Machine Learning Applications in Fuel Reforming for Hydrogen Production in Marine Propulsion Systems

Abstract

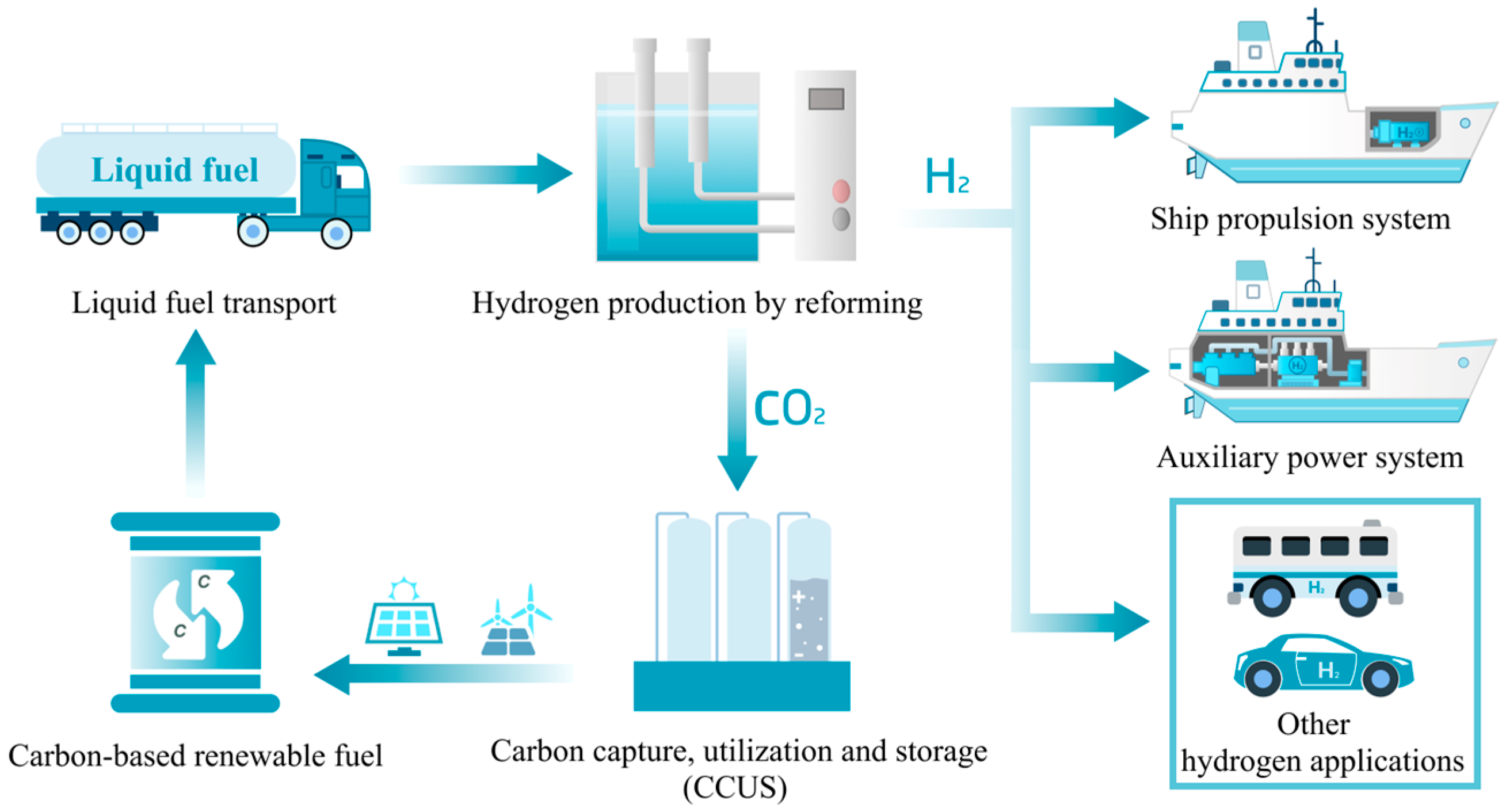

1. Introduction

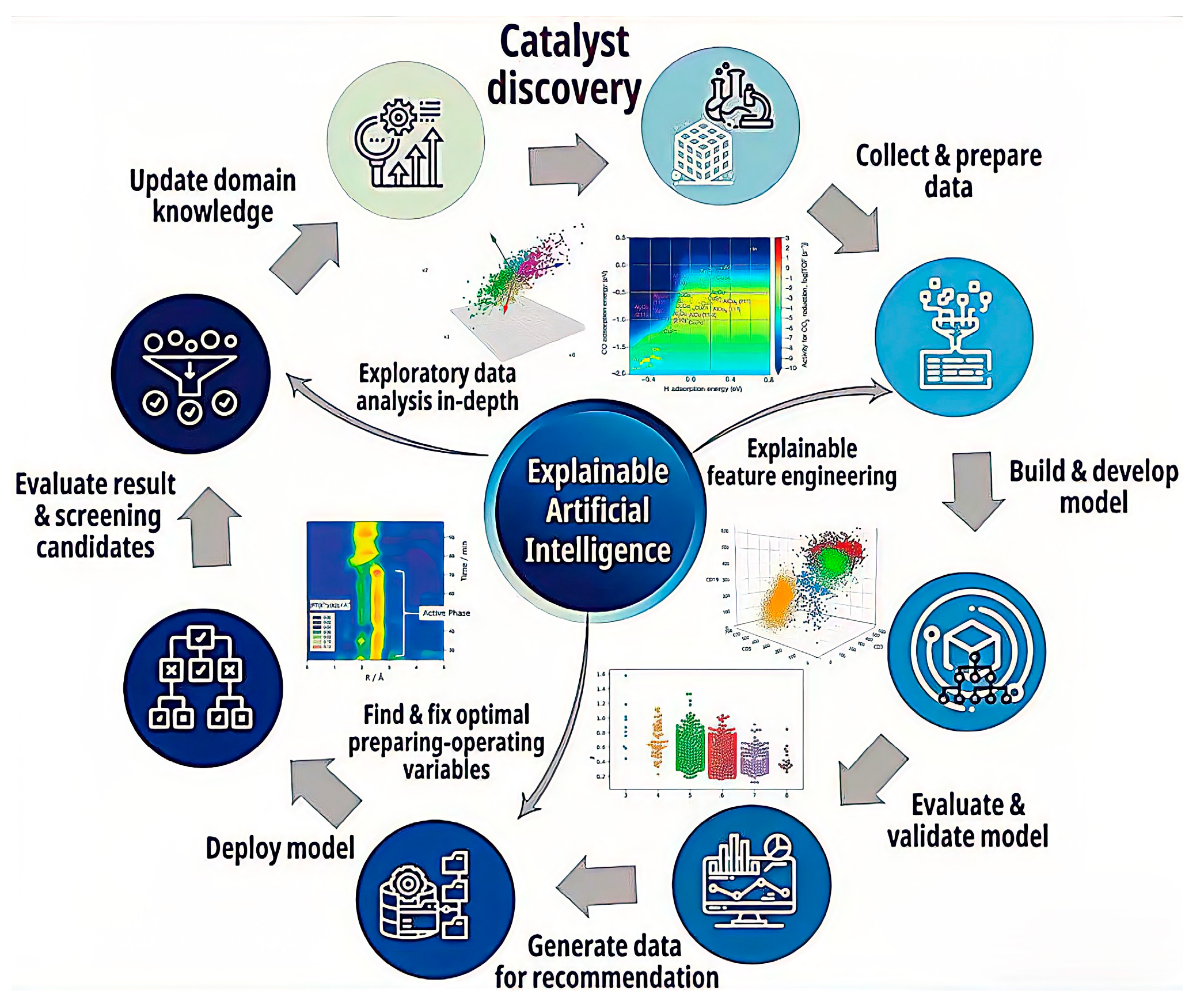

2. Catalyst Design and Optimization via Machine Learning

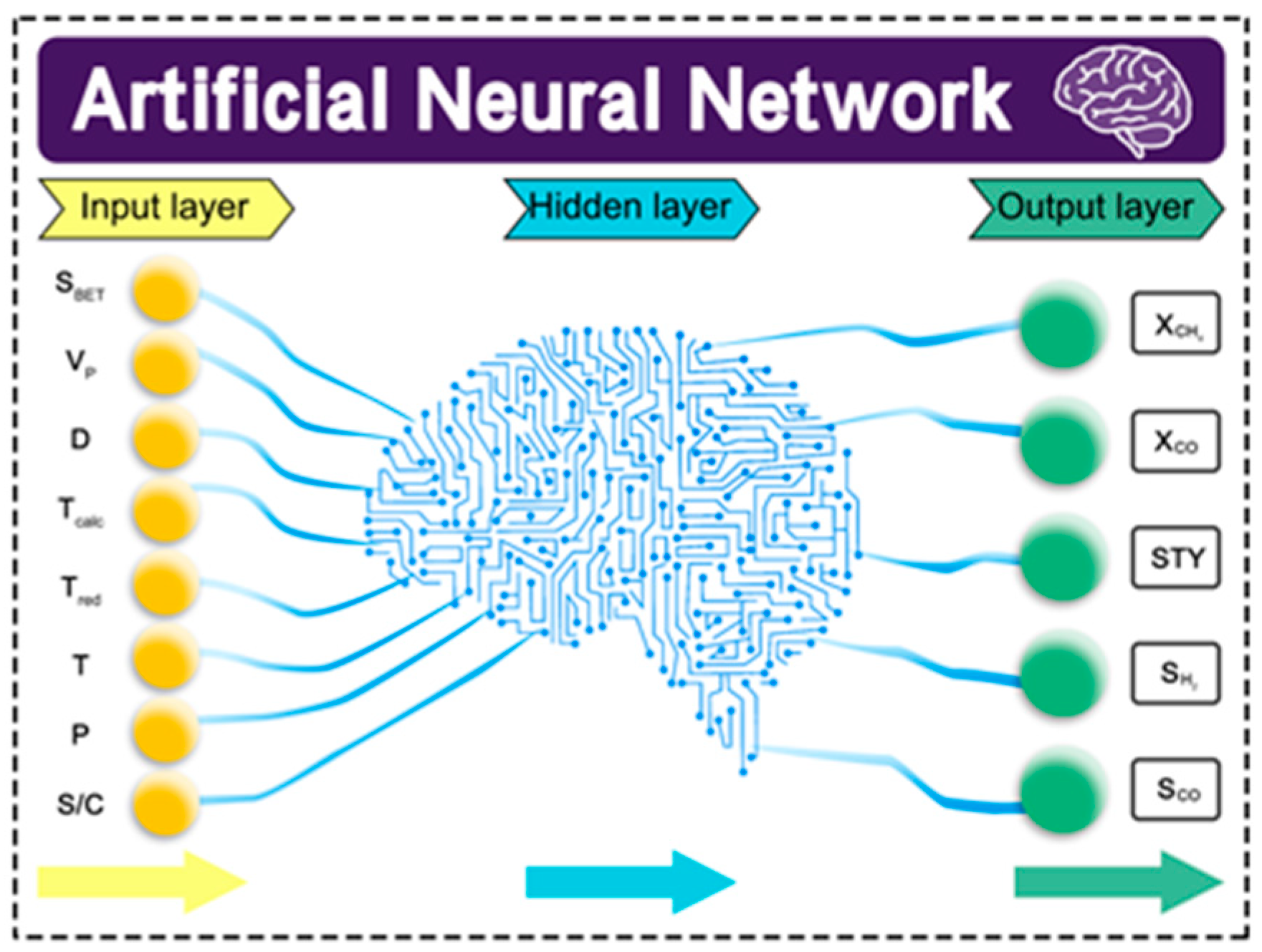

2.1. Prediction of Catalyst Performance

2.1.1. Key Inputs and Outputs of the Prediction Model

- Catalyst synthesis parameters, such as preparation method, precursor type, calcination temperature, reduction temperature, and stirring time, etc.

- Activity indicators, such as methane conversion rate (X_CH4), carbon dioxide conversion rate (X_CO2), and carbon monoxide conversion rate (X_CO), as well as the space-time yield (STY) for processes like WGS and methanol synthesis, etc.

- Stability indicators, such as catalyst deactivation rate and the retention of activity after a specific period, etc. [44].

- Other performance indicators, such as hydrogen production rate and syngas (H2/CO) ratio, etc.

2.1.2. Mainstream Machine Learning Algorithms and Their Applications

2.1.3. Predictive Studies for Different Reaction Systems

2.2. High-Throughput Screening and the Design of Novel Catalysts

2.2.1. Synergistic Screening Based on First-Principles Calculations and Machine Learning

2.2.2. Closed-Loop Optimization of High-Throughput Experimentation and ML

2.2.3. Design of High-Entropy Alloys and Multicomponent Catalysts

2.2.4. Identification and Design of Catalyst Active Sites

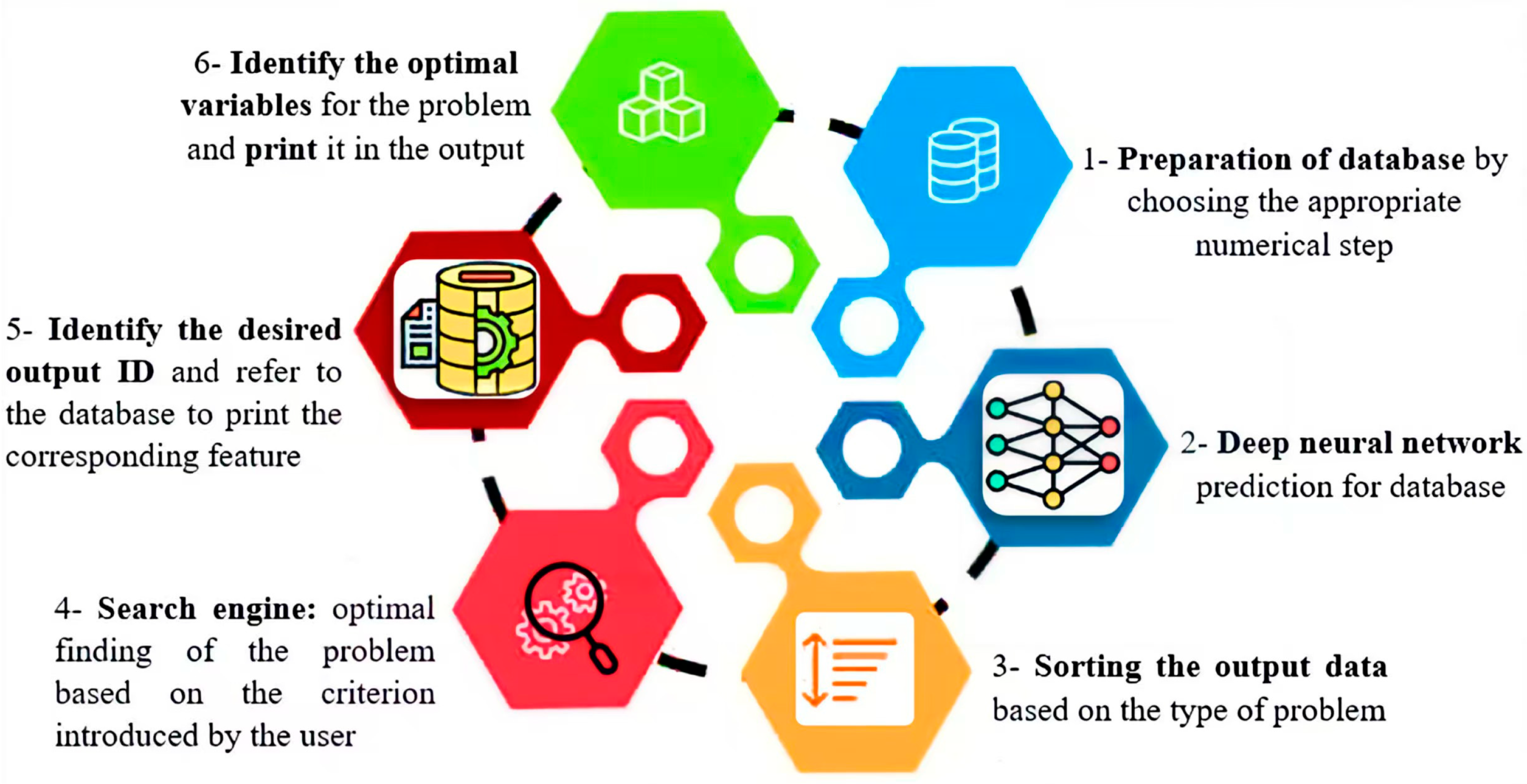

2.3. Optimization of Synthesis Conditions and Active Site Regulation

2.3.1. Global Optimization of Synthesis Parameters

2.3.2. Prediction and Control of Microstructure

2.3.3. Interpretable Machine Learning for Revealing Key Regulatory Factors

2.3.4. Regulation of the Electronic Structure of Active Sites

2.3.5. Inverse Design Framework

3. Reaction Process Modeling Aided by Machine Learning

3.1. Chemical Reaction Kinetics Models

3.1.1. ML Replacement and Enhancement of Traditional Mechanistic Models

3.1.2. Kinetic Analysis of Complex Reaction Networks

3.2. Multiscale Simulation and Data Fusion Strategies

3.2.1. Integration of Atomic-Scale Models and Machine Learning

3.2.2. Kinetic Modeling at the Reaction Scale and Machine Learning

3.2.3. Data Fusion Strategies and Cross-Scale Validation

3.3. Interpretable Analysis of Reaction Pathways and Mechanisms

3.3.1. Application of Interpretable Machine Learning Tools

3.3.2. Integration of DFT and Machine Learning for Mechanistic Studies

3.3.3. Reaction Pathway Analysis

4. Machine Learning in Equipment Design and System Process Optimization

4.1. Reactor Structure Optimization

4.1.1. CFD-ML-Based Reactor Design

4.1.2. Structural Parameter Optimization with Integrated Optimization Algorithms

4.2. Multi-Objective Collaborative Optimization of Process Parameters

4.2.1. Surrogate Models for Accelerating Multi-Objective Optimization

4.2.2. Integrated Technical-Economic-Environmental Optimization

4.3. Reactor Performance Prediction and Real-Time Monitoring

4.3.1. Soft Measurement and Dynamic Prediction of Key Parameters

4.3.2. Catalyst Deactivation Prediction and Maintenance Strategy Optimization

4.4. System Integration and Intelligent Control Strategies

4.4.1. Collaborative Optimization of Multi-Energy Systems

4.4.2. Intelligent Adaptive Control

5. Conclusions and Future Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Hydrogen Production Methods | Machine Learning Approaches | Inputs | Outputs | Model Performance | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methane Dry Reforming | Machine Learning-Driven Optimization of Catalyst Design | Catalyst Materials (Metal–Organic Framework, MXene, Biochar-Based), Reaction Parameters | Conversion Rate, Selectivity, Carbon Deposition Resistance | ML can enhance the depth of data analysis, improve the accuracy of catalyst design, accelerate catalyst development, and guide experimental design | [93] |

| Methane Dry Reforming | Interpretable Machine Learning, utilizing SHapley Additive exPlanations and Partial Dependence Values tools | Catalyst Parameters (Type of Promoter, Support Properties), Reaction Conditions (Temperature, Fuel-to-Oxidant Ratio, Space Velocity) | Methane Conversion Rate, Carbon Dioxide Conversion Rate, Hydrogen Production Rate, Carbon Deposition Amount | The model exhibits high prediction accuracy, with experimental validation showing an R2 value greater than 0.9 and a low RMSE | [36] |

| Methane Dry Reforming | Machine Learning for Unbiased Data Set Analysis | Catalyst Elemental Composition | Catalyst Activity and Carbon Deposition Suppression | The model demonstrates high prediction accuracy and plays a key role in identifying elements such as aluminum and niobium | [52] |

| Methane Dry Reforming | An explainable CatBoost model, enhanced with interpretability tools, to improve transparency | Reaction temperature, gas hourly space velocity (GHSV), calcination temperature, nickel loading, and catalyst structural parameters | Methane Conversion Rate | The CatBoost model predicts the methane conversion rate with an R2 value of 0.91, and experimental validation shows an error of less than 10% | [37] |

| Methane Dry Reforming | Application of Machine Learning in CT Image Segmentation | Microstructural Data, Computed Tomography (CT), Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (EDS) | Catalyst Degradation and Microcrack Formation | Phase distribution is achieved through CT segmentation and EDX; ML is used solely for image segmentation | [94] |

| Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production | Artificial Neural Network (ANN) Model | Catalyst Type, Light Conditions, Reaction Time | Hydrogen Production Efficiency (μmol g−1 h−1) | The ANN model predicts hydrogen production efficiency with high accuracy, as confirmed by experimental validation | [95] |

| Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production | Machine learning is used solely for optimizing parameters in biological hydrogen production (ANN) | Fermentation Temperature, pH Value, Substrate Concentration | Biological Hydrogen Production Rate | Prediction of Biological Hydrogen Production Rate and Optimization of Operating Parameters | [96] |

| Biomass Catalytic Pyrolysis for Hydrogen Production | Random Forest, Regression Model | Reaction Temperature, Carbon Content, Calcination Temperature, Nickel Loading, Biomass Type | Hydrogen Production | The RF model predicts hydrogen production with an R2 of 0.78 and an RMSE of 0.47 | [27] |

| Catalytic Steam Reforming of Biomass Tar | Machine Learning Algorithms (RF, ANN) for Optimizing Nickel-Based Catalysts | Reaction Temperature, Catalyst Support, Additive Type, Nickel Loading, Calcination Temperature | Toluene Conversion Rate | The RF model for predicting toluene conversion rate was evaluated with an accuracy of 0.99 and an AUC of 0.92 | [38] |

| Carbon Dioxide Methanation | Explainable Machine Learning (SHAP Analysis), XGBoost | Reaction temperature, nickel content, calcination temperature, particle size, reduction time | Carbon dioxide conversion rate, methane selectivity | The XGBoost model demonstrates high prediction accuracy, as verified through experimental validation | [39] |

| Dry Reforming of Methane (CO2 Methanation) | Multilayer Perceptron and Nonlinear Autoregressive Exogenous (NARX) Neural Networks | Calcination temperature, reduction temperature, reaction temperature, reaction time, and Ni loading | Methane conversion rate, carbon dioxide conversion rate | The NARX neural network achieves the highest R2 = 0.998 and the lowest MSE = 3.24 × 10−9 | [40] |

| Hydrogenation of carbon dioxide to produce methanol | Machine learning models (ANN, Support Vector Machine Regression) | Catalyst composition and reaction conditions (temperature, pressure, space velocity) | Carbon dioxide conversion, methanol selectivity, carbon monoxide selectivity, and methanol space-time yield | The ANN demonstrates high predictive accuracy for all four output variables, with R2 > 0.9 | [58] |

| Hydrogen Production through the Catalytic Hydrolysis of Sodium Borohydride | Machine Learning–Assisted Optimization (RF, AdaBoost, and GBDT) | Catalyst Synthesis Parameters (Composition of Co–P–B/ZIF-67) and Reaction Conditions (Temperature and Concentration) | Hydrogen Yield and Reaction Rate | The R2 values of the Random Forest model range from 0.956 to 0.995. After optimization, the removal of outliers enhanced the prediction stability | [42] |

| The Water–Gas Shift reaction (WGS) | Bayesian optimization integrated with RF and ANN | Catalyst Composition and Operating Conditions (Temperature, Feed Composition, Contact Time, Calcination Time) | Catalyst Activity, Stability, and Cost-effectiveness | Improvement in Optimized Catalyst Performance Indicators and Prediction Accuracy (R2 > 0.9) | [97] |

| Sorption-Enhanced Chemical Looping Reforming | Artificial Neural Network | Operating Parameters (Temperature, Pressure, Flow Rate) and Catalyst/Adsorbent Properties | Methane Conversion Rate, Hydrogen Purity, and Carbon Dioxide Removal Efficiency | The ANN model demonstrates high prediction accuracy, R2 ≥ 0.9889 | [41] |

Appendix A.2

| Application Scenarios | Machine Learning Approaches | Inputs | Outputs | Model Performance | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steam Methane Reforming | Deep Neural Networks Combined with Random Search Optimization Algorithm | Reactor length, feed flow rate, heat flux, S/C (steam-to-carbon ratio) | Hydrogen yield | The DNN model offers high prediction accuracy and the capability for multi-objective optimization | [28] |

| Electrically Heated Steam Methane Reforming | Model Predictive Control (MPC) based on Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN) and Improved Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Networks | Current, feed flow rate, argon flow rate, reactor temperature | Hydrogen yield | The LSTM-MPC under disturbances results in an error of less than 3%, with tracking accuracy significantly outperforming traditional control methods | [78] |

| Integration of SMR and NET Power Cycle | ML Model Prediction and GA-based Process Optimization | Reaction temperature, pressure | Levelized Cost of Hydrogen (LCOH), carbon dioxide emissions, system efficiency | After optimization, the LCOH decreased to $3.39 kg−1, and the energy required for capture was reduced by 54% | [77] |

| Methane Autothermal Reforming | Deep Reinforcement Learning combined with Random Forest models and Q-learning algorithm | Oxygen-to-methane ratio, steam-to-methane ratio, temperature | Operating expenses, carbon emissions per unit time, hydrogen yield | After DRL optimization, OPEX decreased by 10%, carbon footprint was significantly reduced compared to traditional processes, and hydrogen yield increased by 13% | [79] |

| Solar-driven Methanol Steam Reforming | Grey Relational Analysis (GRA) and Genetic Algorithm Optimized BP Neural Network (GA-BPNN) | Reaction temperature, methanol flow rate | Methanol conversion rate, hydrogen yield, carbon monoxide selectivity | The GA-BPNN model demonstrates high prediction accuracy, outperforming traditional prediction models | [84] |

| Solar Photovoltaic/Thermal (PV/T) System for Hydrogen Production | Stacked Ensemble Model (Random Forest, XGBoost) | Solar irradiance, temperature, water flow rate, PV/T type, operating conditions | Hydrogen yield | The R2 value of the stacked model for prediction accuracy is 0.9986 | [98] |

| Solar-Driven Green Hydrogen Production | Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) and Singular Spectrum Analysis (SSA) combined with Deep Learning (GRU) | Global Horizontal Irradiance (GHI) | GHI multi-step prediction, photovoltaic power generation estimation, hydrogen yield prediction | The R2 value of the noise-robust model for Global Horizontal Irradiance prediction is 0.99, which supports the achievement of low-emission targets | [99] |

| Fuel Cell and Ammonia-Hydrogen Internal Combustion Engine Hybrid System | Integrated Deep Learning (PCA, MCNN, SVM) | Voltage, current, temperature, pressure, fault signals | Fault diagnosis accuracy, system reliability | Overall diagnostic accuracy of 98.15%, with multi-system fault diagnosis at 96.67% | [85] |

| Solid Oxide Fuel Cell and Integrated System | Multiphysics model combined with Deep Learning and Multi-objective Genetic Algorithm | S/C, operating temperature, fuel flow rate | Power density, maximum temperature gradient, carbon deposition rate | Achieving a multi-objective balance of “significantly reducing carbon deposition, maintaining high power density, and controlling safe temperature gradients” | [100] |

| Biomass-driven SOFC Combined Heat and Power (CHP) System | Triple-objective optimization using the Grey Wolf Algorithm | Biomass flow rate, operating temperature, pressure, fuel utilization efficiency | Power output, hydrogen yield, ammonia yield, system cost | After optimization, cost is minimized, efficiency is maximized, and ammonia yield is maximized | [101] |

| Biomass Gasification for Hydrogen Production | Gradient Boosting Regression Model combined with Particle Swarm Optimization | Biomass type, temperature, reaction time, biomass concentration, pressure, reactor type | Hydrogen yield | After PSO, the test R2 of the Gradient Boosting Regression model is 0.958, and its cross-validation R2 is 0.917 | [86] |

| Co-gasification of biomass and plastic for hydrogen production | Attention Mechanism-based Multi-Layer Perceptron Model (agMLP) | Temperature, plastic percentage, HDPE particle size, RSS particle size | Hydrogen yield | The agMLP model predicts hydrogen concentration with an R2 of 0.997, robustness to be improve | [102] |

| Co-gasification of Biomass and Plastic | Gradient Boosting | Particle size, temperature, mixing ratio | Hydrogen yield | The gradient boosting model exhibits the best prediction performance, with an R2 of 0.99 | [103] |

| Industrial-Scale Vacuum Pressure Swing Adsorption (VPSA) | ANN combined with evolutionary algorithm optimization | Feed flow rate, purge ratio, feed pressure, vacuum pressure | Hydrogen purity, recovery rate, generation rate, energy consumption | After ANN optimization, purity reached 99.99%, and the efficiency was 45.2% | [104] |

| Pressure Swing Adsorption (PSA) | ANN and NSGA-II Optimization | Feed composition, pressure sequence, temperature, adsorbent properties | Hydrogen purity, recovery rate, production rate | The ANN model exhibits high prediction accuracy, while NSGA-II identifies the optimal operating conditions | [105] |

| Pressure Swing Adsorption Hydrogen Purification | DNN and NSGA-II Optimization | Adsorbent sequence, CuBTC bed length, feed flow rate, adsorption pressure | Hydrogen purity, recovery rate | The prediction accuracy of DNN yields an R2 of 0.98, and NSGA-II identifies the optimal solution | [106] |

| Proton Exchange Membrane Water Electrolyzer (PEMWE) | Cascaded Feedforward Neural Network (CFNN) | Current density, temperature, anode material, water flow rate | Cell potential | The CFNN model predicts the cell potential with an R2 of 0.99998, demonstrating high stability | [107] |

| Supercritical Water Gasification (SCWG) | SVR, ABR, DT, RF, GBR | Temperature, concentration, catalyst, residence time | Hydrogen yield, gas composition | The GBR model predicts hydrogen yield with an R2 of 0.997, and the MSE for H2 prediction using GBR is 0.54 | [108] |

| Supercritical Water Gasification for Hydrogen Production | Integrated Tree AdaBoost Regressor (ELA) combined with Differential Evolution Optimization (DEO) | Biomass type, reaction temperature, residence time, catalyst concentration | Hydrogen yield | The ELA model predicts hydrogen yield with an R2 of 0.95 and an RMSE of 0.091 | [109] |

| Dehydrogenation of Liquid Organic Hydrogen Carriers (LOHC) | Machine Learning and Genetic Algorithm Integrated Framework | Temperature, pressure, catalyst composition, support type | Methylcyclohexane conversion rate, toluene selectivity | The conversion exceeds 90%, and the selectivity exceeds 85%. For predictive performance, the R2 value for methylcyclohexane (MCH) conversion prediction is 0.962, while the R2 value for toluene selectivity prediction is 0.991 | [35] |

| Hydrogen Compressed Natural Gas (HCNG) Engine Waste Heat Recovery | Stepwise Linear Regression (SLR) Model | Exhaust gas temperature, S/C, pressure, thermal load | Hydrogen yield | The SLR model predicts hydrogen production with an R2 of 0.99, with the minimum RMSE of 0.074 and minimum MAE of 0.06 | [110] |

| Biogas Dry Reforming Process | Random Forest Classification Model combined with SHAP | Temperature, pressure, operating time, humidity | Operating condition classification, fault prediction | Random Forest state prediction accuracy, with SHAP identifying key variables | [111] |

| Hybrid Wind-Hydrogen Energy Plant | Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning (MARL) | Wind speed, electricity price, grid status, air density | Day-ahead trading profit, hydrogen yield, grid balance revenue | The MARL strategy increases total profit by 4%, with an annual increase of 7 million euros | [112] |

| Hybrid Renewable Energy System | Mountain Gazelle Optimizer and Transformer Architecture (MGO-Transformer) | Wind speed, temperature, relative humidity, cloud cover | Direct Normal Irradiance (DNI) prediction, energy cost, hydrogen cost | The MGO-Transformer predicts DNI with an R2 of 0.998, and the system’s LCOH is $5.26 kg−1, making it more economical | [113] |

References

- Bayraktar, M.; Yuksel, O. A scenario-based assessment of the energy efficiency existing ship index (EEXI) and carbon intensity indicator (CII) regulations. Ocean Eng. 2023, 278, 114295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhaka, V.; Samuelsson, B. Hydrogen as fuel in the maritime sector: From production to propulsion. Energy Rep. 2024, 12, 5249–5267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamam, M.Q.M.; Dansoh, C.; Panesar, A. The roadmap to carbon neutrality for the maritime industry: An insight into various routes to decarbonise ship engines. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 27, 101184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anekwe, I.M.S.; Mustapha, S.I.; Akpasi, S.O.; Tetteh, E.K.; Joel, A.S.; Isa, Y.M. The hydrogen challenge: Addressing storage, safety, and environmental concerns in hydrogen economy. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 167, 150952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.; Fernandes, R.J.; Turner, J.W.G.; Emberson, D.R. Life cycle assessment of ammonia and hydrogen as alternative fuels for marine internal combustion engines. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 112, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Kanchiralla, F.M.; Schulte, F.; Polinder, H.; Tukker, A.; Steubing, B. Life cycle assessment of hydrogen-based fuels use in internal combustion engines of container ships until 2050. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2026, 226, 108671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.; Phil, S.; Nigel, B.; Anthony, K. System-level comparison of ammonia, compressedand liquid hydrogen as fuels for polymerelectrolyte fuel cell powered shipping. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 13, 8565–8584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamboni, G.; Scamardella, F.; Gualeni, P.; Canepa, E. Comparative analysis among different alternative fuels for ship propulsion in a well-to-wake perspective. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, W.; Chen, L.; Wang, Z.; Chen, J.; Ye, Q.; Fan, H. A 500 kw hydrogen fuel cell-powered vessel: From concept to sailing. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 89, 1466–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Dong, B.; Wang, Y.; Li, M.; Liu, H.; Han, F. Analysis and evaluation of fuel cell technologies for sustainable ship power: Energy efficiency and environmental impact. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 21, 100482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radica, G.; Tolj, I.; Nyamsi, S.N.; Vidović, T. Performances of proton exchange membrane fuel cells in marine application. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 142, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manias, P.; Teagle, D.A.H.; Hudson, D.; Turnock, S. Hybrid hydrogen fuel cell and internal combustion engine powertrain arrangements for large maritime applications. Ocean Eng. 2026, 343, 123505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Yan, X.; Xia, M.; Wang, C.; Wang, S. Thermodynamic and economic analysis, optimization of SOFC/GT/SCO2/ORC hybrid power systems for methanol reforming-powered ships with carbon capture. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 67, 105840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, W.; Choi, M.; Jeong, J.; Lee, J.; Chang, D. Design and analysis of liquid hydrogen-fueled hybrid ship propulsion system with dynamic simulation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 50, 951–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhaledi, A.N.; Sampath, S.; Pilidis, P. Propulsion of a hydrogen-fuelled LH2 tanker ship. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 17407–17422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Guan, W.; He, H.; Wu, J.; Huang, F.; Wu, F. Effects of hydrogen doping on combustion and emissions of ammonia-diesel dual-fuel marine engine with different energy ratios. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 192, 152354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünlübayir, C.; Youssfi, H.; Khan, R.A.; Ventura, S.S.; Fortunati, D.; Rinner, J.; Börner, M.F.; Quade, K.L.; Ringbeck, F.; Sauer, D.U. Comparative analysis and test bench validation of energy management methods for a hybrid marine propulsion system powered by batteries and solid oxide fuel cells. Appl. Energy 2024, 376, 124183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashkzari, A.Z.; Mobasheri, R.; Seif, M.S. Comparative energy and environmental assessment of diesel, hybrid-electric, and fuel cell marine powertrains: Focusing on carbon footprint reduction during the onboard operational phase of maritime transportation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 192, 152322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, P.; Wu, D.; Hao, X.; Yang, T.; Cairns, A. Advancing maritime decarbonisation: Design and optimisation of ammonia-fuelled propulsion systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 535, 147145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wright, L.; Boccolini, V.; Ridley, J. Modelling environmental life cycle performance of alternative marine power configurations with an integrated experimental assessment approach: A case study of an inland passenger barge. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 947, 173661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motiramani, M.; Solanki, P.; Patel, V.; Talreja, T.; Patel, N.; Chauhan, D.; Singh, A.K. AI-ML techniques for green hydrogen: A comprehensive review. Next Energy 2025, 8, 100252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, U.S.; Purohit, B.K.; Byun, H. A comprehensive review of fossil-based hydrogen production: Technological integrations, environmental sustainability, and economic viability. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 140, 627–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hos, T.; Sror, G.; Herskowitz, M. Autothermal reforming of methanol for on-board hydrogen production in marine vehicles. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 49, 1121–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, S.K.S.; Ayodele, B.V. Towards a sustainable hydrogen-rich syngas production by methane dry reforming: Advances in catalyst synthesis and optimization strategies. Fuel 2026, 403, 136132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyangiwe, N.N. Applications of density functional theory and machine learning in nanomaterials: A review. Next Mater. 2025, 8, 100683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, M.; Hajialigol, N.; Fattahi, A. An insight into the application and progress of artificial intelligence in the hydrogen production industry: A review. Mater. Today Sustain. 2025, 30, 101098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persaud, V.V.; Hamrani, A.; Uzzi, M.; Munroe, N.D.H. Machine learning-guided optimization of nickel-based catalysts for enhanced biohydrogen production through catalytic pyrolysis of biomass. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 144, 1085–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafarizadeh, A.; Panjepour, M.; Emami, M.D. Advanced modelling and optimization of steam methane reforming: From CFD simulation to machine learning—Driven optimization. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 96, 1262–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, A.; Liu, H.; Wu, P.; Yang, L.; Guan, C.; Li, T.; Bucknall, R.; Liu, Y. LSTM-augmented DRL for generalisable energy management of hydrogen-hybrid ship propulsion systems. eTransportation 2025, 25, 100442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liao, P.; Long, F.; Wang, Z.; Han, F. Coordinated optimization of multi-energy systems in sustainable ships: Synergizing power-to-gas, carbon capture, hydrogen blending, and carbon trading mechanisms. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 165, 150755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liao, P.; Liu, S.; Ji, Y.; Han, F. Scenario-based energy management optimization of hydrogen-electric-thermal systems in sustainable shipping. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 99, 566–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizoń, Z.; Kimijima, S.; Brus, G. Bridging equilibrium and kinetics prediction with a data-weighted neural network model of methane steam reforming. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 175, 151367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonomano, A.; Papa, G.D.; Giuzio, G.F.; Maka, R.; Palombo, A.; Russo, G. Design and retrofit towards zero-emission ships: Decarbonization solutions for sustainable shipping. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 213, 115384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanni, D.; Di Cicco, G.; Minutillo, M.; Cigolotti, V.; Perna, A. Techno-economic assessment of a green liquid hydrogen supply chain for ship refueling. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 97, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Saboor, A.; Kwarteng, F.; Arslonnazar, K.; Saidalo, S.; Hyun, K.K.; Gadow, S.I.; Chen, L.; Xiao, R.; Luo, Z. Integrated machine learning and genetic algorithm framework for optimizing methylcyclohexane dehydrogenation in liquid organic hydrogen carrier systems. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 169, 151193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, J.; Park, H.; Kwon, H.; Joo, C.; Moon, I.; Cho, H.; Ro, I.; Kim, J. Interpretable machine learning framework for catalyst performance prediction and validation with dry reforming of methane. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2024, 343, 123454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Cui, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; He, B.; Liu, D. Machine learning reveals structure-performance relationships of dry reforming of methane catalysts and the potential influencing mechanisms. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 122, 332–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; He, H.; Wang, Y.; Xu, B.; Harding, J.; Yin, X.; Tu, X. Machine learning-driven optimization of Ni-based catalysts for catalytic steam reforming of biomass tar. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 300, 117879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L.M.D.; Melo, D.M.A.; Medeiros, R.L.B.A.; de Oliveira, Â.A.S.; Farias, W.A.S.; Santiago, R.A.B.N.; Braga, R.M. Data-driven design of Ni-based catalysts for CO2 methanation using interpretable machine learning. Mol. Catal. 2025, 586, 115450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamidele Victor Ayodele, M.A.A.; Mustapa, S.I.; Kanthasamy, R.; Wongsakulphasatch, S.; Cheng, C.K. Carbon dioxide reforming of methane over ni-based catalysts: Modeling the effect of process parameters on greenhouse gasses conversion using supervised machine learning algorithms. Chem. Eng. Process. 2021, 166, 108484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, R.; Rahimzadeh, H.; Heidarian, P.; Salimi, F. An ai-based modelling of a sorption enhanced chemical-looping methane reforming unit. Iran. J. Chem. Eng. 2022, 42, 2079–2089. [Google Scholar]

- Song, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, F.; Liu, Y.; Zuo, Z.; Luo, S.; Chen, D.; Zhao, F. Machine learning-assisted catalyst synthesis and hydrogen production via catalytic hydrolysis of sodium borohydride. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 129, 130–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, F.N.; Berrouk, A.S.; Salim, I.M. Scaling up dry methane reforming: Integrating computational fluid dynamics and machine learning for enhanced hydrogen production in industrial-scale fluidized bed reactors. Fuel 2024, 376, 132673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.A.; Ayodele, B.V.; Cheng, C.K.; Khan, M.R. Artificial neural network modeling of hydrogen-rich syngas production from methane dry reforming over novel Ni/CaFe2O4 catalysts. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 11119–11130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayodele, B.; Mustapa, S.; Alsaffar, M.; Cheng, C. Artificial intelligence modelling approach for the prediction of co-rich hydrogen production rate from methane dry reforming. Catalysts 2019, 9, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, M.; Lee, H.; Choe, C.; Cheon, S.; Lim, H. Machine learning based predictive model for methanol steam reforming with technical, environmental, and economic perspectives. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 426, 131639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Akande, A.J.; Idem, R.O.; Mahinpey, N. Inter-relationship between preparation methods, nickel loading, characteristics and performance in the reforming of crude ethanol over Ni/Al2O3 catalysts: A neural network approach. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2007, 20, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suvarna, M.; Araújo, T.P.; Pérez-Ramírez, J. A generalized machine learning framework to predict the space-time yield of methanol from thermocatalytic CO2 hydrogenation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2022, 315, 121530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saffary, S.; Rafiee, M.; Varnoosfaderani, M.S.; Günay, M.E.; Zendehboudi, S. Smart paradigm to predict copper surface area of Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 catalyst based on synthesis parameters. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2023, 191, 604–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotob, E.; Awad, M.M.; Umar, M.; Taialla, O.A.; Hussain, I.; Alsabbahen, S.I.; Alhooshani, K.; Ganiyu, S.A. Unlocking CO2 conversion potential with single atom catalysts and machine learning in energy application. iScience 2025, 28, 112306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, F.N.; Berrouk, A.S.; Saeed, M. Optimization of yield and conversion rates in methane dry reforming using artificial neural networks and the multiobjective genetic algorithm. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2023, 62, 17084–17099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Chammingkwan, P.; Takahashi, K.; Taniike, T. Unbiased dataset for methane dry reforming and catalyst design guidelines obtained by high-throughput experimentation and machine learning. J. Catal. 2025, 442, 115930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Kim, J. Comparative evaluation of artificial neural networks for the performance prediction of Pt-based catalysts in water gas shift reaction. Int. J. Energy Res. 2022, 46, 9602–9620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Kim, J. Machine learning-based high-throughput screening, strategical design and knowledge extraction of Pt/CeXZr1 − XO2 catalysts for water gas shift reaction. Int. J. Energy Res. 2022, 46, 21293–21308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eduardo, P.F.; Damián, C.; Fernando, M. A comparison of deep learning models applied to water gas shift catalysts for hydrogen purification. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 24742–24755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Huang, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, T. Impacts of process parameters on diesel reforming via interpretable machine learning. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 88, 658–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Yao, C.; Zuo, Z.; Bilal, M.; Zeb, H.; Lee, S.; Wang, Z.; Kim, T. Machine learning-driven catalyst design, synthesis and performance prediction for CO2 hydrogenation. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2025, 144, 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, A.; Ahluwalia, A.S.; Pant, K.K.; Upadhyayula, S. A principal component analysis assisted machine learning modeling and validation of methanol formation over Cu-based catalysts in direct CO2 hydrogenation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 324, 124576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbelaere, M.R.; Plehiers, P.P.; Van de Vijver, R.; Stevens, C.V.; Van Geem, K.M. Machine learning in chemical engineering: Strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. Engineering 2021, 7, 1201–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyao, T.; Maeno, Z.; Takakusagi, S.; Kamachi, T.; Takigawa, I.; Shimizu, K. Machine learning for catalysis informatics: Recent applications and prospects. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 2260–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittiruam, M.; Khamloet, P.; Ektarawong, A.; Atthapak, C.; Saelee, T.; Khajondetchairit, P.; Alling, B.; Praserthdam, S.; Praserthdam, P. Screening of Cu-Mn-Ni-Zn high-entropy alloy catalysts for CO2 reduction reaction by machine-learning-accelerated density functional theory. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 652, 159297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, N.K.; Roy, D.; Mandal, S.C.; Pathak, B. Rational designing of bimetallic/trimetallic hydrogen evolution reaction catalysts using supervised machine learning. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2022, 13, 7583–7593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zunger, A.; Wei, S.; Ferreira, L.G.; Bernard, J.E. Special quasirandom structures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1990, 65, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cursaru, D.; Doicin, B.; Mihai, S. Connection between CO/MCM-48 catalyst synthesis conditions and performances in the steam reforming process through artificial neural network. Dig. J. Nanomater. Biostruct. 2017, 12, 483–494. [Google Scholar]

- de Araujo, L.G.; Vilcocq, L.; Fongarland, P.; Schuurman, Y. Recent developments in the use of machine learning in catalysis: A broad perspective with applications in kinetics. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 508, 160872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, H.; Du, C.; Hong, W. Sorption-enhanced steam methane reforming parameter analysis and performance prediction of ensemble learning methods using improved drag model. Adv. Powder. Technol. 2024, 35, 104576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.I.; Rehman, A.; Khan, Z.A.; Athar, M.; Aadil, M.A.; Butt, T.E. Novel insights into extraction and utilization of subsurface free natural hydrogen present in rocks: Bibliometric analysis, opportunities, challenges and possible solutions. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 138, 958–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Liu, P. Investigation of ML algorithms for prediction of CFD data of fluid flow inside a packed-bed reactor. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 70, 106093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aklilu, E.G.; Bounahmidi, T. Machine learning applications in catalytic hydrogenation of carbon dioxide to methanol: A comprehensive review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 61, 578–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Liang, Z.; Liu, Y. Smart reforming for hydrogen production via machine learning. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2025, 304, 120959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coşgun, A.; Günay, M.E.; Yıldırım, R. Explainable machine learning analysis of tri-reforming of biogas for sustainable syngas production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 127, 595–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Teng, C.; Chein, R.; Nguyen, T.; Dong, C.; Kwon, E.E. Co-production of hydrogen and biochar from methanol autothermal reforming combining excess heat recovery. Appl. Energy 2025, 381, 125152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugwu, L.I.; Morgan, Y.; Ibrahim, H. Application of density functional theory and machine learning in heterogenous-based catalytic reactions for hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 2245–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Won, W.; Kim, J. Early-stage evaluation of catalyst using machine learning based modeling and simulation of catalytic systems: Hydrogen production via water–gas shift over pt catalysts. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 14417–14432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, T.; Wang, J.; Yu, X.; Tian, H.; Gao, X.; Huang, Z.; Chang, C. Machine learning-assisted screening of sa-flp dual-active-site catalysts for the production of methanol from methane and water. Chin. J. Catal. 2025, 70, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, H.; Du, C.; Hong, W. Optimizing hydrogen yield in sorption-enhanced steam methane reforming: A novel framework integrating chemical reaction model, ensemble learning method, and whale optimization algorithm. J. Energy Inst. 2024, 114, 101649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, G.; Zheng, L.; Yang, C.; Li, G.; Xiao, J. Performance analysis of a novel smr process integrated with the oxy-combustion power cycle for clean hydrogen production. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2025, 302, 120861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cui, X.; Peters, D.; Çıtmacı, B.; Alnajdi, A.; Morales-Guio, C.G.; Christofides, P.D. Machine learning-based predictive control of an electrically-heated steam methane reforming process. Digit. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 100173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahriari, S.; Iranshahi, D. Simultaneous opex and carbon footprint reduction with hydrogen enhancement in autothermal reforming: A machine learning–based surrogate modeling and optimization framework. Results Eng. 2025, 27, 106286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Keane, A.; Dumesic, J.A.; Huber, G.W.; Zavala, V.M. A machine learning framework for the analysis and prediction of catalytic activity from experimental data. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2020, 263, 118257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esterhuizen, J.A.; Goldsmith, B.R.; Linic, S. Interpretable machine learning for knowledge generation in heterogeneous catalysis. Nat. Catal. 2022, 5, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhu, K.; Sui, Z.; Chen, D.; Zhu, Y.; Zhou, X. High-throughput screening of alloy catalysts for dry methane reforming. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 8881–8894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allal, Z.; Noura, H.N.; Salman, O.; Vernier, F.; Chahine, K. A review on machine learning applications in hydrogen energy systems. Int. J. Thermofluids 2025, 26, 101119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Yang, J.; Yuan, F.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J. Investigation of a solar-assisted methanol steam reforming system: Operational factor screening and computational fluid dynamics data-driven prediction. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2024, 276, 113044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, B.; Xu, J.; Chen, Z.; Zheng, X.; Zhu, K.; Bo, Z.; Yang, Y.; Wang, X. Fault diagnosis of the hybrid system composed of high-power pemfcs and ammonia-hydrogen fueled internal combustion engines using ensemble deep learning methods. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 92, 1215–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandelwal, K.; Nanda, S.; Dalai, A.K. Machine learning modeling of supercritical water gasification for predictive hydrogen production from waste biomass. Biomass Bioenergy 2025, 197, 107816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasrabadi, M.; Anggono, A.D.; Budovich, L.S.; Abdullaev, S.; Opakhai, S. Optimizing membrane reactor structures for enhanced hydrogen yield in ch4 tri-reforming: Insights from sensitivity analysis and machine learning approaches. Int. J. Thermofluids 2024, 22, 100690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Ma, Y.; Maroufmashat, A.; Zhang, N.; Li, J.; Xiao, X. Optimal design of large-scale solar-aided hydrogen production process via machine learning based optimisation framework. Appl. Energy 2022, 305, 117751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojtahed, A.; Lo Basso, G.; Pastore, L.M.; Sgaramella, A.; de Santoli, L. Application of machine learning to model waste energy recovery for green hydrogen production: A techno-economic analysis. Energy 2025, 315, 134337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Emeksiz, C. Hydrogen fuel cell parameter estimation using an innovative hybrid estimation model based on deep learning and probability pooling. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 110, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumbhat, A.; Madaan, A.; Goel, R.; Appari, S.; Al-Fatesh, A.S.; Osman, A.I. Predicting nickel catalyst deactivation in biogas steam and dry reforming for hydrogen production using machine learning. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 191, 1833–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Lee, J.; Cho, H.; Kim, M.; Moon, I.; Kim, J. Multi-objective optimization of CO2 emission and thermal efficiency for on-site steam methane reforming hydrogen production process using machine learning. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 359, 132133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameen, S.; Farooq, M.U.; Samia; Umer, S.; Abrar, A.; Hussnain, S.; Saeed, F.; Memon, M.A.; Ajmal, M.; Umer, M.A.; et al. Catalyst breakthroughs in methane dry reforming: Employing machine learning for future advancements. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 141, 406–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, R.E.; Zhang, Y.S.; Neville, T.P.; Manos, G.; Shearing, P.R.; Brett, D.J.L.; Bailey, J.J. Visualising coke-induced degradation of catalysts used for CO2-reforming of methane with x-ray nano-computed tomography. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2022, 5, 100068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkumar, G.; Tamilselvi, M.; Jebaseelan, S.D.S.; Mohanavel, V.; Kamyab, H.; Anitha, G.; Prabu, R.T.; Rajasimman, M. Enhanced machine learning for nanomaterial identification of photo thermal hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 52, 696–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsapagh, R.M.; Sultan, N.S.; Mohamed, F.A.; Fahmy, H.M. The role of nanocatalysts in green hydrogen production and water splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 67, 62–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golder, R.; Pal, S.; Sathish Kumar, C.; Ray, K. Machine learning-enhanced optimal catalyst selection for water-gas shift reaction. Digit. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 100165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, S. Applying ensemble machine learning models to predict hydrogen production rates from conventional and novel solar PV/T water collectors. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 102, 1377–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sareen, K.; Panigrahi, B.K.; Shikhola, T.; Sharma, R.; Tripathi, R.N. A noise resilient multi-step ahead deep learning forecasting technique for solar energy centered generation of green hydrogen. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 90, 666–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, C.; Zhao, S.; Wang, J.; Zu, B.; Han, M.; Du, Q.; Ni, M.; Jiao, K. Coupling deep learning and multi-objective genetic algorithms to achieve high performance and durability of direct internal reforming solid oxide fuel cell. Appl. Energy 2022, 315, 119046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Z.; Ye, Z.; Zhang, C.; Liu, H. Development and process simulation of a biomass driven SOFC-based electricity and ammonia production plant using green hydrogen; Ai-based machine learning-assisted tri-objective optimization. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 133, 440–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukwuoma, C.C.; Cai, D.; Bamisile, O.; Bizi, A.M.; Amos, T.J.; Delali, F.L.; Thomas, D.; Huang, Q. Hydrogen production prediction from co-gasification of biomass and plastics using attention-gated MLP model. Renew. Energy 2025, 249, 123076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devasahayam, S.; Albijanic, B. Predicting hydrogen production from co-gasification of biomass and plastics using tree based machine learning algorithms. Renew. Energy 2024, 222, 119883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, X.; Liu, L.; Du, T.; Webley, P.A.; Li, G.K. Vacuum pressure swing adsorption intensification by machine learning: Hydrogen production from coke oven gas. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 69, 837–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Shen, Y.; Guan, Z.; Zhang, D.; Tang, Z.; Li, W. Multi-objective optimization of ANN-based PSA model for hydrogen purification from steam-methane reforming gas. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 11740–11755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Luo, H.; Tong, L.; Chen, B.; Cai, Y.; Yang, T.; Yuan, C.; Chahine, R.; Xiao, J. Multi-objective performance optimization of fuel cell grade hydrogen purification by multi-layered pressure swing adsorption systems with novel combination of adsorbents. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 376, 133996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahin Alipour Bonab, T.W.; Song, W.; Flynn, D.; Yazdani-Asrami, M. Machine learning-powered performance monitoring of proton exchange membrane water electrolyzers for enhancing green hydrogen production as a sustainable fuel for aviation industry. Energy. Rep. 2024, 12, 2270–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Dong, R.; Ia, H.; Peng, Z.; Liu, Z.; Wang, L.; Yi, L.; Xu, J.; In, H.; Chen, B.; et al. Interpretable machine learning for predicting and evaluating hydrogen production from supercritical water gasification of coal. Fuel 2026, 404, 136173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azadvar, S.; Tavakoli, O. Data-driven interpretation, comparison and optimization of hydrogen production from supercritical water gasification of biomass and polymer waste: Applying ensemble and differential evolution in machine learning algorithms. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 85, 511–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, M.I.; Farhan, M.; Rao, A.; Zhu, X.; Xiao, Q.; Salam, H.A.; Chen, T.; Li, X.; Ma, F. Hydrogen production enhancement using exhaust heat from HCNG engine: ASPEN plus simulation and machine learning prediction. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 278, 127340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escribano, R.A.N.G.; Schreiner, M.A.; de Oliveira, L.E.S.; Tamanho, G.; Ferreira, J.C.D.S.; Silva, I.C.D.; Ponciano, P.C.; Alves, H.J. A dataset for classifying operational states in dry reforming of biogas processes. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 158, 150314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ally, S.; Verstraeten, T.; Nowé, A.; Helsen, J. Day-ahead trading and power control for hybrid wind-hydrogen plants with multi-agent reinforcement learning. Appl. Energy 2025, 401, 126588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Liu, X. Incorporating advanced machine learning algorithms into off-grid hybrid renewable energy systems. Electr. Power. Syst. Res. 2025, 248, 111979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hydrogen Production Methods | Machine Learning Approaches | Inputs | Outputs | Model Performance | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methane Dry Reforming | Interpretable Machine Learning (IML), utilizing SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) and Partial Dependence Values (PDV) tools | Catalyst Parameters (Type of Promoter, Support Properties), Reaction Conditions (Temperature, Fuel-to-Oxidant Ratio, Space Velocity) | Methane Conversion Rate, Carbon Dioxide Conversion Rate, Hydrogen Production Rate, Carbon Deposition Amount | The model exhibits high prediction accuracy, with experimental validation showing an R2 value greater than 0.9 and a low RMSE | [36] |

| Methane Dry Reforming | An explainable CatBoost model, enhanced with interpretability tools, to improve transparency | Reaction temperature, gas hourly space velocity (GHSV), calcination temperature, nickel loading, and catalyst structural parameters | Methane Conversion Rate | The CatBoost model predicts the methane conversion rate with an R2 value of 0.91, and experimental validation shows an error of less than 10% | [37] |

| Catalytic Steam Reforming of Biomass Tar | Machine Learning Algorithms, Random Forest (RF), Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) for Optimizing Nickel-Based Catalysts | Reaction Temperature, Catalyst Support, Additive Type, Nickel Loading, Calcination Temperature | Toluene Conversion Rate | The RF model for predicting toluene conversion rate was evaluated with an accuracy of 0.99 and an AUC of 0.92 | [38] |

| Carbon Dioxide Methanation | Explainable Machine Learning (SHAP Analysis), XGBoost | Reaction temperature, nickel content, calcination temperature, particle size, reduction time | Carbon dioxide conversion rate, methane selectivity | The XGBoost model demonstrates high prediction accuracy, as verified through experimental validation | [39] |

| Dry Reforming of Methane (CO2 Methanation) | Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) and Nonlinear Autoregressive Exogenous (NARX) Neural Networks | Calcination temperature, reduction temperature, reaction temperature, reaction time, and Ni loading | Methane conversion rate, carbon dioxide conversion rate | The NARX neural network achieves the highest R2 = 0.998 and the lowest MSE = 3.24 × 10−9 | [40] |

| Sorption-Enhanced Chemical Looping Reforming | Artificial Neural Network | Operating Parameters (Temperature, Pressure, Flow Rate) and Catalyst/Adsorbent Properties | Methane Conversion Rate, Hydrogen Purity, and Carbon Dioxide Removal Efficiency | The ANN model demonstrates high prediction accuracy, R2 ≥ 0.9889 | [41] |

| Application Scenarios | Machine Learning Approaches | Inputs | Outputs | Model Performance | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steam Methane Reforming | Deep Neural Networks (DNN) Combined with Random Search Optimization Algorithm | Reactor length, feed flow rate, heat flux, S/C (steam-to-carbon ratio) | Hydrogen yield | The DNN model offers high prediction accuracy and the capability for multi-objective optimization | [28] |

| Methane Autothermal Reforming | Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) combined with Random Forest models and Q-learning algorithm | Oxygen-to-methane ratio, steam-to-methane ratio, temperature | Operating expenses (OPEX), carbon emissions per unit time, hydrogen yield | After DRL optimization, OPEX decreased by 10%, carbon footprint was significantly reduced compared to traditional processes, and hydrogen yield increased by 13% | [79] |

| Solar-driven Methanol Steam Reforming | Grey Relational Analysis (GRA) and Genetic Algorithm Optimized BP Neural Network (GA-BPNN) | Reaction temperature, methanol flow rate | Methanol conversion rate, hydrogen yield, carbon monoxide selectivity | The GA-BPNN model demonstrates high prediction accuracy, outperforming traditional prediction models | [84] |

| Fuel Cell and Ammonia-Hydrogen Internal Combustion Engine Hybrid System | Integrated Deep Learning (PCA, MCNN, SVM) | Voltage, current, temperature, pressure, fault signals | Fault diagnosis accuracy, system reliability | Overall diagnostic accuracy of 98.15%, with multi-system fault diagnosis at 96.67% | [85] |

| Biomass Gasification for Hydrogen Production | Gradient Boosting Regression Model combined with Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) | Biomass type, temperature, reaction time, biomass concentration, pressure, reactor type | Hydrogen yield | After PSO, the test R2 of the Gradient Boosting Regression (GBR) model is 0.958, and its cross-validation R2 is 0.917 | [86] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, X.; Lu, H.; Wang, Z. Machine Learning Applications in Fuel Reforming for Hydrogen Production in Marine Propulsion Systems. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2026, 14, 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010085

Chen Y, Liu X, Liu X, Lu H, Wang Z. Machine Learning Applications in Fuel Reforming for Hydrogen Production in Marine Propulsion Systems. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2026; 14(1):85. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010085

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Yexin, Xinyu Liu, Xu Liu, Hao Lu, and Ziqin Wang. 2026. "Machine Learning Applications in Fuel Reforming for Hydrogen Production in Marine Propulsion Systems" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 14, no. 1: 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010085

APA StyleChen, Y., Liu, X., Liu, X., Lu, H., & Wang, Z. (2026). Machine Learning Applications in Fuel Reforming for Hydrogen Production in Marine Propulsion Systems. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 14(1), 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010085