Eating Hamburgers Slowly and Sustainably: The Fast Food Market in North-West Italy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

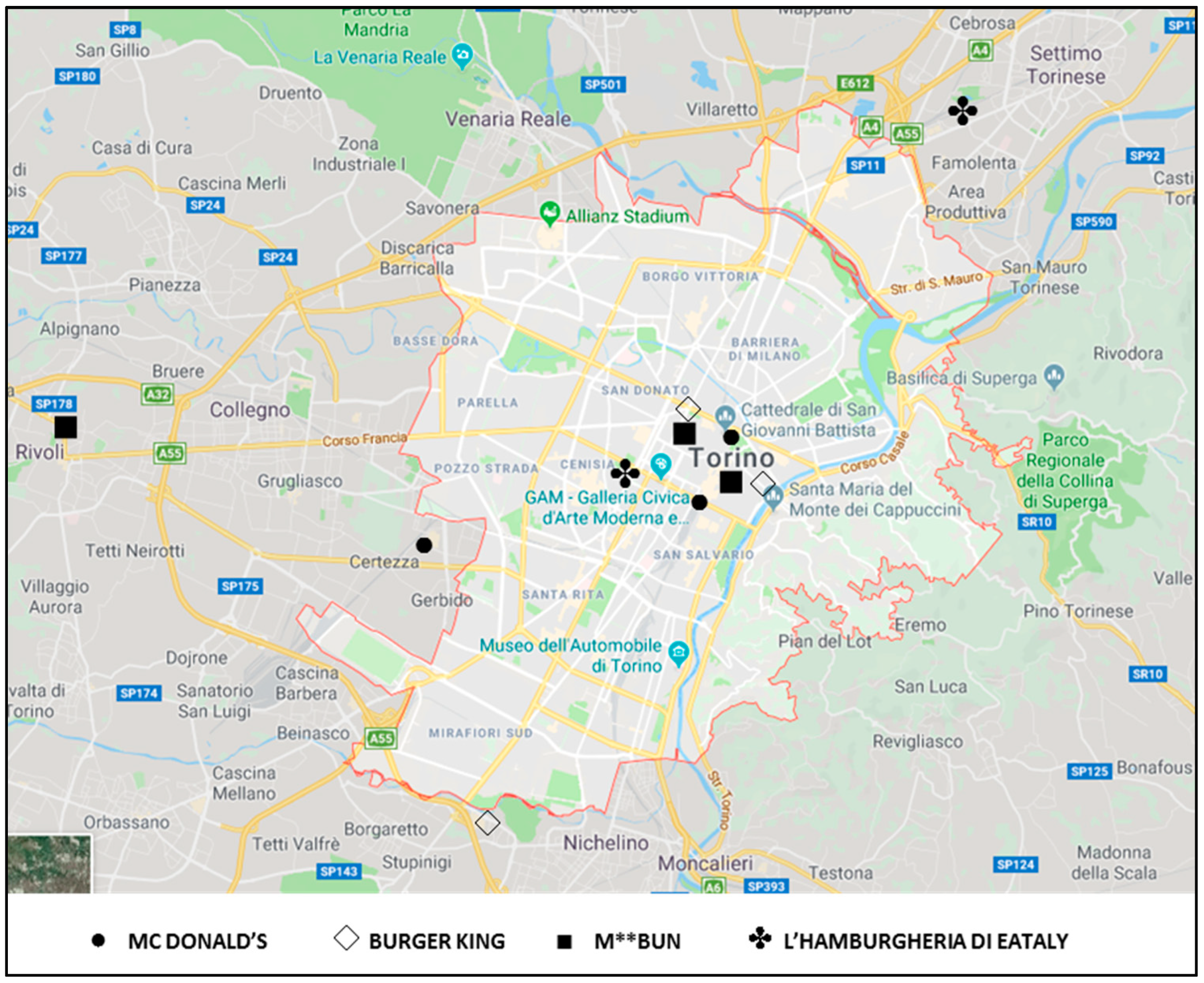

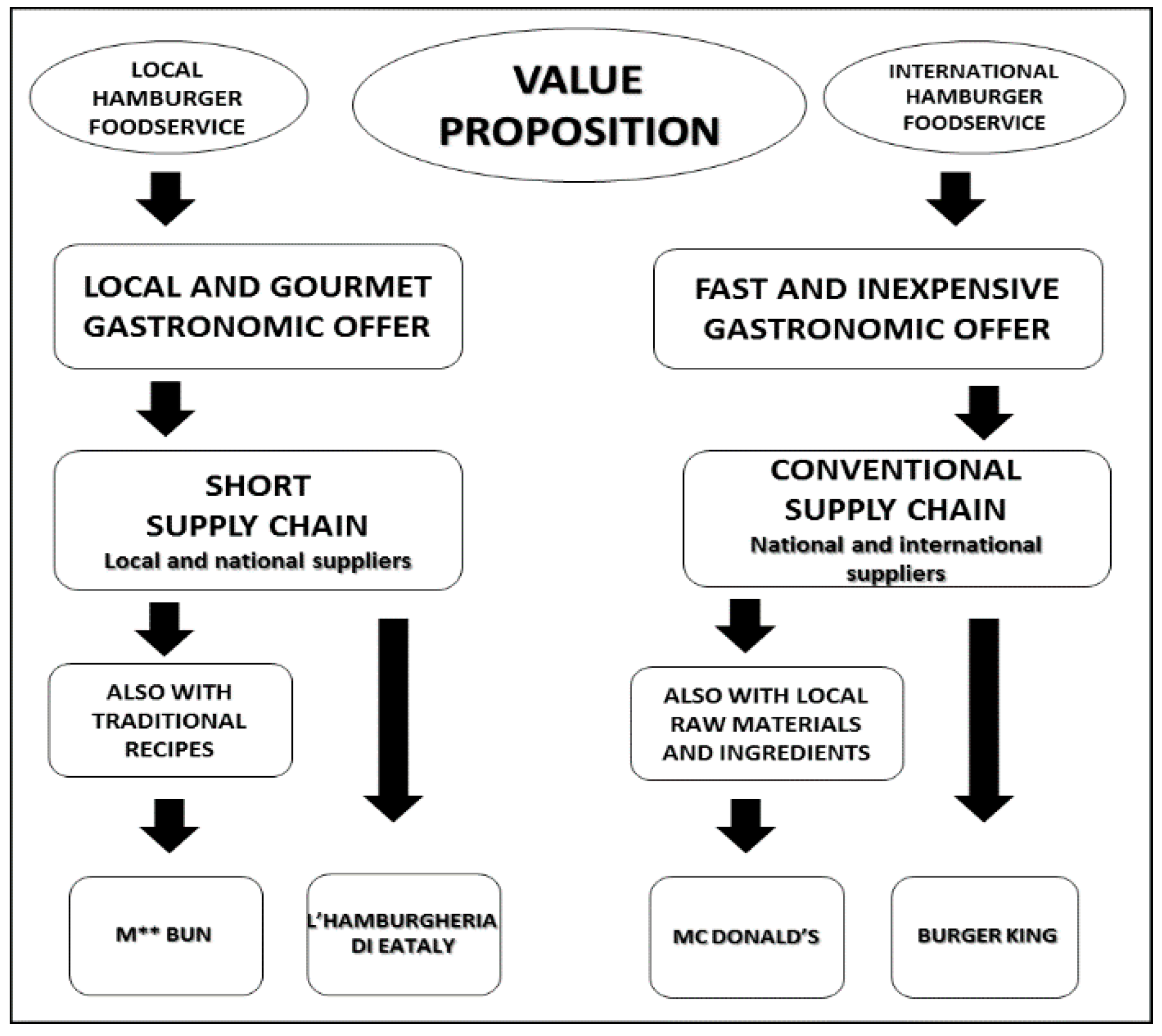

3.1. International Hamburger Foodservice (IHF)

3.1.1. McDonald’s

3.1.2. Burger King

3.2. Local Hamburger Foodservice (LHF)

3.2.1. M** Bun

3.2.2. L’Hamburgheria di Eataly

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions, Implications, and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Petrini, C. Buono Pulito e Giusto. Nuovi Principi di Neogastronomia; Giulio Einaudi Editore: Torino, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bentivoglio, D.; Savini, S.; Finco, A.; Bucci, G.; Boselli, E. Quality and origin of mountain food products: The new European label as a strategy for sustainable development. J. Mt. Sci. 2019, 16, 428–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, C.; Mendes, L. Protected Designation of Origin (PDO), Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) and Traditional Speciality Guaranteed (TSG): A bibliometric analysis. Food Res. Int. 2018, 103, 492–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonadonna, A.; Macar, L.; Peira, G.; Giachino, C. The Dark Side of the European Quality Schemes: The Ambiguous Life of the Traditional Specialities Guaranteed. Qual.-Access Success 2017, 18, 92–98. [Google Scholar]

- Finco, A.; Bentivoglio, D.; Bucci, G. A Label for Mountain Products? Let’s Turn it over to Producers and Retailers. Qual.-Access Success 2017, 18, 198–205. [Google Scholar]

- Grunert, K.G.; Aachmann, K. Consumer reactions to the use of EU quality labels on food products: A review of the literature. Food Control 2015, 59, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajdukiewicz, A. European Union agri-food quality schemes for the protection and promotion of geographical indications and traditional specialities: An economic perspective. Folia Hortic. 2014, 26, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almli, V.L.; Verbeke, W.; Vanhonacker, F.; Næs, T.; Hersleth, M. General image and attribute perceptions of traditional food in six European countries. Food Qual. Prefer. 2011, 22, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, L.; Claret, A.; Verbeke, W.; Enderli, G.; Zakowska-Biemans, S.; Vanhonacker, F.; Hersleth, M. Perception of traditional food products in six European regions using free word association. Food Qual. Prefer. 2010, 21, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barham, E. Translating terroir: The global challenge of French AOC labeling. J. Rural Stud. 2003, 19, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheribi, E. Corporate social responsibility in foodservice business in Poland on selected examples. Eur. J. Serv. Manag. 2017, 23, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, S. Glocalization in fast food chains: A case study of Mcdonald’s. Strateg. Mark. Manag. Tactics Serv. Ind. 2017, 330–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashif, M.; Awang, Z.; Walsh, J.; Altaf, U. I’m loving it but hating US: Understanding consumer emotions and perceived service quality of US fast food brands. Br. Food J. 2015, 117, 2344–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rarick, C.; Falk, G.; Barczyk, C. The little bee that could: Jollibee of the Philippines v. Mcdonald’s. J. Int. Acad. Case Stud. 2012, 18, 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, R.J. Fast food and animal rights: An examination and assessment of the industry’s response to social pressure. Bus. Soc. Rev. 2008, 113, 301–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignali, C. McDonald’s: “Think global, act local”—The marketing mix. Br. Food J. 2011, 103, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappella, F.; Giaccaria, P.; Peira, G. La filiera della carne di piemontese: Scenari possibili. Politiche Piemonte 2015, 36, 6–12. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald’s Italia. Available online: http://www.mcdonalds.it/sites/default/files/mcdonalds_mcitaly_cs_chianina_e_romagnola.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2019).

- Bernues, A.; Olaizola, A.; Corcoran, K. Labelling information demanded by European consumers and relationship with purchasing motives, quality and safety of meat. Meat Sci. 2003, 3, 1095–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ittersum, K.; Meulemberg, M.T.G.; Van Trip, H.C.M.; Candel, M.J.J. Consumers’ appreciation of Regional certification labels: A pan-european study. J. Agric. Econ. 2007, 58, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banterle, A.; Stranieri, S. Information, labelling, and vertical coordination: An analysis of the Italian meat supply networks. Agribusiness 2008, 2, 320–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhonacker, F. How European Consumer define the concept of Traditional food: Evidence from survey in six countries. Agribusiness 2010, 26, 453–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carzedda, M.; Marangon, F.; Nassivera, F.; Troiano, S. Consumer satisfaction in Alternative Food Networks (AFNs): Evidence from Northern Italy. J. Rural Stud. 2018, 64, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, C.; Costa, A.; Balzaretti, C.M.; Russo, V.; Tedesco, D.E.A. Survey on food preferences of university students: From tradition to new food customs? Agriculture (Switzerland) 2018, 8, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedin, E.; Torricelli, C.; Gigliano, S.; De Leo, R.; Pulvirenti, A. Vegan foods: Mimic meat products in the Italian market. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2018, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annunziata, A.; Agovino, M.; Mariani, A. Sustainability of Italian families’ food practices: Mediterranean diet adherence combined with organic and local food consumption. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 206, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tregear, A.; Kuznesof, S.; Moxey, A. Policy initiatives for regional foods: Some insights from consumer research. Food Policy 1998, 23, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belliveau, S. Resisting global, buying local: Goldschmidt revisited. Great Lake Geogr. 2005, 1, 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- DuPuis, E.M.; Goodman, D. Should we go home to eat? Toward a reflexive politics of localism. J. Rural Stud. 2005, 21, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.; Miller, S. The impacts of local markets: A review of research on farmers markets and community supported agriculture (CSA). Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2008, 90, 1296–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnell, S.M. The local traveler: Farming, food and place in state and provincial tourisme guides, 1993–2008. J. Cult. Geogr. 2011, 28, 281–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuna, C.; Sarah, M.A.; Arielle, C. From short food supply chains to sustainable agriculture in urban food systems: Food democracy as a vector of transition. Agriculture (Switzerland) 2016, 6, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, E.; Keech, D.; Maye, D.; Barjolle, D.; Kirwan, J. Comparing the sustainability of local and global food chains: A case study of cheese products in Switzerland and the UK. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2016, 8, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Asselt, E.D.; Van der Fels-Klerx, H.J.; Marvin, H.J.P.; Van Bokhorst-van de Veen, H.; Groot, M.N. Overview of food Safety Hazards in the European Dairy Supply Chain. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2017, 16, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timpanaro, G.; Foti, V.T.; Scuderi, A.; Schippa, G.; Branca, F. New food supply chain systems based on a proximity model: The case of an alternative food network in the Catania urban area. Acta Hortic. 2018, 1215, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkley, C. The smallworld of the alternative food network. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2018, 10, 2921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intzelt, A.; Hilton, J. Technology Transfer: From Invention to Innovation; Kluver Academic Publisher: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Antonelli, G. Marketing Agroalimentare: Specificità e Temi di Analisi; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Finco, A.; Bentivoglio, D.; Bucci, G. Lessons of Innovation in the Agrifood Sector: Drivers of Innovativeness Performances. Econ. Agro-Aliment. Food Econ. 2018, 20, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrontis, D.; Bresciani, S.; Giacosa, E. Tradition and innovation in Italian wine family businesses. Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 1883–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bresciani, S.; Thrassou, A.; Vrontis, D. Change through innovation in family businesses: Evidence from an Italian sample. World Rev. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 4, 195–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rama, R. Empirical study on sources of innovation in international food and beverage industry. Agribusiness 1996, 12, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traill, W.B.; Meulenberg, M. Innovation in the food industry. Agribusiness 2005, 18, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capitanio, F.; Coppola, A.; Pascucci, S. Indications for drivers of innovation in the food sector. Br. Food J. 2009, 111, 820–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakki, M.; Sanjit, S.; Stanley, S. Marketing of High-Technology Products and Innovations; Pearson: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dadura, A.M.; Lee, T.R. Measuring the innovation ability of Taiwan’s food industry using DEA. Innovation 2011, 24, 151–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcese, G.; Flammini, S.; Lucchetti, M.C.; Martucci, O. Evidence and Experience of Open Sustainability Innovation Practices in the Food Sector. Sustainability 2015, 7, 8067–8090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boccia, F.; Covino, D. Innovation and sustainability in agri-food companies: The role of quality. Rivista di Studi sulla Sostenibilità 2016, 1, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, L.; Dolors Guardia, M.; Xicola, J.; Verbeke, W.; Vanhonacker, F.; Zakowska-Biemans, S.; Sajdakowska, M.; Sulmont-Rossé, C.; Issanchou, S.; Contel, M.; et al. Consumer-driven definition of traditional food products and innovation in traditional foods. A qualitative cross-cultural study. Appetite 2009, 52, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSoucey, M. Gastronationalism: Food Traditions and Authenticity Politics in the European Union. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2010, 75, 432–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Corte, V.; Del Gaudio, G.; Sepe, F. Innovation and tradition-based firms: a multiple case study in the agro-food sector. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 1295–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordana, J. Traditional foods: Challenges facing the European food industry. Food Res. Int. 2000, 33, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schamel, G. Auction markets for specialty food products with Geographical Indications. Agric. Econ. 2007, 37, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, B.; Gokovali, U. Geographical indications: The Aspects of Rural Development and Marketing through the Traditional Products. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci.. 2012, 62, 761–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo, I.; Cristóvao, A.; Tibério, M.L.; Baptista, A.; Maggione, L.; Pires, M. The Portuguese Agrifood Traditional Products: Main constraints and challenges. Revista de Economia e Sociologia Rural 2015, 53, S023–S032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcoz, E.M.; Melewar, T.C.; Dennis, C. The Value of Region of Origin, Producer and Protected Designation of Origin Label for Visitors and Locals: The Case of Fontina Cheese in Italy. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 18, 236–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonadonna, A.; Duglio, S. A Mountain Niche Production: The case of Bettelmatt cheese in the Antigorio and Formazza Valleys (Piedmont - Italy). Qual.-Access Success 2016, 17, 80–86. [Google Scholar]

- Harrington, R.J. The Culinary Innovation Process–A Barrier to Imitation Part, I. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2004, 7, 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuebling, M.; Behnke, C.; Hammond, R.; Sydnor, S.; Almanza, B. On tap: Foodservice operators’ perceptions of a wine innovation. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2017, 20, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.I.A. Collaborative product innovation in the food service industry: Do too many cooks really spoil the broth? Open Innov. Food Beverage Ind. 2013, 154–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkelsen, B.E.; Kristensen, N.H.; Nielsen, T. Innovation processes in large-scale public foodservice-case findings from the implementation of organic foods in a Danish county. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2006, 8, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheribi, E. Innovation strategies in restaurant business. Econ. Organ. Enterp. 2017, 11, 125–135. [Google Scholar]

- Maltese, F.; Giachino, C.; Bonadonna, A. The Safeguarding of Italian Eno-Gastronomic Tradition and Culture around the World: A Strategic Tool to enhance the Restaurant Services. Qual.-Access Success 2016, 17, 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Mkono, M. Slow food versus fast food: A Zimbabwean case study of hotelier perspectives. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2012, 12, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordin, V.; Trabskaya, J.; Zelenskaya, E. The role of hotel restaurants in gastronomic place branding. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2016, 10, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrykowski, B. You Are What You Eat: The Social Economy of the Slow Food Movement. Rev. Soc. Econ. 2004, 62, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkins, W. Out of time: Fast subjects and slow living. Time Soc. 2004, 13, 363–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tencati, A.; Zsolnai, L. Collaborative Enterprise and Sustainability: The Case of Slow Food. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 110, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gava, O.; Galli, F.; Bartolini, F.; Brunori, G. Linking sustainability with geographical proximity in food supply chains. An indicator selection framework. Agriculture (Switzerland) 2018, 8, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, A. Foods and places: Comparing different supply chains. Agriculture (Switzerland) 2018, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peri, C. The universe of food quality. Food Qual. Prefer. 2006, 17, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massini, R. Prospettive di R&S per l’ industria alimentare. Industrie Alimentari 2010, 49, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Parkins, W.; Craig, G. Culture and the politics of alternative food networks. Food Cult. Soc. 2009, 12, 77–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massa, S.; Testa, S. The role of ideology in brand strategy: The case of a food retail company in Italy. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2012, 40, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, J. The logic of the gift: The possibilities and limitations of Carlo Petrini’s Slow Food alternative. Agric. Hum. Values 2013, 30, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastiani, R.; Montagnini, F.; Dalli, D. Ethical Consumption and New Business Models in the Food Industry. Evidence from the Eataly Case. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 473–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoldi, B.; Giachino, C.; Stupino, M. Innovative approaches to brand value and consumer perception: The Eataly case. J. Cust. Behav. 2015, 14, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alfiero, S.; Lo Giudice, A.; Bonadonna, A. Street food and innovation: The food truck phenomenon. Br. Food J. 2017, 119, 2462–2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilli, M.; Ferrari, S. Tourism in multi-ethnic districts: The case of Porta Palazzo market in Torino. Leis. Stud. 2018, 37, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonadonna, A.; Matozzo, A.; Giachino, C.; Peira, G. Farmer behavior and perception regarding food waste and unsold food. Br. Food J. 2018, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfiero, S.; Bonadonna, A.; Cane, M.; Lo Giudice, A. Street food as a tool for promoting tradition, territory and tourism. Tour. Anal. 2019, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, A. The role of mystery shopping in the measurement of service performance. Manag. Serv. Qual. 1998, 8, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rood, A.S.; Dziadkowiec, J. Cross Cultural Service Gap Analysis: Comparing SERVQUAL Customers and IPA Mystery Shoppers. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2013, 16, 359–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.-S.; Tsai, C.-T.S. The Implication of Mystery Shopping Program in Chain Restaurants: Supervisors’ Perception. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2014, 17, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kučerová, V. Mystery shopping as a tool for improvement of shopping conditions. In Proceedings of the 25th International Business Information Management Association Conference-Innovation Vision 2020: From Regional Development Sustainability to Global Economic Growth, IBIMA, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 7–8 May 2015; pp. 1040–1049. [Google Scholar]

- Szente, V.; Szigeti, O.; Polereczki, Z.; Varga, Á.; Szakály, Z. Towards a new strategy for organic milk marketing in Hungary. Acta Aliment. 2015, 44, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wiele, T.V.D.; Hesselink, M.; Iwaarden, J.V. Mystery shopping: A tool to develop insight into customer service provision. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2005, 16, 529–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zeng, Z.E.; Honig, B. How should entrepreneurship be taught to students with diverse experience? a set of conceptual models of entrepreneurship education. Adv. Entrep. Firm Emerg. Growth 2016, 18, 237–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haertel, T.; Terkowsky, C.; May, D. The shark tank experience: How engineering students learn to become entrepreneurs. In Proceedings of the ASEE Annual Conference and Exposition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 26–29 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hoveskog, M.; Halila, F.; Danilovic, M. Early Phases of Business Model Innovation: An Ideation Experience Workshop in the Classroom. Decis. Sci. J. Innov. Educ. 2015, 13, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojasalo, J.; Ojasalo, K. Service logic business model canvas for lean development of SMEs and start-ups. In Handbook of Research on Entrepreneurship in the Contemporary Knowledge-Based Global Economy; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2015; pp. 217–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, J.; Ali, M.M. Business model canvas as tool for SME. In IFIP International Conference on Advances in Production Management Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 415, pp. 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, J.; Dahlan, A.R.A. Designing business models options for University of the Future. In Proceedings of the 2016 4th IEEE International Colloquium on Information Science and Technology (CiSt), Tangier, Morocco, 24–26 October 2016; pp. 600–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skripkin, K. How environment influences on organizational design of educational institution: New analytical instruments. CEUR Workshop Proc. 2016, 1761, 482–493. [Google Scholar]

- Rytkönen, E.; Nenonen, S. The Business Model Canvas in university campus management. Intell. Build. Int. 2014, 6, 138–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, W.F.; Hoyos Concha, J.L. Business model for initiatives in science, technology and innovation. An application for the fish agroindustry of Cauca. Vitae 2016, 23, s410. [Google Scholar]

- Martikainen, A.; Niemi, P.; Pekkanen, P. Developing a service offering for a logistical service provider-Case of local food supply chain. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfiero, S.; Wade, B.; Taliano, A.; Bonadonna, A. Defining the Food Truck Phenomenon in Italy: A Feasible Explanation; Smart Tourism; Cantino, V., Culasso, F., Racca, G., Eds.; McGraw-Hill Education: Milano, Italy, 2018; pp. 365–385. [Google Scholar]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y. Creare Modelli di Business; FAG: Milano, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

| International Hamburger Foodservice (IHF) | Local Hamburger Foodservice (LHF) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| McDonald’s | Burger King | M** Bun | L’Hamburgheria di Eataly | |

| Value propositions | Conventional and inexpensive food products, sometimes with local raw materials and ingredients. | Conventional and inexpensive food products. | Local ingredients, tradition, territory, supply chain, production method, and sustainability. | Local ingredients, tradition, territory, supply chain, production method, and sustainability. |

| Key resources | Self-ordering by the customer through a touchscreen, high technology innovation. | Some self-ordering by the customer through a touchscreen (only one restaurant). | Waste management, strong link to territory (local raw materials). | Waste management, link to territory (national and local raw materials). |

| Key activities | High-quality offering. Periodic menu alternatives linked to territory. | High-quality offering. | Diversified gastronomic offering, high quality, niche products, and traditional recipes | Diversified gastronomic offering, high-quality and niche products. |

| Key partners | National and international suppliers. | National and international suppliers. | Local suppliers. | Local and national suppliers. |

| Customer segments | Teenagers, families, and tourists demanding inexpensive fast food, table service, a waiting time of 2 to 6 min, and a menu price range of €4.90 to €8.90. | Teenagers, families, and tourists demanding inexpensive fast food, no table service, a waiting time of 8 min max. from payment, and a menu price range of €3.99 to €10.00. | Age group from 25 up and a few families. Customers who are willing to wait longer. | Age group from 25 up and a few families. Customers who are willing to wait longer. |

| Customer relationships | Fast and inexpensive. Innovative services. | Fast and inexpensive. | Offering based on tradition and territory. | Offering based on tradition and territory. |

| Channels | Radio, TV, Internet, social media, posters. | Radio, TV, Internet, social media, posters. | Radio, Internet, social media. | Radio, Internet, social media. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bonadonna, A.; Alfiero, S.; Cane, M.; Gheribi, E. Eating Hamburgers Slowly and Sustainably: The Fast Food Market in North-West Italy. Agriculture 2019, 9, 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture9040077

Bonadonna A, Alfiero S, Cane M, Gheribi E. Eating Hamburgers Slowly and Sustainably: The Fast Food Market in North-West Italy. Agriculture. 2019; 9(4):77. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture9040077

Chicago/Turabian StyleBonadonna, Alessandro, Simona Alfiero, Massimo Cane, and Edyta Gheribi. 2019. "Eating Hamburgers Slowly and Sustainably: The Fast Food Market in North-West Italy" Agriculture 9, no. 4: 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture9040077

APA StyleBonadonna, A., Alfiero, S., Cane, M., & Gheribi, E. (2019). Eating Hamburgers Slowly and Sustainably: The Fast Food Market in North-West Italy. Agriculture, 9(4), 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture9040077