1. Introduction

As an important cash crop and the core raw material of the textile industry, cotton occupies an important position in our country’s national economy. Topping operation is a key agronomic practice in cotton cultivation. Under certain conditions, excessive apical growth may lead to continuous differentiation of new branches and leaves, which hinders large-scale mechanized harvesting. Cotton topping technology can effectively regulate excessive apical growth, suppress apical dominance, and promote a more balanced allocation of nutrients, thereby increasing yield, enhancing boll weight and boll number, and improving overall cotton quality [

1]. However, in practical production, traditional manual topping methods suffer from several limitations, including high labor intensity, low operational efficiency, high labor costs, and a relatively high missed-hitting rate. Especially under large-scale cotton field conditions, manual topping often requires the involvement of a considerable number of operators performing repetitive tasks over extended periods, which leads to increased labor input and production costs per unit area. In addition, the stability and accuracy of topping operations are strongly influenced by operators’ experience levels and fatigue, easily resulting in inconsistent operation quality and consequently exerting adverse effects on crop uniformity and potential yield. During peak topping periods, operators are also exposed to complex field environments such as high temperatures, intense solar radiation, and pest infestations, which further reduce operational efficiency [

2]. In order to solve the above problems, mechanized topping of cotton is an effective alternative to manual topping, and the introduction of image recognition and intelligent control methods can achieve accurate identification and profiling of the top buds of cotton plants, which significantly improves the automation level of the operation [

3]. Therefore, the research on cotton apical bud detection methods for complex farmland environments has important practical significance and application value for promoting the intelligence of topping operations, improving production efficiency and reducing agricultural costs.

In recent years, deep learning technology, particularly object detection algorithms, has achieved remarkable progress across multiple application domains, including computer vision [

4], autonomous systems [

5], and intelligent agriculture [

6]. The current mainstream deep learning-based object detection algorithms can be divided into two categories: two-stage detection algorithms and one-stage detection algorithms. The two-stage detection algorithm first generates candidate regions and then classifies them. This type of algorithm has significant advantages in detection accuracy, but due to its high computational complexity and high demand for hardware resources, it is not suitable for real-time applications or resource-limited device environments, and the representative algorithms include R-CNN [

7] and Faster R-CNN [

8]. In contrast, single-stage detection algorithms do not need to generate candidate regions and directly complete target regression and category prediction from the input image, which can achieve efficient and real-time target detection capabilities by simplifying and optimizing the detection process, so they are widely used in scenarios that require rapid detection, such as YOLO [

9] and SSD [

10]. At present, extensive research has been conducted on cotton apical bud detection, with increasing emphasis on methodological refinement and adaptation to practical application requirements. In the early stage of automatic cotton apical bud detection, research primarily focused on adapting general-purpose object detection frameworks to agricultural application scenarios. For example, Han Changjie et al. [

11] and Liu Haitao et al. [

12], respectively, employed YOLOv3- and YOLOv4-based models, achieving baseline improvements in detection accuracy and inference speed through framework adaptation and anchor box optimization. As research advanced, improving detection accuracy gradually became the primary objective. By introducing feature fusion strategies, attention mechanisms, and improved loss functions to optimize internal network structures, the capability of models to represent discriminative features of cotton apical buds under complex field conditions was enhanced [

13,

14]. In addition, integrating multi-modal sensory information or adopting complex two-stage detection frameworks can, to a certain extent, improve detection robustness under dynamic field operations and severe occlusion conditions [

15,

16]. However, combining segmentation and detection tasks to enhance fine-grained feature representation of apical buds [

17] is often accompanied by increased network complexity, leading to significantly higher model parameter counts and computational overhead. To balance detection accuracy and computational efficiency, lightweight network design and structural optimization strategies have gradually attracted attention, including YOLO-based improved models employing lightweight backbone networks and redesigned neck structures [

18,

19]. Although these approaches reduce computational redundancy to some extent, achieving stable real-time performance under embedded deployment conditions remains challenging in practical mechanized cotton topping operations, where on-board or edge devices typically suffer from limited computing and memory resources.

The aforementioned studies fully demonstrate that significant progress has been made in the field of cotton apical bud detection in terms of accuracy improvement and scenario adaptability optimization. However, two core bottlenecks still remain: on the one hand, most existing lightweight solutions are implemented through approaches such as backbone network optimization and parameter compression, which are often accompanied by a decline in the model’s feature representation capability. When dealing with small apical buds, occluded apical buds, or apical buds with colors similar to the background, detection performance decreases significantly; on the other hand, the challenge of balancing real-time performance and detection accuracy has not yet been resolved. High-precision models are difficult to meet the requirements of real-time field operations, while lightweight models cannot guarantee detection reliability in complex scenarios. Therefore, how to effectively enhance the feature representation capability while maintaining the lightweight characteristics of the model has become a key issue to be urgently addressed in the current field of cotton apical bud detection.

To address the above challenges, this study proposes a lightweight cotton apical bud detection model, termed YOLO-SEW, designed for complex field environments. The model introduces the SCConv module into the backbone network to reconstruct spatial features and strengthen effective feature representation, thereby improving feature utilization efficiency under channel compression. In addition, the EMA module is incorporated to enhance contextual feature extraction. Furthermore, the WIoU loss function is adopted to accelerate model convergence during training. Unlike lightweight optimization methods that directly reduce network width or prune channels, YOLO-SEW prioritizes feature reconstruction and enhancement before model compression, aiming to improve the efficiency of unit feature representation. Based on this foundation, channel-level structural simplification is further applied. This strategy enables YOLO-SEW to achieve model lightweighting while maintaining high detection accuracy, thereby improving detection efficiency in mechanized cotton topping operations, reducing operational losses while ensuring cotton quality, and ultimately promoting the sustainable and intelligent development of cotton production.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Image Acquisition

The experimental data for this study were collected in July 2024 from a standardized cotton field in the 143rd Regiment of the 8th Division, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. A Canon 90D digital camera was used for data collection, with an image resolution of 3024 × 4032 pixels and images saved in JPG format.

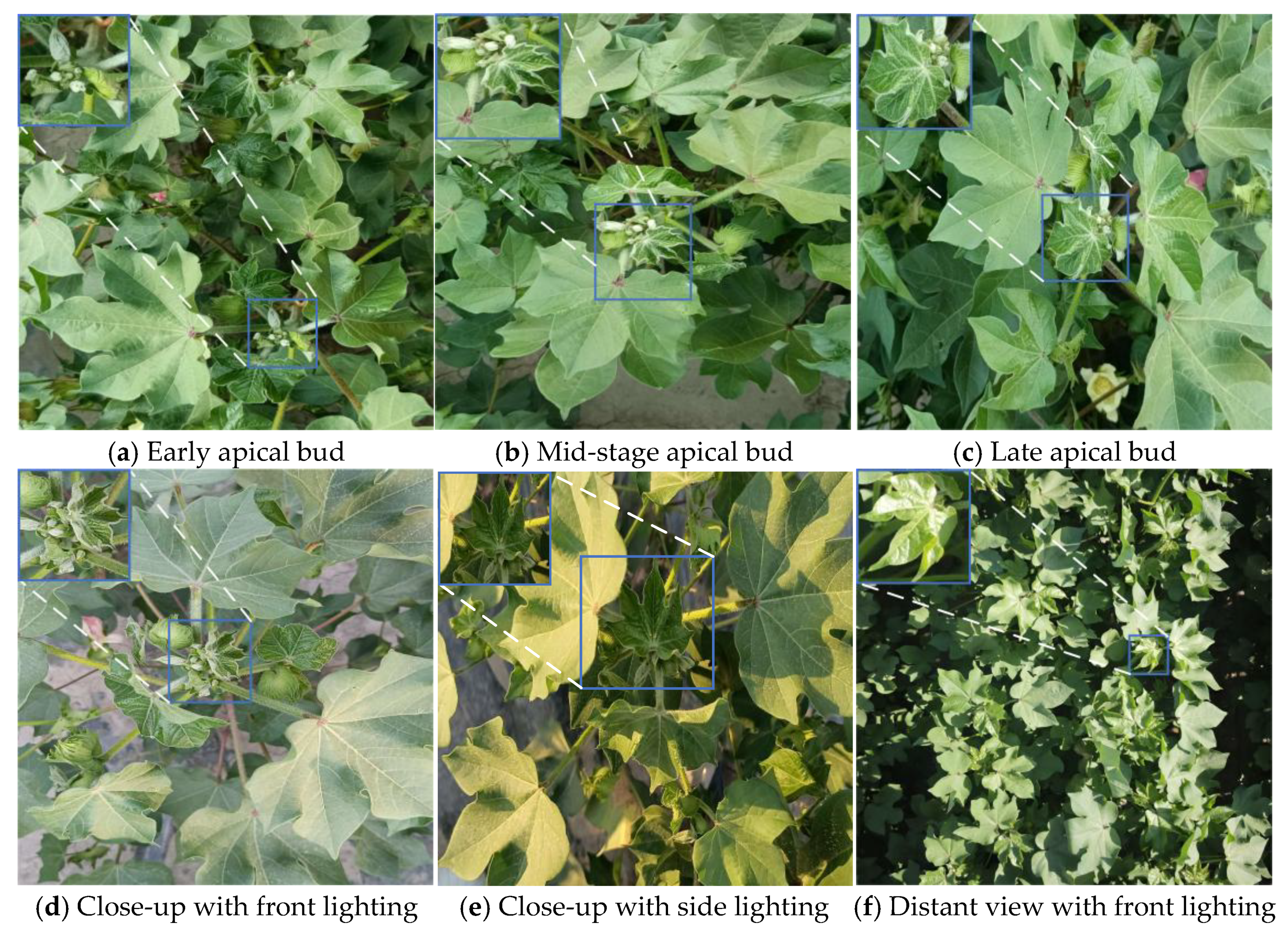

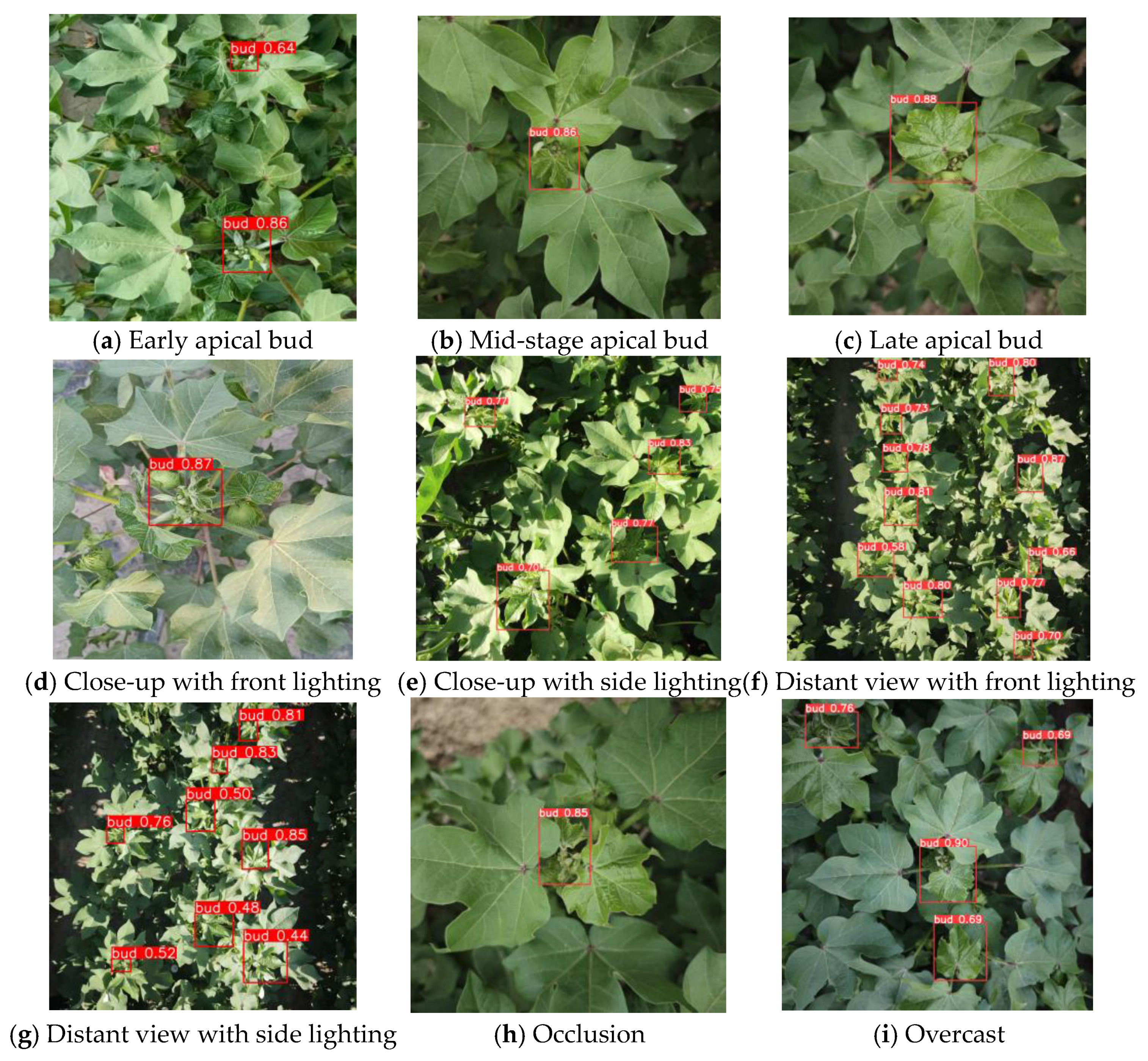

To accurately capture the growth and morphological characteristics of cotton apical buds, data collection was conducted concurrently with the manual topping period of cotton and lasted for 7 consecutive days, fully covering the three developmental stages (early, middle, and late) of apical buds: Early-stage apical buds were small in size with light green young leaves; middle-stage apical buds had slightly expanded leaves, with the color deepening to dark green; late-stage apical buds showed partial separation between leaves and buds. Image capture took place daily from 10:00 to 20:00, using a top-down vertical shooting angle. This not only ensured consistency in the shooting angle but also aligned with the practical operational requirements of mechanical topping. Although the above data acquisition strategy provides a consistent experimental setting, the dataset being collected from a single geographical region may impose certain constraints on the generalizability of the results. Without multi-region data, the model may have limited exposure to diverse environmental variations, which could affect its detection performance when deployed in different regions or under alternative cultivation conditions.

To enhance dataset diversity, multiple variable conditions were systematically incorporated during data collection: shooting height was adjusted within the range of 0.2 to 0.8 m, with two observation scales covered—close-range (1 to 5 targets) and long-range (8 to 10 targets); lighting conditions were classified into front lighting and side lighting based on natural sunlight: for front lighting, the sunlight direction was arranged to be parallel and coincident with the camera’s shooting line of sight, such that uniform illumination was created on the cotton apical bud surface and shadow interference caused by leaf overlap or bud protrusion was mitigated; for side lighting, the sunlight direction was set to be perpendicular to the shooting line of sight at a 90° angle, and directional shadows were formed in leaf folds and gaps between buds and leaves by means of lateral light irradiation. Weather conditions included both clear and overcast skies, and samples were collected from scenes with less than 30% occlusion as well as fully unobstructed scenes. An example of a cotton apical bud image is shown in

Figure 1.

2.2. Dataset Construction

In this study, a total of 2461 original images of cotton terminal buds were collected. To ensure data quality, three categories of non-compliant images were specifically excluded during the screening phase: first, images with severe blurring or color distortion; second, images with highly redundant content due to excessively similar shooting angles and distances; third, images where more than 30% of the target terminal bud area was obscured by leaves, shadows, or other objects. After screening, 2082 high-quality images were ultimately retained for subsequent research.

To construct a reliable experimental dataset, the 2082 high-quality images were first randomly divided into a training set, validation set, and test set in an approximate ratio of 8:1:1. To enhance the model’s generalization ability, data augmentation techniques, including translation, rotation, flipping, brightness adjustment, and Gaussian noise addition, were further applied to expand the training set. The final dataset comprises 3328 images in the training set, 416 in the validation set, and 416 in the test set, totaling 4160 images.

2.3. Improved Methods for Lightweight Cotton Apical Bud Detection

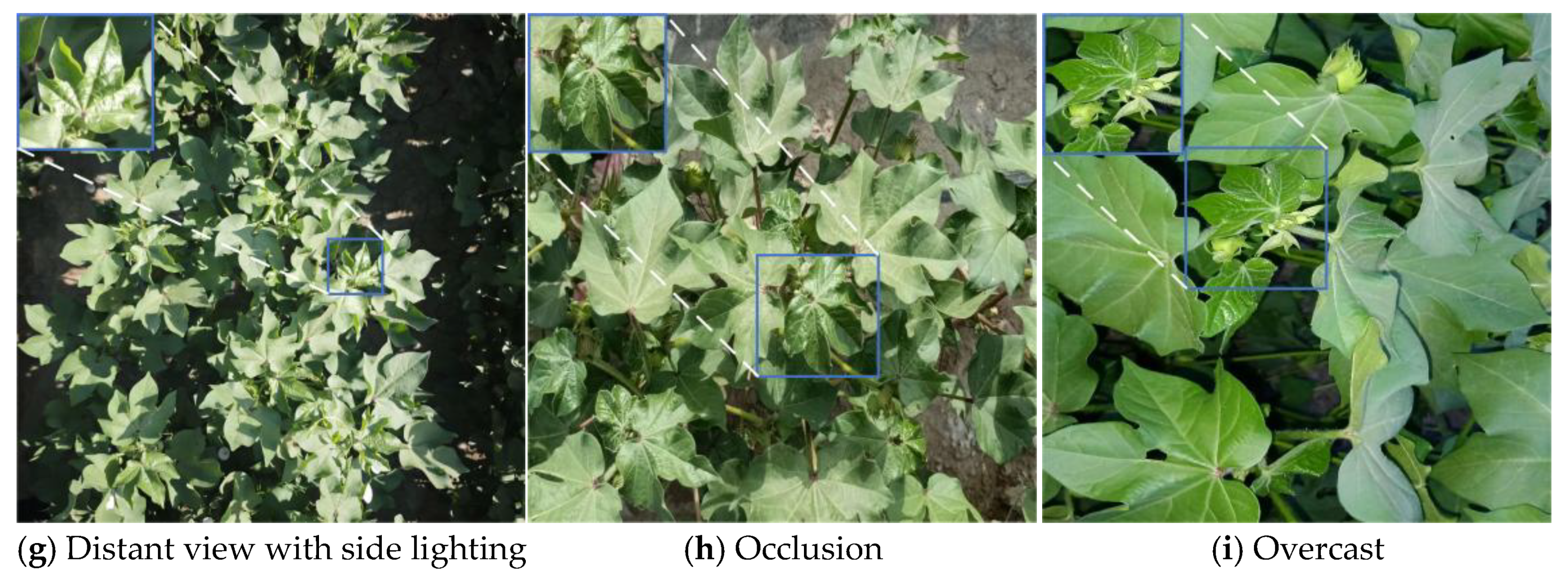

2.3.1. YOLO-SEW

In the challenging context of cotton fields, where complex backgrounds, frequent occlusion of apical buds by leaves, and significant variations in imaging conditions under different weather and lighting patterns often lead to increasingly complex algorithm architectures—resulting in high computational costs and parameter redundancy—this study proposes a lightweight YOLO-SEW algorithm to facilitate field deployment. The proposed method incorporates three key optimizations: (1) To mitigate spatial and channel redundancy in the convolutional neural network (CNN), a Spatial and Channel Reconstruction Convolution (SCConv) module is embedded into the C2f module within the backbone, thereby reducing computational complexity while improving feature representation; (2) An Efficient Multi-Scale Attention (EMA) mechanism is introduced in the neck to preserve critical channel information more effectively, capturing pixel-wise contextual interactions across dimensions and enhancing multi-scale feature fusion and expressiveness; (3) A dynamic non-monotonic focusing mechanism, Wise Intersection over Union (WIOU), is adopted to evaluate overlaps between detection boxes and ground truth more accurately. Compared to conventional IOU, WIOU offers superior performance in detecting small and densely clustered objects, significantly improving the algorithm’s generalization capability and overall performance. The architecture of the YOLO-SEW algorithm is depicted in

Figure 2.

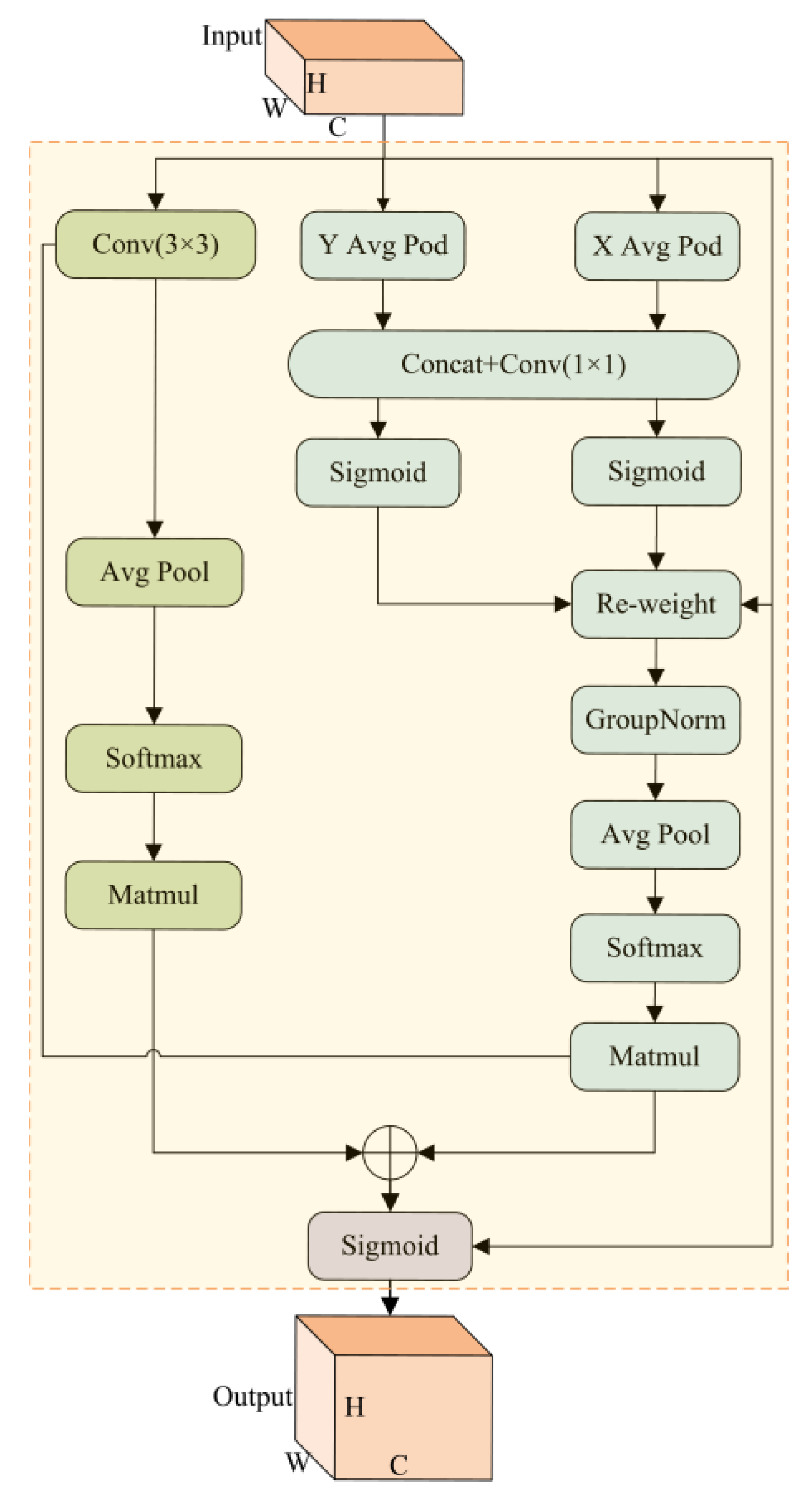

2.3.2. SCConv Module

To maintain detection accuracy while reducing model complexity, this study introduces the SCConv module into the C2f module of the backbone network, constructing a lightweight network structure termed C2f_SCConv. Existing lightweight convolutional methods, such as GhostConv [

20] and depthwise separable convolution [

21], can theoretically reduce model parameter size and computational cost (FLOPs). However, these methods primarily focus on structural simplification and do not adequately consider feature reconstruction under channel compression. In particular, depthwise separable convolution exhibits low arithmetic intensity—defined as the ratio of FLOPs to memory access—which limits effective utilization of hardware parallelism on embedded platforms. As a result, the practical acceleration achieved during deployment is often lower than theoretical expectations. In contrast, the SCConv module explicitly reconstructs features along both spatial and channel dimensions, performing convolution operations only on essential information, which effectively reduces model complexity and computational overhead [

22]. Furthermore, SCConv enhances the expressive capacity of convolutional kernels through learnable scaling factors that dynamically adapt to input data. This design strengthens the feature extraction capability of the convolutional neural network, enabling the model to suppress background interference and focus more effectively on the discriminative characteristics of cotton apical buds.

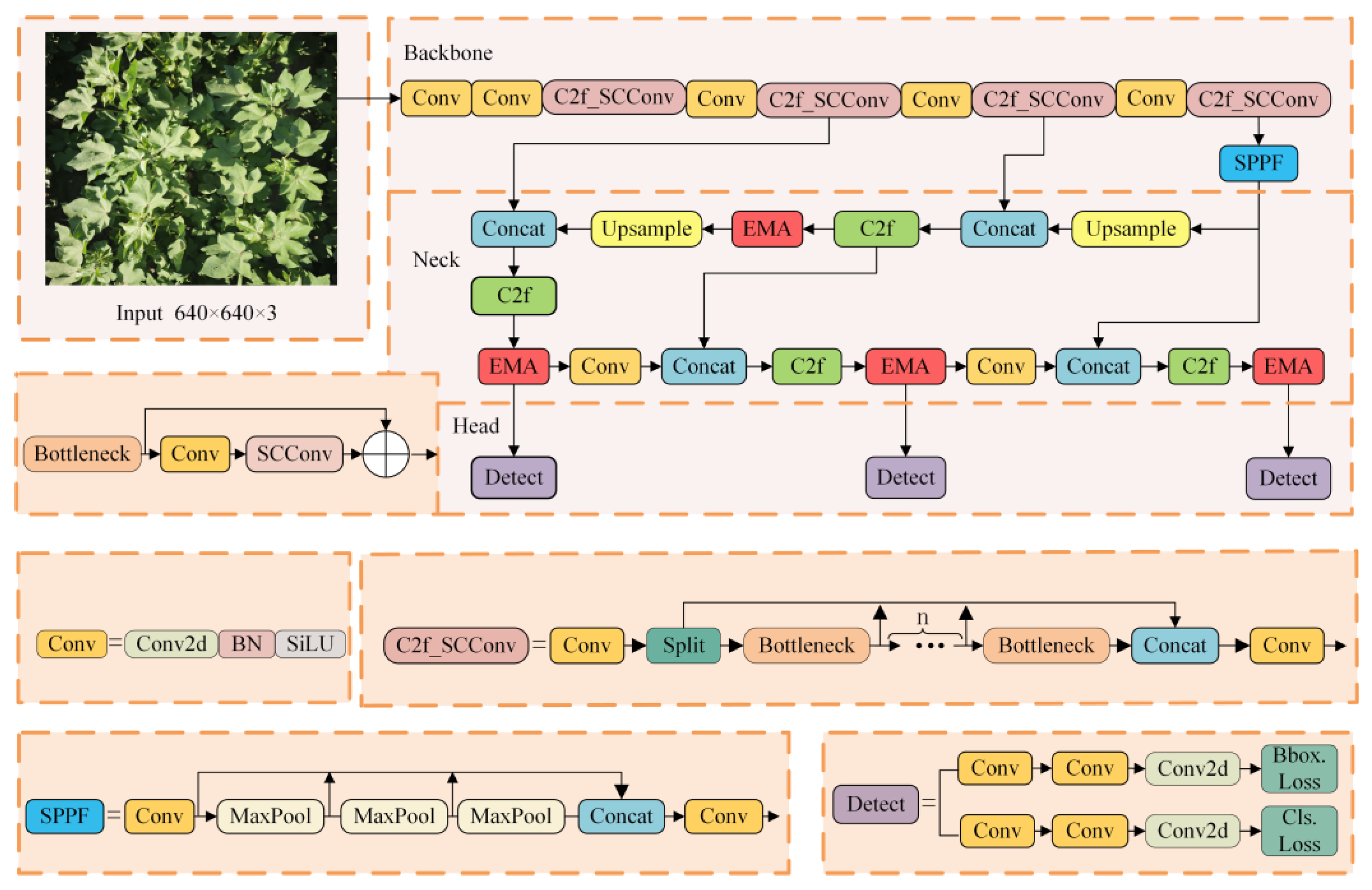

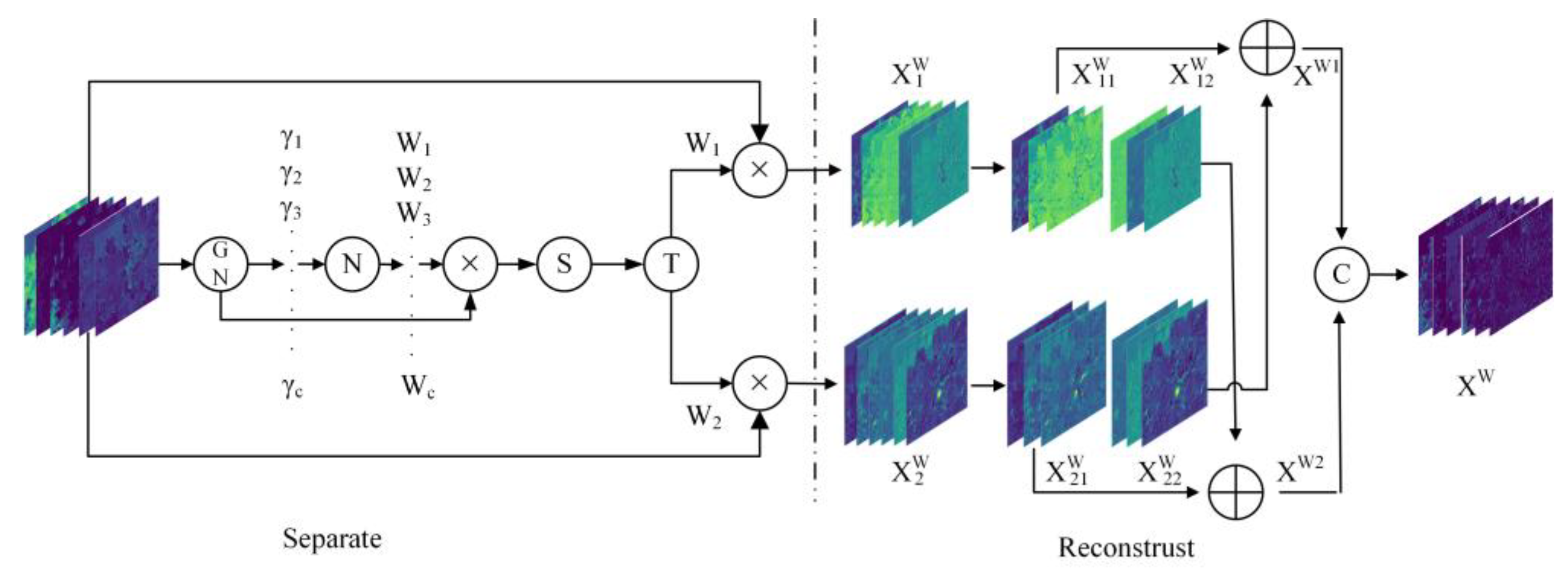

The SCConv consists of two main units: the Spatial Reconstruction Unit (SRU) and the Channel Reconstruction Unit (CRU), arranged sequentially. The input feature X first passes through the SRU, yielding a spatially refined feature

. It then undergoes processing by the CRU, which refines the channel information, ultimately producing the output feature Y. The detailed structure is illustrated in

Figure 3.

The Spatial Reconstruction Unit (SRU) employs a “split–reconstruct” approach to optimize features. The splitting operation aims to separate highly informative features from less informative ones, thereby enhancing the expressiveness of spatial content. Using scaling factors from Group Normalization, the information content across different feature maps is evaluated. The reconstruction operation then combines the more informative features with the less informative ones through additive fusion, producing features that are richer in information and more efficient in spatial utilization [

23]. The specific procedure involves cross-reconstruction, wherein the two types of weighted features are merged to obtain

and

, which is then concatenated to form the spatially refined feature map

. Through this SRU process, information-rich features are emphasized while redundancy along the spatial dimension is reduced. The entire operation can be expressed as follows:

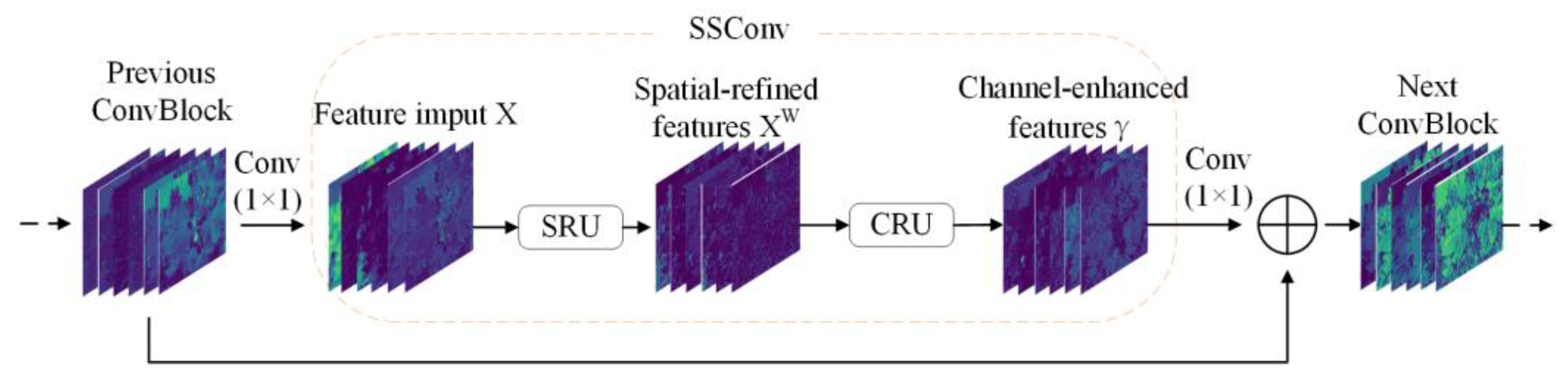

The channel reconstruction unit (CRU) adopts the method of “split-convert-converg” for channel optimization. The splitting operation divides the input spatially refined features

into two parts: one part is αC for the number of channels, and the other is (1-α)C, where α is the hyperparameter. Subsequently, a 1 × 1 convolutional kernel is used to compress these two sets of features, producing

and

respectively. In the transformation operation, as

the input of “rich feature extraction”, group convolution (GWC) and point-by-point convolution (PWC) are performed in turn, and then the two are added together to obtain the output. As a supplementary feature, a point-by-point convolution (PWC) is performed, and the result is obtained by combining it with the original input, yielding

. Fusion operations use a simplified SKNet approach to adaptive fusion,

and

are adaptively fused. Firstly, global average pooling is applied to

and

, combining global spatial information and channel statistics to yield the pooled features

and

. Then, the feature weight vector sum is calculated by Softmax. Finally, these weight vectors are used to adaptively fuse the features to generate the output Y after channel refinement. Its structure is shown in

Figure 5.

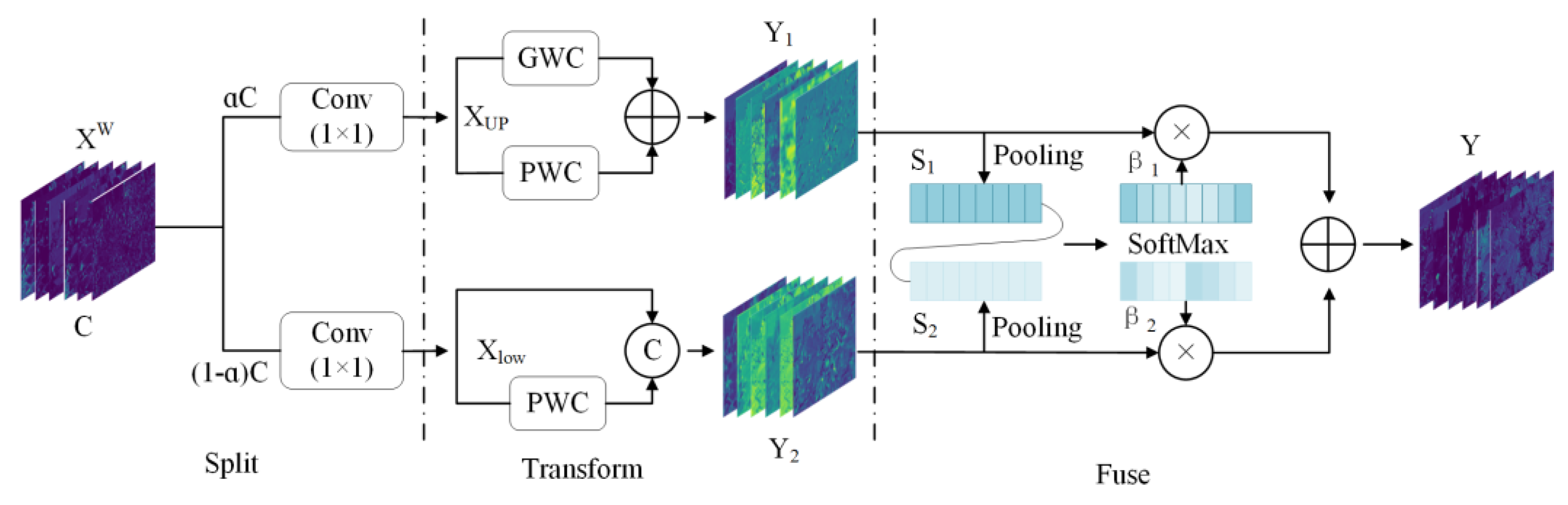

2.3.3. EMA Mechanism

To address the similarity between cotton apical buds and leaves, the EMA (Efficient Multi-scale Attention) [

24] mechanism has been introduced into the neck network of YOLOv8. This attention mechanism simultaneously captures channel and spatial information while modeling pixel-level relationships through cross-dimensional interaction. It enables the model to focus on apical bud features while integrating contextual information from surrounding leaves and stems. More importantly, the EMA mechanism achieves the above functionality with almost no additional computational burden or increase in parameter size. It efficiently filters key image information, ultimately ensuring accurate identification of cotton apical buds even in complex backgrounds.

The architecture of the EMA mechanism is depicted in

Figure 6. For an input feature map

, EMA partitions it into G groups of sub-features along the channel dimension, denoted as

, where each

. The mechanism leverages the extensive receptive fields of neurons to capture multi-scale spatial information and extracts attention weights for the grouped features through three parallel pathways: two employing 1 × 1 convolutions, whereas the third utilizes a 3 × 3 convolution to capture local multi-scale features. In the 1 × 1 pathway, one-dimensional global average pooling is applied along the spatial dimensions to encode features, capturing cross-channel dependencies while reducing computational load, whereas the 3 × 3 pathway employs convolutional operations to aggregate local spatial information and expand the feature space. To address the absence of a batch dimension in standard convolution operations, EMA reshapes the input feature tensor into a batch dimension and connects the encoded features of each group via shared 1 × 1 convolutions. The convolutional output is subsequently split into two vectors, with a sigmoid function applied to model a binomial distribution. To enable cross-channel feature interaction, the parallel channel attention maps from the 1 × 1 pathway are fused through multiplication, while the 3 × 3 pathway enhances local cross-channel interaction via convolution, thereby improving feature representation.

Furthermore, EMA employs two-dimensional global average pooling to encode global spatial information in the 1 × 1 path, utilizing the Softmax function to generate the first spatial attention map for capturing spatial information at different scales. The 3 × 3 path similarly adopts two-dimensional global average pooling to produce the second spatial attention map, preserving complete spatial positional information. Ultimately, each set of output features aggregates the two generated spatial attention weights, processed through a sigmoid function to obtain pixel-level global contextual dependencies.

2.3.4. Dynamic Non-Monotonous Focusing Mechanism

In practical cotton apical bud detection scenarios, frequent occlusion by surrounding leaves often leads to partial loss of apical bud feature information, thereby increasing localization uncertainty. Traditional IoU-based loss functions, such as CIoU and DIoU, typically employ monotonous penalty mechanisms, making it difficult to adaptively adjust gradient weights according to variations in target scale and degrees of occlusion. In complex field environments, small-scale or partially occluded apical buds are prone to producing noisy regression signals. Excessive penalties imposed on such low-quality samples by conventional loss functions not only introduce harmful gradients that interfere with the optimization process but also tend to amplify localization errors under occlusion conditions, ultimately limiting detection accuracy and robustness. To address these issues, this study introduces the WIoU loss function [

25], which incorporates a dynamic non-monotonous focusing mechanism to enhance convergence efficiency and localization robustness. WIoU comprises three versions: v1 employs an attention-based architecture, whereas v2 and v3 incorporate focusing mechanisms, with v3 exhibiting superior performance by simultaneously improving the learning efficacy for high-quality samples whilst mitigating the adverse effects of harmful gradients on overall performance.

The definition of the

loss function is shown in the following formula:

In the equation: represents the Intersection over Union between the predicted and ground truth bounding boxes; denotes the bounding box loss function; and (correspond to the center coordinates of the predicted and ground truth boxes, respectively; whilst and represent the width and height of the minimum enclosing rectangle formed by the predicted and ground truth boxes.

The formula for the

loss function is given by the following equation:

where

is the actual bounding box loss value;

is the dynamic sliding average; α, δ is a hyperparameter, β represents outliers. WIoU dynamically adjusts the gradient gain by calculating the outlier degree of anchor boxes, thereby providing finer control for model optimization. For anchor boxes with smaller outlier degrees (i.e., high-quality anchors), the allocated gradient gain is reduced, whereas those with larger outlier degrees (i.e., low-quality anchors) receive appropriately increased gradient gain to ensure thorough learning during training. In practical cotton field environments, owing to the complex growing conditions, apical buds are typically small in scale and are frequently subjected to severe occlusion by surrounding leaves. By adaptively regulating gradient gains, WIoU effectively alleviates regression instability caused by occlusion or small target size, while simultaneously suppressing harmful gradients introduced by a large number of low-quality predictions. This non-monotonic gradient modulation strategy achieves a favorable balance between training stability and localization accuracy, thereby significantly improving the overall detection performance of cotton apical bud detection tasks.

3. Experiment and Analysis

3.1. Test Environment and Evaluation Indicators

All experiments in this study were conducted in a consistent environment using the same dataset. During the algorithm deployment phase, testing was performed on the NVIDIA Jetson Orin NX module, with specific experimental environment configurations detailed in

Table 1.

The key parameter settings for the training process are as follows: the input image size of the network was fixed at 640 × 640 pixels, the batch size was set to 16, the total number of training epochs was 300, and the initial learning rate was specified as 0.01. To effectively mitigate model overfitting, an early stopping mechanism was introduced—training would terminate automatically if the validation loss showed no significant improvement for 10 consecutive epochs. The Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) optimizer was employed, with the weight decay coefficient set to 0.0005 and the learning rate momentum adjusted to 0.937, aiming to balance the stability and convergence efficiency of model training.

The experimental results employed Precision, Recall, and AP as evaluation metrics, with the computational formulae for these metrics being as follows:

TP refers to the number of samples that are actually positive and correctly predicted as positive by the model; FP denotes the number of samples that are actually negative but incorrectly predicted as positive by the model; FN represents the number of samples that are actually positive yet incorrectly predicted as negative by the model. AP characterizes the average performance of a specific class across different recall levels, and its value is equal to the area under the Precision-Recall (P-R) curve. mAP is the average of the AP values for all target classes. In this study, the number of target classes is n = 1 (i.e., cotton apical buds), so the average precision is reported as AP, with AP50 specifically adopted, where the IoU threshold is set to 0.5.

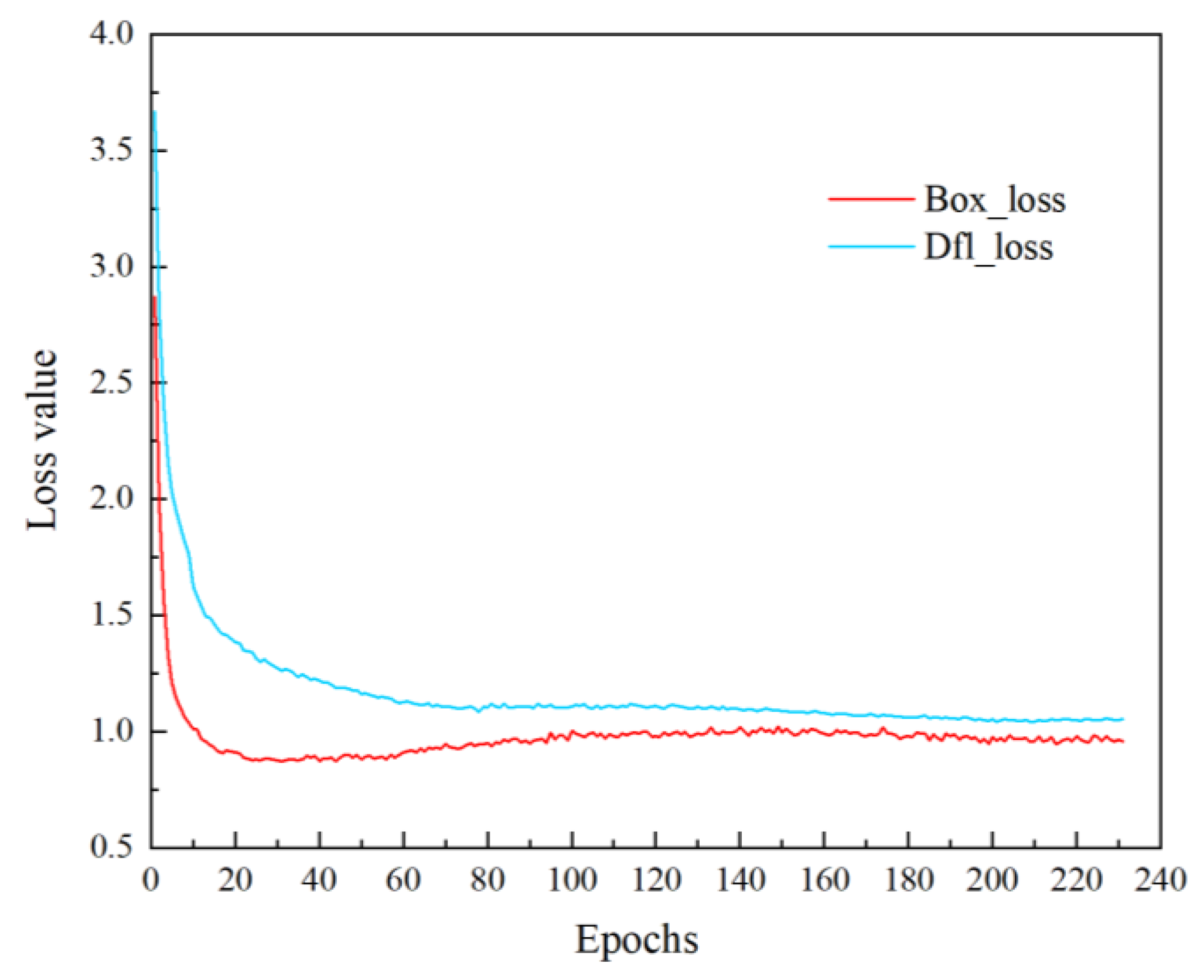

3.2. Model Training

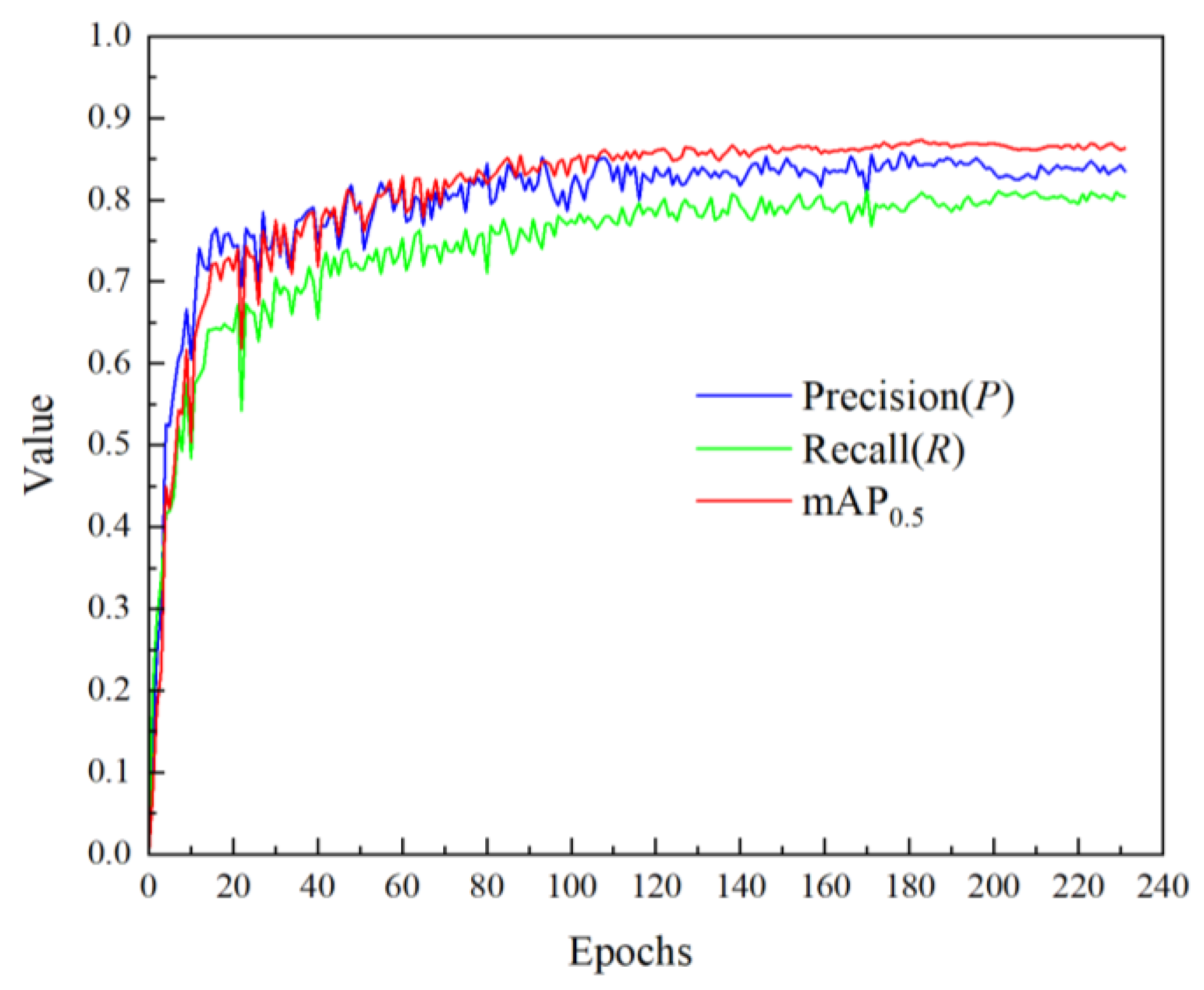

The training was set to 300 epochs. During the initial phase, both the Box loss and Dfl loss decreased rapidly, with the Box loss reaching its lowest value at approximately 25 iterations before exhibiting a slight increase. Concurrently, the Precision, Recall, and mAP0.5 values demonstrated substantial growth, indicating high learning efficiency and rapid loss convergence. Around 190 iterations, the Box loss, Dfl loss, Precision, Recall, and mAP0.5 values stabilized. An excessively high epoch setting was observed to cause model overfitting. When the training reached 231 epochs in the experiment, the performance failed to show significant improvement. To avoid computational resource wastage, the training was automatically terminated. The variation trends of Box loss and Dfl loss are presented in

Figure 7, whilst the progression of Precision, Recall, and mAP0.5 values is shown in

Figure 8.

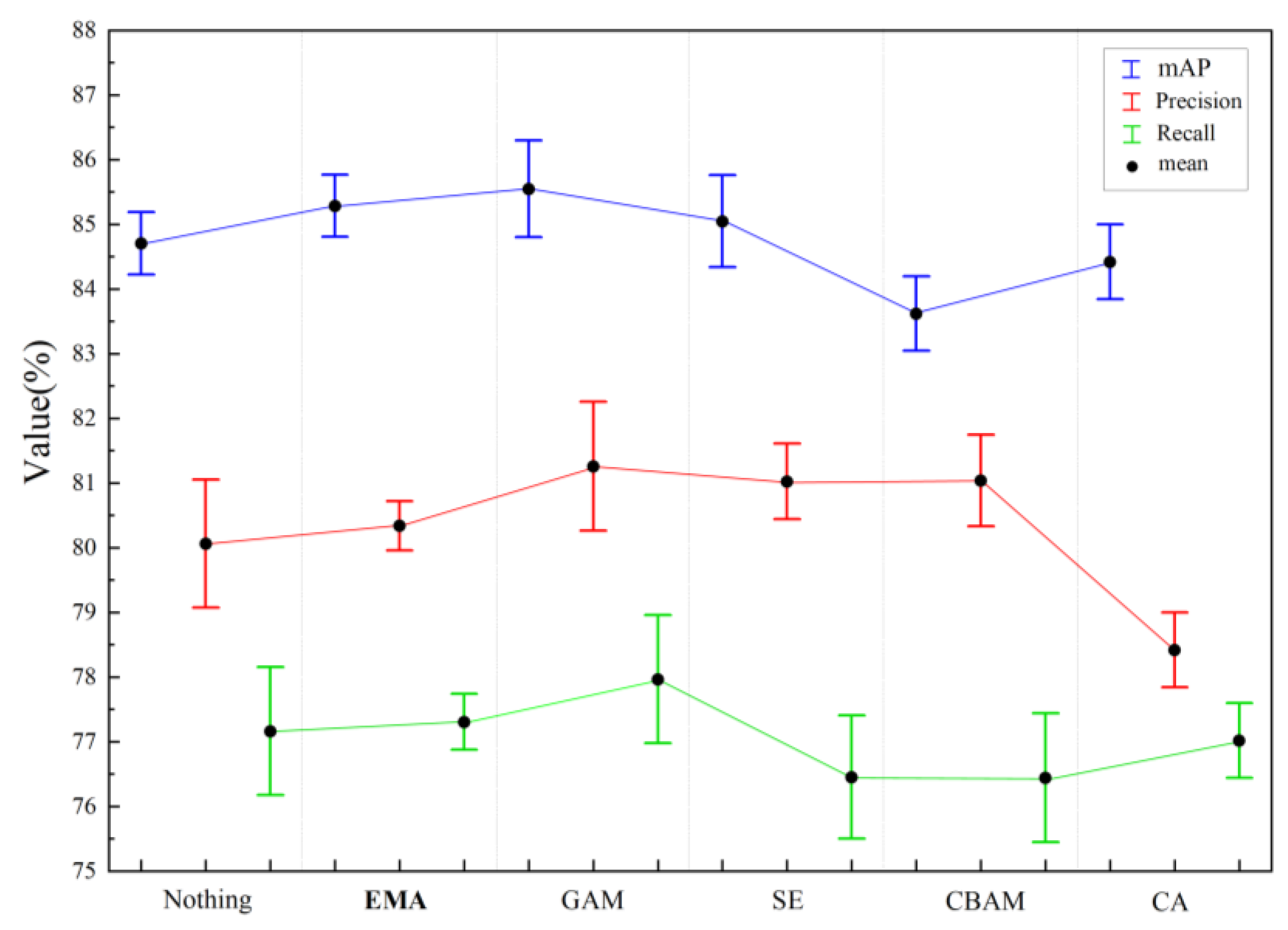

3.3. Comparison of Detection Performance of Different Attention Mechanisms

To validate the effectiveness of the EMA mechanism in lightweight cotton apical bud detection, this study conducted comparative experiments between EMA and several representative attention mechanisms, including GAM (Global Attention Mechanism) [

26], SE (Squeeze-and-Excitation) [

27], CBAM (Convolutional Block Attention Module) [

28], and CA (Coordinate Attention) [

29]. Throughout the experiments, all attention mechanism modules were deployed at precisely the same network positions as the EMA module and underwent performance evaluation using the identical test dataset. To mitigate the impact of deep learning training randomness on experimental outcomes, each model configuration underwent 100 independent training iterations to ensure result reliability. The experimental results are presented in

Table 2, while

Figure 9 illustrates the standard deviation distributions of the three metrics—mAP@0.5, Precision (P), and Recall (R)—across different attention mechanisms.

The experimental results show that the YOLOv8-EMA model achieves an mAP@0.5 of 85.3%, with an mAP@0.5:0.95 of 56.1%, representing improvements of 0.6 and 0.4 percentage points, respectively, compared to the baseline model YOLOv8. Meanwhile, YOLOv8-EMA maintains a similar parameter size, computational load, and model size to the baseline model, without introducing any additional computational overhead. This performance gain aligns with the typical optimization improvements observed in YOLO models within agricultural application scenarios. For instance, Khalili et al. [

30] incorporated the EMA mechanism into the C2f module and achieved a 0.6% mAP improvement on the small target subset of the VisDrone dataset. Meanwhile, Lu et al. [

31] introduced a spatial attention mechanism, resulting in a 0.8% increase in mAP for crop pest and disease recognition tasks. In contrast, the model with the highest mAP (85.6%), YOLOv8-GAM, has its parameter size, computational load, and model size increased to 5.6 MB, 12.9 GB, and 11.4 MB, respectively, making it difficult to meet the practical requirements for lightweight deployment. Further analysis of the performance indicator dispersions in

Figure 9 reveals that the EMA module exhibits the least fluctuation in performance metrics, with its mAP standard deviation being only 0.4%. The standard deviations of precision and recall are also low, at 0.3% and 0.4%, respectively, indicating that the model exhibits good robustness to randomness during the training process. In comparison, the performance fluctuations for the GAM and SE modules are more significant. Furthermore, the CBAM module’s mAP is even lower than the baseline model, suggesting that this module suffers from feature interference issues in the cotton apical bud detection task, thereby diminishing the model’s feature extraction effectiveness. Based on the experimental results presented in

Table 2 and

Figure 9, it can be concluded that the EMA module, while ensuring high detection accuracy, also balances lightweight characteristics and performance stability, making it the optimal choice for practical deployment in the cotton apical bud detection task.

3.4. Ablation Test

To evaluate the impact of individual modules on detection performance, an ablation study was conducted employing YOLOv8n as the baseline network. The results on the test set are presented in

Table 3.

According to the analysis results presented in

Table 3, integrating the SCConv module with the C2f structure reduces the model parameters from 3.2 MB to 1.9 MB and the computational cost from 8.0 GFLOPs to 6.1 GFLOPs, corresponding to reductions of approximately 40% and 24%, respectively, while simultaneously improving the mAP from 84.7% to 85.1%. These improvements can be primarily attributed to the synergistic effect of grouped convolutions and lightweight branches, which decouple the originally dense channel-wise computations into multiple low-correlation subspaces, thereby effectively reducing inter-channel coupling. Moreover, the adaptive feature reconstruction mechanism alleviates feature redundancy caused by consecutive convolutions in deep networks; when combined with the reduced stacking depth of modules at the P3/P4 stages, it further leads to a significant reduction in overall computational burden. The introduction of the EMA mechanism brings a 0.6 percentage point improvement in mean average precision. Furthermore, after adopting the WIoUv3 loss function, the model achieves comprehensive enhancements in precision (81.1%), recall (78.3%) and mean average precision (85.6%), strongly demonstrating its advantages in boosting the model’s fitting capability and optimizing small target detection performance.

Notably, when C2f_SCConv and EMA are applied simultaneously, the mAP decreases to 84.8%, which is lower than the performance achieved by either module alone, indicating potential functional interference in channel-wise feature modulation. This interference arises because both modules recalibrate channel features and, without coordination, may cause over-modulation that suppresses discriminative features and destabilizes gradient propagation. In contrast, when C2f_SCConv, EMA, and WIoUv3 are jointly integrated, WIoUv3 mitigates these conflicts at the optimization level by dynamically regulating gradient gains and suppressing harmful gradients, enabling simultaneous improvements of 1.2, 2.5, and 1.4 percentage points in precision, recall, and mAP, respectively, while significantly reducing model parameters, computational cost, and model size.

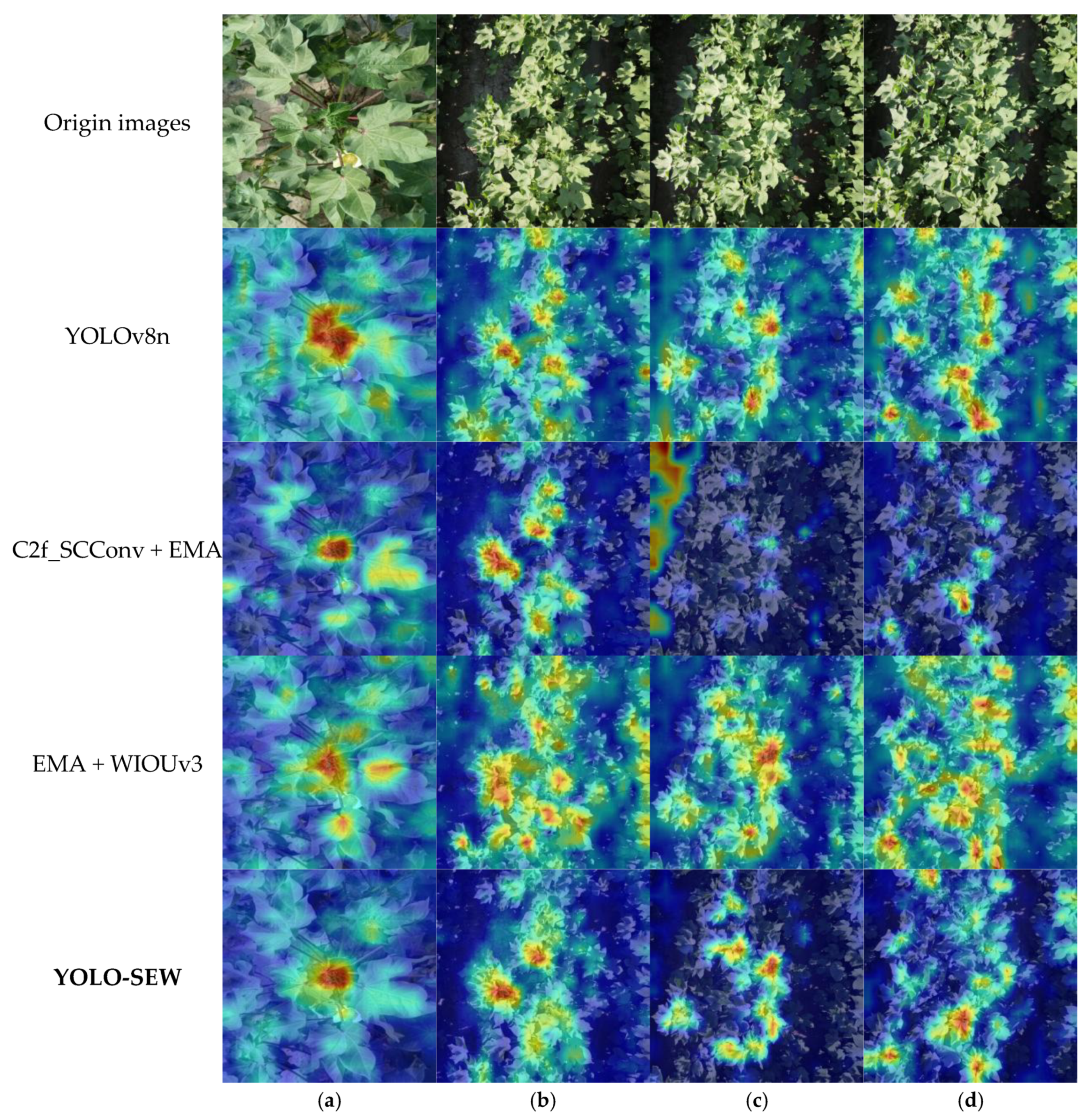

3.5. Visual Evaluation by Grad-CAM

To further analyze the interaction mechanisms between modules, this study employed Grad-CAM technology to visualize the visual attention regions of different module combinations, with the results shown in

Figure 10.

Figure 10a corresponds to a relatively simple single-target scene, while

Figure 10b–d depict complex cotton field environments characterized by higher target density, partial occlusion, and strong background interference, thereby representing typical scenarios under varying target densities and environmental complexities. The color intensity in the heatmaps reflects the degree of visual attention, with warmer colors (yellow–red) indicating stronger activation responses.

In the C2f_SCConv + EMA combination, the model exhibits a scattered activation pattern. Heatmaps reveal target regions dominated by low-intensity cyan-green activation, with marked response gaps and even complete omission of some small targets. This incoherence arises because C2f_SCConv’s channel pruning may over-eliminate fine-grained semantic cues critical to EMA, while EMA’s overemphasis on high-level semantics further neglects the low-level structural features preserved by C2f_SCConv—their conflicting priorities thus hinder the model from forming stable target representations. By contrast, the EMA + WIoUv3 pairing demonstrates a different limitation: biased focusing. Here, heatmaps show intense yellow-red activation concentrated in the central areas of large targets, which sharply contrasts with weak or absent responses at target edges and in small targets. This imbalance stems from EMA’s lack of sufficient low-level feature support, impairing its ability to construct complete contour representations. Compounding this issue, WIoUv3’s enhanced focus on localization accuracy amplifies the model’s over-concentration on core regions, ultimately leading to inadequate learning of edge features and hard samples.

In contrast to these pairwise limitations, YOLO-SEW achieves a cohesive solution, as its heatmaps display ideal continuous yellow-red activation covering nearly all targets. Its synergistic mechanism operates across three complementary levels: first, C2f_SCConv provides high-quality low-level structural anchors via feature reconstruction, addressing the foundational gap in EMA + WIoUv3; second, EMA leverages these anchors to precisely focus on semantically key regions and filter background noise, resolving the misalignment seen in C2f_SCConv + EMA; finally, WIoUv3 strengthens learning of edges and hard samples through dynamic loss weighting, counteracting the bias of the EMA + WIoUv3 pairing. This multi-level collaboration overcomes the limitations of traditional pairwise combinations and enhances overall performance.

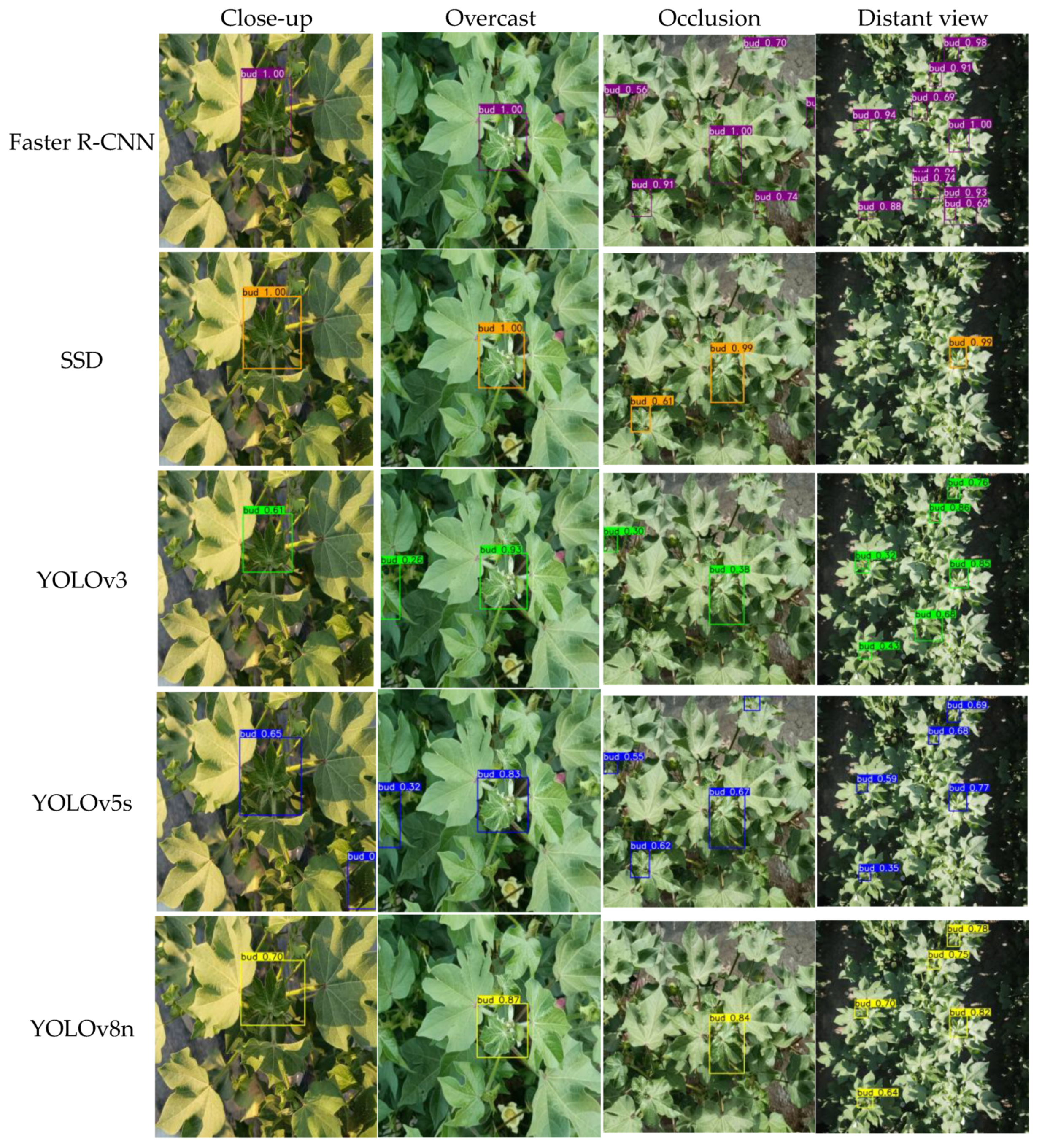

3.6. Comparative Analysis of Different Algorithms

To further validate the performance of the proposed algorithm, comparative experiments were conducted under identical conditions against Faster R-CNN [

32], SSD, YOLOv3 [

33], YOLOv5s [

34], YOLOv8n [

35], YOLOv10 [

36], YOLOv11 [

37] and YOLOv13 [

38]. The evaluation employed mAP@0.5, precision, recall, parameter count, computational complexity, and model size as metrics, with the results presented in

Table 4. Comparative analysis revealed that the YOLO-SEW algorithm achieved improvements in mAP@0.5 of 3.1%, 10%, 1.9%, 1.4%, 0.7%, 0.9% and 0.3% relative to Faster R-CNN, SSD, YOLOv5s, YOLOv8n, YOLOv10n, YOLOv11n and YOLOv13n, respectively. Additionally, the mAP@0.5:0.95 for YOLO-SEW showed consistent improvements, reflecting enhanced generalization and robustness across varying IoU thresholds. In terms of parameter count, it demonstrated reductions of 26.28 M, 12.20 M, 0.58 M, 1.30 M, 0.79 M, 0.70 M and 0.55 M compared to the aforementioned algorithms. These results indicate that the proposed approach not only enhances detection accuracy but also reduces parameter count, computational requirements, and model size, thereby achieving considerable lightweight performance.

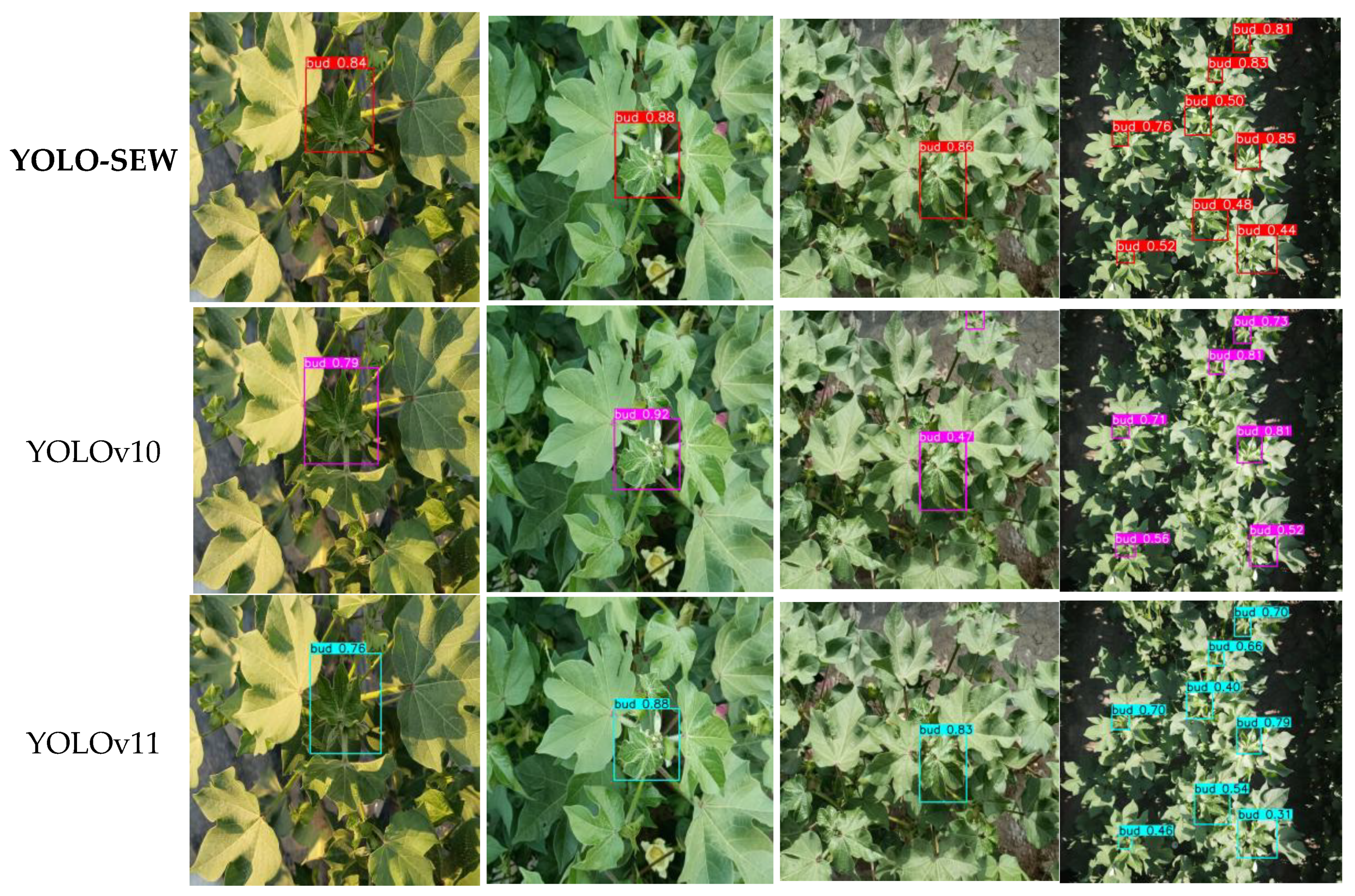

To validate the practical detection performance of various algorithms, images of apical buds with random variations in perspective, occlusion conditions and morphology were selected for testing. The detection results, presented in

Figure 11, indicate that, compared with other models, the YOLO-SEW algorithm demonstrates reliable localization performance for cotton apical buds in long-range scenarios and exhibits an improved capability to distinguish boundaries between adjacent buds. In the presence of leaf occlusion, the proposed method is able to maintain stable coverage of apical bud regions, with reduced missed and false detections, while consistently preserving a high level of detection confidence. It should be noted that the current dataset does not explicitly include meteorological variables such as temperature and air humidity. In practical agricultural settings, these environmental factors may influence cotton growth dynamics, leaf morphology, and color characteristics, which could in turn affect the visual appearance of apical buds. Under conditions involving substantial environmental variation or extreme climatic events, the absence of such information may introduce certain challenges to the generalization and robustness of the model.

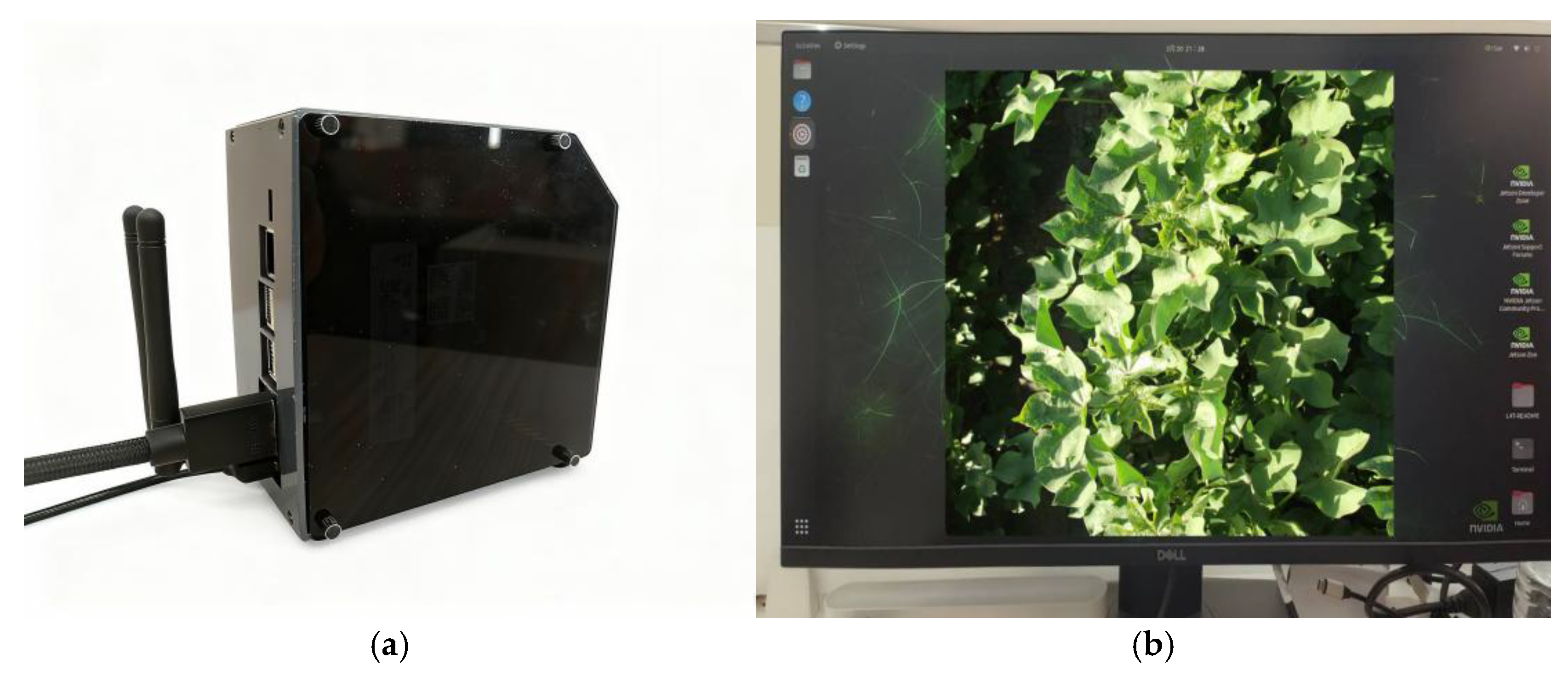

3.7. Experimental Analysis of Edge Computing Equipment Deployment

The lightweight characteristics of YOLO-SEW enable efficient deployment on low-power embedded devices without relying on high-performance computing hardware, thereby reducing equipment procurement and system maintenance costs. Meanwhile, its stable detection accuracy effectively improves overall operational efficiency and alleviates labor intensity in practical applications. To evaluate the real-time detection performance of the algorithm, this study deployed it on the NVIDIA Jetson Orin NX embedded platform. The platform is deeply integrated with the NVIDIA JetPack SDK software development kit, which stably supports real-time video stream analysis and object detection tasks. It also features a compact structure, low power consumption, and high computational throughput, meeting the stringent requirements of practical applications such as industrial robotics, which demand space efficiency and operational endurance. The platform hardware is shown in

Figure 12.

During the deployment process, TensorRT was used to accelerate the model’s inference. The .pt weight file trained on the PyTorch 1.12 framework was first converted into an intermediate .onnx file, which was subsequently utilized to build an .engine file for inference. The test results indicate that, without TensorRT acceleration, the YOLO-SEW model on the Jetson Orin NX platform achieved an inference speed of approximately 17 frames per second, which did not meet the real-time requirements for mechanized cotton topping operations. After TensorRT optimization, the model’s inference speed increased to 48 frames per second, significantly improving its real-time detection capability on the embedded platform. Under continuous inference conditions, the overall power consumption remained stable at approximately 16–18 W, with no noticeable fluctuations, and the end-to-end inference latency per frame was consistently maintained between 20 and 22 ms. In field operation scenarios, cotton topping systems are typically deployed on mobile platforms operating at low and constant speeds. Under such conditions, the visual detection system is required to process video streams in a continuous and stable manner with sufficient temporal resolution so as to ensure effective coordination between target perception and the execution mechanism. This level of performance allows detection results to be updated within a single control cycle, thereby enabling accurate identification and localization of cotton apical buds before the cutting device reaches the target position. The relatively high frame rate also provides temporal redundancy; even if individual frames are affected by motion blur or partial occlusion, the system can rely on consecutive frames to maintain stable detection, thus avoiding fluctuations in topping quality caused by perception delays. Representative detection results are shown in

Figure 13.