Detection of Ship-Related Pollution Transported into Klaipeda City

Abstract

1. Introduction

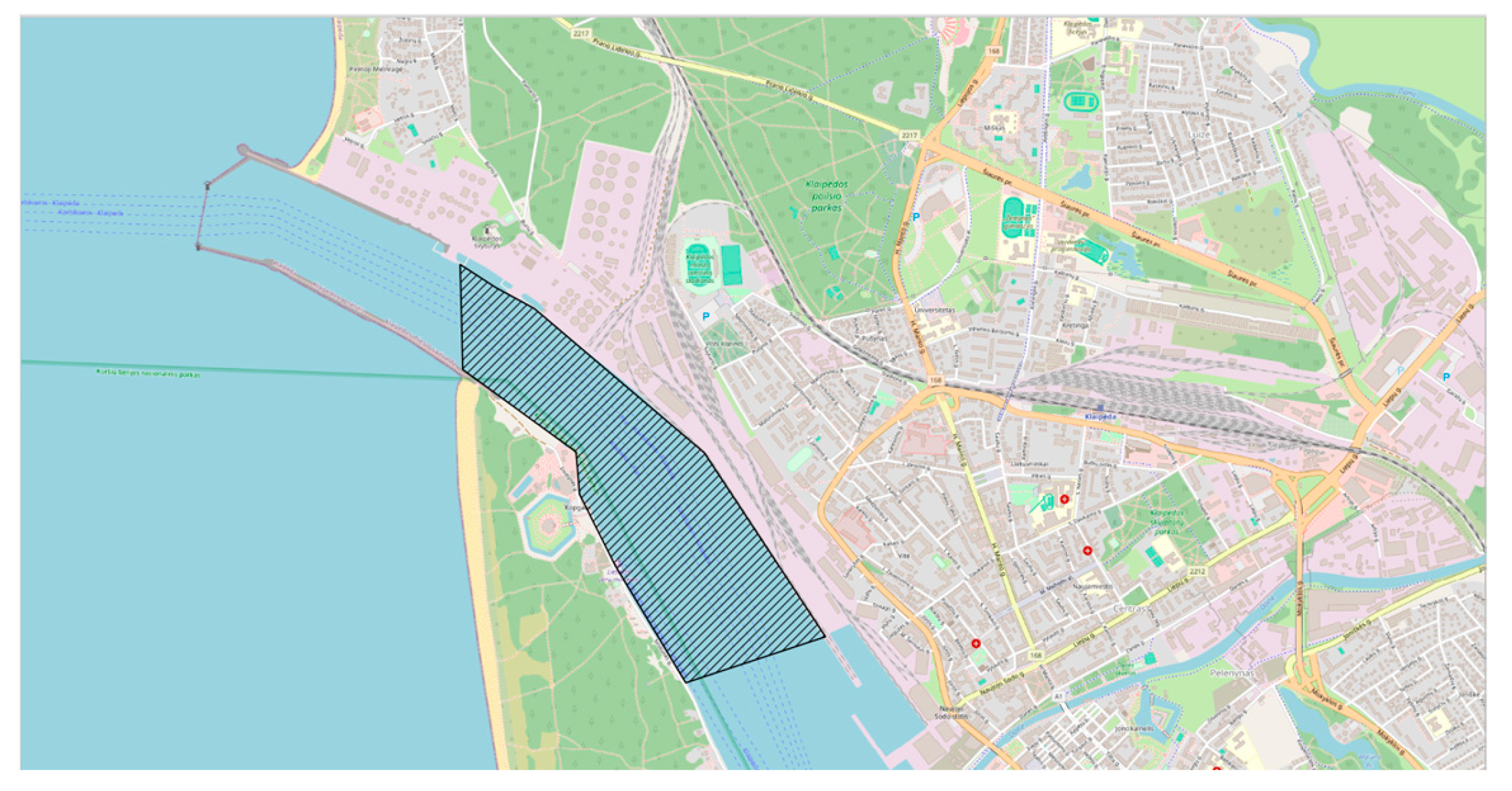

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

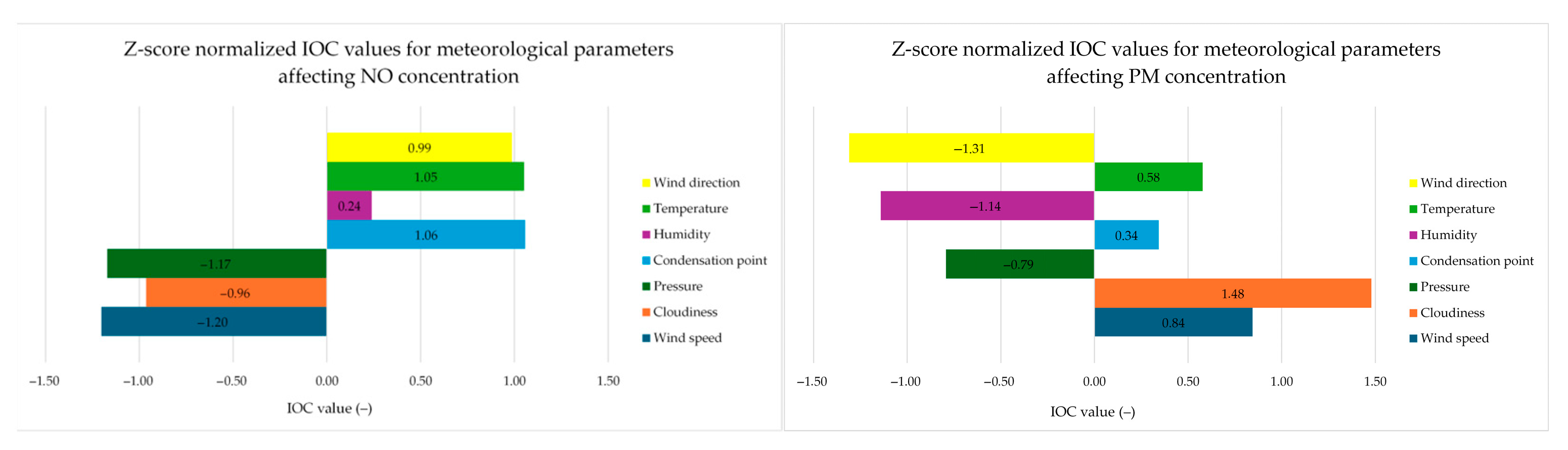

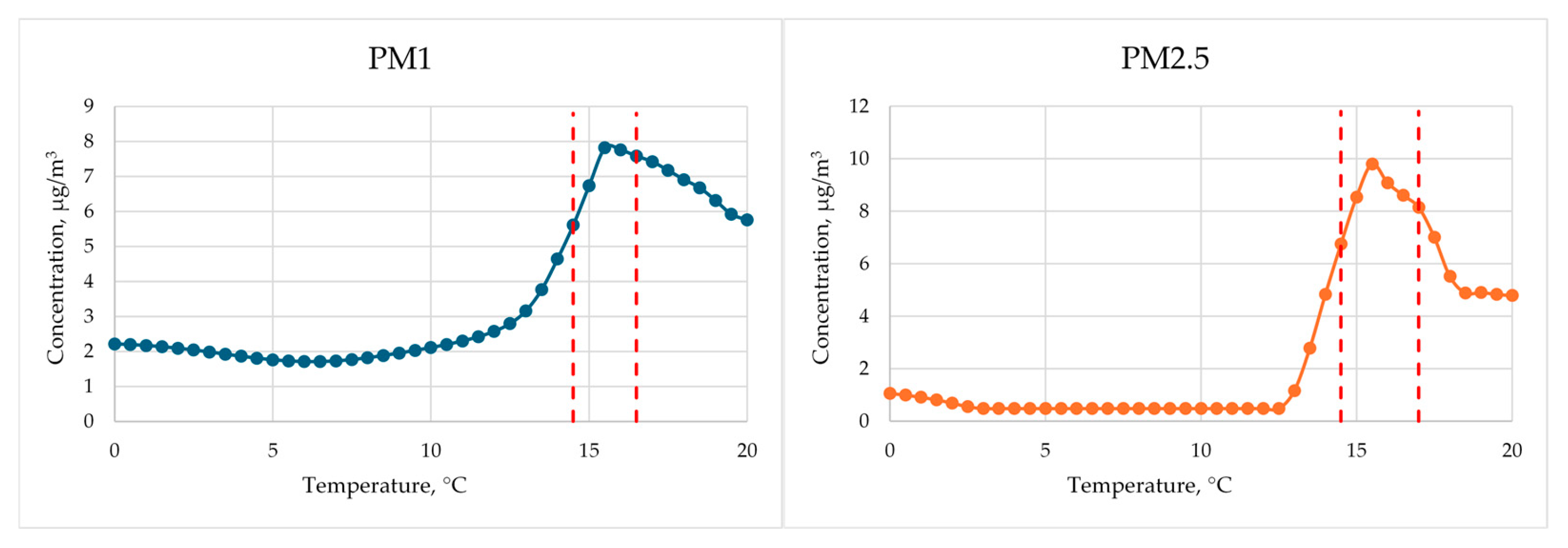

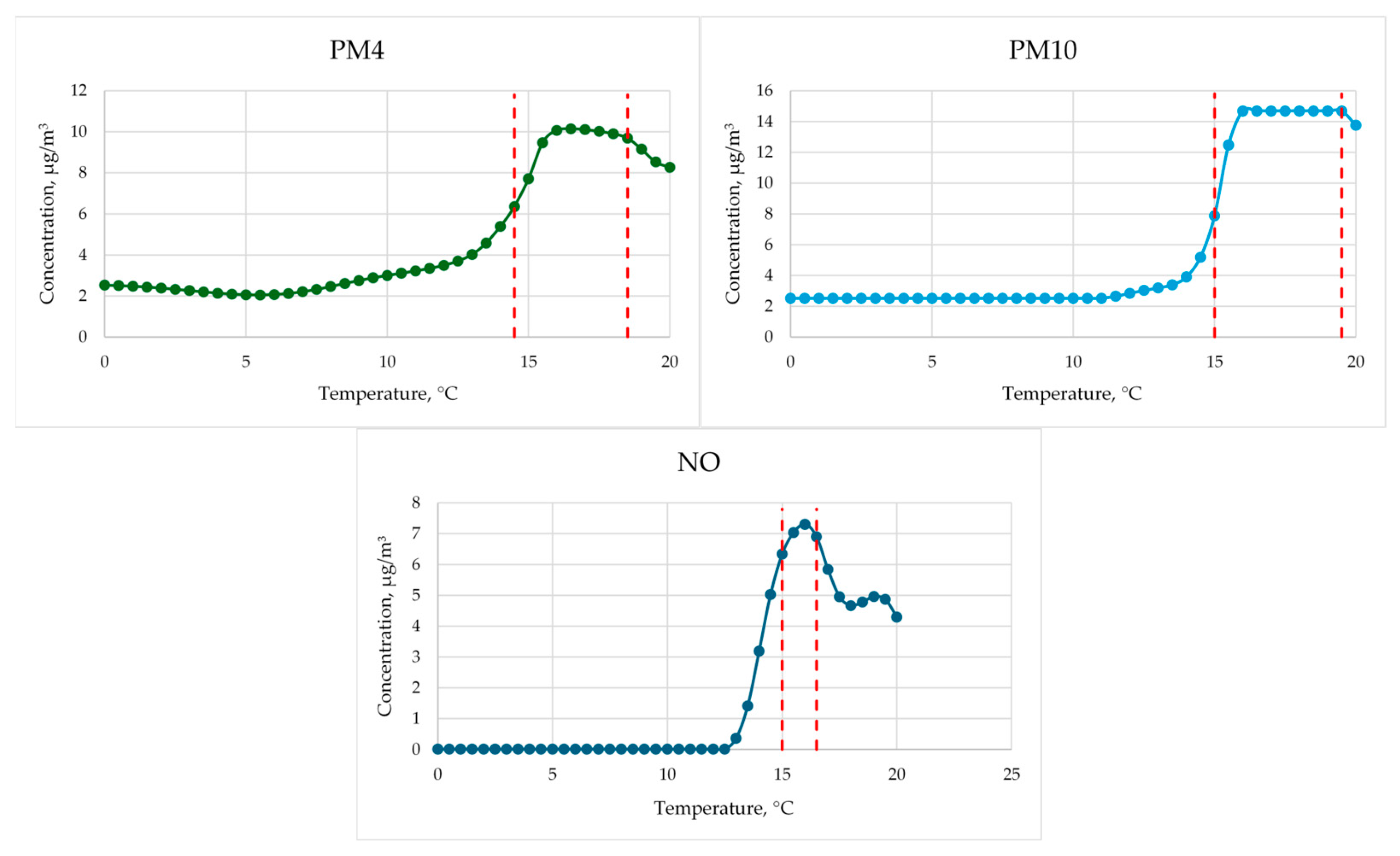

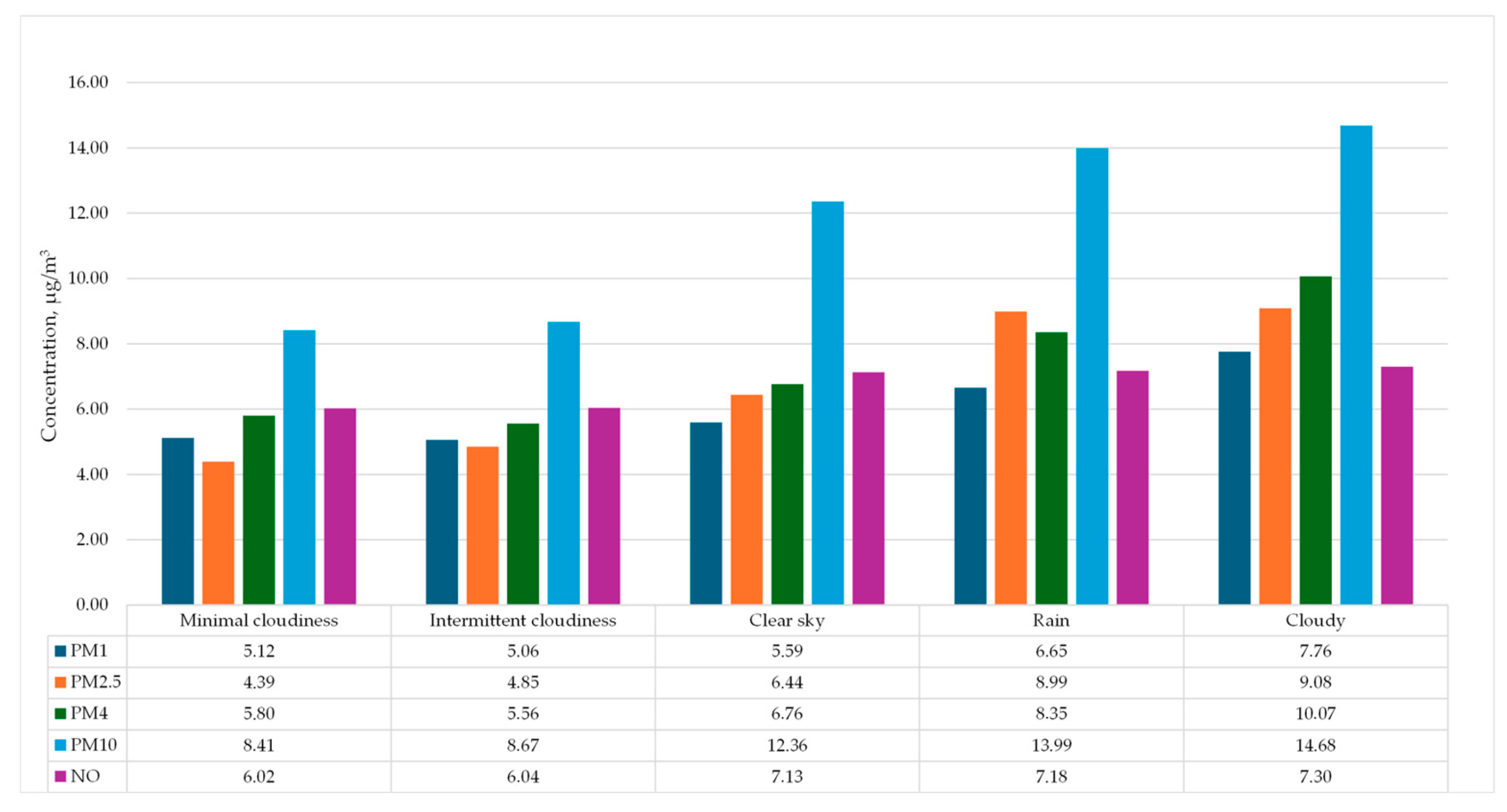

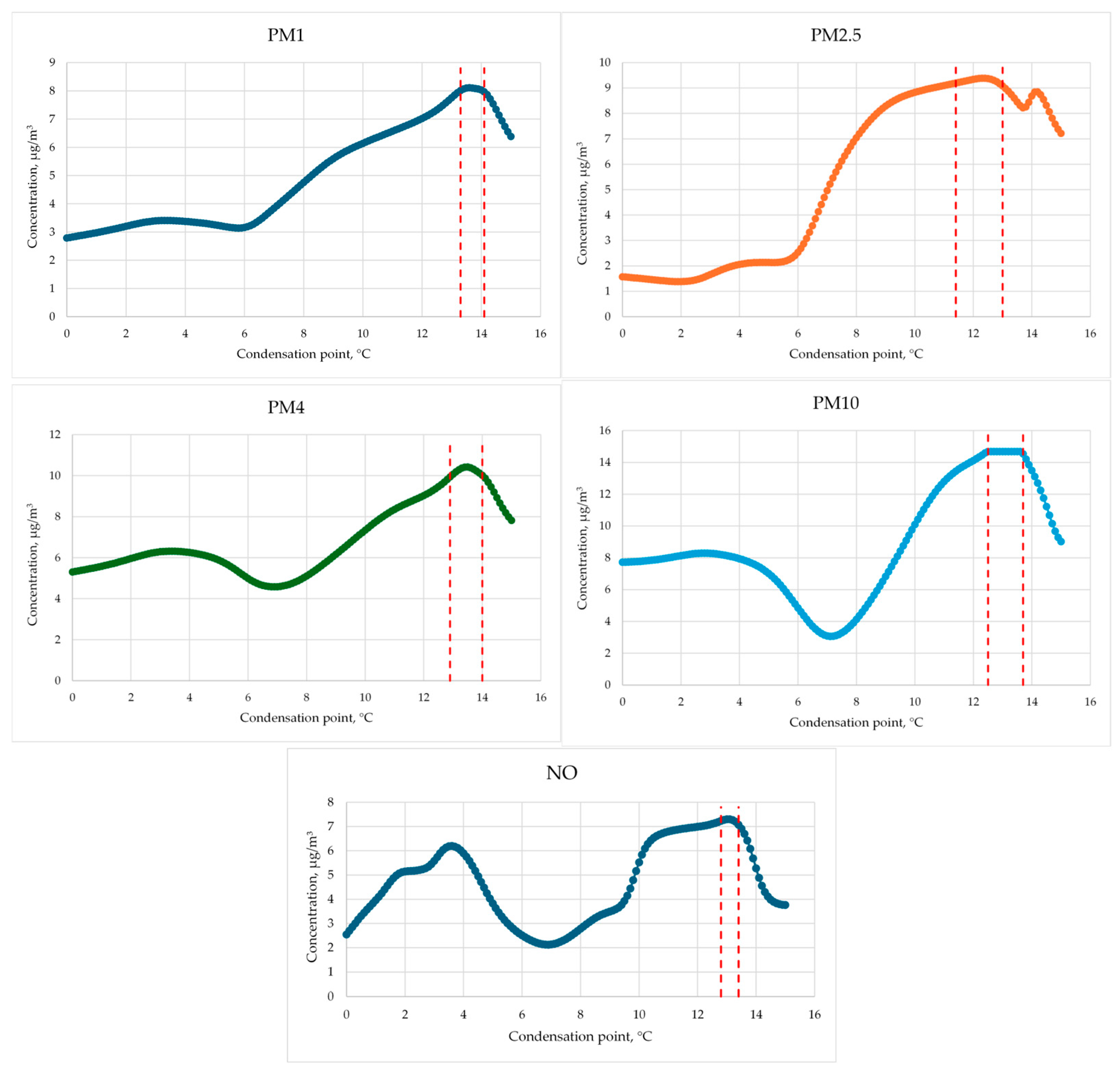

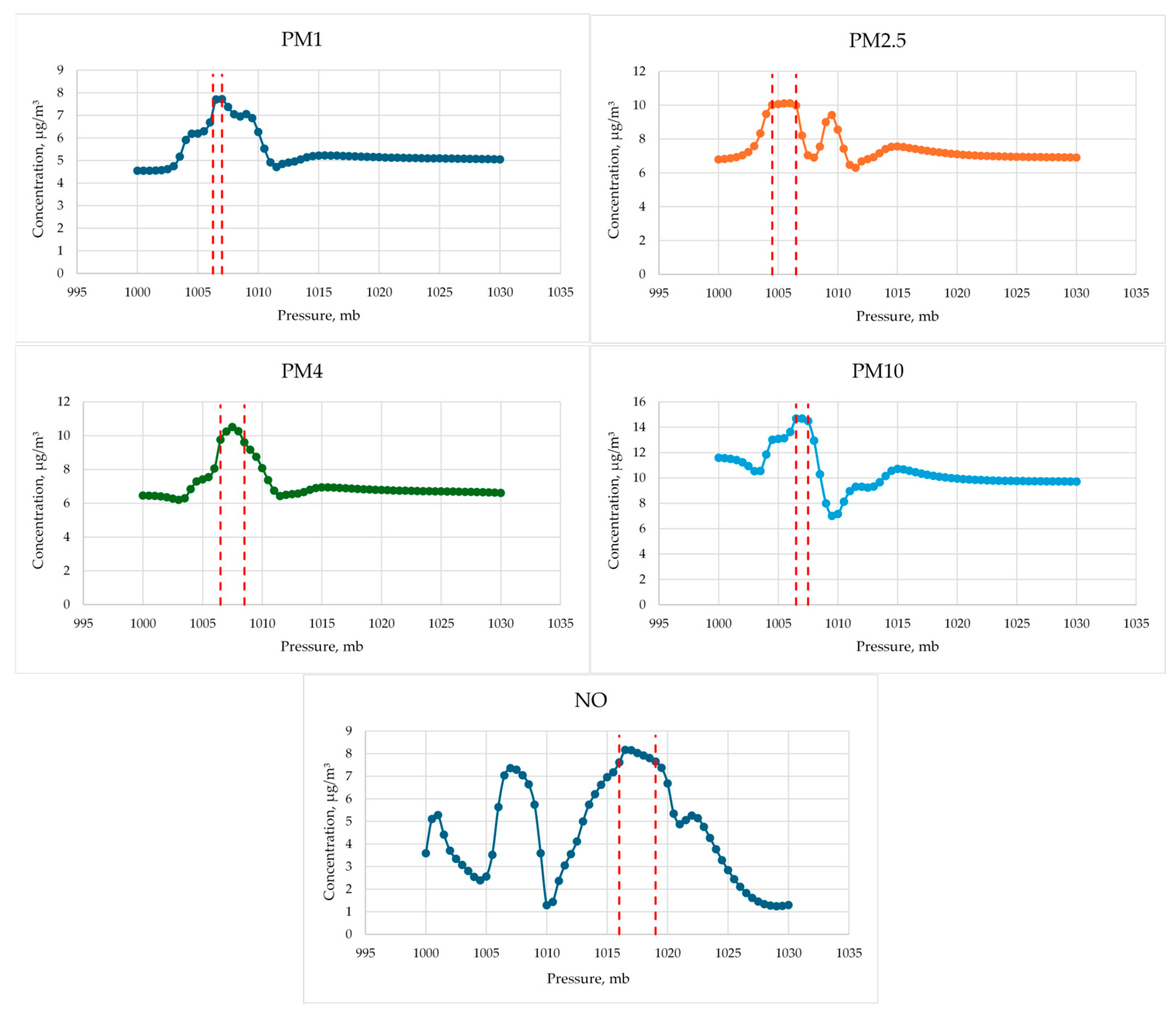

3.1. Suitable Conditions for Ship Pollution Dispersion in City Detection

3.2. Hotspot Identification Using AIS Data

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PM | Particulate matter |

| EPA | Environmental Protection Agency |

| NOx | Nitrogen oxides |

| WRF-Chem | Weather Research and Forecasting Chemical model |

| EMEP | The co-operative programme for monitoring and evaluation of the long-range transmission of air pollutants in Europe |

| AIS | Automatic identification system |

| MMSI | Maritime Mobile Service Identity |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Networks |

| KDE | Kernel Density Estimation |

| NO | Nitrogen oxide |

| PM1 | 1 µm particles |

| PM2.5 | 2.5 µm particles |

| PM4 | 4 µm particles |

| PM10 | 10 µm particles |

| IOC | Input-output correlation |

| MARPOL | International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| RMSE | Root Mean Squared Error |

| NRMSE | Normalized Root Mean Squared Error |

References

- Psaraftis, H.N. The Future of Maritime Transport. In International Encyclopedia of Transportation; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 535–539. ISBN 978-0-08-102672-4. [Google Scholar]

- Fratila, A.; Gavril, I.A.; Nita, S.C.; Hrebenciuc, A. The Importance of Maritime Transport for Economic Growth in the European Union: A Panel Data Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, L.; Wang, C.; Huang, R.; Liu, Z. An Approach for Traffic Pattern Recognition Integration of Ship AIS Data and Port Geospatial Features. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2024, 27, 2048–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission (Ed.) Facts and Figures on the Common Fisheries Policy: Basic Statistical Data: 2022; Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2022; ISBN 978-92-76-42605-9. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, D.; Uibel, S.; Takemura, M.; Klingelhoefer, D.; Groneberg, D.A. Ships, Ports and Particulate Air Pollution—An Analysis of Recent Studies. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2011, 6, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US EPA. NAAQS Table. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/criteria-air-pollutants/naaqs-table (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Aro, E.; Gorm Malý Rytter, N.; Itälinna, T. Maritime Industry Processes in the Baltic Sea Region/Synthesis of Eco-Inefficiencies and the Potential of Digital Technologies for Solving Them; Pan-European Institute, Turku School of Economics, University of Turku: Turku, Finland, 2020; p. 50. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, N.; Westerby, M.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M. Health Impact Assessments of Shipping and Port-Sourced Air Pollution on a Global Scale: A Scoping Literature Review. Environ. Res. 2023, 216, 114460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Jiang, H.; Zhao, H.; Stephens, B. Mobile Monitoring of Personal NOx Exposures during Scripted Daily Activities in Chicago, IL. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2017, 17, 1999–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Zhao, N.; Lang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, X. Contribution of Ship Emissions to the Concentration of PM2.5: A Comprehensive Study Using AIS Data and WRF/Chem Model in Bohai Rim Region, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 610–611, 1476–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firląg, S.; Rogulski, M.; Badyda, A. The Influence of Marine Traffic on Particulate Matter (PM) Levels in the Region of Danish Straits, North and Baltic Seas. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoyoglu, S.; Baltensperger, U.; Prévôt, A.S.H. Contribution of Ship Emissions to the Concentration and Deposition of Air Pollutants in Europe. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2016, 16, 1895–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, Á.; Yubero, E.; Galindo, N.; Crespo, J.; Nicolás, J.F.; Santacatalina, M.; Carratala, A. Quantification of the Impact of Port Activities on PM10 Levels at the Port-City Boundary of a Mediterranean City. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 281, 111842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, N.; Pey, J.; Reche, C.; Cortés, J.; Alastuey, A.; Querol, X. Impact of Harbour Emissions on Ambient PM10 and PM2.5 in Barcelona (Spain): Evidences of Secondary Aerosol Formation within the Urban Area. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 571, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Li, Y.; Li, G.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, H. Fluorescent Reconstitution on Deposition of PM2.5 in Lung and Extrapulmonary Organs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 2488–2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Hoek, G. Long-Term Exposure to PM and All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Environ. Int. 2020, 143, 105974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, R.W.; Fuller, G.W.; Anderson, H.R.; Harrison, R.M.; Armstrong, B. Urban Ambient Particle Metrics and Health: A Time-Series Analysis. Epidemiology 2010, 21, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.-H.; Kabir, E.; Kabir, S. A Review on the Human Health Impact of Airborne Particulate Matter. Environ. Int. 2015, 74, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorte, S.; Arunachalam, S.; Naess, B.; Seppanen, C.; Rodrigues, V.; Valencia, A.; Borrego, C.; Monteiro, A. Assessment of Source Contribution to Air Quality in an Urban Area Close to a Harbor: Case-Study in Porto, Portugal. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 662, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojić, F.; Gudelj, A.; Bošnjak, R. An Analytical Model for Estimating Ship-Related Emissions in Port Areas. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, U.; Kim, J.; Lee, H.; Lee, Y.G. Assessing the Effect of Long-Range Pollutant Transportation on Air Quality in Seoul Using the Conditional Potential Source Contribution Function Method. Atmos. Environ. 2017, 150, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leeuw, G.; Van Der A, R.J.; Bai, J.; Den Hoed, M.; Ding, J.; Guo, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, C.; Qin, K.; et al. Remote Sensing of Air Pollutants in China to Study the Effects of Emission Reduction Policies on Air Quality. J. Atmos. Sol.-Terr. Phys. 2024, 265, 106392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.B. An Introduction to Atmospheric Pollutant Dispersion Modelling. Environ. Sci. Proc. 2022, 19, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Smailys, V.; Strazdauskiene, R.; Bereisiene, K. Evaluation of a Possibility to Identify Port Pollutants Trace in Klaipeda City Air Pollution Monitoring Stations. Environ. Res. Eng. Manag. 2009, 4, 66–75. [Google Scholar]

- Chevet, E.; Boiron, O.; Anselmet, F. Modeling of Air Pollution Due to Marine Traffic in Marseille. Atmos. Environ. 2024, 329, 120542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Lara, O.O.; Ortega-Montoya, C.Y.; Prieto Hinojosa, A.I.; López-Pérez, A.O.; Baldasano, J.M. An Empirical and Modelling Approach to the Evaluation of Cruise Ships’ Influence on Air Quality: The Case of La Paz, Mexico. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 886, 163855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, Y.-L.; Cheng, W.-H.; Yuan, C.-S.; Lo, K.-C.; Lin, C.; Lee, C.-W.; Bagtasa, G. Impacts of Ship Emissions and Sea-Land Breeze on Urban Air Quality Using Chemical Characterization, Source Contribution and Dispersion Model Simulation of PM2.5 at Asian Seaport. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 347, 123663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toscano, D.; Marro, M.; Mele, B.; Murena, F.; Salizzoni, P. Assessment of the Impact of Gaseous Ship Emissions in Ports Using Physical and Numerical Models: The Case of Naples. Build. Environ. 2021, 196, 107812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boikos, C.; Siamidis, P.; Oppo, S.; Armengaud, A.; Tsegas, G.; Mellqvist, J.; Conde, V.; Ntziachristos, L. Validating CFD Modelling of Ship Plume Dispersion in an Urban Environment with Pollutant Concentration Measurements. Atmos. Environ. 2024, 319, 120261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojić, F.; Gudelj, A.; Bošnjak, R. A Comprehensive Model for Quantifying, Predicting, and Evaluating Ship Emissions in Port Areas Using Novel Metrics and Machine Learning Methods. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Rivera, A.I.; Mugica-Álvarez, V.; Sosa Echeverría, R.; Sánchez Álvarez, P.; Magaña Rueda, V.; Vázquez Cruz, G.; Retama, A. Air Quality and Atmospheric Emissions from the Operation of the Main Mexican Port in the Gulf of Mexico from 2019 to 2020. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Park, Y.; Kim, G.; Yoo, J.; Pinzon-Acosta, C.; Gonzalez-Olivardia, F.; Cruz, E.; Lee, H. Ship Air Emission and Their Air Quality Impacts in the Panama Canal Area: An Integrated AIS-Based Estimation During Hotelling Mode in Anchorage Zone. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Park, D.; Choo, S.; Pham, H.T. Estimation of the Non-Greenhouse Gas Emissions Inventory from Ships in the Port of Incheon. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency (Ed.) EMEP/EEA Air Pollutant Emission Inventory Guidebook 2023: Technical Guidance to Prepare National Emission Inventories; EEA Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2023; ISBN 978-92-9480-598-0. [Google Scholar]

- Maritime & Trade: Shipping Intelligence. Available online: https://www.spglobal.com/market-intelligence/en/solutions/maritime-shipping-intelligence (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Orai Klaipėda—Ankstesnė Orų Informacija, Pateikiama Kiekvieną Dieną|Freemeteo.Lt. Available online: https://freemeteo.lt (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Air Quality Monitoring—Technical Specifications. Available online: https://www.aqmesh.com/products/technical-specification/ (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Rito, J.E.; Lopez, N.S.; Biona, J.B.M. Modeling Traffic Flow, Energy Use, and Emissions Using Google Maps and Google Street View: The Case of EDSA, Philippines. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šilas, G.; Rapalis, P.; Lebedevas, S. Particulate Matter (PM1, 2.5, 10) Concentration Prediction in Ship Exhaust Gas Plume through an Artificial Neural Network. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golbazi, M.; Archer, C. Impacts of Maritime Shipping on Air Pollution along the US East Coast. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2023, 23, 15057–15075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sensor | Type | Units | Range | Precision | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NO | Electrochemical | ppb or µg/m3 | 0–6700 ppb | >0.9 | 1 ppb |

| PM1 | Optical particle counter | µg/m3 | 0–100,000 µg/m3 | >0.9 | 5 µg/m3 |

| PM2.5 | Optical particle counter | µg/m3 | 0–150,000 µg/m3 | >0.9 | 5 µg/m3 |

| PM4 | Optical particle counter | µg/m3 | 0–225,000 µg/m3 | >0.9 | 5 µg/m3 |

| PM10 | Optical particle counter | µg/m3 | 0–250,000 µg/m3 | >0.85 | 5 µg/m3 |

| Humidity | Solid state | % | 0 to 100% | >0.9 | 5% RH |

| Pressure | Solid state | mb | 500 to 1500 mb | >0.9 | 5 mb |

| Parameter | Range | Incremental Step | Measuring Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | 0–20 | 0.5 | °C |

| Pressure | 1000–1030 | 0.5 | mb |

| Humidity | 40–100 | 0.5 | % |

| Wind speed | 0.5–15 | 0.5 | m/s |

| Wind direction | 225–315 | 0.5 | ° |

| Condensation point | 0–15 | 0.1 | °C |

| Cloudiness 1 | 1–5 | 1 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rapalis, P.; Šilas, G.; Daukšys, V.; Šaparnis, L.; Dukanauskaitė, K.; Lileikytė, A. Detection of Ship-Related Pollution Transported into Klaipeda City. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2026, 14, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010010

Rapalis P, Šilas G, Daukšys V, Šaparnis L, Dukanauskaitė K, Lileikytė A. Detection of Ship-Related Pollution Transported into Klaipeda City. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2026; 14(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010010

Chicago/Turabian StyleRapalis, Paulius, Giedrius Šilas, Vygintas Daukšys, Lukas Šaparnis, Karolina Dukanauskaitė, and Austėja Lileikytė. 2026. "Detection of Ship-Related Pollution Transported into Klaipeda City" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 14, no. 1: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010010

APA StyleRapalis, P., Šilas, G., Daukšys, V., Šaparnis, L., Dukanauskaitė, K., & Lileikytė, A. (2026). Detection of Ship-Related Pollution Transported into Klaipeda City. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 14(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010010