as a daughter from the Lin family in Meizhou Island, there is no detailed information which connects her directly to these famous Tang literati. However, all these figures and their stories later functioned as primary sources for the Ming literati’s construction of Mazu’s family lineage. Ming Confucian literati consciously built the connection between Mazu and the Lin lineage in the Putian district, tracing Mazu’s lineage back to Lin Pi and his son, Lin Yun, Mazu’s purported ancestors.

Huang Yansun’s (1218–?) Gazetteer of Xianxi District (Xianxi xianzhi, 1257) is the first text to identify Mazu’s parents. It states, “The father of the goddess was Lin Yuan; her mother was Lady Wang.”27 This can be considered the starting point for the detailed construction of Mazu’s family lineage. Based on early Song texts, Confucian literati during the Yuan dynasty continued to create and rework Mazu’s lineage by glorifying the social status of Mazu’s father, Lin Yuan. For example, Lingci miaoji (1332), compiled by Cheng Duanxue, creates an official status for him. It states, “According to the goddess’s surname, Lin, she is the little daughter of a chief military inspector (duxun guan) in the Putian district of Xinghua prefecture.”28 The Yuan version of Mazu’s lineage is skeletal in comparison to those developed in the Ming and Qing, but the perception that Mazu is the daughter of a local official became a new feature of Mazu’s family lineage. These themes continued in later versions, but in the Ming, new details built up Mazu’s lineage significantly.

The literary strategy of romanticizing Mazu’s lineage by adding key figures with high official statuses is especially evident in the late Ming and early Qing texts, among Confucian literati who descended from Lin’s lineage of the Putian district. According to David Faure, “the lineage had compiled a written genealogy tracing the lineage to some high-ranking official, come to be accepted as the standard in lineage building.”29 Explicit mention of Mazu’s lineage connected with Lin Pi appears in several Mazu’s hagiographies, including Tianfei xiansheng lu, Chifeng tianhou zhi, and Lin xiaonü shishi.

Tianfei xiansheng lu presents the first detailed account of Mazu’s lineage as originating from Lin Pi, stating that Mazu was a ninth-generation descendent of Lin Pi. This text starts by introducing Mazu’s lineage and then traces the Lin lineage back to Lin Pi, with a special reference to Lin Pi’s and his descendants’ official statuses and titles. The text continues by presenting how Lin Pi’s descendants returned to their native town in the Putian district of Fujian province:

Celestial Consort of Meizhou was the daughter of Lin’s family of Putian. The first ancestor was Lord Lin Pi from the Tang dynasty, who had nine sons, all of whom were virtuous person. During the Xianzong era (778–820), the nine sons were all entitled as Governors of Prefecture, alternatively named the Nine Governors. The great grandfather of Celestial Consort was Lin Baoji, who was the sixth-generation descent from Lin Yun. Lin Baoji was appointed as the army commander for horse pasturages in the Xiande reign (954–959) of Zhou (921–959)……He resigned from office and returned to Meizhou Island to live a reclusive life. Her grandfather Lin Fu was appointed as the area commander-in-chief of Fujian with a heritable noble title. Lin Fu’s son, Lin Yuan, was a chief military inspector in the Song dynasty. Lin Yuan is the father of Celestial Consort. Lin Yuan married Lady Wang, who gave birth of one son named Lin Hongyi, and six daughters. Celestial Consort was the sixth daughter, the youngest one.30

Several new elements appear in this version of Mazu’s lineage: A fully developed genealogy with ancestors’ names and official titles, starting from Lin Pi to Lin Yun, Lin Baoji, Lin Fu, and finally Lin Yuan. All Mazu’s direct ancestors mentioned in the genealogy were connected to important official positions either in the central government or local governments. This is commonly accepted as the true and final version of Mazu’s family linage as shown in Mazu’s hagiographies of Qing dynasty. For example, Chifeng tianhou zhi (1778) compiled by Lin Qingbiao offers a more detailed version of Mazu’s lineage, the Lin of qiumu, which is identical to that of Tianfei xiansheng lu:

The lord Lin Pi assumed the position of the Inspector and Supervisor of the Household of the Heir Apparent (jianjiao taizi zhanshi) in the Tang court. He had nine sons, all of whom were entitled as Governors of Prefecture. It was well known as the family of Nine Governors (jiumu). The sixth son, Lin Yun, assumed the position of the Governor of Shao Prefecture who was granted with an honorable title “Loyal Martyr” after death. Lin Yun had a son, named Yuan (who had the same name as that of Mazu’s father). Yuan had four sons among whom the third son, Lin Yu, assumed the position of governor of prefecture (zhoumu) in the reign of Min King, Wang Shenzhi (862–925). Lin Yu, the great great grandfather of Celestial Empress (Mazu), had one son, Lin Baoji. He resigned from office and returned to Xianliang port in the Meizhou area to live a reclusive life. Lin Baoji had a son, named Lin Fu, who was appointed as the area commander-in-chief of Fujian. Fu gave birth of Lin Weique, who was also named Yuan. The goddess’s father, Lin Yuan, was a chief military inspector who had a son, Lin Hongyi, and six daughters. The Celestial Empress was the sixth daughter.

Similar to Mazu’s genealogy recorded in the two texts above, Lin xiaonü shishi gives a rough version of Mazu’s lineage.31

These texts trace Mazu’s ancestry to the most prestigious family of the Lin lineage, the Lin of jiumu in the Tang dynasty. The father of this family, Lin Pi, and his two sons, Lin Yun and Lin Zao, were recognized as three key patriarchal figures. As stated in other texts compiled in late Ming and Qing, Lin Pi assumed high official positions in the Tang court, such as the inspector and supervisor of the household of the heir apparent (jianjiao taizi zhanshi), and the adjunct mounted escort of Su Prefecture (suzhou biejia). When he died, he was conferred the honorific title of Governor of Mu Prefecture (muzhou cishi). Lin Pi had nine sons who all took the official position of prefectural governor (cishi).32 Based on this prestigious history, Lin Pi’s family was regarded as “The Family of Nine Governors” (jiumu zhijia).33 According to extant primary sources and textual analysis of secondary sources, “the Family of Nine Governors” was one of the most prestigious elite families in the Putian district.34 In other words, the local literati’s imagined conflation of Mazu’s family lineage with the most prestigious lineage of Lin served to promote a particular form of goddess worship that sacralized local authority.

Some scholars question the authenticity of this imputed lineage based on the fact that there was no record of Mazu’s great grandfather, Lin Baoji, her grandfather Lin Fu, and her father Lin Yuan in official history.35 This is certainly the case of Lin Fu, who was said to have been appointed as the area commander-in-chief of Fujian (fujian zongguan). This official title did not exist in the five dynasties where Lin Fu lived in. At that time, the highest position in Fujian province was the surveillance commissioner (guancha shi). There is no other record that Lin Fu occupied this official title. Zhou Ying (1430–1518), a contemporaneous local scholar of the Putian district, has also he questioned elements of Mazu’s putative lineage, His preface to Gazetteer of Xinghua Prefecture (Xinghua fuzhi) states,

when I was young, I read the Gazetteer of Putian District compiled during the Song dynasty. The original version of the Shaoxi era (1190–1194) describes the Consort as a female shaman of a village. Later, I read the version of the Yanyou era (1314–1320) in which she was called as the goddess. The current versions of gazetteer all represent Mazu as the daughter of chief military inspector, Lin Yuan. The avowed lineage gradually lost its authenticity.36

According to Zhou, Mazu was originally a female shaman with unknown family background. With the popularity of the Mazu worship in the Putian area, local literati from the Lin clan represented Mazu as a descendant of the Lin lineage. Based on all these facts, it is fair to conclude that the official titles occupied by her ancestors were added by local literati as one way to glorify Mazu’s family lineage.

It is notable that all literary texts above stress Mazu’s prestigious social origin by situating Mazu in the family of a virtuous official. This process also reveals the Confucian agenda of local elites from the Lin lineage. According to Robert Hymes, the Confucian elites shifted their attention from national affairs, such as seeking office-holding or the pursuit of high office, toward the local during the late imperial China.37 This turn was mainly caused by the loss of north China to the Jurchen. This loss “signaled the failure of state activism for many contemporaries and conclusively shattered the perception of common interests between the state and Confucian literati that the factional battles of the late northern Song had already strained to the breaking point.”38 As a consequence of this breakdown, Confucian elites increasingly focused on consolidating local power, primarily by boosting their lineages, which were the source of their standing and legitimacy. Hymes points out that consolidating local power also required controlling “popular religious cults and practices.”39 As Putian gentlemen grew more interested in the various gods and saints of their own region, they began to pay more attention to the Mazu cult. They thus proceeded to compile Mazu’s hagiography, emphasizing her local identity as a daughter from a prestigious family linage. This focus also influenced how local literati represented Mazu. By constructing a family lineage for Mazu, Confucian literati transformed her from a local shaman, acting relatively autonomously from the state to protect seafarers to a dutiful daughter of a local official, thereby bolstering state-sanctioned social and political hierarchies. The emphasis on Mazu’s origin as a daughter of Lin’s family indicates the local elites’ own real and wished-for power: To underscore the divinely given and permanent quality of their local status and privilege. This creative appropriation of Mazu was gendered in the sense that it disciplined the heterogenous local lore about the goddess, producing an orthodox view of Mazu which operated within a clear and normative patriarchal order.

To sum up, the construction of Mazu’s image as a descendant of the Lin Lineage of jiumu points to a dual process in late imperial China: The localization of state power (meaning a strong focus on how to control local life as way to compensate for the gaps produced by factional fighting and external threats) and the translocal circulation of particular local symbols, like Mazu, reworked into a canonical form by the state officials. Moreover, this dual process reveals the symbiotic relation between local elites and the state. The latter needed the loyalty of local elites in order to make itself present locally. Thus, the state was vested in buttressing and legitimizing the power of local elites. In turn, local elites needed the imperial state’s sanction of their local offices and status. Mazu’s reconstructed image as part of the Lin lineage was a key factor in establishing and maintaining this symbiotic relation between local elites and the state. This is particularly attested to by another feature of Mazu’s textual representation: An imperial protector. The emerging representations of Mazu did not just reflect local interests, but also the agenda of the state. By creating a received tradition and worship around Mazu, the local elites expressed their loyalty to the central government.

4. Mazu as Imperial Protector: The Expression of the Local Elites’ Loyalty to the State

This section discusses a key feature of the textual conceptualization of Mazu’s image, namely, Mazu’s role as a symbol of imperial protection. More specifically, I will discuss various texts presenting her as defending the state from invasion by foreign ethnic groups, guarding grain transportation, suppressing pirates, warding off natural disasters, and protecting imperial envoys from sea storms. On the whole, this image of Mazu is in line with the process of state patronage, highlighting the goddess’s contributions to the state, starting from late Song dynasty.40 The imperial states canonized or promoted Mazu’s cult through three intertwined strategies: (i) Granting official titles, (ii) incorporating local gods and goddesses into the register of sacrifices, and (iii) constructing official temples. As a result of state canonization, Mazu “became associated with domestic defense and warfare, the protection of government officials, and the involvement in political endeavors. As such, the imperial version of goddess worship served to justify and reinforce imperial authority.”41

The textual representation of Mazu as a guardian goddess of the imperial government began with the Song literati. It is worth noting that all texts I have surveyed present Mazu as a universalistic deity who saves everyone in need, from imperial officials to poor seafarers. Both Liao Pengfei’s and Li Junfu’s texts mention that local people venerated the goddess because of her supernatural power to guide seafarers safely home. In addition to protecting seafarers, Ding Bogui’s Shunji shengfei miaoji (1228) lists all the divine manifestations associated with Mazu’s role in protecting the Song state. The range of goddess’s divine protection covers every aspect of the state’s affairs, including guiding an imperial emissary, Lu Yundi, and his fleet safely through a storm, suppressing pirates’ intrusions, saving people from epidemic diseases, and protecting people from droughts and floods. This text also gives detailed description of Mazu’s divine assistance in fighting against Jin “barbarians”:

In the second year of the Kaixi reign (1206), Jin barbarians invaded the area of south part of Hui river. The prefect ordered soldiers to carry on the burning incenses for the goddess when marching to battle. The first battle occurred at Huayan town; the second battle happened at Mt. Zijin; the third battle led to the rescue of Hefei from a siege laid by the Jin. The goddess manifested herself in the clouds holding a flag. Consequently, soldiers showed their great bravery and returned home after their triumph in battle.42

According to this text, Mazu’s manifestation was crucial to Song’s triumph over the Jin. The same text also describes Mazu’s merit in the suppression of pirates. It states that “during the Lizong reign (1224–1264), pirates intruded into our country and were going to rob villagers. The goddess got their ships stranded. Subsequently, the pirates all got captured and arrested.”43 In this context, the function of the goddess became closely connected with Song government’s interests. This textual representation is in line with the Song state’s recognition of the Mazu cult by granting titles to reward her special contribution to the state. For example, the Southern Song government granted thirteen titles to Mazu, ostensibly to reward the goddess for her loyalty and miraculous assistance in imperial affairs.44 Mazu’s special contribution in repelling a sea pirates’ invasion also led to her promotion as The Lady of Numinous Wisdom and Glorious Response (Linghui zhaoying furen). Later, based on a belief that she played a significant role in ending a drought and epidemic, Mazu was promoted from Lady to The Consort of Numinous Wisdom (Linghui fei) by the imperial court.45

The popularity of Mazu’s image as state protector continued in the textual representations of Confucian literati of subsequent dynasties. Yuan texts featuring Mazu credit her with meritorious service to the state, in particular guarding water transportation. This is particularly evident in Cheng Duanxue’s Lingci miaoji (1332), in which Cheng records two legends as follow:

In the second year of the Tianli reign (1329), the vice transport commissioner and brigade commander Bashi (a major supervisory unit of the Mongol Army) oversaw grain transport ships sailing to Sansha. At that time, a hurricane lasted for seven days. They called the goddess’s name in a long distance. At night, they witnessed the divine light of the goddess raising up from all sides. After that, the wind stopped blowing and the waves calmed down. Grain ships all crossed the storm safely.46In summer of the third year of the Zhishun reign (1332), grain ships of the government were commandeered to sail to the sea around Laizhou. At the mid-night, the wind blew heavily. After praying to goddess, they saw goddess’s image and then the wind changed from upwind to downwind. In this year, no ships were in danger.47

Mazu’s reputation rests on her ability to guard grain ships for the Yuan government. The reason why Yuan texts stress Mazu’s function as a guardian of water transportation is due to the fact that the Yuan government greatly depended on maritime and water transportation of grain to the capital, Dadu. Moving grain efficiently, especially to remote areas, guaranteed the stability and legitimacy of the state. As such, the Yuan literati’s emphasis of Mazu’s role as a guardian of water transportation dovetailed with the interests of the imperial government. This image of Mazu is in accord with an imperial edict issued by Emperor Shizu (1215–1294) of Yuan, stating that “she was able to protect the grain transport every year and benefit the state; she guarded the country with loyalty; with her compassion and wisdom, she kept the people safe ….”48 Similar to Song’s legends, Yuan textual representations also stressed the key Confucian virtue attributed to Mazu: Political loyalty to the imperial state.

The late Ming text, Tianfei xiansheng lu, which, as we recounted above, contains a full-blown version of Mazu’s hagiography, incorporates and reworks Mazu’s legends recorded in Song and Yuan texts, with a special emphasis on her role as imperial protector. Tianfei xiansheng lu includes thirty-six episodes that illustrate Mazu’s merits, performed after her deification. In addition to her divine manifestations recorded in Song and Yuan texts, it also extols Mazu’s supernatural assistance in protecting the Ming state, specifically in safeguarding imperial envoys and treasure fleets led by the imperial eunuch envoy Zheng He. Mazu’s function as imperial protector in Tianfei xiansheng lu can be summarized in the following key themes.

The first theme is that Mazu protects imperial envoys which either undertake expeditions or visits to other subordinate countries. This is evident in the episode “Saving the Eunuch Zheng He at Guang Prefecture” (Guangzhou jiu taijian Zheng He):

In the first year of the Yongle reign (1403), the imperial eunuch envoy Zheng He and others departed to Thailand. When they arrived at the sea of the Daxing area in Guangzhou, the fleet encountered a typhoon. The ship almost got sunk. Sailors on the ship asked [Zheng He] to pray to the Celestial Consort. Zheng He invoked the goddess, saying, “Zheng He was sent on a mission to visit foreign countries. We are encountering danger caused by winds and waves. My body is certainly not worth of cherishing, but what I am afraid is that I cannot report and repay the Emperor. Moreover, hundreds of people’s lives are at stake at the moment of breathing. May the Celestial Consort save us!”49

This episode ends with the goddess’s divine manifestation upon the masthead of Zheng He’s fleet, guiding them through the storm to safety.

Similar narratives, in which Mazu manifests herself to save imperial envoys and fleets from sea storms, appear in different contexts. That is especially the case in “Protecting Palace Commissioner Zhang Yuan at Eastern Sea” (Donghai hu neishi zhangyuan), “Saving Eunuch Chai Shan at Ryukyu Island” (Liuqiu jiu taijian chaishan), and “Sheltering Eunuch Yang Hong Who Visited Eight Tributary Subordinates” (Bi taijian yanghong shi zhufan baguo).50 All these episodes contain several common elements: (i) The figures saved by the goddess are imperial envoys representing the Ming government, (ii) they are all threatened by storms or capricious waves at sea, (iii) in response to prayers, Mazu tames the sea and brings order to the coast. These literary narratives were in line with the official documents of the Ming dynasty, which also stress Mazu’s important role in protecting official envoys from sea storms. For example, two inscriptions at Tianfei temples, in Liujia gang (1431) and Changle (1431), make reference to Mazu’s divine protection of imperial envoys from dangerous storms at sea.51 In all these stories, Mazu, functioned to protect imperial envoys, thereby enabling the Ming dynasty to project its power and reputation successfully.

The second major theme pertaining to Mazu’s role as a state protector is her divine assistance in suppressing pirates and disloyal officials. Below is a typical story, “Pushing over Waves to Help Ships Cross a Storm”, (Yonglang jizhou), which describes Mazu’s contribution in assisting Ming military ships to fight pirates and keep the state secure:

In the seventh year of the Hongwu reign (1374), the commander of Quan Prefecture, Zhou Zuo, ordered warships to patrol and arrest [pirates]. Suddenly, they encountered a strong hurricane springing up. The anchor was broken up and the ship ran aground. Sailors on the ship cried from all sides, knocked their heads, and cried for the goddess’s help. Shortly later, there was a divine light appearing in dark night which floated in mid-air, illuminating everything. The divine light also appeared upon the masthead of the ship.52

The divine light was believed to be a sign of Mazu’s divine protection. Mazu was able to push over huge waves to allow the military ships to make it to the harbor safely. This story ends with Commander Zhou’s efforts to sponsor the construction of a building in Mazu’s temple in Meizhou Island.53 Similar stories surround Capital Commander Zhang Yu’s (1430–?) battle with Japanese pirates. Mazu’s divine manifestation was allegedly crucial in encouraging Ming soldiers to fight off the pirates. In the end, Ming military troops successfully defeated all Japanese pirates.54 In addition, the episode of “Executing Disloyal Officials through Manifesting Herself in One’s Dream” (Tuomeng chujian) describes Mazu’s assistance in executing a disloyal official of the Ming government. Mazu manifested herself in a dream of Lin Run (1531–1570), a censor (yushi) from the Lin lineage in the Putian district, admonishing him for excusing the most disloyal official Yan Song (1480–1567).55

Local elites’ efforts to portray Mazu as a state protector continued during the Qing dynasty. An excellent example of Qing literati’s construction is found in second and third revised versions of Tianfei xiansheng lu, which was compiled in the early Qing dynasty, around 1682.56 It adds nine more episodes centering on Mazu’s merit of protecting the Qing state. She also now becomes a “martial” deity closely aligned with the Qing government’s military interests under the Kangxi’s reign, including Qing’s conquest of Taiwan and the sending of imperial envoys to Ryukyu Island.

In terms of the Qing military reclaiming Taiwan, four episodes involve General Shi Lang’s military campaign in Taiwan, while four more refer to the Grand Governor (da zongdu) Yao Qisheng (1623–1683)’s conquest of the island. Regarding Shi Lang, the episode “Supplying the Army with a Bubbling Spring” (Yongquan jishi) describes how Mazu saved the whole army by providing fresh water.57

According to Qing’s official documents, such as the Veritable Records of the Qing Shengzu (Qing shengzu shilu), the Qing government during the nineteenth to the twenty-second year of the Kangxi reign (1680–1683) sought to suppress the hostile force controlled by Zheng Keshuang (1670–1707), who took Xiamen, Jinmen, Penghu Island, and Taiwan.58 Yao Qisheng and Shi Lang received the imperial order to reclaim Taiwan from Zheng Keshuang. This is also evident in Shi Lang’s Record of Pacifying the Sea (Jinghai jishi), in which he attributed his military conquest of Taiwan to the aid of Mazu.59

Based on the historical record, it is safe to conclude that Qing local scholars reworked the Mazu’s legend to reflect the Qing’s political needs. Qing texts promote Mazu as a divine protector of Qing’s army. With her divine assistance, the Qing government was successful in pacifying the southeast coast of China and maintaining territorial integrity of Qing dynasty.

The analysis above suggests that local literati sought to highlight Mazu’s contributions to imperial governments. By doing this, these local elites expressed their loyalty to both the local and the central governments. The emphasis on Mazu’s services to the state indicates the interaction among state interests, Confucian ideology, local agency, and the Mazu cult. Song texts present Mazu as state protector in fighting with Jin barbarians and suppressing pirates. Yuan texts stress Mazu’s image as divine guardian of water transportation, which was crucial to Yuan’s development. Ming texts emphasize Mazu’s role in protecting imperial envoys and suppressing pirates. Qing versions of the Mazu’s legend praise her contribution to the Qing government with a special focus on her divine assistance in conquering Taiwan. In this historical process of constructing Mazu as imperial protector, local Confucian literati highlighted aspects of Mazu’s images that corresponded to the changing interests of different dynasties. In other words, the changing social and political context influenced the way through which local literati reframed Mazu’s image and through which the state canonized the goddess.

Mazu’s key role as an imperial protector, in particular her universal sovereignty over state affairs, serves as a good entry point to discuss feminist and gendered symbolism. This version of Mazu’s image illustrates male literati’s perspectives and their local agency. They redefined the femininity of the goddess, particularly her avowed original identity as a female shaman, to make her an expression of their loyalty to the government and a vehicle to support endeavors, such as war, the enforcement of law and order, transportation of goods across the empire, that were the exclusive province of men. In this sense, this image of Mazu reinforces patriarchal structures by giving divine sanction to male-dominated public affairs that were vital to the survival of the state and, as I have argued elsewhere and we will see below, by embodying virtues of piety tied to women’s subordination in the domestic sphere. The powerful goddess came to embody an idealized version of femininity, selflessly serving the emperor, the state, and his officials, just like Mazu served her father, an ideal to which all women should aspire, but which they cannot achieve.

Official enfeoffment documents containing a list of imperial titles conferred upon Mazu by different dynasties compiled by local literati, such as Tianfei xiansheng lu and Chifeng tianhou zhi, also suggests a strong connection between the Confucian image of Mazu as imperial protector and Mazu’s state canonization. According to Valerie Hansen, “one way for an elite group to enhance its status was to seek a title for the god it supported.”60 In other words, the local elites worked the granting title system to obtain legitimacy from the central government and promote their social and political status. This legitimation was possible because the format of inscriptions and petitions indicate the social status of different people who supported the deities: The author of the text, the person who organized the funding, the main donors who provided land or financial support, or the individuals who took charge of the construction or reconstruction of temples. Following Hansen’s argument, state canonization opens a space for local elite groups to display their cultural and religious power in local society. By seeking canonization for a locally popular deity, local elites attained and maintained their positions in local society. In that sense, the popularity of a deity at the local and translocal levels feed into each other. Powerful lineages sometimes claimed an ancestral tie to popular deities to gain official honors for the whole lineage, as in the case of Mazu’s association with the Lin lineage of Meizhou. I will discuss the material dimensions of this association in the section of “Local Elites’ Patronage of Mazu Temples.”61 However, I would like to focus first on the third cluster of textual representations—in addition to making her a descendent of prestigious lineage and an imperial protector—that local elites constructed around Mazu.

5. Filial Daughter of Meizhou: The Embodiment of Confucian Virtues

As we saw in section three on the construction of Mazu’s family lineage, Song and Yuan texts concerning legends attributed to her do not mention filial piety as a key element of her birth and life. It is only with the establishment of a family lineage that filial piety became woven into Mazu’s legends.

The earliest accounts of Mazu’s putative origin and her life, compiled in the late Song era, emphasize her supernatural skills in predicting the future and saving people. Liao Pengfei, Li Junfu, and Ding Bogui all pointed out that her supernatural ability to communicate with the divine realm led to the establishment of shrines and temples for the goddess. As discussed in previous sections, the only information about her family in Song texts is that Mazu was born in the Lin family of Meizhou. Later texts, such as Huang Yansun’s Gazetteer of Xianxi District (1257) and Cheng Duanxue’s Lingci miaoji (1332), identify Mazu’s parents as Lin Yuan and Lady Wang. This identification provides a starting point for the textual representation of Mazu as a filial daughter, which became well-established by the late Ming text, Tianfei xiansheng lu (1644).62

The section entitled “Original Legends of Celestial Consort’s Birth” (Tianfei jiangsheng benzhuan) in Tianfei xiansheng lu contains a couple of episodes featuring Mazu’s birth and her rescue efforts at sea.63 According to one episode, “Rescuing Father and Brother on the Loom” (Jishang jiuqin), Mazu rescued her father from typhoon at sea in a dream. This narrative starts with her father and brother going on a sailing trip. Unfortunately, Mazu’s father and brother encountered a typhoon and almost drowned. As this was happening, Mazu dreamt of them drowning:

The Celestial Consort was weaving; suddenly she closed her eyes on the loom and underwent a spiritual journey. Her facial appearance suddenly changed. She was carrying the loom shuttle with her hands; treading on the loom’s wheel axle with her feet. It seemed like she was clasping something under her arms while fearing to lose it. Her mother felt strange and hastened to wake her up. The Celestial Consort waked up and dropped the shuttle. She wept and said, “Father was quite well, but brother got drowned.” In an instant, reports arrived, it was indeed the case. At that time, her father was disturbed by the violent waves not knowing what to do. He almost drowned several times. Indistinctly, there was something pulling up his boat close to the Consort’s brother’s boat. Shortly afterwards, her brother’s boat was entirely destroyed and overturned. For when the Consort closing her eyes, what she treaded by feet was her father’s boat, while what she carried by hands was her brother’s boat.64

This episode highlights two key aspects of Confucian virtues as represented by Mazu, namely her filial piety (xiao) and love for her brother (di). It is obvious that the literati consciously wove these virtues and values into the goddess’s legend. Mazu’s success of rescuing her father reveals that she fulfilled her responsibility as a filial daughter. In this narrative, Mazu was able to rescue her father due to her supernatural power. Here Mazu’s actions do not have to do with the affairs of state, but with domestic matters. Her ability to perform miracles, to save her father, the pillar of the Confucian family, becomes the reason for the people’s veneration and the state’s recognition of her divine power.

Other sources written by local literati, however, directly attribute Mazu’s sanctity to her filial acts rather than her supernatural power. To stress Mazu as the embodiment of filial piety, some literati reworked the narrative of “Rescuing Father and Brother on the Loom” by historicizing this mythical story. The most important example is Lin xiaonü shishi, compiled by Chen Chiyang. In this revised version, the reference to her spiritual journey is omitted, so as to make her filial act more realistic. It claims that Mazu rescued her father and brother in reality. In addition, to highlight Mazu’s filial act, Chen Chiyang renamed Mazu as “Filial Daughter Lin.” Confucian promotion of filial piety in Mazu’s legend is also situated in the context of her prestigious family lineage. As stated in the text, “Filial Daughter [Mazu] descended from Putian. She was the ninth generation descendent of Lin Yun, who was the governor of Shao Prefecture in the Tang dynasty……Her father, Lin Yuan, was a chief military inspector in the Song. Filial Daughter was the sixth child, the youngest one.”65 This text continues to “Confucianize” Mazu by stressing her education in Confucian teachings: “When she was eight, she studied with a private Confucian tutor. She fully familiarized and comprehended the meaning of phrases.”66 Although we do not know detailed information about Mazu’s Confucian training, it is safe to assume that, in this version of the story, Mazu received some classical education, as was common for the daughters of families with upper social standing.

Mazu’s familiarity with Confucian teachings and values lays the foundation for her filial acts. The rest of the passage in this text describes the fact that Mazu rescued her father from a typhoon at sea. Here, a salient change is made in comparison to the version found in Tianfei xiansheng lu:

[Mazu] was crossing the sea together with her father and brother when she was sixteen. At that time, they experienced a very strong storm which caused them to be shipwrecked. “Filial Daughter” immediately carried her father on her back and swam to the shore. Finally, her father was quite well, but her brother got drowned.67

Although she was unable to save her brother, she was successful in finding her brother’s corpse and getting it buried properly. The rewritten story stresses two key Confucian virtues represented by Mazu, “filial piety and sibling love.”68 The text ends with other good deeds done by Mazu, who also saved other drowning victims at sea. An important development evident in this record is that all these good deeds are attributed to Mazu’s virtuous character, along with her swimming skill, rather than the supernatural ability mentioned in other texts. This is in line with the Confucian notion of the cultivation of the inherent qualities of humanness, rather than reliance on supernatural forces that were central in popular Chinese religions. Confucian literati grounded Mazu’s religious authority in her perfect fulfilment of Confucian virtues that are part of being an exemplary female, rather than on an intense connection with the divine, which is a central aspect of popular beliefs and practices.

In addition to emphasizing Mazu’s image as a filial daughter, versions of her biography like those found in Lin xiaonü shishi also tend to ignore the fact that she died early and did not marry, thus deviating from the Confucian norm that the overriding duty of virtuous women is to form families.69 Mazu’s death is glossed over in Confucian versions, and little is said about it except that she was freed to become a deity and ascend to Heaven as an undefiled. That is evident in one episode, “Ascending to Heaven in Meizhou” (Meizhou feisheng), of Tianfei xiansheng lu.70 Mazu’s ascending to heaven is also a prevalent representation of Mazu’s death in other versions of Confucian texts, such as Chifeng tianhou zhi. Early death and “marriage resistance” could be construed as bold and provocative challenges to Confucianism, which was anchored upon family life and the principle of filial piety. The Confucian ideal of filial piety was grounded firmly on the continuance of the family lineage. Confucianism put the bond to one’s parents at the center of life, with marriage and reproduction as the supreme filial duties. Women had to be absolutely chaste, except within marriage. Within the family, they had to assume primary responsibility for rearing children and caring for elders. In light of these values, Confucian literati had every reason to downplay in their hagiographies the fact that Mazu did not marry. To reconcile Mazu’s early death as an unwed maiden with Confucian core family values, Confucian scholars reworked Mazu’s hagiography, representing her as the paragon of the filial daughter.

The process of integrating filial piety into Mazu’s legend indicates a significant characteristic of Confucian writings. As Denis Twitchett has pointed out, Chinese literati wrote biographies to illustrate the Confucian virtues of their subjects by linking them with Confucian virtues from the ancient past.71 Early authors of books about women tended to stress unusually extreme interpretations of Confucian values. According to Confucian classics, filial piety demands total self-sacrifice. Women who had the courage to self-sacrifice were described as virtuous, even saintly. In the eyes of famous Confucian scholar, Quan Zuwang (1705–1755), when women were recognized as deities, it was due to their loyalty, purity, chastity, and filial piety. “As in the case of exemplary women, Lady Xiang was worshiped due to the fact that she followed Shun unto death; Nü Xu was sacrificed due to the fact that her young brother was Qu Yuan; Cao E was venerated due to her filial piety. Examples like that are countless.”72

The rhetoric about female filial piety became a central feature of Confucian interpretation of womanhood. In two Han dynasty texts, Liu Xiang’s (79–8 BCE) Biographies of Women (Lienü zhuan) and Ban Zhao’s (45–117) Admonitions for Women (Nüjie), filial piety is presented as the supreme virtue required of everyone in society. These Confucian texts promoted exemplary women as emblems of filial piety and embodiments of Confucian morality. Reflecting this Confucian ideal, the notion of a “filial daughter” is a prominent theme in a number of Mazu texts written by Confucian scholars from the Qing era, as evidenced in Zhang Xueli’s (dates unknow) account, Record of An Envoy to Ryukyu Island (Shi liuqiu ji, 1663).73 In Zhang’s account, Mazu is said to have sacrificed her life to rescue her father. Instead, Mazu drowned and thereby ascended into heaven by virtue of her meritorious effort. In a later version of “Mazu Rescuing Her Father and Brother”, her filial act is modified as an extremely selfless act of a daughter willing to risk her life for her father. Late Qing Confucian literati continued to historicize Mazu as a filial daughter, while neglecting her origin as female shaman and her supernatural power.74

As one of the essential Confucian virtues, filial piety (xiào) can be understood in different ways. At the familial level, it is the basis for personal morality. Moreover, filial devotion to one’s parents, extended to one’s elders and ancestors, is foundation of all ethics since it is the hallmark of one’s humanness. For Confucius, filial piety is not just a private virtue limited to the familial realm. This virtue reaches far beyond the family, into the realm of state affairs and institutions. According to the Classics of Filial Piety (Xiaojing), filial piety begins by serving one’s parents in the familial realm and culminates in one’s service to the state in the political realm, primarily undertaken in order to honor one’s parents and bring reverence to one’s lineage.75 It states, “filial piety is the root of virtue and the source of civilization…filial piety begins with the serving our parents, continues with serving the ruler, and is completed by establishing one’s character.”76 This definition of filial piety is informed by a patriarchal view of the social order and the cosmos, since at the top of the family and the state stood male authority, whether the father or the emperor, who had received the Mandate of Heaven to rule justly. Therefore, filial piety serves to strengthen patriarchy, complementing the image of Mazu as a protector of the state, which was run by men.

In sum, Mazu’s hagiographies compiled by local elites illustrate the ways that local Confucian groups rewrote and reconstructed the image of a popular goddess in order to promote certain Confucian values in line with their agendas and interests, while simultaneously strengthening the power of the state. The depiction of Mazu as the model daughter, selflessly working to protect the status quo, served to domesticate, as it were, the religious authority of the goddess and enlist her to buttress the hierarchical and patriarchal values and beliefs of a Confucian-based social order. This promotion was not just limited to textual representations, but also involved economic and material dimensions, such as the local elites’ sponsorship of the construction and repair of Mazu temples.

6. The Ancestral Hall of the Celestial Empress at Xianliang Port: A Symbol of Hegemony of the Lin Lineage of Jiumu

In addition to the textual representations of Mazu, local elites, in particular descents of Lin lineage of jiumu, also contributed to the establishment of Mazu temples in Fujian province and other places in Southeast China. These elites played an important cultural role by promoting the development of local religion.77 Starting from the thirteenth century, local elites along with merchants from Putian who traveled outside Fujian province, began to support the establishment of Mazu temples in other places, such as the Jiangzhe area (present-day Jiangsu and Zhejiang provinces). Temple inscriptions from that area give evidence that Putian elites sponsored the building of branch temples dedicated to Mazu. For example, a temple inscription written by Ding Bogui, an official from Putian serving in the capital, confirms the popularity of the goddess outside Putian district.78 Another inscription in the Mazu temple in Zhenjiang (1251–1252), written by another native of Putian, Li Choufu, glorifies the Putian elites’ patronage of this cult.79

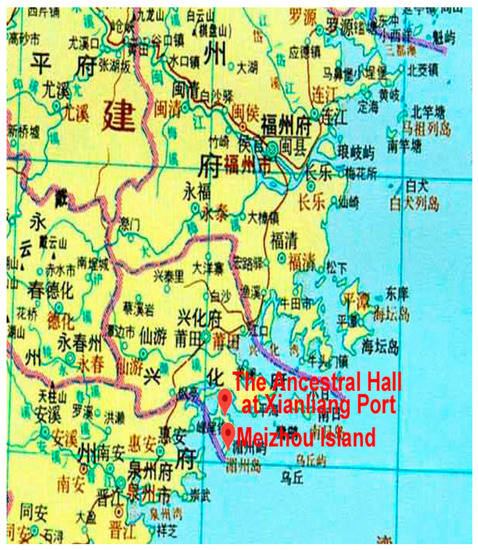

A specific Mazu temple and its local milieu illustrate the integration of the Mazu cult into the Lin of jiumu since the Ming dynasty.80 This temple is situated in Xianliang port (also named Huangluo port), which is a couple of miles from the Meizhou Island (See Figure 1). Building on previous discussions of Mazu’s family lineage, the Lin clan claimed to have originated from Lin Yun, the governor of Shaozhou. According to the Gazetteer of Xinghua Prefecture of the Hongzhi era (1488–1505) (Hongzhi xinghua fuzhi), the Lin clan migrated from Meizhou Island to the inner land, Xianliang port, as a result of an order (qianxi ling) issued during the Hongwu era (1368–1398).81 After it relocated to Xianliang port, the Lin clan of jiumu reestablished the lineage’s ancestral hall, and represented it as the ancestral hall of Mazu. Two inscriptions, including Lin Qingbiao’s a Study of Ancestral Hall in Xianliang port (Xianliang gang zuci kao 1778) and Record of Reestablishing Ancestral Hall of Celestial Empress (Chongjian tianhou ciji 1786), provide detailed information on the historical context. Xianliang gang zuci kao makes reference to the first project of reestablishing this ancestral hall around 1681, after the Lin clan relocated at Xianliang port:

The Ancestral Hall at Xianliang port was established during the Ming dynasty. In the nineteenth year of the Yongle reign (1421), the Emperor had received reports of the numinous miracles performed by the Celestial Empress. Having heard that the ancestral hall was ruined, the imperial court dispatched the Eunuch to renovate it. In the eighteenth year of the Shunzhi reign (1661), people at Xianliang port were forced to immigrate to more inner land under the policy of “Frontier Shift.”82 The Lin descendants placed the paintings of ancestors, including Mazu’s statue, at the Mazu temple of Hanjiang; and then the ancestral hall was ruined. In the twentieth year of the Kangxi reign (1681), the Lin clan was allowed to return back to Xianliang port. The Lin descendants along with the village people collected money and gathered workmen to rebuild the ancestral hall. They also visited the Mazu temple at Hanjiang to welcome [the paintings of] ancestral figures back to the side hall and place Mazu’s statue in the central hall. The spring and autumn sacrifices held by local officials were both performed here.83

Figure 1.

() A Map of the Putian area during the Qing dynasty (1820). The locations of the Ancestral Hall at Xianliang port and Meizhou island as marked. Source: “The map of Fujian province in Qing dynasty” in Tan Qixiang ed. Zhongguo lishi ditu ji: http://www.guoxue123.com/other/map/pic/16/11.jpg.

Another inscription, entitled Chongjian tianhou ciji (1786), offers the historical account of the second project of rebuilding the ancestral hall around 1778.

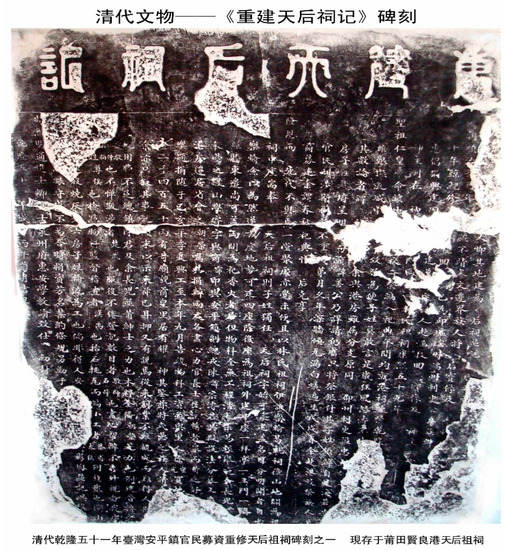

The ancestral hall of Lin built around 1681, after they relocated at Xianliang port, had been ruined by the harsh climate and encroached by termites. The Lin clan decided to rebuild the ancestral hall in the forty-third year of Qianlong reign (1778). Due to a financial shortage and difficulties in accomplishing this grand project, a direct descendant of Lin lineage of jiumu, Lin Qingbiao, who also compiled this inscription, set about to solicit donations to complete the project. Lin Qingbiao ordered his first son, Lin Pei, who assumed an official teaching position at Fengshan county of Taiwan, to raise funds for rebuilding the ancestral hall. Through Lin Pei’s diligence, funds were successfully raised at Ping’an town in Taiwan and the ancestral hall was completed in September of 1786. The rebuilt ancestral hall of Mazu included a central hall, a rear hall, a temple gate, the dragon and tiger gates, a sacrifice pavilion, and temple walls.84 (See Figure 2). Figure 2. The inscription, “Record of Reestablishing Ancestral Hall of the Celestial Empress” (Chongjian tianhou ciji, 1786). Preserved in The Ancestral Hall of the Celestial Empress at Xianliang Port (Xianliang gang tianhou zuci). Source: The website of Xianliang gang zuci, http://www.mzdsd.org/mazu/40283.html.

Figure 2. The inscription, “Record of Reestablishing Ancestral Hall of the Celestial Empress” (Chongjian tianhou ciji, 1786). Preserved in The Ancestral Hall of the Celestial Empress at Xianliang Port (Xianliang gang tianhou zuci). Source: The website of Xianliang gang zuci, http://www.mzdsd.org/mazu/40283.html.

These two texts suggest three strategies adopted by the Lin lineage of jiumu to justify their lineage connection with Mazu and to legitimize their control over Mazu cult at the local level. First, the Lin lineage combined their ancestral worship with the devotion of Mazu by emphasizing her descent from the Lin lineage. As it is mentioned previously, the constructed line extends from “Lin Yun, the goddess’s great grandfather (Lin Baoji), her father (Lin Weique or Lin Yuan), her brother (Lin Hongyi), and the goddess herself.”85 The fact that the ancestral hall was the only temple incorporating both a Mazu shrine and a Lin descent-line shrine (zongci) demonstrates how the linkage was rendered materially and spatially. As it says in Xianliang gang zuci kao, the central palace of the temple enshrined a Mazu statue with a plaque that read: “The Hall of Celestial Empress (tianhou dian).” The side palace housed Mazu’s parents, as well as a memorial tablet of ancestral figures of the Lin lineage with a plaque that reads “The Ancestral Hall of Lin Lineage” (linshi zucu). Placing Mazu’s statue in the central hall symbolizes her primary position in the ancestral hall. By emphasizing the lineage connection with the goddess and locating it at a prominent place of the Lin ancestral hall, the clan legitimized its control over the local Mazu cult, thereby bolstering its claim to spiritual and social authority within local community.

Second, the Lin lineage of jiumu at Xianliang port took full responsibility in establishing, managing, and renovating the ancestral hall. That also helps build a strong connection between Lin descendants and the Mazu cult in the Putian area. Acording to Xianliang gang zuci kao, “Lin descendants along with the village people collected money and gathered workmen to rebuild the ancestral hall.”86 Chongjian tianhou ciji emphasizes Lin descents’ leadership in rebuilding this Mazu ancestral hall: “a direct descendant of the Lin lineage of jiumu, Lin Qingbiao, who also compiled this inscription, set about soliciting donations to complete the project.”87 Lin Qingbiao and Lin Pei, both heirs of Mazu’s lineage, were particularly crucial for the success of reestablishment of Mazu’s ancestral hall. The Lin descents organized the two constructions of ancestral hall, setting themselves apart from the rest of the local society and further justifying their leading role in managing the hall and taking charge of sacrificial activities dedicated to Mazu.

Third, the Lin lineage made use of the policy of state canonization of Mazu cult to gain official recognition of Mazu’s ancestral hall. As we have seen in the section of “Mazu as Imperial Protector: The Expression of Local Elites’ Loyalty to State”, the state canonized and standardized local cults by granting honorable titles and inscribing local deities into the register of sacrifices. This official and public recognition bestowed prestige unto local cults, strengthening their local hold and opening the possibility of becoming translocal. Local elites actively sought official titles for the local gods they supported as one way to enhance their social and political status.88 In other words, the local elites considered the political system of canonizing local cults as an important source of legitimacy for their control over Mazu worship in local society.

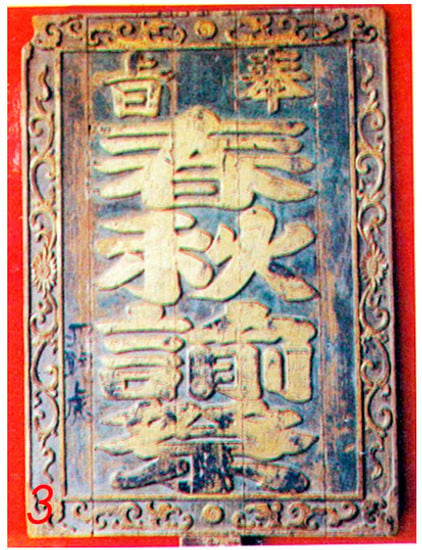

Regarding practices at the Ancestral Hall of Mazu, Lin descents also used the policy of state canonization to gain official recognition for both Mazu and themselves. As Xianliang gang zuci kao reports, “the spring and autumn sacrifices held by the local officials were both performed here (around 1681–1735).”89 The performance of official sacrifices at Mazu’s ancestral hall at Xianliang port suggests that this hall was inscribed in the official register of sacrifices. However, according to Chongjian tianhou ciji, the magistrate of the Putian district petitioned the central government, requesting that the local government perform the official sacrifice dedicated to Mazu at the Wenfeng Palace, which is closer to the local government, rather than in Mazu’s ancestral hall at Xianliang port, which is eighty miles away. As a result, the official sacrifice held at the Mazu’s ancestral hall was suspended starting around 1736. To regain the official honor of performing official sacrifice at Mazu’s ancestral hall at Xianliang port, “Lin descendants of jiumu petitioned the prefect (zhifu) of Xinghua prefecture, requesting that the sacrifice at the hall should be inscribed in the register of sacrifice.”90 The petition was approved by Xinghua prefect, and beginning in the 1770s, the Lin descendants of jiumu at Xianliang port were solely responsible for organizing and performing the official sacrifice to Mazu twice each year, in spring and autumn, with the financial patronage of local government (see Figure 2). Due to the efforts of the Lin lineage of jiumu, Emperor Qianlong issued an edict to perform official sacrifices at the ancestral hall of Mazu at Xianliang port in the fifty-third year of his reign (1788), entreating the local officials to perform the sacrifices with the ritual of three prostrations and nine kowtows at this specific hall in spring and autumn.91 That is further attested to by a wooden plate dating to Qianlong’s reign, which reads “performing official sacrifices in spring and autumn ordered by imperial edict” (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The Wooden Plate, “Performing Official Sacrifices in Spring and Autumn Ordered by Imperial Edict.” Preserved in The Ancestral Hall of the Celestial Empress at Xianliang Port. Source: Provided by the Temple management board of Xianliang gang zuci.

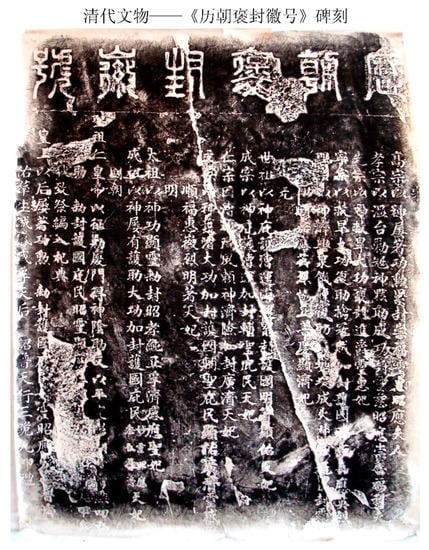

Additionally, Lin descendants also made use of the granting titles policy to promote the official recognition of this ancestral hall. For example, an inscription entitled “A List of Imperial Titles Conferred by Different Dynasties” (see Figure 4), includes thirteen honorific titles granted by imperial emperors, ranging from Emperor Guangzong of Song dynasty (1189–1194) to Emperor Qianlong (1736–1799) (see Table 2).92 The list spans the whole history of Mazu’s canonization, tracing her promotions from Lady, to Consort, Celestial Consort, Celestial Empress, and finally Holy Saint Mother. After Emperor Kangxi conferred the title of Celestial Empress upon Mazu in 1684, Mazu’s Ancestral Hall was renamed as “State Conferred Ancestral Hall of the Celestial Empress” (Chifeng tianhou ci). This declaration not only strengthened the Lin lineage’s local leadership, but also asserted their official and ritual privilege over the increasingly popular cult of the goddess, setting them apart from the rest of local community.

Figure 4.

The Inscription of “A List of Imperial Titles Conferred by Different Dynasties.” Preserved in The Ancestral Hall of the Celestial Empress at Xianliang Port. Source: Provided by the Temple management board of Xianliang gang zuci.

Table 2.

A table includes thirteen honorific titles granted by emperors, ranging from Guangzong of Song dynasty (1189–1194) to Qianlong (1736–1799).

A brief account of current practices at Mazu’s ancestral hall at Xianliang port gives a glimpse of how Lin descendants still continue to emphasize the historical and lineage connection between the Lin of jiumu and Mazu worship.93 In 1984, the Lin descendants of jiumu initiated the project of rebuilding the existing ancestral hall of the Celestial Empress which was completed in 1988. It refurbished the original structure of the ancestral hall built in Qing dynasty, consisting of a central hall, “The Hall of the Celestial Empress”, and a side hall, “The Ancestral Hall of the Lin Lineage”, which enshrines various figures of the Lin lineage of jiumu, including Lin Pi, Lin Yun, Lin Yuan, Lin Yu, Lin Baoji, Lin Fu, Lin Weique/Lin Yuan (Mazu’s father), Lin Hongyi (Mazu’s brother), and Lin Mo (Mazu). Thus, the reconstruction exactly duplicates the Lin genealogy of jiumu recorded in Lin Qingbiao’s Chifeng tianhou zhi. It is worth noting that the central shrine of “The Ancestral Hall of the Lin Lineage” also consecrates Mazu’s parents (see Figure 5). The plaque on the top of the shrine, entitled “The Lasting Reputation of Loyalty and Filiality (Zhongxiao liufang)”, emphasizes Mazu’s virtues of loyalty and filiality, which I have discussed in previous sections. The ancestral hall also preserves several antiques dating to Qing dynasty, a wooden plate of “Performing Official Sacrifices in Spring and Autumn Ordered by Imperial Edict” (Figure 3), the inscription of “A List of Imperial Titles Conferred by Different Dynasties” (Figure 4), and the inscription of “Record of Reestablishing the Ancestral Hall of the Celestial Empress” (Figure 2). These antiques not only serve as valuable sources for the history of Mazu worship, but also as makers of distinction, signaling the temple’s uncontested status as the only ancestral hall dedicated to Mazu at her birthplace.

Figure 5.

The statues of Mazu’s parents at the central shrine; Mazu’s statue on the front in the Ancestral Hall of the Celestial Empress at Xianliang Port. Source: Author’s Photography.