Research on Multi-USV Collision Avoidance Based on Priority-Driven and Expert-Guided Deep Reinforcement Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Related Works

1.2. Novelty and Contributions

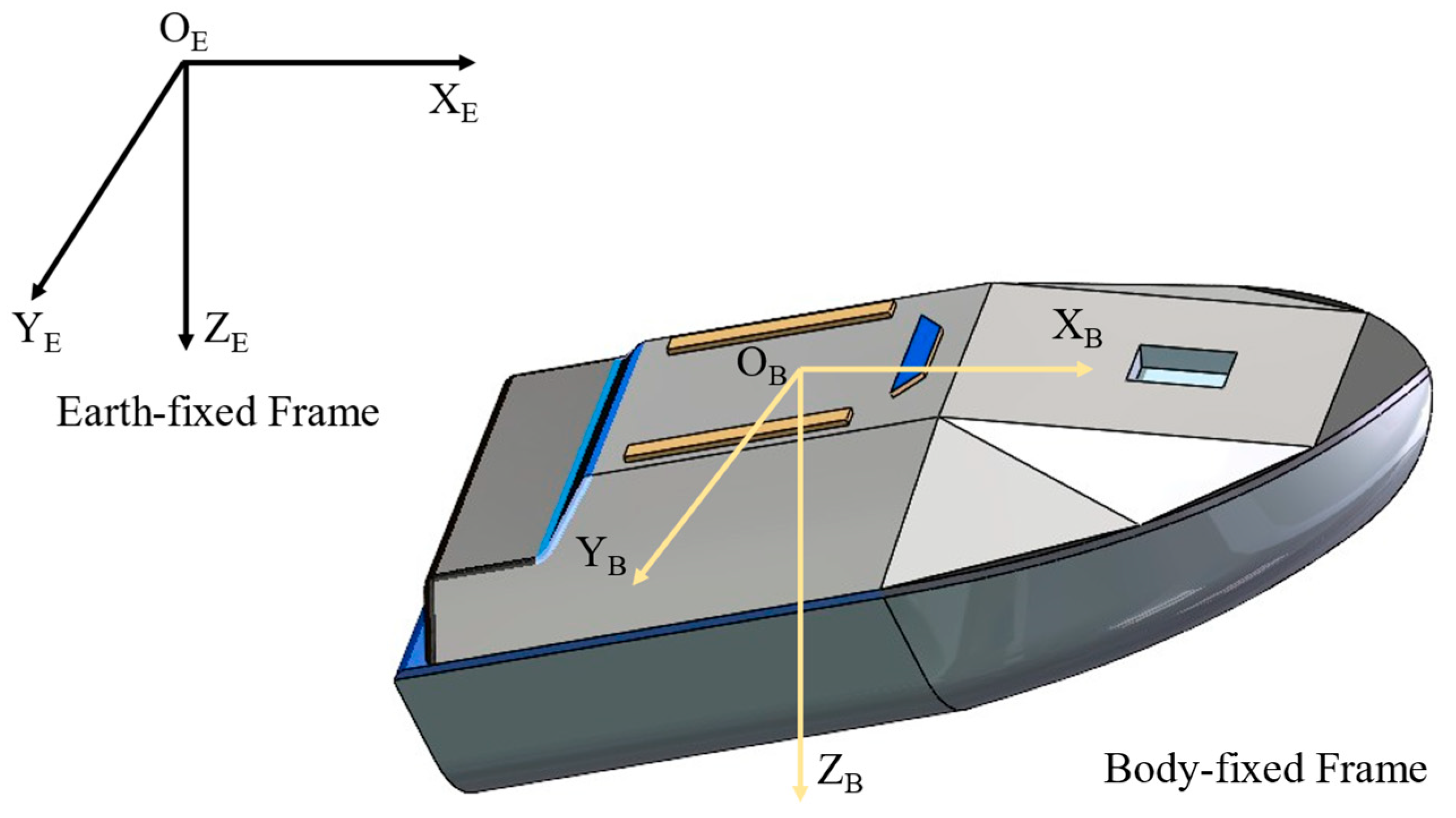

2. Dynamics of Unmanned Surface Vessel

2.1. USV Model

2.2. Vessel Dynamics Characteristics

2.2.1. Dynamic Modeling of Motion Systems

2.2.2. Kinematic Characteristics

3. Proposed Deep Reinforcement Learning Method for Collision Avoidance

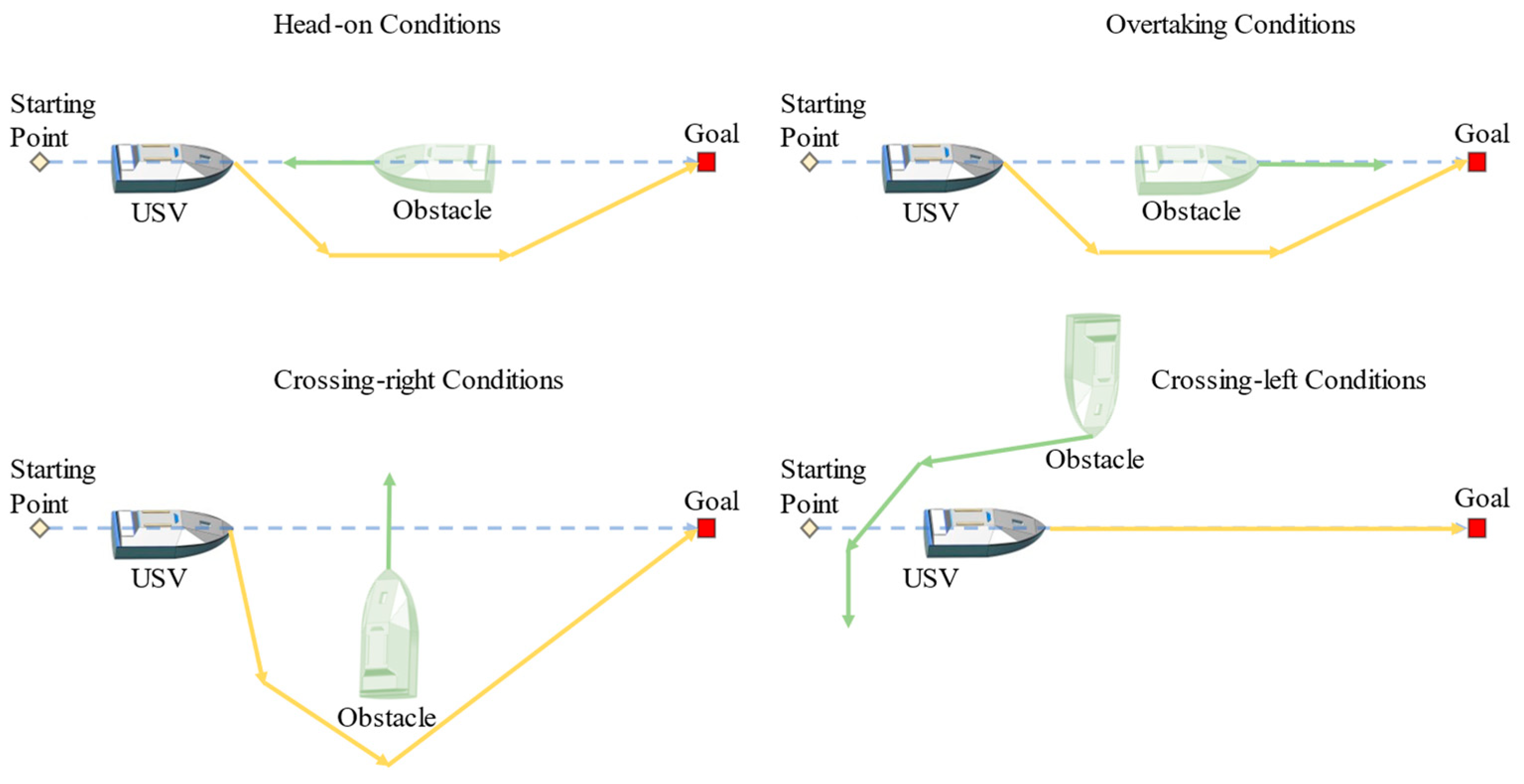

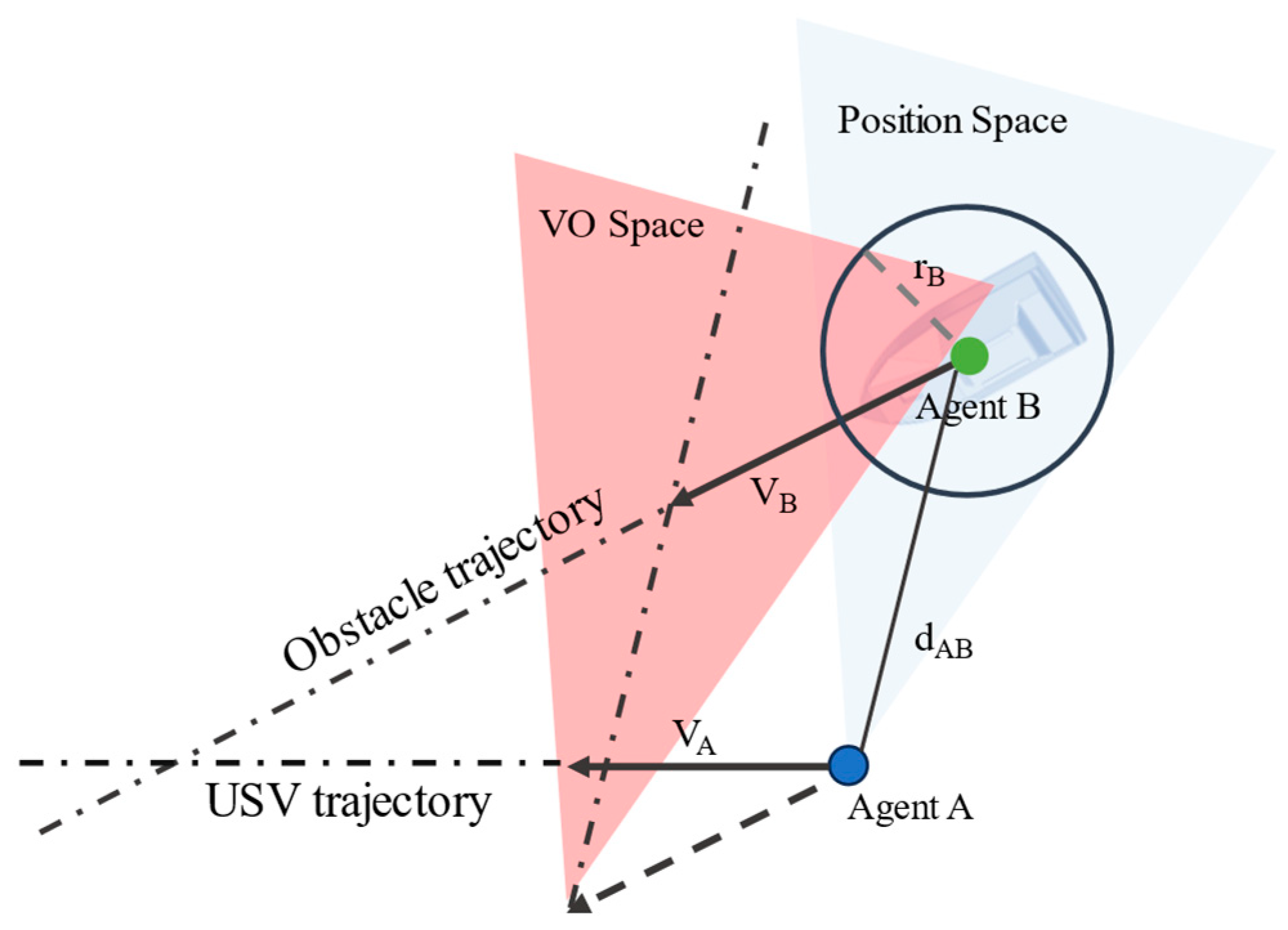

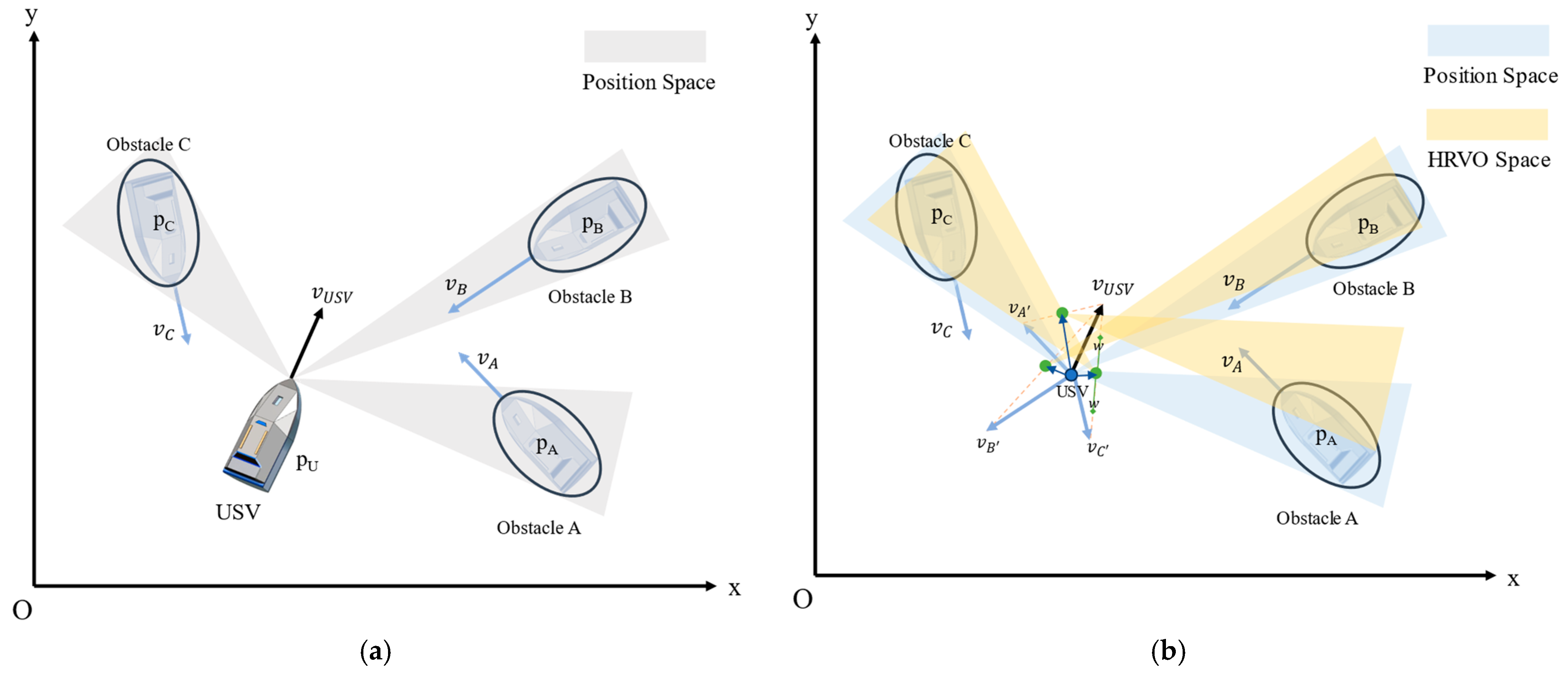

3.1. COLREGs-Aware Velocity Selection with HRVO

3.1.1. The COLREGs Rules

3.1.2. Hybrid Reciprocal Velocity Obstacles Method

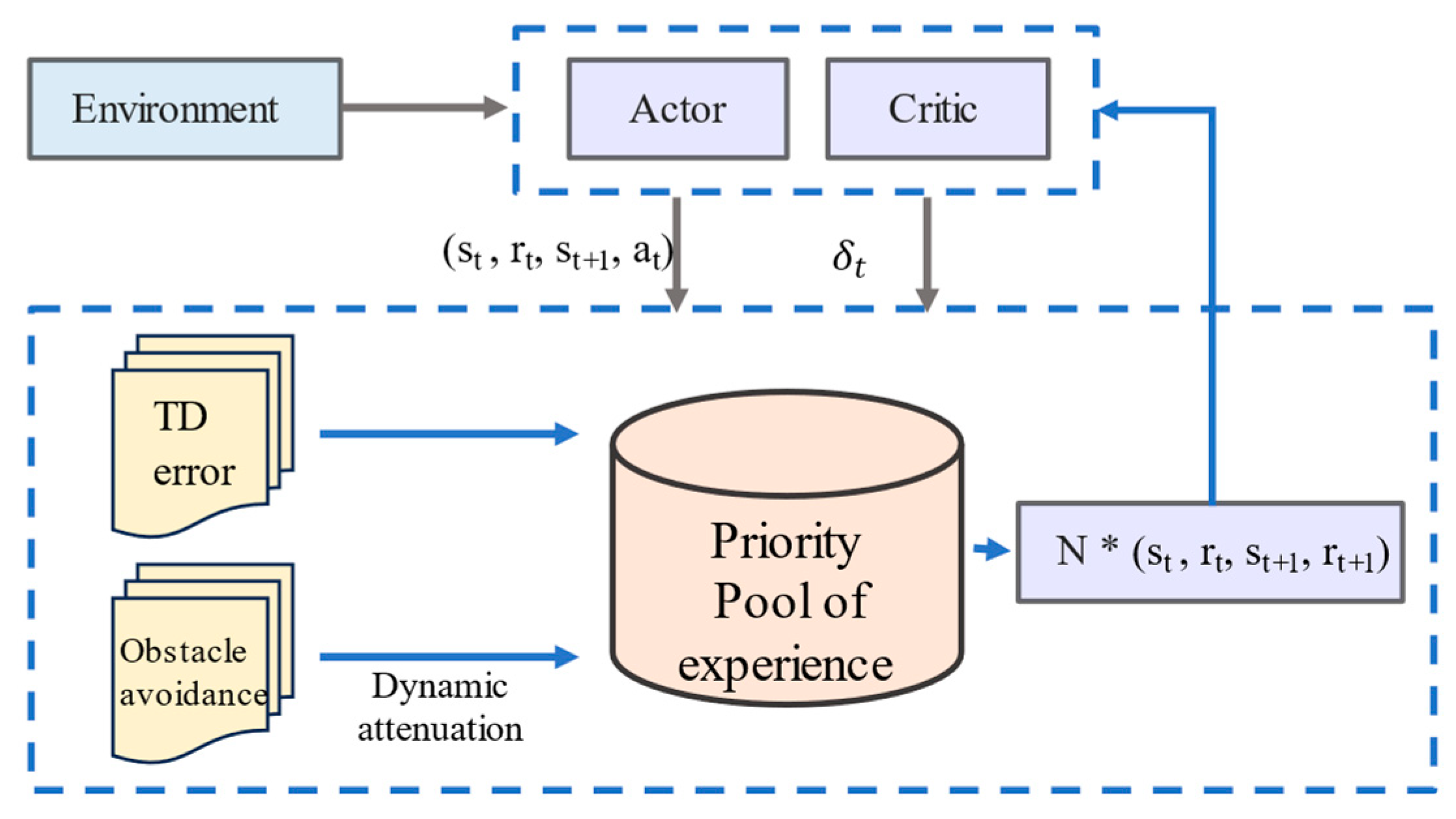

3.2. Dual-Priority Experience Replay Mechanism

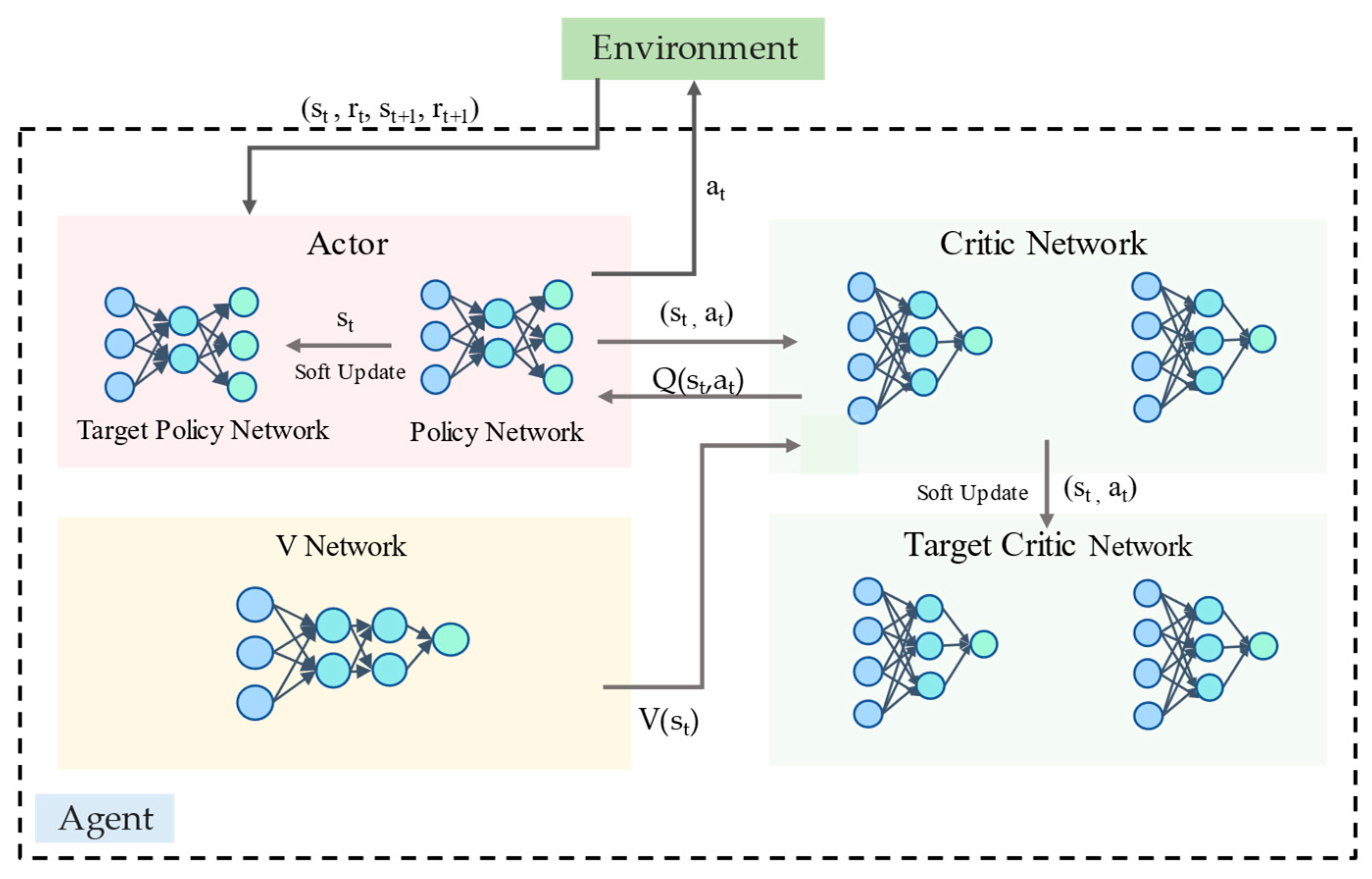

3.3. DPER-SAC Algorithm Architecture

3.3.1. Network Design and Agent Architecture

3.3.2. Reward Function Design

- The proximity reward and terminal reward

- 2.

- The heading and distance error reward

- 3.

- The obstacle avoidance reward

- 4.

- The COLREGs reward

- 5.

- Encounter-dependent risk weighting

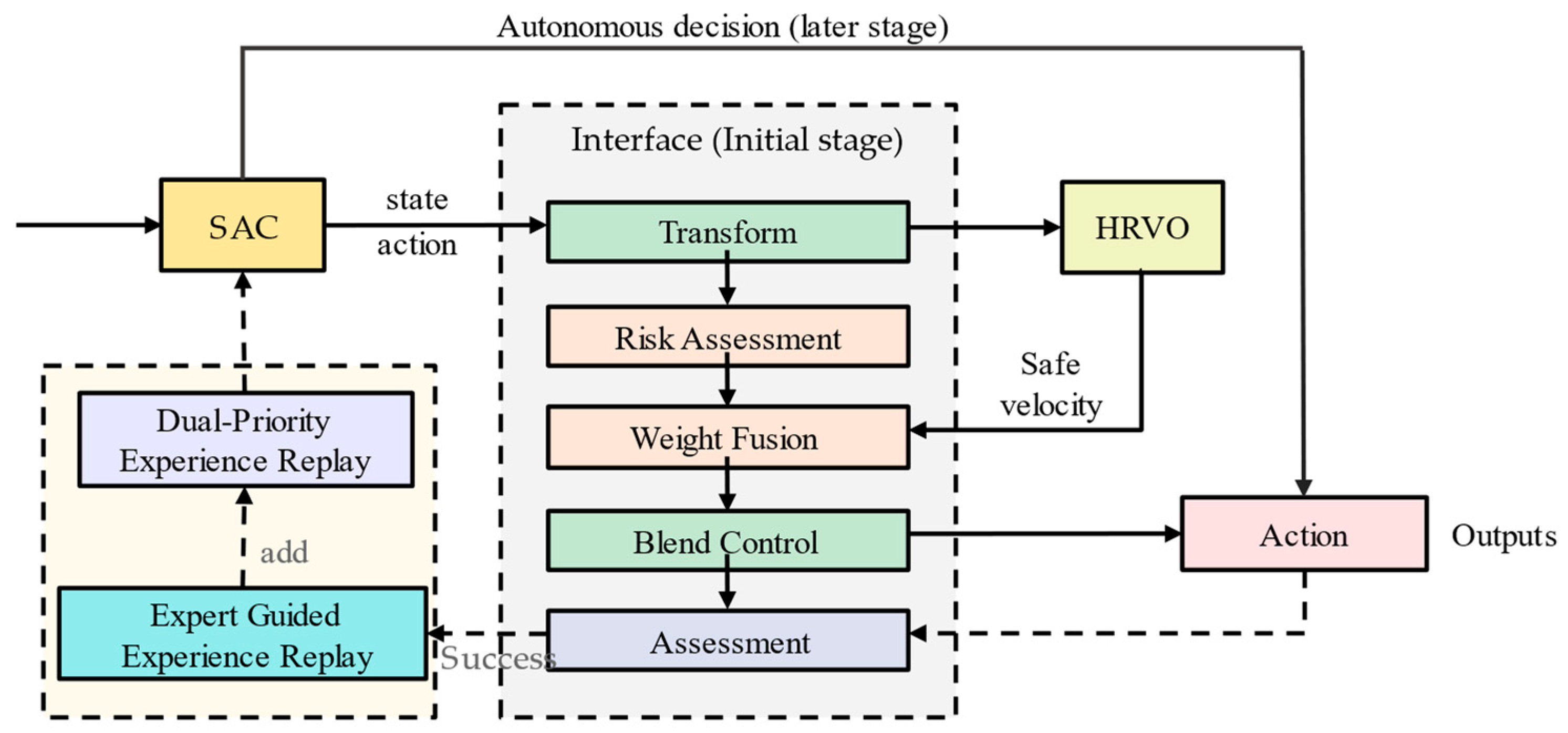

3.4. Expert-Guided Deep Reinforcement Learning Strategy

4. Simulation Analysis

4.1. Environment and Parameters

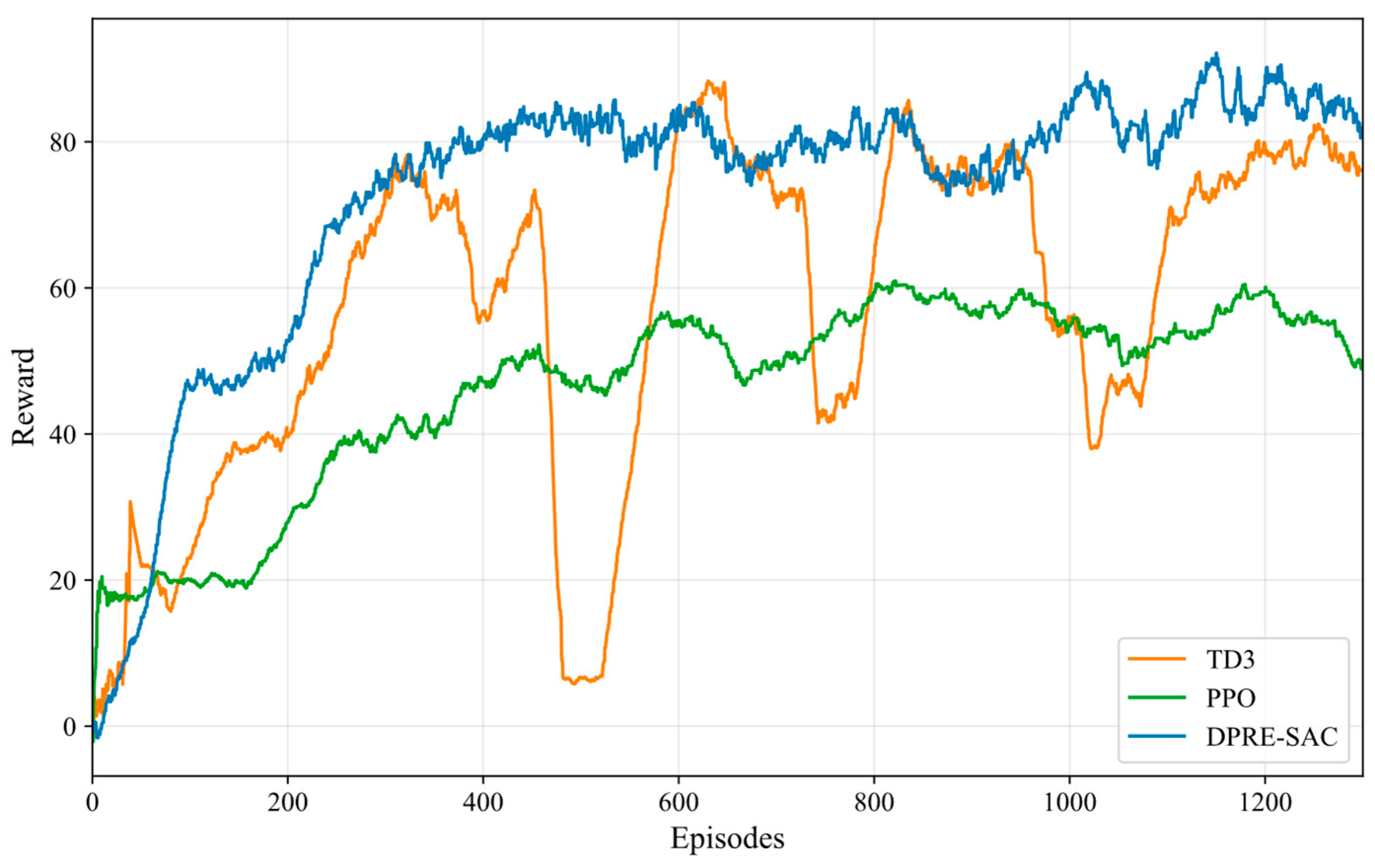

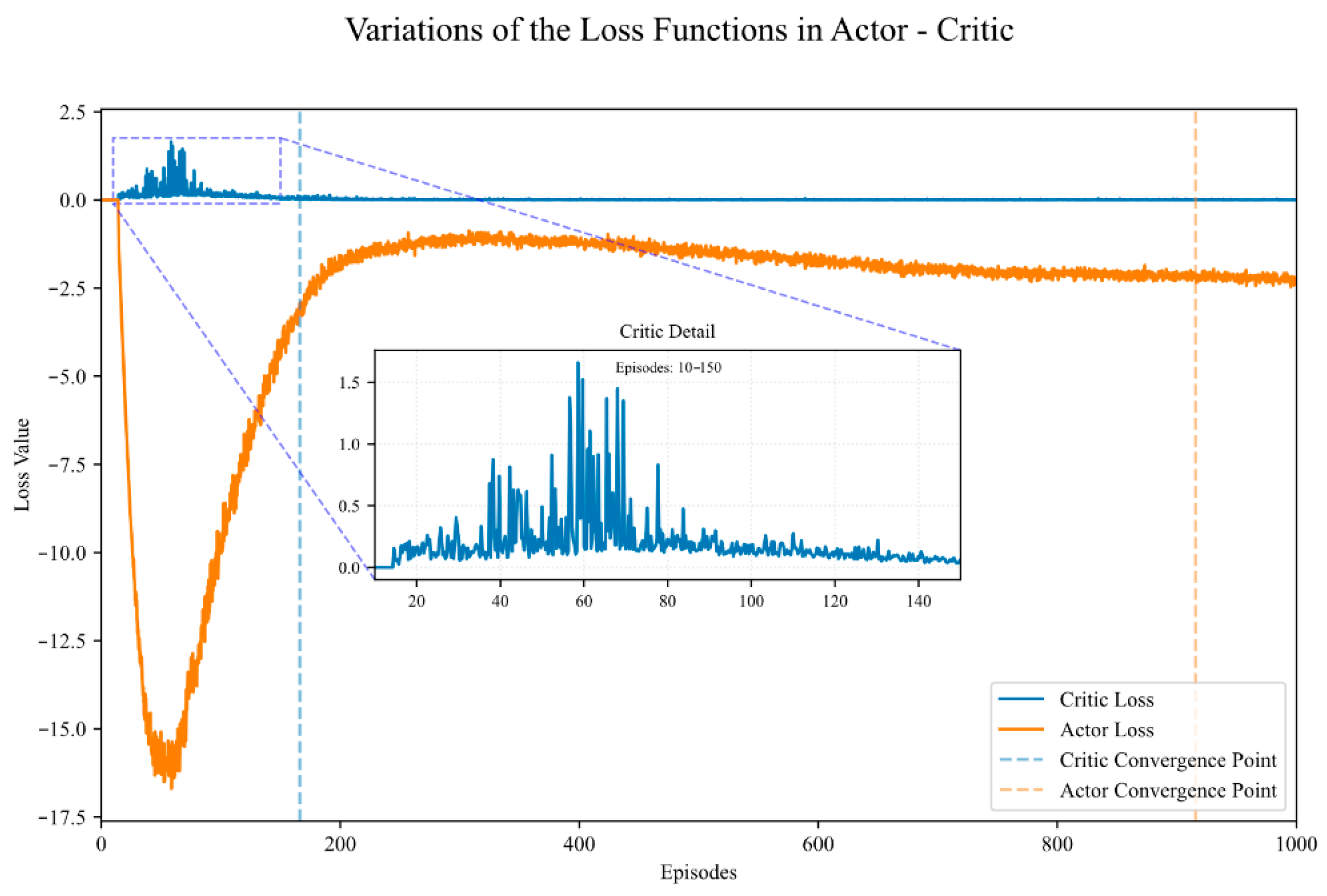

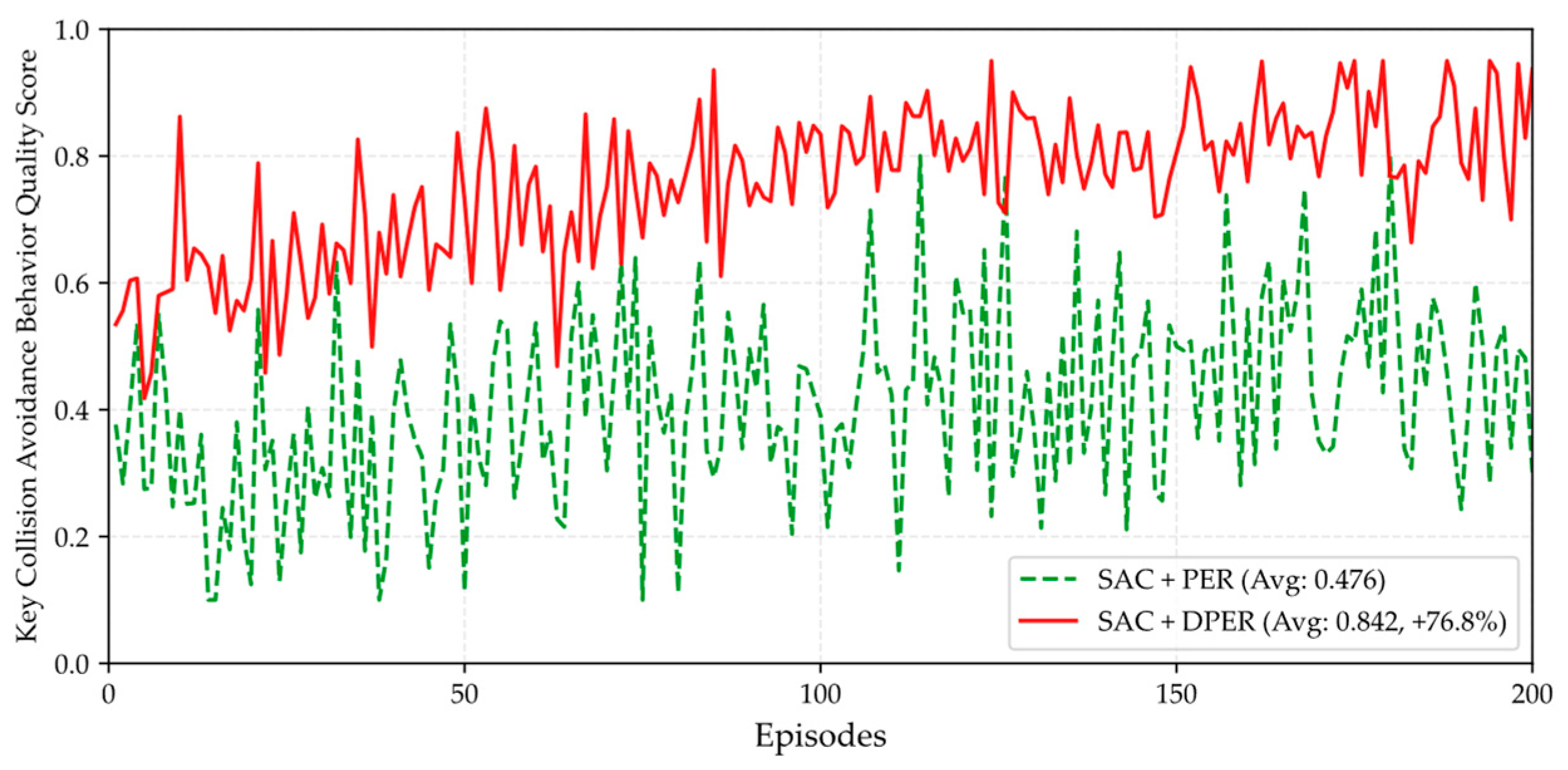

4.2. Convergence Verification of Loss and Reward Functions

4.3. Two-Vessel Encounter Scenarios in Simulation

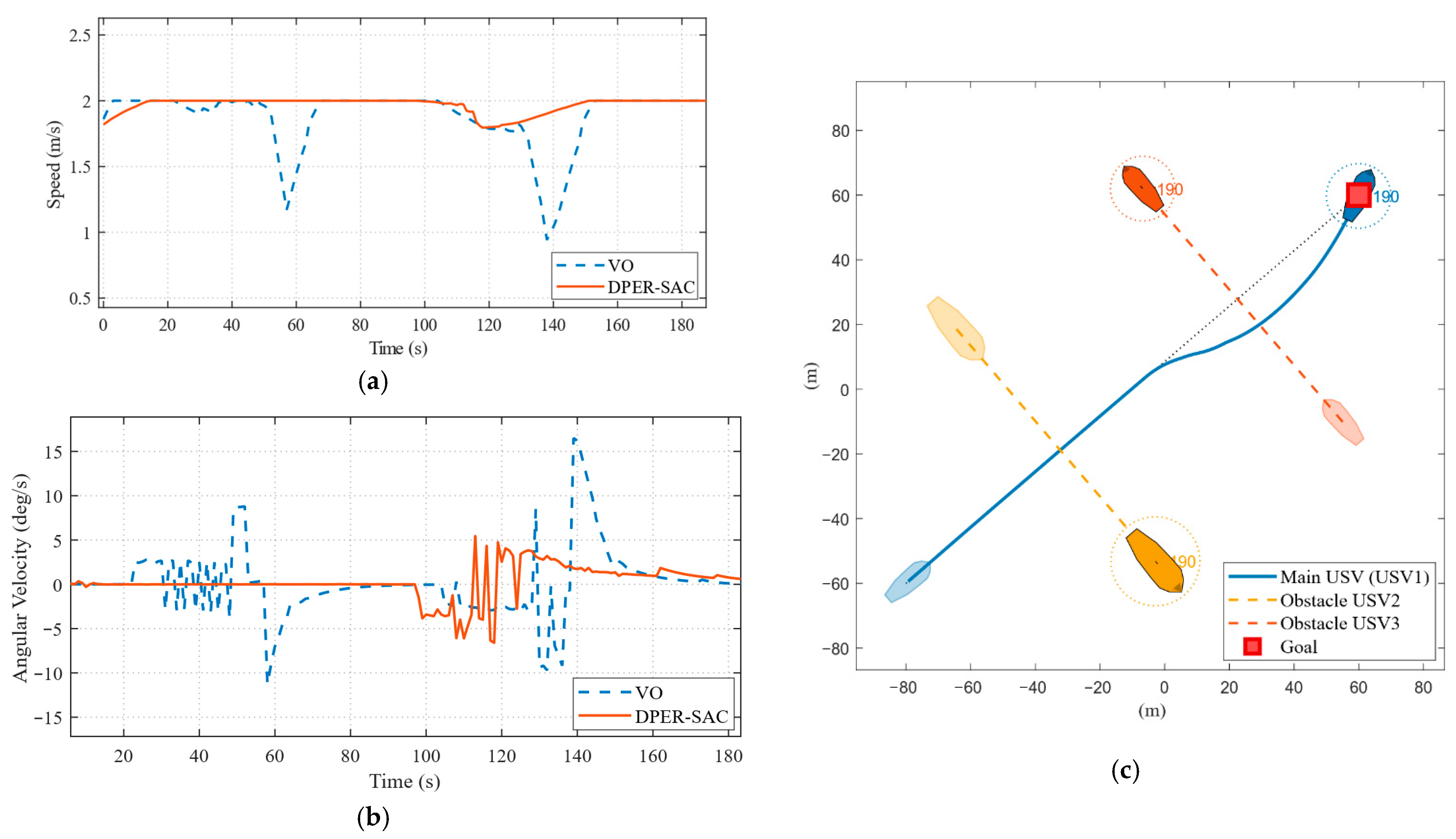

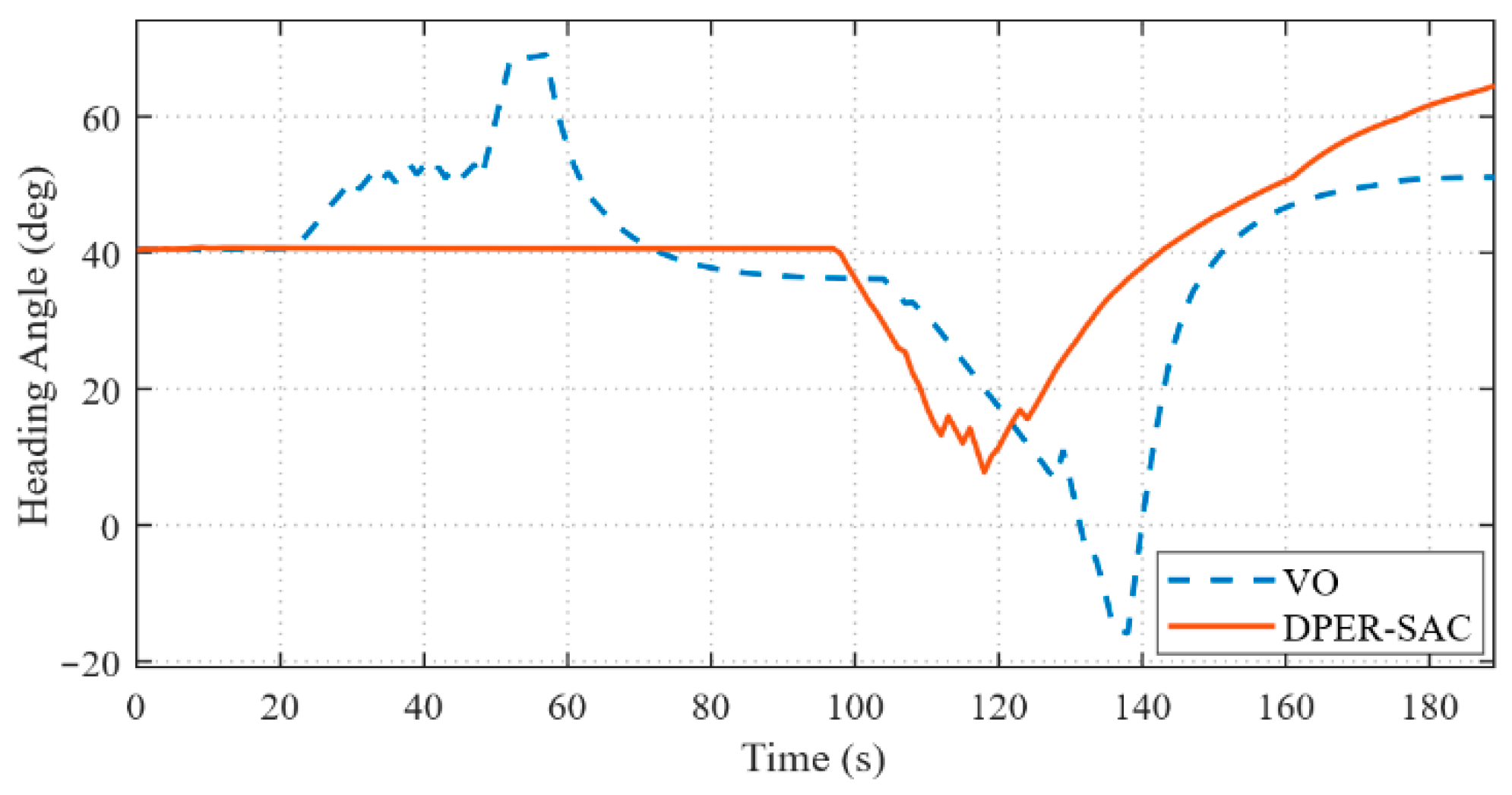

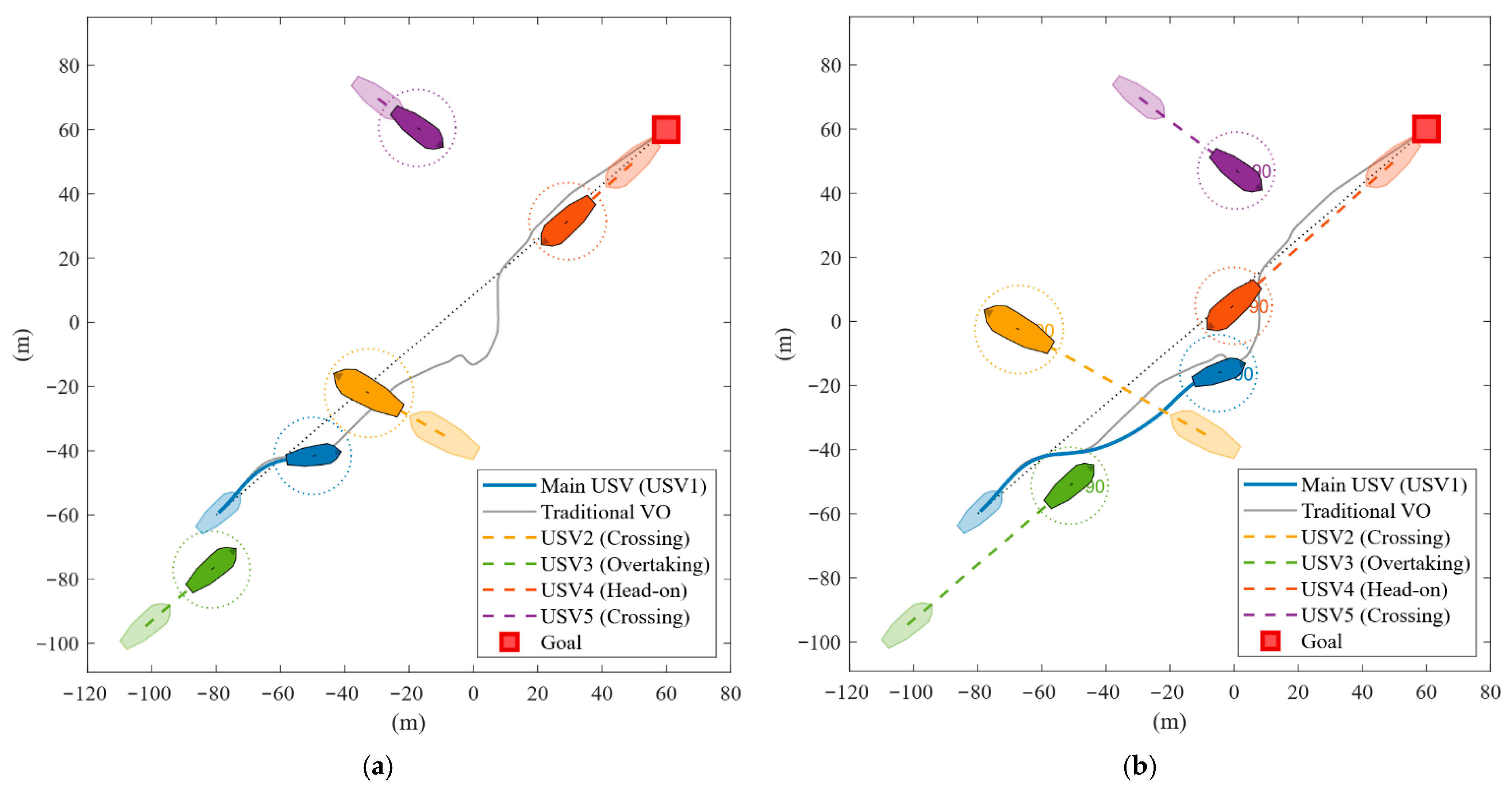

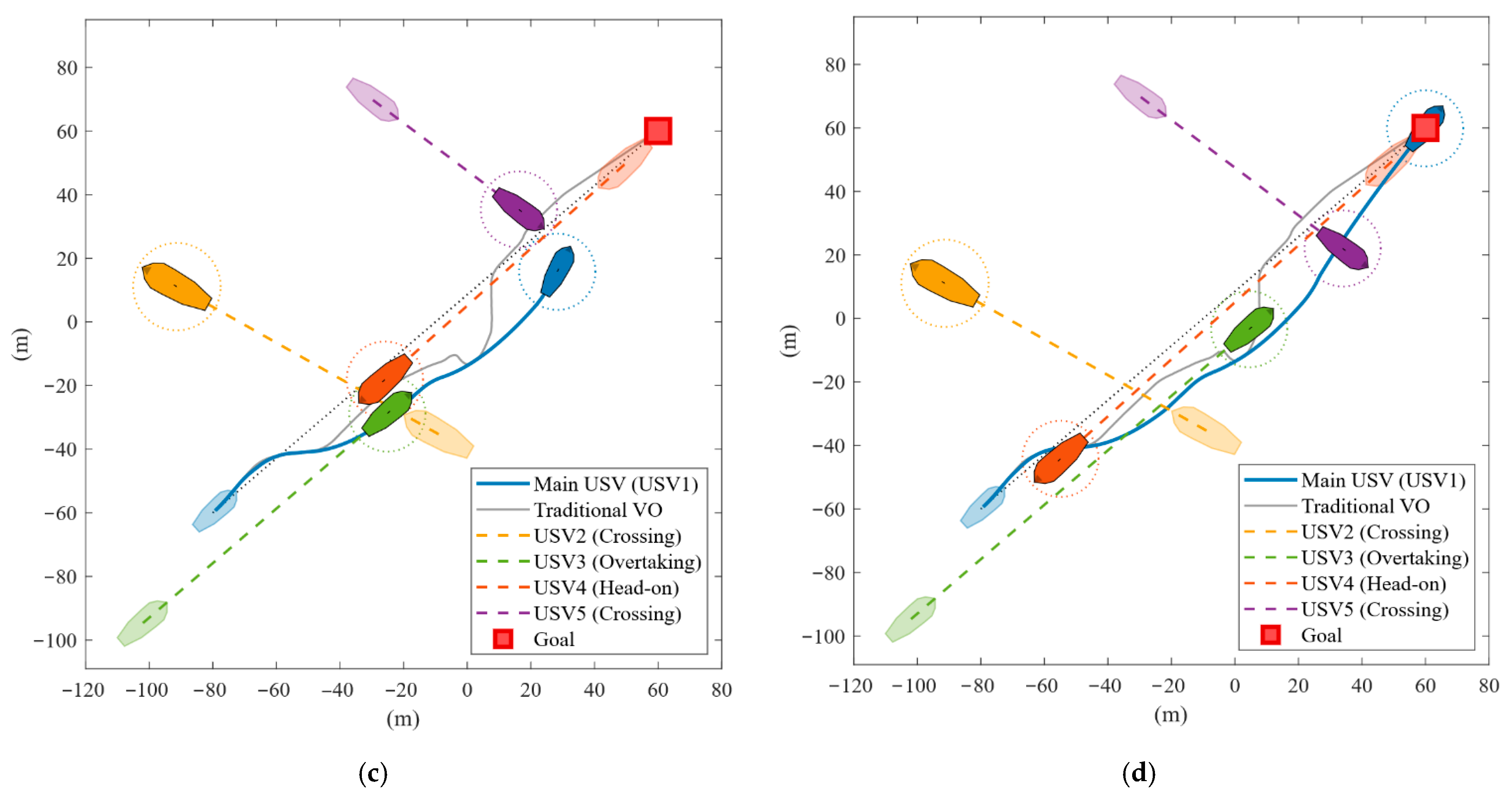

4.4. Multi-Vessel Encounter Scenarios in Simulation

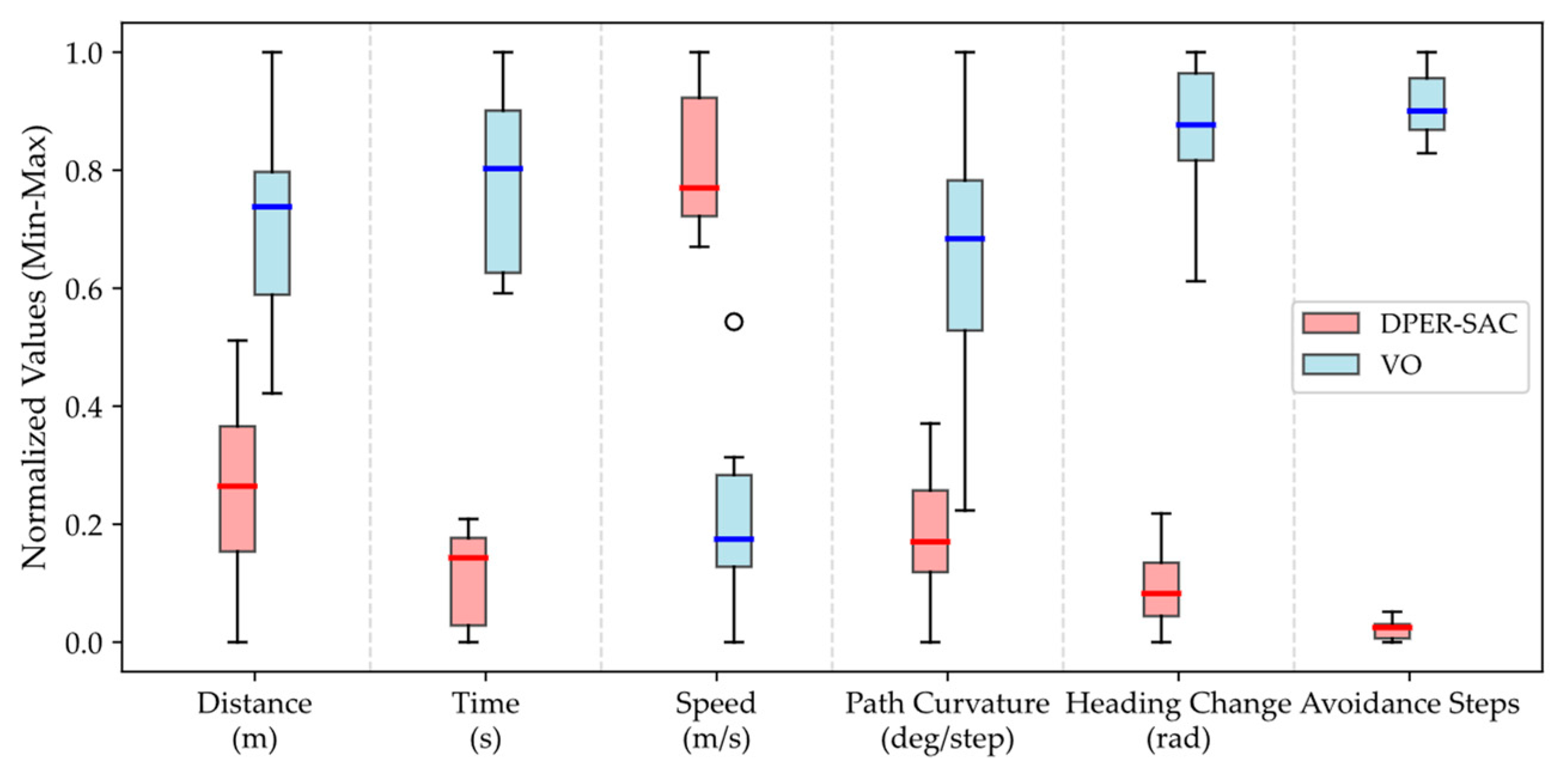

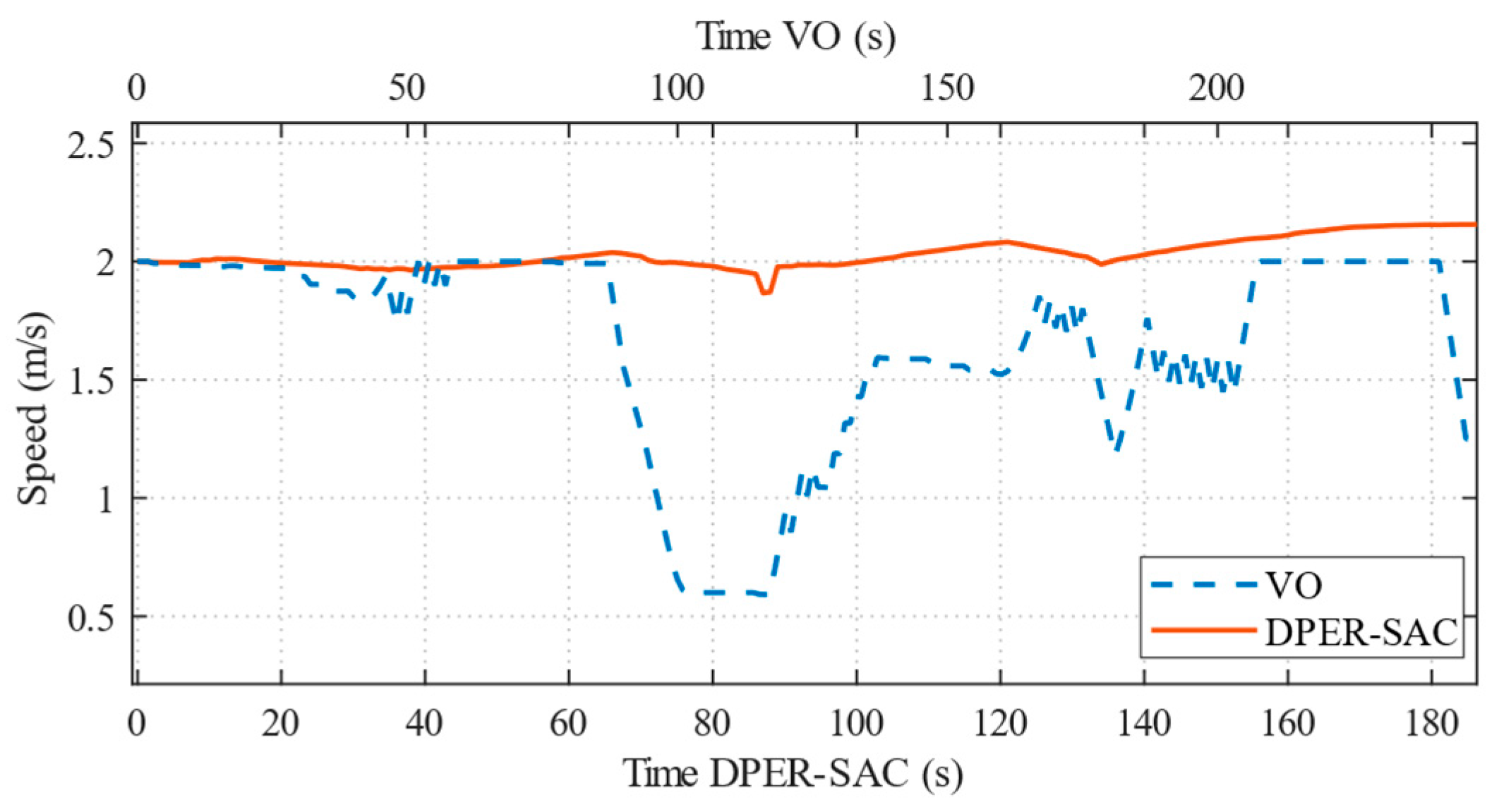

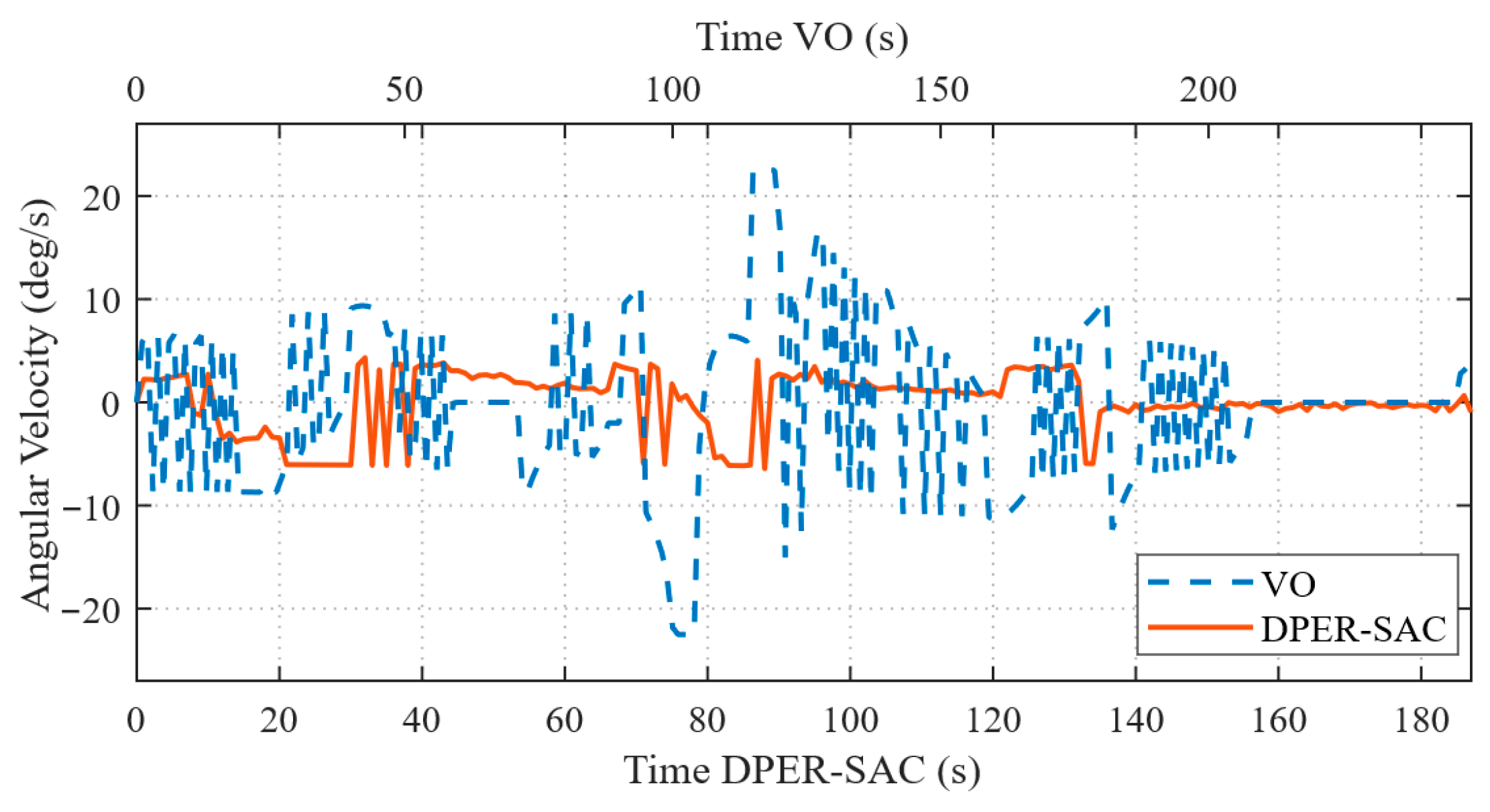

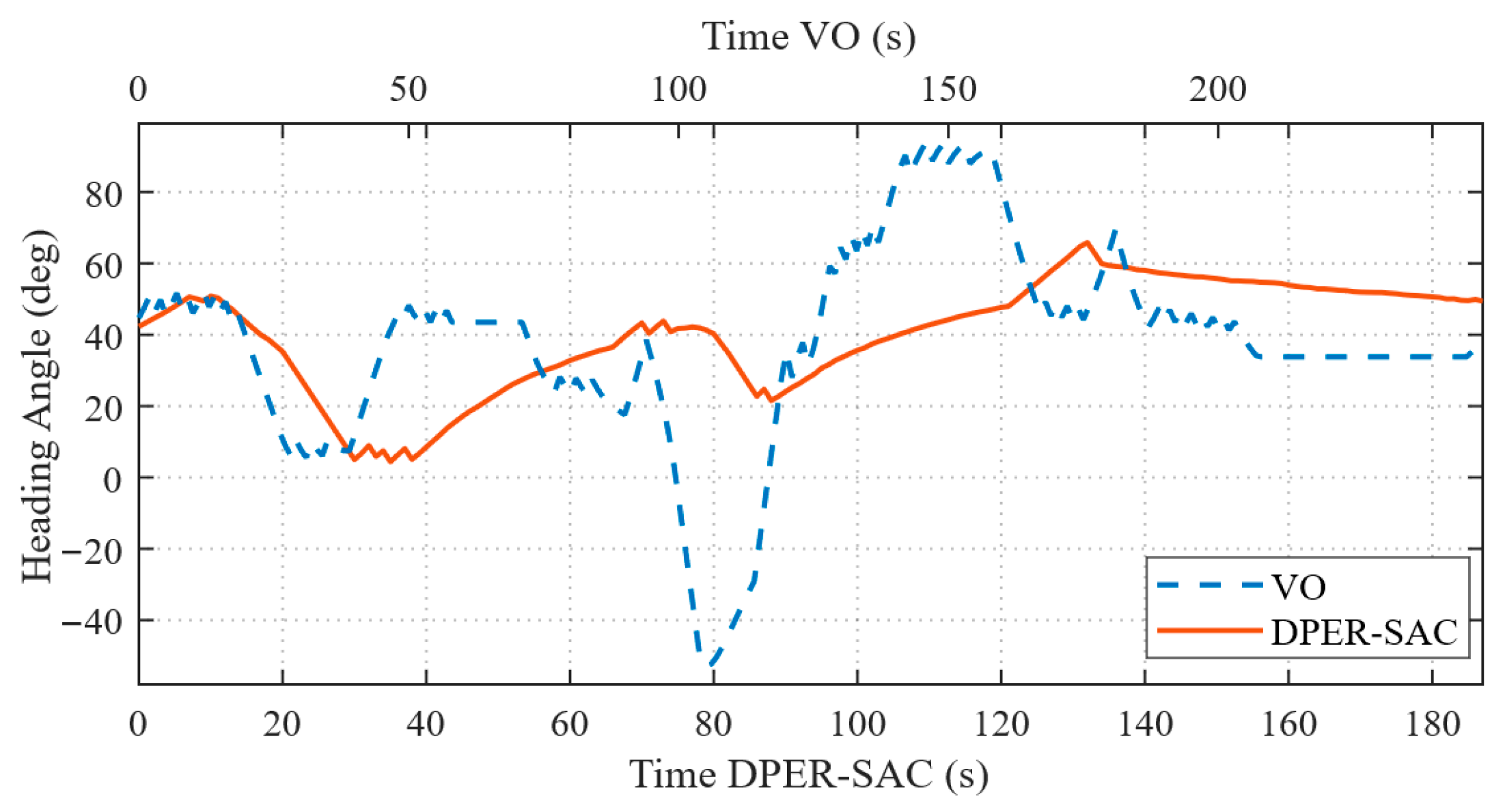

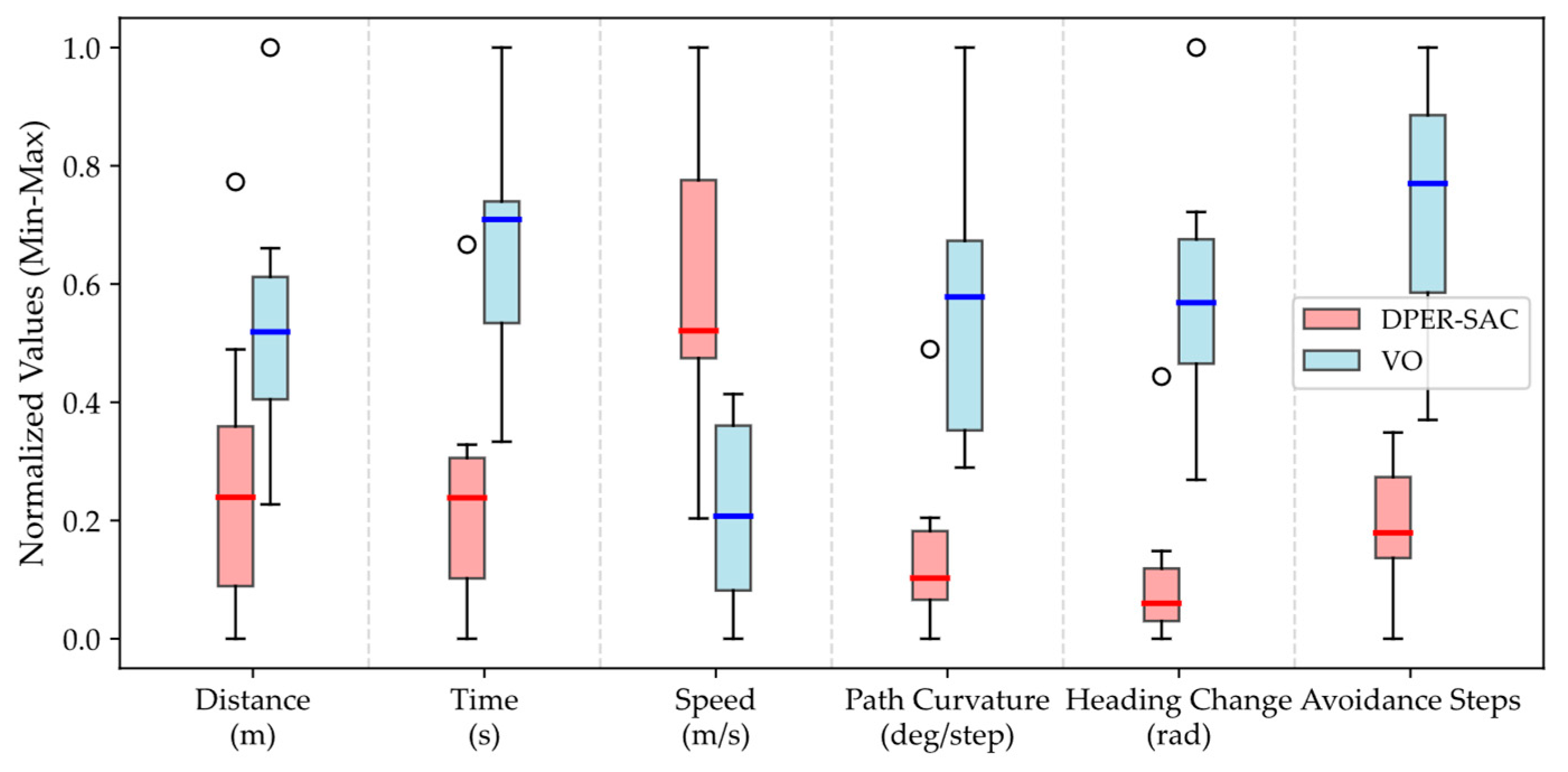

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sun, Z.; Sun, H.; Li, P.; Zou, J. Cooperative Strategy for Pursuit-Evasion Problem with Collision Avoidance. Ocean Eng. 2022, 266, 112742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Peng, Z.; Liu, L.; Wang, D. Data-Driven Distributed Formation Control of under-Actuated Unmanned Surface Vehicles with Collision Avoidance via Model-Based Deep Reinforcement Learning. Ocean Eng. 2023, 267, 113166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, R.; Zhu, F.; Yan, R.; Shang, Y. A Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning-Based Longitudinal and Lateral Control of CAVs to Improve Traffic Efficiency in a Mandatory Lane Change Scenario. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2024, 158, 104445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Li, H.; Gao, J.; Cui, R.; Xu, D. Economic MPC-Based Planning for Marine Vehicles: Tuning Safety and Energy Efficiency. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2023, 70, 10546–10556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Chi, R.; Huang, B.; Hou, Z. Finite-Time PID Control for Nonlinear Nonaffine Systems. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 2024, 67, 212206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Yu, C.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Z. Sliding Mode Control Strategy Based on Disturbance Observer for Permanent Magnet In-Wheel Motor. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Cheng, J.; Weng, Y. LOS Guidance Law for Unmanned Surface Vehicle Path Following with Unknown Time-Varying Sideslip Compensation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Neural Computing for Advanced Applications, Hefei, China, 7–9 July 2023; Zhang, H., Ke, Y., Wu, Z., Hao, T., Zhang, Z., Meng, W., Mu, Y., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 193–205. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Song, S.; Yuan, S.; Ma, Y.; Yao, Z. ALOS-Based USV Path-Following Control with Obstacle Avoidance Strategy. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celestini, D.; Gammelli, D.; Guffanti, T.; D’Amico, S.; Capello, E.; Pavone, M. Transformer-Based Model Predictive Control: Trajectory Optimization via Sequence Modeling. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 9820–9827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Yin, J.; Wang, W.; Duarte, F.; Yang, J.; Ratti, C. Survey of Deep Learning for Autonomous Surface Vehicles in Marine Environments. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 3678–3701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronauer, S.; Diepold, K. Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning: A Survey. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2022, 55, 895–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, F.; Ball, J.E.; Goodin, C.T. Enhancing Longitudinal Velocity Control with Attention Mechanism-Based Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) for Safety and Comfort. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 30765–30780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Guan, W.; Luo, W.; Zhang, X. Intelligent Navigation Method for Multiple Marine Autonomous Surface Vessels Based on Improved PPO Algorithm. Ocean Eng. 2023, 287, 115783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Dai, J.; Jiang, B.; Karimi, H.R. Robot Path Planning Based on Artificial Potential Field with Deterministic Annealing. ISA Trans. 2023, 138, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dao, T.-K.; Ngo, T.-G.; Pan, J.-S.; Nguyen, T.-T.-T.; Nguyen, T.-T. Enhancing Path Planning Capabilities of Automated Guided Vehicles in Dynamic Environments: Multi-Objective PSO and Dynamic-Window Approach. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zeng, J.; Chi, X.; Sreenath, K.; Liu, Z.; Su, H. Dynamic Collision Avoidance Using Velocity Obstacle-Based Control Barrier Functions. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2025, 33, 1601–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, R.; Lu, D.; Zhou, H.; Tao, T. USV Dynamic Accurate Obstacle Avoidance Based on Improved Velocity Obstacle Method. Electronics 2022, 11, 2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, D. Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Obstacle Avoidance Based Custom Elliptic Domain. Drones 2024, 8, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.; Chen, S.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, R.; Hao, Q.; Pan, J. Reinforcement Learned Distributed Multi-Robot Navigation with Reciprocal Velocity Obstacle Shaped Rewards. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 5896–5903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Huang, L.; Liu, K.; Wu, X.; Wang, J. A COLREGs-Compliant Collision Avoidance Decision Approach Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyei, K.; Sarhadi, P.; Naeem, W. Large Language Model-Based Decision-Making for COLREGs and the Control of Autonomous Surface Vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2025 European Control Conference (ECC), Thessaloniki, Greece, 24–27 June 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, M.; Chen, X.; Li, Q. Formal Verification of Probabilistic Deep Reinforcement Learning Policies with Abstract Training. In Proceedings of the Verification, Model Checking, and Abstract Interpretation, Denver, CO, USA, 20–21 January 2025; Shankaranarayanan, K., Sankaranarayanan, S., Trivedi, A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 125–147. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Discount factor γ | 0.99 |

| Actor network learning rate | 0.0001 |

| Critic network learning rate | 0.0001 |

| Replay memory size | 100,000 |

| Batch size | 256 |

| Action Noise Standard Deviation | 0.3 |

| Soft update | 0.01 |

| Training episodes | 1500 |

| Hidden nodes | 128 |

| Vessel | Initial Position (m) | Initial Velocity (m/s) | Vessel Radius (m) | Safety Distance (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main USV | (−80,−60) | 1.80 | 5.0 | - |

| USV2 | (−57.6, 18.3) | 1.5 | 7.5 | 10.0 |

| USV3 | (59.7, −9.8) | 2.0 | 5.0 | 8.0 |

| Algorithm | Average Navigation Distance (m) | Average Navigation Time (s) | Average Speed (m/s) | Average Path Curvature (deg/Step) | Maximum Single-Step Heading Change (rad) | Minimum Avoidance State Time Steps |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DPER-SAC | 189.74 | 97.69 | 1.92 | 0.53 | 0.0574 | 38 (20.0%) |

| VO | 197.56 | 127.43 | 1.53 | 0.87 | 0.1432 | 145 (73.4%) |

| Vessel | Initial Position (m) | Initial Velocity (m/s) | Vessel Radius (m) | Safety Distance (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main USV | (−80.0, −60.0) | 1.80 | 5.0 | - |

| USV2 | (−9.2, −42.6) | 1.5 | 7.5 | 10.0 |

| USV3 | (−101.0, −96.7) | 1.6 | 5.0 | 8.0 |

| USV4 | (49.8, 47.3) | 1.5 | 6.0 | 9.0 |

| USV5 | (−28.1, −64.2) | 0.85 | 5.5 | 8.0 |

| Algorithm | Average Navigation Distance (m) | Average Navigation Time (s) | Average Speed (m/s) | Average Path Curvature (deg/Step) | Maximum Single-Step Heading Change (rad) | Minimum Avoidance State Time Steps |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DPER-SAC | 195.73 | 98.47 | 1.89 | 1.23 | 0.0556 | 76 (41.9%) |

| VO | 221.36 | 145.21 | 1.43 | 3.54 | 0.2183 | 182 (76.7%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xu, L.; Wang, Z.; Hong, Z.; Han, C.; Qin, J.; Yang, K. Research on Multi-USV Collision Avoidance Based on Priority-Driven and Expert-Guided Deep Reinforcement Learning. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2026, 14, 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14020197

Xu L, Wang Z, Hong Z, Han C, Qin J, Yang K. Research on Multi-USV Collision Avoidance Based on Priority-Driven and Expert-Guided Deep Reinforcement Learning. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2026; 14(2):197. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14020197

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Lixin, Zixuan Wang, Zhichao Hong, Chaoshuai Han, Jiarong Qin, and Ke Yang. 2026. "Research on Multi-USV Collision Avoidance Based on Priority-Driven and Expert-Guided Deep Reinforcement Learning" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 14, no. 2: 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14020197

APA StyleXu, L., Wang, Z., Hong, Z., Han, C., Qin, J., & Yang, K. (2026). Research on Multi-USV Collision Avoidance Based on Priority-Driven and Expert-Guided Deep Reinforcement Learning. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 14(2), 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14020197