Fixed-Time Event-Triggered Fault-Tolerant Formation Control for Autonomous Underwater Vehicle Swarms

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (i)

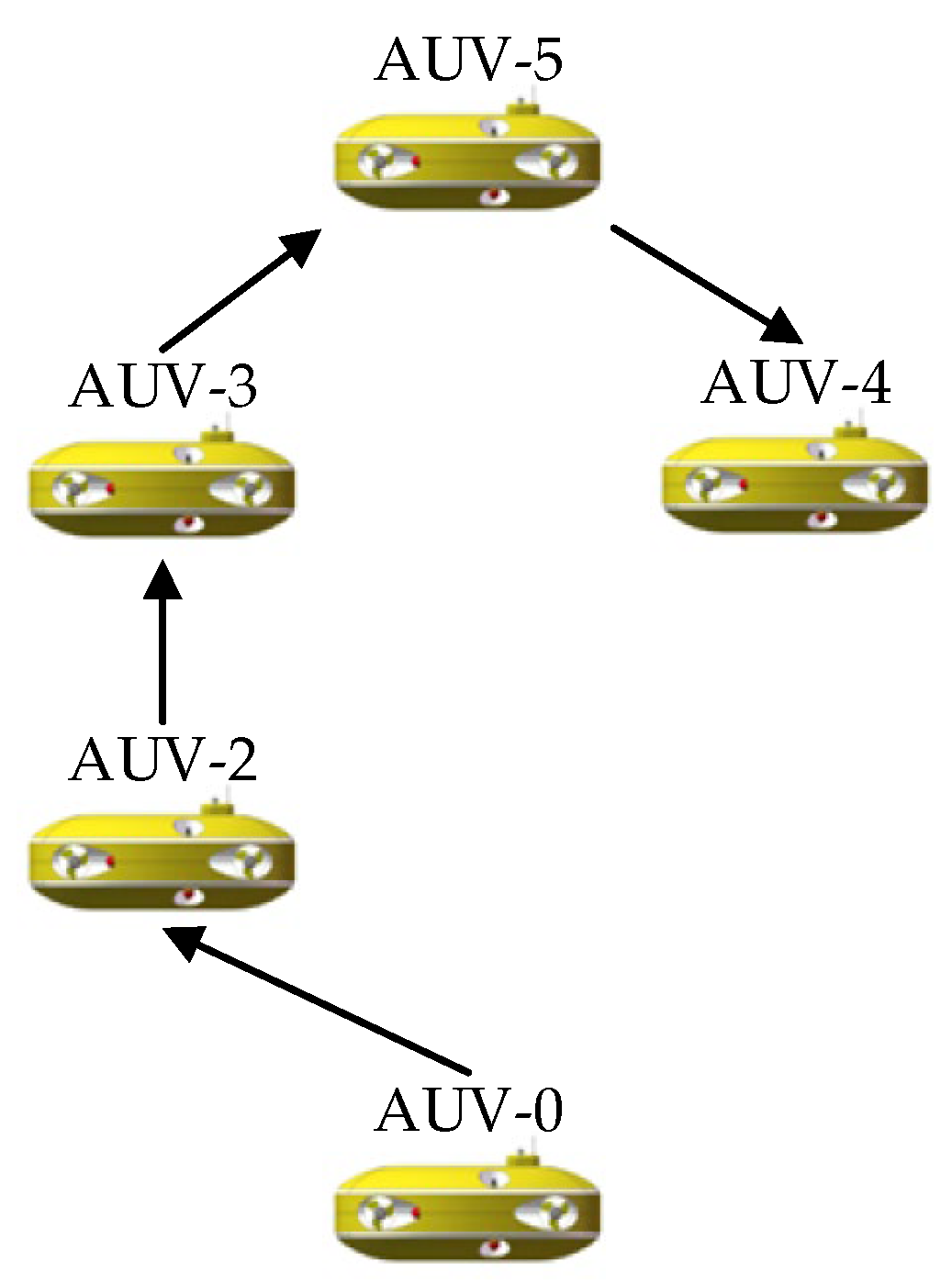

- A fault-tolerant control mechanism for multiple AUVs is proposed to address formation task failures caused by communication topology disruptions. The Prim algorithm is employed to reconstruct the communication topology after failures, while the Hungarian algorithm is used to solve the position assignment problem for formation transformation.

- (ii)

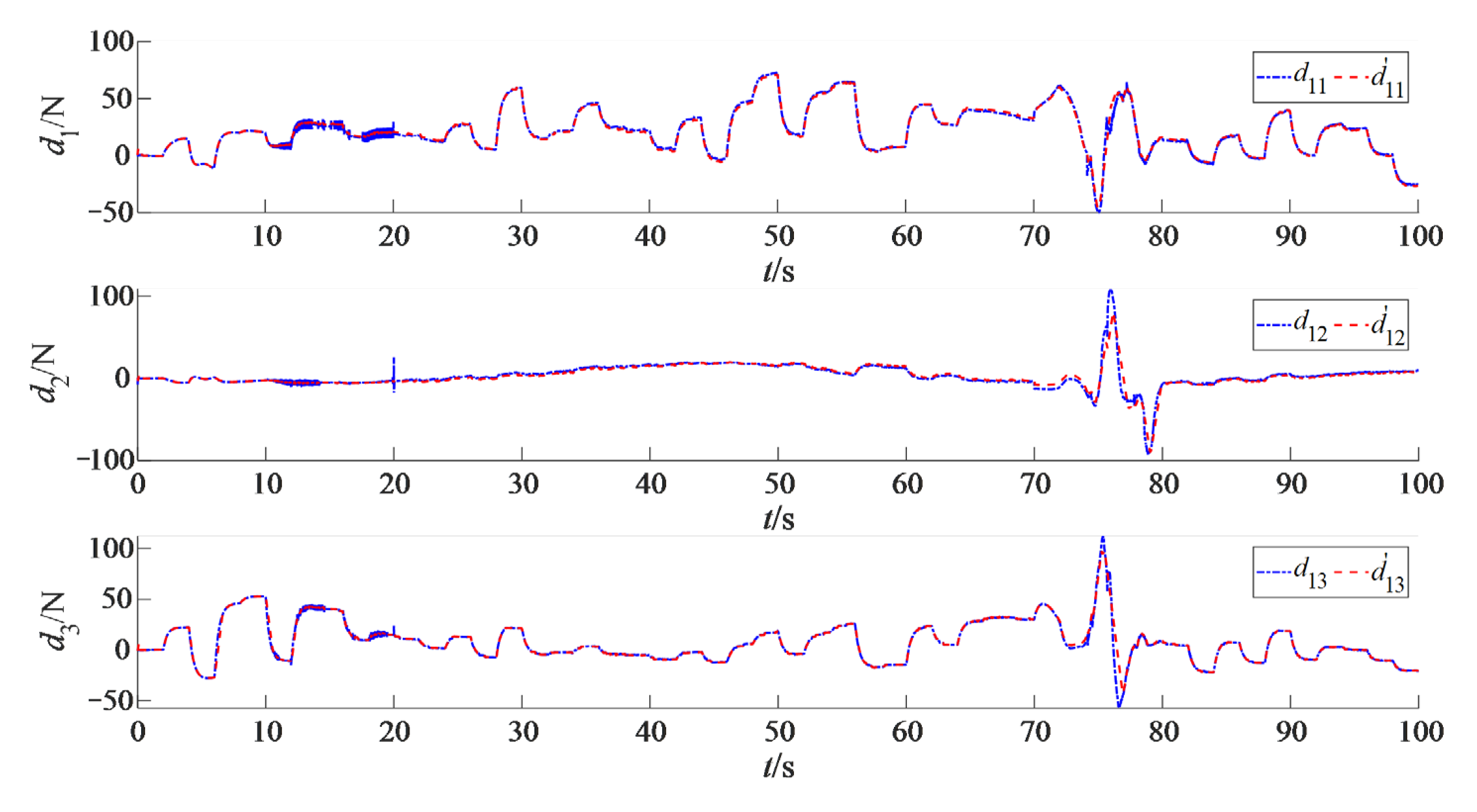

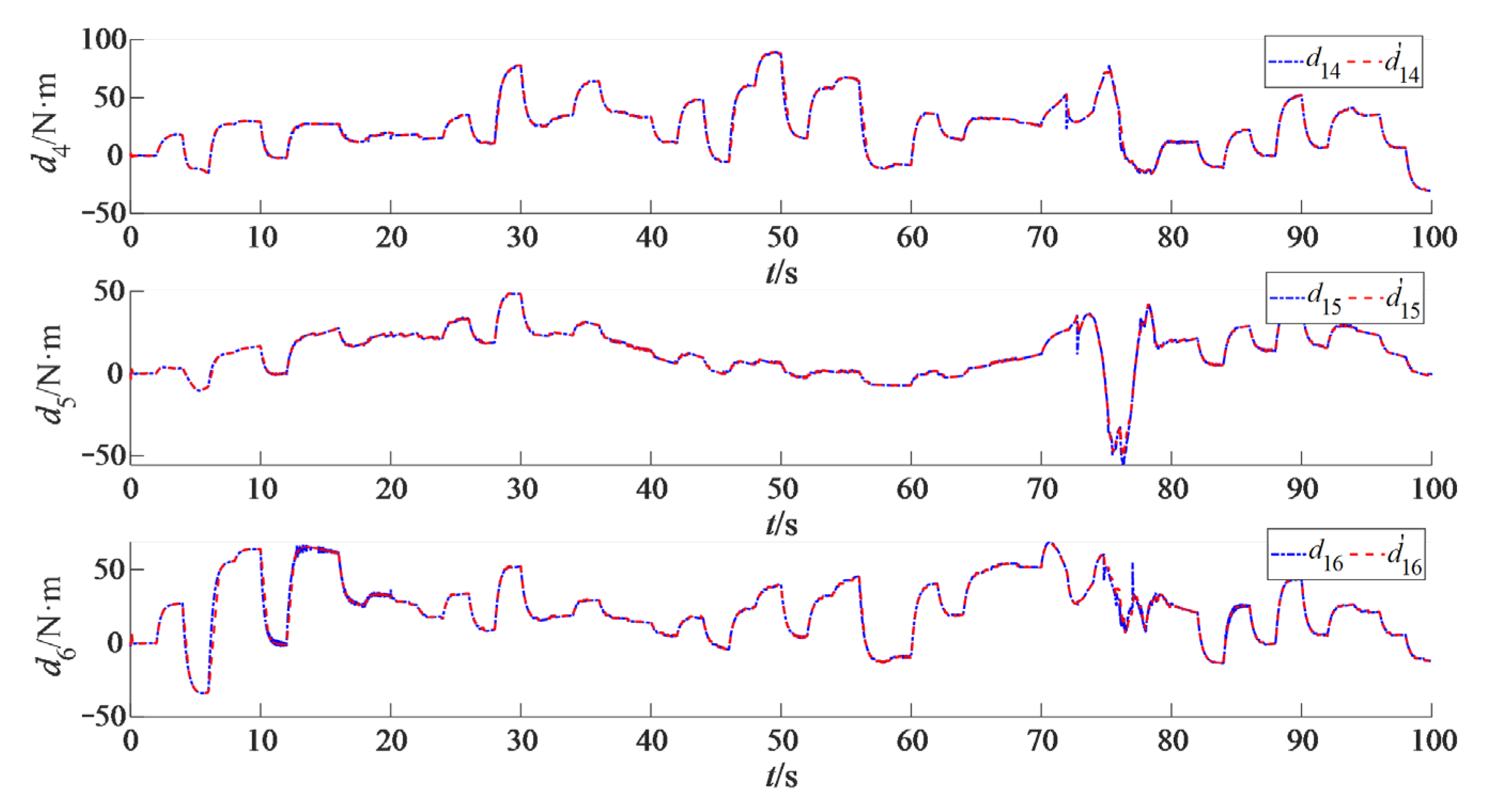

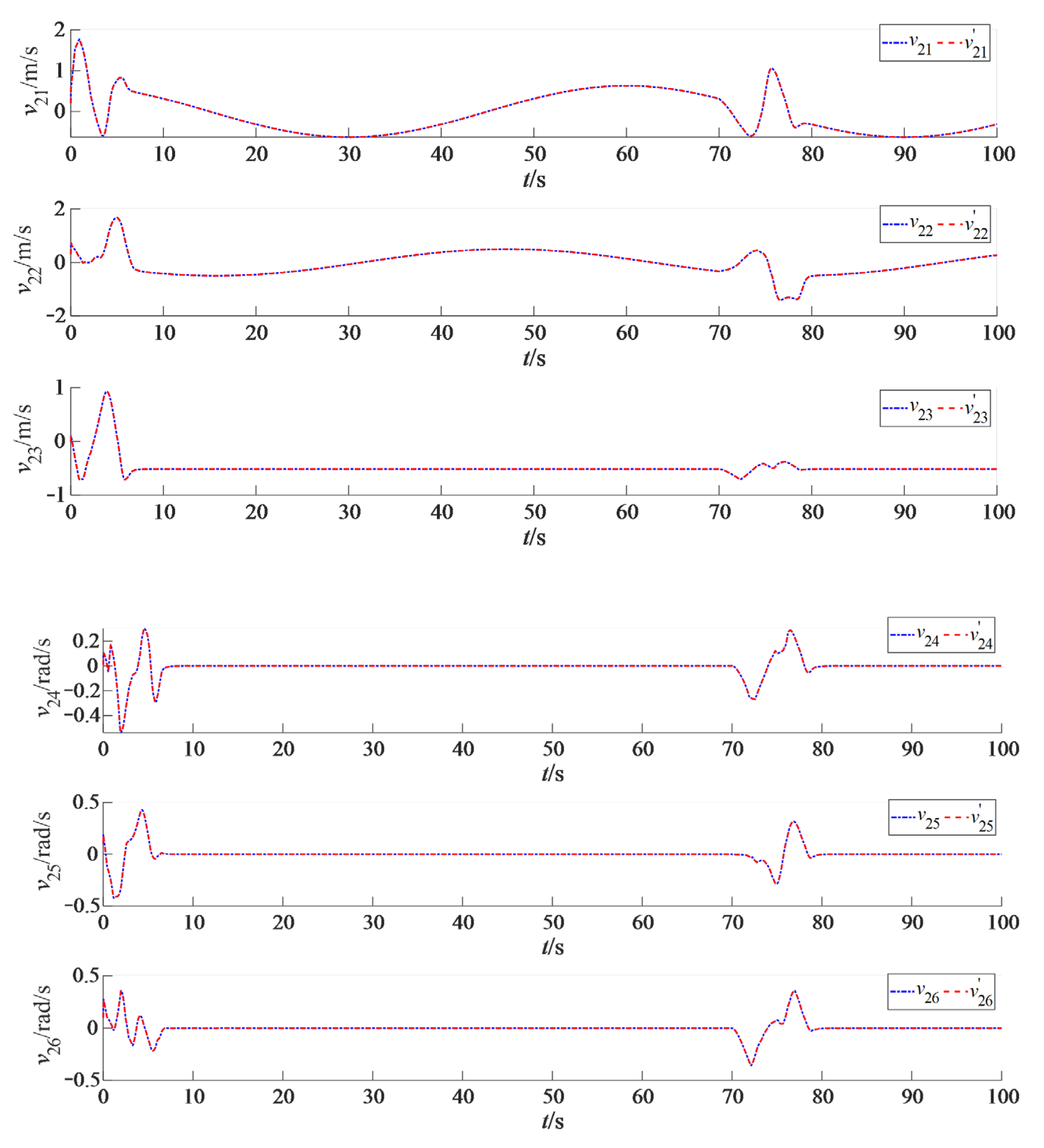

- To account for actuator failures within AUVs, a fixed-time extended state observer (ESO) is designed to accurately estimate velocity and observe lumped disturbances, including model uncertainties, unknown ocean disturbances, and actuator failures. This enhances the robustness against external and internal disturbances.

- (iii)

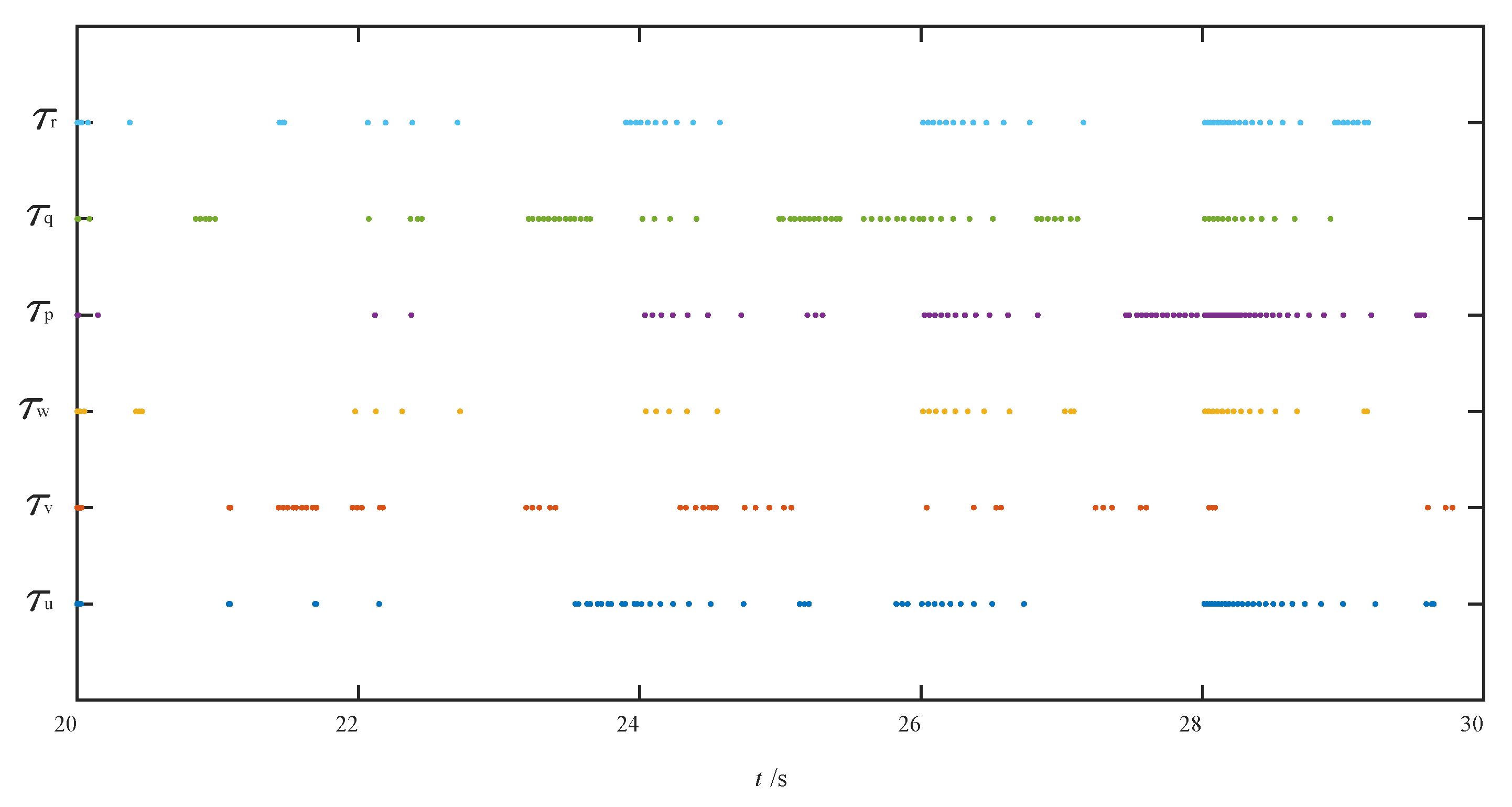

- Based on a performance function, the tracking error is reconstructed into error variables, forming a novel terminal sliding mode surface with these error variables. An auxiliary saturation system and event-triggered mechanism are integrated into the control design, leading to a fixed-time event-triggered formation control law and the stability of the closed-loop system is proved. This approach ensures compliance with error constraints, maintains system stability, and reduces the frequency of controller updates, thereby improving computational efficiency.

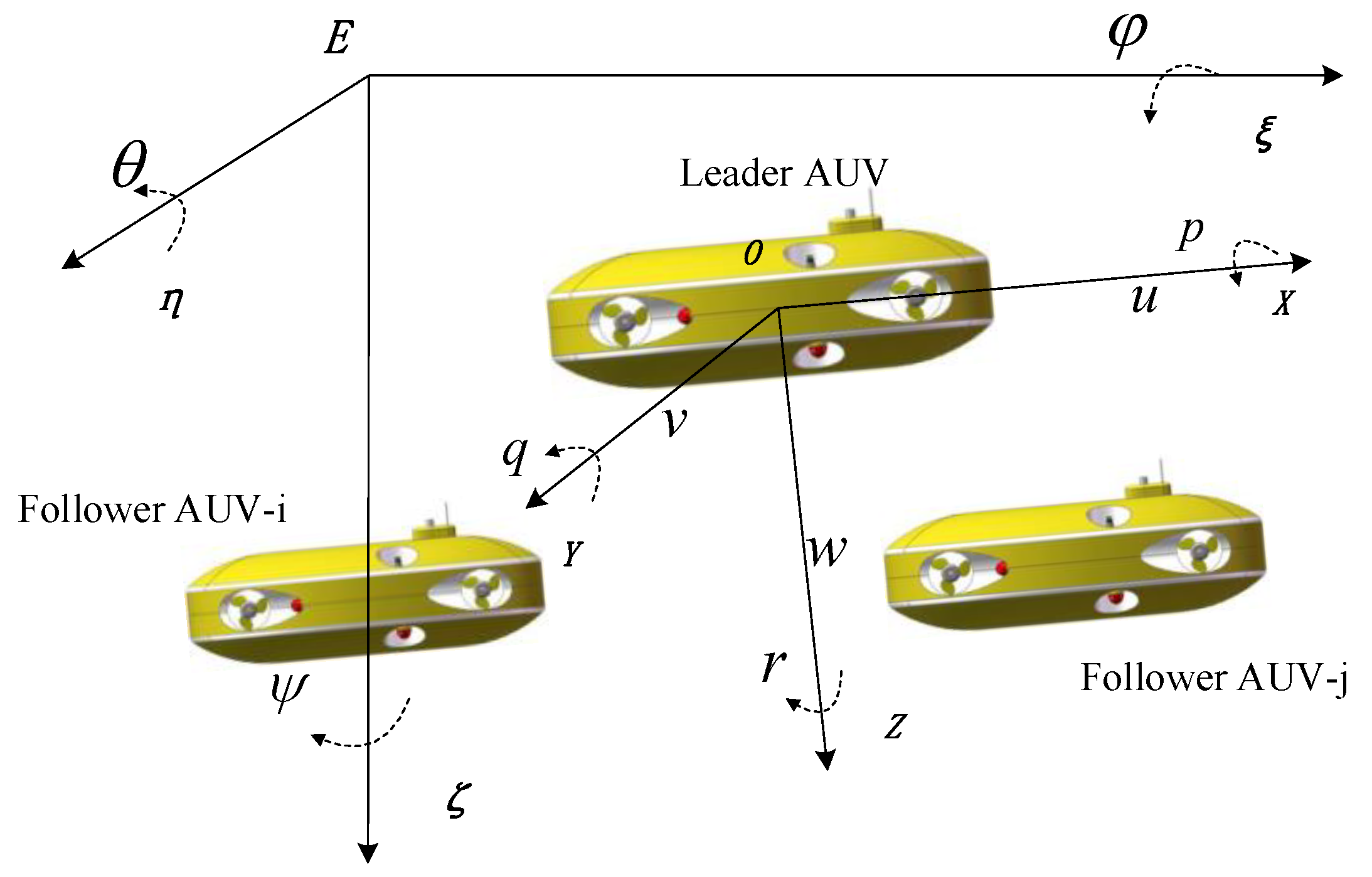

2. Problem Formulation

2.1. Dynamic Models

2.2. Lemma and Assumption

- (1)

- ;

- (2)

- Any solution satisfies the inequality: .Then the system is globally fixed-time stable, and , , , are constant. , , and satisfies the inequality

- (3)

- Any solution satisfies the inequality:When , , the system is practically fixed-time stable, and satisfies the inequality:

3. Fault-Tolerant Control of Multiple AUVs for Fixed-Time Formation

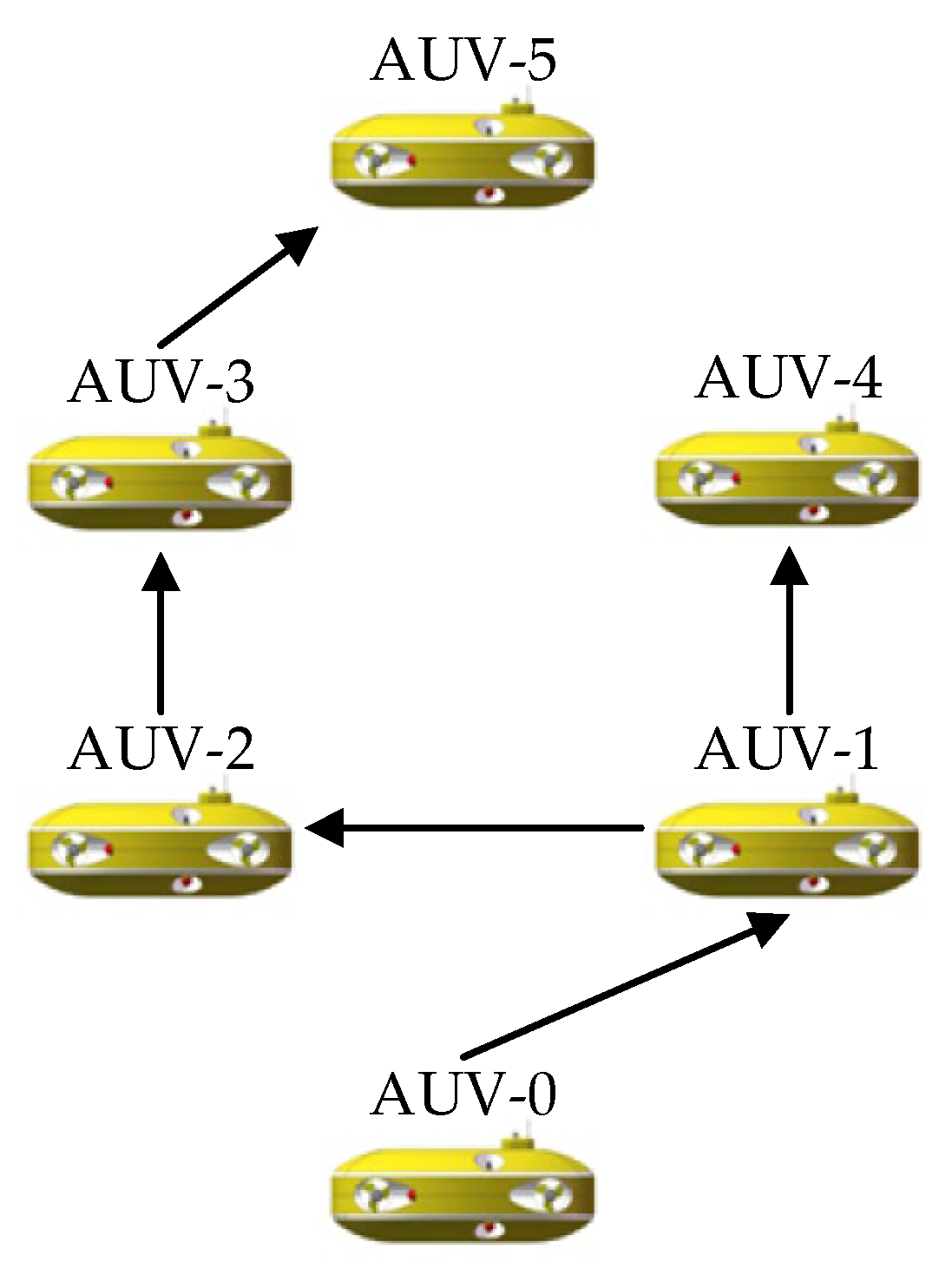

3.1. The Formation Reconfiguration Scheme Considering Communication Topology Failure

3.1.1. The Multi-AUV Communication Topology Reconstruction Method Based on the Prim Algorithm

| Algorithm 1 The Multi-AUV Topology Reconstruction Process Based on Prim Algorithm |

| Input: : the set of AUVs and E: the edges of graph w: weight function for the edges of AUV communication distance Output: Minimum spanning tree (T). T← ∅ Initialize the minimum spanning tree U ← {v0} Start from an arbitrary vertex v0 while |U| < |V| do Select edge (u, v) ∈ E such that u ∈ U, v ∉ U and w(u, v) is minimum Add edge (u, v) to T Add vertex v to U end while return T |

3.1.2. The Formation Position Allocation Method Based on the Hungarian Algorithm

| Algorithm 2 The Formation Transition Position Allocation Based on Hungarian Algorithm |

| Input: AUV matrix of size Output: Optimal assignment matrix Step 1: Subtract the row minimum from each row for i from 1 to n: row_minimums = for j from 1 to m: for j from 1 to m: column_minimums = for i from 1 to n: Step 2: Cover all zeros with a minimum number of lines while True://Find a zero in the matrix for i from 1 to n: for j from 1 to m: if cost_matrix[i][j] = 0 and not cover_rows[i] = True and not cover_cols[j] = True: break if zero is found: break if all columns are covered: break Step 3: Create a new zero if necessary and find the smallest uncovered value for i from 1 to n: for j from 1 to m: if not cover_rows[i] and not cover_cols[j]: min_uncovered = min(min_uncovered, cost_matrix[i][j]) //Subtract the smallest uncovered value from all uncovered elements for i from 1 to n: for j from 1 to m: if not cover_rows[i] and not cover_cols[j]: cost_matrix[i][j] −= min_uncovered elif cover_rows[i] and cover_cols[j]: cost_matrix[i][j] + = min_uncovered Step 4: Construct the optimal assignment matrix Back to step 2 until the number of circled zeros equals n return |

3.2. Fixed-Time Extended State Observer

3.3. Controller Design

3.3.1. Controller Design Based on Prescribed Performance

3.3.2. Design of Auxiliary Saturation Systems and Event-Triggered Mechanisms

3.3.3. Stability Analysis and the Exclusion of No Zeno Behavior for Controller

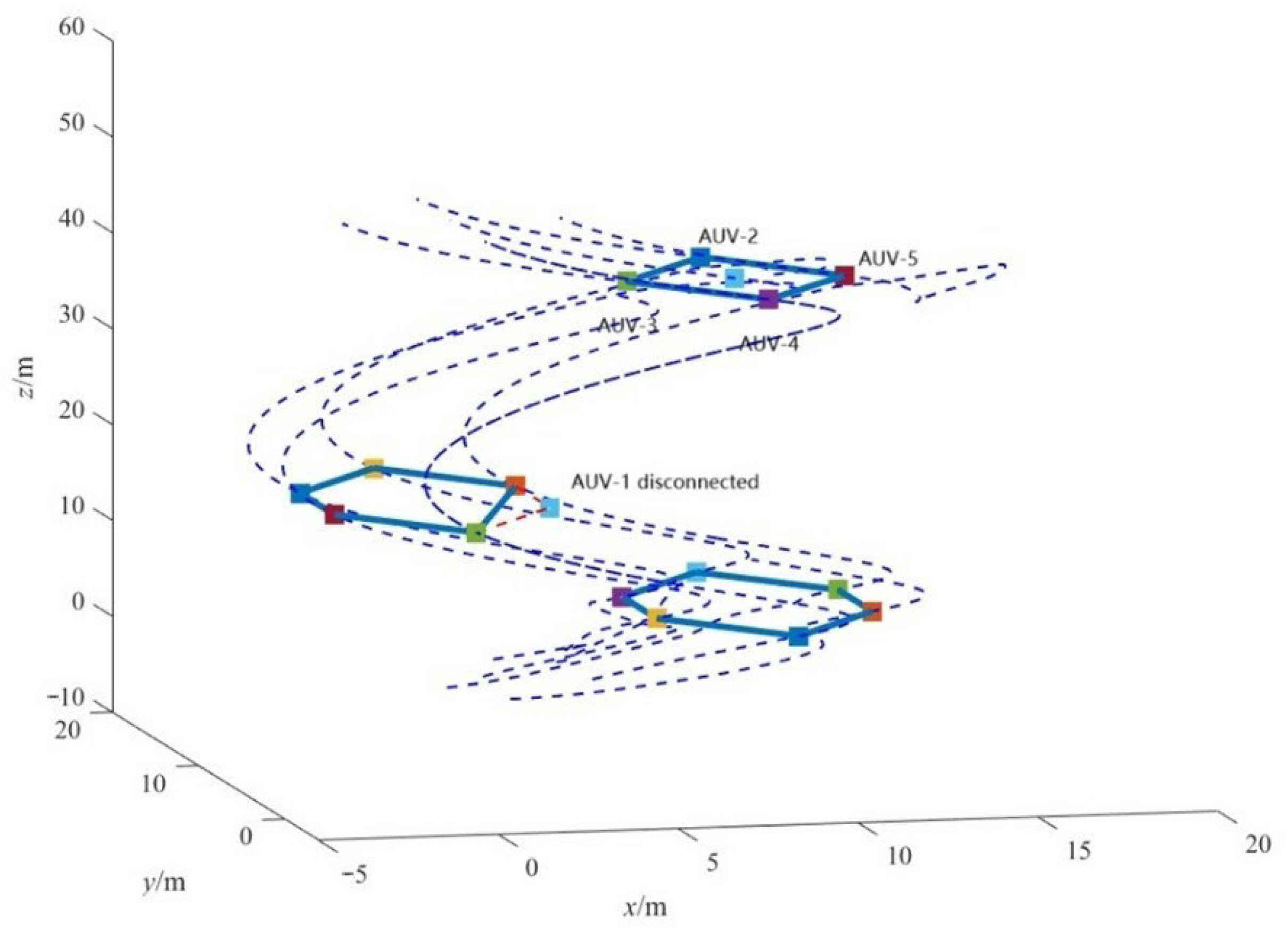

4. Simulation Results

4.1. Simulation Settings

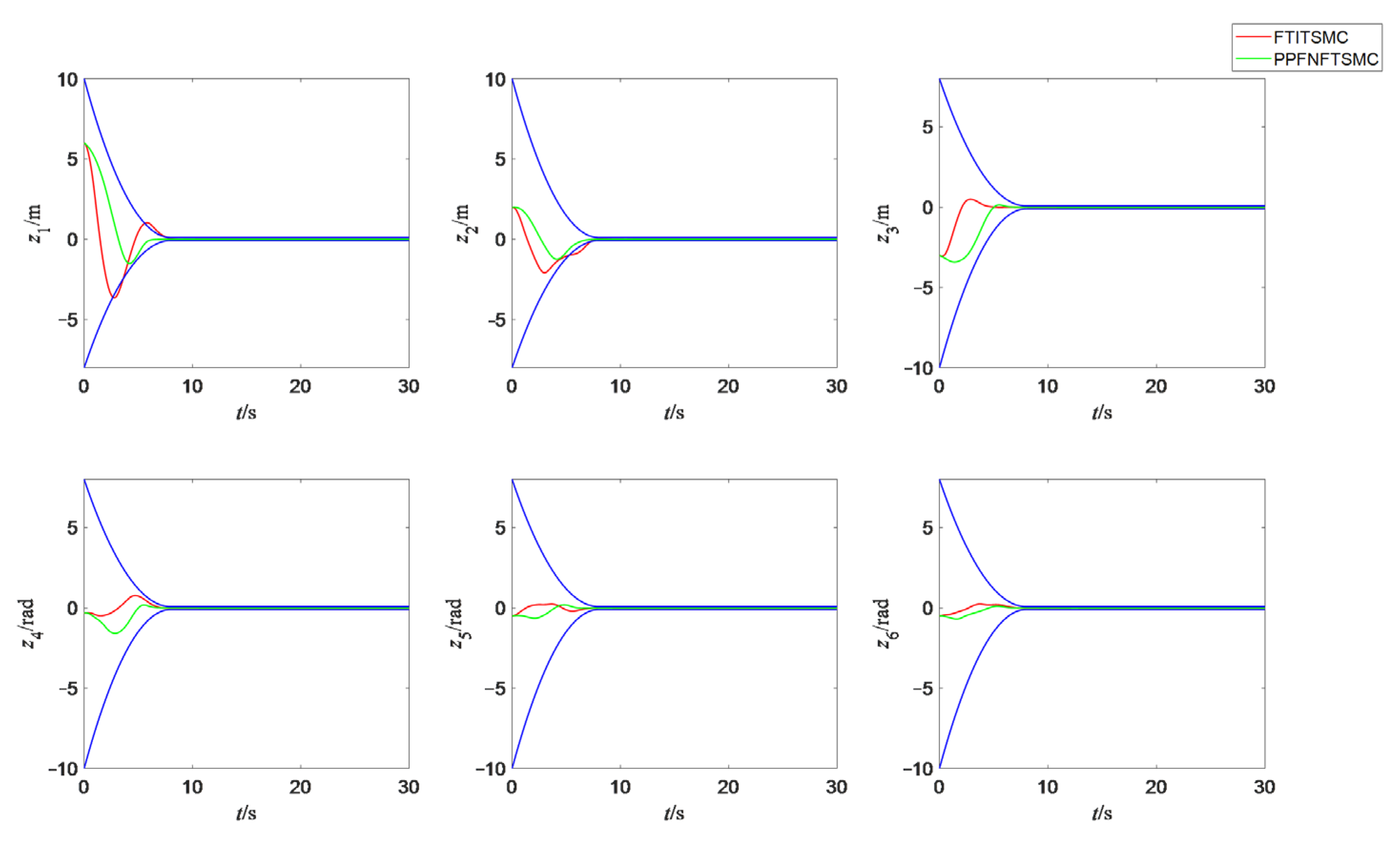

4.2. Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AUV | Autonomous underwater vehicles |

| ESO | Extended state observer |

| PPFNFTSMC | Prescribed performance fixed-time nonsingular fast terminal sliding mode control |

| FTITSMC | Fixed-time integral terminal sliding mode control |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Appendix A.2

Appendix A.3

References

- Chen, Y.; Niu, Q.; Liu, Z.; Huang, B.; Xie, T.; Zhong, L.; Wan, D.; Wang, Z. Failure Modes and Reliability Analysis of Autonomous Underwater Vehicles–A Review. J. Mar. Sci. Appl. 2025, 24, 900–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Jiang, B.; Zhang, Y. Fault-Tolerant Shortest Connection Topology Design for Formation Control. Int. J. Control Autom. Syst. 2014, 12, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamel, M.A.; Yu, X.; Zhang, Y. Fault-tolerant cooperative control of WMRs under actuator faults based on particle swarm optimization. In Proceedings of the 2016 3rd Conference on Control and Fault-Tolerant Systems, Barcelona, Spain, 7–9 September 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zúñiga, B.C.; Mendoza, A.M. PST-Prim Heuristic for the Open Vehicle Routing Problem. IEEE Lat. Am. Trans. 2019, 17, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, W. Formation Control of a Multi-Autonomous Underwater Vehicle Event-Triggered Mechanism Based on the Hungarian Algorithm. Machines 2021, 9, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Zhang, C.; Lin, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, K. Event-triggered-based Fault-tolerant Consensus for AUVs on Heterogeneous Switch Topology. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2022, Hampton Roads, VA, USA, 17–20 October 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Qin, H.; Li, L.; Xue, Y. Fixed-time velocity-free safe formation control of AUVs with actuator saturation and unknown disturbances. Ocean Eng. 2023, 285, 115361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.J.; Qin, H.D.; Li, L.Y. Fixed-time formation control for AUVs with unknown actuator faults based on lumped disturbance observer. Ocean Eng. 2023, 269, 113495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, N.; Hughes, D.; Walters, P.; Schwartz, E.M.; Dixon, W.E. Nonlinear RISE-Based Control of an Autonomous Underwater Vehicle. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2014, 30, 845–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Qin, H.; Ouyang, L.; Jing, R. Predefined-time prescribed performance control for AUV with improved performance function and error transformation. Ocean Eng. 2023, 281, 114817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, C.; Zeng, J. Decentralized formation trajectory tracking control of multi-AUV system with actuator saturation. Ocean Eng. 2022, 255, 111423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Qin, H.; Li, L.; Xue, Y. Adaptive fixed-time fuzzy formation control for multiple AUV systems considering time-varying tracking error constraints and asymmetric actuator saturation. Ocean Eng. 2024, 297, 116936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, J.; Sun, X.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, H.; Liu, W.; Wang, Y. Robust Path-Following Control for AUV under Multiple Uncertainties and Input Saturation. Drones 2023, 7, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, B.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Gao, J. Fixed-time Formation of AUVs with Disturbance via Event-triggered Control. Int. J. Control Autom. Syst. 2021, 19, 1505–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, A.; Qin, H.; Jiang, S. Fixed-Time Average Consensus of a Dynamic Event-Triggered Mechanism in a System of Multiple Underactuated Autonomous Underwater Vehicles Based on a Body Frame Spherical Coordinate System. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Luo, G.; Zhou, H.; Zhao, D. Research on Formation Control Method of Heterogeneous AUV Group under Event-Triggered Mechanism. Mathematics 2022, 10, 1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galdran, A.; Pardo, D.; Picón, A.; Alvarez-Gila, A. Automatic red-channel underwater image restoration. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 2015, 26, 132–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yu, S.; Yan, Y. Fixed-time velocity-free sliding mode tracking control for marine surface vessels with uncertainties and unknown actuator faults. Ocean Eng. 2020, 201, 107107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, G.Z.; Zhuang, G.M.; Lu, J.W. Neural-network-based distributed adaptive synchronization for nonlinear multi-agent systems in pure-feedback form. Neurocomputing 2016, 218, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadhan, Z.; Siahaan, A.P.U.; Mesran, M. Prim and Floyd-Warshall Comparative Algorithms in Shortest Path Problem. In Proceedings of the Joint Workshop KO2PI and the 1st International Conference on Advance & Scientific Innovation, Medan, Indonesia, 23–24 April 2018; ICST (Institute for Computer Sciences, Social-Informatics and Telecommunications Engineering): Brussels, Belgium, 2018; pp. 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhang, L.; Wei, C.; Wu, R.; Cui, N. Fixed-time extended state observer based non-singular fast terminal sliding mode control for a VTVL reusable launch vehicle. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2018, 82–83, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sai, H.; Xu, Z.; Xia, C.; Sun, X. Approximate continuous fixed-time terminal sliding mode control with prescribed performance for uncertain robotic manipulators. Nonlinear Dyn. 2022, 110, 431–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Chen, H.; Sun, Y.; Chen, L. Distributed finite-time fault-tolerant containment control for multiple ocean Bottom Flying node systems with error constraints. Ocean Eng. 2019, 189, 106341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Jin, N.; Chang, S.; Zuo, Z.; Zhao, Z. Fixed-time ESO based fixed-time integral terminal sliding mode controller design for a missile. ISA Trans. 2022, 125, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Jia, Y.M. Fixed-time consensus tracking control for second-order multi-agent systems with bounded input uncertainties via NFFTSM. IET Control Theory Appl. 2017, 11, 2900–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mess (kg) | (Nm·s2) | (Nm·s2) | (Nm·s2) | (Nm·s2) | (Nm·s2) | (Nm·s2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 92 | 49 | 84 | 79 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Coefficients | Linear.Drag/kg·s−1 | Quad.Drag/kg·m−1 | Added Mass/kg |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surge | 21.9 | 24.5 | 40.6 |

| Sway | 47.4 | 34.7 | 82.3 |

| Heave | 53.5 | 40.2 | 114.6 |

| Heel | 71.9 | 42.1 | 55.7 |

| Trim | 97.3 | 48.3 | 76.5 |

| Yaw | 86.9 | 39.3 | 59.1 |

| 10 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 6 | |

| 8 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| 7 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 5 | |

| 0.1 | 0 | 0.005 | 0.01 | 0.005 | |

| 0.1 | 0 | 0.005 | 0.01 | 0.005 | |

| 0.1 | 0 | 0.005 | 0.01 | 0.005 |

| 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

| 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| 0.1 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

| 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

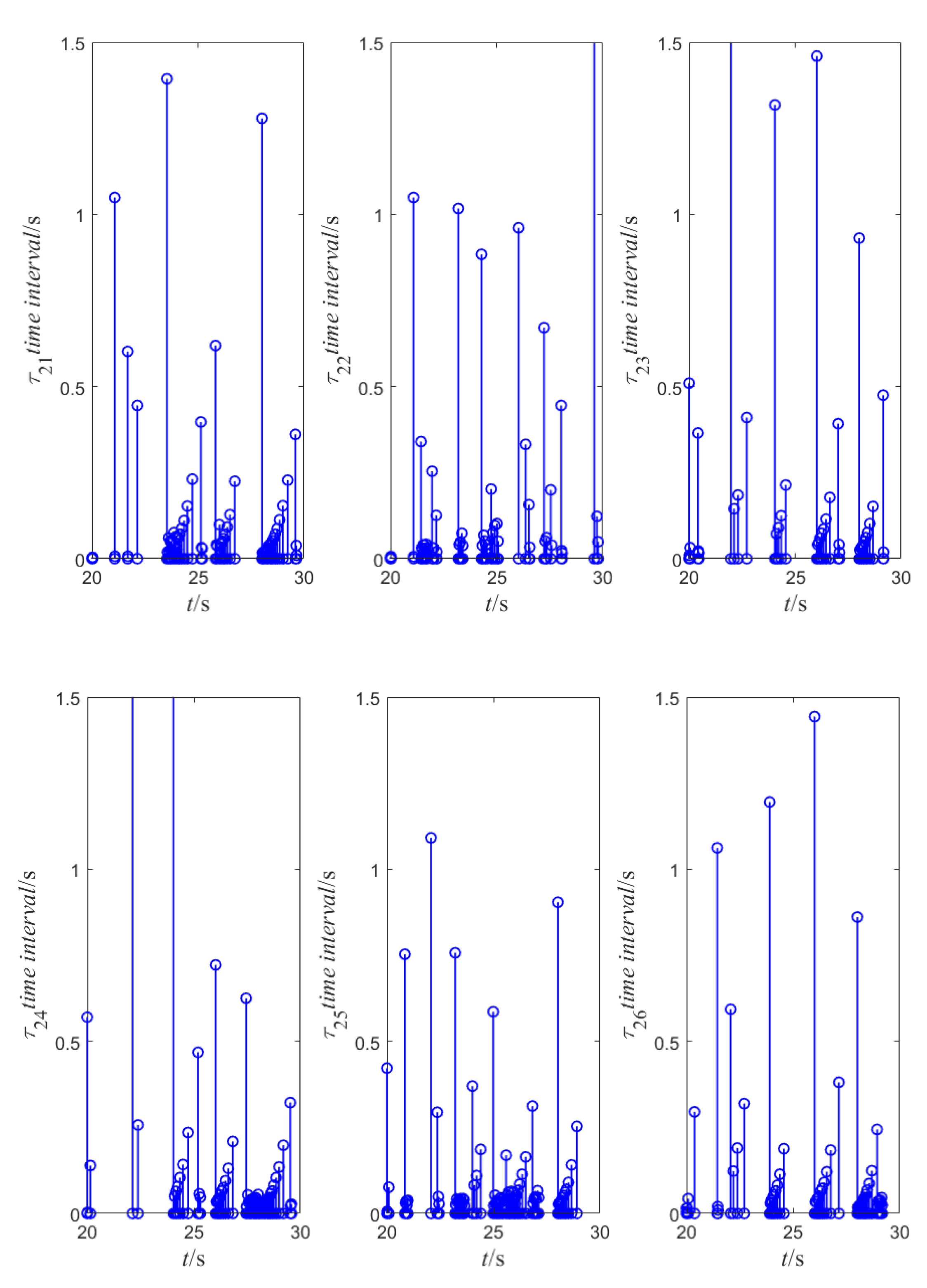

| AUV | Follower AUV-2 | Follower AUV-3 | Follower AUV-4 | Follower AUV-5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trigger Counts | |||||

| 5092 | 5484 | 4158 | 2269 | ||

| 3436 | 4918 | 2894 | 3862 | ||

| 3510 | 5390 | 1762 | 4093 | ||

| 3263 | 3968 | 4099 | 4229 | ||

| 2473 | 3812 | 5287 | 2758 | ||

| 4077 | 5051 | 4797 | 4670 | ||

| No event triggered | 10,000 | 10,000 | 10,000 | 10,000 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Z.; Jiang, S.; Xue, Y.; Mu, X.; Wang, C. Fixed-Time Event-Triggered Fault-Tolerant Formation Control for Autonomous Underwater Vehicle Swarms. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2249. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122249

Wang Z, Jiang S, Xue Y, Mu X, Wang C. Fixed-Time Event-Triggered Fault-Tolerant Formation Control for Autonomous Underwater Vehicle Swarms. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(12):2249. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122249

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Zhuo, Shukai Jiang, Yifan Xue, Xiaokai Mu, and Chong Wang. 2025. "Fixed-Time Event-Triggered Fault-Tolerant Formation Control for Autonomous Underwater Vehicle Swarms" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 12: 2249. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122249

APA StyleWang, Z., Jiang, S., Xue, Y., Mu, X., & Wang, C. (2025). Fixed-Time Event-Triggered Fault-Tolerant Formation Control for Autonomous Underwater Vehicle Swarms. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(12), 2249. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122249