Numerical Investigation of Maneuvering Characteristics for a Submarine Under Horizontal Stern Plane Deflection in Vertical Plane Straight-Line Motion

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Governing Equations

2.2. Turbulence Model

3. Model Analysis and Verification

3.1. Submarine Model and Coordinate System

3.2. Computational Domain Dimension and Boundary Condition

3.3. Grid Generation and Arrangement

3.4. Validation and Verification of the Numerical Model

4. Analysis of the Influence of Steering Strategies on Vertical Plane Maneuvering Characteristics

4.1. Steering Strategies and Simulation Conditions

4.2. Motion Response Comparison and Analysis

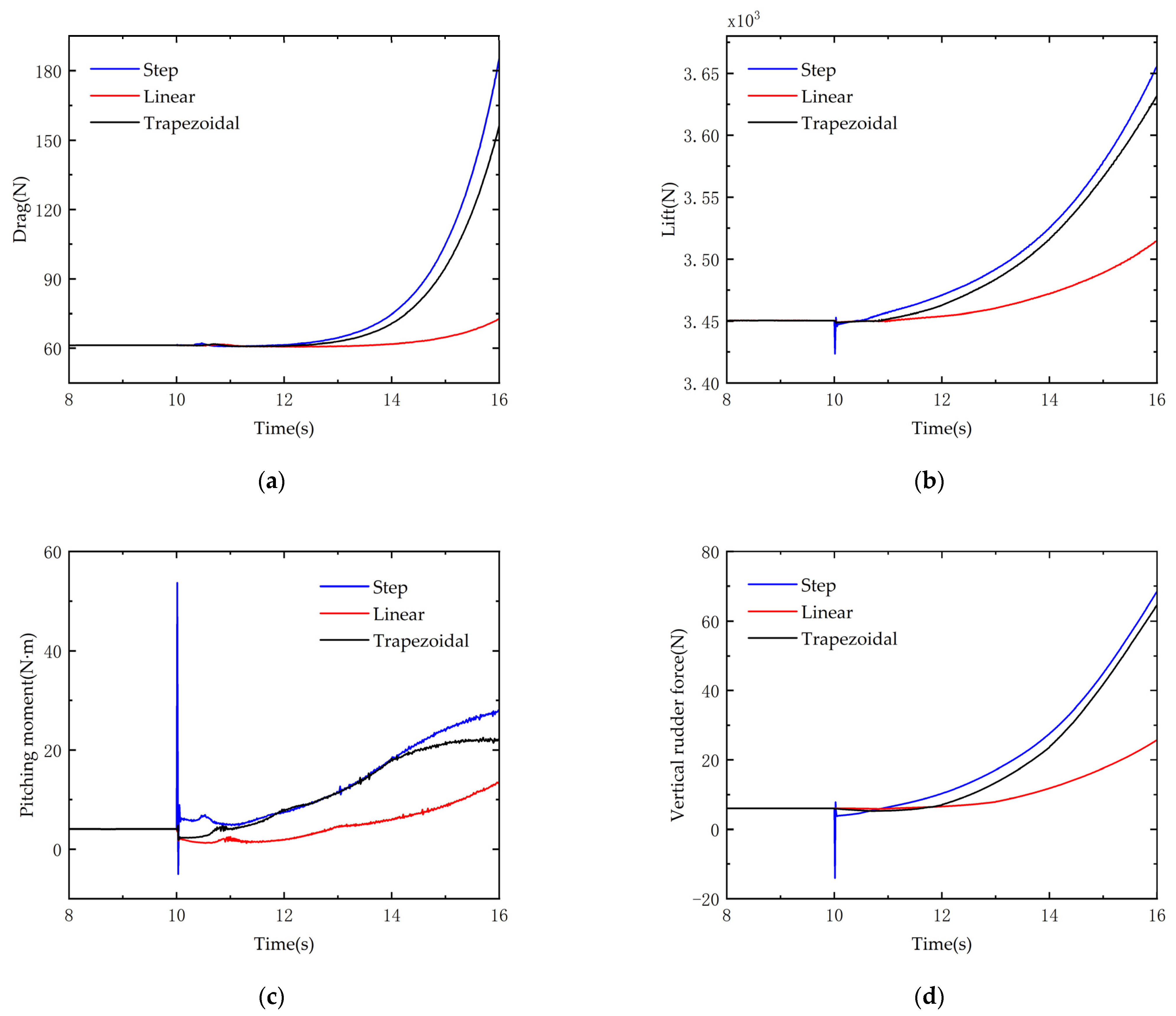

4.3. Hydrodynamic Characteristics Comparison and Analysis

4.4. Flow Field Analysis

4.4.1. Velocity Fields Around the Submarine

4.4.2. Velocity Fields Around the Rudder

4.4.3. Vortex Fields

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mahdaviniaki, M. Simulation of emergency hovering maneuvers in submarines. Mech. Based Des. Struct. Mach. 2022, 50, 3768–3780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutulo, S.; Guedes Soares, C. Mathematical models for simulation of manoeuvring performance of ships. Mar. Technol. Eng. 2011, 1, 661–698. [Google Scholar]

- Cardenas, P.; de Barros, E.A. Estimation of AUV hydrodynamic coefficients using analytical and system identification approaches. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2019, 45, 1157–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhushan, S.; Alam, M.; Walters, D.K. Evaluation of hybrid RANS/LES models for prediction of flow around surface combatant and Suboff geometries. Comput. Fluids 2013, 88, 834–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaver, W.E.; Morabito, M.G. Investigations of pitch instability of a wide-body submarine operating near the surface. Nav. Eng. J. 2018, 130, 105–117. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wang, X. Experimental and numerical study of rudder torque for BB2 generic submarine under steering conditions. Ocean Eng. 2025, 335, 121761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sener, M.Z.; Aksu, E. The numerical investigation of the rotation speed and Reynolds number variations of a NACA 0012 airfoil. Ocean Eng. 2022, 249, 110899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, X.; Zhang, S.; Li, C.; Liu, F. Maneuverability prediction of the wave glider considering ocean currents. Ocean Eng. 2023, 269, 113548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanvand, A.; Hajivand, A. Investigating the effect of rudder profile on 6DOF ship turning performance. Appl. Ocean Res. 2019, 92, 101918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, L.; Ye, J.; Liang, Q. Experimental Study on the Flow Field, Force, and Moment Measurements of Submarines with Different Stern Control Surfaces. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Huo, J.; Zhang, M.; Cai, X.; Wang, B.; Xie, Z. Maneuverability characteristics of a fouling submarine near the seabed. Ocean Eng. 2025, 315, 119773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Li, G.; Du, L. Investigation on the flow around a submarine under the rudder deflection condition by using URANS and DDES methods. Appl. Ocean Res. 2023, 131, 103448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Pan, Z.; Li, Y.; Song, C.; Zhang, M.; Ren, M. Investigation of the Asymmetric Features of X-Rudder Underwater Vehicle Vertical Maneuvring and Novel Motion Prediction Technology. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-H.; Kim, Y.; Baek, H.-M.; Choi, Y.-M.; Kim, Y.J.; Park, H.; Yoon, H.K.; Shin, J.-H.; Lee, J.; Chae, E.J. Experimental study of the hydrodynamic maneuvering coefficients for a BB2 generic submarine using the planar motion mechanism. Ocean Eng. 2023, 271, 113428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-H.; Kim, J.; Baek, H.-M.; Choi, Y.-M.; Shin, J.-H.; Lee, J.; Shin, S.-c.; Shin, Y.-h.; Chae, E.J.; Kim, E.S. Experimental investigation on a generic submarine hydrodynamic model considering the interaction effects of hull motion states and control planes. Ocean Eng. 2024, 298, 116878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, S.; Shin, J.; Yoon, J.; Ahn, J.; Kim, M. Experiment and modeling of submarine emergency rising motion using free-running model. Int. J. Nav. Archit. Ocean Eng. 2025, 17, 100641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugeai, A.; Vuillemin, P. Highly flexible aircraft flight dynamics simulation using CFD. In Proceedings of the IFASD 2024, The Hague, The Netherlands, 17–21 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hiremath, S.; Malipatil, A.S. CFD simulations of aircraft body with different angle of attack and velocity. Int. J. Innov. Res. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2014, 3, 16965–16972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Song, S.; Tezdogan, T. Free running CFD simulations to investigate ship manoeuvrability in waves. Ocean Eng. 2021, 236, 109567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, K.; Yu, J.; Liu, L.; Zhang, D.; Wang, X. An investigation into the effects of damaged compartment on turning maneuvers using the free-running CFD method. Ocean Eng. 2023, 271, 113718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zou, L.; Wan, D. CFD simulations of free running ship under course keeping control. Ocean Eng. 2017, 141, 450–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Shang, Y.; Zhang, L. Turning and zigzag maneuverability investigations on a waterjet-propelled trimaran in calm and wavy water using a direct CFD approach. Ocean Eng. 2023, 286, 115511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.-T.; Kim, S.; Paik, K.-J.; Yang, J.-K.; Kwon, S.-Y. Free-running CFD simulations to assess a ship-manoeuvring control method with motion forecast in waves. Ocean Eng. 2023, 271, 113806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferziger, J.H.; Perić, M.; Street, R.L. Computational Methods for Fluid Dynamics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, W.P.; Launder, B.E. The prediction of laminarization with a two-equation model of turbulence. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 1972, 15, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Launder, B.E.; Sharma, B.I. Application of the energy-dissipation model of turbulence to the calculation of flow near a spinning disc. Lett. Heat Mass Transf. 1974, 1, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Lakshmanan, B. Application of a Reynolds stress turbulence model to the compressible shear layer. AIAA J. 1991, 29, 743–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, N.C.; Huang, T.T.; Chang, M.S. Geometric Characteristics of DARPA SUBOFF Models (DTRC Model Nos. 5470 and 5471); David Taylor Research Center: Bethesda, MD, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, K.; Sahoo, P. Numerical study on self-propulsive performance of the DARPA SUBOFF submarine including uncertainty analysis. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Ships and Offshore Structures, Melbourne, FL, USA, 4–8 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Abbreviation | Definitions. |

|---|---|

| RANS | Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes |

| PMM | Planar Motion Mechanism |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| URANS | Unsteady Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes |

| DDES | Delayed Detached Eddy Simulation |

| FMI | Functional Mock-up Interface |

| FMU | Functional Mock-up Unit |

| RST | Reynolds Stress Transport |

| Terns | Values | Units |

|---|---|---|

| Total body length | 4.356 | m |

| Maximum body diameter | 0.508 | m |

| Total sail length | 0.368 | m |

| Total sail height | 0.205 | m |

| Volume | 0.706 | m3 |

| Wetted surface | 6.35 | m2 |

| Inflow velocity | 3.3436 | m/s |

| Rudder | NACA0020 | / |

| Scale ratio | 24 | / |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zou, B.; Zan, Y.; Guo, R.; Wang, S.; Jin, Z.; Xu, Q. Numerical Investigation of Maneuvering Characteristics for a Submarine Under Horizontal Stern Plane Deflection in Vertical Plane Straight-Line Motion. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2371. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122371

Zou B, Zan Y, Guo R, Wang S, Jin Z, Xu Q. Numerical Investigation of Maneuvering Characteristics for a Submarine Under Horizontal Stern Plane Deflection in Vertical Plane Straight-Line Motion. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(12):2371. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122371

Chicago/Turabian StyleZou, Binbin, Yingfei Zan, Ruinan Guo, Shuaihang Wang, Zhenzhong Jin, and Qiang Xu. 2025. "Numerical Investigation of Maneuvering Characteristics for a Submarine Under Horizontal Stern Plane Deflection in Vertical Plane Straight-Line Motion" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 12: 2371. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122371

APA StyleZou, B., Zan, Y., Guo, R., Wang, S., Jin, Z., & Xu, Q. (2025). Numerical Investigation of Maneuvering Characteristics for a Submarine Under Horizontal Stern Plane Deflection in Vertical Plane Straight-Line Motion. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(12), 2371. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122371