1. Introduction

With the growing demand for ocean exploration and underwater resource development, autonomous underwater vehicles (AUV) have become indispensable tools in military, scientific, and commercial applications. These mission-critical systems require propulsion solutions that combine high efficiency, operational reliability, and wide speed-range capability. Traditional thrusters with mechanical transmission systems face inherent limitations, such as frictional losses, high maintenance, and acoustic signatures, hindering their deep sea and long-term performance. The emerging shaftless pump-jet thruster (SPT) technology addresses these limitations through an integrated motor–impeller design that eliminates conventional transmission components. This innovative configuration offers significant advantages in hydrodynamic efficiency and thruster performance across various speed regimes [

1,

2,

3,

4], along with reduced system complexity and weight.

At the heart of SPT systems lies the stator sleeve, a critical component that must simultaneously fulfill multiple functional requirements: providing structural integrity under extreme hydrostatic pressures, maintaining corrosion resistance in seawater environments, and ensuring optimal electromagnetic performance. Conventional titanium alloys, particularly Ti64, are the preferred choice for such demanding marine environments because of their excellent corrosion resistance, high specific strength, and proven structural reliability [

5,

6]. However, they present a fundamental limitation for electromagnetic applications—their relatively low electrical resistivity (approximately 1.7 μΩ·m). Low resistivity results in a higher eddy current under alternating magnetic fields, causing both energy loss and undesirable thermal effects [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. These thermal effects are particularly challenging in underwater applications where active cooling options are limited, potentially leading to insulation degradation, mechanical deformation, and reduced operational lifespan.

To mitigate eddy current losses, significant research efforts have been directed toward alternative sleeve materials and configurations, which can be broadly categorized into three approaches, each with inherent trade-offs. The first approach employs bulk low-conductivity materials, such as ceramics or fiber-reinforced polymers. While these materials offer excellent eddy current suppression [

12,

13,

14], their severe limitations in mechanical strength, poor weldability to metallic housings, and challenges in ensuring long-term hermetic seals make them unsuitable for high-stress underwater environments [

15]. The second, more prevalent approach is the metal–insulator hybrid sleeve, which mechanically assembles conductive structural parts with insulating layers. Recent studies have demonstrated its effectiveness in balancing electromagnetic shielding with structural needs [

16,

17,

18]. Nevertheless, this architecture inherently introduces material interfaces, leading to concerns over thermal contact resistance, potential delamination under thermomechanical cycling, and increased manufacturing complexity. The third approach involves electromagnetic design modifications, such as axial segmentation or slitting of the conductive sleeve. Although these methods can reduce eddy currents, they often compromise structural integrity, hydrodynamic performance, or manufacturing yield. Consequently, the pursuit of a monolithic sleeve material that intrinsically possesses high strength, excellent corrosion resistance, and tailored electromagnetic properties remains a significant and unresolved challenge.

Titanium Matrix Composites (TMCs), renowned in aerospace and advanced engineering for their superior specific strength, fatigue resistance, and high-temperature performance compared to conventional titanium alloys, offer a promising yet underexplored pathway. While extensive research has focused on their mechanical and tribological properties, their electromagnetic characteristics—particularly the tailorable anisotropic conductivity achievable through controlled fiber orientation—have received scant attention in the context of electrical machines. This represents a critical knowledge gap [

19].

Crucially, foundational studies in related fields have demonstrated that the electromagnetic properties of composite materials, including aspects like anisotropic electrical conductivity, can be effectively tuned through microstructural design. This pivotal insight shifts the paradigm: it inspires us to regard TMCs not merely as passive structural materials, but as intrinsically designable electromagnetic functional materials [

20,

21].

This new paradigm fundamentally differs from the aforementioned hybrid assemblies. Instead of mechanically combining discrete materials, a monolithic anisotropic TMC sleeve could suppress eddy currents through its intrinsic, graded material property, thereby potentially eliminating interfacial issues inherent to multi-material designs while preserving the weldability and toughness of a titanium-based matrix.

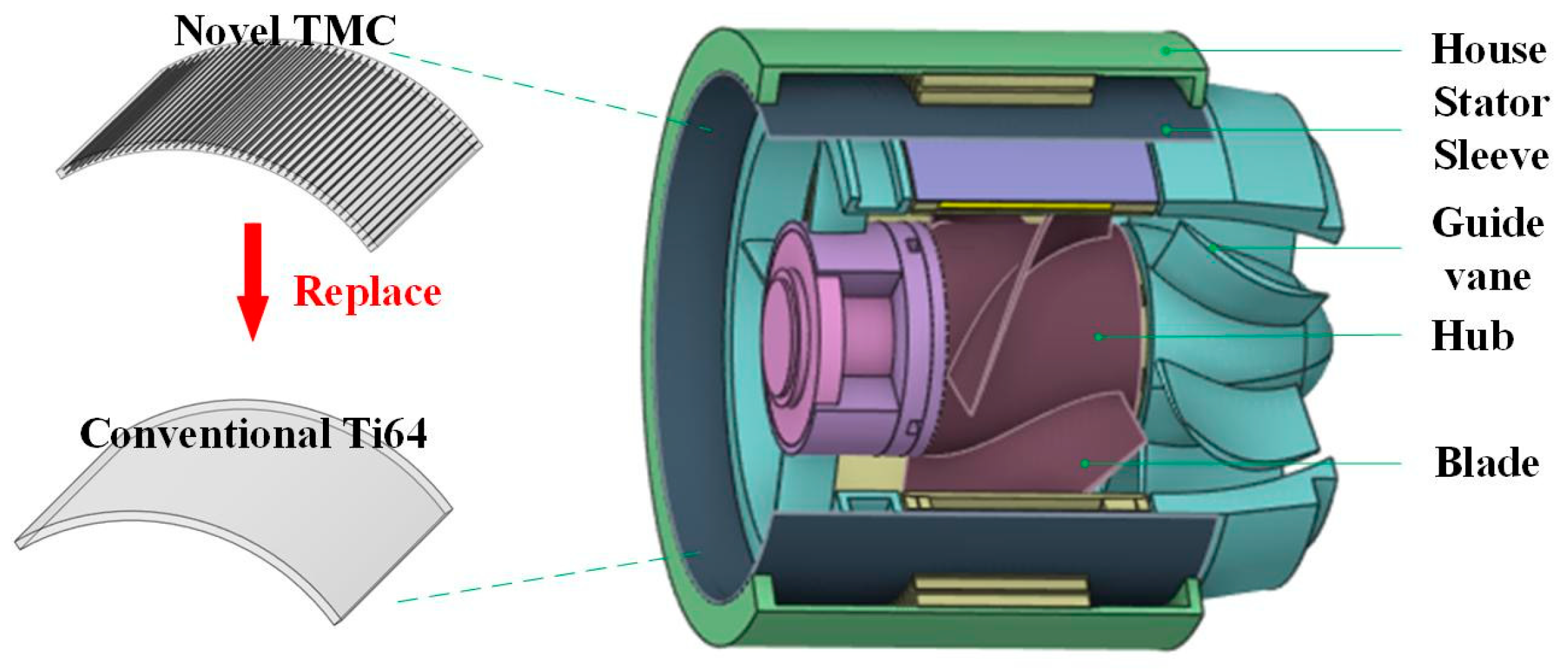

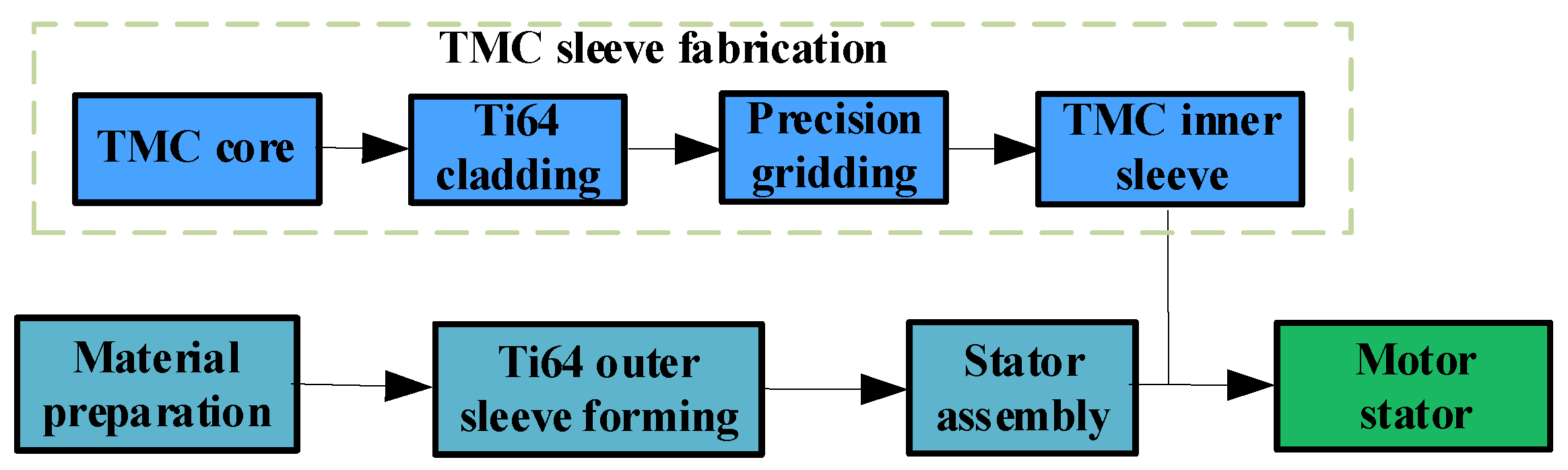

This study addresses this critical research gap by introducing TMCs as a multifunctional material for stator sleeves in underwater motors. By incorporating SiC fibers with low electrical conductivity (8600 S/m) into the titanium matrix, TMCs can achieve substantially enhanced electrical resistivity while retaining the mechanical advantages of conventional titanium alloys. As shown in

Figure 1, TMC was used for the inner sleeve of the motor stator. The strategic integration of SiC fibers creates a composite sleeve with anisotropic conductivity that effectively suppresses eddy current losses.

This study assesses TMC the potential of the stator sleeve to replace the Ti64 stator sleeve in shaftless motors through coupled simulation and experimentation. Electromagnetic simulations first predicted the performance advantages of TMC sleeves over conventional Ti64 sleeves. For experimental validation, two identical stators were fabricated, one equipped with a Ti64 sleeve and the other with a TMC sleeve, and tested under the same operating conditions to enable direct performance comparison.

2. Material and Measurement

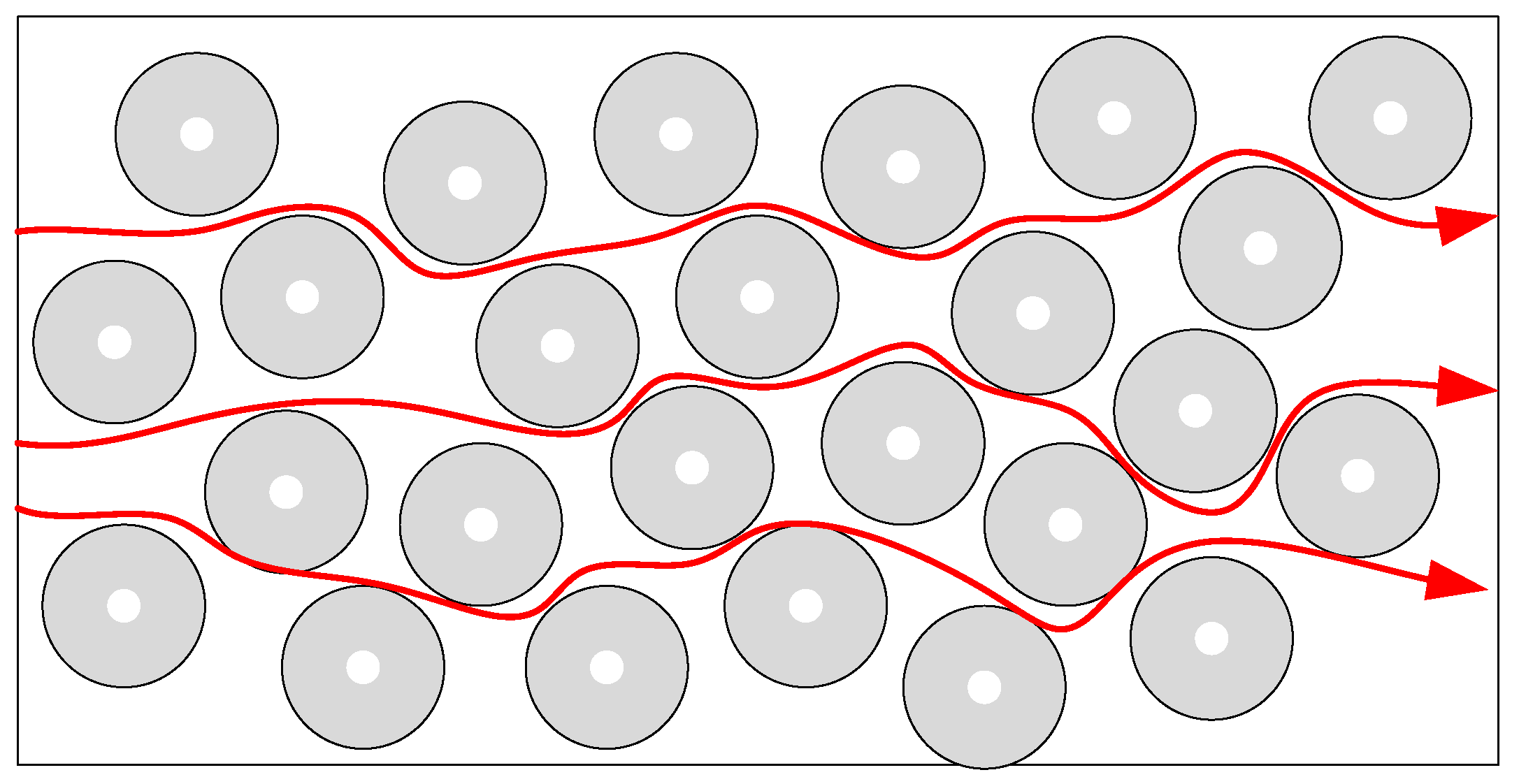

The introduction of SiC fibers into the Titanium Matrix Composite (TMC) creates strong conductivity anisotropy, characterized by distinct values along the fiber direction (σ

//) and perpendicular to it (σ

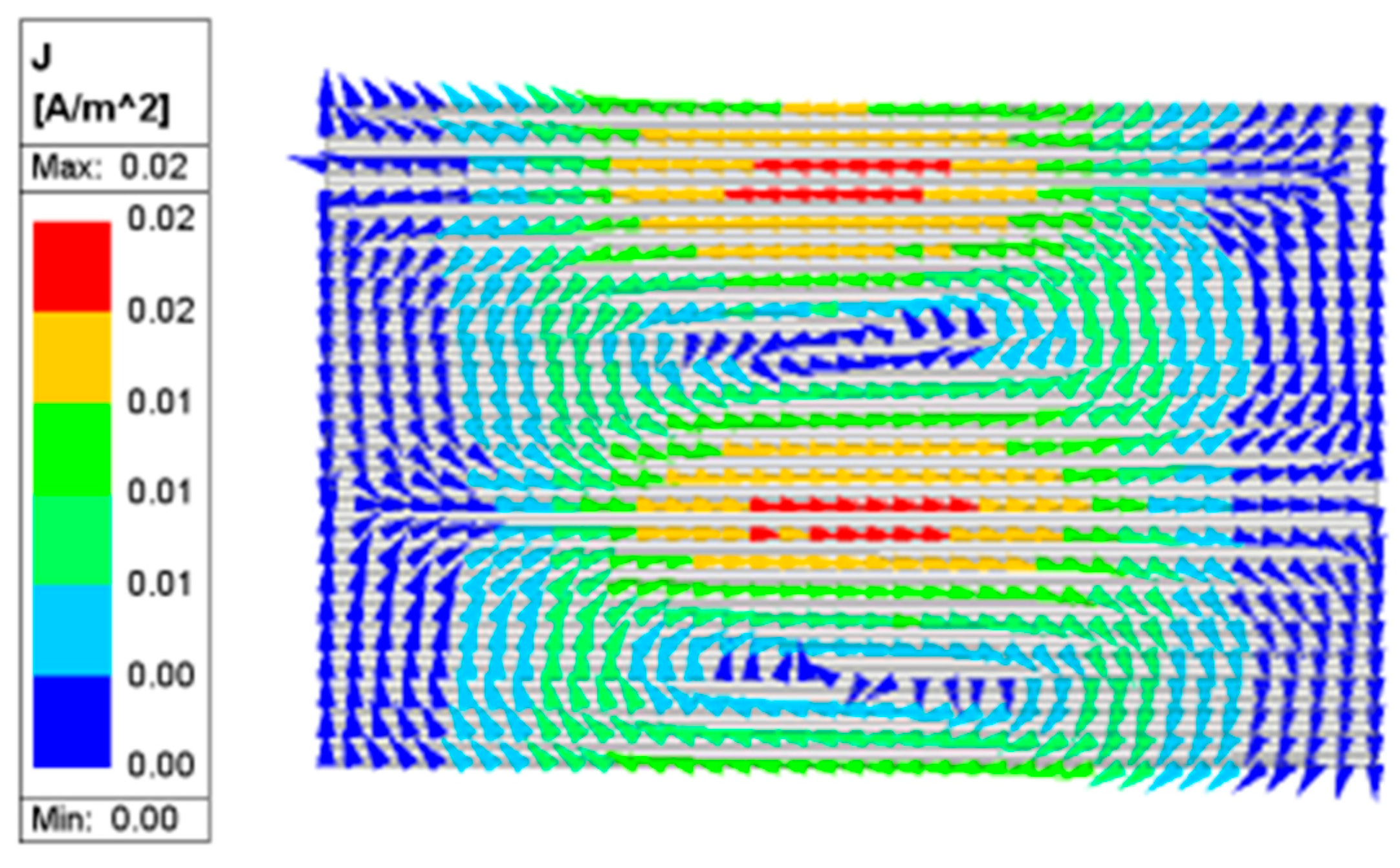

⊥). At the microscale, local fiber misalignment leads to measurable conductivity fluctuations. When current flows perpendicular to the fibers, conduction exhibits complex multiscale behavior. Currents must circumvent the insulating fibers, causing field distortion and localized current concentration, as shown in

Figure 2. This renders simple rule-of-mixtures models inadequate.

To predict the effective transverse conductivity σ

⊥, Effective Medium Theory (EMT) is employed. The Bruggeman symmetric model is particularly suitable, as it treats both phases as embedded in a self-consistent medium and naturally accounts for fiber interactions. Its governing equation for transverse conductivity is as follows:

where

f is the fiber fraction, σ

m is the conductivity of the matrix metal, and σ

f is the conductivity of the fiber. This provides a theoretical foundation for modeling the TMC as an orthotropic medium.

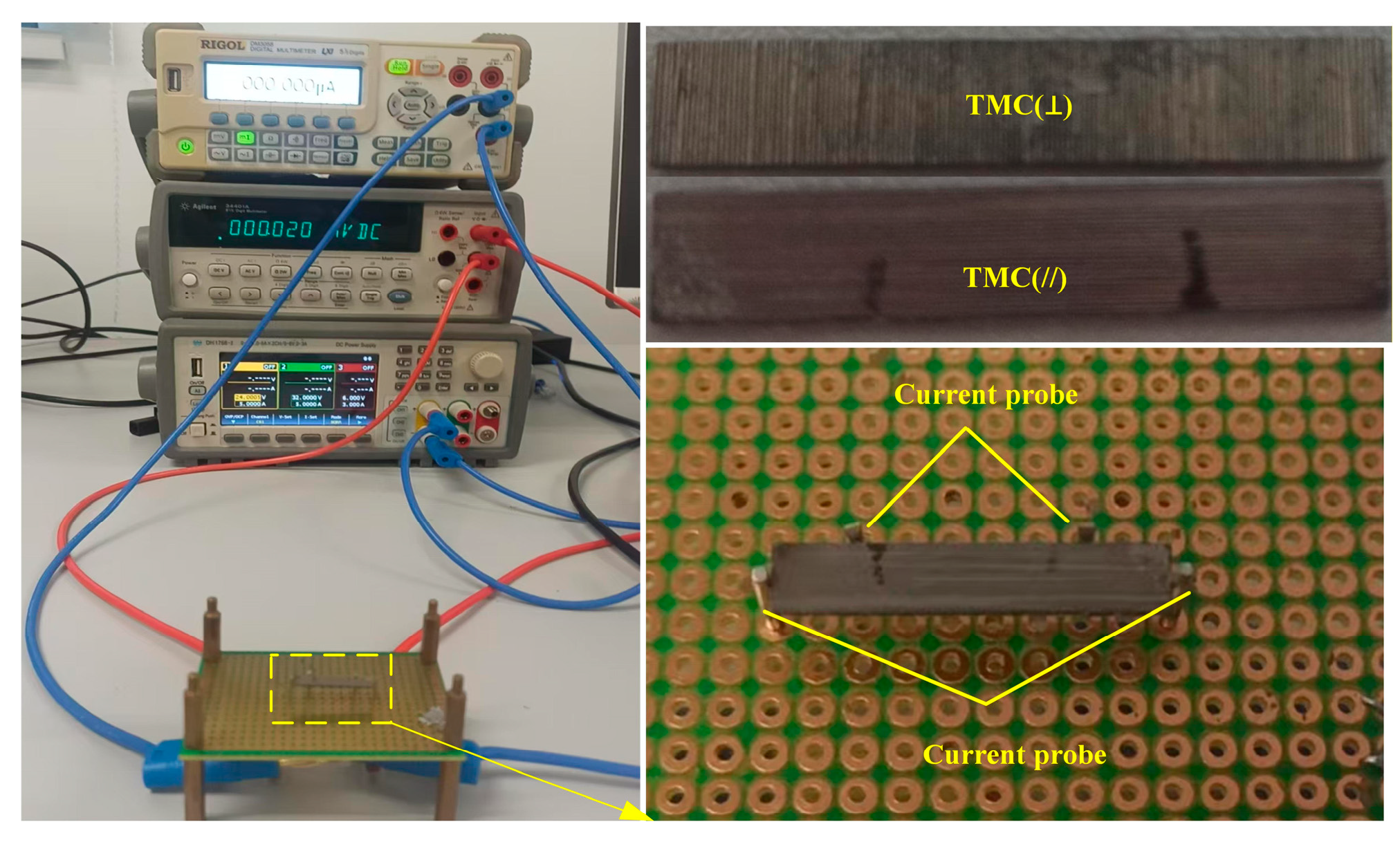

The macroscopic conductivities parallel (σ

//) and perpendicular (σ

⊥) to the primary fiber orientation were experimentally characterized using a four-point probe method to ensure accurate input for electromagnetic simulations, as shown in

Figure 3. A RIGOL DH1766-z DC power supply with an output current accuracy (±0.1%) provided stable current excitation, while the resulting voltage drop was measured using an Agilent 34401A digital multimeter (manufacturer: Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) (DC voltage accuracy: ±(0.0035% + 5 digits) on the 10 V range). The measurement process was controlled and data were acquired through the DH1766-based programmable system. The electrical conductivity was derived from the measured voltage–current relationship. For each sample, multiple measurements were taken and averaged to obtain the reported value for a given condition. Taking into account the specified instrument accuracies and the measurement repeatability (standard deviation < 1%), the overall estimated uncertainty of the conductivity values is within ±2%.

As shown in

Figure 3 and

Table 1, the anisotropic electrical conductivity of the TMC was characterized. For the fabricated sleeve sample with a fiber volume fraction of approximately 51%, the Bruggeman model predicts a theoretical transverse conductivity (σ

⊥) in close agreement with the range of experimental values. The experimentally measured values are σ

// = 285.71 kS/m (a 54.26% reduction compared to Ti64) and σ

⊥ = 121.95 kS/m (an 80.48% reduction compared to Ti64). These results establish a validated operational conductivity range for practical sleeve applications.

The key physical properties of both materials are summarized in

Table 2. The results confirm the pronounced electrical anisotropy of the TMC: σ

// = 285.71 kS/m and σ

⊥ = 121.95 kS/m, corresponding to reductions of 54.3% and 80.5%, respectively, compared to the isotropic Ti64 (σ = 624.00 kS/m). TMC exhibits superior thermal conductivity, lower density, and significantly higher tensile strength. This combination of high strength, reduced weight, tailored electrical anisotropy, and enhanced thermal transport defines the integrated multifunctional property profile of the TMC, which is critical for the performance of the designed sleeve component.

3. Comparative Analysis of Motor Simulation Performance

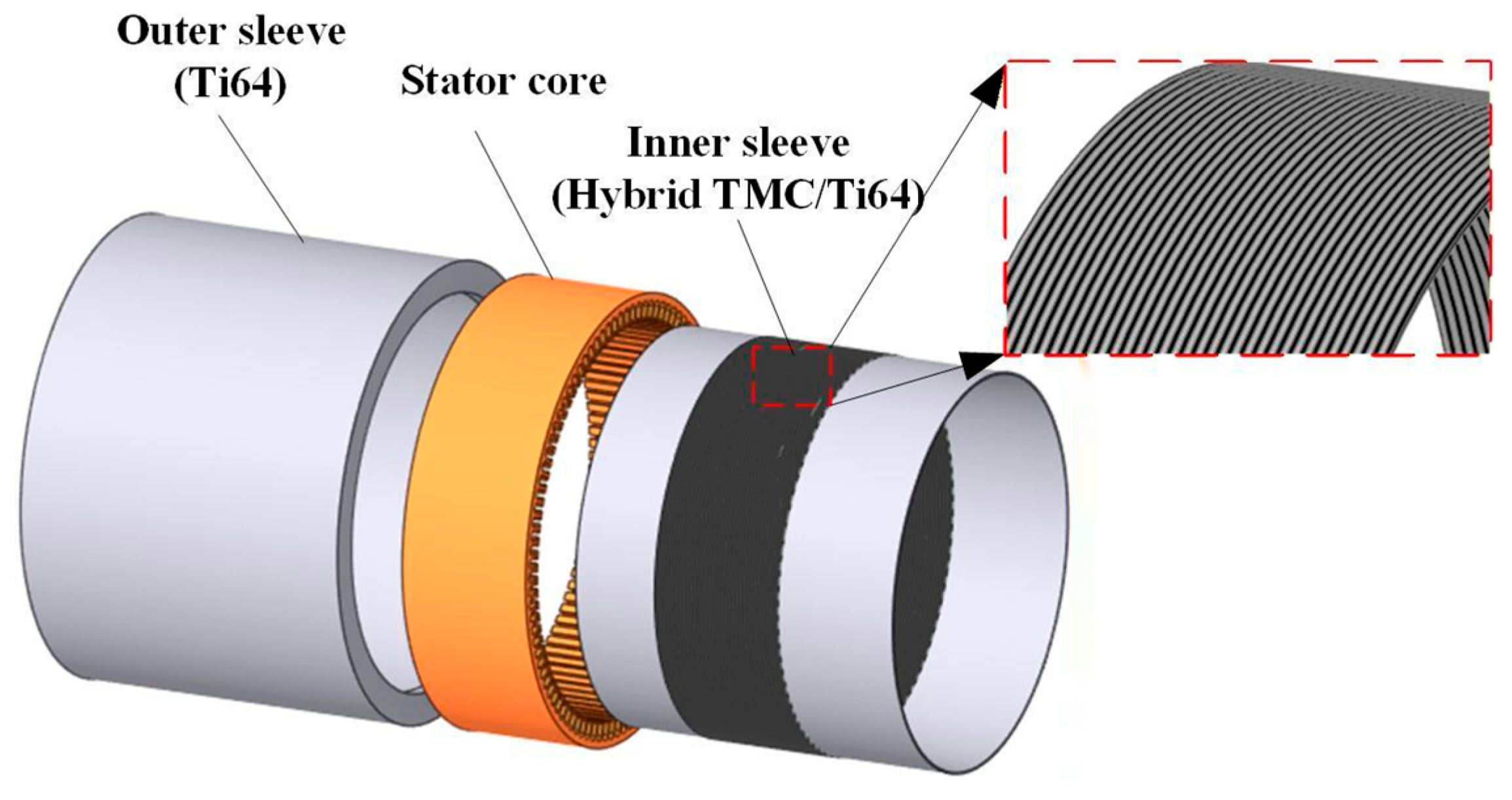

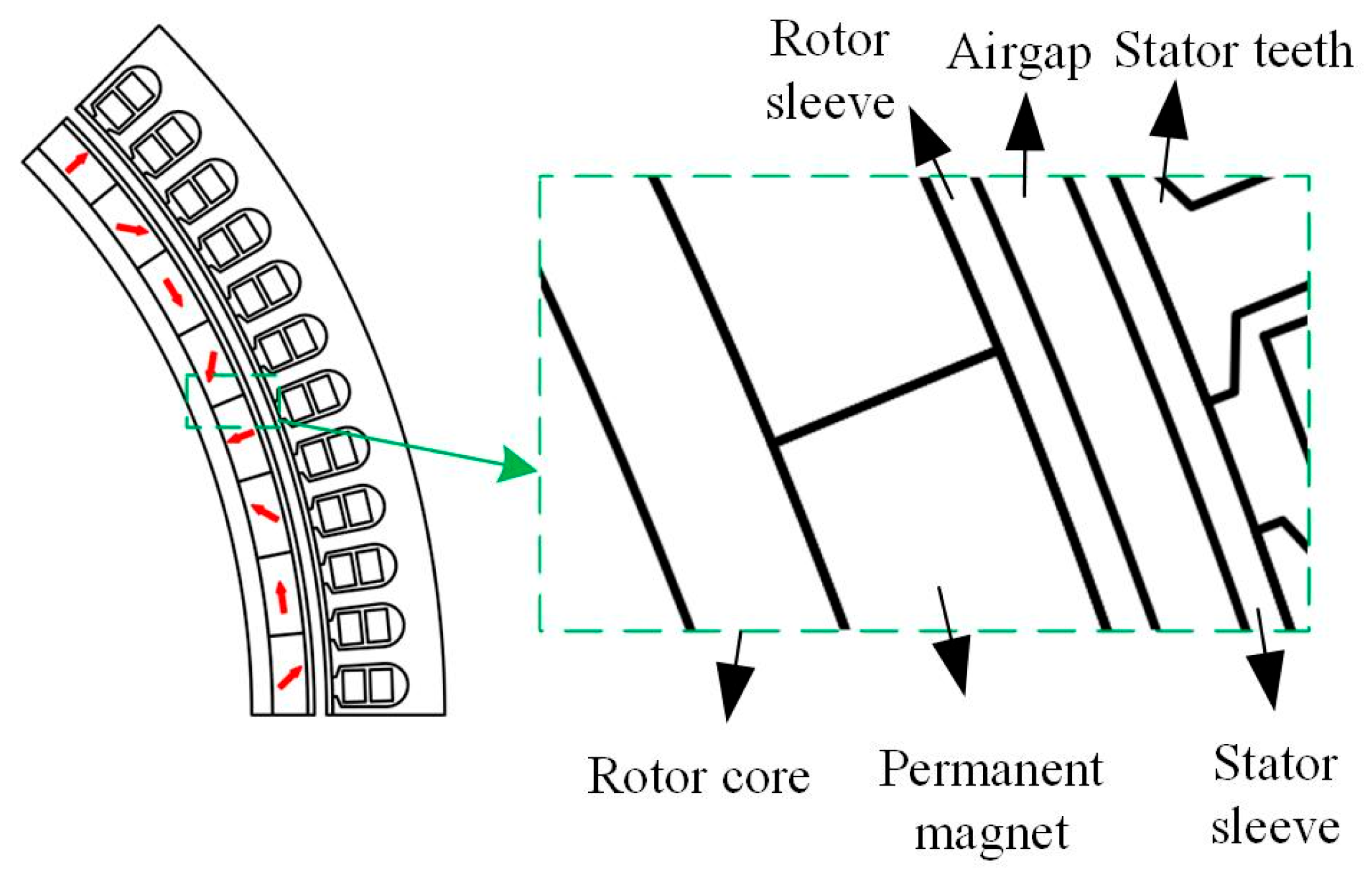

To evaluate TMC’s advantages of TMC as a stator sleeve material, a coupled structural-electromagnetic analysis of an underwater shaftless motor under both no-load and loaded conditions was conducted. The motor assembly employed dual sleeves: an inner sleeve and an outer sleeve, as shown in

Figure 4, both radially constrained and axially welded to the Ti64 end plates. The outer sleeve was made of conventional Ti64. The inner sleeve features a hybrid construction with a central core of the TMC for eddy current suppression, axially transitioned to pure Ti64 at both ends. This ensures reliable, homogeneous Ti64-to-Ti64 welding at the interfaces with the end plates, thereby avoiding the complications of dissimilar material joining. First, static structural analysis was performed to ensure the mechanical integrity of the sleeve assembly under operational stresses, confirming that the design meets the required safety margin. Subsequently, finite element analysis (FEA) systematically compares the electromagnetic performance of this hybrid design with that of a conventional all-Ti64 baseline, quantifying their impact on eddy current density, eddy current loss, and efficiency.

3.1. Sleeve Structural Design and Stress Analysis

As shown in

Figure 5, the manufacturing workflow is initiated with outer sleeve preparation using a high-resistivity Ti64 alloy formed through either sheet rolling or forged billet machining. The outer sleeve subsequently underwent thermal shrinkage fitting with the laminated stator core under a controlled temperature differential.

The inner sleeve fabrication involves the following:

- (1)

Manufacturing a SiC fiber-reinforced Titanium Matrix Composite (TMC) core in stator core contact zone.

- (2)

Precision cladding with Ti64 layers.

- (3)

Final dimensional calibration through grinding.

Critically, the TMC sleeve maintained a fiber-free pure Ti64 zone at the welding interface, ensuring homogeneous Ti64-to-Ti64 welding without dissimilar metal welding complications.

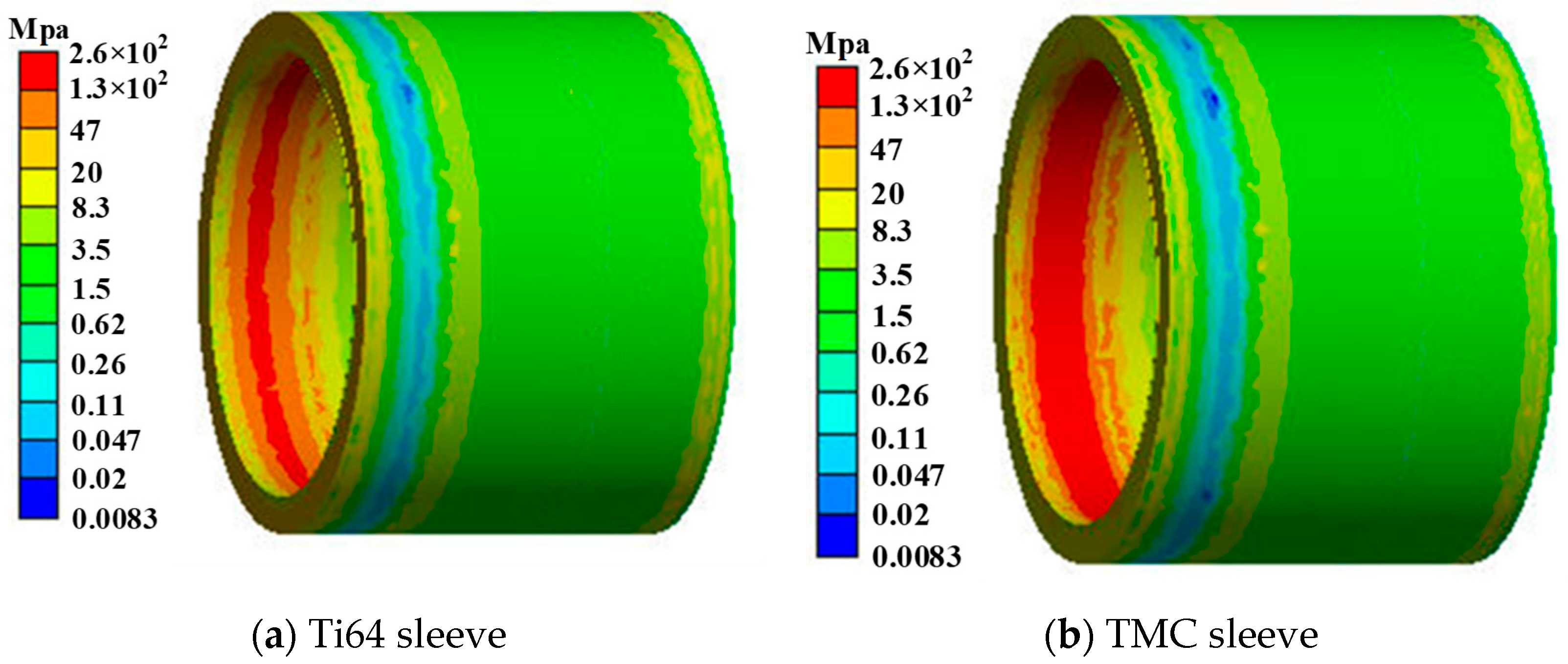

To evaluate the mechanical stress of the stator sleeve under simulated underwater service conditions, a static structural model of the sleeve–stator assembly was established. The model incorporated a hydrostatic pressure of 5 MPa, corresponding to the designated pressure test requirement for the stator assembly, in addition to interference fits from the assembly process. Structural simplifications were applied, including the treatment of the stator core as an isotropic continuum and the omission of secondary components such as windings and insulation. Using this approach, a comparative analysis of stress and deformation was performed between TMC and Ti64 sleeves.

Figure 6 shows the stress distributions of the two sleeves under identical loading conditions. The results indicate that the maximum stress in both designs was located at the end regions and reached a comparable value of approximately 260 MPa. As summarized in

Table 1, the tensile strengths of Ti64 and TMC far exceeded this stress level, confirming that both sleeve configurations satisfied the mechanical strength requirements with substantial safety margins. Furthermore, the lower density of TMC compared to that of Ti64 provides an additional advantage of weight reduction, enhancing the potential for improved system efficiency and power density. This establishes that the TMC sleeve is a structurally viable and functionally superior alternative.

3.2. Electromagnetic Analysis

3.2.1. Electromagnetic Modeling Framework

The electromagnetic analysis is based on Maxwell’s equations, which govern all macroscopic electromagnetic phenomena. For the low-frequency (quasi-static) conditions relevant to motor operation, where displacement currents are negligible, the governing equations reduce to the following:

where

H is the magnetic field intensity,

J is the total current density (including source current

Js and induced eddy current

Je),

E is the electric field intensity, and

B is the magnetic flux density. The constitutive relations

B =

μH and

J =

σE couple these fields to the material properties. The key modeling assumptions and setups include the following:

- (1)

Material Properties: The laminated cores are modeled with nonlinear B-H curves. The stator sleeve is the primary variable, modeled as either isotropic (Ti64) or orthotropic (TMC). For TMC, the conductivity tensor is defined in a cylindrical coordinate system aligned with the sleeve: σϕ = σ// (circumferential), σr = σz = σ⊥ (radial and axial).

- (2)

Boundary Conditions: A magnetic flux parallel condition is applied on the outer boundary.

- (3)

Geometry and Domain Extension: To accurately capture the significant end effects in the short-length motor, the 3D FEM model includes an extended geometry for the stator sleeve. The sleeve is modeled with an axial length of 146.5 mm, which includes a 40 mm extension beyond each end of the active core region (66.5 mm). This extension allows for the proper formation and decay of the 3D eddy current paths at the sleeve ends, which is critical for loss calculation.

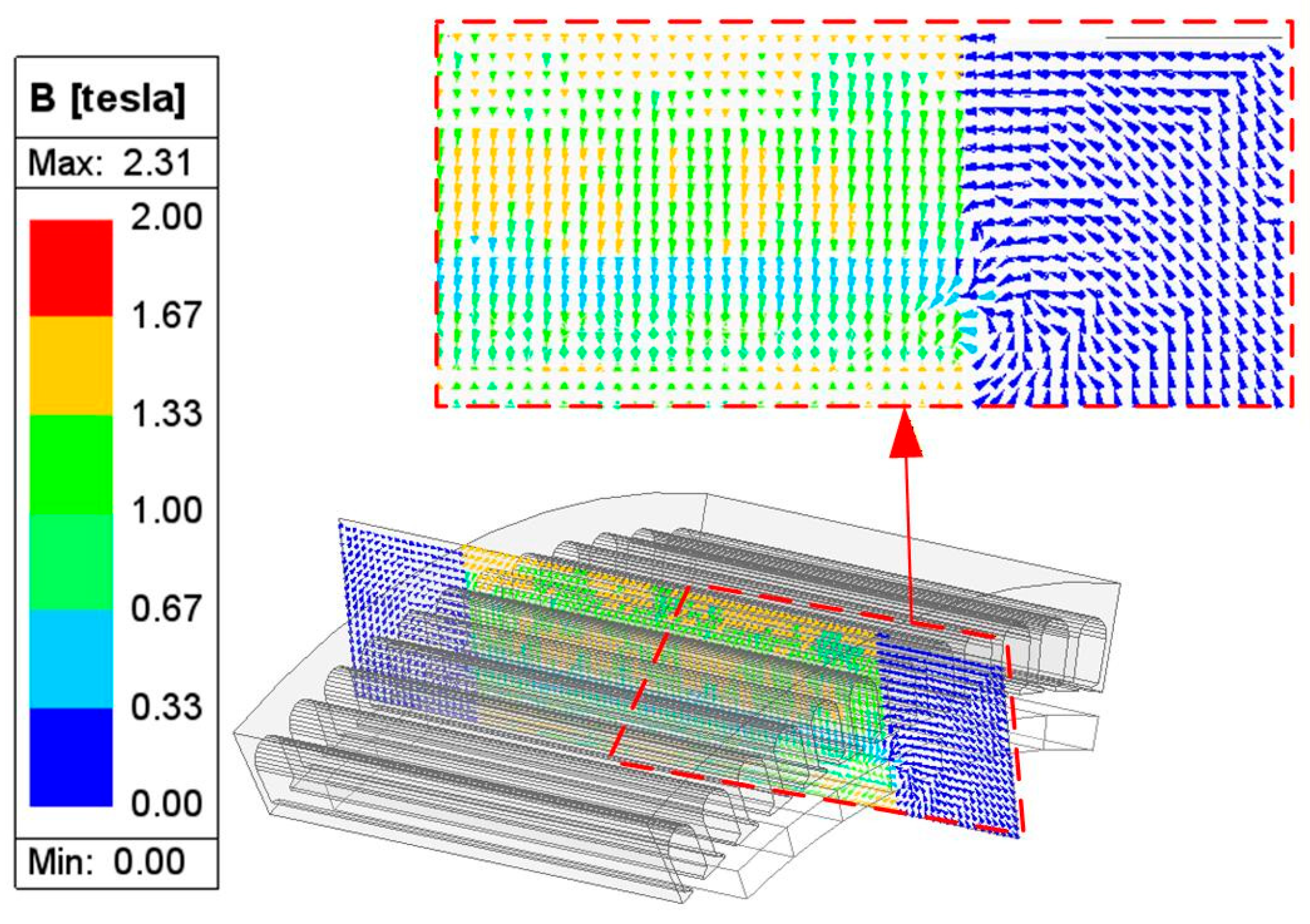

The main parameters of the motors are listed in

Table 2, and the 2D electromagnetic FEM model is illustrated in

Figure 7. A notable characteristic of the motor is its stringent radial dimension constraint, featuring an extremely thin radial thickness, which results in a highly compact structural design. Consequently, the permanent magnets are arranged in a Halbach array to optimize the magnetic flux density distribution, thereby efficiently utilizing the available space for the stator and rotor sleeves, as well as the stator core. Additionally, the motor employs a dual six-phase winding configuration that disperses power across more phases, thereby reducing the power that each inverter bridge arm must handle. The stator sleeve was implemented with TMC material, enabling a direct performance comparison with the Ti64 sleeves.

Given the short axial length (66.5 mm relative to a 235 mm diameter), the end effects are significant and cannot be neglected. To accurately model the orthotropic conductivity of the TMC sleeve and capture its effects, a 3D FEM model was established. In the 3D model, the TMC sleeve was assigned orthotropic conductivity. The high-conductivity direction (σ//) was set circumferentially along the fiber orientation, whereas the low-conductivity directions (σ⊥) were assigned radially and axially. This setup correctly represented the high resistance of the dominant circumferential eddy current path. A 2D model was used for the context and comparison. The anisotropic behavior was approximated in 2D by performing two separate simulations with extreme isotropic conductivity values, σ⊥ and σ//), providing a performance range.

3.2.2. No-Load Simulation Analysis

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 illustrate the axial magnetic flux density distribution and eddy current distribution on the stator sleeve, respectively, under the no-load condition at 2900 rpm. To accurately capture end effects, the stator sleeve was axially extended by 40 mm at both ends of the simulation model. The magnetic flux density distribution exhibits a characteristic pattern: the magnitude is relatively uniform and high across the central region corresponding to the active core length. However, it shows a pronounced decay towards both axial ends of the sleeve extension. The decay is due to the absence of the high-permeability stator core beyond the active region, which results in a significant fringing or leakage field at the ends. The fringing field is not only weaker but also changes its spatial orientation compared to the primarily radial field in the central part.

The resulting eddy current distribution (

Figure 9) directly correlates with this magnetic field pattern. It reveals a distinct axial gradient in magnitude, with the highest density localized in the central region and a pronounced decrease towards both ends. The intensity distribution corresponds to a shift in the current flow pattern: the strong, uniform central field drives high-density axial currents, whereas the weaker, fringing end fields promote the formation of lower-density circumferential current loops to close the current path. To achieve a reliable prediction, it is essential to account for the material’s orthotropic nature by considering both the conductivity along (σ

//) and perpendicular (σ

⊥) to the fiber direction.

The eddy current in the stator sleeve originated from Faraday’s law of induction. The time-varying magnetic field

B induces a circulating electric field

E, governed by the following:

The electric field drives eddy current density

J within the sleeve, as described by Ohm’s law:

where

σ is the electrical conductivity.

The resulting power dissipation was calculated using Joule’s law. The eddy current loss

P is given by the following:

The derivation establishes that the loss is proportional to the square of the induced current density and the sleeve resistivity (1/

σ), thereby providing a theoretical foundation for the significant loss reduction observed in high-resistivity TMC sleeves.

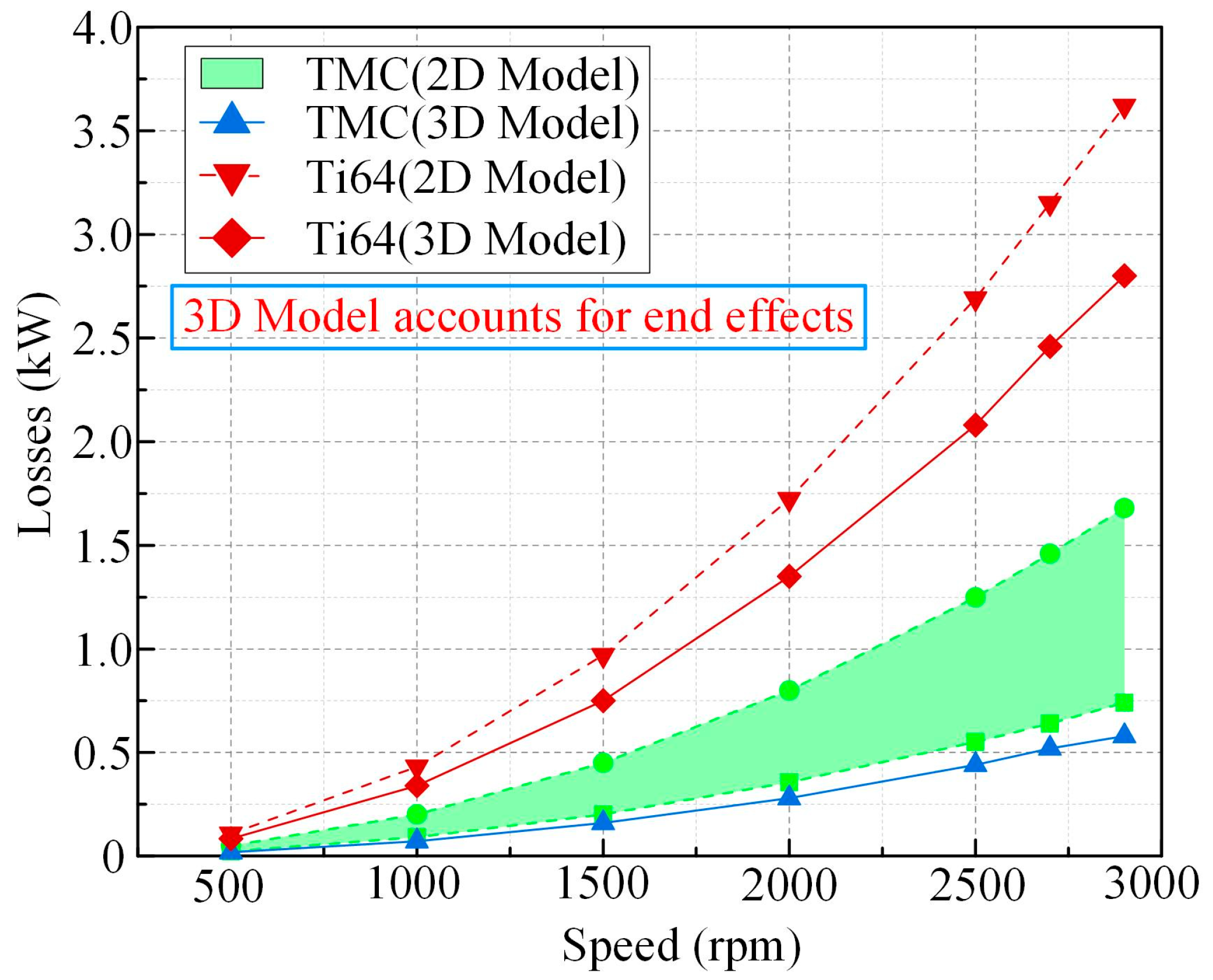

Figure 10 compares the no-load eddy current losses obtained from both 2D and 3D simulations for the Ti64 and TMC stator sleeves. The results quantitatively validate the advantage of the TMC material over conventional Ti64. In the 2D simulation, the TMC sleeve achieved a notable loss reduction ranging from 54.8% to 80.4% compared to the Ti64 baseline, reflecting the bounded prediction owing to the anisotropic conductivity. More accurately, in the 3D simulation, which fully captures the orthotropic behavior and end effects of the material, the TMC sleeve demonstrates a more significant loss reduction of 78.94%. This value falls within the range predicted by the 2D model and confirms the key role of the directional conductivity in suppressing eddy currents. Furthermore, a quadratic dependence of the eddy current loss on the excitation frequency was consistently observed across both simulation methods. This frequency-dependent behavior results in progressively increasing absolute loss savings at higher rotational speeds, conclusively establishing the superiority of TMC sleeves in high-speed applications where eddy current losses dominate.

3.2.3. Loaded Simulation Analysis

The load torque applied to the motor was determined through steady-state computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations of the integrated pump-jet propulsion system. The simulations solved the incompressible Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) equations using the SST k-ω turbulence model to characterize the hydrodynamic performance across the AUV’s operating speed range. A mesh independence study was conducted, confirming that the predicted propeller torque varied by less than 2% upon further grid refinement, ensuring the reliability of the load data. Correlations among the vehicle speed, propeller inlet flow rate, and rotational speed were established. The numerically calculated propeller torque was then applied as the mechanical load boundary condition in the subsequent electromagnetic simulation. The AUV speed and the corresponding propeller torque at different motor speeds are listed in

Table 3.

The torque obtained from the CFD was applied as the mechanical load boundary condition for the subsequent electromagnetic FEA simulation.

The motor efficiency (

ηem) reported in the following comparison is calculated as the ratio of the mechanical output power to the total electromagnetic input power:

where

Pout is the output power, derived from the output torque and speed,

Pcu is the copper loss,

Pfe is the stator and rotor core loss,

Peddy is the eddy current loss, and

Pm is the mechanical loss.

Table 4 presents a comprehensive comparison of the performances of the Ti64 and TMC sleeves at three characteristic operating speeds (1500, 2000, and 2829 rpm). Because the same load torque was applied to all configurations for a fair comparison, the observed performance differences stemmed directly from the electromagnetic properties of the sleeve materials. Both the configurations exhibited equivalent iron and mechanical losses. The stator core loss was obtained from FEA simulations and adjusted with a non-sinusoidal excitation factor, whereas the mechanical loss was estimated to be 1% of the output power. The results confirm that although the output torque is identical across all configurations, the TMC sleeve demonstrates a substantial advantage in terms of efficiency and loss reduction. This improvement was primarily attributed to the markedly lower eddy current losses in the TMC sleeve owing to its higher electrical resistivity. This significant reduction in losses translates directly into notable improvements in efficiency.

A comparison of the total loss and efficiency predicted by the 2D and 3D models provides further insight. The total loss predicted by the 3D model was slightly lower than that of the 2D model for the same configuration, which is attributed to the 3D model’s more accurate representation of end effects. In the 2D approximation for the anisotropic TMC sleeve, the total losses were bounded between two extreme isotropic conductivity cases (TMC_lower_2D and TMC_upper_2D), defining a performance envelope. Both of these boundary cases exhibited significantly lower losses than the Ti64 benchmarks. Crucially, the results from the more accurate 3D TMC simulation fell within this predicted 2D range, validating the bounding approach. Consequently, the motor efficiency calculated using the 3D model was marginally higher than the 2D result for Ti64, while for TMC, the 3D result resided within the pronounced high-efficiency band defined by the 2D model. Across the operational speed range, the performance advantage of the TMC sleeve became more pronounced at higher speeds. Compared to the Ti64 baseline in 3D simulations, the TMC sleeve achieved a substantial efficiency improvement of 5.8–8.5%.

4. Prototype Test

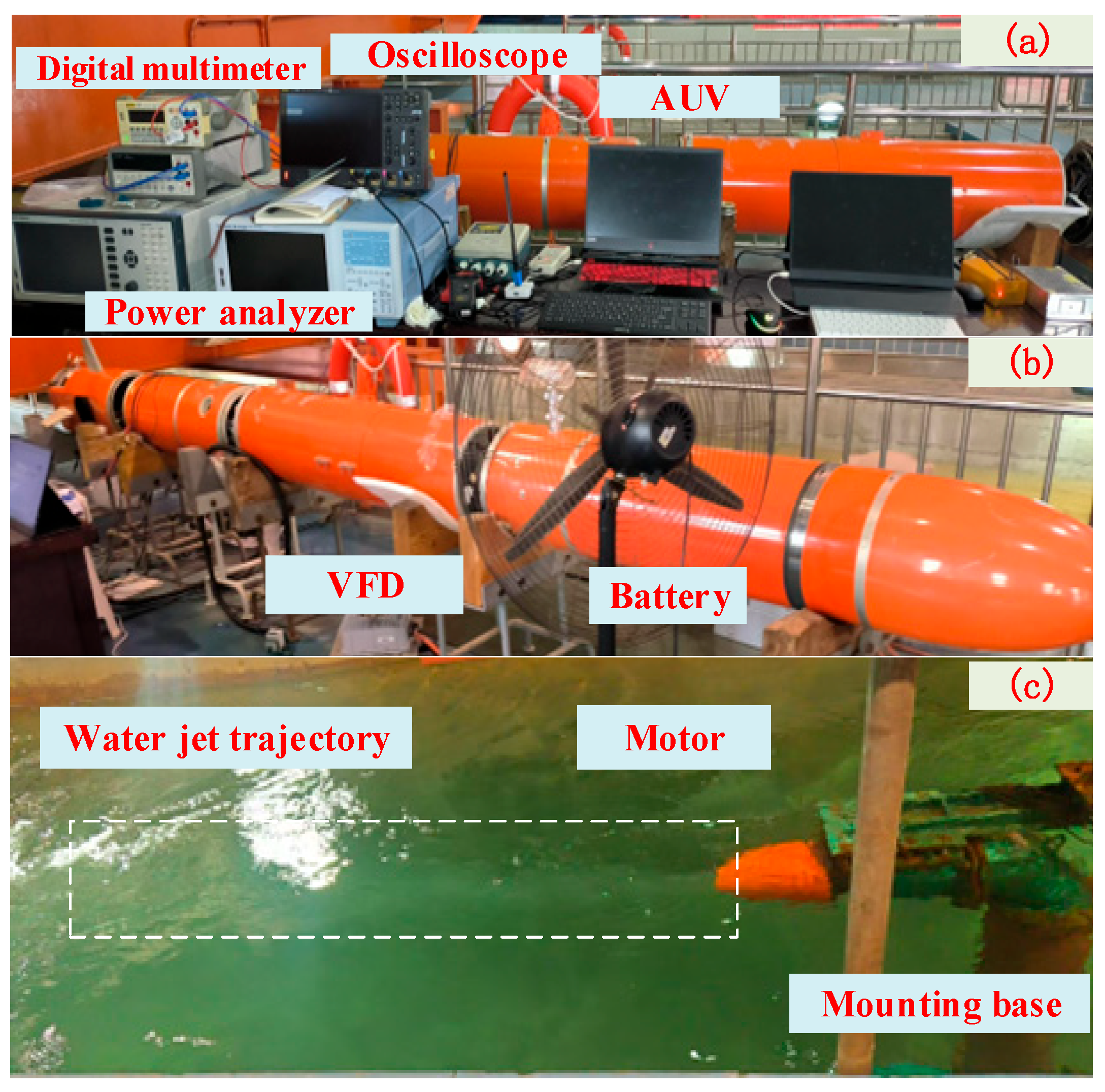

To validate the simulation results, an experimental platform was established to evaluate the motor performance, as illustrated in

Figure 11. The shaftless motor is directly coupled to the pipeline system, with a centrifugal circulation pump installed upstream. The pump speed was precisely regulated to maintain a constant volumetric flow rate to the propeller, ensuring stable hydrodynamic performance under various operating conditions.

The motor performance was measured by a synchronized acquisition system. Input voltage, current, and power were acquired by a Zimmer ZMS WT5000 power (Zimmer Group, Vienna, Austria) analyzer (basic power accuracy: ±0.04%). Temperatures at key points were measured using PT1000 sensors, with signals acquired by a RIGOL DM3058 digital multimeter (RIGOL Technologies, Beijing, China). All instruments were hardware-synchronized. This setup ensures electrical measurement accuracy better than 0.1% and temperature accuracy better than 0.5 °C, providing a reliable benchmark for simulation validation.

Owing to the inherent design constraints of the shaftless propulsion system that prevent direct torque measurement, the evaluation was conducted under constant-speed conditions. The output power can be considered equivalent at identical rotational speeds and flow rates, enabling a comparative analysis of the effects of sleeve material on motor efficiency through input power measurements. Comprehensive performance testing was performed across a rotational speed range of 500–2700 rpm, covering both the typical operating points and extreme conditions. It should be noted that although the design maximum speed is 2829 rpm, the motor could not reach this speed during actual testing due to limitations in the battery voltage.

Table 5 presents a comparative analysis of the input power between the Ti64 and TMC sleeves, integrating the experimental and simulation results. Experimental measurements confirmed the consistent advantage of TMC sleeves, which require 3.5–5.7% lower input power than the Ti64 baseline across the tested speed range. However, all the simulation models systematically underestimated the input power compared with the experimental data for both materials. For the Ti64 sleeve, the 3D simulation errors ranged from 5.98% to 27.05%, whereas the 2D model errors ranged from 5.63% to 24.43%. For the TMC sleeve, the 3D simulation errors ranged from 10.45% to 29.64%, while the 2D model predicted a bounded error range of 8.15–29.76%. Despite these absolute discrepancies, both 2D and 3D simulations correctly captured the relative performance trend, with TMC sleeves consistently showing lower input power requirements than Ti64. The close agreement between the 2D and 3D simulation results further validated the modeling consistency.

5. Discussion

5.1. Analysis of Simulation–Experiment Discrepancies

The measured efficiency of both prototypes was lower than the initial design predictions, and the performance advantage of the TMC-sleeved motor, although clear, was less pronounced than anticipated. These discrepancies are primarily attributed to two practical factors encountered during prototype implementation, as summarized in

Table 6.

- (1)

Post-fabrication measurements confirmed deviations in the critical dimensions from the design specifications. The manufactured protective sleeves for both motor variants exhibited greater thicknesses than those originally designed. The direct consequence of this effect is elevated eddy current losses in both the Ti64 and TMC sleeves compared with the initial simulations.

- (2)

The sensorless control strategy requires d-axis current injection for rotor position estimation. This non-torque-producing current increases the current magnitude, elevating both copper losses and core losses owing to the enhanced magnetic field. These additional losses, present in both motor configurations, contribute to the efficiency gap between the predicted and measured performance.

While the inherently high resistivity of the TMC material effectively reduces its absolute eddy current loss, the relative performance advantage of the TMC-sleeved motor appears less pronounced in experimental measurements because of the presence of these additional system-level loss mechanisms that affect both motor configurations.

5.2. Validation with Updated Models

Table 7 details the discrepancies between the simulated and experimental input powers for both the Ti64 and TMC sleeves under the updated modeling conditions. For the Ti64 sleeve, both the 2D and 3D simulations demonstrated high accuracy. The 2D model errors ranged from 0.62% to 2.16%, while the 3D simulation errors ranged from 1.22% to 5.23% across the speed range. Regarding the TMC sleeve, the 3D simulation maintains excellent agreement with the experiments, showing errors between 0.83% and 2.66%. The bounded predictions from the 2D anisotropic model successfully encapsulated the experimental data points, with errors ranging from 0.03% to 5.06% across the operating range. The overall errors are contained within a 5.3% margin, confirming a significant improvement in model accuracy and validating the updated simulation methodology. The simulation approaches correctly captured the relative performance advantage of TMC sleeves over Ti64 across all operating conditions.

5.3. Practical Considerations and Future Outlook

While this study demonstrates the significant electromagnetic performance benefits of TMC sleeves, a balanced assessment must also consider practical challenges associated with their adoption:

Elevated Manufacturing Cost and Complexity: The process of manufacturing TMC sleeves with controlled fiber alignment (e.g., via hot isostatic pressing) is inherently more complex and costly than machining conventional Ti64 billets. This includes higher raw material costs and specialized processing, which could impact the economic viability for high-volume production.

Demand for Advanced Manufacturing and Post-Processing: Critical steps such as sleeve sizing, shaping, and final dimensional calibration become more challenging and less forgiving, potentially necessitating the development or adaptation of specialized tooling and updated process guidelines to achieve the required precision and yield.

Sensitivity to Processing and Anisotropy Control: The electromagnetic performance is highly dependent on achieving the desired fiber orientation and distribution. Furthermore, other performance aspects, such as potential thermal conductivity, would also be highly sensitive to the fiber–matrix architecture and interfacial quality. Process variations could therefore lead to inconsistencies in multiple anisotropic properties, affecting performance predictability and necessitating stringent in-process quality control measures.

Long-Term Reliability Data Gap: While the structural analysis confirms static strength, the long-term thermomechanical fatigue performance of the fiber–matrix interface under the combined effects of thermal cycling, electromagnetic forces, and corrosion in marine environments remains an area for future investigation.

Furthermore, the material’s superior thermal conductivity (10 W·m−1·K−1 versus approximately 6 W·m−1·K−1 for Ti64) enables efficient heat dissipation in passive cooling environments—a crucial advantage for underwater applications.

6. Conclusions

This study systematically evaluated Titanium Matrix Composite (TMC) as a stator sleeve material for underwater shaftless motors. The core experimentally verified findings confirm that TMC sleeves consistently reduce motor input power by 3.5–5.7% compared to conventional Ti64 sleeves under equivalent output conditions. This practical advantage is primarily attributed to the material’s tailored anisotropic conductivity, which measurably suppresses eddy currents. Furthermore, by incorporating actual manufacturing and control parameters, the simulation model was refined and validated, achieving a prediction accuracy with errors below 5.3% and establishing a reliable framework for performance prediction.

Electromagnetic simulations based on the validated model predict that, by leveraging its anisotropic properties, TMC has the potential to achieve 5.01–8.17% higher motor efficiency and 53.5–79.8% lower eddy current losses than Ti64 across the operational speed range. The initial TMC sleeve also demonstrated structural viability, withstanding the required mechanical loads with a substantial safety margin.

Collectively, these results establish TMC as a strong candidate and a functionally superior alternative to conventional titanium alloys for demanding applications such as canned motors, where an optimal balance between electromagnetic performance, structural integrity, and manufacturing feasibility is critical. Future work should focus on developing cost-effective manufacturing processes for TMC sleeves, validating their long-term reliability under operational conditions, and exploring their optimal integration into broader motor and propulsion system designs.