Toxic Effect of UV-Pre-Irradiated TiO2 Nanoparticles on the Sand Dollar Scaphechinus mirabilis Sperm

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Experiment

2.1.1. Animal Collection

2.1.2. Experimental Design

2.1.3. NP Solution Preparation

2.2. Fertilization Assay

2.3. Resazurin Cytotoxicity Assay

2.4. Determination of Concentration of Malondialdehyde

2.5. Comet Assay

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

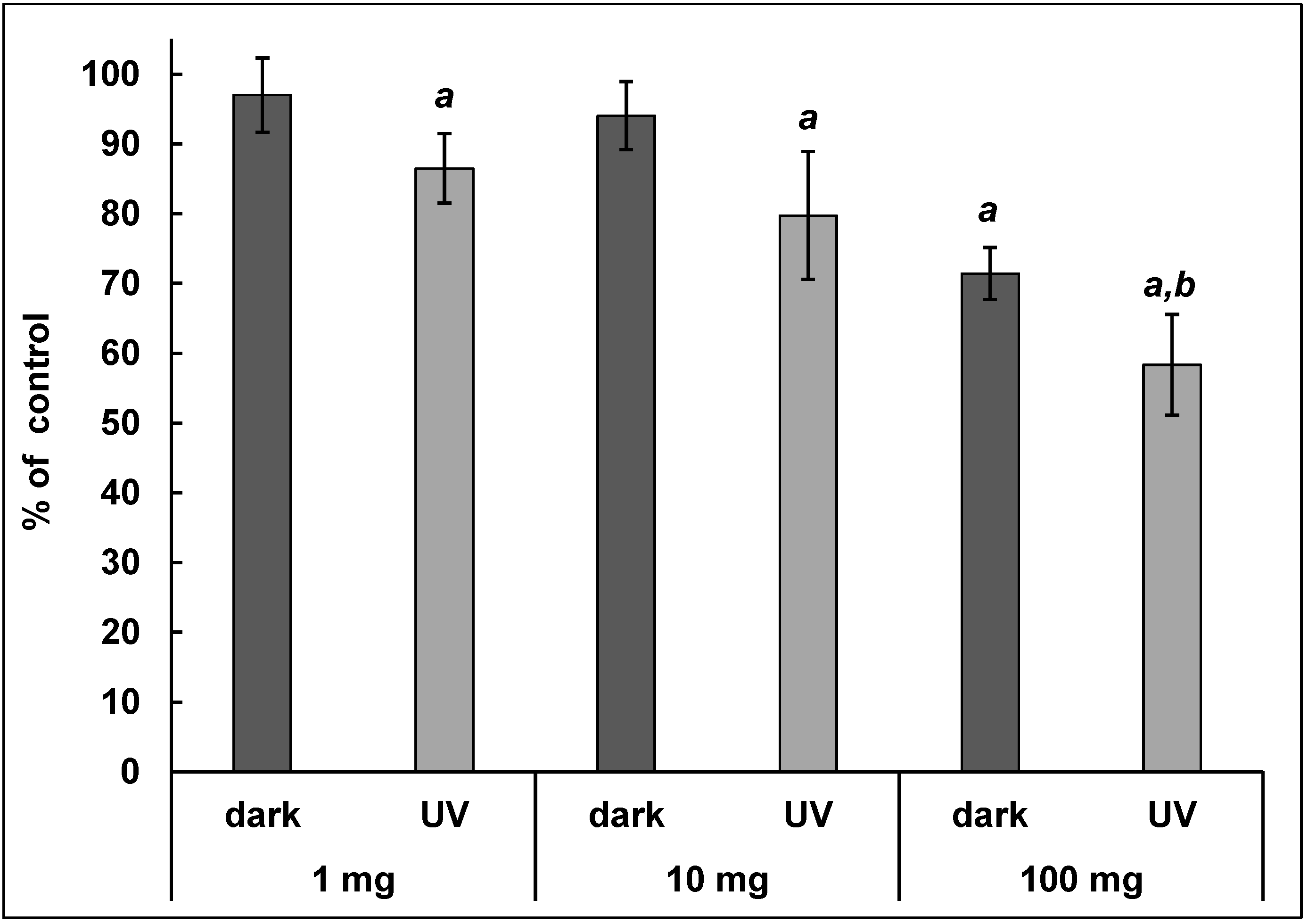

3.1. Resazurin Test

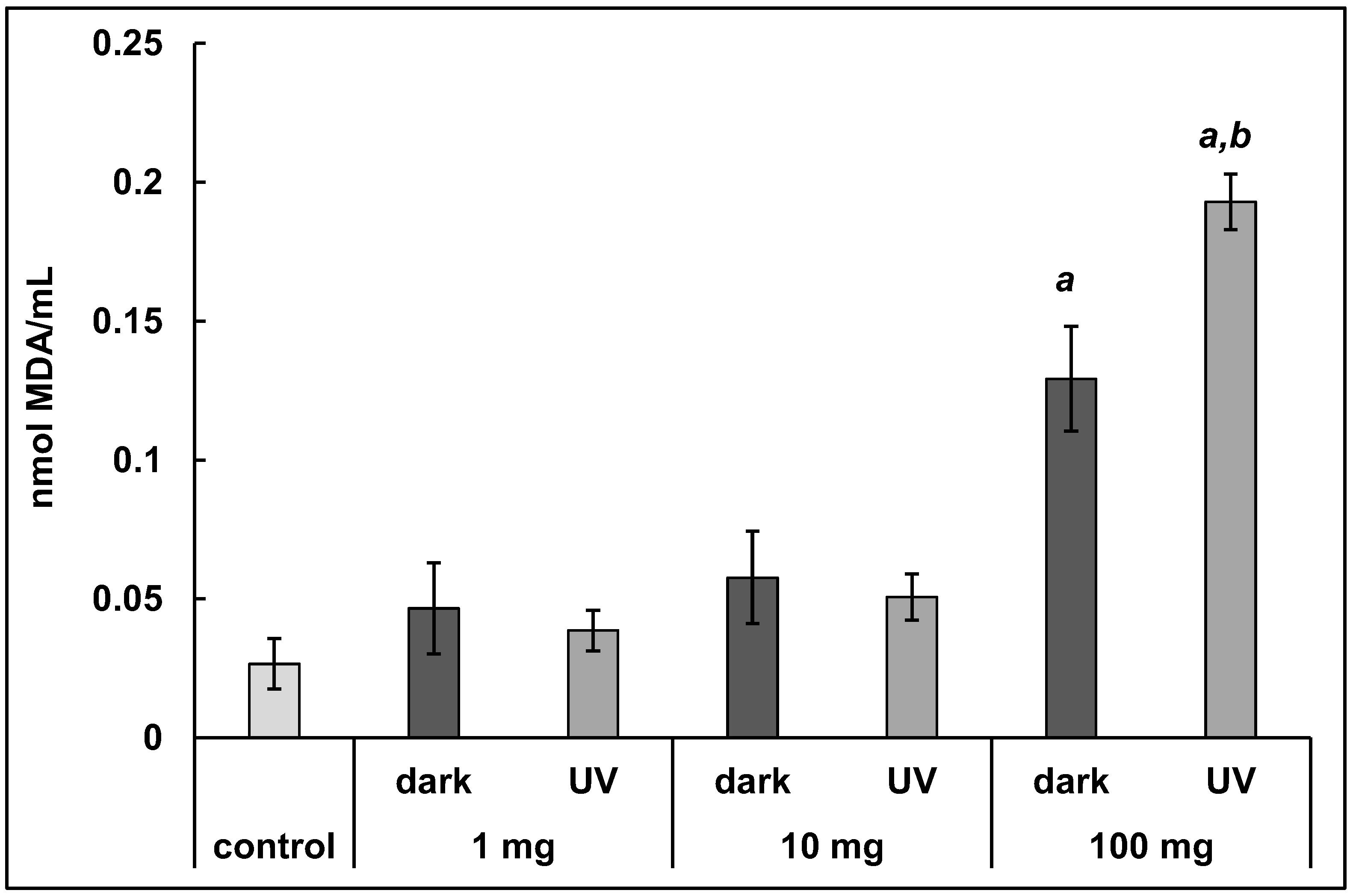

3.2. Concentration of Malondialdehyde

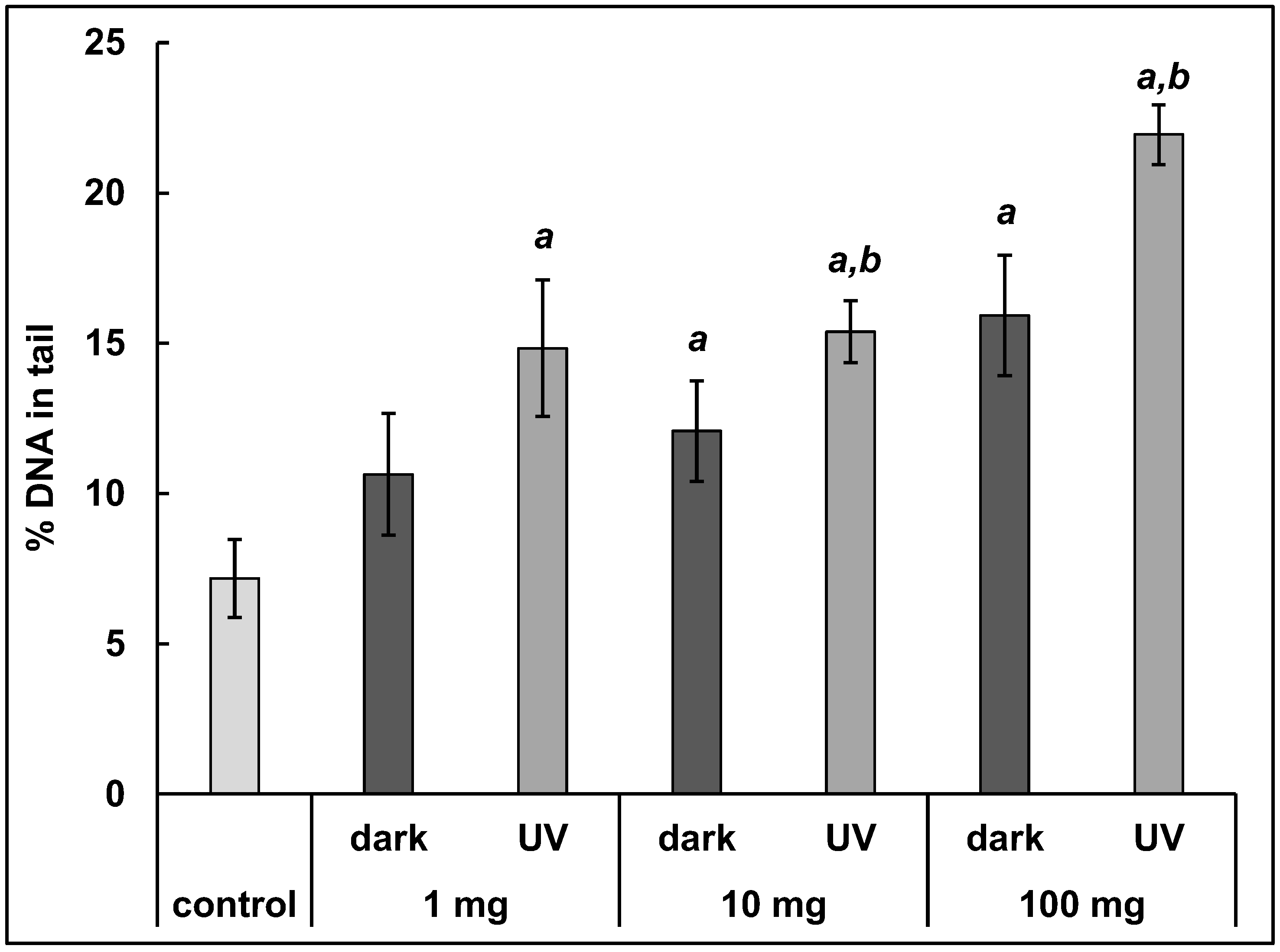

3.3. DNA Damage

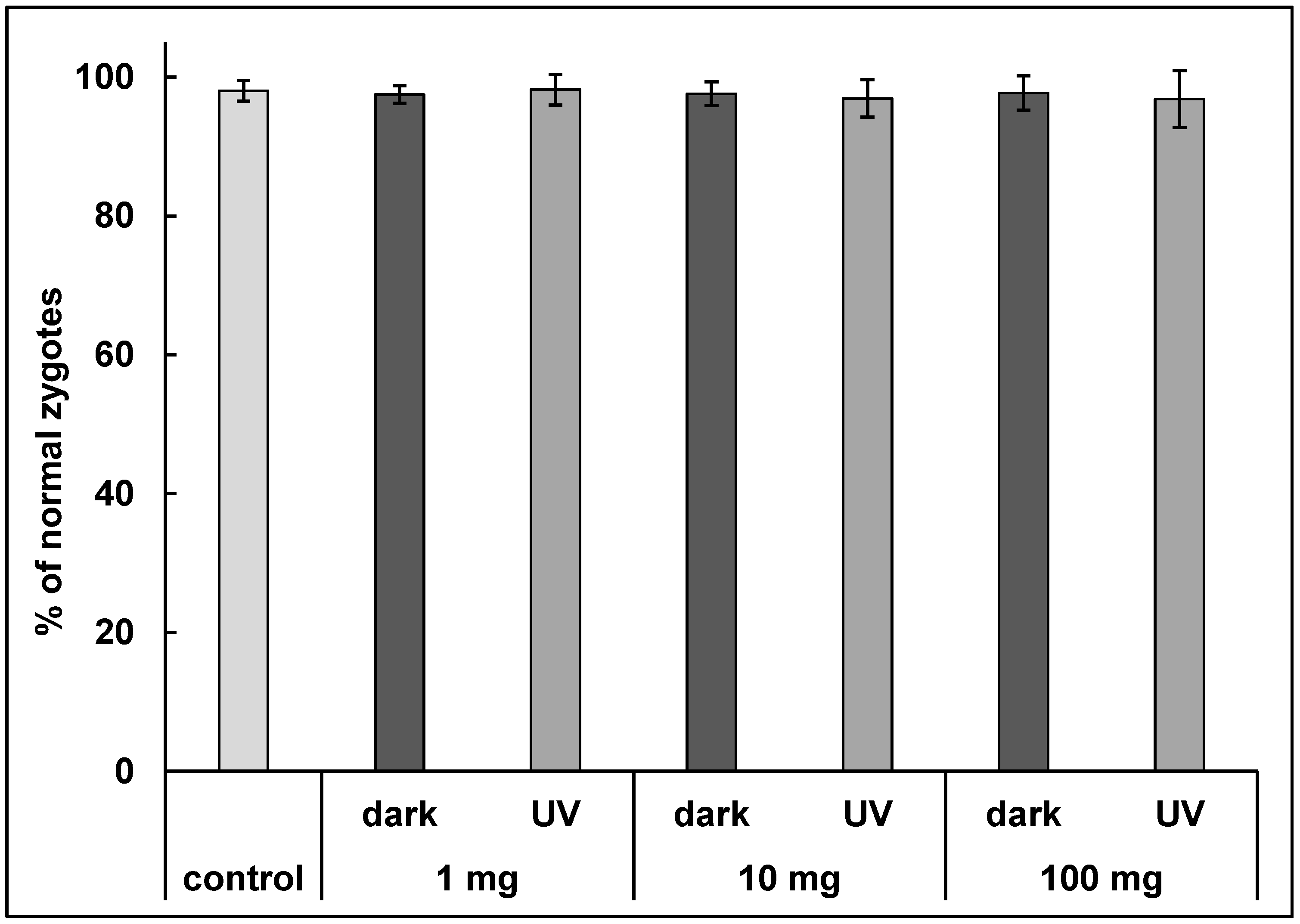

3.4. Fertilization Assay

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sundaram, T.; Rajendran, S.; Natarajan, S.; Vinayagam, S.; Rajamohan, R.; Lackner, M. Environmental fate and transformation of TiO2 nanoparticles: A comprehensive assessment. Alex. Eng. J. 2025, 115, 264–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaegi, R.; Ulrich, A.; Sinnet, B. Synthetic TiO2 nanoparticle emission from exterior facades into the aquatic environment. Environ. Pollut. 2008, 156, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondikas, A.P.; von der Kammer, F.; Reed, R.B.; Wagner, S.; Ranville, J.F.; Hofmann, T. Release of TiO2 nanoparticles from sunscreens into surface waters: A one-year survey at the old Danube recreational Lake. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 5415–5422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Han, Y.; Guo, C.; Su, W.; Zhao, X.; Zha, S.; Wang, Y.; Liu, G. Ocean acidification increases the accumulation of titanium dioxide nanoparticles (nTiO2) in edible bivalve mollusks and poses a potential threat to seafood safety. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 3516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casella, C.; Dondi, D.; Vadivel, D. Do microplastics (MPs) and nanoplastics (NPs) directly contribute to human carcinogenesis? Environ. Pollut. 2026, 388, 127343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loosli, F.; Wang, J.; Rothenberg, S. Sewage spills are a major source of titanium dioxide engineered (nano)-particles into the environment. Environ. Sci. Nano 2019, 6, 763–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, I.C.; Mendes, V.A.S.; Duarte, I.D.; Rocha, L.D.; Azevedo, V.C.; Matsumoto, S.T.; Elliott, M.; Wunderlin, D.A.; Monferrán, M.V.; Fernandes, M.N. Nanoparticle transport and sequestration: Intracellular titanium dioxide nanoparticles in a neotropical fish. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 658, 798–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kalliny, A.S.; Abdel-Wahed, M.S.; El-Zahhar, A.A. Nanomaterials: A review of emerging contaminants with potential health or environmental impact. Discover Nano 2023, 18, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumah, E.A.; Fopa, R.D.; Harati, S.; Boadu, P.; Zohoori, F.; Pak, T. Human and environmental impacts of nanoparticles: A scoping review of the current literature. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Jamil, N.; Yasir, M.; Kanwal, Q.; Kamran, M.; Aslam, A.; Mehdi, M.; Akhtar, H.; Ahmed, M. Toxicity of nanomaterials in the environment: A critical review of current understanding and future directions. J. Nanopart. Res. 2025, 27, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, X.; Hoang, S.A.; Bolan, N.S.; Kirkham, M.B.; Liu, J.; Xia, X.; Li, Y. Silver nanoparticles in aquatic sediments: Occurrence, chemical transformations, toxicity, and analytical methods. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 418, 126368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marefat, A.; Karbassi, A.; Aghabarari, B. TiO2 nanoparticles in aquatic environments: Impact on heavy metals distribution in sediments and overlying water. Acta Geochim. 2022, 41, 968–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slomberg, D.L.; Catalano, R.; Bartolomei, V.; Labille, J. Release and fate of nanoparticulate TiO2 UV filters from sunscreen: Effects of particle coating and formulation type. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 271, 116263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parashar, S.; Raj, S.; Srivastava, P.; Singh, A.K. Comparative toxicity assessment of selected nanoparticles using different experimental model organisms. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 2024, 130, 107563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Zhang, T.; Tang, M. Toxicity mechanism of engineered nanomaterials: Focus on mitochondria. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 343, 123231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rengifo-Herrera, J.A.; Pulgarin, C. Why five decades of massive research on heterogeneous photocatalysis, especially on TiO2, has not yet driven to water disinfection and detoxification applications? Critical review of drawbacks and challenges. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 477, 146875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnajady, M.A.; Modirshahla, N.; Shokri, M.; Elham, H.; Zeininezhad, A. The effect of particle size and crystal structure of titanium dioxide nanoparticles on the photocatalytic properties. J. Environ. Sci. Health A 2008, 43, 460–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Hamzeh, M.; Dodard, S.; Zhao, Y.; Sunahara, G. Effects of TiO2 nanoparticles on ROS production and growth inhibition using freshwater green algae pre-exposed to UV irradiation. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2015, 39, 1074–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cupi, D.; Hartmann, N.B.; Baun, A. Influence of pH and media composition on suspension stability of silver, zinc oxide, and titanium dioxide nanoparticles and immobilization of Daphnia magna under guideline testing conditions. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2016, 127, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moezzi, S.A.; Khoei, A.J. Interaction of water salinity and titanium dioxide nanoparticle (TiO2) exposure in the Pacific oyster, Crassostrea gigas: Immune and antioxidant system responses. Toxin Rev. 2024, 43, 358–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nthunya, L.N.; Mosai, A.K.; López-Maldonado, E.A.; Bopape, M.; Dhibar, S.; Nuapia, Y.; Ajiboye, T.O.; Buledi, J.A.; Solangi, A.R.; Sherazi, S.T.H.; et al. Unseen threats in aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems: Nanoparticle persistence, transport and toxicity in natural environments. Chemosphere 2025, 382, 144470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, C.; Zhang, S.; Liu, H.; Li, S.; Wang, X. Toxicity and mechanisms of action of titanium dioxide nanoparticles in living organisms. J. Environ. Sci. 2019, 75, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunet, L.; Lyon, D.Y.; Hotze, E.M.; Alvarez, P.J.J.; Mark, R. Wiesner Comparative Photoactivity and Antibacterial Properties of C60 Fullerenes and Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 4355–4360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haynes, V.N.; Ward, J.E. The interactive effects of titanium dioxide nanoparticles and light on heterotrophic bacteria and microalgae associated with marine aggregates in nearshore waters. Mar. Environ. Res. 2020, 161, 105146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambardella, C.; Marcellini, F.; Falugi, C.; Varrella, S.; Corinaldesi, C. Early-stage anomalies in the sea urchin (Paracentrotus lividus) as bioindicators of multiple stressors in the marine environment: Overview and future perspectives. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 287, 117608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burić, P.; Kovačić, I.; Ilić, K.; Šižgorić Winter, D.; Buršić, M. A decade of toxicity research on sea urchins: A review. Toxicon 2025, 264, 108420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, N. Marine pollution bioassay by sea urcin eggs, an attempt to enhance accuracy. Publ. Seto Mar. Biol. Lab. 1985, 30, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biological Test Method: Fertilization Assay Using Echinoids (Sea Urchins and Sand Dollars); EPS 1/RM/27; Environment Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2011; Available online: https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2011/ec/En49-7-1-27-eng.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Pikula, K.; Zakharenko, A.; Chaika, V.; Em, I.; Nikitina, A.; Avtomonov, E.; Tregubenko, A.; Agoshkov, A.; Mishakov, I.; Kuznetsov, V.; et al. Toxicity of carbon, silicon, and metal-based nanoparticles to sea urchin Strongylocentrotus intermedius. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukla, S.; Slobodskova, V.; Mazur, A.; Chelomin, V.; Kamenev, Y. Genotoxic Testing of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles in Far Eastern Mussels, Mytilus trossulus. Pollution 2021, 7, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czekanska, E.M. Assessment of cell proliferation with resazurin-based fluorescent dye. Methods Mol. Biol. 2011, 740, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buege, J.A.; Aust, S.D. [30]Microsomal lipid peroxidation. Methods Enzymol. 1978, 52, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchelmore, C.L.; Birmelin, C.; Livingstone, D.R.; Chipman, J.K. Detection of DNA strand breaks in isolated mussels (Mytilus edulis) digestive gland cells using the “Comet” assay. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 1998, 41, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzo, S.; Schiavo, S.; Oliviero, M.; Toscano, A.; Ciaravolo, M.; Cirino, P. Immune and reproductive system impairment in adult sea urchin exposed to nanosized ZnO via food. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 599–600, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kukla, S.P.; Slobodskova, V.V.; Zhuravel, E.V.; Mazur, A.A.; Chelomin, V.P. Exposure of adult sand dollars (Scaphechinus mirabilis) (Agassiz, 1864) to copper oxide nanoparticles induces gamete DNA damage. Environ. Scien. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 39451–39460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dose, A.; Kennington, W.J.; Evans, J.P. Effects of rutile titanium dioxide nanoparticles (nTiO2) on reproduction in the broadcast-spawning sea urchin Heliocidaris erythrogramma armigera. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2025, 758, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmeira-Pinto, L.; Emerenciano, A.K.; Bergami, E.; Joviano, W.R.; Rosa, A.R.; Neves, C.L.; Corsi, I.; Marques-Santos, L.F.; Silva, J.R.M.C. Alterations induced by titanium dioxide nanoparticles (nano-TiO2) in fertilization and embryonic and larval development of the tropical sea urchin Lytechinus variegatus. Mar. Environ. Res. 2023, 188, 106016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignoto, S.; Pecoraro, R.; Scalisi, E.M.; Contino, M.; Ferruggia, G.; Indelicato, S.; Brundo, M.V. Spermiotoxicity of nano-TiO2 compounds in the sea urchin Paracentrotus lividus (Lamarck, 1816): Considerations on water remediation. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanovic, B. Review of titanium dioxide nanoparticle phototoxicity: Developing a phototoxicity ratio to correct the endpoint values of toxicity tests. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2015, 34, 1070–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.W.; An, Y.J. Effect of ZnO and TiO2 nanoparticles preilluminated with UVA and UVB light on Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 95, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuvaneshwari, M.; Sagar, B.; Doshi, S.; Chandrasekaran, N.; Mukherjee, A. Comparative study on toxicity of ZnO and TiO2 nanoparticles on Artemia salina: Effect of pre-UV-A and visible light irradiation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2017, 24, 5633–5646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machanlou, M.; Ziaei-Nejad, S.; Johari, S.A.; Banaee, M. Study on the hematological toxicity of Cyprinus carpio exposed to water-soluble fraction of crude oil and TiO2 nanoparticles in the dark and ultraviolet. Chemosphere 2023, 343, 140272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diniz, R.R.; Paiva, J.P.; Aquino, R.M.; Gonçalves, T.C.W.; Leitão, A.C.; Santos, B.A.M.C.; Pinto, A.V.; Leandro, K.C.; de Pádula, M. Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains as bioindicators for titanium dioxide sunscreen photoprotective and photomutagenic assessment. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2019, 198, 111584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petković, J.; Küzma, T.; Rade, K.; Novak, S.; Filipič, M. Pre-irradiation of anatase TiO2 particles with UV enhances their cytotoxic and genotoxic potential in human hepatoma HepG2 cells. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 196, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kose, O.; Tomatis, M.; Turci, F.; Belblidia, N.B.; Hochepied, J.F.; Pourchez, J.; Forest, V. Forest Short Preirradiation of TiO2 Nanoparticles Increases Cytotoxicity on Human Lung Coculture System. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2021, 34, 733–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hund-Rinke, K.; Simon, M. Ecotoxic Effect of Photocatalytic Active Nanoparticles (TiO2) on Algae and Daphnids. Environ. Sci. Poll. Res. Int. 2006, 13, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcone, G.P.; Oliveira, A.C.; Almeida, G.; Umbuzeiro, G.A.; Jardim, W.F. Ecotoxicity of TiO2 to Daphnia similis under irradiation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 211–212, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Pan, X.; Wallis, L.K.; Fan, Z.; Chen, Z.; Diamond, S.A. Comparison of TiO2 nanoparticle and graphene–TiO2 nanoparticle composite phototoxicity to Daphnia magna and Oryzias latipes. Chemosphere 2014, 112, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, B.; Chandrasekaran, H.; Palamadai Krishnan, S.; Chandrasekaran, N.; Mukherjee, A. UVA pre-irradiation to P25 titanium dioxide nanoparticles enhanced its toxicity towards freshwater algae Scenedesmus obliquus. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 16729–16742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, B.; Suresh, P.K.; Chandrasekaran, N.; Mukherjee, A. UVB pre-irradiation of titanium dioxide nanoparticles is more detrimental to freshwater algae than UVA pre-irradiation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 104076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rex, C.; Mukherjee, A. The Comparative Effects of Visible Light and UV-A Radiation on the Combined Toxicity of P25 TiO2 Nanoparticles and Polystyrene Microplastics on Chlorella sp. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 30, 122700–122716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, Y.; Kanemitsu, Y. Determination of electron and hole lifetimes of rutile and anatase TiO2 single crystals. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012, 101, 133907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Liang, Z.; Zheng, X.; Zhao, W.; Wu, M.; Wang, Z. Toxicity of nano-TiO2 on algae and the site of reactive oxygen species production. Aquat. Toxicol. 2015, 158, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, X. Toxic Effects of TiO2 NPs on Zebrafish. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smii, H.; Khazri, A.; Ben Ali, M.; Mezni, A.; Hedfi, A.; Albogami, B.; Almalki, M.; Pacioglu, O.; Beyrem, H.; Boufahja, F. Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles Are Toxic for the Freshwater Mussel Unio ravoisieri: Evidence from a Multimarker Approach. Diversity 2021, 13, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltar, B.J.; Vieira, J.T.; Meire, R.O.; Suguihiro, N.M.; Rodrigues, S.P. The currently knowledge on toxicity of TiO2 nanoparticles in microalgae: A systematic review. Aquat. Toxicol. 2025, 287, 107530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellison, R.S.; Huling, S.G. TiO2 nanoparticle photoactivation and oxidation reactions in freshwater and marine systems: The role of radical scavengers. Chemosphere 2024, 361, 142549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Guo, L.H.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, L. UV irradiation induced transformation of TiO2 nanoparticles in water: Aggregation and photoreactivity. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 11962–11968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Ghoshal, S.; Moores, A.; George, S. Mechanistic study of the increased phototoxicity of titanium dioxide nanoparticles to Chlorella vulgaris in the presence of NOM eco-corona. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 262, 115164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaux, A.; Bony, S.; Plenet, S.; Sagnes, P.; Segura, S.; Suaire, R.; Novak, M.; Gilles, A.; Olivier, J.M. Field evidence of reproduction impairment through sperm DNA damage in the fish nase (Chondrostoma nasus) in anthropized hydrosystems. Aquat. Toxicol. 2015, 169, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambardella, C.; Morgana, S.; Bari, G.D.; Ramoino, P.; Bramini, M.; Diaspro, A.; Falugi, C.; Faimali, M. Multidisciplinary screening of toxicity induced by silica nanoparticles during sea urchin development. Chemosphere 2015, 139, 486–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinardy, H.C.; Bodnar, A.G. Profiling DNA damage and repair capacity in sea urchin larvae and coelomocytes exposed to genotoxicants. Mutagenesis 2015, 30, 829–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kukla, S.P.; Chelomin, V.P.; Slobodskova, V.V.; Mazur, A.A.; Dovzhenko, N.V. Toxic Effect of UV-Pre-Irradiated TiO2 Nanoparticles on the Sand Dollar Scaphechinus mirabilis Sperm. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2026, 14, 275. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14030275

Kukla SP, Chelomin VP, Slobodskova VV, Mazur AA, Dovzhenko NV. Toxic Effect of UV-Pre-Irradiated TiO2 Nanoparticles on the Sand Dollar Scaphechinus mirabilis Sperm. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2026; 14(3):275. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14030275

Chicago/Turabian StyleKukla, Sergey Petrovich, Victor Pavlovich Chelomin, Valentina Vladimirovna Slobodskova, Andrey Alexandrovich Mazur, and Nadezhda Vladimirovna Dovzhenko. 2026. "Toxic Effect of UV-Pre-Irradiated TiO2 Nanoparticles on the Sand Dollar Scaphechinus mirabilis Sperm" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 14, no. 3: 275. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14030275

APA StyleKukla, S. P., Chelomin, V. P., Slobodskova, V. V., Mazur, A. A., & Dovzhenko, N. V. (2026). Toxic Effect of UV-Pre-Irradiated TiO2 Nanoparticles on the Sand Dollar Scaphechinus mirabilis Sperm. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 14(3), 275. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14030275