Meeting the Spiritual Care Needs of Emerging Adults with Cancer

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Data and Methods

2.1. Recruitment of the Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Analysis of the Data

2.4. Ethics, Reflectivity, and Validity

2.5. Theoretical Framework: A Broad Concept of Spirituality

3. Results

3.1. Existential Concerns Raised by Cancer

3.1.1. Challenged Self and Body Image

In Anna’s narrative she leaves a few words out of the description but leads the interviewer to understand that she had been drinking and kissing a stranger. Anna had been reading about possible biological causes of her cancer and found a study showing correlation between mononucleosis and her cancer type. Therefore, she found that her illness was an outcome of her behavior. Anna explains that she does not think actively about the relationship of her actions and cancer. However, it can be interpreted that her expression still includes personal guilt and a sense of shame reviles in her words “haven’t even told mom”. Like Anna, some participants were looking for a reason for cancer in their own actions and felt themselves responsible; a few participants found that their actions led to God’s punishment, as it is shown in Section 3.3.I haven’t even told mom about this… I’d just turned 18 and me and my friends had these nights in bars. So I’m guessing that from one of these nights I caught mononucleosis [after kissing a stranger], kissing disease… so one of these drunken nights led me to have cancer.

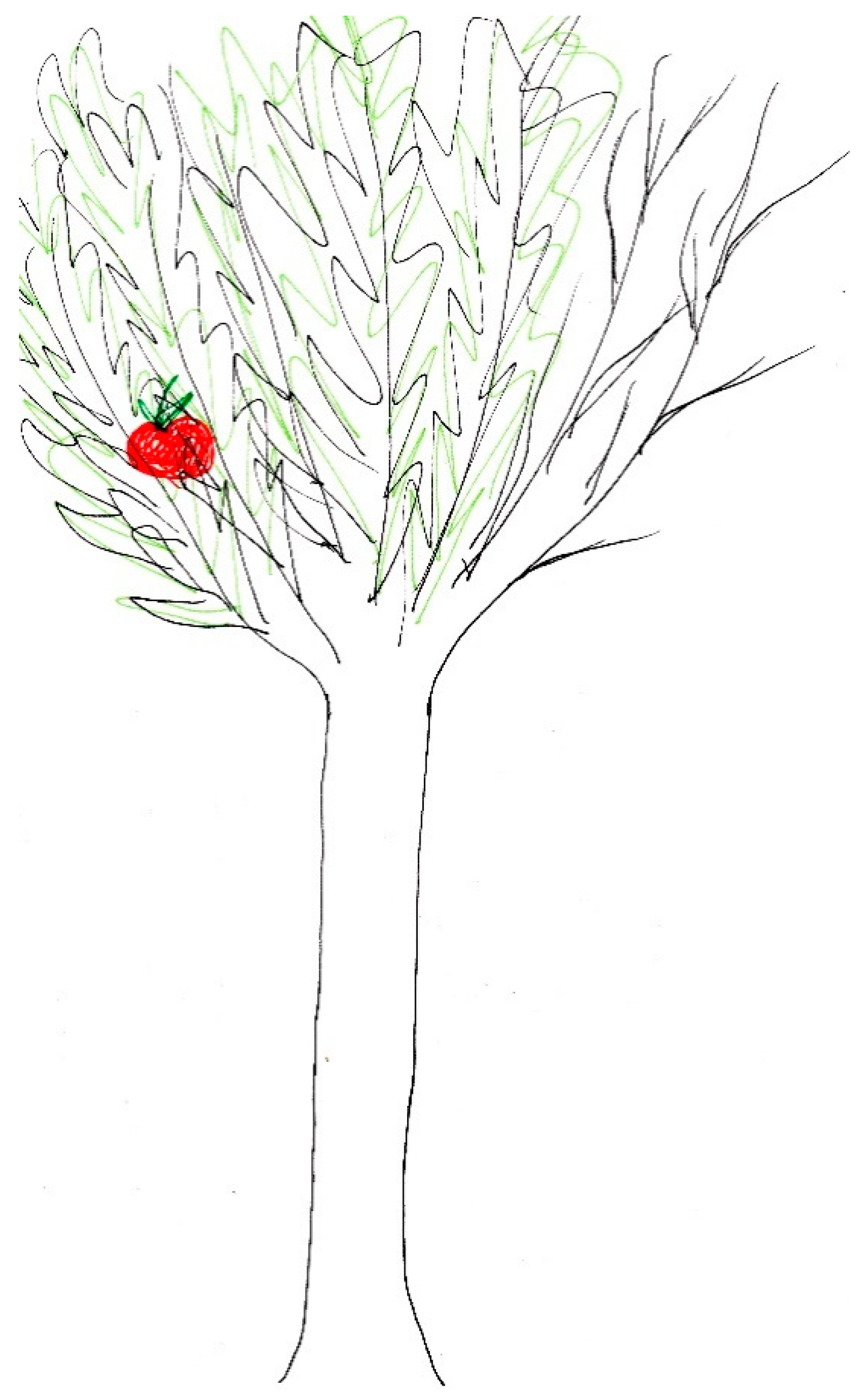

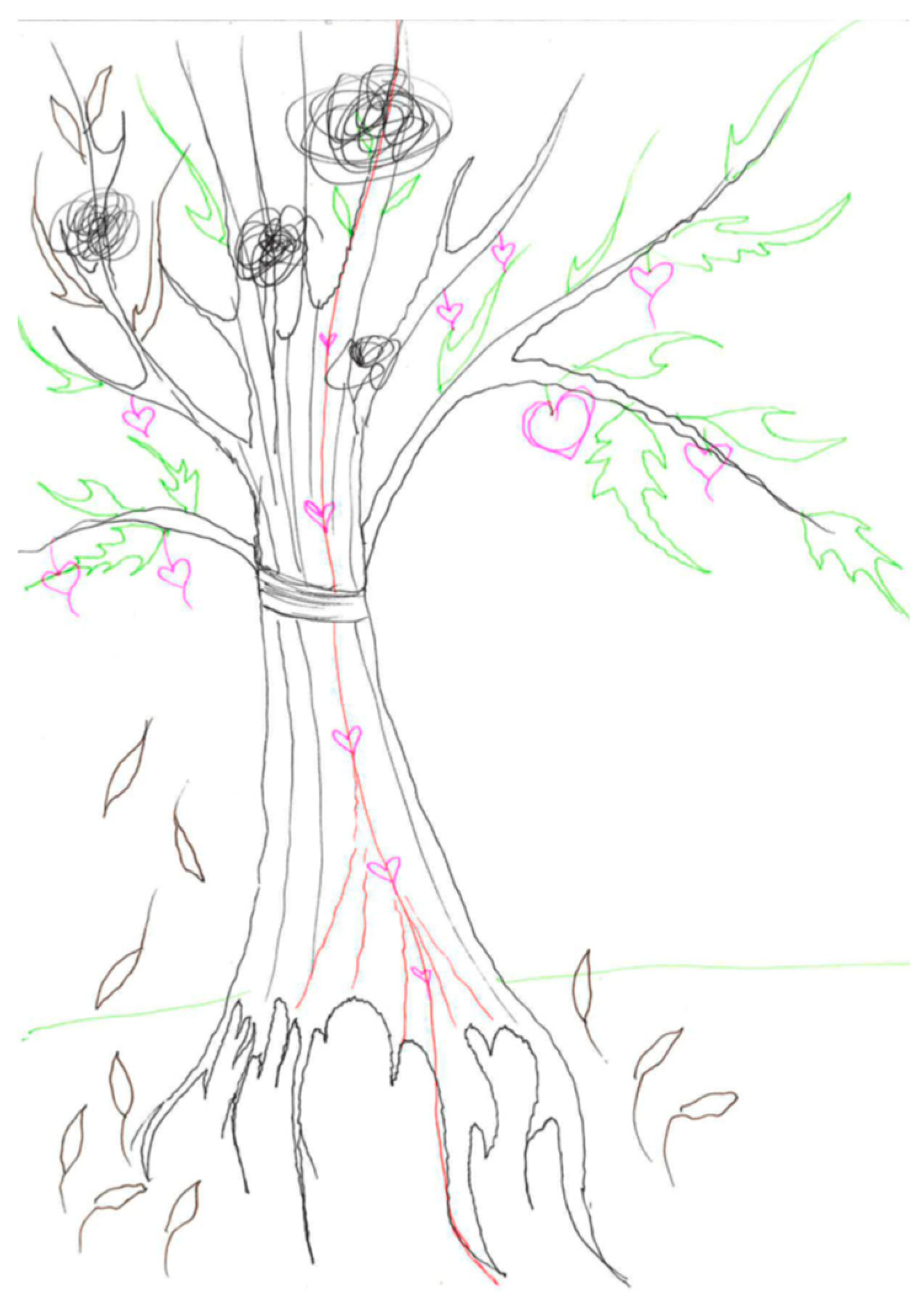

The time with cancer was somehow rough. Still, it [cancer] doesn’t fully cover the tree. It is there but it doesn’t master the tree. And there is a fruit, an apple that shows that something new is mellowing there and new life. It [cancer] doesn’t master [the tree], it is with it, but it doesn’t interfere with the growth otherwise.

3.1.2. Relationships as (Dis)Encouragement

Olivia’s quotation shows how strongly cancer impacted on the couple; it also illustrates how people go through cancer thoughts at different paces and the spouse could not handle Olivia’s fear of death. During her treatment, her spouse left for a couple of weeks in order to clear his head. Meanwhile, Olivia was confronted with the thought of being abandoned by her spouse while being terrified of cancer. When they sought couple counseling, the counselor dismissed their issues by saying: “you are young, you’ll sort this out as [you have sorted] all other problems”. Still, for Olivia close relations, including her spouse and his mother as well as her own mother, formed the most important source of mental support.Cancer is not good for your relationship. Somehow it is really hard… my spouse has panicked. A few times he has been ready to take off… Somehow, he believes that I’ll get through this. But no one can speed up my journey.

3.1.3. Fear of Relapse and Death

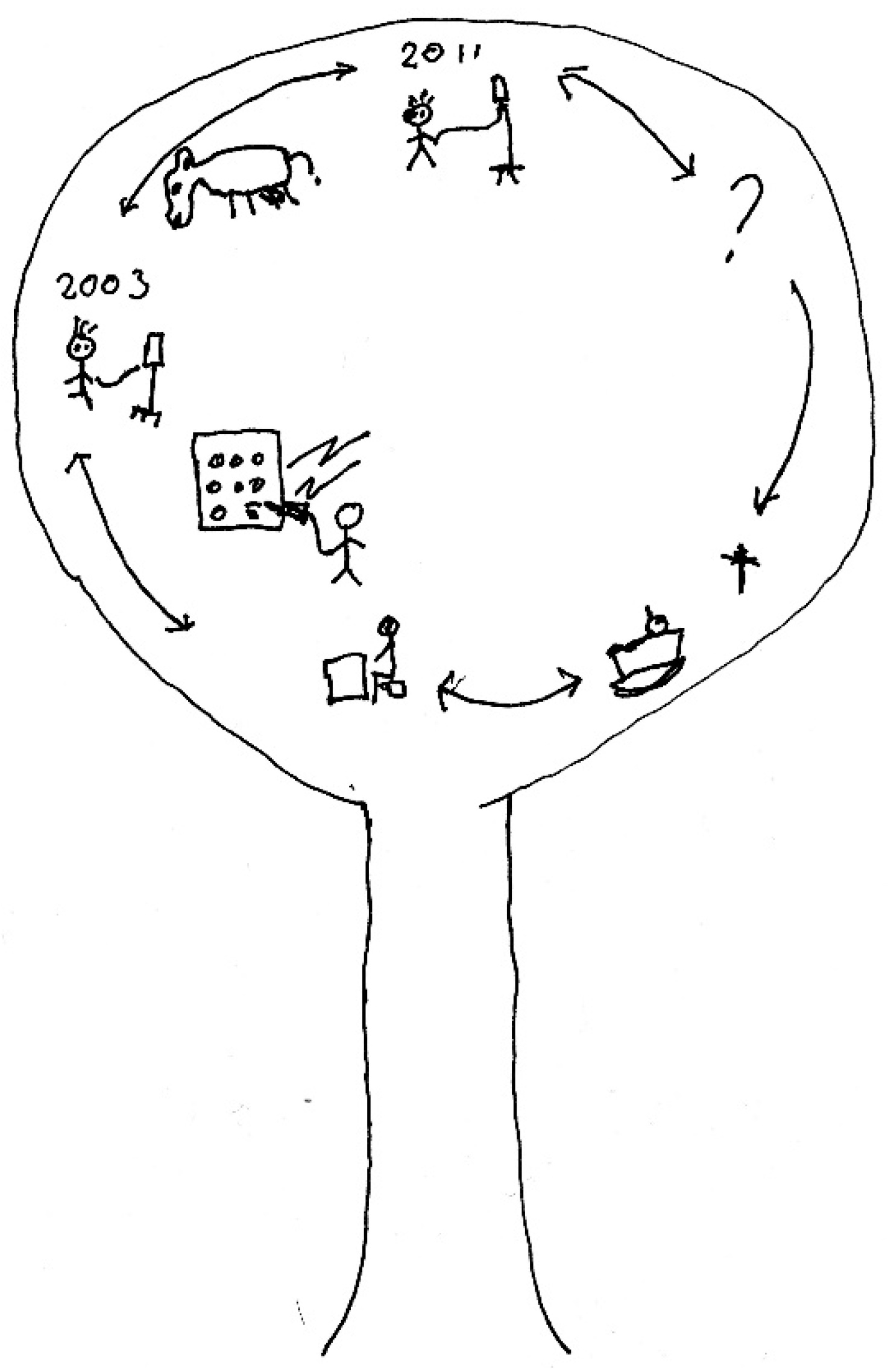

Sarah’s hesitation about the future is also made vivid in her drawing (Figure 2), in which she leaves the top of the tree undrawn. Even though Sarah found cancer to be an important factor that shaped her identity, the illness impacted strongly on her views of the future where death is somehow present. Around half of the participants found that cancer yielded this dualism about the future. The emerging adults found that they could have a happy and fulfilled life; yet, they were concerned about relapse or secondary disease, and early death because of it. Often the fear of relapse and despair peaked when heading for doctor’s appointments and remission check-ups.I am afraid to think about [the future]. So at this point, if I consider all the things my body has gone through …even if there were no relapse… In some scenarios I go earlier than in others. In some scenarios I’ll have a relapse, and in other scenarios I’ll have these unpleasant secondary diseases.

3.2. Value-Based Spirituality

In Chloe’s case, the cancer led to finding a meaningful career. The idea of providing support for others was shared by participants who found a career path related to care work. For some, self-reflection on work provided an opportunity to change the area within their own field. These shifts were made to improve their work-life balance, as Anna narrated: “I know that I’ve been living in a constant hurry... I want to give up that hurry. If I work as a teacher, I don’t have to be available all the time”. The idea of a calm pace at work was linked to participants’ wish to have more time for taking care of themselves and their relationships. More generally, cancer had clarified the value of health for the participants.The credit for finding my study field goes fully to this cancer. I would never have begun to study Occupational therapy if I hadn’t fallen ill. Having this personal experience in the background, being really functional and active in my life and then losing it. It’s like suddenly you are unable to do the stuff that is important to you. So I realized that I want to be in a job in which I can help people in the situation where their physical abilities are restricted.

3.3. Religious Coping and Appearance of Spiritual Seeking

In adolescence, I found myself strongly Christian… now for few years, before the illness, I’ve had this idea that it [faith] grows from inside an individual… this thought was not ready before the illness… but I don’t need a book or religion to define faith, it has to come from inside me… I wouldn’t say I’m particularly Christian… Somehow the illness has made me turn more to my Christianity. More or less, I’ve been praying… It feels really good to know that people have been praying [for me].

4. Discussion: Multilayered Needs for Spiritual Care Require Manifold Practices

5. Summary

6. Limitations

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arnette, Jeffrey Jensen. 2004. Emerging Adulthood. The Winding Road from the Late Teens through the Twenties. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barakat, Lamia P., Melissa A. Alderfer, and Anne E. Kazak. 2006. Posttraumatic growth in adolescent survivors of cancer and their mothers and fathers. Journal of Pediatric Psychology 31: 413–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belizzi, Keith M., Ashley Smith, Steven Schmidt, Theresa H. Keegan, Brad Zebrack, Charlie F. Lynch, Dennis Deapen, Margarett Shnorhavorian, Bradley J. Tompkins, and Michael Simon. 2012. Positive and negative psychological impact of being diagnosed with cancer as an adolescent or young adult. Cancer 118: 5155–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benaquisto, Lucia. 2008. Open coding. In The Sage Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods. Edited by Lisa M. Given. Thousand Oaks: Sage E-Books, pp. 581–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, JoAnne, Jennifer Plumb-Vilardaga, Ian Stewart, and Tobias Lundgren. 2009. The Art and Science of Valuing in Psychotherapy: Helping Clients Discover, Explore, and Commit to Valued Action Using Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. Oakland: New Harbinger Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Docherty, Sharron L., Mariam Kayle, Gary R. Maslow, and Sheila Judge Santacroce. 2015. The adolescent and young adult with cancer: A developmental life course perspective. Seminars in Oncology Nursing 31: 186–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ELCF. 2019a. Available online: https://evl.fi/tietoa-kirkosta/tilastotietoa/jasenet#2cbf3cda (accessed on 18 December 2019).

- ELCF. 2019b. Available online: https://evl.fi/plus/seurakuntaelama/kasvatus/rippikoulu/tiesitko- (accessed on 18 December 2019).

- Flyvberg, Bent. 2004. Five misunderstandings about case-study research. In Qualitative Research Practice. Edited by Clive Seale, Giampietro Gobo, Jaber F. Gubrium and David Silverman. London: Sage, pp. 390–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, Lois C., Catherine R. Barber, Jenny Chang, Yee Tham, Mamata Kalidas, Mothaffar Rimawi, Maria Dulay, and Richard Elledge. 2010. Self-blame, self-forgiveness, and spirituality in breast cancer survivors in a public sector setting. Journal of Cancer Education 25: 343–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganzevoort, Ruard. 1998a. Religious coping reconsidered part one: An integrated approach. Journal of Psychology and Theology 26: 260–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganzevoort, Ruard. 1998b. Religious coping reconsidered part two: A narrative formulation. Journal of Psychology and Theology 26: 276–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German, Mala. 2013. Developing our cultural strengths: Using the “Tree of Life” strength-based, narrative therapy intervention in schools, to enhance self- esteem, cultural understanding and to challenge racism. Educational and Child Psychology 30: 75–99. [Google Scholar]

- Grinyer, Anne. 2007. Young People Living with Cancer: Implications for Policy and Practice. Buckingham: Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grinyer, Anne. 2009. Life after Cancer in Adolescence and Young Adulthood: The Experience of Survivorship. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gunnarson, A. Birgitta, Jansson Jan-Åke, and Eklund Mona. 2006. The Tree Theme Method in psychosocial occupational therapy: A case study. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy 13: 229–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnarson, A. Birgitta, Peterson Kerstin, Leufstadius Christel, Jansson Jan-Åke, and Eklund Mona. 2010. Client perceptions of the Tree Theme Method: A structured intervention based on storytelling and creative activities. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy 17: 200–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, Steven C., Kirk D. Strosahl, and Kelly G. Wilson. 2012. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. The Process and Practice of Mindful Change, 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hook, Joshua N., Everett L. Worthington, Shawn O. Utsey, Don E. Davis, Aubrey L. Gartner, David J. Jennis, Daryl R. Can Tongeren, and Al Dueck. 2012. Does forgiveness require interpersonal interactions? Individual differences in conceptualization of forgiveness. Personality and Individual Differences 53: 687–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, Gillian. 2014. Finding a voice through “The Tree of Life”: A strength-based approach to mental health for refugee children and families in schools. Clinical Child Psychology 19: 139–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, Barbara L., Deborah L. Volker, Yolanda L. Vinajeras, Linda L. Butros, Cynthia L. Fitchpatrick, and Kelly L. Rossetto. 2010. The meaning of surviving cancer for latino adolescents and emerging young adults. Cancer Nursing 33: 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, Carmit, and Hamama Liat. 2013. Draw me everything that happened to you: Exploring children’s drawings of sexual abuse. Children and Youth Review 35: 877–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keats, Patrice A. 2009. Multiple text analysis in narrative research: Visual, written, and spoken stories of experience. Qualitative Research 9: 181–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, Erin E., Carla Parry, Michael J. Montoya, Leonard S. Sender, Rebecca A. Morris, and Hoda Anton-Culver. 2012. “You’re too young for this”: Adolescent and young adults’ perspectives on cancer survivorship. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology 30: 260–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, Nigel. 2017. Thematic analysis in organisational research. In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Business and Management Research: Methods and Challenges. Edited by Cathrine Cassell, Ann L. Cunliffe and Gina Grandy. London: SAGE, pp. 219–36. [Google Scholar]

- Klingenberg, Maria. 2014. Conformity and Contrast: Religious Affiliation in a Finland-Swede Youth Context. Doctoral dissertation, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland. [Google Scholar]

- Kwak, Minyoung, Brad J. Zebrack, Katheel A. Meeske, Leanna Embry, Christine Aguilar, Rebecca Block, Brandon Hayes-Lattin, Yun Li, Melissa Butler, and Steven Cole. 2013. Trajectories of psychological distress in adolescent and young adult patients with cancer: A 1-year longitudinal study. Journal of Clinical Oncology 31: 2160–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyngäs, Helvi, Toini Jämsä, Raija Mikkonen, Eeva-Maija Nousiainen, Mervi Rytilahti, Pirkko Seppänen, and Ritva Vaittovaara. 2000. Terveys ei ole enää itsestään selvyys. Se on elämän suuri lahja. Tutkimus syöpää Sairastavien Nuoren Selviytymisestä Sairauden Kanssa. [Health Is No Longer Taken for Granted. It Is a Great Gift of Life. Cancer Coping of Young Adults]. Oulu: Pohjois-Pohjanmaan Sairaanhoitopiirin Julkaisuja. [Google Scholar]

- Kyngäs, Helvi, Raija Mikkonen, Eeva-Maija Nousiainen, Mervi Rytilahti, Pirkko Seppänen, Ritva Vaittovaara, and Toimi Jämsä. 2001. Coping with the onset of cancer: Coping strategies and resources of young people with cancer. European Journal of Cancer Care 10: 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lester, Andrew D. 1995. Hope in Pastoral Care and Counseling. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press. [Google Scholar]

- Levitt, Heidi M., Bamberg Michael, Creswell John W., Frost David M., Josselson Ruthellen, and Suárez-Orozco Carola. 2018. Journal article reporting standards for qualitative primary, qualitative meta-analytic, and mixed methods research in psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board task force report. American Psychologist 73: 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lev-Wiesel, Rachel, and Liraz Revital. 2007. Drawings vs. narratives: Drawing as a tool to encourage verbalization in children whose fathers are drug abusers. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry 12: 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieblich, Amia. 1998. The holistic-content perspective. In Narrative Research: Reading, Analysis and Interpretation. Edited by Amia Lieblich, Rivka Tuval-Mashiach and Tamar Zilber. Thousand Oaks: Sage, pp. 62–87. [Google Scholar]

- Little, Miles, and Emma-Jane Sayers. 2004. While there’s life... hope and the experience of cancer. Social Science & Medicine 59: 1329–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishler, Elliot G. 1986. Research Interviewing: Context and Narrative. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nass, Sharyl J., Lynda K. Beaupin, Wendy Demark-Wahnefried, Karen Fasciano, Patricia A. Ganz, Brandon Hayes-Lattin, Melissa M. Hudson, Brenda Nevidjon, Kevin C. Oeffinger, Ruth Rechis, and et al. 2015. Identifying and addressing the needs of adolescents and young adults with cancer: Summary of an institute of medicine workshop. Oncologist 20: 186–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolan, Steven, Philip Saltmarsh, and Carlo Leget. 2011. Spiritual care in palliative care: Working towards an EAPC task force. European Journal of Palliative Care 18: 86–89. [Google Scholar]

- Pain, Helen. 2012. A literature review to evaluate the choice and use of visual methods. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 11: 303–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmu, Harri, Salomäki Hanna, Ketola Kimmo, and Niemelä Kati. 2012. Haastettu kirkko. Suomen evankelis-luterilainen kirkko vuosina 2008–2011. [Challenged Church. The Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland in the Years 2008–2011]. Porvoo: Kirjapaja. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament, Kenneth I. 1997. The Psychology of Religion and Coping. Theory, Research, Practice. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament, Kenneth I., Kennell Joseph, Hathaway William, Grevengoed Nancy, Newman John, and Jones Wendy. 1988. Religion and the problem-solving process: Three styles of coping. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 27: 90–104. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament, Kenneth I., Bruce W. Smith, Harold G. Koenig, and Lisa Perez. 1998. Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 37: 710–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Crystal L., and Dalnim Cho. 2017. Spiritual well-being and spiritual distress predict adjustment in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology 26: 1293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Crystal L., Donald Edmondson, Amy Hale-Smith, and Thomas Blank. 2009. Religiousness/spirituality and health behaviors in younger adult cancer survivors: Does faith promote a healthier lifestyle? Journal of Behavioral Medicine 32: 582–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Crystal L., Jennifer H. Wortmann, Amy E. Hale, Dalmin Cho D., and Thomas O. Blank. 2014. Assessing quality of life in young adult cancer survivors: development of the Survivorship-Related Quality of Life scale. Quality of Life Research 23: 2213–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, Sharon Daloz. 2011. Big Questions Worthy Dreams, 2nd ed. San Francisco: Jossey Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, Pandora, Fiona E.J. McDonald, Brad Zebrack, and Sharon Medlow. 2015. Emerging issues among adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Seminars in Oncology Nursing 31: 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragsdale, Judith R., Mary Ann Hegner, Mark Mueller, and Stella Davies. 2014. Identifying religious and/or spiritual perspectives of adolescents and young adults receiving blood and marrow transplants: A prospective qualitative study. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation 20: 1242–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riessman, Cathrine K. 2008. Narrative Methods for the Human Sciences. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Romero, Catherine, Lois C. Friedman, Mamata Kalidas, Richard Elledge, Janny Chang, and Katheel R. Liscum. 2006. Self-Forgiveness, spirituality, and psychological adjustment in women with breast cancer. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 29: 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, Gillian. 2016. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to the Interpretation of Visual Materials, 4th ed. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Saarelainen, Suvi-Maria. 2015. Life tree drawings as a methodological approach in young adults’ life stories during cancer remission. Narrative Works 5: 68–91. [Google Scholar]

- Saarelainen, Suvi-Maria. 2016. Coping-related themes in cancer stories of young Finnish adults. International Journal of Practical Theology 20: 69–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarelainen, Suvi-Maria. 2017a. Meaningful Life with(out) Cancer: Coping Narratives of Emerging Finnish Adults. Doctoral dissertation, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland. [Google Scholar]

- Saarelainen, Suvi-Maria. 2017b. Emerging Finnish adults coping with cancer: Religious, spiritual, and secular meanings of the experience. Pastoral Psychology 66: 251–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarelainen, Suvi-Maria. 2018. Lack of belonging as disrupting the formation of meaning and faith: Experiences of youth at risk of becoming marginalized. Journal of Youth and Theology 17: 127–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarelainen, Suvi-Maria. 2019. Landscapes of hope and despair: Stories of the future of emerging adults in cancer remission. Journal of Pastoral Theology 29: 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarelainen, Suvi-Maria, Peltomäki Isto, and Auli Vähäkangas. 2019. Healthcare chaplaincy in Finland. Tidsskrift for Praktisk Teologi 2: 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Sansom-Daly, Ursula M., and Claire E. Wakefield. 2013. Distress and adjustment among adolescents and young adults with cancer: An empirical and conceptual review. Transnational Pediatrics 2: 167–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonninen, Susanna, ed. 2012. Nuoren Syöpäpotilaan Selviytymisopas. [Survival Guide for Young Patient]. Redfina: Suomen Syöpäpotilaat ry. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, David M., Karen H. Albritton, and Andrea Ferrari. 2010. Adolescent and young adult oncology: An emerging field. Journal of Clinical Oncology 28: 4781–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, Dorthe K., and Anders Bonde Jensen. 2007. Memories and narratives about breast cancer: Exploring associations between turning points, distress and meaning. Narrative Inquiry 17: 349–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Allison, Sainsbury Peter, and Craig Jonathan. 2007. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 19: 349–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toussaint, Loren, Michael Barry, Lynn Bornfriend, and Maurie Markman. 2014. Restore: The journey toward self-forgiveness: A randomized trial of patient education on self-forgiveness in cancer patients and caregivers. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy 20: 54–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toussaint, Loren, Michael Barry, Drew Angus, Lynn Bornfriend, and Maurie Markman. 2017. Self-Forgiveness is associated with reduced psychological distress in cancer patients and unmatched caregivers: Hope and self-blame as mediating mechanisms. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology 35: 544–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vassal, Gilles, Edel Fitzgerald, Martin Schrappe, Frédéric Arnold, Jerzy Kowalczyk, David Walker, Lars Hjorth, Riccardo Riccardi, Anita Kienesberger, Kathy-Pitchard Jones, and et al. 2014. Challenges for children and adolescents with cancer in Europe: The SIOP-Europe Agenda. Pediatric Blood Cancer 61: 1551–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vipunen. 2019. Available online: https://vipunen.fi/fi-fi/perus/Sivut/Kieli--ja-muut-ainevalinnat.aspx (accessed on 18 December 2019).

- Walker, Amy J., and Frances Marcus Lewis. 2016. Adolescent and young adult cancer survivorship: A systematic review of end-of-treatment and early posttreatment. Nursing and Palliative Care 1: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, Echo L., Erin E. Kent, Kelly M. Trevino, Helen M. Parsons, Brad J. Zebrack, and Anne C. Kirchhoff. 2016. Social well-being among adolescents and young adults with cancer: A systematic review. Cancer 122: 1029–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, Sandra. 2008. Visual images in research. In Handbook of the Arts on Qualitative Research: Perspectives, Methodologies, Examples, and Issues. Edited by J. Gary Knowles and Ardra L. Cole. Thousand Oaks: Sage, pp. 42–55. [Google Scholar]

- Worthington, Everett L. 2014. Forgiveness and Reconciliation: Theory and Application. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Yanez, Bettina, Donald Edmondson, Annette L. Stanton, Crystal L. Park, Lorna Kwan, Patricia A. Ganz, and Thomas O. Blank. 2009. Facets of spirituality as predictors of adjustment to cancer: Relative contributions of having faith and finding meaning. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 77: 730–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Jaehee, Brad Zebrack, Min Ah Kim, and Melissa Cousino. 2015. Posttraumatic growth outcomes and their correlates among young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Journal of Pediatric Psychology 40: 981–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebrack, Brad, Rebecca Block, Brandon Hayes-Lattin, Leanne Embry, Christine Aguilar, Kathleen A. Meeske, Yun Li, Melissa Butler, and Steven Cole. 2014. Psychosocial service use and unmet need among recently diagnosed adolescent and young adult cancer Patients. Cancer 119: 201–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | See more about the medical descriptions of cancer types and stages: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/all-cancer-types.html#alpha-H. |

| Name * | Cancer | Time since Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Anna | Hodgkin’s lymphoma, first diagnosis as stage 2A was changed to stage 3 after six months of chemotherapy; because of the changes in spread the treatment was continued for two months. | 5 years |

| Ava | Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, more local but made breathing difficult and caused other symptoms. | 2 years |

| Beth | Hodgkin’s lymphoma, stage 4A. Relapse after a couple of years in remission. | 2 years |

| Cain | Testicular cancer, spread to lymph nodes. | 5 years |

| Chloe | Hodgkin’s lymphoma, stage 4B, relapsed during treatment. | 3 years |

| Emily | Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, no descriptions of spread. Six months of treatment and no external signs that could refer to more local cancer. | 5 years |

| Emma | Hodgkin’s lymphoma, stage 4B. | 1 year |

| Gina | Lymphoma, with large spread and multiple tumors likely to mean stage 4B. | 3 years |

| John | Hodgkin’s lymphoma, stage 4B. Relapse after seven years in remission. | Right after the treatment |

| Macy | Lymphoma, diagnosis changed during the treatment to spreading stage 4. | 7 months |

| Mark | Hodgkin’s lymphoma, no descriptions of spread. Six months of treatment, this could refer to more local cancer. | 7 months |

| Olivia | Hodgkin’s lymphoma, stage 2A. | During treatment and 4 months after |

| Sarah | Hodgkin’s lymphoma, no notification of exact spread. Symptoms: tumor near the collar bone and tiredness. | 5 years |

| Sophia | Osteosarcoma (knee). Localized cancer; an amputation was not needed. | 5 years |

| Thea | Sarcoma (back), stage 4B. | 4 years |

| Tom | Osteosarcoma (knee), chemotherapy and amputation. Refers to spread to some extent. | 2 years |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saarelainen, S.-M. Meeting the Spiritual Care Needs of Emerging Adults with Cancer. Religions 2020, 11, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11010016

Saarelainen S-M. Meeting the Spiritual Care Needs of Emerging Adults with Cancer. Religions. 2020; 11(1):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11010016

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaarelainen, Suvi-Maria. 2020. "Meeting the Spiritual Care Needs of Emerging Adults with Cancer" Religions 11, no. 1: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11010016

APA StyleSaarelainen, S.-M. (2020). Meeting the Spiritual Care Needs of Emerging Adults with Cancer. Religions, 11(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11010016