Abstract

This review focuses on the most suitable form of hydrodynamic modeling for the next generation wave energy converter (WEC) design tools. To design and optimize a WEC, it is estimated that several million hours of operation must be simulated, perhaps one million hours of WEC simulation per year of the R&D program. This level of coverage is possible with linear potential flow (LPF) models, but the fidelity of the physics included is not adequate. Conversely, while Reynolds averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) type computational fluid dynamics (CFD) solvers provide a high fidelity representation of the physics, the increased computational burden of these models renders the required amount of simulations infeasible. To scope the fast, high fidelity options, the present literature review aims to focus on what CFD theories exist intermediate to LPF and RANS as well as other modeling options that are computationally fast while retaining higher fidelity than LPF.

1. Introduction

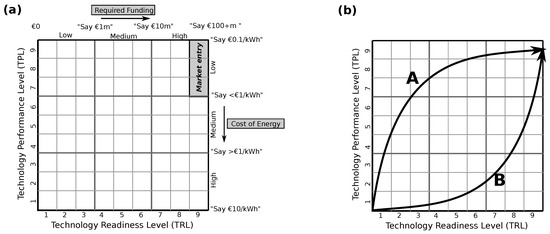

The development of commercial WEC technology is a complex and challenging endeavor. Weber et al. [1] outlined an improved WEC technology development methodology, by introducing a novel Technology Performance Level (TPL) metric to complement the more widely used Technology Readiness Level (TRL) metric (depicted in Figure 1a), and detail an overall R&D management philosophy that is tailored to the challenges of WEC development. Work following from [1] has focused on the development of the TPL metric [2], on a combination of the new approach with the discipline of Systems Engineering [3], on the application of the TRIZ Structured Innovation methodology [4], and on the risk analysis for WEC product development [5]. This paper explores one of the other needs identified in [1], namely the need for reliable, robust, and affordable simulations of WEC technology.

Figure 1.

(a) The Technology Readiness Level (TRL)—Technology Performance Level (TPL) matrix: wave energy converter (WEC) technology value map. (b) The TRL-TPL matrix, highlighting two different development trajectories to commercial viability: Path A represents the Performance before Readiness approach, and Path B is a more expensive trajectory (adapated from Weber et al. [1]).

1.1. R&D Context for WEC Simulation

The WEC R&D management philosophy described in [1], may be termed the Performance before Readiness philosophy. Pursuing a Performance before Readiness approach reduces the cost of product development and increases the probability of market entry. A central component of this approach is making performance improvements at early stages in the R&D program by maintaining the flexibility of concept and conducting evaluation and optimization of many alternative concepts, while still at low TRL (depicted by trajectory A in Figure 1b). Conversely, the alternative Readiness before Performance approach (depicted by trajectory B in Figure 1b), reduces the probability of market entry and, in wave energy, virtually guarantees bankruptcy [1].

Making performance improvements requires reliable and affordable performance estimates, which brings WEC simulation into the spotlight. It is uneconomical to obtain performance estimates, for a wide diversity of concepts at low TRL, using a program that relies exclusively on experimentally derived results. Software simulation is one of the key enabling technologies that will facilitate the Performance before Readiness approach.

1.2. Requirements of WEC Simulation

A particular need is a WEC simulation that is suitable for automatic optimization. Techno-Economic (combined engineering and financial) optimization, is specifically anticipated in [1], but any kind of WEC optimization, with or without financial objective functions, still requires a WEC simulation that is suitable for automatic optimization. To be suitable for automatic optimization, a simulation must satisfy the following requirements:

- (a)

- Fidelity requirement—be reliable for all possible trial vectors that an optimization algorithm might generate for evaluation,

- (b)

- Flexibility requirement—be general enough to be applicable to a wide variety of candidate WEC concepts, and

- (c)

- Computational requirement—be fast/affordable enough to allow sufficient generations or iterations to be completed in practical time scales on available and affordable hardware.

1.3. Objective of Scoping Study

Arguably none of the well established WEC simulation approaches satisfy all the requirements for an ideal simulation tool for WEC design. Most approaches to WEC simulation can be characterized by a position on a speed-fidelity spectrum. One extreme of the spectrum is high speed but low fidelity, while the opposite extreme of the spectrum is low speed but high fidelity. The two well-established approaches to WEC simulation occupy these opposite extremes:

- At the low-fidelity/high-speed end of the spectrum are methods based on LPF, including frequency-domain methods [6], Cummins equation time-domain methods [7], and extensions of Cummins methods, such as the Nonlinear Froude–Krylov (NLFK) approach (see Section 3.6.2).

- At the high-fidelity/low-speed end of the spectrum are approaches based on RANS CFD codes (see review in [8]). Schmitt et al. [9] present the challenges and advantages for the application of RANS-based methods in the design process of a WEC, concluding the major drawback is the significant computational power required.

Mature software packages, both commercial and open-source, based on the opposite extremes of the speed-fidelity spectrum are available and their properties are relatively well known. It is the contention of the authors that neither of these mature approaches satisfies the requirements for an ideal WEC simulation tool, the fast methods are not accurate or robust enough and the accurate methods are not fast or affordable enough. We propose that a specialist WEC simulation tool based on an intermediate CFD theory is needed. CFD Theories that are intermediate to LPF and RANS exist, but compared to LPF and RANS are relatively under-developed with few commercial or open-source software products available and knowledge of the properties of these approaches is often only available to the creators of research codes. In this paper, we set out to review the CFD theories and related methods that are intermediate to LPF and RANS with a view to identifying promising avenues for a specialist WEC simulation tool.

1.4. Previous Reviews

A very early comparison of numerical methods in free-surface hydrodynamics can be found in Yeung [10] from the Hydrodynamics of Ocean Wave-Energy Utilization Symposium in 1985. Nearly three decades later, in 2012, Li and Yu [11] reviewed the modeling methods available for point absorber type WECs. In the same year, Folley et al. [12] reviewed hydrodynamic modeling for WEC arrays, which were again later reviewed in DeChowdhury et al. [13]. Nonlinear hydrodynamic modeling of WECs is the focus of the reviews in Wolgamot and Fitzgerald [14] and Penalba et al. [15], whereas the reviews in Windt et al. [8] and Zullah et al. [16] specifically focus on RANS modeling of WECs. Zabala et al. [17] review integrated approaches to numerical and experimental testing, from full-scale prototype and physical wave tank (PWT) models to RANS and LPF simulations. Saincher and Banerjee [18] review the influence of wave breaking on WEC hydrodynamics. Whereas the reviews in Coe et al. [19,20] focus on the modeling methods for WEC survival in extreme seas. In addition, a good book detailing the current state-of-the-art in WEC hydrodynamic modeling was recently published in 2016 [21].

1.5. Outline

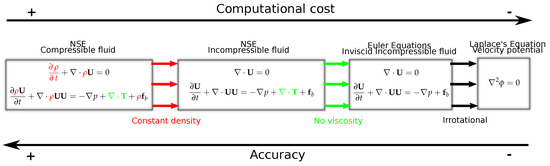

Mathematical modeling of nonlinear WEC hydrodynamics require a venture from physics to numerics. Increasing the computational efficiency can, therefore, be pursued through prudent selection of the relevant physical effects to be modeled, a parsimonious mathematical description of the selected effects and an efficient numerical scheme to solve the governing equations. Considering the physics, Section 2 presents the different types of nonlinear hydrodynamic effects a WEC may be subjected to and the conditions under which these effects are relevant. Next, turning to the mathematics, the governing system of equations for fluid dynamics, the Navier–Stokes equations (NSE) are introduced and their role in hydrodynamic modeling for WECs discussed. The spectrum of numerical schemes, with varying complexity and fidelity, utilized to solve the NSE are then presented to set the scene for the following sections, which collate and review the literature, laid out as follows:

- Section 3 reviews the CFD theories intermediate to RANS and LPF, which simplify the NSEs yet retain the potential to simulate nonlinear WEC hydrodynamics.

- Section 4 reviews the use of Domain Decomposition, which aims to reduce the required computational overhead of high fidelity CFD codes, by simulating the bulk of the computational domain with a lower fidelity model with fast computational speed, while only simulating the area in the immediate vicinity of the WEC with computationally expensive, higher fidelity models.

Section 6 discusses the main points gathered from Section 3, Section 4 and Section 5, in particular, those methods which have the potential of performing efficient simulations to aid in WEC design, and provides a tabulated comparison of the different methods reviewed. Conclusions are presented in Section 7.

2. Efficient Nonlinear Hydrodynamic Models for WECs

A good description of WEC hydrodynamics is given in Todalshaug [22], detailing the fundamental principles of wave absorption and hydrodynamic forces on bodies. The traditional modeling approach treats the hydrodynamic forces linearly (see Falnes [23] for an in-depth description), for time domain [7] and/or frequency domain [6] analyses of the WEC based on LPF. Correspondingly, this type of modeling approach leads to a linear relationship between the input wave and the output WEC motion. Thus, if the wave height is doubled, the resulting amplitude of WEC motion also doubles. However, in reality, this does not hold for a large portion of the simulations required for WEC design, due to nonlinear effects. Section 2.1 discusses the types of nonlinearities which can appear during WEC operation and Section 2.2 details the factors which influence the prevalence or absence of these nonlinearities in WECs. Modeling these nonlinearities requires a more thorough treatment of the NSE, without the full range of linearing assumptions inherent to LPF, as detailed in Section 2.3.

2.1. Hydrodynamic Nonlinearities—Types

There are three main physical effects, neglected in the linear formulation, which give rise to hydrodynamic nonlinearities: viscosity, nonlinear waves, and time-varying wetted body surface. The nonlinear viscous effects are omitted in the linearization of the equations, discussed in Section 3.1.1, whereas the effects of the nonlinear waves and time-varying wetted body surface are omitted in the linearization of the boundary conditions, as discussed in Section 3.1.2.

2.1.1. Viscosity

Viscosity gives rise to drag forces, resulting from pressure/form drag and skin friction drag. For WECs, pressure drag is the main contributor and skin friction is typically negligible [22]. Pressure drag is caused by flow separation and vortex shedding, whose force on the WEC is nonlinear, increasing quadratically with the relative WEC-water velocity.

In marine hydrodynamics, the relative importance of viscous forces increases as the size of the body decreases [24]. Therefore, in many offshore engineering applications, neglecting viscous effects to enable a linear formulation of hydrodynamics is a valid approximation, owing to the large size of the structures, such as ships and floating oil platforms. For WECs however, the characteristic lengths are generally much smaller and the role of viscosity can be important. WECs also differ from most offshore structures, in that they are designed to resonate with the input waves, whereby the large amplitude wave-driven motions result in increased relative WEC-water velocity.

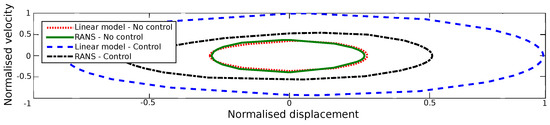

Neglecting viscosity in WEC analysis results in an underestimation of the hydrodynamic damping, leading to predictions of unrealistically large WEC motions and energy capture, especially around resonance [25] and when driven by an energy maximizing control system [26,27]. This is exemplified in Figure 2, from the case study in [26], showing the overestimation of the WEC motion predicted by a linear Cummins equation model, compared to a RANS simulation, when a control system uses the power take-off (PTO) to drive a heaving point absorber (HPA) into resonance with the input waves, contrasted against the case where no control is applied and the device is not in resonance.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the displacement-velocity operational space for a heavy point absorber (HPA) in a JONSWAP sea spectrum, with and without an energy maximizing controller, predicted using a linear Cummins equation model and a Reynolds averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) simulation, from the case study presented in Davidson et al. [26].

2.1.2. Nonlinear Ocean Waves

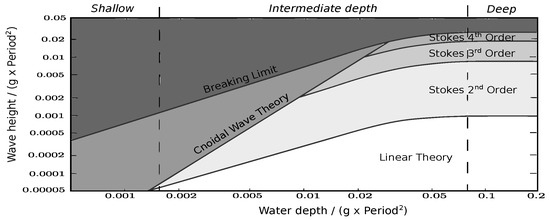

Figure 3 shows that linear theory is only valid in deep and intermediate water depths for small amplitude waves. As the relative water depth decreases and/or the relative wave height increases (relative with respect to the wave length), then the linear theory breaks down and the wave becomes nonlinear. Wave breaking, as an extreme case, is a very nonlinear process (see review in Saincher and Banerjee [18]). The difference in loads calculated including the wave nonlinearity versus the loads calculated by purely linear models is important for load design and survival and is examined by Viuff et al. [28] for the case of the Wavestar WEC. Additionally, the wave nonlinearity affects the hydrodynamic efficiency of a WEC. For example, Ning et al. [29] show that the hydrodynamic efficiency of a fixed oscillating water column (OWC) attains a maximum value at a critical wave slope and decreases when the wave nonlinearity becomes either stronger or weaker. Giorgi and Ringwood [30] examine the effect of wave nonlinearity on the calculation of Froude–Krylov (FK) forces on an HPA and an oscillating surge converter (OSC) for the different sea states occurring at the European Marine Energy Centre, contrasting the degree of error with the likelihood of the sea state occurrence. Further discussion on wave nonlinearity is given in Section 6.3.

Figure 3.

The validity limits of different wave theories dependent on the water depth, the wave height and the wave period. The region in which linear theory is valid is shown in white (Adapted from [31]).

2.1.3. Time-Varying Wetted Body Surface

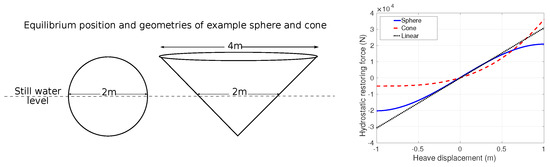

The hydrodynamic force on a WEC results from the integral of the fluid pressure over the wetted-surface area. For a linear model, the wetted surface area is assumed constant, calculated at the equilibrium position, and the forces linearized around that point, such that a doubling in wave elevation, body displacement, or velocity, equals a doubling in the wave excitation force, hydrostatic restoring force or radiation force, respectively. This is illustrated in Figure 4, for the hydrostatic restoring force on a sphere and a cone, as a function of the heave displacement, showing the actual nonlinear result due to the time-varying wetted body surface and the linearized version. The time-varying wetted body surface, and resulting time-varying system parameters, can lead to phenomena such as parametric resonance [32,33,34,35,36]. In some cases, the geometry of the WEC may also change with time. Examples of these are flexible structures such as the Bombora, the Anaconda, and the WECs investigated in [37,38], or WECs with movable control surfaces such as in Diamond et al. [39] and Tom et al. [40].

Figure 4.

Hydrostatic restoring force for a sphere and a cone.

2.2. Hydrodynamic Nonlinearities—Dependences

The influence of the different types of hydrodynamic nonlinearities, detailed in Section 2.1, varies on a case by case basis, dependent on the following:

2.2.1. Device Dependence

Hydrodynamic nonlinearities are device-dependent. For example, Folley et al. [41] contrast the hydrodynamics of heaving and surging devices and conclude that the hydrodynamics of the two are very different and should be considered distinctly. Similarly, Giorgi and Ringwood [42] compare the relative importance of different hydrodynamic forces for HPAs and OSCs, and show that HPAs are predominately affected by NLFK forces, whereas, for OSCs, the diffraction and radiation effects are the most important. For the case of OWCs, the review in [14] identifies that the effects of viscosity appear to be significantly larger than nonlinearities associated with the waves or time-varying wetted surface, particularly at resonance. [15] reviews the relevant importance of nonlinear hydrodynamic effects in OWCs, HPAs, OSCs, and oscillating pitch converters, highlighting differences between each.

2.2.2. Sea State Dependence

The hydrodynamic nonlinearities can depend on the sea states. Sea states with peak frequencies aligned with the WEC natural frequency will result in large amplitude, resonant WEC motion, enhancing both viscous and time-varying wetted body nonlinear effects. For example, Yu and Li [25] show large discrepancies between linear models and RANS simulations, for input waves corresponding to the resonance frequency of the WEC, but a closer agreement for other frequencies. Additionally, sea states with larger wave heights are more likely to have waves that fall outside of the linear region in Figure 3. Wang et al. [43] investigate the effect of the wave nonlinearity and viscosity on the performance of an OWC, by comparing the linear and nonlinear numerical results and show the changing relative importance of these nonlinear effects as the wave amplitude increases. Furthermore, the wave nonlinearity could also depend on the tide, with shallower water depths at low tides increasing the likelihood of waves falling outside of the linear region in Figure 3.

2.2.3. Control Dependence

The relevance of different nonlinear effects can also depend on the control applied to the device [26,27]. For example, Giorgi and Ringwood [27] examine hydrodynamic nonlinearities in controlled versus uncontrolled conditions for a spherical HPA. The accuracy and computation time of eight different partially nonlinear models are compared against RANS simulations, for cases with and without latching control in regular waves. The results show that when no latching is applied, nonlinearities were not significant, however, with control, NLFK and viscous drag forces become relevant. Similar results are shown in Davidson et al. [26] for an HPA in a JONSWAP spectrum, with and without a controller applying reactive power through the PTO.

2.2.4. Scale Dependence

Hydrodynamic nonlinearities are also scale-dependent. This can be important to consider given that the assessment hydrodynamic model success is often with respect to physical models at the laboratory scale. Therefore, it is also important to understand the effects of scaling on the relative importance of nonlinear hydrodynamic forces, as discussed in Fitzgerald [44]. For example, this point is examined in Schmitt and Elsaser [45], considering the applicability of Froude scaling from PWT to full-scale OSCs using both tank tests and RANS simulations. The effect of scaling PWT results for a moored HPA, from 1:10 to full scale, is investigated in Windt et al. [46], through the use of upscaling. In the review De Chowdhury et al. [13], specific emphasis is paid on understanding how the modeling and scaled experiments are likely to be complementary to each other. See Palm et al. [47] also in Section 3.2.

2.3. The Navier–Stokes Equations

Accurately modeling the nonlinear wave-structure interaction (WSI), requires a thorough treatment of the hydrodynamic interaction between the WEC and the fluid, which can be obtained via an appropriate application of the NSE. The NSE are a set of partial differential equations, describing the dynamics of fluids, through the conservation of mass and momentum:

where denotes the three-dimensional (3D) spatial coordinate, t the time, the fluid velocity, p the fluid pressure, the fluid density, the stress tensor, and external forces, such as gravity.

2.3.1. Solving

This first thing to note when solving the NSE is that there are four equations (the momentum equation consists of a separate equation for each of the three spatial directions), with five unknowns (pressure, density and the three velocity components). Therefore, an additional equation is required to enable closure. To achieve this, the conservation of total energy is used to yield “the energy equation”, which introduces a sixth unknown (temperature), and then an “equation of state” is used to give six equations with six unknowns (see Ferziger and Peric [48] for more details).

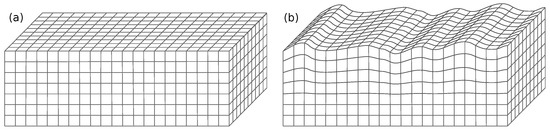

In general, the NSE have no known analytical solution, however, they may be treated numerically to obtain a solution. To solve the NSE, the continuous partial differential equations are discretized into a system of linear algebraic equations, which can then be solved by computer. That is, the continuum is broken up into finite temporal and spatial portions to transform a calculus problem into an algebraic problem. The problem can be discretized temporally using timesteps. Spatially, a number of different methods are available for the discretization:

- Mesh: A common approach, which is the main focus of the models reviewed in Section 3, discretizes the domain into nodes/cells.

- Particles: Discretizes the domain into lagrangian particles, via methods such as smoothed particle hydrodynamics (SPH) (discussed in Section 4.4).

- Particle distribution field: Discretizes the domain into a field giving a statistical representation of the particle distribution using methods such as Lattice Boltzman (LB) (discussed in Section 4.5).

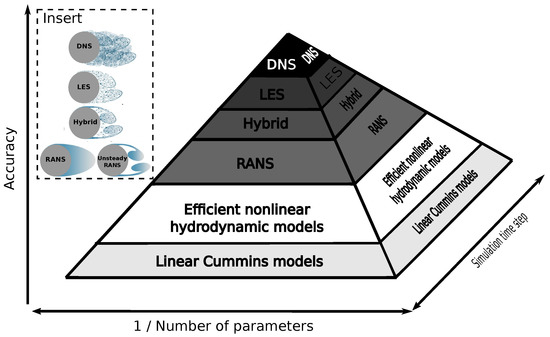

The pyramid in Figure 5 depicts the increase in accuracy versus the spatial and temporal discretizations, represented by the number of model parameters and the simulation time step, respectively. The higher up the pyramid the more accurate the solution (probably on a log-scale for WEC simulations) and the smaller the cross-sectional area of the pyramid, at a given height, the greater the computationally expense (probably on an exponential scale for WEC simulations).

Figure 5.

Schematic comparison of the accuracy versus computational requirements for solving the NSE. The more parameters and the smaller the timestep, thus the smaller the cross-sectional area of the pyramid at a given height, the greater the computational requirements. Here the vertical scale is likely logarithmic, the horizontal scales exponential and the cut-off positions between methods are not exact (Image inspired from [49,50]). The white region, “Efficient nonlinear hydrodynamic models,” represents the focus of the scoping study. (Insert: Example simulation resolution from the different methods, for airflow past a dimpled sphere, adapted from [51]).

2.3.2. Methods

At the top of the pyramid in Figure 5, the most accurate and computationally expensive way to solve the NSE is through direct numerical simulation (DNS), where all dynamics generated from the NSE are simulated on all spatial and time scales. This requires such a high spatial and temporal resolution, that the enormous number of model parameters and the minuscule simulation time steps prohibit DNS from being applied to WECs. To overcome this, large-eddy simulation (LES) and RANS methods model some of the physics rather than directly resolving the smallest scale phenomena.

For LES, the large scale turbulent structures are directly resolved and the turbulence on the sub-grid scale is modeled, which is still very computationally expensive, and has therefore rarely been applied to WEC applications (examples of LES applied to WECs can be seen in [52,53,54]). The RANS method does not attempt to directly resolve any of the turbulent structures, thus larger mesh cells and time steps are possible, which significantly reduces the computational requirements of this method compared to DNS and LES. RANS modeling is, therefore, becoming more computationally accessible (in line with the increased availability of low cost— high-performance computers) and is growing in popularity, with a recent review collating over 200 publications that apply RANS modeling for WECs [8]. However, as noted in Section 1.1, RANS is still too computationally expensive to simulate multiple WEC design iterations across multiple sea states.

At the bottom of the pyramid are linear hydrodynamic models based on the Cummins equation [55]. For these linear Cummins models, the simulation time step can be equal to the sampling of a sea state (approx. 30 mins) using frequency domain analysis [7] and the number of model parameters on the order of the number of frequency components considered. The white region on the pyramid, between RANS and the linear Cummins models, is the focus of Section 3, where an efficient nonlinear hydrodynamic modeling methodology, with sufficiently high accuracy and low computational cost, is sought by simplifying the Navier–Stokes solutions.

2.3.3. A Note on Turbulence

The Insert in Figure 5 shows an example of the airflow past a dimpled sphere from [51]. This example was taken from another field since such a figure does not exist for WECs, due to the challenging nature of turbulence modeling for WECs: (1) It is a multiphase problem, consisting of both air and water phases, with a discontinuity of physics at the free surface interface. The difficulties in applying turbulence models to two-phase fluids are recently addressed in [56,57]. (2) It is a transient problem, where both the WEC body and the surrounding flow field are constantly oscillating. This raises questions of whether the boundary layer has time to fully develop, and also means that the yPlus value is constantly changing and frequently equals zero. Conversely, the simulations depicted from [51], the input velocity is constant and the body is stationary relative to the surrounding flow-field.

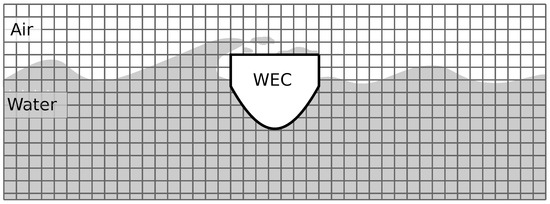

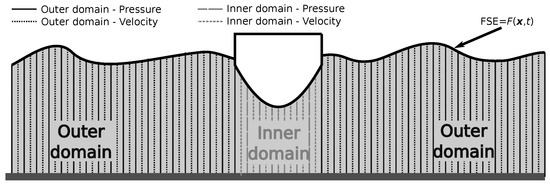

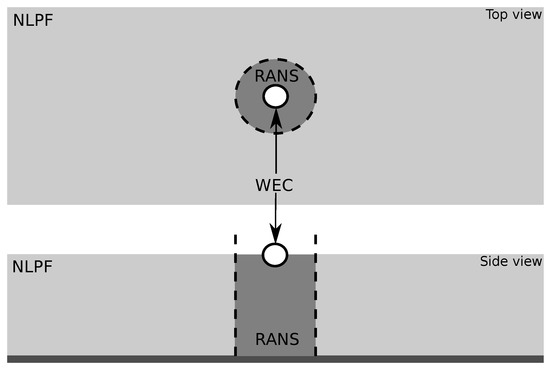

4. Domain Decomposition Methods

To reduce the overall computational burden of high fidelity methods, domain decomposition methods seek to decompose the entire problem into subdomains and apply different levels of model fidelity to the various subdomains. Domain decomposition allows lower-fidelity models to be used in the bulk of the domain to decrease the computational load, which are then coupled to more computationally heavy models in the immediate vicinity of the WEC, for high fidelity capturing of the nonlinear WSI. An example of this is shown in Figure 11, where the incident wave field is modeled using an NLPF model and the wave-WEC interaction is modeled using RANS.

Figure 11.

Schematic of domain decomposition using nonlinear potential flow (NLPF) in the far-field and Reynolds averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) in the near field.

Although relatively new to wave energy, these methods were introduced to shipping more than two decades ago [226], after being first utilized in aerodynamics [227]. Considering WEC analysis, an early domain decomposition strategy is presented in Clement et al. [228,229], where the outside of an OWC is modeled using a frequency domain (FD) model and the inner chamber is modeled using a time-domain (TD) BEM model to account for nonlinearities in the OWC. Other types of model-to-model coupling have been reported and are reviewed in the following Sections and collated in Table 6.

Table 6.

Review of publications utilizing Domain Decomposition for WEC simulation.

4.1. Wave Model to Potential Flow

Bingham [248] presents an early implementation of domain decomposition, to model the motion of a moored ship in a harbor, stating “A combination of established methods is used in an attempt to account for the most important physical processes involved in this complicated problem, while keeping the computational burden modest.” A Boussinesq-type model is used for the wave propagation from deep water into the harbor and then PF is utilized within the harbor, for both the wave transformation over the bathymetry and the WSI with the ship. In Ducrozet et al. [131] a decomposition approach is used for efficient WSI, with the intention of enhancing the efficiency of the NLPF model, OceanWave3D. The domain is decomposed by splitting all solution variables into the incident and scattered fields, where incident wave field is given explicitly by a dedicated wave model (which is assumed to be accurate and very fast compared to the overall solution), while the scattered part is solved by OceanWave3D.

Considering WECs, this approach has been applied to a number of cases involving WEC arrays. Charrayre et al. [230] first applied this approach to study the interactions of waves with an array in varying bathymetry, applying a BEM model to solve the radiation-diffraction problem locally around each WEC, combined with a model based on the mild slope equation at the scale of the array. Belibassakis et al. [233,234] present a similar approach considering a WEC array in varying bathymetry, motivated by the fact that wave-seabed-multiple body interactions could have a significant effect but could not be resolved within their wave propagation model. Tomey-Bozo et al. [235,236] use a depth-averaged mild-slope wave propagation model (MILDwave) for the far-field and resolve the near field effects using an LPF solver (NEMOH), to study the wake effects behind an array of OSCs.

Considering very large domains, spanning entire WEC farms comprising numerous WEC arrays, recent work from Ghent university [237,238,239,240,241,249,250] also couple MILDwave and NEMOH. In addition, Verbrugghe et al. [250] compare using the NLPF solver OceanWave3D to model the incident wave field against MILDwave and finds relative errors of less than 5%. The utility of the method is demonstrated in Balitsky et al. [238,249] where it is used to assess the impact of power production of WEC array separation distance in a wave farm, and in Fernandez et al. [239] where it is used to compare the far-field effects of arrays of HPAs and OSCs. The approach is validated against experimental data in Fernandez et al. [240], considering an array of 9 HPAs over varying bathymetry, showing good agreement with small differences between 3–11%. In Fernandez et al. [241] a very similar validation is shown, in this case considering a single HPA, an array of 5 HPAs and an array of 9 HPAs, with differences between the experiments and simulation of less than 10% for all cases.

4.2. Wave Model to RANS

The main disadvantage of the wave model to PF domain decomposition presented in the previous section is the use of linear hydrodynamics to model the WEC dynamics. Indeed, when validating the model against experiments Bingham [248] noted: “Some tuning, in the form of empirically obtained damping coefficients, is, however, necessary in order to get a reasonable prediction of the response amplitudes near resonance, when the linear hydrodynamic damping is very small.” To overcome this drawback, the method in this section considers wave model to RANS domain decomposition.

To accurately investigate wave loads on offshore wind turbine foundations, Christensen et al. [251] utilize a Boussinesq model for the outer wave field (DHI ‘Mike21 BW’ [252]), while the inner region surrounding the structure is modeled with a RANS solver. Similarly, Wei et al. [231] couple a Boussinesq model (FUNWAVE) with a RANS model (ANSYS FLUENT), due to large computation times and significant reflections from the boundaries observed in their previous RANS studies of OSCs. The coupled model takes advantage of the Boussinesq wave model simulating the wave propagation effectively and eliminating the reflection problem, and the RANS model providing the local flow details comprehensively. The model is validated by comparing the results against the pure RANS model and PWT experiments. The computational cost of the coupled Boussinesq-RANS model is reported to be about 40% less than the pure RANS model.

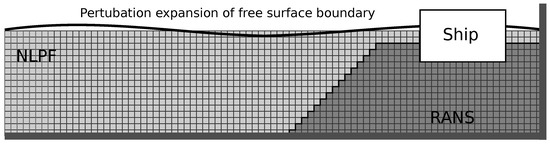

4.3. Potential Flow to RANS

The utility of the PF to RANS domain decomposition stems from the fact that neither solver is completely well suited to study WSI. PF cannot take into account viscous effects, which play an important role close to the WEC. Whereas, RANS cannot efficiently simulate wave propagation, due to the requirement of a very fine mesh to avoid inherent numerical damping, which significantly increases the computational expense. Therefore, coupling PF in the far-field and the RANS in the near-field seeks to overcome these drawbacks. A number of different methods have been implemented to achieve this and reviewed separately in the following subsections.

4.3.1. SWENSE

Early adoption of this decomposition, to allow viscous flow simulation of ships maneuvering in waves, is the SWENSE (Spectral Wave Explicit Navier–Stokes Equations) approach which has been developed since 2003 at ECN [130,253,254,255,256,257,258,259]. The SWENSE formulation modifies the initial problem to solve the diffracted flow only. It consists of splitting all unknowns of the problem (velocities, pressure and free-surface elevation) into the sum of an incident term and a diffracted term. The incident terms are described explicitly using a spectral NLPF model. Thus only the part of the grid in the vicinity of the structure needs to be refined. Far from the body, a stretched grid allows efficient damping of the diffracted flow. The incident wave terms are then introduced explicitly in a RANS solver whose equations have been modified by decomposing each physical variable in the sum of an incident variable and a diffracted one. The diffracted field is the only unknown solved by the modified RANS code. Originally the SWENSE method was developed for single-phase RANS solvers, however recently it has been extended to two-phase RANS solvers within the OpenFOAM framework [258,259]. The SWENSE approach has also been adopted by the CFD group at the University of Zagreb, who are lead developers in the foam-extend fork of OpenFOAM and the Naval Hydro Pack therein, which has been applied for naval architecture applications [260,261,262]. Simulations using the Naval Hydro Pack are submitted in the FPSO blind comparison test [125] using this SWENSE model [263].

4.3.2. Grid2Grid

Grid2Grid is a HOS wrapper program for RANS solvers, allowing ECN’s HOS-Ocean and HOS-NWT programs (detailed in Section 3.3.2), to be coupled with external RANS programs. Grid2Grid has recently been released by ECN, as an open-source software [264]. A validation study is conducted in [265], using Grid2Grid with OpenFOAM to simulate 2D and 3D regular and irregular waves, plus a 1000 year return period extreme waves, and comparing with experimental results.

4.3.3. OceanWave3D

Paulsen et al. [266] coupled OceanWave3D with OpenFOAM to enable efficient calculations of wave loads on surface piercing structures, motivated by studies showing that RANS simulations can accurately compute the hydrodynamic forces related to the “ringing” phenomenon, but that the simulations were restricted to short time series in a limited domain, due to substantial computational requirements. One way coupling was implemented, via relaxation zones, where the target solution for RANS is given by the NLPF solver. This coupling of OceanWave3D to OpenFOAM, now comes inbuilt with the wave generation toolbox waves2Foam [267]. Kemper et al. [268] extend this to include two-way coupling, where the solution of the NLPF is also influenced by the waves exiting the RANS domain, with the aim of being able to simulate WEC arrays and provide a validation case study considering wave propagation over a submerged bar.

4.3.4. qaleFOAM

The QALE-FEM software has recently been coupled with OpenFOAM, using a domain decomposition approach, to give qaleFOAM. Li et al. [269] detail the coupling and present an illustrative case study of a fixed submerged horizontal cylinder, subjected to input waves and currents. Li et al. [270] use qaleFOAM for the simulations of the FPSO subjected to focused waves in the blind comparison test [125] and to the moored HPA-like buoys subjected to focused waves [246] in the more recent blind comparison tests [247].

4.3.5. PVC3D

PVC3D (Potential Viscous Code 3D) is developed by MARINTEK, originally motivated by the works in Kristiansen [271] and Kristiansen and Faltinsen [272] to improve the modeling of “gap resonances”, which occur in moonpools or when two ships/structures are in close proximity. Around the gap resonance frequency, PF methods greatly overestimate the water and body motions, because the damping induced by flow separation is not captured, which can be rectified using the domain decomposition approach shown in Figure 12. A distinct feature of this particular domain decomposition is the submergence of the RANS-domain away from the free surface region, which improves the computational efficiency, as demonstrated by the moonpool study in [272], where 30 wave periods only require 73 s to simulate on a 2.4 GHz computer, and it compares well with experiments.

Figure 12.

Domain decomposition to capture flow separation around a ship in [272].

PVC3D is implemented in the OpenFOAM environment. Kristiansen et al. [273] present a validation study against experiments, as well as simulating the same cases in a pure RANS domain, where the simulations with PVC3D are between 3 and 4 orders of magnitude faster with comparable accuracy. The authors discuss that each simulation, comprising 40 wave periods, takes about 15 min on 4 cores, which is compatible with time-requirements in a design context, easily allowing parameter studies to be performed. However, they also note that they would expect run-times to increase for more complex geometries. PVC3D was later used to investigate the nonlinear roll damping on ships Ommani et al. [274], where the authors conclude that by using PVC3D, parameter studies are made possible.

In Cao et al. [275], an assessment of an LPF code (WAMIT), RANS code (Star-CCM+) and PVC3D is performed for waves inside of a moonpool, by validating results against experiments and comparing their runtimes. As expected, the WAMIT results over predict amplitudes around the resonance, whereas both the Star-CCM+ and PVC3D codes compare well to experiments. Comparing runtimes shows that the WAMIT simulations took less than 7 min on a single core, the PVC3D simulation took less than 16 min running on four cores, whereas the Star-CCM+ simulations took between 900–1020 min running on a 48 core cluster.

4.3.6. Others

Colicchio et al. [276] couple a BEM with a RANS solver, using a level-set technique to track the free surface interface, to handle large deformation, wave breaking, and fragmentation of the free surface. The BEM is used in the fluid domain wherever the interface is smooth and the RANS field solver used in the regions where PF theory is not suitable. They demonstrate the method on two validation cases considering; a dam break with impact on a wall and a water-on-deck of a ship examples. Siddiqui et al. [277] present a preliminary 2D domain decomposition example, coupling HPC to OpenFOAM, for the intended purpose of investigating the hydrodynamics of damaged ships. Their study includes validation against experimental data and videos from a model scale damaged ship hull which experiences flooding, sloshing and piston mode resonance inside of the hull. They show that the mesh size within the HPC domain can be much coarser than within the RANS domain as it has higher spatial accuracy. A preliminary 2D domain decomposition using the HPC method is also presented in Hanssen et al. [278], where the FNPF outer domain is coupled to a level-set Navier Stokes solver for the inner domain around the floating body. Ferrer et al. [232] develop a new OpenFOAM-based solver, "wsiFOAM", that couples NLPF to incompressible RANS, and then couples the incompressible RANS to a compressible RANS region, due to the importance of air effects on the slamming loads of a flap.

4.4. Potential Flow to SPH

SPH is a mesh-free, particle-based, Lagrangian technique for CFD, making it useful for solving problems with large motions/deformations and wave breaking. Like the mesh-based methods reviewed in this paper, there are varying levels of computational complexity that can be added to or simplified from the SPH method, such as weakly compressible versus fully compressible [279]. An overview of SPH for marine renewable energy is given in Stansby [280].

Considering WEC applications, domain decomposition has been applied to couple OceanWave3D with the SPH solver DualSPHysics in [242,243,244,245]. An initial proof of concept, with two way coupling, is demonstrated using a simple 2D HPA in Verbrugghe et al. [242]. Overall reasonable results are obtained, however, a number of discrepancies are evident in the results, due to the early stage in the development of this concept at the time. Regarding runtime, they utilized a GPU with 1920 cores and state that due to considerably long computation times (approximately 0.7 h for 1 s of simulation time with 1 million particles), it is necessary to keep the SPH domain as small as possible. Verbrugghe et al. [243] then presents a number of 3D WEC experiments, in an uncoupled SPH domain (requiring 23.4 million particles and 4.2 h for 1 s of simulation time) and discuss the possibility of coupling the SPH domain with OceanWave3D, showing the initial results from the 2D case. A more in-depth description and assessment of the coupling methodology is given in Verbrugghe et al. [245], where amongst a number of 2D test cases, a 2D OWC is considered. The results are compared against experiments, considering a purely SPH domain, as well as the decomposed domain coupled with OceanWave3D, where it is estimated an effective computational speed-up of 134–420% by using the domain decomposition approach to replicate the experimental wave flume test case. Verbrugghe et al. [244] then extend the coupling to 3D, considering a validation test case of an HPA in a narrow wave flume, showing good agreement for surface elevation, heave motion and horizontal surge force for a regular wave input. Here again, the results of a purely SPH domain are compared against the domain decomposition method and a speed-up in computational time of over 400% is observed.

Fourtakas et al. [281] present a very preliminary stage domain decomposition study, demonstrating a one-way coupling of SPH with the NLPF code QALE-FEM for a 2D wave propagation case. The future direction of this study is to develop a hybrid code capable of simulating large domains with an accurate prediction of extreme wave forces and slamming on offshore structures. Zhang et al. [282] then apply the SPH coupled to QALE-FEM code and apply it to the moored HPA-like buoys subjected to focussed waves in the blind comparison tests [247].

In additional to PF, other couplings with SPH have been presented in the literature, with Kassiotis et al. [283] demonstrating a one-way coupling with a Boussinesq-type model and Kumar et al. [284] presenting a coupling within the OpenFOAM framework, where the SPH method is used at free surfaces or near deformable boundaries and the mesh-based FVM is used over the larger fluid domain.

4.5. Potential Flow to Lattice Boltzman

The LB method represents the fluid as a field of particle distribution functions , specifying the probability of encountering a particle at position x, at time t, with velocity . The evolution of these distribution functions, f, is described by the Boltzmann equation, discretized in space and time, using a standard FDM. Turbulent effects can be modeled using wall functions [285,286] or captured at the sub-grid scale via a LES model (in combination with adaptively refined grids to improve computational efficiency and accuracy [287,288]). The efficiency and accuracy of the LB method have been demonstrated in many publications. For instance, Geller et al. [289] present a study of transient laminar flows benchmarked against finite element and finite volume solvers. In addition, the method can be efficiently parallelized to benefit from massively parallel hardware. Recently, GPU implementations of an LB model have achieved remarkable performance on GPUs [290].

LB models have been considered for use with domain decomposition for marine applications. Janssen et al. [291,292] report on the development and initial validation of a new hybrid numerical model for strongly nonlinear free-surface flows, including wave breaking and WSI. In this preliminary implementation, only a weak coupling is used where the nonlinear wave processes can accurately be modeled, prior to breaking, using FNPF. As the wave approaches breaking, the FNPF simulation can be stopped and the simulation data transferred to the LB model as an initial condition, and the LB model then simulated the highly nonlinear wave breaking process. This is an example of temporal domain decomposition, discussed in Section 4.7

Strong coupling between the FNPF-NWT and the LB model has been demonstrated by O’Reilly et al. [293] and Mivehchi et al. [294] who report on recent progress and validation of a 3D hybrid model for naval hydrodynamics problems. The coupling is implemented based on a perturbation method, in which both velocity and pressure are expressed as the sum of an inviscid flow with a viscous perturbation. The far- to near-field inviscid flows are solved with an FNPF theory, and the near-field perturbation flow is solved with an LB model whose solution is forced by results of the FNPF-NWT. The LB model developments in this work are based on the highly efficient, GPGPU-accelerated, LB solver ELBE [295] (www.tuhh.de/elbe). Although the ultimate goal for the reported work is to model seakeeping problems for multiple DoF floating bodies advancing in strongly nonlinear irregular wave fields, the considered case studies only consider turbulent flow over a flat plate and the turbulent flow around a submerged hydrofoil. More recently, [296] have presented WSI with surface piercing bodies (monopile and a ship hull), using domain decomposition to capture the local viscous solution around the body with a LB model and the inviscid solution away from the body using FNLPF solved with a BEM, using cubic B-splines, and accelerated with the parallel FMM.

4.6. Incompressible to Compressible

The effect of air compressibility inside an OWC chamber is discussed in Section 3.1.1. Domain decomposition could be leveraged in this case. This solution was suggested in the review by [297] and demonstrated in [232] for an OSC to accurately capture slamming loads.

4.7. Temporal Domain Decomposition

The use of temporal domain decomposition was discussed with the LB domain decomposition methods in Janssen et al. [291,292]. With consideration of WEC simulation, it may be possible to leverage a similar approach where lower-fidelity models can be run during conditions where minimal nonlinear effects are expected to occur, and then the solution transferred to higher fidelity solvers when certain thresholds in wave steepness or relative device/fluid motion are detected, for example. Bacigaluppi et al. [298] investigate detection criteria for wave breaking in their Boussinesq model, which then uses temporal domain decomposition to switch the Boussinesq equations to the nonlinear hydrostatic Shallow Water equations, where wave breaking occurs and models wave breaking fronts as shocks.

5. Computationally Efficient Modeling Techniques

With the goal of speed performance, a number of new modeling techniques have been considered in the field of wave energy, allowing high fidelity simulation of WEC performance but with low computation times to enable use within design loops. These techniques are reviewed in this section, namely: parametric models identified from data, probabilistic models, and nonlinear frequency domain (NLFD) modeling and are collated in Table 7, Table 8 and Table 9, respectively.

Table 7.

Review of publications utilizing system ID for WEC simulation, detailing the parameterization employed, the data source used, the type of WEC investigated, and the analysis performed.

Table 8.

Review of publications utilizing probabilistic methods for WEC simulation.

Table 9.

Review of publications utilizing NLFD models for WEC simulation.

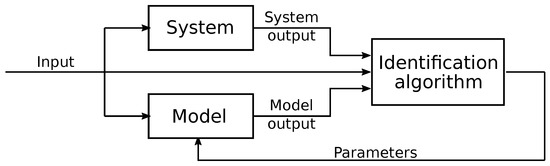

5.1. Parametric Models Identified From Data

A parametric model describes the WEC response by a finite set of parameters. Using system identification (SID) techniques, as depicted in Figure 13, the parameter values can be tuned using input/output training data from the WEC system, so that the model produces the same outputs given the same inputs. By selecting a computationally efficient model structure, with parsimonious complexity, the parametric model can achieve high fidelity (equivalent to the data it is trained upon) whilst retaining run times comparable to Cummins equation type models. An overview and examples of this approach are detailed in Ringwood et al. [299].

Figure 13.

Schematic of the system identification (SID) approach to obtain computationally efficient parametric models. The real system to be modeled generates the input and output data which are utilized by the identification algorithm to estimate the parameters of the model.

5.1.1. Model Structures

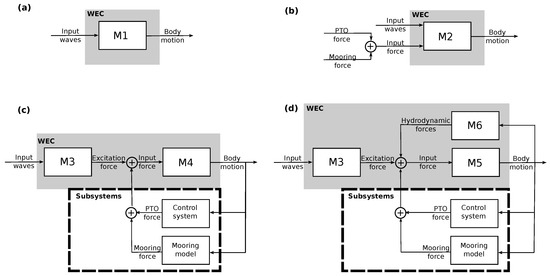

Figure 14 shows a schematic of the different model structures considered for SID of WEC hydrodynamics. The wave input to body motion, (Figure 14a), is demonstrated in [305,308,312], and mainly serves as a test case during the SID process, as the full WEC model will require an input PTO force at minimum, and possibly a mooring force if a floating WEC is considered. Including the input force directly, resulting in a multiple-input model, (Figure 14b), is demonstrated in [309] and represents a black-box modeling approach (discussed in Section 5.1.2). An alternative, grey-box, modeling approach, is to decompose the WEC model into two sub-models (Figure 14c), considering input waves to excitation force and then input force (comprising the sum of excitation, PTO, and mooring forces) to body motion. The identification of excitation force models, , is demonstrated in [307,309] and input force to body motion models, , in [304,305,306,308]. A lighter shade of grey-box modeling (Figure 14d) can include identifying models for restoring, radiation and/or viscous forces as a function of the WEC motion, , and then adding these as input forces, as demonstrated in [193,204,221,300,301,304,309,310] and also discussed in Section 3.7.1 for the viscous forces.

Figure 14.

Schematic of the various inputs and outputs to the models. (a) Input waves only. (b) Input waves and subsystem forces. (c,d) Input waves with modelling of the subsystems.

5.1.2. Model Parameterizations

SID provides significant flexibility in the choice of model parameterization, with respect to the trade-off between model fidelity and computational costs, and whether the parameters and variables relate to actual physical quantities or not. The relationship of the model structure to the physical properties of the system, categorizes the model parameterization into different shades of darkness, ranging from white- to black-box models. The structure of white- and grey-box models are well connected to the physical properties of the system and the model variables usually represent physical quantities. Whereas, the internal structure of black-box models bear no resemblance to the physical system and are only related via the replication of the same output given the same input.

An example of a white-box model, is Newtown’s Law of Motion, , where every term is a physical quantity. Given the complexity of the WSI problem for WECs, it is necessary to introduce some shade of darkness when modeling this complicated process. Examples of identifying a grey-box model are shown in [193,221,300,301,310], where the structure of the Cummins equation is utilized. Additional damping due to viscosity is identified from RANS experiments, then added to the radiation term to give an overall linearized equivalent damping. State-space parameterizations are considered for an HPA in Davidson et al. [193,300] and an OWC in Armesto et al. [301], and pseudo-spectral parameterizations are considered for an HPA in Davidson et al. [310] and Genest et al. [221].

Moving away from the Cummins equation structure to more nonlinear black-box type parametric models, such as artificial neural networks (ANNs), autoregressive with exogenous inputs (ARX), Hammerstein and Kolmogorov–Gabor Polynomial (KGP) models are investigated and detailed in [304,305,307,308,312]. In this work, it is observed the purely black-box models, such as ANNs, do not, in general, extrapolate from the training to validation data as well as models that contain some shade of grey and connection to underlying physics. Volterra-type models, suitable for systems with non-linear memory functions, are investigated in Van’t Hoff et al. [306] for an OSC device.

Although not explicitly hydrodynamic modeling, Gkikas et al. [302,303] present similar SID methods for thermodynamic modeling of the nonlinear pressure fluctuations inside an OWC. Using the wave elevation inside the chamber as a coupling link between the hydrodynamic and thermodynamic parts, SID techniques are employed to develop a Hammerstein–Weiner block-structured model, using a Volterra series for the dynamics. Similarly, Simonetti et al. [311] do not explicitly consider hydrodynamic modeling, rather they identify an empirical model as a design tool, which directly gives the power output for a given sea state, taking as input different design parameters. SID methods are also used to obtain efficient mooring models, using data from computationally expensive FEM models or physical experiments, as reviewed in [313], where the dynamics of the mooring systems have been replicated by polynomials, Taylor series, Volterra models and neural networks.

5.1.3. Identification Data

The requirements of the measured signals for the identification of a WEC model are discussed in Davidson et al. [314]. The input/output data used to determine the model must be sufficiently representative of the system dynamics and span the range of frequencies and amplitudes likely to be encountered during system operation. In the design phase for a WEC, there are two main options to obtain the input/output data of the system dynamics: either scaled model experiments in PWTs or using high fidelity NWT simulations. Comparison of these two options reveals a number of advantages to using NWT experiments to obtain the identification data:

- Scale: NWTs offer the significant advantage of being able to test at full scale. The scaling issue is a major drawback of using PWTs for SID of WEC models, since nonlinear effects may not upscale correctly from PWT to full scale, as discussed in Section 2.2.4 and Section 3.7.1, as well as in Cruz et al. [315]. However, numerically resolving some high fidelity models, such as RANS, at full-scale, can be computationally expensive (see [67]). Therefore, it is vital the SID experiments are designed to provide the maximum information in the minimum time (as discussed in [314]), otherwise NLPF models or domain decomposition techniques may be required for longer duration SID experiments in NWTs at full-scale.

- Reflections: NWTs are superior in eliminating undesired reflections from the tank walls contaminating the SID experiments, with numerical absorption zones able to limit reflections below 1% [316], whereas world-class PWTs can incur reflection coefficients of around 10% [315,317] in the wave propagation direction, and often have no side wall absorption.

- Constraints and restraints: NWTs allow the WEC to be easily constrained to single DoFs, allowing SID of each DoF separately if desired, whereas PWTs require complex mechanical restraints to achieve this task, which introduces friction and alters device dynamics. The same is true for external forces, which can be applied exactly to the WEC in an NWT, but require physical actuators in a PWT which introduce some level of inaccuracy.

- Measurements: NWTs allow non-intrusive measurement of as many variables as desired, with zero measurement noise, without requiring physical measuring devices to be added to the system. Schmitt et al. [9] discuss a significant challenge of PWT experiments is to ensure that the measurement instrumentation is as non-intrusive as possible and does not contaminate any of the results. NWTs also allow easy measurement of some useful variables which are extremely difficult/impossible to measure in a PWT, such as the exact pressure everywhere on the WEC surface, or the fluid velocity and vorticity around the WEC.

- Cost: In the design phase of a WEC development, varying the WEC geometry may be necessary for optimization studies, which can easily be implemented in an NWT through a few lines of code, whereas a physical prototype needs to be manufactured for each geometry tested in a PWT. Schmitt et al. [9] also discuss that a significant investment of resource and money often goes into the design, manufacture, installation, and calibration of specialized pieces of PWT measurement equipment often custom made for a particular WEC design and scale, whereas in an NWT, sensors, actuators, and constraints can be arbitrarily added through a few lines of code. Furthermore, time at a PWT facility can range from hundreds to tens of thousands of euros per day.

- Availability: Testing time in PWT facilities must be organized months in advance and is kept to a tight schedule, whereas with the rise of cloud computing, NWT resources are always available, multiple experiments can be run in parallel and testing time can be increased on the fly.

The main disadvantage to high fidelity NWT experiments is the substantial computational requirements to obtain sufficiently long datasets to adequately train and validate the identified models. However, these time consuming, computationally heavy, NWT simulations only need to be run once, after which a parametric model can be identified, using the input/output data from the NWT simulation. The parametric model can then used for future WEC design simulations, of the same device geometry, in different sea states, PTO, control and/or mooring configurations et cetera, at a fraction of the computation time. Nevertheless, the numerous advantages of using an NWT for SID purposes highlights the importance of leveraging the methods reviewed in Section 3 and Section 4 to enable computationally efficient, high-fidelity, NWT simulations.

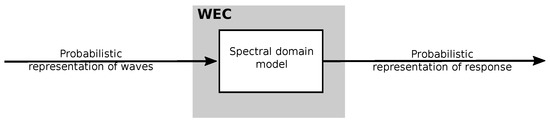

5.2. Probabilistic Models

A probabilistic model does not calculate a distinct WEC response to a particular input wave, as is the case for deterministic models, but instead generates probabilistic quantities, such as mean expected values, standard deviations, probability distribution functions et cetera, from a statistical representation of the inputs (depicted in Figure 15). Therefore, this method is extremely efficient at calculating statistical parameters, such as the average power, since multiple time-domain simulations are required to build-up meaningful statistics, which by comparison can be generated in a single run by a probabilistic model.

Figure 15.

General structure of a spectral domain model (reproduced from [322]).

The first use of these types of probabilistic models for WEC analysis is presented in Falcao and Rodrigues [318], where stochastic methods are used to model the power performance of OWC plants and optimize the turbine size and rotational speed for maximum energy production. Assuming the input sea states to be Gaussian, the air pressure inside the OWC chamber is regarded as the response of a linear system comprising the chamber and Wells turbine. This approach has been used more recently for the analysis of a floating OWC spar buoy in Gomes et al. [319,320]. Bachynski et al. [321] also apply probabilistic modeling, using linear models, to enable computationally efficient design and optimization of the geometry, mass distribution, mooring system, and PTO damping for an HPA. In essence, these two cases [318,321] utilize a frequency-domain model for the system response and assume the incident waves are a Gaussian process, which means that the WEC response is also a Gaussian process (as the system is linear), allowing statistical properties to be easily obtained.

In the past decade a number of more advanced probabilistic models, which allow the inclusion of nonlinear dynamics, have been applied to WEC analysis and are presented in Section 5.2.1 and Section 5.2.2.

5.2.1. Spectral Domain

Spectral-domain (SD) models are based in the FD, producing results for a given sea state at a fraction of the computational cost of time-domain simulations. However, SD models can be also be applied to nonlinear systems, but the computational effort increases, requiring an iterative solver to successively approximate and converge on the solution. A thorough overview of SD modeling for WECs is given in Folley [322], which discusses that current SD models use Gaussian closure, which assumes that the WEC response is Gaussian and the nonlinear force can be differentiated to enable a quasilinear coefficient to be calculated via statistical/equivalent linearization. For example, the method of Gaussian Closure is used in Nie et al. [325] to accommodate nonlinear WEC dynamics and complex loss mechanisms in PTO, in the implementation of optimal control in stochastic waves. The technique is demonstrated through a numerical example considering an OSWC with a hydraulic PTO.

Considering SD analysis of WECs, Folley and Whittaker [220] use equivalent linearization to model the effects of drag forces and large-angle rotations for an OSWC. It was shown in these cases that equivalent linearization produces a model that predicts a statistically very similar response to time-domain models even for relatively high levels of nonlinearity. Subsequently, in Folley and Whittaker [323], an SD model for an array of HPA WECs, with a Coulomb-friction type force, has been developed and shown to provide a reasonable estimate of the statistical response of the system in the majority of cases compared against tank data. In Folley and Whittaker [324] an OWC is tested in a wave tank to produce validation data for an SD model comprising linear hydrodynamic coefficients obtained from WAMIT, together with single-coefficient non-linear terms for the PTO and the entry/exit losses of the water column. The OWC was tested in a range of representative sea-states with both unimodal and bimodal spectra, and the SD model was shown to reproduce the performance of the OWC accurately, with the power capture typically predicted within 5% of the experimental data.

Tom et al. [326] and Ding et al. [328] use SD models, including quasilinear drag coefficients linearized from the quadratic nonlinear drag force. Tom et al. [326] investigate an OSWC with controllable surfaces, whose time-varying geometry can increase capacity factor and reduce design loads. The SD model is used to calculate load and power statistics and compared against a purely linear analysis, and the authors conclude that the SD techniques provide a quick and efficient methodology for evaluating the WEC performance in irregular waves at a mid-fidelity level. Ding et al. [328] investigate a submerged HPA and compare the results of the SD model against a nonlinear time-domain model, for three different irregular sea states, observing differences in the predicted power outputs of less than 10%. Gunawardane et al. [327] investigate including the effect of nonlinear hydrostatic stiffness into an SD model for a heaving sphere WEC, comparing the results against time- and FD models. Compared to the FD model, the SD model is shown to closely match the time domain results across a greater range of sea states, capable of accurately reproducing the results in all but the most extreme waves. Silva et al. utilize statistical linearization for efficient nonlinear modeling of an HPA [331] and OWC [332] showing close agreements with the power spectrum density obtained from a time-domain simulation.

5.2.2. Polynomial Chaos

Unlike the SD method, polynomial chaos (PC) is based in the time-domain, providing an efficient surrogate model for stochastic differential equations. PC represents the stochastic process with a series of orthogonal polynomials, which reduces the dimensionality of the system and leads to exponential convergence of the error [333]. Traditionally, to obtain meaningful statistics for such stochastic systems, containing random inputs and/or uncertainty in the parameters, requires thousands of simulations using brute-force approaches, such as the Monte Carlo method where the accuracy scales inversely with the square root of the number of simulations. PC provides an alternative approach to obtain the statistical values, with comparable accuracy but orders of magnitude less computation.

The PC method is highly efficient for uncertainty quantification, able to effectively describe the input uncertainties, how they propagate through the system, their influence on the dynamics, and provide probability distributions of the system outputs. PC has been applied to uncertainty quantification in a number of studies related to nonlinear hydrodynamics. Ge et al. [334] implement the PC method in nonlinear shallow-water flows for long-wave transformation over a submerged hump. The uncertainty is introduced as the mean and standard deviation of the heights of the input wave and the hump, respectively, producing almost identical results to the Monte Carlo method, but at small fractions of its computing cost. Kreuzer and Solowjow [335] apply a preliminary study of PC for the heave motion of a cylinder in random seas, utilizing a linear Cummins model for the hydrodynamics so that an FD model can also be used to benchmark the results against, finding an exact match for the mean and an 8% difference in the variance, when using only a 1st order polynomial. Bigoni et al. [336] present an FNPF model for WSI and use PC to consider the sensitivity of the free-surface solution and loads on a structure, due to a number of uncertainties that are likely to appear in experimental settings. The uncertainties include the bathymetry due to lack of precise knowledge of the bottom topography or the unknown action of sedimentation, the input wave characteristics due to inaccuracies in the wavemaker systems, and the water height due to evaporation and water leakage/spills. Lim et al. [337] utilize PC to study the long-term extreme surge motion of a simple moored offshore structure, considering uncertainty in significant wave height and peak period characterizing the sea state conditions, and in the uncertainty due to the application of random phases when generating a time-domain signal from the frequency components in a given sea spectrum. Comparing exceedance probability curves obtained from PC against those obtained from Monte Carlo simulations shows similar results but that the Monte Carlo method required 1000 times more simulations than then PC method.

The PC method has very recently been applied to WEC analysis in Nyugen et al. [329] and Parades et al. [330] considering HPAs. In [329], PC is leveraged to calculate long-term extreme loads, which traditionally require extensive simulation due to their low probability of occurrence. The PC method requires 49 WEC simulations to produced comparable results to the Monte Carlo method with simulations. [329] concludes that the PC method shows promise for fast, efficient and accurate assessment of extreme loads during the design process. Parades et al. [330] investigate the influence that uncertainty in the PTO stiffness and damping coefficients has on the mooring tension, the body motions, and the absorbed power. By utilizing PC, only 100 WEC simulations were required to gain the equivalent information of 3000 time-domain simulations with varying PTO stiffness and damping coefficients.

5.3. Nonlinear Frequency Domain

The nonlinear frequency domain (NLFD) approach is a form of Galerkin method [338,339] that projects the system inputs and outputs onto a Fourier basis, to represent the nonlinear dynamics in the FD as a harmonic balance equation. The resulting set of nonlinear equations can be solved using a gradient-based technique, to compute the nonlinear steady-state response of a WEC to a periodic excitation signal. The effectiveness of the method, for the case of nonlinear oscillators, compared to statistical linearization and Monte Carlo simulation is shown in Spanos et al. [338]. The application of this method to WEC modeling was first demonstrated in Merigaud and Ringwood [340].

Although slower than the SD approach, the NLFD has significant benefits in terms of accuracy, range of applicability and the ability to produce time-domain results. The NLFD can handle strong nonlinear dynamics, provided the WEC outputs remain smooth, and is, therefore, unsuitable for applications such as latching control or extreme conditions where end stops collisions may occur. In contrast to time-domain integration, the NLFD formulation only allows for the consideration of periodic steady-state regimes and does not consider transients.

The issues associated with the practical implementation of the NLFD technique are detailed, and illustrated in Merigaud and Ringwood [341], presenting an example case of an HPA with quadratic nonlinear viscous and NLFK forces. The NLFD method is shown to run more than 50 times faster than a Runge-Kutta 2 (RK2) time integrator for the same level of accuracy. However, for an example case with Coulomb damping in the PTO and a correspondingly non-smooth WEC output, the NLFD takes a long time to converge, and in fact, takes longer than the RK2 integrator and does not achieve the same level of accuracy. The NLFD method is extended to multiple DoF in Novo et al. [342], considering the pitching hull motion and the internal gyroscope dynamics of the ISWEC device operating at a site in the Mediterranean Sea as a case study. The study showed that the NLFD method is sensitive to the algorithm starting point and found for some highly energetic sea states the method did not converge. However, for the majority of the sea state, it is concluded that computational gains of between one and two orders of magnitude can be expected with respect to RK2. Merigaud and Ringwood [343] then apply the method in the synthesis of optimal control for an OSC.

In addition to the WEC hydrodynamics, Wei et al. [344,345] apply the NLFD method to the PTO system in the Ocean Grazer, comprising pistons and pumps. It is envisioned that such a device could comprise hundreds of floating elements and pistons, thus necessitating a computationally efficient modeling method for its analysis. In [344], a single floater with pumping unit is investigated and the numerical simulations show good agreement with experimental results, able to assess the power output well but not the high-frequency responses such as slamming. Of interest is the ‘sticking’ phenomena in the PTO pumps, when the wave excitation force is lower than the pumping force, which can only be captured by simulations using a high number of Fourier components and for which case the computational cost increases dramatically since the Fourier series of discontinuous functions converges very slowly. In [345] the method is then applied to an array of 18 units.

6. Discussion

Selecting an appropriate WEC simulation tool can depend on a number of factors, which are discussed here. The requirements of a WEC simulation tool were detailed in Section 1.2, namely computational, fidelity, and flexibility requirements. The computational and fidelity requirements are discussed in Section 6.1 with respect to the different types of end-use for which the WEC simulation tool is to be applied. The flexibility requirements pertain to the different classes of WEC devices and their various operational principles, for which certain simulation methods may or may not be well suited, as discussed in Section 6.2. The role of open-source software in the next generation of WEC design tools is discussed in Section 6.4, and consideration of computing hardware discussed in Section 6.5. A summary is provided in Section 6.6, where the strengths and limitations of the different methods reviewed in this paper are tabulated.

6.1. Applications

In general, there is a trade-off to be made between computational efficiency and level of fidelity. Selecting the simulation tool which provides the appropriate trade-off between these two requirements depends on the type of WEC simulation application under consideration. The requirements are different for at least three different end uses of a WEC simulation tool, summarised in Table 10 and discussed in Section 6.1.1, Section 6.1.2 and Section 6.1.3.

Table 10.

Requirements of the different end uses of a WEC simulation tool.

6.1.1. WEC Design—Productivity, Loading, and Survival Characterizations in Operational Sea States

There are a wide variety of sea states at a given location, which must be simulated to fully characterize the potential energy output, mooring loads, fatigue analysis, optimal PTO sizing et cetera, of a candidate WEC design. To accommodate the large amount of simulation required, this case has traditionally been reasonably well served by LPF and Cummins models, particularly in the frequency domain, as well as the NLFK approaches in the time domain (the low-fidelity high-speed end of the spectrum introduced in Section 1.3). Nevertheless, there are a number of shortcomings in these approaches that motivate a search for a minimal increment to a higher fidelity method. In addition to the problems associated with neglecting viscosity (discussed in Section 2.1.1), the main shortcomings of these methods is that the LPF approach assumes small body displacements (including small body rotations) and calculates the wave forces on the mean wetted surface, this assumption is often not valid especially in moderate and large waves. (The NLFK method calculates the FK forces on the instantaneous wetted surface but still calculates scattering and radiation forces on the mean wetted surface). Problematic aspects of simulation performance related to these assumptions include:

- Wave excitation forces are overestimated in all but the smallest waves.

- When body rotations are large there is no justifiable method for determining whether to apply the calculated wave forces in a reference frame that moves with the body or a reference frame that is fixed to the body’s mean position. Neither approach is correct and both approaches result in incorrect results.

- There is no automatic way to enforce the Budal limit [347], this leads to simulation results that are invalid due to unrealistically large amplitudes of motion.

- Because the Budal limit is not enforced estimated performance of designs that would violate this limit is not properly penalized so geometry optimizations that converge on these designs are not reliable. This is a particular problem for objective functions that favor smaller devices (e.g., energy yield per surface area or energy yield per cubic displacement). In the worst instances, this issue leads to convergence on physically meaningless solutions such as WEC devices with zero area/volume/stroke.

A better method that resolves these difficulties will be non-linear and as a minimum will be body-exact with respect to forces due to both FK pressure and wave scattering effects. For example, Todalshaug [348] further elaborates on the Budal limit, discussing and demonstrating the dependence of the maximum power capture on the wave radiation pattern and the radiation resistance, which highlights the importance of accurately capturing the wave scattering effects. To this end, the weakly nonlinear methods, in Section 3.5, appear to be an appropriate selection among the methods reviewed in Section 3.

Nevertheless, while the high fidelity time-domain models, such as the FNPF and weakly nonlinear methods, can return accurate calculations for the WEC response, they are less able to provide good statistical estimations for the quantities of interest, such as the yearly energy yield. Building reliable statistics requires a very large number of simulations, spanning the various sea states as well as the possible realizations of each sea state (different random phases for each frequency component). Alternatively, the computationally efficient modeling methods in Section 5 seem the most well suited to this task. Indeed, the SD approach can automatically give a statically relevant estimation of the yearly energy yield, from one simulation. Therefore, the modeling approaches able to include nonlinear effects whilst allowing an FD/SD simulation, would be very attractive. However, one possible limitation for these methods may be in enforcing constraints on the solution variables, such as maximum allowable displacements or PTO forces et cetera. Again, in relation to the Budal limit, Todalshaug [348] presents the upper bounds on power capture when considering physical constraints such as limits on the maximum stroke-length.

It is worth mentioning, that in addition to the fidelity of the WEC simulation tool, the accuracy of the simulations for WEC design also depends on the accuracy of the representation of the input sea states. Real sea conditions are highly complex, requiring some level of parameterization to enable an efficient representation to be utilized by computational models. Therefore, there exists a similar trade-off in fidelity versus computational complexity, when considering the description of the input wave signals to the WEC simulations. This is examined in Kofoed and Folley [349] and in Merigaud and Ringwood [346], whose findings can be summarized that efficient WEC design simulation requires a balance between the accuracy of the wave climate representation, the accuracy of the WEC simulation tool and the computational demands of the calculation.

6.1.2. WEC Design—Loading and Survival Characterizations in Extreme Sea States