Local Spatial Attention Transformer with First-Order Difference for Sea Level Anomaly Field Forecast: A Regional Study in the East China Sea

Abstract

1. Introduction

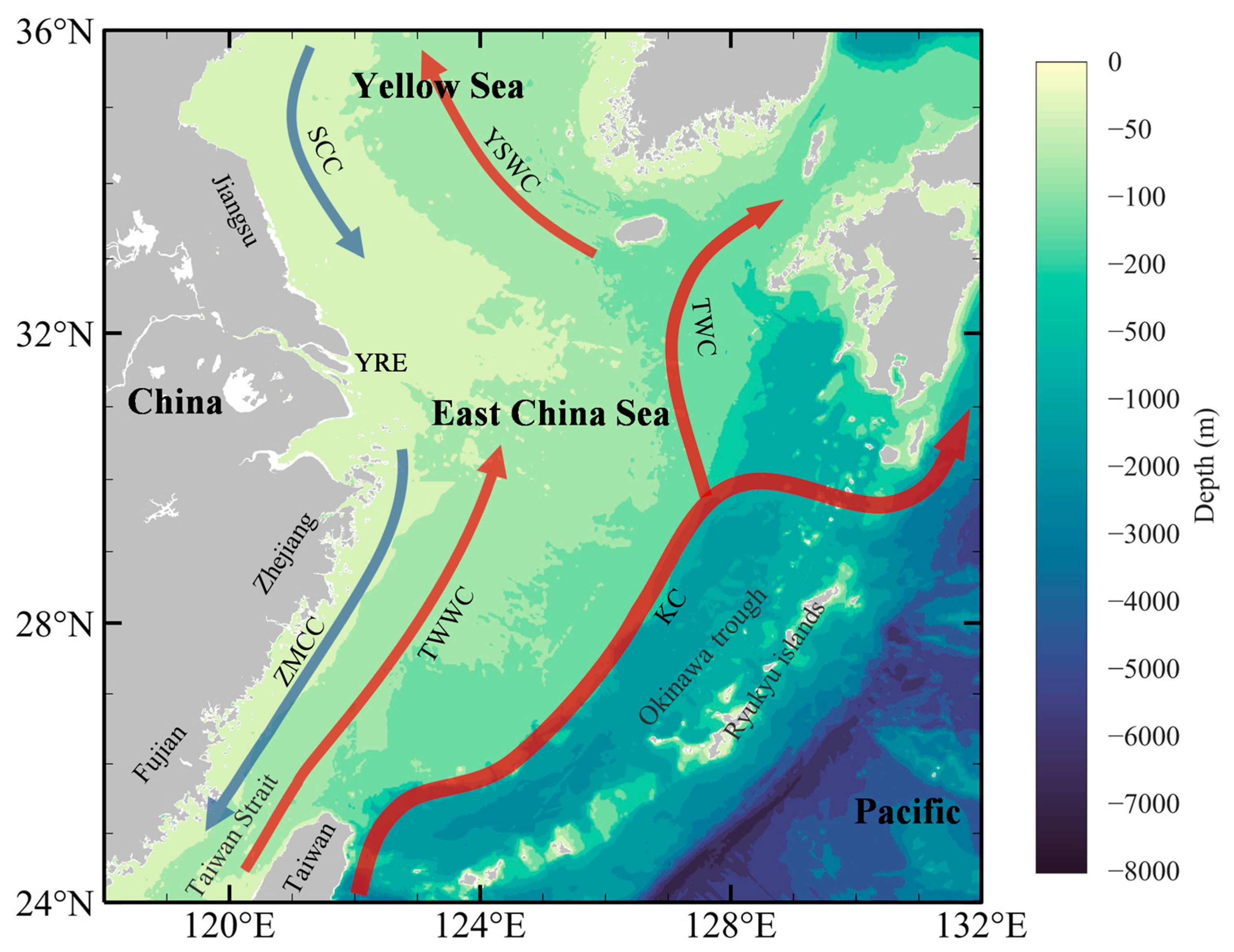

2. Study Area and Data

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Satellite Altimetry Dataset

2.3. Data Processing

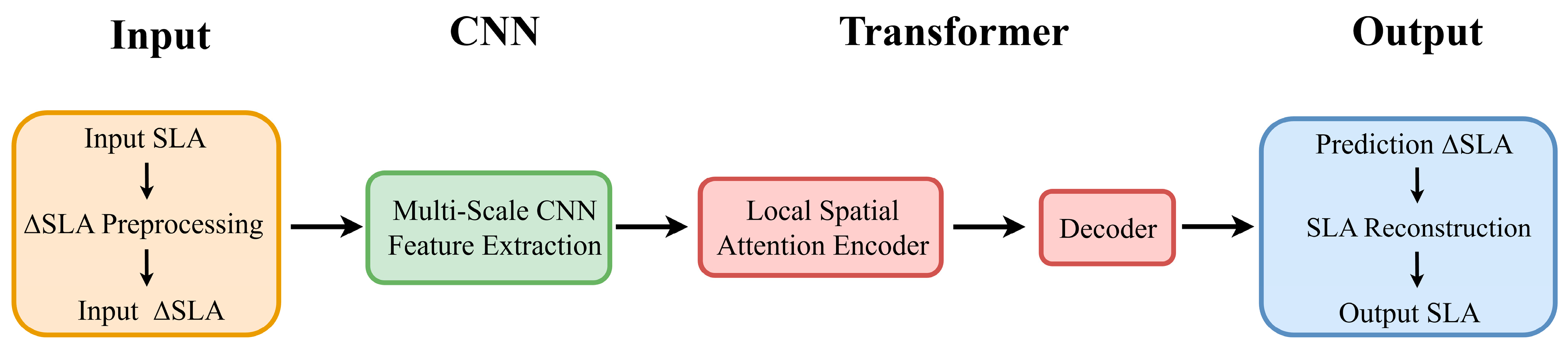

3. Method

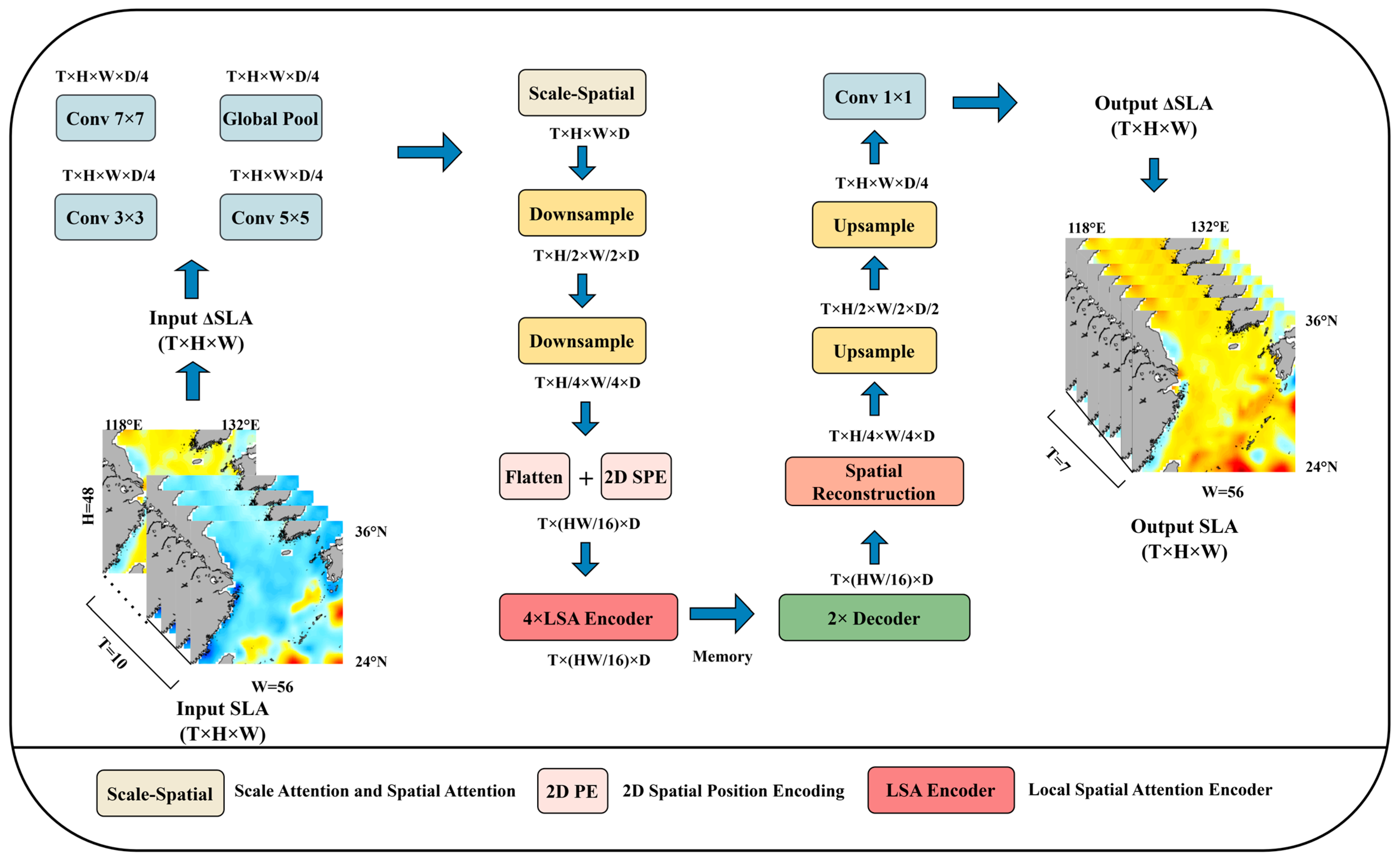

3.1. LSATrans-Net Model

3.1.1. Architecture of LSATrans-Net Model

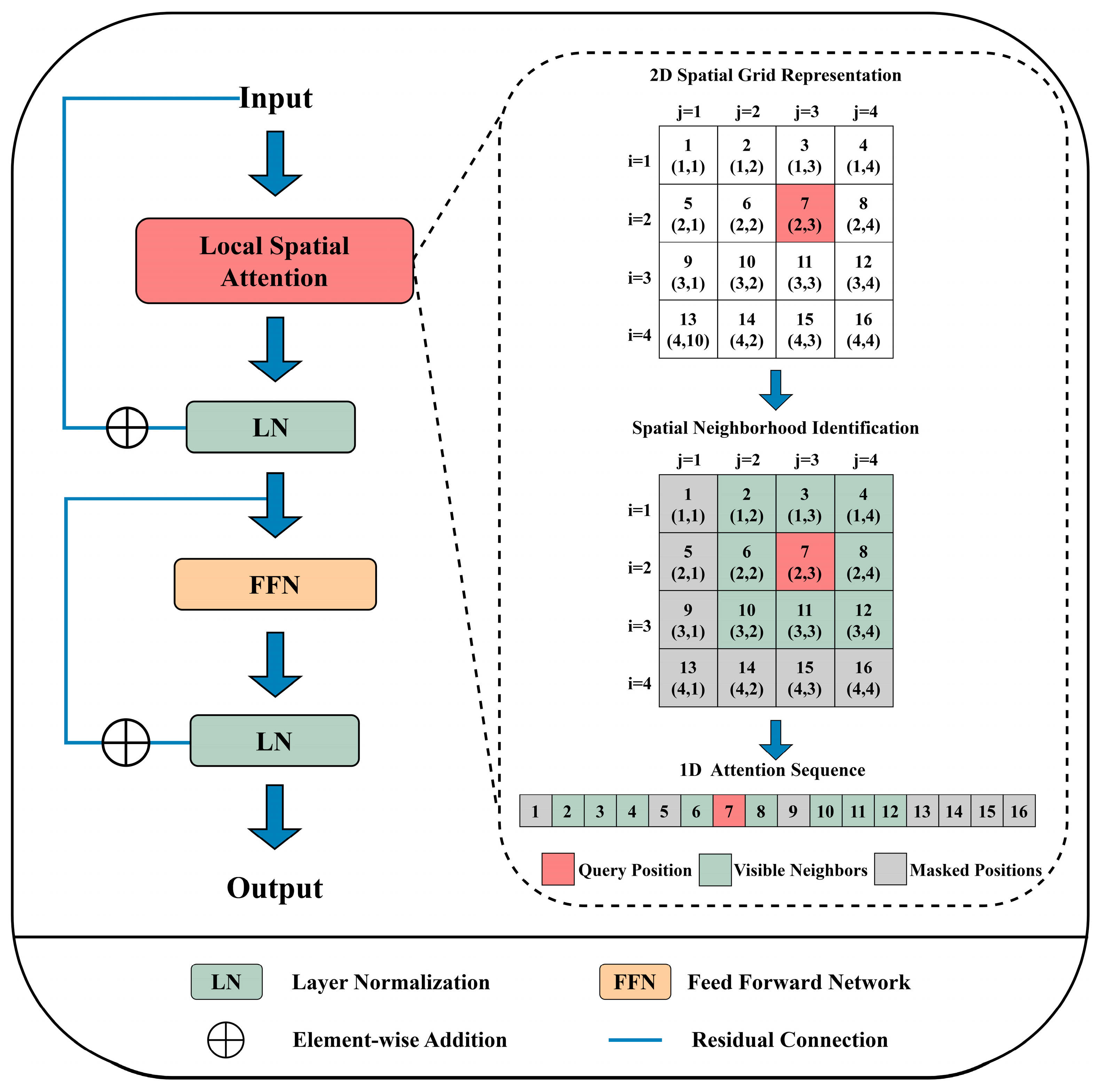

3.1.2. Local Spatial Attention

3.1.3. Experimental Implementation Details

3.2. Compared Models

- (1)

- ConvLSTM: A spatiotemporal model that combines CNN and LSTM by applying convolution operations to both inputs and hidden states, enabling the extraction of spatial features and learning of complex spatiotemporal dependencies.

- (2)

- BiLSTM: This model consists of two LSTM layers operating in opposite directions, one from past to future and the other from future to past. The architecture combines the benefits of sequential data handling and the long-term memory capacity of forward and backward LSTM [41].

- (3)

- CNN-Transformer: This model combines CNN and Transformer, employing the same multi-scale CNN module as LSATrans-Net. However, the encoder uses the self-attention mechanism, which computes attention across all spatial positions. Therefore, the CNN-Transformer serves as a direct baseline for evaluating the Local Spatial Attention mechanism of LSATrans-Net.

3.3. Evaluation Metrics

4. Results and Discussion

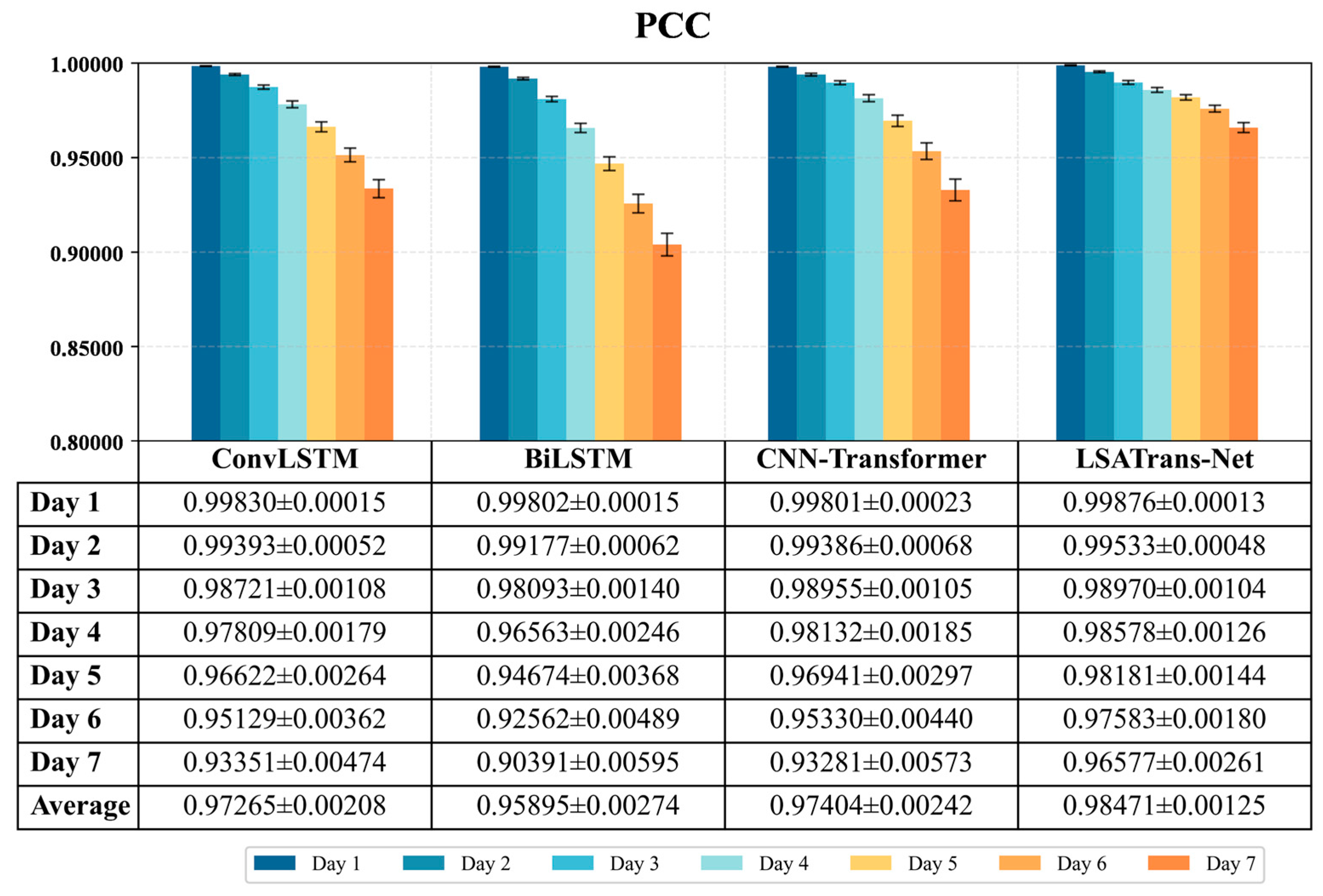

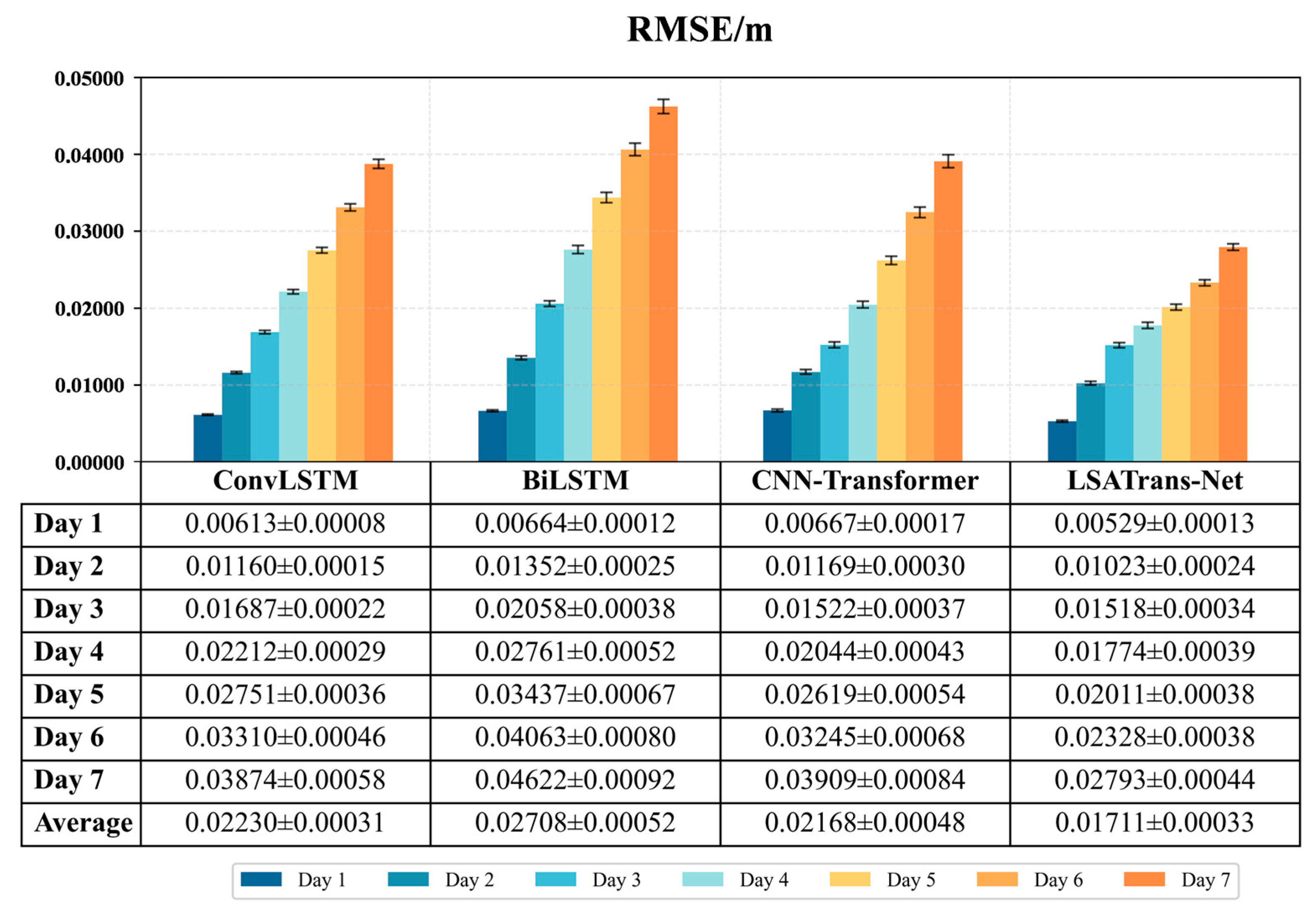

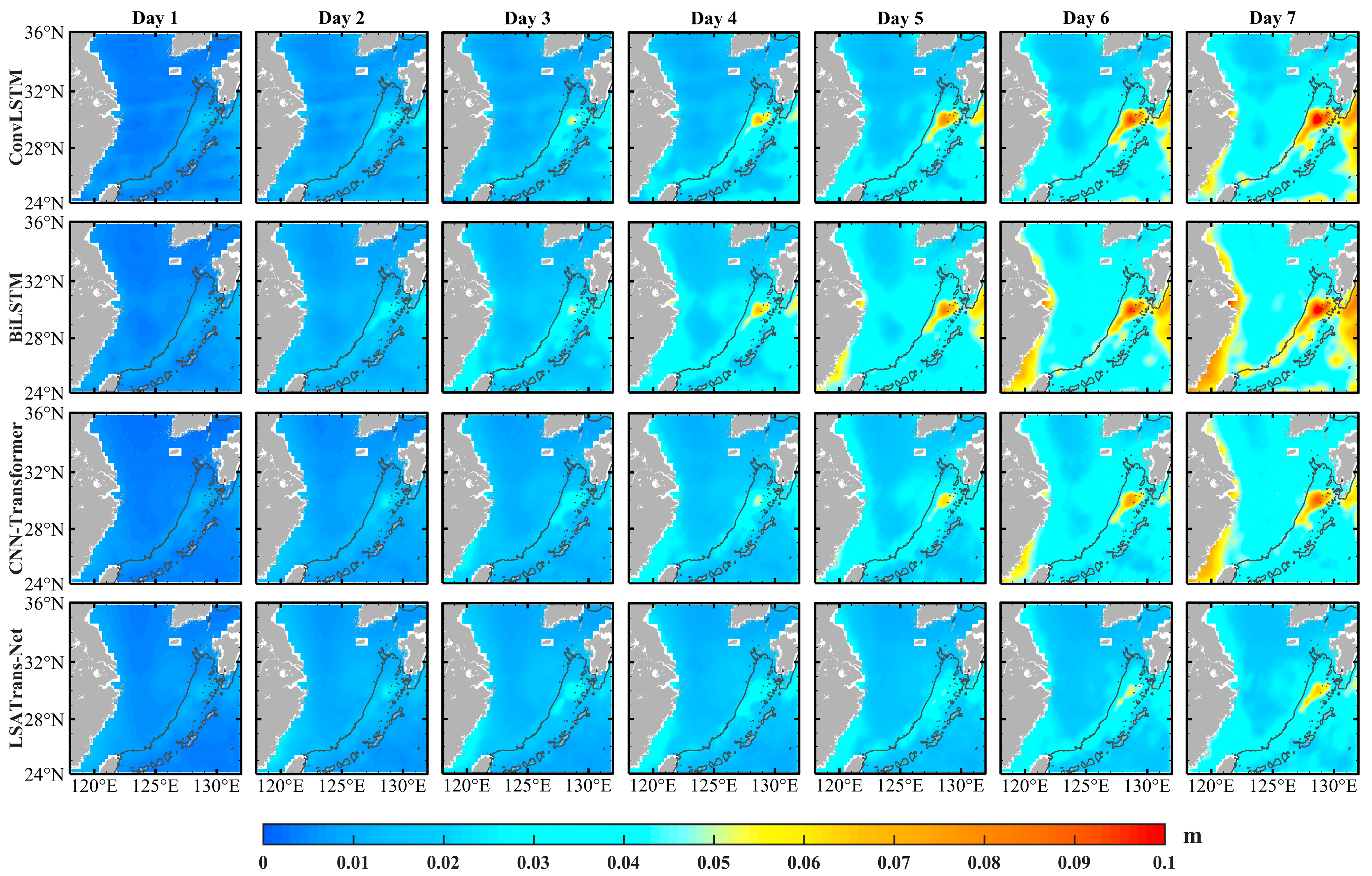

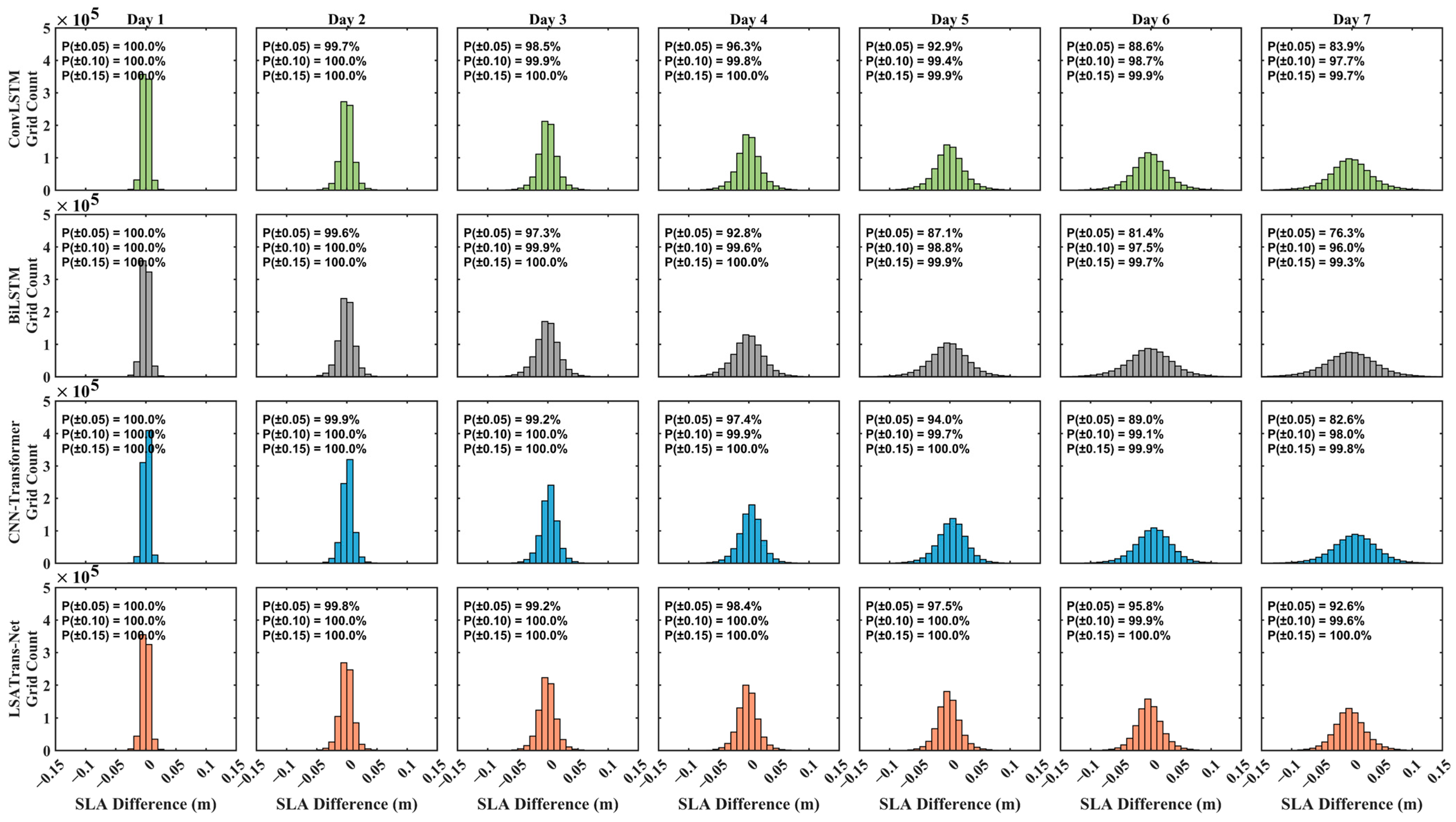

4.1. Model Validation and Comparison

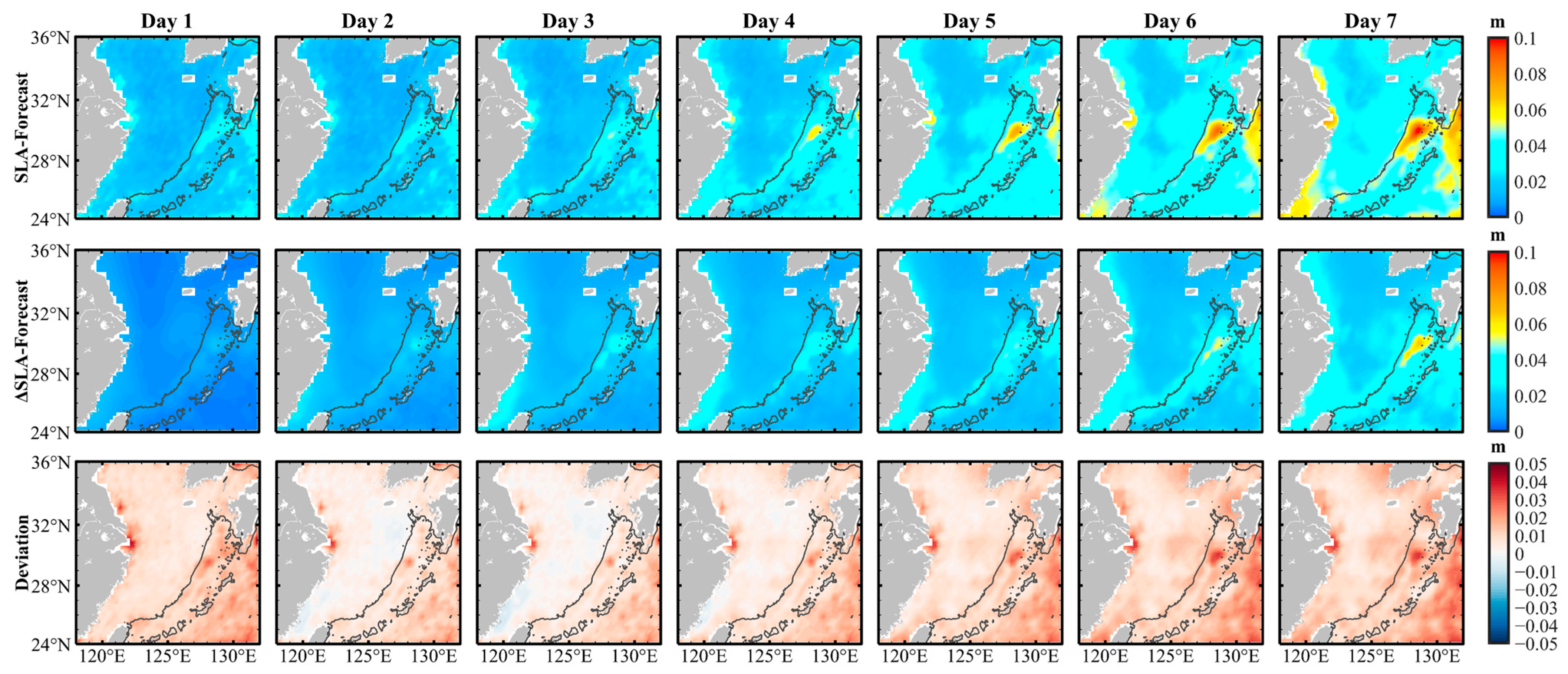

4.2. Performance Under Representative Cases

4.2.1. Normal Weather Conditions

4.2.2. Extreme Weather Conditions

4.3. Differential Strategy Experiment

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Spatial Radius | Effective Range | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | Day 5 | Day 6 | Day 7 | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 100 km | 0.99876 | 0.99533 | 0.98970 | 0.98578 | 0.98181 | 0.97583 | 0.96577 | 0.98471 |

| 3 | 300 km | 0.99868 | 0.99521 | 0.98954 | 0.98214 | 0.97524 | 0.96597 | 0.95275 | 0.97993 |

| 5 | 500 km | 0.99860 | 0.99509 | 0.98938 | 0.98002 | 0.97064 | 0.95880 | 0.94378 | 0.97662 |

| Spatial Radius | Effective Range | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | Day 5 | Day 6 | Day 7 | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 100 km | 0.00529 | 0.01023 | 0.01518 | 0.01774 | 0.02011 | 0.02328 | 0.02793 | 0.01711 |

| 3 | 300 km | 0.00537 | 0.01035 | 0.01533 | 0.02022 | 0.02384 | 0.02798 | 0.03304 | 0.01945 |

| 5 | 500 km | 0.00545 | 0.01047 | 0.01548 | 0.02093 | 0.02535 | 0.03006 | 0.03519 | 0.02042 |

References

- Nicholls, R.J.; Cazenave, A. Sea-Level Rise and Its Impact on Coastal Zones. Science 2010, 328, 1517–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horton, B.P.; Kopp, R.E.; Garner, A.J.; Hay, C.C.; Khan, N.S.; Roy, K.; Shaw, T.A. Mapping Sea-Level Change in Time, Space, and Probability. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2018, 43, 481–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.-Z.; Kumar, A.; Huang, B.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, R.-H.; Jin, F.-F. Asymmetric evolution of El Niño and La Niña: The recharge/discharge processes and role of the off-equatorial sea surface height anomaly. Clim. Dyn. 2017, 49, 2737–2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widlansky, M.J.; Long, X.; Schloesser, F. Increase in sea level variability with ocean warming associated with the nonlinear thermal expansion of seawater. Commun. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Gan, J.; Hu, J.; Wu, H.; Cai, Z.; Deng, Y. Progress on circulation dynamics in the East China Sea and southern Yellow Sea: Origination, pathways, and destinations of shelf currents. Prog. Oceanogr. 2021, 193, 102553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Gao, J.; Yin, J.; Wu, S. Assessing the potential of compound extreme storm surge and precipitation along China’s coastline. Weather Clim. Extrem. 2024, 45, 100702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Jevrejeva, S.; Jackson, L.P.; Moore, J.C. Coastal Sea level rise around the China Seas. Glob. Planet. Change 2019, 172, 454–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Yin, Z.; Wang, J.; Xu, S. National assessment of coastal vulnerability to sea-level rise for the Chinese coast. J. Coast. Conserv. 2012, 16, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Plag, H.-P.; Hamlington, B.D.; Xu, Q.; He, Y. Regional sea level variability in the Bohai Sea, Yellow Sea, and East China Sea. Cont. Shelf Res. 2015, 111, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Liu, Y.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, H.; Fu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tang, Q. Absolute Sea Level Changes Along the Coast of China from Tide Gauges, GNSS, and Satellite Altimetry. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2022, 127, e2022JC018994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storkey, D.; Blockley, E.W.; Furner, R.; Guiavarc’h, C.; Lea, D.; Martin, M.J.; Barciela, R.M.; Hines, A.; Hyder, P.; Siddorn, J.R. Forecasting the ocean state using NEMO:The new FOAM system. J. Oper. Oceanogr. 2010, 3, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, E.R.; Spillman, C.M.; Church, J.A.; McIntosh, P.C. Seasonal prediction of global sea level anomalies using an ocean–atmosphere dynamical model. Clim. Dyn. 2014, 43, 2131–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederikse, T.; Lee, T.; Wang, O.; Kirtman, B.; Becker, E.; Hamlington, B.; Limonadi, D.; Waliser, D. A Hybrid Dynamical Approach for Seasonal Prediction of Sea-Level Anomalies: A Pilot Study for Charleston, South Carolina. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2022, 127, e2021JC018137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, P.K.; Islam, T.; Singh, S.K.; Petropoulos, G.P.; Gupta, M.; Dai, Q. Forecasting Arabian Sea level rise using exponential smoothing state space models and ARIMA from TOPEX and Jason satellite radar altimeter data. Meteorol. Appl. 2016, 23, 633–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Leetmaa, A. Forecasts of tropical Pacific SST and sea level using a Markov model. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2000, 27, 2701–2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.R.; Chu, P.S.; Schroeder, T.; Colasacco, N. Seasonal sea-level forecasts by canonical correlation analysis—An operational scheme for the US-affiliated Pacific Islands. Int. J. Climatol. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2007, 27, 1389–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braakmann-Folgmann, A.; Roscher, R.; Wenzel, S.; Uebbing, B.; Kusche, J. Sea level anomaly prediction using recurrent neural networks. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1710.07099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, K.; Deo, M.C.; Ravichandran, M. Prediction of Sea Surface Temperature by Combining Numerical and Neural Techniques. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2016, 33, 1715–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Wan, J.; Liu, S. Estimation of Sea Level Variability in the China Sea and Its Vicinity Using the SARIMA and LSTM Models. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2020, 13, 3317–3326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winona, A.Y.; Adytia, D. Short Term Forecasting of Sea Level by Using LSTM with Limited Historical Data. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Data Science and Its Applications, Bandung, Indonesia, 5–6 August 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Balogun, A.-L.; Adebisi, N. Sea level prediction using ARIMA, SVR and LSTM neural network: Assessing the impact of ensemble Ocean-Atmospheric processes on models’ accuracy. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2021, 12, 653–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Li, S.; Wang, A.; Yang, J.; Chen, G. Altimeter Observation-Based Eddy Nowcasting Using an Improved Conv-LSTM Network. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Ji, Q.; Jia, X.; Liu, Y.; Han, G.; Lin, X. Significant Wave Height Prediction in the South China Sea Based on the ConvLSTM Algorithm. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, P.; Li, S.; Song, J.; Gao, Y. Prediction of Sea Surface Temperature in the South China Sea Based on Deep Learning. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascanu, R.; Mikolov, T.; Bengio, Y. On the difficulty of training recurrent neural networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Atlanta, GA, USA, 16–21 June 2013; pp. 1310–1318. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, X.; Chen, Z.; Wang, H.; Yeung, D.-Y.; Wong, W.-K.; Woo, W.-C. Convolutional LSTM network: A machine learning approach for precipitation nowcasting. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2015, 28, 802–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 5998–6008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Lin, P.; Liu, H.; Wang, P.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, W.; Yu, Z.; Jiang, J.; Li, Y.; He, H. A New Transformer Network for Short-Term Global Sea Surface Temperature Forecasting: Importance of Eddies. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Bao, S.; Dong, W.; Wang, S.; Zhang, X.; Shao, C.; Zhu, J.; Li, X. PGTransNet: A physics-guided transformer network for 3D ocean temperature and salinity predicting in tropical Pacific. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1477710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Leung, L.R.; Chiew, F.H.; AghaKouchak, A.; Ying, K.; Zhang, Y. CAS-Canglong: A skillful 3D Transformer model for sub-seasonal to seasonal global sea surface temperature prediction. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.05369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, H.J. Tobler’s First Law and Spatial Analysis. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2004, 94, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiatowski, T.; Bölcskei, H. A Mathematical Theory of Deep Convolutional Neural Networks for Feature Extraction. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2018, 64, 1845–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wang, B.; Wu, W.; Xi, C.; Wang, J. Sea-water-level prediction via combined wavelet decomposition, neuro-fuzzy and neural networks using SLA and wind information. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2020, 39, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Lu, T.; Huang, J.; He, X.; Sun, X. An Improved VMD–EEMD–LSTM Time Series Hybrid Prediction Model for Sea Surface Height Derived from Satellite Altimetry Data. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Q.; Li, W.; Han, G.; Hou, G.; Liu, S.; Gong, Y.; Qu, P. A Deep Learning Model for Forecasting Sea Surface Height Anomalies and Temperatures in the South China Sea. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2021, 126, e2021JC017515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokhrel, P.; Ioup, E.; Simeonov, J.; Hoque, M.T.; Abdelguerfi, M. A Transformer-Based Regression Scheme for Forecasting Significant Wave Heights in Oceans. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2022, 47, 1010–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, B. Regional Sea Level Rise Prediction in Monterey Bay with LSTMs and Vertical Land Motion. Master’s Thesis, San José State University, San Jose, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Gan, J. Variability of the Kuroshio in the East China Sea derived from satellite altimetry data. Deep Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 2012, 59, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, D.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Dong, C. Eddy analysis in the Eastern China Sea using altimetry data. Front. Earth Sci. 2015, 9, 709–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avenas, A.; Mouche, A.; Tandeo, P.; Piolle, J.-F.; Chavas, D.; Fablet, R.; Knaff, J.; Chapron, B. Reexamining the Estimation of Tropical Cyclone Radius of Maximum Wind from Outer Size with an Extensive Synthetic Aperture Radar Dataset. Mon. Weather Rev. 2023, 151, 3169–3189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zrira, N.; Kamal-Idrissi, A.; Farssi, R.; Khan, H.A. Time series prediction of sea surface temperature based on BiLSTM model with attention mechanism. J. Sea Res. 2024, 198, 102472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Cai, J.; Wu, L.; Guo, H.; Chen, Z.; Jing, Z.; Gan, B. The Intensifying East China Sea Kuroshio and Disappearing Ryukyu Current in a Warming Climate. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2024, 51, e2023GL106944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yu, Y.; Xu, H.; Zhao, D.; Liang, J. A numerical study on the effects of a midlatitude upper-level trough on the track and intensity of Typhoon Bavi (2020). Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 10, 1056882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Tang, D.; Liu, H.; Sui, Y.; Gu, X. Composite Analysis-Based Machine Learning for Prediction of Tropical Cyclone-Induced Sea Surface Height Anomaly. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2023, 16, 2644–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dataset | Time Range Input Dimension Output Dimension Train Split Validation Split Test Split | 1993–2020 [1, 10, 48, 56] [1, 7, 48, 56] January 1993–December 2015 January 2016–December 2019 January 2020–December 2020 |

| Model Architecture | Feature Dimension Number of Heads Encoder Layers Decoder Layers Dropout Spatial Radius | 256 4 4 2 0.1 1 |

| Training Hyperparameters | Max Epochs Batch Size Initial Learning Rate Optimizer Early Stopping Patience | 100 16 5 × 10−5 ReduceLROnPlateau 10 |

| Ahead/ Model Name | ConvLSTM | BiLSTM | CNN-Transformer | LSATrans-Net |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | 0.00450 + 0.00006 | 0.00491 ± 0.00010 | 0.00498 ± 0.00014 | 0.00389 + 0.00011 |

| Day 2 | 0.00845 ± 0.00012 | 0.01005 ± 0.00020 | 0.00872 + 0.00024 | 0.00754 ± 0.00021 |

| Day 3 | 0.01222 ± 0.00016 | 0.01537 ± 0.00032 | 0.01136 + 0.00030 | 0.01128 ± 0.00028 |

| Day 4 | 0.01605 + 0.00021 | 0.02071 ± 0.00044 | 0.01533 ± 0.00036 | 0.01327 ± 0.00032 |

| Day 5 | 0.02006 ± 0.00028 | 0.02587 + 0.00057 | 0.01980 ± 0.00045 | 0.01509 ± 0.00032 |

| Day 6 | 0.02430 + 0.00037 | 0.03069 ± 0.00069 | 0.02467 ± 0.00057 | 0.01754 + 0.00033 |

| Day 7 | 0.02863 + 0.00049 | 0.03503 ± 0.00080 | 0.02983 ± 0.00070 | 0.02113 ± 0.00038 |

| Average | 0.01632 ± 0.00023 | 0.02038 ± 0.00043 | 0.01638 ± 0.00033 | 0.01282 ± 0.00025 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Chen, H.; Jiang, L.; Ji, Q.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Han, G. Local Spatial Attention Transformer with First-Order Difference for Sea Level Anomaly Field Forecast: A Regional Study in the East China Sea. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2026, 14, 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010054

Wang Y, Chen H, Jiang L, Ji Q, Li J, Wang J, Han G. Local Spatial Attention Transformer with First-Order Difference for Sea Level Anomaly Field Forecast: A Regional Study in the East China Sea. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2026; 14(1):54. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010054

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yuting, Hui Chen, Lifang Jiang, Qiyan Ji, Juan Li, Jianxin Wang, and Guoqing Han. 2026. "Local Spatial Attention Transformer with First-Order Difference for Sea Level Anomaly Field Forecast: A Regional Study in the East China Sea" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 14, no. 1: 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010054

APA StyleWang, Y., Chen, H., Jiang, L., Ji, Q., Li, J., Wang, J., & Han, G. (2026). Local Spatial Attention Transformer with First-Order Difference for Sea Level Anomaly Field Forecast: A Regional Study in the East China Sea. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 14(1), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010054