Formulated Diets Drive Gonadal Maturity but Reduce Larval Success in Paracentrotus lividus

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Plan

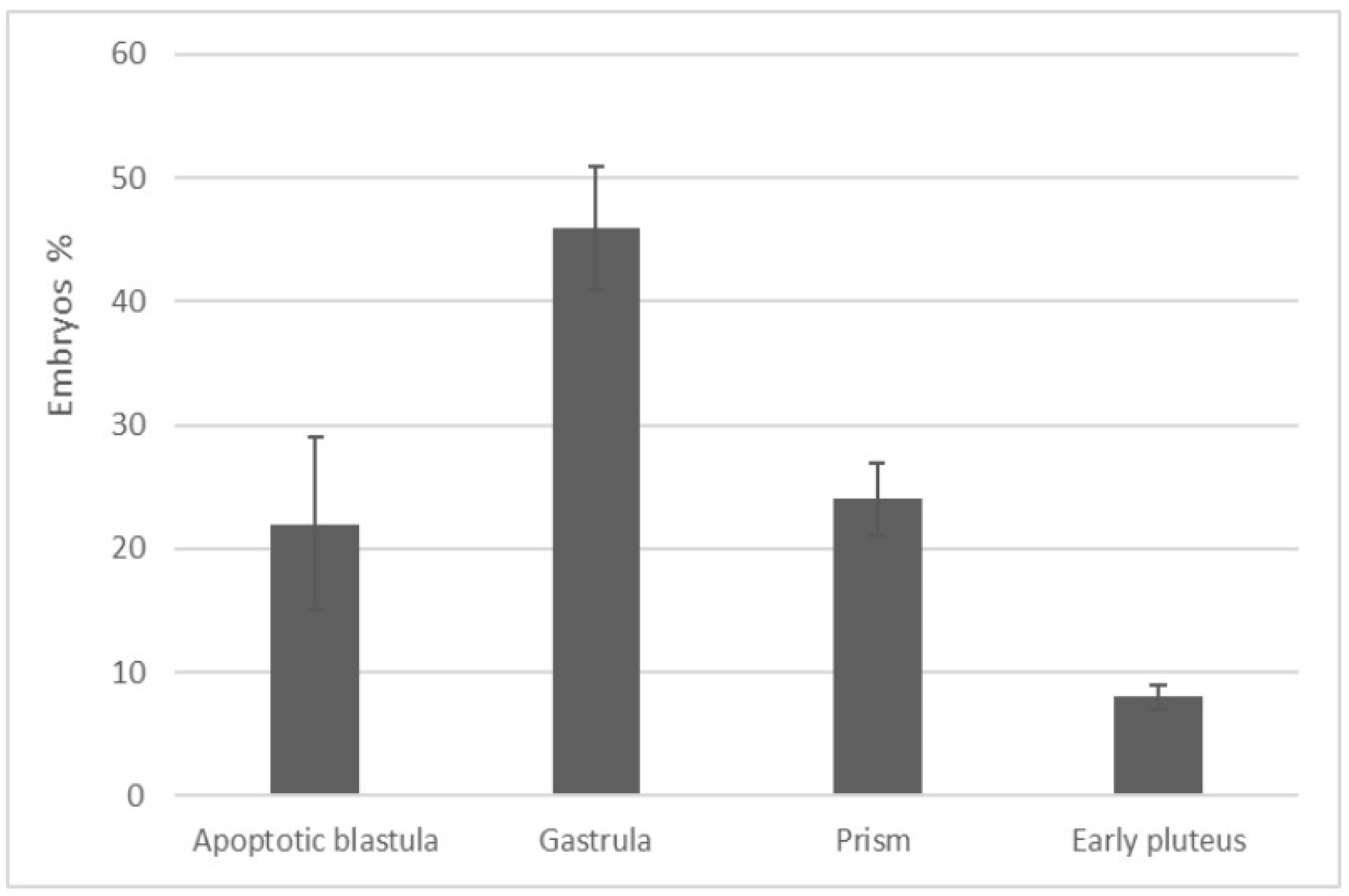

2.2. Fertilization

2.3. Water and Biotic Parameters

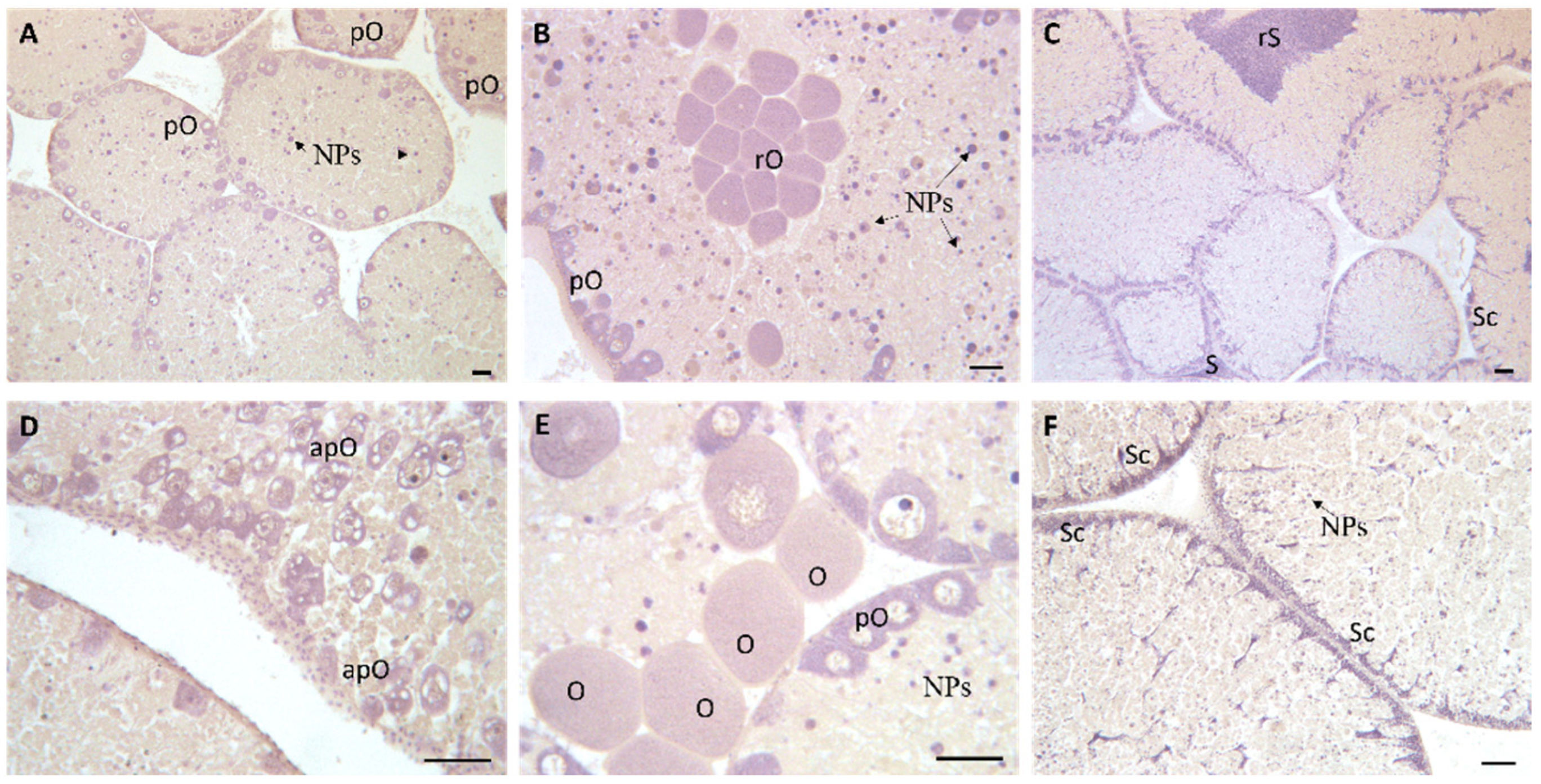

2.4. Histological Analysis of Gonads

2.5. Statistical Analysis of Data

3. Results

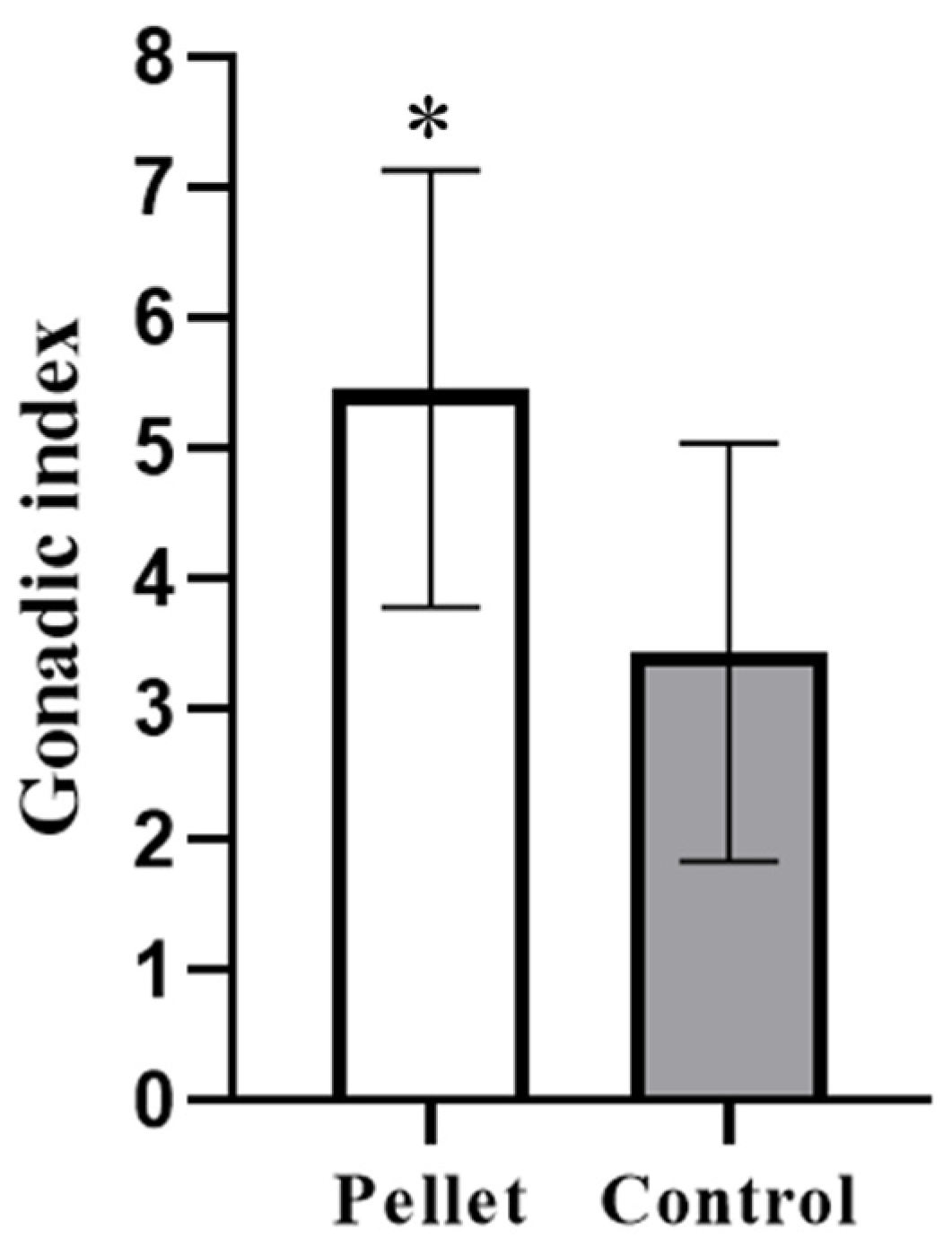

3.1. Gonadosomatic Indices

3.2. Water Quality

3.3. Histopathological Analyses

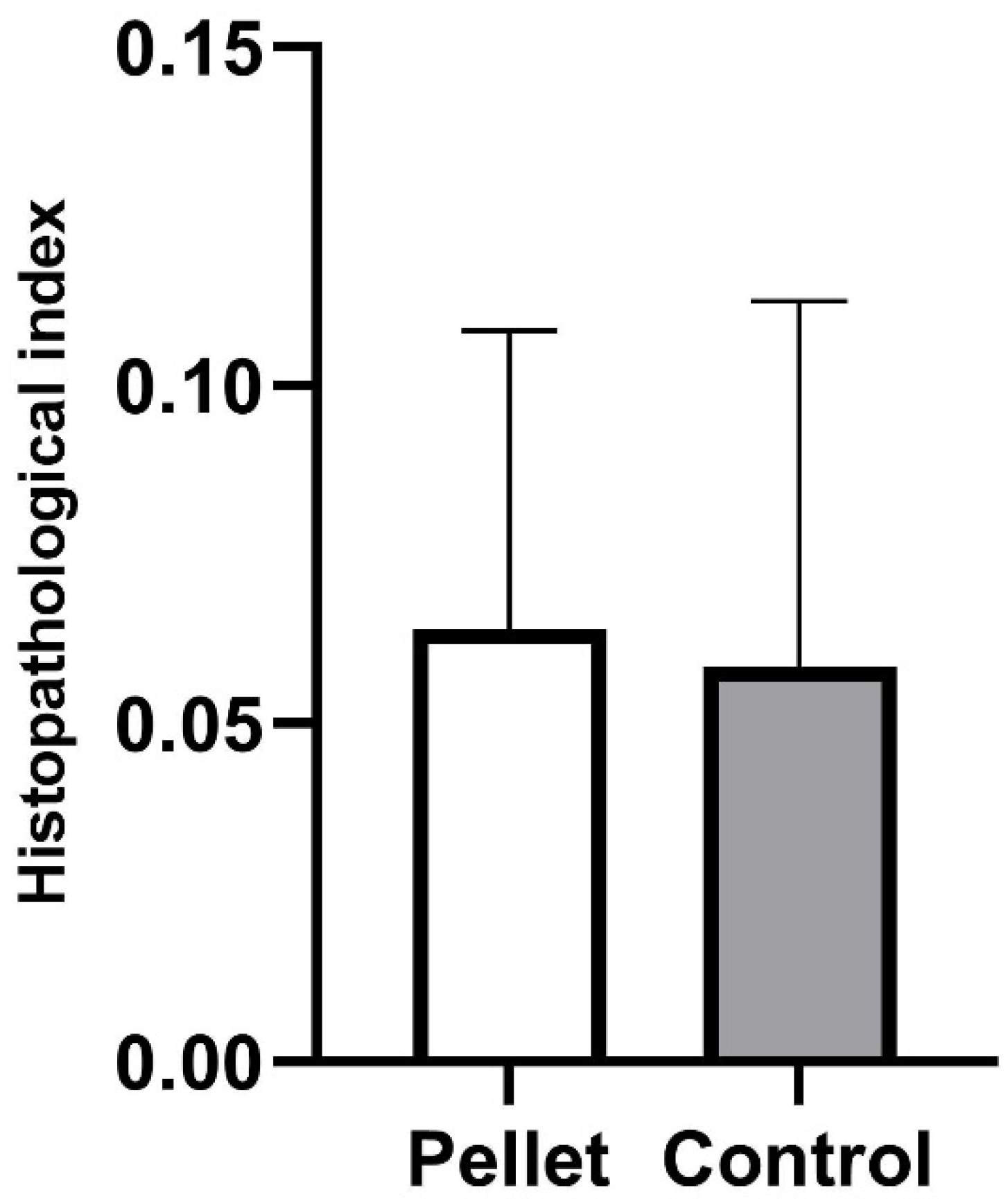

3.4. In Vitro Fertilization

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Underwood, A.J.; Denley, E.J. Paradigms, explanations, and generalizations in models for the structure of intertidal communities on rocky shores. In Ecological Communities; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 151–180. [Google Scholar]

- Carboni, S.; Vignier, J.; Chiantore, M.; Tocher, D.R.; Migaud, H. Effects of dietary microalgae on growth, survival and fatty acid composition of sea urchin Paracentrotus lividus throughout larval development. Aquaculture 2012, 324, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefánsson, G.; Kristinsson, H.; Ziemer, N.; Hannon, C.; James, P. Markets for sea urchins: A review of global supply and markets. Skýrsla Matís 2017, 45, 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- Boero, F.; Fanelli, G.; Geraci, S. Desertificazione e ricolonizzazione in ambiente roccioso: Un modello di sviluppo di biocenosi. Mem. Soc. Tic. Sci. Nat. 1993, 4, 219–228. [Google Scholar]

- Zupo, V.; Alexander, T.J.; Edgar, G.J. Relating trophic resources to community structure: A predictive index of food availability. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2017, 4, 160515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palací́n, C.; Giribet, G.; Carner, S.; Dantart, L.; Turon, X. Low densities of sea urchins influence the structure of algal assemblages in the western Mediterranean. J. Sea Res. 1998, 39, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, F.; Baião, L.F.; Moutinho, S.; Reis, B.; Oliveira, A.; Arenas, F.; Maia, M.R.G.; Fonseca, A.J.M.; Pintado, M.; Valente, L.M. The effect of sex, season and gametogenic cycle on gonad yield, biochemical composition and quality traits of Paracentrotus lividus along the North Atlantic coast of Portugal. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 2994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A.; Arshad, A.; Yusoff, F.M. Sea urchins (Echinodermata: Echinoidea): Their biology, culture and bioactive compounds. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Agricultural, Ecological and Medical Sciences (AEMS-2014), London, UK, 3–4 July 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, D.; Moran, D. The Economic Value of Biodiversity; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartori, D.; Pellegrini, D.; Macchia, S.; Gaion, A. Can echinoculture be a feasible and effective activity? Analysis of fast reliable breeding conditions to promote gonadal growth and sexual maturation in Paracentrotus lividus. Aquaculture 2016, 451, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarron, E.; Burnell, G.; Mouzakitis, G. Growth assessment on three size classes of the purple sea urchin Paracentrotus lividus using continuous and intermittent feeding regimes. Aquaculture 2009, 288, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boettger, S.A.; Devin, M.G.; Walker, C.W. Suspension of gametogenesis in green sea urchins experiencing invariant photoperiod. Aquaculture 2006, 261, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosjean, P.; Spirlet, C.; Jangoux, M. Experimental study of growth in the echinoid Paracentrotus lividus (Lamarck, 1816) (Echinodermata). J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 1996, 201, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, S.C.; Price, R.J.; Tom, P.D.; Lawrence, J.M.; Lawrence, A.L. Comparison of gonad quality factors: Color, hardness and resilience, of Strongylocentrotus franciscanus between sea urchins fed prepared feed or algal diets and sea urchins harvested from the Northern California fishery. Aquaculture 2004, 233, 405–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M.S. The reproductive cycle of the sea urchin Psammechinus miliaris (Echinodermata: Echinoidea) in a Scottish sea loch. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 2000, 80, 909–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, E.J.; Kelly, M.S. Enhanced production of the sea urchin Paracentrotus lividus in integrated open-water cultivation with Atlantic salmon Salmo salar. Aquaculture 2007, 273, 573–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartori, D.; Scuderi, A.; Sansone, G.; Gaion, A. Echinoculture: The rearing of Paracentrotus lividus in a re-circulating aquaculture system—Experiments of artificial diets for the maintenance of sexual maturation. Aquac. Int. 2015, 23, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unuma, T.; Yamamoto, T.; Akiyama, T.; Shiraishi, M.; Ohta, H. Quantitative changes in yolk protein and other components in the ovary and testis of the sea urchin Pseudocentrotus depressus. J. Exp. Biol. 2003, 206, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baião, L.F.; Rocha, C.; Lima, R.C.; Marques, A.; Valente, L.M.; Cunha, L.M. Sensory profiling, liking and acceptance of sea urchin gonads from the North Atlantic coast of Portugal, aiming future aquaculture applications. Food Res. Int. 2021, 140, 109873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, K.; Hamid, N.; Silcock, P.; Sewell, M.A.; Barker, M.; Weaver, A.; Then, S.; Delahunty, C.; Bremer, P. Effect of manufactured diets on the yield, biochemical composition and sensory quality of Evechinus chloroticus sea urchin gonads. Aquaculture 2010, 308, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupo, V.; Fresi, E. A study on the food web of the Posidonia oceanica (L.) Delile ecosystem: Analysis of the gut contents of decapod crustaceans. Rapp. Proc. Verb. Réun. Comm. Int. Explor. Sci. Mer Médit. 1985, 29, 189–192. [Google Scholar]

- Maggiore, F.; Berthon, J.F.; Boudouresque, C.F.; Lawrence, J. Données préliminaires sur les relations entre Paracentrotus lividus, Arbacia lixula et le phytobenthos dans la baie de Port-Cros (Var, France, Méditerranée). In Colloque International sur Paracentrotus Lividus et les Oursins Comestibles; GIS Posidonie: Marseille, France, 1987; pp. 65–82. [Google Scholar]

- Verlaque, M. Relations entre Paracentrotus lividus (Lamarck) et le phytobenthos de Méditerranée occidentale. In Colloque International sur Paracentrotus Lividus et les Oursins Comestibles; GIS Posidonie: Marseille, France, 1987; pp. 5–36. [Google Scholar]

- Ruocco, N.; Costantini, S.; Zupo, V.; Lauritano, C.; Caramiello, D.; Ianora, A.; Budillon, A.; Romano, G.; Nuzzo, G.; D’Ippolito, G.; et al. Toxigenic effects of two benthic diatoms upon grazing activity of the sea urchin: Morphological, metabolomic and de novo transcriptomic analysis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 5622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharbi, M.; Glaviano, F.; Federico, S.; Pinto, B.; Cosmo, A.D.; Costantini, M.; Zupo, V. Scale-up of an aquaculture plant for reproduction and conservation of the sea urchin Paracentrotus lividus: Development of post-larval feeds. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, P.M.; Ferreira, S.M.; Albano, P.; Raposo, A.; Costa, J.L.; Pombo, A. Can artificial diets be a feasible alternative for the gonadal growth and maturation of the sea urchin Paracentrotus lividus (Lamarck, 1816). J. World Aquac. Soc. 2020, 51, 463–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbrocini, A.; Volpe, M.G.; Hoseinifar, S.H.; Siano, F.; Coccia, E.; Scordella, G.; Licchelli, C.; Paolucci, M. Paracentrotus lividus roe enhancement by a short-time rearing in offshore cages using two agar-based experimental feed. Int. J. Aquat. Biol. 2019, 7, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, H.; Watts, S.; Lawrence, A.; Lawrence, J.; Desmond, R. The effect of dietary protein on consumption, survival, growth and production of the sea urchin Lytechinus variegatus. Aquaculture 2006, 254, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupo, V.; Glaviano, F.; Paolucci, M.; Ruocco, N.; Polese, G.; Di Cosmo, A.; Costantini, M.; Mutalipassi, M. Roe enhancement of Paracentrotus lividus: Nutritional effects of fresh and formulated diets. Aquac. Nutr. 2019, 25, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenco, S.; Jose, R.; Andrade, C.; Valente, L.M. Growth performance and gonad yield of sea urchin Paracentrotus lividus (Lamarck, 1816) fed with diets of increasing protein:energy ratios. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2020, 270, 114690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, S.; Takahashi, K.; Kaneta, T.; Sugawara, A.; Narita, M.; Kato, S.; Akino, M.; Takeda, H.; Hasegawa, N.; Machiguchi, Y.; et al. Modest dietary protein requirement for sea urchin gonad production demonstrated by feeding trials with consideration of protein leaching. Aquac. Nutr. 2022, 2022, 314022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repolho, T.F.B.; Costa, M.H.; de Jesus Luís, O.; de Matos Gago, J.A.E. Broodstock diet effect on sea urchin Paracentrotus lividus (Lamarck, 1816) endotrophic larvae development: Potential for their year-round use in environmental toxicology assessment. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2011, 74, 584–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundu, G.; Cannavacciuolo, A.; Nannini, M.; Somma, E.; Munari, M.; Zupo, V.; Farina, S. Development of an efficient, noninvasive method for identifying gender year-round in the sea urchin Paracentrotus lividus. Aquaculture 2023, 564, 739082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbrocini, A.; D’Adamo, R. Gamete maturation and gonad growth in fed and starved sea urchin Paracentrotus lividus (Lamarck, 1816). J. Shellfish Res. 2010, 29, 1051–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, G.; Ge, H.; Zhang, L. Effects of Various Natural Diets on Gonad Development, Roe Quality, and Intestinal Microbiota of the Purple Sea Urchin (Heliocidaris crassispina). Aquac. Nutr. 2025, 28, 3196037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyrus, M.D.; Bolton, J.; Scholtz, R.; Macey, B. Advantages of Ulva (Chlorophyta) as an additive in sea urchin formulated feeds: Effects on palatability, consumption and digestibility. Aquac. Nutr. 2015, 21, 578–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shpigel, M.; McBride, S.C.; Marciano, S.; Lupatsch, I. The effect of photoperiod and temperature on the reproduction of European sea urchin Paracentrotus lividus. Aquaculture 2004, 232, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, N.; Okamura, H. Effects of heavy metals on sea urchin embryo development. 1. Tracing the cause by the effects. Chemosphere 2004, 55, 1403–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambardella, C.; Marcellini, F.; Falugi, C.; Varrella, S.; Corinaldesi, C. Early-stage anomalies in the sea urchin (Paracentrotus lividus) as bioindicators of multiple stressors in the marine environment: Overview and future perspectives. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 287, 117608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen-Rengifo, M.; Garcia, E.; Hernandez, C.A.; Hernandez, J.C.; Clemente, S. Global warming and ocean acidification affect fertilization and early development of the sea urchin Paracentrotus lividus. Cah. Biol. Mar. 2013, 54, 667–675. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.U.; Lee, S.C.; Lee, Y.C.; Vrtnik, S.; Kim, C.; Lee, S.; Lee, Y.B.; Nam, B.; Lee, J.W.; Park, S.Y.; et al. Sea-urchin-like iron oxide nanostructures for water treatment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2013, 262, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morroni, L.; Sartori, D.; Costantini, M.; Genovesi, L.; Magliocco, T.; Ruocco, N.; Buttino, I. First molecular evidence of the toxicogenetic effects of copper on sea urchin Paracentrotus lividus embryo development. Water Res. 2019, 160, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spirlet, C.; Grosjean, P.; Jangoux, M. Optimization of gonad growth by manipulation of temperature and photoperiod in cultivated sea urchins, Paracentrotus lividus (Lamarck) (Echinodermata). Aquaculture 2000, 185, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.M.; Carreira, S.; Costa, M.H.; Caeiro, S. Development of histopathological indices in a commercial marine bivalve (Ruditapes decussatus) to determine environmental quality. Aquat. Toxicol. 2013, 126, 442–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, T.; Coppola, F.; Leite, C.; Carbone, M.; Paris, D.; Motta, A.; Di Cosmo, A.; Soares, A.M.V.M.; Mollo, E.; Freitas, R.; et al. An alien metabolite vs. a synthetic chemical hazard: An ecotoxicological comparison in the Mediterranean blue mussel. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 892, 164476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Ayari, T.; Ben Ahmed, R.; Bouriga, N.; Gravato, C.; Chelbi, E.; Nechi, S.; El Menif, N.T. Florfenicol induces malformations of embryos and causes altered lipid profile, oxidative damage, neurotoxicity, and histological effects on gonads of adult sea urchin, Paracentrotus lividus. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2024, 110, 104533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, S.; Köhler, A. Gonadal lesions of female sea urchin (Psammechinus miliaris) after exposure to the polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon phenanthrene. Mar. Environ. Res. 2009, 68, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarly, M.S.; Pedro, C.A.; Bruno, C.S.; Raposo, A.; Quadros, H.C.; Pombo, A.; Gonçalves, S.C. Use of the gonadal tissue of the sea urchin Paracentrotus lividus as a target for environmental contamination by trace metals. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 89559–89580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, L.; Rakaj, A.; Fianchini, A.; Tancioni, L.; Vizzini, S.; Boudouresque, C.F.; Scardi, M. Trophic requirements of the sea urchin Paracentrotus lividus varies at different life stages: Comprehension of species ecology and implications for effective feeding formulations. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 865450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupi, V. A study on the food web of the Posidonia oceanica ecosystem: Analysis of the gut contents of echinoderms. In International Workshop on Posidonia Oceanica Beds; GIS Posidonie Publishing: Corte, France, 1984; pp. 1–1984. [Google Scholar]

- Boudouresque, C.F.; Verlaque, M. Ecology of Paracentrotus lividus. Dev. Aquac. Fish. Sci. 2001, 32, 177–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudouresque, C.F.; Verlaque, M. Chapter 21—Paracentrotus lividus. Dev. Aquac. Fish. Sci. 2013, 38, 297–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonsdorff, E. Appetite and food consumption in the sea urchin Echinus esculantes L. Sarsia 1983, 68, 25–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudouresque, C.F.; Verlaque, M. Chapter 13 Ecology of Paracentrotus lividus. Dev. Aquac. Fish. Sci. 2007, 37, 243–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantzis, A.; Berthon, J.F.; Maggiore, F. Relation trophique entre les oursin Arbacia lixula et Paracentrotus lividus et le phytobenthos infralittoral superficiel de la baie de Port-Cros (Var, France). Sci. Rep. Port-Cros Natl. Park 1988, 14, 81–140. [Google Scholar]

- Basuyaux, O.; Blin, J.L. Use of maize as a food source for sea urchins in a recirculating rearing system. Aquac. Int. 1998, 6, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, N.; Zorita, I.; Costa, P.M.; Franco, J.; Larreta, J. Development of histopathological indices in the digestive gland and gonad of mussels: Integration with contamination levels and effects of confounding factors. Aquat. Toxicol. 2015, 162, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leite, C.; Russo, T.; Cuccaro, A.; Pinto, J.; Polese, G.; Soares, A.M.V.M.; Pretti, C.; Pereira, E.; Freitas, R. Can temperature rise change the impacts induced by e-waste on adults and sperm of Mytilus galloprovincialis? Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 902, 166085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, M.E.; Bentley, M.G. Fertilization success in marine invertebrates: The influence of gamete age. Biol. Bull. 2002, 202, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gago, J.; Martins, T.; Luís, O.J. Protein content and amino acid composition of eggs and endotrophic larvae from wild and captive fed sea urchin Paracentrotus lividus (Echinodermata: Echinoidea). Aquac. Res. 2016, 47, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciriminna, L.; Rakaj, A.; Signa, G.; Fianchini, A.; Mazzola, A.; Vizzini, S. Effects of sustainable feeds on Paracentrotus lividus broodstock: Assessment of egg nutritional composition and larval development. Aquaculture 2025, 611, 742968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (A) | |

| Flour proteins | 11.00% (including 5% from 99% pure Spirulina) |

| Fishmeal | 33.00% |

| Probiotics | 10.00% |

| Insect flour from Tenebrio molitor | 10.00% |

| Fish oil from salmon and cod | 12.00% |

| Yeast | 10.00% |

| Maize starch | 14.00% |

| (B) | |

| crude proteins | 41.50% |

| crude lipids | 30.00% |

| crude ash | 8.20% |

| crude fiber | 2.10% |

| starch | 14.00% |

| chlorine | 1.20% |

| calcium | 1.10% |

| sodium | 1.10% |

| phosphorus | 0.80% |

| Tissue | Histopathological Alteration | Weight (w) |

|---|---|---|

| Gonads | Lipofuscin aggregates | 1 |

| Detachment of acinal borders | 2 | |

| Enlargement of interstitial spaces among gametes | 1 |

| Control sea Urchin Weights (g) (Maize and Spinaches) | Treatment Sea Urchin Weights (g) (Protein Pellet) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beginning of the experiment | |||||

| Tank V1 | Tank V3 | Tank V5 | Tank V2 | Tank V4 | Tank V6 |

| 55.3 | 48.38 | 59.25 | 70.65 | 45.12 | 82.25 |

| 48.37 | 57.27 | 66.12 | 58.23 | 48.83 | 47.3 |

| 49.95 | 45.43 | 67.89 | 75.9 | 34.91 | 46.34 |

| 57.21 | 59.9 | 38.48 | 63.57 | 39.03 | 37.63 |

| 47.06 | 47.1 | 48.77 | 55.89 | 54.05 | 72.11 |

| 47.54 | 33.31 | 41.45 | 52.67 | 34.7 | 54.29 |

| 43.74 | 29.9 | 46.67 | 48.18 | 25.57 | 60.99 |

| 56.09 | 32.93 | 50.83 | 27.56 | 30.46 | 52.98 |

| 50.15 | 44.76 | 40.1 | 49.35 | 40.32 | 47.46 |

| Average: 50.23 (±14.48) g | Average: 48.7 (±9.4) g | ||||

| End of the experiment | |||||

| 50.1 | 35.2 | 42.2 | 71.2 | 53.9 | 44.7 |

| 54.5 | 49.6 | 54.2 | 50 | 33.4 | 62.5 |

| 47.3 | 48.7 | 50.4 | 55 | 436 | 54.7 |

| 51.7 | 53.7 | 65.3 | 48.2 | 31.9 | 44 |

| 59 | 59.1 | 68.5 | 28.6 | 43.9 | 49 |

| 58 | 46 | 58.8 | 54.7 | 39.2 | 57.2 |

| 46.6 | 35.3 | 41.5 | 52.2 | 25.1 | 40.1 |

| 46.1 | 31.7 | 48 | 70.9 | 38.6 | 72 |

| 47.8 | 31 | 41.8 | 64.5 | 34 | 80.5 |

| Average: 48.9 (±9.4) g | Average: 45.8 (±12.01) g | ||||

| Gonad Weight (g) Control | Gonad Weight (g) Treatment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Maize-Spinaches) | (Protein Pellet) | ||||

| Tank V1 | Tank V3 | Tank V5 | Tank V2 | Tank V4 | Tank V6 |

| 2.49 | 2.47 | 2.5 | 3.86 | 0.56 | 1.33 |

| 2.5 | 2.47 | 2.5 | 1.02 | 1.65 | 3.23 |

| 2.47 | 2.48 | 2.51 | 1.25 | 2.69 | 1.61 |

| 2.5 | 2.49 | 2.51 | 1.3 | 1.08 | 2.22 |

| 2.49 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 1.31 | 1.20 | 1.24 |

| 2.51 | 2.47 | 2.46 | 0.93 | 2.49 | 1.86 |

| 2.5 | 2.48 | 2.49 | 2.35 | 1.86 | 1.86 |

| 2.55 | 2.55 | 2.52 | 1.41 | 0.6 | 1.7 |

| 2.51 | 2.55 | 2.5 | 1.70 | n.d. | n.d. |

| Average: 1.69 (±0.78) g | Average: 2.50 (±0.02) g | ||||

| G.I. Control | G.I. Treatment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Maize-Spinaches) | (Protein Pellet) | ||||

| Tank V1 | Tank V3 | Tank V5 | Tank V2 | Tank V4 | Tank V6 |

| 3.50 | 4.58 | 5.59 | 7.71 | 1.61 | 3.16 |

| 5.00 | 7.40 | 4.00 | 1.87 | 3.33 | 5.97 |

| 4.49 | 5.69 | 4.59 | 2.66 | 5.53 | 3.2 |

| 5.19 | 7.81 | 5.70 | 2.51 | 2.02 | 3.41 |

| 8.71 | 5.69 | 5.10 | 2.22 | 2.03 | 1.81 |

| 4.59 | 6.30 | 4.30 | 1.61 | 5.42 | 3.16 |

| 4.79 | 9.88 | 6.21 | 5.05 | 5.27 | 4.48 |

| 3.60 | 6.61 | 3.50 | 3.08 | 1.9 | 3.54 |

| 3.89 | 7.50 | 3.11 | 3.56 | n.d. | n.d. |

| Average: 3.44 (±1.60) | Average: 5.46 (±1.68) | ||||

| NH4 | NO2 | NO3 | PO4 | O2 | Salinity | T | pH | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.53 | 0.00 | 10.03 | 0.24 | 5.31 | 40.00 | 17.73 | 7.70 |

| 1 | 1.73 | 0.00 | 9.17 | 0.24 | 5.70 | 41.33 | 17.33 | 7.74 |

| 3 | 1.73 | 0.00 | 11.27 | 0.24 | 5.90 | 41.00 | 16.73 | 7.88 |

| 7 | 2.27 | 0.00 | 6.73 | 0.19 | 5.97 | 40.33 | 16.40 | 7.94 |

| 9 | 2.90 | 0.00 | 6.73 | 0.19 | 5.78 | 39.83 | 17.03 | 7.84 |

| 11 | 2.90 | 0.00 | 6.73 | 0.16 | 5.21 | 40.33 | 17.65 | 7.63 |

| 16 | 2.77 | 0.03 | 6.73 | 0.31 | 3.83 | 41.00 | 17.40 | 7.84 |

| 18 | 2.63 | 0.04 | 6.73 | 0.31 | 5.52 | 40.67 | 17.53 | 7.89 |

| 21 | 3.07 | 0.03 | 6.73 | 0.39 | 5.49 | 40.67 | 17.63 | 7.77 |

| 23 | 3.07 | 0.03 | 6.73 | 0.39 | 5.07 | 40.67 | 17.67 | 7.88 |

| 25 | 3.37 | 0.05 | 6.73 | 0.48 | 5.46 | 4067 | 17.60 | 7.91 |

| 28 | 2.95 | 0.05 | 3.90 | 0.34 | 5.32 | 40.00 | 17.85 | 7.90 |

| NH4 | NO2 | NO3 | PO4 | O2 | Salinity | T | pH | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.74 | 0.00 | 9.27 | 0.09 | 5.08 | 40.00 | 17.53 | 7.70 |

| 1 | 0.84 | 0.00 | 9.33 | 0.09 | 5.56 | 40.33 | 17.13 | 7.80 |

| 3 | 1.97 | 0.00 | 11.93 | 0.09 | 5.90 | 40.00 | 16.63 | 7.95 |

| 7 | 0.77 | 0.00 | 11.10 | 0.09 | 6.02 | 40.00 | 16.53 | 8.00 |

| 9 | 0.77 | 0.00 | 11.10 | 0.09 | 5.11 | 39.50 | 17.43 | 7.75 |

| 11 | 2.44 | 0.01 | 11.10 | 0.15 | 5.21 | 40.67 | 17.50 | 7.72 |

| 16 | 3.07 | 0.03 | 11.03 | 0.15 | 5.55 | 41.00 | 17.73 | 8.03 |

| 18 | 3.10 | 0.03 | 11.03 | 0.15 | 5.53 | 41.33 | 17.67 | 7.89 |

| 21 | 2.33 | 0.01 | 11.10 | 0.17 | 5.18 | 41.33 | 17.63 | 7.85 |

| 23 | 2.33 | 0.01 | 11.10 | 0.17 | 5.39 | 40.67 | 17.53 | 7.93 |

| 25 | 2.57 | 0.01 | 11.10 | 0.21 | 5.28 | 40.33 | 17.53 | 7.88 |

| 28 | 2.90 | 0.01 | 7.20 | 0.25 | 5.05 | 40.00 | 17.80 | 7.70 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pinto, B.; Gharbi, M.; Federico, S.; Glaviano, F.; Tentoni, E.; Russo, T.; Cosmo, A.D.; Polese, G.; Costantini, M.; Zupo, V. Formulated Diets Drive Gonadal Maturity but Reduce Larval Success in Paracentrotus lividus. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2026, 14, 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010031

Pinto B, Gharbi M, Federico S, Glaviano F, Tentoni E, Russo T, Cosmo AD, Polese G, Costantini M, Zupo V. Formulated Diets Drive Gonadal Maturity but Reduce Larval Success in Paracentrotus lividus. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2026; 14(1):31. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010031

Chicago/Turabian StylePinto, Bruno, Maissa Gharbi, Serena Federico, Francesca Glaviano, Enea Tentoni, Tania Russo, Anna Di Cosmo, Gianluca Polese, Maria Costantini, and Valerio Zupo. 2026. "Formulated Diets Drive Gonadal Maturity but Reduce Larval Success in Paracentrotus lividus" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 14, no. 1: 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010031

APA StylePinto, B., Gharbi, M., Federico, S., Glaviano, F., Tentoni, E., Russo, T., Cosmo, A. D., Polese, G., Costantini, M., & Zupo, V. (2026). Formulated Diets Drive Gonadal Maturity but Reduce Larval Success in Paracentrotus lividus. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 14(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010031