F3M: A Frequency-Domain Feature Fusion Module for Robust Underwater Object Detection

Abstract

1. Introduction

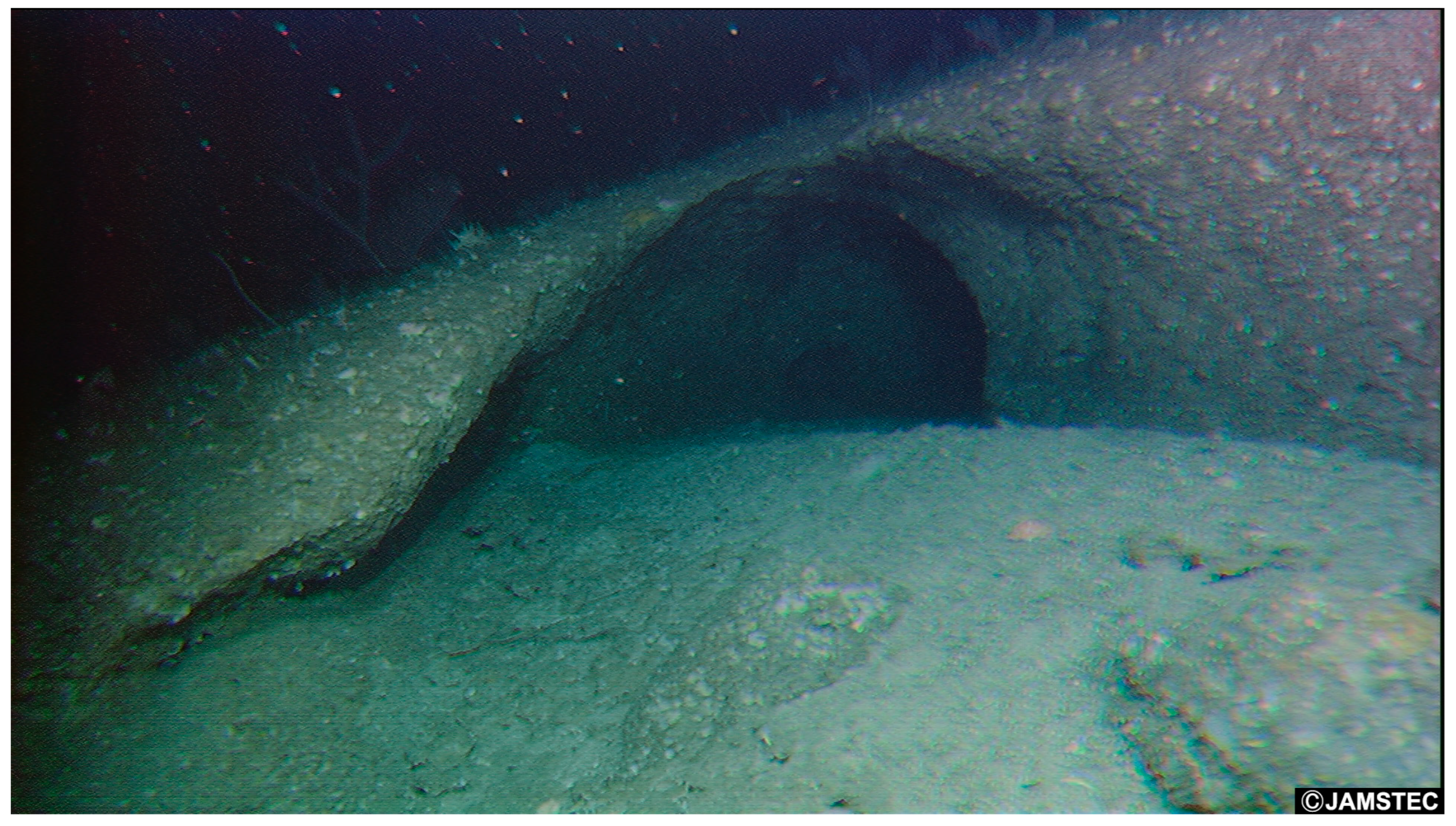

1.1. Research Background and Significance

1.2. Challenges of Underwater Object Detection

1.3. Progress in Modern Detection Methods

1.4. Motivation for Frequency-Domain Modeling in Underwater Detection

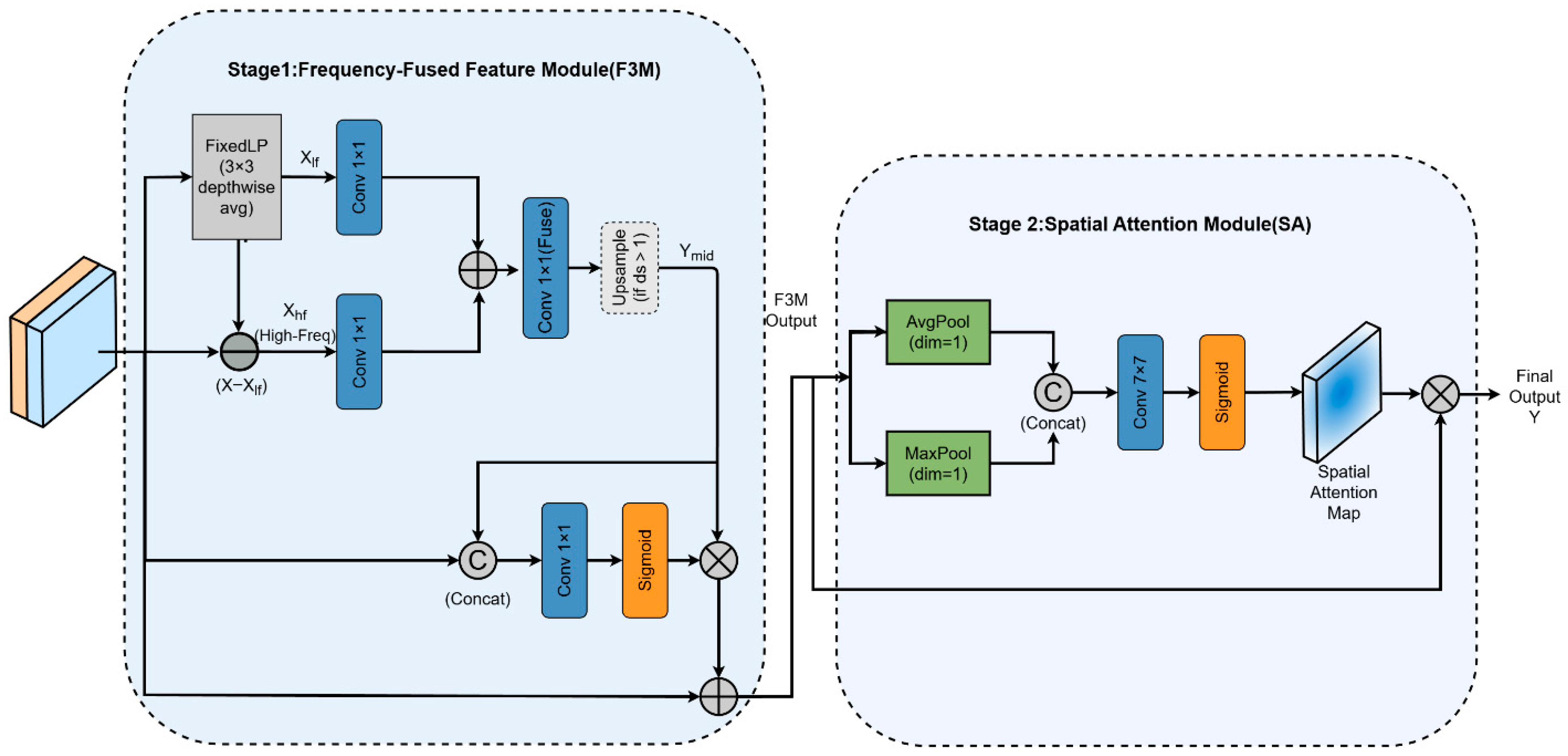

2. Frequency-Domain Feature Fusion Module (F3M)

2.1. F3M Module: Design and Architecture

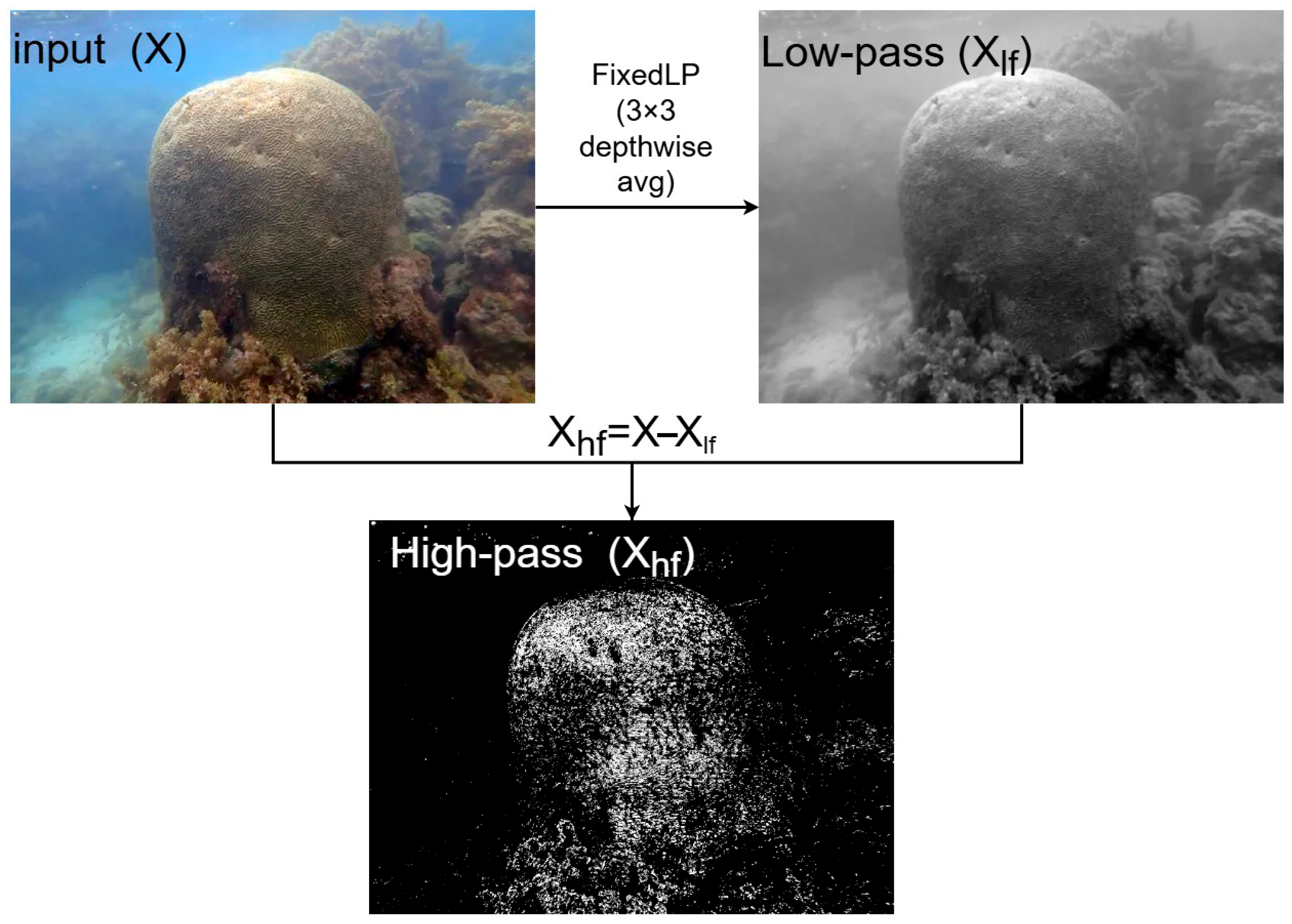

2.1.1. Separate (Frequency Decomposition)

2.1.2. Project (Adaptive Feature Projection)

2.1.3. Fuse (Feature Fusion + Gating)

2.1.4. Spatial Attention Extension (F3MWithSA)

2.2. Baseline Architectures and Integration Strategy

2.2.1. One-Stage CNN: YOLO11

- Architecture Overview.

- 2.

- Integration Strategy.

- Stem Stage (Early Insertion): We replace the second convolutional block (immediately following the first spatial downsampling) with F3MWithSA. At this high-resolution stage, feature maps are rich in primitive textures and edges. F3M acts here as a frequency-based “cleaner,” decoupling the dominant illumination haze (LF) from the attenuated structural details (HF) before they are compressed by subsequent layers.

- Neck Stage (Late Insertion): We insert a lightweight F3M (without spatial attention to save GFLOPs) before the Spatial Pyramid Pooling (SPPF) module. Here, features are semantically rich but spatially coarse; F3M helps reinject high-frequency boundary cues that may have been smoothed out during deep aggregation.

- 3.

- Overall Architecture Configuration.

- Early Stage (Stem): We employ the full F3MWithSA module with a higher channel reduction ratio (r = 0.33) and the gating mechanism enabled (Gate = T). This maximizes the preservation of fine-grained textures when the feature map is large.

- Late Stage (Pre-SPPF): We use the standard F3M (without spatial attention) and a lower reduction ratio (r = 0.125) with the gate disabled (Gate = F). This “lite” configuration reduces computational overhead (GFLOPs) while still providing necessary frequency-domain correction at the deepest layer.

2.2.2. Real-Time Transformer: RT-DETR

- Architecture Overview

- 2.

- Integration Strategy

- Rationale: Small polyps and fine texture details are encoded earliest in the network. Once these high-frequency cues are lost due to downsampling, the Transformer encoder cannot recover them. By placing F3M early, we refine the “tokens” before they enter the heavy attention stack, improving input quality without altering the computational cost of the Transformer encoder or decoder.

- Configuration: To maintain real-time performance, we avoid adding F3M to the deeper, low-resolution stages (P4, P5). The rest of the pipeline, including the hybrid encoder and the detection head, remains unmodified.

3. Experiments and Analysis

3.1. Dataset

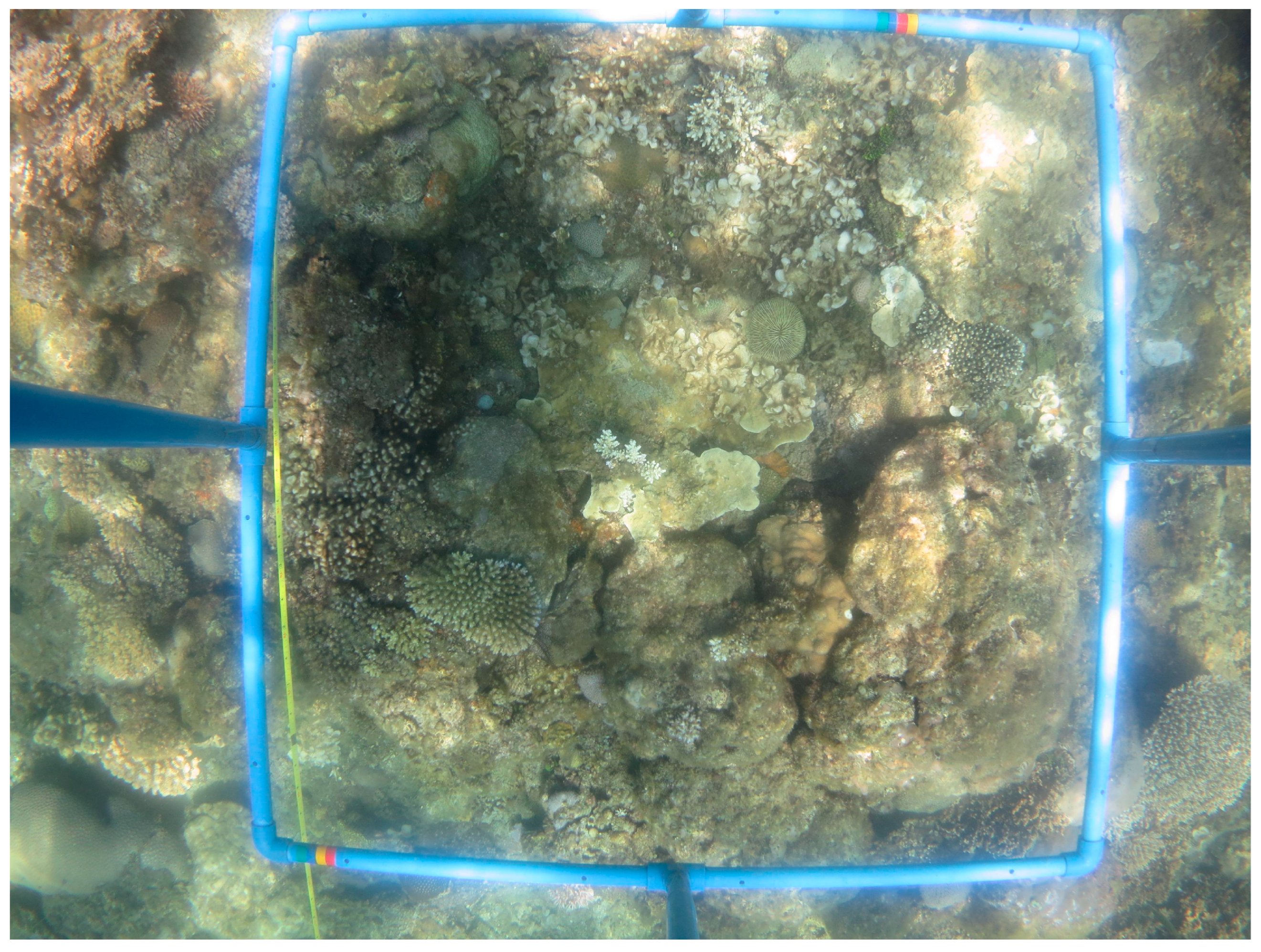

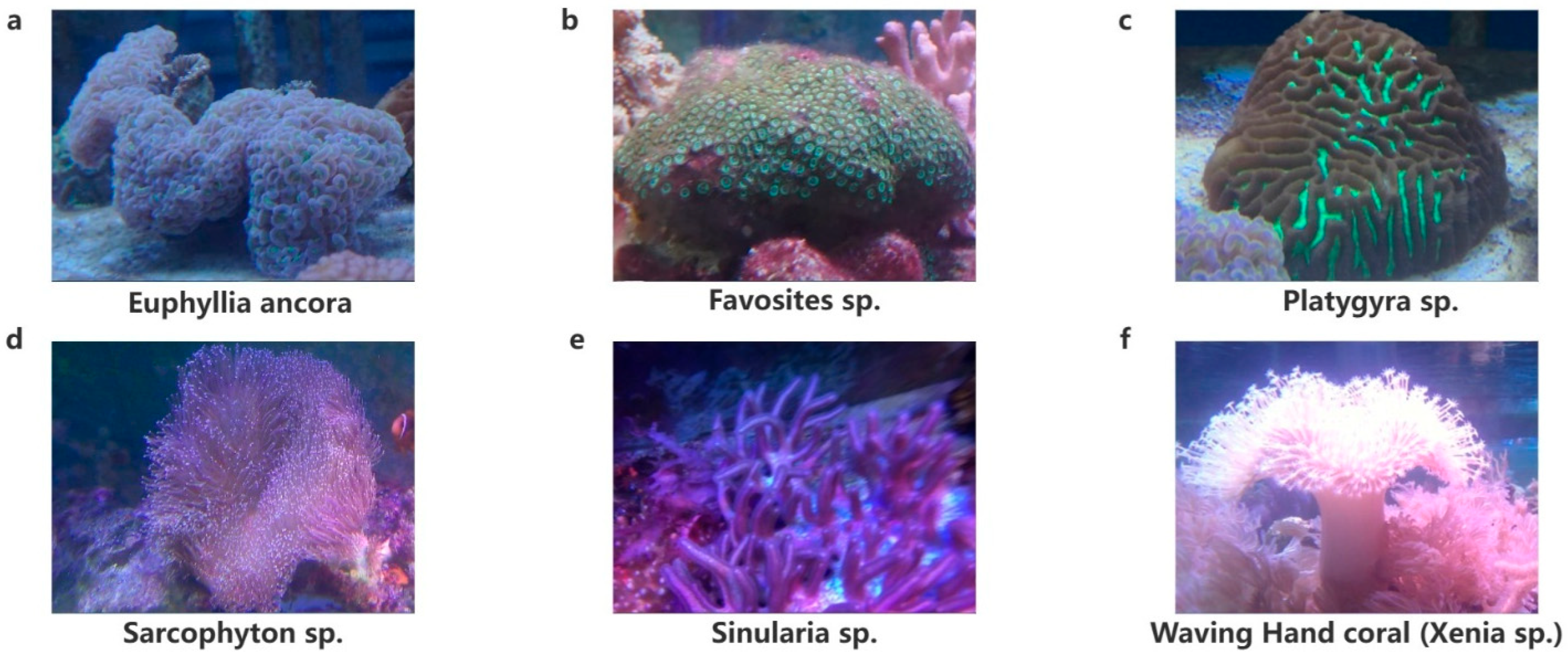

3.1.1. SCoralDet Dataset

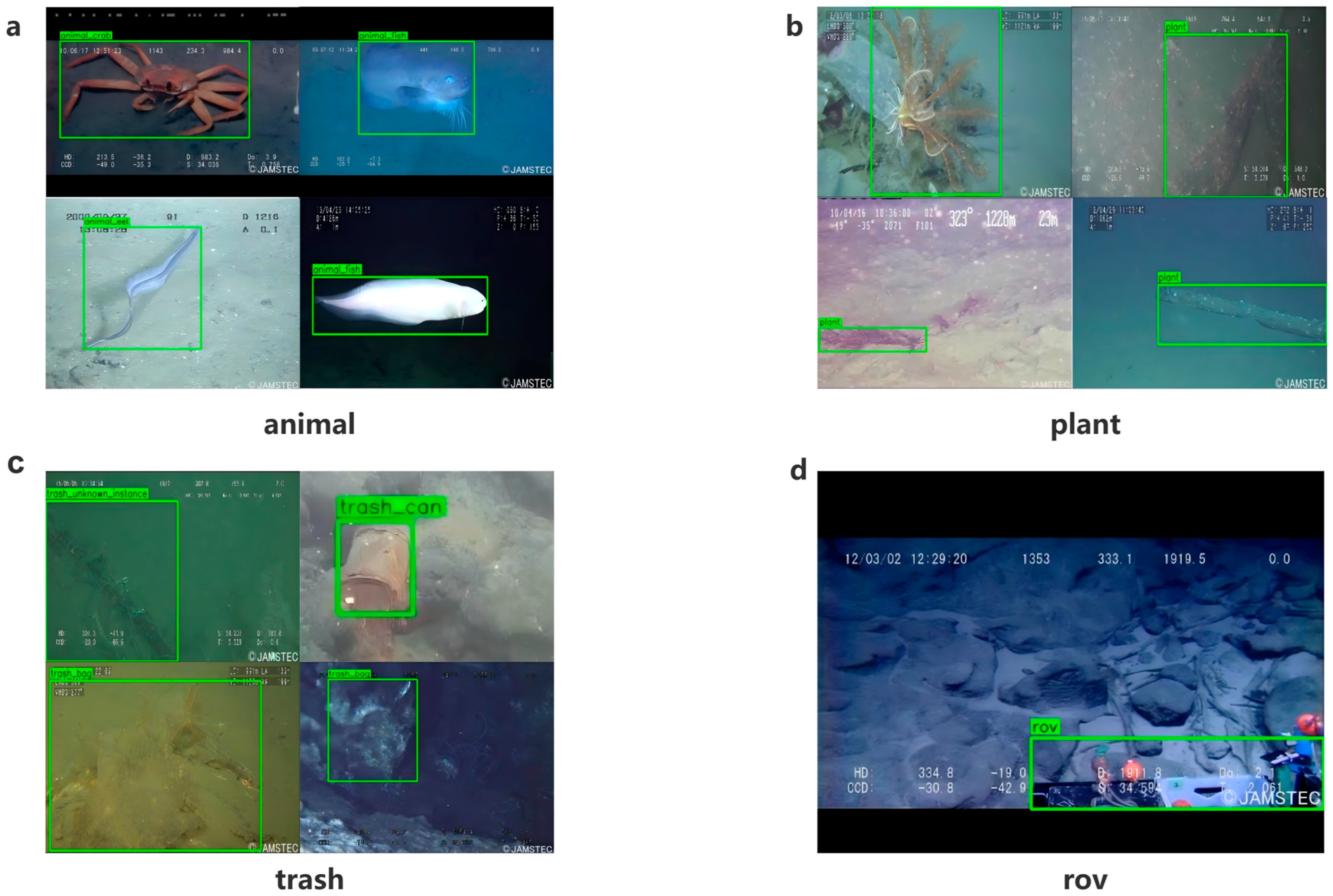

3.1.2. TrashCan Dataset

3.2. Experimental Details

3.3. Evaluation Metrics

- GFLOPs (floating-point operations per forward pass)

- 2.

- Precision and Recall

- 3.

- mAP50 (mean Average Precision at IoU = 0.5)

- 4.

- mAP50–95 (mean AP across thresholds)

3.4. Comparison with Existing Detectors on the SCoralDet Dataset

- Comparison with Specialized Underwater Architectures. Beyond general detectors, we benchmark against state-of-the-art architectures specifically engineered for the underwater domain to validate domain adaptability. LUOD-YOLO [41] enhances YOLOv8 with dynamic feature fusion and dual-path rearrangement to mitigate underwater distortion. Our previously published S2-YOLO [42] optimizes marine debris recognition through improved spatial-to-depth convolutions. We also compare against SCoralDet [25], a YOLOv10-based detector explicitly customized for soft-coral detection tasks.

- Construction of the Frequency-Domain Baseline. Crucially, to strictly evaluate the proposed spatial approximation against rigorous frequency decomposition, we constructed a heavy-weight frequency baseline, denoted as YOLO11n-WFU. Drawing inspiration from the UGMB algorithm [43]—which proposes a multi-scale architecture by embedding defect-specific enhancement modules into dense residual blocks—we adopted a parallel integration strategy. Specifically, we replaced the standard Bottleneck unit within the YOLO11n’s C3k2 module with the Wavelet Feature Upgrade (WFU) block [39]. This design enables the network to perform explicit wavelet-based frequency decomposition during deep feature extraction, facilitating a direct comparison between “heavy-weight frequency transforms” and our “lightweight F3M” without altering the macro-topology of the host network.

3.5. Ablation Study of F3M Placement and Attention

- Baseline: The vanilla YOLO11n model.

- onlyF3M (Deep-only): Integrating the standard F3M (without spatial attention) solely at the neck stage (pre-SPPF) to enhance semantic aggregation.

- onlyF3MWithSA (Stem-only): Integrating F3MWithSA solely at the early stem stage to denoise high-resolution features.

- F3M(Dual-site): The proposed full architecture employing both the early attention-enhanced stem and the deep frequency-aware neck.

3.6. General Applicability of F3M Across Detector Architectures

3.7. Cross-Dataset Generalization on the TrashCan Dataset

4. Conclusions

- Hardware Deployment and Optimization: Although our theoretical GFLOPs and parameter counts indicate suitability for edge devices, we plan to deploy and test the F3M-YOLO architecture on physical underwater platforms (e.g., Jetson Orin or FPGA-based AUVs) to evaluate real-world inference latency and energy consumption under varying battery constraints.

- Learnable Frequency Decomposition: Currently, F3M utilizes fixed pooling operators for frequency separation. Future iterations could explore learnable spectral filters or adaptive wavelet transforms to dynamically adjust the frequency cutoff based on the turbidity levels of different water bodies.

- Video-Based Detection: Given the dynamic nature of marine environments (e.g., swaying corals, moving fish), extending F3M to utilize temporal information in video streams could further suppress background noise and improve the consistency of detection tracks.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moberg, F.; Folke, C. Ecological goods and services of coral reef ecosystems. Ecol. Econ. 1999, 29, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souter, D.; Planes, S.; Wicelowski, C.; Obura, D.; Staub, F. (Eds.) Status of Coral Reefs of the World: 2020; GCRMN/UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrario, F.; Beck, M.W.; Storlazzi, C.D.; Micheli, F.; Shepard, C.C.; Airoldi, L. The effectiveness of coral reefs for coastal hazard risk reduction and adaptation. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spalding, M.D.; Burke, L.; Wood, S.A.; Ashpole, J.; Hutchison, J.; zu Ermgassen, P. Mapping the global value and distribution of coral reef tourism. Mar. Policy 2017, 82, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, K.; He, S.; Zhan, P. Inevitable global coral reef decline under climate change-induced thermal stresses. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoegh-Guldberg, O.; Mumby, P.J.; Hooten, A.J.; Steneck, R.S.; Greenfield, P.; Gomez, E.; Harvell, C.D.; Sale, P.F.; Edwards, A.J.; Caldeira, K.; et al. Coral Reefs Under Rapid Climate Change and Ocean Acidification. Science 2007, 318, 1737–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoegh-Guldberg, O. Coral reef ecosystems under climate change and ocean acidification. Front. Mar. Sci. 2017, 4, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, J.F.; Selig, E.R. Regional Decline of Coral Cover in the Indo-Pacific: Timing, Extent, and Subregional Comparisons. PLoS ONE 2007, 2, e711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beijbom, O.; Edmunds, P.J.; Roelfsema, C.; Smith, J.; Kline, D.I.; Neal, B.P.; Dunlap, M.J.; Moriarty, V.; Fan, T.Y.; Tan, C.J.; et al. Towards Automated Annotation of Benthic Survey Images: Variability of Human Experts and Operational Modes of Automation. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0130312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raphael, A.; Dubinsky, Z.; Iluz, D.; Benichou, J.I.C.; Netanyahu, N.S. Deep neural network recognition of shallow water corals in the Gulf of Eilat (Aqaba). Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Wang, H.; Chen, W.; Wang, P.; Liang, Q.; Qin, X. A novel edge-feature attention fusion framework for underwater image enhancement. Front. Mar. Sci. 2025, 12, 1555286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soom, J.; Pattanaik, V.; Leier, M.; Tuhtan, J.A. Environmentally adaptive fish or no-fish classification for river video fish counters using high-performance desktop and embedded hardware. Ecol. Inform. 2022, 72, 101817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Liu, R.; Fan, X.; Chen, P.; Fu, H.; Yuan, W.; Zhu, M.; Luo, Z. Rethinking general underwater object detection: Datasets, challenges, and solutions. Neurocomputing 2023, 517, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Fan, X.; Zhu, M.; Hou, M.; Luo, Z. Real-World Underwater Enhancement: Challenges, Benchmarks, and Solutions Under Natural Light. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2020, 30, 4861–4875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditria, E.M.; Lopez-Marcano, S.; Sievers, M.; Jinks, E.L.; Brown, C.J.; Connolly, R.M. Automating the analysis of fish abundance using object detection: Optimizing animal ecology with deep learning. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buda, M.; Maki, A.; Mazurowski, M.A. A systematic study of the class imbalance problem in convolutional neural networks. Neural Netw. 2018, 106, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirzaei, B.; Nezamabadi-pour, H.; Raoof, A.; Derakhshani, R. Small Object Detection and Tracking: A Comprehensive Review. Sensors 2023, 23, 6887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, J.; Cui, H.; Huang, Y.; Li, T.; Wu, C.; Zhang, K. A review of occluded objects detection in real complex scenarios for autonomous driving. Green Energy Intell. Transp. 2023, 2, 100092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Rivero, M.; Beijbom, O.; Garcia, R.; Rodriguez-Ramirez, A.; Bryant, D.E.; Ganase, A.; Gonzalez-Marrero, Y.; Herrera-Reveles, A.; Kennedy, E.V.; Kim, C.J.; et al. Monitoring of coral reefs using artificial intelligence: A feasible and cost-effective approach. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shorten, C.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M. A survey on image data augmentation for deep learning. J. Big Data 2019, 6, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, A.; Bennamoun, M.; An, S.; Sohel, F.; Boussaid, F.; Hovey, R.; Kendrick, G.; Fisher, R.B. Coral classification with hybrid feature representations. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP 2016), Phoenix, AZ, USA, 25–28 September 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 519–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deo, R.; John, C.M.; Zhang, C.; Whitton, K.; Salles, T.; Webster, J.M.; Chandra, R. Deepdive: Leveraging Pre-trained Deep Learning for Deep-Sea ROV Biota Identification in the Great Barrier Reef. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2016), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Liao, L.; Xie, X.; Yuan, H. SCoralDet: Efficient real-time underwater soft coral detection with YOLO. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 85, 102937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Zhang, X.; Mo, Y. A lightweight underwater detector enhanced by Attention mechanism, GSConv and WIoU on YOLOv8. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 25797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Yun, Q.; Yuan, F.; Ren, X.; Jin, J.; Zhu, X. YOLOv7-CHS: An emerging model for underwater object detection. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Shen, C.; Chen, H.; He, T. FCOS: Fully Convolutional One-Stage Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV 2019), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 9626–9635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, K.; Bai, S.; Xie, L.; Qi, H.; Huang, Q.; Tian, Q. CenterNet: Keypoint Triplets for Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV 2019), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 6568–6577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carion, N.; Massa, F.; Synnaeve, G.; Usunier, N.; Kirillov, A.; Zagoruyko, S. End-to-End Object Detection with Transformers. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2020, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Vedaldi, A., Bischof, H., Brox, T., Frahm, J.M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Su, W.; Li, L.; Wang, X.; Dai, J. Deformable DETR: Deformable transformers for end-to-end object detection. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2021), Virtual, 3–7 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Lv, W.; Xu, S.; Wei, J.; Wang, G.; Dang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J. DETRs Beat YOLOs on Real-time Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2024), Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 16965–16974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Fan, H.; Xu, B.; Yan, Z.; Kalantidis, Y.; Rohrbach, M.; Shuicheng, Y.; Feng, J. Drop an Octave: Reducing Spatial Redundancy in Convolutional Neural Networks With Octave Convolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV 2019), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 3434–3443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Zhang, P.; Wu, F.; Li, X. FcaNet: Frequency Channel Attention Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV 2021), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 763–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Soatto, S. FDA: Fourier Domain Adaptation for Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2020), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 4084–4094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, L.; Jiang, B.; Mu, Y. Fast Fourier Convolution. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS 33, 34th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2020), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 6–12 December 2020; pp. 4479–4491. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Shen, L.; Guo, S.; Lai, Z. WaveCNet: Wavelet Integrated CNNs to Suppress Aliasing Effect for Noise-Robust Image Classification. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2021, 30, 7074–7089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolter, M.; Garcke, J. Adaptive wavelet pooling for convolutional neural networks. Proc. Mach. Learn. Res. 2021, 130, 1936–1944. Available online: https://proceedings.mlr.press/v130/wolter21a.html (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Li, W.; Guo, H.; Liu, X.; Liang, K.; Hu, J.; Ma, Z.; Guo, J. Efficient Face Super-Resolution via Wavelet-based Feature Enhancement Network. In Proceedings of the ACM Multimedia (MM 2024), Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 28 October–1 November 2024; pp. 4515–4523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kweon, I.S. CBAM: Convolutional Block Attention Module. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, C.; Pan, W. LUOD-YOLO: A lightweight underwater object detection model based on dynamic feature fusion, dual path rearrangement and cross-scale integration. J. Real-Time Image Process. 2025, 22, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wang, H.; Wang, W.; Zhang, K.; Ye, B. An Improved YOLOv8n Based Marine Debris Recognition Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Computer Graphics, Image and Virtualization (ICCGIV), Johor Bahru, Malaysia, 6–8 June 2025; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Tian, C.; Zhang, A.; Liu, Y.; Gao, G.; Zhuang, Z.; Yin, T.; Zhang, N. A Bridge Defect Detection Algorithm Based on UGMB Multi-Scale Feature Extraction and Fusion. Symmetry 2025, 17, 1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | Precision | Recall | mAP50 | mAP50–95 | Parameters(M) | GFLOPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv8n | 0.787 | 0.696 | 0.760 | 0.499 | 3.01 | 8.1 |

| LUOD-YOLO (based on YOLOv8) [41] | 0.849 | 0.728 | 0.779 | 0.518 | 1.63 | 5.9 |

| S2-YOLO (based on YOLOv8) [42] | 0.869 | 0.679 | 0.764 | 0.516 | 2.74 | 6.9 |

| SCoralDet (based on YOLOv10) [25] | 0.779 | 0.650 | 0.724 | 0.483 | 3.38 | 8.8 |

| YOLO11n-WFU | 0.761 | 0.661 | 0.761 | 0.475 | 3.60 | 8.1 |

| YOLO11n | 0.763 | 0.686 | 0.762 | 0.513 | 2.58 | 6.3 |

| YOLO12n | 0.859 | 0.634 | 0.738 | 0.513 | 2.56 | 6.3 |

| RT-DETR-n | 0.751 | 0.691 | 0.736 | 0.514 | 9.14 | 19.8 |

| RT-DETR-n-F3M | 0.787 | 0.701 | 0.769 | 0.532 | 9.22 | 21.3 |

| YOLO11n-F3M | 0.861 | 0.708 | 0.797 | 0.539 | 2.61 | 6.5 |

| Model | Precision | Recall | mAP50 | mAP50–95 | GFLOPs | Stem F3MWithSA | Deep F3M (SPPF-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLO11n (Baseline) | 0.763 | 0.686 | 0.762 | 0.513 | 6.3 | No | No |

| YOLO11n-onlyF3M | 0.843 | 0.719 | 0.776 | 0.517 | 6.3 | No | Yes |

| YOLO11n-onlyF3MWithSA | 0.850 | 0.678 | 0.769 | 0.522 | 6.5 | Yes | No |

| YOLO11n-F3M (Dual-site) | 0.861 | 0.708 | 0.797 | 0.539 | 6.5 | Yes | Yes |

| Category | YOLO11 (Baseline) | onlyF3M (Deep-Only) | onlyF3MWithSA (Stem-Only) | F3M (Dual-Site) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Euphyllia ancora (Tentacles/High-freq) | 0.552 | 0.559 | 0.548 | 0.601 |

| Favosites sp. (Dense pattern) | 0.543 | 0.537 | 0.552 | 0.559 |

| Platygyra sp. (Ridge texture) | 0.667 | 0.671 | 0.705 | 0.685 |

| Sarcophyton sp. (Fine polyps) | 0.516 | 0.538 | 0.547 | 0.587 |

| Sinularia sp. (Low contrast) | 0.382 | 0.367 | 0.370 | 0.397 |

| Waving Hand (Dynamic/Blur) | 0.419 | 0.428 | 0.413 | 0.407 |

| Model | Precision | Recall | mAP50 | mAP50–95 | Parameters (M) | GFLOPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv8n | 0.787 | 0.696 | 0.760 | 0.499 | 3.01 | 8.1 |

| YOLOv8n-F3M | 0.852 | 0.634 | 0.744 | 0.502 | 3.04 | 8.3 |

| RT-DETR-n | 0.751 | 0.691 | 0.736 | 0.514 | 9.14 | 19.8 |

| RT-DETR-n-F3M | 0.787 | 0.701 | 0.769 | 0.532 | 9.22 | 21.3 |

| YOLO11n | 0.763 | 0.686 | 0.762 | 0.513 | 2.58 | 6.3 |

| YOLO11n-F3M | 0.861 | 0.708 | 0.797 | 0.539 | 2.61 | 6.5 |

| Model | Precision | Recall | mAP50 | mAP50–95 | Parameters (M) | GFLOPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv8n | 0.885 | 0.870 | 0.908 | 0.679 | 3.01 | 8.1 |

| LUOD-YOLO (based on YOLOv8) [41] | 0.885 | 0.828 | 0.886 | 0.663 | 1.63 | 5.9 |

| S2-YOLO (based on YOLOv8) [42] | 0.873 | 0.870 | 0.904 | 0.689 | 2.74 | 6.9 |

| SCoralDet (based on YOLOv10) [25] | 0.868 | 0.823 | 0.879 | 0.676 | 3.38 | 8.8 |

| YOLO11n-WFU | 0.849 | 0.873 | 0.902 | 0.676 | 3.60 | 8.1 |

| YOLO11n | 0.885 | 0.851 | 0.892 | 0.673 | 2.58 | 6.3 |

| YOLO12n | 0.893 | 0.827 | 0.885 | 0.671 | 2.56 | 6.3 |

| RT-DETR-n | 0.865 | 0.822 | 0.878 | 0.666 | 9.14 | 19.8 |

| YOLO11n-F3M | 0.895 | 0.844 | 0.908 | 0.679 | 2.61 | 6.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, T.; Wang, H.; Wang, W.; Zhang, K.; Ye, B.; Dong, H. F3M: A Frequency-Domain Feature Fusion Module for Robust Underwater Object Detection. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2026, 14, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010020

Wang T, Wang H, Wang W, Zhang K, Ye B, Dong H. F3M: A Frequency-Domain Feature Fusion Module for Robust Underwater Object Detection. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2026; 14(1):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010020

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Tianyi, Haifeng Wang, Wenbin Wang, Kun Zhang, Baojiang Ye, and Huilin Dong. 2026. "F3M: A Frequency-Domain Feature Fusion Module for Robust Underwater Object Detection" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 14, no. 1: 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010020

APA StyleWang, T., Wang, H., Wang, W., Zhang, K., Ye, B., & Dong, H. (2026). F3M: A Frequency-Domain Feature Fusion Module for Robust Underwater Object Detection. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 14(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010020