Navigational Risk Evaluation of One-Way Channels: Modeling and Application to the Suez Canal

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- For the first time, the whole channel is divided into multiple channel segments from the perspective of similar channel characteristics, and a risk evaluation method applicable to one-way channels is proposed.

- (2)

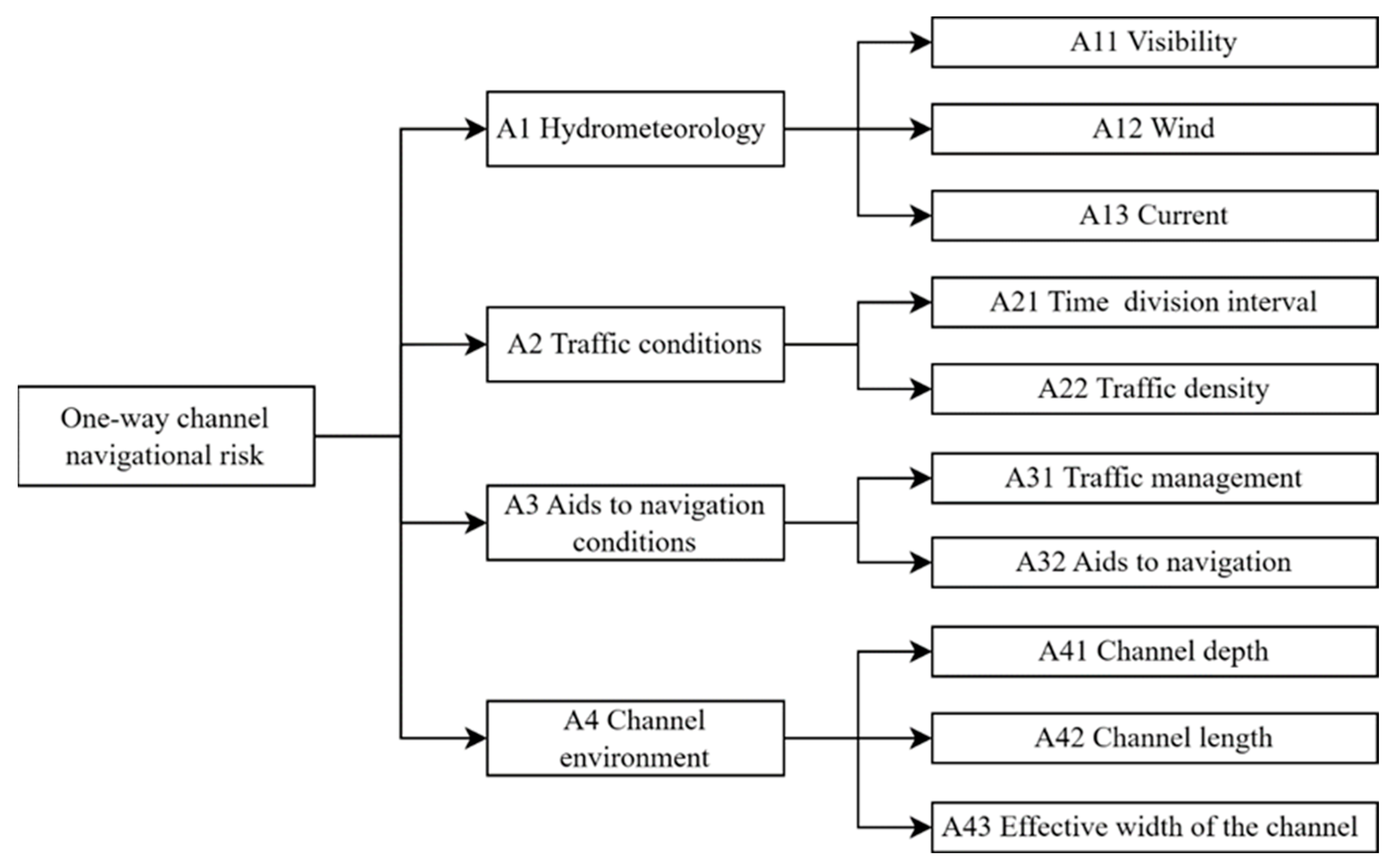

- Two innovative indexes, “effective width of channel” and “time division interval”, are added to the one-way channel navigation risk index system to make it more applicable to one-way channel risk evaluation.

- (3)

- The introduction of the compromise coefficient effectively combines subjective evaluation and objective data, and the evidential reasoning (ER) method is used for the channel risk aggregation, which can better deal with the uncertainty of the complex system.

- (4)

- The ship grounding accidents in the Suez Canal during the period of 2021–2023 are used as a case study to demonstrate the application value of the proposed evaluation model. The results of this study reveal a new perspective of waterway management for one-way channel risk evaluation.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Research on Navigational Risks of Two-Way Channels

2.2. Research on Navigational Risks of Compound Channels

2.3. Research on Navigational Risks of Narrow Channels

2.4. Research on Navigational Risks of One-Way Channels

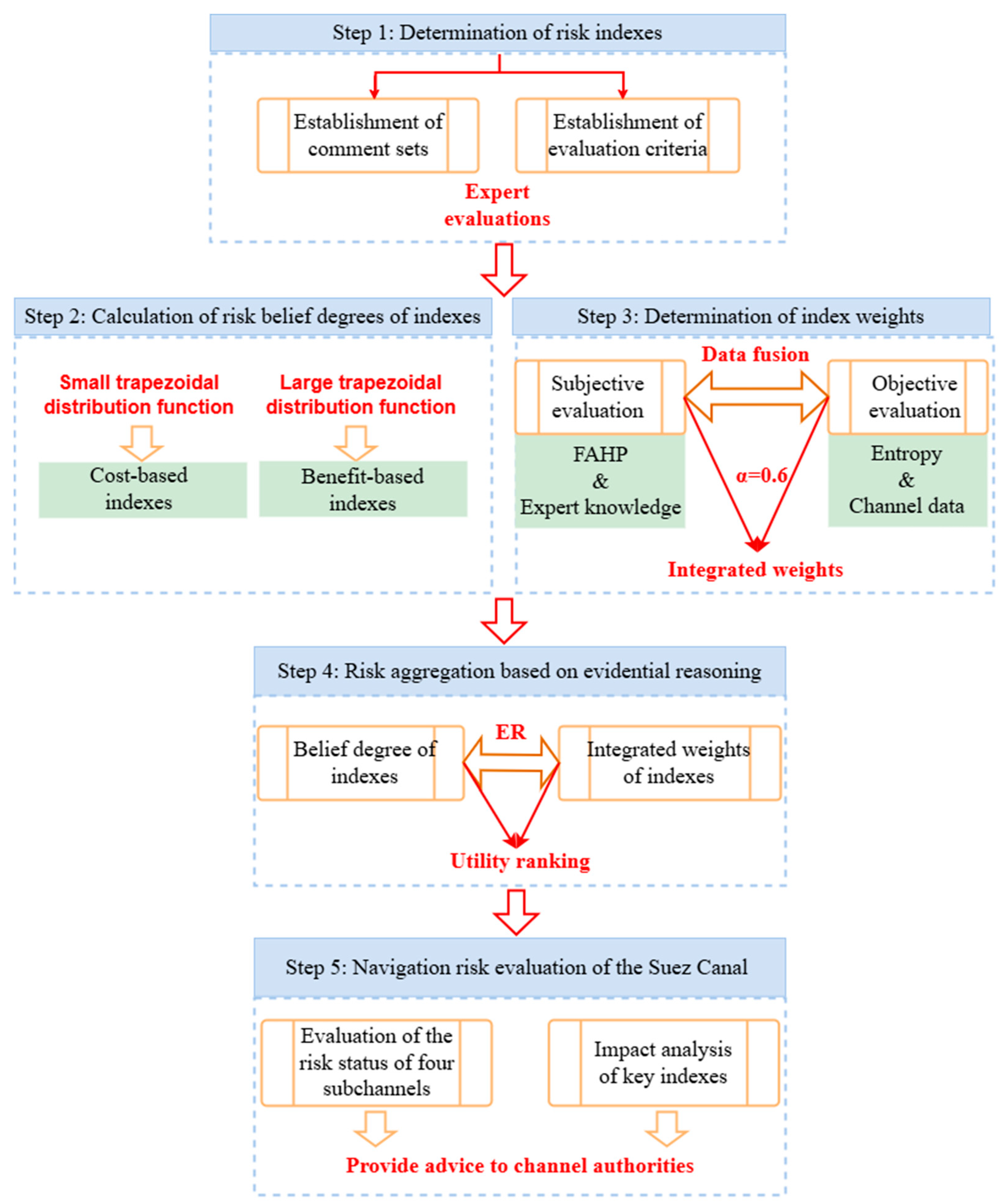

3. Methodology

3.1. Determination of Indexes

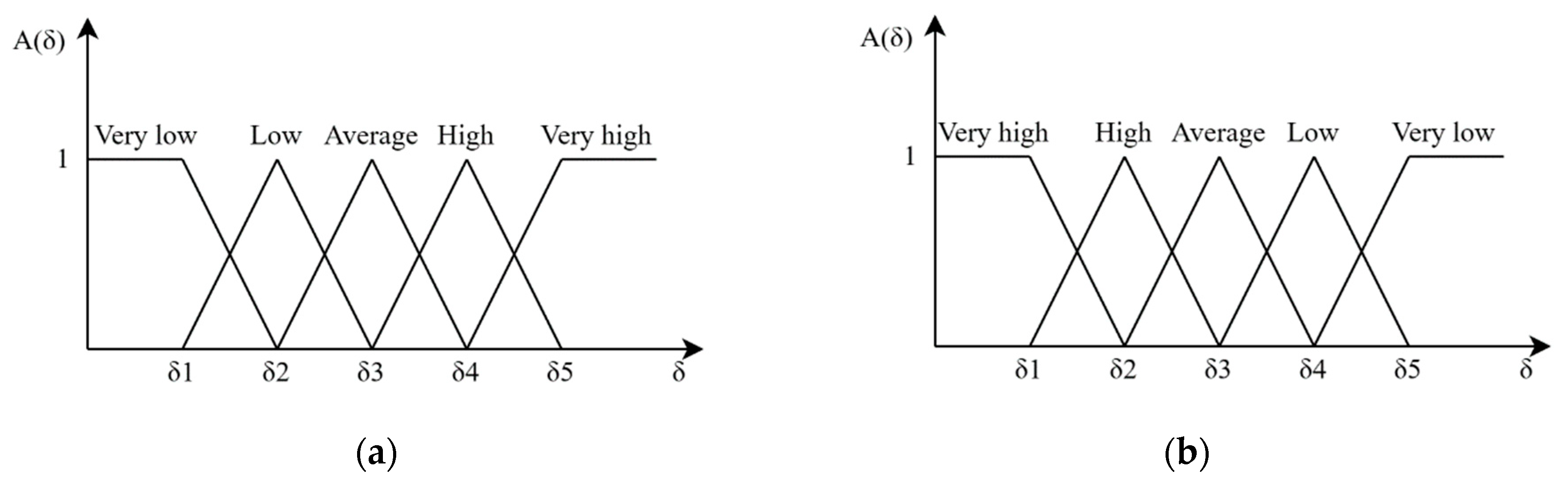

3.2. Quantification and Rating of Indexes

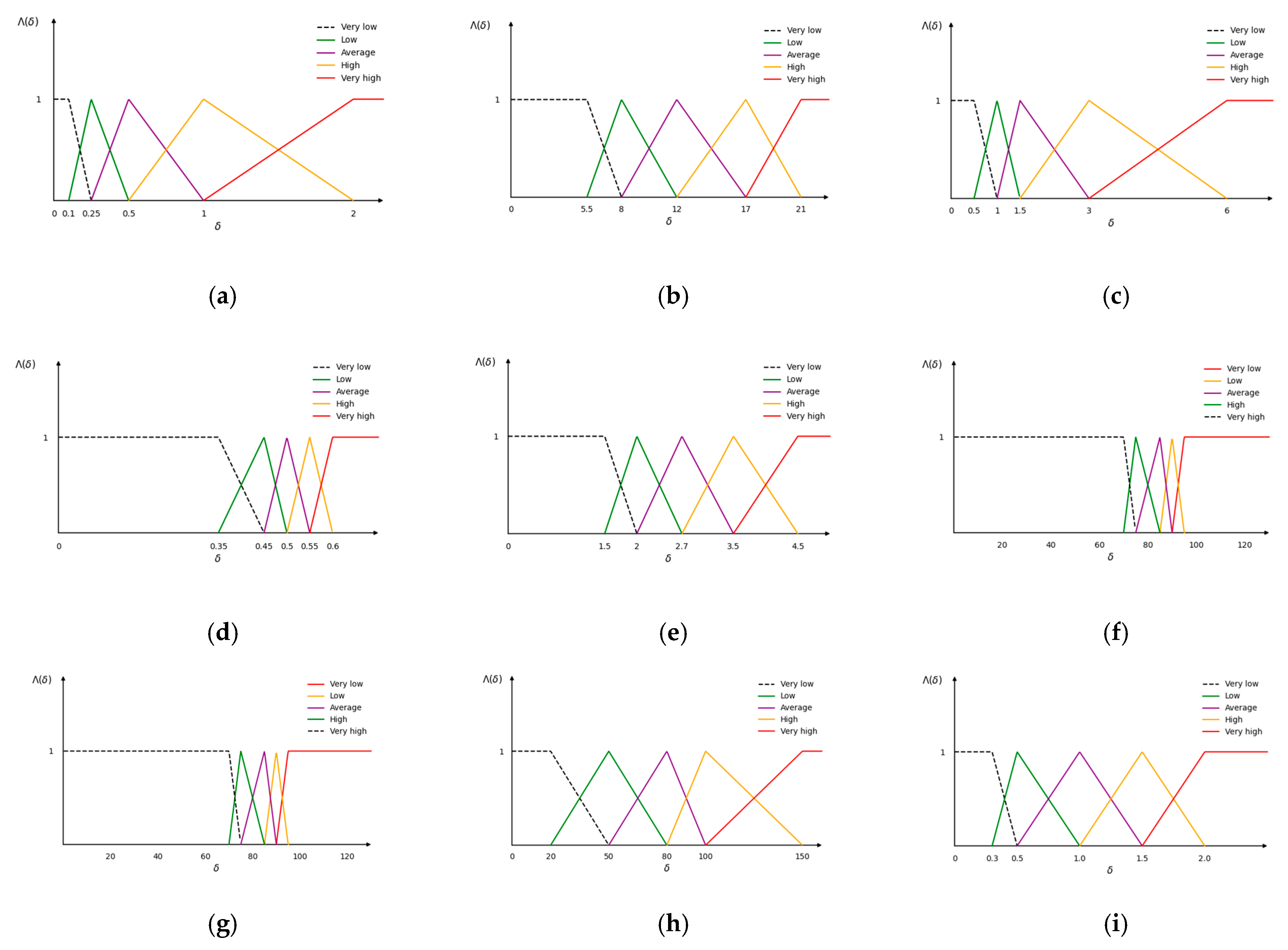

- (1)

- Evaluation criteria for hydrometeorology

- (2)

- Evaluation criterion for traffic conditions

- (3)

- Evaluation criterion for aids to navigation conditions

- (4)

- Evaluation criterion for channel environment

3.3. Determination of Comprehensive Weights of Indexes

3.4. Risk Aggregation Based on Evidential Reasoning (ER)

3.5. Utility Ranking

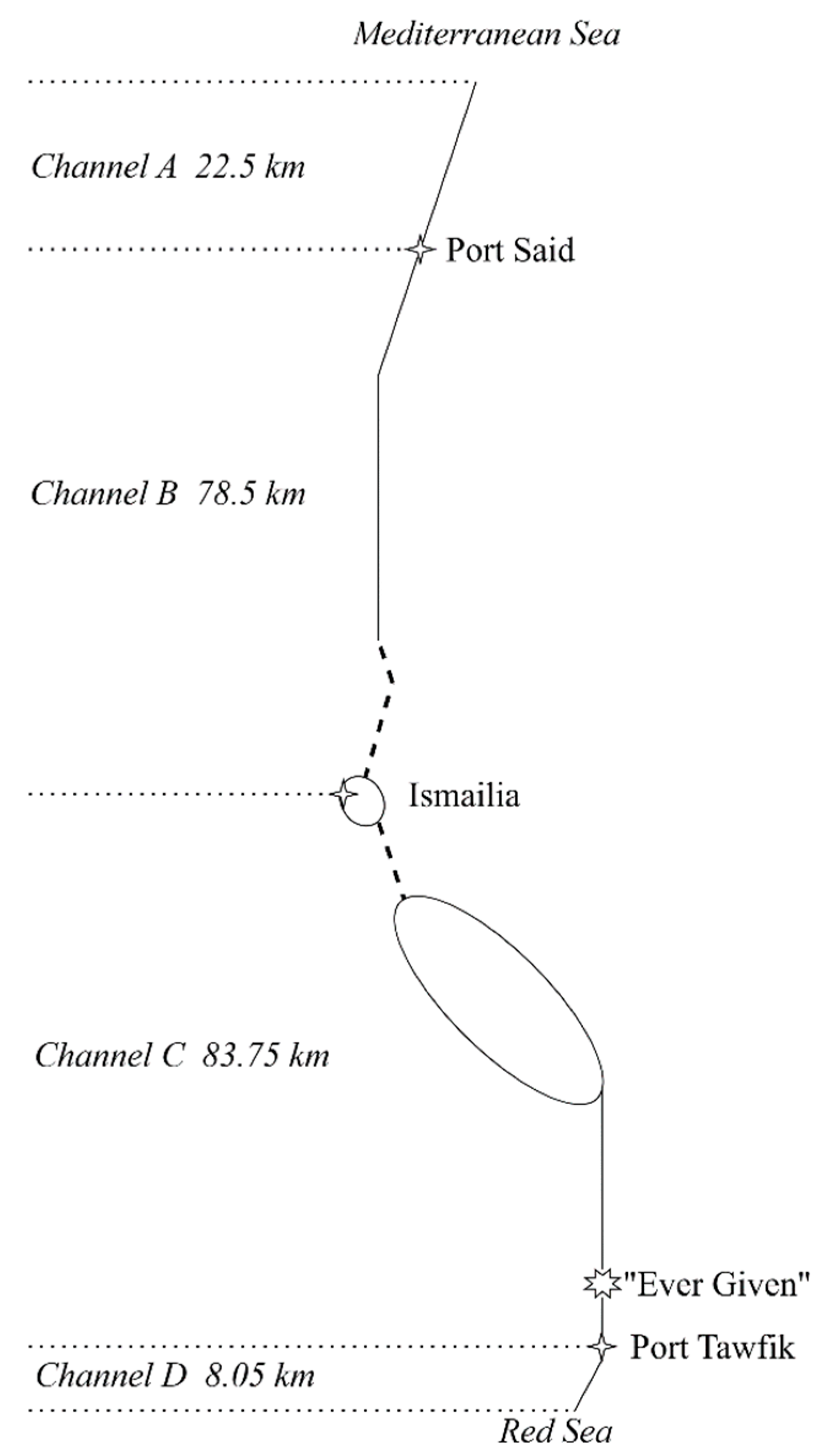

4. Case Study

4.1. Determination and Quantification of Indexes

4.1.1. Determination of Hydrometeorological Conditions

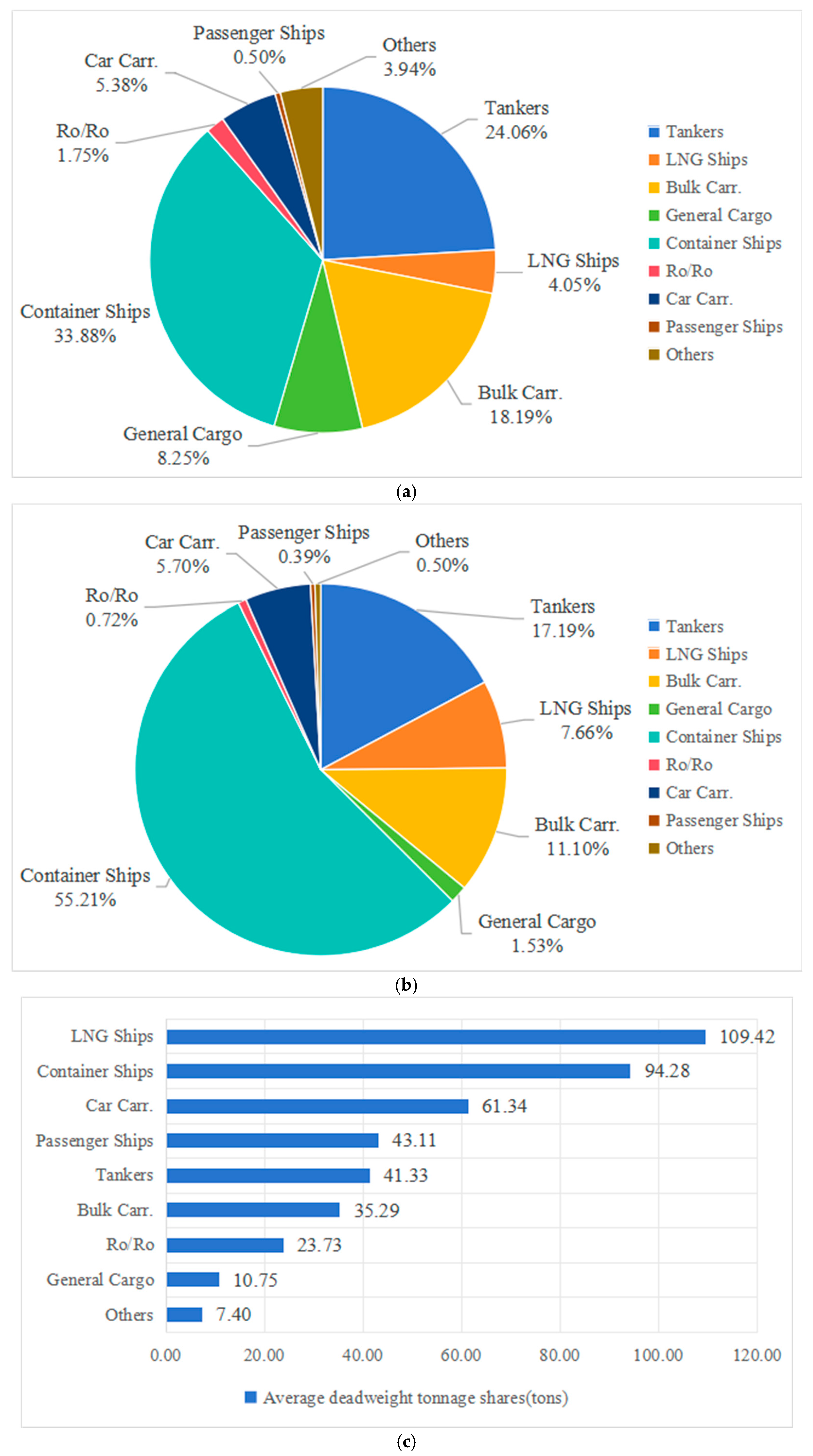

4.1.2. Determination of Traffic Conditions

4.1.3. Determination of Aids to Navigation Conditions

4.1.4. Determination of Channel Environment

4.2. Determination of Evaluation Values for Indexes

4.3. Calculation of Belief Degrees of Indexes

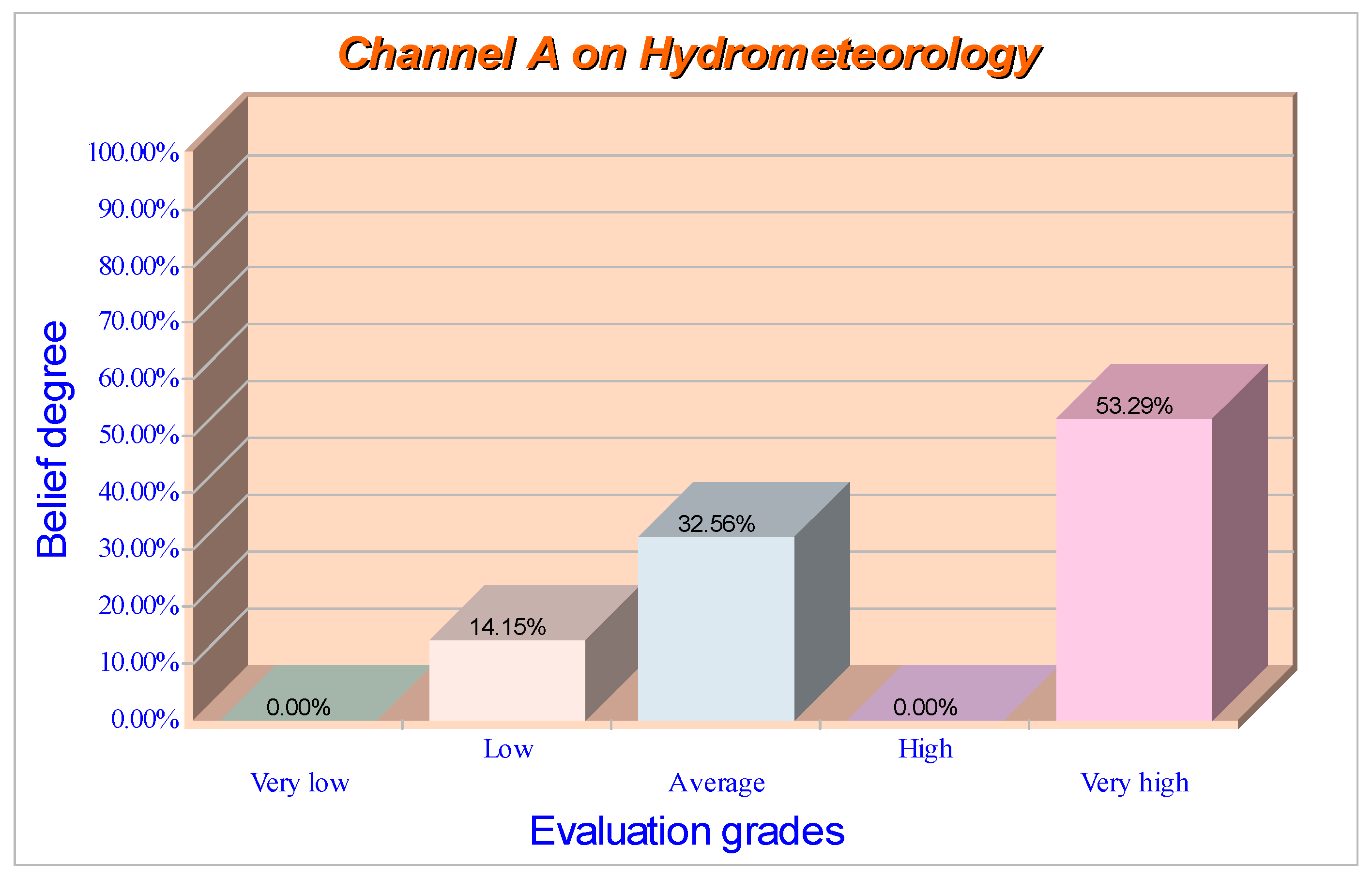

- (1)

- Based on the collected meteorological conditions of the Suez Canal from 2016 to 2021, it is concluded that the difference between the values of the annual average minimum visibility and the annual average maximum wind speed of the four sections of the channel are small and equal.

- (2)

- All four sections of the channel are under the jurisdiction of the SCA, and aids to navigation are uniformly installed by the management according to IMO rules.

- (3)

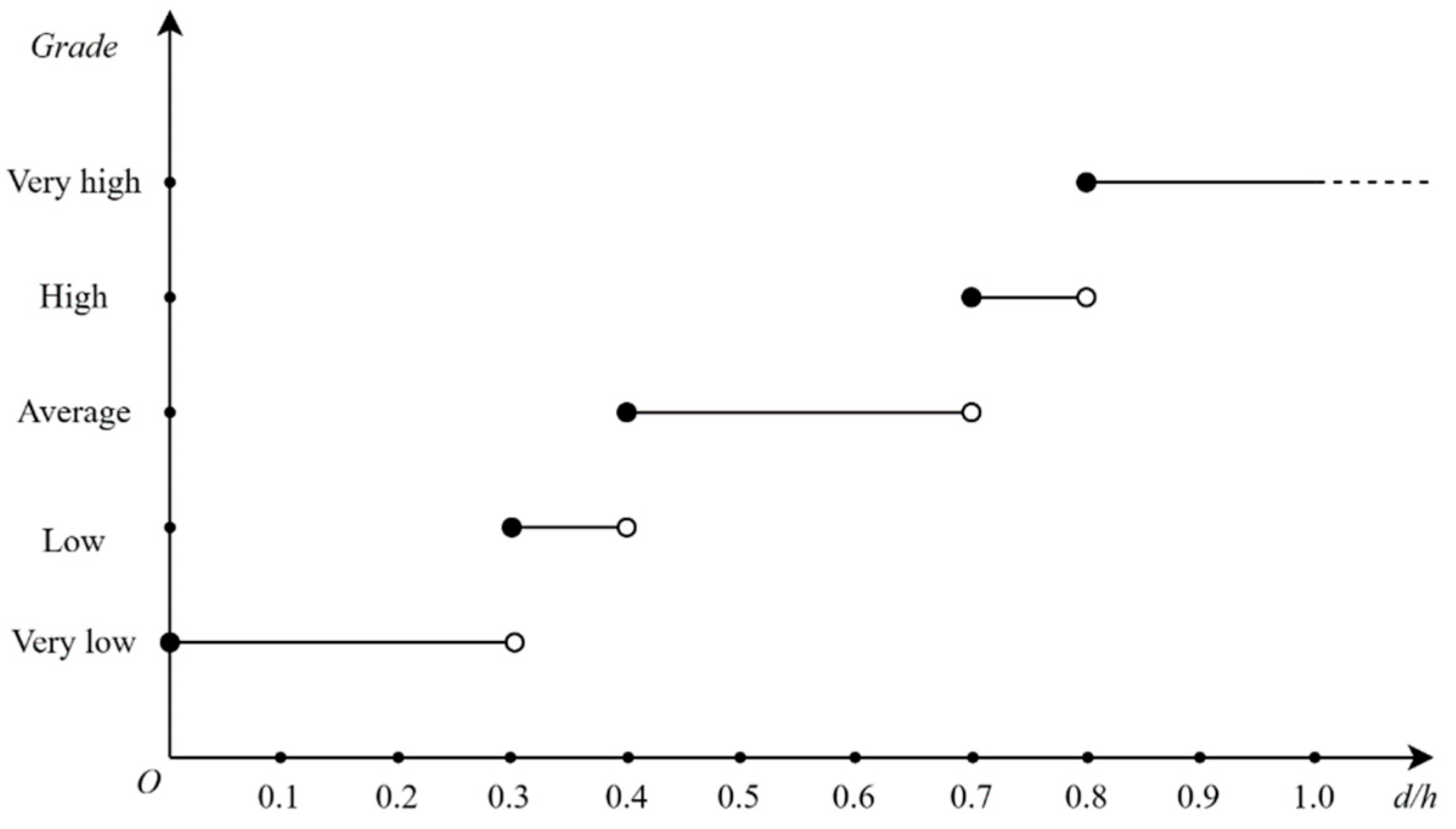

- The difference between the two values of the channel depth of the four sections of the channel is small. The value of the selected standard ship draught is certain, and the ratio of the ship draught to the channel depth is calculated to be in the medium risk of the index evaluation within the threshold value of the standard.

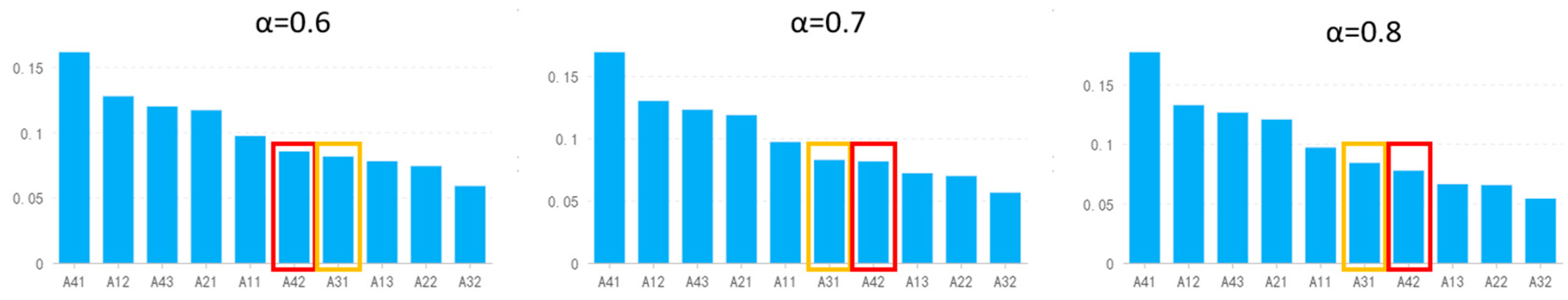

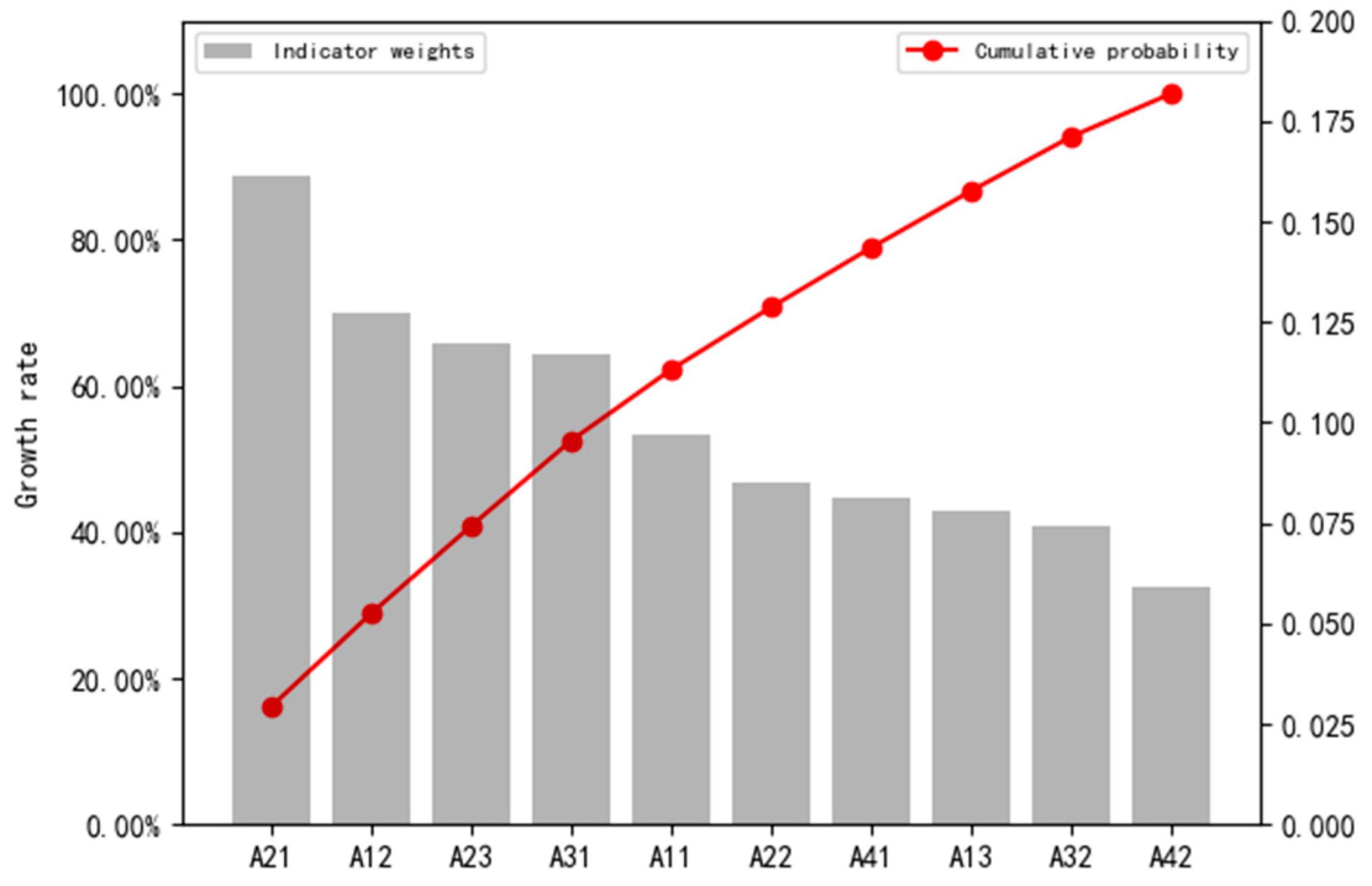

4.4. Calculation of Comprehensive Weights of Indexes

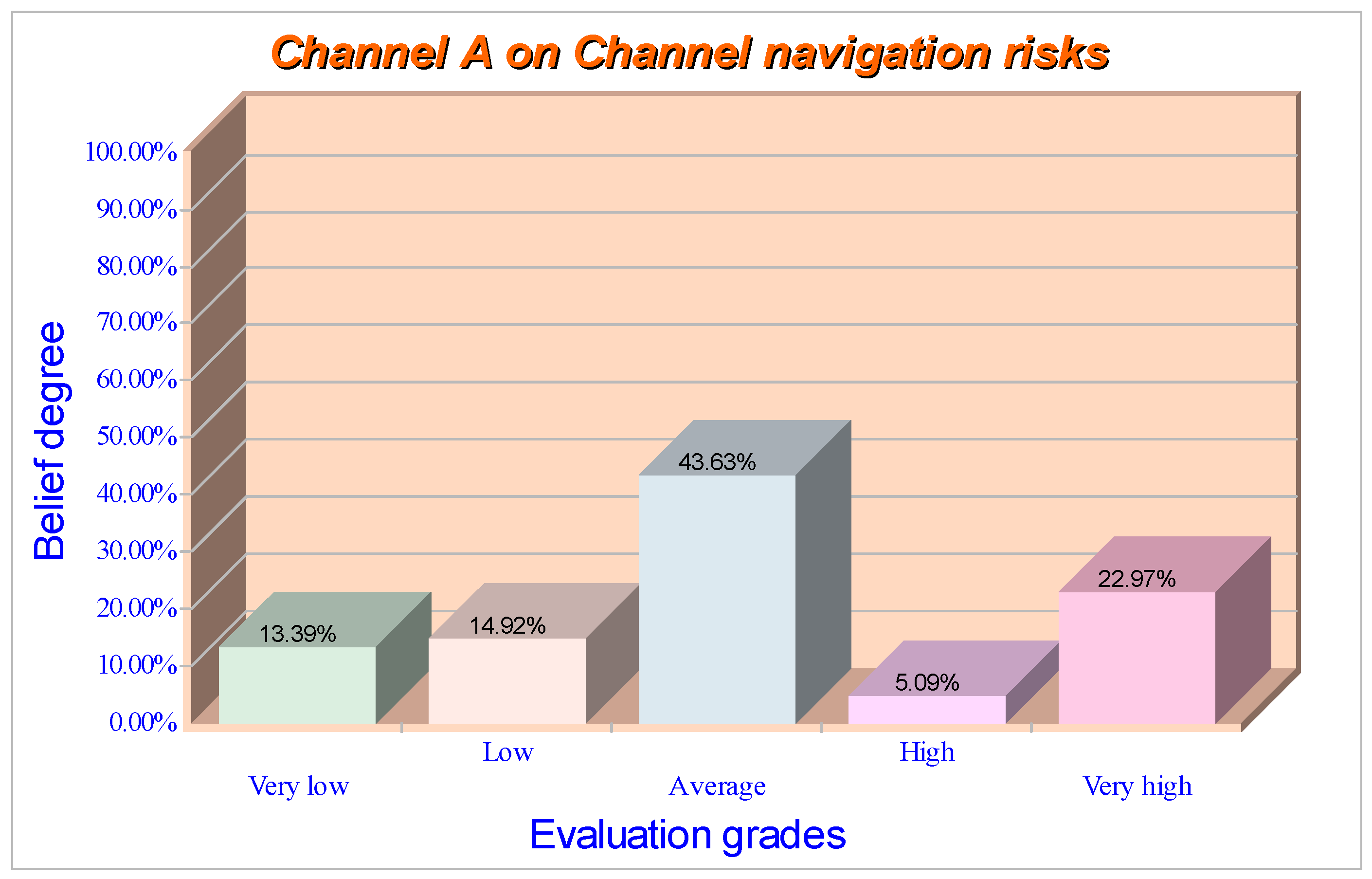

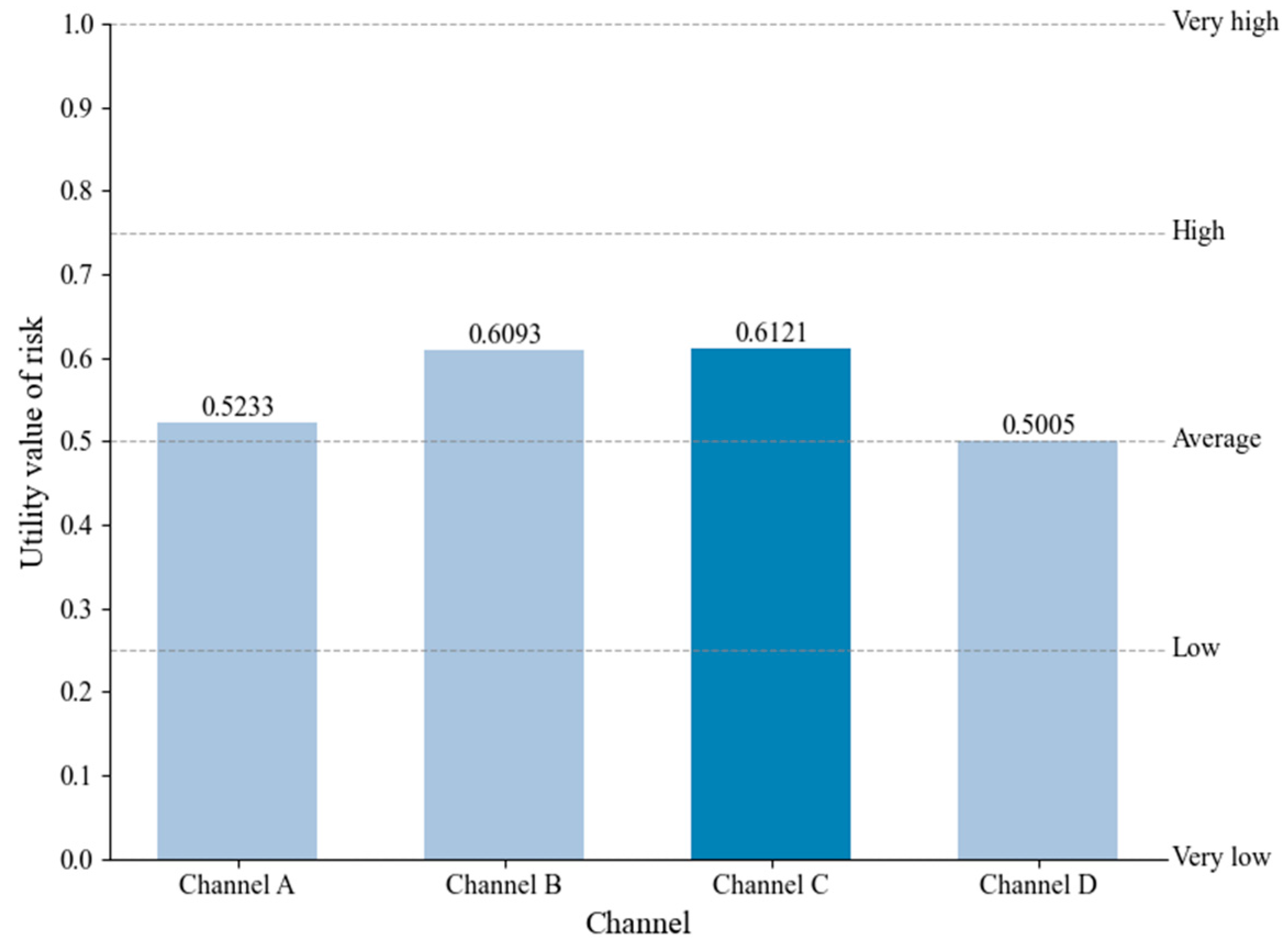

4.5. Evaluation of Navigational Risk in the Suez Canal

4.6. Implications

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- This study fully takes into account the navigational risk characteristics of ships in one-way channels, and the addition of two innovative indicators, “effective width of channel” and “time division”, enhances the applicability and practicality of the established model to the risk evaluation system of one-way channels.

- (2)

- The navigational risk evaluation model for one-way channels, developed using the Evidential Reasoning (ER) method in this study, effectively balances the objectivity of data with the subjectivity of expert judgment, thereby addressing the uncertainty inherent in expert knowledge.

- (3)

- In this study, the Suez Canal, which is an important strategic channel, is taken as the object of study, and the whole one-way channel is divided into four sub-channels for investigation. The results show that Channel C, where the grounding accident of the “Ever Given” ship occurred, is the sub-channel with the highest risk utility value. In addition, the applicability of the model is verified in the context of four ship groundings that occurred in the Suez Canal during the period 2021–2023.

- (4)

- In order to provide stakeholders with more reasonable and feasible suggestions, this study takes a 100,000 DWT container ship as the standard ship to study the influence of ships with different draughts on the navigational risk level of the channel, and the final results show that the navigational risk level of the channel can be effectively reduced when the ratio of ship draught to water depth of the channel is kept between 0.3 and 0.8. Therefore, large container ships should choose the waiting tide through the channel as much as possible.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- One-Way Channel Navigational Risk Assessment System Expert Survey Questionnaire.

- Dear Esteemed Expert,

| Criteria | Index | Score |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrometeorology (A1) | Visibility (A11) | |

| Wind (A12) | ||

| Current (A13) | ||

| Precipitation (A14) | ||

| Traffic conditions (A2) | Time division interval (A21) | |

| Traffic density (A22) | ||

| Vessel Speed (A23) | ||

| Aids to navigation conditions (A3) | Traffic management (A31) | |

| Aids to navigation (A32) | ||

| Communication Reliability (A33) | ||

| Channel environment (A4) | Channel depth (A41) | |

| Channel length (A42) | ||

| Effective width of the channel (A43) | ||

| Ship overtaking ratio (A44) |

References

- Chen, X.; Wu, H.; Han, B.; Liu, W.; Montewka, J.; Liu, R.W. Orientation-aware ship detection via a rotation feature decoupling supported deep learning approach. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 125, 106686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNCTAD. Trade and Development Report 2021; United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://unctad.org/publication/trade-and-development-report-2021 (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Topham, G. How the Suez Canal Blockage Can Seriously Dent World Trade. 2021. Available online: https://www.inkl.com/news/how-the-suez-canal-blockage-can-seriously-dent-world-trade (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Fan, S.Q.; Yang, Z.L.; Wang, J.; Marsland, J. Shipping accident analysis in restricted waters: Lesson from the Suez Canal blockage in 2021. Ocean Eng. 2022, 266, 113119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.Q.; Yang, Z.L.; Blanco-Davis, E.; Zhang, J.F.; Yan, X.P. Analysis of maritime transport accidents using Bayesian networks. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part O J. Risk Reliab. 2020, 234, 439–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.M.; Wong, E.Y. Suez Canal blockage: An analysis of legal impact, risks and liabilities to the global supply chain. MATEC Web Conf. 2021, 339, 01019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.J.; Zhang, X.Y.; Yang, B.D.; Wang, N.N. Vessel traffic scheduling optimization for restricted channel in ports. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 152, 107014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z. Ship navigation experience through the Suez Canal. Navig. China 1994, 1, 68–81. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Elidolu, G.; Sezer, S.I.; Akyuz, E.; Aydin, M.; Gardoni, P. A comprehensive risk analysis for cargo leakage pollution at tanker ship manifold using cloud modelling and Bayesian belief network approach. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2025, 219, 118238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.X.; Lu, J. Strait/canal security assessment of the Maritime Silk Road. Int. J. Ship. Trans. Log. 2018, 10, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhu, J.; Zhu, J.; Huang, C. Post-evaluation of navigation safety with the implementation of ship routing based on matter element method. Saf. Environ. Eng. 2019, 26, 181–186. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, D.; Wan, H.; Meng, B.; Xiong, F.; He, Y. Risk assessment of two-way navigation of the inbound and outbound channels of Fangcheng Port based on Fuzzy Hierarchical Analysis method. China Water Transp. 2020, 20, 12–13. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.F.; Huang, L.W.; Shen, G.H.; Jia, M.M. A risk evaluation model for channel navigation based on the gray-fuzzy theory. Eurasip. J. Wirel. Commun. Netw. 2018, 2018, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B. Grey Fuzzy Pre-Evaluation of the Navigation Safety of Compound Channels in Tianjin Port. Master’s Thesis, Dalian Maritime University, Dalian, China, 2010. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K.; Fan, Z.; Zhang, Y. Research of assessment on compound channel establishment based on SPA-AHP method. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Traffic Engineering and Transportation System (ICTETS 2021), Chongqing, China, 24–26 September 2021; p. 12058. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, X.; Shen, H.; Gao, C.; Shao, H. Application of extension superiority in harbor channel navigation risk evaluation. Saf. Environ. Eng. 2018, 25, 145–149. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, D.; Wen, Y. Risk evaluation of waterway environment based on entropy weight and matter element model. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. 2014, 38, 1158–1162. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gan, W.D.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Li, Y.W. Navigation risk evaluation for channels based on the Belief Rule Base. In Proceedings of the Civil Engineering and Urban Planning IV: 4th International Conference on Civil Engineering and Urban Planning (CEUP), Beijing, China, 25–27 July 2015; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, B.; Ma, Q.; Jiang, F.; Xu, Y. Risk assessment of the harbor approach channels based on the entropy weight and fuzzy evaluation model. J. Saf. Environ. 2017, 17, 2125–2128. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L.; Zhang, H.; Liu, W.; Chen, F. Research on risk assessment and control of inland navigation safety. Int. J. Syst. Assur. Eng. Manag. 2018, 9, 729–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Jiang, F.; Ma, Q.; Ma, Y.; Zhong, Q.; Meng, B. Environment risk evaluation for channel piloting based on entropy weight and matter-element model. Navig. China 2017, 40, 44–49. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Park, Y.; Kim, J.; Aydogdu, V. A study on the development the maritime safety assessment model in Korea waterway. J. Navig. Port Res. 2013, 37, 567–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luong, T.N.; Hwang, S.; Im, N. Harbour Traffic Hazard Map for real-time assessing waterway risk using Marine Traffic Hazard Index. Ocean. Eng. 2021, 239, 109884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamugi, J.W.; Camliyurt, G.; Sakar, C.; Park, S.; Park, Y.; Aydin, M.; Kim, D. Harbour Traffic Hazard Map for real-time assessing domestic ferry accident causes in Kenya’s Likoni ferry route using fuzzy Bayesian network. Ocean. Eng. 2025, 340, 122388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Liu, C.; Ding, F. A fuzzy assessment model of steering safety of the vessel in the gat. Chin. J. Ship Res. 2010, 5, 48–51. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.L.; Li, Z.C.; Wang, Y.D.; Sheng, D.A. Short-term berth planning and ship scheduling for a busy seaport with channel restrictions. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2021, 154, 102467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.D.; Shi, G.Y.; Kang, Z. Fuzzy Scheduling Problem of Vessels in One-Way Waterway. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, K.; Yang, X.; Yang, F.; Xugang, Y. Probability of ship speed reducing in one-way channel. Navig. China 2018, 41, 42–46. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, R. Integrated Optimization of Continuous Berth Allocation and Ship Scheduling under One-Way Channel. Comput. Eng. Appl. 2022, 58, 246–255. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xu, G.; Guo, T.; Wu, Z. Optimum scheduling model for ship in/outbound harbor in one-way traffic fairway. J. Dalian Marit. Univ. 2008, 34, 150–153. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, H.X.; Liu, B.L.; Deng, C.Y.; Feng, P.P. Ship scheduling optimization in one-way channel bulk harbor. Oper. Res. Manag. Sci. 2018, 27, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z. Ship Maneuvering; Dalian Maritime University Press: Dalian, China, 2012; pp. 40–70. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ceylan, B.O.; Sezer, S.İ.; Akyuz, E. An integrated system theoretic accident model and process (STAMP)–Bayesian network (BN) for safety analysis of water mist system on tanker ships. Appl. Ocean Res. 2024, 145, 103837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceylan, B.O.; Celik, M.S.; Akyar, D.A. ANP extended STAMP model for complex system accident analysis: A real case of ship main engine failure. J. Mar. Eng. Technol. 2025, 24, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceylan, B.O. Control theory-based fuzzy Fine-Kinney risk assessment for boiler automation system from the maritime autonomous surface ships (MASS) perspective. Ocean Eng. 2025, 298, 118563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydogdu, Y.V. Utilization of full-mission ship-handling simulators for navigational risk assessment: A case study of large vessel passage through the Istanbul Strait. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Xi, Y.; Pedrycz, W. Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA) for Risk Assessment Based on Interval Type-2 Fuzzy Evidential Reasoning Method. Appl. Soft Comput. 2020, 89, 106134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.H.; Kontovas, C.; Yu, Q.; Yang, Z.L. Risk assessment of the operations of maritime autonomous surface ships. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2021, 207, 107324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Teixeira, A.P.; Liu, K.; Rong, H.; Soares, C.G. An Integrated Dynamic Ship Risk Model Based on Bayesian Networks and Evidential Reasoning. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2021, 216, 107993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ma, X.X.; Qiao, W.L.; Han, B. On the determination and rank for the environmental risk aspects for ship navigating in the Arctic based on big Earth data. Risk Anal. 2022, 43, 2186–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Qiao, W. Architecture Analysis of Arctic Shipping Routes Safety System Based on Fuzzy AHP. Navig. China 2020, 43, 1–6+13. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wan, C.P.; Yan, X.P.; Zhang, D.; Qu, Z.H.; Yang, Z.L. An advanced fuzzy Bayesian-based FMEA approach for assessing maritime supply chain risks. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2019, 125, 222–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.J.; Xia, G.Q.; Zhao, J.; Wang, J.; Yang, Z.L.; Loughney, S.; Fang, S.; Zhang, S.; Xing, Y.; Liu, Z. A novel method for the risk assessment of human evacuation from cruise ships in maritime transportation. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2023, 230, 108887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.M.; Shi, Y.; Dong, P.W. Public blockchain evaluation using entropy and TOPSIS. Expert Syst. Appl. 2019, 117, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.Z.; Lu, J.; Qu, Z.H.; Yang, Z.L. Port vulnerability assessment from a supply Chain perspective. Ocean. Coast Manag. 2021, 213, 105851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.L.; Wang, J. Use of fuzzy risk assessment in FMEA of offshore engineering systems. Ocean Eng. 2015, 95, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.Q.; Yang, J.X.; Jian, J. Analysis of academic meanings of severe weather and rough sea state. China Navig. 2021, 44, 14–20+26. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.Y.; Wang, H.; Meng, Q.; Xie, H.B. Ship accident consequences and contributing factors analyses using ship accident investigation reports. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part O J. Risk Reliab. 2019, 233, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Wang, F.; Wu, Z. Vessel traffic safety evaluation method. Safety Index Method. J. Dalian Mar. Coll. 1992, 4, 337–341. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Nie, Z.Y.; Jiang, Z.L.; Chu, X.M.; Yu, Z. Efficacy Evaluation of Maritime AtoN by Fuzzy AHP Approach. In Proceedings of the 2019 5th International Conference on Transportation Information and Safety (ICTIS), Liverpool, UK, 14–17 July 2019; pp. 247–251. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, H.; Wu, Z. Comprehensive evaluation of the environmental hazards of ships in the waters of the port channels. J. Dalian Marit. Univ. 1998, 3, 17–20. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Liu, S.; Liu, R.W.; Wu, H.; Han, B.; Zhao, J. Quantifying Arctic oil spilling event risk by integrating an analytic network process and a fuzzy comprehensive evaluation model. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2022, 228, 106326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughney, S.; Wang, J.; Matellini, D.B.; Nguyen, T.T. Utilizing the evidential reasoning approach to determine a suitable wireless sensor network orientation for asset integrity monitoring of an offshore gas turbine driven generator. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 185, 115583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.P.; Zhang, D.; Yan, X.P.; Yang, Z.L. A novel model for the quantitative evaluation of green port development—A case study of major ports in China. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2018, 61, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G. How to cross the Suez Canal safely and smoothly. Tianjin Navig. 2020, 2, 5–8. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Y.; Wu, Z. Safety analysis of ship navigation environment system in Xiamen port. J. Dalian Marit. Univ. 2001, 1, 1–4. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Suez Canal Authority (SCA). Available online: https://www.suezcanal.gov.eg (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Grosfeld-Nir, A.; Ronen, B.; Kozlovsky, N. The Pareto managerial principle: When does it apply? Int. J. Prod. Res. 2007, 45, 2317–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Wang, X.; Feng, Y.; Zhou, J.; Yang, Z. Improving maritime accident severity prediction accuracy: A holistic machine learning framework with data balancing and explainability techniques. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2026, 266, 111648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cao, W.; Li, T.; Feng, Y.; Uğurlu, Ö.; Wang, J. An Integrated Multidimensional Model for Heterogeneity Analysis of Maritime Accidents during Different Watchkeeping Periods. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2025, 264, 107625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Object of Research | Author | Measurement Model |

|---|---|---|

| Undefined Channel | Tang et al. [16] | Extension superiority theory |

| Wu & Wen [17] | Entropy and matter–element | |

| Gan et al. [18] | Belief rule base and evidential reasoning | |

| Compound Channel | Liu et al. [15] | Sep pair analysis—analytic hierarchy process |

| Meng et al. [19] | Reason model | |

| Li [14] | Gray theory and fuzzy comprehensive evaluation | |

| Two-way Channel | Liang et al. [12] | Fuzzy hierarchical analysis process |

| Li et al. [11] | Matter—element | |

| Sun et al. [20] | Fuzzy comprehensive evaluation | |

| Wang et al. [13] | Set-valued statistics and gray theory | |

| Wang et al. [21] | Entropy and matter—element | |

| Park Y S et al. [22] | Mathematical model | |

| Luong et al. [23] | Traffic hazard index | |

| Wamugi et al. [24] | Fuzzy Bayesian network | |

| Narrow Channel | Shi et al. [25] | AHP and fuzzy mathematics |

| Item | Age | Occupation | Educational Level | Certificate Rank | Job Tenure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expert 1 | 41 | Manager of shipping company | Masters of navigation technology | 2nd Officer | He has more than 8 years of experience in container operation management. |

| Expert 2 | 50 | Senior seafarer | Bachelors of navigation | Chief Officer | He has more than 10 years of experience in container ship transportation. |

| Expert 3 | 51 | Senior seafarer | Bachelors of navigation | Senior Captain | He has more than 10 years of working experience. |

| Expert 4 | 46 | Professor | PhD of navigation | Senior Captain | He has more than 10 years of experience in navigation safety research, especially container safety. |

| Expert 5 | 53 | Safety manager | Masters of navigation technology | Senior Captain | He has more than 10 years of experience in the field of channel navigation safety. |

| Index | Type | Attribute | Calculation Criterion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrometeorology (A1) | |||

| Visibility (A11) | Cost-based | Uncertainty | Inverse of the annual average minimum visibility |

| Wind (A12) | Cost-based | Uncertainty | The annual average maximum sustained wind speed |

| Current (A13) | Cost-based | Uncertainty | The maximum current speed |

| Traffic conditions (A2) | |||

| Time division interval (A21) | Cost-based | Uncertainty | Channel utilization rate |

| Traffic density (A22) | Cost-based | Uncertainty | Traffic density converted by ship conversion factor |

| Aids to navigation conditions (A3) | |||

| Traffic management (A31) | Benefit-based | Uncertainty | - |

| Aids to navigation (A32) | Benefit-based | Uncertainty | - |

| Channel environment (A4) | |||

| Channel depth (A41) | Cost-based | Certainty | Ratio of water depth to ship draught |

| Channel length (A42) | Cost-based | Uncertainty | Ratio of channel length to channel width |

| Effective width of the channel (A43) | Cost-based | Uncertainty | Ratio of ship length to the effective channel width |

| Visibility Range (NM) | Scale |

|---|---|

| >10 | Clear |

| 2–10 | Moderate |

| <2 | Poor |

| ) | Relative Depth | Maneuverability |

|---|---|---|

| Deepwater | Basically, no effect | |

| Deeper water | Non-significant impact | |

| Medium water depth | General impact | |

| Shallow water | Significant impact | |

| Super shallow water | Very significant impact |

| Ship Length (l)/Effective Channel Width (W) | Water Type | Effect in Quay Wall | Maneuverability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Navigable waters | Ignorable | No effect | |

| Narrow waters | Existence | Some impact | |

| Super Narrow waters | Stronger | Obvious impact |

| Index | Type | Very High | High | Average | Low | Very Low |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visibility (A11) | Cost-based | |||||

| Wind (A12) | Cost-based | |||||

| Current (A13) | Cost-based | |||||

| Time division interval (A21) | Cost-based | |||||

| Traffic density (A22) | Cost-based | |||||

| Traffic management (A31) | Benefit-based | |||||

| Aids to navigation (A32) | Benefit-based | |||||

| Channel depth (A41) | Cost-based | |||||

| Channel length (A42) | Cost-based | |||||

| Effective channel width (A43) | Cost-based |

| Channel A | Channel B | Channel C | Channel D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visibility (km) | 2.51 | 2.51 | 2.51 | 2.51 |

| Wind (m/s) | 24.52 | 24.52 | 24.52 | 24.52 |

| Current (kn) | 2 | 2 | 1.5 | 2.5 |

| Channel A | Channel B | Channel C | Channel D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.97 | 2.66 | 2.97 | 2.66 |

(Num) | (kn) | (Time) | (n Mile) | (Day) | (n Mile) | ) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Channel A | 18,797.5 | 13.75 | 2 | 12.15 | 365 | 2.16 | 0.36 |

| Channel B | 18,797.5 | 13.75 | 2 | 42.39 | 365 | 2.16 | 0.45 |

| Channel C | 18,797.5 | 13.75 | 2 | 45.22 | 365 | 2.16 | 0.46 |

| Channel D | 18,797.5 | 13.75 | 2 | 4.35 | 365 | 2.16 | 0.35 |

| Channel Length (km) | Channel Width (m) | Channel Depth (m) | Effective Channel Width (m) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Channel A | 22.5 | 317 | 24 | 190 |

| Channel B | 78.5 | 345 | 22.5 | 121 |

| Channel C | 83.75 | 313 | 24 | 121 |

| Channel D | 8.05 | 360 | 23.5 | 190 |

| DWT | Ship Length (m) | Ship Width (m) | Full Draught (m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100,000 DWT | 346 | 45.6 | 14.5 |

| 70,000 DWT | 300 | 40.3 | 14.0 |

| 50,000 DWT | 293 | 32.3 | 13.0 |

| 10,000 DWT | 141 | 22.6 | 8.3 |

| Evaluation Indexes | Channel A | Channel B | Channel C | Channel D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visibility | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.40 |

| Wind | 24.52 | 24.52 | 24.52 | 24.52 |

| Current | 2 | 2 | 1.5 | 2.5 |

| Time division interval | 0.36 | 0.45 | 0.46 | 0.35 |

| Traffic density | 2.97 | 2.66 | 2.97 | 2.66 |

| Traffic management | 85 | 85 | 85 | 85 |

| Aids to navigation | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Channel depth | 0.60 | 0.64 | 0.60 | 0.62 |

| Channel length | 70.98 | 227.54 | 267.57 | 22.36 |

| Effective channel width | 1.82 | 2.86 | 2.86 | 1.82 |

| Evaluation Indexes | Channel A | Channel B | Channel C | Channel D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visibility | [0, 0.4, 0.6, 0, 0] M | [0, 0.4, 0.6, 0, 0] M | [0, 0.4, 0.6, 0, 0] M | [0, 0.4, 0.6, 0, 0] M |

| Wind | [0, 0, 0, 0, 1] T | [0, 0, 0, 0, 1] T | [0, 0, 0, 0, 1] T | [0, 0, 0, 0, 1] T |

| Current | [0, 0, 0.67, 0.33, 0] M | [0, 0, 0.67, 0.33, 0] M | [0, 0, 1, 0, 0] M | [0, 0, 0.33, 0.67, 0] H |

| Time division interval | [0.9, 0.1, 0, 0, 0] B | [0, 1, 0, 0, 0] L | [0, 0.8, 0.2, 0, 0] L | [1, 0, 0, 0, 0] B |

| Traffic density | [0, 0, 0.66, 0.34, 0] M | [0, 0.06, 0.94, 0, 0] M | [0, 0, 0.66, 0.34, 0] M | [0, 0.06, 0.94, 0, 0] M |

| Traffic management | [0, 0, 1, 0, 0] M | [0, 0, 1, 0, 0] M | [0, 0, 1, 0, 0] M | [0, 0, 1, 0, 0] M |

| Aids to navigation | [1, 0, 0, 0, 0] B | [1, 0, 0, 0, 0] B | [1, 0, 0, 0, 0] B | [1, 0, 0, 0, 0] B |

| Channel depth | [0, 0, 1, 0, 0] M | [0, 0, 1, 0, 0] M | [0, 0, 1, 0, 0] M | [0, 0, 1, 0, 0] M |

| Channel length | [0, 0.3, 0.7, 0, 0] M | [0, 0, 0, 0, 1] T | [0, 0, 0, 0, 1] T | [0.92, 0.08, 0, 0, 0] B |

| Effective channel width | [0, 0, 0, 0.36, 0.64] T | [0, 0, 0, 0, 1] T | [0, 0, 0, 0, 1] T | [0, 0, 0, 0.36, 0.64] T |

| Criterion Layer | Index Layer | Subjective Weighting | Objective Weighting | Comprehensive Weight | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrometeorology 0.2886 | Visibility 0.3347 | 0.0966 | 0.0980 | 0.0972 | 5 |

| Wind 0.4763 | 0.1375 | 0.1127 | 0.1276 | 2 | |

| Current 0.1890 | 0.0545 | 0.1128 | 0.0778 | 8 | |

| Traffic conditions 0.1807 | Time division interval 0.6861 | 0.1240 | 0.1060 | 0.1168 | 4 |

| Traffic density 0.3139 | 0.0567 | 0.1002 | 0.0741 | 9 | |

| Aids to navigation conditions 0.1357 | Traffic management 0.6380 | 0.0866 | 0.0736 | 0.0814 | 7 |

| Aids to navigation 0.3620 | 0.0491 | 0.0736 | 0.0589 | 10 | |

| Channel environment 0.3949 | Channel depth 0.4874 | 0.1925 | 0.1141 | 0.1611 | 1 |

| Channel length 0.1766 | 0.0697 | 0.1087 | 0.0853 | 6 | |

| Effective channel width 0.3360 | 0.1327 | 0.1002 | 0.1197 | 3 |

| Target Channels | Evaluation Set Belief Degree | Comments | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very Low | Low | Average | High | Very High | ||

| Channel A | [0.1339 | 0.1492 | 0.4363 | 0.0509 | 0.2297] | Average |

| Channel B | [0.0238 | 0.2422 | 0.3705 | 0 | 0.3635] | Average |

| Channel C | [0.0237 | 0.2398 | 0.3646 | 0.0077 | 0.3641] | Average |

| Channel D | [0.2266 | 0.1211 | 0.3751 | 0.0583 | 0.2389] | Average |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, J.; Xie, W.; Xie, H.; Sun, Y.; Wang, X. Navigational Risk Evaluation of One-Way Channels: Modeling and Application to the Suez Canal. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1864. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13101864

Yang J, Xie W, Xie H, Sun Y, Wang X. Navigational Risk Evaluation of One-Way Channels: Modeling and Application to the Suez Canal. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(10):1864. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13101864

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Jiaxuan, Wenzhen Xie, Hongbin Xie, Yao Sun, and Xinjian Wang. 2025. "Navigational Risk Evaluation of One-Way Channels: Modeling and Application to the Suez Canal" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 10: 1864. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13101864

APA StyleYang, J., Xie, W., Xie, H., Sun, Y., & Wang, X. (2025). Navigational Risk Evaluation of One-Way Channels: Modeling and Application to the Suez Canal. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(10), 1864. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13101864