1. Introduction

Breakwaters are a critical component of coastal protection systems and are designed to attenuate wave energy, thereby ensuring safe and reliable operational environments for sheltered areas. Although fixed breakwaters demonstrate effective wave-attenuation performance, their construction difficulty and cost increase significantly with water depth. Moreover, natural water circulation is impeded, resulting in sediment accumulation and degradation of water quality. Over 90% of wave energy is concentrated within a depth of three times the wave height below the free surface. Compared with fixed breakwaters, floating breakwaters (FBs) are better adapted to the distribution of wave energy and offer advantages such as lower foundation bearing-capacity requirements, reduced construction cost, convenient installation and removal, and improved water circulation.

Attention has been paid to the box-type FB due to its simple geometric cross-section and stable operation in the ocean. Sutko [

1] investigated the hydrodynamic performance of FBs with triangular, rectangular, and circular cross-sections. The rectangular FB had better wave attenuation performance. Drimer et al. [

2] derived the analytical solution to the two-dimensional hydrodynamic problem of wave interaction with a box-type FB. Williams et al. [

3] applied the 2-D potential theory to study the performance of two long FBs arranged side-by-side. Masoudi and Zeraatgar [

4] used the method of separation of variables to analyze the hydrodynamic characteristics of a two-dimensional box-type FB in water of finite depth and infinite domain. Based on linear water-wave theory, Deng et al. [

5] developed an analytical theory of the interaction of monochromatic waves with T-shaped FBs through the matched eigenfunction expansion method. For numerical research, Rahman et al. [

6] applied the volume of fluid method to analyze the nonlinear dynamics of a box-type submerged FB subject to wave action and mooring forces. Peng et al. [

7] studied the interaction of waves with a submerged box-type FB moored by inclined tension legs, using a water tank model proposed by Lee and Mizutani [

8]. Ren et al. [

9] developed the Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics (SPH) method to simulate the nonlinear interaction between waves and a box-type FB. Based on the

δ-SPH method, Guo et al. [

10] compared the hydrodynamic performance of a box-type FB with taut, slack, and hybrid mooring systems under variable tidal ranges. Chen et al. [

11] also employed the

δ-SPH method to investigate the wave-attenuation performance and dynamic response of a twin FB consisting of two identical boxes with independently assembled mooring systems. He et al. [

12] proposed a flexibly connected multi-float structure and demonstrated that a larger number of modules will contribute to more wave energy dissipation.

A physical experiment is a reliable method for studying the hydrodynamic characteristic of box-type FB. It can be categorized into two-dimensional wave flume and three-dimensional water tank experiments. Wave flume experiments are favored by numerous researchers due to the cost-effectiveness. Sannasiraj et al. [

13] measured the motion responses and mooring forces of the FB with three mooring configurations: moored at water level; moored at the base bottom; and cross-moored at the base bottom. Huang et al. [

14] compared the hydrodynamic performance of the box-type FB with and without slotted barriers. Christensen et al. [

15] analyzed the damping mechanisms of three types of FBs: a pontoon, a pontoon with wing plates, and a pontoon with wing plates and porous media. They found that attaching wing plates to the FB significantly reduced the motion. Ji et al. [

16] revealed that the double-row box-type FBs have better wave attenuation than the single-row ones. Liang et al. [

17] compared the hydrodynamic characteristics of the box-type FB under fixed condition and three different mooring configurations. The cross mooring and parallel mooring configurations without section lying on the seabed are effective in reflecting and dissipating longer period waves. He et al. [

18] investigated the hydrodynamic performance of a box-type FB with vertical plates as wave-dissipating components. The results showed that the water confined by plates increases the FB’s natural period of pitch motion towards longer waves, and thus the violent energy dissipation occurs at longer waves.

Water tank experiments are convenient for investigating the overall hydrodynamic characteristics of box-type FBs and the wave distribution. Martinelli et al. [

19] compared the wave transmission loads along moorings and connectors of FBs with I-shaped and J-shaped layouts under oblique waves. Loukogeorgaki et al. [

20] tested the FB consisting of an array of multiple modules that are connected with flexible connectors under perpendicular and oblique regular and irregular waves. Recently, Ji et al. [

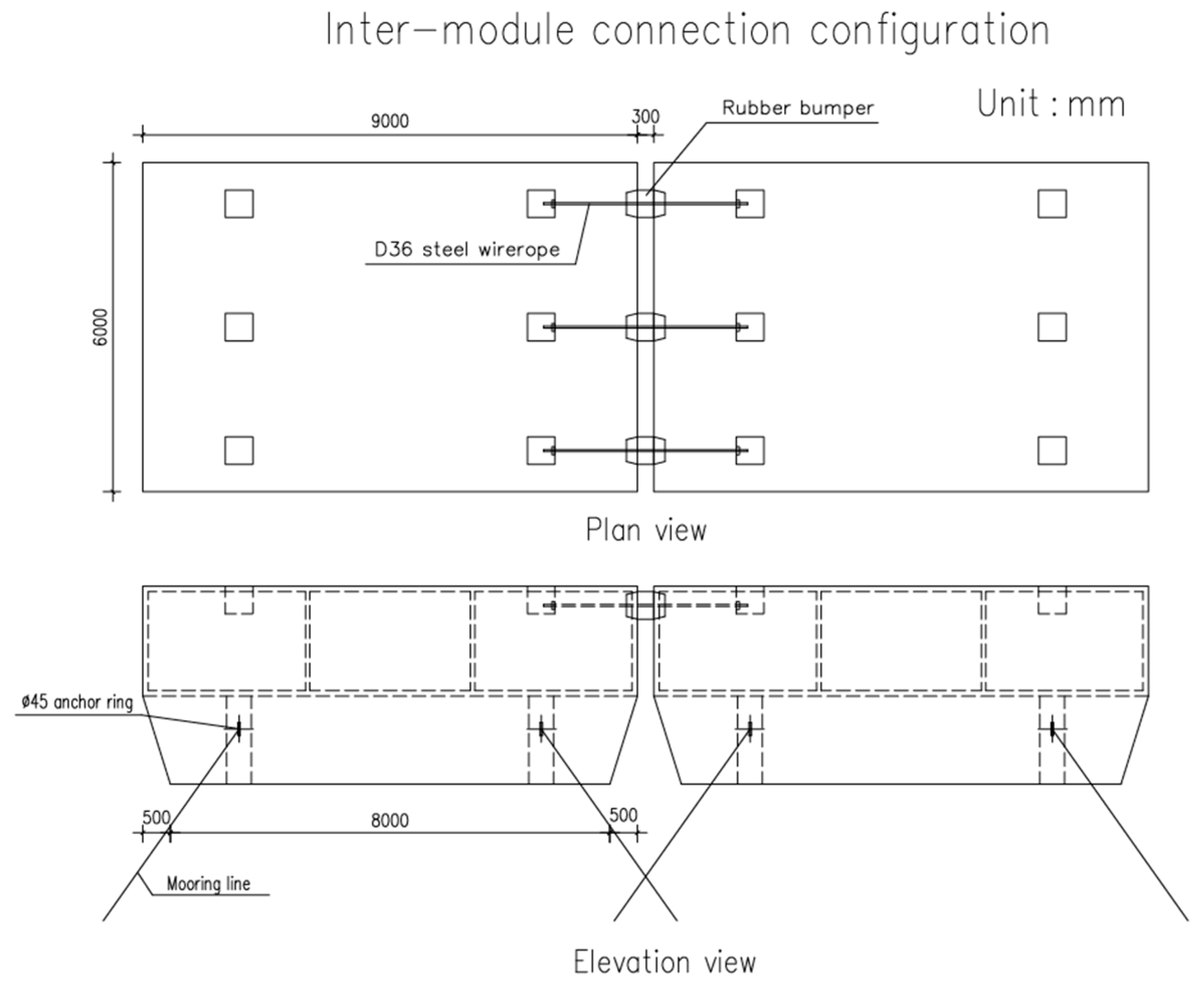

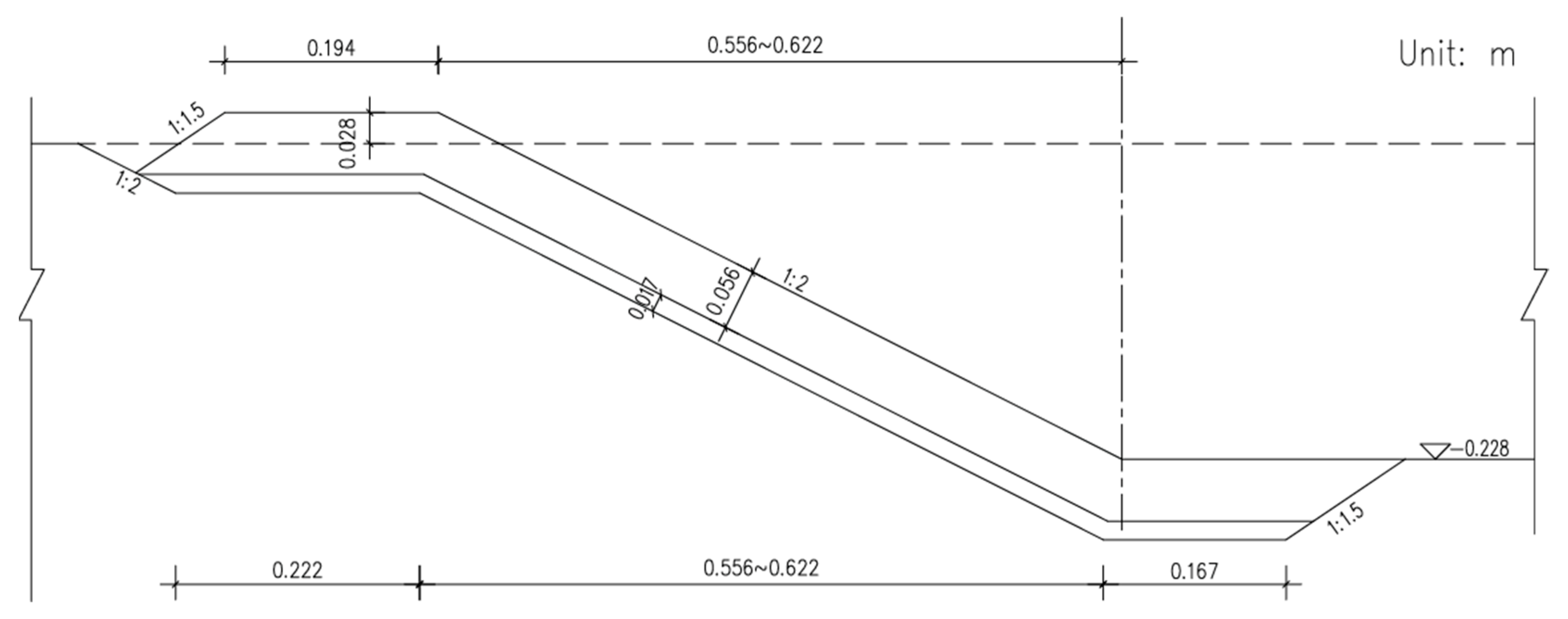

21] investigated the hydrodynamic performance of three interconnected modules, each of which was designed with wing structures and forward openings on both sides of a double-box FB. Mao et al. [

22] demonstrated that adding a wing plate can improve the wave attenuation performance of the FB, due to the increase in draft and wave-blocking area. The layout of FBs needs to be adapted to the protected area’s bathymetry. However, most studies focus only on straight layout without considering the influence of nearshore bathymetry and structures. In this work, a water tank experiment is conducted to investigate the wave attenuation performance, motion responses, mooring tensions, and surface wave pressures of streamlined-layout double-row FBs, designed for a Chinese port, under the realistic coastal environment. The examined FBs consist of winged box-type modules connected with flexible connectors.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 introduces the experimental setup, comprising the test facility and layout, physical model, and wave conditions.

Section 3 presents the measurement results, including wave attenuation performance, motion responses, mooring tensions, and surface wave pressures of the FBs.

Section 4 summarizes the main conclusions.

4. Conclusions

This work investigated streamlined-layout double-row FBs with wing plates designed for a specific port. Wave attenuation performance, motion responses, mooring tensions, and surface wave pressures were systematically evaluated through a water tank experiment. The main conclusions are as follows.

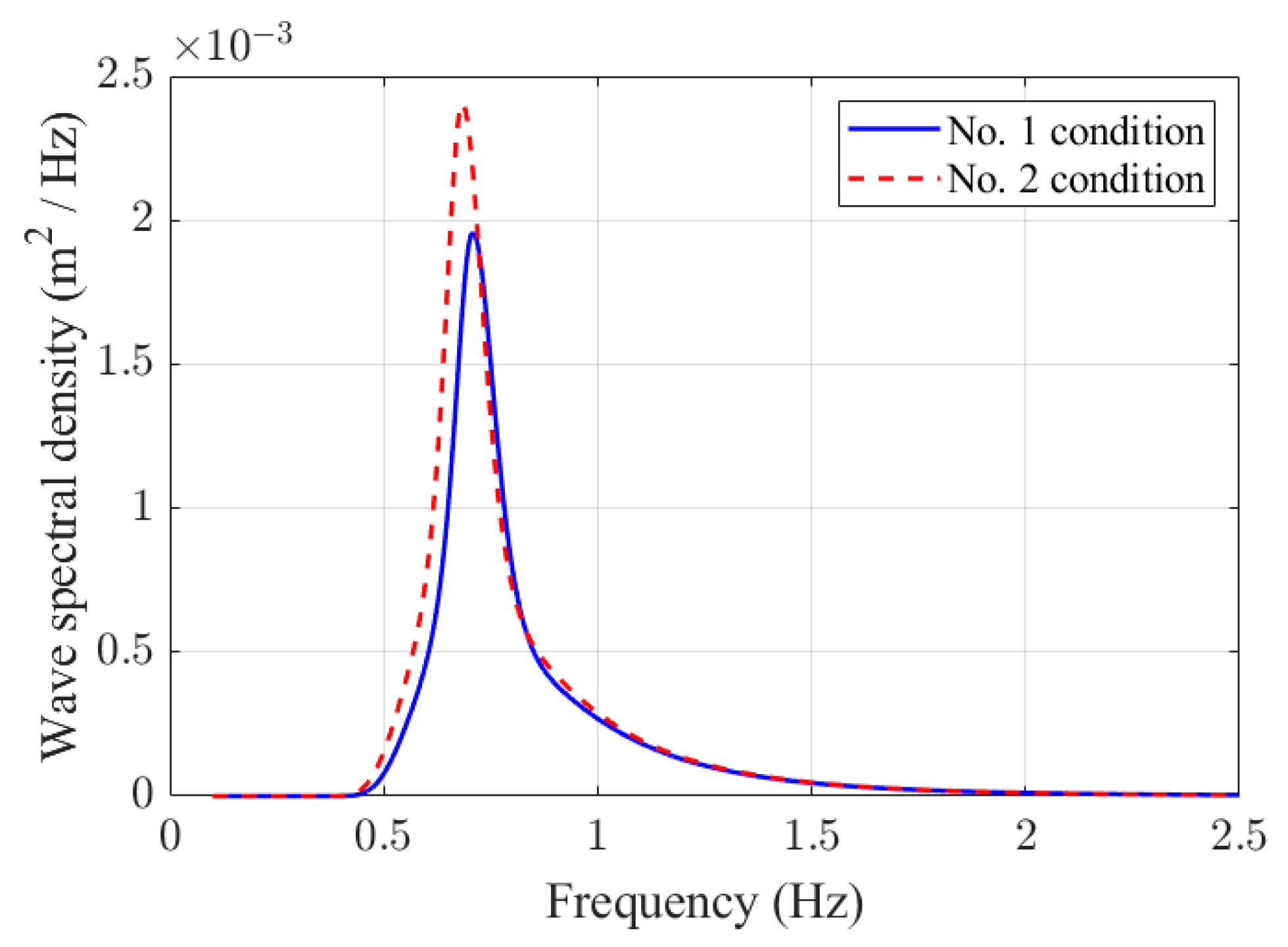

Under extreme high-water-level conditions with 10-year and 50-year return periods, the FBs achieve wave-height attenuation of 22.36~30.08% and 16.04~19.03%, respectively, with the transmission coefficients of 0.6577 and 0.7304. Wave reflection from nearshore structures affects harbor tranquility and intensifies significantly with increasing incident wave height and period. Therefore, coastal FB design needs to account for the effects of realistic bathymetry and structures.

As wave height and period increase, the maximum amplitudes of the FBs’ motion responses change slightly. The maximum prototype-scale changes in surge, heave, and pitch amplitudes are +0.0625 m, −0.488 m, and +3.8523°, respectively. For surge motion, the overall response and the positive-direction amplitude of the head module are greater, while the tail module exhibits a larger negative-direction amplitude. For heave motion, the tail module demonstrates greater overall responses and motion amplitudes in both positive and negative directions. For pitch motion, the head and tail modules show comparable responses, but the latter is more sensitive to wave parameter variations.

The tensions in the mooring lines of the head module generally exceed those of the tail module and are more sensitive to wave parameter variations. The horizontal wave pressure on the seaward face of the FBs exceeds that on the leeward face. Although the downward pressures on the top surfaces of the head and tail modules are nearly identical, the uplift pressure on the tail module is greater. Additionally, the uplift pressures on the two modules remain relatively constant as wave height and period increase, with the maximum prototype-scale changes being +2.3 kPa and −5.6 kPa, respectively. However, the head module experiences increased horizontal pressure and reduced downward pressure, whereas the tail module shows the opposite trend. In the future, further experiments will be conducted to investigate the relative motion between the offshore and nearshore breakwaters, the causes of the extreme values of wave heights, motion responses and mooring tensions, and the risks associated with mooring line failure.