Climate-Driven Habitat Shifts in Brown Algal Forests: Insights from the Adriatic Sea

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

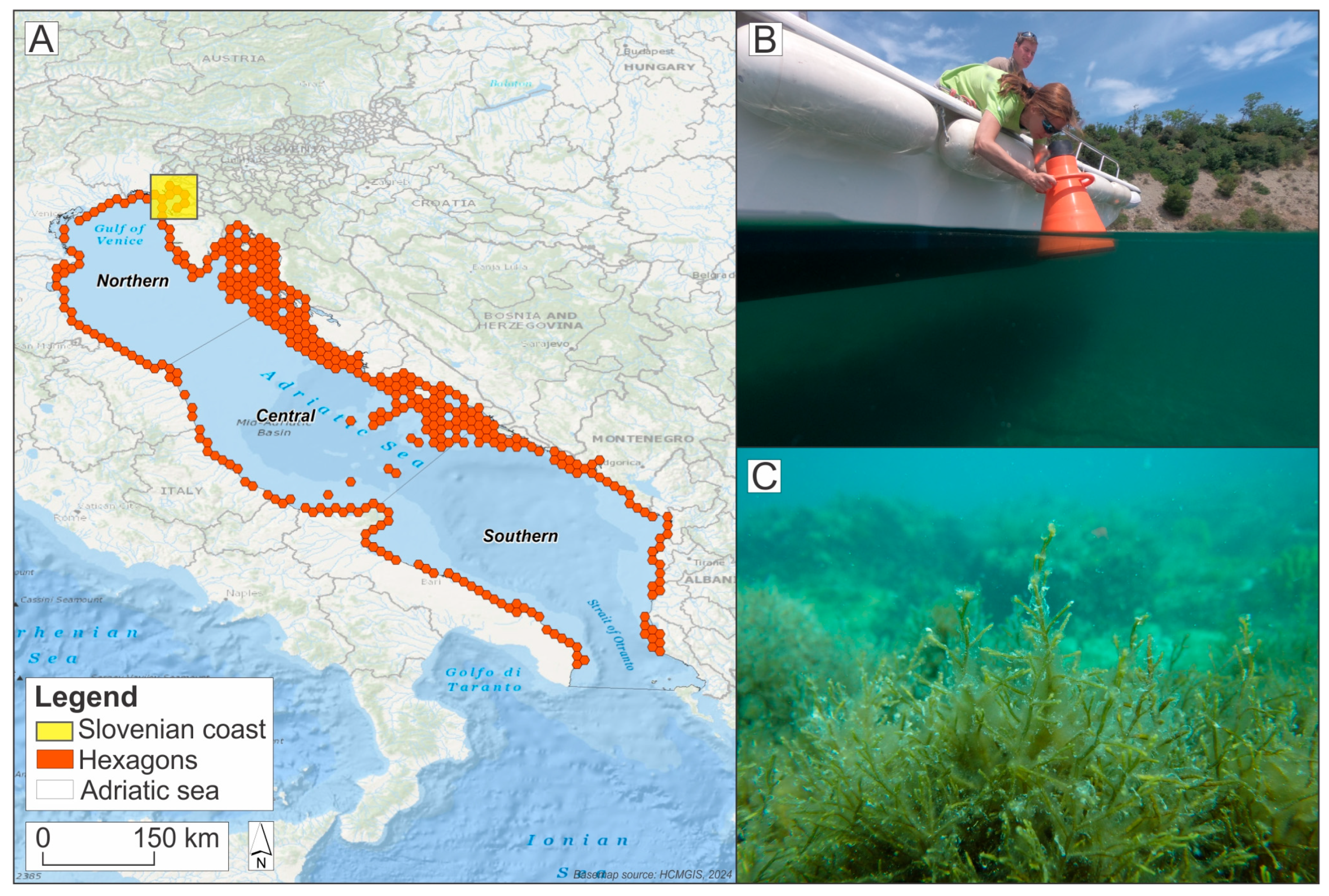

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Spatial Data Sets

2.2.1. Cartography of Benthic Vegetation Along the Slovenian Coastline

2.2.2. Brown Algal Forest Suitability Data for the Adriatic Sea

2.2.3. Environmental Variable Datasets for the Adriatic Sea

2.3. The Dependent Variable

2.4. The Predictors

2.5. Spatial Modelling and Prediction

3. Results

3.1. Brown Algal Forest Distribution Along the Slovenian Coastline—Data Validation for Modelling

3.2. Brown Algal Forest Suitability in the Adriatic Sea

3.3. Predictor Correlation Matrix

3.4. Model Comparison

3.5. Potential Brown Algal Forest Spatial Distribution Shifts

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bringloe, T.T.; Starko, S.; Wade, R.M.; Vieira, C.; Kawai, H.; De Clerck, O.; Cock, J.M.; Coelho, S.M.; Destombe, C.; Valero, M.; et al. Phylogeny and Evolution of the Brown Algae. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2020, 39, 281–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbrizzi, E.; Scardi, M.; Ballesteros, E.; Benedetti-Cecchi, L.; Cebrian, E.; Ceccherelli, G.; De Leo, F.; Deidun, A.; Guarnieri, G.; Falace, A.; et al. Modeling Macroalgal Forest Distribution at Mediterranean Scale: Present Status, Drivers of Changes and Insights for Conservation and Management. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaca, M.O.; Lipej, L. Factors Affecting Habitat Occupancy of Fish Assemblage in the Gulf of Trieste (Northern Adriatic Sea). Mar. Ecol. 2005, 26, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mačić, V.; Svirčev, Z. Macroepiphytes on Cystoseira Species (Phaeophyceae) on the Coast of Montenegro. Fresenius Environ. Bull. 2014, 23, 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Pitacco, V.; Orlando-Bonaca, M.; Mavrič, B.; Popović, A.; Lipej, L. Mollusc Fauna Associated with the Cystoseira Algal Associations in the Gulf of Trieste (Northern Adriatic Sea). Medit. Mar. Sci. 2014, 15, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piazzi, L.; Bonaviri, C.; Castelli, A.; Ceccherelli, G.; Costa, G.; Curini-Galletti, M.; Langeneck, J.; Manconi, R.; Montefalcone, M.; Pipitone, C.; et al. Biodiversity in Canopy-Forming Algae: Structure and Spatial Variability of the Mediterranean Cystoseira Assemblages. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2018, 207, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheminée, A.; Sala, E.; Pastor, J.; Bodilis, P.; Thiriet, P.; Mangialajo, L.; Cottalorda, J.-M.; Francour, P. Nursery Value of Cystoseira Forests for Mediterranean Rocky Reef Fishes. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2013, 442, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchelli, S.; Danovaro, R. Impairment of Microbial and Meiofaunal Ecosystem Functions Linked to Algal Forest Loss. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 19970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancuso, F.P.; Milazzo, M.; Chemello, R. Decreasing in Patch-Size of Cystoseira Forests Reduces the Diversity of Their Associated Molluscan Assemblage in Mediterranean Rocky Reefs. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2021, 250, 107163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlando-Bonaca, M.; Trkov, D.; Klun, K.; Pitacco, V. Diversity of Molluscan Assemblage in Relation to Biotic and Abiotic Variables in Brown Algal Forests. Plants 2022, 11, 2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipej, L.; Ivajnšič, D.; Pitacco, V.; Trkov, D.; Mavrič, B.; Orlando-Bonaca, M. Coastal Fish Fauna in the Cystoseira s.l. Algal Belts: Experiences from the Northern Adriatic Sea. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peleg, O.; Guy-Haim, T.; Yeruham, E.; Silverman, J.; Rilov, G. Tropicalization May Invert Trophic State and Carbon Budget of Shallow Temperate Rocky Reefs. J. Ecol. 2020, 108, 844–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, P.H.; Roberts, B.P.; Moore, P.J.; Pike, S.; Scarth, A.; Medcalf, K.; Cameron, I. Combining Unmanned Aerial Vehicles and Satellite Imagery to Quantify Areal Extent of Intertidal Brown Canopy-forming Macroalgae. Remote Sens. Ecol. Conserv. 2023, 9, 540–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbrizzi, E.; Giakoumi, S.; De Leo, F.; Tamburello, L.; Chiarore, A.; Colletti, A.; Coppola, M.; Munari, M.; Musco, L.; Rindi, F. The Challenge of Setting Restoration Targets for Macroalgal Forests under Climate Changes. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 326, 116834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, F.P.; Sarà, G.; Mannino, A.M. Diversity and Distribution of Intertidal Cystoseira Sensu Lato Species Across Protection Zones in a Mediterranean Marine Protected Area. Plants 2024, 13, 3562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno de Sousa, C.; Gangadhar, K.N.; Macridachis, J.; Pavão, M.; Morais, T.R.; Campino, L.; Varela, J.; Lago, J.H.G. Cystoseira Algae (Fucaceae): Update on Their Chemical Entities and Biological Activities. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 2017, 28, 1486–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Fuente, G.; Fontana, M.; Asnaghi, V.; Chiantore, M.; Mirata, S.; Salis, A.; Damonte, G.; Scarfì, S. The Remarkable Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Potential of the Extracts of the Brown Alga Cystoseira Amentacea Var. Stricta. Mar. Drugs 2020, 19, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannino, A.M.; Micheli, C. Ecological Function of Phenolic Compounds from Mediterranean Fucoid Algae and Seagrasses: An Overview on the Genus Cystoseira Sensu Lato and Posidonia Oceanica (L.) Delile. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orfanidis, S.; Panayotidis, P.; Stamatis, N. Ecological Evaluation of Transitional and Coastal Waters: A Marine Benthic Macrophytes-Based Model. Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2001, 2, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orfanidis, S.; Panayotidis, P.; Ugland, K. Ecological Evaluation Index Continuous Formula (EEI-c) Application: A Step Forward for Functional Groups, the Formula and Reference Condition Values. Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2011, 12, 199–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlando-Bonaca, M.; Lipej, L.; Orfanidis, S. Benthic Macrophytes as a Tool for Delineating, Monitoring and Assessing Ecological Status: The Case of Slovenian Coastal Waters. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2008, 56, 666–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlando-Bonaca, M.; Pitacco, V.; Lipej, L. Loss of Canopy-Forming Algal Richness and Coverage in the Northern Adriatic Sea. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 125, 107501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iveša, L.; Djakovac, T.; Devescovi, M. Long-Term Fluctuations in Cystoseira Populations along the West Istrian Coast (Croatia) Related to Eutrophication Patterns in the Northern Adriatic Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016, 106, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment and the Coastal Region of the Mediterranean and Its Protocols 2019; United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP): Nairobi, Kenya, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats (Bern Convention); Council of Europe: Bern, Switzerland, 1979; Entered into Force 1 June 1982. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/bern-convention (accessed on 10 January 2026).

- Verdura, J.; Rehues, L.; Mangialajo, L.; Fraschetti, S.; Belattmania, Z.; Bianchelli, S.; Blanfuné, A.; Sabour, B.; Chiarore, A.; Danovaro, R.; et al. Distribution, Health and Threats to Mediterranean Macroalgal Forests: Defining the Baselines for Their Conservation and Restoration. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1258842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airoldi, L.; Beck, M.W. Loss, Status and Trends for Coastal Marine Habitats of Europe. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. 2007, 45, 345–405. [Google Scholar]

- Mangialajo, L.; Chiantore, M.; Cattaneo-Vietti, R. Loss of Fucoid Algae along a Gradient of Urbanisation, and Structure of Benthic Assemblages. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2008, 358, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airoldi, L.; Bulleri, F. Anthropogenic Disturbance Can Determine the Magnitude of Opportunistic Species Responses on Marine Urban Infrastructures. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e22985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airoldi, L.; Ballesteros, E.; Buonuomo, R.; Van Belzen, J.; Bouma, T.J.; Cebrian, E.; De Clerk, O.; Engelen, A.H.; Ferrario, F.; Fraschetti, S. Marine Forests at Risk: Solutions to Halt the Loss and Promote the Recovery of Mediterranean Canopy-Forming Seaweeds. In Proceedings of the 5th Mediterranean Symposium on Marine Vegetation, Slovenia, Portorož, 27–28 October 2014; pp. 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Thibaut, T.; Blanfuné, A.; Boudouresque, C.-F.; Verlaque, M. Decline and Local Extinction of Fucales in the French Riviera: The Harbinger of Future Extinctions? Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2015, 16, 206–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rindi, L.; Dal Bello, M.; Benedetti-Cecchi, L. Experimental Evidence of Spatial Signatures of Approaching Regime Shifts in Macroalgal Canopies. Ecology 2018, 99, 1709–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orfanidis, S.; Rindi, F.; Cebrian, E.; Fraschetti, S.; Nasto, I.; Taskin, E.; Bianchelli, S.; Papathanasiou, V.; Kosmidou, M.; Caragnano, A.; et al. Effects of Natural and Anthropogenic Stressors on Fucalean Brown Seaweeds Across Different Spatial Scales in the Mediterranean Sea. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 658417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanfuné, A.; Boudouresque, C.-F.; Verlaque, M.; Thibaut, T. Severe Decline of Gongolaria Barbata (Fucales) along Most of the French Mediterranean Coast. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlando-Bonaca, M.; Rotter, A. Any Signs of Replacement of Canopy-Forming Algae by Turf-Forming Algae in the Northern Adriatic Sea? Ecol. Indic. 2018, 87, 272–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iveša, L. Effects of Increased Seawater Temperature and Benthic Mucilage Formation on Shallow Cystoseira Forests of the West Istrian Coast (Northern Adriatic Sea). Eur. J. Phycol. 2019, 54, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falace, A.; Alongi, G.; Orlando-Bonaca, M.; Bevilacqua, S. Species Loss and Decline in Taxonomic Diversity of Macroalgae in the Gulf of Trieste (Northern Adriatic Sea) over the Last Six Decades. Mar. Environ. Res. 2024, 202, 106828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffy, J.E.; Benedetti-Cecchi, L.; Trinanes, J.; Muller-Karger, F.E.; Ambo-Rappe, R.; Boström, C.; Buschmann, A.H.; Byrnes, J.; Coles, R.G.; Creed, J.; et al. Toward a Coordinated Global Observing System for Seagrasses and Marine Macroalgae. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019, 6, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassoun, A.E.R.; Mojtahid, M.; Merheb, M.; Lionello, P.; Gattuso, J.-P.; Cramer, W. Climate Change Risks on Key Open Marine and Coastal Mediterranean Ecosystems. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 24907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airoldi, L.; Balata, D.; Beck, M.W. The Gray Zone: Relationships between Habitat Loss and Marine Diversity and Their Applications in Conservation. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2008, 366, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkol-Finkel, S.; Airoldi, L. Loss and Recovery Potential of Marine Habitats: An Experimental Study of Factors Maintaining Resilience in Subtidal Algal Forests at the Adriatic Sea. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e10791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connell, S.D.; Foster, M.S.; Airoldi, L. What Are Algal Turfs? Towards a Better Description of Turfs. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2014, 495, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolić, V.; Žuljević, A.; Mangialajo, L.; Antolić, B.; Kušpilić, G.; Ballesteros, E. Cartography of Littoral Rocky-Shore Communities (CARLIT) as a Tool for Ecological Quality Assessment of Coastal Waters in the Eastern Adriatic Sea. Ecol. Indic. 2013, 34, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianni, F.; Bartolini, F.; Pey, A.; Laurent, M.; Martins, G.M.; Airoldi, L.; Mangialajo, L. Threats to Large Brown Algal Forests in Temperate Seas: The Overlooked Role of Native Herbivorous Fish. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 6012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlando-Bonaca, M.; Pitacco, V.; Slavinec, P.; Šiško, M.; Makovec, T.; Falace, A. First Restoration Experiment for Gongolaria Barbata in Slovenian Coastal Waters. What Can Go Wrong? Plants 2021, 10, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savonitto, G.; De La Fuente, G.; Tordoni, E.; Ciriaco, S.; Srijemsi, M.; Bacaro, G.; Chiantore, M.; Falace, A. Addressing Reproductive Stochasticity and Grazing Impacts in the Restoration of a Canopy-forming Brown Alga by Implementing Mitigation Solutions. Aquat. Conserv. 2021, 31, 1611–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airoldi, L. The Effects of Sedimentation on Rocky Coast Assemblages. In Oceanography and Marine Biology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2003; pp. 169–171. [Google Scholar]

- Savonitto, G.; Alongi, G.; Falace, A. Reproductive Phenology, Zygote Embryology and Germling Development of the Threatened Carpodesmia Barbatula (=Cystoseira Barbatula) (Fucales, Phaeophyta) towards Its Possible Restoration. Webbia 2019, 74, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, S.; Savonitto, G.; Lipizer, M.; Mancuso, P.; Ciriaco, S.; Srijemsi, M.; Falace, A. Climatic Anomalies May Create a Long-lasting Ecological Phase Shift by Altering the Reproduction of a Foundation Species. Ecology 2019, 100, e02838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdura, J.; Santamaría, J.; Ballesteros, E.; Smale, D.A.; Cefalì, M.E.; Golo, R.; De Caralt, S.; Vergés, A.; Cebrian, E. Local-scale Climatic Refugia Offer Sanctuary for a Habitat-forming Species during a Marine Heatwave. J. Ecol. 2021, 109, 1758–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouvêa, L.P.; Schubert, N.; Martins, C.D.L.; Sissini, M.; Ramlov, F.; Rodrigues, E.R.D.O.; Bastos, E.O.; Freire, V.C.; Maraschin, M.; Carlos Simonassi, J.; et al. Interactive Effects of Marine Heatwaves and Eutrophication on the Ecophysiology of a Widespread and Ecologically Important Macroalga. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2017, 62, 2056–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bettignies, T.; Wernberg, T.; Gurgel, C.F.D. Exploring the Influence of Temperature on Aspects of the Reproductive Phenology of Temperate Seaweeds. Front. Mar. Sci. 2018, 5, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonomo, R.; Chefaoui, R.M.; Lacida, R.B.; Engelen, A.H.; Serrão, E.A.; Airoldi, L. Predicted Extinction of Unique Genetic Diversity in Marine Forests of Cystoseira spp. Mar. Environ. Res. 2018, 138, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergés, A.; Doropoulos, C.; Malcolm, H.A.; Skye, M.; Garcia-Pizá, M.; Marzinelli, E.M.; Campbell, A.H.; Ballesteros, E.; Hoey, A.S.; Vila-Concejo, A.; et al. Long-Term Empirical Evidence of Ocean Warming Leading to Tropicalization of Fish Communities, Increased Herbivory, and Loss of Kelp. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 13791–13796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernberg, T.; Bennett, S.; Babcock, R.C.; De Bettignies, T.; Cure, K.; Depczynski, M.; Dufois, F.; Fromont, J.; Fulton, C.J.; Hovey, R.K.; et al. Climate-Driven Regime Shift of a Temperate Marine Ecosystem. Science 2016, 353, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergés, A.; Steinberg, P.D.; Hay, M.E.; Poore, A.G.B.; Campbell, A.H.; Ballesteros, E.; Heck, K.L.; Booth, D.J.; Coleman, M.A.; Feary, D.A.; et al. The Tropicalization of Temperate Marine Ecosystems: Climate-Mediated Changes in Herbivory and Community Phase Shifts. Proc. R. Soc. B 2014, 281, 20140846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straub, S.C.; Wernberg, T.; Thomsen, M.S.; Moore, P.J.; Burrows, M.T.; Harvey, B.P.; Smale, D.A. Resistance, Extinction, and Everything in Between—The Diverse Responses of Seaweeds to Marine Heatwaves. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019, 6, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smale, D.A.; Burrows, M.T.; Moore, P.; O’Connor, N.; Hawkins, S.J. Threats and Knowledge Gaps for Ecosystem Services Provided by Kelp Forests: A Northeast Atlantic Perspective. Ecol. Evol. 2013, 3, 4016–4038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falace, A.; Kaleb, S.; De La Fuente, G.; Asnaghi, V.; Chiantore, M. Ex Situ Cultivation Protocol for Cystoseira Amentacea Var. Stricta (Fucales, Phaeophyceae) from a Restoration Perspective. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0193011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lokovšek, A.; Orlando-Bonaca, M.; Gljušćić, E.; Bilajac, A.; Iveša, L.; Di Cave, A.; Savio, S.; Ortenzi, F.; Trkov, D.; Congestri, R.; et al. Enhancing Ex Situ Cultivation of Mediterranean Fucales: Species-Specific Responses of Gongolaria Barbata and Ericaria Crinita Seedlings to Algal Extracts. Mar. Environ. Res. 2025, 211, 107411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verdura, J.; Sales, M.; Ballesteros, E.; Cefalì, M.E.; Cebrian, E. Restoration of a Canopy-Forming Alga Based on Recruitment Enhancement: Methods and Long-Term Success Assessment. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Fuente, G.; Chiantore, M.; Asnaghi, V.; Kaleb, S.; Falace, A. First Ex Situ Outplanting of the Habitat-Forming Seaweed Cystoseira Amentacea Var. Stricta from a Restoration Perspective. PeerJ 2019, 7, e7290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medrano, A.; Hereu, B.; Cleminson, M.; Pagès-Escolà, M.; Rovira, G.; Solà, J.; Linares, C. From Marine Deserts to Algal Beds: Treptacantha Elegans Revegetation to Reverse Stable Degraded Ecosystems inside and Outside a No-Take Marine Reserve. Restor. Ecol. 2020, 28, 632–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlando-Bonaca, M.; Savonitto, G.; Asnaghi, V.; Trkov, D.; Pitacco, V.; Šiško, M.; Makovec, T.; Slavinec, P.; Lokovšek, A.; Ciriaco, S.; et al. Where and How—New Insight for Brown Algal Forest Restoration in the Adriatic. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 988584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokovšek, A.; Pitacco, V.; Trkov, D.; Zamuda, L.L.; Falace, A.; Orlando-Bonaca, M. Keep It Simple: Improving the Ex Situ Culture of Cystoseira s.l. to Restore Macroalgal Forests. Plants 2023, 12, 2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.J.; Verdura, J.; Papadopoulou, N.; Fraschetti, S.; Cebrian, E.; Fabbrizzi, E.; Monserrat, M.; Drake, M.; Bianchelli, S.; Danovaro, R.; et al. A Decision-Support Framework for the Restoration of Cystoseira Sensu Lato Forests. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1159262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iveša, L.; Bilajac, A.; Gljušćić, E.; Najdek, M. Gongolaria Barbata Forest in the Shallow Lagoon on the Southern Istrian Coast (Northern Adriatic Sea). Bot. Mar. 2022, 65, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordoni, F. Integrating Benthic Habitat Mapping for Macroalgal Forest Monitoring in the Mediterranean. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2025, 290, 106785. [Google Scholar]

- Poursanidis, D.; Katsanevakis, S. Mapping Subtidal Marine Forests in the Mediterranean Sea Using Copernicus Contributing Mission. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragkopoulou, E.; Serrão, E.A.; De Clerck, O.; Costello, M.J.; Araújo, M.B.; Duarte, C.M.; Krause-Jensen, D.; Assis, J. Global Biodiversity Patterns of Marine Forests of Brown Macroalgae. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2022, 31, 636–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boicourt, W.C.; Ličer, M.; Li, M.; Vodopivec, M.; Malačič, V. Sea State: Recent Progress in the Context of Climate Change. In Coastal Ecosystems in Transition: A Comparative Analysis of the Northern Adriatic and Chesapeake Bay; Geophysical Monograph Series; Malone, T.C., Malej, A., Faganeli, J., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 21–48. ISBN 978-1-119-54358-9. [Google Scholar]

- Artegiani, A.; Paschini, E.; Russo, A.; Bregant, D.; Raicich, F.; Pinardi, N. The Adriatic Sea General Circulation. Part I: Air–Sea Interactions and Water Mass Structure. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 1997, 27, 1492–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlic, M.; Gacic, M.; Laviolette, P.E. The Currents and Circulation of the Adriatic Sea. Oceanol. Acta 1992, 15, 109–124. [Google Scholar]

- Conversi, A.; Peluso, T.; Fonda-Umani, S. Gulf of Trieste: A Changing Ecosystem. J. Geophys. Res. 2009, 114, 2008JC004763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malačič, V.; Petelin, B. Climatic Circulation in the Gulf of Trieste (Northern Adriatic). J. Geophys. Res. 2009, 114, 2008JC004904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malej, A.; Malacic, V. Factors Affecting Bottom Layer Oxygen Depletion in the Gulf of Trieste (Adriatic Sea). Ann. An. Istrske Mediter. Stud. (Hist. Nat.) 1995, 6, 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Ličer, M.; Smerkol, P.; Fettich, A.; Ravdas, M.; Papapostolou, A.; Mantziafou, A.; Strajnar, B.; Cedilnik, J.; Jeromel, M.; Jerman, J.; et al. Modeling the Ocean and Atmosphere during an Extreme Bora Event in Northern Adriatic Using One-Way and Two-Way Atmosphere–Ocean Coupling. Ocean Sci. 2016, 12, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa, V.S.; Alessandri, J.; Verri, G.; Mentaschi, L.; Guerra, R.; Pinardi, N. Marine Climate Indicators in the Adriatic Sea. Front. Clim. 2024, 6, 1449633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros, E.; Torras, X.; Pinedo, S.; García, M.; Mangialajo, L.; De Torres, M. A New Methodology Based on Littoral Community Cartography Dominated by Macroalgae for the Implementation of the European Water Framework Directive. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2007, 55, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QGIS Development Team. QGIS Geographic Information System. 2024. Available online: https://www.qgis.org/ (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Assis, J.; Fernández Bejarano, S.J.; Salazar, V.W.; Schepers, L.; Gouvêa, L.; Fragkopoulou, E.; Leclercq, F.; Vanhoorne, B.; Tyberghein, L.; Serrão, E.A.; et al. Bio-ORACLE v3.0. Pushing Marine Data Layers to the CMIP6 Earth System Models of Climate Change Research. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2024, 33, e13813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, G.G.; Hermans, T.; Kopp, R.E.; Slangen, A.B.A.; Edwards, T.L.; Levermann, A.; Nowicki, S.; Palmer, M.D.; Smith, C.; Fox-Kemper, B.; et al. IPCC AR6 Sea Level Projections 2021. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/5914710 (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Fox-Kemper, B.; Hewitt, C.; Xiao, G.; Aðalgeirsdóttir, S.S.; Drijfhout, T.L.; Edwards, N.R.; Golledge, M.; Hemer, R.E.; Kopp, G.; Krinner, A.; et al. Ocean, Cryosphere and Sea Level Change; Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2023; ISBN 978-1-009-15789-6. [Google Scholar]

- Kopp, R.E.; Garner, G.G.; Hermans, T.H.J.; Jha, S.; Kumar, P.; Reedy, A.; Slangen, A.B.A.; Turilli, M.; Edwards, T.L.; Gregory, J.M.; et al. The Framework for Assessing Changes To Sea-Level (FACTS) v1.0: A Platform for Characterizing Parametric and Structural Uncertainty in Future Global, Relative, and Extreme Sea-Level Change. Geosci. Model. Dev. 2023, 16, 7461–7489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Land Copernicus CORINE Land Cover. Available online: https://land.copernicus.eu/en/products/corine-land-cover (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- R Development Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing 2025. Available online: https://www.r-project.org (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Fox, J.; Marquez, M.M.; Bouchet-Vala, M. Rcmdr: R Commander. R Package Version 2.9-5 2024. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/Rcmdr/Rcmdr.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Salmerón-Gómez, R.; García-García, C.B.; García-Pérez, J. A Redefined Variance Inflation Factor: Overcoming the Limitations of the Variance Inflation Factor. Comput. Econ. 2025, 65, 337–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bio-ORACLE consortium BioORACLE. Available online: https://www.bio-oracle.org/ (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- NASA. IPCC Sea Level Projection Tool. Available online: https://sealevel.nasa.gov/ipcc-ar6-sea-level-projection-tool (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Oshan, T.; Li, Z.; Kang, W.; Wolf, L.; Fotheringham, A. Mgwr: A Python Implementation of Multiscale Geographically Weighted Regression for Investigating Process Spatial Heterogeneity and Scale. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2019, 8, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotheringham, A.S.; Oshan, T.M.; Li, Z. Multiscale Geographically Weighted Regression: Theory and Practice; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023; ISBN 1-003-43546-7. [Google Scholar]

- Oxoli, D.; Prestifilippo, G.; Bertocchi, D. Enabling Spatial Autocorrelation Mapping in QGIS: The Hotspot Analysis Plugin. Geoing. Ambient. E Mineraria (GEAM) 2017, 151, 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Falace, A.; Alongi, G.; Cormaci, M.; Furnari, G.; Curiel, D.; Cecere, E.; Petrocelli, A. Changes in the Benthic Algae along the Adriatic Sea in the Last Three Decades. Chem. Ecol. 2010, 26, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falace, A.; Manfrin, C.; Furnari, G.; D’Ambros Burchio, S.; Pallavicini, A.; Descourvieres, E.; Kaleb, S.; Lokovšek, A.; Grech, D.; Alongi, G. Contribution to the Knowledge of Gongolaria Barbata (Sargassaceae, Fucales) from the Mediterranean: Insights into Infraspecific Diversity. Phytotaxa 2024, 635, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebrian, E.; Tamburello, L.; Verdura, J.; Guarnieri, G.; Medrano, A.; Linares, C.; Hereu, B.; Garrabou, J.; Cerrano, C.; Galobart, C.; et al. A Roadmap for the Restoration of Mediterranean Macroalgal Forests. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 709219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokovšek, A.; Pitacco, V.; Falace, A.; Trkov, D.; Orlando-Bonaca, M. Too Hot to Handle: Effects of Water Temperature on the Early Life Stages of Gongolaria Barbata (Fucales). J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurelle, D.; Thomas, S.; Albert, C.; Bally, M.; Bondeau, A.; Boudouresque, C.; Cahill, A.E.; Carlotti, F.; Chenuil, A.; Cramer, W.; et al. Biodiversity, Climate Change, and Adaptation in the Mediterranean. Ecosphere 2022, 13, e3915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament EU Regulation 2024/1991 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 June 2024 on Nature Restoration and Amending Regulation (EU) 2022/869 2024. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2024/1991/oj/eng (accessed on 10 July 2025).

| N | Variable Name | Spatial Resolution | Source | Abbreviated Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Euclidean distance from urban land | 0.05 DD | Derived from Copernicus CLC2018 [85]; processed in QGIS [80] | ua_dis |

| 2 | Euclidean distance from coast | coast_dis | ||

| 3 | Euclidean distance from river | river_dis | ||

| 4 | Maximum ocean/sea temperature [°C] | BIOORACLE, 2025 [89] | t_max | |

| 5 | Sea water velocity [m·s−1] | swv | ||

| 6 | Sea water direction [degree] | swd | ||

| 7 | Silicate [mmol·m−3] | s | ||

| 8 | Mixed layer depth [m] | mld | ||

| 9 | Bathymetry [m] | bat | ||

| 10 | Maximum air temperature [°C] | at_max | ||

| 11 | Minimum pH | ph_min | ||

| 12 | Phosphate [mmol·m−3] | p | ||

| 13a | Medium confidence sea level, SSP2-4.5, 2020 | 0.25 DD | NASA, 2025 [90] | slr_2020_45_med_c |

| 13b | Medium confidence sea level, SSP5-8.5, 2020 | slr_2020_85_med_c |

| Variable | slr_2020_45_med_c | slr_2020_85_med_c | coast_dis | at_max | bat | mld | p | ph_min | s | swd | swv | t_max | river_dis | ua_dis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| slr_2020_45_med_c | 1.00 | 0.96 | 0.16 | 0.60 | 0.10 | −0.14 | −0.35 | −0.36 | −0.55 | 0.09 | 0.25 | 0.82 | 0.00 | −0.04 |

| slr_2020_85_med_c | 0.96 | 1.00 | 0.20 | 0.53 | 0.04 | −0.05 | −0.41 | −0.53 | −0.60 | 0.21 | 0.18 | 0.78 | −0.01 | −0.07 |

| coast_dis | 0.16 | 0.20 | 1.00 | 0.21 | −0.41 | 0.15 | −0.06 | −0.15 | −0.19 | 0.17 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.15 |

| at_max | 0.60 | 0.53 | 0.21 | 1.00 | −0.11 | 0.07 | −0.28 | −0.07 | −0.44 | −0.15 | 0.18 | 0.59 | 0.15 | 0.13 |

| bat | 0.10 | 0.04 | −0.41 | −0.11 | 1.00 | −0.59 | 0.15 | 0.35 | 0.32 | −0.25 | 0.18 | 0.16 | −0.22 | −0.26 |

| mld | −0.14 | −0.05 | 0.15 | 0.07 | −0.59 | 1.00 | −0.36 | −0.55 | −0.43 | 0.25 | −0.41 | −0.18 | 0.27 | 0.27 |

| p | −0.35 | −0.41 | −0.06 | −0.28 | 0.15 | −0.36 | 1.00 | 0.53 | 0.51 | −0.02 | 0.20 | −0.41 | −0.19 | −0.08 |

| ph_min | −0.36 | −0.53 | −0.15 | −0.07 | 0.35 | −0.55 | 0.53 | 1.00 | 0.60 | −0.47 | 0.38 | −0.21 | 0.08 | −0.01 |

| s | −0.55 | −0.60 | −0.19 | −0.44 | 0.32 | −0.43 | 0.51 | 0.60 | 1.00 | −0.42 | 0.32 | −0.44 | 0.16 | −0.10 |

| swd | 0.09 | 0.21 | 0.17 | −0.15 | −0.25 | 0.25 | −0.02 | −0.47 | −0.42 | 1.00 | −0.21 | −0.07 | −0.16 | 0.11 |

| swv | 0.25 | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.18 | 0.18 | −0.41 | 0.20 | 0.38 | 0.32 | −0.21 | 1.00 | 0.18 | 0.35 | −0.15 |

| t_max | 0.82 | 0.78 | 0.10 | 0.59 | 0.16 | −0.18 | −0.41 | −0.21 | −0.44 | −0.07 | 0.18 | 1.00 | −0.03 | 0.01 |

| river_dis | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.04 | 0.15 | −0.22 | 0.27 | −0.19 | 0.08 | 0.16 | −0.16 | 0.35 | −0.03 | 1.00 | 0.07 |

| ua_dis | −0.04 | −0.07 | 0.15 | 0.13 | −0.26 | 0.27 | −0.08 | −0.01 | −0.10 | 0.11 | −0.15 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 1.00 |

| GLM Coefficients | Estimate | Std. Error | t Value | Pr(>|t|) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.000 | 0.029 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |

| Z.slr_2020_45_med_c | 0.039 | 0.071 | 0.545 | 5.864 × 10−1 | |

| Z.ua_dis | 0.028 | 0.033 | 0.836 | 4.037 × 10−1 | |

| Z.coast_dis | −0.070 | 0.034 | −2.056 | 4.052 × 10−2 | * |

| Z.river_dis | 0.126 | 0.037 | 3.429 | 6.760 × 10−4 | *** |

| Z.p | 0.370 | 0.076 | 4.878 | 1.620 × 10−6 | *** |

| Z.ph_min | −0.478 | 0.082 | −5.814 | 1.360 × 10−8 | *** |

| Z.at_max | 0.005 | 0.044 | 0.122 | 9.028 × 10−1 | |

| Z.bat | −0.048 | 0.045 | −1.076 | 2.825 × 10−1 | |

| Z.mld | 0.433 | 0.058 | 7.427 | 8.230 × 10−13 | *** |

| Z.s | −0.219 | 0.051 | −4.269 | 2.520 × 10−5 | *** |

| Z.swd | 0.135 | 0.037 | 3.677 | 2.730 × 10−4 | *** |

| Z.swv | 0.115 | 0.039 | 2.929 | 3.622 × 10−3 | ** |

| Z.t_max | −0.419 | 0.055 | −7.629 | 2.170 × 10−13 | *** |

| Null deviance | 370.000 | on 370 degrees of freedom | |||

| Residual deviance | 107.780 | on 357 degrees of freedom | |||

| AIC | 624.240 | ||||

| Parametric Coefficients | Estimate | Std. Error | t Value | Pr(>|t|) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.000 | 0.018 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |

| Z.ua_dis | 0.058 | 0.026 | 2.206 | 2.811 × 10−2 | * |

| Z.p | 0.246 | 0.063 | 3.898 | 1.190 × 10−4 | *** |

| Z.ph_min | −0.388 | 0.071 | −5.492 | 8.250 × 10−8 | *** |

| Approximate significance of smoothed terms | edf | Ref.df | F | p-value | |

| s(Z.slr_2020_45_med_c) | 5.69 | 6.93 | 3.32 | 2.143 × 10−3 | ** |

| s(Z.coast_dis) | 8.13 | 8.77 | 8.38 | 2.000 × 10−16 | *** |

| s(Z.river_dis) | 7.86 | 8.65 | 8.24 | 2.000 × 10−16 | *** |

| s(Z.at_max) | 6.75 | 7.88 | 3.64 | 4.840 × 10−4 | *** |

| s(Z.bat) | 1.75 | 2.17 | 6.64 | 9.990 × 10−4 | *** |

| s(Z.mld) | 6.89 | 7.99 | 10.13 | 2.000 × 10−16 | *** |

| s(Z.s) | 8.08 | 8.74 | 15.19 | 2.000 × 10−16 | *** |

| s(Z.swd) | 6.55 | 7.64 | 4.50 | 5.870 × 10−5 | *** |

| s(Z.swv) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 37.85 | 2.000 × 10−16 | *** |

| s(Z.t_max) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 35.57 | 2.000 × 10−16 | *** |

| adjR2 | 0.878 | ||||

| Deviance explained | 89.70% | ||||

| GCV | 0.14431 | ||||

| Scale est. | 0.12187 | ||||

| n | 371 |

| Diagnostic Information MGWR Model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residual sum of squares | 32.349 | |||

| Effective number of parameters (trace(S)) | 50.704 | |||

| Degree of freedom (n-trace(S)) | 320.296 | |||

| Sigma estimate | 0.318 | |||

| Log-likelihood | −73.878 | |||

| Degree of Dependency (DoD) | 0.770 | |||

| AIC | 251.164 | |||

| AICc | 268.286 | |||

| BIC | 453.647 | |||

| R2 | 0.913 | |||

| adjR2 | 0.899 | |||

| MGWR bandwidths | ||||

| Variable | Bandwidth | ENP_j | Adj t-val (95%) | DoD_j |

| ua_dis | 60.000 | 12.446 | 2.895 | 0.574 |

| coast_dis | 370.000 | 1.141 | 2.023 | 0.978 |

| river_dis | 370.000 | 1.180 | 2.037 | 0.972 |

| t_max | 370.000 | 1.080 | 2.000 | 0.987 |

| swv | 355.000 | 1.290 | 2.074 | 0.957 |

| swd | 367.000 | 1.294 | 2.075 | 0.956 |

| s | 169.000 | 2.164 | 2.281 | 0.870 |

| mld | 57.000 | 10.579 | 2.842 | 0.601 |

| bat | 370.000 | 1.339 | 2.090 | 0.951 |

| at_max | 48.000 | 12.147 | 2.887 | 0.578 |

| ph_min | 370.000 | 1.088 | 2.002 | 0.986 |

| p | 367.000 | 1.053 | 1.989 | 0.991 |

| slr_2020_45_med_c | 120.000 | 3.903 | 2.501 | 0.770 |

| Monte Carlo Test for Spatial Variability | ||||

| Variable | p-value | |||

| ua_dis | 0.000 | *** | ||

| coast_dis | 0.985 | |||

| river_dis | 0.932 | |||

| t_max | 0.923 | |||

| swv | 0.655 | |||

| swd | 0.523 | |||

| s | 0.000 | *** | ||

| mld | 0.000 | *** | ||

| bat | 0.604 | |||

| at_max | 0.000 | *** | ||

| ph_min | 0.103 | |||

| p | 0.003 | ** | ||

| slr_2020_45_med_c | 0.000 | *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Donša, D.; Ivajnšič, D.; Lipej, L.; Trkov, D.; Mavrič, B.; Pitacco, V.; Fortič, A.; Lokovšek, A.; Šiško, M.; Orlando-Bonaca, M. Climate-Driven Habitat Shifts in Brown Algal Forests: Insights from the Adriatic Sea. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2026, 14, 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14020196

Donša D, Ivajnšič D, Lipej L, Trkov D, Mavrič B, Pitacco V, Fortič A, Lokovšek A, Šiško M, Orlando-Bonaca M. Climate-Driven Habitat Shifts in Brown Algal Forests: Insights from the Adriatic Sea. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2026; 14(2):196. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14020196

Chicago/Turabian StyleDonša, Daša, Danijel Ivajnšič, Lovrenc Lipej, Domen Trkov, Borut Mavrič, Valentina Pitacco, Ana Fortič, Ana Lokovšek, Milijan Šiško, and Martina Orlando-Bonaca. 2026. "Climate-Driven Habitat Shifts in Brown Algal Forests: Insights from the Adriatic Sea" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 14, no. 2: 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14020196

APA StyleDonša, D., Ivajnšič, D., Lipej, L., Trkov, D., Mavrič, B., Pitacco, V., Fortič, A., Lokovšek, A., Šiško, M., & Orlando-Bonaca, M. (2026). Climate-Driven Habitat Shifts in Brown Algal Forests: Insights from the Adriatic Sea. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 14(2), 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14020196