Causal Matrix Long Short-Term Memory Network for Interpretable Significant Wave Height Forecasting

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

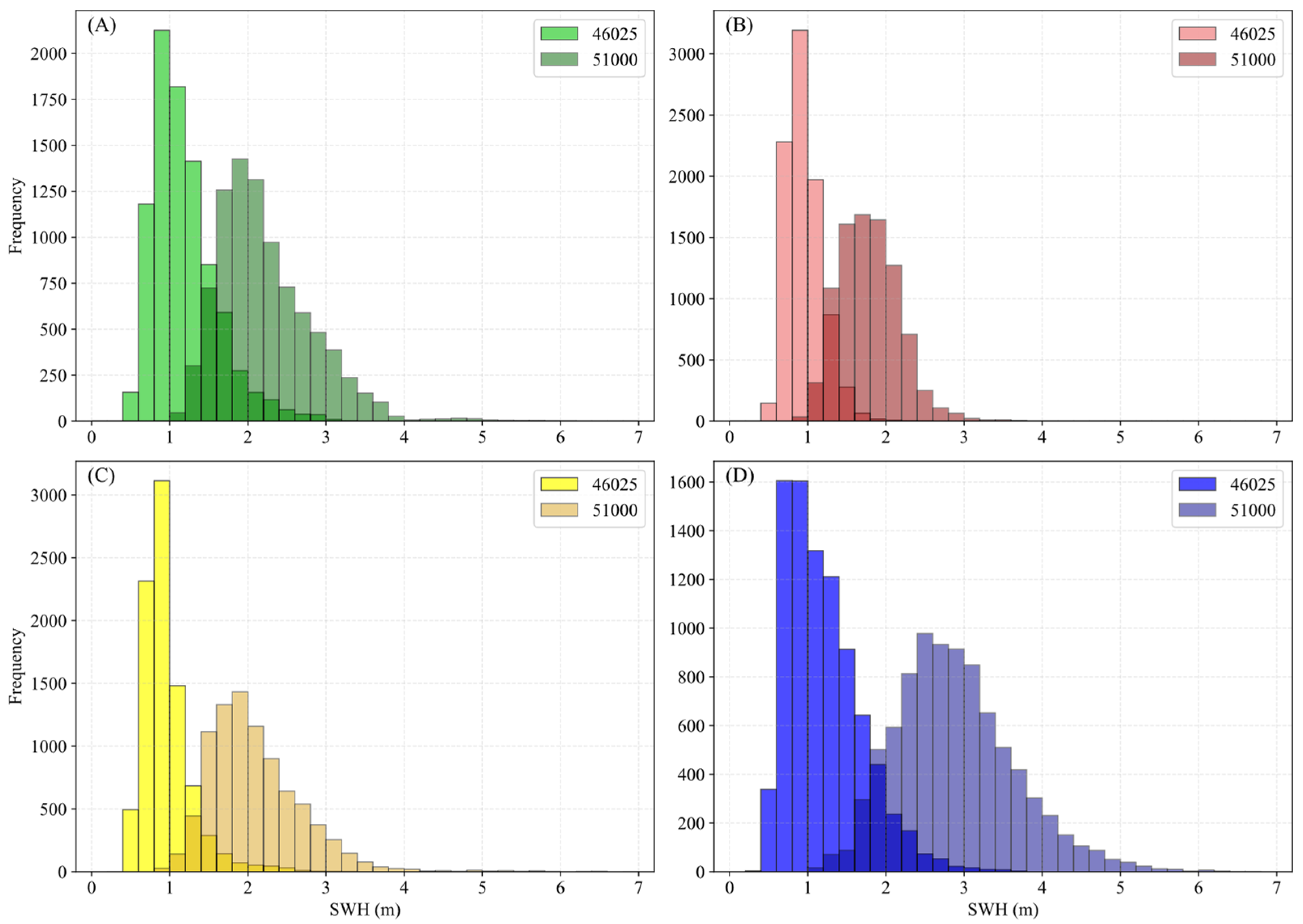

2.1. National Data Buoy Center Dataset

2.2. Cointegration Test

- (1)

- Perform Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) unit root tests [46] on all variable time series to determine their order of integration. Only pairs of time series sharing the same integration order qualify for subsequent cointegration testing. At both stations, sea surface temperature is identified as , while the other seven variables are .

- (2)

- For time-series pairs with identical integration orders, construct an ordinary least squares (OLS) regression. Taking the SWH series and the -th correlated variable series (same integration order) as an example:where and are OLS regression coefficients and denotes the residual series.

- (3)

- Conduct an ADF unit root test on the residual series . If is stationary, a cointegration relationship exists between and ; otherwise, no cointegration relationship is present.

- (4)

- Repeat Steps 2 and 3 to establish cointegration relationships across all qualifying time-series pairs.

2.3. Granger Causality Test

- (1)

- For variable pairs passing the cointegration test, we first posit the null hypothesis that no Granger causality exists between SWH series and the -th variable series .

- (2)

- Construct vector autoregression models for and using Equations (3) and (4), then compute regression coefficients and residuals:where denotes the lag order; and represent lagged values; and are intercept terms; , , , are coefficients; and , denote residuals.

- (3)

- An F-statistic test is performed on the residuals. If the F-statistic is significant (typically with p < 0.05), the null hypothesis is rejected, confirming Granger causality between and . Otherwise, the null hypothesis fails to be rejected.

- (4)

- Iterate through all cointegrated variable pairs to identify those with stable causal relationships.

2.4. Shapley Additive Explanations

2.5. Twin Delayed Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient Agent Architecture

- (1)

- Optimization objective

- (2)

- Temporal constraints

- (3)

- Markov decision process condition design

- (1)

- Agent state space

- (2)

- Agent action

- (3)

- Agent reward function

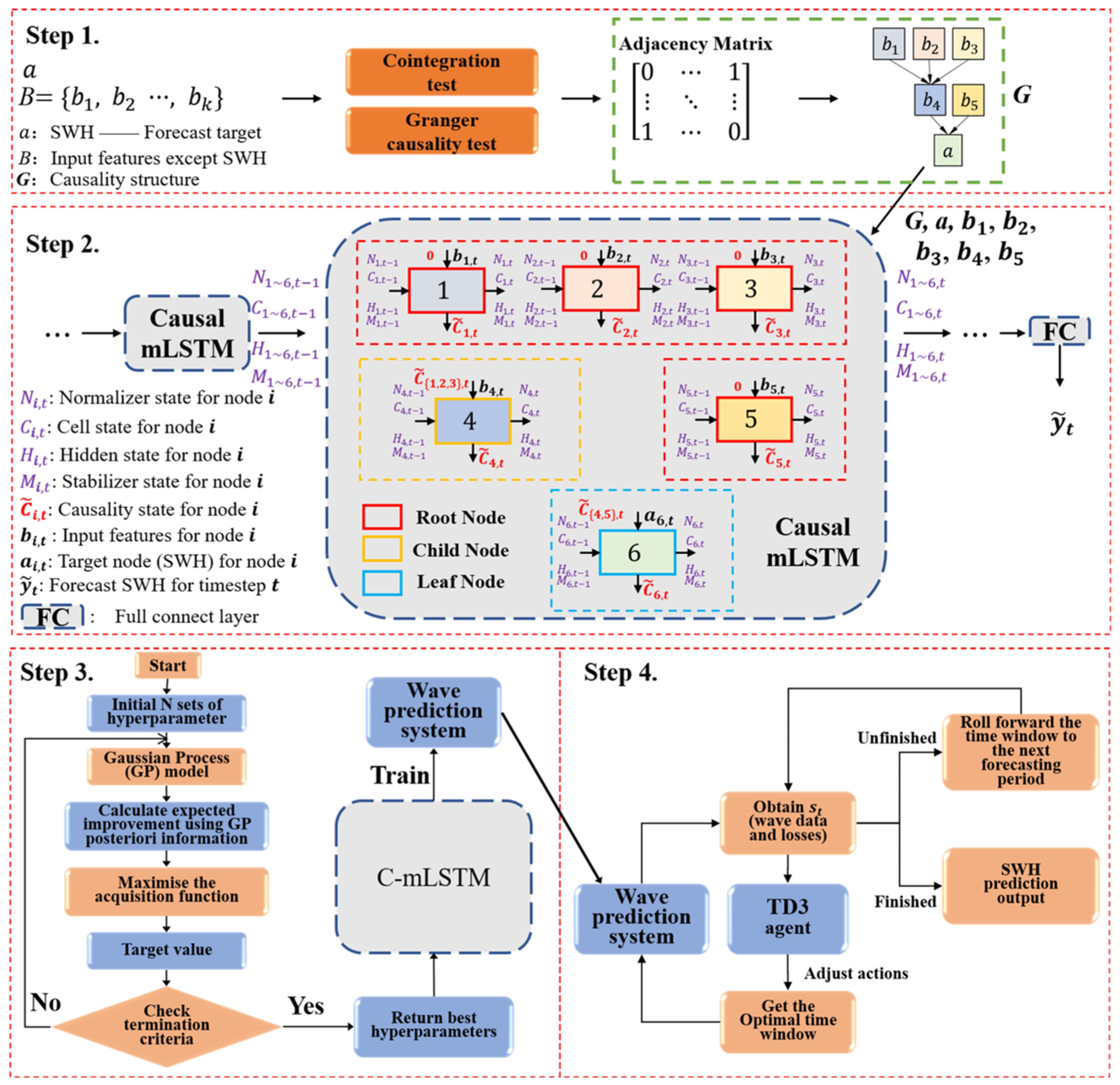

2.6. The Construction of the Model

2.6.1. Construction of the Causal Relationship Dataset

- (1)

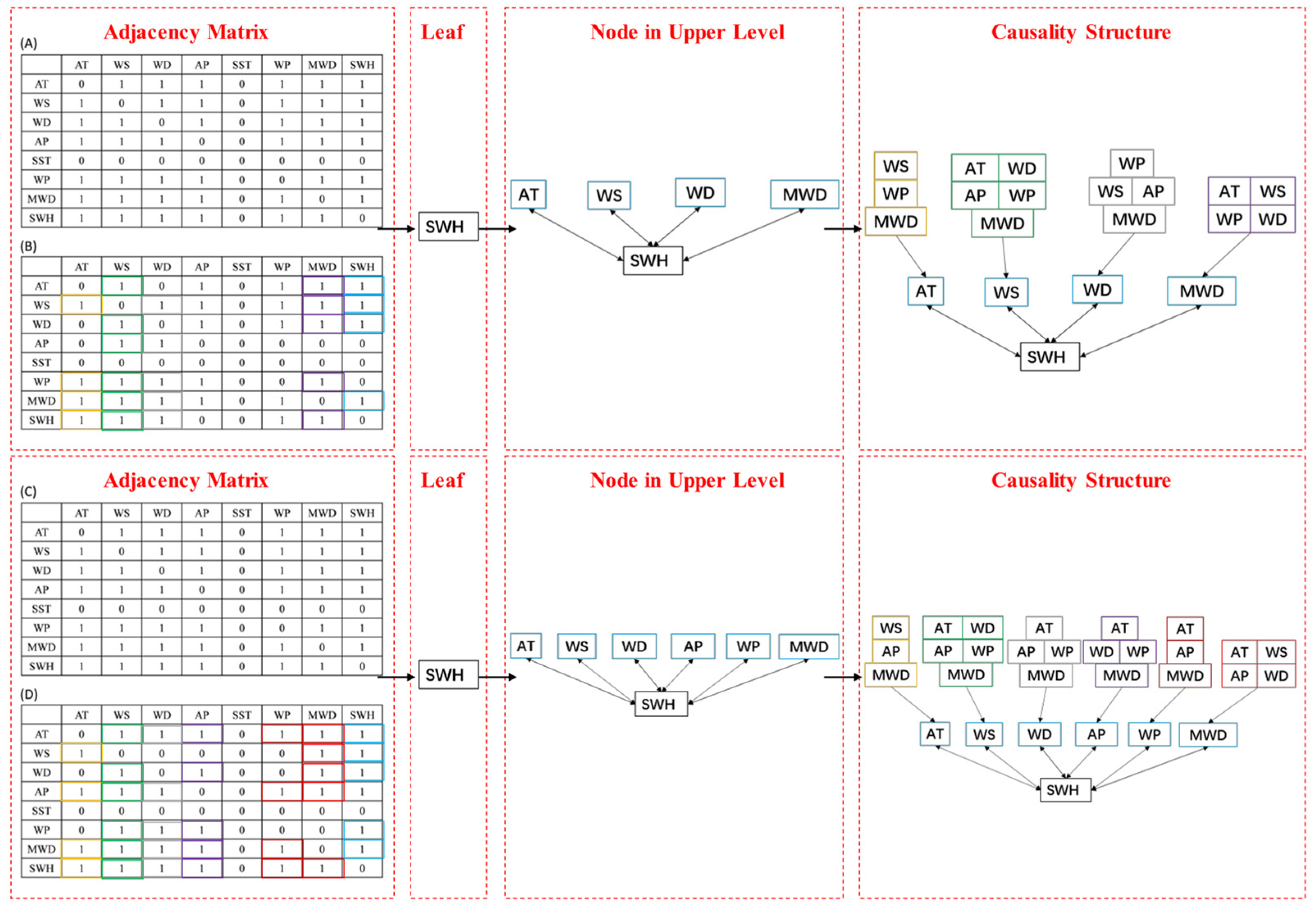

- Two-stage causal feature selection is performed on input features and target . In phase 1, cointegration tests identify variable pairs with long-term stable relationships (Section 2.2). In phase 2, Granger causality tests (Section 2.3) further explore causal relationships among variables exhibiting long-term stability. This two-stage selection reveals long-term stable causal relationships.

- (2)

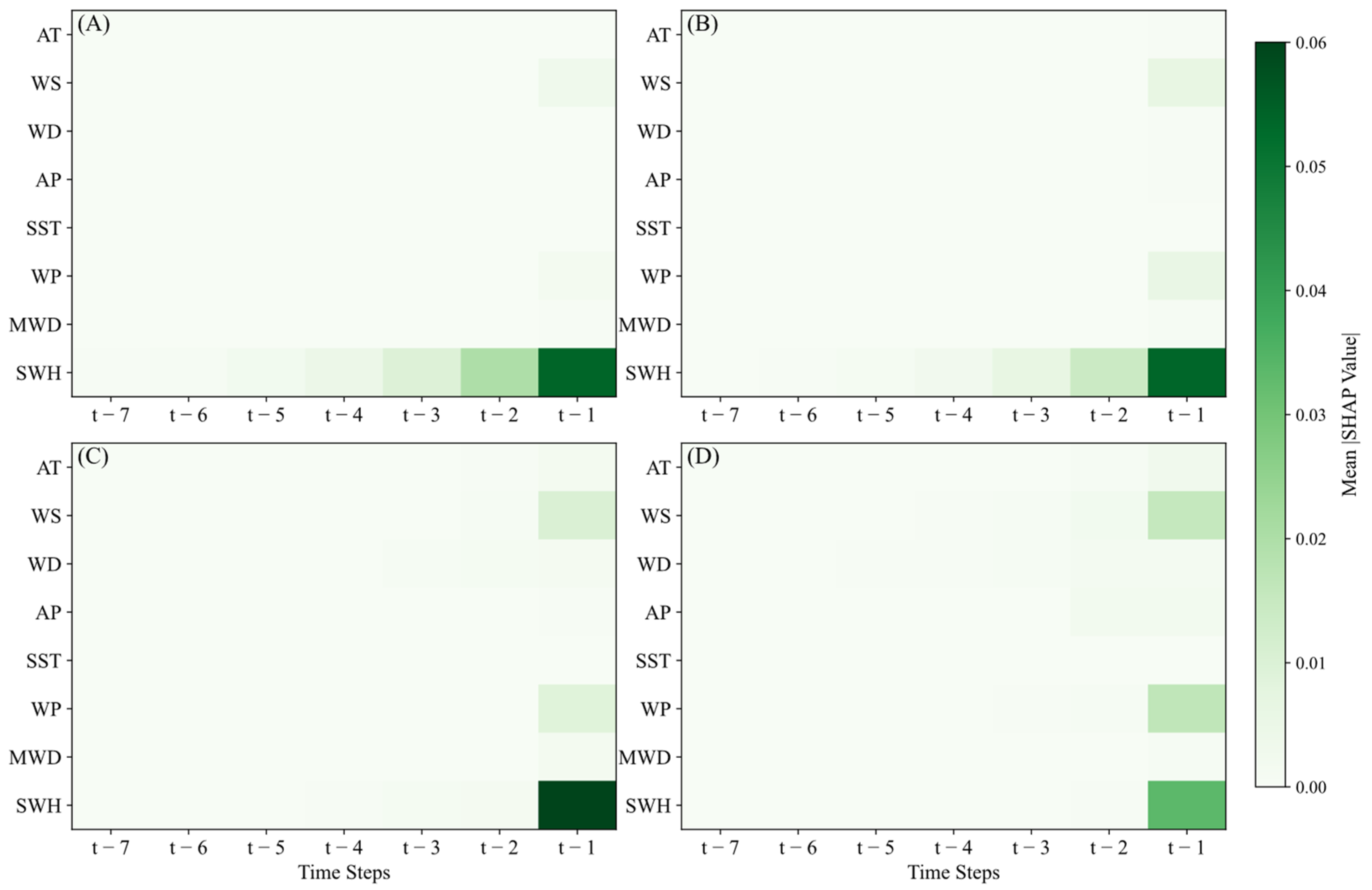

- Convert pairs of variables with long-term stable causal relationships into an adjacency matrix ). For any two variables (e.g., and ), indicates that is a long-term causal driver of (→). indicates no long-term causal relationship. Figure 4A,B show cointegration and Granger test results for Station 51000; Figure 4C,D show results for Station 46025. Notably, Station 46025 (nearshore) has two additional variables (AP and WP) causally related to SWH compared to Station 51000 (open sea), likely due to coastal terrestrial influences.

- (3)

- Transform the adjacency matrix into the long-term causal relationship dataset (Figure 4). The conversion involves four steps (using Station 51000 as an example): First, set prediction target SWH as the leaf node. Additionally, assign SWH’s causal drivers (AT, WS, WD, and MWD, indicated by the blue boxes) as parent nodes of the leaf. What is more, for variables in the blue boxes, repeat the previous step to identify their causal drivers and assign them as parent nodes. Finally, starting from the root node, compile each variable’s index, parent count, and parent indices into the dataset.

2.6.2. The Construction of Causality-Structured Matrix Long Short-Term Memory

2.6.3. Bayesian Optimization for Hyperparameter Tuning

2.6.4. Twin Delayed Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient for Dynamic Input Window Adjustment

2.7. Model Training and Evaluation

3. Results

3.1. Ablation Experiment

3.1.1. Analysis of BO Algorithm

3.1.2. Analysis of TD3 for Input Window Adjustment

3.2. Analysis of Seasonal Differences in Model Prediction Results

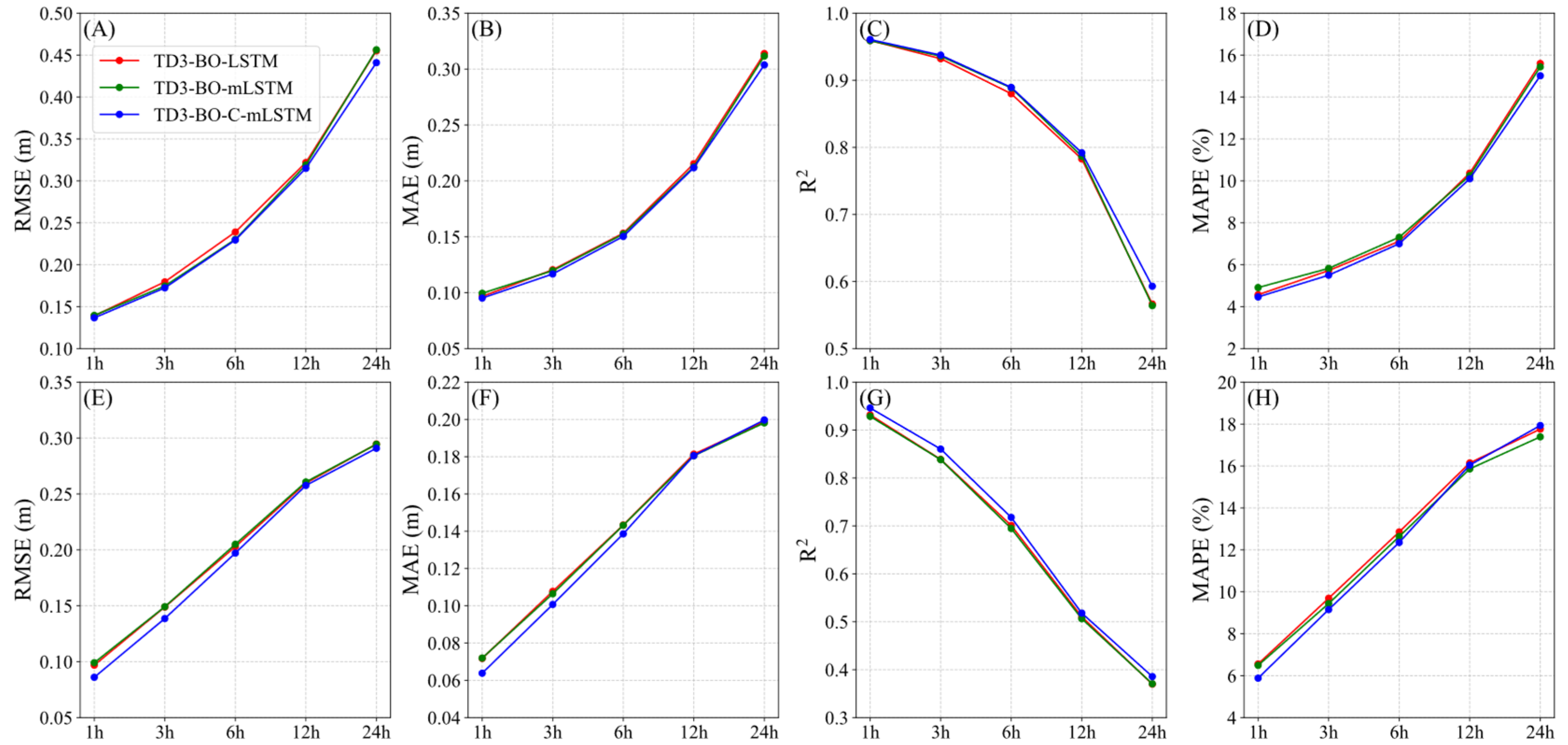

3.3. Analysis of Model Performance Across Lead Times

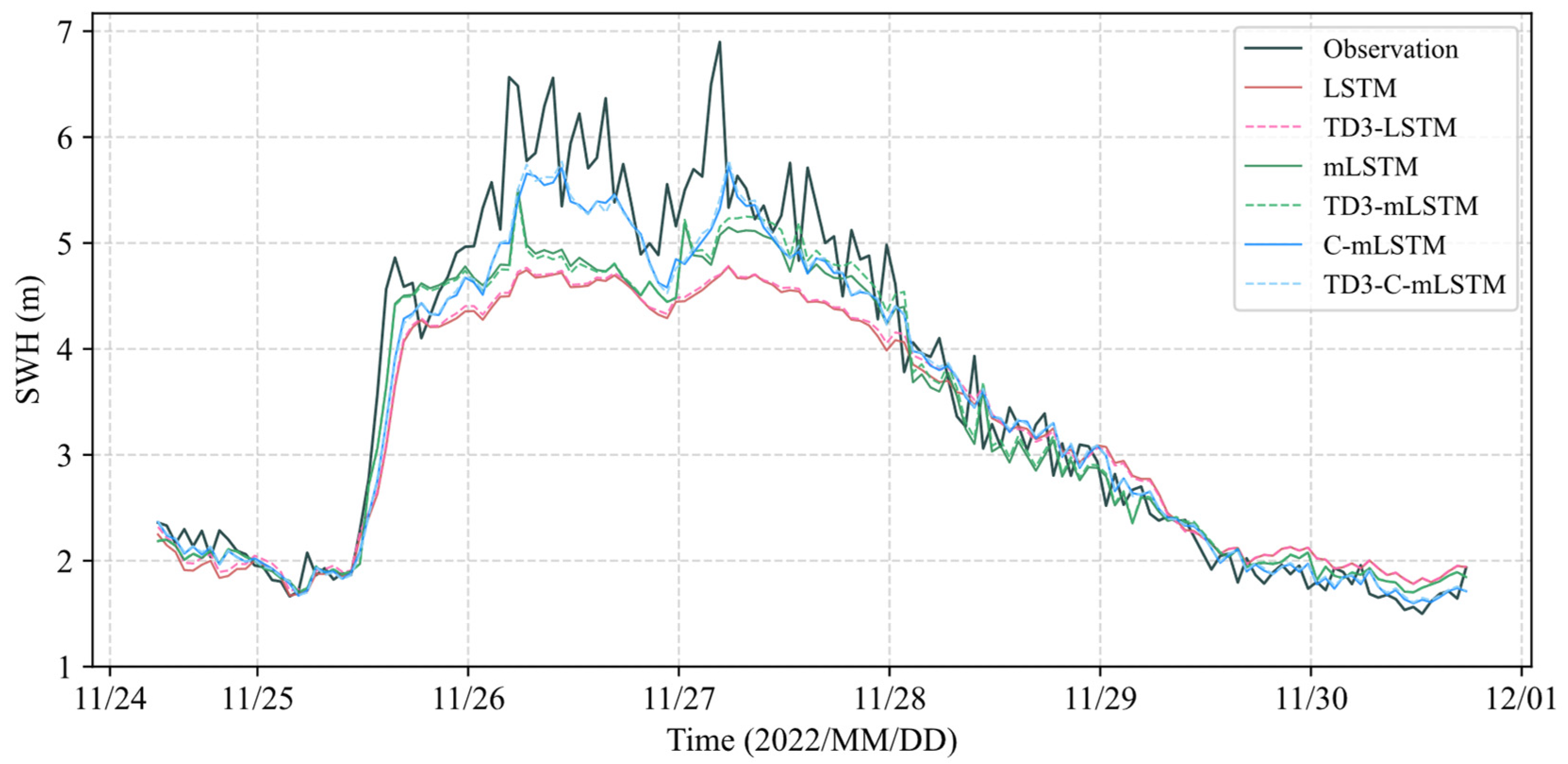

3.4. Model Predictive Capability for Rough Wave Conditions

4. Discussion

4.1. Sensitivity Analysis of Causal Structure Depth

4.2. Shapley Additive Explanations Analysis

4.3. Advantages and Limitations of C-mLSTM

- (1)

- Inheriting the strength of mLSTM in capturing temporal patterns, C-mLSTM delivers exceptional performance for SWH time-series forecasting.

- (2)

- Its two-stage causal feature screening (cointegration and Granger causality tests) enables learning stable long-term causal relationships among variables, enhancing both predictive accuracy and interpretability.

- (3)

- In terms of model structure, the C-mLSTM incorporates a dedicated causal inference unit that generates causal states for each variable, enabling the model to align predictions with the causal drivers of the current nodes, thereby adjusting the output of the predictions.

- (4)

- In terms of prediction results, the C-mLSTM model outperforms the LSTM and mLSTM models, which do not incorporate causal structures, under both normal and rough wave conditions.

- (5)

- (6)

- Despite its superior predictive capability, C-mLSTM requires longer training times (300 s per epoch) compared to LSTM/mLSTM (15 s per epoch), potentially limiting time-sensitive applications.

- (7)

- Despite the superior performance of C-mLSTM, its predictions for high SWH values remain biased, primarily due to the scarcity of high-value samples in the training data.

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The two-stage causal feature selection (cointegration and Granger causality tests) constructs causal relationship datasets. Embedding these identified causal dependencies into the mLSTM framework enhances predictive performance and interpretability, demonstrating particular efficacy for time-series forecasting with complex causal structures.

- (2)

- In terms of model optimization, we incorporated the BO algorithm and the TD3 algorithm. BO improves average SWH prediction accuracy by 16.48% through hyperparameter tuning for all models (LSTM, mLSTM, and C-mLSTM). TD3 dynamically adjusts input window length based on historical data and historical loss values, yielding a further 2.35% accuracy gain. Combined implementation delivers 16.85% overall performance improvement.

- (3)

- Compared to conventional LSTM and mLSTM, C-mLSTM achieves superior performance for 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h lead times under both normal and rough wave conditions (SWH > 2.5 m). Its leading accuracy across seasons, multiple lead times, and extreme events confirms its enhanced robustness and generalization capability.

- (4)

- Finally, through SHAP analysis, it was found that in 1 h SWH forecasts, the contributions of SWH, WS, and WP features are dominant. In 24 h forecasts, historical SWH remains the primary driver, while WS and WP gain significance; only SST and MWD exhibit negligible impacts.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dinwoodie, I.; Catterson, V.M.; McMillan, D. Wave Height Forecasting to Improve Off-Shore Access and Maintenance Scheduling. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Power & Energy Society General Meeting, Vancouver, BC, USA, 21–25 July 2013; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Vanem, E. Joint Statistical Models for Significant Wave Height and Wave Period in a Changing Climate. Mar. Struct. 2016, 49, 180–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.W.; Jeon, J. Probabilistic Forecasting of Wave Height for Offshore Wind Turbine Maintenance. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2018, 267, 877–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillou, N.; Lavidas, G.; Chapalain, G. Wave Energy Resource Assessment for Exploitation—A Review. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caires, S.; Sterl, A. 100-Year Return Value Estimates for Ocean Wind Speed and Significant Wave Height from the ERA-40 Data. J. Clim. 2005, 18, 1032–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Shiotani, S.; Sasa, K. Numerical Ship Navigation Based on Weather and Ocean Simulation. Ocean Eng. 2013, 69, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Sasa, K.; Prpić-Oršić, J.; Mizojiri, T. Statistical Analysis of Waves’ Effects on Ship Navigation Using High-Resolution Numerical Wave Simulation and Shipboard Measurements. Ocean Eng. 2021, 229, 108757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazeres-Ferradosa, T.; Taveira-Pinto, F.; Vanem, E.; Reis, M.T.; Neves, L.D. Asymmetric Copula–Based Distribution Models for Met-Ocean Data in Offshore Wind Engineering Applications. Wind Eng. 2018, 42, 304–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazeres-Ferradosa, T.; Welzel, M.; Schendel, A.; Baelus, L.; Santos, P.R.; Pinto, F.T. Extended Characterization of Damage in Rubble Mound Scour Protections. Coast. Eng. 2020, 158, 103671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardhuin, F.; Stopa, J.E.; Chapron, B.; Collard, F.; Husson, R.; Jensen, R.E.; Johannessen, J.; Mouche, A.; Passaro, M.; Quartly, G.D.; et al. Observing Sea States. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019, 6, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Tang, J.; Jia, H.; Dong, C.; Zhao, R. A Significant Wave Height Prediction Method Based on Improved Temporal Convolutional Network and Attention Mechanism. Electronics 2024, 13, 4879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lu, W.; Wang, D.; Lai, Z.; Ying, C.; Li, X.; Han, Y.; Wang, Z.; Dong, C. Spatiotemporal Wave Forecast with Transformer-Based Network: A Case Study for the Northwestern Pacific Ocean. Ocean Model. 2024, 188, 102323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Jiang, H. Physics-Guided Deep Learning for Skillful Wind-Wave Modeling. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadr3559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Group, T.W. The WAM Model—A Third Generation Ocean Wave Prediction Model. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 1988, 18, 1775–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Hua, F.; Pan, Z.; Sun, L. LAGFD-WAM Numerical Wave Model. I: Basic Physical Model. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 1991, 10, 483–488. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Y.; Hua, F.; Pan, Z.; Sun, L. LAGFD-WAM Numerical Wave Model. II: Characteristics Inlaid Scheme and Its Application. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 1992, 11, 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Booij, N.; Ris, R.C.; Holthuijsen, L.H. A Third-Generation Wave Model for Coastal Regions: 1. Model Description and Validation. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 1999, 104, 7649–7666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolman, H.L. User Manual and System Documentation of WAVEWATCH III ™ Version 3.14. Technical Note. 2019. Available online: https://polar.ncep.noaa.gov/mmab/papers/tn276/MMAB_276.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Hasselmann, S.; Hasselmann, K.; Allender, J.H.; Barnett, T.P. Computations and Parameterizations of the Nonlinear Energy Transfer in a Gravity-Wave Specturm. Part II: Parameterizations of the Nonlinear Energy Transfer for Application in Wave Models. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 1985, 15, 1378–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolman, H.L. Alleviating the Garden Sprinkler Effect in Wind Wave Models. Ocean Model. 2002, 4, 269–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Wang, J.; Cao, Y.; Bethel, B.J.; Xie, W.; Xu, G.; Sun, W.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Dong, C. Improving the Accuracy of Global ECMWF Wave Height Forecasts with Machine Learning. Ocean Model. 2024, 192, 102450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Xie, W.; Lu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Hui, N.; Dong, C. ConvLSTM-Based Wave Forecasts in the South and East China Seas. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 680079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Yan, Z.; Shi, B.; Sato, Y. A Slow Failure Particle Swarm Optimization Long Short-Term Memory for Significant Wave Height Prediction. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Su, T.; Li, X.; Wang, F.; Cui, J.; Liu, Z.; Wang, J. A Machine-Learning Approach Based on Attention Mechanism for Significant Wave Height Forecasting. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Z.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wu, X.; Zhang, D. Significant Wave Height Forecasting Based on EMD-TimesNet Networks. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Xiao, N.; Dong, S. A Novel Model to Predict Significant Wave Height Based on Long Short-Term Memory Network. Ocean Eng. 2020, 205, 107298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Deng, X.; Ge, P.; Dong, C.; Bethel, B.; Yang, L.; Xia, J. CNN-BiLSTM-Attention Model in Forecasting Wave Height over South-East China Seas. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2022, 73, 2151–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacarias, H.; Marques, J.A.L.; Felizardo, V.; Pourvahab, M.; Garcia, N.M. ECG Forecasting System Based on Long Short-Term Memory. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.-H.; Lin, Y.-L.; Pai, P.-F. Forecasting Flower Prices by Long Short-Term Memory Model with Optuna. Electronics 2024, 13, 3646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, N.; Xu, J.; Wurster, S.W.; Guo, H.; Woodring, J.; Van Roekel, L.P.; Shen, H.-W. GNN-Surrogate: A Hierarchical and Adaptive Graph Neural Network for Parameter Space Exploration of Unstructured-Mesh Ocean Simulations. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2022, 28, 2301–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Tang, T.; Gang, Y.; Jing, G. Hierarchical Neural Network-Based Hydrological Perception Model for Underwater Glider. Ocean Eng. 2022, 260, 112101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Li, W.; Hou, S.; Guan, J.; Zhou, S. HiGRN: A Hierarchical Graph Recurrent Network for Global Sea Surface Temperature Prediction. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2023, 14, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Feng, M.; Zhang, W.; Wang, H.; Wang, P. A Gaussian Process Regression-Based Sea Surface Temperature Interpolation Algorithm. J. Ocean. Limnol. 2021, 39, 1211–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rychlik, I.; Johannesson, P.; Leadbetter, M.R. Modelling and Statistical Analysis of Ocean-Wave Data Using Transformed Gaussian Processes. Mar. Struct. 1997, 10, 13–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinokić, L.; Dotlić, M.; Prodanović, V.; Kolaković, S.; Simonovic, S.P.; Stojković, M. Effectiveness of Three Machine Learning Models for Prediction of Daily Streamflow and Uncertainty Assessment. Water Res. X 2025, 27, 100297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Xu, G.; Zhang, H.; Dong, C. Developing a Deep Learning-Based Storm Surge Forecasting Model. Ocean Model. 2023, 182, 102179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musinguzi, A.; Akbar, M.K.; Fleming, J.G.; Hargrove, S.K. Understanding Hurricane Storm Surge Generation and Propagation Using a Forecasting Model, Forecast Advisories and Best Track in a Wind Model, and Observed Data—Case Study Hurricane Rita. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2019, 7, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Qin, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yao, L.; Li, Q.; Li, J.; Pei, S. Long Short-Term Memory Network Based on Neighborhood Gates for Processing Complex Causality in Wind Speed Prediction. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 192, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Xu, G.; Han, G.; Bethel, B.J.; Xie, W.; Zhou, S. Recent Developments in Artificial Intelligence in Oceanography. Ocean-Land-Atmos. Res. 2022, 2022, 9870950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Dai, Y.; Shangguan, W.; Wei, Z.; Wei, N.; Li, Q. Causality-Structured Deep Learning for Soil Moisture Predictions. J. Hydrometeorol. 2022, 23, 1315–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mockus, J.; Tiesis, V.; Zilinskas, A. The Application of Bayesian Methods for Seeking the Extremum. Towards Glob. Optim. 1978, 2, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snoek, J.; Larochelle, H.; Adams, R.P. Practical Bayesian Optimization of Machine Learning Algorithms. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2012; Volume 25. [Google Scholar]

- Shahriari, B.; Swersky, K.; Wang, Z.; Adams, R.P.; de Freitas, N. Taking the Human Out of the Loop: A Review of Bayesian Optimization. Proc. IEEE 2016, 104, 148–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Zhao, R.; Wu, F.; Yan, J.; Dong, C. A Two Channel Optimized SWH Deep Learning Forecast Model Coupled with Dimensionality Reduction Scheme and Attention Mechanism. Ocean Eng. 2025, 330, 121217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimoto, S.; Hoof, H.; Meger, D. Addressing Function Approximation Error in Actor-Critic Methods. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning; PMLR, Stockholm, Sweden, 10–15 July 2018; Volume 80, pp. 1587–1596. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, J.T. What Goes Around Comes Around: Unit Root Tests and Cointegration. Political Anal. 1992, 4, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granger, C.W.J. Investigating Causal Relations by Econometric Models and Cross-Spectral Methods. Econometrica 1969, 37, 424–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.-I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Curran Associates Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 10, pp. 4768–4777. [Google Scholar]

- Shapley, L.S. A Value for N-Person Games; RAND Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, T.; Xu, L.; Lv, Y.; Cai, R.; Pan, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Chen, N. Integrating Causal Inference with ConvLSTM Networks for Spatiotemporal Forecasting of Root Zone Soil Moisture. J. Hydrol. 2025, 659, 133246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, M.; Pöppel, K.; Spanring, M.; Auer, A.; Prudnikova, O.; Kopp, M.; Klambauer, G.; Brandstetter, J.; Hochreiter, S. xLSTM: Extended Long Short-Term Memory. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 107547–107603. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.A. A Simple Neural Network Generating an Interactive Memory. Math. Biosci. 1972, 14, 197–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.A.; Silverstein, J.W.; Ritz, S.A.; Jones, R.S. Distinctive Features, Categorical Perception, and Probability Learning: Some Applications of a Neural Model. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 413–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohonen, T. Correlation Matrix Memories. IEEE Trans. Comput. 1972, C–21, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long Short-Term Memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkin, B.; Beck, M.; Pöppel, K.; Hochreiter, S.; Brandstetter, J. Vision-LSTM: xLSTM as Generic Vision Backbone. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Conference on Learning Representations, Singapore, 24–28 April 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Bergstra, J.; Bardenet, R.; Bengio, Y.; Kégl, B. Algorithms for Hyper-Parameter Optimization. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Granada, Spain, 12–15 December 2011; pp. 2546–2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Chen, Z.; Wang, H.; Yeung, D.-Y.; Wong, W.; Woo, W. Convolutional LSTM Network: A Machine Learning Approach for Precipitation Nowcasting. In Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 7–12 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Baek, K.G.; Brock, W.A. A Nonparametric Test for Independence of A Multivariate Time Series. Stat. Sin. 1992, 2, 137–156. [Google Scholar]

| Full Name | Abbreviation | Units |

|---|---|---|

| Air temperature | AT | K |

| Wind speed | WS | m/s |

| Wind direction | WD | Degree |

| Air pressure at sea level | AP | Pa |

| Sea surface temperature | SST | K |

| Average period | WP | s |

| Mean wave direction | MWD | Degree |

| Significant wave height | SWH | m |

| Station | Average Value | Standard Deviation | Variance | Missing No. | Total No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 46025 | 1.075 | 0.391 | 0.153 | 783 | 35,064 |

| 51000 | 2.244 | 0.729 | 0.531 | 554 | 35,064 |

| Station | Maximum Value | Minimum Value | First Quartile | Median | Third Quartile |

| 46025 | 3.758 | 0.366 | 0.805 | 0.978 | 1.245 |

| 51000 | 7.291 | 0.864 | 1.725 | 2.083 | 2.634 |

| Default Value | LSTM | mLSTM | C-mLSTM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Batch size | {8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, 512} | 32 | 8 | 16 |

| Hidden layer size | {8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, 512} | 64 | 128 | 128 |

| Learning rate | [10−5, 10−1] | 0.0057578 | 0.0046483 | 0.0039066 |

| Component | Specification |

|---|---|

| Operating System | Microsoft Windows 10 |

| CPU | Intel Core i5 13600K (14 cores, 20 threads) |

| GPU | NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4070 (12 GB) |

| Memory | 64 G DDR5 (4800 MHz) |

| Software Stack | Python 3.9.18, torch 2.3.0+cu121, tensorflow-gpu 2.7.0 |

| RMSE (m) | MAE (m) | R2 | MAPE (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSTM | 0.3483 | 0.2361 | 0.7460 | 11.6126 |

| mLSTM | 0.3439 | 0.2303 | 0.7520 | 11.3353 |

| C-mLSTM | 0.3304 | 0.2244 | 0.7711 | 11.0577 |

| TD3-LSTM | 0.3475 | 0.2335 | 0.7471 | 11.4408 |

| TD3- mLSTM | 0.3435 | 0.2298 | 0.7527 | 11.3077 |

| TD3-C-mLSTM | 0.3283 | 0.2215 | 0.7741 | 10.8443 |

| BO-LSTM | 0.3232 | 0.2146 | 0.7811 | 10.2978 |

| BO-mLSTM | 0.3228 | 0.2172 | 0.7816 | 10.5462 |

| BO-C-mLSTM | 0.3163 | 0.2131 | 0.7902 | 10.1948 |

| TD3-BO-LSTM | 0.3219 | 0.2153 | 0.7828 | 10.3713 |

| TD3-BO-mLSTM | 0.3189 | 0.2125 | 0.7868 | 10.2509 |

| TD3-BO-C-mLSTM | 0.3150 | 0.2118 | 0.7920 | 10.1023 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xie, M.; Sun, W.; Han, Y.; Ren, S.; Li, C.; Ji, J.; Yu, Y.; Zhou, S.; Dong, C. Causal Matrix Long Short-Term Memory Network for Interpretable Significant Wave Height Forecasting. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1872. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13101872

Xie M, Sun W, Han Y, Ren S, Li C, Ji J, Yu Y, Zhou S, Dong C. Causal Matrix Long Short-Term Memory Network for Interpretable Significant Wave Height Forecasting. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(10):1872. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13101872

Chicago/Turabian StyleXie, Mingshen, Wenjin Sun, Ying Han, Shuo Ren, Chunhui Li, Jinlin Ji, Yang Yu, Shuyi Zhou, and Changming Dong. 2025. "Causal Matrix Long Short-Term Memory Network for Interpretable Significant Wave Height Forecasting" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 10: 1872. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13101872

APA StyleXie, M., Sun, W., Han, Y., Ren, S., Li, C., Ji, J., Yu, Y., Zhou, S., & Dong, C. (2025). Causal Matrix Long Short-Term Memory Network for Interpretable Significant Wave Height Forecasting. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(10), 1872. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13101872