Popular Religion, Sacred Natural Sites, and “Marian Verdant Advocations” in Spain

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Marian Popular Devotions and The Religious Significance of Plants

3. Research Methods

4. Results

4.1. Frequency of Marian Verdant Advocations

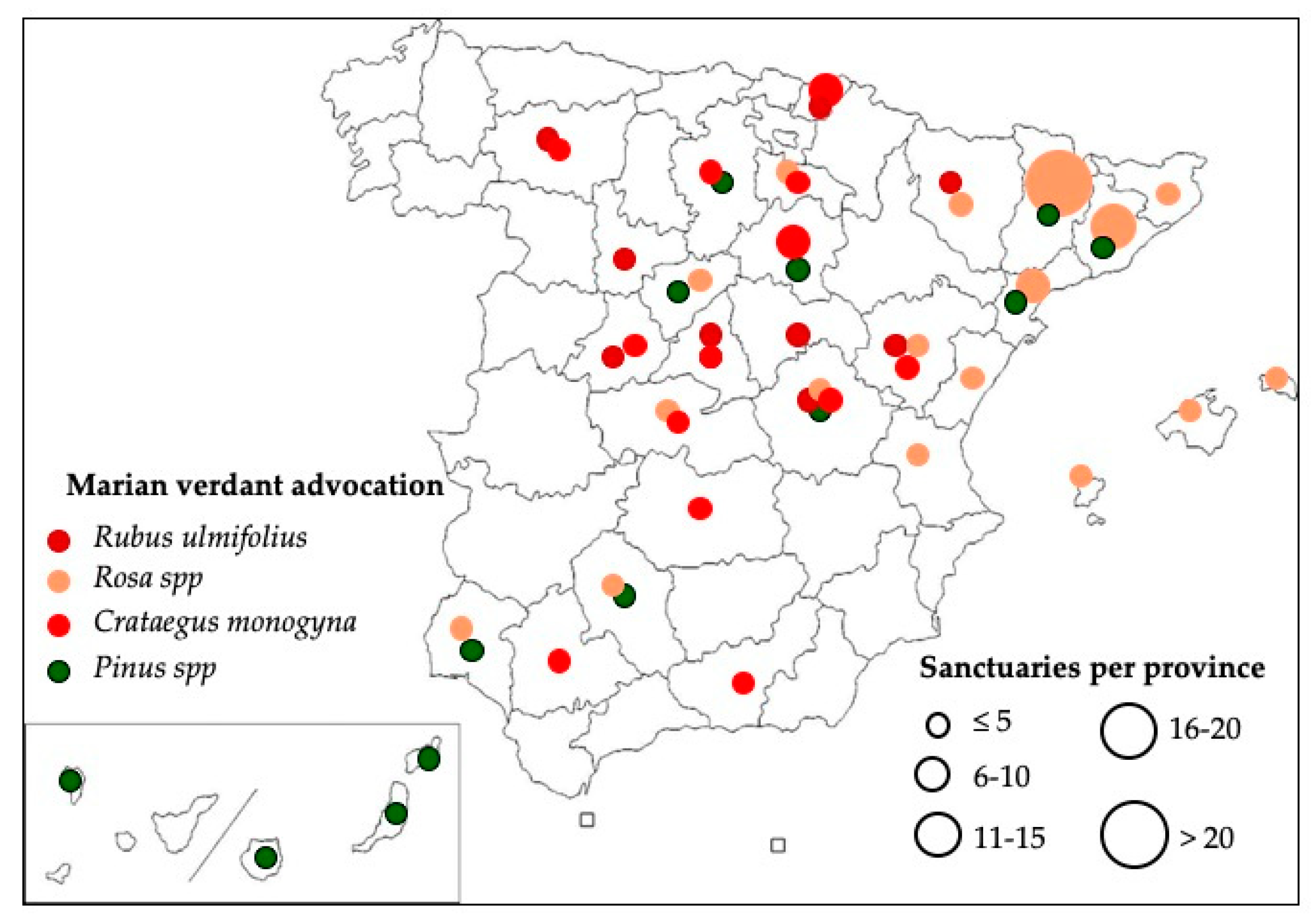

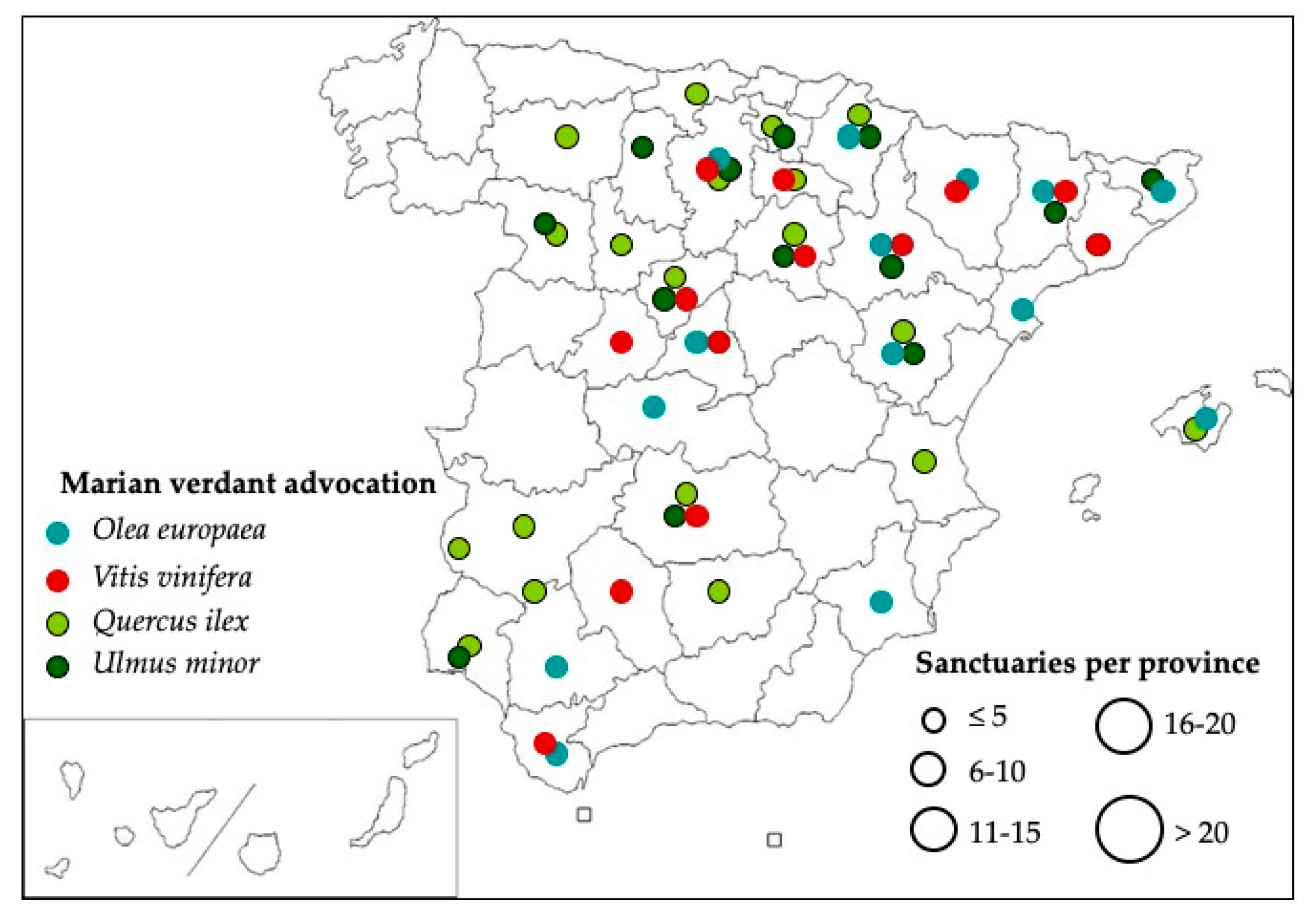

4.2. Vegetation Types

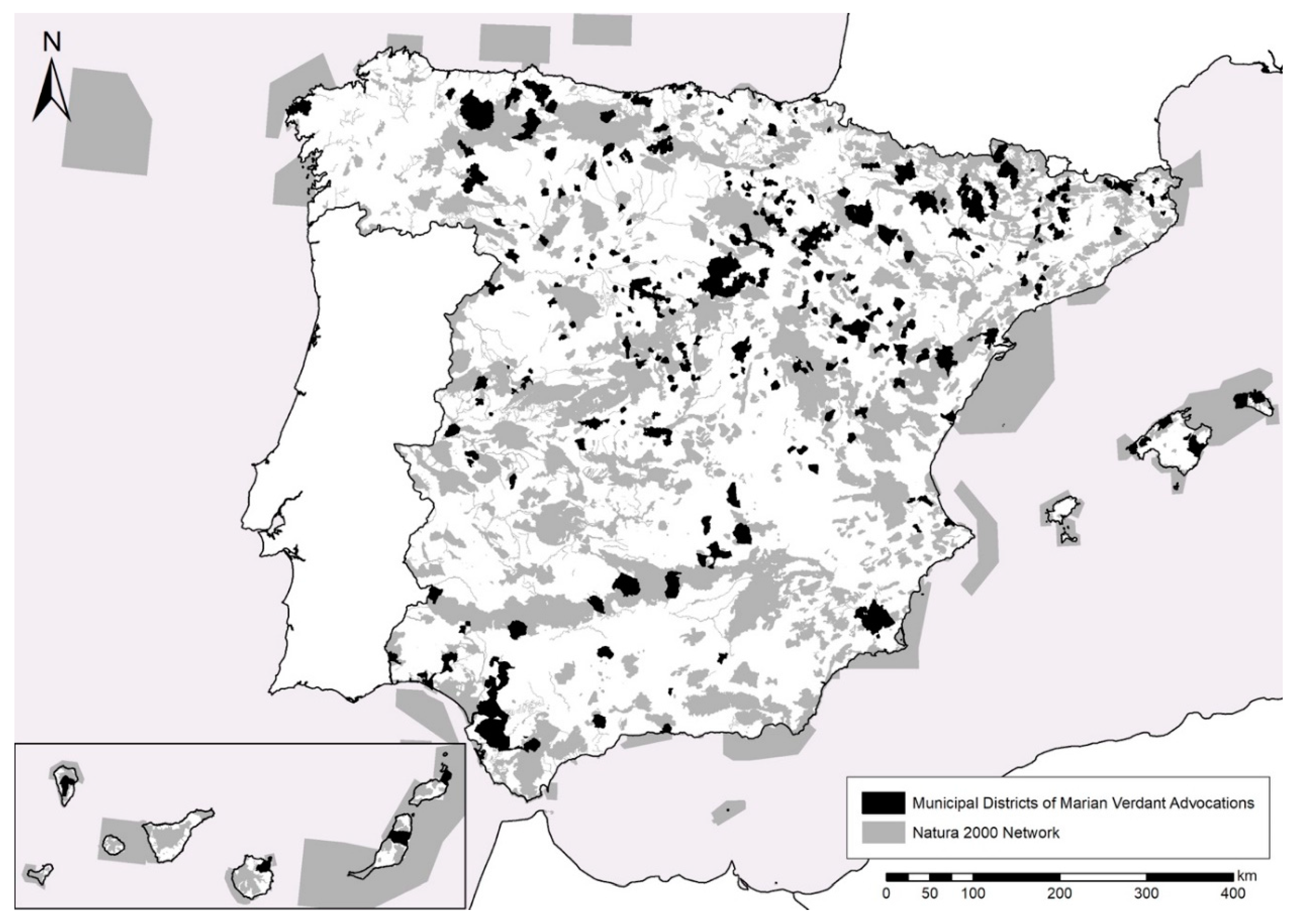

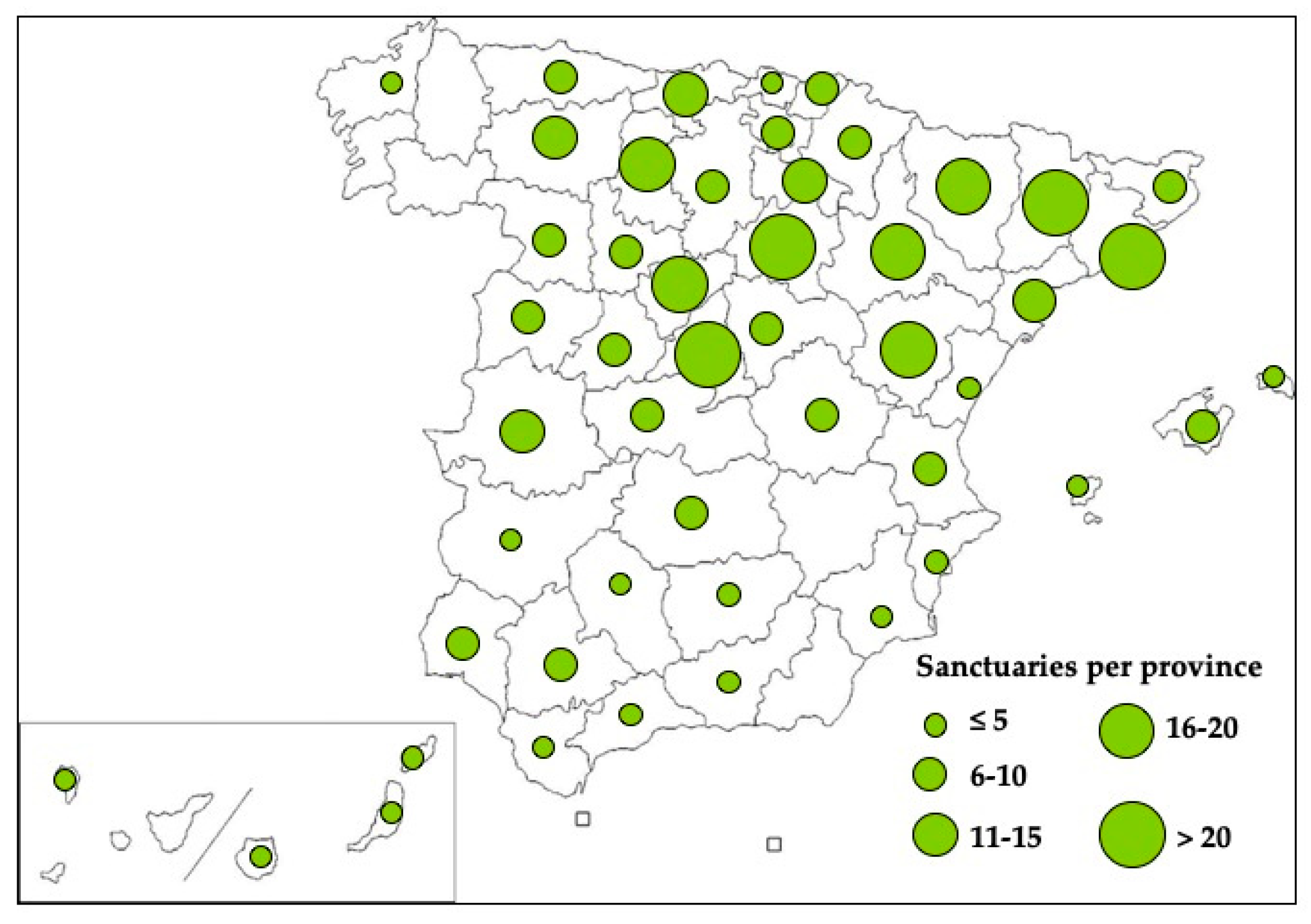

4.3. Geographical Distribution

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abad León, Felipe. 1990. Guía para Visitar los Santuarios Marianos de La Rioja. Madrid: Encuentro Ediciones. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, Judith. 2006. Cultivating Wilderness: Environmentalism and Legacies of Early Christian Ascetism. Society for Comparative Study of Society and History 48: 4–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amengual i Batle, Josep. 1997. Guía para Visitar los Santuarios Marianos de Baleares. Madrid: Encuentro Ediciones. [Google Scholar]

- Batalla Gardella, Salvador. 2002. Santuarios. Guía de Turismo y Peregrinación. Madrid: EDICEL. [Google Scholar]

- Bernbaum, Edwin. 2012. Sacred mountains and national parks: spiritual and cultural values as a foundation for environmental conservation. In Sacred Species and Sites. Advances in Biocultural Conservation. Edited by Gloria Pungetti, Gonzalo Oviedo and Della Hooke. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 83–96. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, Evan. 2015. Devoted to Nature. The Religious Roots of American Environmentalism. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bhagwat, Shonil A., and Claudia Rutte. 2006. Sacred groves: Potential for biodiversity management. Front Ecol Environ 4: 519–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero Mújica, Francisco. 1999. Guía para Visitar los Santuarios Marianos de Canarias. Madrid: Encuentro Ediciones. [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco Terriza, Manuel Jesús. 1992. Guía para Visitar los Santuarios Marianos de Andalucía Occidental. Madrid: Encuentro Ediciones. [Google Scholar]

- Carreres i Péra, Joan. 1988. Guía para Visitar los Santuarios Marianos de Cataluña. Madrid: Encuentro Ediciones. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, Michael P. 1986. The Cult of the Virgin Mary. Psychological Origins. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cebrián Franco, Juan José. 1989. Guía para Visitar los Santuarios Marianos de Galicia. Madrid: Encuentro Ediciones. [Google Scholar]

- Cinquepalmi, Federico, and Gloria Pungetti. 2012. Ancient Knowledge, the sacred and biocultural diversity. In Sacred Species and Sites. Advances in Biocultural Conservation. Edited by Gloria Pungetti, Gonzalo Oviedo and Della Hooke. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 46–62. [Google Scholar]

- Colding, Johan, and Carl Folke. 2001. Social Taboos: “Invisible” Systems of Local Resource Management and Biological Conservation. Ecological Applications 11: 584–600. [Google Scholar]

- Colding, Johan, Carl Folke, and Thomas Elmquvist. 2003. Social institutions in ecosystem management and biodiversity conservation. Tropical Ecology 44: 25–41. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, Michael, Sergio Villamayor-Tomas, and Yasha Hartberg. 2014. The Role of Religion in Community-based Natural Resource Management. World Development 54: 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crews, Judith. 2003. Forest and tree symbolism in folklore. Unasylva 54: 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Delclaux, Federico. 1991. Guía para Visitar los Santuarios Marianos de Madrid. Madrid: Encuentro Ediciones. [Google Scholar]

- Dudley, Nigel, and Liza Higgins-Zogib. 2012. Protected areas and sacred nature: a convergence of beliefs. In Sacred Species and Sites. Advances in Biocultural Conservation. Edited by Gloria Pungetti, Gonzalo Oviedo and Della Hooke. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 36–45. [Google Scholar]

- Dudley, Nigel, Liza Higgins-Zogib, and Stephanie Mansourian. 2008. The Links between Protected Areas, Faiths, and Sacred Natural Sites. Conservation Biology 23: 568–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, Julian. 2014. God’s Trees. Trees, Forests and Wood in the Bible. Leominster: Day One Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Álvarez, Florentino. 1990. Guía para Visitar los Santuarios Marianos de Asturias. Madrid: Encuentro Ediciones. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Sánchez, Teodoro. 1994. Guía para Visitar los Santuarios Marianos de Extremadura. Madrid: Encuentro Ediciones. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Ladreda, Clara. 1989. Guía para Visitar los Santuarios Marianos de Navarra. Madrid: Encuentro Ediciones. [Google Scholar]

- Ferri Chulio, Andrés de Sales. 2000. Guía para Visitar los Santuarios Marianos de Valencia y Murcia. Madrid: Encuentro Ediciones. [Google Scholar]

- Folke, Carl, Reinette Biggs, Albert V. Norström, Belinda Reyers, and Johan Rockström. 2016. Social-ecological resilience and biosphere-based sustainability science. Ecology and Society 21: 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frascaroli, Fabrizio. 2013. Catholicism and Conservation: The Potential of Sacred Natural Sites for Biodiversity Management in Central Italy. Human Ecology 41: 587–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, Gary T. 2002. Invoking the Spirit: Religion and Spirituality in the Quest for a Sustainable World. Washington: Worldwatch Institute. [Google Scholar]

- González Echegaray, María del Carmen. 1993. Guía para Visitar los Santuarios Marianos de Cantabria. Madrid: Encuentro Ediciones. [Google Scholar]

- Graef, Hilda. 2009. Mary: A History of Doctrine and Devotion. Notre Dame: Ave Maria Press. [Google Scholar]

- Graves, Charles. 1876. The Ogham Alphabet. Hermathena 2: 443–72. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, Robert P. 1992. Forests: The Shadow of Civilization. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- von Hellermann, Pauline. 2016. Tree Symbolism and Conservation in the South Pare Mountains, Tanzania. Conservation and Society 14: 368–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooke, Della. 2012. The sacred tree in the belief and mythology of England. In Sacred Species and Sites. Advances in Biocultural Conservation. Edited by Gloria Pungetti, Gonzalo Oviedo and Della Hooke. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 307–21. [Google Scholar]

- Horsfall, Sara. 2000. The experience of Marian apparitions and the Mary cult. The Social Science Journal 37: 375–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iturrate, José. 2000. Guía para Visitar los Santuarios Marianos de los Territorios Históricos de Álava, Guipúzcoa y Vizcaya. Madrid: Encuentro Ediciones. [Google Scholar]

- Lawler, Ronald David. 1984. Divine Faith, Private Revelation, Popular Devotion. Marian Studies 35: 100–10. [Google Scholar]

- Llamas, Enrique. 1992. Guía para Visitar los Santuarios Marianos de Castilla-León. Madrid: Encuentro Ediciones. [Google Scholar]

- López Martín, Juan. 1998. Guía para Visitar los Santuarios Marianos de Andalucía Oriental. Madrid: Encuentro Ediciones. [Google Scholar]

- Mallarach, Josep-Maria, Josep Corcó, and Thymio Papayannis. 2014. Christian Monastic Communities Living in Harmony with the Environment: An Overview of Positive Trends and Best Practices. Studia Monastica 56: 353–92. [Google Scholar]

- Mallarach, Josep-Maria, Josep Corcó, and Thymio Papayannis. 2016. Christian Monastic Lands as Protected Landscapes and Community Conserved Areas: An Overview. Parks 22: 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, Elisabeth, and Martin Palmer. 2015. Why Conservation Needs Religion. Coastal Management 43: 238–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mettinger, Tryggve N. D. 2007. The Eden Narrative: A Literary and Religio-historical Study of Genesis 2–3. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, Nathan D. 2009. The Mystery of the Rosary: Marian Devotion and the Reinvention of Catholicism. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Morales, Ramón. 2000. Diversidad en labiadas mediterráneas y macaronésicas. Portugaliae Acta Biologica 19: 31–48. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, Jiménez, and José Miguel. 1997. Los santuarios rurales en España: paisaje y paraje (la ordenación sagrada del territorio). In Religiosidad Popular en España: Actas del Simposium. Edited by Campos Fernández de Sevilla and Francisco Javier. Madrid: EDES, vol. II, pp. 307–28. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz Jiménez, José Miguel. 2010. Arquitectura, Urbanismo y Paisaje en los Santuarios Rurales Españoles. Madrid: Gea Patrimonio. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, Elinor. 1990. Governing the Commons. The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, Elinor. 2009. A General Framework for Analyzing Sustainability of Social-Ecological Systems. Science 325: 419–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviedo, Gonzalo. 2012. Spiritual values and conservation. In Sacred Species and Sites. Advances in Biocultural Conservation. Edited by Gloria Pungetti, Gonzalo Oviedo and Della Hooke. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Pack, Sasha D. 2010. Revival of the Pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela: The Politics of Religious, National, and European Patrimony, 1879–1988. The Journal of Modern History 82: 335–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, Martin, and Victoria Finlay. 2003. Faith in Conservation. New Approaches to Religions and the Environment. Washington: The World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Posey, Darrell A. 1999. Introduction: Culture and Nature—The Inextricable Link. In Cultural and Spiritual Values of Biodiversity. Edited by Darrell A. Posey. London: UNEP and Intermediate Technology Publications, pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Pozo Rivera, Enrique, Javier Gutierrez Puebla, Juana Rodríguez Moya, Susana Ramirez García, Gabriel Gómez Cerdá, and Juan Carlos García Palomares. 2013. Caracterización Socioeconómica de la Red Natura 2000 en España. Madrid: Ministerio de Agricultura, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente. [Google Scholar]

- Pungetti, Gloria. 2013. Biocultural Diversity for Sustainable Ecological, Cultural and Sacred Landscapes: The Biocultural Landscape Approach. In Landscape Ecology for Sustainable Environment and Culture. Edited by Bojie Fu and Bruce Jones. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 55–76. [Google Scholar]

- Pungetti, Gloria, Gonzalo Oviedo, and Della Hooke. 2012. Sacred Species and Sites. Advances in Biocultural Conservation. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pungetti, Gloria, Gonzalo Oviedo, and Della Hooke. 2012. Conclusions: the journey to biocultural conservation. In Sacred Species and Sites. Advances in Biocultural Conservation. Edited by Gloria Pungetti, Gonzalo Oviedo and Della Hooke. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 442–53. [Google Scholar]

- Pungetti, Gloria, Peter Hughes, and Oliver Rackham. 2012. Ecological and spiritual values of landscape: a reciprocal heritage and custody. In Sacred Species and Sites. Advances in Biocultural Conservation. Edited by Gloria Pungetti, Gonzalo Oviedo and Della Hooke. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 65–82. [Google Scholar]

- Raunkiaer, Christen C. 1934. The Life Forms of Plants and Statistical Plant Geography. London: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas Martínez, Salvador. 1987. Memoria del Mapa de Series de Vegetación de España 1: 400.000. Madrid: Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación. [Google Scholar]

- Romero, Gilbert C. 1993. The Bible, Revelation, and Marian Devotion. Marian Studies 44: 19–40. [Google Scholar]

- Roten, Johann G. 1994. Popular Religion and Marian Images. Marian Studies 45: 62–120. [Google Scholar]

- Ryder, John H. 1974. Our Lady of Eden. Marian Studies 25: 65–81. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez Ferrer, José. 1995. Guía para Visitar los Santuarios Marianos de Castilla-La Mancha. Madrid: Encuentro Ediciones. [Google Scholar]

- Swiderska, Krystyna. 2011. Protecting Traditional Knowledge: A Holistic Approach Based on Customary Laws and Bio-Cultural Heritage. In Conserving and Valuing Ecosystem Services and Biodiversity. Economic, Institutional and Social Challlenges. Edited by Karachepone Ninan. London: Routldege, pp. 331–44. [Google Scholar]

- Tatay, Jaime, and Catherine Devitt. 2017. Sustainability and Interreligious Dialogue. Islamochristiana 43: 123–39. [Google Scholar]

- Torra de Arana, Eduardo. 1996. Guía para Visitar los Santuarios Marianos de Aragón. Madrid: Encuentro Ediciones. [Google Scholar]

- Verschuuren, Bas, and Steve Brown. 2018. Cultural and Spiritual Significance of Nature in Protected and Conserved Areas. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Verschuuren, Bas, Josep-Maria Mallarach, and Gonzalo Oviedo. 2008. Sacred sites and protected areas. In Defining Protected Areas. Edited by Nigel Dudley and Sue Stolton. Gland: IUCN, pp. 164–69. [Google Scholar]

- Virtanen, Pekka. 2002. The Role of Customary Institutions in the Conservation of Biodiversity: Sacred Forests in Mozambique. Environmental Values 11: 227–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, Marina. 2016. Alone of all Her Sex. The Myth and the Cult of the Virgin Mary. Oxford: Oxford University Press. First published 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins, Eithne. 1969. The Rose-Garden Game: The Symbolic Background to the European Prayer-Beads. London: Gollancz. [Google Scholar]

- Winston-Allen, Anne. 2005. Stories of the Rose. The Making of the Rosary in the Middle Ages. University Park: Penn State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, Aaron T. 2017. The Spirit of Dialogue: Lessons from Faith Traditions in Transforming Conflict. Washington: Island Press. [Google Scholar]

- WWF-ARC. 2005. Beyond Belief. Linking Faiths and Protected Areas to Support Biodiversity Conservation. Manchester: WWF. [Google Scholar]

| Christian Sacred Site. | Nature Preserve (Natura 2000) | Province |

|---|---|---|

| Ermita de la Mare de Déu dels Lliris | Parc Natural de la Font Roja | Alicante |

| Santuario de la Virgen de Covadonga | Parque Nacional de Picos de Europa | Asturias |

| Monestir de Montserrat | Parc Natural de la Muntanya de Montserrat | Barcelona |

| Monasterio de Santo Toribio de Liébana | Parque Nacional de Picos de Europa | Cantabria |

| Ermita de la Virgen de la Cueva Santa | Parque Natual de la Sierra Calderona | Castellón |

| Ermita de Nuestra Señora de los Reyes | Parque Natural de la Dehesa | El Hierro |

| Santuari de la Mare de Déu de Núria | Parc Natural de les Capçaleres del Ter i el Freser | Girona |

| Santuario de la Virgen de la Salud | Parque Natural del Barranco del Río Dulce | Guadalajara |

| Santuario de la Virgen de Arantzazu | Espacio Natural de Aizkorri-Aratz | Guipúzcoa |

| Ermita de la Virgend de Lourdes | Parque Nacional de Garajonay | La Gomera |

| Ermita de la Virgen del Pino | Parque Nacional de la Caldera de Taburiente | La Palma |

| Monasterio de Nuestra Señora de Valvanera | Parque Natural de la Sierra Cebollera | La Rioja |

| Ermita de Nuestra Señora de los Dolores | Parque Nacional de Timanfaya | Lanzarote |

| Ermita de la Virgen de Navalazarza | Espacio Natural de la Dehesa de Moncalvillo | Madrid |

| Santuari de la Mare de Déu de Lluc | Paratge Natural de la Serra de Tramuntana | Mallorca |

| Monasterio de Leyre | Sierra de Leyre | Navarra |

| Santuario de la Peña de Francia | Parque Natural de Las Batuecas-Sierra de Francia | Salamanca |

| Monestir de Poblet | Parc Natural de les Muntanyes de Prades i Poblet | Tarragona |

| Santuario de la Virgen de las Nieves | Parque Nacional del Teide | Tenerife |

| Santuario de la Virgen del Tremedal | Espacio Natural de los Montes Universales | Teruel |

| Family. | Species | n. | Σ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rosaceae | Rosa spp. | Rose | 64 | 126 |

| Crataegus monogyna | Common hawthorn | 30 | ||

| Rubus ulmifolius | Elmleaf blackberry | 18 | ||

| Malus domestica | Apple | 8 | ||

| Pyrus spp. | Pear | 3 | ||

| Prunus avium | Wild cherry | 1 | ||

| Prunus dulcis | Almond | 1 | ||

| Prunus spp. | Plum | 1 | ||

| Fagaceae | Quercus ilex | Holly oak | 38 | 59 |

| Quercus spp. | Oak | 14 | ||

| Castanea sativa | Sweet chestnut | 4 | ||

| Fagus sylvatica | Beech | 3 | ||

| Ulmaceae | Ulmus minor | Field elm | 24 | 29 |

| Celtis australis | European nettle tree | 5 | ||

| Oleaceae | Olea europaea | Olive | 22 | 26 |

| Fraxinus excelsior | European ash | 4 | ||

| Pinaceae | Pinus spp. | Pine | 9 | 22 |

| Pinus canariensis | Canary Island pine | 7 | ||

| Pinus pinaster | Maritime pine | 4 | ||

| Pinus halepensis | Aleppo pine | 1 | ||

| Pinus sylvestris | Scots pine | 1 | ||

| Vitaceae | Vitis vinifera | Common grape vine | 20 | 20 |

| Family | Species | n. | Σ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salicaceae | Salix spp. | Willow | 8 | 12 |

| Populus nigra | Black poplar | 4 | ||

| Poaceae | Stipa tenacissima | Esparto grass | 5 | 10 |

| Hay | Hay | 4 | ||

| Phragmites communis | Common reed | 1 | ||

| Lamiaceae | Rosmarinus officinalis | Rosemary | 9 | 9 |

| Ericaceae | Erica spp. | Heath | 6 | 7 |

| Arbutus canariensis | Canary madrone | 1 | ||

| Juncaceae | Juncus spp. | Reed | 7 | 7 |

| Moraceae | Morus alba | White mulberry | 4 | 6 |

| Ficus carica | Fig | 2 | ||

| Araliaceae | Hedera helix | Common ivy | 5 | 5 |

| Punicaceae | Punica granatum | Pomegranate | 5 | 5 |

| Aquifoliaceae | Ilex aquifolium | Holly | 3 | 3 |

| Betulaceae | Corylus avellana | Hazel | 3 | 3 |

| Cistaceae | Cistus spp. | Rockrose | 3 | 3 |

| Cupressaceae | Juniperus oxycedrus | Prickly juniper | 3 | 3 |

| Taxaceae | Taxus baccata | Yew | 3 | 3 |

| Buxaceae | Buxus sempervirens | European box | 2 | 2 |

| Fabaceae | Ulex parviflorus | Gorse | 1 | 2 |

| Genista spp. | Broom | 1 | ||

| Liliaceae | Lilium spp. | Lily | 2 | 2 |

| Apiaceae | Foeniculum vulgare | Fennel | 1 | 1 |

| Brassicaceae | Raphanus sativus | Radish | 1 | 1 |

| Chenopodiaceae | Beta vulgaris | Beet | 1 | 1 |

| Juglandaceae | Juglans regia | Walnut | 1 | 1 |

| Myrtaceae | Myrtus communis | Mirtle | 1 | 1 |

| Palmaceae | Phoenix dactylifera | Date palm | 1 | 1 |

| Polypodiopsida | Polypodiopsida | Fern | 1 | 1 |

| Rutaceae | Citrus aurantium | Orange tree | 1 | 1 |

| Species | Marian Advocation | n. | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster I | Rosa spp. | Rose | Roser, Rosa | 64 | 15.2 |

| Quercus ilex | Holly oak | Encina, Encinar, Encinillas, Carrasco, Carrascal, Lluc | 38 | 9 | |

| Crataegus monogyna | Common hawthorn | Espino, Arantzazu | 30 | 7.1 | |

| Cluster II | Ulmus minor | Field elm | Olmo, Olmeda, Olmacedo, Oms, Omedes | 24 | 5.7 |

| Olea europaea | Olive | Oliva, Olivar, Olivares | 22 | 5.2 | |

| Pinus spp. | Pine | Pino, Pinar, Pinarejo | 22 | 5.2 | |

| Vitis vinifera | Common grape vine | Vid, Viña, Viñas, Viñedo, Parral, Parrales, Vinyet, Raïmat | 20 | 4.8 | |

| Rubus ulmifolius | Elmleaf blackberry | Zarza, Zarzuela, Zarzaquemada, Navalazarza | 18 | 4.3 | |

| Cluster III | Rosmarinus officinalis | Rosemary | Romero, Romeral | 9 | 2.1 |

| Salix spp. | Willow | Salcedo, Salceda, Salcedón, Sargar, Saz, Salz | 8 | 1.9 | |

| Juncus spp. | Reed | Juncal, Junquera, Junqueres, Xunqueira | 7 | 1.7 | |

| Erica spp. | Heath | Brezo, Brezales, Bruguers | 6 | 1.4 | |

| Stipa tenacissima | Esparto grass | Atocha, Atotxa | 5 | 1.2 | |

| Hedera helix | Common ivy | Hiedar, Yedra, Heura | 5 | 1.2 | |

| Punica granatum | Pomegranate | Granada, Granado | 5 | 1.2 | |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tatay-Nieto, J.; Muñoz-Igualada, J. Popular Religion, Sacred Natural Sites, and “Marian Verdant Advocations” in Spain. Religions 2019, 10, 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10010046

Tatay-Nieto J, Muñoz-Igualada J. Popular Religion, Sacred Natural Sites, and “Marian Verdant Advocations” in Spain. Religions. 2019; 10(1):46. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10010046

Chicago/Turabian StyleTatay-Nieto, Jaime, and Jaime Muñoz-Igualada. 2019. "Popular Religion, Sacred Natural Sites, and “Marian Verdant Advocations” in Spain" Religions 10, no. 1: 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10010046

APA StyleTatay-Nieto, J., & Muñoz-Igualada, J. (2019). Popular Religion, Sacred Natural Sites, and “Marian Verdant Advocations” in Spain. Religions, 10(1), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10010046