1. Introduction

Recent advancements in sensor technology, computing devices, and marine science have led to an increased application of Unmanned Underwater Vehicles (UUVs) in fields such as pipeline monitoring, marine surveying, underwater sampling, and mine detection [

1,

2,

3]. Multi-UUV systems have shown significant advantages in functional redundancy, cooperative operations, and flexibility, making them a prominent focus of current research. Formation control, a central challenge in these systems, involves formation generation, maintenance, and reconfiguration, and has garnered significant attention [

4,

5]. In practical applications, multi-UUV systems often need to dynamically reconfigure their formations to achieve specific objectives, such as minimizing energy consumption, safeguarding designated targets, or enabling coordinated marine environmental monitoring. Consequently, the development of effective and safe formation reconfiguration strategies is of paramount importance for advancing both the theoretical foundations and engineering applications of multi-UUV systems.

Multi-UUV formation reconfiguration refers to the process of transitioning a multi-UUV system from an arbitrary initial formation to a target formation through information exchange and cooperative movement. Current research on formation reconfiguration in multi-agent systems primarily employs optimization techniques, including artificial potential fields, affine transformations, reinforcement learning, and differential evolution. For instance, graph rigidity and affine transformations (GR-AT) have been utilized to address formation reconfiguration challenges in multi-UUV systems [

6,

7]. To address dynamic environmental factors, an improved artificial potential field-based approach enables UUVs to avoid both static and dynamic obstacles under external disturbances [

8]. Additionally, artificial potential fields have been applied to reconfigure formations after individual failures, ensuring collision avoidance within the multi-UUV system [

9]. Other methods combine sensor data-driven transformation rules with control matrices and artificial potential fields to achieve reconfiguration [

10]. Beyond UUV systems, innovative techniques have been explored in other domains. For example, model predictive control combined with differential evolution has been applied to unmanned aerial vehicles, enabling distributed planning and control for formation reconfiguration [

11]. In spacecraft systems, reinforcement learning-based approaches, such as Q-learning, have been employed to facilitate reconfiguration while ensuring inter-agent collision avoidance through shared learning [

12]. Less conventional methods have also been introduced, such as a model-based interfered fluid dynamical system (MIFDS), which balances reconfiguration and obstacle avoidance while respecting kinematic constraints [

13], and control barrier functions with quadratic programming to optimize reconfiguration trajectories and ensure collision avoidance [

14].

Multi-UUV systems are distinct from other multi-agent systems as they operate in underwater environments. Due to strong absorption and scattering of electromagnetic waves in seawater, transmission ranges are significantly shortened, making underwater acoustic communication the primary method for information exchange in multi-UUV systems [

15]. The propagation characteristics of sound in water and the bandwidth of sonar channels lead to substantial delays and intermittency [

16,

17]. Consequently, designing effective communication compensation methods under acoustic conditions has become a critical research focus in multi-UUV systems [

18,

19]. Moreover, underwater acoustic communication delays are time-varying and susceptible to packet loss. Reference [

20] introduces a gradient descent-based delay estimator and validates its effectiveness through pool experiments. In contrast, reference [

21] utilizes kernel density estimation and curve fitting to address issues related to communication discretization and packet loss. Reference [

22] develops a discretized UUV control method, proving the consistency of formation control under packet loss via matrix and Schuler theory. Reference [

23] derives a nonlinear time-varying delay model for cooperative localization systems, converting delays into measurement deviations and reconstructing equations using Kalman filtering. However, most studies have focused on formation control and consistency analysis under underwater acoustic communication. Furthermore, the communication intervals and delay times of acoustic devices used in these studies are not consistent with actual operating conditions.

The research is structured into the following parts. First, the foundation of formation reconfiguration lies in designing control methods enabling follower UUVs to execute coupled movements while tracking the leader. A grid-based horizontal space model is established with the leader as a reference, and a basic motion strategy for followers is defined. This intuitive and effective approach facilitates deriving control commands for follower movements.

Next, the core focus is collision avoidance and path planning. This paper addresses the multi-objective optimization of formation reconfiguration in two stages. The first stage uses Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) to allocate desired positions for follower UUVs in the target formation (“which point to go”), while the second applies PSO to generate guide path points (“how to go”). The first stage minimizes path intersections and movement distances, and the second ensures accurate and efficient reconfiguration.

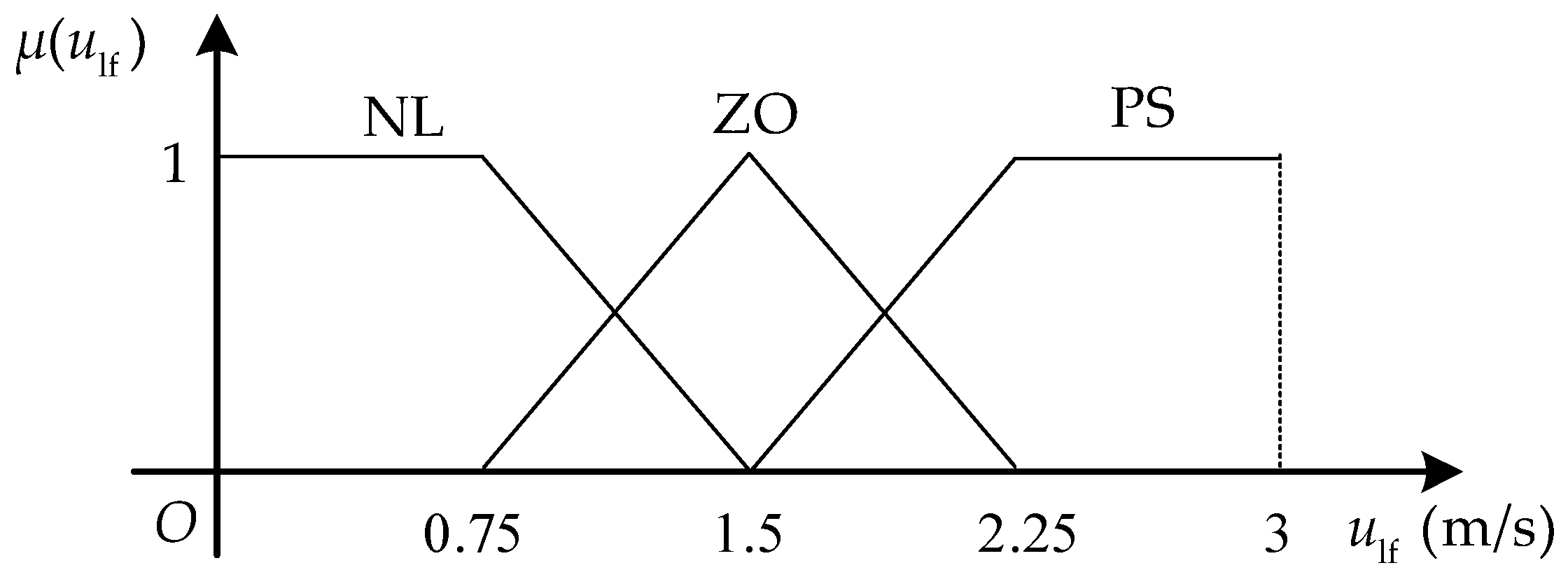

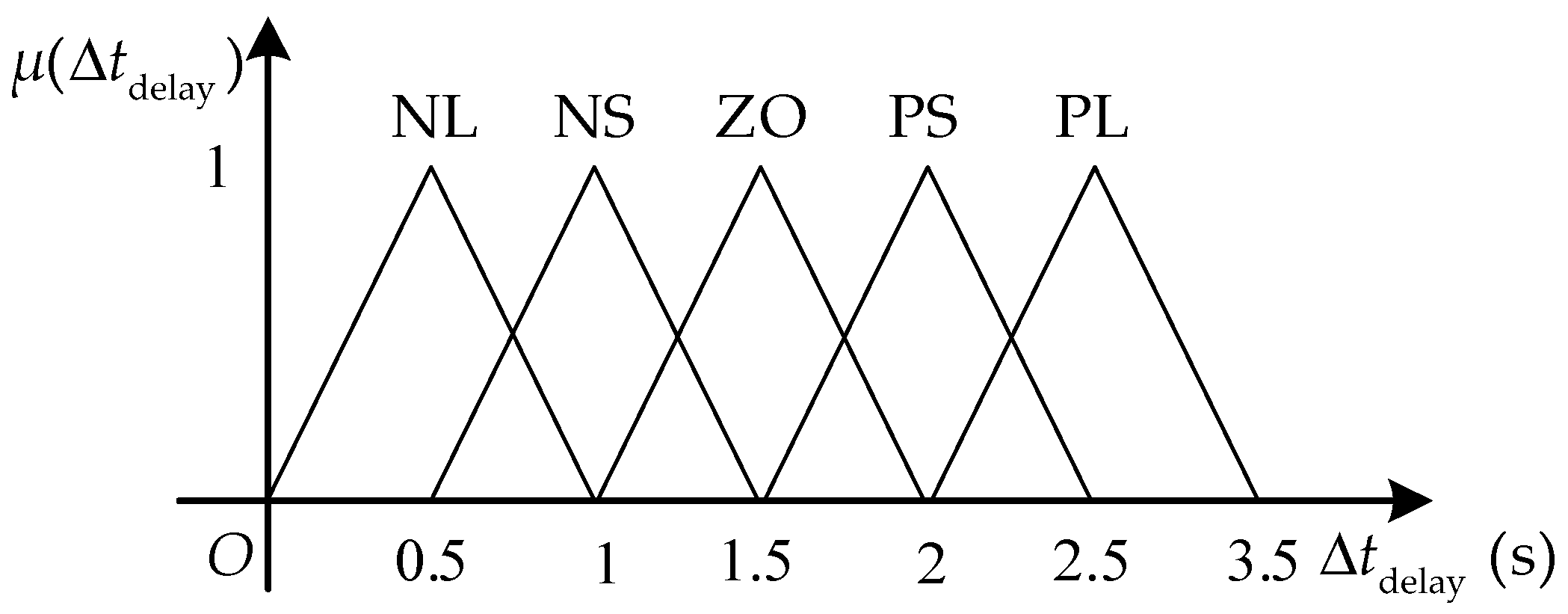

Finally, communication constraints inherent in formation reconfiguration are addressed. Considering the practical limitations of underwater acoustic communication, this paper explores a centralized data transmission model and proposes a fuzzy theory-based delay estimation algorithm. This algorithm minimizes the impact of delays and failures on control command transmission, improving system robustness and efficiency.

The main contributions of this paper are:

A horizontal geometric grid model for multi-UUV dynamic formation reconfiguration is established, with dispersion and maneuver-based methods for follower movement. A collision-free planning scheme is proposed based on specific formation requirements.

A PSO-based method is developed for allocating desired formation positions and movement path points. The algorithm determines target coordinates under various constraints, guiding followers during reconfiguration.

A fuzzy theory-based underwater communication delay estimation method is proposed, addressing centralized formation control under communication delays and bandwidth constraints. A control command transmission method is designed to enhance formation reconfiguration robustness.

The paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 presents the problem statement.

Section 3 establishes the horizontal grid model and defines follower motion strategies.

Section 4 discusses maneuvering methods and the PSO-based planning approach.

Section 5 introduces the fuzzy-based communication delay estimation method.

Section 6 provides simulation results, and

Section 7 concludes the paper.

2. Problem Statement

This paper primarily investigates the issue of formation reconfiguration for follower UUVs while tracking the leader UUV. In this study, the leader UUV is assumed to maintain constant speed and linear motion throughout the reconfiguration process. During the reconfiguration process, the leader UUV applies a PSO algorithm to compute the maneuvering position of each follower UUV. This allows the problem of formation reconfiguration to be transformed from a global coordinate system into the moving coordinate frame of the leader UUV, and subsequently into a grid-based space. The focus is then on the allocation of relative positions for each follower UUV, which correspond to the desired point in the target formation. These relative positions are then converted into velocity and heading instructions, with the length of each instruction sequence dynamically adjusted based on communication delays. Upon receiving these commands, the followers complete the reconfiguration using their speed and heading controllers. This study centers on path planning for multi-UUV formation reconfiguration, where the output consists of velocity and heading commands for the followers. External factors like sea currents or chaotic fluctuations may affect control performance but are not the primary focus of this research.

2.1. Communication Topology and Delay Analysis

First, the communication model of the multi-UUV system studied in this paper is described. The multi-UUV system under study is based on a leader-follower centralized formation structure, as illustrated in

Figure 1. The system utilizes a hybrid measurement-communication method. The leader UUV serves as the communication hub, equipped with an ultra-short baseline (USBL) positioning sonar array, while the followers are equipped with responders. The leader UUV periodically transmits acoustic pulses, which are received and responded to by the responders on the follower UUVs. These response pulses are then utilized by the leader to determine the relative positions of all follower UUVs [

24,

25]. The leader then broadcasts the measured relative positions of the followers and other necessary instructions to all followers. This dual-mode communication system not only minimizes system cost but also reduces communication cycles compared to systems that rely solely on acoustic communication.

Under the described communication method, the follower UUVs are unable to transmit information externally. As a result, the leader UUV is designated as the decision-maker, centrally planning the movements of all followers. Specifically, the control commands for the follower UUVs are determined by the leader and transmitted to the followers via acoustic communication. The acoustic communication employs a broadcast mode, where the leader UUV transmits control command information to all followers simultaneously during each communication instance. Considering the characteristics of underwater robotic formation communication, the following issues are addressed:

Unlike radio communication, acoustic sonar cannot sustain high communication frequencies, resulting in relatively long intervals between data transmissions. The time interval between each acoustic broadcast is denoted as . In other words, the leader UUV broadcasts control command information to the followers once every seconds.

Due to the complexity and uncertainty of the ocean environment, communication failures may occur. It is assumed in this study that consecutive failures in acoustic broadcast communication will not occur. Specifically, if a communication failure occurs during the broadcast at time t, the broadcast at time will be successful.

The conversion of data into acoustic signals and the propagation of sound in water require a certain amount of time, leading to a time delay in the transmission of information. That is, the broadcast communication transmitted by the leader UUV at time t will be received by the followers at time , where represents the transmission delay.

The total amount of data transmitted in a single instance is constrained by the communication bandwidth. Thus, an appropriate amount of communication data must be selected. From a practical perspective, the minimum data volume that ensures the continuity of control commands should be chosen.

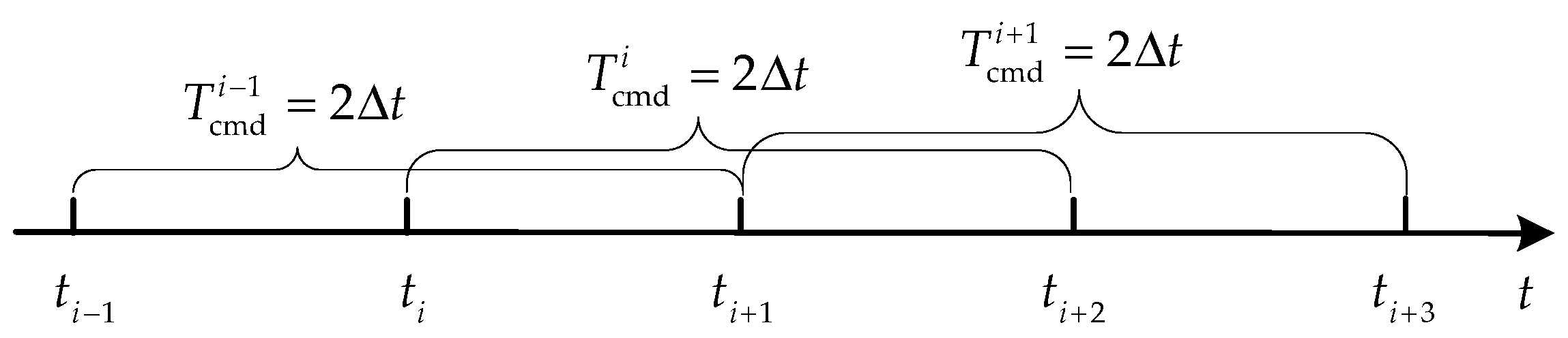

Let represent the length of the control command sequence sent by the leader UUV to the followers during the i-th broadcast cycle. This sequence includes heading and velocity commands for a time duration of . Based on the above considerations, the problem of acoustic communication can be described as follows:

Firstly, the issue of communication intervals in underwater acoustic communication is considered. To ensure the continuity of control instructions for the follower UUV, the leader UUV transmits a control command sequence of duration to the follower UUV at intervals of .

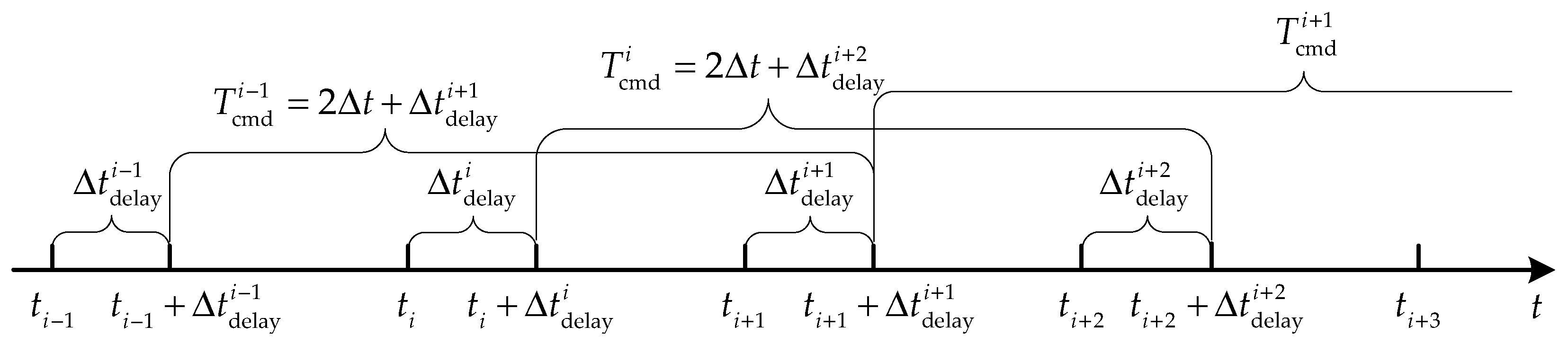

Secondly, the problem of communication failure in underwater acoustic communication is addressed. If we assume communication failure occurs at time

, and the length of each control command sequence is

. A command vacuum period of duration

will arise for the follower UUV between times

and

. To mitigate the impact of communication failure while considering the bandwidth limitations, the duration of the transmitted control command sequence must be extended. Under the condition that the communication interval remains

, the leader UUV can ensure the temporal continuity of the follower UUV’s control instructions by transmitting a control command sequence of duration

during each interval. As illustrated in

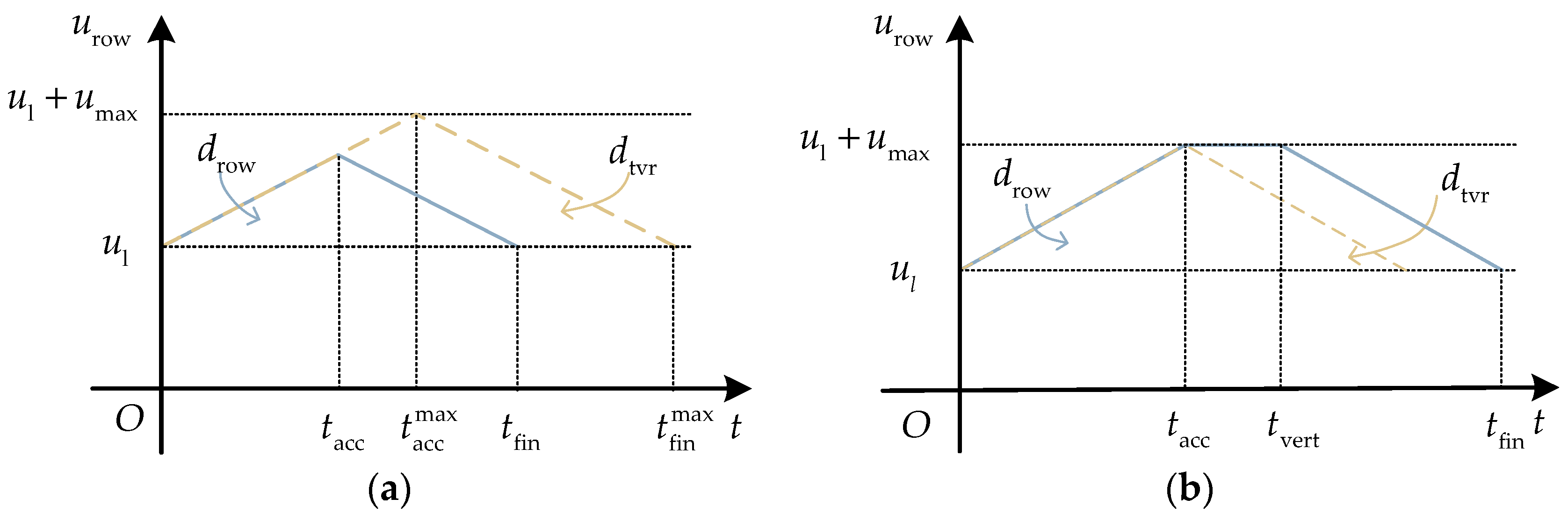

Figure 2, if the length of each control command sequence is set to

, the continuity of control commands for the followers can be ensured even under intermittent communication failures.

Finally, the issue of acoustic propagation delay in underwater communication is considered. The control command sequence must also account for the acoustic delay time,

. As shown in

Figure 3, the control command sequence transmitted by the leader UUV at time

can only be received by the follower UUV at time

. Although the follower UUV receives a control command sequence of duration

, the effective command sequence duration is from

to

. Therefore, to ensure the continuity of the follower UUV’s control instructions, the command sequence transmitted by the leader UUV at time

must be of duration

, which includes both the acoustic communication interval

and the acoustic delay time

.

In summary, considering the various issues that may arise during underwater acoustic communication, the length of the control command sequence transmitted by the leader UUV to the follower UUV in a single transmission should be set to . Determining how to calculate the acoustic delay time to ensure uninterrupted command transmission during the multi-UUV formation reconstruction process will be the primary focus of subsequent research.

2.2. Technical Method of Formation Reconfiguration

In this study, the multi-UUV system consists of one leader and four followers, all of which are located on the same horizontal plane. To avoid collisions, individual vehicles in a formation can be spread across different depths. However, multi-UUV systems often need to operate at the same depth in practice, such as during horizontal plane or deep diving operations. Therefore, depth variations are not considered in this study, as excluding them does not simplify the formation reconfiguration problem and is necessary for the study’s scope. During the formation reconfiguration process, the leader UUV maintains a constant linear motion with a heading angle of and a velocity of . The desired relative positions of the followers before and after the formation reconfiguration are pre-defined and known to the leader UUV. At the initial moment, all followers are located at their respective desired positions and have the same heading angle and velocity as the leader UUV. Under these conditions, the followers are required to follow the leader while avoiding collisions with other UUVs, ultimately reaching their desired positions in the new formation.

To enable the followers to simultaneously follow the leader and perform formation reconfiguration, a basic motion strategy based on a grid space is defined for the follower UUVs. Based on this motion strategy, a basic motion sequence generation approach is designed to prevent collisions between UUVs.

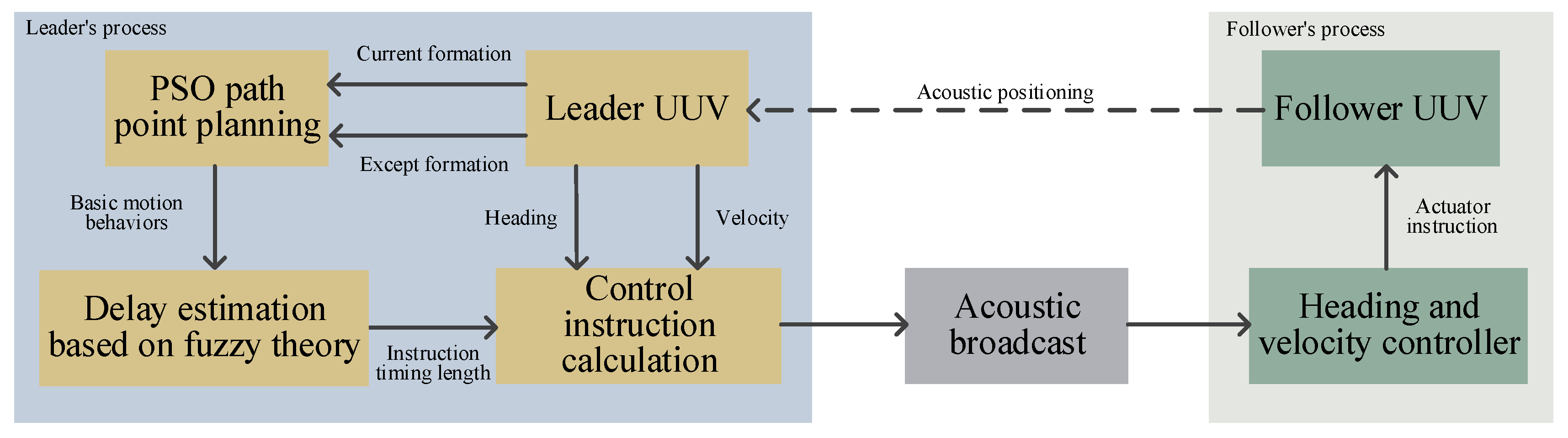

Given the communication topology of the UUV formation, a centralized decision-making approach is adopted in this study. The overall technical framework is illustrated in

Figure 4. Before the initiation of the formation reconfiguration, the leader UUV employs the PSO method to optimize the basic motion sequences for all followers. The leader UUV then broadcasts the optimization results to the follower UUVs. Based on the received motion sequences, each follower generates its respective control and guidance commands. Formation reconfiguration is initiated at the same time for all UUVs to minimize the impact of communication delays on the formation system.

3. Grid Space and Motion Mode

In the context of the multi-UUV formation reconfiguration problem, avoiding collisions among UUVs is of utmost importance. To generate control commands for the follower UUVs more safely and effectively while ensuring successful formation reconfiguration, the grid method is employed in this study to model the horizontal plane where the leader UUV operates.

3.1. Establishment of 2D Grid Space Model

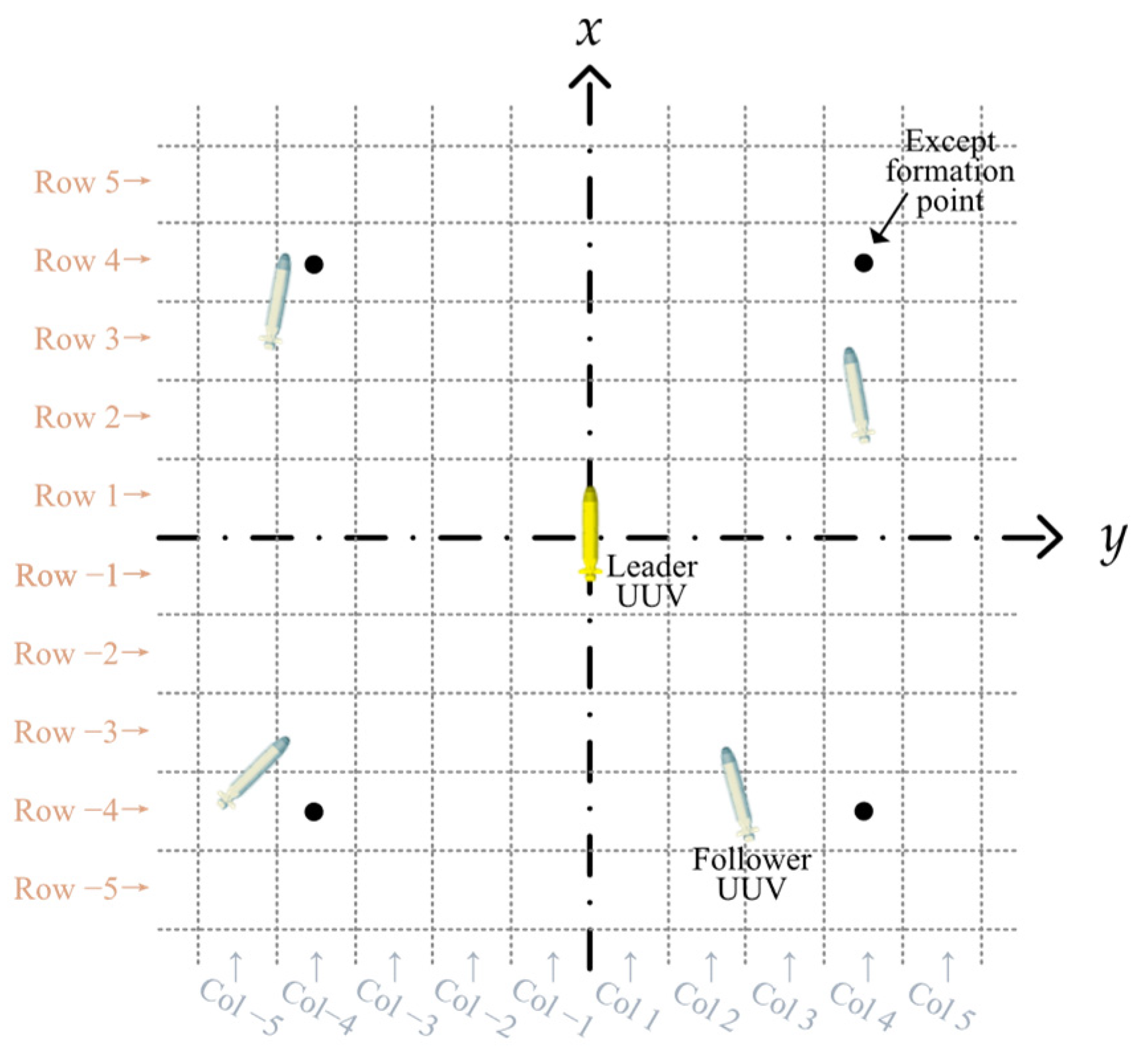

As illustrated in

Figure 5, in a relative coordinate system, horizontal and vertical lines are used to divide the plane into row and column regions with uniform spacing, which are then encoded. Straight lines parallel to the y-axis, denoted as

, are used to divide the 2D space into multiple row regions along the x-axis direction, where

represents the interval between adjacent lines. The row regions are assigned positive encoding values in the positive x-axis direction. Similarly, straight lines parallel to the x-axis, denoted as

, divide the 2D space into multiple column regions along the y-axis direction, where

represents the interval between adjacent lines. The column regions are assigned positive encoding values in the positive y-axis direction.

Here,

and

are integers representing the dimensions of the grid space. Based on the positions of all UUVs in the system and their desired positions in the formation, the dimensions of the grid space are restricted as follows:

where

,

,

, and

denote the minimum and maximum column and row indices, respectively. Their specific values are determined by the grid spacing

and the positions of UUVs before and after the formation reconfiguration. These constraints ensure that the follower UUVs remain within the grid space. Without loss of generality, an additional parameter

, representing the number of followers, is included in the constraints. For this study,

.

In this manner, the planar space, with the leader UUV as the origin, is divided into

regions. To reduce the computational complexity of the subsequent optimization algorithm, a unified numbering scheme is applied to the regions. As illustrated in

Figure 5, the regions are sequentially numbered from left to right and top to bottom. This ensures that each region is assigned a unique identifier, denoted as

G. To facilitate subsequent calculations, a method for converting any point’s coordinates in the global coordinate system to the region identifier

G is provided below:

For a point

P located at

in the global coordinate system, with the leader UUV positioned at

and oriented at an angle

relative to the north direction, the corresponding coordinates of

P in the relative coordinate system, denoted as

, are given. The row and column indices of

in the horizontal grid space can be expressed as

. The relationship among these coordinates is described as follows:

If

, then specify

; If

, then

is specified. And the relationship between

and the region identifier

G is described as follows:

where

represents the maximum row and column values in the regions.

3.2. Basic Motion Behavior in Grid Space

Due to the complexity of the underwater environment and poor communication conditions, UUVs face an increased risk of collision during the process of formation reconfiguration. Therefore, the selection of maneuvering strategies for follower UUVs during the formation reconfiguration process is critically important.

As shown in

Figure 6b, within the horizontal grid space model based on a relative coordinate system, follower UUVs are restricted to only two basic motion modes:

Row motion: motion parallel to the x-axis within the same column region, which changes only the row coordinate of the follower UUV.

Column motion: motion parallel to the y-axis within the same row region, which changes only the column coordinate of the follower UUV.

It can be readily deduced that using these basic motion modes allows follower UUVs to reach any point in the horizontal grid space model. Based on the defined motion methods, multiple motions are required for a follower UUV to avoid collisions. This article proposes a four-step motion planning method, including dispersal motion for individual separation and maneuvering motion to guide individuals towards target locations. This article specifies two possible motion sequences for follower UUVs during formation reconfiguration:

Column dispersion, Row dispersion, Column maneuvering, Row maneuvering.

Row dispersion, Column dispersion, Row maneuvering, Column maneuvering.

As shown in

Figure 6a, when a follower UUV moves from its initial position to the desired target point, the motion sequence can be divided into column dispersion, row dispersion, column maneuvering, and row maneuvering. Two types of motion sequences are equivalent. It is worth noting that the first type of motion sequence is preferred in this article (column dispersion, row dispersion, column maneuvering, row maneuvering).

In this study, a four-step maneuvering strategy is proposed instead of the traditional two-step maneuvering approach, which includes only row and column motions. This is because, in certain special cases, such as when a follower UUV and the leader UUV are in the same row or column, the follower UUV cannot reach its target position while avoiding the leader UUV with only two motions. The proposed strategy ensures that all follower UUVs can move to their desired positions in the coordinate system established with the leader UUV as the origin, forming the desired formation during reconfiguration.

To optimize the paths of the follower UUVs during formation reconfiguration and ensure the safety of both the follower and leader UUVs, this study employs the PSO algorithm to plan the regions indices for the follower UUVs’ distributed motions and their target positions.

4. Path Point Planning for Formation Reconfiguration

The PSO algorithm is a population-based optimization method inspired by the foraging behavior of bird flocks. It is well suited for our highly nonlinear and multimodal optimization problem, providing an effective balance between exploration and exploitation without requiring gradient information. Compared with other population-based metaheuristics, PSO uses fewer control parameters and typically achieves faster convergence, and its extensive record of success in structurally similar problems further supports its adoption in this study. In PSO, the movement of each particle is influenced by both its own experience and the behavior of the entire swarm, while the quality of each particle is evaluated through a predefined fitness function. Consequently, particle selection and fitness-function design are critical components of the optimization process. Based on these considerations, this section first analyzes the formation-reconfiguration path-planning problem from the perspectives of particle representation and fitness-function construction, and then presents the specific steps of the dynamic PSO-based path-planning method.

4.1. Selection and Dimensionality Reduction of PSO Particles

In the planning process of the grid-based multi-UUV formation reconfiguration method, collision avoidance among UUVs must be ensured. Therefore, the motion paths of UUVs must be carefully designed. The quality of the planned paths is primarily evaluated using the fitness function of the PSO algorithm, which serves as the sole evaluation criterion. The efficiency of the fitness function directly affects the optimization results produced by the PSO algorithm. Based on the proposed motion strategy for formation reconfiguration, the PSO algorithm is applied to uniformly plan four maneuvers for each follower UUV. Theoretically, four target points need to be planned for each follower UUV. Let the position of a particle in the PSO algorithm be denoted as . the motion target point of the m-th follower is represented as . This includes the column region coordinate for column dispersion , the row region coordinate for row dispersion , the column region coordinate for column maneuvering , and the row region coordinate for row maneuvering . The four motion target points’ row and column region coordinates are then derived based on the initial row and column positions of the follower UUVs, the desired target positions in the formation, and the properties of the four-maneuver strategy.

In the proposed PSO-based reconfiguration path planning method, the final particle position information serves as a feasible solution to the formation reconfiguration problem and constitutes the smallest unit of the algorithm. The dimensionality of the particle corresponds to the dimensionality of the solution space. According to the above analysis, the particles in the optimization algorithm are represented as a matrix. However, the high dimensionality of the particles reduces the efficiency of the optimization process and negatively impacts the results.

In

Section 3.1, the regions were assigned unique identifiers, denoted as

G. t is evident that each identifier

G uniquely corresponds to a pair of row and column values. Therefore, the region identifiers

and

can be used to replace

and

, respectively. As a result, in the PSO algorithm, a particle

, can be represented as

, effectively reducing the particle’s dimensionality to 2. Specifically,

.

4.2. Design of Fitness Function for PSO Algorithm

During the formation reconfiguration process, the primary evaluation criterion is safety, followed by efficiency. Safety is ensured by preventing collisions between the follower UUVs and other UUVs during the reconfiguration process. Efficiency is evaluated based on the maneuvering distance of all follower UUVs within the relative coordinate system. The design of the fitness function is approached from two perspectives: safety and efficiency. For the convenience of description, is used to represent the coordinates of the follower UUV in the relative coordinate system, which can be calculated using Equation (2). Let and denote the coordinates of the region centers of and , respectively, in the relative coordinate system.

Efficiency Metric: The formation reconfiguration method proposed in this paper is achieved by the follower UUVs maneuvering relative to the leader. Therefore, the evaluation of reconfiguration efficiency can be conducted by calculating the maneuvering distance of each follower UUV relative to the leader. To achieve rapid and efficient multi-UUV formation reconfiguration, the total maneuvering path length of all UUVs must be minimized. Therefore, the efficiency metric function

is defined as follows:

Safety Metric: To ensure collision-free formation reconfiguration, the horizontal workspace is discretized into grid regions, and potential collision scenarios both follower–follower and leader–follower are analyzed. Corresponding constraint functions are incorporated into the optimization model to restrict unsafe dispersion values and avoid trajectory intersections. These constraints, together with the grid regions discretization, provide inherent separation among UUVs. A detailed description of the safety constraint design is given below.

Different row and column regions: In the four-step maneuvering method for followers defined in

Section 3.2, the first two dispersion motions aim to increase the dispersion of followers, thereby preventing collisions. Therefore, it is desired that the follower UUVs remain as separated as possible, avoiding the same row and column regions after the row and column spreading maneuvers. A function

for different row and column dispersion is defined as:

Assignment of Desired Positions: At the end of the reconfiguration process, each follower UUV must occupy a distinct desired position in the target formation. To ensure this one-to-one correspondence between follower UUVs and target positions, a conflict function for desired positions

is defined as:

Non-One Row and Column Dispersion Values: To prevent collisions between follower UUVs and the leader during the column and row maneuvering phases, it must be ensured that the absolute values of the row and column dispersion coordinates are non-one. Because the leader UUV is always in the first row and first column. A constraint function is defined as: A constraint function

is defined as:

Safety During Column Dispersion: During column dispersion, the starting and ending positions of the follower UUV may intersect with the leader UUV’s path, posing a significant collision risk. To mitigate this risk, a collision function

(leader with follower) for column dispersion is defined as follows:

During row dispersion, follower UUVs move along different column regions without risk of collision. However, during column dispersion, changes in the relative positions of follower UUVs within the same row region could lead to path intersections and collisions. To ensure relative positions are maintained during column dispersion, a conflict function

(follower with follower) is defined as:

Safety During Row Maneuvering: During row maneuvering, the starting and ending positions of the follower UUV may intersect with the leader UUV’s path, posing a significant collision risk. To mitigate this risk, a collision function

(leader with follower) for row maneuvering is defined as follows:

During column maneuvering, follower UUVs move along different row regions without risk of collision. However, at the end of column maneuvering, multiple follower UUVs may occupy the same column region, and any changes in their relative positions during row maneuvering could lead to path intersections and collisions. To ensure safety, relative positions within the same column region must remain unchanged during row maneuvering. A conflict function

(follower with follower) is defined as:

Considering the evaluation functions, the comprehensive particle fitness function

is defined as follows:

Here, and are adaptive weighting coefficients, with their values ranging between 0 and 1, and satisfying the condition .

4.3. Steps for Path Point Generation Based on PSO

By integrating the basic PSO algorithm with the previously defined particle fitness function, the detailed steps for PSO in allocating four maneuvering path regions coordinates for follower UUVs during the formation reconfiguration process are presented as follows:

Step 1: Space Grid Discretization. Based on the coordinates of the initial positions of the follower UUVs and the desired formation positions in the relative coordinate system, the space is discretized into grid regions, resulting in the determination of the number and indexing of regions.

Step 2: Initialization of Algorithm Parameters. Prior to iterative execution, the PSO algorithm necessitates the initialization of several key parameters. These include the learning factors

and

, the maximum number of iterations

, the maximum allowable iterations for result stabilization

, and the random initial positions of the particles. Additionally, the maximum velocity of the particles in the solution space is defined as:

where

represents the maximum row and column values in the regions.

Step 3: Calculation of Particle Fitness. At iteration k, the position of the i-th particle is represented as , and its velocity is denoted as , where d represents the dimensionality of the solution space, , and n is the number of particles in the solution space. Based on the defined fitness function and the particle position information , the corresponding fitness value is calculated.

Step 4: Best Position Updates. After obtaining the fitness values of the particles, each particle updates and records the position , corresponding to its current minimum fitness value. Subsequently, the fitness values of all particles are compared to determine the optimal position of the entire population.

Step 5: Update of Particle Velocity and Position. Using the following equations, the inertia weight

at the current iteration is calculated, followed by the velocity

and position

of the particle at the next iteration:

where

is the current iteration,

and

are the maximum and minimum inertia weights, respectively.

and

are random numbers uniformly distributed in the interval [0, 1].

and

are the learning factors initialized in Step 2. where

denotes the floor function, which rounds a number down to the nearest integer. The velocity of all particles must satisfy the following constraint:

Step 6: Termination Condition Check. The following termination conditions are checked. If any condition is satisfied, the result corresponding to the optimal fitness value is output, providing the regions indices of the follower UUVs after the dispersion maneuver. If none of the conditions are satisfied, the algorithm proceeds to Step 4.

The flowchart of the planning algorithm is shown in

Figure 7. After completing the above operations, the optimal results obtained from the PSO algorithm can be transformed using the method described in

Section 3.1, yielding the desired path point coordinates for the follower UUVs in the relative coordinate system at each stage.

6. Simulations

To validate the feasibility of the proposed multi-UUV formation reconfiguration method under underwater acoustic communication delays, simulation experiments were conducted using specialized simulation software.

Firstly, the relevant parameters for the simulation experiments were defined. The adjacent interval between row and column regions in the horizontal grid model was set to . The multi-UUV system consisted of one leader and four followers. The underwater acoustic communication interval . The leader UUV had a heading angle and a velocity in the global coordinate system. The maximum acceleration time for row and column motions , and the maximum relative velocity for row and column motions was .

In this formation reconfiguration simulation, the initial formation of the multi-UUV system was rectangular, while the desired formation was triangular. The initial position information of the follower UUVs in the relative coordinate system is presented in

Table 2, and the desired formation position information is shown in

Table 3.

For the PSO algorithm, the dimensionality of particles was set to 2, the number of particles in the swarm . The learning factors , and the maximum and minimum inertia weights . The fitness function weighting coefficient . The optimal position iteration count , and the maximum number of iterations .

The movement trajectories of the UUVs during the simulation are shown in

Figure 13. At the initial moment (

t = 0 s), the follower UUVs were distributed around the leader UUV, forming a rectangular formation. At this time, the leader UUV assigned initial positions and planned the target points for formation reconfiguration for each follower. Navigation and velocity control commands were periodically transmitted to the followers via simulated underwater acoustic communication. After 1912.5 s, the formation reconfiguration was completed, transforming the initial rectangular formation into the desired triangular formation.

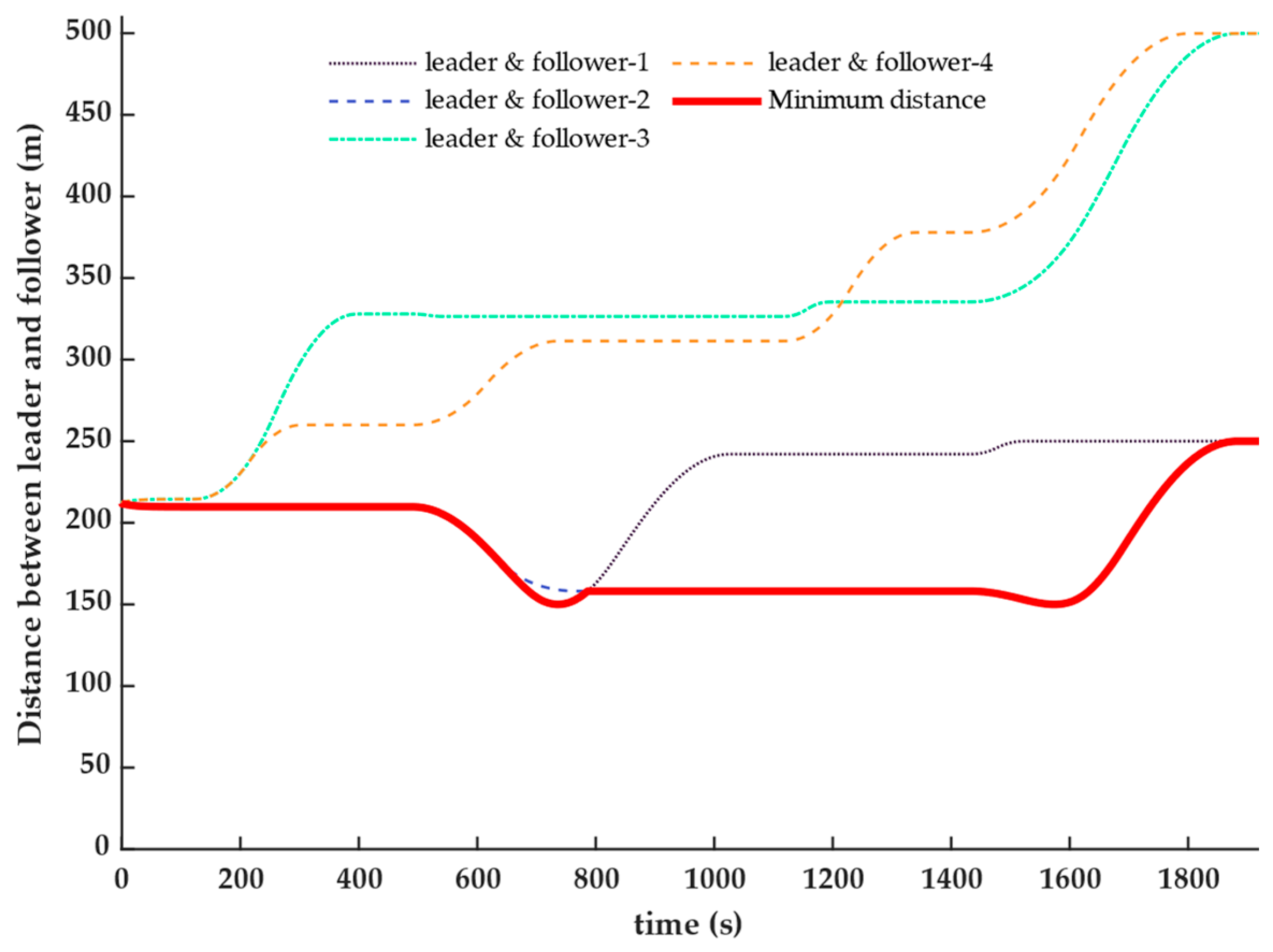

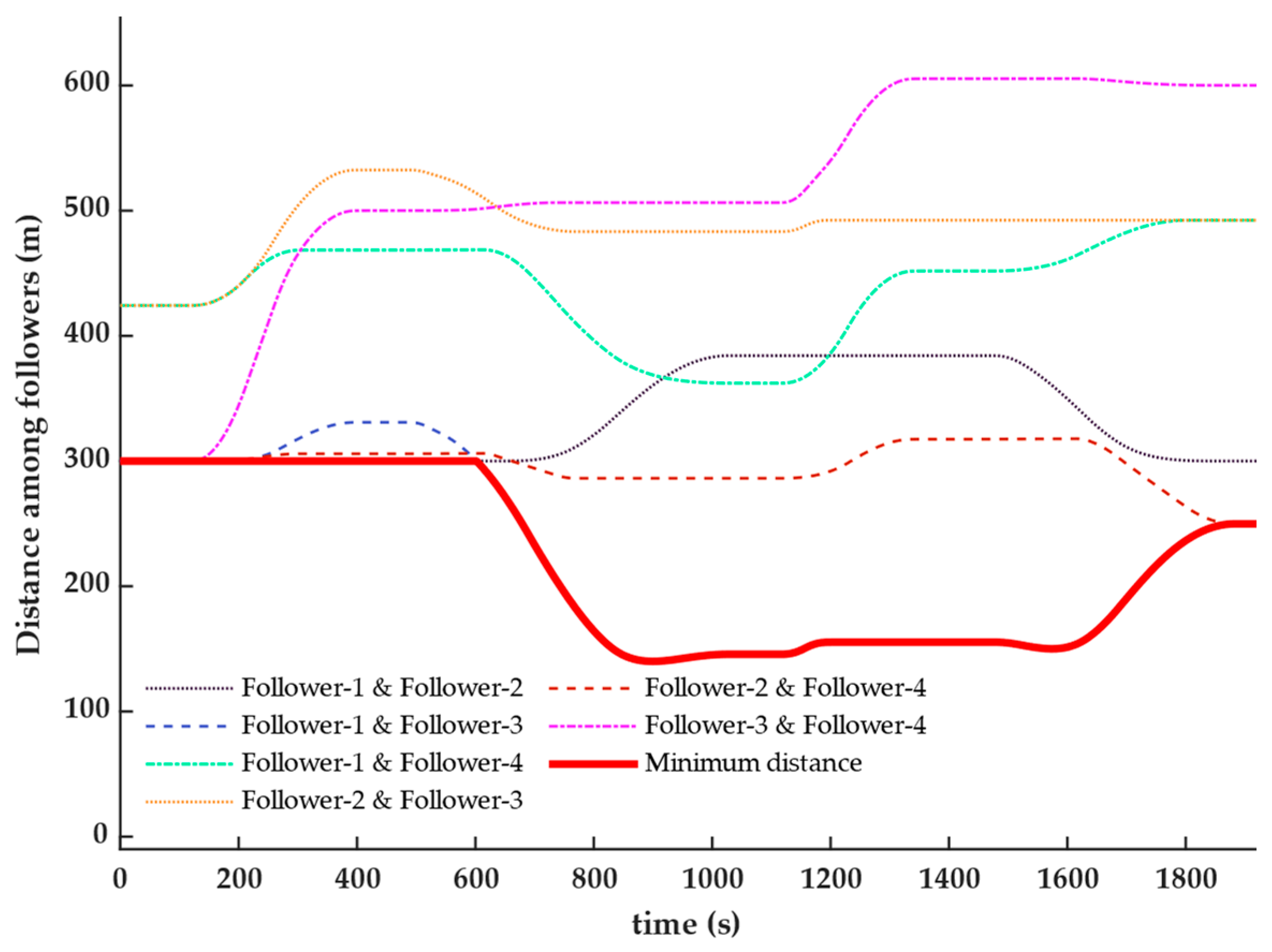

During the process of formation reconstruction, the distances between the leader UUV and the follower UUVs are depicted in

Figure 14, while the distances among the follower UUVs are shown in

Figure 15. The simulation results indicate that the distances between the individual UUVs within the multi-UUV system consistently remained within a safe range, with no risk of collision observed. Based on the data presented in

Figure 13,

Figure 14 and

Figure 15, it can be concluded that the proposed formation reconstruction method successfully achieves dynamic formation adjustments for multiple UUVs while preventing collisions.

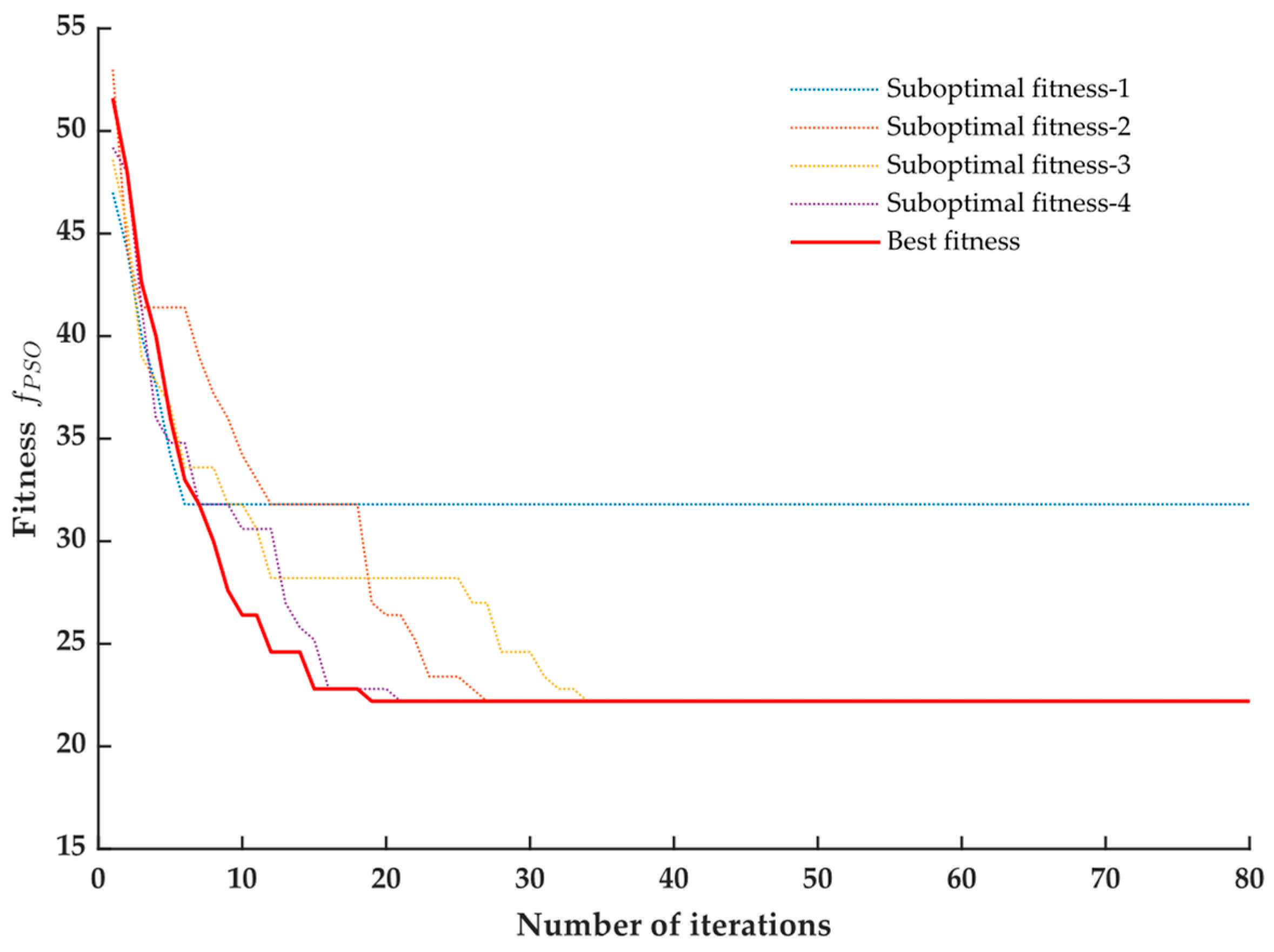

The convergence process of the fitness function in the PSO-based path planning method utilized in this study is illustrated in

Figure 16. It is demonstrated that the fitness value of the particle swarm reached its optimal value of 22.2 during the 19th optimization iteration, indicating that the optimal set of path points for formation reconstruction had been determined. These findings validate the effectiveness of the PSO-based path planning method proposed in this study.

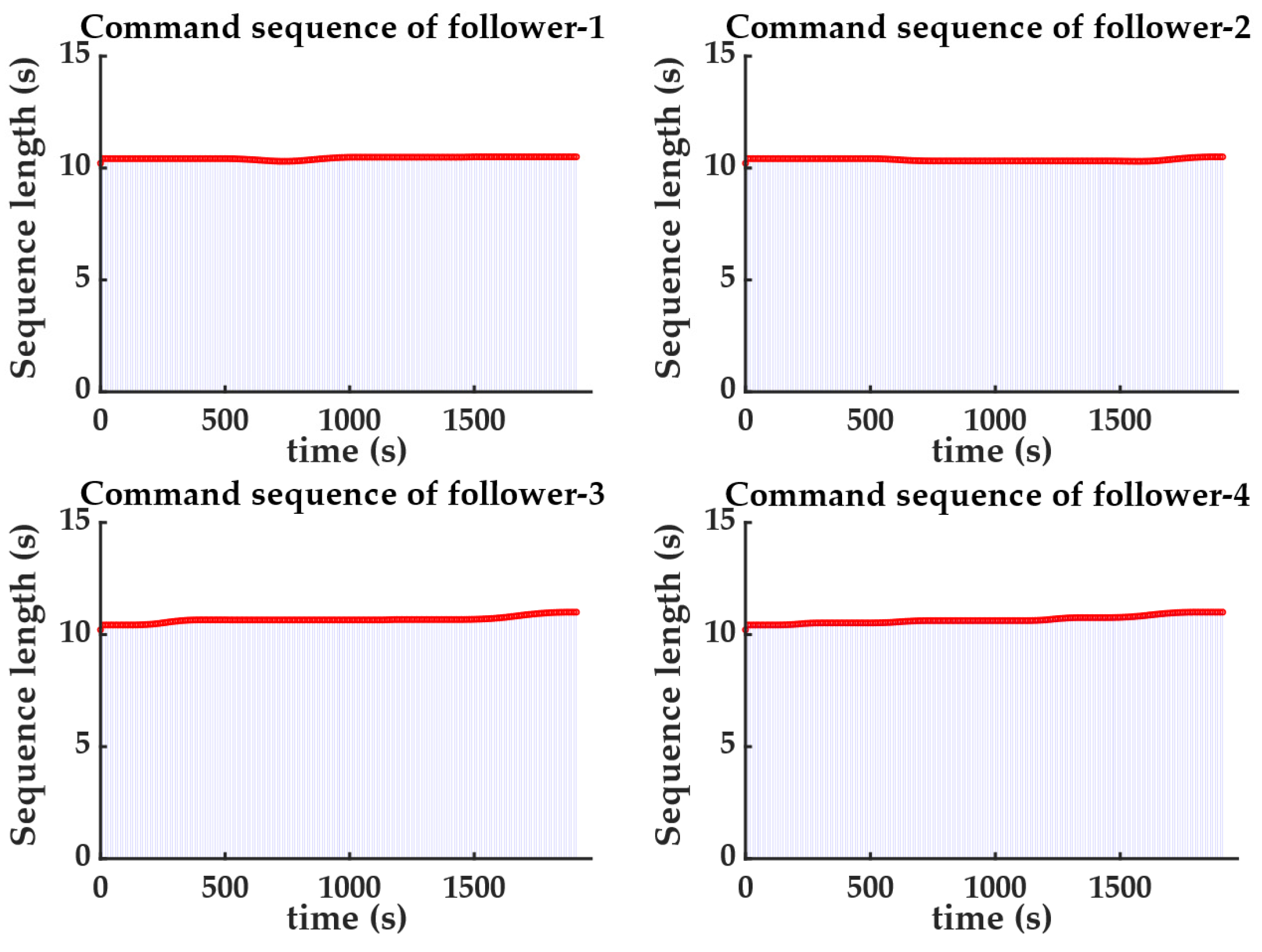

Figure 17 displays the length of the control command sequences received by each follower UUV from the leader UUV. The bar segments in the figure represent the time duration encompassed in the control command sequences received by the follower UUVs at regular intervals. The red line indicates the variation trend of a single control instruction sequence length during the experiment. It can be observed that the time duration of the control command sequences transmitted by the leader UUV varied due to the relative distances between the leader and the follower UUVs and the speeds of the follower UUVs. The simulation results indicate that, although control command sequences were sent at regular intervals, the lengths of the received sequences were sufficient to ensure the continuity of control commands without any loss.

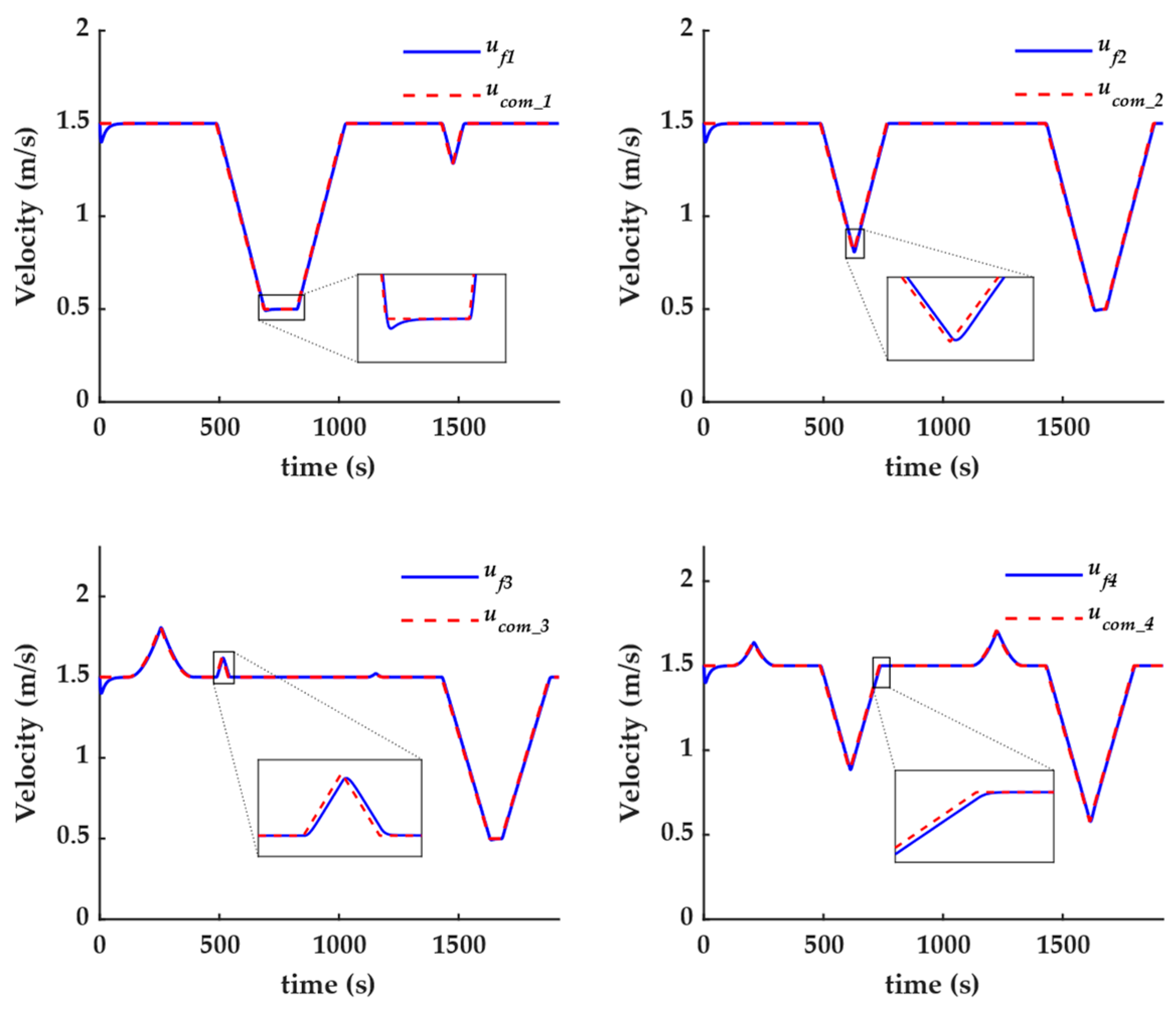

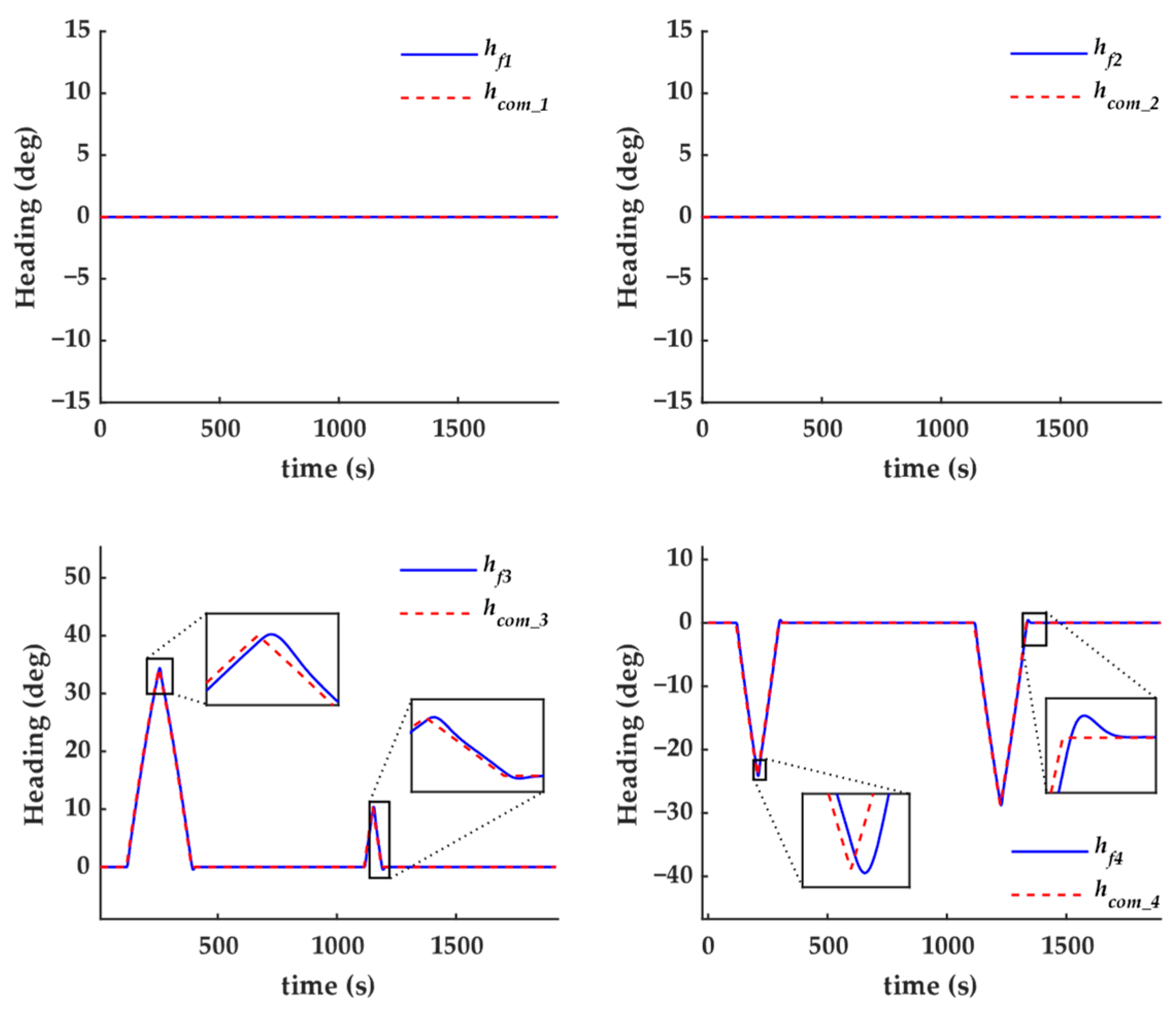

The changes in speed commands and actual speeds of the follower UUVs during the formation reconstruction process are presented in

Figure 18, while the changes in heading commands and actual headings are shown in

Figure 19. From

Figure 19, it can be observed that the heading control commands for followers 1 and 2 remained constant at 0°, indicating that these two UUVs performed linear motions only during the reconstruction process. This reflects the effectiveness of the proposed target position allocation method. Furthermore,

Figure 18 and

Figure 19 confirm that the speed and heading control commands received by the follower UUVs were continuous over time, with no loss of control commands observed. These results indirectly demonstrate the feasibility of the proposed delay compensation method.

7. Conclusions

Multi-UUV systems often require formation reconfiguration based on the specific tasks. However, achieving multi-UUV formation reconfiguration involves several challenges. First, when the formation is in motion, coordinating the control of the UUVs to reconfigure while following the overall movement of the formation presents a challenge. Second, designing a simple and effective method to prevent collisions among individual UUVs within the system is crucial. Lastly, under acoustic communication conditions, designing a feasible information exchange method that satisfies the formation reconfiguration requirements is also a critical issue. To address these challenges, a multi-UUV formation reconfiguration method based on PSO and fuzzy theory is proposed in this paper.

This study takes into account the characteristics of acoustic communication delays in marine environments and designs a formation reconfiguration method to address both the safety and speed of multi-UUV maneuvers. A two-dimensional spatial model of the horizontal plane is established using a grid-based method, and basic motion patterns for the follower UUVs within this model are designed. The PSO method is then used to plan the maneuvering target points and desired formation positions for each follower UUV, ensuring the safety of the UUVs during the formation reconfiguration process. Furthermore, a corresponding UUV control command transmission method is implemented, considering the issues associated with acoustic communication. Simulation results demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed method. The simulations indicate that the method can successfully achieve multi-UUV formation reconfiguration even under acoustic communication delays, with the leader UUV maintaining a constant speed.

This study focuses on two-dimensional multi-UUV formation reconfiguration due to project requirements. However, the study of formation reconfiguration in three-dimensional space is also of great importance and will be explored in future work. Additionally, the effects of model uncertainties and sea currents on system performance are important areas for future research. Future studies will address the effects of environmental disturbances and investigate formation reconfiguration in more complex marine conditions.