1. Introduction

Spirituality is important for people during the experience of cancer diagnosis and treatment. In this study, the term spirituality refers to a person’s search for and experience of connectedness with whatever they consider the essence of their lives (

de Jager Meezenbroek et al. 2012). Within this definition, religion and spirituality are considered to be independent but overlapping constructs. They would overlap when connectedness with the essence of life is searched for and experienced within a religious tradition. Spirituality expresses itself in constellations of beliefs, attitudes, activities, and experiences (

La Cour et al. 2012;

Weathers et al. 2016). The objective of the present study is to examine how various types of spirituality influence the emotional adjustment to cancer.

Park (

2010) has offered a model that to date forms the most comprehensive description of the process of meaning-making that takes place when people face a negative life event. Based on existing literature, she suggests that negative life events trigger a discrepancy between previously held beliefs, goals and experiences of meaningfulness (global meaning system) and the meaning attributed to the event (situational meaning). Processes of meaning making are then activated to reduce this discrepancy. A meaning system is defined as a worldview, that is, a cognitive unity of beliefs, attitudes, values, and norms that each individual develops across his or her personal history, and through which the person identifies himself, ascribes meaning to his life, and attains a sense of certainty (

Van Uden 1985, p. 184).

Park (

2010) describes different ways in which the process of meaning-making can take place. She distinguishes between automatic and deliberate meaning-making, between assimilation (situational meaning is adjusted to and incorporated in global meaning) and accommodation (global meaning is adjusted to the situational meaning), between searching for comprehensibility (understanding what has happened) and for significance (understanding why it has happened), and between cognitive and emotional processing. Park notes, however, that more information is needed on these processes. Particularly, on which types of meaning systems may facilitate assimilation—which seems to be more common than accommodation—and may, thus, be less vulnerable to discrepancies. The role of spiritual and religious beliefs, practices and experiences in this regard is of special interest in this study.

Several studies have provided clues toward answering these questions. For example,

Vonarx and Hyppolite (

2013) describe how 10 Canadian cancer patients felt that the diagnosis challenged their beliefs about the length of their lives and the strength of their bodies. The patients who then found meaning in the disease, attributed it to their lifestyle. They gained a sense of control from this belief. Various spiritual practices, such as prayer, meditation, visualizations, and complementary or alternative medicine were used by these patients to persuade both supernatural and biological forces to heal them.

Woods and Ironson (

1999) found among American patients with cancer, HIV, or cardiac disease that beliefs in personal control over illness were more often present among those who identified as spiritual than those who identified as religious. Instead, those who identified as religious more often reported believing that both their recovery and their physicians were guided by a divine power. On the other hand, the study by

Vonarx and Hyppolite (

2013) suggests that beliefs in personal and supernatural locus of control go together within a person, and that the emphasis on one or the other is influenced by the circumstances of the illness. This is also evident in a study among 10 American women diagnosed with breast cancer (

Halstead and Hull 2001). At first, the women sought to find control over their health themselves. However, when realizing that their level of control was only limited, they turned to God for support, even though for some women this brought along conflicting feelings about the love and protectiveness of God for them. Prayer, reflection and study were important means for these women to uncover meaning. Gradually, as the women came to terms with the uncertainty and the changed identity that resulted from the experience with cancer, they began to also see benefits from the experience, reflecting a changed meaning of the event. A similar process seems to have taken place among the 55 Danish cancer patients in a study by

Hvidt (

2017). However, these patients did not express a relationship with God as important in their process, but rather emphasized the importance of connecting with other people who had experienced serious life events as a way to find recognition and to reconnect to ‘ordinary’ life. The 16 Finnish young adults with cancer in the study by

Saarelainen (

2017) also expressed the importance of fellow patients in finding meaning, but also the connectedness with family and friends, and with God. About half of these patients expressed a similar ambivalence in their relationship with God as the women in the study by

Halstead and Hull (

2001). Across these studies, time since diagnosis, stage of disease, personality characteristics, and other life events during the cancer experience seemed to influence how the adjustment process transpires.

The exemplary studies above illustrate the ways in which different (spiritual) beliefs and attitudes, particularly regarding control, can relate to the process of meaning-making as a way to cope with cancer. However, these studies have rarely explicitly examined differences between types of meaning systems. In addition, most of the studies have taken place in the United States, where in 2014 36% of the population indicated to visit religious services at least once a week (

Pew Research Center 2015), which suggests that for a substantial proportion of the population a religious (often Christian) meaning system is central. However, in the Netherlands only 12% of the population reported regularly visiting a religious service in 2015 (

Bernts and Berghuijs 2016), suggesting possibly more variety in spiritual meaning systems, or a higher presence of more secular meaning systems than in the USA.

This role of culture is evidenced in studies by Ahmadi and colleagues.

Ahmadi (

2006) has suggested that in secularized countries, such as Sweden, cancer patients do not invoke a relationship with God when coping with their illness, but focus on their relationship with nature, themselves, or the universe instead. This was confirmed in a comparative study of cancer patients in Sweden and South Korea (

Ahmadi et al. 2017). However, the Swedish patients were more inclined to express their relationship with nature and with themselves as ‘spiritual’ or as sanctified, whereas the Korean respondents referred to both in a more instrumental way as a source of healing. In addition, the Swedish patients used solitude and prayer as ways to connect to themselves, whereas the Korean patients felt lonely in solitude and used prayer to connect to a transcendent power (for example, Buddha, Jesus, ancestors). Among Turkish cancer patients, living in a more religious country however, religious meaning-making was much more prevalent (

Ahmadi et al. 2019).

In a previous paper, we described how four types of meaning system were uncovered through thematic analysis of interviews with 20 Dutch cancer patients who in the past year had been treated for cancer with curative intent (

Uwland-Sikkema et al. 2018). During analysis, the use of symbolic language (mostly the use of metaphors) and the ‘transcendent’ nature of described beliefs, experiences and practices emerged as differentiating factors between the four types of meaning systems. In these meaning systems, spirituality differed both in centrality and in content. In the first type, named

Omnipresent spirituality (n = 6), spiritual beliefs and experiences were very central. These revolved around an attitude of staying connected to the Transcendent and the belief that events in life brought lessons that would bring them closer to reaching their full potential. In the second type, named

Accompanying spirituality (n = 6), spiritual beliefs and experiences were only present in the background. Instead, beliefs about the self as optimistic and energetic were central in this meaning system. In the third type, named

Enclosed spirituality (n = 4), beliefs about personal control in life were central to the meaning system, which were supported by beliefs and experiences of immanent transcendence. Although this immanent transcendence was quite central in the meaning system of these participants, it was difficult to observe due to the secular language in which it was communicated. In the fourth meaning system, named

Absent spirituality (n = 4), spiritual beliefs and experiences were not integrated into the meaning system as a whole. Instead, an attitude of focusing on daily enjoyments was central. The classification of the individuals in the meaning systems did not show overlap with classifications based on (1) religious affiliations or life philosophy, (2) self-reported level of spirituality and religiosity, (3) level of spiritual involvement assessed with the Spiritual Attitude and Involvement List (

de Jager Meezenbroek et al. 2012), and (4) evaluations of the person’s spirituality by raters based on the interview transcripts.

The present study returns to these interviews and types, to examine three questions: 1. What roles does the meaning system play in adjustment to cancer? 2. How do these roles influence outcomes of adjustment? 3. Are there differences in these processes between the four previously defined meaning systems?

2. Materials and Methods

Here the study procedures are briefly described. A more detailed description can be found in the previous paper (

Uwland-Sikkema et al. 2018).

2.1. Design

The present study involved a cross-sectional, retrospective, qualitative study design. This study took place as part of a longitudinal project investigating the relationship between spirituality and emotional adjustment to cancer.

2.2. Participants

During the period 2009–2010, participants were recruited for the project by medical staff from four hospitals and two radiotherapy institutions in the Netherlands. Eligible participants had been diagnosed with cancer no more than two months before, were treated with curative intent, were 18 years of age or older, were not diagnosed with brain cancer and had no known psychiatric illness.

Of the 460 participants who had completed all three quantitative assessments in the project over the course of 12 months, 313 (68%) had provided consent for an interview at the start of the project. Purposive sampling was applied to maximize the information-richness of the interviews, by selecting participants who showed characteristics that contrasted the central hypothesis of the project that spirituality was positively associated with emotional well-being and negatively with emotional distress. Thus, participants were selected who at the first assessment scored either high on the spirituality measure (the Spiritual Attitude and Involvement List;

de Jager Meezenbroek et al. 2012) but low on the well-being measure (the subscale Joy in Life of the Health and Disease Inventories;

De Bruin and Van Dijk 1996) and/or high on the distress measure (the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale;

Spinhoven et al. 1997), or who scored low on spirituality but high on well-being and/or low on distress. High or low scores were defined as scoring either in the highest or lowest sextile on the respective measure. Also selected were participants who showed a marked change in spirituality, well-being and/or distress over the 12-month period of quantitative assessment. A marked change was defined as falling within the highest of lowest sextile of the change scores. Overrepresentation of women, certain types of cancer and certain religious affiliations in comparison to the sample of the overall project was minimized during selection.

Eligible participants were telephoned by the interviewer (NU) to verify permission and schedule a date for the interview. Within the research team, the interviewer was primarily responsible for the qualitative data-collection and -analysis. During the course of the study, 25 participants were selected, of whom 20 were still willing to be interviewed. After 20 interviews, data saturation was reached and selection of new participants ceased. Sociodemographic and medical characteristics of the participants are displayed in

Table 1.

There was no prior relationship between the interviewer and the interviewees. Participants received a gift certificate of €7.50 with the first questionnaire and an additional gift certificate of €10 after participating in the interview. The full project was approved by the Ethics Review Board of the University Medical Centre Utrecht, the Netherlands. Informed consent included a statement that the data would be stored for at least 10 years.

2.3. Interview

Semi-structured interviews were conducted, in which a narrative was elicited by asking participants “Could you describe your past year to me, from the time you’ve received the diagnosis?”. In line with a narrative approach, we felt it was important to start with this broad, open question, to let the patient construct their own story. They could highlight about their journey what they felt was important, in the order in which they wanted to talk about the event. The interviewer did have a list of themes available to help her to explore more deeply the participant’s attitude in life. Based on the themes, she formulated follow-up and clarification questions when appropriate. These were about what was important in the participant’s life, how they viewed difficulties in life, and what gave them a sense of trust or confidence. The word ‘spirituality’ was not used by the interviewer unless the participants used it themselves, or until the end of the interview when the participant’s definition of spirituality was explored more explicitly. All interviews took place at the participant’s home. The interviews took on average 2 h, ranging from 1 h to 2 h 45 min. Interviews were audio-recorded and fully transcribed to enable data analysis.

2.4. Qualitative Analysis

During the analysis of the interviews, we took a holistic-content approach to the narratives of the participants (

Lieblich 1998). In a holistic content approach, the material is read several times until patterns emerge, sometimes with a special focus. The emergent themes are then followed throughout the narrative, to understand their development and significance. We read the narratives focusing on the question: "What role does the meaning system of this person play in this story about cancer?”.

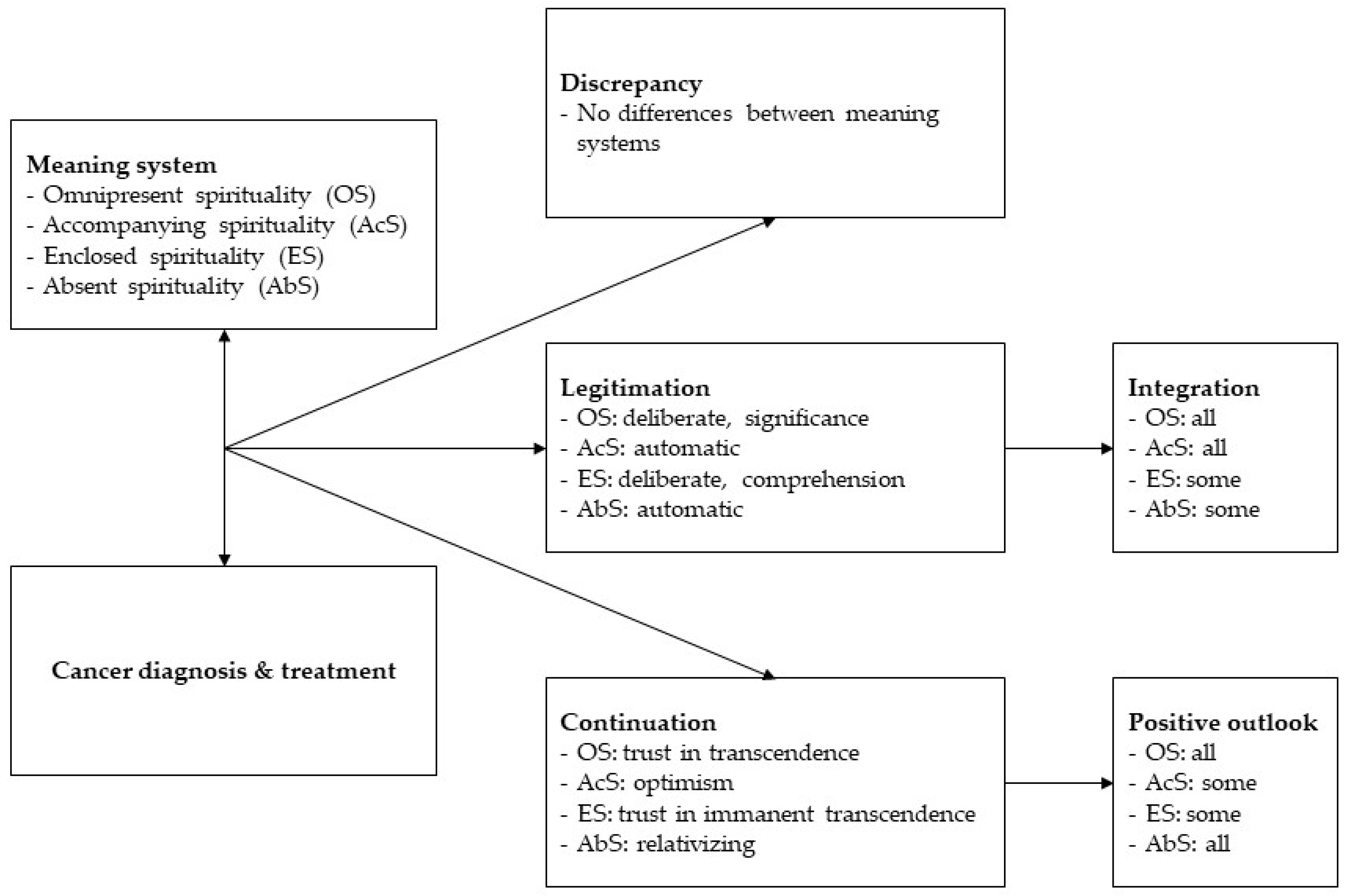

To answer the first two research questions, the interviewer (NU) and the researcher responsible for the quantitative data-collection and -analysis of the mixed-methods project (AV) summarized the role of the meaning system in each interview—independent of its categorization in a meaning system—, discussed their findings and compared the roles between interviews. After several rounds of discussion and comparison, three roles (discrepancy, legitimation and continuation) and two outcomes (integration and outlook) were identified.

To answer our third research question, the interviews were grouped in accordance with our previous categorization of meaning systems (

Uwland-Sikkema et al. 2018) and read again to understand how the content of the meaning systems related to the roles and outcomes. Tables were created that specified (1) the constituting elements of the meaning systems as defined by

Uwland-Sikkema et al. (

2018), (2) a one-sentence description of the content of these elements, (3) a one-sentence description of the role of each of these elements (whether it was discrepancy, legitimation or continuation and how this took shape), and (4) for each type of meaning system as a whole a brief summary of the outcome (integration and outlook). By comparing the contents of these tables, an understanding was reached of similarities and differences in the relation of the meaning systems to adjustment to cancer.

Trustworthiness

In addition to the procedures described above, the following procedures were used to enhance the trustworthiness of the study:

A member check was performed with 18 of the 20 interviews by sending the participant a summary of the interview for comment. All confirmed that the interpretation of their cancer experience, life-view and spirituality was correct. Two participants could not be reached.

Throughout the analytical process, peer debriefing with the advisory board of the overarching project was applied to verify the appropriateness of the analytical procedures, interpretations and terminology.

4. Discussion

In this study, it was examined how various types of spiritual meaning systems influence the emotional adjustment to cancer, on the basis of narrative interviews with 20 people who were treated for cancer with curative intent. The findings are summarized in

Figure 1.

First, a general theory was developed on the role of meaning systems in adjustment and their outcomes. It was found that the meaning system could be in discrepancy with the appraisal of cancer and it could assist in legitimizing it. If legitimation was successful, the experience of cancer was integrated into the life story. Patients also reported a striving toward continuation of valued parts of the meaning system. If this was successful, they had a positive outlook toward the future.

Second, differences in the roles between four previously identified meaning systems (

Uwland-Sikkema et al. 2018) were determined. With respect to

discrepancies, no clear differences were found between the meaning systems. Differences were found in how

legitimation and

continuation played out. Legitimation seemed to be quite deliberate among the participants with the meaning systems “Omnipresent spirituality” and “Enclosed spirituality”, whereas among the participants with the meaning systems “Accompanying spirituality” and “Absent spirituality” legitimation seemed more automatic. Also, legitimation through finding significance seemed to be more important for people with the Omnipresent spirituality meaning system, whereas legitimation seemed to center around comprehensibility for the participants with the Enclosed spirituality meaning system.

Continuation centered on a form of staying positive in all stories, but with different connotations. For the Omnipresent spirituality meaning system, this meant a continued trust in the ‘good intentions’ of the transcendent based on spiritual activities and spontaneous spiritual experiences. For the Accompanying spirituality meaning system, this meant staying optimistic or hopeful supported by a belief that a distant God would help when needed. For the Enclosed spirituality meaning system, this meant maintaining trust in an immanent transcendent reinforced by spiritual activities that allowed for a sense of control. For the Absent spirituality meaning system, this meant relativizing the seriousness of having cancer and any problems that they had faced apart from any spiritual beliefs, activities, attitudes or experiences.

Finally, differences in outcomes of adjustment were investigated between the four meaning systems. The findings in the interviews suggested that integration was reached by all participants with an Omnipresent spirituality meaning system, supported by a belief that life events happen to help them fulfil their task in life. Most participants with an Enclosed spirituality meaning system also reached integration, but seemingly with more difficulty than those with an Omnipresent spirituality meaning system due to a struggle with the experienced loss of control. Among the participants with the Accompanying or Absent spirituality meaning systems, large differences were observed in integration.

A more positive outlook was expressed by participants with an Omnipresent or an Absent spirituality meaning system, than the participants with the other two meaning systems. For the first group, this positive outlook was supported by a belief in an existence after death, whereas for the second the positive outlook seemed based on previous experiences in life.

The findings closely resemble those of the studies discussed in the introduction section. Questions about mortality, fragility, lifestyle and personal control frequently occurred in the stories of our participants and spiritual practices were mobilized in coping with these. Interestingly, however, we recognized these questions most clearly among the participants with the Accompanying and Enclosed spirituality meaning systems. Perhaps because they needed to navigate strong self-reliance with a belief in transcendence, whereas the participants with the Omnipresent spirituality meaning system relied more on transcendence and those with the Absent spirituality meaning system fully relied on themselves and their loved ones. The process of slowly relinquishing control as described by

Vonarx and Hyppolite (

2013);

Halstead and Hull (

2001); and

Hvidt (

2017) seems, thus, also most characteristic of the Accompanying and Enclosed spirituality meaning systems. Reliance on fellow patients, friends and family, as emphasized by the patients in the studies by

Hvidt (

2017) and by

Saarelainen (

2017) did not seem characteristic of any particular meaning system in our study, but was mentioned by all participants. With regard to cultural differences, we recognized the suggestion by

Ahmadi (

2006) that a relationship with God was not often invoked by our Dutch respondents. Nevertheless, several participants did refer to God as important in their lives and in coping with cancer. We also recognized all of the various ways of engaging with nature and contemplative practices from the cross-cultural studies by

Ahmadi et al. (

2017), suggesting that the Netherlands might be a particularly pluralistic society containing characteristics of both highly religious and highly secular cultures.

The findings from our study provide direct support for many of the elements in the meaning-making coping model by

Park (

2010). Discrepancies between global meaning and situational meaning were found in almost all narratives. Many of the difficulties experienced by the participants revolved around a loss of control. Spiritual activities and experiences helped to negotiate sharing responsibility between the participant and the transcendent. Efforts at meaning making, in the form of legitimation, were both automatic and deliberate. Legitimation was centered both on assimilation of the appraised meaning into the meaning system—for example, in terms of positive reappraisal within the Omnipresent spirituality meaning system or relativizing within the Absent spirituality meaning system—and on accommodation of the meaning system to the appraised meaning—for example, as changed beliefs about control within the Enclosed spirituality meaning system. However, assimilation seemed dominant. In addition, both searching for comprehensibility and searching for significance occurred. Finally, meaning-making coping took place both at the cognitive level and the emotional level.

Park (

2010) asked which meaning system might be more conducive to assimilation and, with that, less vulnerable to discrepancies. It was found that legitimation and continuation were most successful among the participants with an Omnipresent spirituality meaning system. The strong sense of trust in the transcendent expressed by these participants and the belief that life events have a supportive purpose seemed to contribute to this successful adjustment.

With regard to the outcomes of meaning-making,

Park (

2010) suggested that these can be categorized as acceptance, causal (re-)attributions, changes in identity, growth and positive life changes, reappraisals of the event (especially in relation to previous negative life events), changed global belief and goals, and a changed sense of meaning in life. This does not seem to fit the outcomes observed in this study (integration and positive outlook). This is mainly because the categorization does not explicitly acknowledge that the ascription of “no meaning” can also be meaning (albeit an insecure one), such as was observed within the Accompanying and Absent spirituality meaning systems. Instead,

Kunkel et al. (

2014) offer a typology of meanings that seems to do more justice to this finding. They describe how the processes of assimilation/accommodation and searching for comprehensibility/significance interact among people coping with grief to produce four types of outcomes or meanings-made: Sensemaking (assimilation and comprehensibility), Acceptance or resignation without understanding (accommodation and comprehensibility), Realization of benefits via positive reappraisal (assimilation and significance), and Realignment of roles and relationships (accommodation and significance). The outcomes mentioned by Park are subsumed within this categorization, but it does not seem to presuppose that meanings-made are solid at the time of their discovery, to the extent the categorization of Park does. Nevertheless, the meanings-made identified by

Kunkel et al. (

2014) seem to only refer to what was named ‘integration’ here, involving changes to one’s story about oneself and one’s relationship to the environment. Beside integration, an important meaning-made in the present study was having a positive outlook toward the future. This seemed to result from the process of continuation and did not involve changes to one’s life story. Instead, it implied an attitude of trust and positivity.

4.1. Limitations

Due to the use of qualitative interviews, this study highly depended on the reflective and expressive capacities of our participants. This means that important aspects of both spirituality and coping that cannot be expressed into words may have been missed. Spirituality and meaning can also be experienced on a more visceral level, in experiences of connectedness, motivation and (self-) transcendence (

van der Lans 1996;

Smit 2015) which are not captured in an interview. In addition, spirituality was operationalized as ‘life view’ or ‘attitude in life’ during the interviews, which might imply a cognitive bias toward spirituality. Nevertheless, the participants mentioned several emotional and physical elements to spirituality and adjustment as evidenced in the process of continuation.

The findings might not be generalizable to people in other circumstances, be it other types of cancer, people of a different age, nationality, ethnicity or educational level, or a study with a different interviewer. We did not find any suggestions that the type or stage of cancer, or the type of treatment received influenced the role of spirituality in adjustment or adjustment itself. However, given the small sample size, such influence cannot be ruled out.

The study involved a cross-sectional, retrospective design which also means that it is unclear to what extent the adjustment process described here reflects the process that has actually taken place in the moment. A longitudinal study is needed to test this.

Despite the potential limitations of this design, the interviews and narrative approach to them have allowed us to gain a better insight into the developmental process that the patients have experienced in relation to the diagnosis and treatment of cancer. Other approaches, such as a questionnaire study, would not have allowed for the interactions between various beliefs, practices and experiences to have surfaced. Narrative interviews allow participants to select and order events and experiences in the way they deem important for the particular situation (

Ayres 2008;

Riessman 2008). Given that the informants knew that the purpose of the project was to study the role of spirituality in coping with cancer and that most of the questions focused on the role of the person’s life view in the experience of cancer, it might be assumed that what was uncovered was of high importance to the participants during the past year, even though it remains uncertain whether these were the only themes of importance in the process of adjustment.

Donders (

2004) stresses that telling the story of cancer is a form of coping for the participants, which means that to some extent the findings have been constructed during the interview itself. We have verified our findings regarding differences in outcomes between the types of meaning systems with the use of Kruskal–Wallis tests on the questionnaire data of the interviewees. We found that the participants with the Omnipresent or Absent spirituality meaning systems reported higher well-being and lower distress than the participants with the Accompanying or Enclosed spirituality meaning systems. These analyses also indicated that this difference in adjustment might be a consequence of differences in fatigue instead of in meaning systems between the groups of participants. On the other hand, the measure of fatigue used was a self-report measure that asked for subjective experiences. It is, therefore, also possible that the groups appraised the symptoms of fatigue differently based on their respective meaning systems. This hypothesis is supported in a quantitative study from the project of which this study is a part. In that study we found that the spirituality aspects of Meaningfulness, which might be deemed characteristic of the Omnipresent spirituality meaning system, and Acceptance, which might be deemed characteristic of the Absent spirituality meaning system, buffered the impact of fatigue on distress (

Visser et al. 2018).

Finally, we acknowledge that the creation of a typology reduces the richness of the information and hides certain beliefs, practices and experiences. However, a typology also helps to uncover similarities and patterns, and facilitates comparison. Particularly for clinical practice, typologies can point to a manageable amount of points of attention in conversations with patients.

4.2. Implications

The findings from the present study suggest that healthcare practitioners need to pay close attention to the nature of the (spiritual) meaning system of their patients to provide the appropriate support. The nature of beliefs about control and attitudes of positivity can influence how much a person struggles with the diagnosis and treatment of cancer. What seems to be of particular importance is that the person can see some type of benefit or positive meaning to the experience, as did the people with an Omnipresent spirituality meaning system, or that their daily lives remain uninterrupted, as among the people with an Absent spirituality meaning system. Thus, care providers should ask about these experiences and about the beliefs and attitudes that underlie them.

But should the care professional then either stimulate the person to think about the experience very deliberately or to ‘ignore’ it? Studies on narrative interventions among cancer patients suggest that stimulating deliberate meaning making can be helpful (

Kruizinga et al. 2016). But such interventions might only be attractive to people who are already inclined to do so. Differences in deliberate or automatic meaning-making and in integration might reflect a difference in thinking styles of the participants (

Sternberg 1999). It seemed that the participants with the Omnipresent and Enclosed spirituality meaning systems relied more on global thinking in search for hidden meanings, whereas those with the Accompanying and Absent spirituality meaning systems relied more on local thinking in their focus on everyday experience. Local thinking may offer less opportunities for durable accommodation or assimilation of meaning, which might leave the person with a sense of insecurity about the future. On the other hand, it might also offer the opportunity to relativize (reappraise) the impact of the disease. Thus, more research on this type of processing is recommended.

Another aspect that needs to be taken into account in care is how the cancer is appraised in comparison to previous life events. As might be expected in a meaning systems perspective, it became clear during the interviews that the process of adjustment to cancer was not only influenced by spirituality, but also by past or current other negative life events. Several participants evaluated the experience of cancer as less severe than, for example, their previous experience of a broken relationship, the death of a loved one, or losing their job. In one interview, the fear of having to go to a nursing home because of physical, age-related, deterioration, was a more prominent theme than the experience of cancer. Earlier life events also contributed to experiences of trust and confidence in being able to cope with cancer.

A final question for intervention is whether these adjustment processes take place in the environs of care professionals. As several studies have already indicated (

Gall et al. 2009;

Heim et al. 1997;

Sehlen et al. 2003), and the stories of the participants confirm, much of the coping process takes place in the private sphere and the full scale of the implications of having (had) cancer do not become clear until medical treatment draws to a close or is completed. Nevertheless, some of the participants in this study were still receiving immunotherapy and all participants still had regular check-ups at the hospital, providing care professionals with the opportunity to monitor and perhaps intervene in emotional adjustment. Hospital chaplains will be of valuable assistance in this, because they are specifically trained to understand the meaning system of the person and to support questions about comprehensibility, significance and continuation.