Abstract

The phenomenon of seawater flow-freezing exists during ballast water injection and drainage in polar vessels, but the heat transfer and ice evolution behaviors under low-temperature flow conditions remain unclear. This study developed a computational model for ballast tank freezing using the volume of fluid (VOF) and enthalpy–porosity method, and constructed a scaled experimental platform for the simulation model validation. Based on this model, the flow-heat transfer and ice evolution process in the ballast tank are analyzed in detail, with a focus on the influence of injection velocity, pipe diameter, and position on seawater freezing characteristics. The results show that during low-temperature water injection, phase change occurs preferentially in the tank bottom region, with ice presenting as a slurry morphology; when injection velocity increases from 0.25 m/s to 3.5 m/s, the maximum ice-phase volume fraction increases by 48.9%, indicating faster flow accelerates phase-change freezing; compared to other diameters, DN150 piping exhibits the highest turbulent kinetic energy (0.054 m2/s2) and the maximum shear stress (12.49 Pa), demonstrating optimal freezing resistance; compared to bottom injection, sidewall injection intensifies heat transfer/icing near tank walls and increases ice-clogging risk around ports. This study reveals intrinsic mechanisms of dynamic ice-blockage evolution, providing theoretical basis for anti-clogging design in polar ship systems.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the continuous rise in global temperatures has caused massive melting of polar ice layers, drawing high attention from various countries to the development potential of polar routes [1,2]. Domestic and international scholars have conducted extensive research on seawater/ice properties in polar regions [3,4,5], ship-seawater/ice interaction mechanisms [6,7], and optimal anti-icing structural designs for vessels [8]. Under this background, the ballast tank system, as critical equipment ensuring water ballasting for draft control during polar navigation, deserves particular attention regarding its impact under extremely low-temperature environments [9].

During polar navigation, the ship’s ballast tank system injects water via ballast pumps or seawater pressure differential self-flow to adjust vessel stability. If supercooled seawater flows through pipelines, the low-temperature pipe walls induce phase change in seawater, causing ice crystals to nucleate and adhere to the inner pipe surfaces, ultimately leading to complete pipeline blockage. This not only disables the ballast system but may also trigger systemic failures such as pump overload or pipe rupture [10]. Furthermore, ice expansion within tanks can cause deformation and cracking of bulkheads, while uneven ballast water distribution directly compromises the ship’s anti-capsizing capability. Thus, investigating seawater flow-freezing and ice blockage phenomena in ballast tank systems holds critical importance for ensuring polar navigation safety.

Current research on freezing and flow characteristics of supercooled fluid media primarily employs two methods: the phase-field method and the ice slurry two-phase flow method. The phase-field method investigates solidification behavior by simulating microstructural evolution during crystal growth at static microscales [11]. Du et al. [12] established a numerical simulation approach based on the phase-field method to predict microstructural features of aircraft icing, analyzing microstructural evolution under different supercooling conditions. Thoms et al. [13] combined non-conserved order parameter dynamics with salt diffusion through a first-order phase transition model using the phase-field method, examining brine behavior during early sea-ice formation. Fan et al. [14] simulated dynamic evolution of microscopic ice crystals in protein solutions via phase-field method, exploring correlations between phase transition, freezing behavior, and solution concentration. Research on ice slurry two-phase flow focuses on seawater-fragmented ice systems in pipeline networks, analyzing phase-change heat transfer, collision, and accumulation behaviors of floating ice crystals during flow [15]. Onokoko et al. [16] developed a 3D Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) model with ice slurry two-phase flow, revealing increased viscosity and consequent significant pressure drop with rising ice mass fraction. Liu et al. [17] numerically analyzed ice blockage influenced by ice crystal volume and slurry flow velocity, proposing anti-clogging criteria based on critical flow velocity. He Kang et al. [18] described dilute and dense particulate flow states, investigating particle-fluid interaction mechanisms across different particle sizes.

In summary, the phase-field method is primarily tailored for microscale phase-change heat transfer and relies on explicit tracking of the solid–liquid interface. In contrast, ice-slurry models treat ice as discrete particles and focus on macroscale crystal transport, omitting direct simulation of phase-change dynamics. As a result, neither methodology fully captures the real-time phase change process in flowing seawater. To address this limitation, the present study adopts the enthalpy–porosity method, which incorporates a liquid fraction parameter to represent phase transitions implicitly, thereby avoiding the computational cost and complexity associated with explicit interface reconstruction. This formulation not only enhances computational efficiency but also improves accuracy in resolving the continuous transition within the mushy zone, where phase change occurs over a temperature range. Owing to these attributes, the method is particularly well-suited for simulating the dynamic formation of ice slurry during injection, as it intrinsically captures the transient evolution of the mushy region and the resulting slurry-like ice morphology under flow conditions.

It is worth noting that the combination of the enthalpy–porosity method with the VOF method has been widely adopted for resolving real-time phase change in multiphase flows with moving interfaces. This coupled approach effectively resolves the strongly coupled interactions among flow, heat transfer, and ice formation, thereby establishing a comprehensive framework for analyzing transient freezing in polar ballast tank environments.

The performance of ballast water systems is hindered by an inadequate understanding of the coupled heat transfer and ice evolution during seawater flow in cold environments, as well as a lack of systematic anti-clogging theories. To address this, a numerical model combining the VOF and enthalpy–porosity methods was developed and validated experimentally [19]. This model was employed to analyze the freezing process and systematically investigate the effects of injection velocity, pipe diameter, and position, thereby providing a critical reference for optimizing anti-clogging strategies.

2. Numerical Model

2.1. Physical Model and Mesh Model

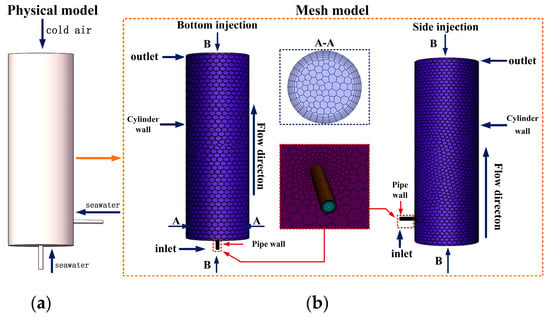

The computational domain of the ballast tank primarily comprises the tank zone, bottom injection zone, and sidewall injection zone, as illustrated in Figure 1a. The injection pipe measures 500 mm in length and 150 mm in diameter, while the water storage cylinder has a height of 8 m and radius of 1 m. SolidWorks 2023 was employed to construct the geometric model of the internal fluid domain, with ANSYS Fluent Meshing 2023 R1 implementing a systematic meshing strategy. Local grid refinement was applied to near-wall regions, combined with multilayer boundary grids to accurately resolve phase-change heat transfer characteristics and flow details within the boundary layer. Ultimately, a high-quality computational mesh dominated by unstructured grids was generated, maintaining a strict minimum global grid size of 0.005 mm (Figure 1b). Supercooled seawater enters the ballast tank through injection pipelines driven either by ballast pumps or by gravity-driven flow. During injection, ventilation pipes or tank hatches must remain open to maintain atmospheric pressure connection, causing rapid temperature drops within the tank. When supercooled seawater flows over ultralow-temperature walls, it triggers phase change to form ice crystals adhering to inner surfaces. Continuous ice accumulation thickens the layer, ultimately leading to complete pipeline blockage.

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic of physical model for ballast tank; (b) The schematic of the mesh model for the ballast tank with bottom injection and side injection.

2.2. Mathematical Model

In Fluent 2023 R1, the VOF model combined with the enthalpy–porosity model enables accurate capture of dynamic phase changes at seawater-solid interfaces [20,21], reflecting differences in wall characteristics. The developed numerical model for seawater freezing integrates gas–liquid two-phase flow equations, the continuum surface force (CSF) model, enthalpy–porosity model, dynamic contact angle model and turbulence model. The assumptions of this model are as follows:

- (1)

- Initial supercooled seawater contains no ice crystal distribution.

- (2)

- Surface tension effects, adhesion forces, and turbulence effects are considered.

- (3)

- Density changes during seawater freezing are neglected, treating the entire fluid domain as incompressible [22].

- (4)

- Precipitation and particle motion of sea-salt crystals during phase change are ignored [23].

2.2.1. Governing Equations

During ballast water intake, the dynamic gas–liquid interface significantly affects the flow field and ice distribution. To account for the influence of interface evolution on heat transfer and phase change, a two-phase flow model based on the VOF method is adopted. The interface is tracked by solving the following transport equation for the volume fraction of the secondary phase:

where is the velocity vector, ρp and αp denote the density and volume fraction of the primary phase fluid. In this model, the gas phase is defined as the primary phase, and the seawater/ice-slurry mixture as the secondary phase. Ice is treated as a liquid in a special state within the secondary phase using the enthalpy–porosity approach. The volume fractions in each computational cell satisfy αp + αs = 1, where subscripts p and s represent the primary (gas) and secondary (liquid) phases, respectively. A value of αp = 1 indicates a cell completely filled with gas, while αs = 1 corresponds to a cell fully occupied by the liquid mixture.

The gas–liquid interface is identified as the iso-surface where the liquid volume fraction equals 0.5, a conventional criterion in VOF-based gas–liquid interface reconstruction [24]. This value represents the midpoint of the phase transition region and provides a consistent reference for interface tracking. A geometric reconstruction scheme with a piecewise-linear representation is employed to accurately capture the interface based on the volume fraction distribution in each cell.

For seawater flow-freezing in ballast tanks, fluid flow is governed by partial differential equations describing continuity and momentum, as shown in Equations (2) and (3):

The immiscible fluids are modeled as a single effective medium, with the local physical properties (ρ, μ and λ) calculated as volume-fraction-weighted averages within each cell. These properties exhibit significant variation only in cells containing the fluid interface. The averaging scheme is given as follows:

To account for surface tension effects, the internal force source term added to the momentum equations follows the CSF model proposed by Brackbill et al. [25], expressed as:

where σ is the surface tension coefficient. к is the interfacial curvature, which is defined as the divergence of the unit normal vector at the gas–liquid interface as follows:

where is the normal direction of the gas–liquid interface, which can be directly obtained from the gradient of the volume fraction.

2.2.2. Phase Change Model

In the phase change model, The solidification of seawater was simulated using the enthalpy–porosity method [26]. In this approach, the mushy zone is treated as a porous medium, with the porosity equal to the liquid fraction. The liquid fraction βliquid is derived from the enthalpy balance and quantifies the liquid phase content within a control volume, defined as:

where Tliquidus and Tsolidus denote the upper and lower temperature thresholds for phase change in the liquid phase, respectively, and their difference corresponds to the phase change temperature difference ΔTf = Tliquidus − Tsolidus. This study adopts Tf = 269.75 K and ΔTf = 0.2 K. thus, Tliquidus = Tf + ΔTf/2 and Tsolidus = Tf − ΔTf/2. The solution of the temperature field essentially involves iteration between the energy equation and the liquid fraction. Once the temperature field is solved, the liquid volume fraction within the fluid and the freezing front can be updated.

For multidimensional solidification/melting problems, the energy conservation equation takes the form of:

The enthalpy–porosity method incorporates phase change by modifying the material enthalpy, eliminating the need for explicit solid–liquid interface tracking. In this approach, the total enthalpy H is defined as the sum of sensible enthalpy h and latent heat ΔL, with the latent heat component being implicitly accounted for through the liquid fraction. This formulation allows the mushy zone to be treated as a porous medium. The enthalpy is given as follows:

the expression for sensible enthalpy h is given as follows:

where href and Tref denote the reference enthalpy and reference temperature, respectively. c denotes the specific heat capacity at constant pressure. The material latent heat ΔL can be obtained using the liquid fraction βliquid.

In this way, ΔL varies from 0 (pure solid) to Lm (pure liquid). During solidification, the porosity decreases from 1 to 0, causing the liquid velocity and momentum to diminish gradually. This momentum attenuation in the mushy zone is given as follows:

where is the momentum source term, and ε = 0.001 is a decimal number to prevent division by zero. Amush is a constant for the mushy zone, reflecting the difficulty of freezing. The larger this value, the shorter the time required for the velocity to decrease to zero. Here, it is set to 1.0 .

2.2.3. Turbulence Model

Various turbulence models, including the k-ε model [27,28], k-ω model [29], large eddy simulation (LES), and direct numerical simulation (DNS), are available for simulating seawater flow. This study employs the Realizable k-ε model to simulate the complex flow in ballast tanks. This model enhances the standard k-ε formulation by introducing a new expression for the turbulent viscosity coefficient (Cμ) and a more accurate dissipation transport equation derived from the mean-square vorticity fluctuation dynamics [30]. These improvements enable superior predictions of jet spreading rates, and of flows involving rotation, strong adverse pressure gradients, separation, and secondary motions. Although LES offers high accuracy for unsteady turbulent structures, its application to wall-bounded flows is often restricted by the Reynolds-number-dependent resolution required to resolve near-wall eddies. In contrast, both Realizable and RNG k-ε models show significant improvements over the standard model for flows with strong curvature and rotation, with the Realizable model demonstrating superior performance for separated and complex secondary flows, making it particularly suitable for capturing the intricate jet-induced flow patterns and vortex structures during ballast water injection. Therefore, the Realizable k-ε model is selected for this work, offering a favorable balance between accuracy and computational cost. The equations of the Realizable k-ε model are given as follows:

where Gk denotes the turbulent kinetic energy term induced by the laminar velocity gradient. Gb denotes the turbulent kinetic energy term induced by buoyancy. YM epresents the effect of expansion of compressible turbulent fluctuations on the total dissipation rate. Sk and Sε denote the momentum source terms induced by solidification/melting effects. Sij denotes the time-averaged strain rate. C1ε and C2 are constants, with C1ε = 1.44 and C2 = 1.9. σk and σε are the turbulent Prandtl numbers for k and ε, respectively, with σk = 1.0 and σε = 1.2. μ is the dynamic viscosity, in Pa·s. k is the turbulent kinetic energy, in m2/s2. ε is the turbulent dissipation rate, in m2/s3. and μt is the turbulent viscosity coefficient, whose calculation formula is given as follows:

where , , . denotes the mean rotation tensor rate in the rotating reference frame with angular velocity ωk.

2.2.4. Dynamic Contact Angle Model

The wall adhesion effect is modeled by specifying the contact angle θw at the wall, which is defined as the angle between the solid surface and the interface tangent. This angle influences the surface normal direction near the wall for fluids with non-zero contact angles. The resulting wall adhesion force is incorporated into the momentum equation as a source term. To compute the average surface curvature along the contact line, the unit normal vector to the interface in wall-adjacent cells is required, which is given as follows:

where and are the unit vectors in the normal and tangential directions of the wall surface, respectively.

In numerical simulations, contact angle models are primarily classified as static or dynamic. The static model neglects hysteresis and assigns a constant value to the equilibrium contact angle θe. However, as most real surfaces are not ideally smooth, contact angle hysteresis must be considered. This study employs a dynamic contact angle model, which captures droplet-wall interactions by varying the contact angle based on the contact line velocity. Specifically, the widely used Kistler model [31] is adopted, where the dynamic contact angle is given as follows:

where ucl denotes the contact line velocity, and Ca denotes the capillary number. Considering that the water storage cylinder used in the experiment was made of aluminum alloy, θe was set to 53.35°, and the wall was treated as a hydrophilic surface [32].

2.3. Numerical Methods and Boundary Conditions

The transient flow field in components such as pipes and water storage cylinders was solved using ANSYS/Fluent 2023 R1 to simulate the ballast tank water injection process. A pressure-based coupled algorithm was employed as the solution method. The Realizable k-ε model was selected for turbulence modeling, with near-wall regions handled by the scalable wall function. The multiphase flow was simulated using the VOF model, coupled with the enthalpy–porosity method for phase change monitoring and conversion. An explicit discretization scheme was applied for the volume fraction parameters, and a sharp-interface anti-diffusion model was adopted to accurately capture the gas–liquid interface and freezing front morphology. The working media consisted of air and liquid water, with the physical properties of the liquid water adjusted to represent a 3.5% mass fraction seawater solution [32,33]; specific values are provided in Table 1. The solution was considered converged when overall mass, momentum, and energy conservation were satisfied, and all variable residuals fell below 1.0 × 10−6. The mass conservation error, quantified by comparing the inlet and outlet flow rates of the pipeline, is strictly controlled below 1.0 × 10−5 kg/s. The boundary conditions are set as follows:

Table 1.

Physical property parameters of seawater solution.

Velocity inlet: Seawater is steadily injected into the ballast tank through the pipeline by a flow pump, with the velocity set to 0.25–3.5 m/s, and the inlet temperature set to 273 K according to the actual seawater temperature [34].

Pressure outlet: The ballast tank communicates with the atmosphere, with the pressure set to 10,130 Pa.

Flow channel walls: Other boundaries are set as stationary walls with constant temperature and no-slip conditions, and the wall temperature is set to 219 K according to the actual polar environmental temperature [35].

3. Model Validation

3.1. Mesh Independence Validation

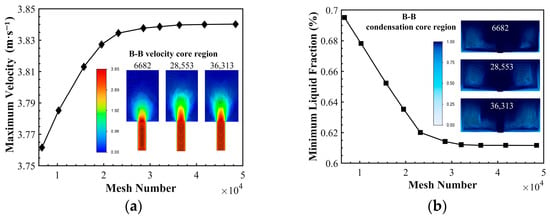

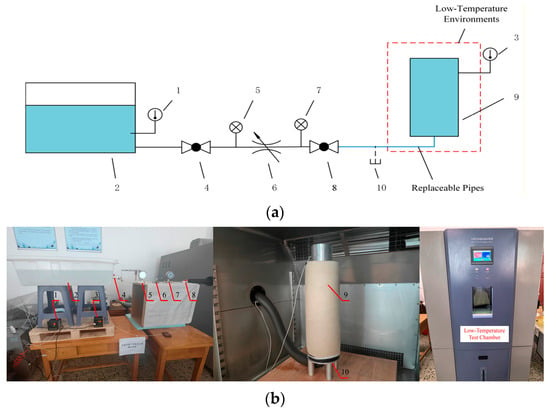

To evaluate the influence of mesh density on seawater flow and phase change, ten unstructured meshes with element counts ranging from 6682 to 48,436 were generated in ANSYS Fluent Meshing 2023 R1. The boundary conditions correspond to Case 5 in Table 2. Figure 2 illustrates the effect of mesh density on the maximum flow velocity and minimum liquid volume fraction in the B-B plane. As mesh density increases, the maximum velocity rises while the minimum liquid fraction decreases. Variations in both parameters become negligible when the mesh element count reaches 28,553 or higher. Accordingly, the mesh with 28,553 elements was selected to investigate dynamic ice formation and ice blockage evolution during low-temperature seawater flow in the open container.

Table 2.

Simulation operating conditions of the constant-volume system.

Figure 2.

The effect of mesh density on the flow freezing process: (a) variation in maximum flow velocity with mesh density; (b) variation in minimum liquid volume fraction with mesh density. The specific location of Section B-B is shown in Figure 1.

3.2. Time Step Independence Validation

A time step sensitivity analysis was performed to ensure temporal independence of the numerical results for seawater flow and phase change. Simulations were conducted with ten time steps ranging from 0.001 s to 0.040 s under the boundary conditions of Case 5 in Table 2. As shown in Figure 3, both the maximum flow velocity and the minimum liquid volume fraction on the B-B plane increase with decreasing time step. When the time step is reduced to 0.004 s or smaller, further changes in these parameters become negligible, confirming numerical convergence. A time step of 0.004 s was therefore selected for all subsequent simulations to balance accuracy and computational efficiency.

Figure 3.

The effect of time step on the flow freezing process: (a) variation in maximum flow velocity with time step; (b) variation in minimum liquid volume fraction with time step. The specific location of Section B-B is shown in Figure 1.

3.3. Validation of the Mathematical Model

3.3.1. Construction of the Scale-Down Test Bench

Since the heat transfer problem involving pipes and cylinders in the actual ballast tank system occurs over large temporal and spatial scales, scaled-down similarity experiments are necessary for validation. The flow in this study is characterized by a distinct free surface, with gravity acting as the dominant driving force. Therefore, the Froude number (Fr) was selected as the governing similarity criterion for the model, as defined in Equation (25):

where Len is the characteristic length in meters (m). u is the flow velocity in meters per second (m/s). g is the gravitational acceleration in meters per second squared (m/s2). By ensuring that the Fr of the test system is consistent with that of the actual system, the two systems exhibit similar physical characteristics. According to the geometric similarity criterion, kinematic similarity criterion, and dynamic similarity criterion: in the scaled-down similarity model experiment, when the geometric scale is reduced by approximately 12.5 times compared to the actual system, the velocity scale and time scale are reduced by 3.5 times. After verification, the acceleration remains unchanged before and after scaling.

The experiment achieved thermodynamic similarity in phase change by matching the Stefan number (Ste = c·ΔT/L). Using a 3.5% NaCl (TianDa Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Tianjin, China) solution to mimic seawater’s specific heat and latent heat, and controlling the supercooling to polar conditions, ensured kinetic similarity in sea ice growth by replicating the latent-to-sensible heat transport ratio.

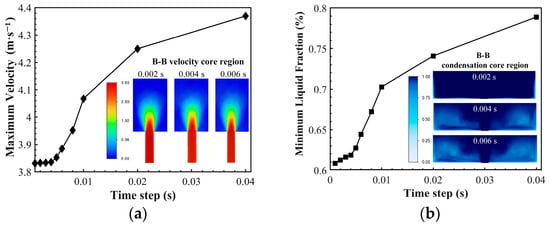

The test bench for investigating dynamic seawater icing and ice blockage consists of three subsystems: flow control, ambient temperature control, and monitoring and acquisition. As shown in Figure 4, the flow control system includes a water source, pipes, a storage cylinder, globe valves, and pressure gauges (Shanghai Jiangyue Instrument Factory, Shanghai, China). Water injection rate is regulated by adjusting the valve opening, while the flow state is monitored in real time via pressure gauges. The ambient temperature control system is built around an SHK-B101 programmable climate chamber (Jianzhuo Instrument Technology Co., Ltd., Suzhou, Jiangsu, China), which accurately simulates polar conditions by controlling the temperature and humidity around the cylinder. To mimic actual ship pipeline conditions, the cylinder and pipes are wrapped with thermal insulation. The monitoring system comprises temperature sensors (Sains Instrument Co., Ltd., Suzhou, Jiangsu, China), stopwatches, cameras (Songdian Technology Co., Ltd., Foshan, Guangdong, China), and a high-precision electronic balance (Sains Instrument Co., Ltd., Suzhou, Jiangsu, China). Ice formation is recorded visually, and icing boundaries in images are extracted using Origin 2024 for thickness calculation with a correction algorithm. Flow-through time is measured with a stopwatch, and injected water mass is weighed electronically. The relationship between flow time and rate is subsequently computed in MATLAB R2023a.

Figure 4.

Seawater flow control system test bench: (a) Experimental schematic diagram; (b) Experimental physical model. 1 Temperature sensor, 2 Water tank, 3 Temperature sensor, 4 Ball valve, 5 Pressure gauge, 6 Throttle valve, 7 Ball valve, 8 Ball valve, 9 Water storage cylinder, 10 Drain outlet.

3.3.2. Experimental Validation

The test bench cools the seawater solution (3.5% NaCl) to 273 K using the ambient temperature control system, with temperature sensors ensuring the medium remains within 273 ± 1 K. A fixed water source height provides a 48 cm initial injection head to simulate original pressure. The flow control system delivers seawater into the temperature-controlled cylinder, while valve adjustments regulate pipeline on-off states under different working conditions. During experiments, icing phenomena are recorded with brackets and cameras, flow-through time is measured with stopwatches, and injected water mass is weighed using a high-precision electronic balance.

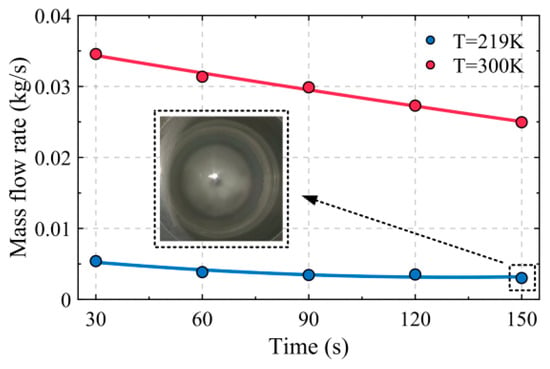

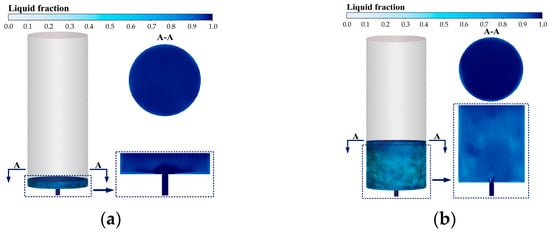

Figure 5 shows the mass flow rate versus time for the seawater solution under fully open valve conditions at room and polar temperatures. Results indicate that the average flow rate of gravity-driven injection decreases over time, with all flow rate curves exhibiting strong temperature sensitivity: lower temperatures lead to reduced flow rates. The average flow rate attenuation at polar temperature (219 K) is approximately 25.69% compared to room temperature (300 K). Notably, throughout the test, despite flow attenuation, no significant ice blockage occurred, and the injected water mass in the storage cylinder continued to increase slowly. A key finding is that maintaining a certain flow velocity trend at the injection port under polar ambient temperature can significantly suppress ice blockage. The phase change preferentially occurs in the cylinder bottom area, primarily forming an ice crystal slurry structure.

Figure 5.

Variation in mass flow rate over time.

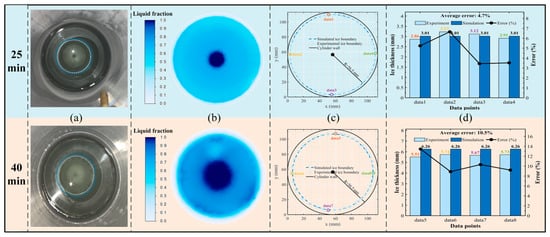

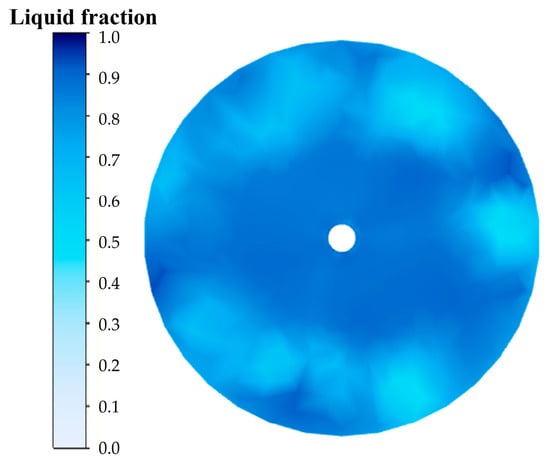

The scale-down model was constructed and meshed using the same methodology as the full-scale model. The time-dependent flow rate curve measured experimentally at 219 K was applied as the velocity inlet boundary condition. As shown in Figure 6, water injection ceases at approximately 25 min. Subsequently, phase change intensifies at the cylinder bottom, with the resulting ice crystal slurry expanding toward the cylinder wall where local icing begins, accompanied by decreased liquid surface clarity. By approximately 40 min, icing further develops at both the bottom and wall regions. Comparative analysis confirms that the simulation effectively captures the temporal evolution of ice morphology and thickness distribution in the water storage cylinder. Section A-A, a horizontal cross-section 5 mm above the cylinder bottom, was monitored for liquid volume fraction. A value ≤ 0.05 indicates the formation of a solid clear ice region. The simulated ice thickness derived using this criterion shows an average error of only 7.6% compared to image-based measurements, falling within an acceptable range and verifying the high reliability of the numerical model.

Figure 6.

At 219 K: A-A cross-section ice layer validation at different times (a) shows the actual icing situation of the A-A cross-section in the experiment. Blue represents the cylinder wall, and light blue represents the ice layer. (b) shows the corresponding liquid volume fraction distribution in the simulation. (c) shows the simulated icing condition, with black representing the cylinder wall and blue representing the ice layer. (d) shows the calculation errors of ice layer thickness at four points (data 1–4) in both the experiment and the simulation.

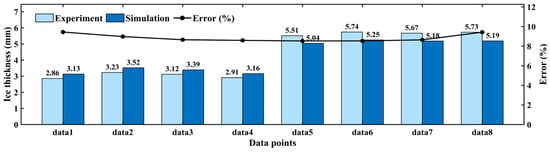

The full-scale numerical model was similarly validated against scaled experimental results. Its velocity inlet was defined by scaling the experimental 219 K flow rate curve according to similarity criteria, while simulated ice thickness was scaled down to the experimental dimensions for direct comparison. As shown in Figure 7, the scaled experimental and full-scale simulation ice thickness values agree closely across multiple data points, with an average error of 8.9%. This close agreement confirms the reliability of the present scaling methodology.

Figure 7.

Validation of ice thickness correspondence between scaled model experiments and full-scale simulations across multiple data points. The simulated ice thickness shown in the figure was obtained by dividing the ice thickness calculated from the full-scale model by the geometric similarity ratio.

4. Results and Discussion

This study systematically examines flow and freezing in large ballast tanks, focusing on three key parameters: injection velocity (0.25–3.5 m/s), pipe diameter (100–200 mm), and injection position. Five velocity gradients reveal how flow rate governs ice formation under constant inlet conditions. Three pipe diameters illustrate how geometry alters flow structures and thermal boundaries to regulate freezing. Two injection positions (center-bottom vs. sidewall) clarify how initial momentum direction affects ice distribution and blockage evolution. These findings offer theoretical support for anti-icing design. Simulation parameters are listed in Table 2.

4.1. The Effect of Injection Velocity on Flow Freezing Characteristics

4.1.1. The Effect of Injection Velocity on Flow Characteristics

As shown in Figure 8a, under the condition of a fixed injection velocity of 0.25 m/s, during the water injection period of 0–240 s, although the Reynolds number () theoretically exceeds the critical value for turbulent transition, the flow field still exhibits typical laminar flow characteristics: the streamlines at the injection port are distributed in parallel bundles, and the velocity gradient is concentrated at the junction of the jet core region and the stationary water body. This phenomenon arises from insufficient flow development in the inlet section. According to classical pipe flow theory, the required flow channel length for fully developed turbulence is , whereas the actual length of the injection pipe is only 0.5 m, far from meeting the requirement for turbulent development. As shown in Figure 8b, at 2040 s with the same injection velocity, the rising liquid level converts gravitational potential energy into kinetic energy. Multi-scale vortices emerge in the instantaneous streamlines, velocity fluctuations intensify, and the streamlines become radially distributed and diffuse. These features confirm significant turbulence. This evolution demonstrates that in confined containers, flow regime transition depends not only on the Reynolds number but is also considerably influenced by spatial scale and boundary constraints.

Figure 8.

Flow characteristics diagram at (a) 240 s and (b) 2040 s under the condition of central bottom water injection with an injection velocity of 0.25 m/s.

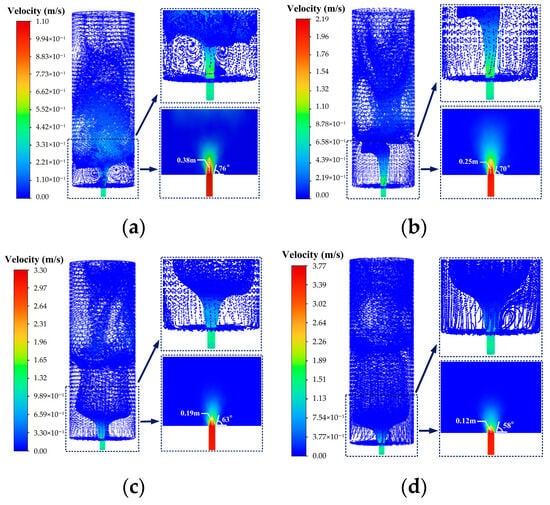

As shown in Figure 9, under a fixed injection time of 240 s, as the injection velocity increases from 1.0 m/s to 3.5 m/s, the flow field remains in a fully developed turbulent state. The radial streamlines and vortex structures induced by secondary flow become increasingly distinct. This behavior stems from the increased initial kinetic energy of the jet, which enlarges the velocity gradient between the jet and the surrounding fluid. According to viscous shear theory, a greater velocity gradient enhances momentum exchange between adjacent layers, thereby intensifying secondary flow and vortical motion. The velocity contour indicates that the jet core length decreases with increasing velocity: from 0.38 m at 1.0 m/s to 0.12 m at 3.5 m/s. Concurrently, the jet angle increases from 14° to 32°, indicating stronger lateral turbulent diffusion. Physically, the higher momentum flux at elevated velocities promotes more intense mixing with the ambient fluid, leading to rapid erosion of the jet core. The larger jet angle further confirms enhanced radial spreading, as the jet overcomes resistance from the surrounding fluid.

Figure 9.

Influence of different water injection velocities at (a) 1.0 m/s, (b) 2.0 m/s, (c) 3.0 m/s and (d) 3.5 m/s on flow characteristics under the condition of central bottom water injection (t = 240 s).

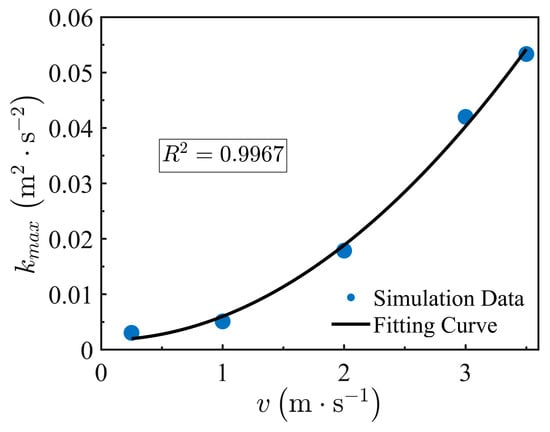

For bottom-center injection, the axisymmetric vertical jet confines turbulence generation and heat transfer to the bottom core region. The cylindrical wall’s confinement is negligible because the jet, being coaxial with the tank, fully develops before reaching the wall, resulting in minimal shear disturbance to the core flow. Therefore, for the central bottom water injection condition, the analysis focuses only on the evolution of parameters at the cylinder bottom. As shown in Figure 10 and Figure 11, the maximum turbulent kinetic energy (kmax) and shear stress (εmax) at the cylinder bottom increase significantly with velocity. The fitting formulas are given as follows:

Figure 10.

Turbulent kinetic energy-velocity relationship.

Figure 11.

Turbulent dissipation rate-velocity relationship.

Turbulent kinetic energy (k) serves as a key parameter for characterizing the intensity of fluctuating motion in fluids. Equation (26) indicates that kmax is proportional to v2, illustrating that turbulent energy primarily originates from the conversion of mean flow kinetic energy. At 3.5 m/s, kmax reaches 0.054 m2/s2, representing a 17.5-fold increase compared to the value at 0.25 m/s, underscoring the dominant role of velocity in turbulent energy input.

The turbulent dissipation rate (ε) quantifies the rate at which turbulent kinetic energy is converted into thermal energy through viscous action, reflecting the intensity of the energy cascade process. Equation (27) shows that εmax scales with v3, consistent with Kolmogorov’s theory of turbulence: energy transferred from large-scale eddies is progressively dissipated at smaller scales, with the dissipation rate increasing cubically with velocity. At 3.5 m/s, εmax attains 6.45 m2/s3, which is 136 times greater than that at 0.25 m/s. This indicates significantly enhanced microscale vortex breakdown and energy dissipation under high-velocity conditions, which intensifies local heat and mass transfer.

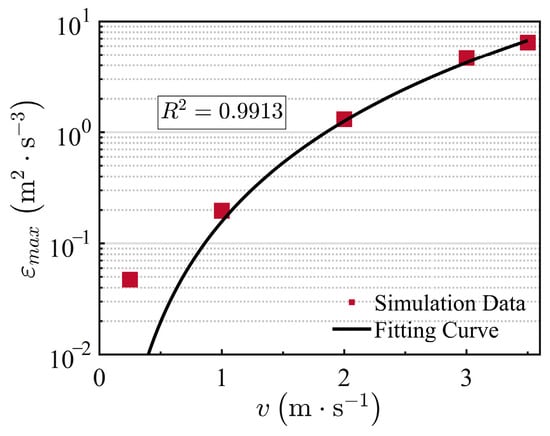

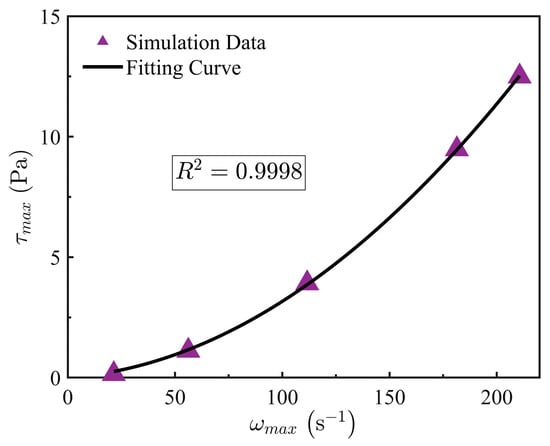

As shown in Figure 12 and Figure 13, the maximum vorticity (ωmax) and turbulent dissipation rate (τmax) at the cylinder bottom increase significantly with velocity. The fitting formulas are given as follows:

Figure 12.

Vorticity-velocity relationship.

Figure 13.

Shear stress-velocity relationship.

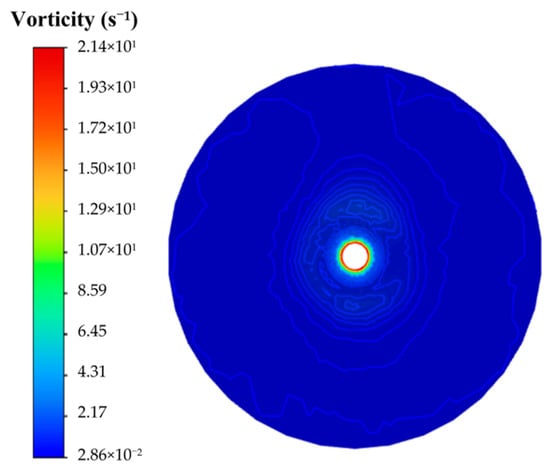

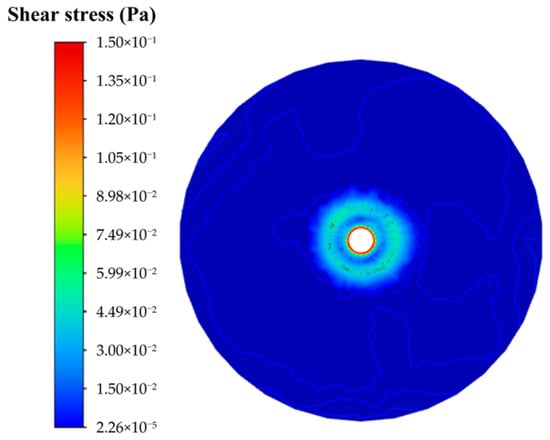

Vorticity (ω) represents the local rotation intensity of the fluid. Equation (28) demonstrates that ωmax follows a power-law relationship with velocity, confirming the conversion of axial jet momentum into rotational fluid motion via viscous shear and pressure gradients. At 3.5 m/s, ωmax reaches 210.7 s−1, a 9.8-fold increase over the value at 0.25 m/s. The resulting high-intensity vortex structures disrupt the ordered aggregation of ice crystals, thereby inhibiting the formation of a continuous ice layer.

Wall shear stress (τ) reflects the mechanical stress exerted by the fluid on the wall surface and serves as a key indicator of the flow’s ability to detach ice crystals. Equation (29) reveals that τmax correlates quadratically with vorticity, leading to nonlinear growth under high-velocity conditions. This is attributed to the combined effect of enhanced rotational shear and steepened velocity gradients near the wall. At 3.5 m/s, τmax reaches 12.5 Pa, an 8.3-fold increase compared to that at 1.0 m/s. As illustrated in Figure 14 and Figure 15, shear stress and vorticity jointly establish a high-intensity stripping force field near the injection port. This synergistic action continuously removes initial ice nuclei from the wall, helps maintain the flow passage integrity, and effectively suppresses ice blockage.

Figure 14.

Vorticity contour at 0.25 m/s (t = 240 s).

Figure 15.

Shear stress contour at 0.25 m/s (t = 240 s).

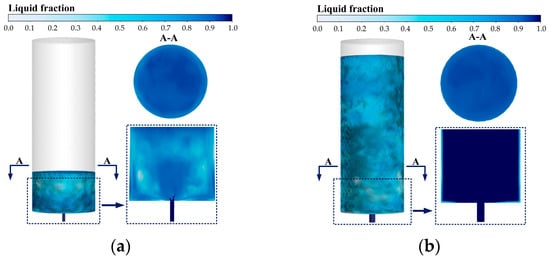

4.1.2. The Influence of Water Injection Velocity on Freezing Characteristics

As shown in Figure 16a, at a fixed injection velocity of 0.25 m/s during 0–240 s, the outlet velocity (0.238 m/s) closely matches the inlet value. Minimal phase change occurs at the bottom and sidewalls, where ice exists as a slurry of stacked crystals without impeding flow. The liquid surface exhibits a uniform phase-change trend, with a minimum liquid volume fraction (βsea) of 0.640. The physical mechanism underlying this phenomenon is that the weak turbulent intensity under low-velocity conditions results in inefficient heat transfer, dominated by natural and weak forced convection. Consequently, only a limited amount of fluid near the wall is cooled to the phase-change temperature. Moreover, the ice crystal formation rate is lower than the rate at which crystals are carried away by the flow, thus preventing the formation of a continuous ice layer. In Figure 16b, under identical conditions but extended to 2040 s, no ice blockage is observed. Phase change intensifies notably, yet no clear ice (βsea ≤ 0.05) forms, and the minimum βsea drops to 0.297. A comparison between Figure 16a,b reveals that longer injection times enhance phase change at the walls. This is attributed to the prolonged duration for heat exchange, which allows continuous cooling and cumulative latent heat release near the walls.

Figure 16.

Freezing characteristics diagram at (a) 240 s and (b) 2040 s under the condition of central bottom water injection with a water injection velocity of 0.25 m/s.

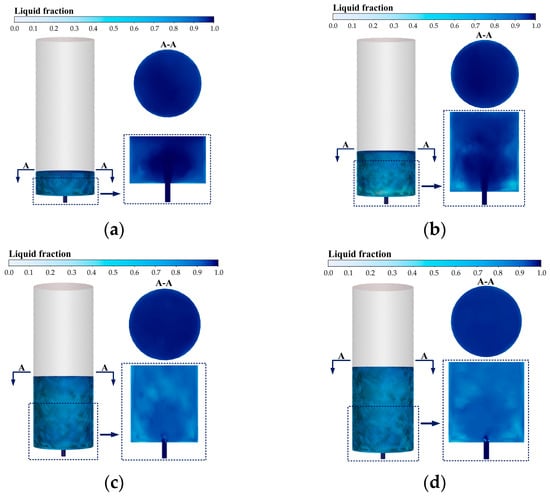

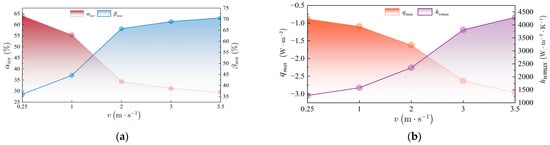

As shown in Figure 16a and Figure 17, under the condition of a fixed water injection time of 240 s, as the water injection velocity increases from 0.25 m/s to 3.5 m/s, the phase change phenomenon at the cylinder bottom and side walls gradually intensifies, manifested as the minimum liquid volume fraction decreasing from 0.640 to 0.294, with specific data shown in Figure 18a. Moreover, the degree of phase change increases from slight to obvious, but no clear ice is formed throughout, and no ice blockage occurs.

Figure 17.

Influence of different water injection velocities at (a) 1.0 m/s, (b) 2.0 m/s, (c) 3.0 m/s and (d) 3.5 m/s on freezing characteristics under the condition of central bottom water injection (t = 240 s).

Figure 18.

Variation relationship of thermodynamic parameters with injection velocity under the condition of central bottom water injection: (a) shows the variation in the maximum ice fraction (αice) and the minimum liquid volume fraction (βsea) in the injection cylinder with the injection velocity. (b) shows the change in hwmax and qmax with the injection velocity.

Simulation results indicate that phase change at the cylinder bottom and sidewalls intensifies with increasing injection velocity under fixed duration. This trend, shown in Figure 18b, arises from enhanced heat transfer due to turbulent intensification and jet impingement. As velocity increases from 0.25 m/s to 3.5 m/s, the wall heat transfer coefficient (h) rises by 235% to 4.29 × 103 W/(m2·K), and the total heat flux (q) increases by 236% to 2.96 × 105 W/m2. The increase in h results from the disruption of the laminar boundary layer by intense vortical structures under high velocity, reducing thermal resistance, while the rise in q stems from both higher h and the maintained temperature gradient. Furthermore, the greater flow rate enlarges the fluid-wall contact area. This combination of improved efficiency and enlarged area accelerates heat extraction, enhancing phase change.

Figure 19a,b show freezing characteristics at a water level of 2.5 m for injection velocities of 0.25 m/s and 3.5 m/s, respectively. Ice blockage is absent in both cases. However, phase change at the bottom and sidewalls is more pronounced at the lower velocity, with a liquid volume fraction 36.1% higher than at the higher velocity. This occurs because the lower injection velocity prolongs the process for the same water level, extending heat exchange duration and compensating for the lower heat transfer coefficient. Additionally, the stable boundary layer at low velocity enhances local supercooling, intensifying phase change. While seemingly contradictory to earlier findings, this indicates a shift in the dominant mechanism under different constraints: under time-limited conditions, high velocity dominates by increasing the heat transfer coefficient and area; under space-limited conditions, low velocity dominates by extending exposure time. Thus, icing extent depends on the combined effect of heat transfer rate and phase change duration.

Figure 19.

Influence of different water injection velocities at (a) 0.25 m/s and (b) 3.5 m/s on freezing characteristics under the condition of central bottom water injection (h1 = 2.5 m).

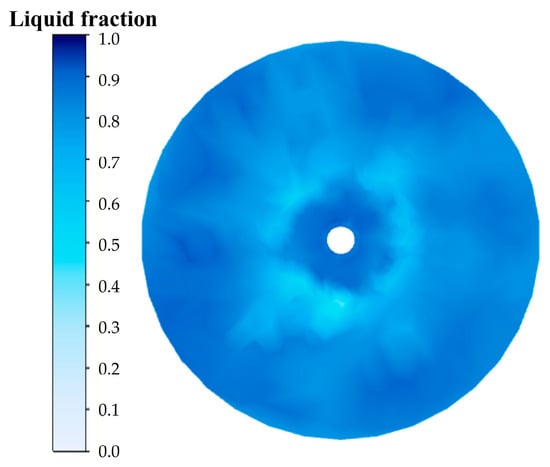

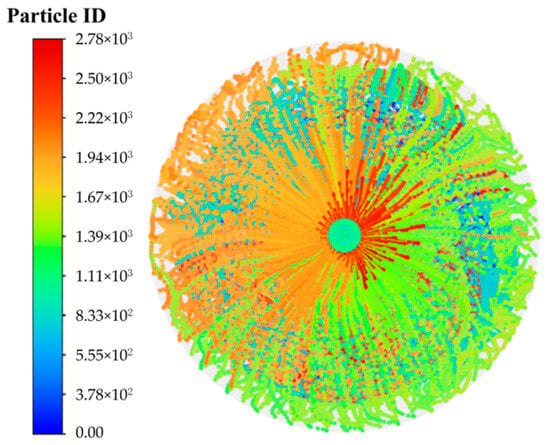

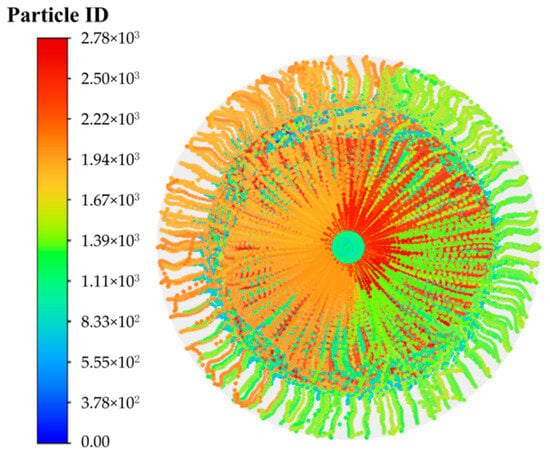

As shown in Figure 20 and Figure 21, the ice morphology at the cylinder bottom varies significantly with injection velocity. At low velocities, the ice forms a radially annular pattern centered on the injection port (Figure 22), resulting from the laminar flow that spreads water uniformly, enabling consistent radial ice growth. In contrast, high velocities produce a disordered, spot-like ice distribution near the wall (Figure 23). In this regime, turbulent fluctuations cause intermittent wall contact and random ice nucleation, while pressure variations lead to chaotic ice growth. Additionally, the high-speed core flow scours the central area, suppressing ice formation, whereas the near-wall separation zone with its stagnant flow promotes crystal accumulation.

Figure 20.

Phase change at the cylinder bottom at 0.25 m/s (h1 = 0.25 m).

Figure 21.

Phase change at the cylinder bottom at 3.5 m/s (h1 = 0.25 m).

Figure 22.

Particle trajectory at the cylinder bottom at 0.25 m/s (h1 = 0.25 m).

Figure 23.

Particle trajectory at the cylinder bottom at 3.5 m/s (h1 = 0.25 m).

4.2. The Influence of Water Injection Pipe Diameter on Flow Freezing Characteristics

4.2.1. The Influence of Water Injection Pipe Diameter on Flow Characteristics

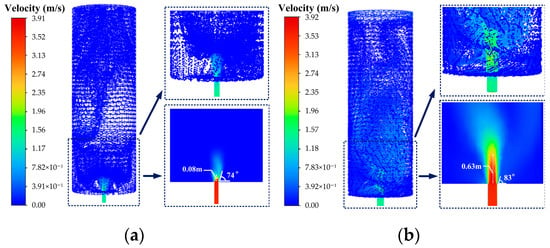

As shown in Figure 24, under the conditions of a fixed water injection velocity (0.25 m/s) and water injection duration (0–240 s), increasing the pipe diameter from 100 mm to 200 mm causes Re to increase significantly from 3.85 × 105 to 7.7 × 105, far exceeding the critical threshold for turbulence. Correspondingly, the flow state transitions from fully developed turbulence to high-intensity turbulence. Simulation results indicate that as the pipe diameter increases, the length of the jet core region exhibits nonlinear growth. Specifically, the core region length under DN100 pipe diameter is only 0.08 m. It extends to 0.12 m for DN150 and significantly elongates to 0.63 m for DN200. This growth is primarily driven by the scaling effects of momentum flux (ρv2A) and volumetric flow rate (vA), both of which are proportional to the square of the pipe diameter. At a low velocity of 0.25 m/s, the limited momentum and flow rate in the small-diameter case (DN100) are rapidly dissipated by viscous effects, causing the core to decay quickly. In contrast, the squared increase in both momentum and flow rate for the large-diameter case (DN200) not only resists ambient mixing but also widens the jet body, thereby prolonging the core region.

Figure 24.

Under the condition of central bottom water injection: Influence of different water injection pipe diameters at (a) DN100 and (b) DN200 on flow characteristics (t = 240 s).

Meanwhile, the jet angle is observed to show a non-monotonic variation trend: 16° for DN100, increasing to 32° for DN150, and sharply decreasing to 7° for DN200. This behavior is closely related to the redistribution of velocity gradients and the evolution of turbulence parameters induced by diameter variation. As the diameter increases from DN100 to DN150, the moderate rise in momentum and flow sustains a high velocity gradient between the jet and the ambient fluid. According to viscous shear theory, such a gradient intensifies secondary flows. Moreover, under DN150 conditions, turbulent vortices are fully developed, with peak turbulent kinetic energy reaching 0.054 m2/s2, promoting continuous entrainment of ambient fluid and enhancing lateral momentum transport, which enlarges the jet angle. However, as the diameter further increases to DN200, the jet momentum rises sharply, and axial inertia significantly surpasses lateral shear, resulting in a “rigid jet” character. Concurrently, the expanded flow area weakens shear effects, turbulent kinetic energy decreases to 0.047 m2/s2, and the velocity profile at the outlet becomes more uniform with a thinner shear layer, collectively suppressing secondary flow and substantially reducing the jet angle.

As summarized in Table 3, the volumetric flow rate increases with the square of the diameter, while the redistribution of velocity gradients leads to nonlinear variations in turbulence parameters, revealing a reorganization of the flow structure. Specifically, turbulent kinetic energy (k) peaks at 0.054 m2/s2 under DN150, reflecting fully developed turbulent vortices and enhanced lateral momentum transport. In contrast, for DN200, the expanded flow passage reduces shear effects, lowering k to 0.047 m2/s2 and restricting lateral fluid diffusion. The turbulent dissipation rate (ε) at the cylinder bottom decreases from 16.32 m2/s3 for DN100 to 6.44 m2/s3 for DN150, then slightly rebounds to 7.26 m2/s3 for DN200, indicating that the reorganization of turbulence structures under large diameters enhances local energy dissipation. The maximum vorticity (ω) at the cylinder bottom continuously decreases with increasing diameter, primarily due to the suppression of vortex generation intensity in the near-wall region. Regarding wall shear stress (τ), the maximum value under DN150 increases by 13.3% compared to DN100, demonstrating the enhanced high-shear boundary layer at medium diameter. Under DN200, however, more uniform velocity gradients cause a 16.7% reduction in τ compared to DN150, confirming the pronounced suppression of flow separation by large pipe diameters.

Table 3.

Physical property parameters induced by changes in pipe diameter.

4.2.2. The Influence of Water Injection Pipe Diameter on Freezing Characteristics

A comparative analysis of Figure 25a,b reveals that at a fixed injection velocity of 3.5 m/s, the pipe diameter exerts a distinct non-monotonic modulating effect on the seawater phase change process, with no ice blockage occurring under any of the investigated conditions. This behavior stems from the coupling of jet structure, turbulent mixing characteristics, and heat transfer processes induced by different pipe diameters.

Figure 25.

Influence of different water injection pipe diameters at (a) DN100 and (b) DN200 on freezing characteristics under the condition of central bottom water injection (t = 240 s).

In the DN200 large-diameter case, the jet exhibits a quasi-collimated structure owing to markedly weakened lateral diffusion and a substantially increased axial momentum flux. This configuration shortens the fluid residence time in the central region and suppresses turbulent mixing, thus inhibiting phase change in the core flow. Consequently, phase change is restricted primarily to the near-wall region influenced by recirculating flow, with minimal occurrence in the center.

In contrast, the DN150 medium-diameter case promotes simultaneous phase change in both the central and wall-adjacent regions. The jet angle reaches 32°, indicating the strongest lateral diffusion, which enhances transverse momentum transport and turbulent agitation. The resulting vortex structures efficiently mix high-temperature central fluid with low-temperature near-wall fluid: the former is entrained toward the wall to absorb cooling, while the latter is carried toward the center. The DN100 case, despite some mixing capacity, shows weaker phase change due to a short jet core and limited momentum. The minimum liquid volume fraction peaks at 0.294 for DN150, which is 61.5% higher than that for DN100, but drops to 0.196 for DN200.

As shown in Table 3, thermodynamic analysis shows that as the pipe diameter increases, the heat transfer coefficient monotonically increases from 4003.89 W/(m2·K) to 4748.95 W/(m2·K), while the heat flux synchronously rises from −2.76 × 105 W/m2 to −3.28 × 105 W/m2, where the negative sign denotes heat extraction from the wall to the fluid. The enlarged flow area increases the fluid-wall contact area and Reynolds number, intensifying turbulent disturbances to disrupt the laminar boundary layer, significantly reduce thermal resistance, and enhance heat transfer. Theoretically, this improves phase-change efficiency; however, the minimum liquid volume fraction varies nonlinearly due to coupling between turbulent structural and heat transfer effects induced by pipe diameter changes.

In terms of turbulent structure, the quasi-collimated jet in the DN200 case slightly recovers the turbulent dissipation rate (ε = 7.26 m2/s3), but the reduction in vorticity and shear stress weakens ice crystal detachment. Suppressed turbulent diffusion also confines the phase-change region to the near-wall area. In contrast, the DN150 case benefits from the synergy of high turbulent kinetic energy and strong shear stress, which enhances both fluid mixing and ice crystal removal. Although the DN100 case exhibits some turbulent mixing capacity, its lower flow rate limits the phase-change extent.

Regarding heat transfer, increasing the pipe diameter monotonically raises the heat transfer coefficient and heat flux, providing greater cooling capacity for phase change. By maintaining peak turbulent kinetic energy and extreme shear stress, the DN150 medium-diameter configuration achieves efficient full-field mixing and heat transfer while ensuring timely ice crystal detachment, thereby establishing an optimal balance between promoting phase change and inhibiting ice accumulation. This confirms that DN150 delivers the best anti-icing performance.

4.3. The Influence of Water Injection Position on Flow Freezing Characteristics

4.3.1. The Influence of Water Injection Position on Flow Characteristics

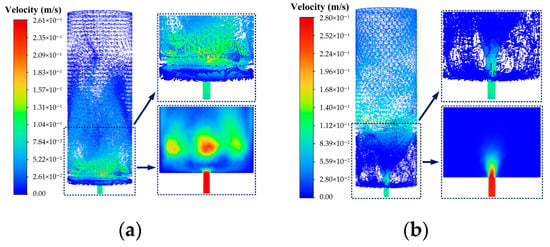

As shown in Figure 26a–d, under the conditions of a fixed water injection velocity of 3.5 m/s and a water injection duration of 0–240 s, the phenomena can be divided into three stages based on the relationship between the liquid level height (h1) and the water injection port height (h2). The distinct jet morphology in each stage results from the coupling of gravity, wall confinement, and inertial forces.

Figure 26.

Flow characteristics diagram at (a) 30 s, (b) 60 s, (c) 90 s and (d) 240 s under the condition of sidewall water injection with an injection velocity of 3.5 m/s.

In the free jet stage (h1 < h2), seawater is ejected at high speed from the sidewall, forming a free jet. The jet core maintains high velocity under inertial dominance, while gravity deflects its axis downward in a parabolic trajectory. Upon impinging the lower liquid surface, its kinetic energy rapidly transforms into intense splashing and air entrainment. The ensuing radial pressure wave propagates along the interface, promoting annular flow, while entrained air amplifies flow disturbances.

In the transition stage (h1 = h2), the jet shifts from a free state to wall-bounded flow, where wall confinement replaces gravity as the dominant factor governing the flow structure. The effluent splits into two parts: one penetrates directly into the liquid, the other spreads horizontally along the surface. Influenced by the Coandă effect, the jet attaches to the opposite wall, forming a high-speed shear layer near the interface. The velocity gradient within this layer triggers vortex generation, driving horizontal circulation in the lower fluid and marking the transition from axial to radial flow dominance.

In the submerged wall jet stage (h1 > h2), a transverse submerged wall jet develops. Constrained and sheared by the wall, the jet adheres closely to the sidewall, forming a thin high-speed layer. The main flow extends horizontally along the wall, dominating horizontal circulation, while gravity drives a downward secondary flow along the wall. The coupling between the horizontal main flow and vertical secondary flow establishes a complex three-dimensional vortex system, where horizontal vortices enhance radial momentum transport and vertical vortices intensify fluid mixing between upper and lower layers.

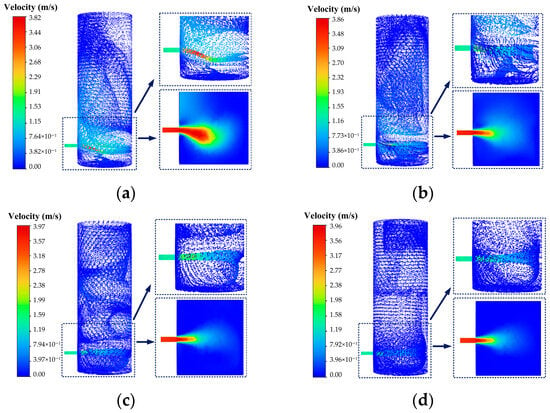

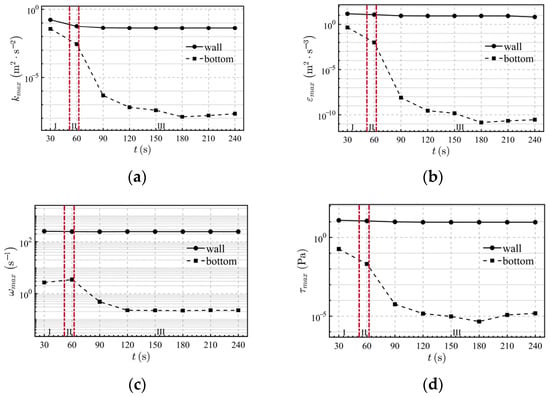

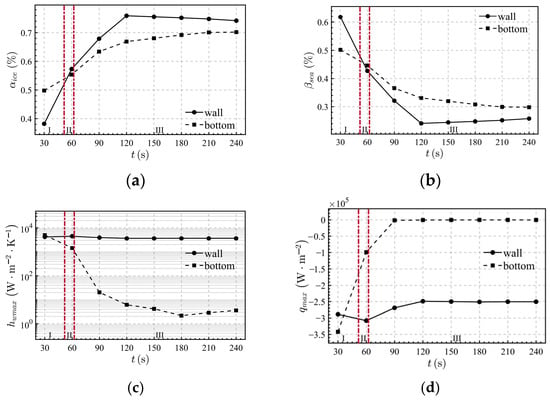

Simulation results show that the flow characteristics of seawater through the sidewall water injection port change in stages over time, including the free jet stage (I: t ≤ 52.79 s), the transition stage (II: 52.79 < t < 61.35 s), and the submerged stage (III: t ≥ 61.35 s). Under the sidewall water injection condition, the influences of both the cylinder wall region and the cylinder bottom region cannot be ignored, requiring independent analysis by region.

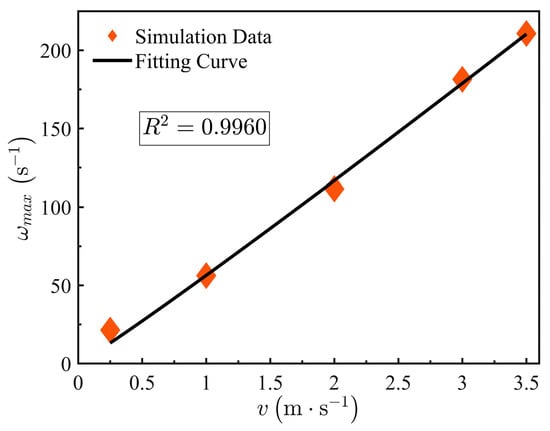

As shown in Figure 27a–d, turbulent energy and associated dynamic forces are highly concentrated near the cylinder wall during sidewall injection, with all parameters decaying rapidly as the flow develops. In the submerged jet stage, the cylinder wall maintains stable turbulent kinetic energy (0.042 m2/s2), dissipation rate (8.55 m2/s3), vorticity (247.4 s−1), and shear stress (9.37 Pa). This stability arises from the continuous wall confinement, which helps sustain shear layer integrity and leads to a balance between turbulence production and dissipation. In contrast, the cylinder bottom experiences only a brief increase in turbulent parameters during the initial free jet stage due to jet impingement. As the jet transitions to a wall-adherent flow, the bottom moves out of the core influence zone, and turbulence levels drop sharply to negligible magnitudes, generally below 10−5.

Figure 27.

Relationship of turbulent parameters: (a) turbulent kinetic energy, (b) turbulent dissipation rate (c) vorticity and (d) shear stress with time under the condition of sidewall water injection with an injection velocity of 3.5 m/s.

Compared to sidewall injection, central bottom injection directly generates substantial turbulent kinetic energy, dissipation rate, vorticity, and shear stress in the cylinder bottom region. These values are comparable to or even exceed those in the wall zone during sidewall injection. This distinction stems from the injection location, which determines the initial region of energy input. In central bottom injection, the jet axis aligns vertically with the tank bottom, allowing kinetic energy to be converted directly into turbulence near the bottom. In sidewall injection, however, most jet energy is dissipated through shear and mixing processes along the wall, with the bottom receiving only indirect influence. Consequently, central bottom injection achieves notably higher energy transfer and mixing efficiency in the bottom region.

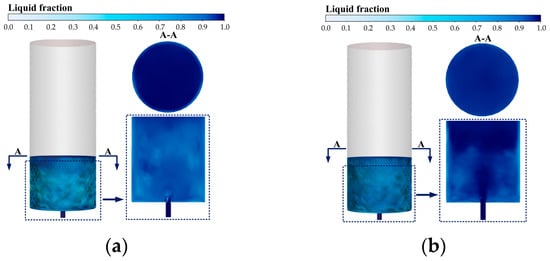

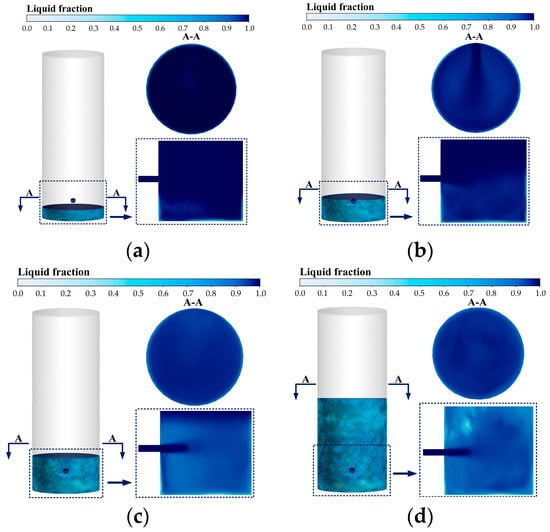

4.3.2. The Influence of Water Injection Position on Freezing Characteristics

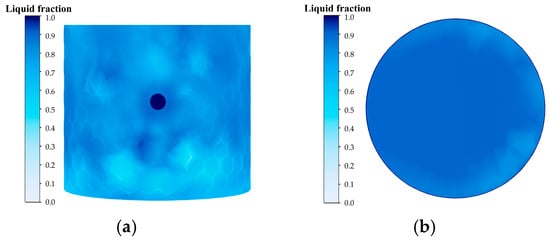

As shown in Figure 28a–d, under a fixed injection velocity of 3.5 m/s and an injection duration of 0–240 s, the phase change at both the cylinder bottom and sidewalls gradually intensifies over time, yet no ice blockage occurs. Compared with central bottom injection, sidewall injection leads to a more distinct “wall-to-interior” phase change pattern, and the process at the liquid surface is strongly influenced by the relative height between the surface and the injection port. This occurs because turbulent energy during sidewall injection concentrates near the wall, making it the primary interface for cooling exchange, while the liquid level further modulates the spatial distribution of phase change by altering the jet–wall interaction.

Figure 28.

Freezing characteristics diagram at (a) 30 s, (b) 60 s, (c) 90 s and (d) 240 s under the condition of sidewall water injection with an injection velocity of 3.5 m/s.

Simulation results further reveal distinct regional differentiation in the thermodynamic response during sidewall injection. As shown in Figure 29a–d, the cylinder wall region consistently sustains high heat transfer coefficients and total heat flux. With continuously increasing ice fraction and decreasing liquid volume fraction, this area establishes itself as the core zone for phase change and heat transfer. The phase change intensity here is significantly higher than in the wall region under central bottom injection (αice: 0.742 vs. 0.495), primarily because the sidewall jet directly impinges on and adheres to the wall, forming a thin liquid film that substantially reduces thermal resistance and facilitates rapid cooling transfer from the wall to the fluid.

Figure 29.

Relationship of thermodynamic parameters: (a) ice fraction, (b) liquid fraction, (c) heat transfer coefficient and (d) total heat flux with time under the condition of sidewall water injection with an injection velocity of 3.5 m/s.

In contrast, the cylinder bottom region exhibits elevated heat transfer coefficients and heat flux only during the initial free jet stage due to jet impact. As the jet transitions to wall-adherent flow, the bottom moves away from the thermal core, and both heat transfer capacity and cooling loss decay sharply to negligible levels.

By comparison, central bottom injection achieves markedly stronger heat transfer performance in the cylinder bottom region, with substantially higher heat transfer coefficients (1280 vs. 3.6 W/(m2·K)) and total heat flux magnitudes (8.81 × 104 vs. 248 W/m2) than sidewall injection in the same region. This advantage stems from the concentration of jet energy in the bottom zone, where intense turbulent disturbances disrupt the laminar boundary layer and significantly enhance cooling transfer efficiency.

As shown in Figure 30a,b, phase change morphology is closely linked to local flow characteristics. On the cylinder wall, ice forms a reticular network near the injection port. This structure results from a subcooled boundary layer created by impinging seawater, which develops into a downward liquid film under the Coandă effect. Continuous cooling initiates ice nucleation, and turbulent disturbances promote anisotropic growth of branched ice ridges. In contrast, phase change at the cylinder bottom is weaker, with crescent-shaped ice accumulation at the edge of the impact zone. Here, wall-flowing seawater impinges and spreads radially, generating near-wall vortices. Their centers facilitate ice accumulation due to low velocity and long residence time, while the central region remains ice-free under high-speed scouring. The crescent zone provides a stable, low-speed stagnation environment conducive to ice growth. In both regions, higher flow velocities intensify phase change by enhancing turbulent agitation and heat transfer.

Figure 30.

Different positions: (a) sidewall and (b) cylinder bottom phase change contour at 3.5 m/s (t = 240 s).

5. Conclusions

To investigate the evolution of seawater flow, heat transfer, and ice formation in ballast water tanks under low-temperature environments, this study developed a computational model for water injection, drainage, and ice formation in large-scale tanks using the VOF and enthalpy–porosity methods. Model reliability under transient conditions was verified by comparing simulated ice thickness (quantitative data) and phase change positions (qualitative features) with results from a scaled experimental model. The effects of injection velocity, pipe diameter, and injection position on seawater flow and freezing behavior were systematically analyzed, providing insights for optimizing anti-clogging strategies in ballast water injection and drainage processes. The main conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- Injection velocity significantly influences system behavior. During low-temperature injection, phase change occurs preferentially at the cylinder bottom, forming an ice slurry structure. No ice blockage was observed under any condition. As the injection velocity increased from 0.25 m/s to 3.5 m/s, the maximum ice volume fraction rose by 48.9%. At a fixed velocity, phase change intensified over time; at the same injection height, lower velocities enhanced phase change. Ice at the bottom formed an annular radial pattern at low velocities, while a disordered spot-like distribution appeared on the wall at high velocities.

- (2)

- Pipe diameter nonlinearly affects system performance. Increasing the diameter raises the volumetric flow rate with a square relationship, but turbulent parameters vary nonlinearly. Considering the coupled effects of turbulent structure and heat transfer, the DN150 pipe exhibited the highest turbulent kinetic energy (0.054 m2/s2) and maximum shear stress (12.49 Pa) among the tested diameters, demonstrating optimal anti-icing performance.

- (3)

- Injection position plays a critical role. The sidewall injection process comprises free jet, transition, and submerged stages. Turbulent energy and heat exchange concentrate near the cylinder wall, with most parameters decaying rapidly across stages. During the submerged stage, the wall maintains high turbulent kinetic energy (0.042 m2/s2), dissipation rate (8.55 m2/s3), vorticity (247.4 s−1), and shear stress (9.37 Pa), while turbulent parameters at the bottom decay to negligible levels. Compared to bottom injection, sidewall injection intensifies heat transfer and ice formation near the wall, increasing the risk of ice clogging around the nozzle and forming a reticular ice structure. Phase change intensity at the bottom is slightly lower than with central bottom injection, showing a crescent-shaped distribution.

Author Contributions

Y.F.: Conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, visualization, writing—original draft preparation, and writing—review and editing. B.P.: Conceptualization, review, methodology, and supervision. P.J.: Conceptualization, review, methodology and supervision. J.R.: Visualization, data curation and writing—review and editing. Y.L.: Investigation and data curation. L.G.: Conceptualization, methodology, validation and supervision. B.L.: Conceptualization and supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely appreciate the valuable comments and constructive suggestions from the editors and reviewers, which have significantly improved the quality and structure of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Abbreviations

| Nomenclature | |||

| Latin letters | Greek letters | ||

| u | Velocity, m/s | α | Volume fraction |

| t | Time, s | β | Liquid fraction |

| p | Pressure, Pa | ρ | Density, kg/m3 |

| Gravity acceleration, m/s2 | μ | Dynamic viscosity, Pa·s | |

| Internal force source term, N/m3 | λ | Thermal conductivity, W/m·K | |

| Momentum source term, N/m3 | σ | Surface tension, N/m | |

| Gas–liquid interface normal | к | Interfacial curvature | |

| Unit normal vector | ε | shear stress, m2/s3 | |

| T | Temperature, k | θ | Contact angle |

| ΔTf | Phase transition temperature difference, K | ω | Vorticity, s−1 |

| H | Material enthalpy, J | τ | turbulent dissipation rate, Pa |

| h | Sensible enthalpy, J | ||

| L | Latent heat, J/(kg·k) | ||

| c | Specific heat capacity, J/(kg·K) | Subscripts | |

| Cμ | Turbulent viscosity coefficient | p | Primary fluid phase |

| k | Turbulent kinetic energy, m2/s2 | s | Secondary fluid phase |

| Ca | Capillary number | ref | Reference |

| Fr | Froude number | m | Mixture |

| Le | Characteristic length, m | f | Freezing |

| Re | Reynolds number | w | Wall surface |

| D | Diameter, m | n | Normal |

| v | Injection velocity, m/s | t | Tangential |

| hw | Wall heat transfer coefficient, W/(m2·K) | e | Static contact angle |

| q | Total heat flux intensity, W/m2 | cl | Contact line |

| A | Area, m2 | ice | Ice |

| h1 | Liquid level height, m | sea | Seawater |

| h2 | Water injection port height, m | max | Maximum |

| Abbreviations | |||

| VOF | Volume of Fluid | LES | Large Eddy Simulation |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics | DNS | Direct Numerical Simulation |

| CSF | Continuum Surface Force | ||

References

- Zhu, Y.F.; Liu, Z.Y.; Xie, D.; Li, W.H. Advancements of the core fundamental technologies and strategies of China regarding the research and development on polar ships. Bull. Natl. Nat. Sci. Found. China 2015, 29, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Liao, Z.K.; Yu, L.W.; Li, H.J. Development Strategy for Marine Scientific Equipment and Technologies. Strateg. Study CAE 2023, 25, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.W.; Liu, Y.H.; Feng, D.X. Analysis of Dynamic Changes in Sea Ice Concentration in Northeast Passage during Navigation Period. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Z.; Chao, N.F.; Li, F.P.; Yue, L.; Wang, S.; Chen, G.; Wang, Z.; Yu, N.; Sun, R.; Ouyang, G.C. Reconstructing Long-Term Arctic Sea Ice Freeboard, Thickness, and Volume Changes from Envisat, CryoSat-2, and ICESat-2. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Huang, C.H.; Wang, Y.H. A Study on the Correlation between Ship Movement Characteristics and Ice Conditions in Polar Waters. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Lee, J.H. Application of Discrete Element Method Coupled with Computational Fluid Dynamics to Predict the Erosive Wear Behavior of Arctic Vessel Hulls Subjected to Ice Impacts. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.W.; Xue, Y.Z.; Lu, X.K. Coupling of Finite Element Method and Peridynamics to Simulate Ship-Ice Interaction. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andryushin, A.V.; Ryabushkin, S.V.; Voronin, A.Y.; Shapkov, E.V. Sharp Profile for Icebreaking Propellers to Improve Their Ice and Hydrodynamic Characteristics. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H. Study on Distribution Characteristics and Prevention and Control Technologies of Ballast Water in Ocean-Going Vessels in Marine Areas of China. Master’s Thesis, Dalian Maritime University, Dalian, China, 2014. Available online: https://cc.cqvip.com/app/search/doc/degree/1870605391 (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Jiang, H.N. Overall Design of 110,000-ton Polar Navigation Tanker. Master’s Thesis, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, X.; Beckermann, C.; Karma, A.; Li, Q. Phase-field simulations of dendritic crystal growth in a forced flow. Phys. Rev. E 2001, 63, 061601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Y.; Xiao, G.; Liu, L.; Gui, Y.; Wei, D.; Yang, X. Study of Solidification and Microstructure Characteristics for Aircraft Icing. Int. J. Thermophys. 2020, 41, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoms, S.; Kutschan, B.; Morawetz, K. Phase-field theory of brine entrapment in sea ice: Short-time frozen micro-structures. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1405.0304. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, T.H.; Li, J.Q.; Minatovicz, B.; Soha, E.; Sun, L.; Patel, S.; Chaudhuri, B.; Bogner, R. Phase-Field Modeling of Freeze Concentration of Protein Solutions. Polymers 2019, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pudasaini, S.P.; Krautblatter, M. A two-phase mechanical model for rock-ice avalanches. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 2014, 119, 2272–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onokoko, L.; Poirier, M.; Galanis, N. Experimental and numerical investigation of isothermal ice slurry flow. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2018, 126, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Hao, L. Simulation on the Distribution of Solid Ice and Prediction of Ice Blockage for Ice Slurry in Horizontal Straight Tubes. Procedia Eng. 2016, 146, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Shi, H.B.; Yu, X.P. The Unified Model for Dilute and Dense Granular Flows Based on the Two-Phase Flow Theory. Eng. Mech. 2023, 40, 24–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.J.; Yu, D.; Gong, J. Similarity Theory of Heat Transfer in Temperature Field Simulation of Oil Storage Tanks. Oil Gas Storage Transp. 2007, 26, 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- ANSYS Inc. ANSYS Fluent Theory Guide; ANSYS, Inc.: Canonsburg, PA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, N.D.; Gada, V.H.; Sharma, A.; Bhardwaj, R. On dual-grid level-set method for contact line modeling during impact of a droplet on hydrophobic and superhydrophobic surfaces. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 2016, 81, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H. Study on the Effect of Bubble Injection on Anti-freezing Performance in Ballast Tanks of Polar Ships. Master’s Thesis, Wuhan University of Technology, Wuhan, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, H.; Xu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.J. Simulation Analysis of Anti-freezing Performance by Bubble Injection in Ballast Tanks of Ice-going Ships. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. (Transp. Sci. Eng.) 2024, 482, 304–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Gong, J.; Wu, X.; Huang, Q. Numerical study on impacting-freezing process of the droplet on a lateral moving cold superhydrophobic surface. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2022, 183, 122044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brackbill, J.U.; Kothe, D.B.; Zemach, C. A continuum method for modeling surface tension. J. Comput. Phys. 1992, 100, 335–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voller, V.R.; Prakash, C. A fixed grid numerical modeling methodology for convection diffusion mushy region phase-change problems. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 1987, 30, 1709–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L. Study on the Dynamics Behavior of Ice Crystals in Sea Ice Two-Phase Flow in Polar Ship Seawater Pipeline System. Master’s Thesis, Wuhan University of Technology, Wuhan, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, R.C. Phase Field Simulation of Ice Crystal Growth in Polar Ship Seawater System and Flow Characteristics in Pipes. Master’s Thesis, Wuhan University of Technology, Wuhan, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.Y. Study on Icing Characteristics of Pressurized Water Supply Pipeline in Civil Aircraft. Master’s Thesis, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Shih, T.H.; Liou, W.W.; Shabbir, A.; Yang, Z.; Zhu, J. New K-Epsilon Eddy Viscosity Model for High Reynolds Number Turbulent Flows: Model Development and Validation. Available online: https://cc.cqvip.com/app/search/doc/report/2911361411 (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Bai, X.; Yang, S.J.; Tian, Y.K. Simulation analysis of the effect of salinity on the microscopic characteristics of seawater icing based on improved phase field method. J. Ship Mech. 2022, 26, 1496–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.F.; Wang, Y.K.; Ju, L.; Wang, Q. Phase field simulation of ice crystal growth in seawater freezing process. J. Harbin Eng. Univ. 2020, 41, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.L.; Xi, C.W.; Dong, B.; Yu, H.D. Icing Performance of Micro-Nano Composite Grooved Aluminum Alloy Surface. China Surf. Eng. 2018, 31, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.J.; Kang, J.C. Microstructure Analysis of Multi-year Sea Ice Grown in the Arctic. J. Glaciol. Geocryol. 2001, 23, 383–388. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Q.W.; Qin, B.B.; Tang, Z.; Liu, Y.G.; Chen, Z.H.; Guo, J.T.; Xiong, Z.F.; Li, T.G. Calcification of Modern Planktonic Foraminifera Neogloboquadrina pachyderma (sinistral) in the Antarctic Zone of the Southern Ocean Controlled by Sea Temperature Rather than Ocean Acidification. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2022, 52, 2152–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).