Spatiotemporal Characteristics and Long-Term Variability of Large-Wave Frequency in the Northwest Pacific

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Data and Methods

2.1. Data

2.1.1. ERA5 SWH

2.1.2. Climate Index Data

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Analytical Framework

2.2.2. Linear Regression Method and -Statistics

- (1)

- Linear regression method

- (2)

- t-statistics

2.2.3. Pearson Correlation Coefficient and -Value

- (1)

- Pearson correlation coefficient

- (2)

- p-value

3. Results

3.1. Annual and Seasonal Distribution of f5

3.2. Annual and Seasonal Distribution of f7

3.3. Annual Trend in f5

3.4. Seasonal Trend in f5

3.5. Annual Trend in f7

3.6. Seasonal Trend in f7

4. Correlations Between f5/f7 and Key Climate Indexes

4.1. Correlation Between f5 and Key Climate Indexes

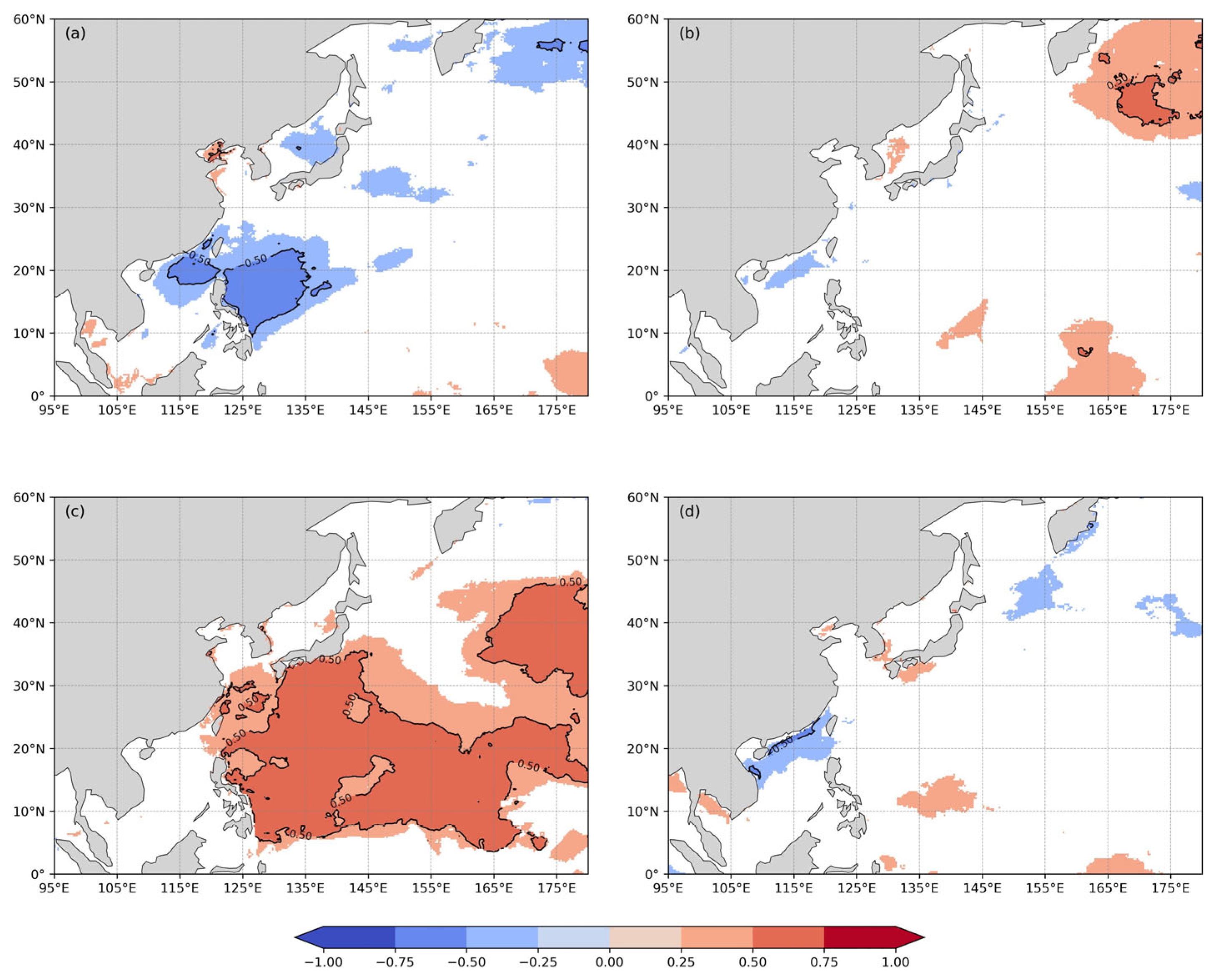

4.1.1. Correlation with AO

4.1.2. Correlation with ONI

4.1.3. Correlation with PDO

4.2. Correlation Between f7 and Key Climate Indexes

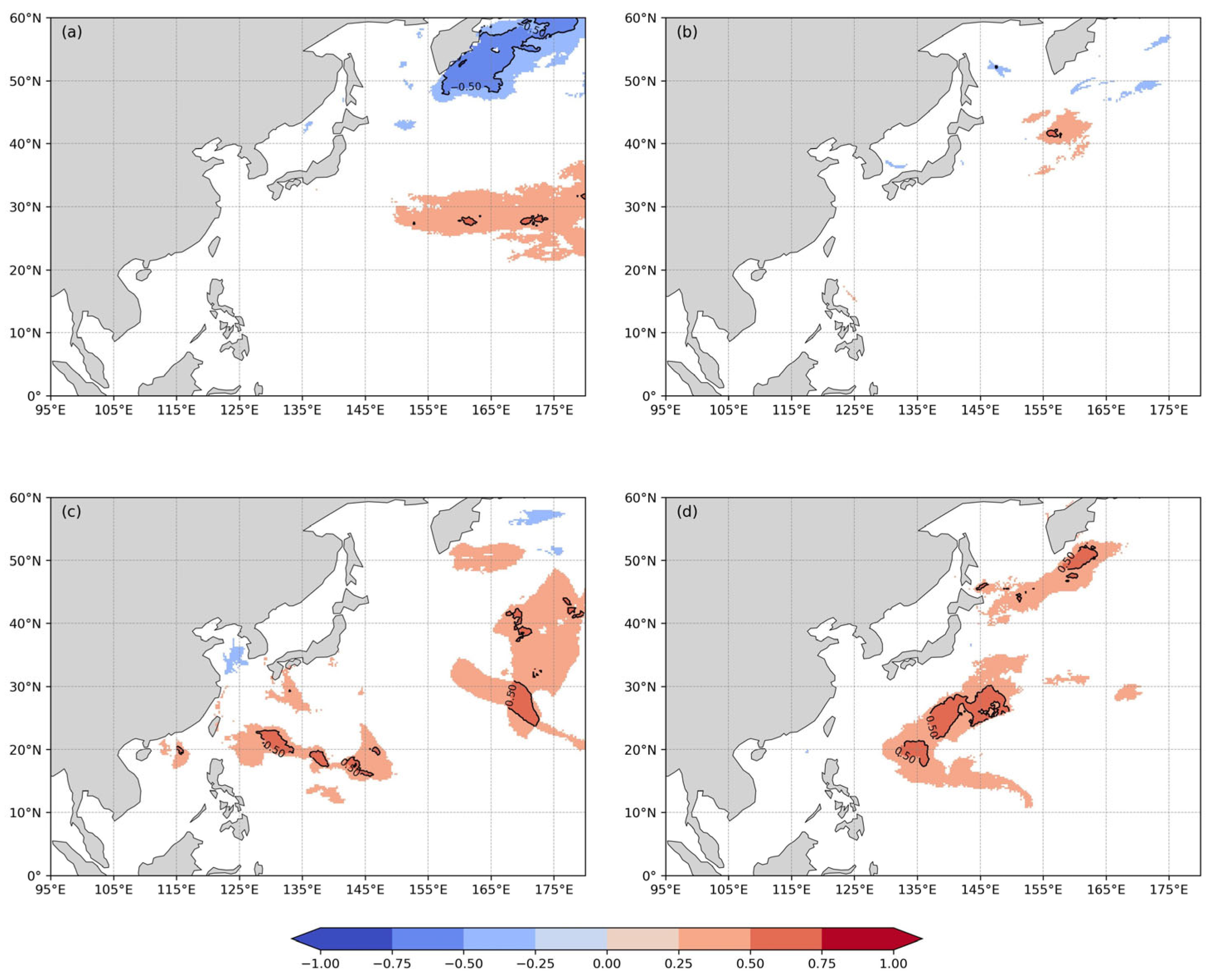

4.2.1. Correlation with AO

4.2.2. Correlation with ONI

4.2.3. Correlation with PDO

5. Conclusions and Outlook

- (1)

- The region with the greatest annual gradient of f5 is located eastward from Japan to 160° E. The highest annual mean value of f5 occurs in the waters south of the Aleutian Islands, reaching 58.0%, while significant annual maxima are also present in the central Taiwan Strait and both sides of the Luzon Strait, reaching 26.4% and 24.0%, respectively. Winter contributes most significantly to the annual mean f5, with seasonal maxima of 64.3%, 15.3%, 62.2% and 96.9%, respectively.

- (2)

- The region with the greatest annual gradient of f7 is located between 30° N and 45° N (between 160° E and 180° E). The highest annual mean value is found in the waters south of the Aleutian Islands, reaching 6.4%, with the greatest contribution occurring in winter. An annual peak occurs in the waters east of Taiwan Island, reaching up to 0.7%, with primary contributions in summer and autumn. The seasonal maxima are 4.8%, 1.6%, 5.9% and 16.8%, respectively.

- (3)

- f5 exhibits a significant decreasing trend in the NWP basin, with a maximum rate of 0.30% per year and a cumulative reduction of 9.6% over 32 years. The most pronounced decline occurs in autumn, reaching a maximum rate of 0.69% per year. Significant upward trends are observed in the coastal waters around the Kamchatka Peninsula, the southwestern coastal waters of Hokkaido, and the southern waters of the Marshall Islands, with maximum rates of 0.49%, 0.18% and 0.11% per year, respectively. The cumulative increases over 32 years are 15.68%, 5.76% and 3.52%. Winter contributes most to the annual increasing trends in these three regions, with maximum rates reaching 1.64%, 0.61% and 0.47% per year, respectively.

- (4)

- f7 exhibits a significant decreasing trend in the eastern oceanic regions of Japan and a significant increasing trend in the Bering Sea, with maximum rates of decrease and increase both reaching 0.08% per year (accumulating to 2.56% reduction and 2.56% increase over 32 years). Winter contributes most significantly to the annual average changes in the decreasing and increasing regions, with maximum rates reaching 0.27% and 0.30% per year, respectively.

- (5)

- Seasonal and regional variations in climate index–f5 and f7 relationships reflect large-scale atmospheric modulation of waves. For example, the AO index and f5 exhibit positive correlations during winter and spring, but negative correlations in summer and autumn. The ONI shows a predominantly negative correlation with f5 in winter (rm = −0.70) around the Luzon Strait, shifting to a significant positive correlation in summer (rm = 0.70) across the extensive region east of Taiwan Island and the Philippines. The PDO index shows a significant positive correlation with f7 in summer and autumn (rm = 0.69) east of Taiwan Island and a strong negative correlation in winter (rm = −0.77) to the east of Kamchatka.

- (6)

- The core mechanism lies in how phase shifts in climate indexes modulate Northern Hemisphere atmospheric circulation, thereby affecting the intensity and paths of the WPSH, typhoons, monsoons, and extratropical cyclones. This ultimately alters the structure of sea surface wind fields, modulating the generation and propagation of ocean waves. Compared to f7, the correlations between various climate indexes and f5 are more pronounced, manifesting in broader regions of association, larger areas of moderate to strong correlations, and clearer spatial patterns and seasonal evolution. Furthermore, the influence exerted by the same climate index on f5 and f7 exhibits certain similarities.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, J.; Hsieh, C.; Liu, J. Possible Influences of ENSO on Winter Shipping in the North Pacific. Terr. Atmos. Ocean. Sci. 2012, 23, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Meza, A.; Ari, I.; Sada, M.A.; Koç, M. Relevance and Potential of the Arctic Sea Routes on the LNG Trade. Energy Strategy Rev. 2023, 50, 101174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Tan, P.; Hsieh, C.; Liu, J.; Chen, H.; Hsu, L.; Huang, J. Seasonal Climate Associated with Major Shipping Routes in the North Pacific and North Atlantic. Terr. Atmos. Ocean. Sci. 2014, 25, 381–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, C.; Zhuang, H.; Li, X.; Li, X. Wind Energy and Wave Energy Resources Assessment in the East China Sea and South China Sea. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2012, 55, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, H.H. Major Structural Features of the Western North Pacific, an Interpretation of H.O. 5485, Bathymetric Chart, Korea to New Guinea. GSA Bull. 1948, 59, 417–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ma, W.; Wang, T.; Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Sean, M.; Yang, Z.; Wang, J. Dynamic Optimisation of Evacuation Route in the Fire Scenarios of Offshore Drilling Platforms. Ocean Eng. 2022, 247, 110564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bröker, K.C.A.; Gailey, G.; Tyurneva, O.Y.; Yakovlev, Y.M.; Sychenko, O.; Dupont, J.M.; Vertyankin, V.V.; Shevtsov, E.; Drozdov, K.A. Site-Fidelity and Spatial Movements of Western North Pacific Gray Whales on Their Summer Range off Sakhalin, Russia. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Maritime Organization (IMO). Guidelines for the Assessment of Ship Seakeeping Performance; IMO Publishing: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, L.; Liu, S.; Zeng, J.; Qin, S.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, G.; Zheng, J.; Liang, Q.; Tao, A. Long-Term Trends of Extreme Waves Based on Observations from Five Stations in China. J. Mar. Sci. Appl. 2025, 24, 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Niu, X. Trends of Extreme Waves around Hainan Island during Typhoon Processes. Ocean Eng. 2024, 308, 118247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristodemo, F.; Loarca, A.L.; Besio, G.; Caloiero, T. Detection and Quantification of Wave Trends in the Mediterranean Basin. Dyn. Atmos. Ocean. 2024, 105, 101413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananthu, P.; Shanas, P.R.; Komath, S.; Sivakrishnan, K.K.; Kumar, V.S. Wave Climate of Kerala Coast: An 83-Year ERA-5 Study of Trends and Seasonality. Earth Syst. Environ. 2025. published online before print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Zhou, L.; Huang, C.; Shi, Y.; Li, J.; Li, J. The Long-Termtrend of the Sea Surface Wind Speed and the Wave Height (Wind Wave, Swell, Mixed Wave) in Global Ocean During the Last 44 a. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2013, 32, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Zhou, L.; Shi, W.; Li, X.; Huang, C. Decadal Variability of Global Ocean Significant Wave Height. J. Ocean Univ. China 2015, 14, 778–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Li, X.; Azorin-Molina, C.; Li, C.; Wang, Q.; Xiao, Z.; Yang, S.; Chen, X.; Zhan, C. Global Trends in Oceanic Wind Speed, Wind-Sea, Swell, and Mixed Wave Heights. Appl. Energy 2022, 321, 119327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Li, C. Variation of the Wave Energy and Significant Wave Height in the China Sea and Adjacent Waters. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 43, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C. Global Oceanic Wave Energy Resource Dataset—With the Maritime Silk Road as a Case Study. Renew. Energy 2021, 169, 843–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C. Discovery of the Significant Impacts of Swell Propagation on Global Wave Climate Change. J. Ocean Univ. China 2024, 23, 594–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omonigbehin, O.; Eresanya, E.O.; Tao, A.; Setordjie, V.E.; Daramola, S.; Adebiyi, A. Long-Term Evolution of Significant Wave Height in the Eastern Tropical Atlantic between 1940 and 2022 Using the ERA5 Dataset. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivas, G.; Remya, P.G.; Dey, S.P.; Chowdary, J.S.; Kumar, P. Impact of the Pacific-Japan Pattern on the Tropical Indo-Western Pacific Ocean Surface Waves. Clim. Dyn. 2024, 62, 8729–8740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagli, B.; Duphil, M.; Jullien, S.; Dutheil, C.; Peltier, A.; Menkes, C. Wave Climate around New Caledonia. Clim. Dyn. 2024, 62, 8865–8887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Oh, J. Long-Term Changes in the Extreme Significant Wave Heights on the Western North Pacific: Impacts of Tropical Cyclone Activity and ENSO. Asia-Pac. J. Atmos. Sci. 2018, 54, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Z.; He, Y.; Wang, S.; Chang, S.; Leng, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Sui, H.; et al. Dynamics, Chemistry, and Modeling Studies in the Aviation and Aerospace Transition Zone. Innovation 2025, 6, 101012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, A.; Tangang, F.; Juneng, L.; Mustapha, M.A.; Husain, M.L.; Akhir, M.F. Wave Climate Simulation for Southern Region of the South China Sea. Ocean Dyn. 2013, 63, 961–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Moorthi, S.; Pan, H.-L.; Wu, X.; Wang, J.; Nadiga, S.; Tripp, P.; Kistler, R.; Woollen, J.; Behringer, D.; et al. The NCEP Climate Forecast System Reanalysis. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2010, 91, 1015–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Moorthi, S.; Wu, X.; Wang, J.; Nadiga, S.; Tripp, P.; Behringer, D.; Hou, Y.-T.; Chuang, H.; Iredell, M.; et al. The NCEP Climate Forecast System Version 2. J. Clim. 2014, 27, 2185–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, S.; Ota, Y.; Harada, Y.; Ebita, A.; Moriya, M.; Onoda, H.; Onogi, K.; Kamahori, H.; Kobayashi, C.; Endo, H.; et al. The JRA-55 Reanalysis: General Specifications and Basic Characteristics. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. 2015, 93, 5–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelaro, R.; McCarty, W.; Suárez, M.J.; Todling, R.; Molod, A.; Takacs, L.; Randles, C.; Darmenov, A.; Bosilovich, M.G.; Reichle, R.; et al. The Modern-Era Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications, Version 2 (MERRA-2). J. Clim. 2018, 30, 5419–5454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersbach, H.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Hirahara, S.; Horányi, A.; Muñoz-Sabater, J.; Nicolas, J.; Peubey, C.; Radu, R.; Schepers, D.; et al. The ERA5 Global Reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2020, 146, 1999–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.L.; Zheng, C.W.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z.H.; Liang, B.; Luo, X. Evaluation of ERA5 Significant Wave Height over the Global Ocean. Ocean Eng. 2022, 266, 112842. [Google Scholar]

- Babagolimatikolaei, J. A Comparative Study of the Sensitivity of an Ocean Model Outputs to Atmospheric Forcing: ERA-Interim vs. ERA5 for Adriatic Sea Ocean Modelling. Dyn. Atmos. Ocean. 2025, 109, 101525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, R.; Huang, C.; Yang, W.; Tang, L.; Zhang, W. Applicability Evaluation of ERA5 Wind and Wave Reanalysis Data in the South China Sea. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 2023, 41, 495–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Lou, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Bai, J. Assessment of ERA-Interim and ERA5 Reanalysis Data on Atmospheric Corrections for InSAR. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 111, 102822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Cao, X.; Li, Q.; Li, D.; Sun, J.; You, Z.; Sun, Q. Evaluating the Accuracy of ERA5 Wave Reanalysis in the Water Around China. J. Ocean Univ. China 2021, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Du, Q.; Xia, J.; Huang, F.; Yin, C.; Meng, X.; Bai, W.; Sun, Y.; Wang, X.; Duan, L.; et al. Comparative Analysis of SWH retrieval between BDS-R and GPS-R utilizing FY-3E/GNOS-II data. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 6520–6531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, J.; Yu, K. Significant Wave Height Retrieval Method Based on Spaceborne GNSS Reflectometry. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2022, 19, 1503705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Lin, M.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, Y. Wave Height Estimation and Validation Based on the UFS Mode Data of Gaofen-3 in South China Sea. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 2797–2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Y. Evaluation of the ERA5 Significant Wave Height against NDBC Buoy Data from 1979 to 2019. Mar. Geod. 2022, 45, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Zheng, C.; Li, L.; Dai, Y.; Esteban, M.D.; López-Gutiérrez, J.S.; Qu, X.; Zhang, X. Wave Energy Assessment Related to Wave Energy Convertors in the Coastal Waters of China. Energy 2020, 202, 117741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Shao, L.; Shi, W.; Su, Q.; Lin, G.; Li, X.; Chen, X. An Assessment of Global Ocean Wave Energy Resources over the Last 45 a. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2014, 33, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Ciria, T.; Labat, D.; Chiogna, G. Heterogeneous Spatiotemporal Streamflow Response to Large-Scale Climate Indexes in the Eastern Alps. J. Hydrol. 2022, 615, 128698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Leo, N.; Barbona, I.; Beltrán, C.; Primo Fernando, F.; Coronel, A.; Jozami, E. Temporal Variability of Spatial Patterns of Correlations between Summer Rainfall and the Oceanic Niño Index in the Pampean Region. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 955, 176849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormaza-González, F.I.; Espinoza-Celi, M.E.; Roa-López, H.M. Did Schwabe Cycles 19–24 Influence the ENSO Events, PDO, and AMO Indexes in the Pacific and Atlantic Ocean? Glob. Planet. Change 2022, 217, 103928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilks, D.S. Statistical Methods in the Atmospheric Sciences; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Von Storch, H.; Zwiers, F.W. Statistical Analysis in Climate Research. Int. J. Climatol. 2000, 20, 811–812. [Google Scholar]

- Young, I.R.; Zieger, S.; Babanin, A.V. Global Trends in Wind Speed and Wave Height. Science 2011, 332, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantua, N.J.; Hare, S.R. The Pacific Decadal Oscillation. J. Oceanogr. 2002, 58, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N.; Zhang, T.; Ren, Q.; Cheung, H.N.; Ho, C.H.; Yang, S. Interactions of the Background State and Eddies in Shaping Aleutian Low Variations. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2025, 42, 1548–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, Y.; Tozuka, T. Dominant Forcing Regions of Decadal Variations in the Kuroshio Extension Revealed by a Linear Rossby Wave Model. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2023, 50, e2023GL102995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Tam, C.; Li, Y.; Lau, N.; Chen, J.; Chan, S.T.; Dickson Lau, D.; Huang, Y. How Does Air-Sea Wave Interaction Affect Tropical Cyclone Intensity? An Atmosphere-Wave-Ocean Coupled Model Study Based on Super Typhoon Mangkhut (2018). Earth Space Sci. 2022, 9, e2021EA002136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, S.; Jin, F.; Tian, J.; Lin, I.I.; Pun, I.F.; Zhao, W.; Huthnance, J.; Xu, Z.; Cai, W.; Jing, Z.; et al. Ocean internal tides suppress tropical cyclones in the South China Sea. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Tan, Z. Influence of Track Change on the Inconsistent Poleward Migration of Typhoon Activity. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2022, 127, e2022JD036640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Area | Annual Extreme Value | Spring Extreme Value | Summer Extreme Value | Autumn Extreme Value | Winter Extreme Value | Dominant Season |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Waters south of the Aleutian Islands | 58.0% | 64.3% | 12.8% | 62.2% | 96.9% | Winter |

| Sea of Okhotsk | 35.0% | 29.7% | 3.0% | 36.2% | 50.4% | Winter |

| Sea of Japan | 16.8% | 10.1% | 2.9% | 17.3% | 41.8% | Winter |

| Both sides of the Luzon Strait | 26.4% | 13.1% | 13.8% | 34.6% | 51.2% | Winter |

| Taiwan Strait | 24.0% | 14.2% | 6.8% | 33.3% | 46.6% | Winter |

| Area | Annual Extreme Value | Spring Extreme Value | Summer Extreme Value | Autumn Extreme Value | Winter Extreme Value | Dominant Season |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Waters south of the Aleutian Islands | 6.4% | 4.8% | 0.2% | 5.9% | 16.8% | Winter |

| Sea of Okhotsk | 1.5% | 1.2% | 0.1% | 1.7% | 3.4% | Winter |

| Sea of Japan | 0.6% | 0.3% | 0.03% | 0.3% | 1.9% | Winter |

| Waters east of Taiwan Island | 0.7% | 0.2% | 1.6% | 1.5% | 0.1% | Summer and autumn |

| Correlation Coefficient | Feb | May | Aug | Nov | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum positive Correlation coefficient | 0.51 | 0.48 | 0.46 | 0.50 | 0.51 |

| Absolute maximum negative Correlation coefficient | −0.53 | −0.48 | −0.54 | −0.64 | −0.64 |

| Correlation Coefficient | Feb | May | Aug | Nov | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum positive Correlation coefficient | 0.60 | 0.59 | 0.70 | 0.53 | 0.70 |

| Absolute maximum negative Correlation coefficient | −0.70 | −0.47 | −0.42 | −0.64 | −0.70 |

| Correlation Coefficient | Feb | May | Aug | Nov | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum positive Correlation coefficient | 0.47 | 0.52 | 0.63 | 0.64 | 0.64 |

| Absolute maximum negative Correlation coefficient | −0.56 | −0.46 | −0.43 | −0.50 | −0.56 |

| Correlation Coefficient | Feb | May | Aug | Nov | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum positive Correlation coefficient | 0.48 | 0.37 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| Absolute maximum negative Correlation coefficient | −0.62 | −0.41 | −0.49 | −0.52 | −0.62 |

| Correlation Coefficient | Feb | May | Aug | Nov | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum positive Correlation coefficient | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.67 | 0.57 | 0.67 |

| Absolute maximum negative Correlation coefficient | −0.49 | −0.55 | NaN | −0.36 | −0.55 |

| Correlation Coefficient | Feb | May | Aug | Nov | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum positive Correlation coefficient | 0.55 | 0.54 | 0.69 | 0.63 | 0.69 |

| Absolute maximum negative Correlation coefficient | −0.77 | −0.52 | −0.41 | −0.38 | −0.77 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhao, Z.-Y.; Leng, H.-Z.; Wei, Y.-H.; Yang, J.-H.; Zhou, X.; Zhao, Z.-Z.; Wang, H.-P.; Li, B.-X.; Wang, W.-X.; Song, J.-Q. Spatiotemporal Characteristics and Long-Term Variability of Large-Wave Frequency in the Northwest Pacific. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2026, 14, 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14020200

Zhao Z-Y, Leng H-Z, Wei Y-H, Yang J-H, Zhou X, Zhao Z-Z, Wang H-P, Li B-X, Wang W-X, Song J-Q. Spatiotemporal Characteristics and Long-Term Variability of Large-Wave Frequency in the Northwest Pacific. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2026; 14(2):200. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14020200

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Zhen-Yu, Hong-Ze Leng, Yu-Han Wei, Jin-Hui Yang, Xuan Zhou, Ze-Zheng Zhao, Hui-Peng Wang, Bao-Xu Li, Wu-Xin Wang, and Jun-Qiang Song. 2026. "Spatiotemporal Characteristics and Long-Term Variability of Large-Wave Frequency in the Northwest Pacific" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 14, no. 2: 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14020200

APA StyleZhao, Z.-Y., Leng, H.-Z., Wei, Y.-H., Yang, J.-H., Zhou, X., Zhao, Z.-Z., Wang, H.-P., Li, B.-X., Wang, W.-X., & Song, J.-Q. (2026). Spatiotemporal Characteristics and Long-Term Variability of Large-Wave Frequency in the Northwest Pacific. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 14(2), 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14020200