Spherical Gravity Inversion Reveals Crustal Structure and Microplate Tectonics in the Caribbean Sea

Abstract

1. Introduction

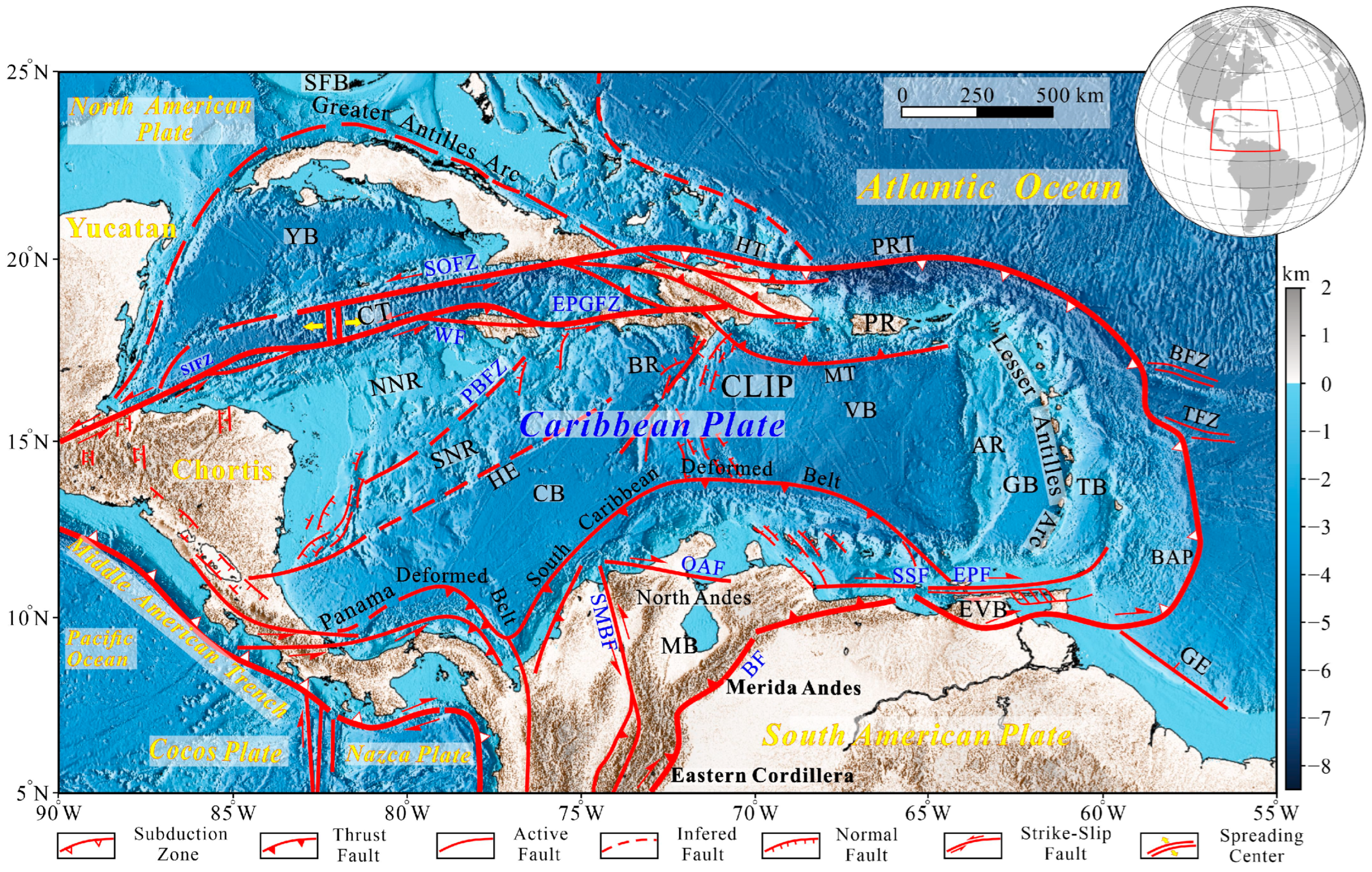

2. Regional Geological Setting

3. Data and Methods

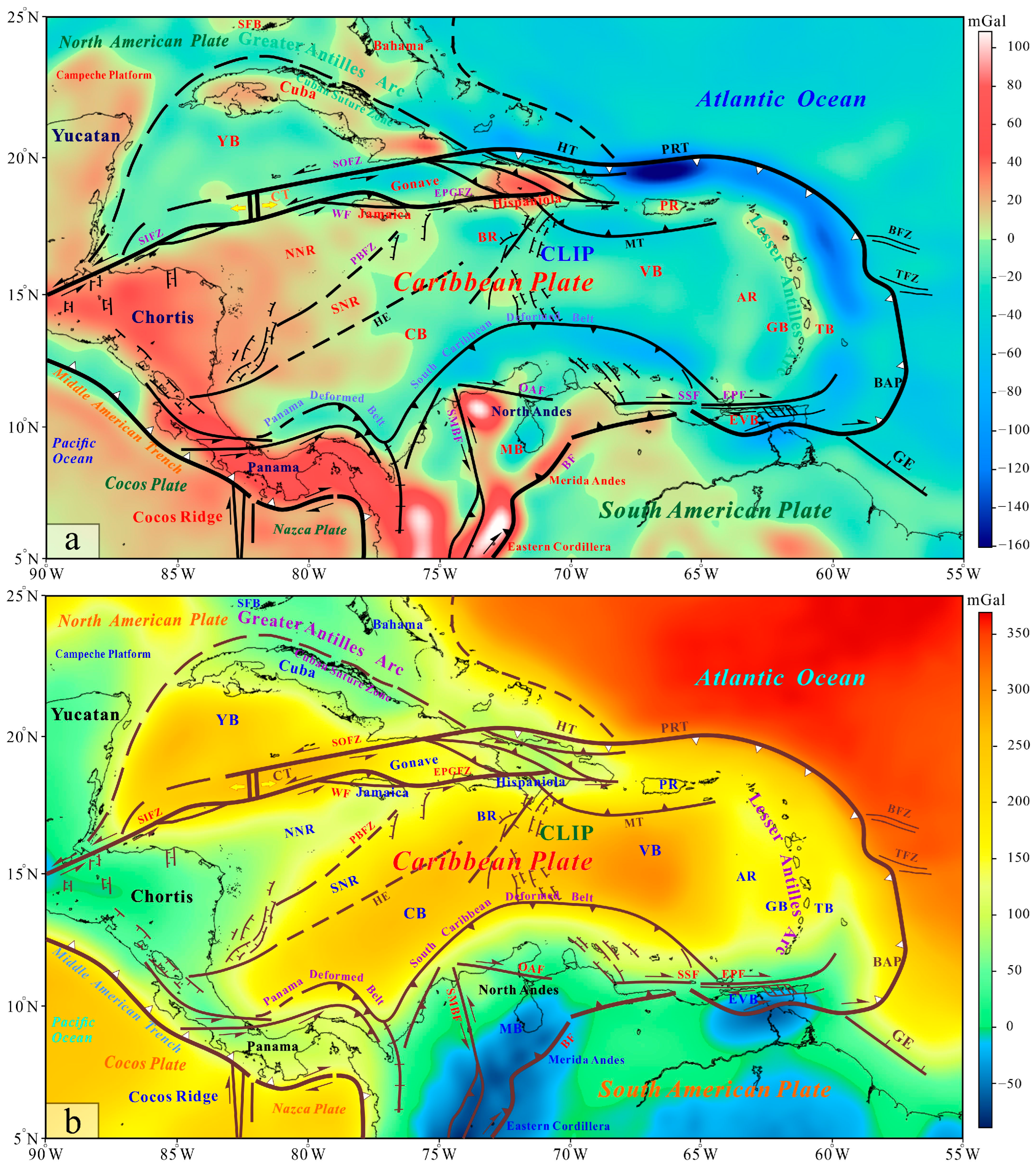

3.1. Data

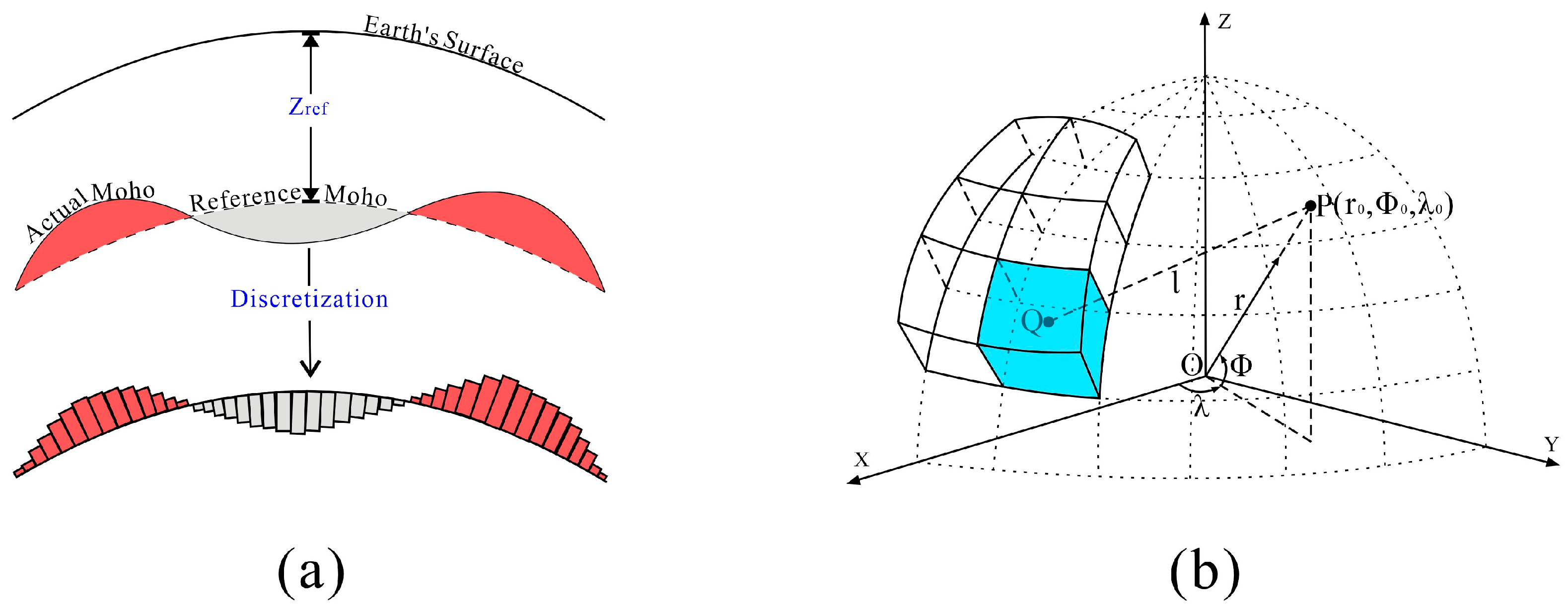

3.2. Rapid Nonlinear Inversion Method Based on Spherical Coordinate System

3.2.1. Data Preprocessing

3.2.2. Forward Modeling Construction

3.2.3. Objective Function Construction

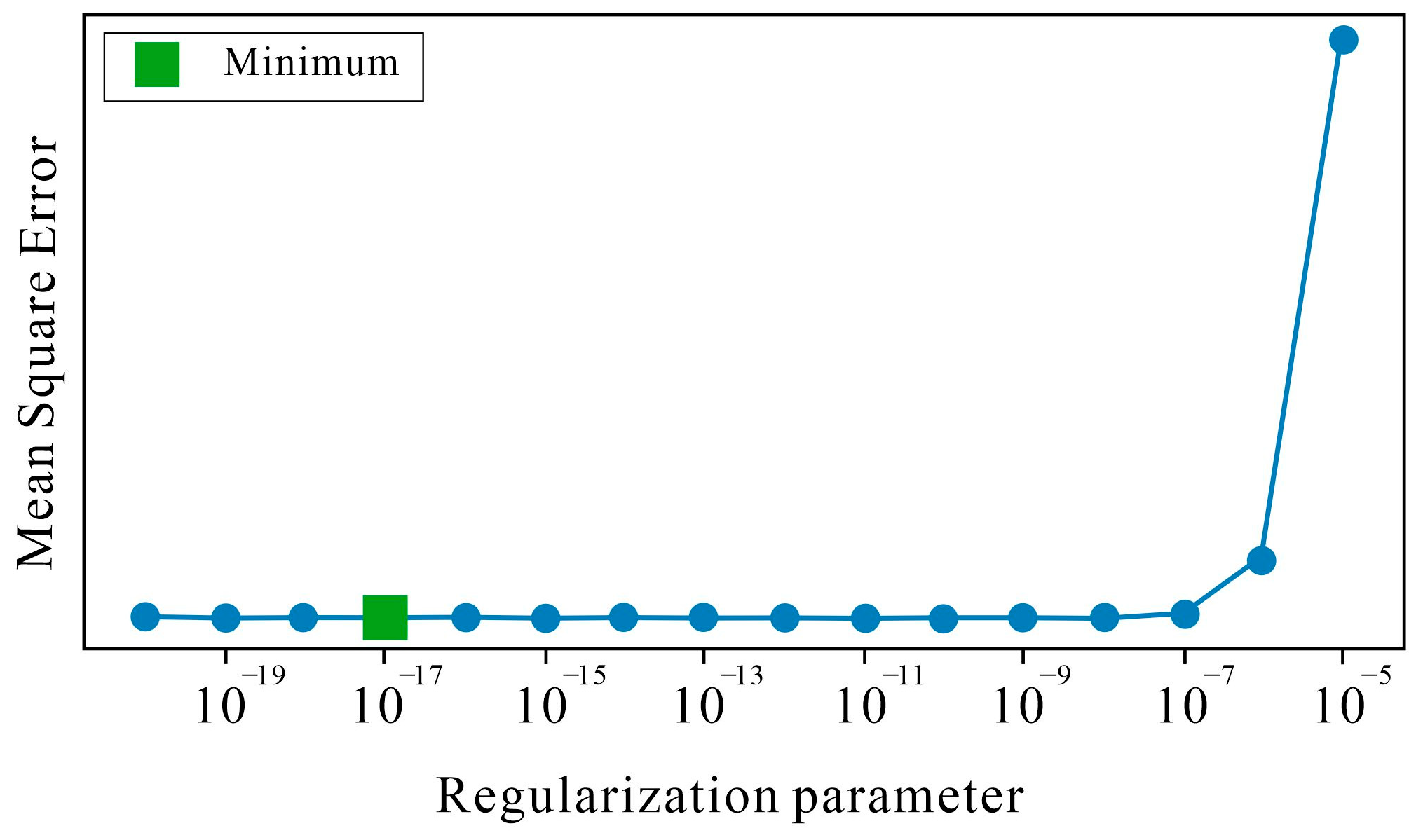

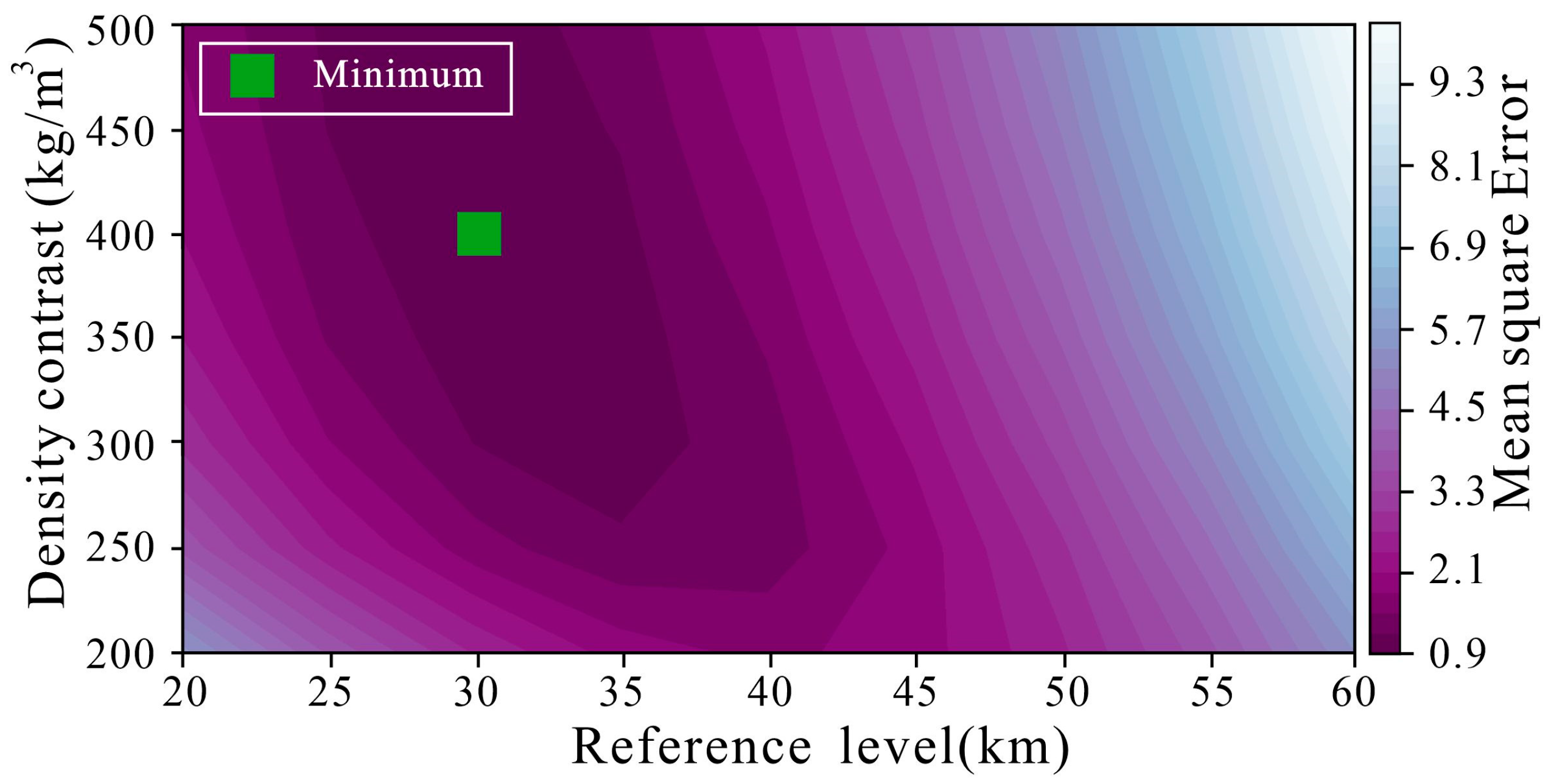

3.2.4. Parameter Selection

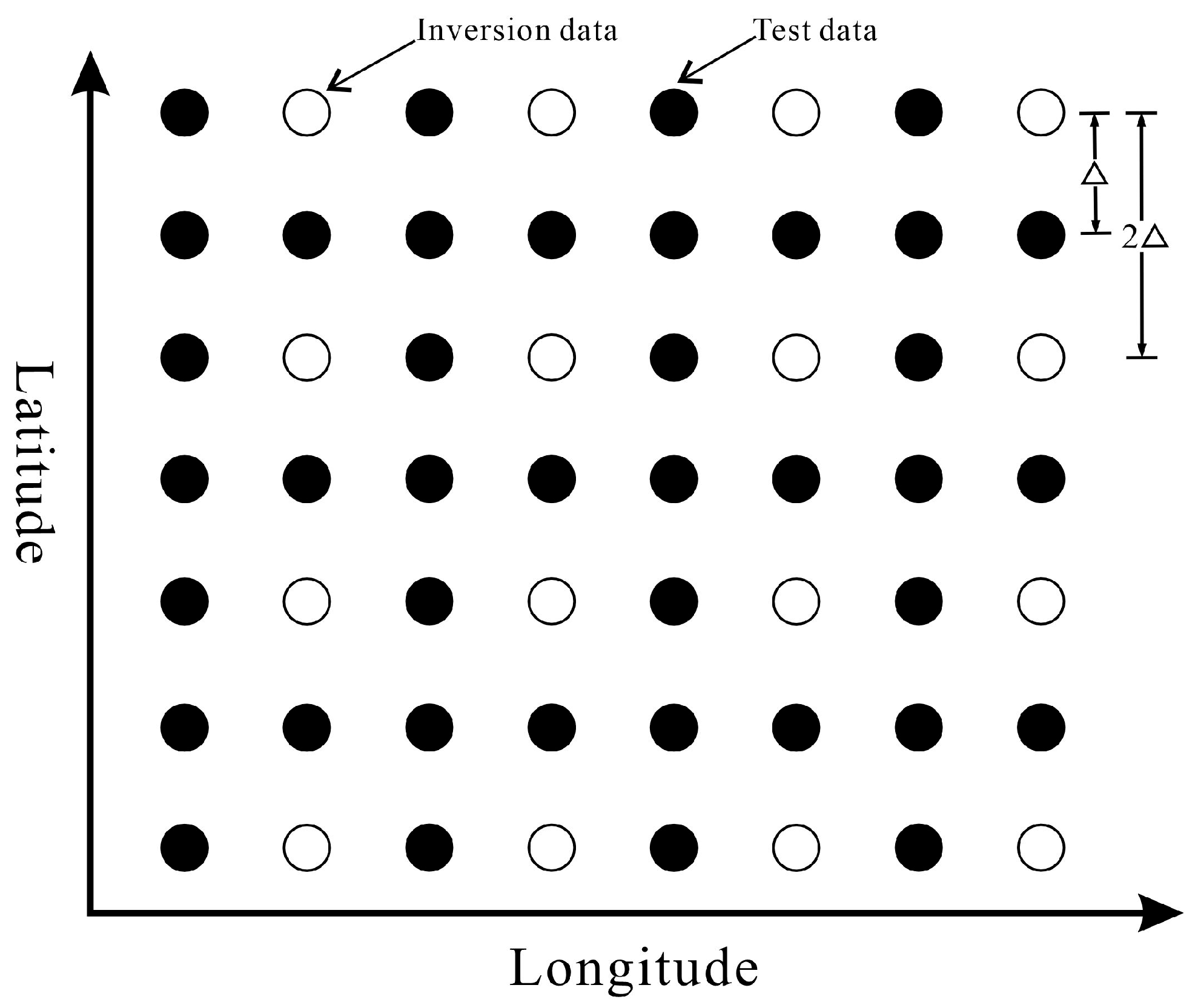

3.2.5. Model Evaluation and Constraint Fusion

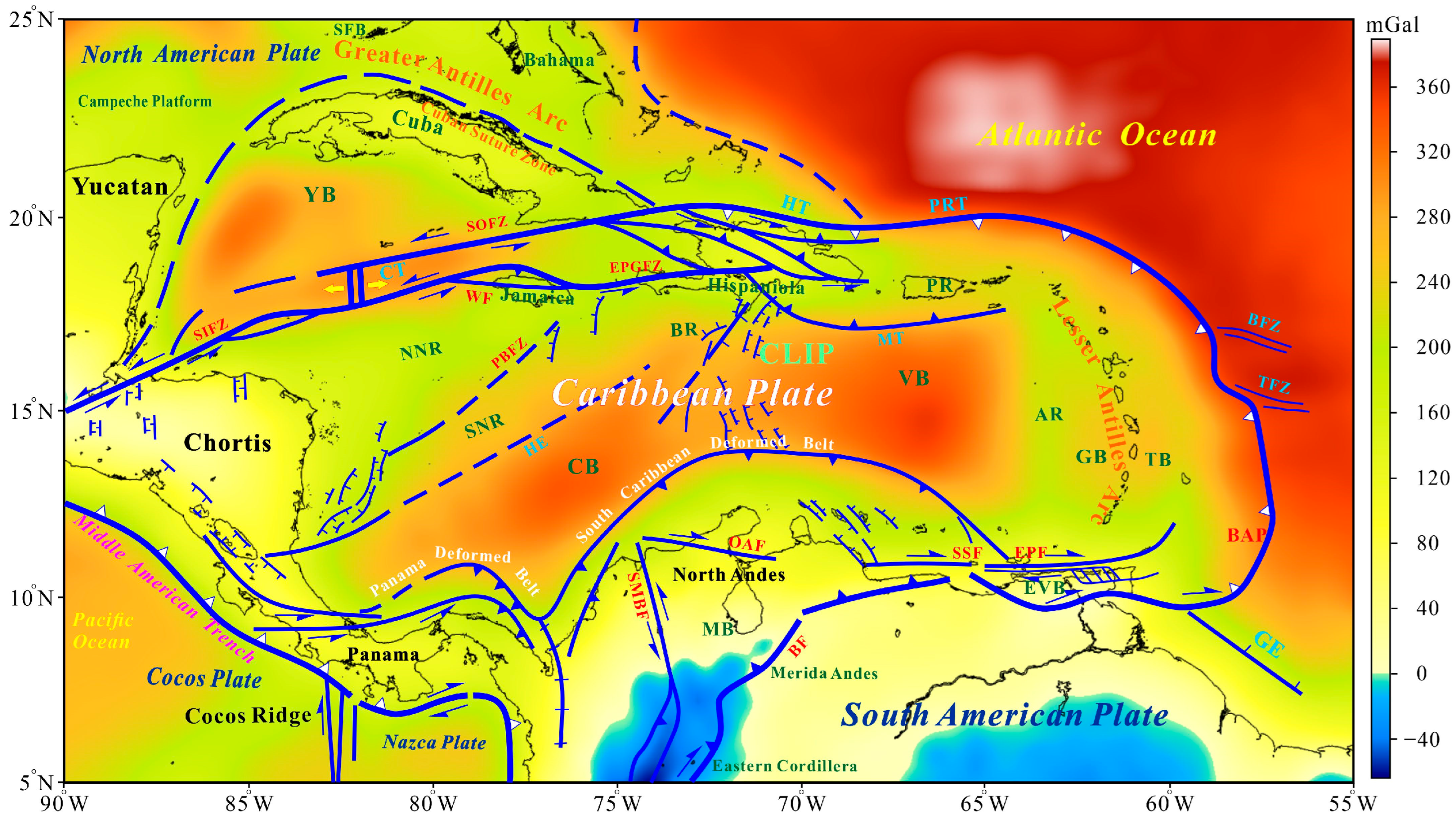

4. Results and Analysis

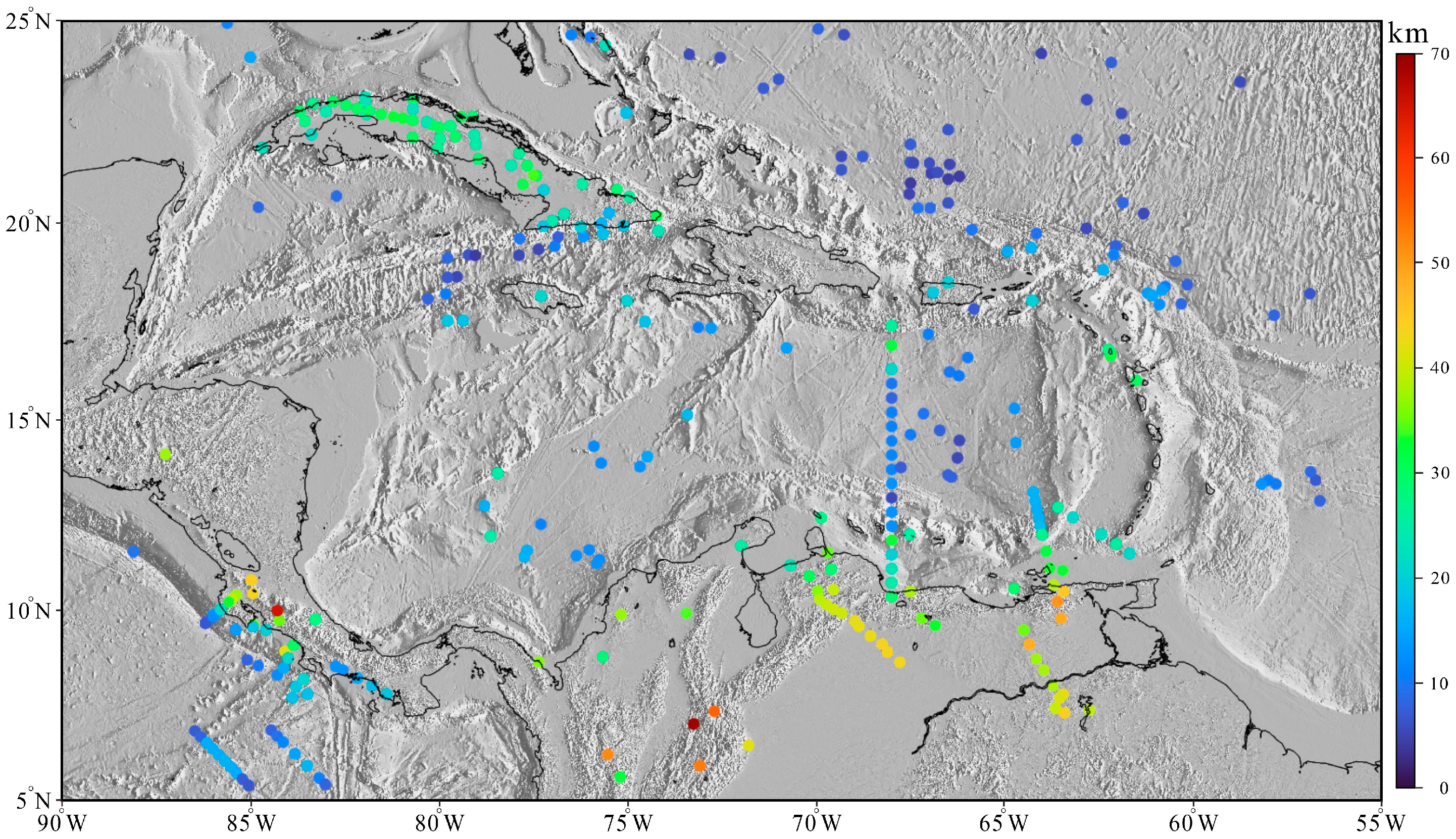

4.1. Moho Depth

4.2. Comparison with Previous Inversion Results

4.3. Microplate Tectonic Characteristics

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AR | Aves Ridge | MB | Maracaibo Basin |

| BAP | Barbados Accretionary Prism | NECB | Northeastern Colombian Basin |

| BF | Bocono Fault | NNR | North Nicaraguan Rise |

| BFZ | Barracuda Fracture Zone | OAF | Oca-Ancon Fault |

| BR | Beata Ridge | PBFZ | Pedro Bank Fault Zone |

| CB | Colombian Basin | PRT | Puerto Rico Trench |

| CLIP | Caribbean Large Igneous Province | SFB | South Florida Basin |

| CR | Curaçao Ridge | SIFZ | Swan Islands Fault Zone |

| CS | Caribbean Sea | SMBF | Santa Maria–Bucaramanga Fault |

| CT | Cayman Trough | SNR | South Nicaraguan Rise |

| EPF | El Pilar Fault | SOFZ | Septentrional–Oriente Fault Zone |

| EPGFZ | Enriquillo–Plantain Garden Fault Zone | SSF | San Sebastian Fault |

| EVB | Eastern Venezuela Basin | SWCB | Southwestern Colombian Basin |

| GB | Grenada Basin | TB | Tobago Basin |

| GE | Guiana Escarpment | TFZ | Tiburón Fracture Zone |

| HE | Hess Escarpment | VB | Venezuelan Basin |

| HT | Hispaniola Trench | WF | Walton Fault |

| MAT | Middle America Trench | YB | Yucatan Basin |

References

- Bezada, M.J.; Levander, A.; Schmandt, B. Subduction in the southern Caribbean: Images from finite-frequency P wave tomography. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2010, 115, B12333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschman, L.M.; van Hinsbergen, D.J.; Torsvik, T.H.; Spakman, W.; Pindell, J.L. Kinematic reconstruction of the Caribbean region since the Early Jurassic. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2014, 138, 102–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Reyes, A.; Dyment, J. Structure, age, and origin of the Caribbean Plate unraveled. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2021, 571, 117100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera-Lopez, C.V.; Mooney, W.D.; Kaban, M.K. Regional geophysics of the Caribbean and northern South America: Implications for tectonics. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2022, 23, e2021GC010112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, S.; Cao, X.; Suo, Y.; Jiang, S.; Zhu, J. Refinement of microplate boundaries assisted by integrated gravity analysis: Application to the Caribbean Sea. Mar. Geol. 2024, 470, 107251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, W.; Meschede, M.; Sick, M. Origin of the Central American ophiolites: Evidence from paleomagnetic results. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 1992, 104, 1301–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, K.H. Arguments for and against the Pacific origin of the Caribbean Plate: Discussion, finding for an inter-American origin. Geol. Acta 2006, 4, 279–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, K.; Fox, P.J.; Şengör, A.M.C. Buoyant ocean floor and the evolution of the Caribbean. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 1978, 83, 3949–3954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pindell, J.; Dewey, J.F. Permo-Triassic reconstruction of western Pangea and the evolution of the Gulf of Mexico/Caribbean region. Tectonics 1982, 1, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Benthem, S.; Govers, R.; Spakman, W.; Wortel, R. Tectonic evolution and mantle structure of the Caribbean. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2013, 118, 3019–3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benford, B.; DeMets, C.; Calais, E. GPS estimates of microplate motions, northern Caribbean: Evidence for a Hispaniola microplate and implications for earthquake hazard. Geophys. J. Int. 2012, 191, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomassi, A.; de Franco, R.; Trippetta, F. High-resolution synthetic seismic modelling: Elucidating facies heterogeneity in carbonate ramp systems. Pet. Geosci. 2025, 31, petgeo2024-047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhu, R.; Shen, H.; Liu, S.; Yang, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, W.; Sun, B. Deep processes and surface effects of the Meso-Cenozoic Caribbean subduction system. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2025, 55, 2226–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, O.L.; Alvarez, L.; Guidarelli, M.; Panza, G.F. Crust and upper mantle structure in the Caribbean region by group velocity tomography and regionalization. Pure Appl. Geophys. 2007, 164, 1985–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lü, Y.; Li, J.; Zhao, L.F.; Zhang, J.; Chen, L.; Zhao, L. New constraints on the complex subduction and tearing model of the Cocos plate using anisotropic Pn tomography. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2023, 24, e2023GC011124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-García, Á.M.; Meeßen, C.; Scheck-Wenderoth, M.; Monsalve, G.; Bott, J.; Bernhardt, A.; Bernal, G. 3-D modeling of vertical gravity gradients and the delimitation of tectonic boundaries: The Caribbean oceanic domain as a case study. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2019, 20, 5371–5393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Suo, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, B.; Dai, L.; Wang, G.; Zhang, G. Microplate tectonics: New insights from micro-blocks in the global oceans, continental margins and deep mantle. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2018, 185, 1029–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Casco, A.; Iturralde-Vinent, M.A.; Pindell, J. Latest Cretaceous collision/accretion between the Caribbean Plate and Caribeana: Origin of metamorphic terranes in the Greater Antilles. Int. Geol. Rev. 2008, 50, 781–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riel, N.; Duarte, J.C.; Almeida, J.; Kaus, B.J.; Rosas, F.; Rojas-Agramonte, Y.; Popov, A. Subduction initiation triggered the Caribbean large igneous province. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meschede, M.; Frisch, W. A plate-tectonic model for the Mesozoic and Early Cenozoic history of the Caribbean plate. Tectonophysics 1998, 296, 269–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pindell, J.; Kennan, L.; Stanek, K.P.; Maresch, W.V.; Draper, G. Foundations of Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean evolution: Eight controversies resolved. Geol. Acta 2006, 4, 303–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, P. Gulf of Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean. In Encyclopedia of Geology, 2nd ed.; Alderton, D., Elias, S.A., Eds.; Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 47–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Stern, R.J.; Yang, J. Seismic evidence for subduction-induced mantle flows underneath Middle America. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malfait, B.T.; Dinkelman, M.G. Circum-Caribbean tectonic and igneous activity and the evolution of the Caribbean plate. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 1972, 83, 251–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pindell, J.; Maresch, W.V.; Martens, U.; Stanek, K. The Greater Antillean Arc: Early Cretaceous origin and proposed relationship to Central American subduction mélanges: Implications for models of Caribbean evolution. Int. Geol. Rev. 2012, 54, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, C.W.; Miller, M.S.; Porritt, R.W. Tomographic imaging of slab segmentation and deformation in the Greater Antilles. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2018, 19, 2292–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braszus, B.; Goes, S.; Allen, R.; Rietbrock, A.; Collier, J.; Harmon, N.; Henstock, T.; Hicks, S.; Rychert, C.A.; Maunder, B.; et al. Subduction history of the Caribbean from upper-mantle seismic imaging and plate reconstruction. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uieda, L.; Barbosa, V.C. Fast nonlinear gravity inversion in spherical coordinates with application to the South American Moho. Geophys. J. Int. 2017, 208, 162–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bott, M.H.P. The use of rapid digital computing methods for directgravity interpretation ofsedimentary basins. Geophys. J. Int. 1960, 3, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikhonov, A.N.; Arsenin, V.Y. Solutions of Ill-Posed Problems, 1st ed.; V. H. Winston & Sons: Washington, DC, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.H. Estimating classification error rate: Repeated cross-validation, repeated hold-out and bootstrap. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2009, 53, 3735–3745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romito, S.; Mann, P. Tectonic terranes underlying the present-day Caribbean plate: Their tectonic origin, sedimentary thickness, subsidence histories and regional controls on hydrocarbon resources. In The Basins, Orogens and Evolution of the Southern Gulf of Mexico and Northern Caribbean, 1st ed.; Davison, I., Hull, J.N.F., Pindell, J., Eds.; Geological Society of London: London, UK, 2021; Volume 504, pp. 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casallas, I.F.; Hu, J.-C. Effective Elastic Thickness in Northern South America. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andjić, G.; Baumgartner, P.O.; Baumgartner-Mora, C. Collision of the Caribbean Large Igneous Province with the Americas: Earliest evidence from the forearc of Costa Rica. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2019, 131, 1555–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, J.; Mann, P.; Emmet, P.A. Late Cretaceous–Cenozoic tectonic transition from collision to transtension, Honduran Borderlands and Nicaraguan Rise, NW Caribbean Plate boundary. In Transform Margins: Development, Controls and Petroleum Systems, 1st ed.; Nemčok, M., Rybár, S., Sinha, S.T., Hermeston, S.A., Ledvényiová, L., Eds.; Geological Society of London: London, UK, 2016; Volume 431, pp. 57–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.F.; Kysar Mattietti, G.; Perfit, M.; Kamenov, G. Geochemistry and petrology of three granitoid rock cores from the Nicaraguan Rise, Caribbean Sea: Implications for its composition, structure and tectonic evolution. Geol. Acta 2011, 9, 0467–0469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, B.; Mann, P.; Mike, S. Crustal provinces of the Nicaraguan Rise as a control on source rock distribution and maturity. AAPG Search Discov. 2013, 90163, 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly, T.W. The Caribbean Cretaceous basalt association: A vast igneous province that includes the Nicoya Complex of Costa Rica. Pro-Fil 1994, 7, 17–45. [Google Scholar]

- Case, J.E.; MacDonald, W.D.; Fox, P.J. Caribbean crustal provinces; seismic and gravity evidence. In The Caribbean Region, 1st ed.; Dengo, G., Case, J.E., Eds.; Geological Society of America: Boulder, CO, USA, 1991; Volume H, pp. 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauffret, A.; Leroy, S. Seismic stratigraphy and structure of the Caribbean igneous province. Tectonophysics 1997, 283, 61–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, N.; Hall, A.; Casey, J.F. Seafloor spreading magnetic anomalies in the Venezuelan Basin. Mem. Geol. Soc. Am. 1984, 162, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, B.R. Reconstructing the early depositional history of a failed ocean basin from a large 3-d dataset acquired in the Colombia Basin, Western Caribbean Sea, Offshore Colombia. In Proceedings of the American Association of Petroleum Geologists Annual Convention & Exhibition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 20–23 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kroehler, M.E.; Mann, P.; Escalona, A.; Christeson, G.L. Late Cretaceous-Miocene diachronous onset of back thrusting along the South Caribbean deformed belt and its importance for understanding processes of arc collision and crustal growth. Tectonics 2011, 30, TC6003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.W.; Collier, J.S.; Stewart, A.G.; Henstock, T.; Goes, S.; Rietbrock, A. The role of arc migration in the development of the Lesser Antilles: A new tectonic model for the Cenozoic evolution of the eastern Caribbean. Geology 2019, 47, 891–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, A.C.; White, R.V.; Thompson, P.M.; Tarney, J.; Saunders, A.D. No oceanic plateau—No Caribbean plate? The seminal role of an oceanic plateau in Caribbean plate evolution. In The Circum-Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean: Hydrocarbon Habitats, Basin Formation and Plate Tectonics, 1st ed.; Bartolini, C., Buffler, R.T., Blickwede, J.F., Eds.; American Association of Petroleum Geologists: Tulsa, OK, USA, 2003; Volume 79, pp. 126–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés, M.; Angelier, J. Current states of stress in the northern Andes as indicated by focal mechanisms of earthquakes. Tectonophysics 2005, 403, 29–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.W.; Colli, L.; Bird, D.E.; Wu, J.; Zhu, H. Caribbean plate tilted and actively dragged eastwards by low-viscosity asthenospheric flow. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Benthem, S.; Govers, R. The Caribbean plate: Pulled, pushed, or dragged? J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2010, 115, B10409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladd, J.W.; Watkins, J.S. Tectonic development of trench-arc complexes on the northern and southern margins of the Venezuela Basin1. In Geological and Geophysical Investigations of Continental Margins, 1st ed.; Watkins, J.S., Montadert, L., Dickerson, P.W., Eds.; American Association of Petroleum Geologists: Tulsa, OK, USA, 1979; Volume 29, pp. 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosencrantz, E.; Ross, M.I.; Sclater, J.G. Age and spreading history of the Cayman Trough as determined from depth, heat flow, and magnetic anomalies. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 1988, 93, 2141–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosencrantz, E.; Mann, P. SeaMARC II mapping of transform faults in the Cayman Trough. Geology 1991, 19, 690–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, D.E.; Hall, S.A.; Casey, J.F.; Millegan, P.S. Interpretation of magnetic anomalies over the Grenada Basin. Tectonics 1993, 12, 1267–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, T.; Mann, P.; Escalona, A.; Christeson, G.L. Evolution of the Grenada and Tobago basins and implications for arc migration. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2011, 28, 235–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearey, P. Gravity and seismic reflection investigations into the crustal structure of the Aves Ridge, eastern Caribbean. Geophys. J. Int. 1974, 38, 435–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, W.P.; Vedder, J.G.; Graf, R.J. Structural profile of the northwestern Caribbean. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1972, 17, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terence Edgar, N.; Ewing, J.I.; Hennion, J. Seismic Refraction and Reflection in Caribbean Sea. AAPG Bull. 1971, 55, 833–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diebold, J.B.; Stoffa, P.L.; Buhl, P.; Truchan, M. Venezuela Basin crustal structure. J. Geophys. Res. 1981, 86, 7901–7923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoernle, K.; Hauff, F.; van den Bogaard, P. 70 my history (139–69 Ma) for the Caribbean large igneous province. Geology 2004, 32, 697–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Officer, C.B., Jr.; Ewing, J.I.; Edwards, R.S.; Johnson, H.R. Geophysical investigations in the eastern Caribbean; Venezuelan basin, Antilles island arc, and Puerto Rico trench. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 1957, 68, 359–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talwani, M.; Sutton, G.H.; Worzel, J.L. A crustal section across the Puerto Rico Trench. J. Geophys. Res. 1959, 64, 1545–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhao, F.; Zhan, C.; Pei, J.; Chen, Y.; Dai, M.; Hu, B.; Hou, L.; Ning, Z.; Xu, R. Spherical Gravity Inversion Reveals Crustal Structure and Microplate Tectonics in the Caribbean Sea. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2026, 14, 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010109

Zhao F, Zhan C, Pei J, Chen Y, Dai M, Hu B, Hou L, Ning Z, Xu R. Spherical Gravity Inversion Reveals Crustal Structure and Microplate Tectonics in the Caribbean Sea. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2026; 14(1):109. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010109

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Feiyu, Chunrong Zhan, Junling Pei, Yumin Chen, Mengxue Dai, Bin Hu, Lifu Hou, Zixi Ning, and Rongrong Xu. 2026. "Spherical Gravity Inversion Reveals Crustal Structure and Microplate Tectonics in the Caribbean Sea" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 14, no. 1: 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010109

APA StyleZhao, F., Zhan, C., Pei, J., Chen, Y., Dai, M., Hu, B., Hou, L., Ning, Z., & Xu, R. (2026). Spherical Gravity Inversion Reveals Crustal Structure and Microplate Tectonics in the Caribbean Sea. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 14(1), 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010109