Machine Learning-Based Prediction of Maximum Stress in Observation Windows of HOV

Abstract

1. Introduction

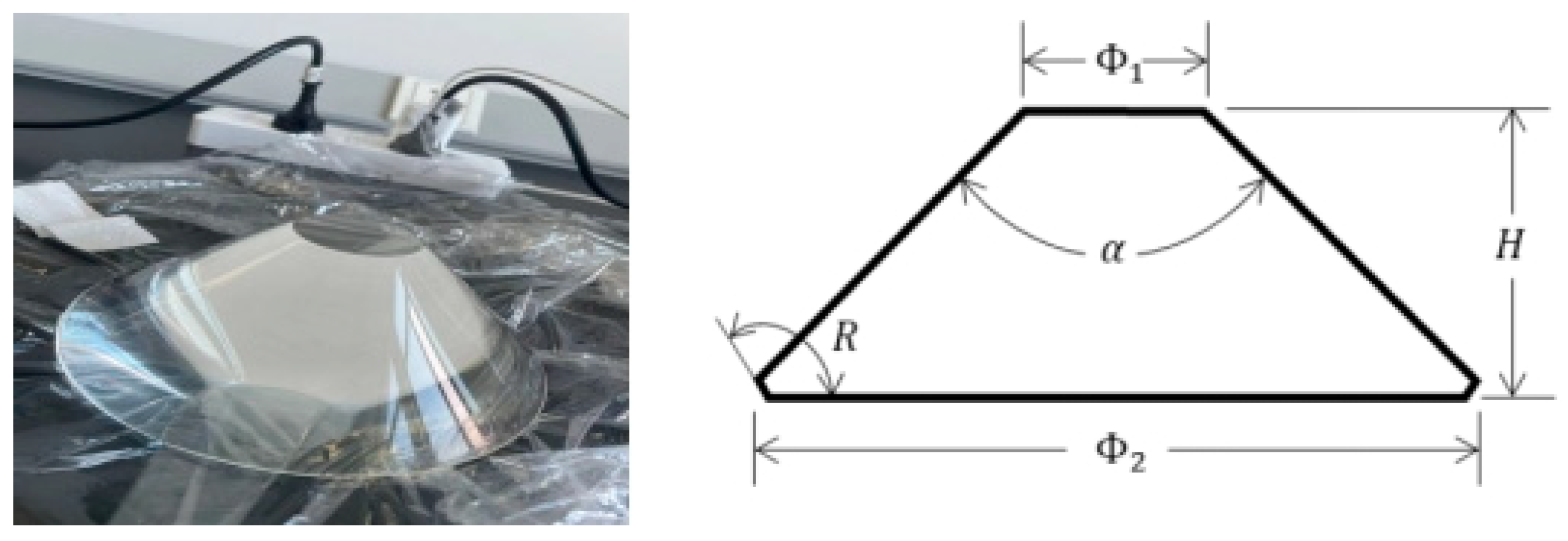

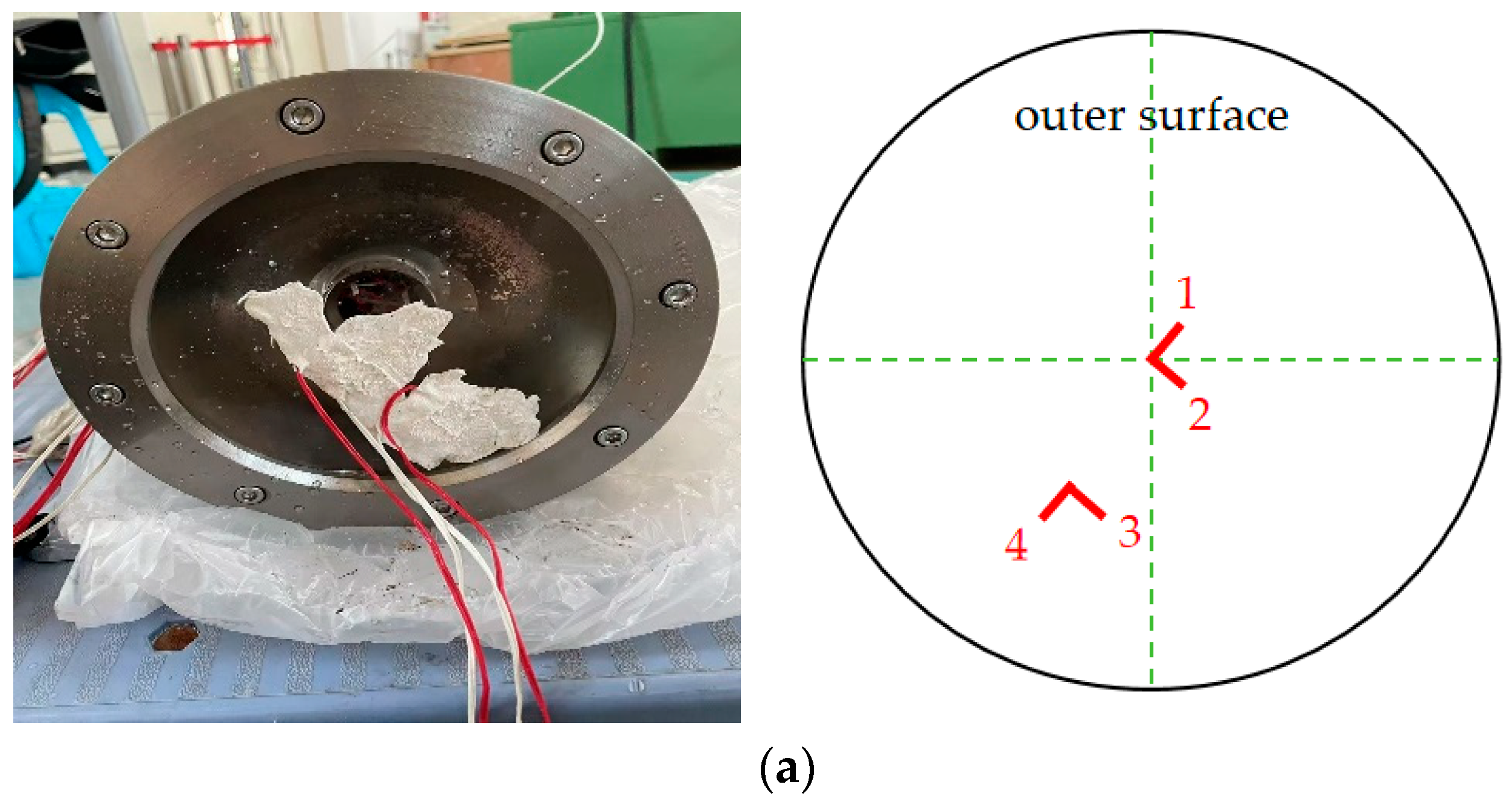

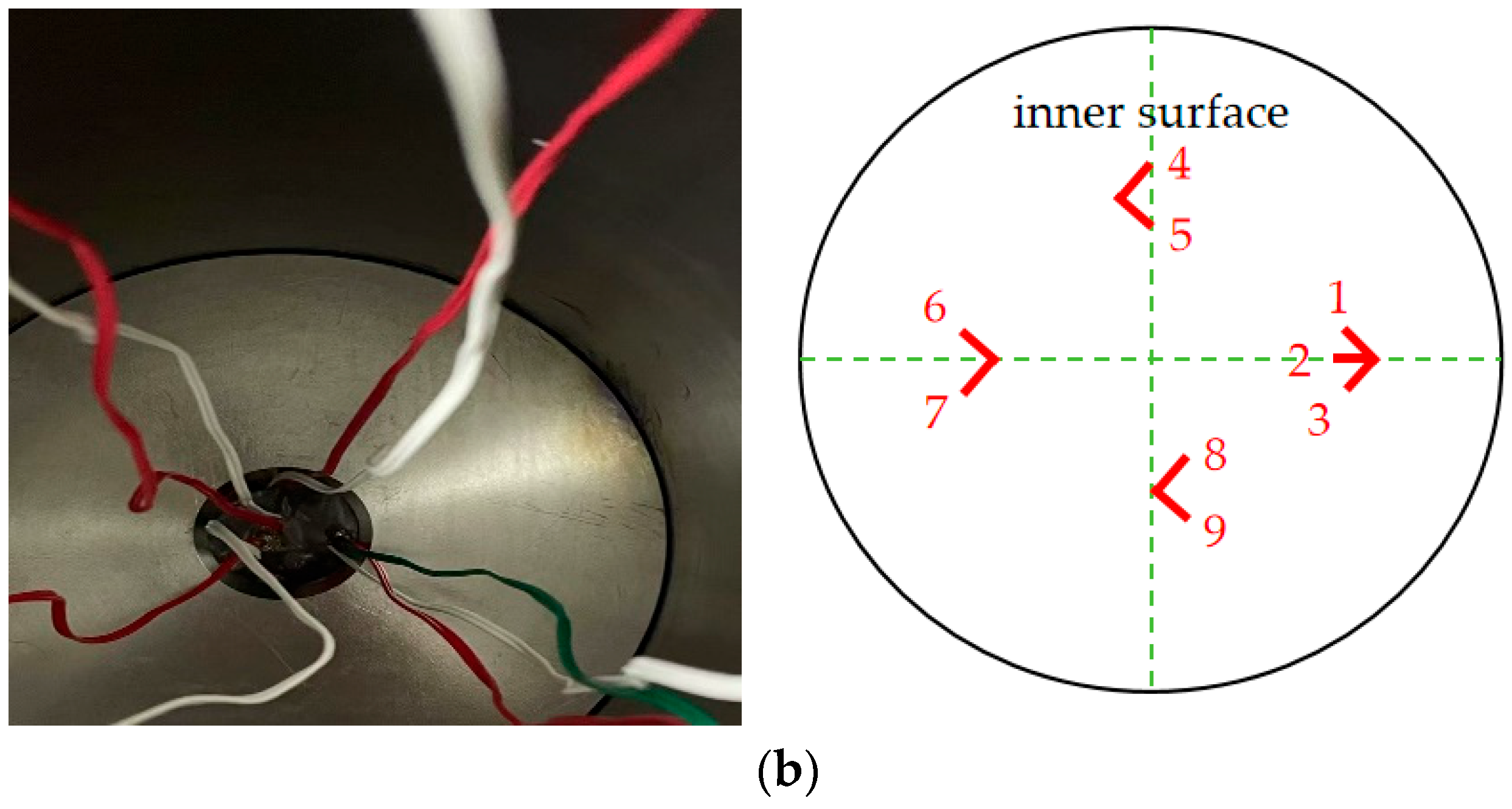

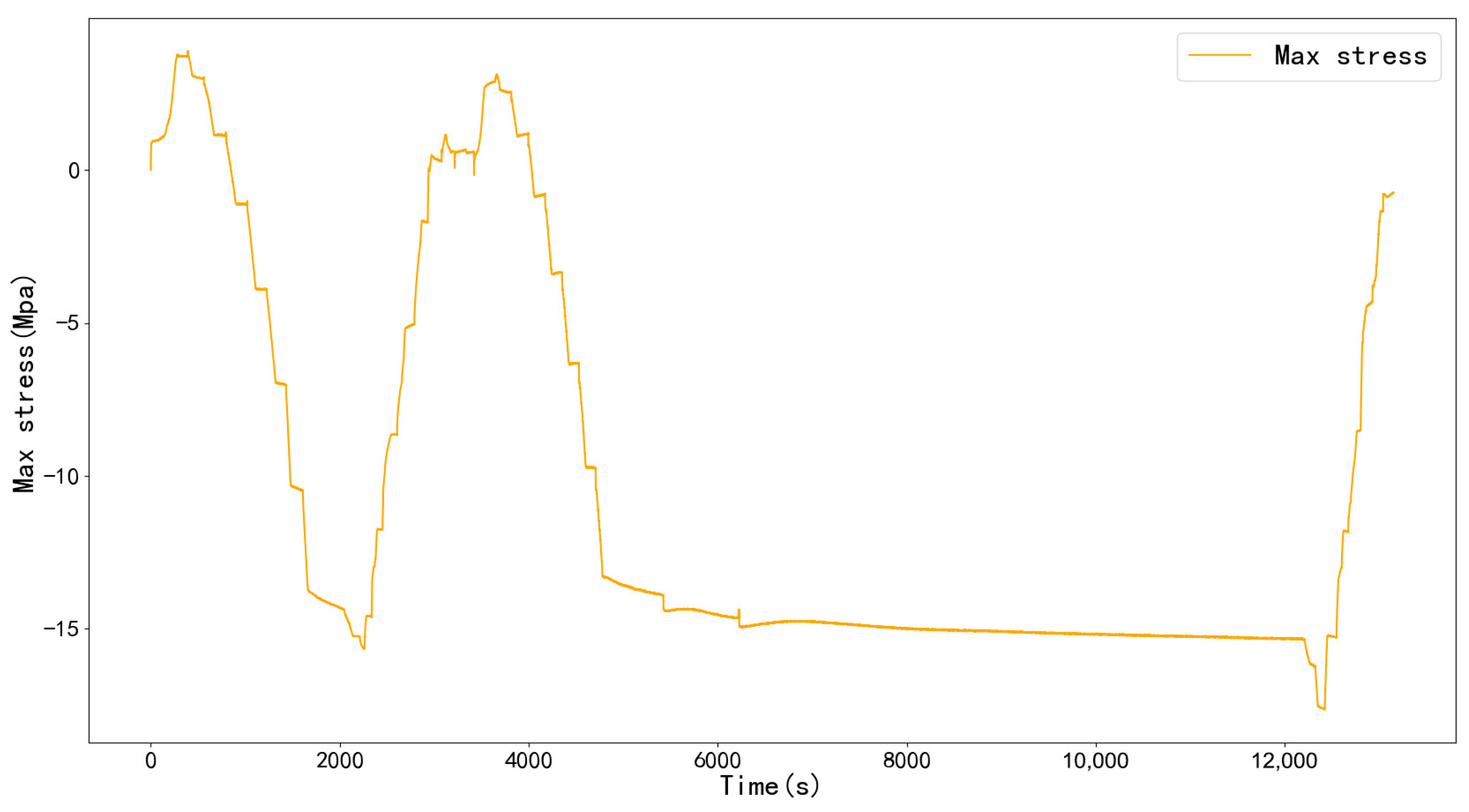

2. Materials and Method

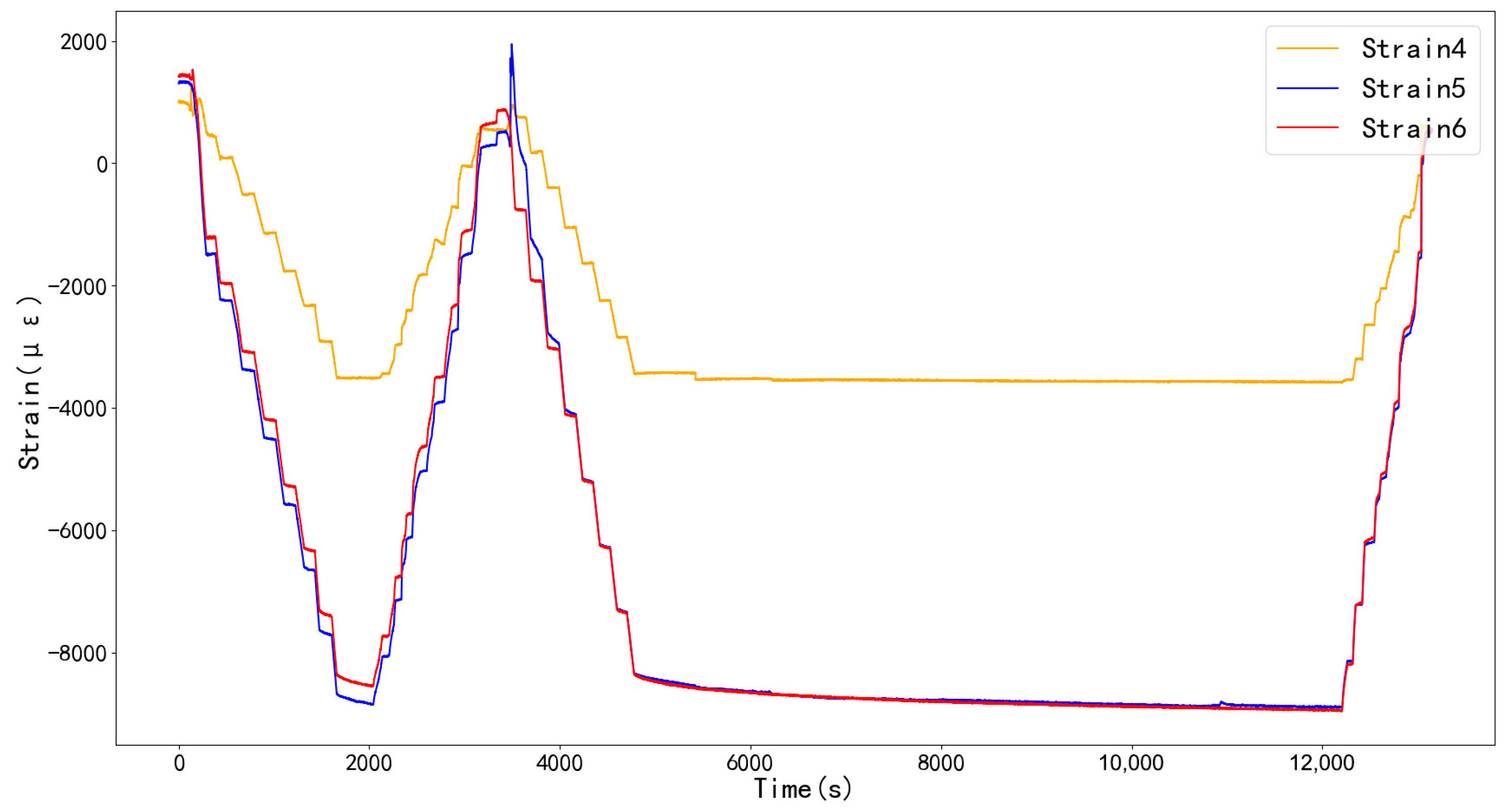

2.1. Data Source

2.2. Machine Learning Algorithms

2.2.1. Gaussian Process Regression

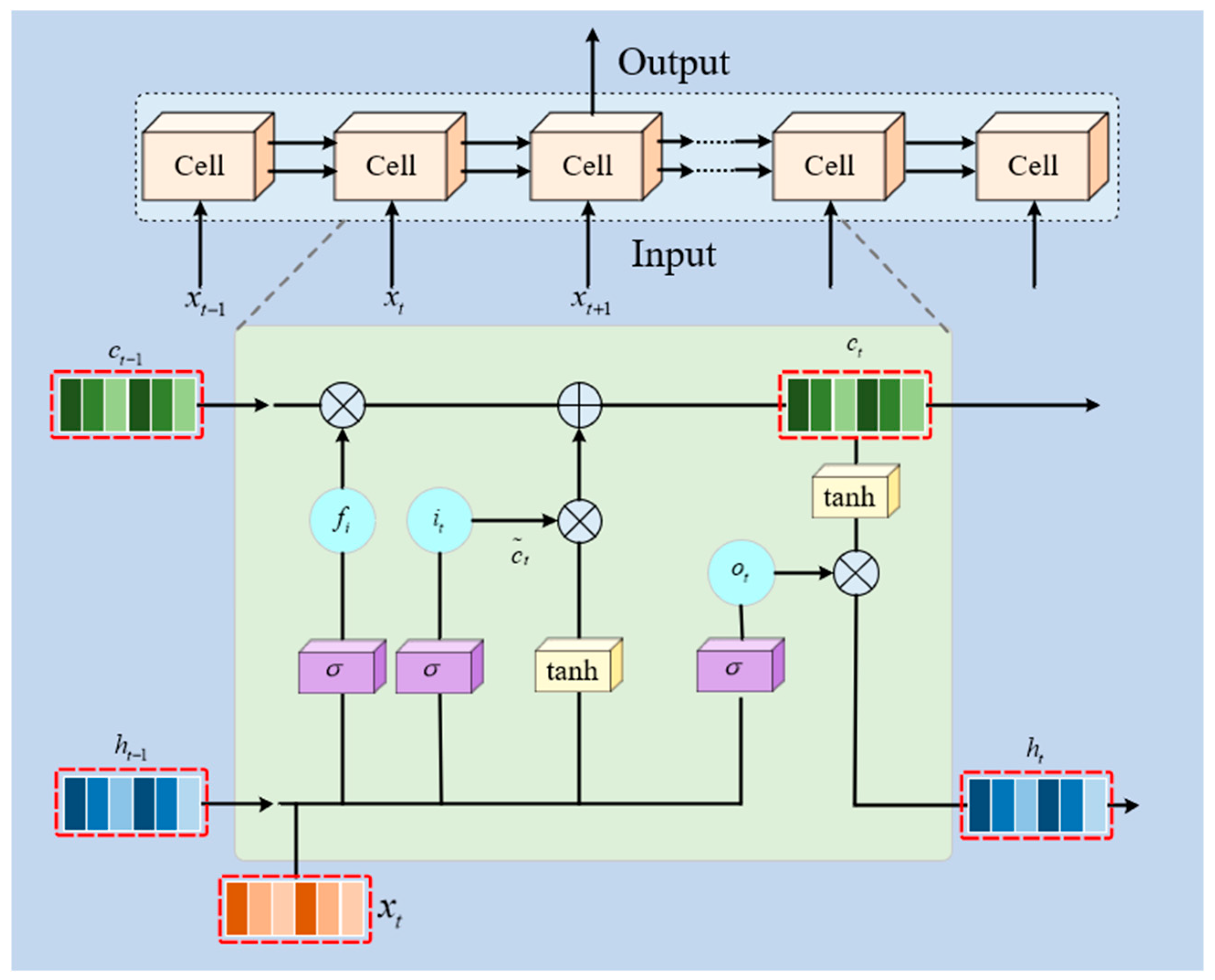

2.2.2. CNN-LSTM

2.2.3. Transformer-CNN-BiLSTM

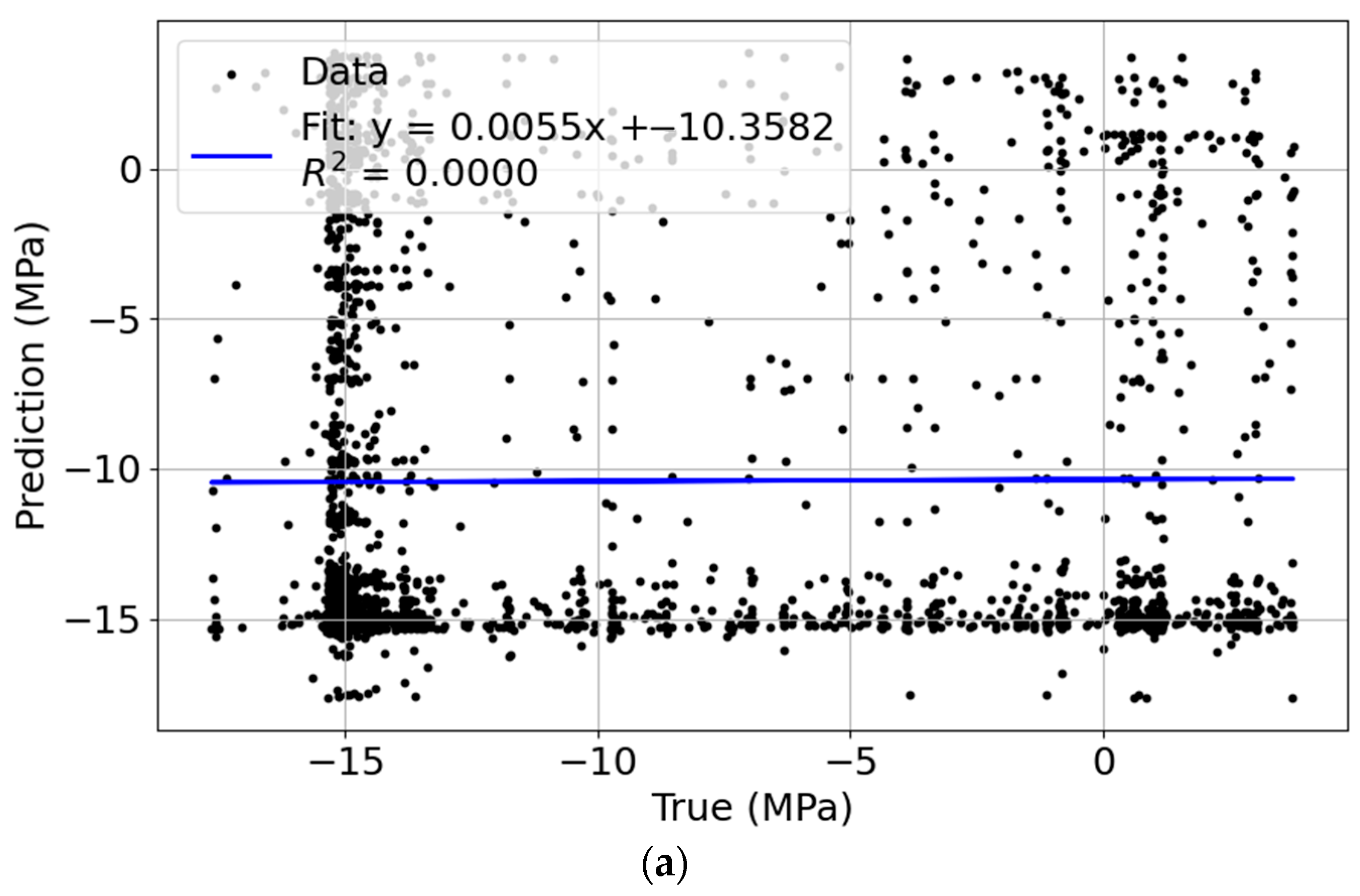

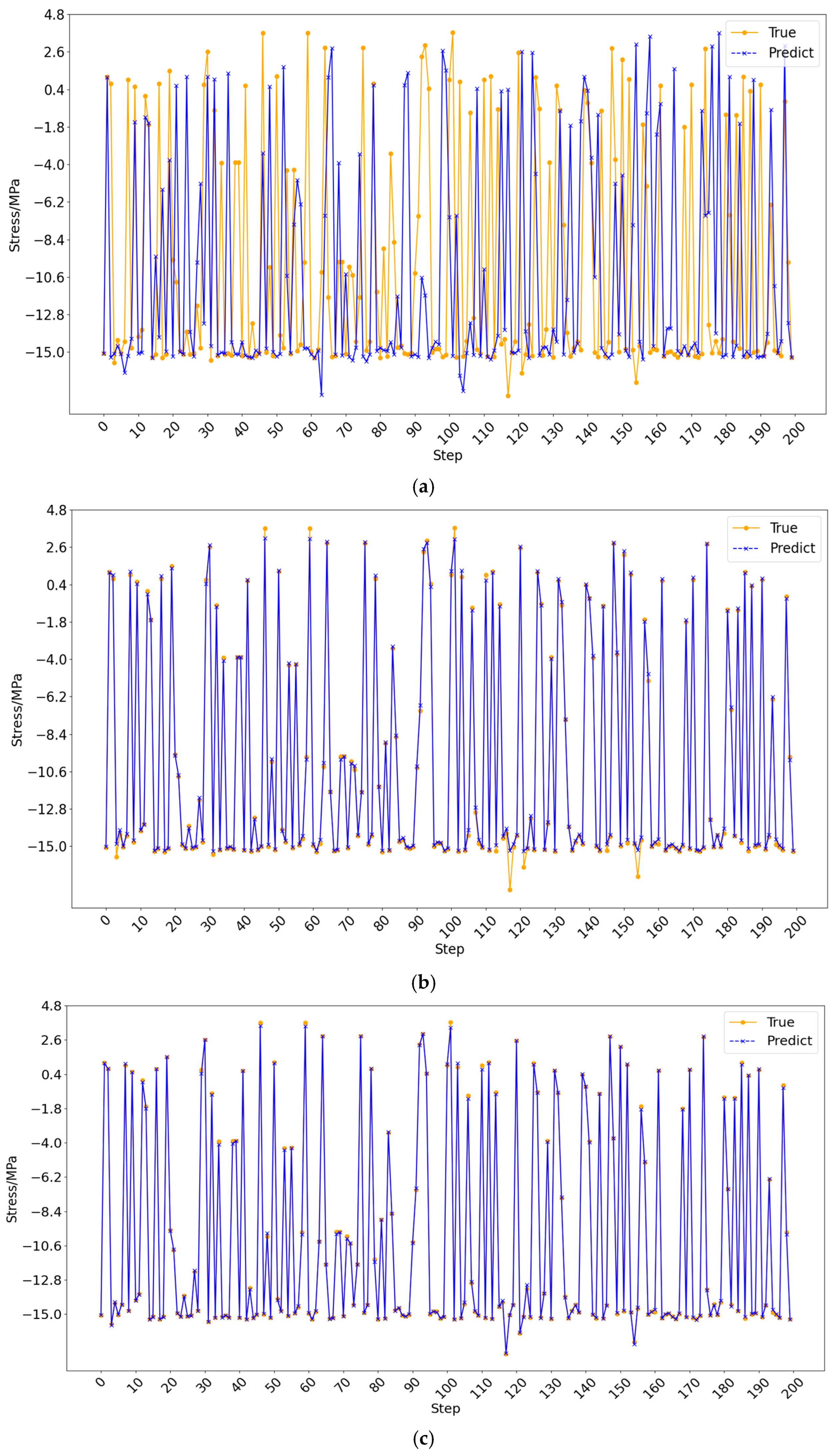

3. Results

4. Comparison of Models

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stachiw, J.D. Handbook of Acrylics for Submersibles, Hyperbaric Chambers, and Aquaria; Best Publishing Company: Flagstaff, AZ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Busby, R.F. Manned Submersibles; Office of the Oceanographer of the Navy: Washington, DC, USA, 1976; pp. 55–63. [Google Scholar]

- Stachiw, J.D. Conical acrylic windows under long-term hydrostatic pressure of 10,000 psi. ASME J. Eng. Ind. 1972, 94, 1053–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASME. PVHO-1-Safety Standard for Pressure Vessels for Human Occupancy; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Du, Q.; Jiang, Z.; Cui, W. Effect of temperature and nonlinearity of PMMA material in the design of observation windows for a full ocean depth manned submersible. Mar. Technol. Soc. J. 2019, 53, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Hou, S.; Qian, X.; Chen, Z.; Zheng, C.; Xu, F. Creep behavior and lifetime prediction of PMMA immersed in liquid scintillator. Polym. Test. 2016, 78, 6–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, J.; White, V. Predictive models for the creep behaviour of PMMA. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 1995, 197, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranesh, S.B.; Kumar, D.; Subramanian, V.A.; Sathianarayanan, D.; Ramadass, G.A. Numerical and experimental study on the safety of viewport window in a deep sea manned submersible. Ships Offshore Struct. 2019, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagaris, I.E.; Likas, A.; Fotiadis, D.I. Artificial neural networks for solving ordinary and partial differential equations. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 1998, 9, 987–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ryck, T.; Jagtap, A.D.; Mishra, S. Error Estimates for Physics Informedneural Networks Approximating the Navier-Stokes Equations. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.09346. [Google Scholar]

- Hoq, E.; Aljarrah, O.; Li, J.; Bi, J.; Heryudono, A.; Huang, W. Data-driven methods for stress field predictions in random heterogeneous materials. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 123, 106267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swischuk, R.; Mainini, L.; Peherstorfer, B.; Willcox, K. Projection-based model reduction: Formulations for physics-based machine learning. Comput. Fluids 2019, 179, 704–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinesta, F.; Huerta, A.; Rozza, G.; Willcox, K. Model reduction methods. In Encyclopedia of Computational Mechanics Second Edition; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Tripathy, S.; Kannala, J.; Rahtu, E. Learning image-to-image translation using paired and unpaired training samples. In Computer Vision—ACCV 2018; Jawahar, C.V., Li, H., Mori, G., Schindler, K., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W. Deep learning mesh generation techniques. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Applied Computational Electromagnetics Society (ACES-China) Symposium, Chengdu, China, 28–31 July 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Leger, A.; Le Goic, G.; Fauvet, É.; Fofi, D.; Kornalewski, R. R-CNN based automated visual inspection system for engine parts quality assessment. In Proceedings of the Fifteenth International Conference on Quality Control by Artificial Vision, Tokushima, Japan, 12–14 May 2021; Ko-Muro, T., Shimizu, T., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2021; p. 1179412. [Google Scholar]

- Bagave, P.; Linssen, J.; Teeuw, W.; Brinke, J.K.; Meratnia, N. Channel state information (CSI) analysis for predictive maintenance using convolutional neural network (CNN). In Proceedings of the 2nd Workshop on Data Acquisition to Analysis, New York, NY, USA, 10 November 2019; Academy of Medicine: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; You, D. Data-driven prediction of unsteady flow over a circular cylinder using deep learning. J. Fluid Mech. 2019, 879, 217–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Deng, X. Image-based reconstruction for a 3D-PFHS heat transfer problem by ReConNN. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2019, 134, 656–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abueidda, D.W.; Koric, S.; Al-Rub, R.A.; Parrott, C.M.; James, K.A.; Sobh, N.A. A deep learning energy method for hyperelasticity and viscoelasticity. Eur. J. Mech. A Solids 2022, 95, 104639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donegan, S.P.; Kumar, N.; Groeber, M.A. Associating local microstructure with predicted thermally-induced stress hotspots using convolutional neural networks. Mater. Charact. 2019, 158, 109960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Liu, Y.; Sun, H. Physics-guided convolutional neural network (PhyCNN) for data-driven seismic response modeling. Eng. Struct. 2020, 215, 110704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Z.; Jiang, H.; Kara, L.B. Stress field prediction in cantilevered structures using convolutional neural networks. J. Comput. Inf. Sci. Eng. 2020, 20, 011002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herriott, C.; Spear, A.D. Predicting microstructure-dependent mechanical prop-erties in additively manufactured metals with machine- and deep-learning methods. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2020, 175, 109599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative adversarial networks. Commun. ACM 2014, 63, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-T.; Gu, G.X. Generative deep neural networks for inverse materials design using backpropagation and active learning. Adv. Sci. 2020, 7, 1902607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, B.; Gao, H. A deep learning approach to the inverse problem of modulus identification in elasticity. MRS Bull. 2021, 46, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Nie, Z.; Yeo, R.; Farimani, A.B.; Kara, L.B. Stressgan: A generative deep learning model for two-dimensional stress distribution prediction. J. Appl. Mech. 2021, 88, 051005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, A.; Jaitly, N.; Mohamed, A.R. Hybrid speech recognition with deep bidirectional LSTM. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Workshop on Automatic Speech Recognition and Understanding, Olomouc, Czech Republic, 8–12 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, C.K.; Rasmussen, C.E. Gaussian Processes for Machine Learning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Masood, A.; Ahmad, K. A review on emerging artificial intelligence (AI) techniques for air pollution forecasting: Fundamentals, application and performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 322, 129072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wu, M.; Tang, R.; Chen, S.; Chen, S. A hybrid deep learning model based on LSTM for long-term PM2.5 prediction. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Intelligent Science and Technology, Tokyo Japan, 25–27 September 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30. Epub ahead of printing. [Google Scholar]

| Technical Specifications | Numerical Values |

|---|---|

| Density (g/cm3) | 1.186 |

| Tensile modulus/GPa | 3.13 |

| Yield strength/MPa | 129 |

| Poisson’s ratio | 0.37 |

| Refractive index | 1.49 |

| Elasticity modulus/MPa | 3540 |

| MSE | MAE | RSR | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transformer-CNN-BiLSTM | 0.0183 | 0.0954 | 0.1353 |

| CNN-LSTM | 0.0591 | 0.1274 | 0.2432 |

| GP | 1.17701 | 1.22083 | 1.0849 |

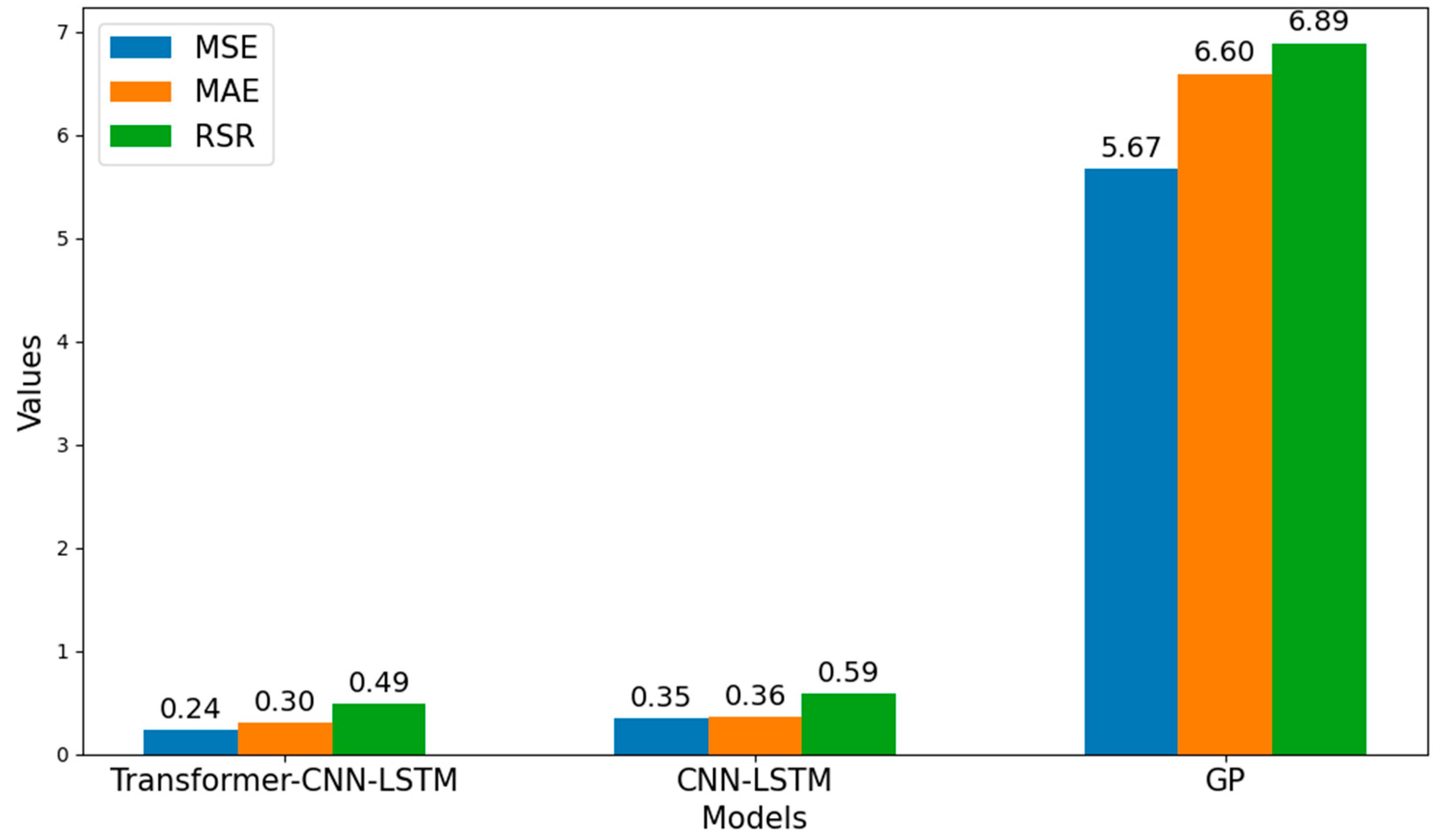

| MSE | MAE | RSR | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transformer-CNN-BiLSTM | 0.2398 | 0.3001 | 0.4897 |

| CNN-LSTM | 0.34806 | 0.3616 | 0.5899 |

| GP | 5.674 | 6.5968 | 6.892 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, D.; Wang, Z.; Ding, Z.; An, X. Machine Learning-Based Prediction of Maximum Stress in Observation Windows of HOV. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2026, 14, 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14020151

Li D, Wang Z, Ding Z, An X. Machine Learning-Based Prediction of Maximum Stress in Observation Windows of HOV. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2026; 14(2):151. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14020151

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Dewei, Zhijie Wang, Zhongjun Ding, and Xi An. 2026. "Machine Learning-Based Prediction of Maximum Stress in Observation Windows of HOV" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 14, no. 2: 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14020151

APA StyleLi, D., Wang, Z., Ding, Z., & An, X. (2026). Machine Learning-Based Prediction of Maximum Stress in Observation Windows of HOV. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 14(2), 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14020151