4.1. Effects of Salinity and Supercooling Degree on the Droplet Impact-Freezing Process

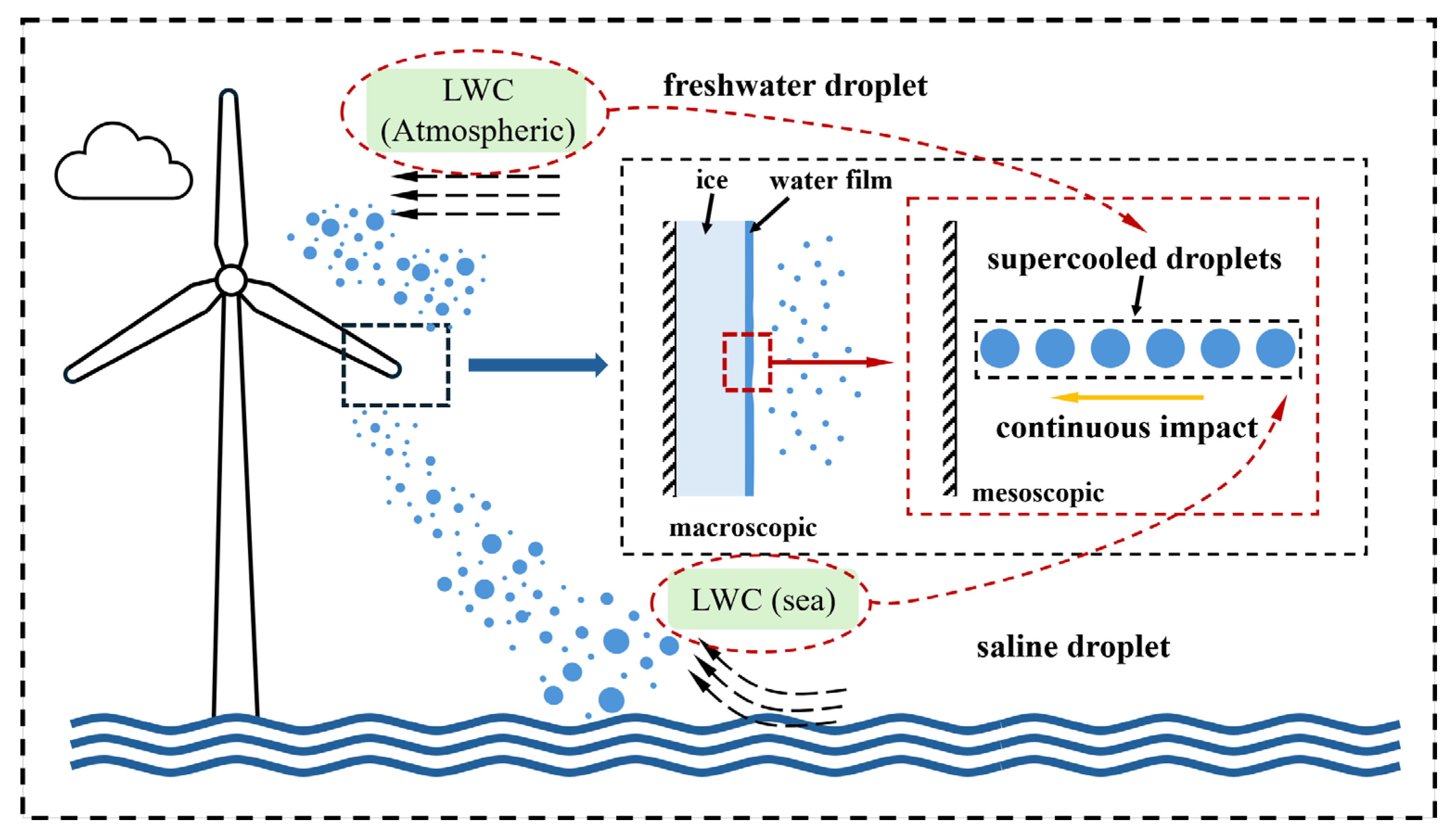

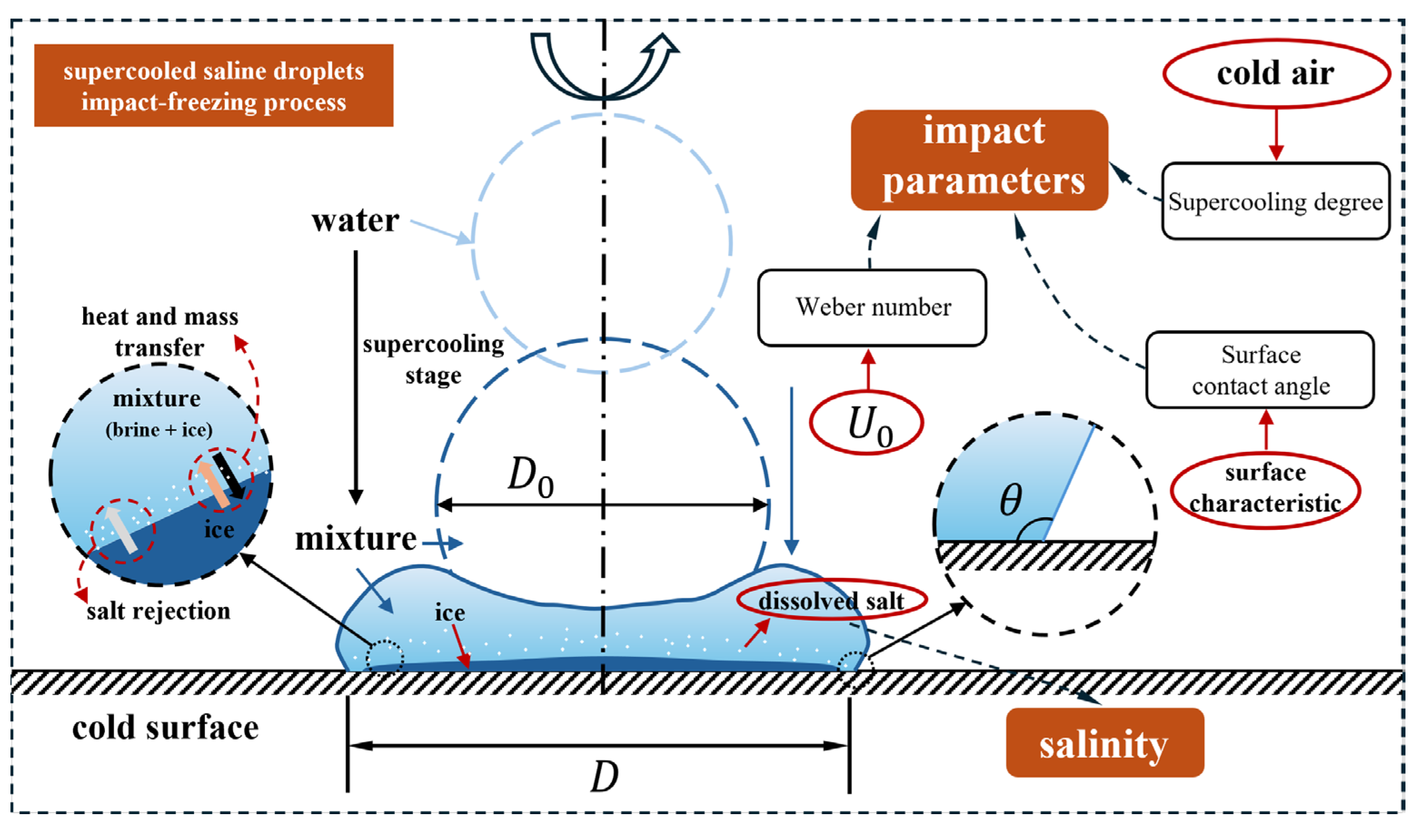

The salinity levels in global oceans exhibit significant spatial variability, with distinct differences observed even within specific regions of a single ocean. As salinity is a key factor affecting the freezing behavior of water droplets, this study investigates the impact-freezing characteristics of saline droplets with varying salinities under different conditions.

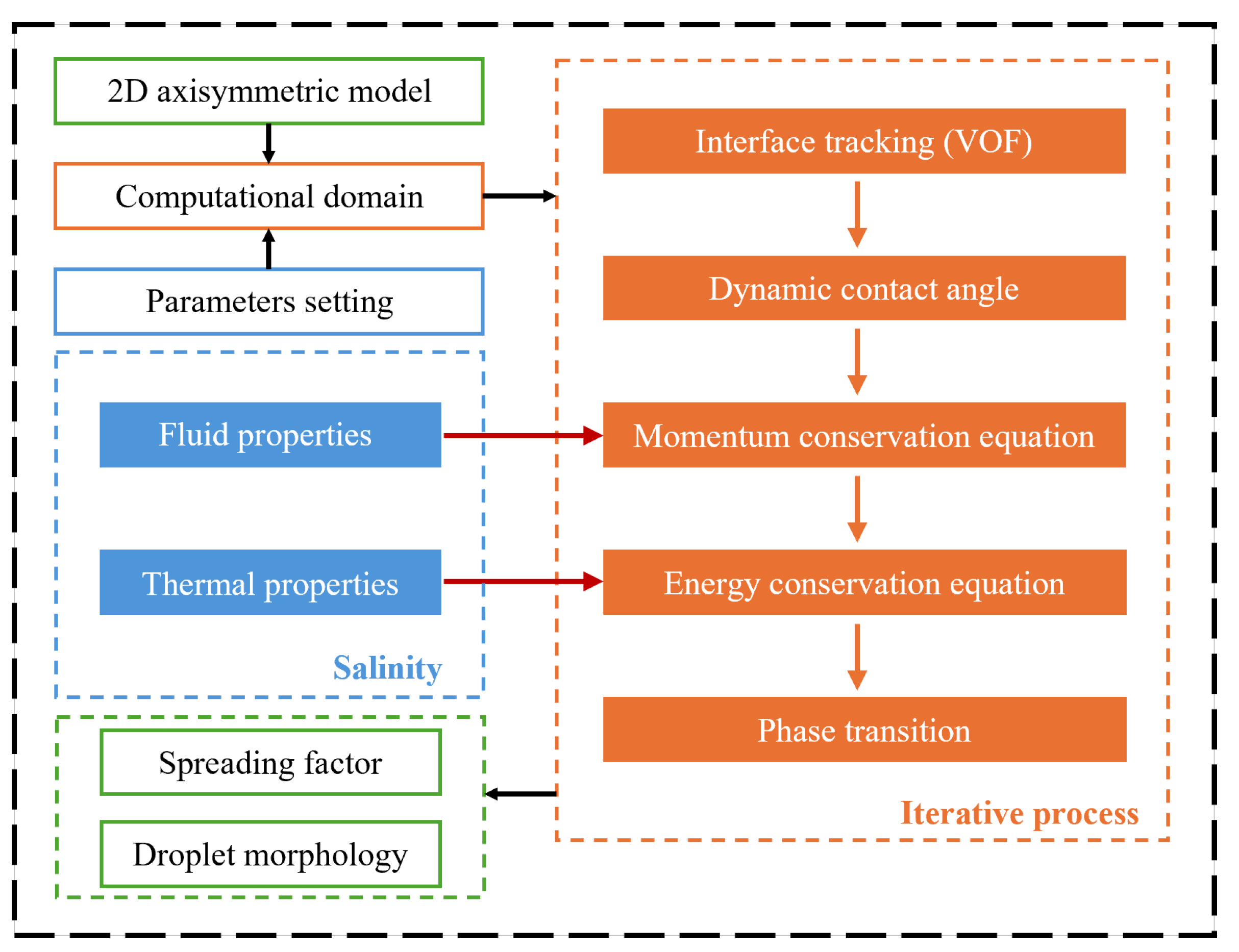

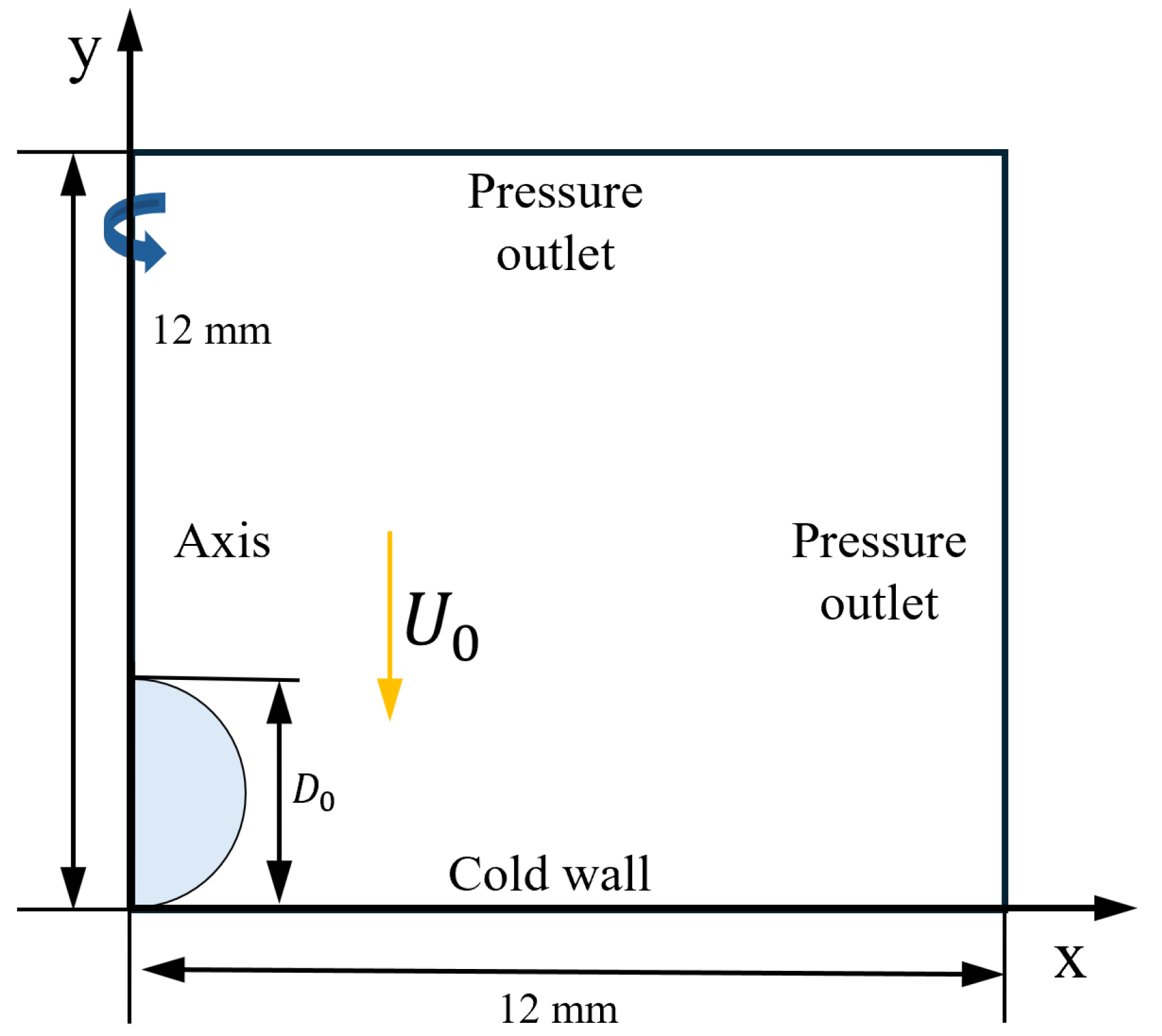

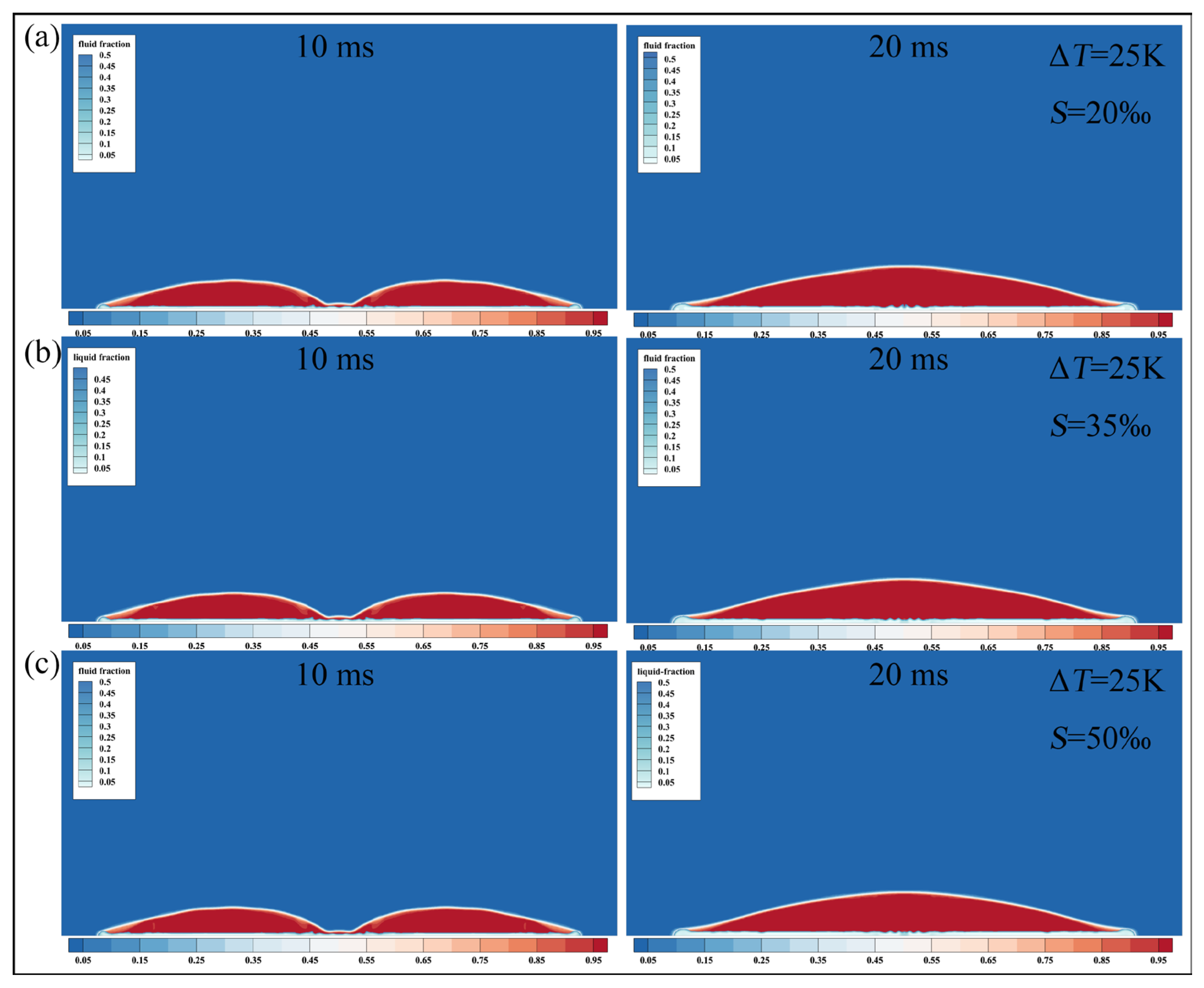

The working conditions in this section are hydrophobic surfaces, , . The droplets have Weber number of 60, salinity of , , and , and a size of (radius of ). Numerical simulations of droplets with supercooling degrees of , , and are performed to investigate the effect of supercooling degrees on the impact-freezing process of the droplets by comparing their spreading factors and relative deviation.

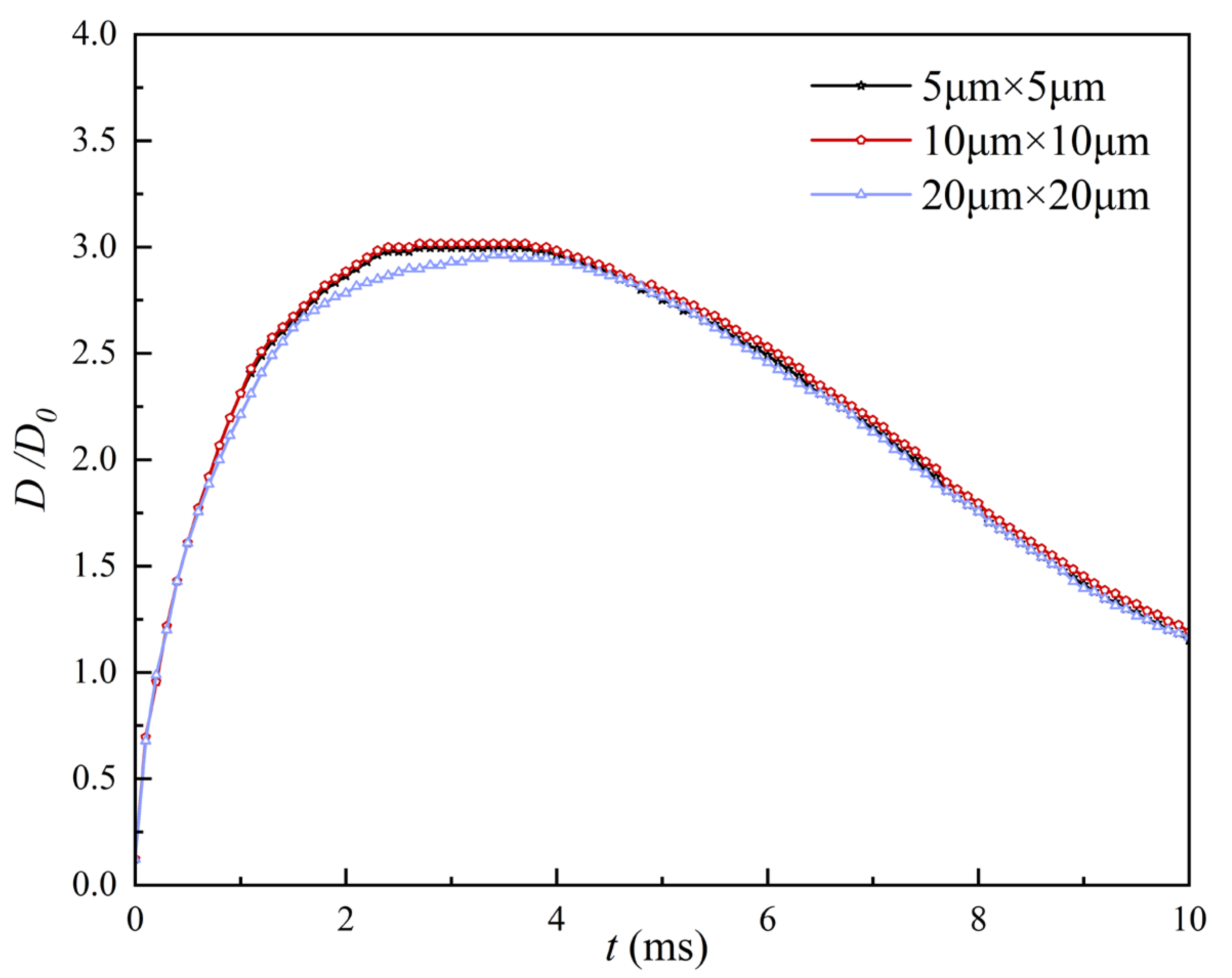

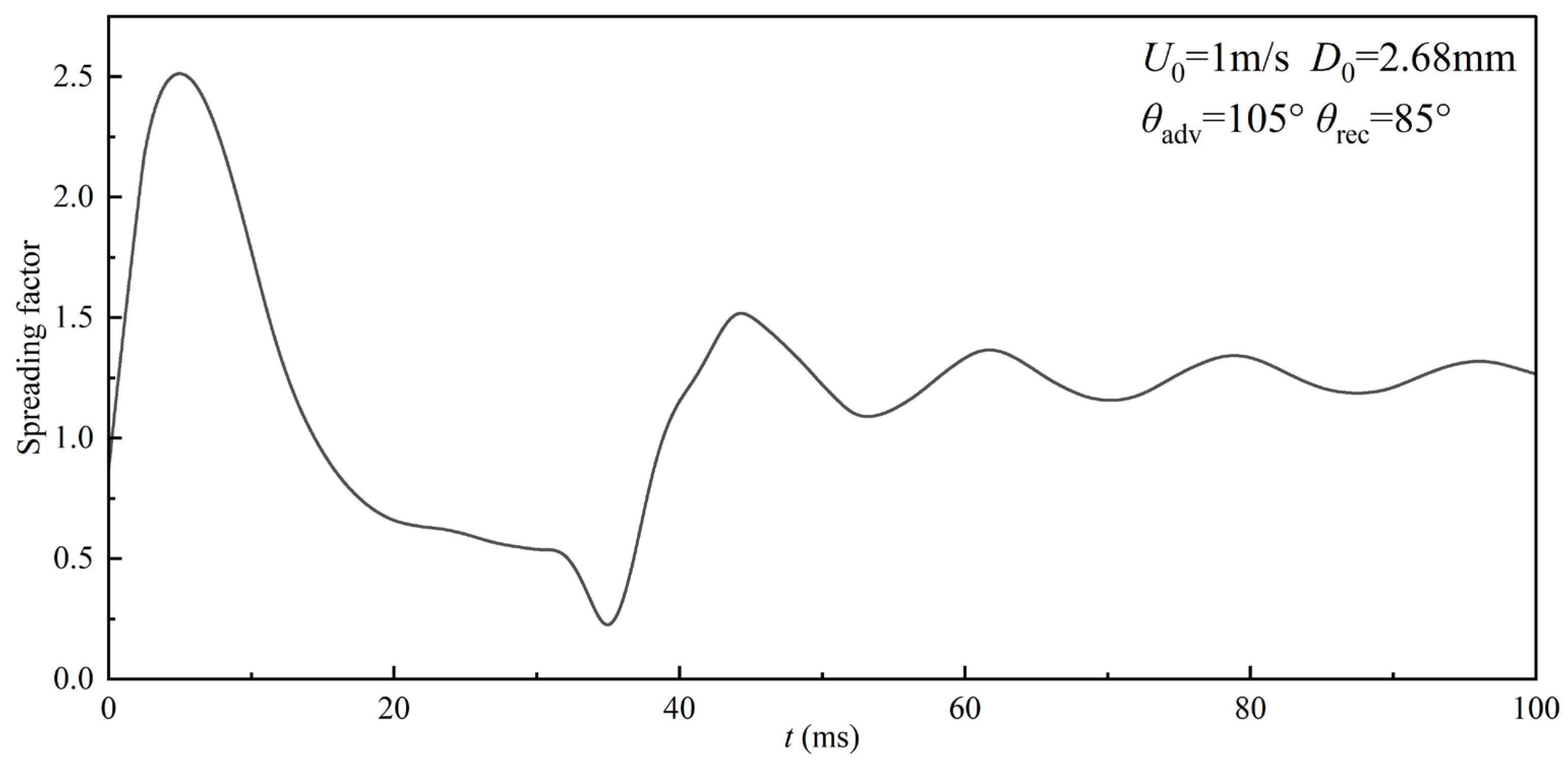

Figure 8 illustrates the temporal evolution of the spreading factor for a room-temperature droplet. The impact process comprises four stages: spreading, retraction, oscillation, and stabilization. Initial kinetic and gravitational energies drive rapid droplet spreading, while partial energy dissipates through wall adhesion and surface roughness. The remaining energy is converted into surface and internal energies. Once the kinetic energy is depleted, the spreading ceases, marking the maximum spreading extent. At this point (

), the droplet assumes a disk-like shape, characterized by a thinner center and a thicker rim, along with fluctuating contact angles. During the retraction phase (from

to

), surface tension becomes dominant, converting surface energy back into kinetic energy. This initiates periodic spreading-retraction oscillations, which continue until the system reaches equilibrium.

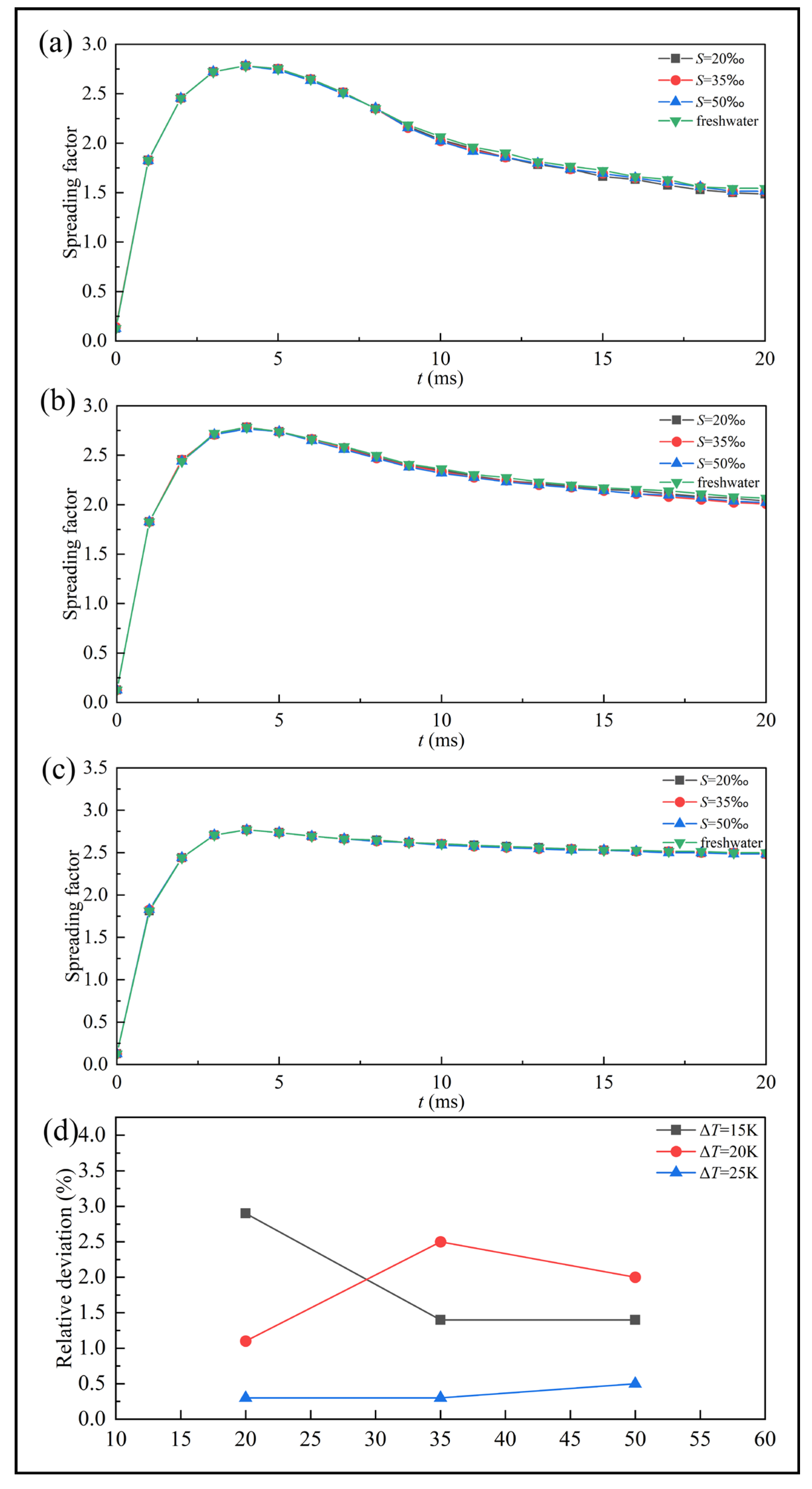

Figure 9 presents the spreading factor curves of freshwater and saline droplets under different supercooling degrees. Distinct differences are observed between supercooled and room-temperature droplets during the retraction stage. At room temperature, droplets retract rapidly after reaching their maximum spreading state. In contrast, supercooled droplets exhibit a gradual decrease in spreading factor, and this retraction trend becomes progressively weaker as the supercooling degree increases. When the supercooling degree reaches

, the droplets experience almost no noticeable retraction and transition directly into the freezing stabilization stage. Throughout the entire impact-freezing process, the spreading factors of saline droplets remain consistently lower than those of freshwater droplets, particularly during the retraction and stabilization stage.

Figure 9d shows the maximum relative deviations of the spreading factor between saline and pure water droplets at different supercooling degrees. These peak values consistently occur at

, a stage during which the spreading factor is relatively small. Consequently, even minor disturbances caused by variations in physics properties can lead to noticeable deviations. Moreover, as the supercooling degree increases, the salinity corresponding to the peak relative deviation also shifts, changing from a lower salinity (

) at

to a higher salinity (

) at

. And the peak relative deviation decreased from 2.39% to 0.5%, a decrease of 82.9%. This indicates that supercooling alters the mechanism by which salinity influences droplet impact-freezing process. The effect of salinity on the impact-freezing process is twofold. On one hand, salinity modifies fluid properties. For example, increasing viscosity enhances viscous dissipation and suppresses droplet retraction. On the other hand, salinity affects the solidification rate, which in turn influences droplet motion. Consequently, the retraction behavior of saline droplets is primarily governed by the competition between impact dynamics and solidification. Supercooling acts as one of the key parameters that determines which of these effects dominates.

An increase in supercooling degree leads to earlier freezing at the droplet base, slightly reducing the maximum spreading factor. From

Table 7, the maximum spreading factor decreases slightly from 2.79 to 2.76 as the supercooling degree increases, corresponding to a reduction of 1.1%.

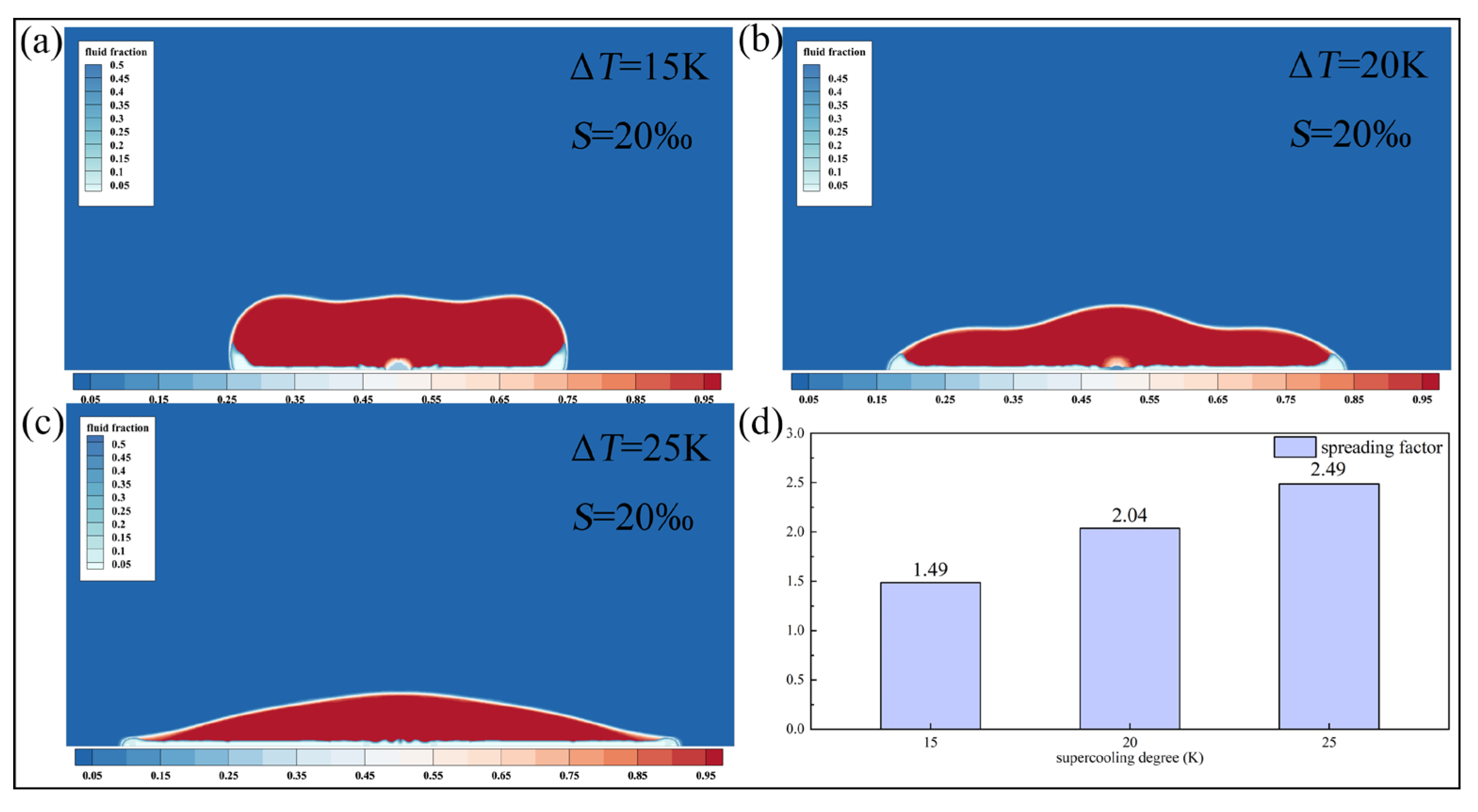

Figure 10 presents the morphologies of saline droplets with a salinity of

at

under different supercooling conditions, along with their corresponding spreading factors. As the supercooling degree increases from

to

, the spreading factor rises from 1.49 to 2.49, representing a 67.1% increase. At

and

, the droplets remain in a spreading state at this moment, indicating that higher supercooling degree enhances heat transfer between the droplet and the cold surface, thereby accelerating the solidification process. Meanwhile, with increasing supercooling degree, the phase-change driving force becomes more pronounced during the retraction stage. As a result, droplets with higher salinity, which exhibit delayed freezing characteristics, display larger relative deviations in spreading factor compared with freshwater droplets.

At lower supercooling degree (), droplet dynamics are primarily governed by hydrodynamic effects. Low-salinity droplets (), characterized by lower viscosity and reduced viscous dissipation, encounter less resistance during retraction and retract more completely, thereby producing larger maximum relative deviations. As the supercooling degree increases, the freezing phase transition gradually becomes the dominant mechanism controlling droplet motion. High-salinity droplets, which exhibit delayed solidification due to salt inhibition, undergo more pronounced retraction and thus exhibit greater relative deviations. However, at extremely high supercooling degrees (e.g., 25 K), both saline and freshwater droplets are strongly constrained by rapid solidification, leading to overall smaller relative deviations in spreading factor compared with those at lower supercooling conditions.

The above analysis indicates that salinity induces observable relative deviations in the spreading factor during the retraction stage of droplet impact-freezing process. These deviations reflect the systematic effects caused by variations in physics properties. It is worth noting that, as shown in

Figure 11, changes in salinity exert limited influence on the overall morphological evolution of droplets under identical conditions. The differences are primarily manifested through variations in the spreading factor. This feature ensures that applying corrections based on relative deviations does not introduce additional errors associated with morphological differences. Although the relative deviations for individual droplets remain relatively small, the cumulative effect of repeated droplet impacts in natural environments can lead to significant differences in macroscopic ice accretion. Furthermore, the quantifiable nature of these deviations provides a solid basis for incorporating them as correction factors into existing droplet dynamic models.

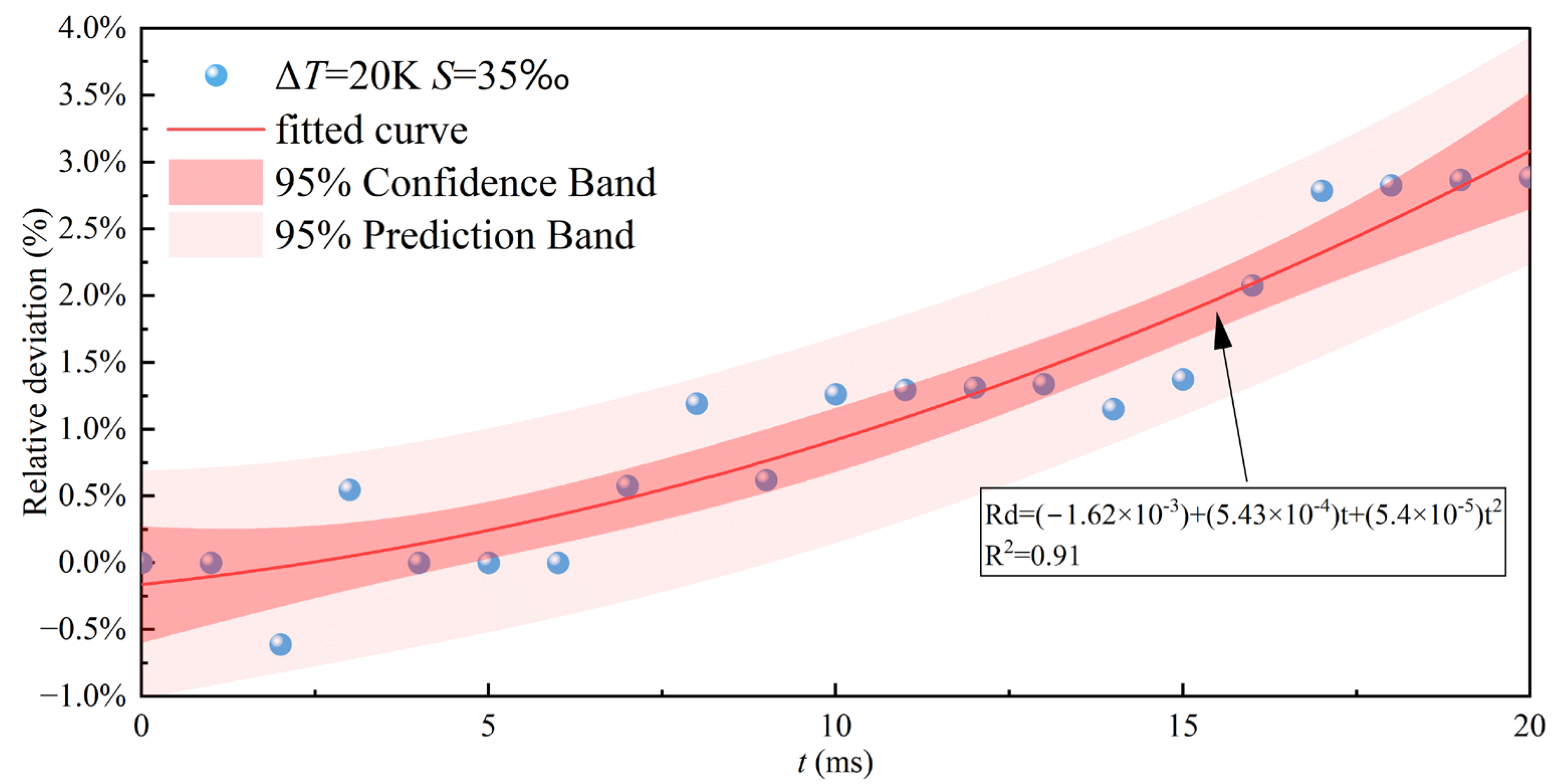

Figure 12 presents the fitted curve of the relative deviation over time for droplets with a salinity of

at a supercooling degree of

. The curve exhibits a nonlinear increasing trend, with smaller deviations during the early stage and larger deviations during the retraction and stabilization stages. This behavior indicates that the influence of salinity on the impact-freezing process primarily emerges in the middle and later stages. By applying relative-deviation-based corrections to the spreading factor, the impact-freezing process of saline droplets under different impact conditions can be more accurately represented. Moreover, such correction factors can provide essential parameters for macroscopic icing prediction models, enhancing their applicability in saline marine environments without significantly increasing computational cost.

It should be noted that the fitted curves presented in this study are derived under specific parameter conditions and are therefore strictly applicable only to the corresponding environments. To enhance the generality of this correction approach, a systematic and rapid analysis can be performed across a wide range of operating conditions to obtain multiple fitted curves and establish a comprehensive database of correction parameters. In practical applications, environmental data such as ambient temperature, wind speed, and Liquid Water Content (LWC) can be obtained in real time from onboard monitoring systems. The corresponding correction parameters can then be rapidly retrieved and integrated into existing ice prediction models, enabling adaptive, accurate, and computationally efficient forecasting of ice accretion on offshore wind turbine blades.

4.2. Effects of Salinity and Surface Contact Angle on the Droplet Impact-Freezing Process

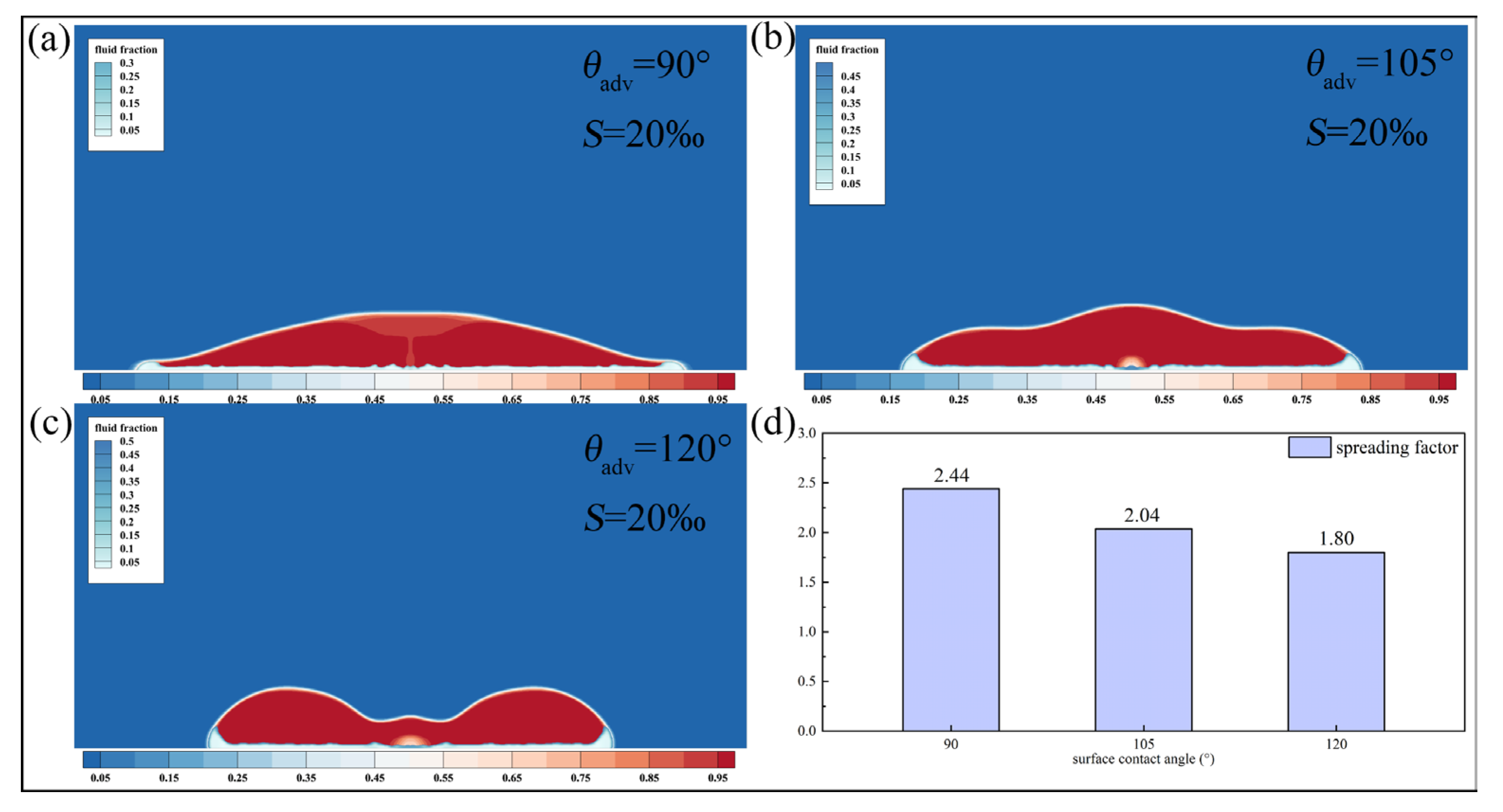

To investigate the effect of contact angle on the dynamic characteristics of supercooled droplets, the concept of contact angle hysteresis, defined as , is introduced. The simulations in this section set the Weber number to 60, the droplet size to (radius of ), the supercooling degree to , salinity from to , and to . In this paper, the impact-freezing process of droplets on three different wettability surfaces is simulated (i.e., ).

Figure 13 presents the spreading factor curves of freshwater droplets and saline droplets with three different salinities at various contact angles. A dynamic contact angle model was introduced in this study to account for contact angle hysteresis; therefore, a contact angle of 90° actually corresponds to a hydrophilic surface. Under this condition (

Figure 13a), the spreading factor curve decreases slowly after reaching its maximum value, indicating weak droplet retraction. As the contact angle increases, the spreading factor curve decreases more rapidly, implying more pronounced retraction on hydrophobic surfaces, as shown in

Figure 13b,c. Consistent with the results shown in

Figure 9, the spreading factor curves of freshwater droplets are consistently higher than those of saline droplets, with the maximum relative deviation occurring at

, as illustrated in

Figure 13d. The red curve corresponds to the case with a supercooling degree of 20 K analyzed in

Section 4.1, under the current condition of a contact angle of 105°. From

Figure 13d, it can be observed that for contact angles of 90° and 120°, the maximum relative deviation increases with salinity. This indicates that variations in surface wettability influence the competition between impact dynamics and solidification, as discussed in

Section 4.1.

Increasing the contact angle intensifies retraction, resulting in a nearly linear decrease in the maximum spreading factor. From

Table 8, the maximum spreading factor decreases from 2.96 to 2.63 as the contact angle increases, representing a reduction of 11.1%.

Figure 14 shows the morphology of saline droplets with a salinity of

on surfaces with different wettability at

. As the contact angle increases from 90° to 120°, the droplet shape transitions from a spread state with a convex center to a retracted state with a concave center. Correspondingly, the spreading factor at this time decreases from 2.44 to 1.80, a reduction of 26.2%.

On hydrophilic surfaces, the larger spreading area enhances heat exchange with the substrate, making the spreading factor curve more sensitive to the effects of phase change. As a result, high-salinity droplets (

), which have lower thermal conductivity and slower phase-change rates, exhibit more pronounced retraction and the highest maximum relative deviation on hydrophilic surfaces. This behavior is consistent with the characteristics observed for saline droplets at high supercooling degrees (

) in

Section 4.1.

On strongly hydrophobic surfaces with a contact angle of 120°, the weaker adhesion between the droplet and the wall reduces resistance during retraction, allowing surface tension to dominate the droplet motion and accelerating retraction. This corresponds to the rapid decrease observed in the spreading factor curves in

Figure 13. Consequently, hydrophobic surfaces suppress the influence of phase change by rapidly reducing the heat exchange area through faster retraction. Moreover, as salinity increases, the enhanced surface tension of the droplet leads to greater retraction, resulting in larger relative deviations from freshwater droplets.

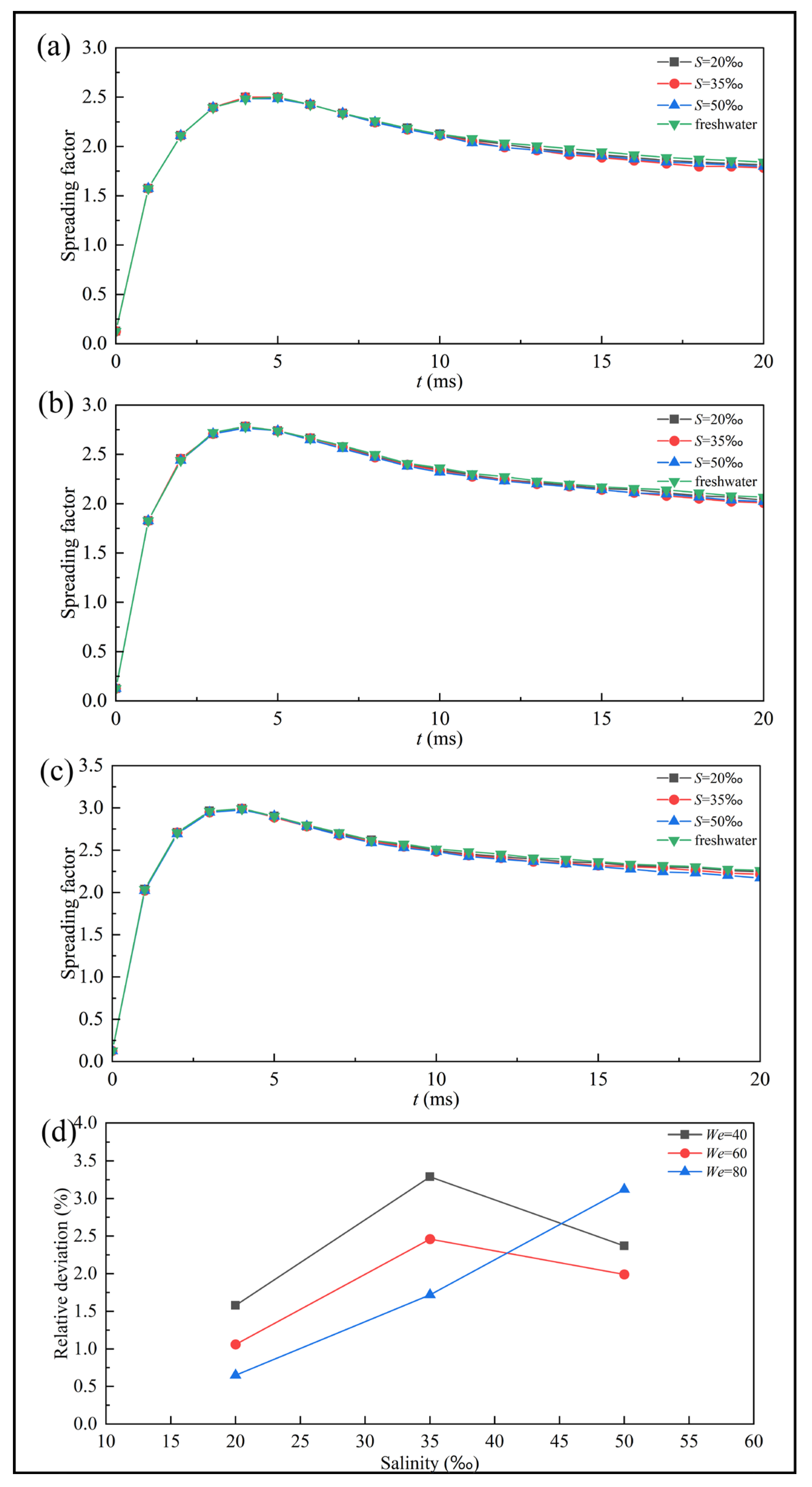

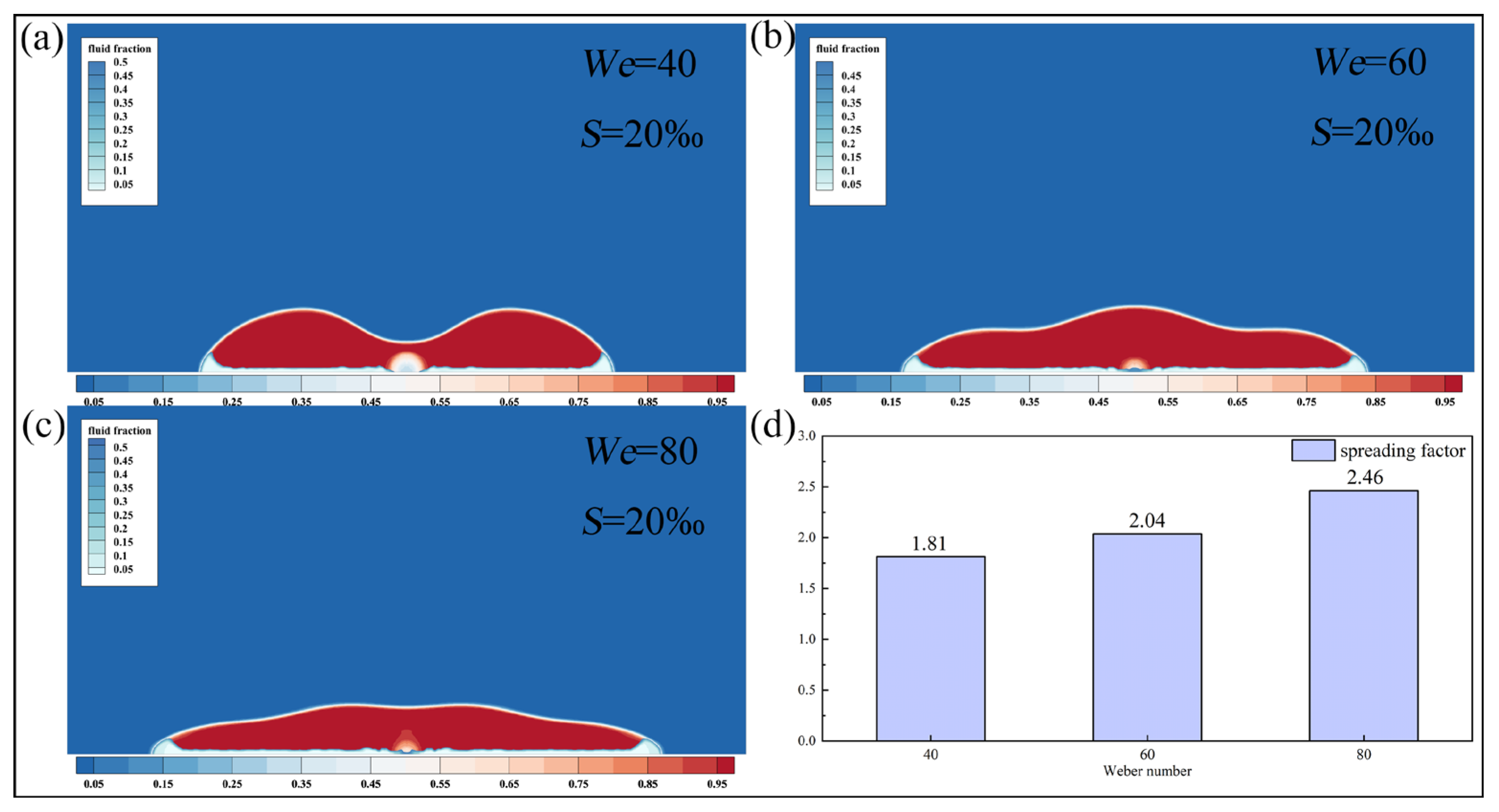

4.3. Effects of Salinity and Weber Number on the Droplet Impact-Freezing Process

To describe the dynamic behavior of droplets more accurately, the Weber number () is introduced in this section. When is small, the surface tension effect dominates. When is much greater than 1, the effect of surface tension is negligible. Under the simulated operating conditions, the droplet diameter is . In this section, the effect of the Weber number and salinity on the impact-freezing process is investigated. Specifically, the salinities are , , and , and the Weber numbers are 40, 60, and 80. The rest of the conditions are , , and .

Figure 15 presents the spreading factor curves of saline and freshwater droplets at different Weber numbers. The results indicate that the spreading factor curves of freshwater droplets are consistently higher than those of saline droplets, and the maximum relative deviation for saline droplets still occurs at approximately

. The overall trends of the spreading factor curves for saline and freshwater droplets remain similar across different Weber numbers, with the primary differences in the maximum spreading factor.

An increase in the Weber number significantly enhances spreading capacity. From

Table 9, the maximum spreading factor increases from 2.50 to 2.99 as the Weber number increases, corresponding to a 19.6% rise. As shown in

Figure 15d, the relative deviation trends with increasing salinity are similar for Weber numbers of 40 and 60. However, at a Weber number of 80, this trend changes, with the relative deviation progressively increasing as salinity rises.

Figure 16 illustrates the morphology of saline droplets as the Weber number increases from 40 to 80. Elevated impact velocity enhances the initial kinetic energy, leading to broader droplet spreading. At

, the droplet with high Weber number exhibits slow retraction state and maintains a spread morphology. In contrast, the droplet with low Weber number has already entered a significant retraction state. Therefore, as the Weber number increases, the spreading coefficient at

increases from 1.81 to 2.46, an increase of 35.9%.

Under high Weber number conditions, droplets possess greater initial kinetic energy, resulting in stronger radial spreading upon impact. Upon reaching the maximum spreading state, surface tension must overcome greater inertial resistance to drive droplet retraction. Furthermore, the high Weber number often corresponds to the high Reynolds number, leading to more intense internal flow within the droplet. This increases viscous dissipation and consequently weakens the power of retraction. The droplet with low Weber number can directly convert surface energy into kinetic energy during retraction, resulting in significantly faster retraction speeds.

The case with a Weber number of 60 corresponds to the supercooling degree of 20 K analyzed in

Section 4.1. As discussed earlier, the non-monotonic variation in the maximum relative deviation at

primarily arises from the competition between impact dynamics and solidification. At

, the droplets of moderate salinity (

) exhibit the largest relative deviation due to a balanced combination of moderate viscous dissipation and relatively slow solidification rates. When the Weber number decreases to 40, the initial kinetic energy of all droplets is lower, and the relative deviation still follows a similar trend to that observed at

. In contrast, increasing the Weber number intensifies the initial kinetic energy, causing droplet behavior during the retraction stage to be dominated by hydrodynamics. Additionally, droplets with higher salinity have greater density, which enhances their inertia. As a result, under high Weber number conditions, droplets with higher salinity exhibit stronger retraction, leading to larger maximum relative deviations.

In addition to the time-dependent fitting curve method proposed in

Section 4.1 for refining icing prediction models in cold marine environments, the maximum relative deviation can be treated as a single scalar parameter that can be directly embedded into droplet motion models or macroscopic icing prediction models to correct the impact-freezing process of saline droplets.

Because the maximum relative deviation typically occurs during the retraction and stabilization phase, where deviations are most pronounced, this parameter effectively captures the combined influence of salinity on droplet dynamics and phase-change coupling. Moreover, the analysis indicates that variations in salinity have a limited impact on overall droplet morphology and primarily affect the spreading factor, providing a robust foundation for quantitative corrections based on relative deviation. By systematically compiling maximum relative deviations under various conditions, a correction parameter database can be established, enabling rapid model adjustments as shown in

Table 10. Compared with the fitting-curve method, this approach eliminates the need to account for temporal variations and can enable direct model correction through empirical coefficients. Such simplicity makes it well suited for practical engineering applications, such as icing prediction for offshore wind turbines.