1. Introduction

Accurately identifying the incident wave direction is essential for ensuring the safe operation of ships [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. In general, ships are designed and operated to head into incoming waves, while encountering waves from the beam or following directions can lead to maneuvering instabilities such as surf-riding and broaching-to [

6]. These phenomena can amplify the ship’s roll motion, reduce its transverse stability, impair course-keeping ability, and ultimately increase the likelihood of capsizing or structural damage. Therefore, the incident wave direction is regarded as a critical parameter for securing both operational safety and intact stability of ships [

3,

4,

7,

8,

9].

For ships in operation, it is often difficult to directly measure external wave conditions due to various environmental and practical constraints. Radar-based wave direction sensors, for example, are limited in real-time applicability because of their high installation and maintenance costs, reduced sensor durability, and susceptibility to hull vibration and flow interference [

7]. Consequently, recent studies have focused on indirectly estimating wave directionality using motion responses measured by onboard sensors [

1,

3,

4]. This approach offers high practicality and scalability, as it enables the inference of sea states solely from the vessel’s intrinsic dynamic responses without relying on additional external measurement systems.

Iseki and Ohtsu (2000) derived directional wave spectra from ship motions using a Bayesian estimation framework [

10]. Tannuri et al. (2004) proposed an inverse estimation method based on a nonlinear least-squares approach, applied to the motion responses of ships under stationary conditions [

11]. Subsequent studies by Nielsen and his research group established a comprehensive framework for integrating the estimation of wave direction, period, and significant wave height, while also comparing the accuracy of various estimation techniques using measured data [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. In addition, Gorman (2018) presented a buoy-based wave spectrum estimation methodology, providing a benchmark for measurement-based model validation [

17].

Among time-domain approaches, Kalman filter–based methods have been extensively investigated. Komoriyama et al. (2025) applied a Kalman filter to achieve real-time estimation of wave profiles and ship responses under short-crested irregular wave conditions [

18]. Kim et al. (2019) also implemented a Kalman filter–based framework to reconstruct wave-induced responses of offshore structures in real time [

19]. More recent studies have extended this line of research by incorporating variations in ship forward speed, employing adaptive Kalman filters for improved inverse estimation performance [

20,

21].

More recently, probabilistic approaches have also been proposed. Park and Kim (2024) introduced a probabilistic framework for estimating directional wave spectra using onboard sensor measurements from ships [

22], while Son and Kim (2024) employed a B-spline–based interpolation method to enhance both the flexibility and accuracy of the underlying physical model [

23].

In recent years, research efforts grounded in physics-based estimation methods have increasingly expanded toward data-driven and physics–data hybrid approaches. Nielsen and his research group have explored the potential of machine learning–based wave estimation and its integration with conventional physics-based models. Using ship motion measurements, they conducted conditional estimation, uncertainty quantification, and composite sea-state prediction through machine learning techniques, thereby addressing several limitations inherent in traditional physics-driven frameworks. By incorporating information obtained from wave buoys and numerical simulations into the learning process, their approach enhanced model generalizability and demonstrated reliable directional wave estimation performance across a wide range of environmental conditions [

24,

25,

26].

Kwon and his research team developed a data-driven inverse estimation framework using motion response measurements from FPSOs and other floating structures, demonstrating its effectiveness for directional wave spectrum estimation under various sea states [

27,

28,

29]. Han et al. (2022) proposed a new estimation framework that accounts for nonlinear response characteristics [

30], while Ji et al. (2024) demonstrated through CFD analysis that the interaction between focusing waves and currents can induce strongly nonlinear hydrodynamic loads on marine structures, and highlighted that such nonlinear effects may increase the uncertainty of inverse estimation and model-based analyses [

31]. Li et al. (2024) integrated physical constraints into a machine learning–based model to enhance its physical consistency [

32]. Bisinotto et al. (2024) introduced a complementary learning architecture that combines numerical simulation results with field measurements, thereby improving estimation accuracy in complex ocean environments [

33]. Ko et al. (2024) proposed a two-step, dimension-reduction-based framework for directional wave estimation under forward speed conditions, improving the robustness and computational efficiency of data driven inference [

34]. In addition, Lee et al. (2023) demonstrated that ship motions induced by waves can be accurately predicted by employing a physics informed neural network architecture that integrates spatiotemporal wave field information with ship motion histories [

35]. Collectively, these studies emphasize the central role of measurement-based data in achieving reliable wave estimation and illustrate a progressive shift toward integrating data-driven learning with the underlying principles of physics-based modeling.

This research trend has evolved beyond simple input–output mapping toward establishing structured linkages between data-driven models and physical interpretations. Such developments highlight the potential for practical applications, including real-time sea-state awareness for autonomous ships, early warning systems, and route optimization in future maritime operations.

Within this research trend, ensuring the reliability of machine learning-based estimation requires that the training data be constructed in a physically consistent and analysis-based manner. In particular, a quantitative understanding of ship motion responses to waves necessitates the use of Response Amplitude Operators (RAOs), computed from linear potential flow theory, and the corresponding response spectra obtained by combining these RAOs with a wave spectrum. In this study, RAOs were computed for various wave conditions, and they were subsequently coupled with wave spectra to construct a comprehensive response spectrum database for model training. Because the motion responses of ships in actual forward speed conditions are measured in the encounter-frequency domain, a basic frequency conversion procedure was applied to ensure the physical consistency of the data. This process serves not as a core methodological contribution but rather as a preprocessing step to ensure that the training data accurately reflect real measurement environments.

Building on this physical background, the present study proposes an Artificial Neural Network (ANN)–based methodology for classifying the incident wave direction using Heave–Roll–Pitch response spectra measured during ship navigation. The proposed framework utilizes motion response spectra generated through the combination of RAOs and wave spectra, where the frequency-domain characteristics of Heave, Roll, and Pitch motions are concatenated into a unified input vector for ANN training. Bayesian optimization was employed for hyperparameter tuning to enhance both training efficiency and classification accuracy.

This study distinguishes itself from existing research by aligning numerically generated data with the physical characteristics of actual onboard measurements and by establishing a framework capable of classifying incident wave direction using only motion sensor data. The proposed approach has potential applications in wave direction awareness modules for autonomous ships, real-time wave monitoring systems, route optimization, and early warning systems, and it offers promising extensibility toward digital twin–based maritime safety assessment and decision-support technologies.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Ship Motion and Response Spectra

Although ship responses to waves arise from complex nonlinear fluid–structure interactions, they can be reasonably approximated using frequency-domain analysis based on linear potential flow theory within moderate wave height and frequency ranges. In this framework, ship motions are described by a frequency-dependent equilibrium between wave-induced excitation forces and hydrodynamic added effects, and the response of each motion component is represented by a frequency-dependent transfer function, known as the response amplitude operator (RAO). The RAO varies with the ship’s geometry, draft, and wave heading angle, and serves as a fundamental physical quantity that determines the spectral distribution of ship motions in waves. These response characteristics can be derived from the frequency-domain equilibrium between the external forces and hydrodynamic effects acting on the hull, which is expressed in Equation (1).

Here, denotes the mass of the vessel, while and represent the added mass and hydrodynamic damping, respectively. The term is the hydrostatic restoring coefficient. On the right-hand side, denotes the wave-induced excitation force composed of the Froude–Krylov and diffraction components. Equation (1) defines the equilibrium between the ship motion and the external excitation at each frequency component, and its frequency-by-frequency solution yields the transfer function that characterizes the vessel’s response to incident waves.

When Equation (1) is transformed into the complex-valued frequency domain, the steady-state response of the vessel can be expressed as Equation (2).

In Equation (2), denotes the amplitude of a single incident wave, and represents the linear transfer function (LTF), whose amplitude corresponds to the RAO. The transfer function is expressed in complex form, containing both magnitude and phase information, and its value varies with the wave frequency and incident heading angle.

The response amplitude for a specific motion component

is defined as Equation (3).

Therefore, the RAO is a function that represents the response amplitude of each motion component when a unit-amplitude regular wave is incident, and it exhibits inherent frequency–direction dependence determined by the ship’s geometry, forward speed, and wave heading angle. The distribution of the RAO serves as a key factor governing the magnitude and phase characteristics of the motion response under varying wave conditions.

Meanwhile, the energy density of a single incident wave is defined as Equation (4).

Here,

denotes the energy spectrum of the incident wave, representing the relationship between its amplitude and frequency components. Using this definition, the response spectrum for a specific motion component

can be calculated as Equation (5).

Equation (5) indicates that the energy spectrum of the incident wave is transformed by the squared magnitude of the RAO. This relationship enables a quantitative interpretation of the frequency-dependent distribution of motion energy under given wave conditions, providing fundamental data for analyzing a vessel’s motion stability, intact stability, and direction-dependent response characteristics.

2.2. Directional Wave Spectrum Respresentation

In realistic sea conditions, waves do not propagate with a single frequency or in a single direction; instead, multiple frequency and directional components coexist simultaneously. Therefore, a realistic description of the wave energy distribution must account for variations not only in frequency but also in direction. Such a two-dimensional distribution of wave energy is expressed by the directional wave spectrum, which is defined as Equation (6).

Here, represents the wave spectrum under the assumption of a single propagation direction, and denotes the directional spreading function.

Under fully developed wind-sea conditions, the distribution of wave energy can be approximated by the Pierson–Moskowitz (PM) spectrum. Although this spectrum is originally defined in terms of wind speed, a more practical formulation for real sea conditions is to use the observed significant wave height and mean period directly. In such cases, the wave spectrum is expressed using the modified Pierson–Moskowitz (Modified PM) spectrum, which is given as Equation (7).

Here, denotes the significant wave height, and represents the mean zero-up-crossing period.

A wave spectrum defined for a single direction generally assumes a long-crested wave, in which wave energy is concentrated around one predominant incident angle. However, waves observed in actual sea states exhibit a short-crested pattern, where multiple directional components coexist simultaneously. Therefore, to extend a single-direction spectrum into a realistic multidirectional wave spectrum, a spreading function is required to describe how the wave energy is distributed over different directions. This function converts a long-crested wave into a short-crested wave and serves as a key component for reproducing the directional spreading characteristics of real sea conditions. The directional spreading function must satisfy the overall energy conservation condition, and it is expressed as Equation (8).

Among the representative empirical formulations for the directional spreading function, the normalized cosine–2s model is widely used, and it is defined as Equation (9).

Here, denotes the mean wave direction, is the directional spreading parameter, and represents the gamma function. This model satisfies the condition given in Equation (8), and as the value of increases, the wave energy becomes more concentrated around the mean wave direction. Conversely, when , the energy is uniformly distributed over all directions, corresponding to a non-directional wave.

Such a directional spreading function serves to partition the energy of each frequency component across different directions, thereby enabling the representation of the directional wave spectrum.

2.3. Relationship Between Absolute and Encounter Frequencies

The motion responses of a ship in forward navigation can be described in terms of two different frequency reference frames: the absolute frequency and the encounter frequency. The absolute frequency is defined in a fixed, non-moving coordinate system and is used as the reference frequency for RAOs computed from linear potential flow analysis. In contrast, the frequency experienced by a ship encountering waves during actual navigation is the encounter frequency, and all measured response data are obtained in this encounter-frequency domain. Therefore, to ensure consistency between numerical analysis results and measured onboard data, the transformation between these two frequency domains must be clearly defined [

9,

12]. This relationship is generally expressed as Equation (10), considering the ship’s forward speed

, wave heading angle

, and gravitational acceleration

.

This equation represents the Doppler effect arising from the relative motion between the wave propagation direction and the ship’s heading, and the characteristics of the frequency transformation vary depending on the incident angle . This is because the ship’s forward speed combines with the phase speed of the waves, resulting in different relative velocity components between the wave propagation direction and the ship’s direction of travel.

First, under head-sea conditions (), the ship advances directly into the direction of wave propagation, resulting in the maximum relative velocity between the vessel and the waves. In this case, the ship encounters a greater number of wave cycles within the same time interval, and therefore the encounter frequency becomes higher than the absolute frequency. In other words, as the absolute frequency increases, the encounter frequency increases monotonically, and a one-to-one correspondence exists between the two frequency domains. Owing to this characteristic, the transformation between absolute and encounter frequencies can be applied directly for each frequency component under head-sea conditions.

Under beam-sea conditions (), the direction of wave propagation is perpendicular to the ship’s heading, and thus the forward speed component does not affect the phase speed of the waves. As a result, the encounter frequency remains identical to the absolute frequency, and no frequency transformation is required. In this condition, the absolute frequency domain used in numerical analysis can be directly compared with the encounter frequency domain in which measured responses are obtained.

In contrast, under following-sea conditions (), the waves propagate in the same direction as the ship’s heading. In this case, the forward speed does not add to the wave phase speed but instead produces a subtractive effect. As a result, the ship encounters wave crests more slowly, and the encounter frequency becomes lower than the absolute frequency. When the ship’s forward speed exceeds a certain threshold, a range of relative velocities approaching zero emerges, causing the relationship between the absolute and encounter frequencies to lose monotonicity. In other words, a non-monotonic multi-mapping phenomenon (1:3 mapping) occurs, where multiple absolute frequencies correspond to a single encounter frequency.

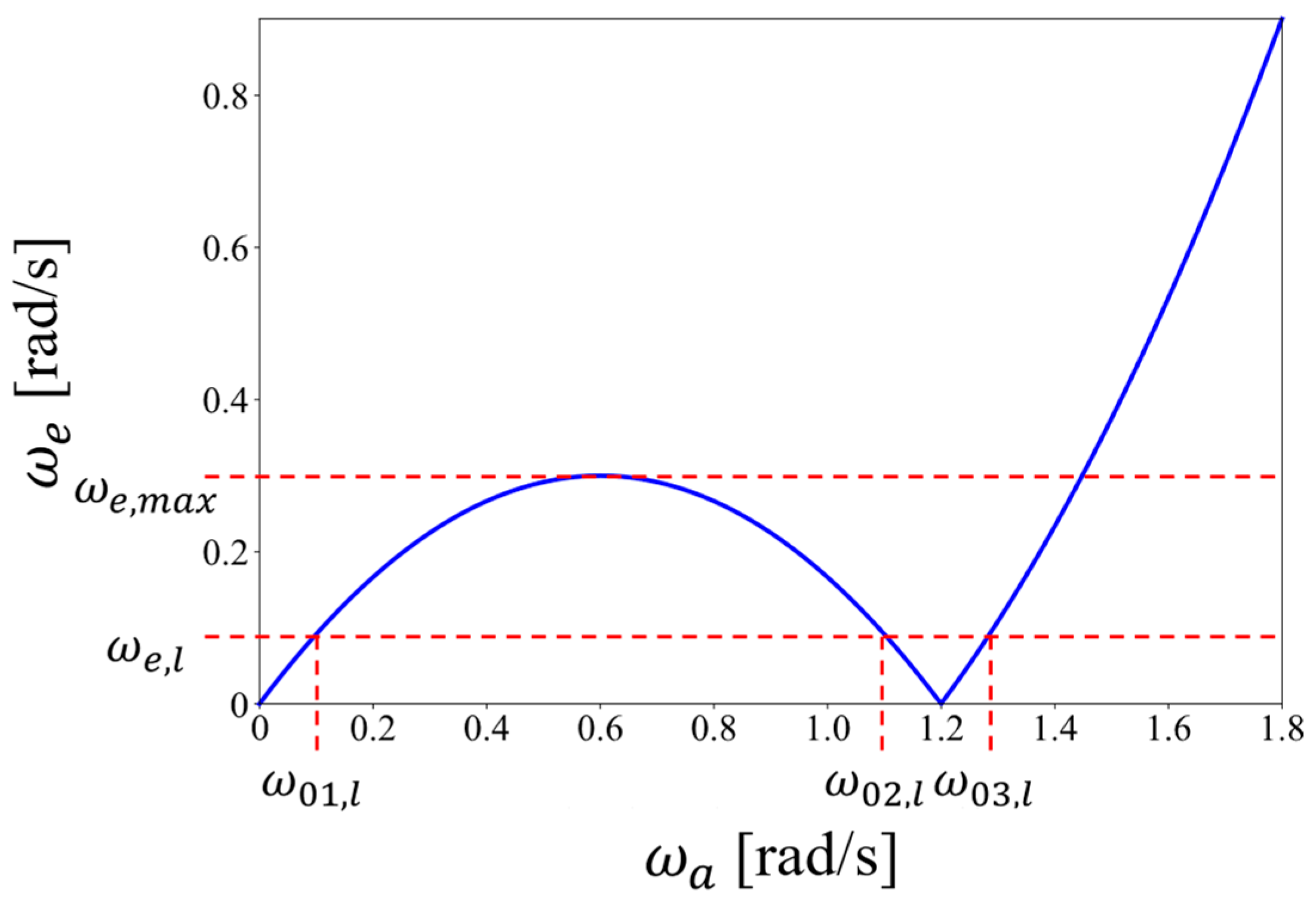

Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between the absolute frequency

and the encounter frequency

under following-sea conditions. As shown in the graph, the encounter frequency exhibits a non-monotonic pattern over a certain interval, and multiple absolute frequencies correspond to a single encounter frequency. In such cases, the spectral transformation in the encounter frequency domain cannot be performed through simple substitution; instead, interpolation is required to distribute the contribution of each absolute frequency component appropriately. This procedure ensures energy conservation within the non-monotonic region and minimizes distortion arising from the frequency-domain transformation.

To quantitatively describe this relationship, the condition of energy conservation between the absolute and encounter frequencies must be taken into account. Since the energy density of the response spectrum

must remain invariant regardless of the chosen frequency domain, the relationship given in Equation (11) holds.

Equation (11) indicates that, when transforming from the absolute to the encounter frequency, the energy correction term

associated with the rate of change in the absolute frequency must be taken into account. However, as mentioned earlier, this relationship loses monotonicity under following-sea conditions, and the simple substitution form of Equation (11) is no longer sufficient to ensure energy conservation. Therefore, the spectrum must be transformed by summing the contributions of all corresponding absolute frequency components, and its general form is defined as Equation (12).

Here, denotes the number of absolute frequency components corresponding to a given encounter frequency, which is three under following-sea conditions. Equation (11) ensures that the spectral energy in the absolute frequency domain is preserved in the encounter-frequency domain, while minimizing potential spectral distortion that may arise within the non-monotonic region.

When the encounter frequency falls within the non-monotonic region, multiple absolute frequencies correspond to a single encounter frequency. In this case, the encounter-domain spectrum

must be computed by incorporating the contributions of all associated absolute frequency components. However, the values of

vary depending on the ship’s forward speed

and wave heading angle

, and the absolute frequency grid is generally non-uniform; thus, direct substitution on a fixed frequency grid is not feasible. Therefore, interpolation is essential when transforming the spectrum from the absolute to the encounter domain in order to account for the non-uniform frequency spacing. In particular, within the non-monotonic region, a single

corresponds to three different

values and applying a simple one-to-one substitution would break the continuity of the energy density and produce distortion. To address this issue, interpolation is performed using the relative spacing between the absolute frequency components as weighting factors, and the resulting expression is given as Equation (13).

Here,

and

represent the relative position of the encounter frequency

between the two adjacent absolute frequencies

and

, while the term

applied to each component serves as the energy correction factor associated with the frequency-axis transformation.

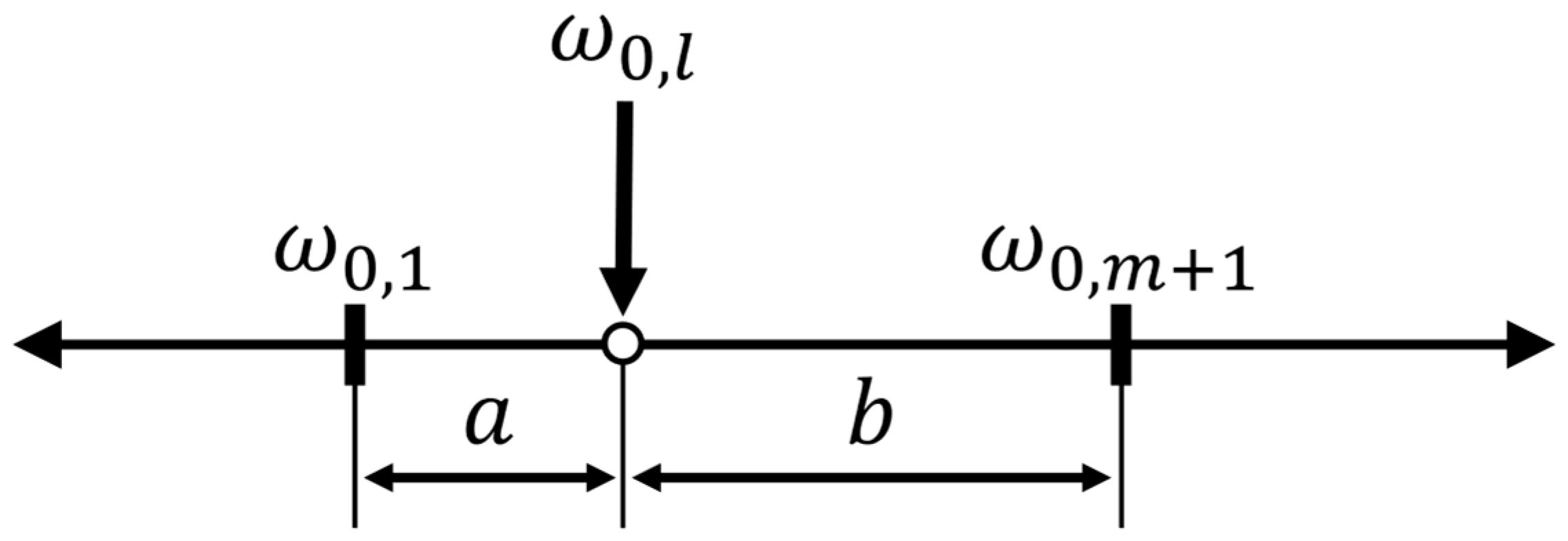

Figure 2 illustrates this interpolation concept, showing the procedure for determining the encounter frequency location on a non-uniform absolute frequency grid and obtaining a continuous spectral value.

3. Methodology

3.1. Overview of the Framework

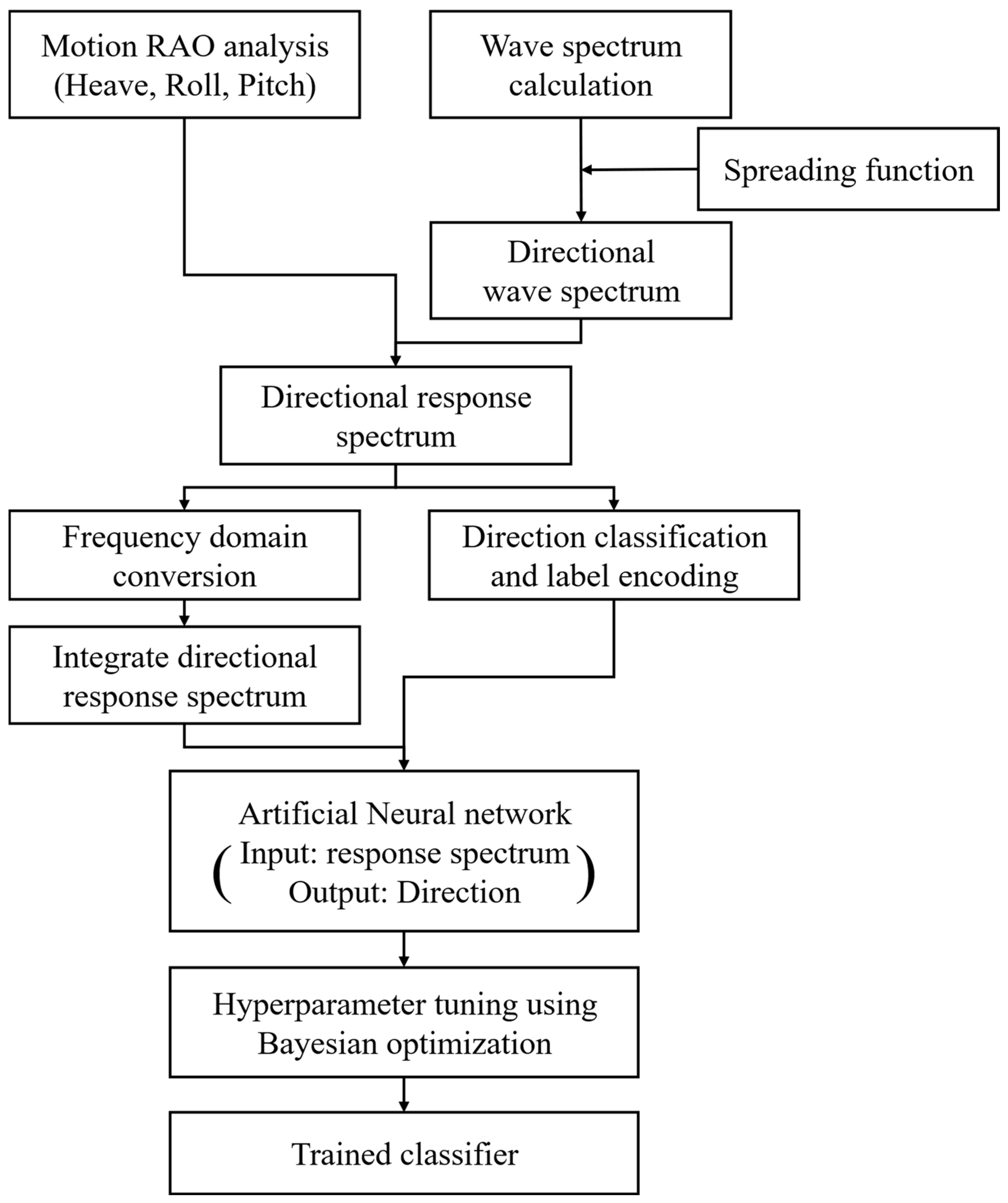

The objective of this study is to establish an artificial neural network–based methodology that classifies the predominant wave heading direction acting on a ship in navigation using motion response spectra as input. The overall procedure of the proposed framework is summarized in

Figure 3 and consists of three main stages.

The first stage is the hydrodynamic analysis and database construction. In this stage, the hydrodynamic characteristics of the ship under wave excitation are computed by considering the principal properties of the vessel. Based on linear potential flow theory, RAOs for the heave, roll, and pitch motion components are obtained, and their frequency- and direction-dependent response characteristics are quantified. Meanwhile, the frequency-dependent energy distribution of waves is defined by the wave spectrum, which is extended to a directional wave spectrum by applying a spreading function to account for wave directionality. This allows the reproduction of realistic sea states by incorporating multidirectional components representative of short-crested waves. By combining the directional wave spectrum with the RAOs, a directional response spectrum is constructed, representing the distribution of motion energy over frequency and direction. This dataset is then organized into a database and used as the training input for the subsequent stages.

The second stage is the data preprocessing stage. The hydrodynamic database constructed in the previous step consists of response spectra computed over various frequency and directional conditions, and this information must be transformed into a format suitable for machine learning training. In this stage, the original data calculated in the absolute frequency domain are converted into the encounter frequency domain to reflect the effects of the ship’s forward speed and the incident wave direction under actual operating conditions. Directional response information is then arranged into frequency-vector form, while the corresponding incident wave directions are converted into integer labels through a label-encoding scheme. Through this process, a well-defined input–output dataset is constructed, establishing the explicit relationship between wave conditions and motion responses, which subsequently serves as the training dataset for the neural network.

The third stage involves neural network training and model optimization. Using the preprocessed response spectrum data as input, an artificial neural network is trained to classify the incident wave direction. The network architecture is based on a multilayer perceptron: the input layer receives the motion response data constructed in the frequency domain, the hidden layers extract key features through nonlinear activation functions, and the output layer performs classification according to the predefined labeling scheme for each incident wave direction. As the choice of hyperparameters greatly affects model performance, Bayesian optimization is employed to efficiently search for optimal hyperparameter combinations. This method automatically identifies the best set of hyperparameters for the given training dataset and improves both classification accuracy and training efficiency through iterative search.

Finally, the trained neural network–based classification model can reliably estimate and classify the predominant incident wave direction by using the ship’s motion response spectra as input across a wide range of sea states and operating speeds.

3.2. Construction of the Motion Response Spectra Dataset

The motion response spectrum dataset was constructed by combining the hydrodynamic response characteristics of the ship with various wave conditions. The target vessel analyzed in this study is a 174K-class LNG carrier. The selected hull form represents one of the most widely operated large commercial ship types in the current merchant fleet and was adopted as a representative example to examine the conceptual feasibility of the proposed approach. The objective of this study is not to develop a model tailored to a specific hull type, but rather to demonstrate the viability of a motion response spectrum-based wave direction classification procedure. Therefore, the same methodology can be applied to other ship types, such as container ships or bulk carriers, provided that RAO-based training data can be generated in a similar manner. The dataset used in this study does not consist of actual onboard measurements; instead, pseudo-measurement data were numerically synthesized by combining potential flow based RAOs with directional wave spectra, serving as a numerical dataset for concept-level methodological validation. The principal particulars of the target vessel are presented in

Table 1.

Based on the target vessel, linear potential flow analysis was performed to compute the RAOs for various frequencies and wave heading angles. The linear potential flow analysis was performed using the commercial software ANSYS AQWA-13.0.

The wave conditions were defined within the ranges summarized in

Table 2, with a significant wave height

of 1–7 m, a mean zero-up-crossing period

of 3–9 s, and incident wave directions

from 0° to 330° at 30° intervals. By combining these parameters, various sea states were simulated, and for each case, the motion response spectrum was computed by coupling the wave spectrum with the RAOs.

The frequency-dependent wave energy distribution was defined using the Modified Pierson–Moskowitz spectrum, and a directional spreading function was applied to extend it into a directional wave spectrum. This approach enabled the reproduction of short-crested wave conditions with multidirectional components, allowing the ship’s motion response characteristics to be evaluated under more realistic sea states. In this process, the response spectrum for each incident wave direction was constructed in the form of a one-dimensional vector representing the frequency-dependent energy distribution.

Finally, for each wave condition, the directional response spectrum was computed by combining the RAOs with the directional wave spectrum. The response spectra were then transformed from the absolute frequency domain to the encounter frequency domain to account for the frequency shifts induced by the ship’s forward speed and the incident wave angle. The resulting data were organized into a motion response spectrum database containing frequency–direction–motion components, which was subsequently processed and used as the input dataset for the neural network training stage.

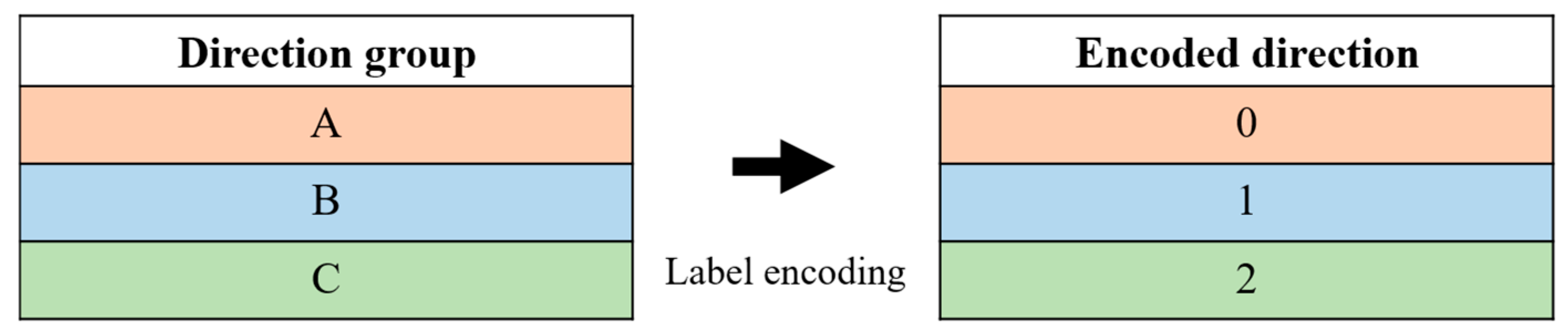

3.3. Label Encoding and Direction Classification Scheme

The incident wave direction is a categorical variable defined with respect to the ship’s heading, and it must be converted into numerical form for neural network training. For this purpose, a label-encoding scheme was applied to transform each directional category into an integer label.

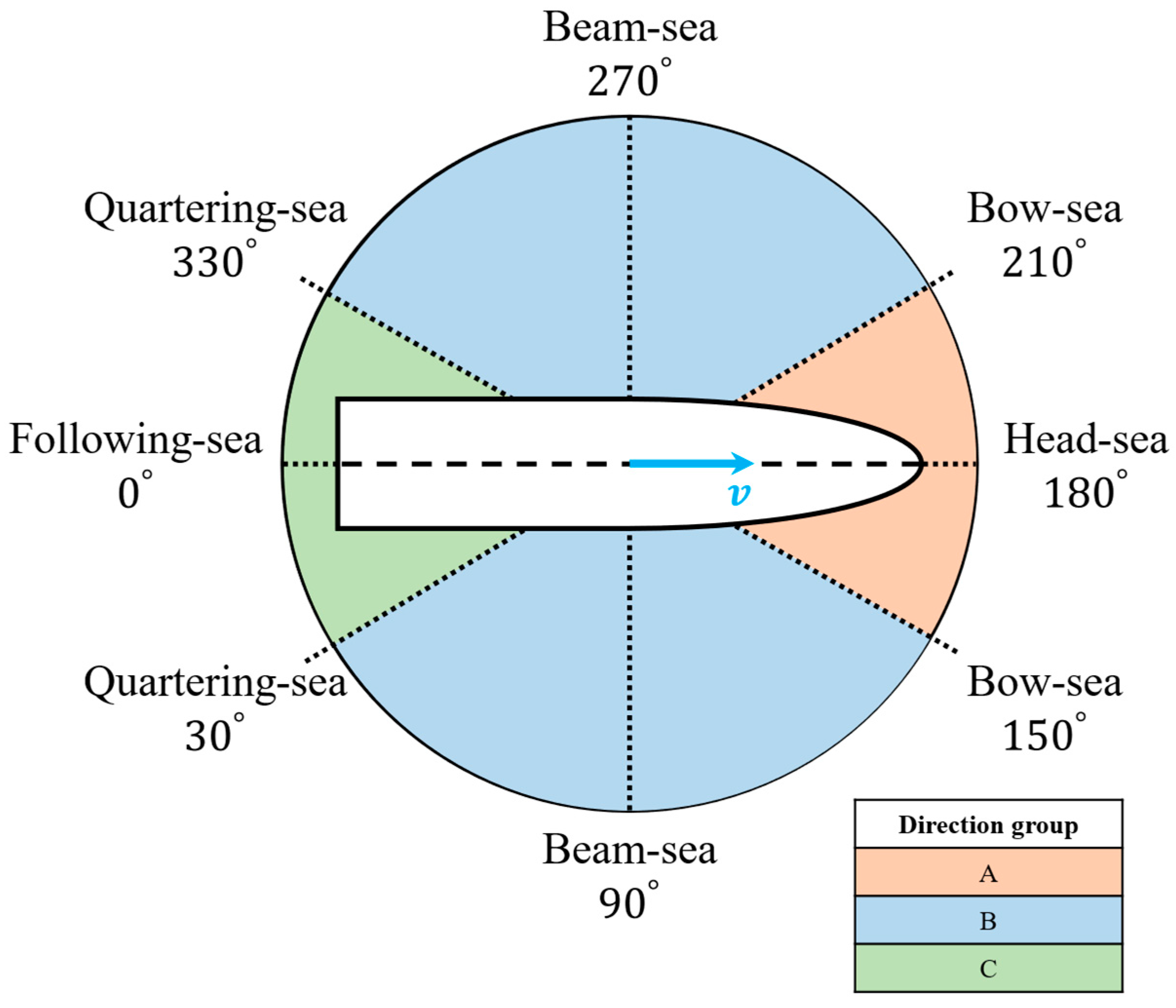

The definition of the incident wave direction is traditionally based on the ship’s heading, and the same criterion was applied in this study.

Figure 4 illustrates the wave direction classification scheme used herein. The forward direction of the ship (180°) is defined as head-sea, whereas the aft direction (0°) corresponds to following-sea. According to conventional directional categories, bow-sea refers to the range of ±30° around the head-sea direction (150°–210°), quartering-sea corresponds to the ±30° range around the following-sea direction (330°–30°), and the lateral directions at 90° and 270° are classified as beam-sea. These directional regions are visually represented in

Figure 4, with distinct colors assigned to each category.

In this study, the traditional wave direction classification shown in

Figure 4 was reorganized into three direction groups to improve classification efficiency for the neural network and to reflect similarities in response patterns. Group A encompasses the full range of directions corresponding to bow-sea conditions centered around the head-sea direction and is indicated by the red region in

Figure 4. This group represents wave headings toward the bow, where the ship’s motion responses exhibit high sensitivity to changes in incident wave direction.

In contrast, Group C includes the directional range corresponding to quartering-sea conditions centered around the following-sea direction and is shown as the green region in

Figure 4. This group represents wave headings approaching from the stern, where variations in the response spectrum tend to be relatively moderate.

Group B corresponds to the broad intermediate region shown in blue in

Figure 4, which encompasses the directional ranges extending on both sides of the two beam-sea headings (90° and 270°). Specifically, around the 90° beam direction, the group includes the sectors spreading toward the bow-side directions (from 90° toward 150°) as well as toward the quartering-side directions (from 90° toward 30°). A similar pattern applies to the 270° beam direction, where the sectors extending toward the bow-side directions (from 270° toward 210°) and toward the quartering-side directions (from 270° toward 330°) are included. Together, these beam-centered and symmetrically expanding directional intervals constitute Group B, reflecting its rotationally symmetric characteristics.

From a practical standpoint, maritime decision-making rarely requires fine grained directional resolution. Operational guidelines, risk assessment procedures, and autonomous ship situational-awareness modules commonly rely on coarse directional categories such as head-, beam-, and following-sea. Therefore, grouping wave directions into three physically meaningful sectors is sufficient to preserve the essential dynamic characteristics required in real-world applications.

As shown in

Figure 5, the three direction groups were converted into a format suitable for processing by the neural network using a label-encoding scheme. Since Group A, Group B, and Group C each correspond to a distinct categorical class, they were replaced with integer values for use in the model. Group A was assigned the integer value 0, Group B was assigned 1, and Group C was assigned 2.

The encoded integer labels correspond directly to the output nodes of the neural network, enabling the model to clearly distinguish among the three direction groups during training. With this structure, the wave direction information is handled in the output layer as a multi-class classification problem. Accordingly, the training dataset constructed in this study uses one-dimensional motion response spectra as the input variables and the label-encoded wave directions as the output variables. This input–output structure allows the neural network to effectively learn the relationship between the frequency-domain motion response characteristics and the incident wave direction.

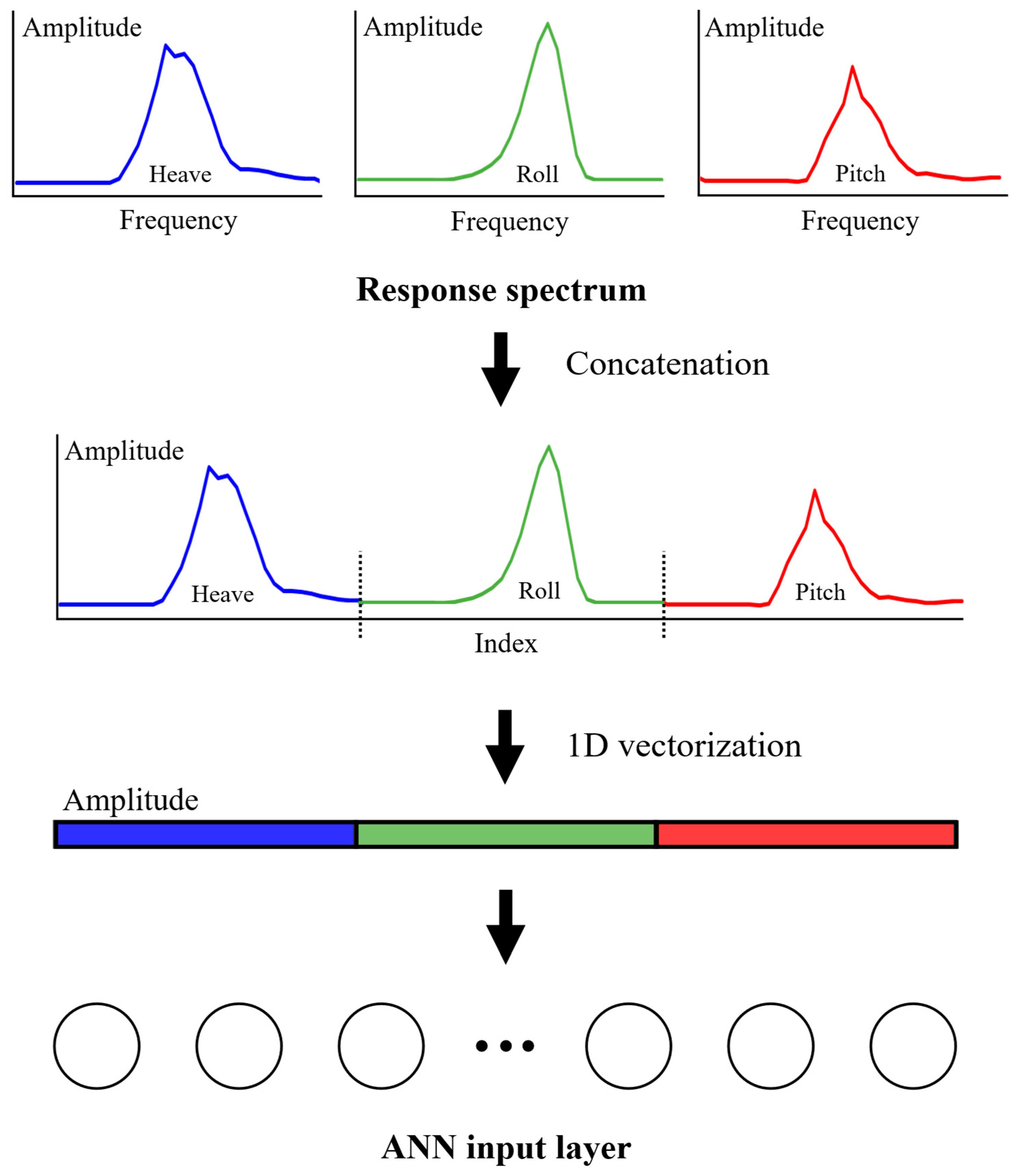

3.4. Neural Network Architecture and Training Precedure

To classify the incident wave direction from the motion response spectra of a ship in navigation, a multilayer perceptron–based artificial neural network was constructed using the combined response spectrum as the input. The overall architecture is presented in

Figure 6 and consists of three main components: an input layer, multiple hidden layers, and an output layer.

The input data are based on the response spectra computed for the heave, roll, and pitch motion components. These three motion components exhibit clearly distinguishable changes in peak location and energy distribution in their response spectra as the incident wave direction varies, and they also have the advantage of being reliably measured by standard onboard monitoring systems. In contrast, the horizontal motions, surge, sway, and yaw, show relatively weak directional dependence or lack sufficiently distinct wave-induced characteristics, and were therefore excluded from the input features of the wave direction classification model.

Based on this selection, each motion component is represented as a one-dimensional vector corresponding to its frequency dependent response amplitude, and the three vectors are concatenated sequentially to form a unified input vector. This combined response spectrum inherently captures the interdependence among the different motion components and provides a rich representation of the variations in frequency–response patterns according to wave direction.

Figure 7 illustrates an example of the combined response spectrum used in this study, showing how the individual response spectra computed for the heave, roll, and pitch motions are sequentially arranged along the frequency axis to form a single input vector. The heave component generally exhibits larger response amplitudes than the other motion components, while the roll and pitch spectra display more pronounced variations in shape depending on the wave heading direction. These characteristics are directly embedded into the combined input vector and contribute to the neural network’s ability to learn the features necessary for wave direction classification. The number of neurons in the input layer corresponds to the total length of the concatenated frequency ranges of the three components, with each node representing the response amplitude at a specific frequency.

The structure of the hidden layers and the training settings were determined using Bayesian optimization. This method efficiently searches for the optimal solution by estimating the behavior of the objective function through a probabilistic surrogate model, rather than repeatedly evaluating the computationally expensive objective function directly [

3,

36,

37]. Bayesian optimization generally consists of three main steps.

First, the objective function

is approximated by a Gaussian process (GP) over the hyperparameter space. The GP is defined using a mean function

and a covariance function

, as expressed in Equation (14), which enables the probabilistic estimation of function values in regions where no observations are available.

Next, an acquisition function

is defined to determine the next candidate point to be evaluated. In this study, the Expected Improvement (EI) function, one of the most widely used acquisition functions, was adopted. This function prioritizes regions with a high probability of yielding performance improvement. The EI function is defined as Equation (15).

Here,

denotes the best performance value observed so far. Using the predictive mean

and standard deviation

of the Gaussian process, the EI can be expressed in a closed form, as shown in Equation (16).

and represent the cumulative distribution function and the probability density function of the standard normal distribution, respectively. This acquisition function guides the search efficiently by balancing exploration and exploitation, directing the optimization process toward regions where performance improvement is expected.

The hyperparameter search was conducted within a predefined search space designed to ensure sufficient flexibility in the model architecture while avoiding unnecessary increases in computational cost. Specifically, the number of hidden layers was explored within the range of 1–6, the number of nodes per layer within 4–500, and the number of training epochs within 10–1000. These ranges were chosen to allow the search to span from lightweight models to moderately deep architectures, while preventing excessive model sizes that could lead to overfitting and increased computational burden.

During the optimization process, 20% of the training data was used as a validation set, and the validation loss was defined as the objective function. As Bayesian optimization progressed, the Expected Improvement (EI) value gradually stabilized, and in the later iterations the validation loss showed no further improvement. In this study, this behavior was interpreted as an indication of convergence.

Finally, in the optimization stage, the point that maximizes the acquisition function is selected as the next candidate, and the model is updated based on the evaluation of the objective function at this point. In this study, the number of hidden layers, the number of nodes per layer, and the number of epochs were defined as the hyperparameters to be explored, while the ReLU activation function and the Adam optimizer were used. The hyperparameters determined through Bayesian optimization are summarized in

Table 3.

The output layer is configured to predict the integer labels 0, 1, and 2, which represent the incident wave directions, and therefore consists of three output nodes corresponding to these labels. To maintain a regression-based multi-output structure, no nonlinear activation function was applied to the output layer; instead, a linear output was used. With this configuration, the label-encoded direction groups (A = 0, B = 1, C = 2) are first predicted as continuous numerical values, and the final classification is obtained by mapping the model output to the closest integer label.

The three wave direction groups considered in this study are not simple categorical labels; rather, they represent ordinal variables obtained by partitioning the continuous wave direction (0–360°) into intervals. In real sea conditions, wave direction typically evolves gradually rather than abruptly, meaning that the groups should be interpreted as segmentations of a continuous physical quantity rather than mutually independent categories. Given this characteristic, a traditional multi-class classification framework using a Softmax output is limited, as it treats classes as independent and does not account for the inherent ordering or relative proximity among groups.

To address this issue, a regression-based output structure was adopted, in which no nonlinear activation function is applied to the output layer. This design enables the model to learn the continuous relationships between the encoded labels (0, 1, 2), and the final prediction is obtained by mapping the continuous output to the nearest integer label. This approach reduces discontinuous errors at class boundaries and provides smoother predictions in transitional directional ranges, thereby offering a more physically consistent representation of the underlying wave direction characteristics.

Finally, for model training, the entire dataset was divided into training, validation, and test sets in an 80%, 10%, 10% ratio. The training set was used to update the neural network parameters, while the validation set was employed to prevent overfitting and monitor the learning process. The test set was kept separate for final performance evaluation to assess the model’s generalization capability.

4. Results

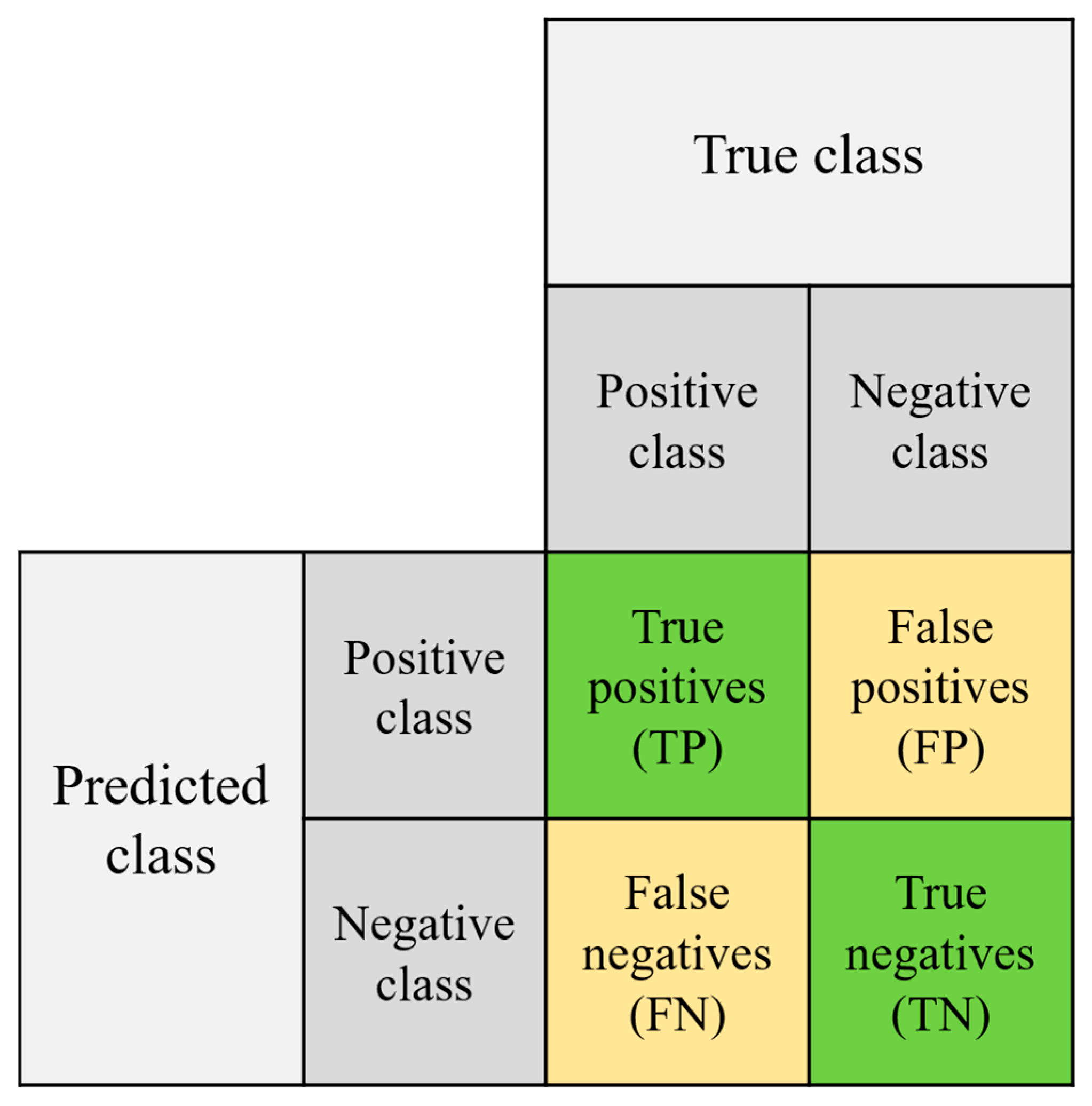

To quantitatively evaluate the performance of the trained neural network model, this study employed a confusion matrix and several representative classification metrics derived from it.

Figure 8 illustrates the structure of the confusion matrix, which presents the correspondence between the predicted classes and the true classes in a two-dimensional matrix form. This allows intuitive assessment of which classes were correctly identified and which were misclassified by the model.

The confusion matrix consists of four primary components. First, the true positive (TP) represents the cases in which the model correctly predicts a sample as belonging to the positive class when it indeed belongs to that class. The false positive (FP) corresponds to instances in which the model incorrectly classifies a sample as positive despite it actually belonging to the negative class. From a statistical perspective, an FP outcome corresponds to a type I error, indicating that the model has falsely detected an event that does not exist.

Conversely, a false negative (FN) occurs when the model incorrectly predicts a sample as negative despite it actually belonging to the positive class. This corresponds to a type II error, indicating that the model has failed to detect an event that has indeed occurred. Finally, a true negative (TN) represents the case in which a sample genuinely belongs to the negative class and the model correctly classifies it as such.

In

Figure 8, the green regions correspond to correct classifications (TP and TN), whereas the yellow regions indicate misclassifications (FP and FN). Using these four components, the primary performance metrics of the model can be computed, and each metric is defined as follows.

In this study, the overall classification performance of the model was evaluated using accuracy, while the class-wise performance for each wave direction category was examined through precision, recall, and F1-score. Accuracy represents the proportion of samples correctly classified among all data and serves as a general indicator of the model’s classification capability. It is computed as the ratio of the diagonal elements of the confusion matrix (TP and TN) to the total number of samples and is used to assess the overall consistency of the model’s predictions.

Precision represents the proportion of samples that truly belong to a given class among those classified as that class by the model and thus indicates the reliability of the classification. Recall denotes the proportion of samples that the model correctly identifies among all samples that actually belong to the class, reflecting the model’s sensitivity. Finally, the F1-score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, representing the balance between these two performance measures. Since there is generally a trade-off between precision and recall, the F1-score serves as a representative metric that evaluates the overall balance between them.

By considering these statistical metrics, it becomes possible to quantify not only the overall accuracy but also the tendencies related to type I and type II errors. For example, a low precision indicates a high proportion of type I errors, suggesting that the model tends to falsely detect wave directions that are not actually present. Conversely, a low recall implies a high occurrence of type II errors, meaning that the model fails to identify wave directions that do exist. Therefore, even if the overall accuracy is high, an unbalanced reduction in either precision or recall may diminish the reliability of predictions for specific directional conditions. In this manner, multi-metric evaluation based on the confusion matrix enables a systematic and quantitative assessment of the model’s classification characteristics.

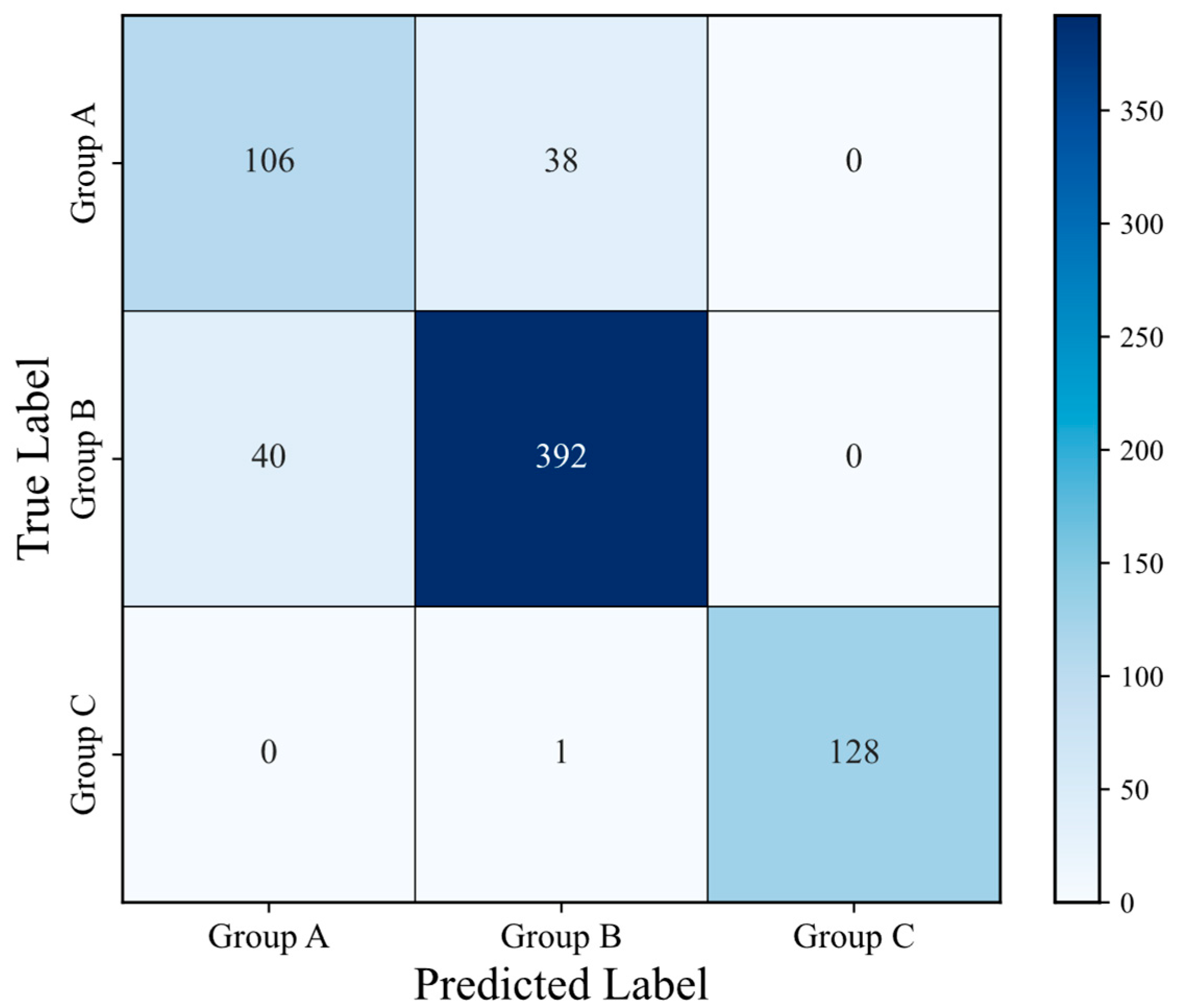

Figure 9 presents the confusion matrix for the classification results of the three wave direction groups. Overall, the model demonstrates stable performance across all classes. In particular, Group B achieved the highest accuracy, correctly predicting 392 out of 433 samples. Group C also exhibited excellent performance, with 128 correct predictions and only one misclassification. In contrast, Group A showed a relatively higher level of confusion with Group B, with 38 samples misclassified as belonging to Group B. This result suggests that while the model effectively captures the spectral characteristics associated with beam and following–quartering conditions, the boundary between classes becomes less distinct in head–bow conditions due to the inherent similarity in their frequency-response structures.

Table 4 summarizes the confusion matrix results and the main classification metrics for the three wave direction classes (Group A, Group B, and Group C). The overall accuracy was 0.888, indicating that the model correctly classified approximately 88.8% of all samples. Examining the class-wise performance, Group C exhibited the highest F1-score, and Group B also showed consistently high precision and recall. In contrast, Group A demonstrated relatively lower classification accuracy compared with the other two groups.

Table 5 presents the statistical indicators summarizing the overall classification performance of the neural network model. The macro average represents the arithmetic mean of the performance metrics across all classes, assigning equal weight to each class and thereby reflecting the balance of class-wise performance. In contrast, the weighted average is computed by weighting each class according to its support (number of samples), providing a comprehensive measure that accounts for the actual data distribution. These two metrics are defined in Equations (21) and (22).

Here, denotes the evaluation metric (precision, recall, or F1-score) for class , and represents the support of the corresponding class.

Due to the nature of the wave direction classification problem, the numbers of observed samples differ among the three direction groups A, B, and C. In particular, the beam-direction range is relatively broad, leading to a concentration of data in this region; thus, relying solely on the unweighted average would not provide an objective assessment of the model’s overall performance. To address this limitation, the weighted average is additionally presented, which serves as a more realistic performance indicator by reflecting the proportion of data belonging to each directional class.

As shown in

Table 5, the macro average and weighted average values for precision, recall, and F1-score all remain around 0.88, indicating a similar level of performance across the three metrics. This suggests that class imbalance is not severe and that the model maintains balanced predictive performance across all direction groups. In particular, the weighted-average results, precision of 0.889, recall of 0.888, and an F1-score of 0.888, demonstrate that the proposed model achieves a high level of consistency and reliability while accounting for the overall data distribution.

5. Discussion

The neural network–based wave direction classification model proposed in this study successfully identified the principal incident wave direction acting on a ship in navigation by learning the frequency-distribution characteristics of the motion response spectrum. The overall average accuracy was approximately 0.888, demonstrating balanced predictive performance across all directional groups. These results indicate that the model effectively captured the interrelationships among the heave, roll, and pitch responses and reliably recognized the complex frequency patterns associated with different wave heading conditions.

The quantitative performance of the model is summarized in

Table 4 and

Table 5.

Table 4 presents the classification performance for each wave direction class, where Group C achieved the highest performance with an accuracy of 1.000 and an F1-score of 0.996. Group B also showed stable and consistent performance with an F1-score of 0.908. In contrast, Group A exhibited a relatively lower F1-score of 0.731.

The overall average metrics presented in

Table 5 show that the macro average and weighted average are 0.879 and 0.888, respectively, indicating that both values are nearly identical. This suggests that class imbalance had little influence on the model’s performance and that the model maintained balanced learning without bias toward any specific directional class.

Meanwhile, the lower accuracy observed for Group A is interpreted not as a limitation of the model architecture or training procedure, but rather as a consequence of the intrinsic sensitivity of the response spectrum to changes in wave direction. In the Group B and Group C regions, the response spectra exhibit relatively mild variations in shape even when the wave direction changes; the amplitude distribution varies only slightly, and the overall spectral pattern remains consistent. In other words, these regions have relatively low shape sensitivity to directional changes, allowing the neural network to more easily learn the common spectral features.

In contrast, Group A exhibits pronounced variations in the peak locations and energy distribution of the response spectrum even with small changes in wave direction, resulting in clear shape differences among samples within the same class. This high shape sensitivity increases the intra-class variability of the data and makes it more challenging for the model to establish stable classification boundaries. In other words, Group A is characterized by substantial shape variability and a high degree of non-uniformity in the response patterns associated with directional changes, making it more susceptible to classification ambiguity.

This behavior is attributed to the physical characteristics of the bow region of the hull. The bow represents the most geometrically complex three-dimensional curved surface of the vessel, and when waves enter from the Group A sector, both the Froude–Krylov force and the diffraction force respond sensitively to small changes in the incident angle. Consequently, even within Group A, substantial intra class variability arises in terms of shifts in spectral peak location and changes in energy distribution. This high internal variability makes it difficult for the model to learn consistent patterns, ultimately contributing to the lower classification performance observed for Group A compared with the other groups.

This study employed a classification framework in which the incident wave direction is grouped into three representative directional classes (Group A, Group B, and Group C) based solely on the motion response spectrum. Such simplification offers advantages in terms of training stability and computational efficiency. However, considering realistic sea conditions, several opportunities for improvement remain. First, the directional grouping used in this study consists of relatively broad intervals, which may not fully capture fine variations in wave direction. Future research could address this limitation by further subdividing the directional range or by extending the problem from a discrete classification task to a continuous angle prediction problem, thereby enabling more refined and precise direction estimation.

There are also limitations regarding the input variables. This study considered only the spectra associated with the three degrees of freedom of ship motion (heave, roll, and pitch), whereas actual wave–structure interactions involve a wider range of measurable physical quantities, such as structural responses (stress/strain) and accelerations. Incorporating these additional measurements is expected to further enhance the classification reliability, particularly in regions such as Group A, where high sensitivity to directional changes makes the predictions more prone to confusion.

Furthermore, because the present study trained and evaluated the model using a numerically generated dataset, several factors inherent to real ocean environments, such as sensor noise, irregular wave fields, multi-directional wave systems, and variations in ship speed were not fully captured. In addition, because the response spectrum database in this study was constructed using RAOs computed from linear potential flow theory, the resulting model inherits the well-known limitations of linear hydrodynamics. Specifically, viscous effects and nonlinear wave-structure interactions are not fully represented. Prior studies have repeatedly noted that linear potential flow analysis is particularly limited in capturing nonlinear interactions in following-sea conditions and in the higher-frequency range [

38,

39]. Therefore, additional modeling approaches capable of incorporating these nonlinear and viscous phenomena will be required in future research to overcome these limitations.

Therefore, future work should incorporate time-series and spectral data measured in actual sea conditions to assess the robustness of the model and extend it into a form that remains reliable under diverse operating scenarios. Such follow-up research is expected to broaden the applicability of the proposed model and further strengthen its potential linkage with digital twin-based structural health monitoring and autonomous navigation technologies.

6. Conclusions

In this study, an artificial neural network–based method was proposed to classify the incident wave direction using the heave–roll–pitch response spectra of a ship in navigation as input. The results demonstrated that the proposed model can reliably identify wave direction information using only the frequency-distribution characteristics of the motion response spectrum, achieving a balanced overall precision of 0.888. This indicates that wave direction can be effectively classified based on the spectral shape characteristics of the response, without the need for complex inverse-analysis procedures.

Moreover, the proposed approach offers strong practical advantages because it enables wave direction recognition using only motion responses that are already measurable on board, without requiring additional mathematical modeling or external sensors. Motion sensors are standard equipment on most vessels and provide continuous real-time data; therefore, implementing the proposed method does not require any new hardware installation or modification of existing systems. The pre-trained model can be directly integrated into onboard platforms, and inference can be performed almost instantaneously, allowing rapid adaptation to changing sea states during navigation. Given these strengths, the proposed data-driven wave direction recognition framework holds significant potential for integration into various decision-support systems.

However, this study has limitations in that the directional domain was simplified into three representative groups, which may not fully capture the finer directional resolution required in real ocean environments. In addition, the input variables were restricted to only three motion components, and the model was validated primarily using a numerically generated dataset, indicating the need for further refinement in future work. In addition, the motion response spectra used in this study were constructed using RAOs derived from linear potential flow theory; therefore, the model inherits the inherent limitations of linear hydrodynamics, including the inability to fully represent viscous effects and nonlinear wave–structure interactions that occur in real ocean environments. Moreover, the numerical dataset did not incorporate sensor noise or explicitly simulated irregular wave characteristics and thus does not fully capture the uncertainties present in actual measurement conditions.

To address these limitations, future work will focus on expanding the dataset to encompass a wider range of sea states, improving directional resolution, and developing a regression-based framework for continuous wave direction estimation to enhance the model’s generalization capability. In addition, several potential improvement strategies will be considered to further strengthen classification performance, including the use of extended input features, the refinement of frequency domain feature extraction techniques, and the construction of training datasets that include a broader variety of wave conditions and scenarios.

In addition, although the present study focused on the classification of incident wave direction, the proposed data-driven framework is not inherently limited to directional estimation. The motion response spectra used in this study also contain information related to other key wave parameters, such as significant wave height and peak period, which are strongly associated with the energy level and frequency distribution of the responses. Accordingly, future work will extend the current framework toward a multi-output formulation capable of estimating multiple wave parameters simultaneously. To ensure the practical applicability of these extended capabilities, a stepwise validation process using real measurement data will be conducted. Specifically, the feasibility of the proposed approach will first be examined using experimentally measured motion response data from scaled model tests in a towing tank, followed by comprehensive validation based on long-term full-scale measurements acquired during sea trials of an operating vessel.