Abstract

To address challenges such as sparse feature representation difficulties and poor robustness in detecting weak targets against sea clutter backgrounds, this study investigates the adaptability of channel modeling and sparse reconstruction techniques for target recognition. It proposes a method for detecting small sea targets that integrates OTFS with deep unfolding. Using OTFS modulation to map signals from the time domain to the Delay-Doppler domain, a sparse recovery model is constructed. Deep unfolding is employed to transform the FISTA iterative process into a trainable network architecture. A GAN model is employed for adaptive parameter optimization across layers, while the CBAM mechanism enhances response to critical regions. A multi-stage loss function design and false alarm rate control mechanism improve detection accuracy and interference resistance. Validation using the IPIX dataset yields average detection rates of 88.2%, 91.5%, 90.0%, and 83.3% across four polarization modes, demonstrating the proposed method’s robust performance.

1. Introduction

Sea clutter is a common natural phenomenon in marine radar detection [1], consisting of radar echoes generated by sea surface waves. It exhibits complex spatial and temporal variations, along with non-stationarity under varying sea conditions and radar observation parameters. Its multidimensional non-Gaussian characteristics become particularly pronounced at high resolutions [2], while target echoes are typically weak with low signal-to-noise ratios (SNRs). This combination has made detecting small surface targets a persistent challenge for researchers.

Significant statistical and modulation differences exist between sea clutter and small target echoes; sea clutter signals typically exhibit strong non-Gaussianity, spectral spreading, and intense instantaneous frequency fluctuations, with dispersed energy distribution and high randomness. In contrast, small target echoes show localized spectral concentration, stable energy distribution, and distinct modulation characteristics [3]. This divergence primarily stems from differing physical generation mechanisms. Sea clutter arises mainly from Lagrange and white noise scattering induced by sea surface roughness, heavily influenced by wind waves, polarization modes, and incidence angles; target echoes, constrained by their size, shape, and radar cross section, exhibit more stable reflection characteristics. This distinction provides a theoretical basis for feature extraction and target detection.

Traditional small target detection methods primarily rely on statistical theory and the fractal and chaotic characteristics of sea clutter. Statistical theory achieves target detection by establishing statistical models of sea clutter amplitude. However, this approach exhibits poor adaptability in complex sea conditions, limited detection performance, and struggles to characterize the time-varying and non-stationary properties of sea clutter effectively [4]. Fractal and chaotic properties serve as crucial descriptors for sea clutter, capable of characterizing its spatial structure and temporal evolution. Nevertheless, related research has largely remained theoretical, requiring estimation of multiple parameters such as fractal dimension, embedding dimension, and time delay. This high computational complexity imposes significant constraints on engineering applications. Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiplexing (OFDM) offers distinct advantages in low-dynamic environments. By introducing frequency diversity, it enables different scattering centers to resonate at distinct frequencies, thereby providing richer information for target detection. In the MIMO radar system proposed by Sen et al. [5], OFDM enhances detection accuracy and target tracking capabilities for multi-antenna systems. However, OFDM faces limitations under high-speed targets and complex sea clutter conditions, particularly due to Doppler effects and inter-carrier interference (ICI), which degrade performance. A waveform integration method based on WFRFT-OTFS was proposed by Wang et al. [6]. By mapping signals to the Delay-Doppler (DD) domain using Orthogonal Time Frequency and Space (OTFS), they equate the time-frequency dual-selective channel to an approximately invariant sparse channel in the DD domain. The method effectively enhances system robustness in high-speed moving and frequency-spanning environments, demonstrating superior performance over OFDM in terms of bit error rate (BER) and channel capacity.

Furthermore, in the field of sparse signal recovery, compressive sensing methods have emerged as a prominent research direction. Orthogonal Matching Pursuit (OMP) is a classic greedy algorithm widely applied in signal processing tasks. However, OMP suffers from redundancy selection issues that may lead to recovery errors. Particularly in maritime noise environments, it is susceptible to multipath interference, resulting in lower recovery accuracy. Yan et al. [7] proposed an improved OMP method that enhances robustness in complex sea clutter environments by optimizing dictionary selection and mitigating the impact of redundant atoms. However, this approach still faces challenges such as high computational complexity and slow convergence rates. Wu et al. [8] introduced the Projection Matching Pursuit (PMP) method, which reduces redundancy selection by incorporating projection matrices at each iteration, thereby improving sparse recovery accuracy. They optimized computations using QR decomposition, improving recovery accuracy in dynamic environments. Nevertheless, PMP exhibits high computational complexity, particularly under large-scale datasets, increasing the algorithmic burden. To overcome PMP’s limitations, Yang et al. [9] introduced the Distributed Compressed Sensing (DCS) method. By leveraging collaborative processing across multiple sensors, DCS enhances signal recovery accuracy and robustness in environments with strong sea clutter and multipath interference. Compared to PMP, DCS significantly improves signal recovery accuracy through multi-source data fusion. However, DCS suffers from high computational complexity and still faces substantial computational overhead.

Today, with the maturation of deep learning technologies, end-to-end design has emerged as a key approach for reducing computational complexity and optimizing algorithm parameters. Cai et al. [10] proposed an end-to-end classification network incorporating ResNet modules to classify subglacial targets beneath ice sheets automatically. By integrating an enhanced Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling module with a decoder module, this method significantly improved classification accuracy for radar imagery while effectively reducing computational overhead. Cao et al. [11] proposed FISTA-Net for Cherenkov luminescence tomography (CLT) reconstruction. By integrating neural network components with the Fast Iterative Shrinkage-Thresholding Algorithm (FISTA), it substantially enhances image reconstruction quality and accuracy.

To fully leverage the differences in sparsity structure between sea clutter and target echoes, this study proposes a method for detecting small sea targets by integrating OTFS with deep unfolding. This approach utilizes OTFS modulation to map signals from the time domain to the DD domain. It employs the concept of deep unfolding to embed the FISTA optimization process within a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) framework, while introducing tensor parameter modeling to replace traditional matrix operations. Addressing limitations in existing Tensor-FISTA-Net methods—such as ambiguous target or background responses and insufficient spatial attention during feature extraction—this study further incorporates a Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) mechanism. This module adaptively enhances critical feature responses across both channel and spatial dimensions. Subsequently, sparsity and energy distribution features are extracted. The feature vectors are fed into a GAN classifier, which dynamically updates decision thresholds to control the false alarm rate of the detection model. The proposed method’s performance is validated using the IPIX dataset. The main contributions of this paper can be summarized as follows:

- (1)

- A deep unfolding method for detecting small targets over the sea surface based on OTFS modulation is proposed. By transforming signals from the time domain to the DD domain, this approach effectively enhances the sparsity of target signals while reducing interference from sea clutter. The deep unfolding technique embeds the FISTA iterative process into a trainable network architecture, enabling adaptive parameter optimization that significantly improves detection accuracy and real-time performance.

- (2)

- A deep unfolding network architecture based on a dual attention mechanism with tensor modeling has been constructed. By incorporating tensors and CBAM, this approach adaptively enhances the response of key features in both spatial and channel dimensions, thereby effectively improving the discrimination capability of weak targets in complex sea conditions.

- (3)

- Stable detection performance is achieved across multiple polarization modes. This approach overcomes the detection limitations of traditional methods under low signal-to-noise ratio conditions. Experimental results demonstrate that on the IPIX dataset, the average detection rate across four polarization modes reaches 88.3%, with a peak of 91.5%, showcasing strong robustness and reliability.

- (4)

- This approach provides a lightweight solution for real-time maritime monitoring. Through joint optimization of sparse feature extraction and classification decision-making, the proposed method not only effectively enhances detection accuracy for small maritime targets but also offers technical support for intelligent maritime radar systems, demonstrating strong practical application potential.

2. The Theoretical Basis of Data Processing

In practical maritime radar detection scenarios, distinguishing small targets from sea clutter is fundamentally formulated as a binary decision problem. This process relies on discriminative features capable of separating target echoes from background clutter reflections [12]. Consequently, the signal received by the radar is evaluated under two mutually exclusive hypotheses, denoted as and .

where the hypothesis is the echo signal contains only sea clutter, the hypothesis is the echo signal contains target echoes. , , and are the radar echo, sea clutter, and target echo of the target unit under detection, respectively. and are the radar echo and sea clutter of the reference unit, respectively.

2.1. Channel Estimation as Sparse Recovery

A key challenge in detecting weak targets against maritime clutter is accurately estimating the propagation channel through which radar echo signals travel. Traditional methods based on least squares (LS) [13] or minimum mean square error (MMSE) [14] struggle to yield effective estimates under low signal-to-noise ratio and strong clutter conditions. To address this, we transform the channel estimation problem into a sparse signal recovery problem in the delay-Doppler domain.

In OTFS modulation, the signal is mapped from the time-frequency domain to the DD domain, exhibiting favorable structural and sparsity characteristics. Let the received signal be and the sparse channel vector to be estimated be . The sparse observation model can then be formulated as follows:

where A is the measurement matrix and n is additive Gaussian white noise.

2.2. Delay-Doppler Signal Mapping via OTFS

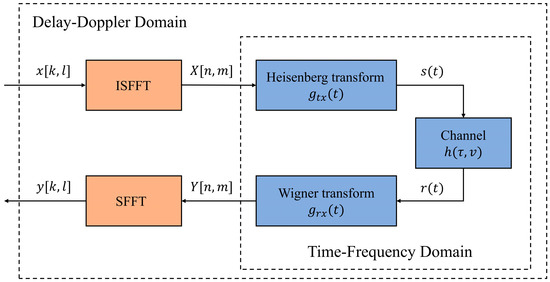

Orthogonal Time-Frequency Space modulation is represented primarily in the delay-Doppler domain, making it well-suited for characterizing sparse structures in rapidly time-varying sea surface channels [15]. Compared to traditional time-frequency modulation, OTFS enhances the separability of target echoes and clutter by unfolding them in the DD domain, thereby improving weak small target detection. OTFS comprises three key stages: transmitter modulation, channel propagation, and receiver demodulation. Assuming each OTFS frame contains time symbols and frequency subcarriers, the system bandwidth is , and the frame duration is , where represents the duration of each symbol and is the subcarrier spacing, satisfying the orthogonality condition . Figure 1 shows the OTFS system flowchart. The specific steps are as follows:

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the OTFS system.

During the transmitter modulation process, the DD-domain signal undergoes a two-dimensional Inverse Symplectic Finite Fourier Transform (ISFFT) to convert it into a time-frequency domain signal. Each data symbol represents a point in the th Doppler and th delay dimensions, corresponding to the OTFS grid :

Next, perform the ISFFT to obtain the time-frequency domain signal :

where n and m represent the time and frequency indices, respectively, the time-frequency domain signal undergoes a Heisenberg transform, mapping X[n,m] through the modulation pulse g_tx (t) to the continuous-time domain signal s(t):

During channel propagation, assuming a time-varying channel possesses paths, the channel can be expressed as:

where , , and denote the channel gain, delay, and Doppler shift of th path, respectively. Here, , , and represents fractional Doppler. After transmission through the channel, the received signal is obtained:

where n(t) is Gaussian additive noise.

During reception demodulation, the received signal first undergoes Wigner transformation and matched filtering using the same shaping filter as the transmitter, yielding the time-frequency domain signal :

Subsequently, is converted back to the DD domain via the Sinusoidal Fast Fourier Transform (SFFT):

From the above formula, it can be seen that the core operation of OTFS is a two-dimensional FFT, whose computational complexity is:

2.3. Group-Sparsity Regularization and FISTA Iterations

In maritime noise environments, received signals exhibit characteristics such as strong interference backgrounds and significant frequency dispersion, leading to poor performance of traditional linear estimation methods in channel recovery [16]. To address this issue, FISTA is employed for channel estimation. FISTA combines gradient descent with momentum acceleration, accelerating sparse recovery convergence while maintaining reconstruction accuracy. This approach effectively handles high sparsity rates and strong noise environments [17], facilitating sparse target extraction from maritime clutter signals. Considering the local clustering of target and clutter energy on the delay-Doppler grid, we introduce group sparsity priors: the target vector is partitioned into groups based on adjacent DD cells, and regularization is applied to impose structural constraints. This method ensures smoother signals within groups and sparser signals between groups, better reflecting the true distribution patterns of sea clutter and target echoes in the DD domain. Based on the above setup, the channel estimation problem can be transformed into the following optimization model:

where is the observed data, is the measurement matrix, is the regularization parameter, is the optional group weight (default ), and denotes the th subvector after partitioning. During algorithm initialization, the shrinkage coefficient is set to 1. At iteration , updates proceed as follows:

First, auxiliary variables are constructed using the results from the previous two iterations:

where is the momentum coefficient, defined as . This extrapolation utilizes historical directions to enhance convergence speed and suppress oscillations. is the shrinkage coefficient, updated as follows:

Next, gradient correction is applied using the current momentum estimate , performing one step along the gradient of the least-squares term at to obtain intermediate variables:

where is the gradient step size parameter. satisfies , where is the Lipschitz constant of the smoothing term. To enhance the group sparsity of the signal, is partitioned into according to a predefined group set . A group soft-thresholding near-end mapping is applied to each group, yielding the update:

where denotes the non-negative part. When , the entire group is set to zero to achieve inter-group sparsity. When , the group is proportionally shrunk to preserve intra-group structure, thereby achieving intra-group smoothness and inter-group sparsity. Iteration terminates upon meeting the stopping condition. By repeatedly performing momentum accumulation, gradient correction, and soft threshold updates, the objective function value is progressively optimized.

Although the FISTA framework enables effective sparse recovery, its performance in practical applications heavily depends on the proper tuning of key parameters. Traditional methods typically rely on empirical adjustments or manual parameter settings, resulting in limited generalization capabilities and unstable performance across different environments.

2.4. GAN-Based Adversarial Adaptation and Attention

Generative Adversarial Networks consist of a generator and a discriminator. Through adversarial training, the generator approximates the true distribution at the feature level, while the discriminator provides feedback on distinguishability, thereby continuously enhancing feature modeling capabilities during the game process [18]. To ensure stability in adversarial learning, this work employs the WGAN-GP objective in Phase I. By implementing gradient penalties to approximate a 1-Lipschitz constraint, it promotes the continuity and stability of generated feature distributions. In Phase II, addressing class imbalance in classification tasks, Lovasz-Softmax is adopted as an Intersection over Union (IoU) surrogate for the loss function. This method directly optimizes the decision boundary, enhancing the ability to distinguish minority target classes.

To further enhance feature modeling capabilities, a lightweight CBAM is introduced. By jointly modeling channel attention (CA) and spatial attention (SA), this module effectively boosts the network’s perception of key feature regions while suppressing redundant background noise, with only a moderate increase in computational overhead [19].

In summary, GAN provides distribution alignment and robust discrimination, while CBAM offers feature enhancement. When integrated into the expanded FISTA framework, they strengthen feature quality during sparse recovery and highlight faint small objects during classification, significantly improving detection performance against maritime clutter.

The CBAM consists of two components: channel attention and spatial attention. In the channel attention mechanism, the input feature map undergoes global average pooling and max pooling to yield two channel descriptor vectors and . These are processed through a shared multi-layer perceptron (MLP), summed, and then passed through a Sigmoid activation function to obtain the channel attention weights:

where denotes the Sigmoid function. The resulting weights are applied to the original input feature map for channel-wise weighting, yielding:

where denotes element-wise multiplication. The primary computational overhead of CA arises from two global pooling operations, the sharing of two-layer MLP networks, and per-channel weighting of feature maps. Its computational complexity is as follows:

where denotes the compression ratio. The spatial attention mechanism then proceeds as follows: First, perform average pooling and max pooling on along the channel dimension, yielding two spatial descriptor maps and . These are concatenated along the channel dimension and fed into a convolution operation. After passing through the Sigmoid activation function, the spatial attention weights are obtained:

where denotes channel concatenation. The primary computational overhead of SA comprises two channel pooling operations and one convolution operation with two channels, whose computational complexity is:

These weights are applied to the channel-weighted feature map to yield the final output:

The overall computational complexity of CBAM can then be determined as:

This CBAM spans both generator and discriminator, dynamically enhancing responses in critical regions to effectively improve the model’s ability to distinguish sparse targets from interference noise.

In the first-stage channel recovery task, WGAN-GP is adopted as the training objective to enhance the continuity and distribution stability of generated results. Let the generator be denoted as and the discriminator as , where and represent their respective sets of learnable parameters. The loss function for the discriminator is defined as:

where is the reconstructed channel output by the generator, is the true sparse channel sample, and is the random linear interpolation sample, with . is the gradient penalty weight, used to approximate the 1-Lipschitz constraint and enhance training stability. The generator aims to minimize the following loss:

After channel estimation, the second stage involves feature classification. Considering the class imbalance between sea clutter and sparse targets, the Lovasz-Softmax Loss is adopted as the primary loss function to enhance small target discrimination. Let the model output prediction probabilities be , corresponding to the true labels . The Lovasz-Softmax Loss can be expressed as:

where is the IoU gradient weight for ranking errors, emphasizing the contribution of boundary regions and minority samples to the overall IoU to highlight error contributions in marginal areas.

2.5. Statistical Significance Analysis Method

When comparing the performance of multiple algorithms across different datasets, merely contrasting average performance metrics is insufficient to demonstrate the statistical significance of algorithmic superiority. To scientifically quantify whether performance differences stem from inherent algorithmic properties rather than random factors, formal statistical significance testing is required [20]. This study employs the non-parametric Friedman Test followed by the Nemenyi Post-hoc Test, with the core procedure outlined as follows:

Consider algorithms undergoing performance comparison across datasets, with each algorithm yielding a performance metric on each dataset. First, rank the algorithm performance on each dataset to obtain the rank for each algorithm on that dataset, where and . The Friedman test assesses whether significant differences exist between algorithms based on the mean of these ranks, with its statistic defined as:

where denotes the average rank of the -th algorithm. Should Friedman’s test reject the null hypothesis that ‘all algorithms perform identically’, the Nemenyi test is subsequently employed for pairwise comparisons to identify algorithms exhibiting significant differences. The critical difference (CD) for the Nemenyi test is defined as:

where denotes the critical value of the studentized range distribution at significance level . If the mean rank difference exceeds for two algorithms, a significant difference is deemed to exist at significance level .

3. Tensor-FISTA-Net Architecture and Optimization for Small Target Detection

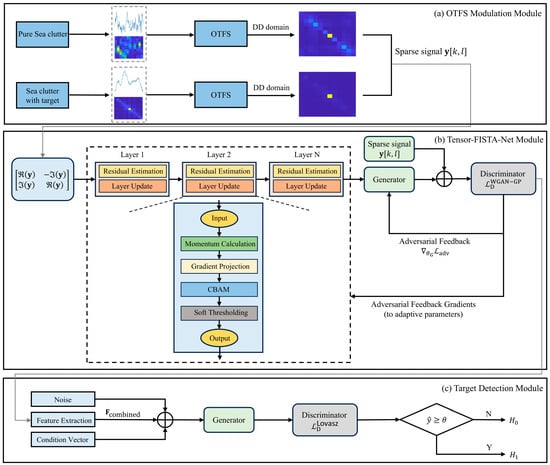

To address the challenging task of detecting small targets in maritime clutter, the proposed OTFS-FISTA-Net framework enhances signals using OTFS modulation techniques. It then employs Tensor-FISTA-Net based on deep unfolding for sparse recovery, and finally achieves high-precision small target detection through a GAN-based detection and classification module. The overall flowchart is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The overall flowchart of the OTFS-FISTA-Net.

After OTFS modulation, the processed signal is mapped to the DD domain, thereby enhancing its sparsity. Subsequently, the sparse signal passes through the Tensor-FISTA-Net module, which applies FISTA to perform multi-layer unfolding, executing residual estimation and layer updates. The sparse signal is continuously optimized through momentum calculation, gradient projection, and soft thresholding. Concurrently, CBAM is introduced to help the model focus on key spatial and channel features, thereby improving object detection performance. After signal processing, the generator optimizes the sparse estimates within the GAN framework. The discriminator then compares the generated sparse signals with real samples using the WGAN-GP loss function. Discriminator feedback updates generator parameters to further refine sparse signal estimation accuracy. Simultaneously, discriminator parameters are updated based on adversarial gradients, enhancing its ability to distinguish real from generated signals. This adversarial process ensures robustness in sparse recovery and improves the model’s capability to detect small targets in complex maritime clutter environments.

In the signal processed by Tensor-FISTA-Net, sparsity features and energy distribution features are first extracted. Sparsity features reflect the structured sparsity of the signal in both the time and frequency domains, while energy distribution features reveal the local energy concentration of the target signal, aiding in distinguishing targets from noise. Subsequently, a conditional vector is generated by incorporating environmental parameters and concatenated with the extracted features as input to the generator. The generator optimizes sparse signal estimation, enhancing target signals while suppressing noise. The processed signal is evaluated by the discriminator using the Lovasz-Softmax loss function to distinguish targets from noise. Feedback from the discriminator updates the generator parameters, further improving signal recovery performance. Finally, the signal is compared against a dynamically adjusted decision threshold. Signals exceeding the threshold are classified as targets (), while those below are classified as clutter (), ensuring efficient target detection and false alarm suppression.

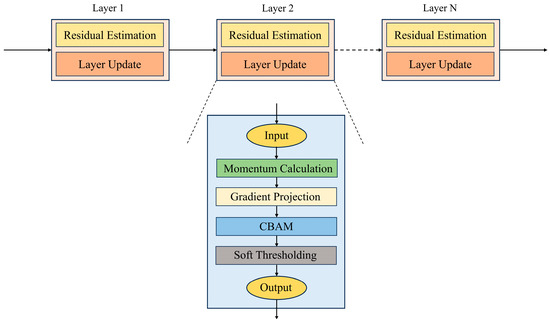

3.1. Architecture of Tensor-FISTA-Net

3.1.1. FISTA Unrolling and Proximal Mapping

To effectively address the complex structure where abundant interference noise and sparse targets coexist within maritime clutter signals, a deep unfolding network based on the FISTA iterative mechanism is constructed. The Tensor-FISTA-Net architecture [21] is introduced to transform the channel estimation problem into a sparse signal recovery problem. The specific flowchart is illustrated in Figure 3. Traditional point-by-point modeling approaches struggle to simultaneously capture joint characteristics in both the Doppler and delay domains. Therefore, a tensor representation is adopted for joint modeling and processing of DD-domain received signals.

Figure 3.

Flowchart of the FISTA iteration mechanism.

The OTFS receiver restores the received time-frequency domain signal to the DD domain via SFFT, yielding the complex-form received symbol . Its real and imaginary parts are concatenated to form the tensor input:

where and denote the real and imaginary parts of a complex number, respectively. represents the concatenation of real and imaginary parts of the complex tensor, i.e., is a tensor. Expand the FISTA iterative formula across each network layer, incorporating a momentum mechanism with momentum coefficient to accelerate convergence. Construct momentum estimates using historical outputs to update the current layer state. Compute updated feature maps via residual back projection:

where denotes the sparse mapping matrix based on the DD domain in the OTFS system, represents its Hermitian conjugate, and denotes the learnable step size for layer .

Introducing the GAN framework, the generator refines the sparse estimation results, while the provides adversarial supervision by scoring both real and generated samples, defined as:

where and denote the discriminator’s scores for real and generated samples, respectively, this establishes an adversarial game between generator parameters and discriminator parameters . The former continuously updates via feedback gradients to enhance sparsity estimation, while the latter improves the ability to distinguish genuine from fabricated samples. CBAM applies attention-weighted pooling to feature maps , yielding enhanced feature maps:

where denotes the CBAM channel-space enhancement factor, inputting into the generator subnetwork extracts local sparse structures and applies nonlinear mapping. The output undergoes sparse contraction via the soft function to yield the next layer’s estimation:

where is the learnable threshold parameter for layer , and is the learnable parameter set of the generator. A two-stage loss function design is introduced during training, denoted as and . The final total loss function is expressed as:

where is the weighting coefficient balancing the two stages, the gradient update formulas for the generator and discriminator are further derived, with their feedback gradient equations defined as:

where denotes the adversarial loss of the generator, guiding it to approximate the true distribution continuously. The discriminator counters this by enhancing its ability to distinguish between real and fake samples, thereby establishing a dynamic adversarial interaction during training. After layers of depth unfolding, the output sparse estimate is utilized for subsequent discriminative classification analysis. To enhance the sparsity control of the final output, the network incorporates a soft thresholding function at the terminal layer for soft thresholding contraction:

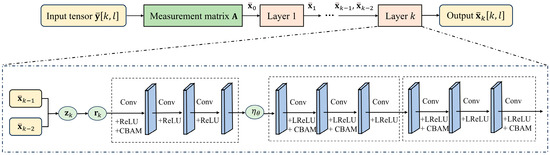

where the is the sign function preserving element polarity, and is the learnable contraction threshold. The specific flowchart is illustrated in Figure 4. The final channel estimation result is output as:

Figure 4.

Flowchart of the Tensor-FISTA-Net iteration mechanism.

This sparse estimate is utilized for subsequent feature extraction tasks. The computational complexity of the residual back projection can be expressed as:

where and denote the linear operator and its adjoint, respectively. Within the Tensor-FISTA-Net architecture, the convolutional operations in the generator subnetwork bear the primary computational burden, while the matrix operations in residual backprojection constitute a secondary overhead. Additional computational costs arise from CBAM, momentum updates, and soft thresholding operations, the overall computational complexity is expressed as:

where denotes the number of unfolded layers, and represent the output spatial dimensions of the l-th layer in the generator, and denote the input and output channel counts of the generator, and is the kernel edge length. In this architecture, the parameters and in CBAM’s Formula (22) are replaced with and . The computational complexity of the momentum update component is , while that of the soft thresholding contraction component is also .

3.1.2. GAN Module Configuration and Training

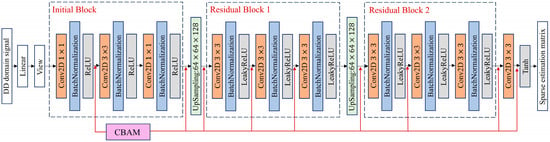

To enhance the generation capability of sparse channel matrices, the generator network architecture is designed based on the Tensor-FISTA-Net expansion form. The generator’s expanded structure and parameter configuration are shown in Figure 5 and Table 1. The front layers of the network incorporate OTFS-modulated sparse structures and adopt tensor modeling to enhance high-dimensional representation capabilities. First, the CBAM mechanism is introduced after shallow convolutional modules to enhance channel and spatial responses in critical regions adaptively. Subsequently, nonlinear enhancement is achieved through the ReLU activation function, which increases the network’s expressive power while preserving feature sparsity and effectively mitigating gradient vanishing issues [22]. The formula is:

Figure 5.

Generator unfolded structure.

Table 1.

Generator unfolded structure and parameter configuration.

Next, LeakyReLU is applied to the intermediate convolutional layers to prevent vanishing gradients and permit non-zero gradients in negative value regions, thereby enhancing the network’s learning capability. The formula is:

where controls the contribution from negative value regions. Finally, the Tanh activation function is applied to the generator’s output layer to compress the output range, constraining it within for generating sparse estimation matrices. Its formula is:

The discriminator employs a fully convolutional network architecture from shallow to deep layers, taking as input the sparse channel matrix output by the generator. The first layer of the discriminator uses a convolutional kernel with a stride of 1 to extract initial local features. Subsequent layers progressively increase the number of channels while reducing the spatial dimensions. A LeakyReLU activation function follows each convolutional layer to enhance training stability. The network comprises five convolutional modules with output channels of 64, 128, 256, 512, and 1, respectively. After global average pooling, a sigmoid function outputs probability values between to assess the authenticity of the input matrix. During training, WGAN-GP is employed as the discriminator loss function, with alternating updates between the generator and discriminator. After multiple training iterations, the shared learning rate for both generator and discriminator is set to 0.0005, with 1000 training iterations and a batch size of 16.

The primary computational overhead in GANs stems from the convolutional layers of the generator and discriminator. By summing the computational complexity for each convolutional layer based on the output space dimensions, input and output channels, and kernel size, the overall computational complexity is:

The summation is performed across all convolutional layers of both the generator and the discriminator .

3.2. Sparse Recovery and Feature Extraction

After completing channel sparse recovery, feature extraction is required for the recovered results. We design feature evaluation metrics from two dimensions: sparsity features and energy distribution features. For sparsity features, extraction is performed from both time-domain and frequency-domain perspectives. In the time domain, the variance of the autocorrelation function is introduced to measure signal stability and periodicity. In the frequency domain, the norm is employed to analyze the block sparsity of sea clutter signals. Concurrently, energy distribution features further characterize the local energy concentration of target signals, enhancing the system’s ability to distinguish between clutter and targets.

- (1)

- Sparsity Features

The autocorrelation function reflects signal similarity under time delay. Target echoes exhibit relatively stable periodic structures, whereas sea clutter is more random and divergent. Based on this characteristic, the autocorrelation function at delay is defined as:

Its variance is then extracted as a feature indicator:

Target echoes typically concentrate in the DD domain, whereas sea clutter exhibits a broader dispersion. Therefore, the norm is introduced to analyze frequency-domain sparsity. Let denote the matrix formed by . Its norm is defined as:

This norm effectively characterizes sparsity across different Doppler or time-delay channels, with tighter block structures yielding smaller norms. An adaptive weighting fusion mechanism is introduced, where the generator module in the GAN automatically learns fusion weights . The final sparsity feature is defined as:

- (2)

- Energy Distribution Feature

Beyond sparsity, target echoes exhibit more pronounced local energy concentration in the DD domain. In contrast, sea clutter energy displays a smooth, diffuse distribution. Therefore, an energy distribution feature is introduced as a complementary metric. First, total energy is defined:

Next, we compute the normalized energy probability distribution of the signal in the DD domain, then define energy entropy to characterize the dispersion of energy distribution:

Finally, the fused sparsity metric and energy entropy form a two-dimensional feature vector:

This feature vector is input into a discriminator, combined with the Lovasz-Softmax loss function, to achieve more stable discrimination between target echoes and sea clutter signals under class imbalance conditions.

3.3. False Alarm Control

In radar signal processing and target detection, the false alarm rate is a critical metric. By appropriately controlling the false alarm rate , system real-time performance and efficiency can be enhanced [23]. Set a desired false alarm rate , and adjust by finding the threshold closest to this desired rate:

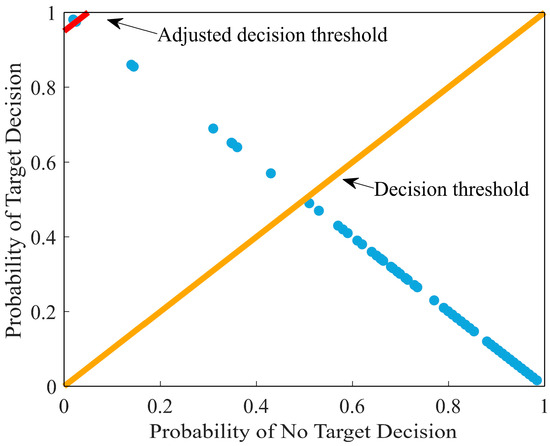

Based on the calculated optimal threshold , perform final classification on the test set. If , the echo is judged as non-target, corresponding to the null hypothesis . If , the echo is judged as target, corresponding to the alternative hypothesis . Updating the threshold θ effectively controls the false alarm rate, enabling fine-grained control over classification performance. The specific process is illustrated in Figure 6. Once the false alarm rate reaches the predetermined target value during this process, the detection system achieves the desired performance level.

Figure 6.

Judgment threshold adjustment process.

Figure 6 illustrates the specific process of adjusting the decision threshold. When , the number of false alarm points is 10, corresponding to a false alarm rate of 0.81%. To achieve a false alarm rate of , further threshold adjustment is required, ultimately reaching , at which point only one false alarm point remains. This threshold adjustment process effectively reduces false alarms while maintaining high detection accuracy. Under the adjusted threshold conditions, the system’s false alarm rate is significantly reduced, and classification accuracy is markedly improved. By dynamically adjusting the threshold, we can maintain robust classification performance across different false alarm rate scenarios.

Furthermore, considering the significant variation in background power (i.e., the total power of sea clutter and noise) across different sea conditions [24], we have incorporated a dynamic adjustment mechanism into our threshold setting. Specifically, within each processing unit, background power estimation is first performed on echoes from target-free regions to obtain their total variance . Subsequently, based on the preset false alarm probability , the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the background distribution is utilised to calculate the dynamic threshold:

where denotes the inverse cumulative distribution function of the background distribution. In this manner, the threshold dynamically adjusts to variations in background power levels, thereby maintaining a constant false alarm rate across different environments.

4. Experiments and Performance Analyses

In this experiment, we utilized actual sea clutter data from the IPIX radar database [25], provided by McMaster University and publicly accessible, as shown in Table 2. The data were acquired in the nearshore environment of Dartmouth, Canada, during 1993 and 1998. The radar was mounted on a fixed platform at a height of 30 m, observing the sea surface at a low incidence angle. The dataset encompasses a range of typical sea conditions, including wind speeds of 9–33 km/h and significant wave heights of 0.7–2.2 m. Measurements were taken for a spherical buoy with a diameter of 1 m, representing a typical small, faint sea surface target. Operating at 9.39 GHz within the X-band, the dataset comprises 20 data sets. Each set encompasses 14 range bins, with each bin containing 131,072 pulses, and employs four polarization modes: HH, HV, VH and VV.

Table 2.

Information on IPIX radar data.

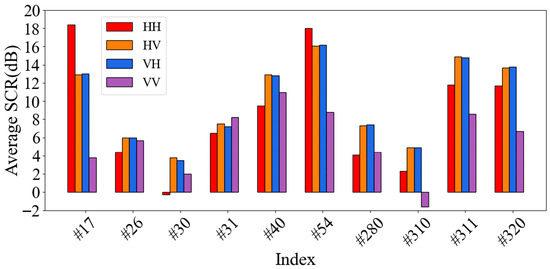

Significant variations in the signal-to-clutter ratio (SCR) exist between different data sets within the IPIX dataset. Figure 7 shows the average SCR across the first 10 data sets for all four polarization modes. Sea state conditions, polarization mode, and target echo characteristics primarily influence these variations. Analysis of sea clutter data in Reference [26] indicates that cross-polarization achieves a higher average SCR than main polarization, yielding superior target detection performance. This phenomenon occurs because the cross-polarization’s greater effectiveness in suppressing sea clutter, thereby enhancing SCR and detection rates. This characteristic is particularly pronounced in datasets #54, #311, and #320. Simultaneously, VV polarization generates greater Bragg scattering than HH polarization, resulting in a lower average signal-to-noise ratio for VV polarization.

Figure 7.

ASCR of data in four polarization modes.

All experiments were conducted on servers equipped with NVIDIA RTX 5070 GPUs and implemented using the PyTorch (Version 2.0.1) framework. Core hyperparameters were determined via grid search: the network expansion depth was set to , the optimiser employed Adam [27] with an initial learning rate of , and a cosine annealing scheduler was used for decay with momentum parameters . The batch size was set to 16, with a total of 1000 training iterations. The weighting factor for the loss function and the gradient penalty coefficient were set to 1.0 and 10, respectively. The dataset was partitioned into training, validation, and test sets in a 7:2:1 ratio.

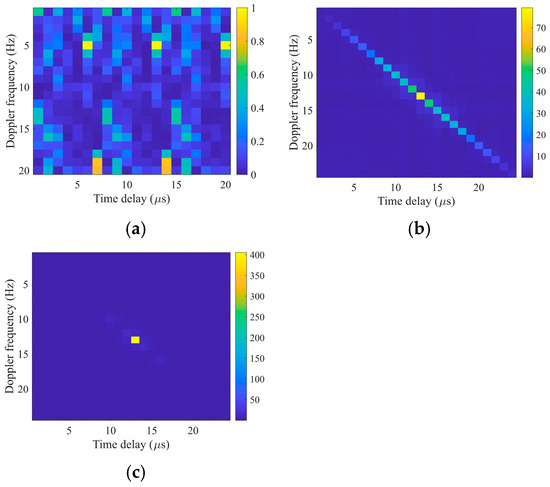

4.1. Sparse Recovery Performance Evaluation

To validate the enhanced signal sparsity and clutter suppression capabilities of OTFS modulation, we compared the structural differences between signals before and after OTFS modulation, as shown in Figure 8. Figure 8a displays the heatmap of the raw signal, revealing a highly random energy distribution with severe target-clutter overlap. Figure 8b and Figure 8c present the sparse structure heatmaps of signals mapped to the DD domain via OTFS, under scenarios with and without target echoes, respectively. Compared to the original time-domain signals, both exhibit more ordered sparse distributions. Furthermore, Figure 8b corresponds to a scenario containing only clutter, where the overall energy distribution is relatively dispersed, background clutter is prominent, and sparsity is acceptable but does not form a distinct focal structure. In contrast, Figure 8c depicts the scenario with a target present, showing high-intensity energy peaks while maintaining excellent sparsity in the background regions with almost no clutter interference.

Figure 8.

Structural differences between signals before and after OTFS modulation. (a) The original signal; (b) The signal without target; (c) The signal with target.

This demonstrates that OTFS modulation effectively enhances signal sparsity while better suppressing background noise, thereby providing robust support for target detection. Comparing sparsity distributions across these scenarios reveals that OTFS-modulated signals significantly outperform traditional methods in noisy environments. Particularly under strong noise conditions, background noise impact is effectively suppressed, further enhancing target detection robustness.

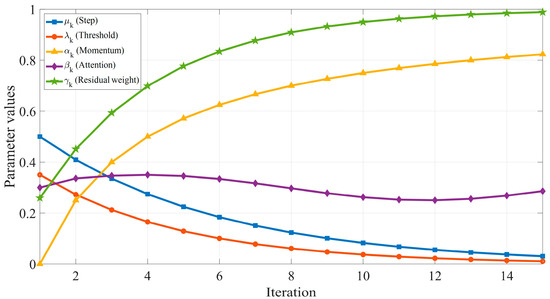

An OTFS-FISTA-Net exhibits dynamic adjustment capabilities during sparse reconstruction. Figure 9 illustrates the trend of five key parameter values across iterative layers. It can be observed that parameters undergo rapid adjustment in the initial stages before gradually stabilizing, demonstrating the network’s strong adaptive optimization capability. This iterative adjustment mechanism not only preserves the fast convergence characteristic of the traditional FISTA but also achieves inter-layer parameter differentiation through end-to-end training. This fully illustrates the advantages of OTFS-FISTA-Net in dynamic sparse representation and structural adaptive adjustment.

Figure 9.

Trend of five key parameter values across iteration layers.

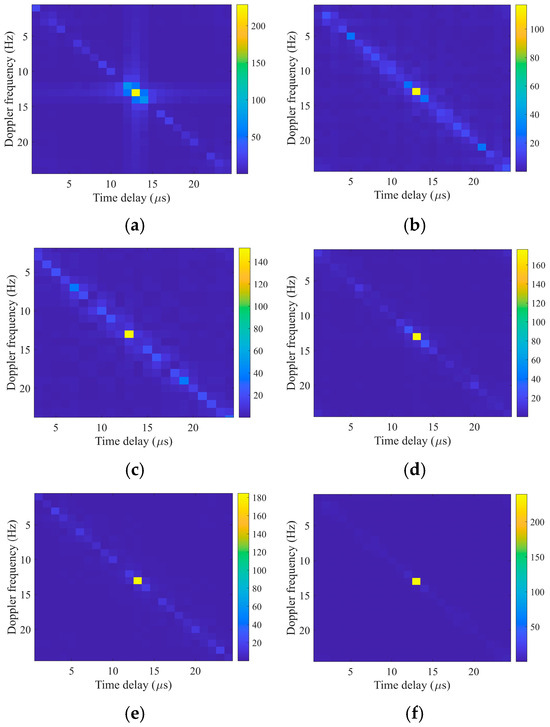

To further validate the sparse reconstruction capability of the proposed method at different iteration stages, experiment #280 from the IPIX dataset with a signal-to-interference ratio of 4.0 dB was selected. The DD-domain reconstruction results of OTFS-FISTA-Net at varying iteration layers are plotted in Figure 10. The figure displays reconstructions of the original signal, as well as those from the 3rd, 6th, 9th, 12th, and 15th layers.

Figure 10.

DD-domain reconstruction results of OTFS-FISTA-Net at different iteration levels. (a) The original signal; (b) The 3rd layer; (c) The 6th layer; (d) The 9th layer; (e) The 12th layer; (f) The 15th layer.

As shown in the figure, the sparsity of the signal gradually increases with the number of network layers. Specifically, the original signal image exhibits a relatively blurred noise distribution, with the target signal’s energy spread out and the background noise being quite prominent. At the third layer, sparsity improves slightly, and the target signal begins to concentrate somewhat, though background noise remains noticeable. As the number of layers increases from the 6th to the 15th layer, the sparsity of the signal progressively improves. Particularly at the 15th layer, the target signal is almost entirely concentrated, background noise is significantly suppressed, and the signal’s energy peaks become more pronounced, revealing a cleaner and more focused sparse structure.

These results demonstrate that through layer-by-layer training, OTFS-FISTA-Net effectively extracts target signals from complex sea clutter environments while suppressing background noise, significantly enhancing signal sparsity and reconstruction accuracy.

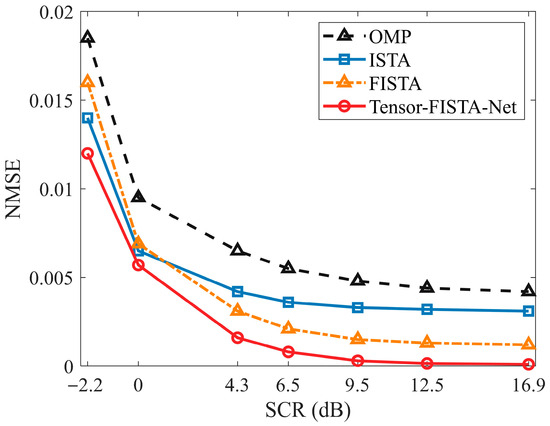

To visually demonstrate the performance differences between the proposed method and other algorithms under varying SCR, a quantitative analysis of correlation error was conducted for OMP, ISTA, FISTA, and OTFS-FISTA-Net across multiple representative SCR conditions. Corresponding normalized mean square error (NMSE) curves were plotted. The NMSE is calculated as:

where denotes the estimated channel value for the th channel, and denotes the true channel value for the th channel. As shown in Figure 11, the OMP method exhibits an NMSE of approximately 0.018 at , while OTFS-FISTA-Net reduces this to about 0.012 under the same conditions. As SCR increases, the errors of all four methods gradually decrease. However, OTFS-FISTA-Net consistently maintains optimal performance, with its NMSE dropping to 0.0006 at , it is significantly lower than FISTA and ISTA. This demonstrates the method’s superior accuracy and stability across both high and low signal-to-noise ratio conditions.

Figure 11.

NMSE curves for different methods.

4.2. Feature Separability and Visualization

This section constructs two-dimensional feature vectors based on sparsity and energy distribution, and introduces multiple classification evaluation metrics to assess the features quantitatively. Specifically, Target Classification Accuracy (TA), F1-score, and Mean IoU (mIoU) are adopted as core evaluation metrics, with their calculation formulas as follows:

where TP (True Positives) denotes the number of actual target echoes correctly predicted as targets, TN (True Negatives) denotes the number of actual sea clutter bands correctly predicted as sea clutter, FP (False Positives) denotes the number of actual sea clutter bands incorrectly classified as target echoes, FN (False Negatives) denotes the number of actual target echoes incorrectly classified as sea clutter, , .

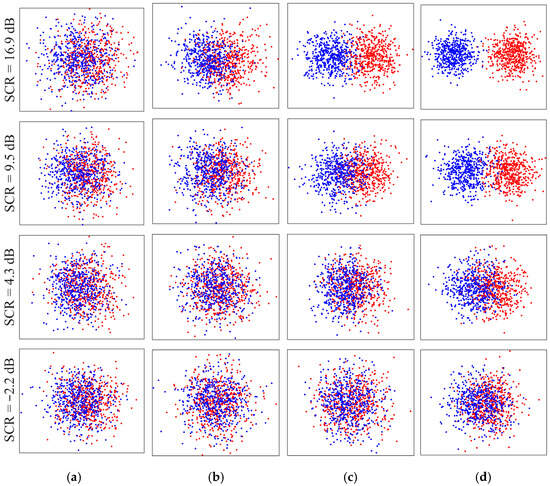

To validate the proposed method’s feature discrimination capability and visualization performance under varying SCR levels, Figure 12 displays the two-dimensional feature distribution maps extracted by the proposed method and three alternative approaches at four typical SCR levels. Each row corresponds to a fixed SCR level, presenting scatter plots from left to right for OMP, ISTA, FISTA, and OTFS-FISTA-Net, respectively. Red and blue points represent target and background features, respectively. These SCR values cover practical scenarios under high, medium, low, and extremely low signal-to-noise conditions, comprehensively reflecting how feature separability varies across methods under complex interference. The visualization reveals that feature separation progressively strengthens as SCR increases. Specifically, at , the feature distribution extracted by the OTFS-FISTA-Net method exhibits the strongest separability, forming a distinct boundary between the two classes. Conversely, under low SNR conditions (), the class boundaries become indistinct for all methods, with the OMP method barely distinguishing target from background features. Comprehensive comparison reveals that the OTFS-FISTA-Net method demonstrates more stable clustering structures and feature separation capabilities across different SCR levels.

Figure 12.

Scatter plots at different SCR levels. (a) OMP; (b) ISTA; (c) FISTA; (d) OTFS-FISTA-Net.

Next, we quantitatively compare the performance of four methods—OMP, FISTA, OTFS-FISTA-Net without an attention mechanism, and OTFS-FISTA-Net—under varying SCR conditions. Experiments were conducted using three scenarios from the dataset: #310 (), #40 (), and #54 (). Results are shown in Table 3, with bolded values indicating the highest metrics. The table reveals that traditional OMP and FISTA methods exhibit mediocre performance across metrics, particularly at , where mIoU values reach only 63.84% and 69.11%, respectively, indicating limited target extraction capability in complex backgrounds. While OTFS-FISTA-Net without attention mechanisms shows improvement, it still struggles to capture feature differences in critical target regions fully. In contrast, OTFS-FISTA-Net with CBAM achieves optimal performance across all metrics. Notably, at an SCR of 18 dB, it achieves 5.41% and 6.38% improvements in F1-score and mIoU, respectively. This demonstrates that the CBAM effectively enhances the network’s ability to focus on key feature regions, thereby boosting overall recognition performance.

Table 3.

Performance of four methods at different SCR levels.

4.3. Ablation Study Analysis

To verify the contribution of each module within the proposed OTFS-FISTA-Net to detection performance, this subsection designed systematic ablation experiments. By progressively introducing different modules, we analyzed their impact on overall detection capability. Experiments were conducted on the IPIX dataset, employing the average detection rate across four polarization modes as the core evaluation metric. Results are presented in Table 4. The experimental results for A1, A2, and A3 validate the overall effectiveness of the architecture progression from traditional optimization methods to deep unfolding networks. Meanwhile, the comparisons in A4, A5, and A6 evaluate the independent and combined effects of the attention mechanism and adversarial training. Finally, the A7 scheme demonstrates the optimal performance achievable by the complete method after incorporating dynamic threshold control.

Table 4.

Experimental results of ablation study.

4.4. Detection Performance Analysis

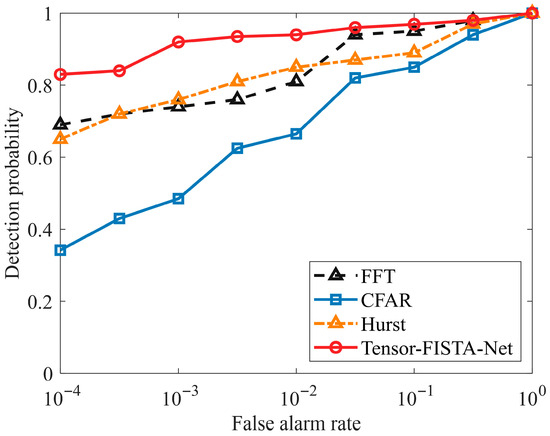

Figure 13 shows the detection rate curves of the proposed method versus the Fourier Transform (FFT), CFAR [28], and Hurst index [29] methods for dataset #54 under VH polarization, with false alarm rates ranging from 10−4 to 1. Overall, the proposed method outperforms the other methods across the entire false alarm rate range, maintaining a significant advantage even at low false alarm rates. At , the proposed method achieves a detection rate of 83.47%, representing an improvement of approximately 20.29% over the FFT method. This is because traditional methods exhibit limited detection capability at low false alarm rates, requiring greater false alarm trade-offs to enhance detection rates. Unlike traditional methods that exhibit significant fluctuations with false alarm rate, the detection rate curve of the proposed method remains stable, effectively avoiding overfitting or target misclassification.

Figure 13.

Detection rate curves of four methods.

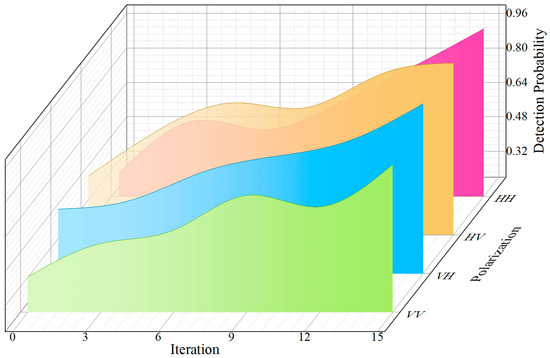

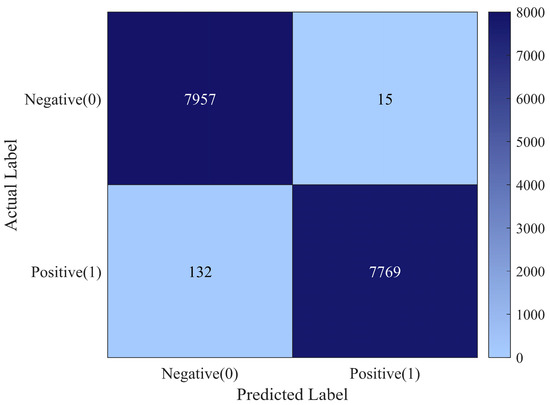

Further analysis reveals that the number of iteration layers in the network also significantly impacts detection performance. As shown in Figure 14, selecting dataset #54 with a false alarm rate of . For three scenarios with 6, 12, and 15 iterations, Tensor-FISTA-Net achieved average detection probabilities of 64.49%, 81.34%, and 96.31%, respectively. This yields two key conclusions. First, increasing iterations enhances the deep unfolding network’s ability to represent nonlinear mappings, improves sparse feature representation, and consequently boosts detection probability. Second, with fewer layers, the network’s fitting capability is insufficient, making it difficult for the model to capture complete structural features and limiting detection performance. Therefore, under a reasonable number of layers, Tensor-FISTA-Net achieves high-precision, high-robustness weak object detection by deeply unfolding the FISTA optimization process and integrating key modules. Under the same conditions, confusion matrices were calculated for 20 datasets, as shown in Figure 15. Among the test images, 7957 images were correctly classified as without target, while 15 images were incorrectly classified as containing targets. Conversely, 132 images were incorrectly classified as without a target, and 7769 images were correctly classified as containing targets. Calculated from this confusion matrix, OTFS-FISTA-Net achieves an overall detection accuracy of 98.97%.

Figure 14.

Detection probability at different iteration counts under 4 polarization states.

Figure 15.

Confusion matrix for 20 Datasets.

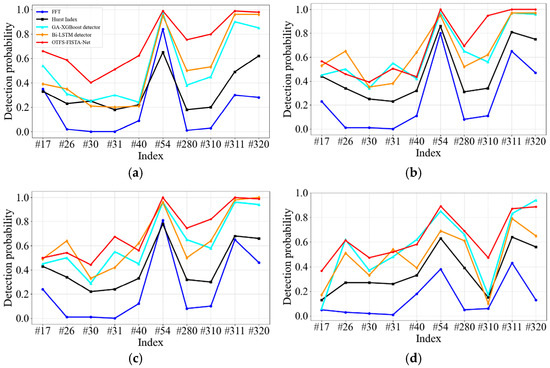

To validate the detection performance of the proposed algorithm, OTFS-FISTA-Net was compared with four other detection methods. Figure 16 shows the detection performance results of the five methods under four polarization conditions. The other four methods are the Fourier Transform, the Hurst Index, the GA-XGBoost detector [30], and the Bi-LSTM detector [31]. The observation time was set to 1.024 s, with a false alarm rate . As shown in Figure 10, under identical conditions, the average detection probabilities for the five methods were 20.53%, 43.53%, 70.75%, 84.25%, and 88.56%, respectively. It is evident that OTFS-FISTA-Net significantly outperforms other methods, maintaining high detection performance even under low-to-medium signal-to-noise ratios and highly sparse targets. This advantage stems primarily from its integration of tensor modeling and attention mechanisms, which effectively enhance the network’s ability to focus on and express key regional features, thereby improving target-background discrimination.

Figure 16.

Detection performance of five methods under four polarization modes. (a) HH; (b) HV; (c) VH; (d) VV.

Observation duration significantly impacts detection performance. Table 5 lists the average detection probability across 20 datasets for different detectors under three observation durations: 0.256 s, 0.512 s, and 1.024 s. Results indicate that the average detection probability of all detectors increases with extended observation time. Specifically, when observation time increases from 0.256 s to 0.512 s, the detection performance of the four detectors improves by 4.7%, 8.2%, 11.9%, and 14.0%, respectively. When observation time was extended from 0.512 s to 1.024 s, the detection performance of the four detectors improved by 12.8%, 7.9%, 6.1%, and 6.5%, respectively. These results indicate that, within a certain range, longer observation times help fully reveal the sparse structural characteristics of target signals and clutter in the DD domain. This enables more effective recovery of sparse target information and enhances detection accuracy. This fully demonstrates the advantages of the proposed method in complex sea clutter backgrounds.

Table 5.

Average detection probability for 20 datasets at different observation times.

4.5. Model Complexity and Efficiency Analysis

Experiments were conducted using dataset #54 from IPIX, with input consisting of 256 × 256 pixel single-channel grayscale images. U-Net [32], Dual-Stream Transformer [33], YOLOv5s [34], and the proposed OTFS-FISTA-Net were selected as comparison methods. The performance comparison results of each method are shown in Table 6. Detection accuracy is evaluated using mAP, model size is measured by the number of parameters (PA), computational complexity is characterized by floating-point operations (FLOPs), and the actual runtime efficiency of the models is analyzed by considering inference time. Experimental results demonstrate that OTFS-FISTA-Net achieves optimal detection accuracy while maintaining low computational complexity: its FLOPs are only 5.51 G, significantly lower than U-Net and YOLOv5; inference time is merely 0.52 ms, markedly superior to other comparison models. Furthermore, the network’s parameter count represents 26.9% of U-Net’s and 18.6% of YOLOv5’s, demonstrating its significant advantages in model lightweighting and inference efficiency.

Table 6.

Comparison of simulation results.

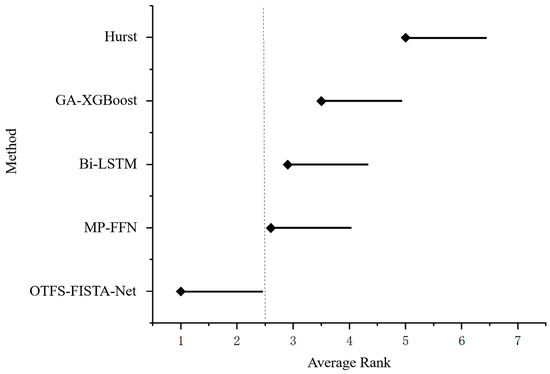

4.6. Statistical Significance Test

To thoroughly analyze the performance differences between the proposed method and other traditional approaches in target detection, this section employs Friedman’s test to examine significant variations among the methods. The observation time is set to 1.024 s, with a false alarm rate . The top 10 datasets in the dataset are selected for analysis, as the average detection probability of the bottom 10 datasets approaches the performance ceiling. This results in insufficient discrimination in detection performance, failing to effectively reflect significant differences between methods. Building upon the previous three detection methods, the MP-FFN method [35] based on deep multi-domain feature fusion is introduced as a key comparison target. Table 7 presents the detection probabilities (in percentage) of the five detection methods across the 10 datasets. The Average Rank (AR) column lists each method’s average rank across the datasets, where a lower rank indicates better performance.

Table 7.

Results of 5 detection methods over 10 datasets in terms of detection probability.

The Friedman test yielded a p-value of , which is significantly smaller than the significance level . This indicates that the performance differences among the five methods are statistically significant. Subsequently, we conducted a Nemenyi post hoc test and calculated the CD value as 1.52 using Formula (27), generating the CD diagram shown in Figure 17. In this diagram, the dotted line represents the CD value. If the AR of any two methods exceeds the length of this dotted line, it indicates a statistically significant difference between them. This diagram demonstrates that the proposed method exhibits significant differences compared to other methods.

Figure 17.

Critical difference diagram for 5 detection methods based on average rank.

4.7. Analysis Under the SDRDSP Dataset

This section utilizes the Yantai maritime observation dataset [36] provided by the Naval Aviation University’s “Sea-Detecting Radar Data-Sharing Program (SDRDSP),” as shown in Table 8. This dataset was acquired by two independently deployed SPPR50P solid-state power amplifier radars (HH and VV polarizations) operating in the X-band. It employs a combined pulse transmission scheme comprising sequential single-pulse T1, LFM pulse T2, and LFM pulse T3, with a pulse repetition frequency of 2000 Hz and a maximum range resolution of 6 m. During testing, the radar was configured in staring mode with a range of 6 nautical miles, targeting a steel light buoy positioned at 2.97 nautical miles. The proposed method was compared with the tri-feature detector [37] and the feature temporal detection method [38], as summarized in Table 9. Under identical pulse count conditions, the proposed method consistently achieved higher detection rates than the other two approaches, with particularly pronounced advantages in higher sea states and HH polarization mode. As the pulse count increased from 64 to 256, detection performance steadily improved across all methods, indicating that extended observation time enhances detection stability.

Table 8.

Information on SDRDSP radar data.

Table 9.

Average detection probability at different pulse counts.

5. Conclusions

To enhance detection capabilities for weak targets in complex maritime clutter backgrounds, this paper proposes a method based on OTFS modulation and deep unfolding via Tensor-FISTA-Net. First, the signal undergoes an OTFS transformation, mapping it from the time domain to the Delay-Doppler domain, thereby strengthening its sparse structure. Subsequently, a sparse recovery model is constructed in the DD domain. By unfolding the FISTA iteration into a trainable network architecture and incorporating GAN for adaptive parameter optimization, combined with tensor modeling and attention mechanisms, the approach enhances sparse feature representation while amplifying response to critical regions. Ultimately, a two-stage loss function design and false alarm rate control mechanism enable precise target echo identification and effective discrimination.

Systematic experiments were conducted on the IPIX dataset. Results demonstrate that: (1) Employing sparse representations in the DD domain and integrating discriminative features enables more effective discrimination between small weak targets and sea clutter compared to using only time-domain or time-frequency features alone. (2) Compared to baseline methods like FISTA and pure convolutional networks, Tensor-FISTA-Net achieves faster convergence and more stable performance through learnable iterations. Simultaneously, tensor parameters and CBAM jointly enhance the response to critical regions. (3) Under four polarization configurations, the introduction of GAN-based adaptive thresholding and false alarm control mechanisms yields more balanced detection results. The overall accuracy reaches 98.97%, with a high average detection probability while effectively suppressing false alarm rates. (4) In low signal-to-noise ratio scenarios, the method maintains a distinct advantage by leveraging sparse and approximately invariant channel representations obtained through OTFS mapping to the DD domain, demonstrating robust performance and strong generalization capabilities.

Future research can be improved in the following aspects: (1) Promote model lightweighting and real-time deployment. For resource-constrained scenarios such as land-based, shipborne, and unmanned platforms, simplify models to reduce parameter counts and computational latency, thereby constructing end-to-end engineering acceleration solutions. (2) Enhance noise and sea state adaptability. Incorporate self-supervised denoising and domain adaptation training mechanisms, combined with uncertainty estimation and adaptive threshold learning, to improve robustness in low signal-to-noise ratio scenarios and reduce reliance on labeled data. (3) Reduce dependence on observation duration. Optimize network architecture and initialization strategies to maintain a high detection probability even with limited observation time, thereby enhancing the practicality of real-time detection tasks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.B. and H.X.; methodology, X.B. and H.X.; software, X.B.; validation, X.B.; formal analysis, H.X.; resources, H.X.; data curation, X.B.; writing—original draft preparation, X.B.; writing—review and editing, H.X.; project administration, H.X.; funding acquisition, H.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 62171228.

Data Availability Statement

The data were downloaded from the following website: http://soma.ece.mcmaster.ca/ipix/index.html (accessed on 27 May 2021). The data were measured with the McMaster IPIX Radar, a fully coherent X-band radar, with advanced features such as dual transmit/receive polarization, frequency agility, and stare/surveillance mode.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Nantong Institute of Technology and Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology for supporting this research work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Das, N.; Hossain, M.S. Investigation of the Impact of Sea Conditions on the Sea Surface Reflectivity in Maritime Radar Sea Clutter Modeling. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Electrical, Computer and Communication Engineering (ECCE), Chittagong, Bangladesh, 23–25 February 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Jiang, M.; Wang, J. Analysis of Extendibility of Sea Clutter Model in High Sea States Based on Measured Data. In Proceedings of the 2022 3rd International Conference on Computer Vision, Image and Deep Learning & International Conference on Computer Engineering and Applications (CVIDL & ICCEA), Changchun, China, 20–22 May 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 140–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; Jia, J.; He, Y.; You, Y. Characteristic Description and Statistical Model-Based Method for Sea Clutter Modeling. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xing, H.; Hou, T. Sea Surface Floating Small-Target Detection Based on Dual-Feature Images and Improved MobileViT. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Nehorai, A. OFDM MIMO Radar With Mutual-Information Waveform Design for Low-Grazing Angle Tracking. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2010, 58, 3152–3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, X.; Ning, X. BER Analysis of Integrated WFRFT-OTFS Waveform Framework Over Static Multipath Channels. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2021, 25, 754–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.; Chen, J.; Bao, Z. Sea Clutter Suppression Method for Over-the-Horizon Radar with Short Coherent Integration Time Based on Compressed Sensing. J. Electron. Inf. Technol. 2017, 39, 945–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.-Y.; Yang, K.; Tong, F.; Tian, T. Compressed Sensing of Delay and Doppler Spreading in Underwater Acoustic Channels. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 36031–36038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Yao, J.; Tong, F. Impulsive Noise Estimation for Underwater Acoustic OFDM Communication Using Signal-Noise Separation and Distributed Compressed Sensing Methods. Alex. Eng. J. 2025, 122, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Hu, S.; Lang, S.; Guo, Y.; Liu, J. End-to-End Classification Network for Ice Sheet Subsurface Targets in Radar Imagery. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Du, M.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, J.; Li, W.; Li, K.; Zhao, F. FISTA-NET: Deep Algorithm Unrolling for Cerenkov Luminescence Tomography. In Proceedings of the 2023 45th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), Sydney, Australia, 24–27 July 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, R.; Xing, H.; Zhou, X. Sea-Surface Small Target Detection Based on Improved Markov Transition Fields. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, B.; Bernstein, D.S. Efficient Batch and Recursive Least Squares for Matrix Parameter Estimation. IEEE Control Syst. Lett. 2024, 8, 1403–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wei, Z.; Yang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, C.; Chen, S. Beyond MMSE: Rank-1 Subspace Channel Estimator for Massive MIMO Systems. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Luo, Y.; Liao, Y.; Ye, Y. TA-DD-TransNet: A CSI Feedback Method for Delay-Doppler Domain. Telecommun. Eng. 2025, 65, 653–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromal, C.J.; Datta, S. FISTA-NET: Compressed Sensing MRI Reconstruction Using Unrolled Iterative Networks. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 21st India Council International Conference (INDICON), Kharagpur, India, 19–21 December 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Xu, L.; Qu, K. An Improved Iterative Reduction FISTA-Barzilai-Borwein Algorithm for Large-Scale LASSO. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on New Trends in Computational Intelligence (NTCI), Qingdao, China, 3–5 November 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Gong, Y.; Li, J.; Lu, K. Land-Sea Clutter Image Enhancement and Detector Design for Sky-Wave Over-the-Horizon Radar. Acta Electron. Sin. 2024, 52, 4037–4047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q. YOLOv5-CBAM: A Small Object Detection Model Based on YOLOv5 and CBAM. In Proceedings of the 2024 6th International Conference on Robotics, Intelligent Control and Artificial Intelligence (RICAI), Nanjing, China, 6–8 December 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 618–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessmann, S.; Baesens, B.; Mues, C.; Pietsch, S. Benchmarking Classification Models for Software Defect Prediction: A Proposed Framework and Novel Findings. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2008, 34, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.-Y.; Huang, Q.; Han, X.; Wu, B.; Kong, L.; Walid, A.; Wang, X. Real-Time Decoding of Snapshot Compressive Imaging Using Tensor FISTA-Net. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 35, 13312–13326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, L.; Li, G.; Dong, H.; Zheng, C.; Xu, F.; Sun, F. Radardiff: Improving Sea Clutter Suppression Using Diffusion Models for Radar Images. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 14–19 April 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Z.; Bai, X.; Shui, P.; Xu, S. Small Target Detection in Sea Clutter based on Normalized Hurst Exponent and Phase Linearity Degree. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 6th International Conference on Signal and Image Processing (ICSIP), Xi’an, China, 9–11 July 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, S.; Rosenberg, L. Challenges in Radar Sea Clutter Modelling. IET Radar Sonar Navig. 2022, 16, 1403–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Ma, J.; Huang, P.; Xia, X.-G.; Chen, J.; Xi, P.; Liu, X. Multichannel Sea Clutter Modeling and Clutter Suppression Performance Analysis for Spaceborne Bistatic Surveillance Radar Systems. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5108424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, T.; Leung, H.; Litva, J.; Haykin, S. Fractal Characterisation of Sea-Scattered Signals and Detection of Sea-Surface Targets. IEE Proc. F Radar Signal Process. 1993, 140, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. arXiv 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, M.A.; Barkat, M.; Aıssa, B.; Denidni, T.A. CA-CFAR detection performance of radar targets embedded in “non centered chi-2 gamma” clutter. Prog. Electromagn. Res. 2008, 88, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Shui, P. Floating Small Target Detection in Sea Clutter via Normalised Hurst Exponent. Electron. Lett. 2014, 50, 1240–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Xing, H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, H.; Liang, X.; Li, H. Sea-Surface Small Target Detection Based on Four Features Extracted by FAST Algorithm. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, H.; Tian, X.; Liang, J.; Shen, X. Sequence-Feature Detection of Small Targets in Sea Clutter Based on Bi-LSTM. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 4208811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Qi, H.; Tang, C.; Liu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Lian, J. Sea Clutter Suppression Method Based on Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Signal Processing, Communications and Computing (ICSPCC), Zhengzhou, China, 14–17 November 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Zhang, J.; Guo, L.; Wei, Y. A Gramian Angular Field and Dual-Stream Transformer-Based Inversion Model for Retrieving Evaporation Duct from Radar Sea Clutter. In Proceedings of the 2024 14th International Symposium on Antennas, Propagation and EM Theory (ISAPE), Hefei, China, 23–26 October 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Guo, Q.; Bi, H.; Li, Y. A Sea Clutter Suppression Method Based on Neighborhood Self-Supervised for Ship Detection in SAR Images. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 7th International Conference on Electronic Information and Communication Technology (ICEICT), Xi’an, China, 30 July–2 August 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 933–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wu, Y.; Sun, W.; Yu, H.; Luo, F. Target Detection in Sea Clutter Background via Deep Multi-Domain Feature Fusion. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Wang, G.; Ding, H.; Dong, Y.; Huang, Y.; Tian, K.; Zhang, M. Sea-detecting Radar Experiment and Target Feature Data Acquisition for Dual Polarization Multistate Scattering Dataset of Marine Targets. J. Radars 2023, 12, 456–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shui, P.-L.; Li, D.-C.; Xu, S.-W. Tri-Feature-Based Detection of Floating Small Targets in Sea Clutter. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2014, 50, 1416–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Luo, X.; Ding, H.; Wang, G.; Liu, N. A Detection Method of Small Target in Sea Clutter Environment Based on Feature Temporal Sequence. J. Electron. Inf. Technol. 2025, 47, 707–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).