Abstract

Based on a selection of examples from the sculptural art of Andhra, the paper discusses what possibly motivated the inclusion of motifs and stylistic elements from the ancient Mediterranean into the Buddhist art of the region. While in some cases such adaptations may have been driven by the need to find suitable solutions for the depiction of critical events or by the fact that a foreign motif tied in perfectly with already existing concepts, and thus, reinforced the message to be conveyed, in other cases no such reasons can be detected. Artists seem to have used foreign image types and stylistic variations deliberately to show their supreme craftsmanship or to add aesthetic sophistication to the image programme. The artists of Andhra, therefore, can by no means be regarded as epigones slavishly adhering to the examples set by the Mediterranean; the region—which is the place where narratives later spreading over large parts of Asia and Europe were first depicted—rather has to be regarded as on par with the classical cultures of Greece and Rome in terms of artistic versatility and creativity.

1. Pictorial Motifs from the West in the Reliefs of Andhra

What causes pictorial elements from one culture to suddenly appear in a far-off location? The question is a valid one. The similarities between the forms are often very distinctive; so much so in fact that we can rule out any possibility that the forms developed independently of one another. In Stilfragen [Problems of Style], published in 1893 (Riegl 1893), Alois Riegl (Iversen 1993) presented the journey of the “palmette frieze” (anthemion), an ornament traveling through remote areas and varying time periods across Babylon, Egypt, the Mediterranean, and the Persian world. The same ornament appears on the drums of several Aśokan pillars. To say that this iteration of the ornament developed independently and originated in India would exclude India from the process for which the anthemion serves as a visual representative: an intense cultural exchange that took place in antiquity, wherein aspects of style, art, and aesthetics were passed across cultural borders. In his well-known book on ornaments, Ernst Gombrich (1979) formulated the psychological rules leading to the continuous adoption of motifs instead of inventing new ones. He wrote of the “power of inertia” and the “force of habit”.

In comparison with the art of the other regions in the period of antiquity, the art of India developed late. Even if we presume art objects were made in perishable materials, the general statement appears to be valid that the spiritual genius of the vedic culture loomed over the creation of a record of the religion through illustration and through writing down the texts. Art in stone, which could survive the ages, first appears along with religions denying the authority of the veda. A need to illustrate their religious beliefs led the artists to adopt the foreign pictorial formulas, seemingly without paying attention to the original meaning of these pictorial elements. The comparable representations of Zeus kidnapping Ganymede and Gandharan representations of Garuḍa kidnapping nāgas are well-known (see e.g., Stoye 2008). Here, a foreign form was used to illustrate a pan-Indian myth that was itself already ancient.

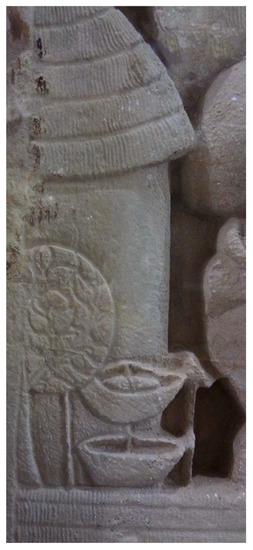

In Gandhara, Buddhist art was based on Western aesthetics, which had been familiar in the area for generations (see e.g., Stone 2008a). The need to create illustrations for the narratives led to adaptations of many motifs from the Mediterranean World. These foreign formulae were often ready-made; instead of creating appropriate iconography for the events to be illustrated, the artists simply adopted those that were already in existence. For us, such adaptations are sometimes difficult to comprehend, and it is easy to misunderstand the intended meaning of the scenes. In the reliefs depicting, for instance, the nāgarāja Kālika, who emerged from the River Nairañjanā to praise the Bodhisatva proceeding to the place of enlightenment, the nāga is shown standing inside a well that is characterised by means of a lion-head fountain clearly reflecting models from the Mediterranean world (Figure 1).1

Figure 1.

Gandhara, Sikri, Lahore Museum, no. 1277, G-6 © photograph Muhammad Hameed.

The artisans of Andhra, ancient Āndhradeśa, which also had strong trade relations with Rome,2 do not confront us with rote or unthinking adaptations of Mediterranean motifs. The reason for this might be the fact that the Buddhist art of Andhra is older than Gandhara. Its earliest production is contemporary with the art of Bharhut, and was already extant around 100 BCE. The artists’ workshops of the developed Andhra art, after 100 CE, were much more “experienced” and could rely on generations of prior artworks; foreign models were not needed. This does not mean, however, that they foreswore the Western models completely. In fact, the opposite is true. The art of Andhra is, to a great extent, “westernised”.3 The borrowed models were, however, not adopted as part of the initial creation of the representations, but were instead used to refine already-existing models. This may have been done to make the models appear more modern or to follow trends, or may have served as a method of better presenting the religious material.

An image often depicted in Indian art featured the Bodhisatva arriving in the form of an elephant and entering into the body of Māyā. This image can be traced from the earliest period of Bharhut up to the Gupta period where it appeared in Sarnath and Ajanta.4 The artisans were confronted with a doctrinal problem. The Bodhisatva should have entered the body of his mother from the right side (the side from which he was born); however, as a modest woman, Māyā would have slept on her right side, i.e., with her left side towards the approaching elephant. This issue must have inhibited the establishment of a fixed iconography to be used for this event, as Māyā is shown lying on her right side,5 or on her left side, and occasionally even with her back towards the viewer (Quagliotti 2009).

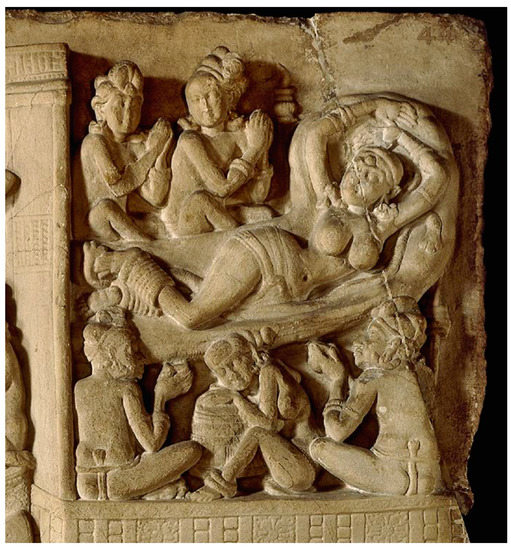

It appears that in Andhra, the sleeping Māyā was depicted several times using a Western pictorial model (Zin 2015). The prototype for this model is a representation of the sleeping Ariadne, an illustration of a narrative that was popular in Rome and very often represented among others on small objects which could easily be taken on a maritime journey.6 The myth narrates the story of Ariadne, who was left alone by Theseus on the island of Naxos. Deserted and in despair, Ariadne falls asleep to be found by the pageant of Dionysus, whom she will eventually marry. Ariadne is shown sleeping on a rock covered with an animal pelt. A convention in Mediterranean art dictated that sleeping figures were to be shown with their arms above their heads; this first appears centuries earlier in Greece (McNally 1985), perhaps to differentiate them from the dead. Several reliefs from Amaravati, like the oft-published stele located in The British Museum (Figure 2),7 repeat this model of the sleeping Ariadne as a representation of Māyā. This is evident not only because she is lying with her arms above her head, but also because the object she is lying on is not a bed, but rather a stone formation, covered with an animal pelt with distinctively executed paws. Several reliefs have been preserved, and we are able to determine that such representations of the sleeping figure of Māyā appear in Amaravati in the 1st century CE, and disappear again after one or two generations when the artisans return to the “Indian prototype” featuring the more modest figure of Māyā lying on a bed.

Figure 2.

Amaravati, The British Museum, London, no. 44 © The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved.

At this point, a considerable difference between Gandhara and Andhra becomes obvious. In Gandhara, the well equipped with the lion-head fountain was necessary to illustrate a water reservoir and to illustrate the Buddha crossing the Nairañjanā River. Apparently without it, the representation of this episode from the Buddha’s life would have been difficult if not impossible. In the present case, artists already had an existing motif, and the borrowed model was used as a modification. The question is—to what purpose? Unfortunately, there is no satisfying answer to this question. It is possible that this was done in order to avoid the doctrinal controversy mentioned earlier. The figure of Māyā as depicted in Ariadne’s model is not really lying on either side. However, it might also have been done to keep up-to-date with the latest trends in art from abroad, or for aesthetic reasons, in order to create a pretty scene for the viewer.

Two further examples serve as evidence that any of these possibilities might be correct. In Kanaganahalli, the reliefs of the dharma-cakra display a lion’s head in the hub of the wheel.8 This is certainly an adaptation of an image in use in Rome; there, carriage wheels were often decorated in this manner. In the Buddhist context, however, these same representations take on an additional religious meaning as the dharma-cakras symbolise Buddha’s sermons and the Buddha was well-known for preaching with the voice of a lion.

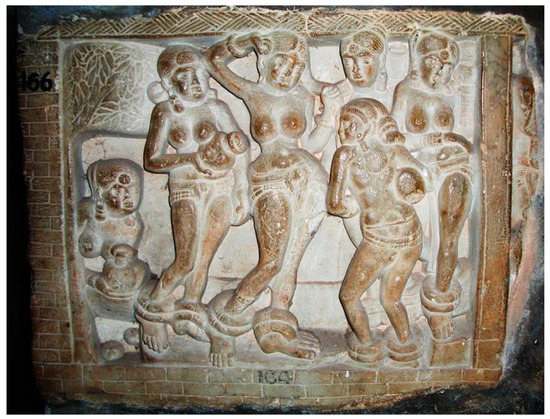

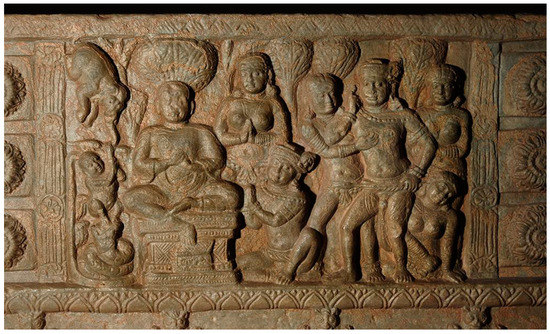

“Aphrodite Anadyomene”, the goddess of love who rose from the sea, also found her way to Andhra (Stoye 2006). In many Mediterranean representations Aphrodite/Venus Anadyomene is shown wringing out her hair in a very characteristic gesture, holding wisps of hair on both sides of her head.9 The goddess reappears in Amaravati, although she is not emerging from the sea; here, she is depicted being bathed in Indian fashion, with servants pouring water over her out of pots (Figure 3).10 Stoye suggested that this relief is meant to represent Māyā, but this interpretation is questionable. In Andhra, scenes from the Buddha’s life story are always repeated multiple times, and we do not encounter the bathing Māyā again, neither modelled after Anadyomene nor in any other manner of depiction. The relief is probably not meant to be a “narrative representation” at all, at least in the sense that it illustrates any particular story. The relief was installed on one side of two quadrangular objects which have depictions of yakṣas and other non-narrative illustrations on the other sides. The “Venus Anadyomene” appears to have been depicted in Amaravati simply for the sake of her beauty, perhaps in connection with the cult of the yakṣinīs.

Figure 3.

Amaravati, Chennai Government Museum, no. 166 © photograph Wojtek Oczkowski.

The brilliant artists of Andhra applied Western models with obvious pleasure; one gets the impression that they were eager to adopt models from Rome, not only in order to create their own pictorial expression, but also to demonstrate their mastery in working with these Roman models. The depictions of human figures serve as an excellent demonstration of such mastery.

In general, Indian art is disposed towards a depiction of human figures that is not naturalistic. The figures do not usually illustrate particular individuals, but instead are more general visualisations of types, such as “king”, “woman”, “servant”, etc. It is rare that we see depictions of elderly or ugly figures. In Kanaganahalli, we see an individualised depiction of a very young woman with tiny breasts and narrow hips,11 which is quite unique. It is only in the art of Gandhara and Andhra, with their extensive contact with the classical art of the Mediterranean, that we encounter representations of human figures with visible musculature. In Andhra, these muscular human figures gain popularity around 100 CE.

We can observe, however, that not all artisans created figures with visible musculature. Although such naturalistic representations do exist, the lifelike depiction of the body does not seem to have been the foremost objective for the artists. It appears to be more of a wish to show the figures for their own sake, and to depict their beauty in motion. Among the Amaravati reliefs, there are some masterpieces. Their creators appear to have chosen to pose the figures so that they would be best able to represent the musculature.

2. A Masterpiece of Art from Andhra and the Unidentified Narrative It Illustrates

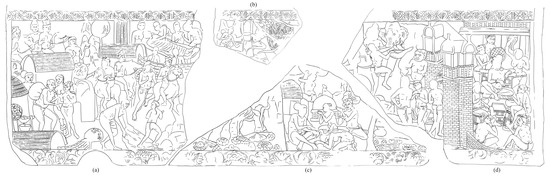

Let us look more closely at one such masterfully executed relief from Amaravati as an example. The relief, part of the coping stone of the great railing, is presented here for the first time as a single entity in a reconstructive drawing (Figure 4) that joins four fragments kept in the Chennai Government Museum (nos. 53,12 54,13 7514 and 12415). It is not for the first time that separated pieces of reliefs from Andhra have been completed into a whole (Parimoo 2002; Zin forthcoming) but this is probably the most important case. For the drawing, photographs from previous, older publications have been used, as some details, especially along the edges of the fragments, have since been lost to us. We can be certain of the order and positioning of the three fragments along the lower edge (Chennai, no. 124 on the left, no. 54 in the middle and no. 75 on the right); there is a stone sediment line running through all three pieces that confirms their placement, although the distance between the fragments might have varied slightly.

Figure 4.

Reconstructive drawing of four fragments of a coping stone, Amaravati, Chennai Government Museum, nos. 53, 54, 75 and 124 © Monika Zin. (a) Chennai Government Museum, no. 124. (b) Chennai Government Museum, no. 53. (c) Chennai Government Museum, no. 54 (d) Chennai Government Museum, no. 75.

The additional fragment of the coping stone (Chennai, no. 53) appears to represent the same youth in front of a stone formation. To the right, we see part of another scene: an archer, in the act of shooting. It is not possible to reconstruct a point-to-point connection of this piece to the rest of the relief, although it is nearly certain that the fragment is indeed part of the same relief, as evidenced by the inscription. Its akṣaras are identical with the script on two of the other fragments. The inscription is on one line above the upper ornamental pattern. If we read it together with the fragment featuring the archer it goes thus:

rano sirisivamakasadasa ◊ pāniyagharikasa he ? /// mahāgovalavabālikaya ◊ [n]. /// (ka)ya ◊ sak(u)līgāya ◊ mahācetiye °utarāyāke ◊ °unisa dāna16

The script references the donation of the coping stone (unisa) by the superintendent of the water house (pāniyagharika) of King Siri Sivamakasada and the daughter of a royal official in charge of cattle (mahāgovalava, Skt. mahāgovallabha). From the inscription, we also learn that the relief was located in the vicinity of the northern entrance (utarāyake) to the great stūpa. The reference to King Sada, named in the inscription, allows us to date the relief quite early, probably to the 2nd century CE if not earlier.

The unconnected fragments of the relief have been separately explained. The smallest fragment was among the unidentified elements (Sivaramamurti 1942, p. 246), while three others have been explained on the basis of three different narratives. The left side was thought to be the story of Kavikumāra identified by Sivaramamurti (1942, pp. 215–16) as an illustration of the narrative re-told in the Bodhisattvāvadānakalpalatā 66,17 the middle was thought to be a depiction of the Pali Mahāpaduma-jātaka18 (identif.: ibid., pp. 220–22) and the right side was explained on the basis of the Mihilamukha-jātaka19 (identif.: ibid., pp. 218–19).

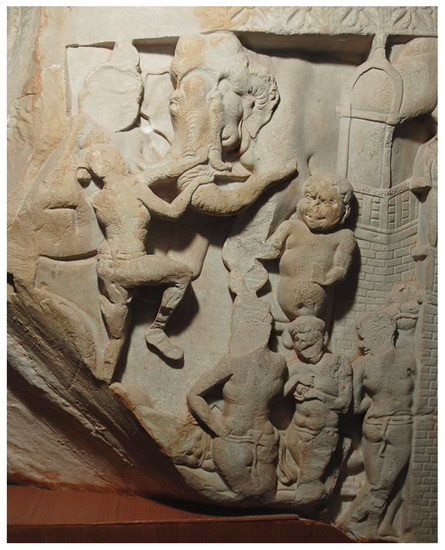

When we group the fragments into a single representation, the explanation of the narrative content of the right fragment as the Mihilamukha-jātaka—an explanation that is problematic in itself—can safely be ignored. The Mihilamukha-jātaka is a narrative about an elephant who became aggressive after overhearing a conversation between unsavoury characters and became sweet-tempered again after overhearing a conversation between good people.

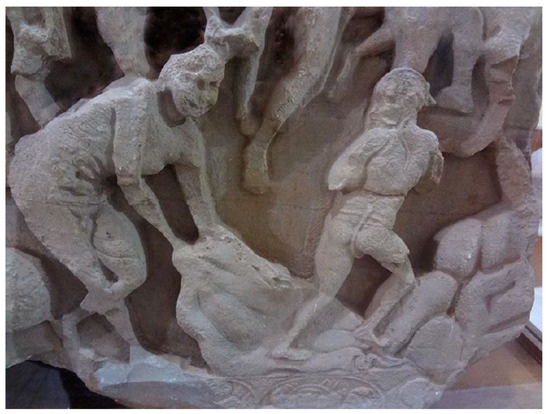

The elephant in this relief is shown in motion (Figure 5), and the main character of the depiction appears to be a youth with a tiny bun at the back of his head, clad only in a loincloth. The youth is jumping at the face of the elephant with a stick in his right hand (an aṅkuśa hook is not present in the depiction). The same youth appears again in the scene on the right, inside the city, conversing with the king (Figure 6) and certainly plays the main role in both other fragments of our relief.

Figure 5.

Part of relief no. 75 in Chennai Government Museum © photograph Wojtek Oczkowski.

Figure 6.

Part of relief no. 75 in Chennai Government Museum © photograph Wojtek Oczkowski.

The explanation of the left part of our relief on the coping stone (Chennai no. 124) as the narrative of Kavikumāra is convincing, as the relief does indeed illustrate two of the adventures of Kavikumāra, a youth who escaped from his pursuers. It shows how Kavikumāra was carried away disguised as a corpse (Figure 7), and another time when he was saved by a dyer who carried him off along with cloth (Figure 8). The narrative, as told in the Mūlasarvāstivādavinaya (repeated in the Bodhisattvāvadānakalpalatā) tells the story corresponding in nearly all details with our relief:

… he came to the house of an old woman who hid him away. From thence, after his body had been anointed with oil of mustard and sesame, and laid upon a bier as if had been a corpse, he was carried out to the cemetery and deposited there (…).The youth reached a hill-town, entered into the house of a dyer, and told him his story. So when his pursuers began to search the town, the dyer placed the youth in a clothes chest, which he set upon an ass, and took him out of the town to a bath-house, where he left him.(Schiefner 1906, p. 275)

Figure 7.

Part of relief no. 124 in Chennai Government Museum © photograph Wojtek Oczkowski.

Figure 8.

Part of relief no. 124 in Chennai Government Museum © photograph Wojtek Oczkowski.

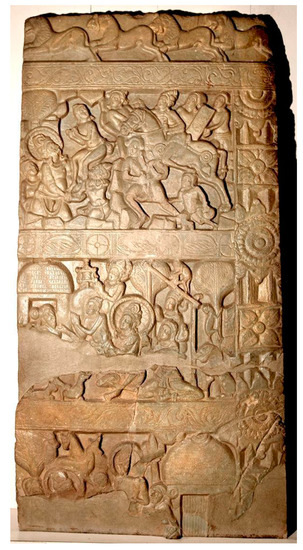

The Kavikumāra narrative was apparently depicted in a relief in Nagarjunakonda, too (Figure 9);20 the upper register of the slab shows mounted pursuers approaching the house with the corpse, the lower register shows the youth chased by the riders across the rocky landscape.

Figure 9.

Nagarjunakonda, Archaeological Site Museum, no. 28 © photograph Wojtek Oczkowski with kind permission of ASI.

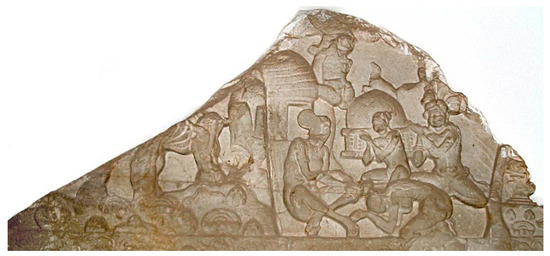

There are good reasons to connect the lower middle fragment of the copingstone (Figure 10) with the Mahāpaduma-jātaka. These ancient verses tell of a nāga king who caught the youth as he fell from the rocky cliff (Mahāpaduma narrates):

“A Serpent mighty, full of force, born on that mountain land,Caught me within his coils; and so here safe from death I stand.”(Jātaka, transl. vol. 4, p. 121)

Figure 10.

Amaravati, Chennai Government Museum, no. 54 © photograph Monika Zin.

Our relief does indeed show nāgas emerging from a pond and stretching their arms up as if to catch someone. This representation is also repeated in Nagarjunakonda (Figure 11)21 where the youth, falling into the abyss, and being saved by the nāgas, is easy to discern.

Figure 11.

Nagarjunakonda, Archaeological Site Museum, no. 30 © photograph Wojtek Oczkowski with kind permission of ASI.

This, however, marks the end of the similarities between the fragment and the text of the Mahāpaduma-jātaka. The scene on the right in Figure 10 and the lower register of Figure 11, in which a nāga couple and the youth worship an ascetic in the forest does not appear in the Mahāpaduma-jātaka. The same is true for the upper part of Figure 10, featuring the same youth climbing up a tree to escape from a dog. Interestingly, however, this last storyline including dogs and a tree is part of the narrative of Kavikumāra:

The Yakṣa Pingala was sitting at a certain spot surrounded by his dogs (…). So he set the dogs on the youth. But the youth outstripped them and climbed up the tree.(Schiefner 1906, pp. 276–77)

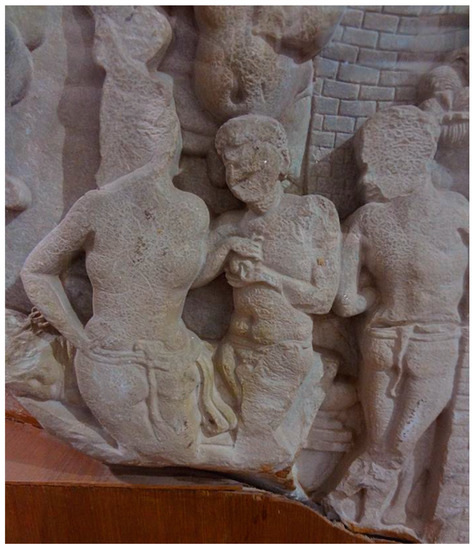

Further episodes depicted on our Amaravati relief (Figure 4) have counterparts neither in the Mahāpaduma-jātaka nor in the narrative of Kavikumāra. An important part of the representation is certainly taken up by a male figure lying on a bed to the left of the city gate. The bed (its spherical legs are visible in the middle and right fragments) (Figure 4 and Figure 5) is located at the side of a lotus pond. We see three men standing (Figure 12)—the middle one is holding a round object in front of his chest—who seem to be arguing over the figure of the lying man, or perhaps, are arguing with him. There is no satisfactory explanation for this scene. The same is true for the scene featuring the elephant,22 (Figure 5) the ugly dwarves and the scene with the archer. The conversation with the king on the right side of the relief (Figure 6) does not match any of the sources: Mahāpaduma becomes a hermit, and his father visits him in the forest; Kavikumāra reaches the king while disguised as a woman and kills him.

Figure 12.

Part of relief no. 75 in Chennai Government Museum © photograph Wojtek Oczkowski.

The literary basis that provided the material illustrated in the relief has been lost. This fact is no surprise to us (cf. Zin 2012, 2016); the inscriptions provide us with the name of the Buddhist school in whose monasteries these narrative reliefs appeared: it was the school of the Mahāvinaseliyas (Mahāvinaśailas) or Aparamahāvinaseliyas (Aparamahāvinaśailas).23 The scripture of the school has not survived the ages.24

Furthermore, of our relief featuring the youth in flight, we can state that the literary basis has been lost, as there is no existing narrative that describes all of the episodes. Only a few adventures of the youth on the run have survived in the narratives of Kavikumāra and Mahāpaduma.

Since nothing certain can be said about the identification of the narrative, let us concentrate first on the masterful representation itself, and look closer at the composition of the entire piece as well as the representations of the human figures.

In our relief, on the coping stone (Figure 4), direct adaptations of a particular Western iconography (as in the case of Māyā modelled on Ariadne) cannot be found. The art of the Mediterranean rarely depicts flight; when it does, the elements of the depictions featuring men running or climbing a tree might look similar, but it is hardly possible to depict the act of flight differently (for comparison, we can look to the paintings showing the flight of Odysseus from the cannibal Laistrygones).25 It remains to be seen whether other aspects of Western artistic traditions were incorporated into this relief in a more subtle way.

The order of the events depicted in the relief cannot be established with certainty. The scenes appear to be arranged according to the spatial principle (Schlingloff 1987, pp. 227–80). The area representing the village is visible on the left side of the relief, the area representing the wilderness is in the middle, and the city can be seen on the right. The scenes placed in the three areas are, therefore, not necessarily required to be in any chronological order, although it does seem that the narrative proceeds from left to right and ends with the conversation with the king.

The relief might display some Western influences, but it is filled with Indian realities—note the particular containers on the lower left edge (Figure 13), which are certainly meant to characterise the dyer’s workshop. One can also note the clichés which make the image legible to the viewer; the pursuers are on horses and wear turbans, while the youth’s helpers do not. These are good people with little or no money.

Figure 13.

Part of relief no. 124 in Chennai Government Museum © photograph Wojtek Oczkowski.

In this relief, animals and humans are depicted in motion, or at the very least, are depicted as active, gesticulating figures. The depictions of human bodies are anatomically correct, with visible musculature. The representations of people turned away from us, with their back to the viewer, are especially striking. These poses place the figures in interesting positions that are difficult to depict. Here, the undeniable influences from the West become visible.

The representations of persons shown from the rear (in art history, these are labelled with the German term “Rückenfigur”) first appear in the Mediterranean World, beginning in the 6th century BCE, and are continuously present through the ages (Koch 1965). Persons depicted in such a manner add a level of dynamism to the depictions. Even though other examples are known, they appear mostly in vibrant scenes depicting activities such as dancing or fighting. The artists manifest their skills by means of such depictions, while generally limiting their inclusion in scenes to one or two such figures per representation. When an ensemble of three figures is depicted, such as the three dancing Graces or three smithing Cyclopes, only one of the figures is shown from behind.

This is not the case in our relief. Of the groups of three—three men on a side of the bed (Figure 12) and three nāgas emerging from the pond (Figure 10)—two of the three are depicted in this rear-facing view. The youth released from the bale of cloth is turning towards the dyer (Figure 8), and while climbing up the tree (Figure 10) and jumping at the elephant’s face (Figure 5), he is also turned so that we see his back. Altogether, the preserved part of the relief depicts no less than 13 figures shown from behind. A 14th “Rückenfigur” from the back side of the right fragment (Figure 14)26—which was certainly executed by the same hand—can be added to our total count. The man is pulling a garland out of the mouth of an incredibly well-executed dwarf.

Figure 14.

Rear side of relief no. 75 in Chennai Government Museum © photograph Wojtek Oczkowski.

When faced with the numerous depictions of figures shown from the back, one gets the feeling that the artist rejoiced at any chance available to depict the muscular men’s backs; we might even begin to wonder whether the artist chose the subject of flight simply in order to demonstrate his skills. The model for the depictions of the persons may be Western, but the perfection of the artists in using it along with its specific application in visualizing the particular narrative is Indian.

3. The Lost Narrative in the Relief and Its Importance for the Narrative Motifs of Mankind

At this junction, we can return to the depicted narrative for which the exact literary basis remains unknown, a narrative for which only singular motifs in different literary sources have survived into the present day. The relief definitely depicts a narrative about a youth who is being pursued. The reason for this pursuit is not represented. In the Mahāpaduma-jātaka it is the king who sent out the pursuers. In this narrative, the king’s wife accused the youth (the king’s son from a prior marriage) of sexual harassment (“Potiphar motif” in the study of mythology). Kavikumāra is the younger prince, living in disguise in a fishermen’s village. It was prophesied that he was going to kill the king and become the king himself; those in pursuit of him were sent by his older brother (“Schicksalskind” motif).27

Even if we are not able to identify the exact narrative, we can be certain that the story depicted in the relief belongs to the topics that were widespread in the literature of mankind; here, we find a narrative of a “child of destiny” able to escape from all attempts on his life in order to fulfil his fate. Such narratives are often connected with prophesies about the boy’s splendid future (in many cases, he is to become king). The child’s destiny is realised in the end, even if the child is initially neglected or abandoned and is made to face numerous threats or trials. These stories often feature attempts to murder the child (motif “Gang zum Eisenhammer”, Aarne and Thompson 1961, no. 910) and a motif of a letter which is in the boy’s possession, carrying a message of his persecution (motif “Uriasbrief”, Aarne and Thompson, no. 930). The boy in this narrative is able to survive all of the perils he faces due to assistance from people and animals he meets along the way.

The origin of these widespread motifs cannot be traced back to a singular source, but, as demonstrated as early as 1870 by Weber and later in more detail by Schick (1912), the developed motif—featuring prophesies about the youth’s destiny, figures who attempt to expose him and attempts to murder the boy—appears first in Indian narratives, and can only later be traced through numerous Arabic and European sources, including the narrative of Hamlet. The Indian sources the German scholars list date in part to a quite early period. The oldest of these sources is a jātaka preserved in a Chinese translation from the 3rd century,28 and the story of Ghosaka in the Dhammapadaṭṭakathā29 in the 5th century. Other texts, like the Jaina Kathākośa (transl.: 172) and Campakaśreṣṭhikathānaka (cf. Weber 1883; Hertel 1911) or the Vaiṣṇava Jaiminibhārata (German transl. in Weber 1870), came much later but may, of course, contain repetitions of narratives from much earlier sources. None of the known narratives corresponds well with our relief; the Mahāpaduma-jātaka and the narrative of Kavikumāra are much closer. Research shows, however, that many narratives of this sort were circulating in India. The sources are partially old (the gāthās of the Mahāpaduma-jātaka); as was shown above, the literary sources which have survived the ages contain only some parts of the illustrated story. The fact is that the evidence for the entire narrative is not these text sources, but instead, our Amaravati relief, which dates from the 2nd century or perhaps even earlier, is a masterpiece of Andhra art, most probably illustrating a lost literary tradition, likely from some scripture of the Mahāvinaśaila School.

This is an important conclusion—it shifts the earliest dating of this literary topic further back than previously thought, and connects it undeniably with India. The same can be said of the world-famous parable featuring the “Man in the Well” (Zin 2011). The earliest preserved references to this parable are its representations in Andhra (Figure 15).30 The parable, a moral tale about a man for whom some drops of honey made him forget the misery of his condition, were incorporated in illustrations of a now-lost narrative of a king converted by a monk apparently by means of this story. Indian literary versions of the parable, which were carried all over the world through the Pañcatantra and the Balraam and Josaphat, all date later than the depiction at Andhra.

Figure 15.

Nagarjunakonda, Archaeological Site Museum, no. 24 © photograph Wojtek Oczkowski with kind permission of ASI.

It was certainly an exaggeration when Theodor Benfey (1809–1881), the pioneer of comparative fairy-tale research, called India the “Heimat aller Märchen” [homeland of all fairy tales]. Yet, the relief under discussion illustrating the narrative of a youth who escaped from his pursuers, as well as other, better-known examples of ubiquitous narratives first depicted in India like the “Man in the Well”, show why Benfey reached his assessment of the crucial role of India.

The most important aspect of our relief (Figure 4) is, therefore, that it provides evidence of a reciprocal exchange between Andhra and the Mediterranean. We are confronted with narrative motifs that originated in India and spread to the West; their earliest references are the pictorial representations in Andhra—which have in turn been executed including substantial influences from the art of the West.

The artists of ancient Āndhradeśa who created the earliest visual representations of a number of narratives that in later times spread over large parts of Eurasia were certainly on a par with their Greek and Roman colleagues—by no means depending on foreign input, but consciously selecting those elements suitable for inclusion and using them confidently to perfect their compositions and show off their technical and aesthetic abilities. Moreover, their creations in several cases illustrated narratives that to the best of our knowledge were developed in India and spread over large parts of the old world.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

Primary Sources

Bodhisattvāvadānakalpalatā. Edited by P. L. Vaidya. 1959. Avadāna-Kalpalatā of Kṣemendra, 1–2. Durbhanga: The Mithila Institute.Dhammapadaṭṭhakathā. Translated by Eugene Watson Burlingame. 1921. Buddhist Legends, 1–3. Cambridge, MA: Harvard, Harvard Oriental Series 28–30.Jātaka. Translation and Edited by Edward B. Cowell. 1895–1907. The Jātaka or Stories of the Buddha’s Former Births, Translated from the Pāli by Various Hands, 1–6. Cambridge: Pali Text Society.Kathākośa. Translated by Charles Henry Tawney. 1895. The Kathākośa or, Treasury of Stories, transl. from Sanskrit Manuscripts. London: Royal Asiatic Society. Oriental Translation Fund, N.S. 2.Mūlasarvāstivādavinaya, Saṅghabhedavastu. The Tibetan Tripitaka: Peking edition kept in the Library of the Otani University, Kyoto. Reprinted under the supervision of the Otani University, vol. 42. Tokyo/Kyoto 1957.Taishō Shinshō Daizōkyō. Edited by Junjirō Takakusu, Kaigyoku Watanabe, and Genmyō Ono. Tokyo 1924–1934.Secondary Sources

- Aarne, Atti, and Stith Thompson. 1961. The Types of the Folktale, A Classification and Bibliography, Second Revision (FFC 184). Helsinki: Suomalainen tiedeakatemia. [Google Scholar]

- Aramaki, Noritoshi, D. Dayalan, and Maiko Nakanishi. 2011. A New Approach to the Origin of Mahāyānasūtra Movement on the Basis of Art Historical and Archaeological Evidence. A Preliminary Report on the Research. Project (C) no. 20520050. Tokyo: Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research, The Japan Society for Promotion of Science. [Google Scholar]

- Asplund, Leif. 2013. The Textual History of Kavikumārāvadāna: The Relations between the Main Texts, Editions and Translations. Ph.D. dissertation, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden. [Google Scholar]

- Bachhofer, Ludwig. 1929. Early Indian Sculpture. Paris: Pegasus. [Google Scholar]

- Begley, Vimala, and Richard Daniel De Puma, eds. 1991. Rome and India. The Ancient See Trade. Wisconsin: The University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, James. 1887. The Buddhist Stupas of Amaravati and Jaggayyapeta in the Krishna District, Madras Presidency, Surveyed in 1882. Archaeological Survey of Southern India 1. London: Trübner. [Google Scholar]

- Chavannes, Édouard. 1910–1934. Cinq cents contes et apologues, extraits du Tripiṭaka chinois et traduits en français. Paris: Leroux, pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Cimino, Rosa Maria, ed. 1994. Ancient Rome and India. Commercial and Cultural Contacts between the Roman World and India. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal. [Google Scholar]

- Enzyklopädie des Märchens. 1977–2015. Enzyklopädie des Märchens. Handwörterbuch zur historischen und vergleichenden Erzählforschung. 1977–2015. Edited by Kurt Ranke, Rolf Wilhelm Brednich and Hermann Bausinger. Berlin and Boston: de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Evers, Kasper Gronlund. 2017. Worlds Apart Trading Together: The Organisation of Long-Distance Trade between Rome and India in Antiquity. Oxford: Archaeopress Publishing Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Gombrich, Ernst H. 1979. The Sense of Order. A Study in the Psychology of Decorative Art. New York: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hairman, Ann. 2012. Sleep well! Sleeping Practices in Buddhist Disciplinary Rules. Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 65: 427–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertel, Johannes. 1911. The Story of Merchant Campaka. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft 65: 1–51, 425–70. [Google Scholar]

- Iversen, Margaret. 1993. Alois Riegel: History and Theory. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Knox, Robert. 1992. Amaravati, Buddhist Sculpture from the Great Stūpa. London: British Museum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, Margarete. 1965. Die Rückenfigur im Bild. Von der Antike bis zu Giotto. Recklinghausen: Aurel Bongers, Münstersche Studien zur Kunstgeschichte 2. [Google Scholar]

- LIMC. 1981–2009. LIMC Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae 1981–2009. Zurich and Munich: Artemis-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Longhurst, Albert Henry. 1938. The Buddhist Antiquities of Nāgārjunikoṇḍa, Madras Presidency. Memoirs of the Archaeological Survey of India 54. Delhi: Manager of Publications. [Google Scholar]

- McNally, Sheila. 1985. Ariadne and Others: Images of Sleep in Greek and Early Roman Art. Classical Antiquity 4: 152–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parimoo, Ratan. 2002. Narrative Structure and the Significance of the Snake Jatakas in Buddhist Art. In Essence of Art and Culture: In Memory of Prof. Kalyan Kumar Ganguly. Edited by S. S. Biswas, Amita Ray, Deepak R. Das and Samir K. Mukhrejee. Delhi: Agam Kala Prakashan, pp. 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Poonacha. 2011. Excavations at Kanaganahalli (Sannati, Dist. Gulbarga, Karnataka). Memoirs of the Archaeological Survey of India 106. Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India. [Google Scholar]

- Quagliotti, Anna Maria. 2009. Māyā’s Dream from India to Southeast Asia. In The Indian Night: Sleep and Dreams in Indian Culture. Edited by Claudine Bautze-Picron. New Delhi: Rupa, pp. 351–417. [Google Scholar]

- Rama, K. 1995. Buddhist Art of Nāgārjunakoṇḍa. Delhi: Delhi Sundeep Prakashan. [Google Scholar]

- Riegl, Alois. 1893. Stilfragen: Grundlegungen zu einer Geschichte der Ornamentik. Berlin: Siemens. [Google Scholar]

- Rockhill, William W. 1897. Tibetan Buddhist Birth-Stories; Extracts and Translations from Kanjur. Journal of the American Oriental Society 1897: 2–14. [Google Scholar]

- Schick, Josef. 1912. Das Glückskind mit dem Todesbrief. Orientalische Fassungen. Corpus Hamleticum: Hamlet in Sage und Dichtung, Kunst und Musik. Berlin: Emil Felber. [Google Scholar]

- Schiefner, Anton von. 1906. Tibetan Tales Derived from Indian Sources. Translated by William Ralston Sheddon-Ralston. Translated from the Tibetan of the Kah-Gyur. London: Trübner. [Google Scholar]

- Schlingloff, Dieter. 1987. Studies in the Ajanta Paintings, Identifications and Interpretations. New Delhi: Munshiram. [Google Scholar]

- Schlingloff, Dieter. 2000. Ajanta—Handbuch der Malereien/Handbook of the Paintings 1. Erzählende Wandmalereien/Narrative Wall-Paintings. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Schlingloff, Dieter. 2013. Ajanta—Handbook of the Paintings 1. Narrative Wall-Paintings; New Delhi: IGNCA, pp. 1–3.

- Sivaramamurti, Calambur. 1942. Amaravati Sculptures in the Madras Government Museum = Bulletin of the Madras Government Museum; N.S. 4; Madras: Government Museum.

- Stern, Philippe, and Mireille Bénisti. 1961. Évolution du style indien d’Amarāvatī [Evolution of the Indian Style of Amarāvatī]. Publications du Musée Guimet, Recherches et documents d’art et d’archéologie, 7. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, Elizabeth R. 1994. The Buddhist Art of Nāgārjunakoṇḍa. Buddhist Tradition Series 25. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, Elizabeth R. 2005. Spatial Conventions in the Art of Andhra Pradesh: Classical Influence? In Buddhism: Art, Architecture, Literature & Philosophy. Edited by G. Kamalakar and M. Veerender. Delhi: Sharada Publishing House, vol. 1, pp. 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, Elizabeth R. 2008a. The Adaptation of Western Motifs in the Art of Gandhara. In The Buddhist Heritage of Pakistan: Legends, Monasteries, and Paradise, Exhibition Catalogue. Edited by Dorothee Drachenfels and Christian Luczanits. Zurich and Mainz: Philipp von Zabern, pp. 80–85. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, Elizabeth R. 2008b. The Sculpture of Andhra Pradesh and Roman Imperial Imagery. In Krishnabhinandana: Archaeoogical, Historical and Cultural Studies, Festschrift to Dr. V. V. Krishna Sastry. Edited by P. Chenna Reddy. New Delhi: Research India Press, pp. 100–6. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, Elizabeth R. 2016. Reflections on Roman Art in Southern India. In Amaravati: The Art of an Early Buddhist Monument in Context. Edited by Akira Shimada Akira and Michael Willis. London: The British Museum, pp. 59–69. [Google Scholar]

- Stoye, Martina. 2006. ‘Māyā Anadyomene’—Die schöne Śākya-Fürstin beim Bade. Zum Import einer etablierten Bildformel in ein erzählendes Relief aus Amarāvatī. In Vanamālā, Festschrift Adalbert Gail. Edited by Klaus Bruhn and Gerd J. R. Mevissen. Berlin: Weidler, pp. 224–34. [Google Scholar]

- Stoye, Martina. 2008. Garuḍa and Ganymed. In The Buddhist Heritage of Pakistan: Legends, Monastries, and Paradise. Edited by Dorothee Drachenfels and Christian Luczanits. Zurich and Mainz: Philipp von Zabern, pp. 268–69. [Google Scholar]

- Tournier, Vincent. Forthcoming. Buddhist Nikāyas in Āndhra and Beyond: A Survey of the Epigraphic Evidence. In From Vijayapurī to Śrīkṣetra? The Beginnings of Buddhist Exchange across the Bay of Bengal. Edited by Arlo Griffiths, Alexey Kirichenko, Akira Shimada and Vincent Tournier. Paris: École Française d’Extrême-Orient.

- Vogel, Jean Philippe. 1937. The Man in the Well and some Other Subjects Illustrated at Nāgārjunikoṇḍa. Revue des Arts Asiatiques 11: 109–21. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, Albrecht. 1870. Über eine Episode im Jaimini-Bhārata (entsprechend einer Sage von Kaiser Heinrich III. und dem “Gang nach dem Eisenhammer”). In Monatsberichte der Königlich Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin. Berlin: Buchdruckerei der K. Akademie der Wissenschaften, pp. 10–48, 377–87. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, Albrecht. 1883. Über die Geschichte vom Kaufmann Campaka. Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin, 567–605, 885–95. [Google Scholar]

- Woolner, Alfred Cooper, and Lakshman Sarup. 1930–1931. Thirteen Trivandrum Plays Attributed to Bhāsa. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Zin, Monika. 2011. The Parable of "The Man in the Well". Its Travels and its Pictorial Traditions from Amaravati to Today. In Art, Myths and Visual Culture of South Asia. Edited by Piotr Balcerowicz and Jerzy Malinowski. Delhi: Manohar, pp. 33–93. [Google Scholar]

- Zin, Monika. 2012. When stones are all that survived. The case of Andhra Buddhism. Rocznik Orientalistyczny 65: 236–53. [Google Scholar]

- Zin, Monika. 2015. Nur Gandhara? Zu Motiven der klassischen Antike in Andhra (incl. Kanaganahalli). Tribus, Jahrbuch des Linden-Museums, Stuttgart 64: 178–205. [Google Scholar]

- Zin, Monika. 2016. Buddhist Narratives and Amaravati. In Amaravati: The Art of an Early Buddhist Monument in Context. Edited by Akira Shimada and Michael Willis. London: The British Museum, pp. 46–58. [Google Scholar]

- Zin, Monika. 2018a. Gandhara & Andhra: Varying Traditions of Narrative Representations (Some observations on the arrangement of scenes citing the example of the Bodhisatva crossing the river Nairañjanā). Indo-Asiatische Zeitschrift 22: 6–17. [Google Scholar]

- Zin, Monika. 2018b. The Kanaganahalli Stūpa: An Analysis of the 60 Massive Slabs Covering the Dome. New Delhi: Aryan Books International. [Google Scholar]

- Zin, Monika. Forthcoming. Fragments of a Divided Whole—On the Exhibition of Several Narrative Reliefs from the Amaravati School of Sculptures. New Perspectives in Indian Art & Visual Culture. A Felicitation Volume in Honour of Prof. Ratan Parimoo, Edited by Gauri Parimoo Krishnan and Raghavendra H. Kulkarni.

| 1 | Cf. (Zin 2018a) for comparison of representations of this episode in Gandhara and Andhra. |

| 2 | For an overview of the research see, e.g., (Begley and De Puma 1991); (Cimino 1994) and from the newest research (Evers 2017). |

| 3 | See, e.g., studies by (Stone 2005, 2008b, 2016). |

| 4 | Cf. (Schlingloff 2000, 2013), no. 64(2) for literary sources and list of the pictorial representations in South and Central Asia. |

| 5 | Buddhist literature calls the position on the left body side “position of sensous people” (kāmabhogiseyyā). Proper is the “lion position” (sihaseyyā), which is also the position of the Buddha lying down, see (Quagliotti 2009, pp. 373–76) with references. Cf. (Hairman 2012) for the corresponding vinaya precepts. |

| 6 | Cf. (LIMC 1981–2009, vol. 3.1, 1071); illus. vol. 3.2, pp. 730–35. |

| 7 | illus., e.g., in (Knox 1992, p. 121, no. 61). |

| 8 | Kanaganahalli, in situ, ASI no. 01; illus. (Aramaki et al. 2011, 63; Poonacha 2011, pl. 81; Zin 2018b, no. 1(16), pl. 9 (drawing)), for the photograph see also (Zin 2016, fig. 4.2). |

| 9 | Cf. LIMC, vol. 1.1, 54, 76–77; illus. vol. 1.2, pp. 41–42, 53, 66–68. |

| 10 | Illus. (Sivaramamurti 1942, pl. 24.3; Stoye 2006). |

| 11 | Kanaganahalli, in situ, ASI no. 56, illus. (Aramaki et al. 2011, 89; Poonacha 2011, pl. 79; Zin 2018b, no. 1(1), pl. 1 (drawing)). |

| 12 | Chennai Government Museum, no. 53, unpublished, description in (Sivaramamurti 1942, p. 246). |

| 13 | Chennai Government Museum, no. 54, illus. (Burgess 1887, pl. 27.3; Sivaramamurti 1942, pl. 49.2). |

| 14 | Chennai Government Museum, no. 75, illus. (Burgess 1887, pl. 27.2; Bachhofer 1929, pl. 122.2; Sivaramamurti 1942, pl. 51.1). |

| 15 | Chennai Government Museum, no. 124, illus. (Burgess 1887, pl. 27.1; Sivaramamurti 1942, pl. 48.2; Stern and Bénisti 1961, pl. 24a). |

| 16 | New reading of the inscriptions put together, explanation, commentary and references to previous research in the online corpus of the Early Inscriptions of Āndhradeśa, EIAD no. 302. I would like to express my greatest gratitude to Prof. Arlo Griffiths and Prof. Vincent Tournier from the EIAD project for their help and ongoing cooperation. |

| 17 | Bodhisattvāvadānakalpalatā 66, ed. vol. 2, 421–427; transl. (Asplund 2013, pp. 187–231); cf. ibid. for the detailed analysis of the narratives of Kavikumāra; the story appears among others in the Kalpadrumāvadānamālā 26 (synoptic ed. of the manuscripts and Bodhisattvāvadānakalpalatā in Asplund, 104–149); Mūlasarvāsivādavinaya preserved in Tibetan ed. (Peking edition) vol. 42, 114,3,4; ed. in Asplund, 31–44, transl. (Rockhill 1897); transl. (Schiefner 1906, pp. 273–78) (“The fulfilled prophesy”); transl. Asplund, 45–54; Chinese: Taisho no. 1450, ed. vol. 24, 195b22–197a6, French transl. in (Chavannes 1910–1934, vol. 2, no. 385, 403–411); the manuscript fragments of a text in Sanskrit have been found; they can be dated to the 6th century (cf. Asplund, 6). |

| 18 | Jātaka, no. 472, ed. vol. 4: 187–196; transl. 116–121. |

| 19 | Jātaka, no. 26, ed. vol. 1: 185–188; transl. 67–69. |

| 20 | illus. (Stone 1994, fig. 224 (upper register); Rama 1995, pl. 7 (upper register)); the relief is explained in the exposition as “Siddhartha Sees a Corps”. |

| 21 | identif.: (Longhurst 1938, 51–53; illus. ibid., pl. 45b; Rama 1995, pl. 41). |

| 22 | The youth standing up on his own to the stampeding elephant brings to mind an episode from the theatre play Avimāraka; in this play, the prince disguised as an outcast rescues the princess from the attack of a furious elephant, cf. (Woolner and Sarup 1930–1931, II, 66–67). |

| 23 | As recently shown by Vincent Tournier (forthcoming) the name of this school is evidenced also at Kanaganahalli; it appears that the Mahāvinaśailas were especially interested in pictorial representations of the narratives. |

| 24 | The narratives illustrated in Andhra correspond with the “northern” textual tradition rather than with the Pali, and contain episodes such as the presentation of the new-born Siddhārtha to the yakṣa Śākyavardhana familiar from the Mūlasarvāstivada tradition and represented in Central Asia; characteristic are four (not the usual three) daughters of Māra, a very rare feature known today only from a Chinese translation of an old Lalitavistara, Taisho no. 186, cf. (Zin 2018b, pp. 30, 76). |

| 25 | Cf. LIMC, vol. 6.1, 187–188; illus. vol. 6.2, 88–89. |

| 26 | illus. (Burgess 1887, pl. 49.1 (drawing); Sivaramamurti 1942, pl. 51.2). |

| 27 | Comprehensive references to the mentioned fairy-tale motifs in lemmae “Uriasbrief”, “Schicksalskind”, and “Gang zum Eisenhammer” by Christine Shojaei Kawan in the Enzyklopädie des Märchens (1977–2015), vol. 5, pp. 662–71; vol. 11, pp. 1404–6; vol. 13, pp. 1262–67, respectively. |

| 28 | Liu du ji jing, Taisho no. 152, no. 45, ed. vol. 3: 25c8–26c5; French translation in (Chavannes 1910–1934, vol. 1, pp. 165–73). |

| 29 | Dhammapadaṭṭakathā II.1.2, ed. 174–187; transl. vol. 1, pp. 256–66. |

| 30 | identif.: (Vogel 1937; illus. ibid. pl. 34a; Longhurst 1938, pl. 31b; Stone 1994, pl. 64; cf. Zin 2011). |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).