Ship Manoeuvring Research 2010–2025: From Hydrodynamics and Control to Digital Twins, AI and MASS

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

- Hydrodynamic and Maneuvering Modeling Group (MMG)-type modelling;

- CFD-based and numerical simulation of manoeuvres;

- System identification and parameter estimation;

- Guidance, control, and collision avoidance;

- Data-driven and AI-based prediction models;

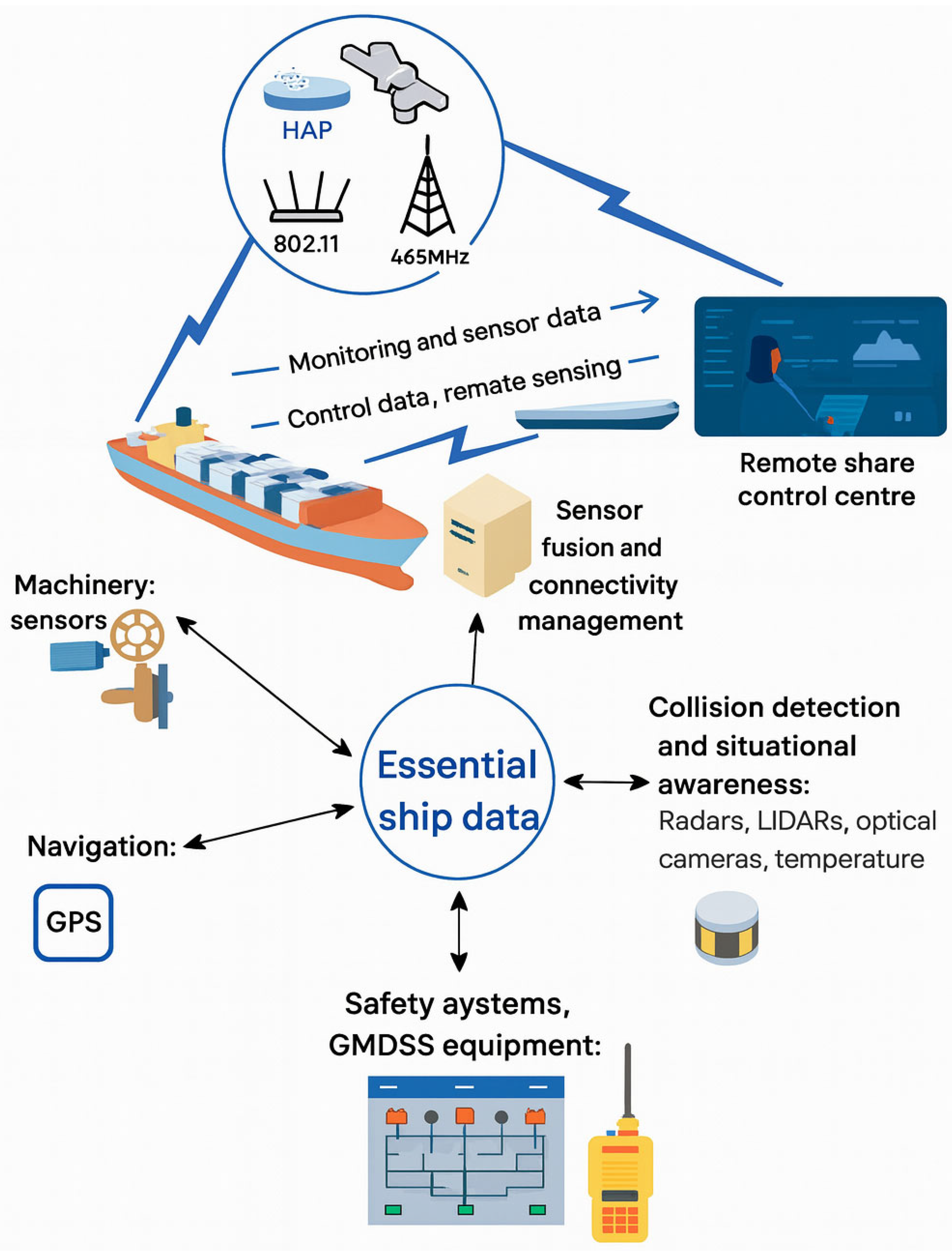

- Sensing, perception, and trajectory tracking;

- Environmental and operational effects; and

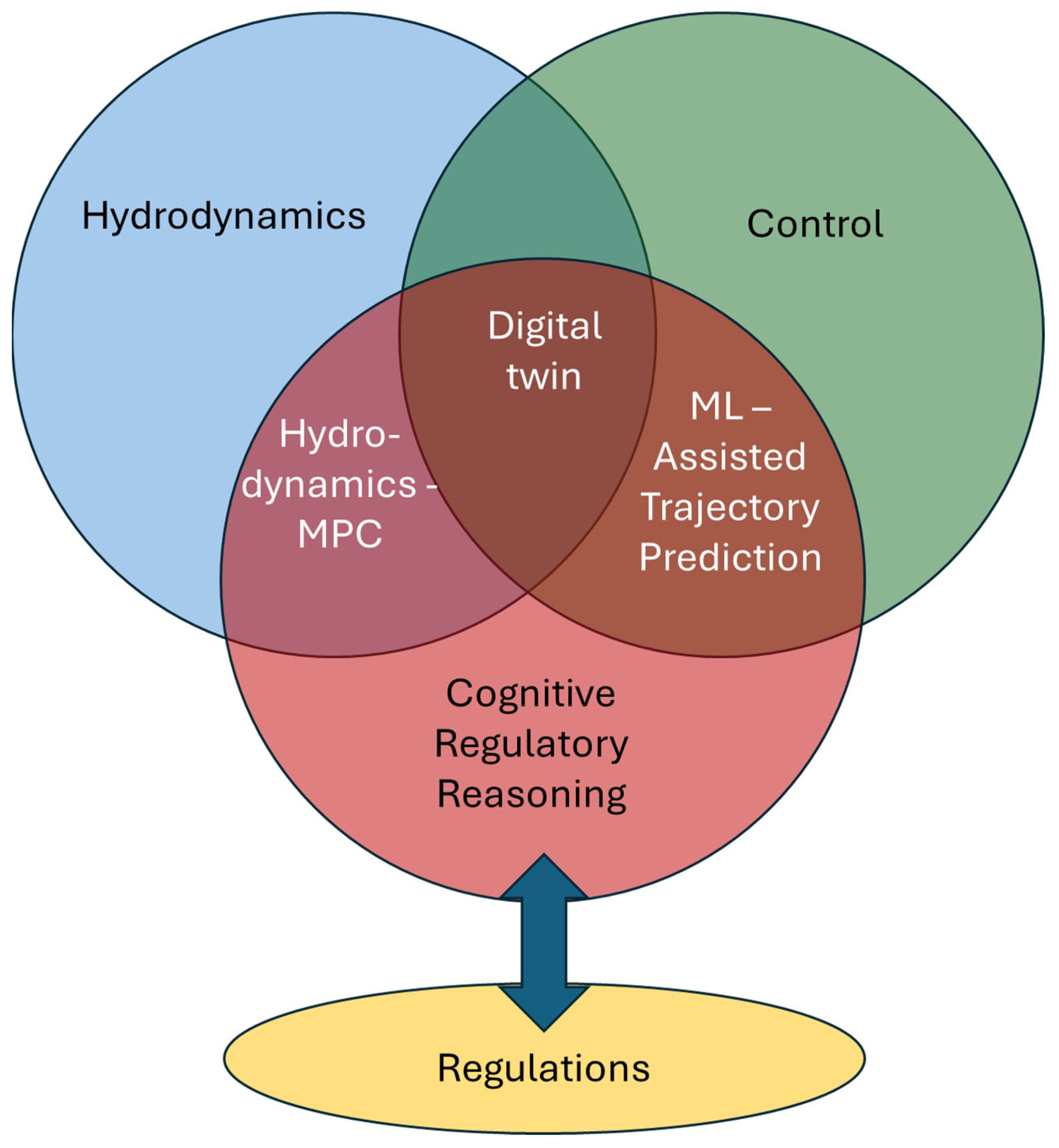

- Emerging digital-twin frameworks for manoeuvring and autonomous navigation.

- How has ship manoeuvring research evolved from classical hydrodynamic models to integrated frameworks that combine physics-based modelling, advanced control, AI prediction, and digital-twin concepts between 2010 and 2025?

- To what extent do these different methodological strands—hydrodynamics, control, AI, and sensing—interact in practice, and where are the gaps that currently prevent fully integrated manoeuvring systems for MASS?

- What evidence exists regarding the effectiveness of these approaches (e.g., in terms of prediction accuracy, collision-risk reduction, controllability in complex environments, or environmental performance), and how can this evidence inform the design of next-generation manoeuvring and autonomy frameworks?

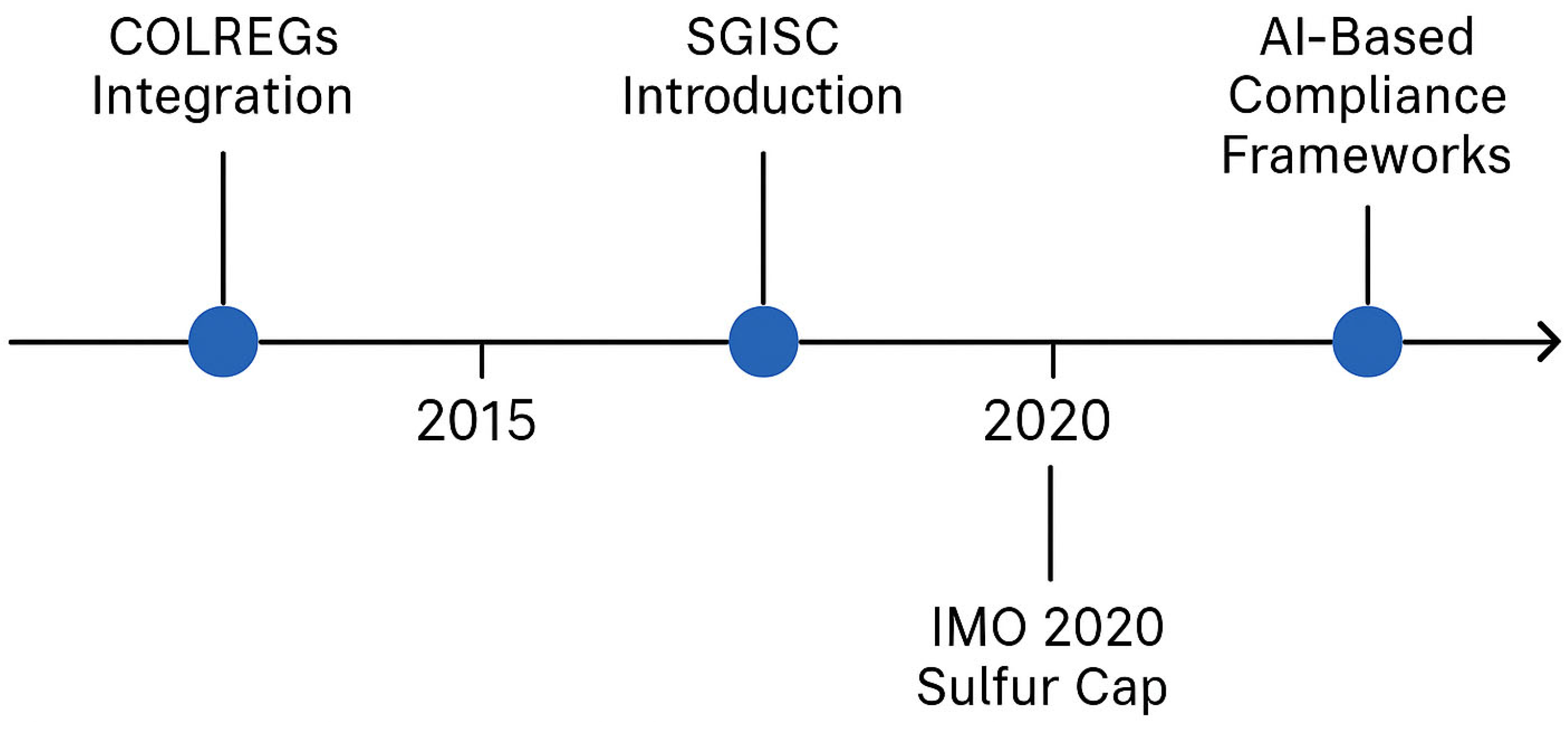

3. Regulatory Compliance and Intelligent Manoeuvring Standards

3.1. From Empirical Stability to Physics-Based Regulation

3.2. Second-Generation Intact Stability Criteria (SGISC): Physics-Based Regulation

3.3. From Rule Encoding to Cognitive Compliance in Manoeuvring

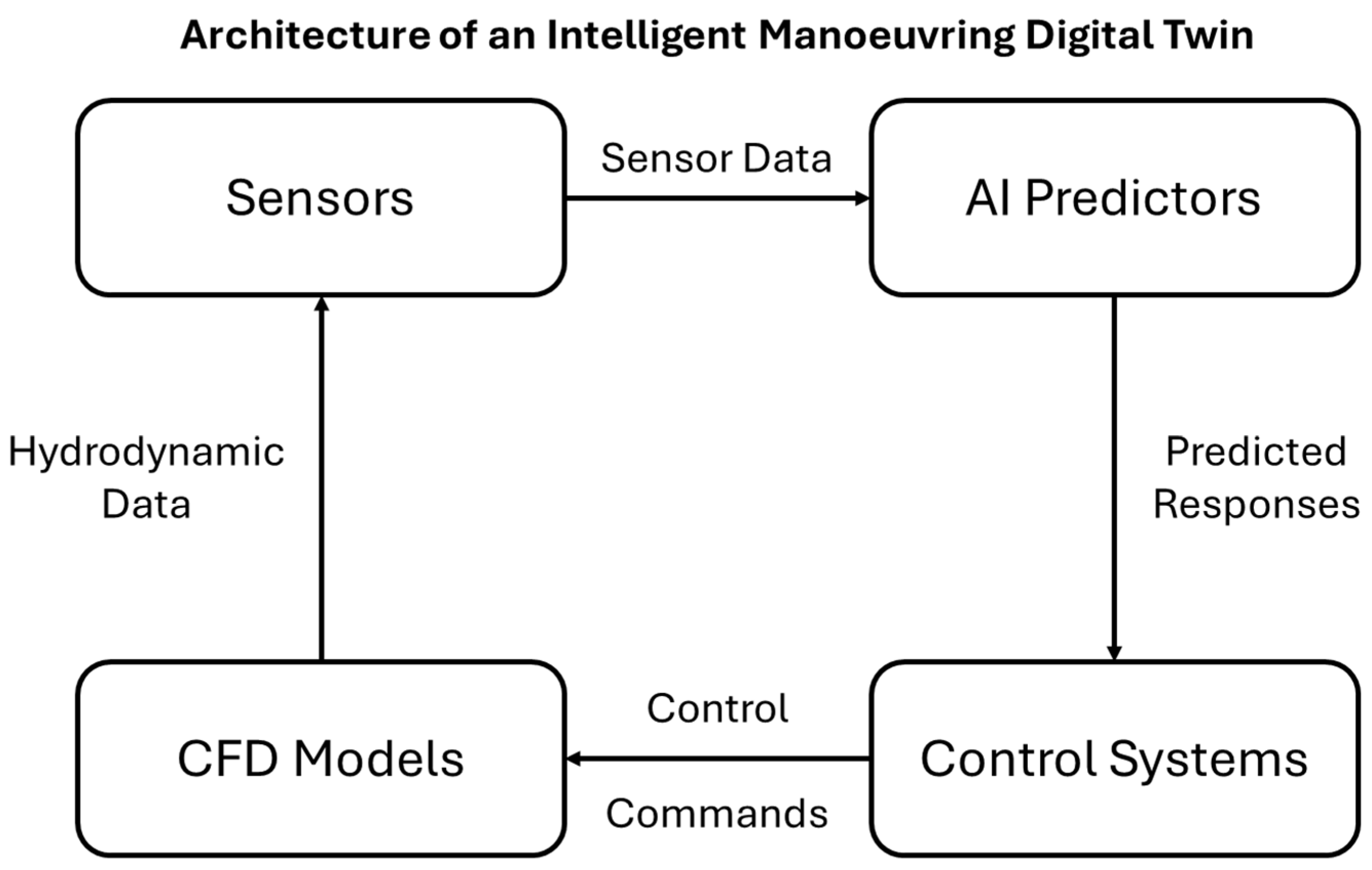

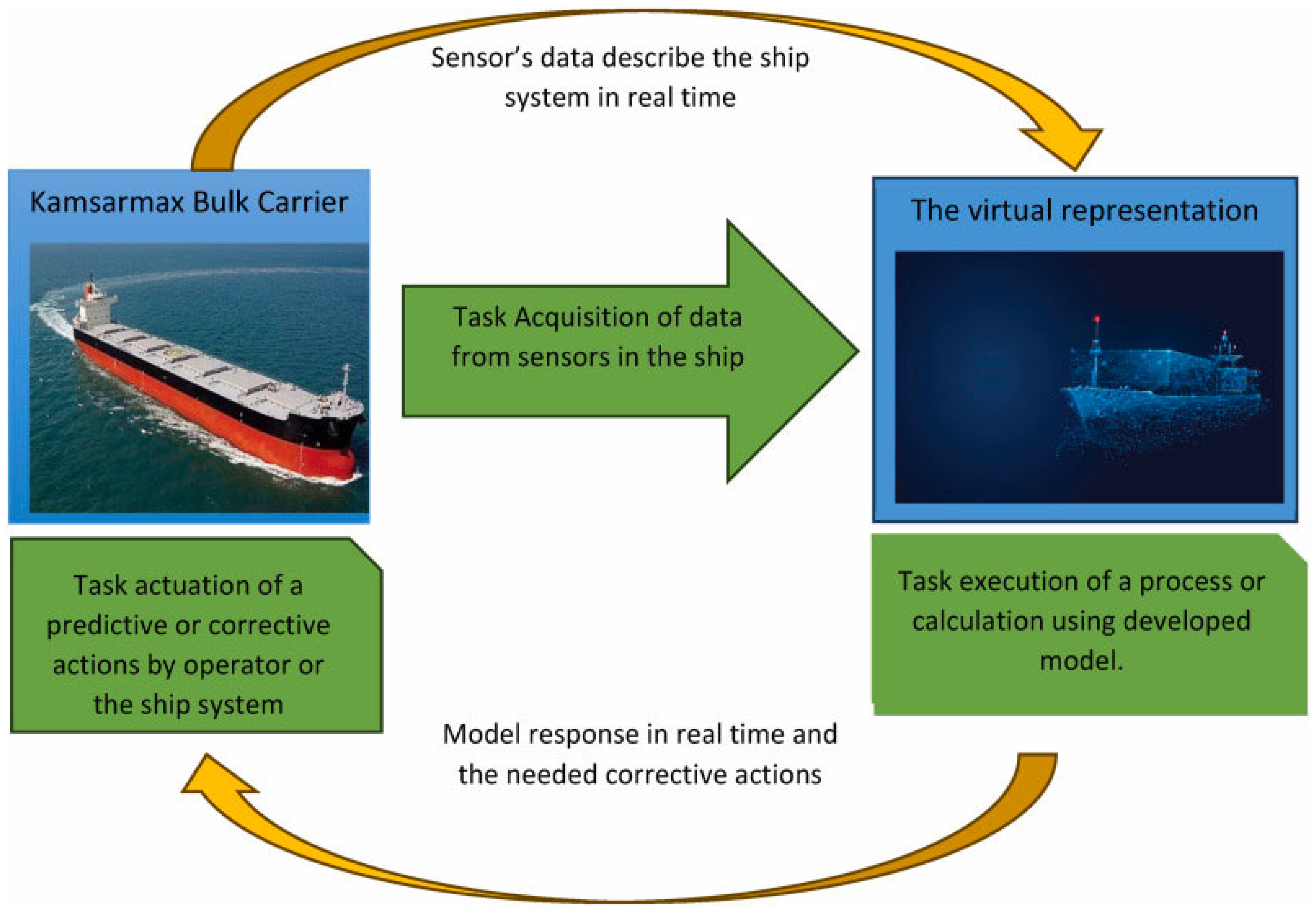

4. Machine Learning and Digital Twins in Ship Manoeuvring

5. Manoeuvring-Coefficient Estimation and Adaptive Control Frameworks

5.1. Manoeuvring-Coefficient Estimation

5.2. Adaptive and Intelligent Control

6. Hydrodynamic Foundations to Intelligent Adaptive Control

7. Machine Learning for Collision Avoidance and Control

8. Manoeuvring for Sustainable Emissions Reduction

9. Cooperative Navigation and Formation Control in the Era of Intelligent Autonomy

10. Evolution of Simulation Software Toward Intelligent Maritime Ecosystems

| Period | Representative Studies | Software/Approach Used | Contribution/Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2010–2014 (Foundations) | [79,81,131,137,177,238] | CFD solvers (RANS-based), VORTFIND algorithm (computational algorithm used in fluid dynamics to identify vortex core centres within a velocity field), adaptive system identification, simulation-based control frameworks | Established simulation as a complement to experiments; CFD validated turning circles with ~10% deviation; introduced appendage modelling and real-time hydrodynamic parameter estimation. Introduced vortex core identification methods (VORTFIND) enabling detailed flow-structure analysis around hull, rudder, and appendages. |

| 2015–2020 (Consolidation) | [30,51,130,158,159,162,197,239,240,241,242] | Hybrid CFD/virtual captive tests; viscous–inviscid coupling; semi-physical nonlinear models; real-time vessel mathematical models; URANS/LES hybrid turbulence modelling; high-fidelity geometric and visual modelling for ship-bridge simulators; multiphase CFD for bubble-size distribution; CFD–CSD | Reduced reliance on physical experiments; improved accuracy of vortex predictions (less than 7% error); expanded realism of simulation through hybrid methods and coupling approaches; improved training realism and behavioural validity, resolved unsteady hydrodynamic and structural loading; quantified dispersed-phase hydrodynamics; unsteady manoeuvring forces. |

| 2021–2024 (Transition) | [91,102,107,114,189] | Real-time system identification with wave effects; ensemble learning frameworks; dynamic nonparametric simulation; predictive full-scale platforms | Linked manoeuvring with predictive autonomy; ensemble methods reduced trajectory errors by 15–20%; real-time simulations captured hybrid propulsion and wave-induced dynamics. |

| 2025 (Breakthrough) | [24,28,33,34,37,115,166,175] | Digital-twin frameworks (transformer-based, LSTM, Koopman operator learning); online adaptive DOF models; simulation–decision-support integration (COLREG compliance, fuel economy, emission inventories) | Digital twins reduced trajectory mean absolute error (MAE) by 30–40%; adaptive software recalibrated in real time; integrated manoeuvring into MASS, collision avoidance, emission monitoring, and underwater vehicle mission planning. |

11. Discussion and Future Trends

- (1)

- Hydrodynamic modelling and coefficient estimation;

- (2)

- Real-time control and stability in nonlinear conditions;

- (3)

- Regulatory-compliant behaviour and COLREGs interpretability;

- (4)

- Prediction and perception for collision avoidance; and

- (5)

- Integration of manoeuvring with environmental performance and energy efficiency.

11.1. Regulatory Intelligence and Cognitive Compliance

11.2. Digital Twins and Data-Centric Autonomy

11.3. Manoeuvring Coefficients and Adaptive Control

11.4. From Hydrodynamics to Intelligent Manoeuvring

11.5. Safety, Trust, and Human–AI Teaming

11.6. Environmental Intelligence and Sustainable Optimisation

- AI-driven route and speed optimisation in constrained waters;

- Real-time emission forecasting incorporating alternative fuels;

- Environmental twins linking manoeuvring behaviour with port air-quality dynamics.

- Operational guidance to improve CII ratings and well-to-wake sustainability.

11.7. Cooperative Navigation and Multi-Agent Learning

- Intent prediction using AI-Theory-of-Mind frameworks;

- Cooperative perception from networked sensors (AIS, radar, SAR/ISAR);

- Multi-vessel negotiation protocols for head-on, crossing, and overtaking encounters;

- Robust communication strategies tolerant to latency, packet loss, and bandwidth constraints.

11.8. Simulation Software and Intelligent Maritime Ecosystems

11.9. Solved, Partially Solved, and Unsolved Problems

- Identification of hydrodynamic coefficients for conventional hulls (PMM and CFD-based VCT);

- Classical path-following for open-water conditions;

- Local collision avoidance in simple, two-ship encounters;

- Nonlinear manoeuvring models in calm water.

- Manoeuvring prediction under waves, shallow water, and interaction effects;

- COLREGs-compliant control in realistic multi-vessel traffic;

- Behaviour prediction using ML with quantified uncertainty;

- Online adaptation of coefficients under fouling or loading changes;

- Hybrid propulsion–manoeuvring integration.

- Multi-agent cooperative navigation with guaranteed safety;

- Cognitive COLREGs reasoning equivalent to human seamanship;

- Real-time SGISC integration into autonomous control loops;

- Explainable AI manoeuvring capable of certification and auditing;

- Digital-twin verification under sparse, noisy, or adversarial data;

- Coupled hydrodynamic–energy–emission optimisation during manoeuvring;

- Resilience to sensor spoofing, Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) degradation, or cyber interference.

11.10. Limitations, Risks, and Failure Modes in AI-Driven Manoeuvring and Digital Twins

- AIS data quality and reliability constraints

- 2.

- Domain shift and poor generalisation of learning models

- 3.

- Opacity and verification challenges in deep learning and RL

- 4.

- Instability risks in online and adaptive control

- 5.

- Digital-twin uncertainty and divergence

- 6.

- Collision-avoidance failure modes in RL and MPC

- 7.

- Certification, regulation, and safety governance barriers

- 8.

- Reproducibility and methodological inconsistency

11.11. Toward a Convergent Maritime Intelligence

12. Conclusions and Future Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| AIS | Automatic Identification System |

| ANFIS | Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| BiLSTM | Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory |

| CFD | Computational fluid dynamics |

| CII | Carbon Intensity Indicator |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide |

| COLREGs | International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea |

| CPA | Closest Point of Approach |

| CPI | Collision probability indicator |

| DES | Detached-eddy simulation |

| DOF | Degree of freedom |

| DRL | Deep reinforcement learning |

| DSA | Direct Stability Assessment |

| DT | Digital twin |

| DVS | Dynamic visual sensing |

| DVS | Dynamic virtual ship |

| EEDI | Energy Efficiency Design Index |

| EEXI | Energy Efficiency Existing Ship Index |

| EFs | Emission Factors |

| ESN | Echo State Network |

| FGISC | First-Generation Intact Stability Criteria |

| GHG | Greenhouse gas |

| GIS | Geographic information systems |

| GM | Metacentric height |

| GMM | Gaussian Mixture Model |

| GMR | Gaussian Mixture Regression |

| GNSS | Global Navigation Satellite System |

| GRU | Gated Recurrent Unit |

| GWO | Grey Wolf Optimiser |

| GZ | Righting-arm curves |

| H∞ | H-infinity |

| HAT | Human–AI Teaming |

| HCAI | Human-Centred AI |

| HPMM | Horizontal Planar Motion Mechanism |

| IMO | International Maritime Organization |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| ISAR | Inverse Synthetic Aperture Radar |

| KELM | Kernel Extreme Learning Machine |

| LES | Large-Eddy Simulation |

| LQG | Linear–Quadratic–Gaussian |

| LS-SVM | Least-squares support vector machine |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| LWL | Locally Weighted Learning |

| MAE | Mean absolute error |

| MASS | Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships |

| ML | Machine learning |

| MMG | Maneuvering Modeling Group |

| MPC | Model predictive control |

| NBeatsX | Neural basis expansion analysis with exogenous variables |

| NOx | Nitrogen oxides |

| OG | Operational Guidance |

| OL | Operational Limitations |

| ONR | Office of Naval Research |

| PID | Proportional–integral–derivative |

| PM | Particulate matter |

| PMM | Planar Motion Mechanism |

| PPO | Proximal Policy Optimisation |

| PSO | Particle Swarm Optimisation |

| RANS | Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes |

| RBF | Radial Basis Function |

| RLS | Recursive least squares |

| ROM | Reduced-Order Model |

| RVM | Relevance vector machine |

| SAR | Synthetic Aperture Radar |

| SDC | Ship Design and Construction |

| SGISC | Second-Generation Intact Stability Criteria |

| SI | System Identification |

| SOx | Sulphur oxides |

| SVM | Support vector machine |

| TCPA | Time to Closest Point of Approach |

| ToM | Theory-of-Mind |

| URANS | Unsteady Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes |

| USV | Unmanned Surface Vessel |

| VCT | Virtual Captive Tests |

| VORTFIND | Computational algorithm used in fluid dynamics to identify vortex core centres within a velocity field |

References

- Bouman, E.A.; Lindstad, E.; Rialland, A.I.; Strømman, A.H. State-of-the-art technologies, measures, and potential for reducing GHG emissions from shipping—A review. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2017, 52, 408–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadros, M.; Ventura, M.; Guedes Soares, C. Review of the IMO Initiatives for Ship Energy Efficiency and Their Implications. J. Mar. Sci. Appl. 2023, 22, 662–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMO. IMO’s Work to Cut GHG Emissions from Ships. Available online: https://www.imo.org/en/mediacentre/hottopics/pages/cutting-ghg-emissions.aspx (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Čerka, J.; Mickevičienė, R.; Ašmontas, Ž.; Norkevičius, L.; Žapnickas, T.; Djačkov, V.; Zhou, P. Optimization of the research vessel hull form by using numerical simulaton. Ocean Eng. 2017, 139, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadros, M.; Ventura, M.; Guedes Soares, C. Review of the Decision Support Methods Used in Optimizing Ship Hulls towards Improving Energy Efficiency. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadros, M.; Shi, W.; Xu, Y.; Song, Y. A unified cross-series marine propeller design method based on machine learning. Ocean Eng. 2024, 314, 119691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadros, M.; Boulougouris, E. Performance Assessment of B-Series Marine Propellers with Cupping and Face Camber Ratio Using Machine Learning Techniques. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadros, M.; Ventura, M.; Guedes Soares, C. Optimization procedure to minimize fuel consumption of a four-stroke marine turbocharged diesel engine. Energy 2019, 168, 897–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivyza, N.L.; Rentizelas, A.; Theotokatos, G.; Boulougouris, E. Decision support methods for sustainable ship energy systems: A state-of-the-art review. Energy 2022, 239, 122288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadros, M.; Boulougouris, E.; Ypsilantis, A.M.; Hadjioannou, N.; Sakellis, V. Alternative Fuels’ Techno-Economic and Environmental Impacts on Ship Energy Efficiency with Shaft Generator Integration. Energies 2025, 18, 6070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadros, M.; Karatuğ, Ç.; Shi, W. A data-driven decision support system for ship energy efficiency using MIMO artificial neural networks. J. Mar. Eng. Technol. 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, J.J.; Dash, A.K.; Nagarajan, V.; Sha, O.P. On the hydrodynamic loading of marine cycloidal propeller during maneuvering. Appl. Ocean Res. 2019, 86, 87–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huyer, S.A.; Dropkin, A.; Beal, D.N.; Farnsworth, J.A.N.; Amitay, M. Preswirl maneuvering propulsor. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2012, 37, 122–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadros, M.; Ventura, M.; Guedes Soares, C. Review of current regulations, available technologies, and future trends in the green shipping industry. Ocean Eng. 2023, 280, 114670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benvenuto, G.; Campora, U. Dynamic simulation of a high-performance sequentially turbocharged marine diesel engine. Int. J. Engine Res. 2002, 3, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figari, M.; Altosole, M. Dynamic behaviour and stability of marine propulsion systems. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part M J. Eng. Marit. Environ. 2007, 221, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martelli, M.; Figari, M.; Altosole, M.; Vignolo, S. Controllable pitch propeller actuating mechanism, modelling and simulation. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part M J. Eng. Marit. Environ. 2014, 228, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, L.; Guedes Soares, C. Dynamic model of manoeuvrability using recursive neural networks. Ocean Eng. 2003, 30, 1669–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vettor, R.; Guedes Soares, C. Development of a ship weather routing system. Ocean Eng. 2016, 123, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aung, M.Z.; Umeda, N. Manoeuvring simulations in adverse weather conditions with the effects of propeller and rudder emergence taken into account. Ocean Eng. 2020, 197, 106857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aung, M.Z.; Umeda, N. Investigation into control strategies for manoeuvring in adverse weather conditions. Ocean Eng. 2020, 218, 108170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taskar, B.; Andersen, P. Comparison of added resistance methods using digital twin and full-scale data. Ocean Eng. 2021, 229, 108710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gucma, S.; Zalewski, P. Optimization of fairway design parameters: Systematic approach to manoeuvring safety. Int. J. Nav. Archit. Ocean Eng. 2020, 12, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinaci, O.K. Ship digital twin architecture for optimizing sailing automation. Ocean Eng. 2023, 275, 114128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Øvergård, K.I.; Bjørkli, C.A.; Røed, B.K.; Hoff, T. Control strategies used by experienced marine navigators: Observation of verbal conversations during navigation training. Cogn. Technol. Work 2010, 12, 163–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revestido, E.; Velasco, F.J. Two-step identification of non-linear manoeuvring models of marine vessels. Ocean Eng. 2012, 53, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossen, T.I. Handbook of Marine Craft Hydrodynamics and Motion Control; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sajjad, M.; Van, T.; Shahariar, G.M.H.; Suara, K.A.; Surawski, N.; Bodisco, T.A.; Ristovski, Z.D.; Brown, R.J.; Zare, A. Ship emissions and fuel economy under transient conditions: Revisiting the propeller law. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2025, 221, 118535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winnes, H.; Fridell, E. Emissions of NOx and particles from manoeuvring ships. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2010, 15, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajivand, A.; Mousavizadegan, S.H. Virtual simulation of maneuvering captive tests for a surface vessel. Int. J. Nav. Archit. Ocean Eng. 2015, 7, 848–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ITTC. The manoeuvring committee: Final Report and Recommendations to the 28th ITTC. In Proceedings of the 28th ITTC, Wuxi, China, 22 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- ITTC. Report of the Manoeuvring Committee. In Proceedings of the 30th ITTC, Tasmania, Australia, 22–27 September 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Shehata, A.; Zhang, M.; Tsoulakos, N.; Kujala, P. A Transformer based task execution digital twin of 3-DOF maneuvering of Bulk Carrier for autonomous maritime systems. Ocean Eng. 2025, 341, 122797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, K.Y.; Fang, C.C. Analysis of real-time ship manoeuvring simulation with a ship collision avoidance E-navigation aid system. Int. J. Nav. Archit. Ocean Eng. 2025, 17, 100669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisowski, J. Computational intelligence in marine control engineering education. Pol. Marit. Res. 2021, 28, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gralak, R. A method of navigational information display using augmented virtuality. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhang, K. Research on Collision Avoidance Decision-Making of Stand-On Ships Based on the Improved Velocity Obstacle Algorithm. ASCE-ASME J. Risk Uncertain. Eng. Syst. Part A Civ. Eng. 2025, 11, 04025074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalewski, P.; Bilewski, M. GNSS Measurements Model in Ship Handling Simulators. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 76428–76437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, C.-H.; Huang, P.-H.; Yamamura, S.; Chen, C.-Y. Design optimal control of ship maneuver patterns for collision avoidance: A review. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 2012, 20, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Hekkenberg, R.; Rotteveel, E.; Hopman, H. Literature review on evaluation and prediction methods of inland vessel manoeuvrability. Ocean Eng. 2015, 106, 458–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Guedes Soares, C. Review of System Identification for Manoeuvring Modelling of Marine Surface Ships. J. Mar. Sci. Appl. 2025, 24, 459–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wu, Q.; Liu, J.; He, Y.; Li, S. State-of-the-Art Review and Future Perspectives on Maneuvering Modeling for Automatic Ship Berthing. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maljković, M.; Pavić, I.; Meštrović, T.; Perkovič, M. Ship Maneuvering in Shallow and Narrow Waters: Predictive Methods and Model Development Review. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMarco Muscat-Fenech, C.; Sant, T.; Zheku, V.V.; Villa, D.; Martelli, M. A Review of Ship-to-Ship Interactions in Calm Waters. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamis, A.S.; Ahmad Fuad, A.F.A.; Anwar, A.Q.; Monir Hossain, M. A systematic scoping review on ship accidents due to off-track manoeuvring: A systematic scoping review on ship accidents due to off-track manoeuvring. WMU J. Marit. Aff. 2022, 21, 453–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalba Méndez, G.; Gemechu, E.D. Estimating GHG emissions of marine ports-the case of Barcelona. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 1363–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.H. The seabots are coming here: Should they be treated as vessels? J. Navig. 2012, 65, 749–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahveci, N.E.; Ioannou, P.A. Adaptive steering control for uncertain ship dynamics and stability analysis. Automatica 2013, 49, 685–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgarioto, D.; Madden, C. Full-scale manoeuvring trials for the Wayamba unmanned underwater vehicle. Underw. Technol. 2014, 32, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.Y.; Li, W.; Halse, K.H.; Hildre, H.P.; Zhang, H.X. Hierarchical control of marine vehicles for autonomous manoeuvring in offshore operations. Ship Technol. Res. 2015, 62, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, N.; Kornev, N. Validation of hybrid URANS/LES methods for determination of forces and wake parameters of KVLCC2 tanker at manoeuvring conditions. Ship Technol. Res. 2016, 63, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ITTC. Form of Written Discussion at the 30th ITTC Conference. In Proceedings of the 30th ITTC, Tasmania, Australia, 22–27 September 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Knežević, V.; Radonja, R.; Dundović, Č. Emission inventory of marine traffic for the port of zadar. Pomorstvo 2018, 32, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geertsma, R.D.; Visser, K.; Negenborn, R.R. Adaptive pitch control for ships with diesel mechanical and hybrid propulsion. Appl. Energy 2018, 228, 2490–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van, T.; Ristovski, Z.; Pourkhesalian, A.M.; Rainey, T.; Garaniya, V.; Abbassi, R.; Kimball, R.; Luong Cong, N.; Jahangiri, S.; Brown, R.J. A comparison of particulate matter and gaseous emission factors from two large cargo vessels during manoeuvring conditions. Energy Rep. 2019, 5, 1390–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, N.-K.; Choe, H. A quantitative methodology for evaluating the ship stability using the index for marine ship intact stability assessment model. Int. J. Nav. Archit. Ocean Eng. 2021, 13, 246–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francescutto, A. Intact stability criteria of ships—Past, present and future. Ocean Eng. 2016, 120, 312–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.S. On experiment of determining the relationship between ship maneuverability and gravity of metacenter using ship model. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Explor. Eng. 2019, 8, 2060–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMO. Interim Guidelines on the Second Generation Intact Stability Criteria; IMO: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Petacco, N.; Gualeni, P. IMO Second Generation Intact Stability Criteria: General Overview and Focus on Operational Measures. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, T.A.; Perez, T.; Cristofaro, A. Ship Collision Avoidance and COLREGS Compliance Using Simulation-Based Control Behavior Selection with Predictive Hazard Assessment. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2016, 17, 3407–3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aylward, K.; Weber, R.; Lundh, M.; MacKinnon, S.N.; Dahlman, J. Navigators’ views of a collision avoidance decision support system for maritime navigation. J. Navig. 2022, 75, 1035–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Hildre, H.P.; Zhang, H. Toward Time-Optimal Trajectory Planning for Autonomous Ship Maneuvering in Close-Range Encounters. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2020, 45, 1219–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhao, B.; Li, L. Collision Avoidance for Underactuated Ocean-Going Vessels Considering COLREGs Constraints. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 145943–145954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thyri, E.H.; Breivik, M. Collision avoidance for ASVs through trajectory planning: MPC with COLREGs-compliant nonlinear constraints. Model. Identif. Control 2022, 53, 55–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Sun, T. Deep reinforcement learning for collision avoidance of autonomous ships in inland river. In Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers: Transport, London, UK, 11 November 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Y.; Liao, Z.; Chen, D. Differential Evolution Deep Reinforcement Learning Algorithm for Dynamic Multiship Collision Avoidance with COLREGs Compliance. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y. An Intelligent Collision Avoidance Strategy for Inland Waterways. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 157477–157486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potočnik, P. Model Predictive Control for Autonomous Ship Navigation with COLREG Compliance and Chart-Based Path Planning. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; Lai, Y.-H.; Sun, K. Human-like constraint-adaptive model predictive control with risk-tunable control barrier functions for autonomous ships. Ocean Eng. 2024, 308, 118219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdağ, M.; Pedersen, T.A.; Fossen, T.I.; Johansen, T.A. A decision support system for autonomous ship trajectory planning. Ocean Eng. 2024, 292, 116562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Ma, J.; Kouw, W.M. Multiple Variational Kalman-GRU for Ship Trajectory Prediction With Uncertainty. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2025, 61, 3654–3667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Maza, J.A.; Argüelles, R.P. COLREGs and their application in collision avoidance algorithms: A critical analysis. Ocean Eng. 2022, 261, 112029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, D.; Hansen, P.N.; Dittmann, K.; Blanke, M. Anticipation of ship behaviours in multi-vessel scenarios. Ocean Eng. 2022, 266, 112777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, A.; Sun, Y.; Windén, B.; Witherden, F.; Vechan, R.; Fürth, M. SMART-SEA: Ship collision avoidance of stationary structures through integrated machine learning radar image detection and high fidelity maneuvering models. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 202, 107688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Zhou, H.; Grifoll, M.; Martin, A.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, J.; Zheng, P. A Novel Method for Holistic Collision Risk Assessment in the Precautionary Area Using AIS Data. Systems 2025, 13, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.K.; Kim, S.H. Numerical Analysis of Hydrodynamic Interactions Based on Ship Types. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H.; Youn, I.H. The Effect of Feedback on a Remote Operator’s Maneuvering Control for MASS Remote Navigation Competency. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 2025, 33, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.R.; Sun, J.; Li, Z.; Celkis, E.A.; Parsons, D. System identification of a model ship using a mechatronic system. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2010, 15, 316–320. [Google Scholar]

- Velasco, F.J.; Revestido, E.R.; Lõpez, E.; Moyano, E. Identification for a heading autopilot of an autonomous in-scale fast ferry. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2013, 38, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Grimmelius, H.T.; Stapersma, D. Analysis of ship propulsion system behaviour and the impact on fuel consumption. Int. Shipbuild. Prog. 2010, 57, 35–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlandi, L.; Brooks, B.; Bowles, M. A Comparison of Marine Pilots’ Planning and Manoeuvring Skills: Uncovering Mental Models to Assess Shiphandling and Explore Expertise. J. Navig. 2015, 68, 897–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, J.B.; Park, D.J.; Youn, I.H. Development of navigator behavior models for the evaluation of collision avoidance behavior in the collision-prone navigation environment. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Guedes Soares, C.; Zou, Z. Parameter identification of ship maneuvering model based on support vector machines and particle swarm optimization. J. Offshore Mech. Arct. Eng. 2016, 138, 031101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, B.; Yang, J.; Chen, P.; Xiong, J.; Wang, Q. Ship Track Regression Based on Support Vector Machine. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 18836–18846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, L.P. Navigation vector based ship maneuvering prediction. Ocean Eng. 2017, 138, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.C.; Perakis, A.N.; Wang, N. A real-time ship roll motion prediction using wavelet transform and variable RBF network. Ocean Eng. 2018, 160, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugi, L.; Allotta, B.; Pagliai, M. Redundant and reconfigurable propulsion systems to improve motion capability of underwater vehicles. Ocean Eng. 2018, 148, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, G. ANFIS-based course-keeping control for ships using nonlinear feedback technique. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 2019, 24, 1326–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Hinostroza, M.A.; Hassani, V.; Guedes Soares, C. Real-Time Parameter Estimation of a Nonlinear Vessel Steering Model Using a Support Vector Machine. J. Offshore Mech. Arct. Eng. 2019, 141, 061606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xue, Y.; Huang, S.; Xue, G.; Jing, Q. Dynamic model identification of ships and wave energy converters based on semi-conjugate linear regression and noisy input gaussian process. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; Chai, T. Vessel Track Prediction Based on Fractional Gradient Recurrent Neural Network with Maneuvering Behavior Identification. Sci. Program. 2021, 2021, 5526082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yang, P.; Li, S.; Tian, Y.; Liu, G.; Hao, G. Grey-box identification modeling of ship maneuvering motion based on LS-SVM. Ocean Eng. 2022, 266, 112957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Salinas, D.; Chaos, D.; Besada-Portas, E.; López-Orozco, J.A.; De La Cruz, J.M.; Aranda, J. Semiphysical modelling of the nonlinear dynamics of a surface craft with ls-svm. Math. Probl. Eng. 2013, 2013, 890120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ren, J.; Bai, W. MIMO non-parametric modeling of ship maneuvering motion for marine simulator using adaptive moment estimation locally weighted learning. Ocean Eng. 2022, 261, 112103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, G. Nonlinear Identification for 4-DOF Ship Maneuvering Modeling via Full-Scale Trial Data. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2022, 69, 1829–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, G. Nonlinear Innovation-Based Maneuverability Prediction for Marine Vehicles Using an Improved Forgetting Mechanism. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, T.; Yu, C.; Zhong, Y.; Lian, L.; Xiang, X. A self-error corrector integrating K-means clustering with Markov model for marine craft maneuvering prediction with experimental verification. Ocean Eng. 2023, 285, 115420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- My, T.C.; Le, L.D.; Thao, P.M. An Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) Approach for 3 Degrees of Freedom Motion Controlling. Int. J. Inform. Vis. 2023, 7, 301–309. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, K.M.; Maki, K.J. Data-Driven system identification of 6-DoF ship motion in waves with neural networks. Appl. Ocean Res. 2022, 125, 103222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marley, M.; Skjetne, R.; Gil, M.; Krata, P. Four Degree-of-Freedom Hydrodynamic Maneuvering Model of a Small Azipod-Actuated Ship With Application to Onboard Decision Support Systems. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 58596–58609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Huang, L.; Ma, R.; Wang, K.; Wang, T.; Ruan, Z.; Zhang, R.; Jiang, B.; Li, X.; Wu, J. Dynamic nonparametric modeling of sail-assisted ship maneuvering motion based on GWO-KELM. Ocean Eng. 2024, 312, 119060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Y.; Chen, C.Z.; Zou, L.; Zou, Z.J.; He, Y. Echo state network-based black-box modeling and prediction of ship maneuvering motion. Ocean Eng. 2024, 312, 119163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Xue, Y.; Qin, H.; Zhu, Z. Physics-informed identification of marine vehicle dynamics using hydrodynamic dictionary library-inspired adaptive regression. Ocean Eng. 2024, 296, 117013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, L.; Guedes Soares, C. Investigation of Vessel Manoeuvring Abilities in Shallow Depths by Applying Neural Networks. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, L.; Vettor, R.; Guedes Soares, C. Neural Network Approach for Predicting Ship Speed and Fuel Consumption. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zou, L.; He, H.W.; Wu, Z.X.; Zou, Z.J. Real-time prediction of full-scale ship maneuvering motions at sea under random rudder actions based on BiLSTM-SAT hybrid method. Ocean Eng. 2024, 314, 119664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Gao, X.; Huo, C.; Su, W. Research on Maneuvering Motion Prediction for Intelligent Ships Based on LSTM-Multi-Head Attention Model. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.Z.; Liu, S.Y.; Zou, Z.J.; Zou, L. Real-time prediction of ship maneuvering motion in waves based on an improved reduced-order model. Ocean Eng. 2024, 312, 119244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gralak, R.; Muczyński, B.; Przywarty, M. Improving ship maneuvering safety with augmented virtuality navigation information displays. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Zhang, S. Hybrid Deep Learning Approach for Ship Navigation in Curved River Sections Using PPO and CNN. Informatica 2024, 48, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Perera, L.P.; Batalden, B.M. Localized advanced ship predictor for maritime situation awareness with ship close encounter. Ocean Eng. 2024, 306, 117704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Ren, H.; Yu, Z.; Xiao, Z.; Liu, K.; Jiang, H. Self-supervised vessel trajectory segmentation via learning spatio-temporal semantics. IET Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 18, 2242–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Chen, W.; Wu, B.; Wu, H.; Xian, J. Ship visual trajectory exploitation via an ensemble instance segmentation framework. Ocean Eng. 2024, 313, 119368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Xu, H.; Guedes Soares, C. Online non-parametric 4 DOF modelling of ship motion using hybrid kernel relevance vector machine. Ocean Eng. 2025, 332, 121465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, X.; Ren, J.; Hua, Y.; Li, Q. Online nonparametric identification modeling of ship maneuvering motion based on PSO-optimized incremental Gaussian mixture model. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 160, 111962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhou, X.; Liu, K.; Zhou, Y.; Tian, H. Nonparametric Prediction of Ship Maneuvering Motions Based on Interpretable NbeatsX Deep Learning Method. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Yin, X.; Geng, X.; Chen, S.; Yang, J. AISFormer for long-term vessel trajectory prediction. Ocean Eng. 2025, 340, 122098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra-Mora, Y.A.; Acosta, J.Á.; Rodríguez Castaño, Á. Learning port maneuvers from data for automatic guidance of Unmanned Surface Vehicles. Ocean Eng. 2025, 333, 121506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roubos, A.; Groenewegen, L.; Peters, D.J. Berthing velocity of large seagoing vessels in the port of Rotterdam. Mar. Struct. 2017, 51, 202–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Li, G.; Wu, B.; Aesoy, V.; Zhang, H. Parameter identification of ship manoeuvring model under disturbance using support vector machine method. Ships Offshore Struct. 2021, 16, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Rasheed, A.; Steen, S. Ship performance monitoring using machine-learning. Ocean Eng. 2022, 254, 111094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deraj, R.; Sanjeev Kumar, R.S.S.; Alam, M.S.; Somayajula, A. Deep reinforcement learning based controller for ship navigation. Ocean Eng. 2023, 273, 113937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, W. Robust neural path-following control for underactuated ships with the DVS obstacles avoidance guidance. Ocean Eng. 2017, 143, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Liu, T.; Liu, J.; Hu, X.; Shen, W. Trajectory tracking for autonomous surface ships using Gaussian process regression and model predictive control with BVS strategy. J. Mar. Eng. Technol. 2025, 24, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carral, L.; de Lara Rey, J.; Castro-Santos, L.; Carral-Couce, J. Oceanographic research vessels: Defining scientific winches for fisheries science biological sampling manoeuvres. Ocean Eng. 2018, 154, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Hassani, V.; Guedes Soares, C. Uncertainty analysis of the hydrodynamic coefficients estimation of a nonlinear manoeuvring model based on planar motion mechanism tests. Ocean Eng. 2019, 173, 450–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wan, D. CFD Investigations of Ship Maneuvering in Waves Using naoe-FOAM-SJTU Solver. J. Mar. Sci. Appl. 2018, 17, 443–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yin, Y.; Lian, J. A numerical study on flow field and maneuvering derivatives of KVLCC2 model at drift condition. J. Mar. Eng. Technol. 2021, 20, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubbioso, G.; Muscari, R.; Ortolani, F.; Di Mascio, A. Analysis of propeller bearing loads by CFD. Part I Straight Ahead Steady Turn. Maneuvers Ocean. Eng. 2017, 130, 241–259. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, A.B.; Turnock, S.R. Application of the VORTFIND algorithm for the identification of vortical flow features around complex three-dimensional geometries. Int. J. Numer. Methods Fluids 2013, 71, 1461–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balagopalan, A.; Tiwari, K.; Rameesha, T.V.; Krishnankutty, P. Manoeuvring prediction of a container ship using the numerical PMM test and experimental validation using the free running model test. Ships Offshore Struct. 2020, 15, 852–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valčić, M.; Prpić-Oršić, J. Hybrid method for estimating wind loads on ships based on elliptic Fourier analysis and radial basis neural networks. Ocean Eng. 2016, 122, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, L.; Guedes Soares, C. Simulating Ship Manoeuvrability with Artificial Neural Networks Trained by a Short Noisy Data Set. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zihnioğlu, A.; Ertogan, M. Iteratively weighted dynamic modeling of four degrees of freedom motion for marine surface vehicles for k-step ahead prediction. Ocean Eng. 2022, 246, 110614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossen, T.I. Maneuvering coefficient estimation from frequency-dependent added mass and damping: A power-based approach. Ocean Eng. 2025, 341, 122494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revestido, E.R.; Tomás-Rodríguez, M.; Velasco, F.J. Iterative lead compensation control of nonlinear marine vessels manoeuvring models. Appl. Ocean Res. 2014, 48, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalhoub, N.G.; Khaled, N. Integrated controller-observer system for marine surface vessels. J. Vib. Control 2014, 20, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaled, N.; Chalhoub, N.G. A self-tuning guidance and control system for marine surface vessels. Nonlinear Dyn. 2013, 73, 897–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakovlev, S.; Andziulis, A.; Daranda, A.; Vozňák, M.; Eglynas, T. Research on ship autonomous steering control for short-sea shipping problems. Transport 2017, 32, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapitanyuk, Y.A.; Proskurnikov, A.V.; Cao, M. Optimal universal controllers for roll stabilization. Ocean Eng. 2020, 197, 106911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Xu, H.; Yu, W.; Feng, H.; Han, X. Inverse optimal control for speed-varying path following of marine vessels with actuator dynamics. J. Mar. Sci. Appl. 2017, 16, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peymani, E.; Fossen, T.I. Path following of underwater robots using Lagrange multipliers. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2015, 67, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Wang, C.; Yin, Y.; Wang, J. Safety-Certified Constrained Control of Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships for Automatic Berthing. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 72, 8541–8552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skulstad, R.; Li, G.; Fossen, T.I.; Zhang, H. Constrained control allocation for dynamic ship positioning using deep neural network. Ocean Eng. 2023, 279, 114434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, D.; Cheng, P.; Wentao, W.; Zhang, W. Robust adaptive fault-tolerant control for path maneuvering of autonomous surface vehicles with actuator faults based on the noncooperative game strategy. Ocean Eng. 2024, 292, 116541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Li, Z. Hybrid event-triggered control for anti-malicious maneuvering obstacle avoidance of USVs via a velocity obstacle-based dynamic virtual ship guidance. Nonlinear Dyn. 2025, 113, 33587–33601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizythras, P.; Pollalis, C.; Boulougouris, E.; Theotokatos, G. A novel decision support methodology for oceangoing vessel collision avoidance. Ocean Eng. 2021, 230, 109004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuda, R.; Yasukawa, H.; Sano, M.; Hirata, N.; Yoshimura, Y.; Furukawa, Y.; Matsuda, A. Maneuvering simulations of twin-propeller and twin-rudder ship in shallow water using equivalent single rudder model. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 2022, 27, 948–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özden, M.C.; Kurdoğlu, S.; Demir, E.; Sarıöz, K.; Gören, Ö. A compact motion controller-based planar motion mechanism for captive manoeuvring tests. Ocean Eng. 2021, 220, 108195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasukawa, H.; Himaya, A.N.; Hirata, N.; Matsuda, A. Simulation study of the effect of loading condition changes on the maneuverability of a container ship. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 2023, 28, 98–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessandri, A.; Donnarumma, S.; Martelli, M.; Vignolo, S. Motion control for autonomous navigation in blue and narrow waters using switched controllers. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2019, 7, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Kim, T.W.; Sha, O.P.; Misra, S.C. Issues in offshore platform research—Part 1: Semi-submersibles. Int. J. Nav. Archit. Ocean Eng. 2010, 2, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslov, I.; Ambrosovskaya, E.B.; Dvorkin, A.M.; Proskurnikov, A.V.; Mordvintsev, A. Safe Maneuvering Near Offshore Installations: A New Algorithmic Tool. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2022, 47, 895–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.; Xiang, X.; Jiang, C.; Xiang, G.; Yang, S. Survey on traditional and AI based estimation techniques for hydrodynamic coefficients of autonomous underwater vehicle. Ocean Eng. 2023, 268, 113300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmukha Srinivas, K.; Datta, A.; Bhattacharyya, A.; Kumar, S. Free-stream characteristics of bio-inspired marine rudders with different leading-edge configurations. Ocean Eng. 2018, 170, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanvand, A.; Hajivand, A.; Ali, N.A. Investigating the effect of rudder profile on 6DOF ship course-changing performance. Appl. Ocean Res. 2021, 117, 102944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannam, N.P.B.; Krishnankutty, P.; Vijayakumaran, H.; Sunny, R.C. Experimental and Numerical Study of Penguin Mode Flapping Foil Propulsion System for Ships. J. Bionic Eng. 2017, 14, 770–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.; Cao, S.; Philen, M.; Beran, P.S.; Wang, K.G. CFD-CSD coupled analysis of underwater propulsion using a biomimetic fin-and-joint system. Comput. Fluids 2018, 172, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, S.; Peyghami, S.; Parniani, M.; Blaabjerg, F. A comprehensive theoretical approach for analysing manoeuvring effects on ships by integrating hydrodynamics and power system. IET Electr. Syst. Transp. 2022, 12, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, H.; Chen, H. Numerical investigation of interaction between propulsion system behaviour and manoeuvrability of a large containership. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part M J. Eng. Marit. Environ. 2022, 236, 355–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahaji, S.; Chen, L.; Cheung, S.C.P.; Tu, J. Numerical investigation on bubble size distribution around an underwater vehicle. Appl. Ocean Res. 2018, 78, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanada, Y.; Elshiekh, H.; Toda, Y.; Stern, F. ONR Tumblehome course keeping and maneuvering in calm water and waves. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 2019, 24, 948–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volden, Ø.; Cabecinhas, D.; Pascoal, A.; Fossen, T.I. Development and experimental evaluation of visual-acoustic navigation for safe maneuvering of unmanned surface vehicles in harbor and waterway areas. Ocean Eng. 2023, 280, 114675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinostroza, M.A.; Xu, H.; Guedes Soares, C. Cooperative operation of autonomous surface vehicles for maintaining formation in complex marine environment. Ocean Eng. 2019, 183, 132–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, E.J.; Song, I.S.; Kim, S.; Park, S. Autonomous mission-oriented unmanned underwater vehicle control using directional policy optimization. Ocean Eng. 2025, 320, 120242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, H. Optimal path planning for autonomous berthing of unmanned ships in complex port environments. Ocean Eng. 2024, 303, 117641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotovskyi, E.; Moreira, L.; Teixeira, A.P. Assessment of ship manoeuvring models for the development of a collision risk evaluation framework. Ocean Eng. 2025, 342, 123111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helgesen, H.H.; Fuglestad, T.; Cisek, K.; Vik, B.; Kjerstad, O.K.; Johansen, T.A. Inertial Navigation Aided by Ultra-Wideband Ranging for Ship Docking and Harbor Maneuvering. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2023, 48, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.; Liu, H.; Yan, J. Integration of Imaging and Recognition for Marine Targets in Fast-Changing Attitudes With Multistation Wideband Radars. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2024, 60, 1692–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.; Qian, D.; Shu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Xu, R. Vessel navigation risk and stern-swing index in sharp bend channels. Ocean Eng. 2021, 238, 109640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gucma, S.; Gralak, R.; Przywarty, M. Generalized Method for Determining theWidth of a Safe Maneuvering Area for Bulk Carriers at Waterway Bends. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, T.; Dutt, J.K.; Das, A.S. Magnetic Bearings for Marine Rotor Systems-Effect of Standard Ship Maneuver. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2021, 68, 1055–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikula, R.P.; Ruusunen, M.; Keski-Rahkonen, J.; Saarinen, L.; Fagerholm, F. Probabilistic condition monitoring of azimuth thrusters based on acceleration measurements. Machines 2021, 9, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Yuan, S.; Xue, Y.; He, H.; Wu, Z.; Zhao, J.; Xu, Q. OM-Koop: Online Memorable Koopman Operator Learning for Marine Robots Steering Dynamics. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 20354–20365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Diao, M.; Tong, S.; Jiang, L.; Tang, X.; Jiang, P. Numerical simulation study on ship manoeuvrability in mountainous rivers: Comprehensively considering effects of nonuniform flow, shallow water, narrow banks, winds and waves. Ocean Eng. 2024, 306, 118109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broglia, R.; Dubbioso, G.; Durante, D.; Mascio, A.D. Simulation of turning circle by CFD: Analysis of different propeller models and their effect on manoeuvring prediction. Appl. Ocean Res. 2013, 39, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zou, Z.J.; Chen, X.; Xia, L.; Zou, L. CFD-based simulation of the flow around a ship in turning motion at low speed. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 2017, 22, 784–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.H.; Zou, Z.J.; Wang, Z.H.; Wang, J.Q. Path following of underactuated marine vehicles based on model predictive control. Int. J. Offshore Polar Eng. 2020, 30, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iodice, P.; Langella, G.; Amoresano, A. A numerical approach to assess air pollution by ship engines in manoeuvring mode and fuel switch conditions. Energy Environ. 2017, 28, 827–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, R.A.O.; Alvim-Ferraz, M.C.M.; Martins, F.G.; Sousa, S.I.V. The activity-based methodology to assess ship emissions—A review. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 231, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Hekkenberg, R. Sixty years of research on ship rudders: Effects of design choices on rudder performance. Ships Offshore Struct. 2017, 12, 495–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanvand, A.; Hajivand, A.; Ale Ali, N. Investigating the effect of rudder profile on 6DOF ship turning performance. Appl. Ocean Res. 2019, 92, 101918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, B.; Oğuz, E.; Wang, H.; Zhou, P. Multi-criteria decision-making for marine propulsion: Hybrid, diesel electric and diesel mechanical systems from cost-environment-risk perspectives. Appl. Energy 2018, 230, 1065–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, P.; Ouahsine, A.; Tran, K.T.; Sergent, P. Simulation of the overtaking maneuver between two ships using the non-linear maneuvering model. J. Hydrodyn. 2018, 30, 791–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasa, K.; Takeuchi, K.; Chen, C.; Faltinsen, O.M.; Prpić-Oršić, J.; Valčić, M.; Mrakovčić, T.; Herai, N. Evaluation of speed loss in bulk carriers with actual data from rough sea voyages. Ocean Eng. 2019, 187, 106162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutkowski, G. Analysis of a practical method for estimating the ship’s best possible speed when passing under bridges or other suspended obstacles. Ocean Eng. 2021, 225, 108790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, B.; Khan, F.; Veitch, B. A Dynamic Bayesian Network model for ship-ice collision risk in the Arctic waters. Saf. Sci. 2020, 130, 104858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, J.H.; Im, N.K. Development of ship collision avoidance system and sea trial test for autonomous ship. Ocean Eng. 2022, 266, 113120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisowski, J. Sensitivity of safe trajectory in a game environment on inaccuracy of radar data in autonomous navigation. Sensors 2019, 19, 1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Zou, L.; Wu, Z.X.; Liu, S.Y.; Chen, W.M.; Zou, Z.J.; Çelik, C. Integrated path following and collision avoidance control for an underactuated ship based on MFAPC. Ocean Eng. 2025, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; Gang, G.; Tianci, Q.; Kumar, R.; Dong, X.; Shen, Z. Autonomous ship navigation with an enhanced safety collision avoidance technique. ISA Trans. 2024, 144, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Ren, Z.; Marley, M.; Skjetne, R. A Guidance and Maneuvering Control System Design With Anti-Collision Using Stream Functions With Vortex Flows for Autonomous Marine Vessels. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2022, 30, 2630–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uğurlu, H.; Cicek, I. Analysis and assessment of ship collision accidents using Fault Tree and Multiple Correspondence Analysis. Ocean Eng. 2022, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hörteborn, A.; Ringsberg, J.W. A method for risk analysis of ship collisions with stationary infrastructure using AIS data and a ship manoeuvring simulator. Ocean Eng. 2021, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Meng, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Gao, Y. Vessel manoeuvring hot zone recognition and traffic analysis with AIS data. Ocean Eng. 2022, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, J.M.; Guedes Soares, C.G. Geometry and visual realism of ship models for digital ship bridge simulators. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part M J. Eng. Marit. Environ. 2017, 231, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, R.A.O.; Alvim-Ferraz, M.C.M.; Martins, F.G.; Sousa, S.I.V. Assessment of shipping emissions on four ports of Portugal. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 231, 1370–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van, T.; Ristovski, Z.; Pourkhesalian, A.M.; Rainey, T.; Garaniya, V.; Abbassi, R.; Jahangiri, S.; Enshaei, H.; Kam, U.S.; Kimball, R. On-board measurements of particle and gaseous emissions from a large cargo vessel at different operating conditions. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 237, 832–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toscano, D.; Murena, F. Atmospheric ship emissions in ports: A review. Correl. Data Ship Traffic Atmos. Environ. X 2019, 4, 100050. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, T.; Sun, L.; Yang, Z.; Lin, Y.; Chen, Y.; Mao, H. Characterization of PM2.5-bound polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and their derivatives (nitro-and oxy-PAHs) emissions from two ship engines under different operating conditions. Chemosphere 2019, 225, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutkowski, G. Determining the best possible speed of the ship in shallow waters estimated based on the adopted model for calculation of the ship’s domain depth. Pol. Marit. Res. 2020, 27, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Lee, C.K.; Chae, Y.B. Prediction of maneuverability in shallow water of fishing trawler by using empirical formula. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Chen, J.; Xu, L.; Li, H.; Hao, G.; He, Y. Research on Decision-Making Methods for Autonomous Navigation in Inland Tributary Waterways. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastorcic, D.; Radonja, R.; Knežević, V.; Pelic, V. Emission inventory of marine traffic for the port of Šibenik. Pomorstvo 2020, 34, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fameli, K.M.; Kotrikla, A.M.; Psanis, C.; Biskos, G.; Polydoropoulou, A. Estimation of the emissions by transport in two port cities of the northeastern Mediterranean, Greece. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubbioso, G.; Muscari, R.; Ortolani, F.; Di Mascio, A. Numerical analysis of marine propellers low frequency noise during maneuvering. Appl. Ocean Res. 2021, 106, 102461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubbioso, G.; Muscari, R.; Ortolani, F.; Di Mascio, A. Numerical analysis of marine propellers low frequency noise during maneuvering. Part II Passiv. Act. Noise Control Strateg. Appl. Ocean Res. 2022, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-García, G.; Echeverría, R.; Baldasano Recio, J.M.; Kahl, J.D.W.; Granados-Hernández, E.; Alarcón-Jiménez, A.L.; Antonio Duran, R.E. Atmospheric emissions in ports due to maritime traffic in Mexico. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-García, G.; Baldasano Recio, J.M.; Echeverría, R.; Granados-Hernández, E.; Zamora Vargas, E.; Antonio Duran, R.; Kahl, J.W. Estimation of atmospheric emissions from maritime activity in the Veracruz port, Mexico. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2021, 71, 934–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Liu, D.; Wang, X.; Li, S.; Zhang, J.; Qiu, H.; Ding, S.; Hu, K.; Li, W.; Tian, P. Ambient marine shipping emissions determined by vessel operation mode along the East China Sea. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Lau, Y.Y.; Ge, Y.E.; Dulebenets, M.A.; Kawasaki, T.; Ng, A.K.Y. Interactions between Arctic passenger ship activities and emissions. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2021, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagić, R.; Škurić, M.; Dukanović, G.; Nikolić, D. Establishing Correlation between Cruise Ship Activities and Ambient PM Concentrations in the Kotor Bay Area Using a Low-Cost Sensor Network. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalcin, E.; Pehlivan, E.F.; Cetin, B.A.; Aymelek, M. Optimising ship manoeuvring time during port approach using a decision support system: A case study in Turkey. Ships Offshore Struct. 2023, 18, 1713–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, S.L.; Lin, J.L.; Tu, M.R. Utilizing the fuzzy IoT to reduce Green Harbor emissions. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mühmer, M.; la Ferlita, A.; Geber, E.; Ehlers, S.; Di Nardo, E.; El Moctar, O.; Ciaramella, A. A Data-Driven Model for Rapid CII Prediction. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srse, J.; Perkovič, M.; Grm, A. Sediment Resuspension Distribution Modelling Using a Ship Handling Simulation along with the MIKE 3 Application. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanowicz, A.; Kniaziewicz, T. Marine diesel engine exhaust emissions measured in ship’s dynamic operating conditions. Sensors 2020, 20, 6589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunes, R.A.O.; Alvim-Ferraz, M.C.M.; Martins, F.G.; Sousa, S.I.V. Environmental and social valuation of shipping emissions on four ports of Portugal. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 235, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Z.; Yin, J.; Cao, Z. Evaluation of effects of ship emissions control areas: Case study of Shanghai port in China. Transp. Res. Rec. 2017, 2611, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; El Moctar, O. A Fourier-based model for dynamic ship–ship interactions during overtaking in deep and shallow waters. Appl. Ocean Res. 2025, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, W.; Luo, W.; Cui, Z. Intelligent decision-making system for multiple marine autonomous surface ships based on deep reinforcement learning. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2024, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdağ, M.; Tran, H.A.; Lauvås, N.; Pedersen, T.A.; Fossen, T.I.; Johansen, T.A. A Decentralized Negotiation Protocol for Collaborative Collision Avoidance of Autonomous Surface Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. Target following and Close Monitoring Using an Unmanned Surface Vehicle. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2020, 50, 4233–4242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xu, C.; Li, S.; Dong, Z.; Liu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, B. Towards future autonomous tugs: Design and implementation of an intelligent escort control system validated by sea trials. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2025, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xu, C.; Li, S.; Dong, Z.; Hu, X. Event-triggered ADRC-MFAC for intelligent tugs in escort operations with a thrust re-allocation strategy. Control Eng. Pract. 2025, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.; Liu, H.; Zhang, L.; Wang, P.; Wei, J. Integration of Super-Resolution ISAR Imaging and Fine Motion Compensation for Complex Maneuvering Ship Targets Under High Sea State. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Yu, Z.; Li, C. GEO SAR Imaging of Maneuvering Ships Based on Time-frequency Features Extraction. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; He, Y.; Huang, L.; Mou, J.; Wen, J.; Zhang, K. Adaptive collision avoidance decision system for autonomous ship navigation. J. Mar. Eng. Technol. 2025, 24, 132–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Zhang, H.; Deng, Y.; Dong, S. Azimuth Envelope Alignment for Focusing Maneuvering Ships in SAR Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Yu, Z.; Guo, Y.; Li, C. Signal Separation in GEO SAR Imaging of Maneuvering Ships by Removing Micro-Motion Effect. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 788–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Zhang, H.; Deng, Y.; Ren, M. Increase the Coherent Processing Interval for SAR Focusing of Maneuvering Ships by Data Resampling. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbary, M.; ElAzeem, M.H.A. Robust and Flexible Maritime ISAR Tracking Algorithm for Multiple Maneuvering Extended Vessels in Heavy-Tailed Clutter Using Skewed Multiple Model MB-Sub-RMM-TBD Filter. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2024, 49, 1233–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Hong, M.; Li, Y.; Qian, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H. Intelligent Route Planning for Transport Ship Formations: A Hierarchical Global–Local Optimization and Collaborative Control Framework. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; He, Y.; Zhao, X.; Chen, J.; Liu, J.; Huang, L. Dynamic adaptive autonomous navigation decision-making method in traffic separation scheme waters: A case study for Chengshanjiao waters. Ocean Eng. 2023, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman, S.; Bal, S. Turn and zigzag manoeuvres of Delft catamaran 372 using CFD-based system simulation method. Ocean Eng. 2022, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Htein, N.M.; Louvros, P.; Stefanou, E.; Aung, M.; Hifi, N.; Boulougouris, E. AI-Based Optimization Techniques for Hydrodynamic and Structural Design in Ships: A Review. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubbioso, G.; Muscari, R.; Di Mascio, A. Analysis of a marine propeller operating in oblique flow. Part 2: Very high incidence angles. Comput. Fluids 2014, 92, 56–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.F.; Wendt, F. History and State of the Art in Commercial Electric Ship Propulsion, Integrated Power Systems, and Future Trends. Proc. IEEE 2015, 103, 2229–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czaplewski, K.; Zwolan, P. A Vessel’s Mathematical Model and its Real Counterpart: A Comparative Methodology Based on a Real-world Study. J. Navig. 2016, 69, 1379–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Jiao, X.; Lv, C.; Sun, J. Identification of ship motion model based on IPPSA-MTCN-MHSA. J. Comput. Sci. 2025, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerard Hamill, G.A.; Kee, C. Predicting axial velocity profiles within a diffusing marine propeller jet. Ocean Eng. 2016, 124, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Aspect | FGISC | SGISC | Impact on Design and Operation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regulatory Basis | Empirical and experience-based; derived from casualty data and historical performance. | Physics- and performance-based; founded on hydrodynamic modelling and probabilistic simulation. | Enables objective, vessel-specific assessment of dynamic stability. |

| Stability Evaluation Approach | Focused on static stability margins in calm water. | Addresses dynamic stability in waves, considering nonlinear ship–wave interactions. | Improves prediction accuracy under realistic sea conditions. |

| Failure Modes Considered | Limited mainly due to loss of transverse stability. | Considers five dynamic failure modes: parametric rolling, pure loss of stability, dead ship condition, surf-riding/broaching-to, and excessive accelerations. | Expands safety evaluation to include dynamic and operational instabilities. |

| Assessment Levels | Single-level compliance check with deterministic thresholds. | Multi-layered (Lv1–Lv3) approach: from simplified screening to full Direct Stability Assessment (DSA). | Provides flexible fidelity options; balances accuracy and computational cost. |

| Methodology | Static righting-arm curves and GM checks. | Time-domain nonlinear simulations and long-term probabilistic analysis. | Shifts from empirical limits to simulation-supported design validation. |

| Environmental Considerations | Assumes calm or idealised sea states. | Incorporates realistic wave spectra and environmental variability (North Atlantic scatter diagrams, etc.). | Encourages design optimisation for operational environments. |

| Operational Measures | Absent—no explicit operational guidance. | Introduces Operational Limitations (OL) and operational guidance (OG) as complementary safety tools. | Bridges design with real-time operation; supports dynamic risk management. |

| Applicability | Uniform across ship types, often conservative for novel designs. | Adaptable to new ship concepts, unconventional hulls, and hybrid propulsion systems. | Promotes innovation while maintaining safety margins. |

| Integration with Technology | Independent of onboard or digital systems. | Designed for potential coupling with onboard decision support and digital twins. | Enables real-time stability monitoring and AI-assisted navigation. |

| Regulatory Status | Mandatory under IMO 2008 IS Code Part A. | Currently, interim guidelines endorsed by IMO are under evaluation for future adoption. | Encourages trial application and industry feedback before full enforcement. |

| Grouped Papers | Method | Application | Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| SVM-based identification family [84,85,90,121]. | Support vector machines (static and online) | Learning-based hydrodynamic coefficient estimation; real-time steering model identification | Kernel sensitivity; limited generalisation to unseen manoeuvres; not suitable for multi-degrees of freedom (DOF) complex dynamics |

| RBF/Artificial Neural Network (ANN) lightweight neural networks [87,99]. | RBF NN + feedforward ANN | Roll prediction; low-speed manoeuvring control | Overfitting risks; limited predictive horizon; poor interpretability |

| Neuro-fuzzy and unsupervised hybrids [89,98]. | ANFIS + clustering + Markov chains | Course-keeping; regime-shift modelling | Heavy tuning; struggles with rare or unexpected behaviours |

| Gaussian-process and probabilistic ID [91,122]. | Gaussian processes | Identification + uncertainty quantification | High computational cost; difficult scaling to large datasets |

| Grey-box and physics-informed ID [93,94,104]. | Hybrid physics + ML | Physically structured identification | Dependent on physical priors; computationally heavy |

| Nonparametric modelling family [95,96,97]. | Locally weighted learning (LWL), innovation filters, nonlinear regression | Data-driven manoeuvring modelling | Extrapolation poor outside of training regime; requires tuning |

| Reinforcement learning for manoeuvre modelling [111,123,124]. | Proximal Policy Optimisation (PPO), Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), DRL | Manoeuvring in constrained or curved waterways | Requires large training data; reward instability |

| Reservoir computing [103]. | ESN | Black-box prediction | Highly sensitive to spectral radius; unstable unless tuned carefully |

| Deep sequence models [72,92,107,117]. | RNN, BiLSTM, GRU, NBeatsX | AIS prediction; manoeuvre forecasting | Data-intensive; limited interpretability |

| Online learning family [115,116]. | Relevance vector machine (RVM); incremental GMM | Online identification with adaptive updates | Slow training (RVM); cluster drift (GMM) |

| Hydrodynamic and deep learning hybrids [101,109]. | Hybrid deep learning + reduced-order model (ROM) + hydrodynamics | Decision support; wave-influenced manoeuvring | High computational cost; needs quality data |

| Trajectory prediction and vision AI [113,114,118]. | Self-supervised deep nets; instance segmentation; transformer AIS models | AIS-based prediction; segmentation; vision-based manoeuvre analysis | Requires extensive AIS/vision datasets; sensitive to noise |

| Digital-twin family [33,125,126]. | Grey wolf optimiser (GWO)–kernel extreme learning machine (KELM), transformers, Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM)/Gaussian Mixture Regression (GMR) | Digital-twin prediction; port-manoeuvre learning | Requires continuous streaming data; high model complexity |

| Method | Description | Typical Error Range | Applications and Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Empirical and Analytical Models | Based on classical hydrodynamic theory and experimental regression formulas derived from model tests. | ±10–15% | Early-stage design; provides quick approximations but limited accuracy under nonlinear or transient conditions. |

| CFD-Based Simulation such as RANS, Unsteady Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes (URANS), and Large-Eddy Simulation (LES) | Uses computational fluid dynamics solvers to estimate added mass, damping, and control derivatives under defined flow conditions. | ±5–10% | High-fidelity estimation for complex hull forms; captures nonlinear effects and propeller–rudder interactions. |

| Virtual Captive Tests (VCT) | Numerical replication of traditional captive model tests using CFD or hybrid solvers. | ±4–8% | Reduces need for physical model testing; enables broad parametric exploration across speeds and drafts. |

| System Identification (SI) | Derives coefficients from full-scale or model-scale motion data using adaptive or recursive estimation techniques. | ±5–10% | Real-time tuning and onboard calibration; effective under uncertain or variable conditions. |

| Hybrid Physical–Numerical Methods | Combines CFD or experimental results with simplified mathematical models and control-based corrections. | ±4–7% | Balances computational cost and accuracy; suitable for design optimisation and simulator validation. |

| AI-Enhanced Estimation (ML/NN) | Learns nonlinear relationships between motion inputs and hydrodynamic forces directly from data. | ±3–6% | Predictive and adaptive; ideal for digital-twin integration and real-time control of autonomous vessels. |

| Frequency-Domain Identification (Spectral Analysis) | Uses frequency-response data to estimate added mass and damping with high temporal resolution. | ±3–5% | Provides smooth coefficient transitions for control systems; robust under irregular wave conditions. |

| Nonparametric/Data-Driven Models | Employs regression, Gaussian processes, or ensemble learning to predict coefficients without a predefined physical structure. | ±3–5% | Effective for hybrid propulsion and coupled aero–hydrodynamic systems; adapts to evolving vessel conditions. |

| Research Theme and Papers | Methods Used | Key Findings | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Measurement of Manoeuvring Emissions [29,199,218] |

|

|

|

| Comparative Emission Factors (EFs) During Manoeuvring [55] |

|

|

|

| Fuel-Switching and Manoeuvring Scenarios [180] |

|

|

|

| Port-Level Emission Inventories [46,53,120,198,205,206,210,211,219,220] |

|

|

|

| Manoeuvring in Sensitive Environments [212,213] |

|

|

|

| Operational Optimisation for Cleaner Manoeuvring [101,215] |

|

|

|

| Decarbonisation Metrics and Manoeuvring Behaviour [216] |

|

|

|

| Environmental Effects Beyond Air Emissions [202,217] |

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tadros, M.; Aung, M.Z.; Louvros, P.; Pollalis, C.; Nazemian, A.; Boulougouris, E. Ship Manoeuvring Research 2010–2025: From Hydrodynamics and Control to Digital Twins, AI and MASS. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2322. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122322

Tadros M, Aung MZ, Louvros P, Pollalis C, Nazemian A, Boulougouris E. Ship Manoeuvring Research 2010–2025: From Hydrodynamics and Control to Digital Twins, AI and MASS. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(12):2322. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122322

Chicago/Turabian StyleTadros, Mina, Myo Zin Aung, Panagiotis Louvros, Christos Pollalis, Amin Nazemian, and Evangelos Boulougouris. 2025. "Ship Manoeuvring Research 2010–2025: From Hydrodynamics and Control to Digital Twins, AI and MASS" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 12: 2322. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122322

APA StyleTadros, M., Aung, M. Z., Louvros, P., Pollalis, C., Nazemian, A., & Boulougouris, E. (2025). Ship Manoeuvring Research 2010–2025: From Hydrodynamics and Control to Digital Twins, AI and MASS. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(12), 2322. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122322