Optimal SAR and Oil Spill Recovery Vessel Concept for Baltic Sea Operations

Abstract

1. Analysis of Factors That Limit Search, Rescue, and Pollution Response Operations

1.1. Analysis of Hydrometeorological Conditions

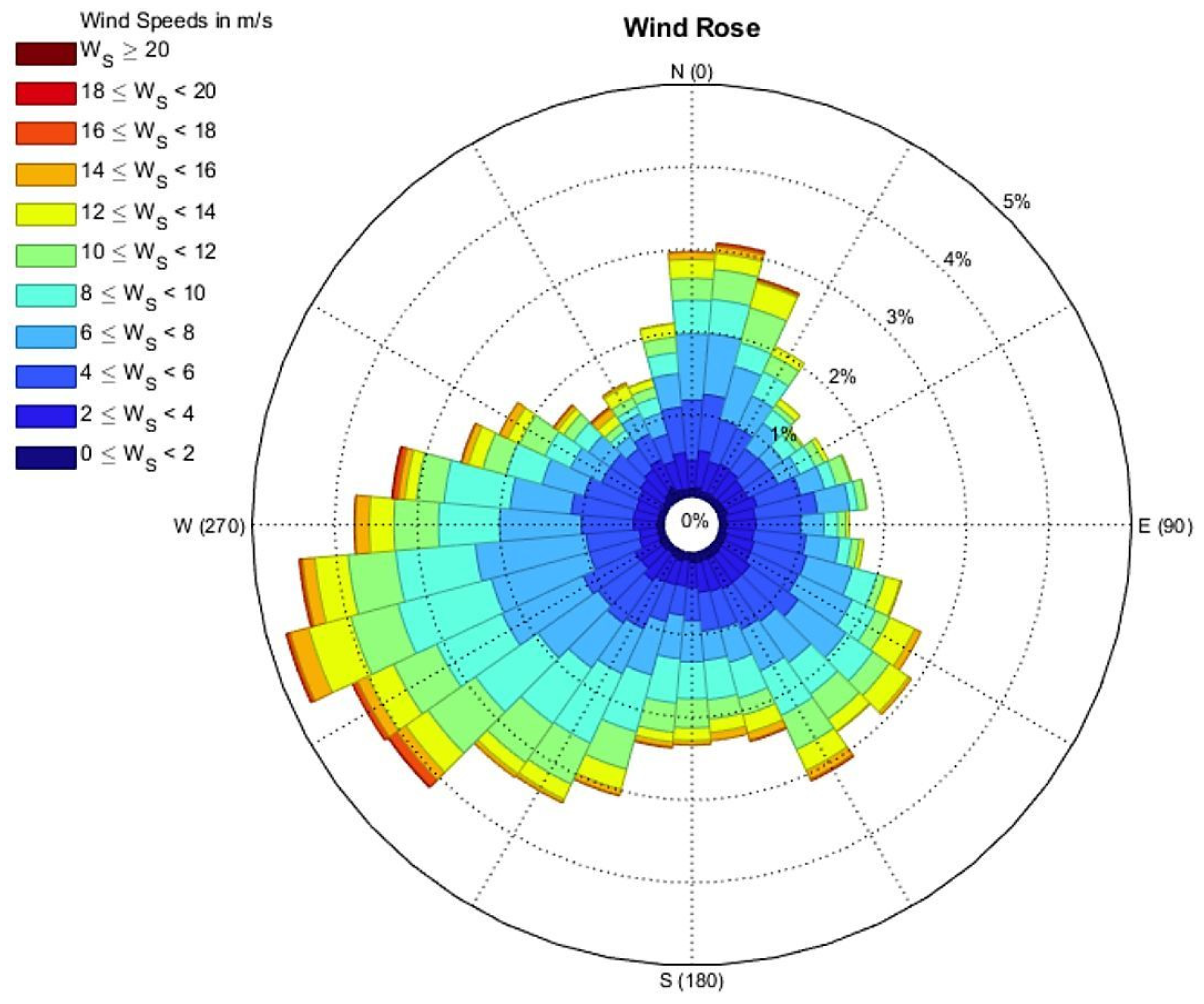

1.1.1. Analysis of Wind Speed

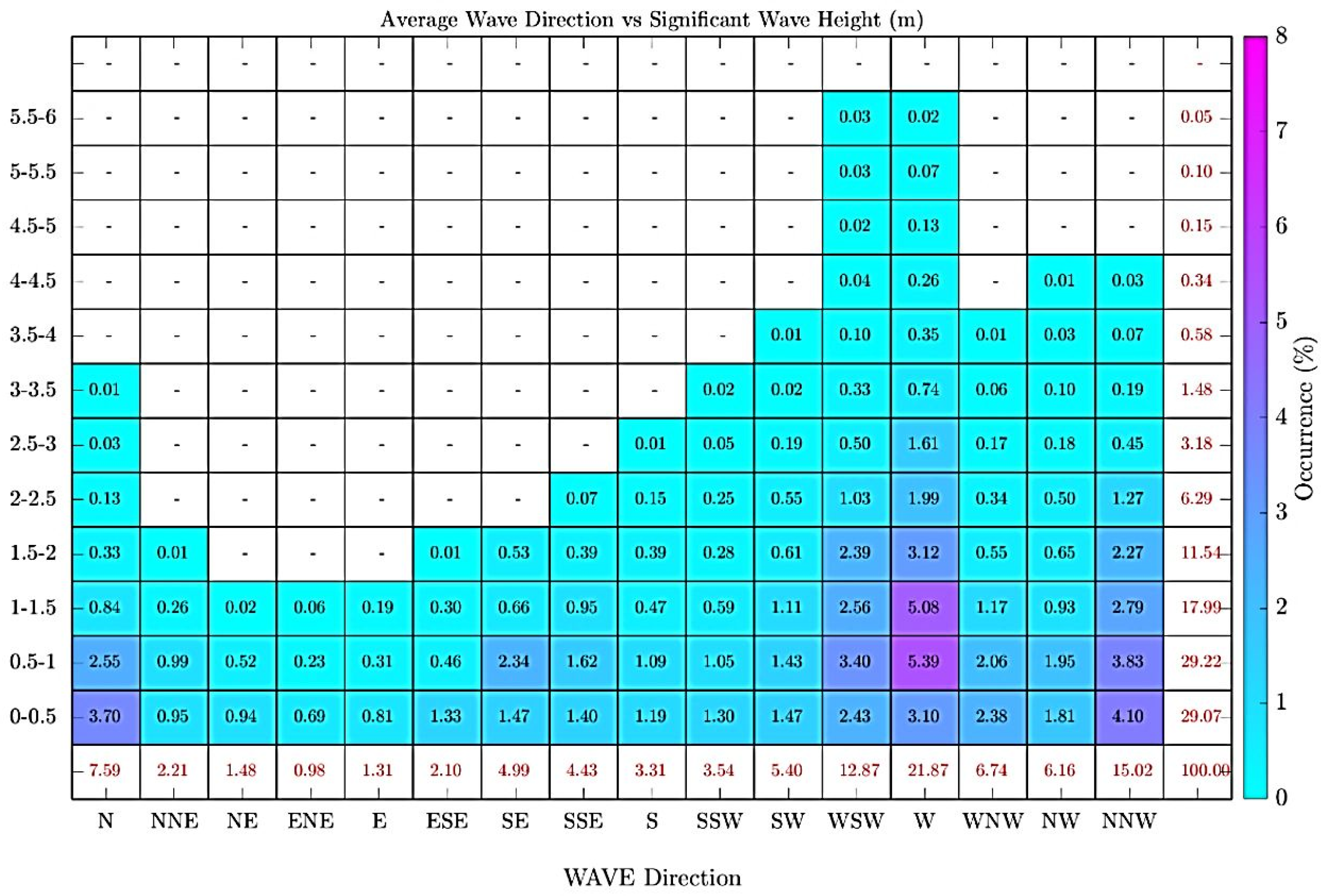

1.1.2. Analysis of Wave Height

1.1.3. Analysis of Current Strength

1.1.4. Analysis of Ice Thickness and Icing

1.1.5. Fog Data Analysis

1.2. Analysis of Requirements for Search, Rescue, and Pollution Response Operations

1.2.1. Analysis of Vessel Readiness for SAROR Operations and Relevant Legislation

- the SARORV must depart for the incident site within 2 h;

- it must reach any location of pollution incident within the national maritime area within 6 h of departure;

- national pollution response units must collect spilled pollutants using mechanical means within 48 h.

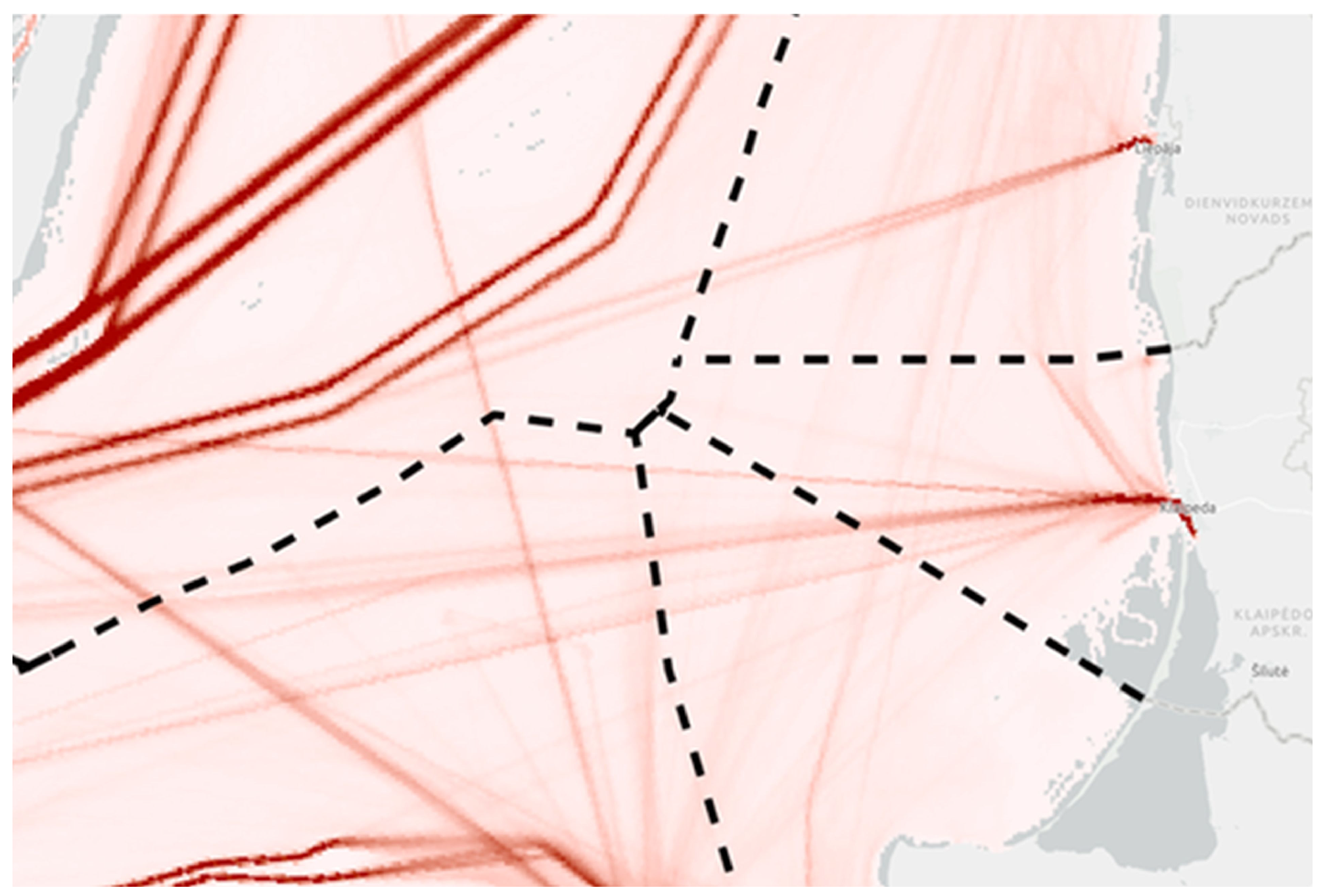

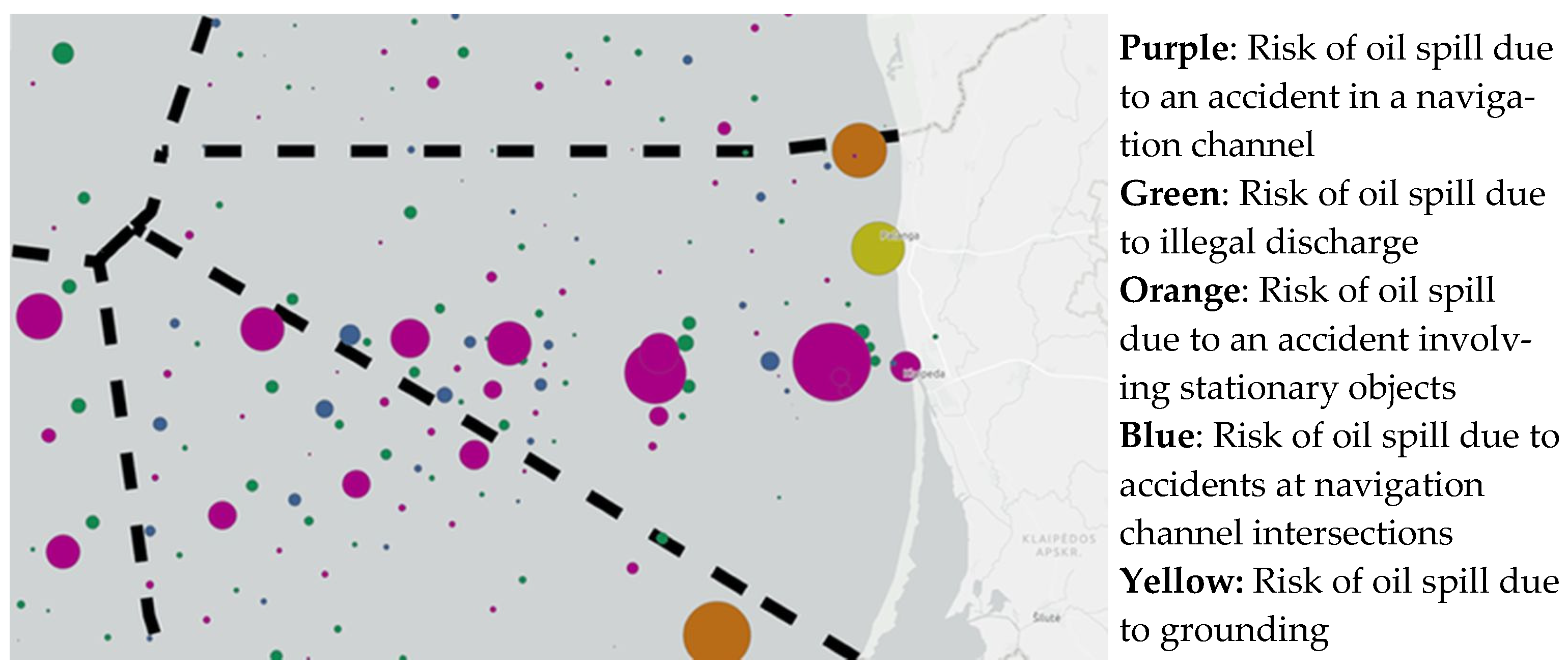

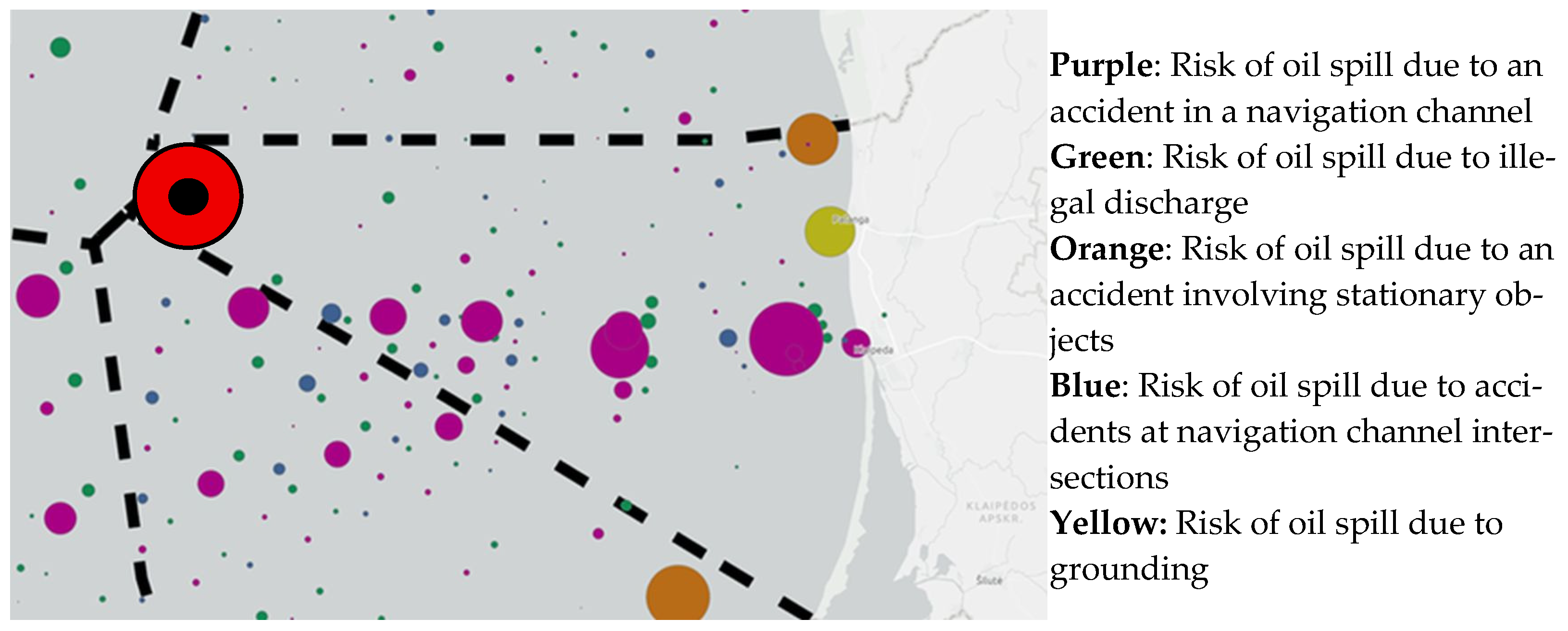

1.2.2. Traffic Analysis in the Area of Responsibility of the Republic of Lithuania

1.2.3. Crew Composition Analysis

- Captain—overall command of the vessel and operations; responsible for navigation and decision-making;

- Chief Officer—assists the captain; manages deck operations and coordinates rescue activities;

- Second Officer—responsible for navigation, communications, and maintenance of navigation records;

- Chief Engineer—oversees the engine department and mechanical systems, ensuring propulsion and auxiliary systems function properly;

- Second Engineer—assists the Chief Engineer in maintaining and operating mechanical systems;

- Medical Officer/Paramedic—provides medical care to rescued persons and ensures first aid readiness;

- Rescue Swimmer/Diver—trained to perform water-based rescue tasks under various conditions;

- Radio Operator—maintains continuous communication with the Rescue Coordination Centre and other vessels or aircraft;

- Deck Crew—performs deck operations, including launching and retrieving rescue boats and pollution recovery equipment;

- Rescue Boat Crew—operates smaller rescue craft deployed from the main vessel.

- Cook—responsible for food preparation and supply management;

1.3. Analysis of Principal SARORVs in Baltic Sea Region

- Size and capabilities: Finland and Sweden possess the largest SAR and oil recovery vessels, designed for a broader range of operations. They are equipped with larger oil recovery storage capacities and additional systems such as decompression chambers and dynamic positioning. Notably, Poland’s SAR vessel has a unique capability not found in other countries’ fleets—a remotely operated vehicle (ROV), which enables underwater operations and allows the vessel to conduct search and rescue missions in three dimensions: in the air, on the surface, and underwater;

- Speed and maneuverability: Estonia and Sweden operate the fastest SAR vessels (15 and 16 knots, respectively), which is a significant advantage for rapid response. Compared to the current Lithuanian SAR vessel, this represents nearly double the speed;

- Pollution recovery capacity: Finnish and Swedish vessels have the largest oil collection capacities (1200 m3 and 1050 m3 respectively). This enables them to perform extended recovery operations without external assistance. They are also equipped with a wider range of oil recovery technologies, such as disc and brush skimmers;

- Ice class: most Baltic Sea regions are ice-classed, which is essential for year-round operation in this region, especially during winter;

- Specialized equipment: Finland and Sweden’s vessels are the best equipped with specialized systems, including decompression chambers and dynamic positioning, enhancing their effectiveness during complex missions. Additionally, Finland’s SAR vessel has the capability to refuel and support helicopters at sea, significantly improving coordination between maritime and aerial units;

- Towing power: Swedish and Finnish vessels have the highest towing capacity (100 t), which is critically important for maritime rescue operations;

- Firefighting systems: nearly all SAR vessels in the Baltic Sea region countries are equipped with Class 1 firefighting systems, enabling them to assist in shipboard fire emergencies at sea—a crucial capability for maritime safety.

2. Methods

2.1. Mathematical Model of the Bridge Simulator

- Earth-fixed reference frame (X0Y0Z0)—X0 directed north, Y0 east, and Z0 downward;

- Body-fixed frame (XYZ)—the origin is at the vessel’s center of gravity (CG), with X pointing forward, Y to starboard, and Z downward;

- Local frame (X1Y1Z1)—parallel to the Earth-fixed system and centered at the vessel’s center of gravity.

2.2. Oil Spill Dispersion Simulation Program

2.3. Methodology for Calculating Search and Rescue Operation Areas

- Leeway (LW)—drift caused by wind acting on the object;

- Wind-driven current (WC)—surface current generated by the wind;

- Sea current (SC)—general oceanic or regional current;

- Tidal current (TC)—current resulting from tidal movements.

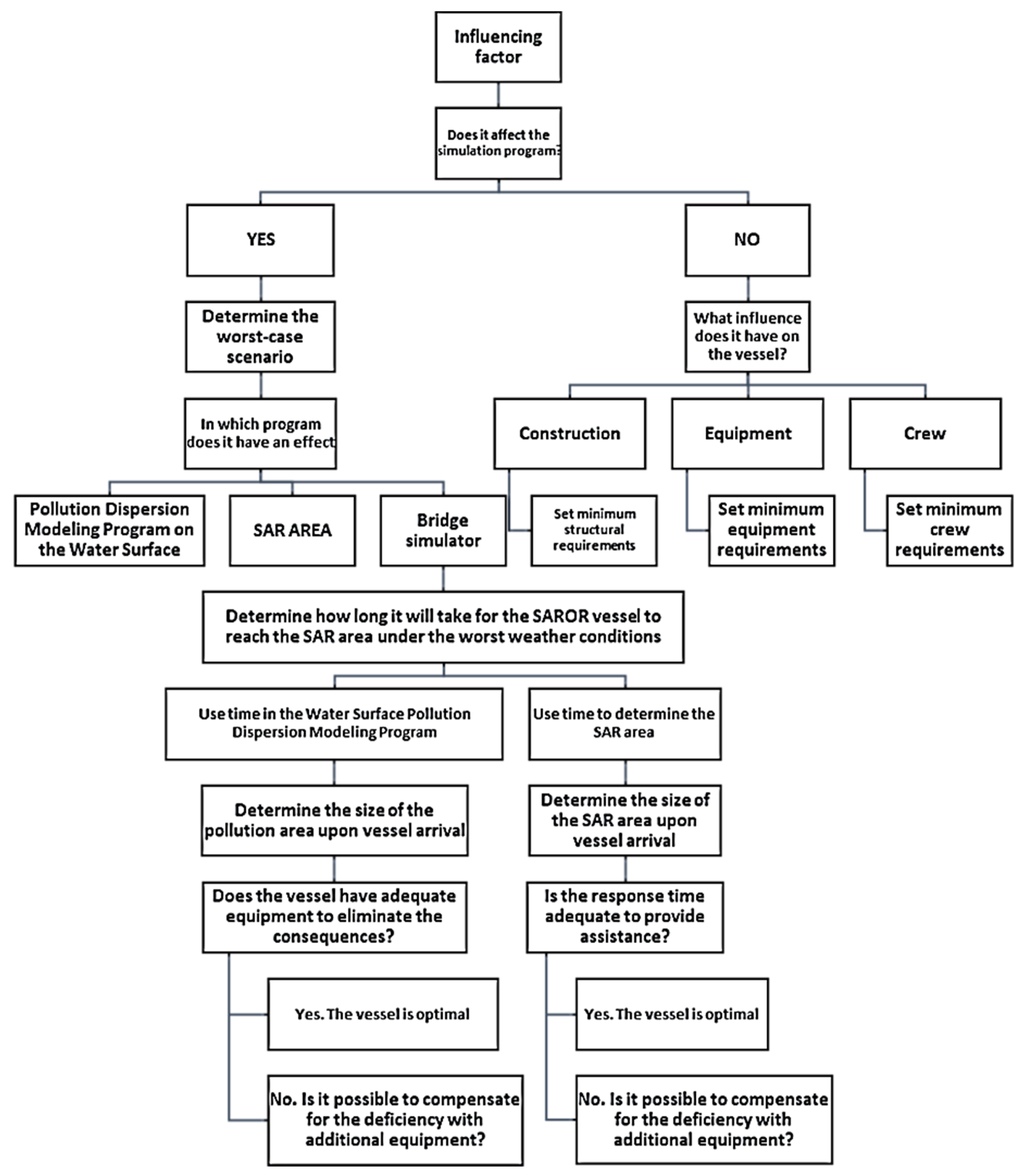

2.4. Methodology for the Evaluation of Factors Influencing SARORVs

3. Results and Discussion

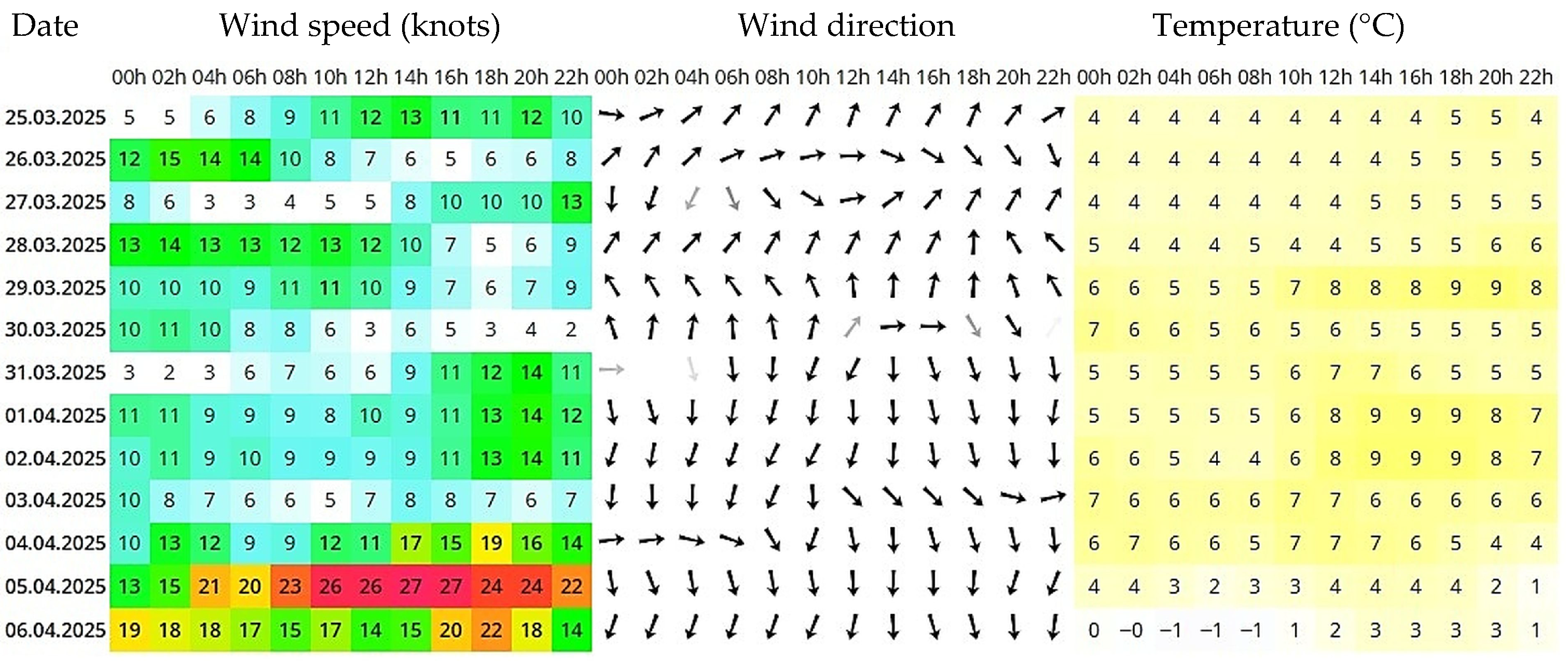

3.1. Hydrometeorological Conditions Evaluation

3.2. Assessment of Requirements for SAROR Operations

3.3. Assessment of the Impact of Ship Equipment on SAROR Operations

- Tier 1 (up to 7 t): Local response using ship or nearby resources;

- Tier 2 (7–700 t): Regional resources for medium spills;

- Tier 3 (over 700 t): International support for large spills;

- Mechanical recovery (booms, skimmers)—preferred for minimal environmental impact;

- Chemical dispersants—used only when environmentally suitable;

- In situ burning—as a last resort with proper authorization;

- Based on ITOPF and HELCOM recommendations, the SARORV should have full recovery capabilities and a 700 m3 storage tank. The vessel must be fitted with:

- ◦

- 1 crane (12-ton lifting capacity);

- ◦

- 600 m of containment booms;

- ◦

- 2 recovery arms;

- ◦

- 2 skimmers (brush type—100 m3/h, disc type—110 m3/h).

- A fire pump with a minimum capacity of 2400 m3/h;

- At least two fixed water monitors, each delivering 1000 m3/h;

- Fire monitors capable of projecting water 120 m horizontally and 45 m vertically;

- A foam system suitable for extinguishing oil and chemical fires.

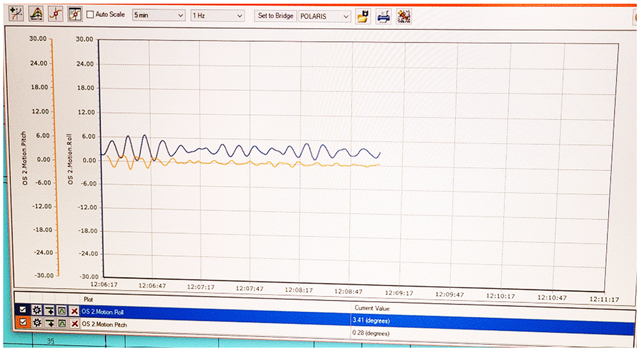

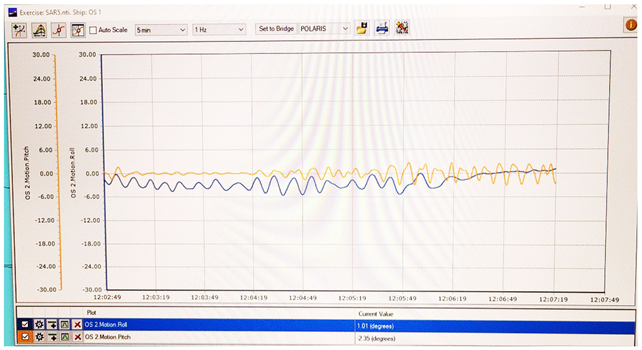

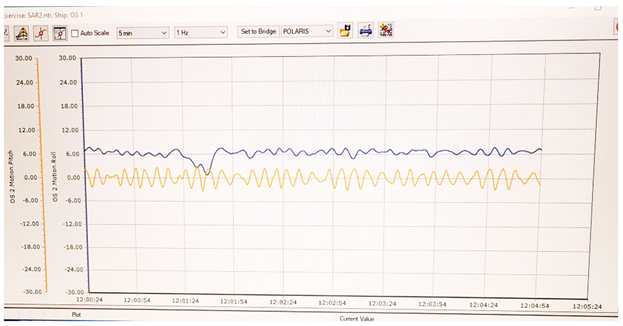

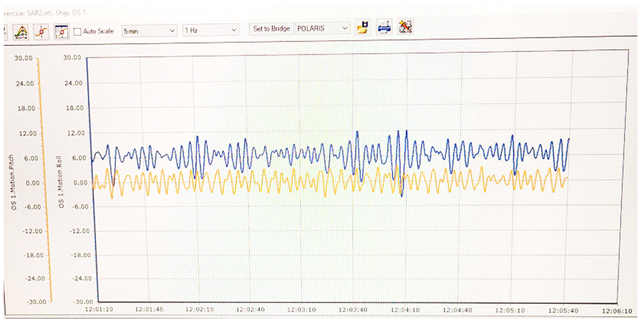

3.4. Evaluation of Data Generated in the Bridge Simulator

- while drifting (no propulsion),

- during dynamic positioning,

- and during transit at maximum speed to the assigned operation area.

3.5. Determination and Evaluation of the SAR Area Size

3.6. Assessment of Oil Spill Dispersion Modelling on the Water Surface

- PA—total contaminated area, m2;

- swath—sweep width of the oil spill recovery equipment, m;

- speed—maximum towing speed of the response equipment, m/s;

- ACR—Area Coverage Rate, indicating the rate at which the contaminated area is covered.

3.7. Summary of Technical Requirements for SARORV

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACR | Area Coverage Rate |

| AOP | Area Coverage Operational Period |

| BRISK | Sub-regional Risk of Spill of Oil and Hazardous Substances in the Baltic Sea |

| DP | Dynamic Positioning |

| EEZ | Exclusive Economic Zone |

| FF1 | Fire Fighting Class 1 (DNV standard) |

| GMDSS | Global Maritime Distress and Safety System |

| HELCOM | Helsinki Commission (Baltic Marine Environment Protection Commission) |

| IAMSAR | International Aeronautical and Maritime Search and Rescue Manual |

| IBS | Integrated Bridge System |

| IP | Integrated Power System |

| ITOPF | International Tanker Owners Pollution Federation |

| MRCC | Marine Rescue Coordination Center |

| OPV | Offshore Patrol Vessel |

| OSV | Offshore Supply Vessel |

| ROV | Remotely Operated Vehicle |

| SAR | Search and Rescue |

| SAROR | Search and Rescue and Oil Spill Recovery |

| SARORV | Search and Rescue and Oil Spill Recovery Vessel |

| SOLAS | International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea |

References

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Lithuania. IMO Conventions. Available online: https://www.urm.lt/en/treaties/conventions/imo-conventions/1324 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Republic of Lithuania. 1974 m. Tarptautinė Konvencija dėl Žmogaus Gyvybės Apsaugos Jūroje (SOLAS 74). TAR.C4D414572A07. Available online: https://www.e-tar.lt/portal/legalAct.html?documentId=TAR.C4D414572A07 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS). The Military Balance 2024; Routledge: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Pleskacz, K. The Impact of Hydro-Meteorological Conditions on the Safety of Fishing Vessels. Sci. J. Marit. Univ. Szczec. 2015, 41, 81–87. [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Márquez, V.; Hernández-Carrasco, I.; Simarro, G.; Rossi, V.; Orfila, A. Regionalizing the Impacts of Wind- and Wave-Induced Currents on Surface Ocean Dynamics: A Long-Term Variability Analysis in the Mediterranean Sea. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2021, 126, e2020JC017104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tipton, M.; McCormack, E.; Elliott, G.; Cisternelli, M.; Allen, A.; Turner, A.C. Survival Time and Search Time in Water: Past, Present and Future. J. Therm. Biol. 2022, 110, 103349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saydam, A.Z.; Taylan, M. Evaluation of Wind Loads on Ships by CFD Analysis. Ocean Eng. 2018, 158, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Daamen, W.; Vellinga, T.; Hoogendoorn, S.P. Impacts of wind and current on ship behavior in ports and waterways: A quantitative analysis based on AIS data. Ocean Eng. 2020, 213, 107774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellanco, M.J. Klaipėdos Projekto Galutinė Duomenų Ataskaita (2022-07-20 00:00–2023-07-19 23:50); Report No. EOL-KLA35. 2023. Available online: https://offshorewind.lt/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/EOL-KLA35-V02-OPS-Final-Data-Report-LT.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- British Hydrographic Office. ADMIRALTY Sailing Directions: Baltic Pilot Volume 2 (NP19), 18th ed.; UK Hydrographic Office: Taunton, UK, 2022; ISBN 978-0-7077-4755-2.

- Zhang, X.; Wang, C.; Jiang, L.; An, L.; Yang, R. Collision-Avoidance Navigation Systems for Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships: A State of the Art Survey. Ocean Eng. 2021, 235, 109380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yan, X.; Yang, Z.; Wall, A.; Wang, J. A Novel Model for the Quantitative Evaluation of the Effect of Environmental Factors on Ship Maneuverability. Ocean Eng. 2015, 110, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundh, M. A Life on the Ocean Wave: Exploring the Interaction Between the Crew and Their Adaptation to the Development of the Work Situation on Board Swedish Merchant Ships. Ph.D. Thesis, Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, Sweden, 2010. Available online: https://research.chalmers.se/en/publication/121794 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Tombul, S.; Tukenmez, E.; Oksuz, M.; Altiok, H. Predicting the Trajectories of Drifting Objects in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea. Turk. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2023, 24, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S. Understanding Design of Ice Class Ships. Marine Insight. 1 January 2021. Available online: https://www.marineinsight.com/naval-architecture/design-of-ice-class-ships/ (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Du, P.; Zeng, Z.; Zhang, J.; Liu, L.; Yang, J.; Qu, C.; Jiang, L.; Liu, S. Fog Season Risk Assessment for Maritime Transportation Systems Exploiting Himawari-8 Data: A Case Study in Bohai Sea, China. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lietuvos Kariuomenė. Dėl Žmonių Paieškos ir Gelbėjimo Darbų Paieškos ir Gelbėjimo Rajone Plano Patvirtinimo (2009, Nov 6, Nr. 119-5115). Available online: https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/TAIS.354144/asr (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- ITOPF. The Country & Territory Profiles; ITOPF: London, UK, 2023; Available online: https://www.itopf.org/knowledge-resources/countries-territories-regions/ (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Lietuvos Respublikos Seimas. 1979 Metų Tarptautinė Jūrų Paieškos ir Gelbėjimo Konvencija (2001, January 12, Nr. 4-94). Available online: https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/TAIS.117855 (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Lietuvos Respublikos Seimas. 1990 m. Tarptautinė Konvencija dėl Parengties, Veiksmų ir Bendradarbiavimo Įvykus Taršos Nafta Incidentams (Nr. 115-5135). 4 December 2002. Available online: https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/TAIS.196480 (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Lietuvos Respublikos Seimas. 1992 m. Helsinkio Konvencija dėl Baltijos Jūros Baseino Jūrinės Aplinkos Apsaugos (Nr. 21-499). 12 March 1997. Available online: https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/TAIS.36791 (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Priešgaisrinės Apsaugos ir Gelbėjimo Departamentas prie Vidaus Reikalų Ministerijos. Nacionalinė Rizikos Analizė. 2021. Available online: https://pagd.lrv.lt/lt/veiklos-sritys/civiline-sauga/nacionaline-rizikos-analize (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Aps, R.; Fetissov, M.; Goerlandt, F.; Kujala, P.; Piel, A. Systems-Theoretic Process Analysis of Maritime Traffic Safety Management in the Gulf of Finland (Baltic Sea). Procedia Eng. 2017, 179, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HELCOM. Map and Data Service. Available online: https://maps.helcom.fi/website/mapservice/ (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Hannaford, E.; Hassel, E.V. Risks and Benefits of Crew Reduction and/or Removal with Increased Automation on the Ship Operator: A Licensed Deck Officer’s Perspective. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HELCOM. Response Equipment. Available online: https://helcom.fi/action-areas/response-to-spills/response-equipment/ (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- EMSA—European Maritime Safety Agency. EMSA Pollution Response Services: Oil Spill Response Vessels, Equipment and Capacities; EMSA: Lisbon, Portugal, 2022. Available online: https://emsa.europa.eu (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Longhi, R.P.; Ferreira Filho, V.J.M. Strategic location model for oil spill response vessels (OSRVs) considering oil transportation and weather uncertainties. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 207, 116829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finnish Border Guard. Offshore Patrol Vessels and Oil Recovery Capabilities. Finnish Border Guard Official Publications. 2023. Available online: https://raja.fi/en/-/the-construction-of-the-finnish-border-guard-s-new-offshore-patrol-vessels-has-commenced (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Swedish Coast Guard. Multirole Emergency Response Vessels—Capabilities and Technical Specifications; Swedish Coast Guard: Stockholm, Sweden, 2022. Available online: https://www.kustbevakningen.se (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Polish Maritime Search and Rescue Service. SAR Fleet Capabilities and Technical Equipment. Maritime SAR Service of Poland. 2021. Available online: https://www.sar.gov.pl (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Transas Ltd. Description of Transas Mathematical Model (02.08); Transas Ltd.: St. Petersburg, Russia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Wang, Z.; Yu, J.; Hu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhang, H. Infrared Ocean Image Simulation Algorithm Based on Himawari-8 Satellite Data. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 6013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matar, R.; Abcha, N.; Abroug, I.; Lecoq, N.; Turki, E.-I. A Multi-Approach Analysis for Monitoring Wave Energy Driven by Coastal Extremes. Water 2024, 16, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, U.-J.; Jeong, W.-M.; Cho, H.-Y. Estimation and Analysis of JONSWAP Spectrum Parameter Using Observed Data around Korean Coast. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, R.A.; Neville, R.A.; Thomson, V. The Arctic Marine Oilspill Program (AMOP) Remote Sensing Study; Environmental Protection Service, Environment Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1983; 257p. [Google Scholar]

- Breivik, Ø.; Janssen, P.A.E.M.; Bidlot, J.-R. Approximate Stokes Drift Profiles in Deep Water. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 2014, 44, 2433–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fay, J.A. The Spread of Oil Slicks on a Calm Sea. In Oil on the Sea; Hoult, D.P., Ed.; Ocean Technology; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Keramea, P.; Spanoudaki, K.; Zodiatis, G.; Gikas, G.; Sylaios, G. Oil Spill Modeling: A Critical Review on Current Trends, Perspectives, and Challenges. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandvik, P.J.; Resby, J.L.M.; Daling, P.S.; Leirvik, F.; Fritt-Rasmussen, J. Meso-Scale Weathering of Oil as a Function of Ice Conditions. Oil Properties, Dispersibility and In-Situ Burnability of Weathered Oil as a Function of Time; Report No. 19; SINTEF Materials and Chemistry, Marine Environmental Technology: Trondheim, Norway, 2010; Available online: https://www.sintef.no/globalassets/project/jip_oil_in_ice/dokumenter/publications/jip-rep-no-19-common-meso-scale-final.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- International Maritime Organization (IMO). International Aeronautical and Maritime Search and Rescue Manual, Volume III, 12th ed.; ICAO: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- UK Hydrographic Office. NP100 The Mariner’s Handbook, 13th ed.; UK Hydrographic Office: Taunton, UK, 2023.

- Singh, S.; Maljutensko, I.; Uiboupin, R. Sea Ice in the Baltic Sea during 1993/94–2020/21 Ice Seasons from Satellite Observations and Model Reanalysis. Cryosphere 2025, 19, 4741–4758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabulevičienė, T.; Nesteckytė, L.; Kelpšaitė-Rimkienė, L. Assessing the Effect of Coastal Upwelling on the Air Temperature at the South-Eastern Coast of the Baltic Sea. Oceanologia 2024, 66, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Kerf, T.; Gladines, J.; Sels, S.; Vanlanduit, S. Oil Spill Detection Using Machine Learning and Infrared Images. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 4090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Admiral Danish Fleet HQ; National Operation; Maritime Environment. Project on Sub-Regional Risk of Spill of Oil and Hazardous Substances in the Baltic Sea (BRISK), Model Report: Part 1—Ship Traffic; Admiral Danish Fleet HQ: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2012; Available online: https://knowledgetool.mariner-project.eu/assets/uploads/resources/6f25f8_Model%20report%20(Part%201)_Ship%20traffic.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- O’Brien, M. At-Sea Recovery of Heavy Oils—A Reasonable Response Strategy. In Proceedings of the 3rd R&D Forum on High-Density Oil Spill Response, Brest, France, 11–13 March 2002; International Tanker Owners Pollution Federation Limited: London, UK, 2002. Available online: https://www.itopf.org/fileadmin/uploads/itopf/data/Documents/Papers/heavyoils.PDF (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Valstybės Duomenų Agentūra. Į Klaipėdos Uostą Atplaukiantys Arba iš jo Išplaukiantys Tarptautiniai Laivai; Valstybės Duomenų Agentūra: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2024. Available online: https://data.gov.lt/datasets/2864/ (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Hensen, H. Tug Use in Port: A Practical Guide, 2nd ed.; The Nautical Institute: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- HELCOM. Recommendation 28E/12: Strengthening of Sub-Regional Co-Operation in Response Field; HELCOM: Helsinki, Finland, 2007; Available online: https://www.helcom.fi/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Rec-28E-12.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Grządziel, A. Application of Remote Sensing Techniques to Identification of Underwater Airplane Wreck in Shallow Water Environment: Case Study of the Baltic Sea, Poland. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, R.; Lee, S.A.; O’Reilly, K.M.; Brady, O.J.; Bastos, L.; Carrasco-Escobar, G.; Catão, R.C.; Colón-González, F.J.; Barcellos, C.; Sá Carvalho, M.; et al. Combined Effects of Hydrometeorological Hazards and Urbanisation on Dengue Risk in Brazil: A Spatiotemporal Modelling Study. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e209–e219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windguru. Windguru: Archive. 2025. Available online: https://www.windguru.cz/archive.php (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE). ERSP Calculator User Manual; Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. Available online: https://www.bsee.gov/sites/bsee.gov/files/osrr-oil-spill-response-research/ersp-calculator-user-manual-20150222.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2025).

| Location | Number of Winters | First Ice | The Last Ice | Icing Days | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | Ice-Free | Earliest Day | Latest Day | Earliest Day | Latest Day | Min. | Avg. | Max. | |

| North | 29 | 8 | 20 November | 6 March | 20 February | 15 April | 0 | 30 | 87 |

| Klaipėda | 30 | 0 | 2 November | 16 February | 16 February | 19 April | 3 | 56 | 103 |

| South | 30 | 0 | 2 November | 19 February | 16 February | 19 April | 1 | 53 | 101 |

| Month/Location | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Klaipėda | 1.5 | 2.9 | 4.1 | 4.3 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.4 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 24 |

| Liepāja | 2.3 | 2.8 | 4.6 | 7.9 | 6.8 | 6.6 | 6.0 | 5.0 | 4.3 | 4.2 | 2.9 | 2.6 | 56 |

| Kaliningrad | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 2.8 | 2.5 | 3.5 | 6.0 | 6.8 | 4.8 | 3.1 | 1.8 | 38 |

| Country | Length/Beam/Draft (m) | Speed (kn) | Crane | Ice Class | Firefighting Equipment Class | Recovery Tank Capacity (m3) | Recovery Arms | Disc Skimmer (m3/h) | Brush Skimmer (m3/h) | Booms (m) | Towing Capacity | Other Equipment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latvia | 59.5/11.1/3.7 | 10.0 | 4 t | No | No | 170 | 2 units | 100 | 80 | 800 | No | |

| Estonia | 63.9/10.2/3.6 | 15.0 | 10 t | Yes | Class 1 | 100 | No | 160 | 100 | 600 | 40 t | |

| Lithuania | 59.4/10.5/4.7 | 9.5 | 3 t | No | Yes | 228 | No | 100 | 40 | 400 | 15 t | |

| Finland | 95.9/17.4/5.5 | 18.0 | 15 t | Yes | Class 1 | 1200 | 2 units | Yes | Yes | Yes | 100 t | Decompression chamber, helicopter landing capability, dynamic positioning |

| Sweden | 81.2/16.2/6.5 | 16.0 | 24 t | Yes | Class 1 | 1050 | 2 units | 100 | 100 | 500 | 100 t | Decompression chamber, dynamic positioning |

| Denmark | 56.0/12.3/4.6 | 12.0 | 28 t | Yes | - | 310 | 1 unit | 90 | Yes | 600 | 20 t | |

| Germany | 68.2/15.4/4.5 | 13.1 | 12.5 t | Yes | Class 1 | 430 | 2 units | Yes | Yes | 400 | 40 t | |

| Poland | 53.4/13.6/4.6 | 10.0 | 12 t | Yes | Class 1 | 512 | 2 units | 100 | 140 | 690 | 73 t | ROV |

| BN | Wind Speed, m/s | Wave Height, m | Terminology | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.0–0.2 | 0.0 | Calm | Calm. Smoke rises vertically. |

| 1 | 0.3–1.5 | 0.1 | Light air | Wind motion visible in smoke. |

| 2 | 1.6–3.3 | 0.2 | Light breeze | Wind felt on exposed skin. Leaves rustle. |

| 3 | 3.4–5.4 | 0.6 | Gentle breeze | Leaves and smaller twigs in constant motion. |

| 4 | 5.5–7.9 | 1.0 | Moderate breeze | Dust and loose paper is raised. Small branches begin to move. |

| 5 | 8.0–10.7 | 2.0 | Fresh breeze | Smaller trees sway. |

| 6 | 10.8–13.8 | 3.0 | Strong breeze | Large branches in motion. Whistling heard in overhead wires. |

| 7 | 13.9–17.1 | 4.0 | Near gale | Whole trees in motion. Some difficulty when walking into the wind. |

| 8 | 17.2–20.7 | 5.5 | Gale | Twigs broken from trees. Cars veer on road. |

| 9 | 20.8–24.4 | 7.0 | Severe gale | Light structure damage. |

| 10 | 24.5–28.4 | 9.0 | Storm | Trees uprooted. Considerable structural damage. |

| 11 | 28.5–32.6 | 11.5 | Violent storm | Widespread structural damage. |

| 12 | 32.7–40.8 | 14+ | Hurricane | Considerable and widespread damage to structures. |

| Factor | Relevant for Simulation Program? | Maximum and Average Value | Requirement for SARORV Concept |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wind | Yes, for all | 38 kn from 240°; 14 kn | Ability to operate at sea in Beaufort scale 8 wind conditions. |

| Wave Height | Yes, for all | 6 m from 240°; 3.5 m | Ability to operate at sea in Beaufort scale 8 wave conditions. |

| Current | Yes, for all | 2 kn from 240°; 0.25 kn | Ability to operate at sea with a current speed of up to 2 knots. |

| Water Temperature | Yes, for SAR area determination | Search object: life raft | Ability to cooperate with a helicopter, refuel it if required, and provide first aid to rescued persons. |

| Ice Thickness and Icing | No | - | Comply with ice class 1C requirements. |

| Fog | No | - | Equipped with a thermal camera for human detection and a 7–14 μm wavelength thermal camera for oil spill detection. |

| Task | Performed by | Required Crew per Shift | Number of Shifts | Can Perform Other Functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Command | Human | 1 | 1 | No |

| Ship Maneuvering | Human | 1 | 2 | No |

| Navigation | Human | 1 | 2 | No |

| Ship Control | Automated | 0 | - | - |

| Communications | Human | 1 | 2 | No |

| Rescue Operation Coordination | Human | 1 | 2 | No |

| Vital Systems Monitoring | Automated | 0 | - | - |

| Propulsion Systems Monitoring | Automated | 0 | - | - |

| Repair and Maintenance | Human | 1 | 2 | No |

| Cooking | Human | 1 | 1 | No |

| Firefighting Equipment Operator | Human | 2 | 1 | Yes, when not firefighting |

| Boat Launching | Human | 3 | 1 | Yes, when not launching boats |

| Boat Operation | Human | 2 | 1 | Yes, when not operating boats |

| Rescue Swimmer | Human | 1 | 1 | Yes, when not swimming |

| Pollution Collection | Human | 3 | 1 | Yes, when not collecting pollution |

| Medical Treatment | Human | 1–2 | 1 | No, requires medical qualification |

| Factor | Is the Factor Required for Modeling Program? | Factor’s Maximum and Average Value | Defined Requirement for Vessel Concept |

|---|---|---|---|

| International conventions | Yes, PDMP * and bridge simulator | Pollution area position | - |

| Yes, SAR area and bridge simulator | SAR area position | - | |

| National regulations | No | - | Preparation time up to 2 h; for crew efficiency, the vessel must include catering and recreation facilities. |

| Communication equipment | No | - | GMDSS equipment, additionally 1×HF, 1×MF, 2×VHF radios, and AirVHF. |

| Area of responsibility | No | - | The vessel must be equipped with a dynamic positioning system. |

| Crew composition | No | - | The vessel must ensure sanitary and living conditions for 20 crew members. Automation level must comply with IP and IBS standards under Lloyd’s Register requirements. |

| Cooperation with other units | No | - | Communication equipment must allow coordination with other units and aircraft depending on water temperature conditions. |

| Factor | Is the Factor Required for Modeling Programs? | Maximum and Average Factor Value | Defined Requirement for Vessel Concept |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oil recovery equipment | Yes, PDMP * | Spilled pollutant amount—700 t | 12 t crane, 2 recovery arms, 600 m of booms, brush skimmer 100 m3/h, disc skimmer 110 m3/h. |

| Incident analysis | No | - | Towing capacity BP 113 t, FF1-class firefighting equipment, towed side-scan sonar (SSS), remotely operated underwater vehicle (ROV). |

| Experience of other countries | No | - | - |

| Image | Technical Data |

|---|---|

| OSV (Offshore Supply Vessel) Length: 93.5 m Beam: 22 m Displacement: 8800 t Speed: 14.4 knots Engine power: 2 × 2200 kW Propulsion: Azimuth electric thrusters |

| OPV (Offshore Patrol Vessel) Length: 65.9 m Beam: 10.7 m Displacement: 835 t Speed: 21.5 knots Engine power: 1 × 5500 kW Propulsion: Fixed-pitch propeller |

| Vessel Type | Speed Over Ground | Speed Through Water | Transit Time | Preparation Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transit to SAR area, under worst hydrometeorological conditions | ||||

| OSV | 7.9 kn | 8.6 kn | 11 h 45 min | 2 h |

| OPV | 13.9 kn | 15.4 kn | 7 h 20 min | 2 h |

| Transit to SAR area, under average hydrometeorological conditions | ||||

| OSV | 8.5 kn | 8.1 kn | 8 h | 2 h |

| OPV | 12.7 kn | 15.8 kn | 5 h | 2 h |

| Transit to pollution response area, under average hydrometeorological conditions | ||||

| OSV | 9.9 kn | 10.1 kn | 6 h 45 min | 2 h |

| OPV | 17.3 kn | 16.8 kn | 4 h | 2 h |

| TEST Scenario | OSV | OPV | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without propulsion |  |  | ||

| Dynamic positioning |  |  | ||

| Full speed |  |  | ||

| side rolling |  | longitudinal pitching | |

| Ship Type | Area Size (nm) | Ship Speed (kn) | Number of Tracks | Distance in Area (nm) | Arrival Time (h) | Operation Time (h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAR area under worst hydrometeorological conditions | ||||||

| OSV | 30 × 40 | 7.9 | 27 | 1080 | 13.75 | 137 |

| OPV | 21 × 26 | 13.9 | 19 | 494 | 9.33 | 36 |

| SAR area under average hydrometeorological conditions | ||||||

| OSV | 9 × 10 | 10.4 | 8 | 80 | 12.00 | 8 |

| OPV | 5 × 7 | 17.5 | 5 | 35 | 8.00 | 2 |

| Vessel Type | Area Length, nm (m) | Area Width, nm (m) | Area Size, m2 | Oil Recovery Arm Coverage, m |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pollution area under worst hydrometeorological conditions | ||||

| OSV | 3.7 (6900) | 0.8 (1500) | 10,400,000 | 40 |

| OPV | 2.5 (4600) | 0.7 (1300) | 5,980,000 | 23 |

| Pollution area under average hydrometeorological conditions | ||||

| OSV | 2.5 (4600) | 0.2 (400) | 1,800,000 | 7 |

| OPV | 1.5 (2800) | 0.2 (400) | 1,100,000 | 4 |

| Parameter | Required Value | Purpose/Justification |

|---|---|---|

| Length | ≈90 m | Required for equipment capacity, accommodation, and stability. |

| Beam | ≥20 m | Ensures sufficient stability in heavy seas. |

| Displacement | ≥8000 t | Provides buoyancy and storage for response systems. |

| Speed | ≥15 knots (≥10.6 knots in Beaufort 8) | Ensures timely arrival to SAR and spill areas. |

| Endurance | ≥6 days and ≥1200 nautical miles | Enables long-duration operations without resupply. |

| Readiness time | ≤2 h | Meets emergency response activation requirements. |

| Ice class | ≥1C | Enables operations in seasonal ice near Klaipėda. |

| Propulsion system | Azimuth thrusters + bow thruster (DP capable) | Allows precise station-keeping during rescue and spill response. |

| Main engine power | ~2 × 2500–3000 kW | Supports required speed under adverse conditions. |

| Bollard pull | ≥113 t | Allows towing large vessels during emergencies. |

| Oil recovery capacity | ≥700 t storage | Required for large spill response operations. |

| Skimmers | Brush ≥ 100 m3/h and Disc ≥ 110 m3/h | Supports mechanical oil recovery. |

| Oil recovery arms | 2 units, ≥40 m swath | Ensures efficient spill sweep width. |

| Oil booms | ≥600 m | Required for containment operations. |

| Deck crane | ≥12 t lifting capacity | Supports lifting, rescue, and equipment handling. |

| Side-scan sonar | Towed high-resolution | Enables underwater search and incident assessment. |

| ROV | Yes, remote-operated vehicle | Supports deep and structural underwater inspections. |

| Rescue boats | 2 units | Enables person-in-water recovery. |

| IR/Thermal sensors | 7–14 μm band | Allow detection in darkness and fog. |

| Firefighting system | FF Class 1 | Enables marine industrial firefighting. |

| GMDSS area | A3 | Ensures global maritime distress communication. |

| Communication radios | HF, MF, ≥2 × VHF, Air-VHF | Allows SAR and inter-agency coordination. |

| Navigation suite | GPS, AIS, ECDIS, Autopilot, Dual Radar | Ensures safe navigation and search planning. |

| Crew | 18 + 2 medical staff | Supports continuous operations and emergency care. |

| Accommodation | Living quarters, galley, recreation, medical facilities | Ensure operational sustainability. |

| Automation level | IP + IBS | Integrated bridge & power management reduces crew workload. |

| Helicopter support | Helideck + refueling | Enables joint SAR operations and casualty evacuation. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Žaglinskis, J. Optimal SAR and Oil Spill Recovery Vessel Concept for Baltic Sea Operations. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2026, 14, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010012

Žaglinskis J. Optimal SAR and Oil Spill Recovery Vessel Concept for Baltic Sea Operations. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2026; 14(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010012

Chicago/Turabian StyleŽaglinskis, Justas. 2026. "Optimal SAR and Oil Spill Recovery Vessel Concept for Baltic Sea Operations" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 14, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010012

APA StyleŽaglinskis, J. (2026). Optimal SAR and Oil Spill Recovery Vessel Concept for Baltic Sea Operations. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 14(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010012