Investigation on Improving Strategies for Navigation Safety in the Offshore Wind Farm in Taiwan Strait

Abstract

:1. Introduction

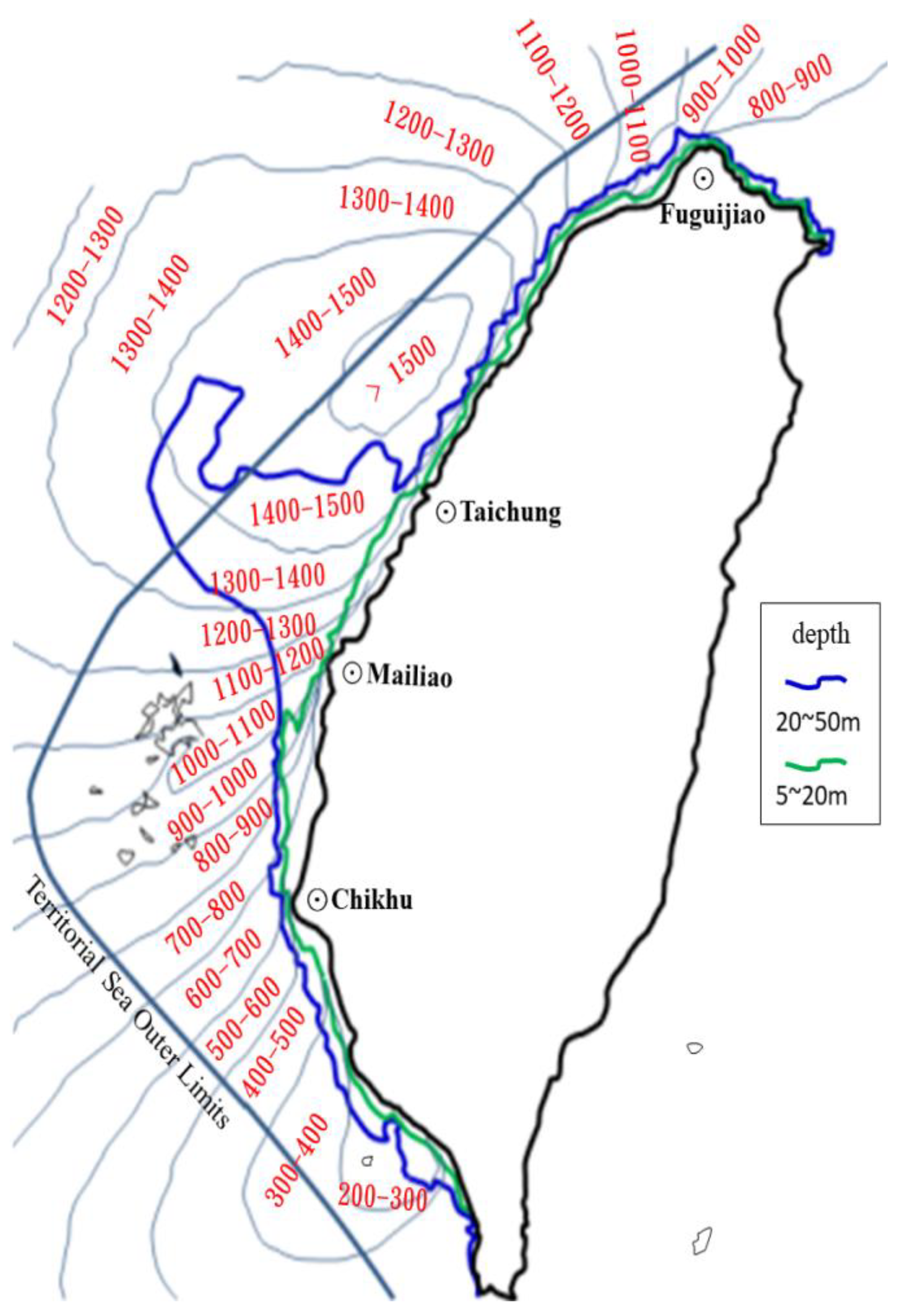

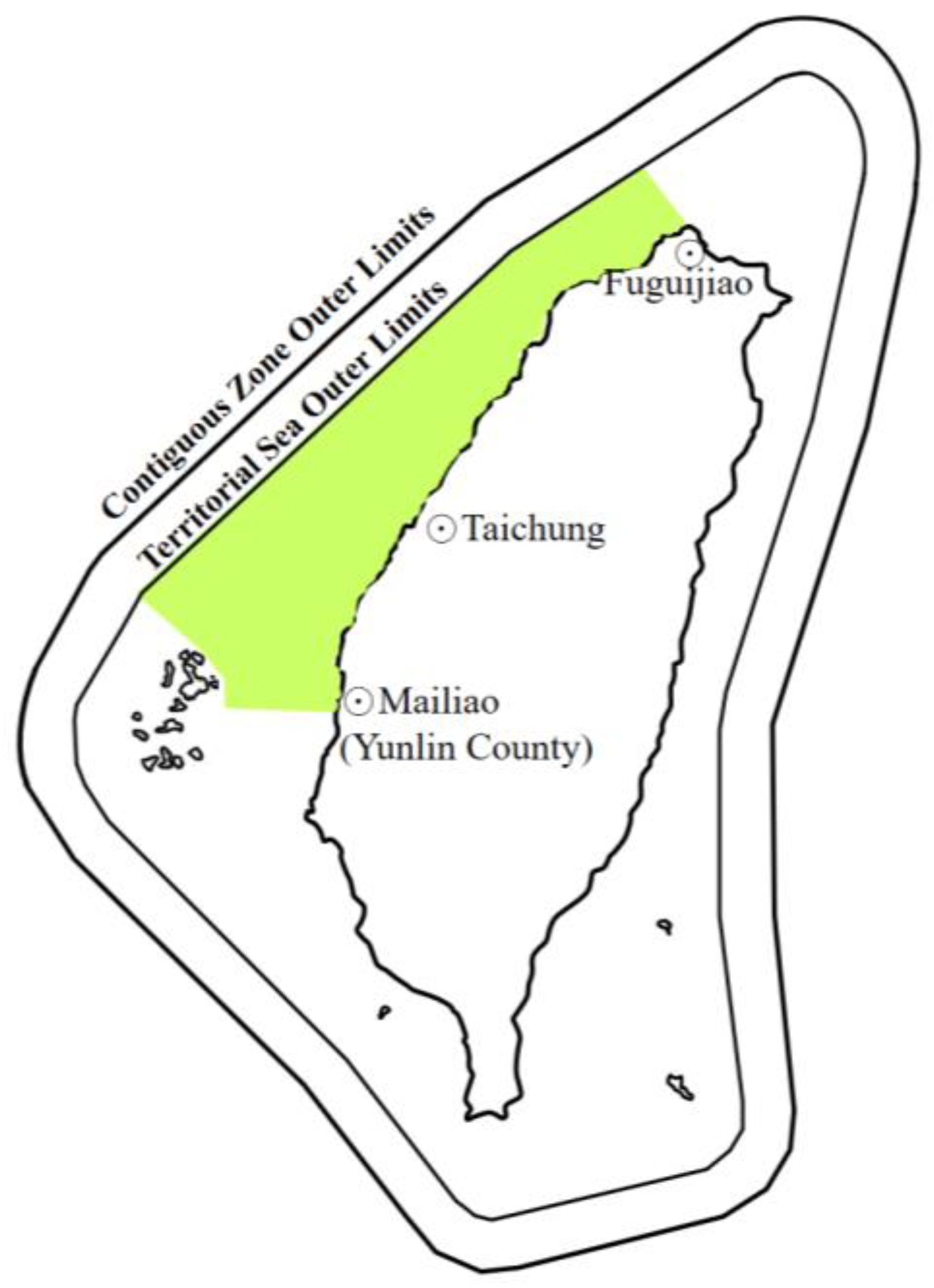

- Introduction:Briefly describe Taiwan’s offshore wind farm policy and environmental profile.

- Establishment of traffic flow management in navigation channel within offshore wind farms:Conduct structured interviews with five captains who have sailed more than 50 voyages in the western sea of Taiwan.

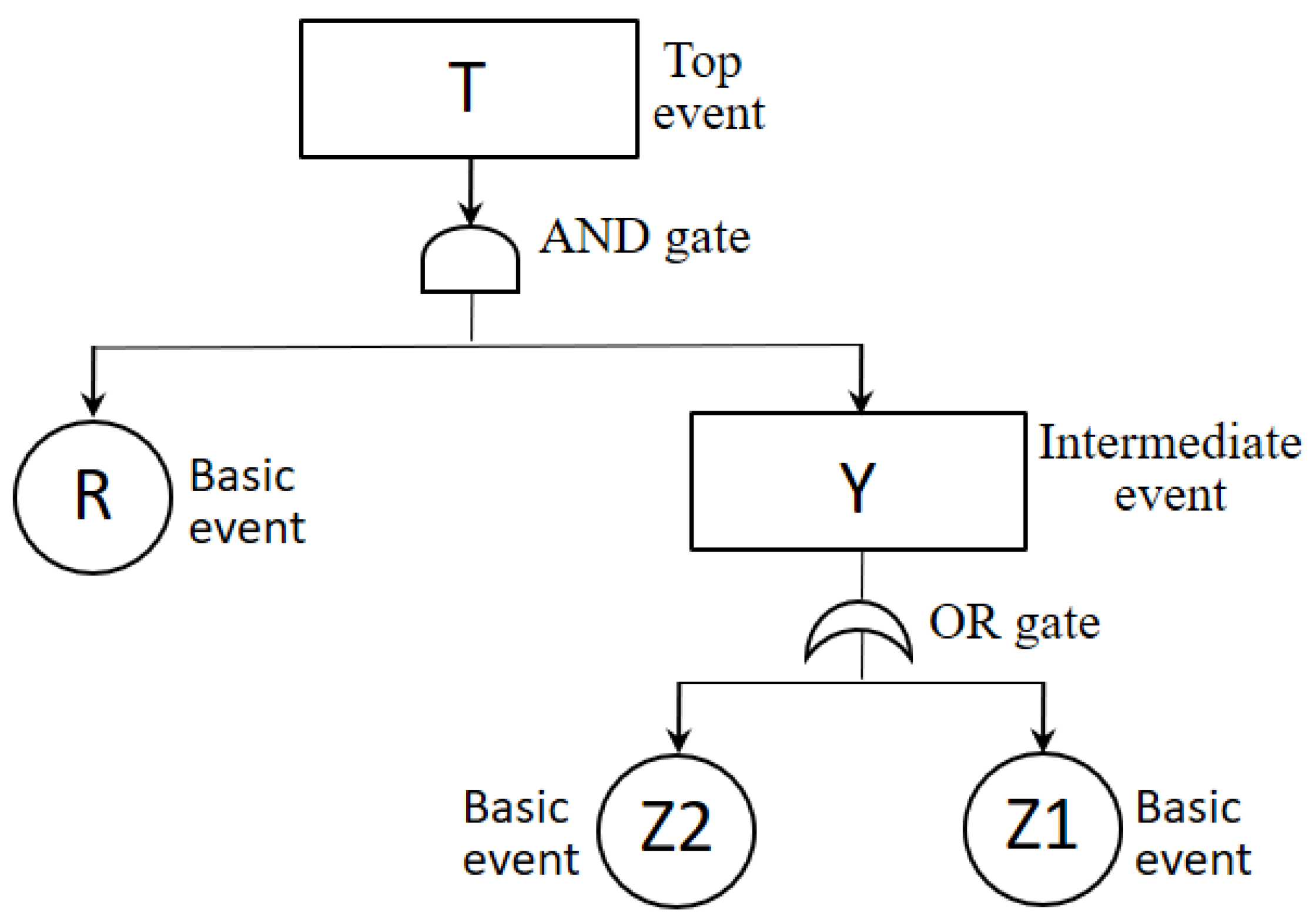

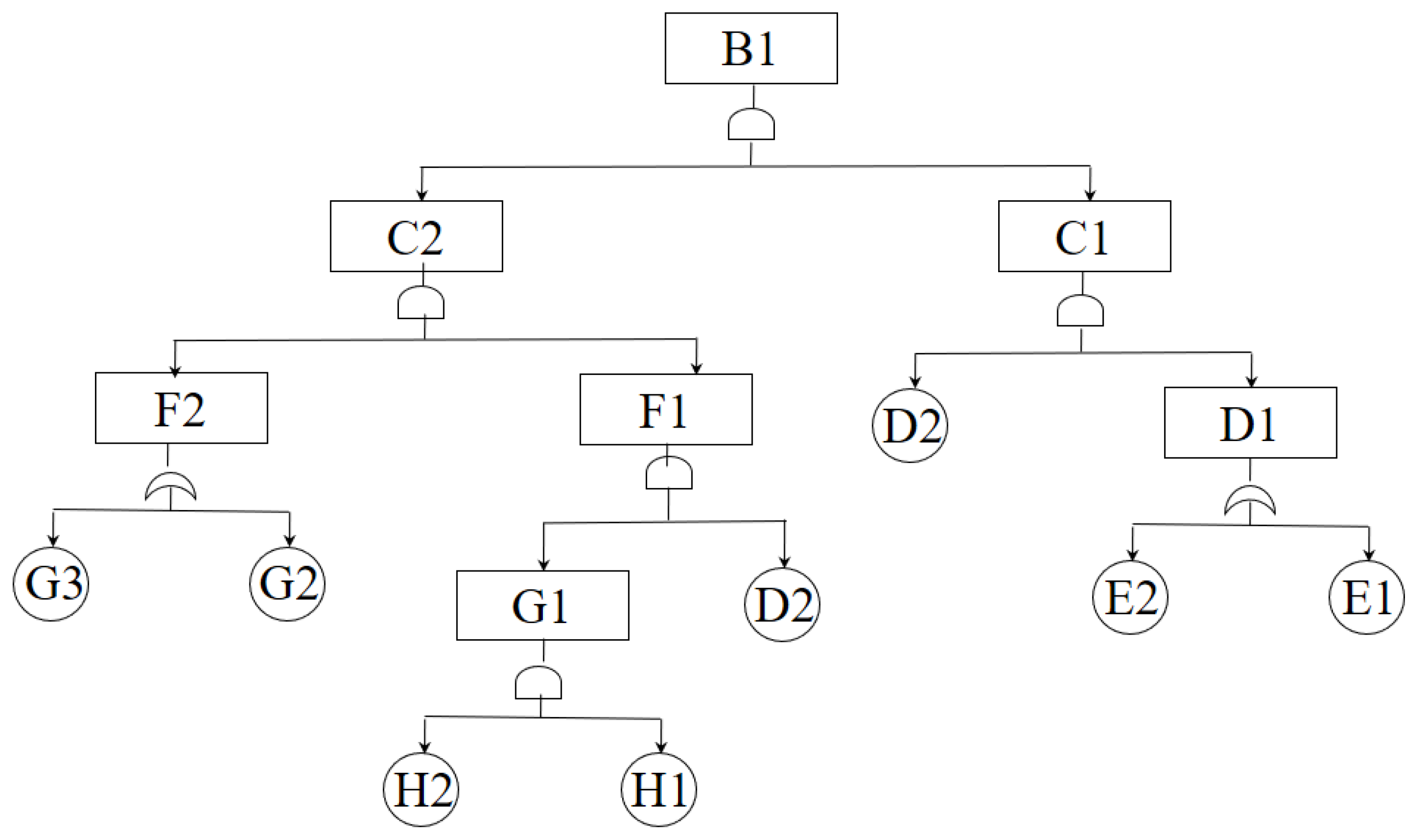

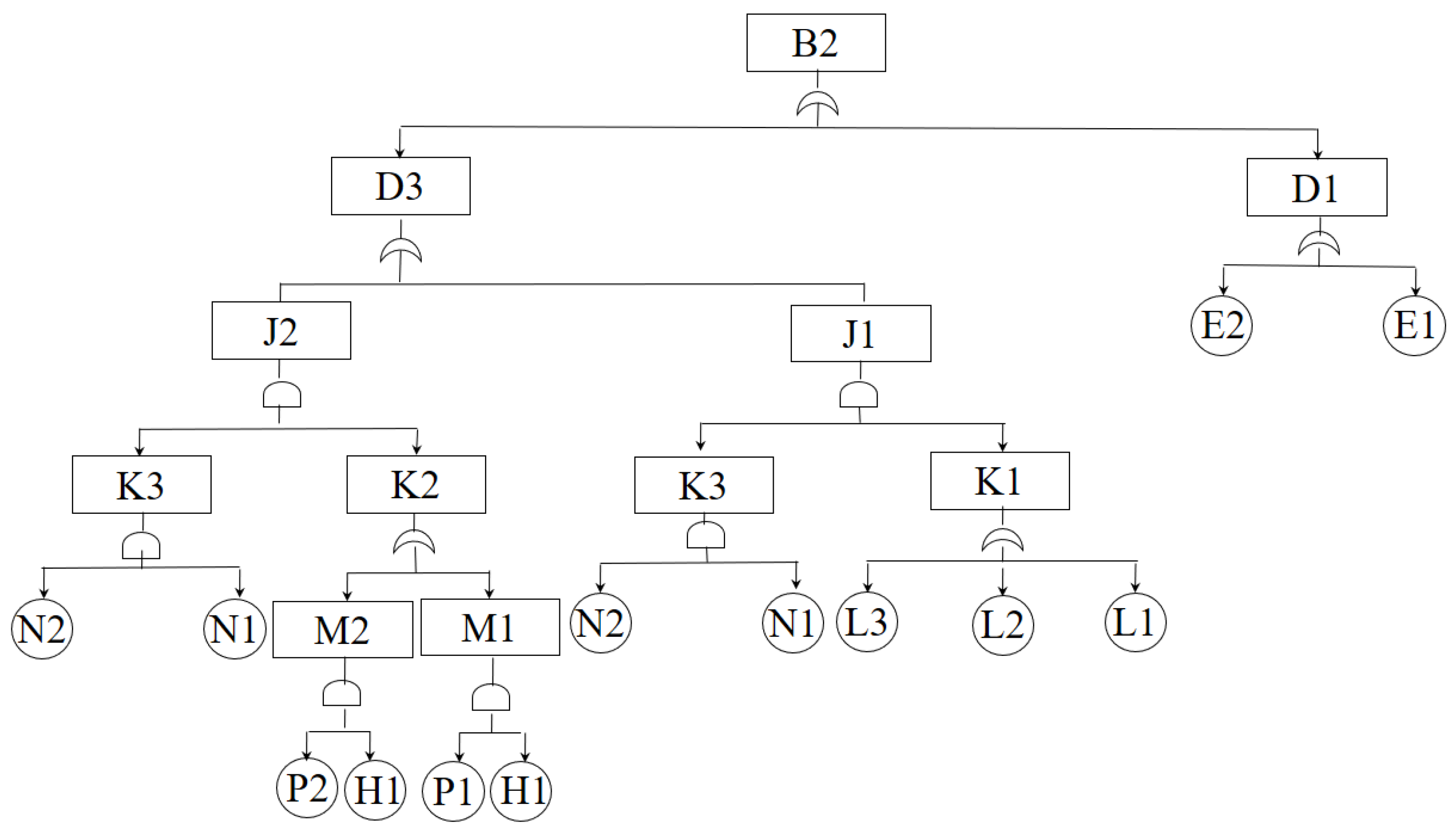

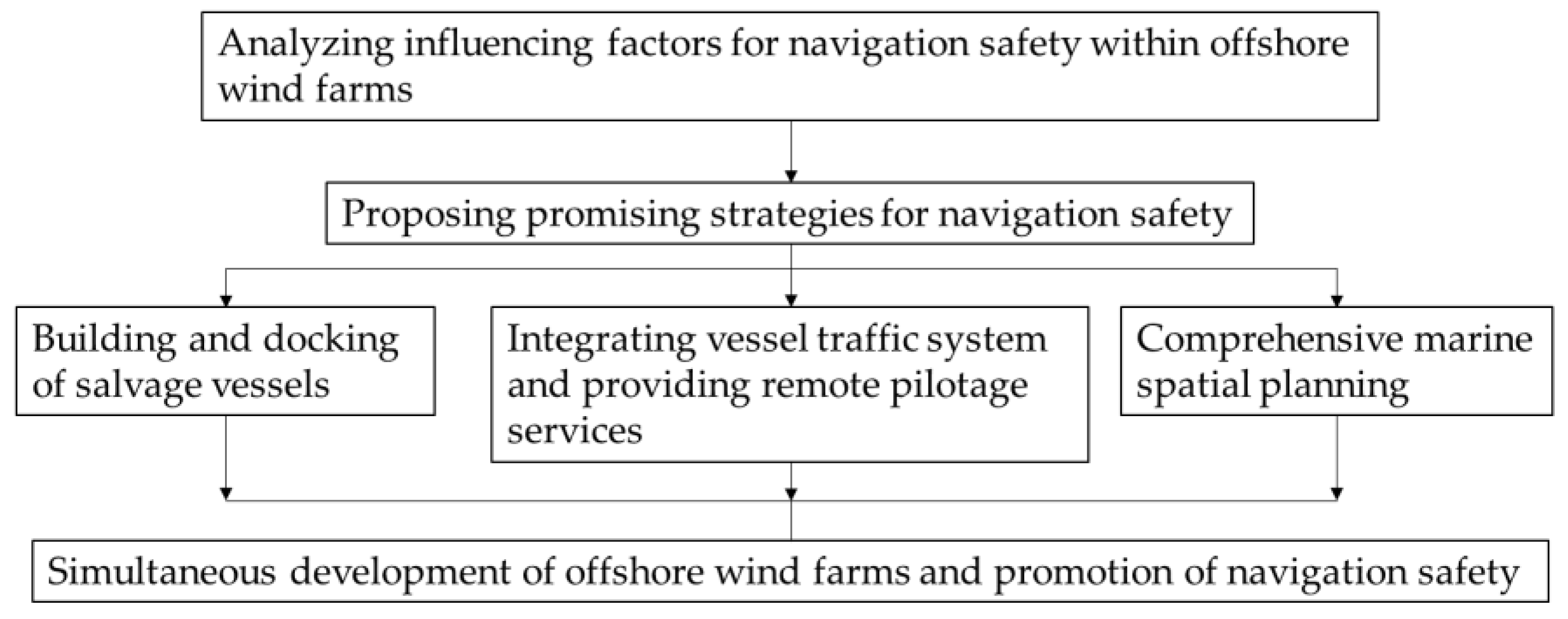

- Risk analysis in a navigation channel within offshore wind farms:Qualitative analysis of the navigation risk using the fault tree analysis method and Boolean algebra.

- Influencing factors for navigation safety within offshore wind farms:Discuss the influencing factors for navigation safety.

- Developing promising strategies to improve navigation safety in wind farms:Promising strategies for promoting navigation safety are developed.

- Conclusions:Summarize the main results derived from this study.

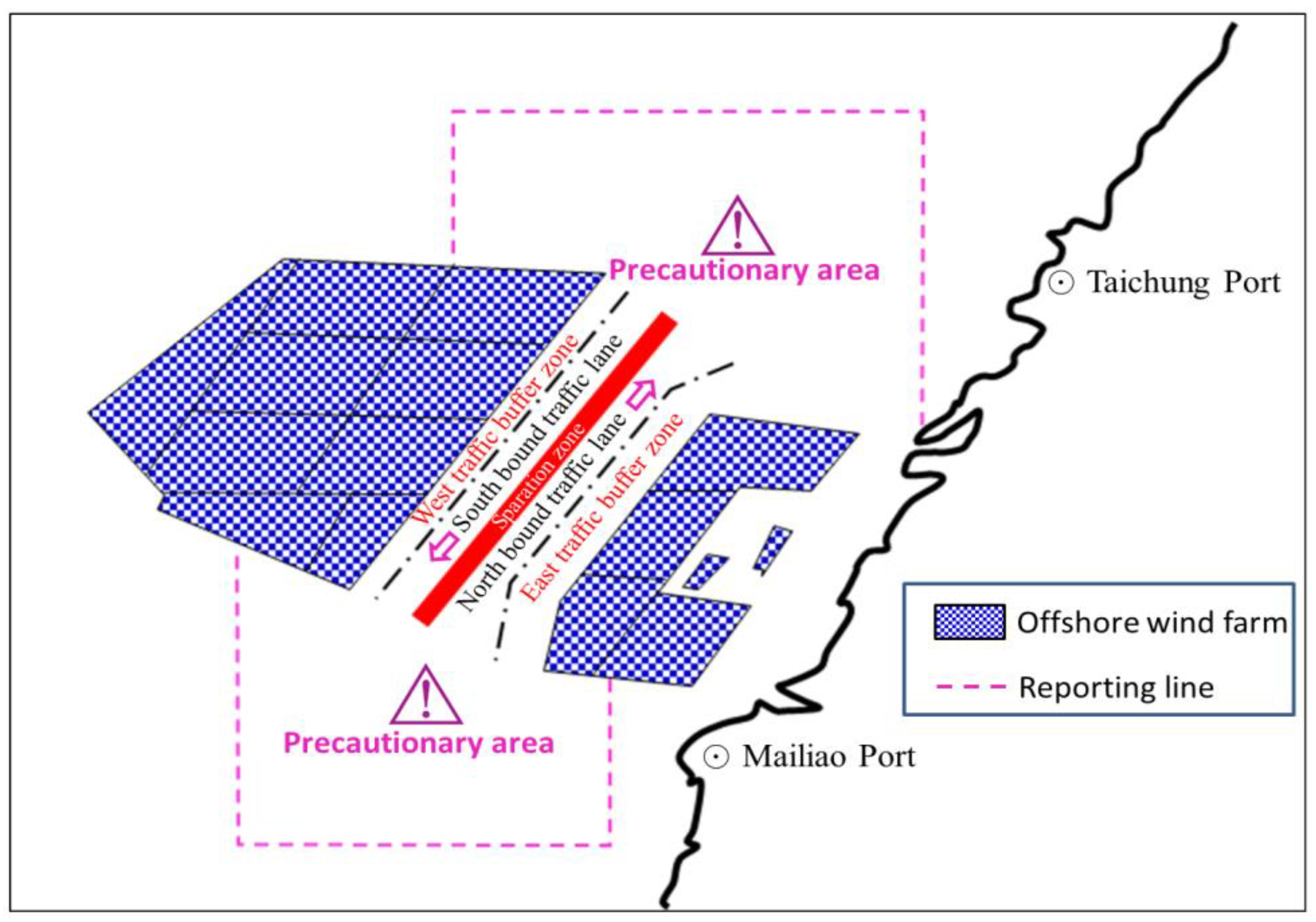

2. Establishment of Traffic Flow Management in Navigation Channel within Offshore Wind Farms

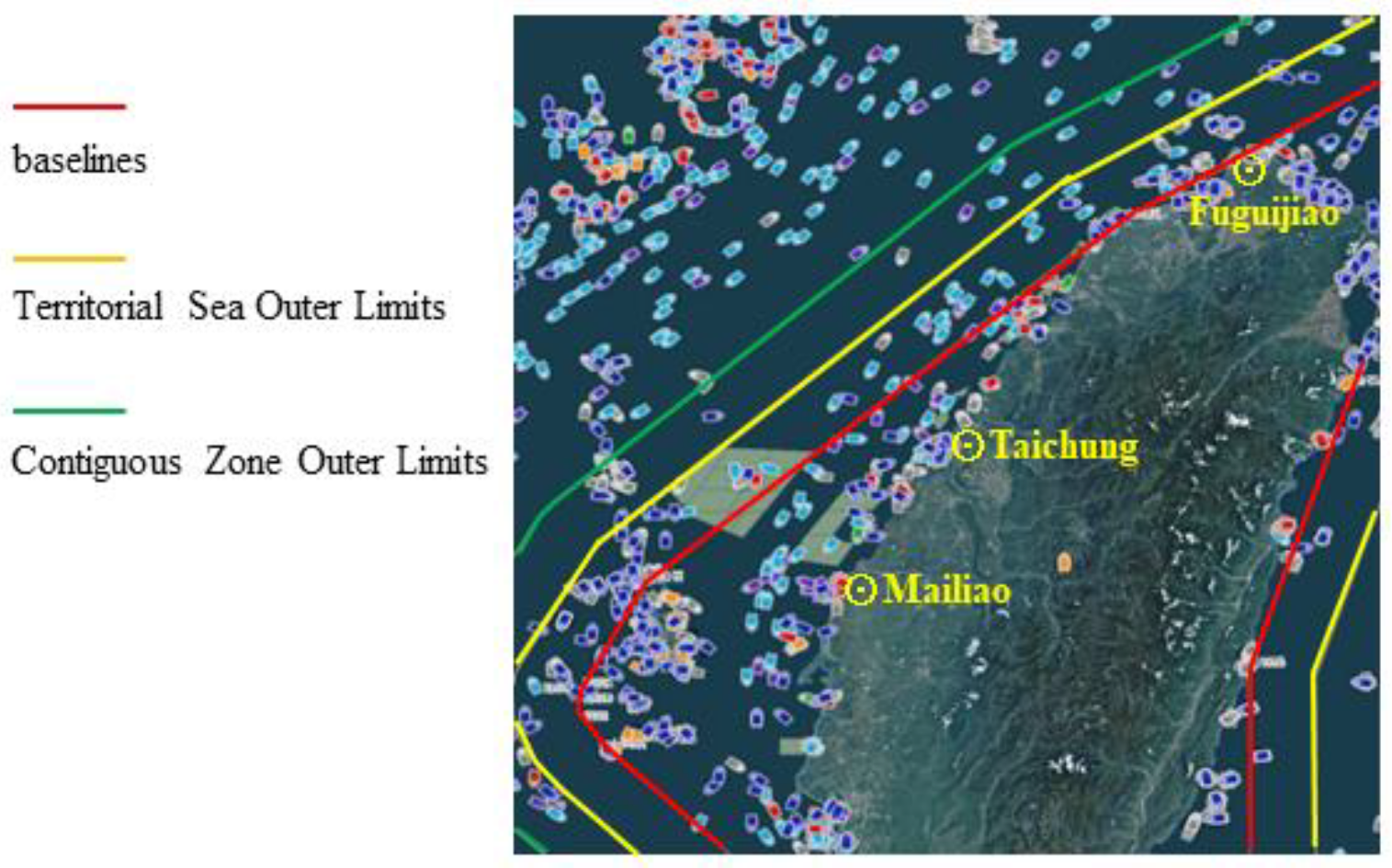

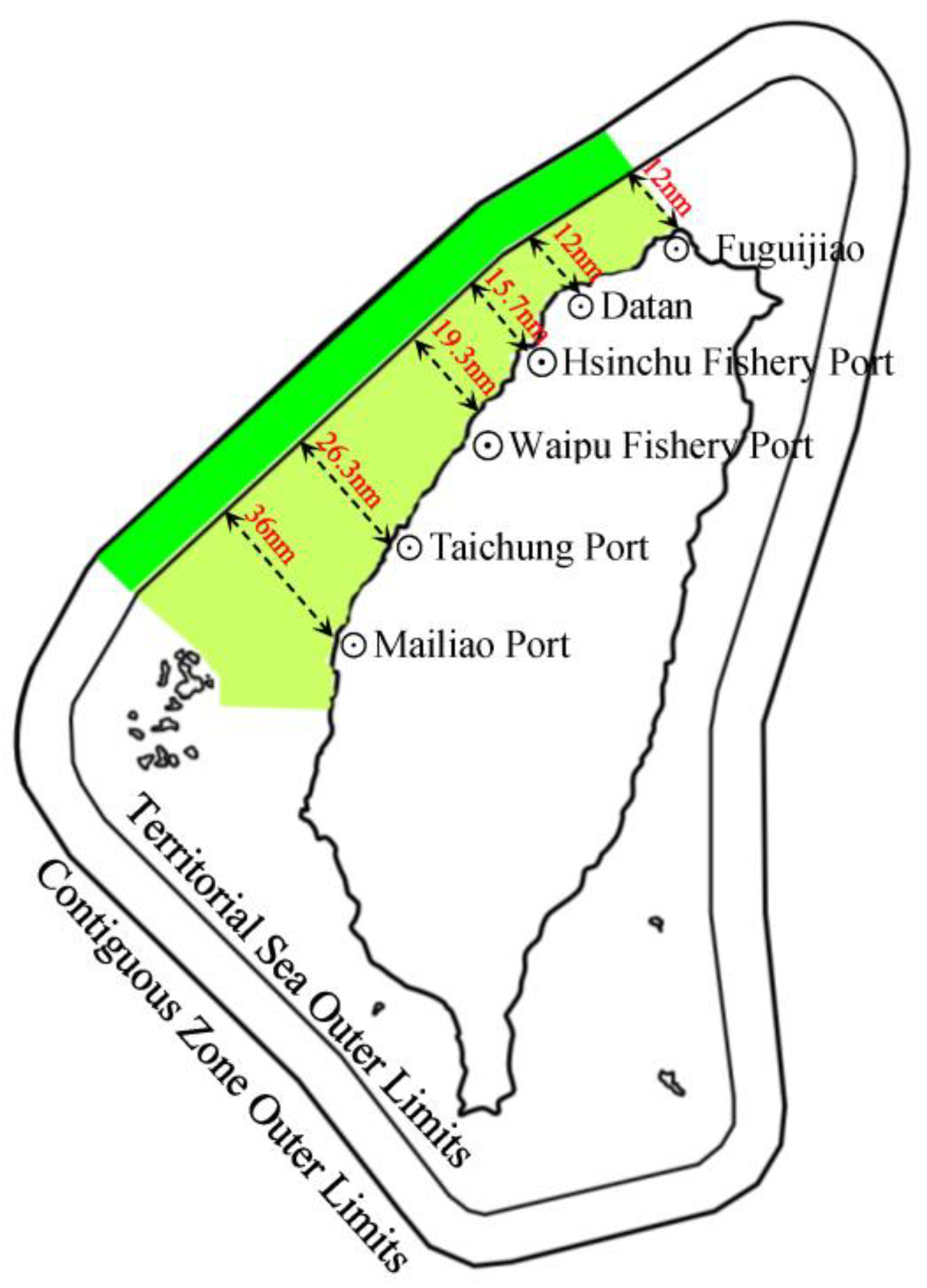

2.1. Planning of Navigation Channels within Offshore Wind Farms

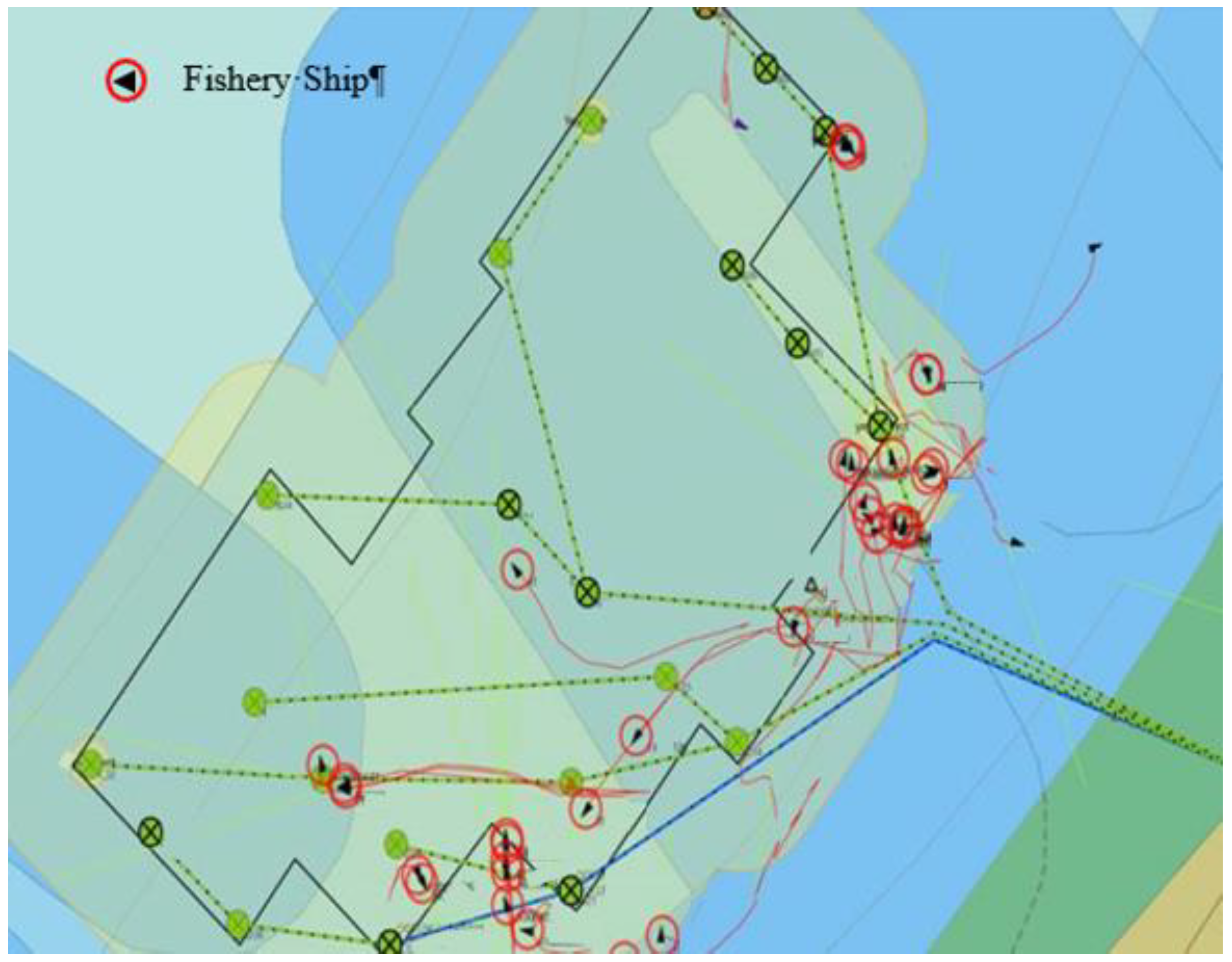

2.2. Controlling for Fishing Vessel within Offshore Wind Farms

3. Risk Analysis of Navigation Channel within Offshore Wind Farm

4. Influencing Factors for Navigation Safety within Offshore Wind Farms

4.1. Great Reduction of Navigation Space

4.1.1. Raising the Vessel Density Distribution in Navigation Channels within Offshore Wind Farms

4.1.2. Increasing Vessel Traffic Flow in Navigation Channels within Offshore Wind Farms

4.1.3. Large Space Reduction for Vessel Avoidance

4.2. Shadowing Effects on Navigation Channels

4.3. Increase of Collision Risks by Fishing Vessels Crossing Navigation Channels

4.4. Increasing the Colliding Probability of Breakdown Vessels with Wind Turbines

5. Developing Promising Strategies to Improve Navigation Safety in Wind Farms

5.1. Comprehensive Marine Spatial Planning for Offshore Wind Farms

5.2. Integrating Vessel Traffic System and Providing Remote Pilotage Services

5.3. Building and Docking of Salvage Vessels

5.4. Result Validation of the Fault Tree Analysis

- (1)

- When the ship’s machinery fails and the salvage ship is far away, the ship may collide with the wind turbine due to current drifting.

- (2)

- When the ship’s propeller is twisted and the salvage ship is far away, the ship may collide with the wind turbine due to drifting in the ocean.

- (3)

- When the ship’s propeller is twisted and no salvage ship is available, the ship may collide with the wind turbine due to current drifting.

- (1)

- When the ship’s machinery fails or the propeller is twisted, the ship may collide with the ship.

- (2)

- The shadowing effects of wind turbines, coupled with the unfit function of VTS and the lack of navigation aids, may cause ships to collide with ships.

- (3)

- Fishery ships frequently cross the navigation channel, and coupled with the unfit function of VTS and the lack of navigation aids, may cause ships to collide with ships.

- (4)

- Fishery ships cross the navigation channel between the turbines, and coupled with the unfit function of VTS and the lack of navigation aids, may cause ships to collide with ships.

- (5)

- The channel where there is a large flow of ships, coupled with the unfit function of VTS and the lack of navigation aids, may cause ships to collide with ships.

- (6)

- High ship density distribution in the channel, coupled with the unfit function of VTS and the lack of navigation aids, may cause ships to collide with ships.

5.5. Discussion

5.6. Policy Implication

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sovacool, B.K.; Enevoldsen, P.; Koch, C.; Barthelmie, R.J. Cost performance and risk in the construction of offshore and onshore wind farms. Wind Energy 2017, 20, 91–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garrido, M.V.; Mette, J.; Mache, S.; Harth, V.; Preisser, A.M. A cross-sectional survey of physical strains among offshore wind farm workers in the German exclusive economic zone. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e020157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Global Wind Energy Council (GWEC). Global Offshore Wind Report 2020. Available online: https://gwec.net/global-offshore-wind-report-2020/ (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- World Forum Offshore Wind (WFO). Global Offshore Wind Report 2020. Available online: https://wfo-global.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/WFO_Global-Offshore-Wind-Report-2020.pdf (accessed on 31 March 2021).

- Fraser, D. The Next Frontier of Wind Power. BBC News. 17 October 2019. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-scotland-scotland-business-50085071 (accessed on 23 March 2021).

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Chang, Y.C.; Liu, W.H.; Zhang, Y. Offshore wind farm in marine spatial planning and the stakeholders engagement: Opportunities and challenges for Taiwan. Ocean Coast Manag. 2017, 149, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, H.C.; You, W.L.; Huang, W.; Chung, C.C.; Tsai, A.Y.; Chen, T.Y.; Lan, K.W.; Gong, G.C. Variations of marine environment and primary production in the Taiwan strait. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.A.T.; Chou, S.Y. Impact of government subsidies on economic feasibility of offshore wind system: Implications for Taiwan energy policies. Appl. Energy 2018, 217, 336–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.J.; Wu, Y.T.; Hsu, H.Y.; Chu, C.R.; Liao, C.M. Assessment of wind characteristics and wind turbine characteristics in Taiwan. Renew. Energy 2003, 28, 851–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.C.; Lu, H.J.; Lin, J.R.; Sun, S.H.; Yen, K.W.; Chen, J.Y. Evaluating the fish aggregation effect of wind turbine facilities by using scientific echo sounder in Nanlong wind farm area, western Taiwan. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 2021, 29, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.H. Offshore wind policy. In Proceedings of the 2021 Asia Pacific Wind Energy Forum, Kaohsiung, Taiwan, 16–19 April 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 4C Offshore. Global Wind Speed Rankings. Available online: https://www.4coffshore.com/windfarms/windspeeds.asp (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- Young, I.; Zieger, S.; Babanin, A.V. Global trends in wind speed and wave height. Science 2011, 332, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaechi, C.V.; Wang, F.; Xiaonan, H.; Ye, J. Strength of submarine hoses in Chinese-lantern configuration from hydrodynamic loads on CALM buoy. Ocean Eng. 2019, 171, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amaechi, C.V.; Wang, F.; Ye, J. Understanding the fluid-structure interaction from wave diffraction forces on CALM buoys: Numerical and analytical solutions. Ships Offshore Struct. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Cai, H.; Liu, L.; Zhai, Z.; Amaechi, C.V.; Wang, Y.; Wan, L.; Yang, D.; Chen, X.; Ye, J. Microscale intrinsic properties of hybrid unidirectional/woven composite laminates: Part I experimental tests. Compos. Struct. 2020, 262, 113369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odijie, A.C.; Quayle, S.; Ye, J. Wave induced stress profile on a paired column semisubmersible hull formation for column reinforcement. Eng. Struct. 2017, 143, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, F.; Chen, J.; Gao, S.; Tang, K.; Meng, X. Development and sea trial of real-time offshore pipeline installation monitoring system. Ocean Eng. 2017, 146, 468–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Pan, W.; Zheng, X.; Zhou, S.; Tao, X. Effects of wave-current interaction on storm surge in the Taiwan Strait: Insights from Typhoon Morakot. Cont. Shelf Res. 2017, 146, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.Y.; Wu, Y.F.; Wu, Y.W.; Ndure, S. Fuzzy Bayesian schedule risk network for offshore wind turbine installation. Ocean Eng. 2019, 188, 106238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, S.M.; Pearre, N.S. Administrative arrangement for offshore wind power developments in Taiwan: Challenges and prospects. Energy Policy 2017, 109, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.J.; Hsu, C.P.; Liu, H.Y. Perceptions of offshore wind farms and community development: Case study of Fangyuan Township, Chunghua County, Taiwan. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 2019, 27, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, S.J.; Tseng, K.C.; Chang, S.M. Assessing navigational risk of offshore wind farm development—With and without ship’s routing. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2014—MTS/IEEE, Taipei, Taiwan, 7–10 April 2014; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Q.; Xin, X.; Liu, K.; Zhang, J. Risk analysis of ships & offshore wind turbines collision: Risk evaluation and case study. In Progress in Maritime Technology and Engineering, Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Maritime Technology and Engineering (MARTECH 2018), Lisbon, Portugal, 7–9 May 2018; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; pp. 484–490. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Q.; Liu, K.; Teixeira, A.; Soares, C.G. Assessment of the influence of offshore wind farms on ship traffic flow based on AIS data. J. Navig. 2020, 73, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maritime and Port Bureau (MPB). MOTC—In Line with the National Offshore Wind Farm Policy, “Changhua Wind Farm Channel” and Navigation Guide Announcement (in Chinese). Available online: https://www.motcmpb.gov.tw/Information/Detail/0735acea-9a27-481c-8226-8a34515a2612?SiteId=1&NodeId=15 (accessed on 26 May 2021).

- Ministry of Transportation and Communications (MOTC). Ministry of Transportation and Communications Notice Is Hereby Given, for the Announcement of “Changhua Wind Farm Channel”, The Executive Yuan Gazette Online. Available online: https://gazette.nat.gov.tw/egFront/detail.do?metaid=123538&log=detailLog (accessed on 26 April 2021).

- Ministry of Transportation and Communications (MOTC). Aids to Navigation Act, Laws and Regulations Database of the Republic of China. 2018. Available online: https://law.moj.gov.tw/LawClass/LawAll.aspx?pcode=K0070030 (accessed on 31 March 2021).

- Schupp, M.F.; Kafas, A.; Buck, B.H.; Krause, G.; Onyango, V.; Stelzenmüller, V.; Davies, I.; Scott, B.E. Fishing within offshore wind farms in the North Sea: Stakeholder perspectives for multi-use from Scotland and Germany. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 279, 111762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Interior (MOI). Maritime Information Integration Platform. Available online: https://ocean.moi.gov.tw/Map/ (accessed on 26 May 2021).

- Kang, J.; Sun, L.; Soares, C.G. Fault tree analysis of floating offshore wind turbines. Renew. Energy 2019, 133, 1455–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenhart, J.R.B. Newton da Costa on hypothetical models in logic and on the modal status of logical laws. Axiomathes 2021, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uğurlu, Ö.; Köse, E.; Yıldırım, U.; Yüksekyıldız, E. Marine accident analysis for collision and grounding in oil tanker using FTA method. Marit. Policy Manag. 2015, 42, 63–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Lu, J.M.; Jiang, J.L. Maritime accident risk estimation for sea lanes based on a dynamic Bayesian network. Marit. Policy Manag. 2020, 47, 649–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presencia, C.E.; Shafiee, M. Risk analysis of maintenance ship collisions with offshore wind turbines. Int. J. Sustain. Energy 2018, 37, 576–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdi, R.A.; Schröder-Hinrichs, J.U.; van Overloop, J.; Nilsson, H.; Pålsson, J. Improving the coexistence of offshore wind farms and shipping: An international comparison of navigational risk assessment processes. WMU J. Marit. Aff. 2018, 17, 397–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weng, J.; Liao, S.; Wu, B.; Yang, D. Exploring effects of ship traffic characteristics and environmental conditions on ship collision frequency. Marit. Policy Manag. 2020, 47, 523–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Ai, W. The research of navigational safety control in Taiwan strait. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Advances in Mechanical Engineering and Industrial Informatics (AMEII 2016), Hangzhou, China, 9–10 April 2016; pp. 954–957. [Google Scholar]

- Maritime and Coastguard Agency (MCA). Safety of Navigation: Offshore Renewable Energy Installations (OREIs)—Guidance on UK Navigational Practice, Safety and Emergency Response; UK, MGN 543 (M + F)—Marine Guidance Note; Maritime and Coastguard Agency (MCA): Southampton, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Global Wind Energy Council (GWEC). GWEC Launches the Global Wind Turbine Rotor Diameter Database as Part of Its Market Intelligence Platform. Available online: https://gwec.net/gwec-launches-the-global-wind-turbine-rotor-diameter-database-as-part-of-its-market-intelligence-platform/ (accessed on 12 May 2021).

- Sun, H.; Yang, H.H.; Sun, H.Y. Study on an innovative three-dimensional wind turbine wake model. Appl. Energy 2018, 226, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, D. Wind Turbine Spacing: How Far Apart Should They Be? Energy Follower. Available online: https://energyfollower.com/wind-turbine-spacing/#:~:text=Currently%2C%20wind%20turbines%20are%20spaced%20depending%20upon%20the,much%20more%20cost-effective.%20What%20is%20a%20Wind%20Turbine (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Li, Y.P.; Liu, Z.J.; Kai, J.S. Study on complexity model and clustering method of ship to ship encountering risk. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 2019, 27, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wang, F.; Xu, Z. Mapping global shipping density from AIS data. J. Navig. 2017, 70, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Transportation and Communications (MOTC). Data Query—Direct Cross-Strait Sea Transport and Mini-Three-Links Vessels. Available online: https://stat.motc.gov.tw/mocdb/stmain.jsp?sys=100&funid=e4301 (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- Lee, Y.J.; Su, N.J.; Lee, H.T.; Hsu, W.W.Y.; Liao, C.H. Application of métier-based approaches for spatial planning and management: A case study on a mixed trawl fishery in Taiwan. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.P.; Huang, H.W.; Lu, H.J. Fishermen’s perceptions of coastal fisheries management regulations: Key factors to rebuilding coastal fishery resources in Taiwan. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2019, 172, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Zong, L.; Yan, X.; Soares, C.G. Incorporating evidential reasoning and TOPSIS into group decision-making under uncertainty for handling ship without command. Ocean Eng. 2018, 164, 590–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wu, Z.; Zheng, Z. An improved danger sector model for identifying the collision risk of encountering ships. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purba, P.; Dinariyana, A.; Handani, D.; Rachman, A. Application of formal safety assessment for ship collision risk analysis in Surabaya west access channel. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Babylon, Iraq, 2020; p. 012034. [Google Scholar]

- Lihua, L.; Peng, Z.; Songtao, Z.; Jia, Y. Simulation analysis of fin stabilizers on turning circle control during ship turns. Ocean Eng. 2019, 173, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Maritime Organization (IMO). Standards for ship manoeuvrability. IMO resolution MSC 137(76). In Report of the Maritime Safety Committee on Its 76th Session-Annex 6; International Maritime Organization (IMO): London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- King, K.K.; Yasukawa, H.; Hirata, N.; Kose, K. Maneuvering simulations of pusher-barge systems. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 2008, 13, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altan, Y.C.; Otay, E.N. Spatial mapping of encounter probability in congested waterways using AIS. Ocean Eng. 2018, 164, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Maritime Organization (IMO). Convention on the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea, 1972 (COLREGs); Adopted on 20 October 1972; International Maritime Organization (IMO): London, UK, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Jenn, D.; Ton, C. Wind turbine radar cross section. Int. J. Antennas Propag. 2012, 2012, 252689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De la Vega, D.; Matthews, J.C.; Norin, L.; Angulo, I. Mitigation techniques to reduce the impact of wind turbines on radar services. Energies 2013, 6, 2859–2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Zhang, Y.; Palmer, R.; Bai, Y. Wind turbine radar signature characterization by laboratory measurements. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE RadarCon (RADAR), Kansas, MO, USA, 23–27 May 2011; pp. 162–166. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, A.; Chintala, V. Augmenting the signal processing–based mitigation techniques for removing wind turbine and radar interference. Wind Eng. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Y.; Daamen, W.; Ligteringen, H.; Hoogendoorn, S.P. Influence of external conditions and vessel encounters on vessel behavior in ports and waterways using Automatic identification system data. Ocean Eng. 2017, 131, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bowditch, N. The American Practical Navigator: An Epitome of Navigation; NIMA Publishing: Paradise Cay, CA, USA, 2019; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, T.H.; Chen, C.T.A.; Bai, Y.; He, X. Elevated primary productivity triggered by mixing in the quasi-cul-de-sac Taiwan strait during the NE monsoon. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maritime and Port Bureau (MPB). MOTC, Maritime Incidents Statistics. Available online: https://www.motcmpb.gov.tw/Information?siteId=1&nodeId=406 (accessed on 26 May 2021).

- Zaucha, J.; Gee, K. Maritime Spatial Planning: Past, Present, Future; Springer Nature: Basingstoke, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Stelzenmüller, V.; Gimpel, A.; Haslob, H.; Letschert, J.; Berkenhagen, J.; Brüning, S. Sustainable co-location solutions for offshore wind farms and fisheries need to account for socio-ecological trade-offs. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 776, 145918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Division for Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea, United Nations, United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. 1982. Available online: https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2021).

- Bernacki, D. Assessing the link between vessel size and maritime supply chain sustainable performance. Energies 2021, 14, 2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leivestad, H.H.; Schober, E. Politics of scale: Colossal containerships and the crisis in global shipping. Anthropol. Today 2021, 37, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, N.K.; Suh, S.C. Tendency toward mega containerships and the constraints of container terminals. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2019, 7, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Raoux, A.; Dambacher, J.M.; Pezy, J.P.; Mazé, C.; Dauvin, J.C.; Niquil, N. Assessing cumulative socio-ecological impacts of offshore wind farm development in the bay of seine (English Channel). Mar. Policy 2018, 89, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degraer, S.; Carey, D.A.; Coolen, J.W.; Hutchison, Z.L.; Kerckhof, F.; Rumes, B.; Vanaverbeke, J. Offshore wind farm artificial reefs affect ecosystem structure and functioning. Oceanography 2020, 33, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szłapczyński, R. Evolutionary sets of safe ship trajectories with speed reduction manoeuvres within traffic separation schemes. Polish Marit. Res. 2014, 1, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, J.; Zhou, F.; Li, Z.; Wang, M.; Liu, R.W. Dynamic ship domain models for capacity analysis of restricted water channels. J. Navig. 2016, 69, 481–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- International Association of Lighthouse Authorities/Association (IALA); Constitution of IALA; International Association of Lighthouse Authorities/Association. IALA BASIC Documents; 1.0; IALA: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- International Association of Lighthouse Authorities/Association (IALA). IALA Recommendation R0139 (O-139) on the Marking of Man-Made Offshore Structures, International Association of Lighthouse Authorities/Association; IALA: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, C.; Hsu, C.J.; Lin, J.Y.; Kuan, Y.K.; Yang, C.C.; Liu, J.H.; Yeh, J.H. Taiwan’s legal framework for marine pollution control and responses to marine oil spills and its implementation on TS Taipei cargo shipwreck salvage. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 136, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperstad, I.B.; Stålhane, M.; Dinwoodie, I.; Endrerud, O.-E.V.; Martin, R.; Warner, E. Testing the robustness of optimal access vessel fleet selection for operation and maintenance of offshore wind farms. Ocean Eng. 2017, 145, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Codes | Events | Codes | Events |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Collision | H2 | Turbines on both sides of the channel |

| B1 | Ship collided with turbines | J1 | Incomplete situational awareness |

| B2 | Ship and ship collision | J2 | Difficult to navigate |

| C! | Ship drifting | K1 | Disturbed lookout |

| C2 | Invalid salvage | K2 | Limited external environment |

| D1 | Ship out of control | K3 | Lack of assistance |

| D2 | Current effect | L1 | Turbines shadowing effects on channel |

| D3 | Ship operation failed | L2 | Fishery ships frequently cross the channel |

| E1 | Machine failure | L3 | Fishery ships crosses the channel between the turbines |

| E2 | Propeller twist | M1 | Heavy traffic |

| F1 | Insufficient salvage response time | M2 | Avoidable space is reduced |

| F2 | Lack of a proper salvage Ship | N1 | VTS is not functional |

| G1 | Ship too close to turbines | N2 | Defects in navigation aids |

| G2 | The salvage ships too far away | P1 | The channel has a large flow of ships. |

| G3 | No salvage ships | P2 | High ship density distribution |

| H1 | Navigable space is limited to the channel |

| Year | Collision | Aground | Fire | Machine Failure | Twisted Net | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 17 |

| 2015 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 16 |

| 2016 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 14 |

| 2017 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 1 | 17 |

| 2018 | 4 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 14 |

| 2019 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 15 |

| 2020 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 16 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tsai, Y.-M.; Lin, C.-Y. Investigation on Improving Strategies for Navigation Safety in the Offshore Wind Farm in Taiwan Strait. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 1448. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse9121448

Tsai Y-M, Lin C-Y. Investigation on Improving Strategies for Navigation Safety in the Offshore Wind Farm in Taiwan Strait. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2021; 9(12):1448. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse9121448

Chicago/Turabian StyleTsai, Yuh-Ming, and Cherng-Yuan Lin. 2021. "Investigation on Improving Strategies for Navigation Safety in the Offshore Wind Farm in Taiwan Strait" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 9, no. 12: 1448. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse9121448

APA StyleTsai, Y.-M., & Lin, C.-Y. (2021). Investigation on Improving Strategies for Navigation Safety in the Offshore Wind Farm in Taiwan Strait. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 9(12), 1448. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse9121448