In the navigational environment of the Arctic Passage, potential accidents involving oil and gas drilling vessels not only endanger human lives and result in significant lost workdays, but also severely disrupt operational productivity [

1]. Furthermore, the downtime resulting from such incidents leads to substantial operating profit losses and unexpected cost increases [

2]. With the increase in Arctic shipping activities, research on ship navigation safety risk assessment technology is becoming increasingly in-depth [

3]. Considering the complexity of ship accidents in Arctic waters, in order to effectively prevent the occurrence of accidents, it is necessary to establish an efficient risk analysis and management system to provide timely and accurate early safety warnings and emergency support for ships. Navigation risk in this context is defined as the likelihood of a vessel encountering hazardous situations (such as entrapment in ice or collision with floating ice) driven by dynamic meteorological and hydrological factors.

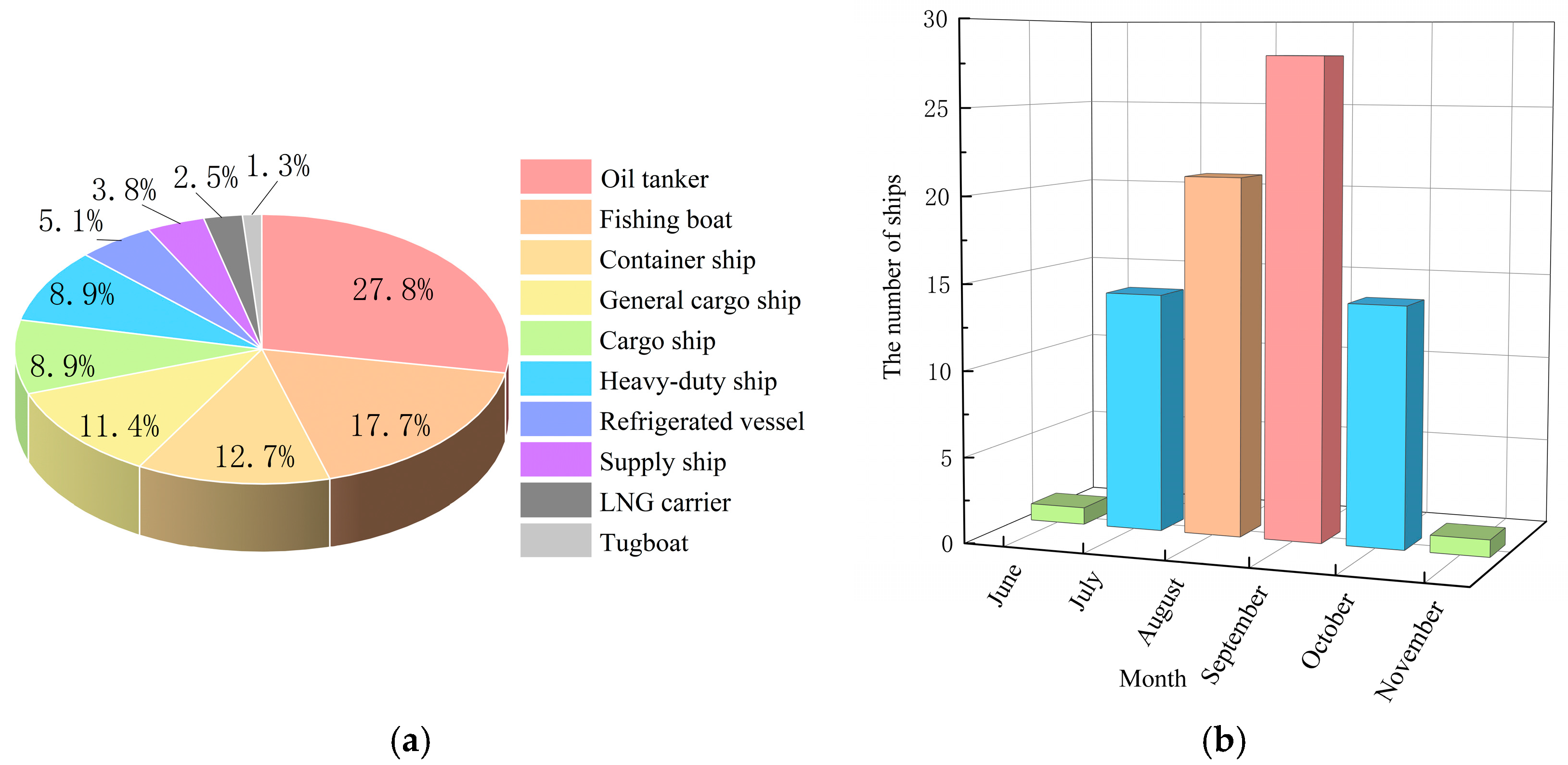

Figure 1 shows the navigation situation of ships in the Northeast Passage of the Arctic.

Figure 1a tallies the types of ships crossing the Northeast Passage of the Arctic. Oil tankers and fishing boats dominate with proportions of 27.8% and 17.7%, respectively.

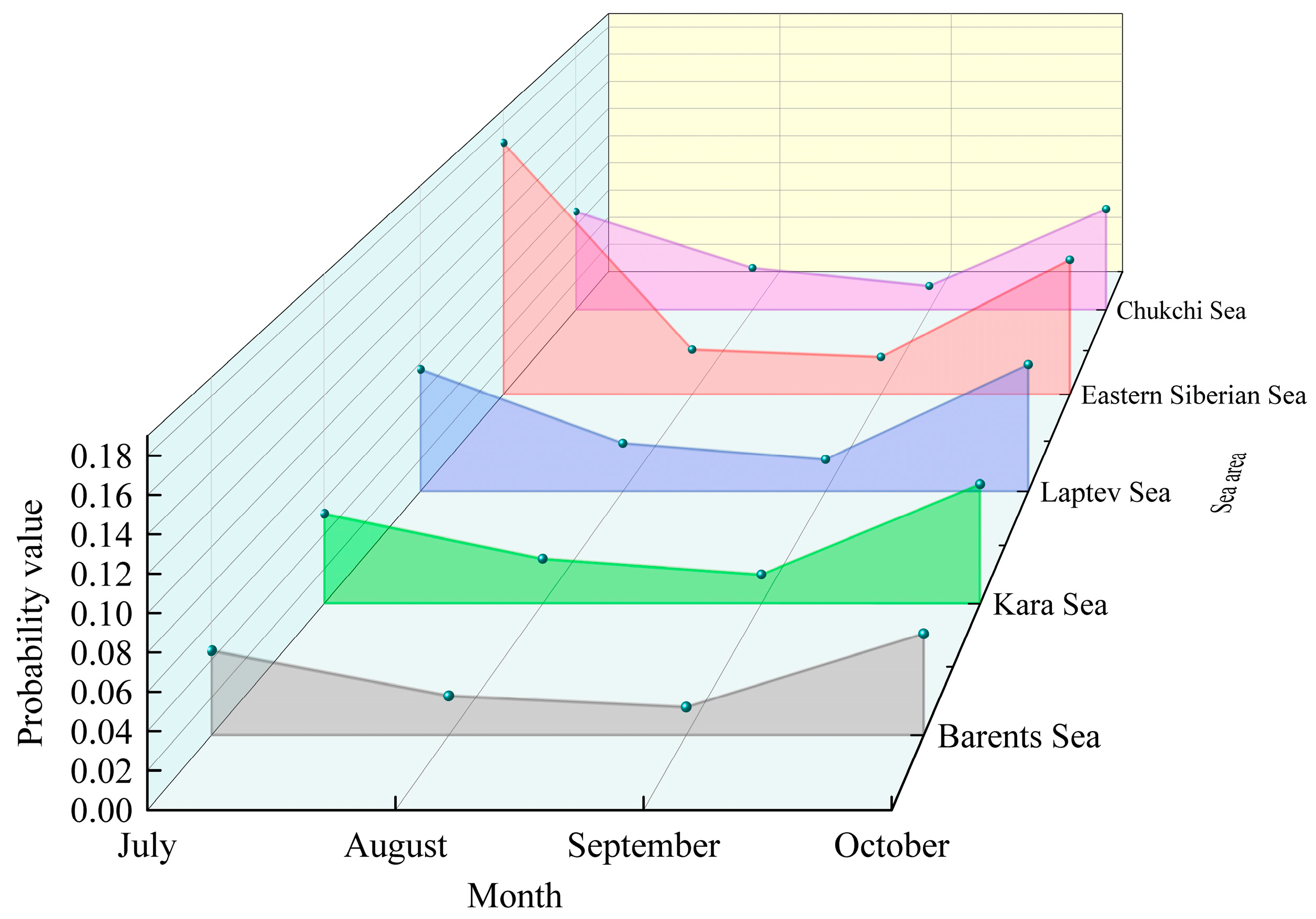

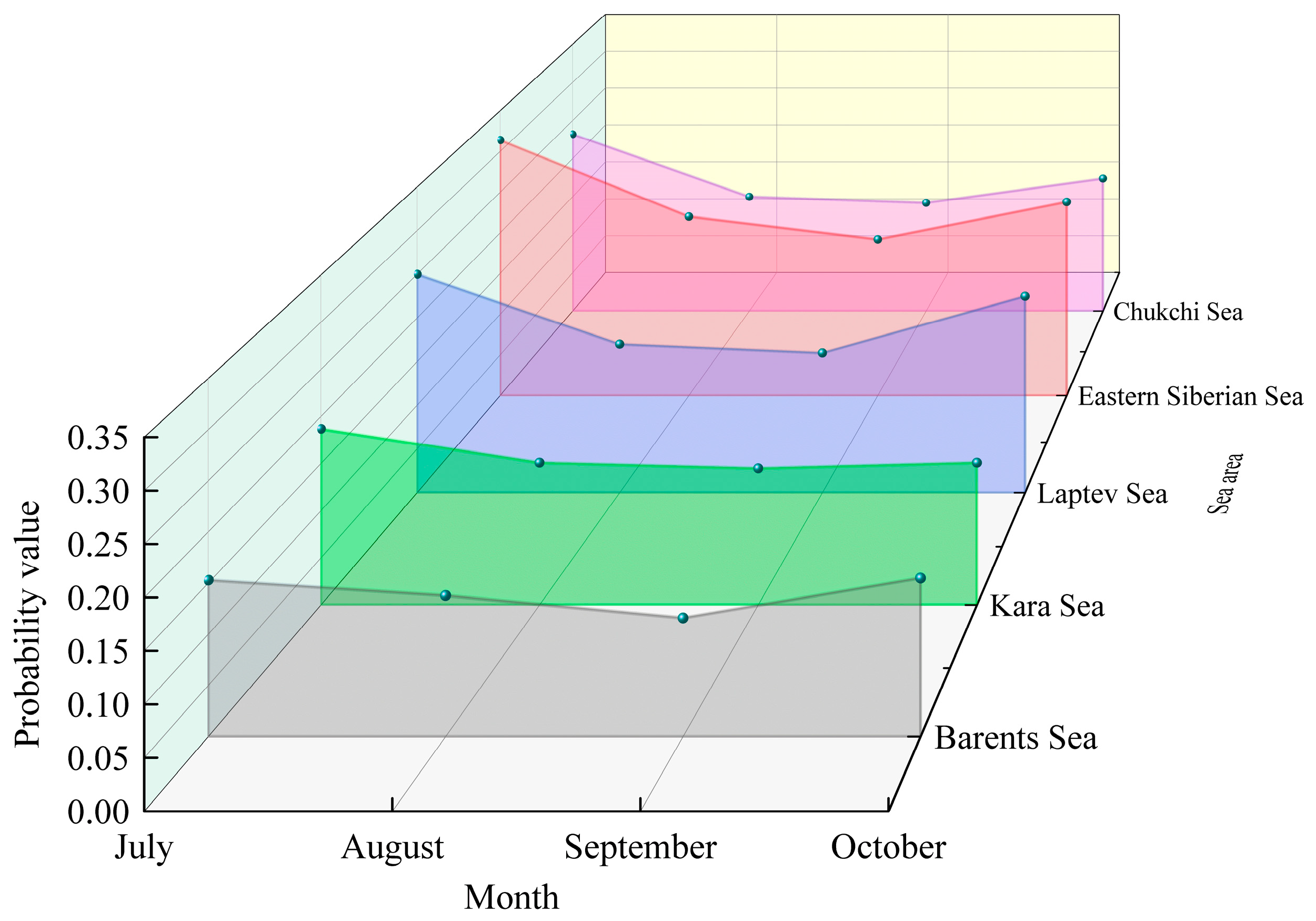

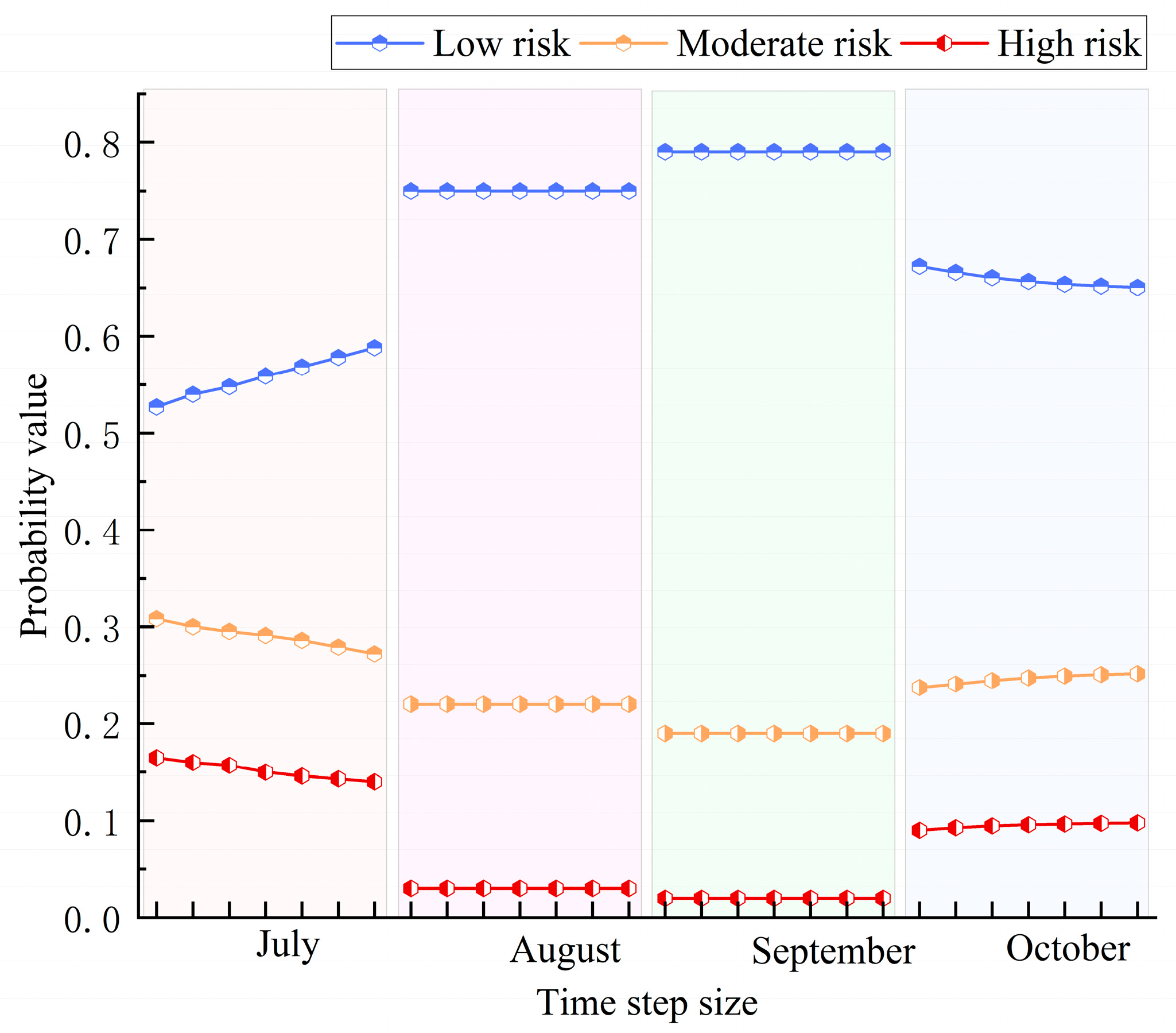

Figure 1b statistically analyzes the ship navigation situation from June to November. It is obvious that sea ice gradually melts in summer. Therefore, July to October is the peak period for navigation, especially in September. Thus, this paper mainly studies the navigation risks of five sea areas in the Northeast Passage of the Arctic from July to October.

In the field of polar shipping safety research, researchers have carried out a large number of studies. Zhenfu Li et al. [

4] and B Sahin [

5] utilized fuzzy analytic hierarchy process and grey fuzzy comprehensive evaluation methods to establish a channel risk identification and quantification model based on the expert knowledge system, achieving a systematic assessment of Arctic navigation risks. Bergstrom et al. [

6] established a complete risk assessment system for the Arctic ship navigation system. By decomposing the shipping system into multiple subsystems for individual design, the applicability of the assessment model was effectively enhanced. Shanshan Fu et al. [

7] constructed a causal probability model based on the Bayesian belief network. This model took the meteorological and hydrological factors around the channel as input variables and achieved the assessment of the ice distress risk of ships in the Arctic sea area by establishing a causal relationship network. Bushra Khan et al. [

8] proposed a ship ice collision risk assessment system based on object-oriented Bayesian networks in the field of polar shipping safety, achieving dynamic prediction of risk probabilities. Moreover, they further simplified complex accident scenarios through a hierarchical decomposition strategy, thereby supporting the dynamic adjustment of navigation decisions. Al-Amin Baksh et al. [

9] analyzed the possibility of accidents such as ship collisions, sinks, and stranding using static Bayesian networks and verified it through case studies of oil tanker navigation. They found that the probability of accidents in the East Siberian Sea was the highest, and through sensitivity analysis, they found that sea ice was the key factor affecting the occurrence of accidents. Heng Qian et al. [

10] conducted a dynamic assessment of the natural environmental risk factors at key nodes of the Northwest Passage of the Arctic using dynamic Bayesian networks. By constructing a risk assessment index system, they identified key navigation nodes and verified the validity of the model based on evidence-based reasoning. This study proves that the dynamic Bayesian network model can effectively handle information uncertainty and provides a certain scientific basis for the research in this paper at the same time. Chi Zhang et al. [

11] proposed a comprehensive risk assessment model based on static Bayesian networks, obtaining the overall risk of ship navigation. Meanwhile, they estimated the probability of accidents and the severity of possible consequences of ship ice trapping and ship ice collision. The validity of the model was verified through case studies, ultimately providing safe speed suggestions for Arctic navigation. Weiliang Qiao et al. [

12] proposed a risk assessment model based on fuzzy Bayesian networks for the security issues of the Northern Sea Route. Among them, emergency response capacity, ice-breaking capacity and rescue, and anti-pollution facilities were the critical factors that contribute to the resilience, and the significant influence of these factors was further verified through sensitivity analysis. Sheng Xu et al. [

13] established a Bayesian network model based on expert opinions to predict the ice-trapped probability of the first assisted vessel in the escort of icebreaker vessels in the Arctic shipping route and verified the validity of the model through actual cases. It was found that ice density, distance between ships and navigation experience are the key factors causing ice entrapment. Shanshan Fu et al. [

14] proposed a quantitative risk assessment model based on object-oriented Bayesian network, selecting four typical accident cases of ship collision, grounding, ice entrapment, and ship–ice collision. The identification of risk factors, risk analysis, and assessment of navigation in the Arctic ice area were systematically analyzed. Based on Arctic wind and ice data in the past decade, Xiaoting Yu et al. [

15] constructed dual indicators of “ice-free/light ice days” and “strong wind disasters”, revealing the risk distribution pattern of the northeast shipping route being higher in the west and lower in the east, and the northwest shipping route being higher on both sides and lower in the middle. The results show that July to October is the best navigation period. The Kara Sea and Barents Sea of the Northeast Passage and the Davis Strait of the Northwest Passage are low-risk areas. Q Wang et al. [

16] focused on the safety risks faced by drilling ships and related equipment in the extremely remote marine environment of the polar regions. Through an accident data-driven sample library and sensitivity analysis, they provided corresponding decision-making suggestions, confirming that this model can effectively predict and identify potential dangers and ensure the continuous and stable development of polar economic activities. Jiacai Pan et al. [

17] systematically reviewed the research progress and deficiencies in the field of navigation safety in the Northwest Passage of the Arctic in recent years and proposed that future research should combine real-time and high-dimensional ice conditions, meteorological and hydrological data to construct more accurate models of navigability, navigation risk and route planning to support scientific decision-making on navigation safety in the Northwest Passage.

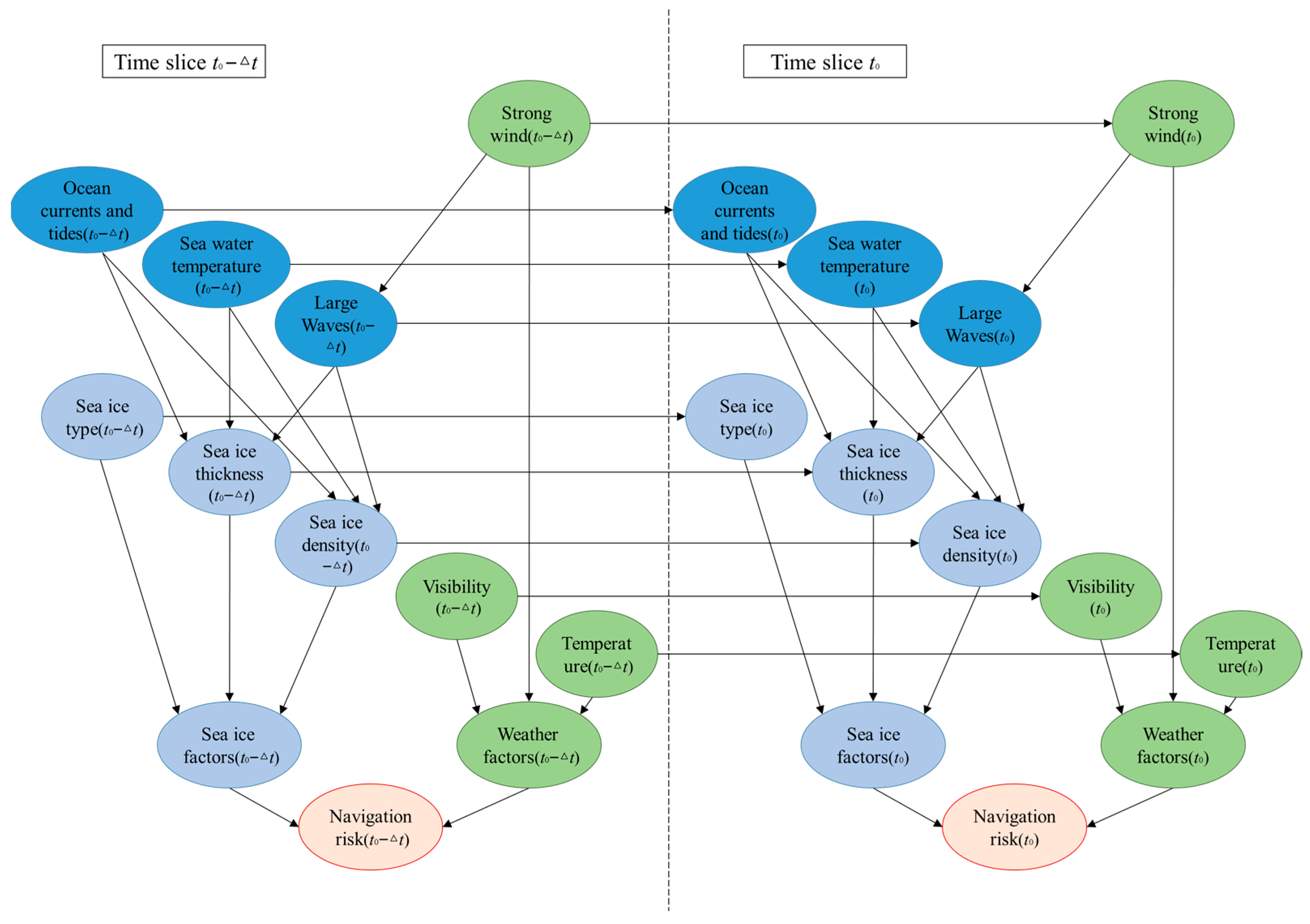

Most of the above-mentioned studies adopt traditional methods (such as analytic hierarchy process, fuzzy comprehensive evaluation, etc.) to assess the navigation risks of the Northeast Passage of the Arctic. Although key risk factors can be identified, they fail to fully consider that ship navigation is a continuous process and its navigation risks will show obvious dynamic evolution characteristics with environmental changes [

18]. The dynamic Bayesian network has strong advantages in dealing with the time-varying laws of risk factors and the related reasoning problems of complex structures. Therefore, based on the natural environment risk factors, this paper selects the dynamic Bayesian network to dynamically evaluate and predict the navigation risks of five important sea areas in the Northeast Passage of the Arctic. Thus, it provides more scientific theoretical support for the dynamic risk assessment, short-term emergency decision-making, and long-term planning of the Arctic shipping routes.

The first part introduces the relevant research methods, mainly including the Interpretative Structural Model and the dynamic Bayesian network. The second part introduces the main risk factors affecting the navigation of the Northeast Passage of the Arctic, mainly including meteorological factors, sea conditions, and ice conditions. The third part introduces the construction of the risk model, mainly including the establishment of the dynamic Bayesian network structure, the discretization processing of risk nodes, data preprocessing, and the calculation of the conditional overview table. The fourth part introduces risk analysis based on dynamic Bayesian networks, mainly including model-based bidirectional reasoning, model validation, and risk prediction applications. The fifth part introduces the conclusion and future work.