A Coastal Zone Imager-Based Model for Assessing the Distribution of Large Green Algae in the Northern Coastal Waters of China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

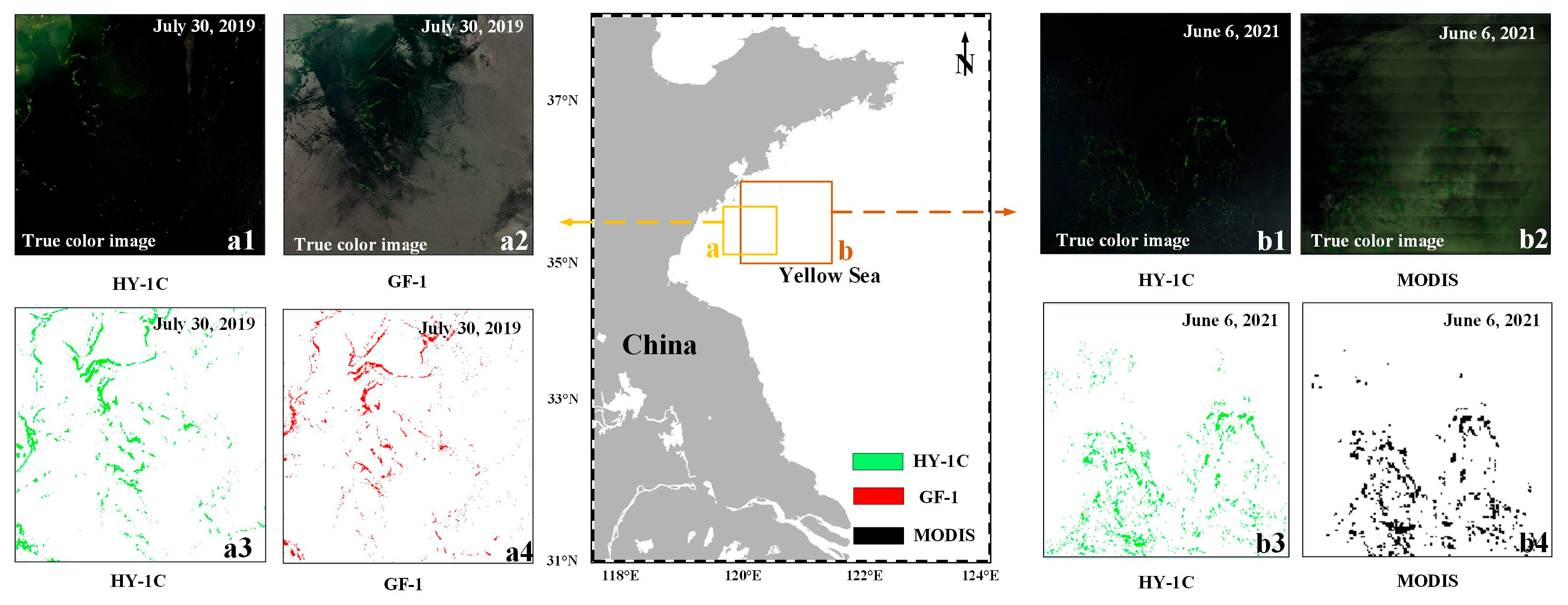

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Satellite Data

2.3. Measured Spectra of Large Green Algae

2.4. Reanalysis Data

2.5. In Situ Data

2.6. Data Preprocessing

3. Results

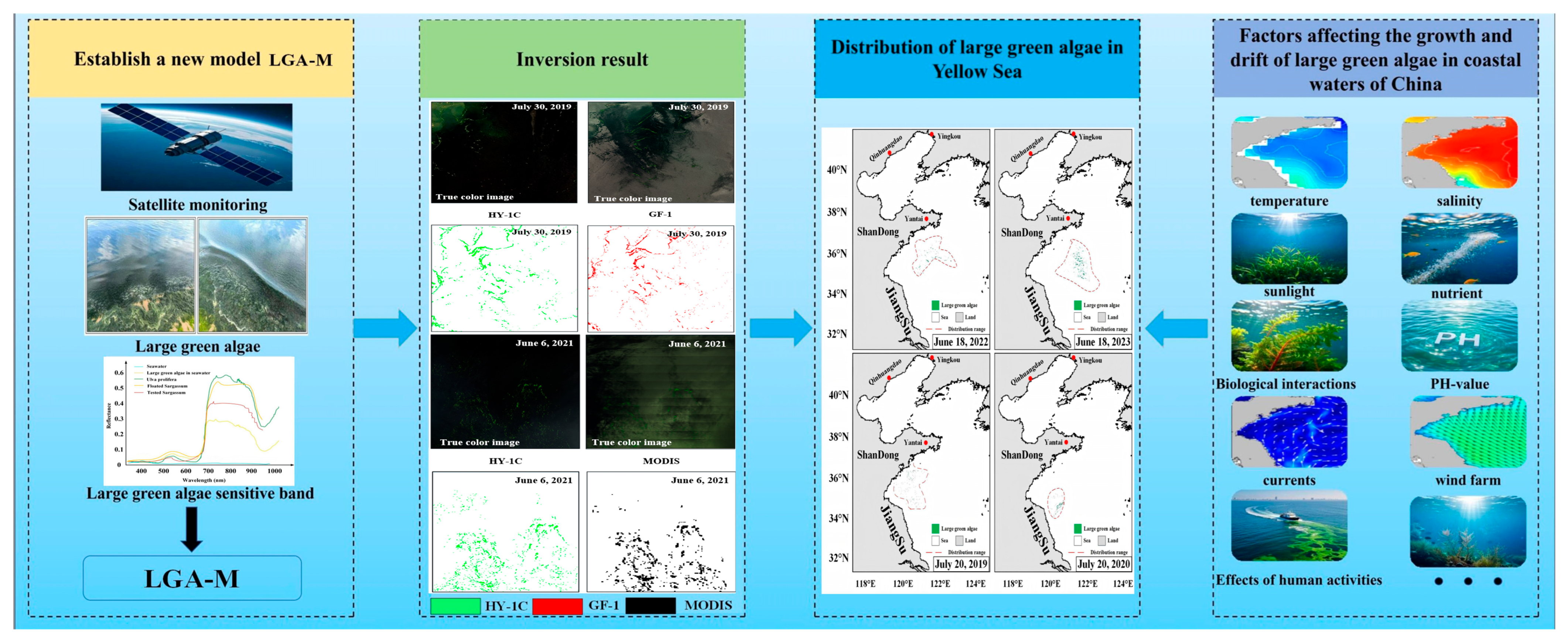

3.1. Establishment of the Inverse Model of LGA

3.1.1. Spectral Characteristics Analysis of Large Green Algae

3.1.2. Model Building

3.1.3. Verification

3.2. Distribution Characteristics of LGA in the Yellow and Bohai Seas

4. Discussion

4.1. Applicability of the LGA Inversion Model

4.2. Factors Influencing the Distribution of LGA in Coastal Waters of China

4.2.1. Factors Affecting the Growth of LGA in Coastal Waters of China

4.2.2. Factors Affecting the Drift of LGA in Coastal Waters of China

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CZI | Coastal Zone Imager |

| EVI | Enhanced Vegetation Index |

| FAI | Floating Algae Index |

| GF-WFV | Gaofen Wide Field View Camera |

| IGAG | Index of floating Green Algae for GOCI |

| LGA | Large Green Algae |

| LGA-M | Large Green Algae Inversion Model |

| MODIS | Moderate-resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer |

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

References

- Xiao, J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, D.; Fu, M.; Yuan, C.; Yan, T. Harmful macroalgal blooms (HMBs) in China’s coastal water: Green and golden tides. Harmful Algae 2021, 107, 102061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, L. Macroalgae. Encyclopedia 2021, 1, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Fan, B.; Yu, D.; Fan, Y.; An, D.; Pan, S. Monitoring the Spatio-Temporal Distribution of Ulva prolifera in the Yellow Sea (2020–2022) Based on Satellite Remote Sensing. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teichberg, M.; Fox, S.E.; Olsen, Y.S.; Valiela, I.; Martinetto, P.; Iribarne, O.; Muto, E.Y.; Petti, M.A.V.; Corbisier, T.N.; Soto-JimÉNez, M.; et al. Eutrophication and macroalgal blooms in temperate and tropical coastal waters: Nutrient enrichment experiments with Ulva spp. Glob. Change Biol. 2010, 16, 2624–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Kong, F.; Li, Y.; Zhao, J.; Yu, R.; Zhou, M.; Jiang, P.; Yan, T. A Massive Green Tide in the Yellow Sea in 2021: Field Investigation and Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, S.J.; Liu, F.; Shan, T.F.; Xu, N.; Zhang, Z.H.; Gao, S.Q.; Chopin, T.; Sun, S. Tracking the algal origin of the Ulva bloom in the Yellow Sea by a combination of molecular, morphological and physiological analyses. Mar. Environ. Res. 2010, 69, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, M.; Darnhofer, I.; Darrot, C.; Beuret, J.-E. Green tides in Brittany: What can we learn about niche–regime interactions? Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2013, 8, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlier, R.H.; Morand, P.; Finkl, C.W.; Thys, A. Green tides on the Brittany coasts. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE US/EU Baltic International Symposium, Klaipeda, Lithuania, 23–26 May 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Gao, Z.; Ning, J.; Zheng, X.; Liu, C.; Gao, W. Error analysis on Green Tide monitoring using MODIS data in the Yellow Sea based on GF-1 WFV data. In Proceedings of the SPIE Optical Engineering + Applications, San Diego, CA, USA, 19 September 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Chen, X.; Yi, Q.; Wang, G.; Pan, G.; Lin, A.; Peng, G. A Strategy for the Proliferation of Ulva prolifera, Main Causative Species of Green Tides, with Formation of Sporangia by Fragmentation. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e8571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Gao, Z.; Song, D. Analysis of environmental factors affecting the large-scale long-term sequence of green tide outbreaks in the Yellow Sea. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2021, 260, 107504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Feng, X.; Gao, G. Variation of suspended-sediment caused by tidal asymmetry and wave effects. Ocean Model. 2024, 192, 102454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, D. Vertical average irradiance shapes the spatial pattern of winter chlorophyll-a in the Yellow Sea. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2019, 224, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, D.; Yu, D.; Zheng, X.; Zhou, Y.; Meng, L.; Xing, Q. Monitoring the Dissipation of the Floating Green Macroalgae Blooms in the Yellow Sea (2007–2020) on the Basis of Satellite Remote Sensing. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yuan, Y.; Xu, Y.; Shen, X.; Sun, D.; Qiu, Z.; Wang, S.; He, Y. Remote sensing method for detecting green tide using HJ-CCD top-of-atmosphere reflectance. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2021, 102, 102371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Wu, M.; Xing, Q.; Song, X.; Zhao, D.; Han, Q.; Zhang, G. Spatio-temporal patterns of Ulva prolifera blooms and the corresponding influence on chlorophyll-a concentration in the Southern Yellow Sea, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 640–641, 807–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Yu, T.; Xu, J.; Pan, X.; Shao, W.; Zuo, J.; Yu, Y. Monitoring and Forecasting Green Tide in the Yellow Sea Using Satellite Imagery. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, T.W.; Liang, X.J.; Gong, J.L.; Tong, C.; Xiao, Y.F.; Liu, R.J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J. Assessing and refining the satellite-derived massive green macro-algal coverage in the Yellow Sea with high resolution images. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2018, 144, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, T.W.; Zhang, J.; Sun, L.E.; Jia, Y.J.; Zhao, W.; Wang, Z.L.; Meng, J.M. Satellite monitoring of massive green macroalgae bloom (GMB): Imaging ability comparison of multi-source data and drifting velocity estimation. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2012, 33, 5513–5527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yang, R.; Tian, Q.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, Y.; Mi, X. Comparative Analysis of GF-1 WFV, ZY-3 MUX, and HJ-1 CCD Sensor Data for Grassland Monitoring Applications. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 2089–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Dall’Olmo, G.; Moses, W.; Rundquist, D.C.; Barrow, T.; Fisher, T.R.; Gurlin, D.; Holz, J. A simple semi-analytical model for remote estimation of chlorophyll-a in turbid waters: Validation. Remote Sens. Environ. 2008, 112, 3582–3593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Wang, F.; Zhou, Y.; Ye, Z. In-orbit geometric calibration of HaiYang-1C coastal zone imager with multiple fields. Opt. Express 2021, 29, 18950–18965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Tian, L.; Li, J.; Tong, R.; Guo, Y.; Zeng, Q. Spatial–Spectral Fusion of HY-1C COCTS/CZI Data for Coastal Water Remote Sensing Using Deep Belief Network. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2020, 14, 1693–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jilin, M.; Jianqiang, L.; Guangping, X.; Tong, Y.; Ruqing, T.; Liqiao, T.; Kohei, A.; Linyu, W. Atmospheric correction for HY-1C CZI images using neural network in western Pacific region. Geo Spat. Inf. Sci. 2022, 25, 476–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Li, R.; Shen, F.; Liu, J. HY-1C/D CZI Image Atmospheric Correction and Quantifying Suspended Particulate Matter. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yu, F. The characteristic analysis on sea surface temperature inter-annual variation in the Bohai Sea, Yellow Sea and East China Sea. Mar. Sci. 2009, 33, 8. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/285329735_The_characteristic_analysis_on_sea_surface_temperature_inter-annual_variation_in_the_Bohai_Sea_Yellow_Sea_and_East_China_Sea (accessed on 25 May 2024).

- Qingjun, F.; Xiao, Y.; Qingchao, H.; Lei, L.; Yujie, Z. Variability of the Primary Productivity in the Yellow and Bohai Seas from 2003 to 2020 Based on the Estimate of Satellite Remote Sensing. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuomin, L.; Lei, G.; Rui, C. Sea surface skin temperature retrieval from HY-1D COCTS observations. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1205776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Satellite Ocean Application Service. Available online: http://www.nsoas.org.cn/ (accessed on 17 October 2023).

- China Resources Satellite Application Center. Available online: https://www.cresda.cn/zgzywxyyzx/index_pc.html (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Zhao, M.; Si, F.; Zhou, H.; Jiang, Y.; Ji, C.; Wang, S.; Zhan, K.; Liu, W. Pre-Launch Radiometric Characterization of EMI-2 on the GaoFen-5 Series of Satellites. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NASA’s DAAC Data Center. Available online: https://ladsweb.modaps.eosdis.nasa.gov/ (accessed on 20 October 2023).

- Tesema Kebede, S.; Tekalegn Ayele, W.; Taye, A.; Tenalem, A. Spatio-Temporal Change of Land Use/Land Cover and Vegetation Using Multi-MODIS Satellite Data, Western Ethiopia. Sci. World J. 2023, 2023, 7454137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douay, F.; Verpoorter, C.; Duong, G.; Spilmont, N.; Gevaert, F. New Hyperspectral Procedure to Discriminate Intertidal Macroalgae. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutser, T.; Metsamaa, L.; Strömbeck, N.; Vahtmäe, E. Monitoring cyanobacterial blooms by satellite remote sensing. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2006, 67, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierssen, H.M.; Chlus, A.; Russell, B. Hyperspectral discrimination of floating mats of seagrass wrack and the macroalgae Sargassum in coastal waters of Greater Florida Bay using airborne remote sensing. Remote Sens. Environ. 2015, 167, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, M.L.; Trainer, V.L.; Smayda, T.J.; Karlson, B.S.O.; Trick, C.G.; Kudela, R.M.; Ishikawa, A.; Bernard, S.; Wulff, A.; Anderson, D.M.; et al. Harmful algal blooms and climate change: Learning from the past and present to forecast the future. Harmful Algae 2015, 49, 68–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, J.L.; Server, N.T.R. Ocean Optics Protocols for Satellite Ocean Color Sensor Validation. Br. J. Surg. 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joaquín, M.-S.; Emanuel, D.; Anna, A.-P.; Clément, A.; Gabriele, A.; Gianpaolo, B.; Souhail, B.; Margarita, C.; Shaun, H.; Hans, H.; et al. ERA5-Land: A state-of-the-art global reanalysis dataset for land applications. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 4349–4383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copernicus Climate Data Store. Available online: https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.f17050d7 (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- Global Ocean Physics Analysis and Forecast dataset. Available online: https://doi.org/10.48670/moi-00016 (accessed on 28 November 2023).

- General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans. Available online: https://www.gebco.net (accessed on 10 November 2023).

- Hu, C.; Feng, L.; Hardy, R.F.; Hochberg, E.J. Spectral and spatial requirements of remote measurements of pelagic Sargassum macroalgae. Remote Sens. Environ. 2015, 167, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C. A novel ocean color index to detect floating algae in the global oceans. Remote Sens. Environ. 2009, 113, 2118–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, L.; Zhang, G. Object-oriented remote sensing imagery classification accuracy assessment based on confusion matrix. In Proceedings of the 2012 20th International Conference on Geoinformatics, Hong Kong, China, 15–17 June 2012; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Cao, C.H.; Cheng, L.X.; Wang, N.; Wen, L.J. Monitoring of Enteromorpha prolifera in the yellow sea with MODIS image based on linear mixing model and NDVI threshold. Chin. J. Ecol. 2018, 37, 3480–3486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Glamore, W.; Tamburic, B.; Morrow, A.; Johnson, F. Remote sensing to detect harmful algal blooms in inland waterbodies. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 851, 158096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabezudo, M.M.; Tavares, M.H.; They, N.H.; da Motta Marques, D. Assessment of spectral indices and water color combinations for detecting algal blooms in coastal subtropical shallow lakes. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2025, 39, 101678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.; Cao, X.; Li, S.; Cao, J.; Tong, Y.; Sun, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhao, S.; Cui, Q.; Zeng, Y.; et al. Distribution of Ulva prolifera, the dominant species in green tides along the Jiangsu Province coast in the Southern Yellow Sea, China. J. Sea Res. 2023, 196, 102436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Liu, J.; Zhao, S.; Tong, Y.; Li, S.; Xia, Z.; Hu, M.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, J.; He, P. Advances in the research on micropropagules and their role in green tide outbreaks in the Southern Yellow Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 188, 114710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.S.; Wang, D.; Xu, X.-T.; Xu, N.-J.; Li, Y.-H. Combined Effects of Salinity and Temperature on the Growth and Photophysiological Performances Inulva prolifera. Shuisheng Shengwu Xuebao 2016, 40, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, T.; Ding, J.; Jia, F.; Mu, B.; Liu, R.; Xu, P.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J. Out-of-Band Response for the Coastal Zone Imager (CZI) Onboard China’s Ocean Color Satellite HY-1C: Effect on the Observation Just above the Sea Surface. Sensors 2018, 18, 3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Z.; Hu, Y.; Shum, C.K.; Ma, C.; Song, Q.; Yuan, X.; Wang, B.; Zhou, B. Spatiotemporal Evolutions of the Suspended Particulate Matter in the Yellow River Estuary, Bohai Sea and Characterized by Gaofen Imagery. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaeps, E.; Ruddick, K.G.; Doxaran, D.; Dogliotti, A.I.; Nechad, B.; Raymaekers, D.; Sterckx, S. A SWIR based algorithm to retrieve total suspended matter in extremely turbid waters. Remote Sens. Environ. 2015, 168, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, G.; Li, J.; Chen, J.; Gao, Z.; Fang, L.; Ren, S.; Wang, Q. Remote sensing identification and model-based prediction of harmful algal blooms in inland waters: Current insights and future perspectives. Water Res. X 2025, 28, 100369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon-Ho, L.; So-Hyun, L. Monitoring of Floating Green Algae Using Ocean Color Satellite Remote Sensing. J. Korean Assoc. Geogr. Inf. Stud. 2012, 15, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruihua, D.; Pinfei, W.; Peili, J.; Yi, Z.; Xincheng, C.; Yifei, W. A review on factors affecting microcystins production by algae in aquatic environments. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 15, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Fang, Z.; Liang, J.; Song, X. Estimating Ulva prolifera green tides of the Yellow Sea through ConvLSTM data fusion. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 324, 121350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zheng, M.; Lin, J.; Zhou, S.; Sun, T.; Xu, N. Darkness and low nighttime temperature modulate the growth and photosynthetic performance of Ulva prolifera under lower salinity. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 146, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, M.; Xing, Q.; Park, J.-S.; He, P.; Zhang, J.; Yarish, C.; Kim, J.K. Temperature and high nutrients enhance hypo-salinity tolerance of the bloom forming green alga, Ulva prolifera. Harmful Algae 2023, 123, 102402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.; Qiu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Su, Y.; Li, Y.; Cui, Y.; Qu, S.; Wang, P.; Rong, X. Long-Term Spatiotemporal Characteristics of Ulva prolifera Green Tide and Effects of Environmental Drivers on Its Monitoring by Satellites: A Case Study in the Yellow Sea, China, from 2008 to 2023. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xiao, J.; Yuan, C.; Miao, X.; Fan, S.; Fu, M.; Xia, T.; Zhang, X. The drifting and spreading mechanism of floating Ulva mass in the waterways of Subei shoal, the Yellow Sea of China—Application for abating the world’s largest green tides. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 190, 114789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanzhuo, M.; Yingying, L.; Yufei, M.; Ka Po, W.; Jin Yeu, T.; Yuanzhi, Z. Remote Sensing Monitoring of Green Tide Disaster Using MODIS and GF-1 Data: A Case Study in the Yellow Sea. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bercel, T.L.; Kranz, S.A. Effects of spectral light quality on the growth, productivity, and elemental ratios in differently pigmented marine phytoplankton species. J. Appl. Phycol. 2021, 34, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jianjun, C.; Jianheng, Z.; Yuanzi, H.; Lingjie, Z.; Qing, W.; Liping, C.; Kefeng, Y.; Peimin, H. Adaptability of free-floating green tide algae in the Yellow Sea to variable temperature and light intensity. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junfei, G.; Zhenxiang, Z.; Zhikang, L.; Ying, C.; Zhiqin, W.; Hao, Z.; Jianchang, Y. Photosynthetic Properties and Potentials for Improvement of Photosynthesis in Pale Green Leaf Rice under High Light Conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacometti, G.M.; Morosinotto, T. Photosynthesis|Photoinhibition and Photoprotection in Plants, Algae and Cyanobacteria. In Encyclopedia of Biological Chemistry, 3rd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankita, J.; Ruben, C.; Ganti, M. Effects of Environmental Factors and Nutrient Availability on the Biochemical Composition of Algae for Biofuels Production: A Review. Energies 2013, 6, 4607–4638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junjie, W.; Zhigang, Y.; Qinsheng, W.; Fuxia, Y.; Mingfan, D.; Dandan, L.; Zhimei, G.; Qingzhen, Y. Intra- and inter-seasonal variations in the hydrological characteristics and nutrient conditions in the southwestern Yellow Sea during spring to summer. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 156, 111139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ergang, L.; Shouye, Y.; Hui, W.; Chengfan, Y.; Chao, L.; James, T.L. Kuroshio subsurface water feeds the wintertime Taiwan Warm Current on the inner East China Sea shelf. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2016, 121, 4790–4803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong-Mei, L.; Chuan-Song, Z.; Xiu-Rong, H.; Xiao-Yong, S. Changes in concentrations of oxygen, dissolved nitrogen, phosphate, and silicate in the southern Yellow Sea, 1980–2012: Sources and seaward gradients. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2015, 163, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankaj Kumar, T.; Sudip, S.; Jocirei, D.F.; Arvind Kumar, M. A Mathematical Model for the Effects of Nitrogen and Phosphorus on Algal Blooms. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 2019, 29, 1950129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Qin, B.; Paerl, H.W.; Brookes, J.D.; Wu, P.; Zhou, J.; Deng, J.; Guo, J.; Li, Z. Green algal over cyanobacterial dominance promoted with nitrogen and phosphorus additions in a mesocosm study at Lake Taihu, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 5041–5049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Shaojun, P.; Thierry, C.; Suqin, G.; Tifeng, S.; Xiaobo, Z.; Jing, L. Understanding the recurrent large-scale green tide in the Yellow Sea: Temporal and spatial correlations between multiple geographical, aquacultural and biological factors. Mar. Environ. Res. 2013, 83, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menéndez, M.; Martínez, M.; Comín, F.A. A comparative study of the effect of pH and inorganic carbon resources on the photosynthesis of three floating macroalgae species of a Mediterranean coastal lagoon. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2001, 256, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blinks, L.R. The effect of pH upon the photosynthesis of littoral marine algae. Protoplasma 1963, 57, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhangyi, X.; Jinlin, L.; Shuang, Z.; Qianwen, C.; Fangling, B.; Jianheng, Z.; Peimin, H. Attached Ulva meridionalis on nearshore dikes may pose a new ecological risk in the Yellow Sea. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 332, 121969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Mindy, L.R.; Taylor, R.S.; David, M.K.; Donald, M.A.; Zhonghua, C. Microbial Community Structure and Associations During a Marine Dinoflagellate Bloom. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, W. Exploring bacteria-induced growth and morphogenesis in the green macroalga order Ulvales (Chlorophyta). Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gragnani, A. Water Control Policies in Lakes with Vertical Heterogeneity: An Algal Competition Modelling Approach. In Proceedings of the 2024 European Control Conference (ECC), Stockholm, Sweden, 25–28 June 2024; pp. 850–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guang, G.; Zhihai, Z.; Xianghong, Z.; Juntian, X. Changes in morphological plasticity of Ulva prolifera under different environmental conditions: A laboratory experiment. Harmful Algae 2016, 59, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Po, H.; Yahao, L.; Yijun, H.; Yuqi, Y. An early forecasting method for the drift path of green tides: A case study in the Yellow Sea, China. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2018, 71, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menghao, J.; Xin, D.; Chengyi, Z.; Jianting, Z. Exploring the Green Tide Transport Mechanisms and Evaluating Leeway Coefficient Estimation via Moderate-Resolution Geostationary Images. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jae-Hong, M.; Naoki, H.; Jong-Hwan, Y. Comparison of wind and tidal contributions to seasonal circulation of the Yellow Sea. J. Geophys. Res. 2009, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, M.; Guan, W.; Wang, Z.; Wang, D.; Cao, Z.; Chen, Q. Features of the physical environment associated with green tide in the southwestern Yellow Sea during spring. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2015, 34, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.-J.; Kuo, N.-J.; Doong, D.-J.; Hsu, T.-W. Numerical study of wind effect on green island wake. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2014 TAIPEI, Taipei, Taiwan, 7–10 April 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dongxue, L.; Zhiqiang, G.; Debin, S.; Weitao, S.; Xiaopeng, J. Characteristics and influence of green tide drift and dissipation in Shandong Rongcheng coastal water based on remote sensing. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2019, 227, 106335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Ge, J.; Liu, D.; Ding, P.; Chen, C.; Wei, X. The Lagrangian-based Floating Macroalgal Growth and Drift Model (FMGDM v1. 0): Application to the Yellow Sea green tide. Geosci. Model Dev. 2021, 14, 6049–6070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmitry, A.; Andrew, C.D.; Marie, P.; Keith, D. A high resolution hydrodynamic model system suitable for novel harmful algal bloom modelling in areas of complex coastline and topography. Harmful Algae 2016, 53, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sensor | Band No. | Spectral Range/μm |

|---|---|---|

| HY-1C/D CZI | Band1 (Blue) | 0.421–0.500 |

| Band2 (Green) | 0.517–0.598 | |

| Band3 (Red) | 0.608–0.690 | |

| Band4 (NIR) | 0.761–0.891 |

| Band Combination | Function | Fitting Model | R2 | RMSE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (B2 + B3)/B4 | Linear | 0.8312 | 10.99 | |

| (B2 + B3)/B4 | Power | 0.0784 | 12.22 | |

| (B2 + B3)/B4 | Exponential | 0.7548 | 8.22 | |

| (B1 + B4)/B3 | Linear | 0.7081 | 2.71 | |

| (B1 + B4)/B3 | Power | 0.7458 | 2.45 | |

| (B4 − B3)/(B1 + B2) | Linear | 0.7304 | 11.23 | |

| (B4 − B3)/(B1 + B2) | Power | 0.8417 | 8.82 | |

| (B4 − B3)/(B1 + B2) | Exponential | /0.1741)2) | 0.8644 | 8.03 |

| (B4 − B2)/(B1 + B2) | Linear | 0.7257 | 10.56 | |

| (B4 − B2)/(B1 + B2) | Power | 0.8528 | 8.26 | |

| (B4 − B2)/(B1 + B2) | Exponential | 0.8477 | 7.94 | |

| B4/B1 | Linear | 0.8462 | 10.99 | |

| B4/B2 | Power | 0.0841 | 12.22 | |

| B4-B3 | Linear | 0.7854 | 8.22 | |

| (B4 − B3)/B2 | Linear | 0.7054 | 2.71 | |

| (B2 + B3)/B4 | Power | 0.7654 | 2.45 | |

| (B4 − B3)/(B1 + B2) | Linear | 0.9315 | 1.23 |

| Method | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| LGA-M | 0.961 | 0.952 | 0.946 |

| NDVI | 0.842 | 0.837 | 0.845 |

| FAI | 0.865 | 0.843 | 0.837 |

| EVI | 0.884 | 0.869 | 0.862 |

| Date | Satellite | Coverage Area (km2) | Area Difference Ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20 July 2019 | GF-1 | 580.38 | |

| MODIS | 936.71 | 61.4 | |

| HY-1C/D | 610.06 | 5.1 | |

| 21 June 2021 | GF-1 | 821.04 | |

| MODIS | 1123.43 | 36.8 | |

| HY-1C/D | 914.87 | 11.4 | |

| 10 July 2021 | GF-1 | 759.88 | |

| MODIS | 1085.62 | 42.9 | |

| HY-1C/D | 740.56 | 2.5 | |

| 22 June 2023 | GF-1 | 550.44 | |

| MODIS | 643.84 | 17.0 | |

| HY-1C/D | 496.54 | 9.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mao, T.; Cai, L.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Liu, X. A Coastal Zone Imager-Based Model for Assessing the Distribution of Large Green Algae in the Northern Coastal Waters of China. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2026, 14, 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14020140

Mao T, Cai L, Xu Y, Zhang B, Liu X. A Coastal Zone Imager-Based Model for Assessing the Distribution of Large Green Algae in the Northern Coastal Waters of China. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2026; 14(2):140. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14020140

Chicago/Turabian StyleMao, Tianle, Lina Cai, Yuzhu Xu, Beibei Zhang, and Xuan Liu. 2026. "A Coastal Zone Imager-Based Model for Assessing the Distribution of Large Green Algae in the Northern Coastal Waters of China" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 14, no. 2: 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14020140

APA StyleMao, T., Cai, L., Xu, Y., Zhang, B., & Liu, X. (2026). A Coastal Zone Imager-Based Model for Assessing the Distribution of Large Green Algae in the Northern Coastal Waters of China. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 14(2), 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14020140