Snow and Sea Ice Melt Enhance Under-Ice pCO2 Undersaturation in Arctic Waters

Abstract

1. Introduction

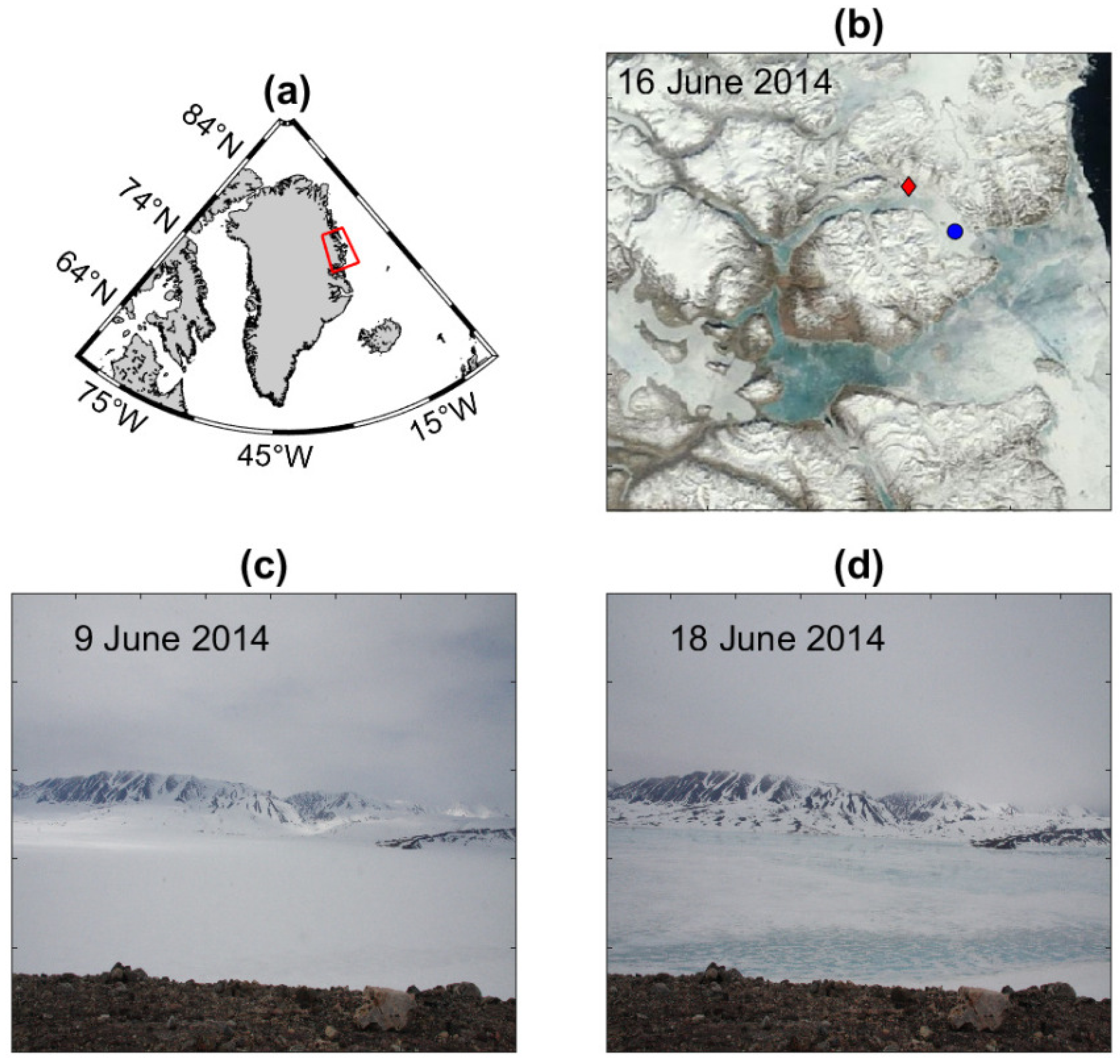

2. Regional Settings

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Sampling

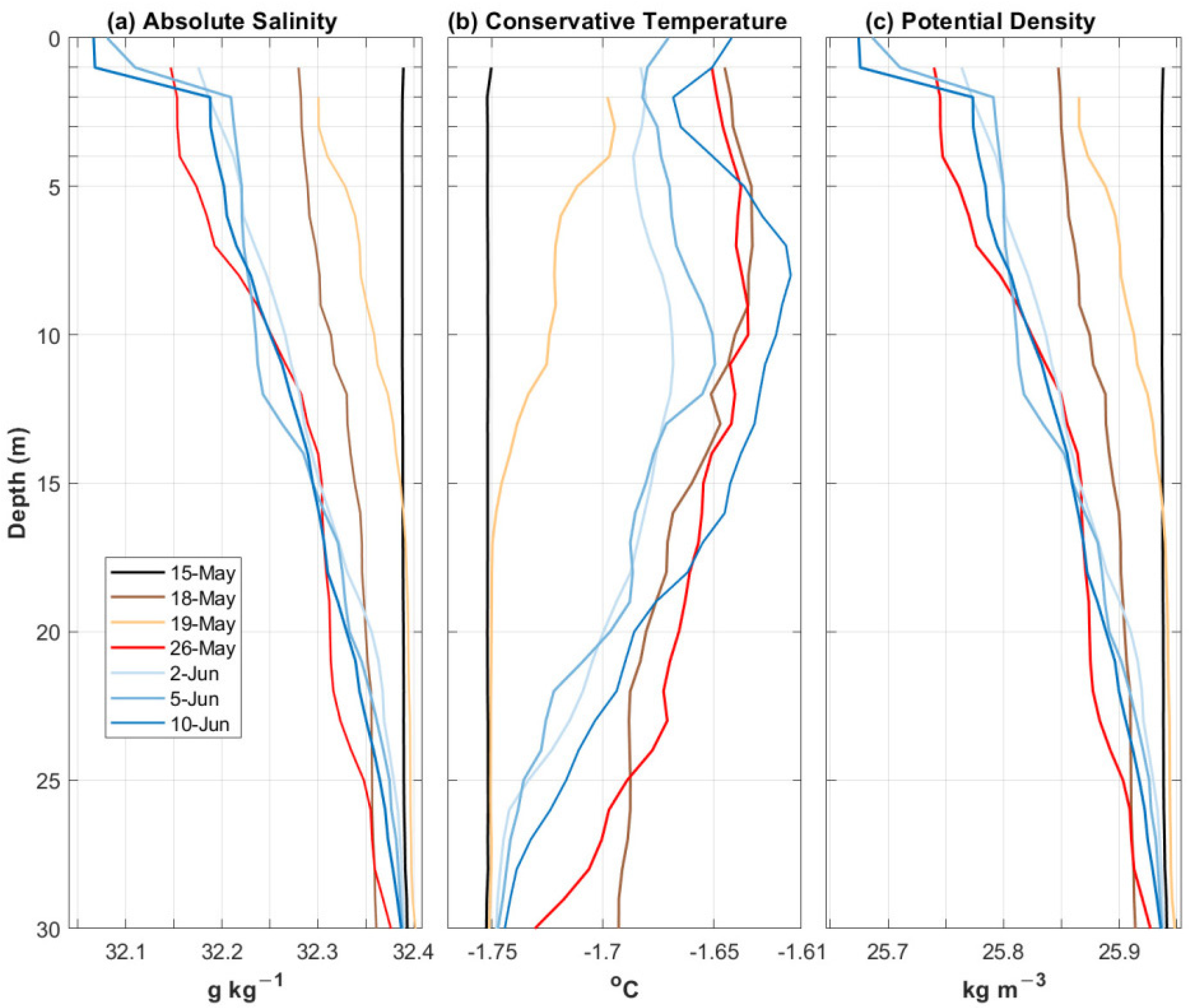

3.1.1. Discrete CTD Profile Measurements

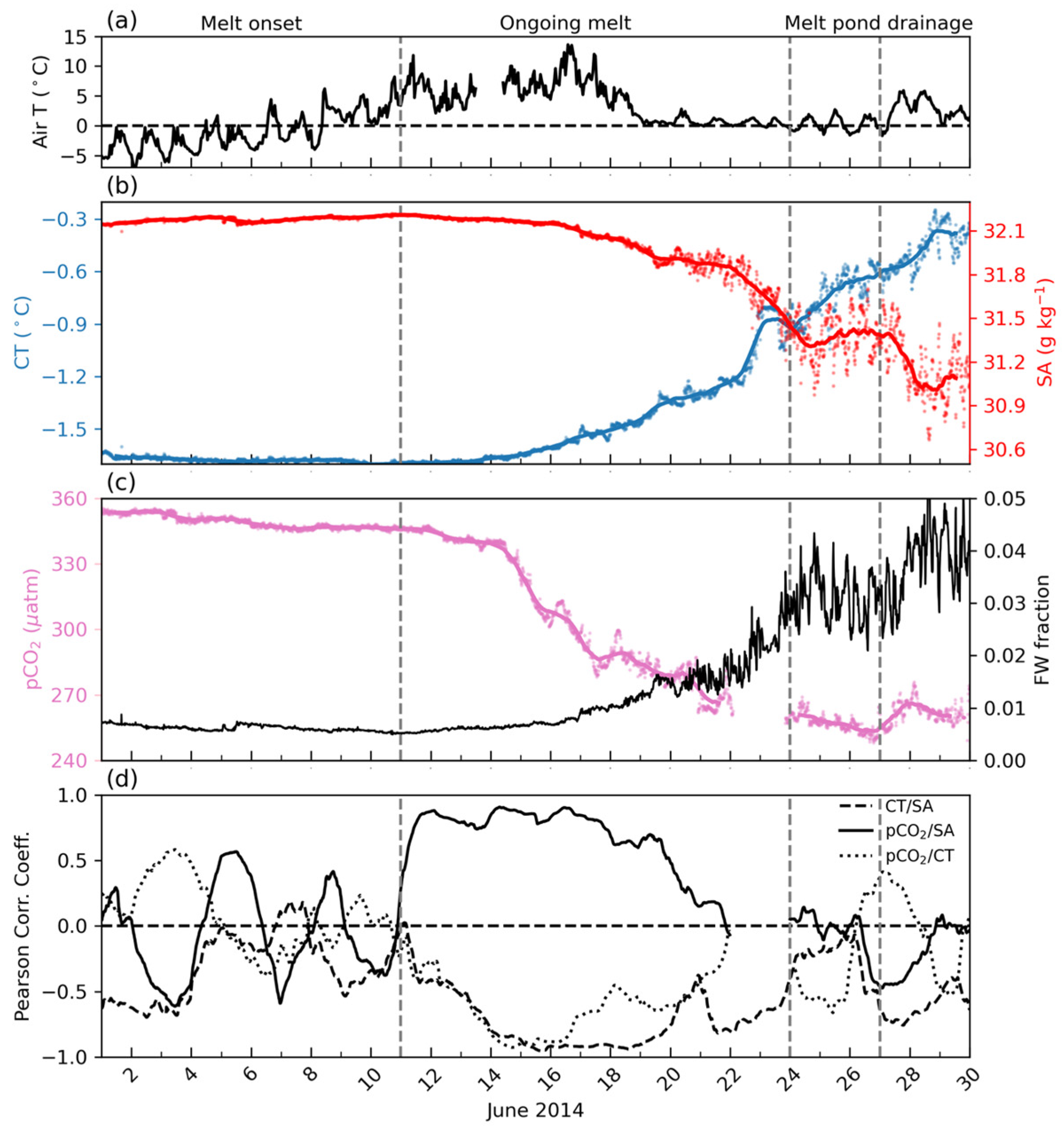

3.1.2. Continuous Measurements of SA, CT, and pCO2

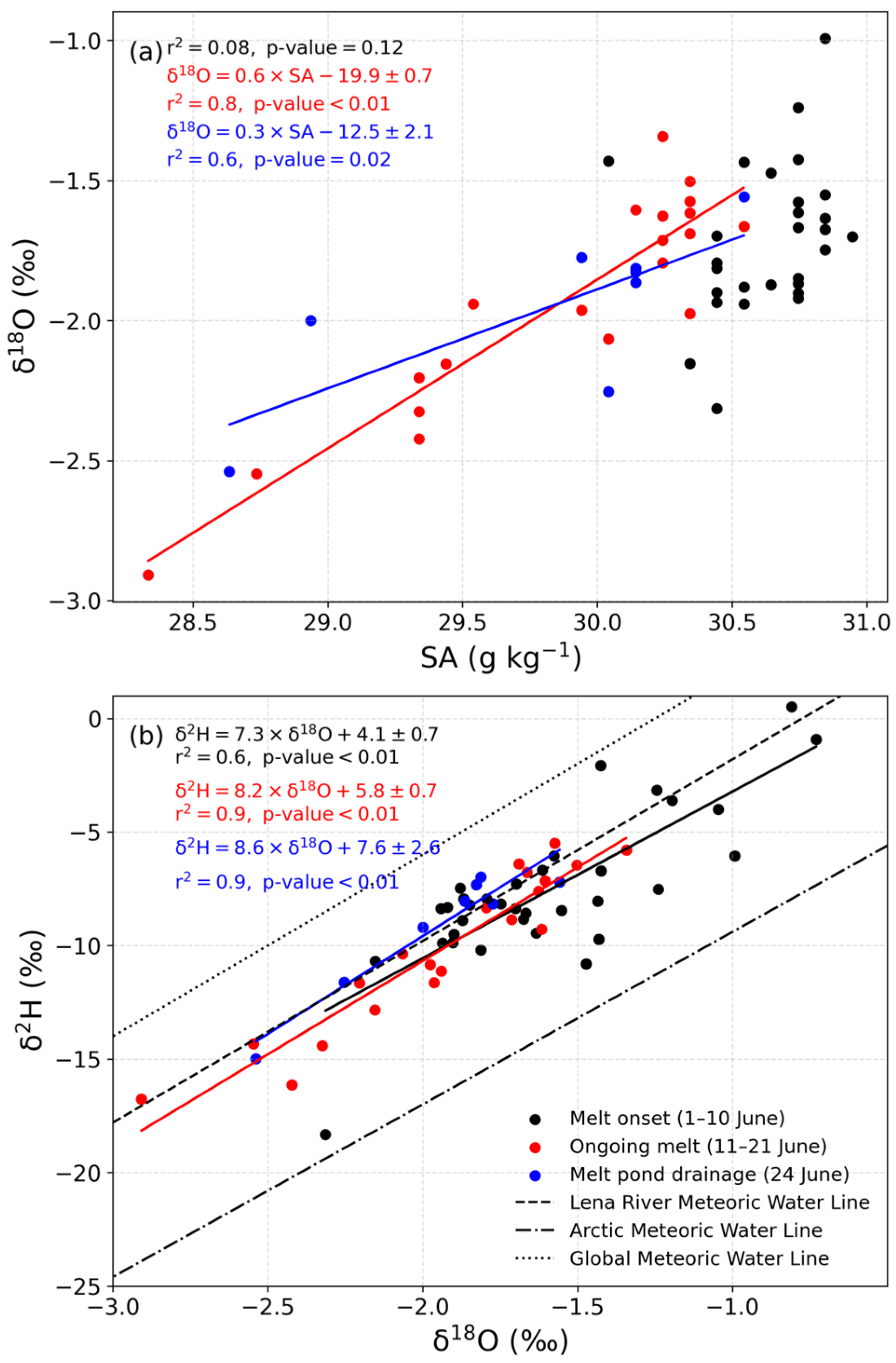

3.1.3. Water Isotopes

3.1.4. Chlorophyll-a and Nitrate Concentrations

3.1.5. Total Alkalinity and Dissolved Inorganic Carbon

3.2. Data Analysis

3.2.1. Calculated pCO2 Based on TA and DIC

3.2.2. Estimates of Fraction of Freshwater

3.2.3. Estimates of pCO2 Uptake by Primary Production

3.2.4. Effects of Snow and Sea Ice Meltwater Mixing on Under-Ice pCO2

3.2.5. Pearson Correlation

4. Results

4.1. Hydrographic Conditions

4.2. Atmospheric Temperature and Snow and Sea Ice Conditions

4.3. Continuous Measurements of SA, CT, and pCO2

4.4. Water Isotopes

4.5. Chlorophyll-a and Nitrate Concentrations

5. Discussion

5.1. Melt Onset Caused a pCO2 Decrease in Under-Ice Seawater

5.2. Snow and Sea Ice Melt Reduce pCO2 in Under-Ice Seawater

5.3. Drainage of Melt Pond Water Affects pCO2 in Under-Ice Seawater

5.4. pCO2 Uptake by PP in Under-Ice Seawater

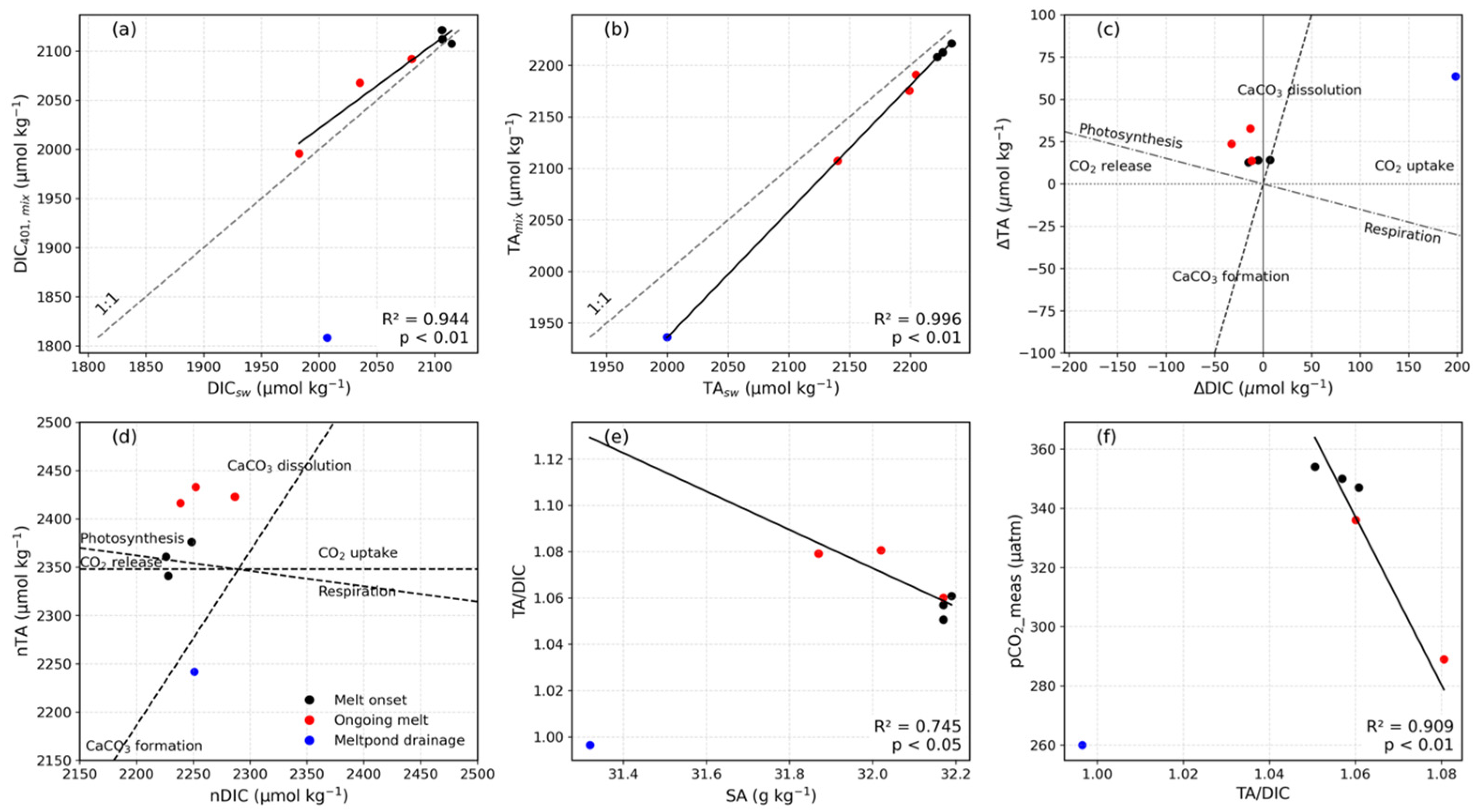

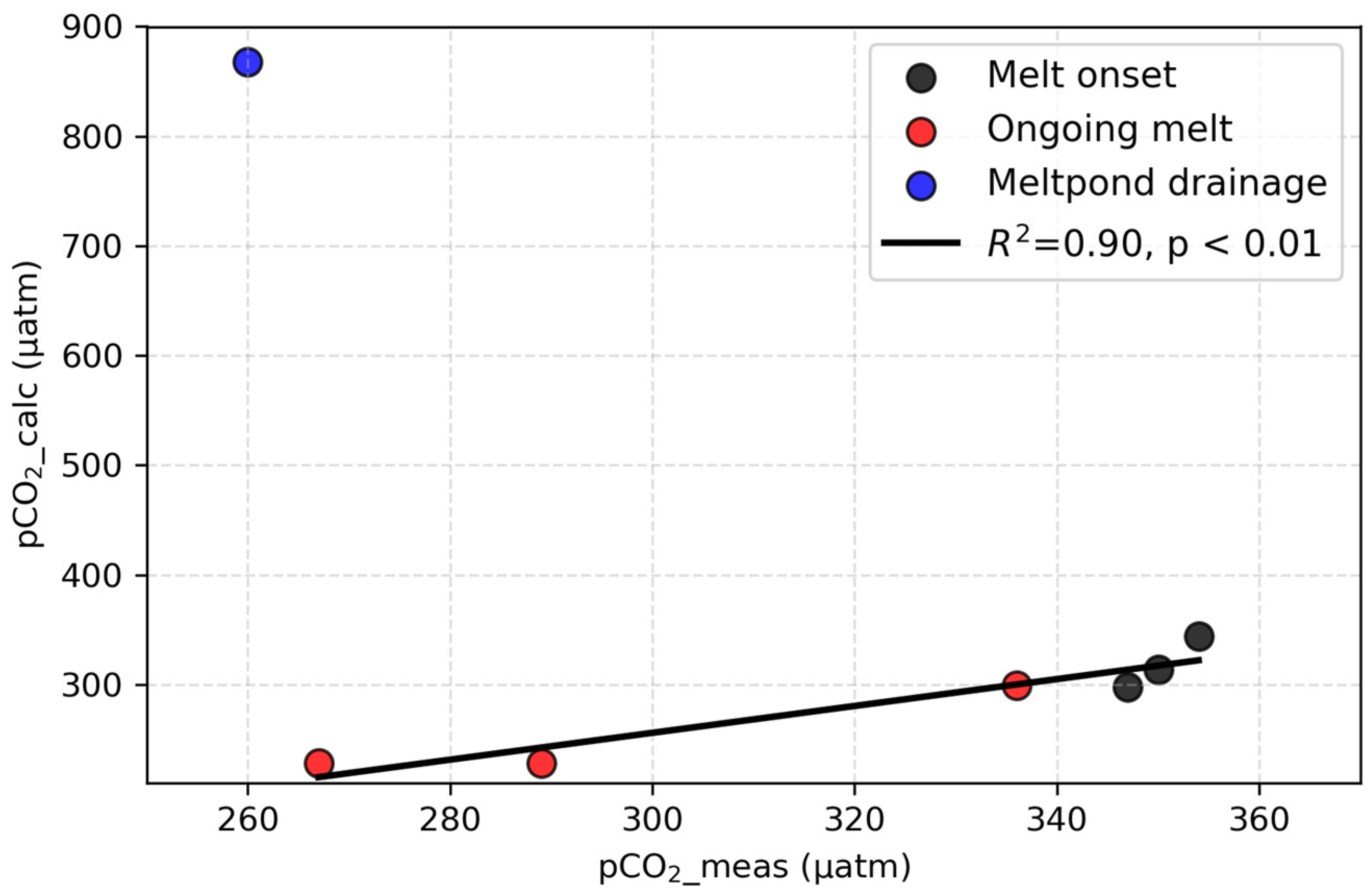

5.5. Comparison Between Measured and Calculated pCO2 in the Under-Ice Seawater

6. Conclusions

- This study provides data on the few continuous, high-resolution measurements of pCO2 in under-ice seawater, capturing the transition from melt onset to melt pond drainage in Young Sound-Tyrolerfjord, Northeast Greenland.

- We demonstrated that dilution from mixing with meltwater from snow and sea ice was the primary driver of the observed pCO2 decline in the under-ice seawater.

- The subsequent drainage of melt ponds through the ice as the melting season progressed marked the onset of the connection between the atmosphere and the under-ice seawater despite persistent snow and sea ice cover.

- This connection establishes pathways for gas exchange between the atmosphere and under-ice seawater, even before sea ice breakup.

- Primary production played a secondary role in this pCO2 reduction, compared to dilution from snow and sea ice melt.

- High-frequency under-ice pCO2 measurements enabled us to capture rapid variability and revealed systematic discrepancies between measured and calculated pCO2, pointing to limitations of relying solely on calculated values in sea ice-influenced coastal waters.

- Our findings enhance the understanding of how meltwater influences surface-water pCO2 dynamics in Arctic coastal waters and highlight their importance for predicting the future oceanic uptake of atmospheric CO2 under continued sea ice decline.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| YS | Young Sound-Tyrolerfjord |

| CTD | Conductivity–Temperature–Depth profiler |

| TEOS-10 | Thermodynamic Equation of Seawater (2010) |

| CO2SYS | Carbonate system calculation program |

| GEM | Greenland Ecosystem Monitoring |

| DMI | Danish Meteorological Institute |

| SA | Absolute Salinity |

| CT | Conservative Temperature |

| TA | Total Alkalinity |

| DIC | Dissolved Inorganic Carbon |

| pCO2 | Partial pressure of CO2 |

| pCO2_meas | Measured pCO2 (from CONTROS HydroC® CO2) |

| pCO2_calc | Calculated pCO2 (from CO2SYS) |

| nTA, nDIC | Salinity-normalized TA and DIC |

| ΔDIC, ΔTA | Residuals |

| DIC401,mix | DIC consistent with fixed pCO2 = 401 under mixing assumptions |

| SAmix, CTmix, TAmix, DICmix, pCO2mix | Conservative-mixing expectations for SA, CT, TA, DIC, pCO2 |

| TA/DIC | Total Alkalinity to DIC ratio |

| Sref | Reference salinity |

| ffw | Freshwater fraction |

| LT | Layer thickness |

| PP | Primary production |

| DICpp | DIC uptake attributable to PP |

| Chl-a | Chlorophyll-a |

| NO3− | Nitrate |

| CaCO3 | Calcium carbonate |

| δ18O, δ2H | Oxygen-18 and Deuterium isotope composition |

| VSMOW2 | Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water 2 |

| SLAP2 | Standard Light Antarctic Precipitation 2 |

| AMWL | Arctic Meteoric Water Line |

| GMWL | Global Meteoric Water Line |

| LRMWL | Lena River Meteoric Water Line |

References

- Perovich, D.K.; Meier, W.; Tschudi, M.; Farrell, S.; Hendricks, S.; Gerland, S.; Kaleschke, L.; Ricker, R.; Tian-Kunze, X.; Webster, M.; et al. Sea Ice. Arctic Report Card 2019; Richter-Menge, J., Druckenmiller, M.L., Jeffries, M., Eds.; NOAA Communications: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Stroeve, J.; Notz, D. Changing State of Arctic Sea Ice across All Seasons. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 103001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocquet, M.; Fleury, S.; Rémy, F.; Piras, F. Arctic and Antarctic Sea Ice Thickness and Volume Changes from Observations Between 1994 and 2023. J. Geophys. Res Ocean. 2024, 129, e2023JC020848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renner, A.H.H.; Gerland, S.; Haas, C.; Spreen, G.; Beckers, J.F.; Hansen, E.; Nicolaus, M.; Goodwin, H. Evidence of Arctic Sea Ice Thinning from Direct Observations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2014, 41, 5029–5036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serreze, M.C.; Holland, M.M.; Stroeve, J. Perspectives on the Arctic’s Shrinking Sea-Ice Cover. Science 2007, 315, 1533–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, R.; Rothrock, D.A. Decline in Arctic Sea Ice Thickness from Submarine and ICESat Records: 1958–2008. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2009, 36, L15501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perovich, D.; Meier, W.; Tschudi, M.; Hendricks, S.; Petty, A.A.; Divine, D.; Farrell, S.; Gerland, S.; Haas, C.; Kaleschke, L.; et al. Sea Ice. Available online: https://arctic.noaa.gov/Report-Card/Report-Card-2020/ArtMID/7975/ArticleID/891/Sea-Ice (accessed on 25 December 2020).

- Meier, W.N.; Petty, A.; Hendricks, S.; Perovich, D.; Farrell, S.; Webster, M.; Divine, D.; Gerland, S.; Kaleschke, L.; Ricker, R.; et al. Sea Ice. Arctic Report Card 2022; Druckenmiller, M.L., Thoman, R.L., Moon, T.A., Eds.; NOAA IR: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kwok, R. Arctic Sea Ice Thickness, Volume, and Multiyear Ice Coverage: Losses and Coupled Variability (1958–2018). Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 105005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreen, G.; Steur, L.; Divine, D.; Gerland, S.; Hansen, E.; Kwok, R. Arctic Sea Ice Volume Export Through Fram Strait From 1992 to 2014. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2020, 125, e2019JC016039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslanik, J.; Stroeve, J.; Fowler, C.; Emery, W. Distribution and Trends in Arctic Sea Ice Age through Spring 2011. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2011, 38, L13502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutgers van der Loeff, M.M.; Cassar, N.; Nicolaus, M.; Rabe, B.; Stimac, I. The Influence of Sea Ice Cover on Air-Sea Gas Exchange Estimated with Radon-222 Profiles. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2014, 119, 2735–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGrandpre, M.; Evans, W.; Timmermans, M.L.; Krishfield, R.; Williams, B.; Steele, M. Changes in the Arctic Ocean Carbon Cycle with Diminishing Ice Cover. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2020, 47, e2020GL088051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaus, M.; Katlein, C.; Maslanik, J.; Hendricks, S. Changes in Arctic Sea Ice Result in Increasing Light Transmittance and Absorption. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2012, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katlein, C.; Arndt, S.; Nicolaus, M.; Perovich, D.K.; Jakuba, M.V.; Suman, S.; Elliott, S.; Whitcomb, L.L.; McFarland, C.J.; Gerdes, R.; et al. Influence of Ice Thickness and Surface Properties on Light Transmission through Arctic Sea Ice. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2015, 120, 5932–5944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arrigo, K.R.; Perovich, D.K.; Pickart, R.S.; Brown, Z.W.; Van Dijken, G.L.; Lowry, K.E.; Mills, M.M.; Palmer, M.A.; Balch, W.M.; Bahr, F.; et al. Massive Phytoplankton Blooms Under Arctic Sea Ice. Science 2012, 336, 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heng, S.; Zhongyong, G.; Liqi, C.; Fan, Z. Distributions of Dissolved Inorganic Carbon and Total Alkalinity in the Western Arctic Ocean. Adv. Polar. Sci. 2011, 22, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meire, L.; Søgaard, D.H.; Mortensen, J.; Meysman, F.J.R.; Soetaert, K.; Arendt, K.E.; Juul-Pedersen, T.; Blicher, M.E.; Rysgaard, S. Glacial Meltwater and Primary Production Are Drivers of Strong CO2 Uptake in Fjord and Coastal Waters Adjacent to the Greenland Ice Sheet. Biogeosciences 2015, 12, 2347–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Gao, X.; Lin, H.; Ouyang, Z.; Cai, W.; Chen, L.; Qi, D. The Impact of Sea Ice Melt on the Evolution of Surface PCO2 in a Polar Ocean Basin. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1307295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudels, B.; Carmack, E. Arctic Ocean Water Mass Structure and Circulation. Oceanography 2022, 35, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duke, P.J.; Else, B.G.T.; Jones, S.F.; Marriot, S.; Ahmed, M.M.M.; Nandan, V.; Butterworth, B.; Gonski, S.F.; Dewey, R.; Sastri, A.; et al. Seasonal Marine Carbon System Processes in an Arctic Coastal Landfast Sea Ice Environment Observed with an Innovative Underwater Sensor Platform. Elementa 2021, 9, 00103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rysgaard, S.; Glud, R.N.; Sejr, M.K.; Bendtsen, J.; Christensen, P.B. Inorganic Carbon Transport during Sea Ice Growth and Decay: A Carbon Pump in Polar Seas. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2007, 112, C03016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericson, Y.; Falck, E.; Chierici, M.; Fransson, A.; Kristiansen, S.; Platt, S.M.; Hermansen, O.; Myhre, C.L. Temporal Variability in Surface Water PCO2 in Adventfjorden (West Spitsbergen) with Emphasis on Physical and Biogeochemical Drivers. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2018, 123, 4888–4905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geilfus, N.-X.; Delille, B.; Tison, J.-L.; Lemes, M.; Rysgaard, S. Gas Dynamics within Landfast Sea Ice of an Arctic Fjord (NE Greenland) during the Spring–Summer Transition. Elem. Sci. Anth. 2023, 11, 00056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rysgaard, S.; Glud, R.N.; Lennert, K.; Cooper, M.; Halden, N.; Leakey, R.J.G.; Hawthorne, F.C.; Barber, D. Ikaite Crystals in Melting Sea Ice–Implications for PCO2 and PH Levels in Arctic Surface Waters. Cryosphere 2012, 6, 901–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowry, K.E.; Pickart, R.S.; Selz, V.; Mills, M.M.; Pacini, A.; Lewis, K.M.; Joy-Warren, H.L.; Nobre, C.; van Dijken, G.L.; Grondin, P.L.; et al. Under-Ice Phytoplankton Blooms Inhibited by Spring Convective Mixing in Refreezing Leads. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2018, 123, 90–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geilfus, N.X.; Galley, R.J.; Crabeck, O.; Papakyriakou, T.; Landy, J.; Tison, J.L.; Rysgaard, S. Inorganic Carbon Dynamics of Melt-Pond-Covered First-Year Sea Ice in the Canadian Arctic. Biogeosciences 2015, 12, 2047–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polashenski, C.; Perovich, D.; Courville, Z. The Mechanisms of Sea Ice Melt Pond Formation and Evolution. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2012, 117, C01001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, D.C.; Alin, S.R.; Aramaki, T.; Barbero, L.; Bates, N.; Gkritzalis, T.; Jones, S.D.; Kozyr, A.; Lauvset, S.K.; Macovei, V.A.; et al. Surface Ocean CO2 Atlas Database Version 2025 (SOCATv2025) (NCEI Accession 0304549); NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information: Asheville, NC, USA, 2025.

- Gattuso, J.-P.; Alliouane, S.; Fischer, P. High-Frequency, Year-Round Time Series of the Carbonate Chemistry in a High-Arctic Fjord (Svalbard). Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2023, 15, 2809–2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rysgaard, S.; Vang, T.; Stjernholm, M.; Rasmussen, B.; Windelin, A.; Kiilsholm, S. Physical Conditions, Carbon Transport, and Climate Change Impacts in a Northeast Greenland Fjord. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 2003, 35, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendtsen, J.; Gustafsson, K.E.; Rysgaard, S.; Vang, T. Physical conditions, dynamics and model simulations during the ice-free period of the Young Sound/Tyrolerfjord system. In Carbon Cycling in Arctic Marine Ecosystems: Case Study Young Sound; Rysgaard, S., Glud, R.N., Eds.; Meddelelser om Grønland; Bioscience: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2007; Volume 58, pp. 46–59. [Google Scholar]

- Mernild, S.H.; Sigsgaard, C.; Rasch, M.; Hasholt, B.; Hansen, B.U.; Stjernholm, M.; Pedersen, D. Climate, river discharge and suspended sediment transport in the Zackenberg River drainage basin and Young Sound/Tyrolerfjord, Northeast Greenland. In Carbon Cycling in Arctic Marine Ecosystems: Case Study Young Sound; Rysgaard, S., Glud, R.N., Eds.; Meddr. Grønland; Bioscience: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2007; pp. 24–43. [Google Scholar]

- McDougall, T.J.; Barker, P.M. Getting Started with TEOS-10 and the Gibbs Seawater (GSW) Oceanographic Toolbox; SCOR/IAPSO: Paris, France, 2011; 28p. [Google Scholar]

- Fietzek, P.; Fiedler, B.; Steinhoff, T.; Körtzinger, A. In Situ Quality Assessment of a Novel Underwater PCO2 Sensor Based on Membrane Equilibration and NDIR Spectrometry. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2014, 31, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauch, D.; Schlosser, P.; Fairbanks, R.G. Fresh-Water Balance and the Sources of Deep and Bottom Waters in the Arctic-Ocean Inferred from the Distribution of (H20)-O-18. Prog. Oceanogr. 1995, 35, 53–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauch, D.; Hölemann, J.; Andersen, N.; Dobrotina, E.; Nikulina, A.; Kassens, H. The Arctic Shelf Regions as a Source of Freshwater and Brine-Enriched Waters as Revealed from Stable Oxygen Isotopes. Polarforschung 2010, 80, 127–140. [Google Scholar]

- Ekwurzel, B.; Schlosser, P.; Mortlock, R.A.; Fairbanks, R.G.; Swift, J.H. River Runoff, Sea Ice Meltwater, and Pacific Water Distribution and Mean Residence Times in the Arctic Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2001, 106, 9075–9092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laukert, G.; Bauch, D.; Rabe, B.; Krumpen, T.; Damm, E.; Kienast, M.; Hathorne, E.; Vredenborg, M.; Tippenhauer, S.; Andersen, N.; et al. Dynamic Ice–Ocean Pathways along the Transpolar Drift Amplify the Dispersal of Siberian Matter. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, G.J.; Wilkinson, B. Spatial Distribution of Δ18O in Meteoric Precipitation. Geology 2002, 30, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Gibson, J.J.; Cooper, L.W.; Hélie, J.F.; Birks, S.J.; McClelland, J.W.; Holmes, R.M.; Peterson, B.J. Isotopic Signals (18O, 2H, 3H) of Six Major Rivers Draining the Pan-Arctic Watershed. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2012, 26, GB1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, H. Isotopic Variations in Meteoric Waters. Science 1961, 133, 1702–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grasshoff, K.; Kremling, K.; Ehrhardt, M. Methods of Seawater Analysis, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; ISBN 9783527613984. [Google Scholar]

- Redfield, A.C. The Biological Control of Chemical Factors in the Environment; Sigma Xi, The Scientific Research Honor Society: Durham, NC, USA, 1958; Volume 46, pp. 205–221. [Google Scholar]

- Gran, G. Determination of the Equivalence Point in Potentiometric Titrations. Part II. Analyst 1952, 77, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierrot, D.; Lewis, E.; Wallace, D.W.R. MS Excel Program Developed for CO2 System Calculations. CO2Sys_v2.1.Xls; Oak Ridge National Laboratory: Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 2006.

- Mehrbach, C.; Culberson, C.H.; Hawley, J.E.; Pytkowicx, R.M. Measurement of the Apparent Dissociation Constants of Carbonic Acid in Seawater at Atmospheric Pressure. Limnol. Ocean. 1973, 18, 897–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, A.G.; Millero, F.J. A Comparison of the Equilibrium Constants for the Dissociation of Carbonic Acid in Seawater Media. Deep. Sea Res. Part A. Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 1987, 34, 1733–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Cai, W.J.; Chen, L. The Marine Carbonate System of the Arctic Ocean: Assessment of Internal Consistency and Sampling Considerations, Summer 2010. Mar. Chem. 2015, 176, 174–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woosley, R.J.; Millero, F.J.; Takahashi, T. Internal Consistency of the Inorganic Carbon System in the Arctic Ocean. Limnol. Ocean. Methods 2017, 15, 887–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rysgaard, S.; Gissel Nielsen, T.; Winding Hansen, B. Seasonal Variation in Nutrients, Pelagic Primary Production and Grazing in a High-Arctic Coastal Marine Ecosystem, Young Sound, Northeast Greenland. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1999, 179, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toole, J.M.; Timmermans, M.L.; Perovich, D.K.; Krishfield, R.A.; Proshutinsky, A.; Richter-Menge, J.A. Influences of the Ocean Surface Mixed Layer and Thermohaline Stratification on Arctic Sea Ice in the Central Canada Basin. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2010, 115, C10018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J.M.; Williams, W.J.; Carmack, E.C. Winter Sea-Ice Melt in the Canada Basin, Arctic Ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2012, 39, L03603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, A.; Fer, I.; Sundfjord, A.; Peterson, A.K. Mixing Rates and Vertical Heat Fluxes North of Svalbard from Arctic Winter to Spring. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2017, 122, 4569–4586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, Z.; Koläs, E.H.; Fer, I. Structure and Drivers of Ocean Mixing North of Svalbard in Summer and Fall 2018. Ocean. Sci. 2021, 17, 365–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friis, K.; Körtzinger, A.; Wallace, D.W.R. The Salinity Normalization of Marine Inorganic Carbon Chemistry Data. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2003, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, K.M.; Eicken, H.; Heaton, A.L.; Miner, J.; Pringle, D.J.; Zhu, J. Thermal Evolution of Permeability and Microstructure in Sea Ice. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2007, 34, L16501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Delille, B.; Eicken, H.; Vancoppenolle, M.; Brabant, F.; Carnat, G.; Geilfus, N.; Papakyriakou, T.; Heinesch, B.; Tison, J. Physical and Biogeochemical Properties in Landfast Sea Ice (Barrow, Alaska): Insights on Brine and Gas Dynamics across Seasons. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2013, 118, 3172–3189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, M.; Nomura, D.; Webb, A.L.; Li, Y.; Dall’osto, M.; Schmidt, K.; Droste, E.S.; Chamberlain, E.J.; Posman, K.M.; Angot, H.; et al. Melt Pond CO2 Dynamics and Fluxes with the Atmosphere in the Central Arctic Ocean during the Summer-to-Autumn Transition. Elem. Sci. Anth. 2025, 13, 00023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perovich, D.K.; Grenfell, T.C.; Light, B.; Hobbs, P.V. Seasonal Evolution of the Albedo of Multiyear Arctic Sea Ice. J. Geophys. Res. 2002, 107, 8044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardyna, M.; Mundy, C.J.; Mayot, N.; Matthes, L.C.; Oziel, L.; Horvat, C.; Leu, E.; Assmy, P.; Hill, V.; Matrai, P.A.; et al. Under-Ice Phytoplankton Blooms: Shedding Light on the “Invisible” Part of Arctic Primary Production. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 608032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrigo, K.R.; Perovich, D.K.; Pickart, R.S.; Brown, Z.W.; van Dijken, G.L.; Lowry, K.E.; Mills, M.M.; Palmer, M.A.; Balch, W.M.; Bates, N.R.; et al. Phytoplankton Blooms beneath the Sea Ice in the Chukchi Sea. Deep Sea Res. 2 Top. Stud. Ocean. 2014, 105, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meire, L.; Paulsen, M.L.; Meire, P.; Rysgaard, S.; Hopwood, M.J.; Sejr, M.K.; Stuart-Lee, A.; Sabbe, K.; Stock, W.; Mortensen, J. Glacier Retreat Alters Downstream Fjord Ecosystem Structure and Function in Greenland. Nat. Geosci. 2023, 16, 671–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krisch, S.; Browning, T.J.; Graeve, M.; Ludwichowski, K.U.; Lodeiro, P.; Hopwood, M.J.; Roig, S.; Yong, J.C.; Kanzow, T.; Achterberg, E.P. The Influence of Arctic Fe and Atlantic Fixed N on Summertime Primary Production in Fram Strait, North Greenland Sea. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuerena, R.E.; Hopkins, J.; Buchanan, P.J.; Ganeshram, R.S.; Norman, L.; von Appen, W.J.; Tagliabue, A.; Doncila, A.; Graeve, M.; Ludwichowski, K.U.; et al. An Arctic Strait of Two Halves: The Changing Dynamics of Nutrient Uptake and Limitation Across the Fram Strait. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2021, 35, 15230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assur, A. Composition of Sea Ice and Its Tensile Strength; Engineer Research and Development Center: Vicksburg, MS, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Verdugo, J.; Ruiz-Castillo, E.; Rysgaard, S.; Wieter, B.; Papakyriakou, T.; Geilfus, N.-X.; Sørensen, L.L. Continuous Measurements of PCO2 in Under-Ice Seawater during the Onset of Sea Ice Melt in Young Sound, Northeast Greenland, in 2014 [Dataset]. Panagea 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geilfus, N.-X. Young Sound 2014 [Dataset]. HydroShare 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rysgaard, S.; Boone, W.; Kirillov, S.A.; Dmitrenko, I.; Ruiz-Castillo, E. CTD Data Collected in the Period April-June 2014 in Young Sound, Greenland. Pangaea 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Freshwater Source | Measured δ18O (‰) | δ18O at SA = 0 (‰) |

|---|---|---|

| Snow meltwater | −19.1 a | −19.9 |

| Melt pond water | −13.6 b | −12.5 |

| Date (2014) | Chl-a (µg L−1) | NO3− (μmol L−1) |

|---|---|---|

| 11 June | 0.01 | 2.20 |

| 17 June | 0.66 | 0.00 |

| 23 June | 0.12 | 0.00 |

| Source | SA | CT | TA | DIC | pH | pCO2_Calc e | pCO2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (g kg−1) | (°C) | (µmol kg−1) | (µmol kg−1) | (NBS) | (µatm) | (µatm) | |

| Surface water a | 32.2 | −1.7 | 2222 | 2114 | 344 | ||

| Deeper water b | 32.3 | −1.7 | 2217 | 2119 | 370 | ||

| Zack. River c | 0 | 0.2 | 280 | 447 e | 6.6 | 2174 | |

| Snow Meltwater d | 0 | 0 | 52 | 44 | 1 | ||

| Sea ice Meltwater d | 4.8 | −1.7 | 378 | 364 | 45 | ||

| Atmosphere | 401 |

| Scenario | Lw (m) | Li e (m) | SAmix a (g kg−1) | CTmix a (°C) | TAmix a (µmol kg−1) | DICmix a (µmol kg−1) | pCO2mix b (µatm) | ∆pCO2 c (µatm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Snow meltwater mixed with seawater | 2.5 | 0.36 | 28.1 | −1.5 | 1949 | 1853 | 285 | 59 |

| Sea ice meltwater mixed with seawater | 2.5 | 0.1 | 31.1 | −1.7 | 2151 | 2047 | 320 | 24 |

| River water mixed with seawater d | 31.6 | −1.7 | 2183 | 2081 | 342 | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Verdugo, J.; Ruiz-Castillo, E.; Rysgaard, S.; Boone, W.; Papakyriakou, T.; Geilfus, N.-X.; Sørensen, L.L. Snow and Sea Ice Melt Enhance Under-Ice pCO2 Undersaturation in Arctic Waters. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2257. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122257

Verdugo J, Ruiz-Castillo E, Rysgaard S, Boone W, Papakyriakou T, Geilfus N-X, Sørensen LL. Snow and Sea Ice Melt Enhance Under-Ice pCO2 Undersaturation in Arctic Waters. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(12):2257. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122257

Chicago/Turabian StyleVerdugo, Josefa, Eugenio Ruiz-Castillo, Søren Rysgaard, Wieter Boone, Tim Papakyriakou, Nicolas-Xavier Geilfus, and Lise Lotte Sørensen. 2025. "Snow and Sea Ice Melt Enhance Under-Ice pCO2 Undersaturation in Arctic Waters" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 12: 2257. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122257

APA StyleVerdugo, J., Ruiz-Castillo, E., Rysgaard, S., Boone, W., Papakyriakou, T., Geilfus, N.-X., & Sørensen, L. L. (2025). Snow and Sea Ice Melt Enhance Under-Ice pCO2 Undersaturation in Arctic Waters. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(12), 2257. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122257