Comparing Cotton ET Data from a Satellite Platform, In Situ Sensor, and Soil Water Balance Method in Arizona

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

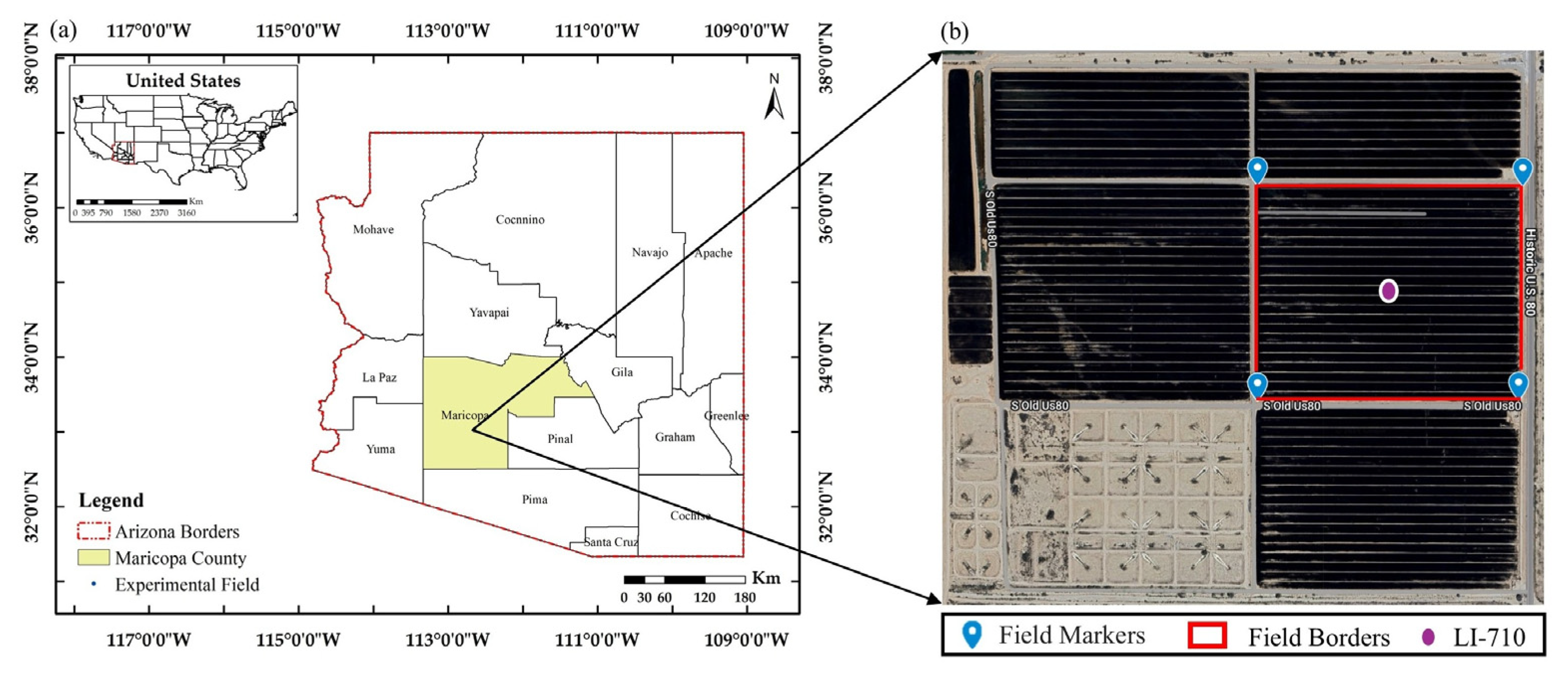

2.1. Experimental Field and Datasets

2.2. OpenET

2.2.1. Dataset Description

2.2.2. Data Acquisition

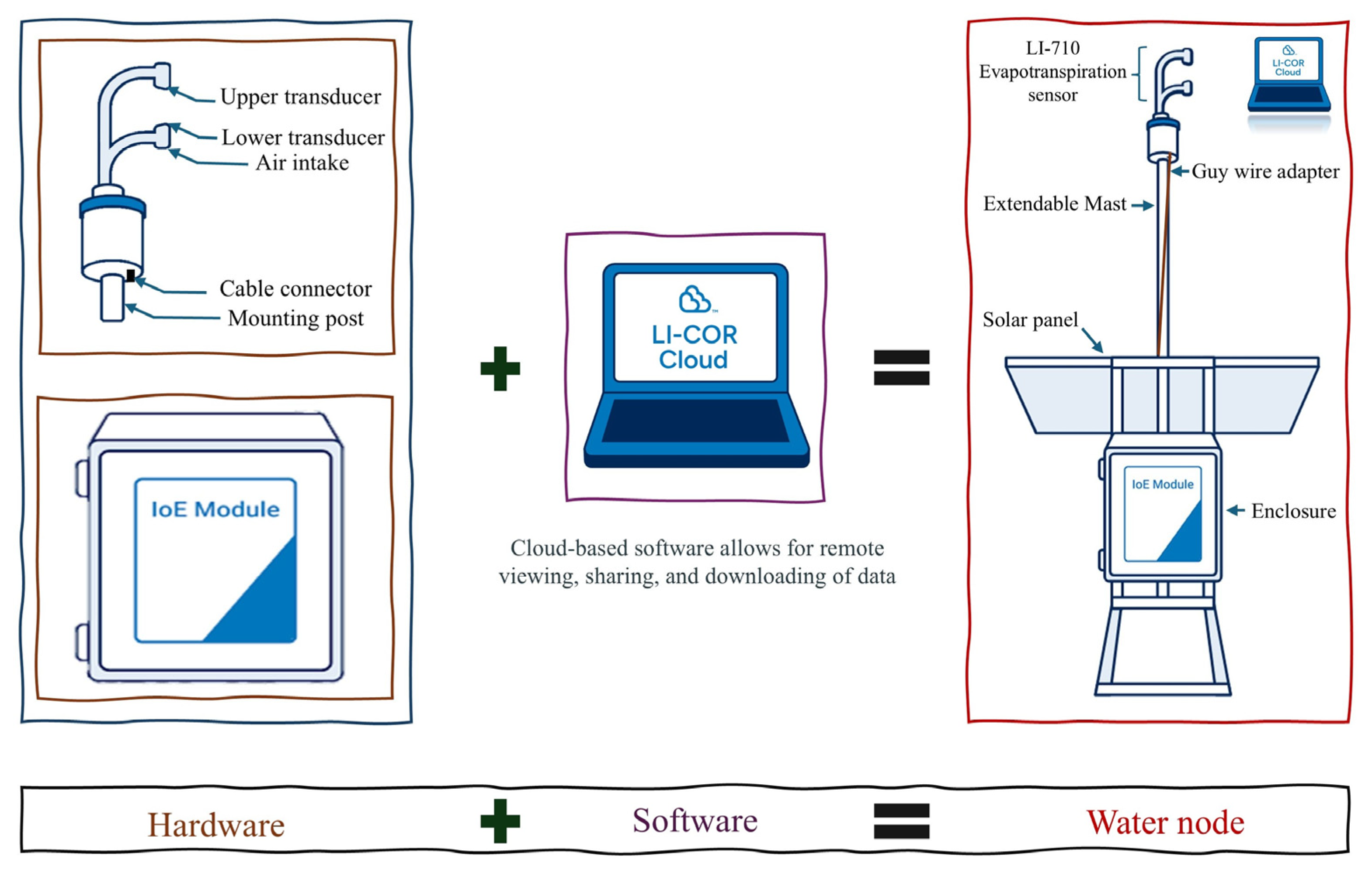

2.3. LI-710: Components and Theory of Operation

2.3.1. LI-710 Components

2.3.2. LI-710 Theory of Operation

2.4. Evaluation Metrics

3. Results and Discussion

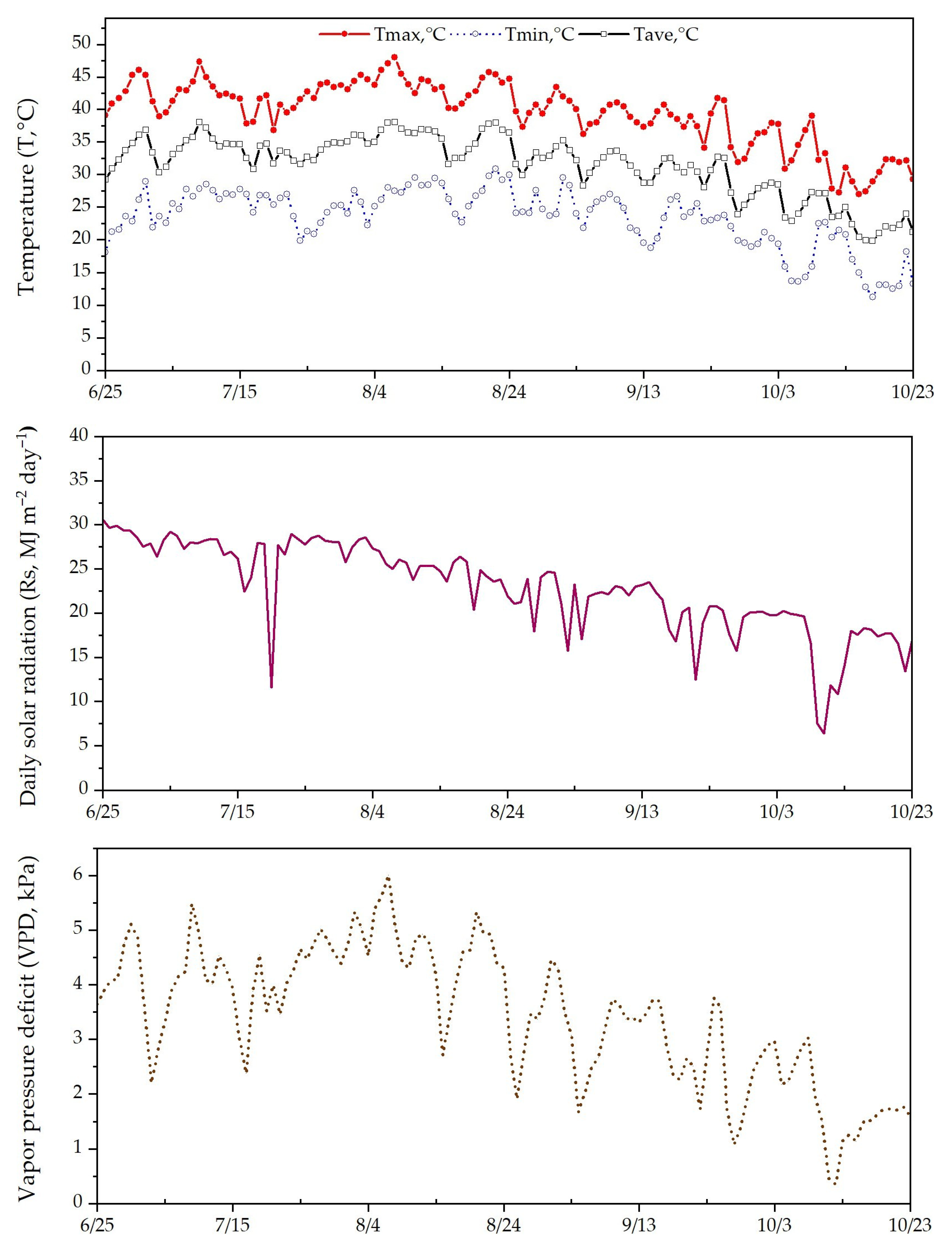

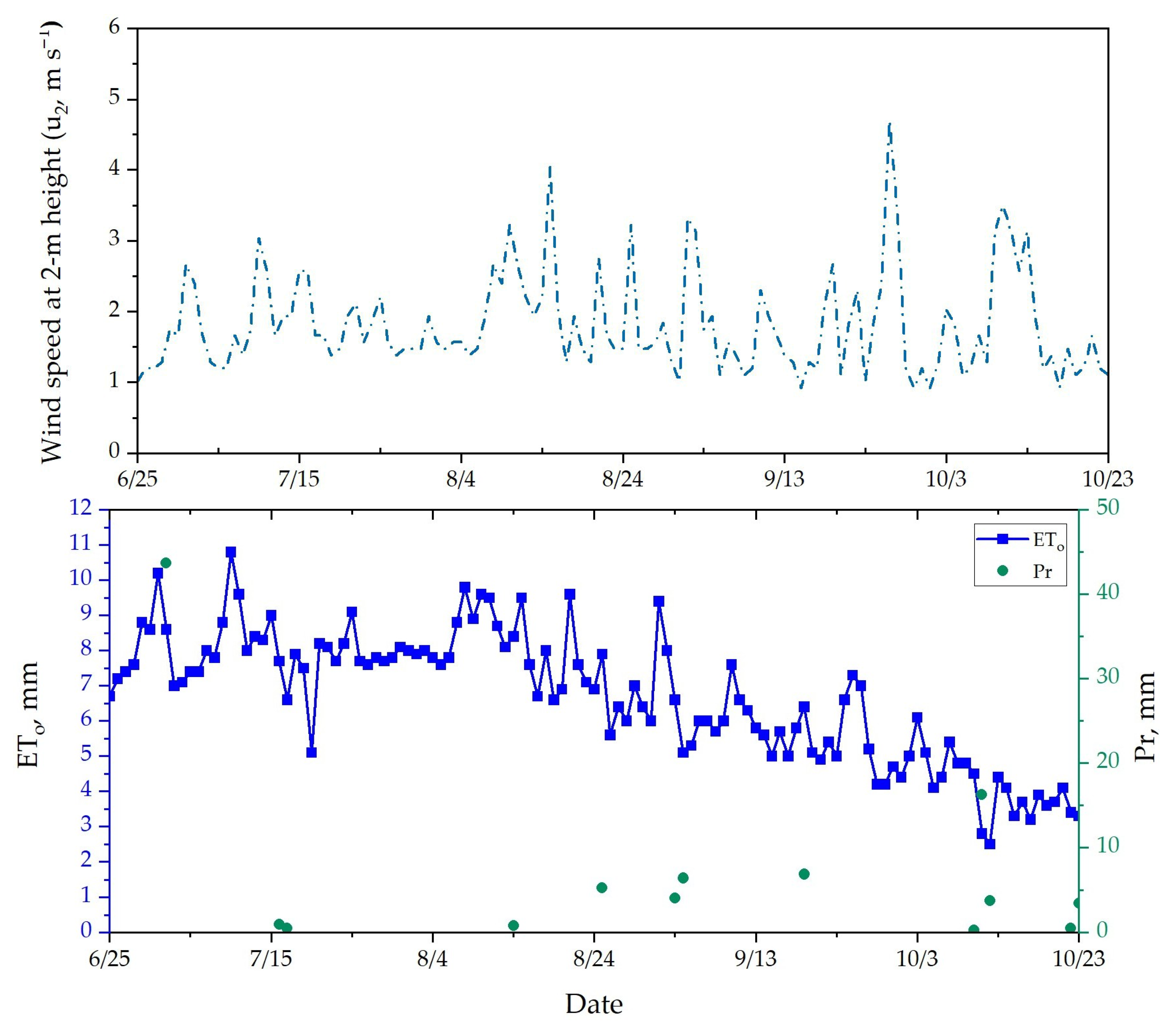

3.1. Climate Conditions

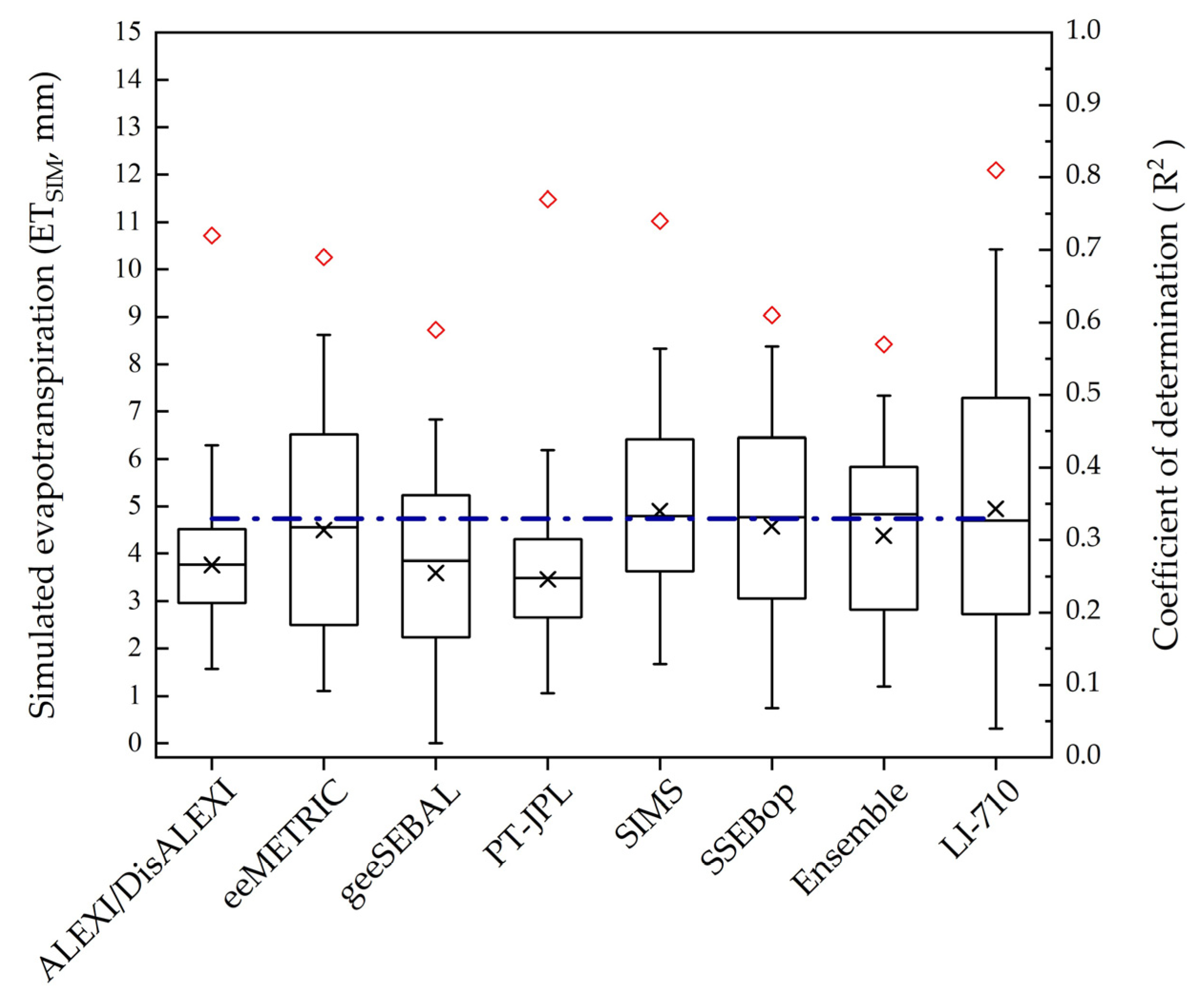

3.2. OpenET Models

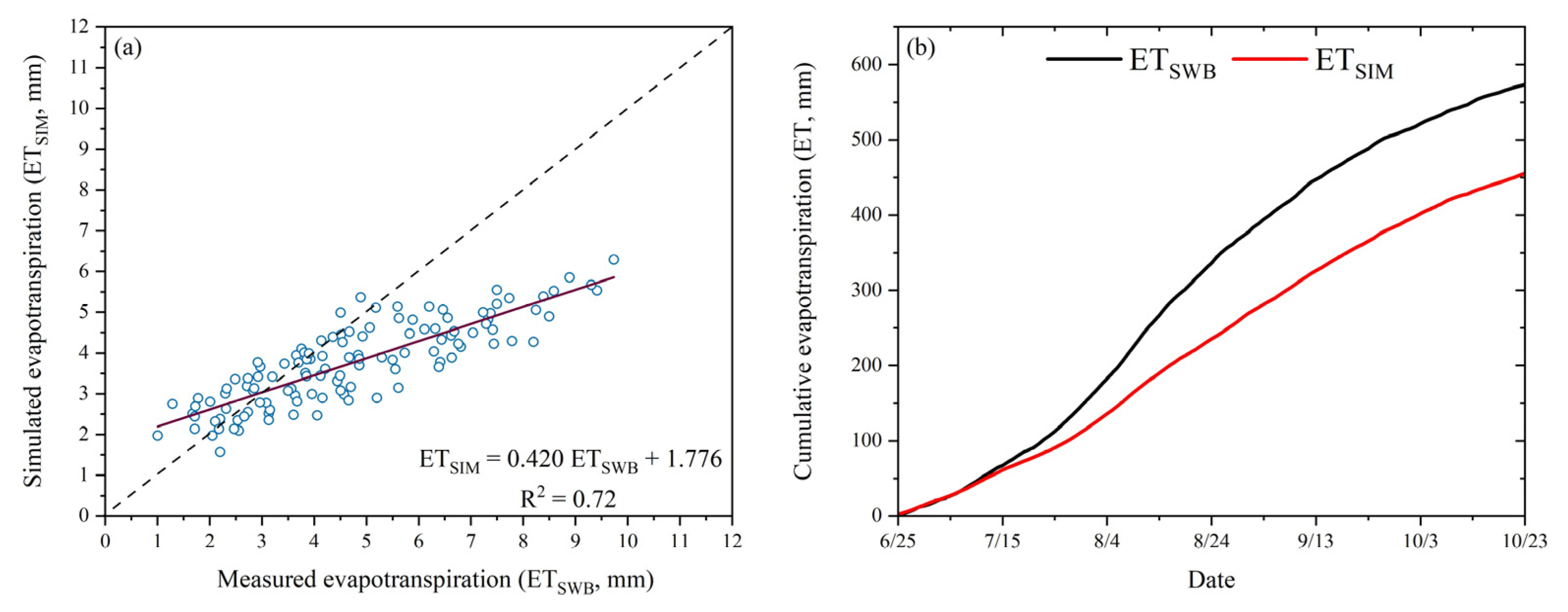

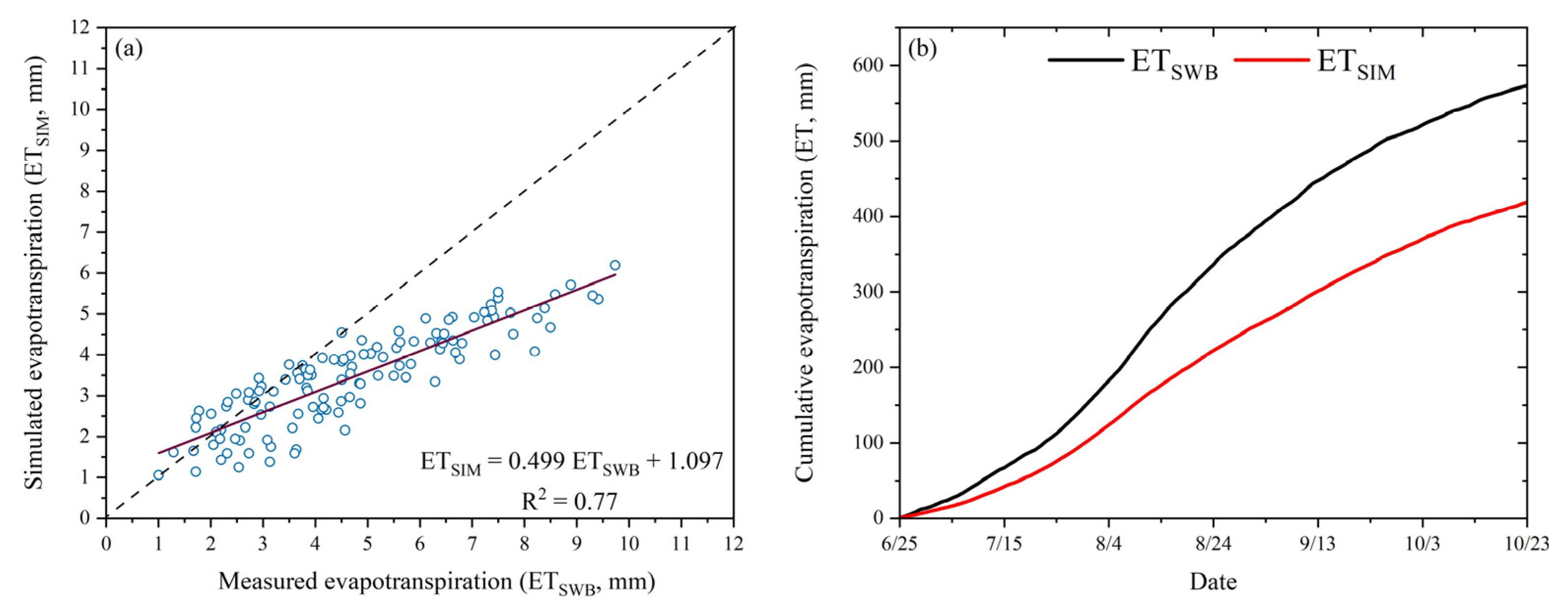

3.2.1. The ALEXI/DisALEXI Model

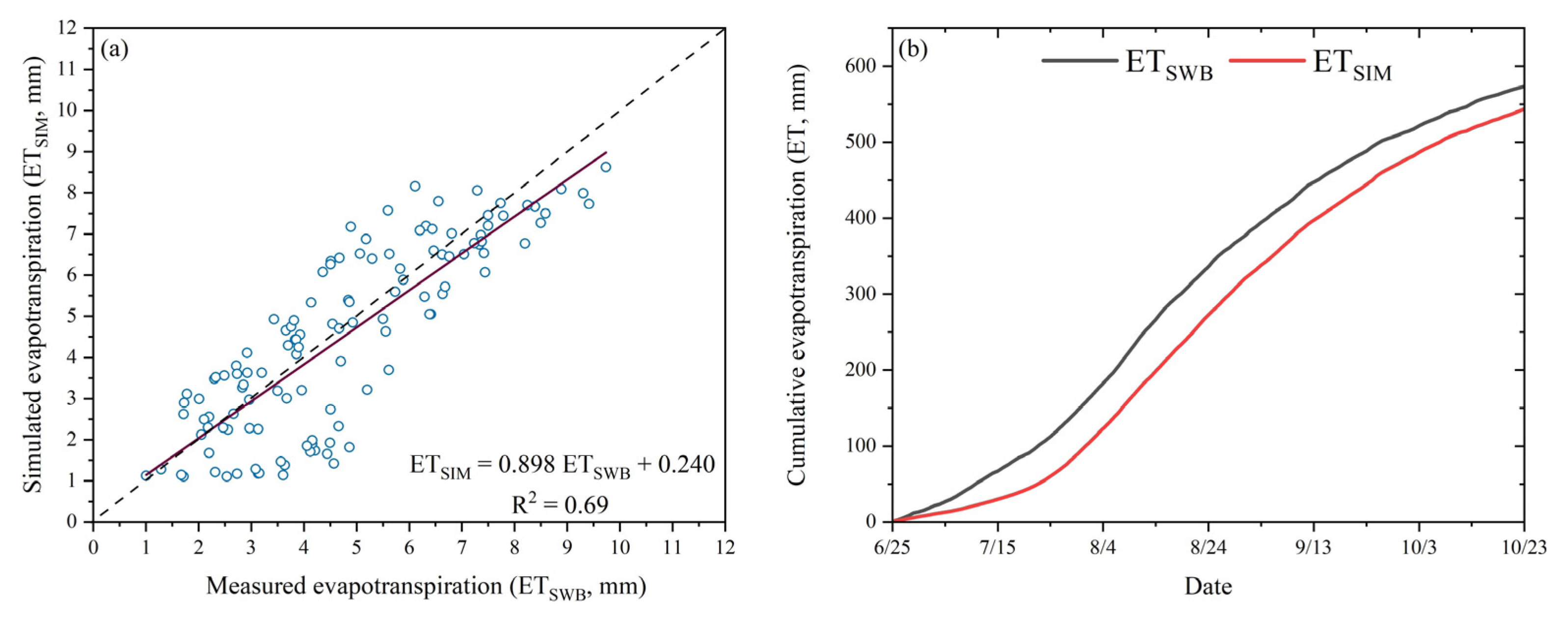

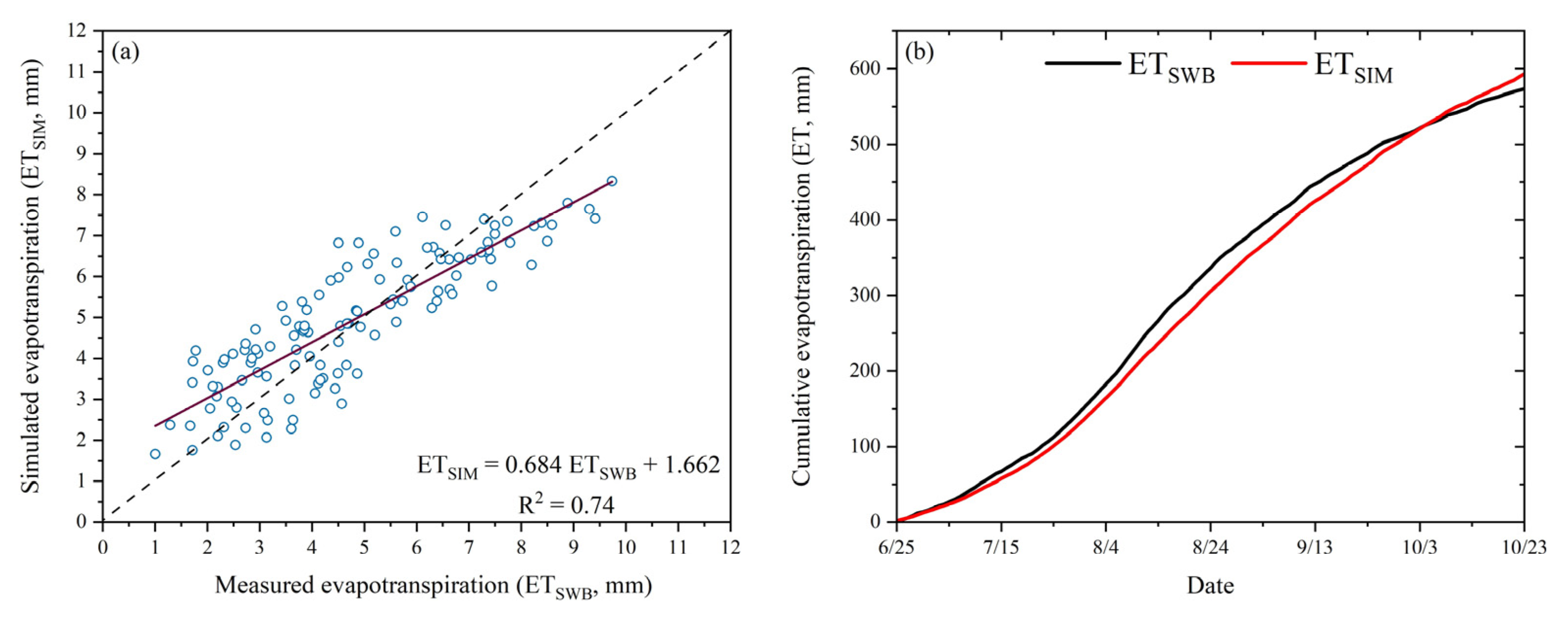

3.2.2. The eeMETRIC Model

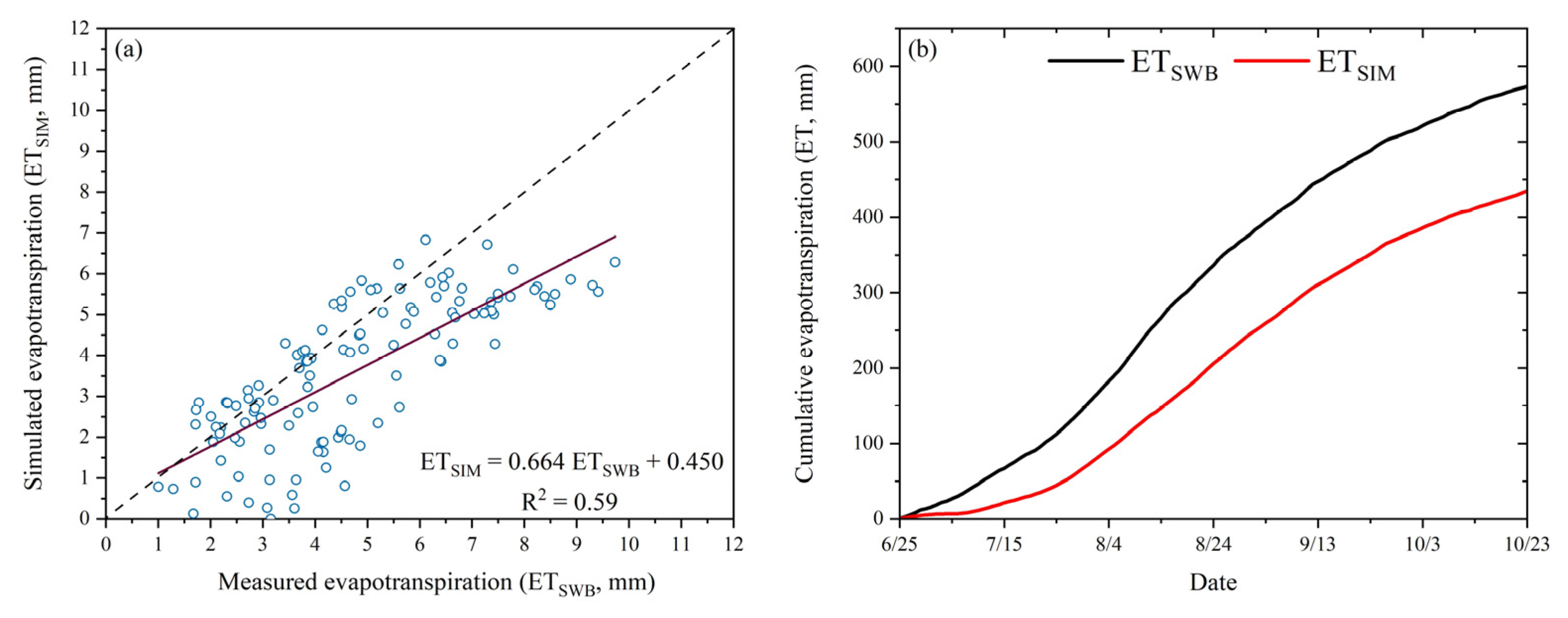

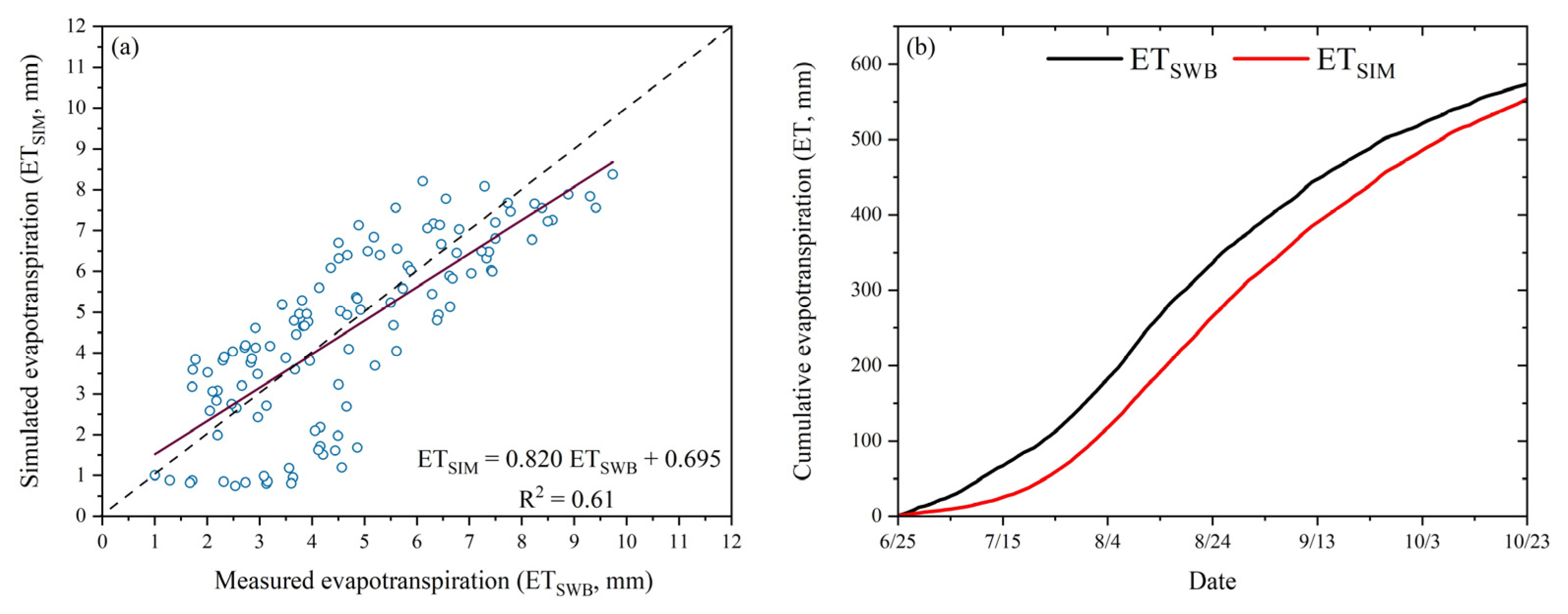

3.2.3. The geeSEBAL Model

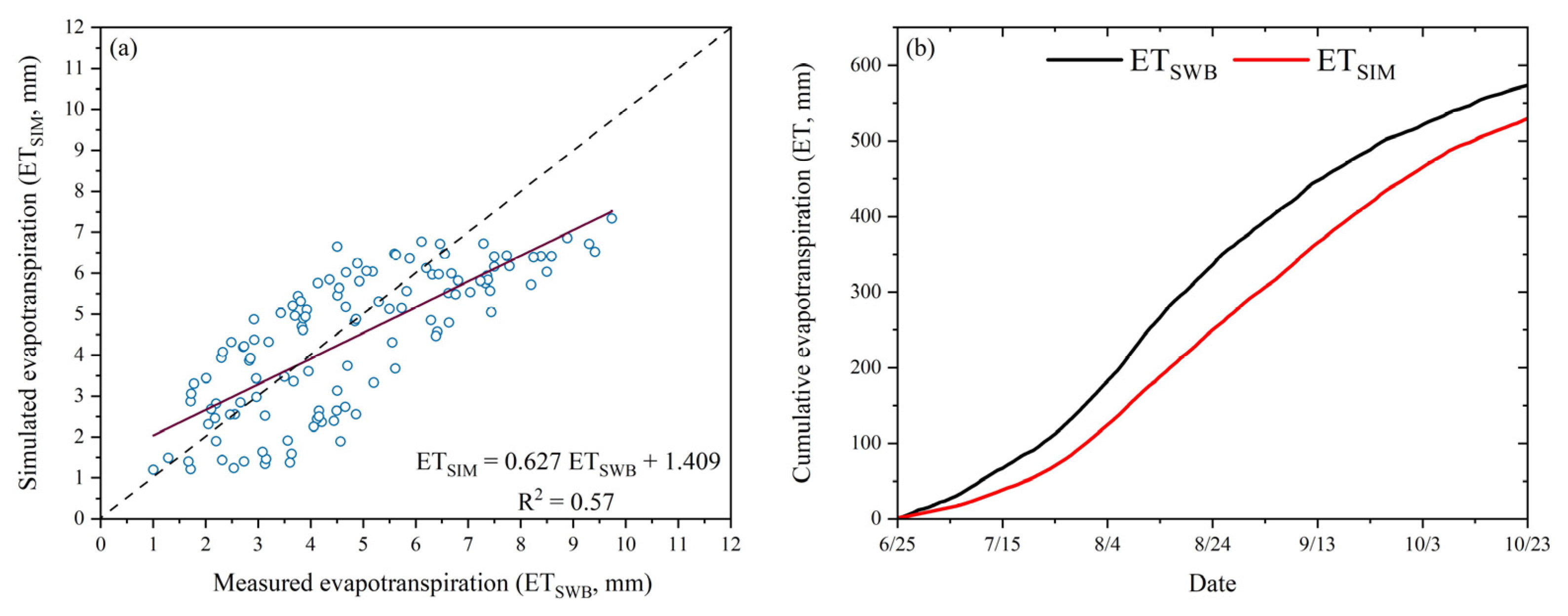

3.2.4. The PT-JPL Model

3.2.5. The SIMS Model

3.2.6. The SSEBop Model

3.2.7. The Ensemble Approach

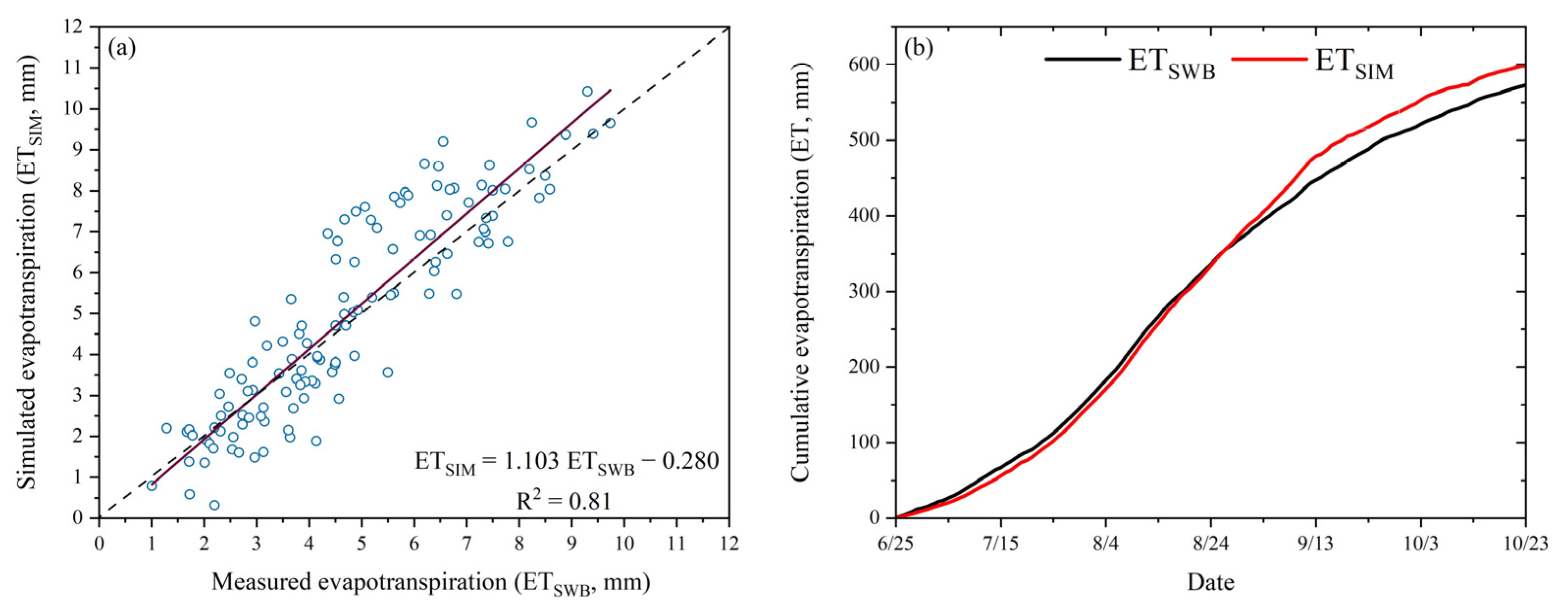

3.3. LI-710

3.4. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Galli, A.; Wiedmann, T.; Ercin, E.; Knoblauch, D.; Ewing, B.; Giljum, S. Integrating Ecological, Carbon and Water Footprint into a “Footprint Family” of Indicators: Definition and Role in Tracking Human Pressure on the Planet. Ecol. Indic. 2012, 16, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleick, P.H. A Look at Twenty-First Century Water Resources Development. Water Int. 2000, 25, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcamo, J.; Henrichs, T.; Rösch, T. World Water in 2025—Global Modeling and Scenario Analysis for the World Commission on Water for the 21st Century, Kassel World Water 27; Center for Environmental Systems Research: Kassel, Germany, 2000; pp. 922–939. [Google Scholar]

- Bruinsma, J. World Agriculture: Towards 2015/2030: An FAO Perspective; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2003; Volume 1, pp. 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Rosegrant, M.W.; Cai, X.; Cline, S.A. Global Water Outlook to 2025: Averting an Impending Crisis; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, S.; Zhu, G.; Qiu, D.; Li, R.; Jiao, Y.; Meng, G.; Lin, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, W.; Chen, L. Optimizing Irrigation in Arid Irrigated Farmlands Based on Soil Water Movement Processes: Knowledge from Water Isotope Data. Geoderma 2025, 460, 117440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Li, H.; Zhao, Y.; Shao, M.; Zhang, H.; Liu, M. Assessing Soil Water Balance to Optimize Irrigation Schedules of Flood-Irrigated Maize Fields with Different Cultivation Histories in the Arid Region. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 265, 107543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melton, F.S.; Huntington, J.; Grimm, R.; Herring, J.; Hall, M.; Rollison, D.; Erickson, T.; Allen, R.; Anderson, M.; Fisher, J.B.; et al. OpenET: Filling a Critical Data Gap in Water Management for the Western United States. JAWRA J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2022, 58, 971–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbeltagi, A.; Srivastava, A.; Cao, X.; Gautam, V.K.; Zerouali, B.; Aslam, M.R.; Salem, A.; Emami, H.; Elsadek, E.A. Bayesian-Optimized Machine Learning Boosts Actual Evapotranspiration Prediction in Water-Stressed Agricultural Regions of China. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 37548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senay, G.B.; Bohms, S.; Singh, R.K.; Gowda, P.H.; Velpuri, N.M.; Alemu, H.; Verdin, J.P. Operational Evapotranspiration Mapping Using Remote Sensing and Weather Datasets: A New Parameterization for the SSEB Approach. JAWRA J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2013, 49, 577–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagle, P.; Skaggs, T.H.; Gowda, P.H.; Northup, B.K.; Neel, J.P.S. Flux Variance Similarity-Based Partitioning of Evapotranspiration over a Rainfed Alfalfa Field Using High Frequency Eddy Covariance Data. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2020, 285–286, 107907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, A.N.; Hunsaker, D.J.; Bounoua, L.; Karnieli, A.; Luckett, W.E.; Strand, R. Remote Sensing of Evapotranspiration over the Central Arizona Irrigation and Drainage District, USA. Agronomy 2018, 8, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payero, J.O.; Irmak, S. Daily Energy Fluxes, Evapotranspiration and Crop Coefficient of Soybean. Agric. Water Manag. 2013, 129, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhungel, R.; Aiken, R.; Evett, S.R.; Colaizzi, P.D.; Marek, G.; Moorhead, J.E.; Baumhardt, R.L.; Brauer, D.; Kutikoff, S.; Lin, X. Energy Imbalance and Evapotranspiration Hysteresis Under an Advective Environment: Evidence From Lysimeter, Eddy Covariance, and Energy Balance Modeling. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48, e2020GL091203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evett, S.R.; Kustas, W.P.; Gowda, P.H.; Anderson, M.C.; Prueger, J.H.; Howell, T.A. Overview of the Bushland Evapotranspiration and Agricultural Remote Sensing EXperiment 2008 (BEAREX08): A Field Experiment Evaluating Methods for Quantifying ET at Multiple Scales. Adv. Water Resour. 2012, 50, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, J.M.; López-Urrea, R.; Valentín, F.; Caselles, V.; Galve, J.M. Lysimeter Assessment of the Simplified Two-Source Energy Balance Model and Eddy Covariance System to Estimate Vineyard Evapotranspiration. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2019, 274, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Bali, K.M.; Light, S.; Hessels, T.; Kisekka, I. Evaluation of Remote Sensing-Based Evapotranspiration Models against Surface Renewal in Almonds, Tomatoes and Maize. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 238, 106228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bambach, N.; Kustas, W.; Alfieri, J.; Prueger, J.; Hipps, L.; McKee, L.; Castro, S.J.; Volk, J.; Alsina, M.M.; McElrone, A.J. Evapotranspiration Uncertainty at Micrometeorological Scales: The Impact of the Eddy Covariance Energy Imbalance and Correction Methods. Irrig. Sci. 2022, 40, 445–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Yang, M.; Bakker, D.C.E.; Kitidis, V.; Bell, T.G. Uncertainties in Eddy Covariance Air–Sea CO2 Flux Measurements and Implications for Gas Transfer Velocity Parameterisations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2021, 21, 8089–8110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, R.M.; Di Tommasi, P.; Famulari, D.; Rana, G. Limitations of an Eddy-Covariance System in Measuring Low Ammonia Fluxes. Bound.-Layer Meteorol. 2021, 180, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Gutiérrez, V.; Stöckle, C.; Gil, P.M.; Meza, F.J. Evaluation of Penman-Monteith Model Based on Sentinel-2 Data for the Estimation of Actual Evapotranspiration in Vineyards. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsadek, E.A.; Ali, M.A.H.; Williams, C.; Thorp, K.R.; Elshikha, D.E.M. A Novel Framework for Predicting Daily Reference Evapotranspiration Using Interpretable Machine Learning Techniques. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbeltagi, A.; Katipoğlu, O.M.; Kartal, V.; Danandeh Mehr, A.; Berhail, S.; Elsadek, E.A. Advanced Reference Crop Evapotranspiration Prediction: A Novel Framework Combining Neural Nets, Bee Optimization Algorithm, and Mode Decomposition. Appl. Water Sci. 2024, 14, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawazir, A.S.; Luthy, R.; King, J.P.; Tanzy, B.F.; Solis, J. Assessment of the Crop Coefficient for Saltgrass under Native Riparian Field Conditions in the Desert Southwest. Hydrol. Process. 2014, 28, 6163–6171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.; Gao, F.; Knipper, K.; Hain, C.; Dulaney, W.; Baldocchi, D.; Eichelmann, E.; Hemes, K.; Yang, Y.; Medellin-Azuara, J.; et al. Field-Scale Assessment of Land and Water Use Change over the California Delta Using Remote Sensing. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knipper, K.R.; Kustas, W.P.; Anderson, M.C.; Alfieri, J.G.; Prueger, J.H.; Hain, C.R.; Gao, F.; Yang, Y.; McKee, L.G.; Nieto, H.; et al. Evapotranspiration Estimates Derived Using Thermal-Based Satellite Remote Sensing and Data Fusion for Irrigation Management in California Vineyards. Irrig. Sci. 2019, 37, 431–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knipper, K.R.; Kustas, W.P.; Anderson, M.C.; Alsina, M.M.; Hain, C.R.; Alfieri, J.G.; Prueger, J.H.; Gao, F.; McKee, L.G.; Sanchez, L.A. Using High-Spatiotemporal Thermal Satellite ET Retrievals for Operational Water Use and Stress Monitoring in a California Vineyard. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.M.; Liu, J. Evolution of Evapotranspiration Models Using Thermal and Shortwave Remote Sensing Data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 237, 111594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volk, J.M.; Huntington, J.L.; Melton, F.S.; Allen, R.; Anderson, M.; Fisher, J.B.; Kilic, A.; Ruhoff, A.; Senay, G.B.; Minor, B.; et al. Assessing the Accuracy of OpenET Satellite-Based Evapotranspiration Data to Support Water Resource and Land Management Applications. Nat. Water 2024, 2, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawalbeh, Z.M.; Bawazir, A.S.; Fernald, A.; Sabie, R.; Heerema, R.J. Assessing Satellite-Derived OpenET Platform Evapotranspiration of Mature Pecan Orchard in the Mesilla Valley, New Mexico. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peddinti, S.R.; Kisekka, I. Evaluation of the LI-710 Evapotranspiration Sensor in Comparison to Full Eddy Covariance for Monitoring Energy Fluxes in Perennial and Annual Crops. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 313, 109501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burba, G.; Miller, B.; Fratini, G.; Inkenbrandt, P.C.; Xu, L. Simple Direct Evapotranspiration Measurements with a New Cost-Optimized ET Flux Sensor. In Proceedings of the 104th AMS Annual Meeting (AMS), Baltimore, MD, USA, 28 January–1 February 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Attalah, S.; Elsadek, E.A.; Waller, P.; Hunsaker, D.J.; Thorp, K.R.; Bautista, E.; Williams, C.; Wall, G.; Orr, E.; Elshikha, D.E.M. Evaluation and Comparison of OpenET Models for Estimating Soil Water Depletion of Irrigated Alfalfa in Arizona. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 320, 109850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshikha, D.E.; Attalah, S.; Elsadek, E.A.; Waller, P.; Thorp, K.; Sanyal, D.; Bautista, E.; Norton, R.; Hunsaker, D.; Williams, C.; et al. The Impact of Gravity Drip and Flood Irrigation on Development, Water Productivity, and Fiber Yield of Cotton in Semi-Arid Conditions of Arizona. In Proceedings of the 2024 ASABE Annual International Meeting, Anaheim, CA, USA, 28–31 July 2024; American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers: St. Joseph, MI, USA, 2024; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Elsadek, E.A.; Attalah, S.; Waller, P.; Norton, R.; Hunsaker, D.J.; Williams, C.; Thorp, K.R.; Orr, E.; Elshikha, D.E.M. Simulating Water Use and Yield for Full and Deficit Flood-Irrigated Cotton in Arizona, USA. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.G.; Pereira, L.S.; Raes, D.; Smith, M. Crop Evapotranspiration-Guidelines for Computing Crop Water Requirements-FAO Irrigation and Drainage Paper 56; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hunsaker, D.J.; Barnes, E.M.; Clarke, T.R.; Fitzgerald, G.J.; Pinter, P.J., Jr. Cotton Irrigation Scheduling Using Remotely Sensed and FAO-56 Basal Crop Coefficients. Trans. ASAE 2005, 48, 1395–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.C.; Norman, J.M.; Mecikalski, J.R.; Otkin, J.A.; Kustas, W.P. A Climatological Study of Evapotranspiration and Moisture Stress across the Continental United States Based on Thermal Remote Sensing: 1. Model Formulation. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2007, 112, D10117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.G.; Tasumi, M.; Morse, A.; Trezza, R. A Landsat-Based Energy Balance and Evapotranspiration Model in Western US Water Rights Regulation and Planning. Irrig. Drain. Syst. 2005, 19, 251–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.G.; Tasumi, M.; Trezza, R. Satellite-Based Energy Balance for Mapping Evapotranspiration with Internalized Calibration (METRIC)—Model. J. Irrig. Drain. Eng. 2007, 133, 380–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.; Irmak, A.; Trezza, R.; Hendrickx, J.M.H.; Bastiaanssen, W.; Kjaersgaard, J. Satellite-based ET Estimation in Agriculture Using SEBAL and METRIC. Hydrol. Process. 2011, 25, 4011–4027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastiaanssen, W.G.M.; Menenti, M.; Feddes, R.A.; Holtslag, A.A.M. A Remote Sensing Surface Energy Balance Algorithm for Land (SEBAL). 1. Formulation. J. Hydrol. 1998, 212–213, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laipelt, L.; Henrique Bloedow Kayser, R.; Santos Fleischmann, A.; Ruhoff, A.; Bastiaanssen, W.; Erickson, T.A.; Melton, F. Long-Term Monitoring of Evapotranspiration Using the SEBAL Algorithm and Google Earth Engine Cloud Computing. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2021, 178, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, J.B.; Tu, K.P.; Baldocchi, D.D. Global Estimates of the Land–Atmosphere Water Flux Based on Monthly AVHRR and ISLSCP-II Data, Validated at 16 FLUXNET Sites. Remote Sens. Environ. 2008, 112, 901–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senay, G.B. Satellite Psychrometric Formulation of the Operational Simplified Surface Energy Balance (SSEBop) Model for Quantifying and Mapping Evapotranspiration. Appl. Eng. Agric. 2018, 34, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melton, F.S.; Johnson, L.F.; Lund, C.P.; Pierce, L.L.; Michaelis, A.R.; Hiatt, S.H.; Guzman, A.; Adhikari, D.D.; Purdy, A.J.; Rosevelt, C.; et al. Satellite Irrigation Management Support With the Terrestrial Observation and Prediction System: A Framework for Integration of Satellite and Surface Observations to Support Improvements in Agricultural Water Resource Management. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2012, 5, 1709–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.S.; Paredes, P.; Melton, F.; Johnson, L.; Wang, T.; López-Urrea, R.; Cancela, J.J.; Allen, R.G. Prediction of Crop Coefficients from Fraction of Ground Cover and Height. Background and Validation Using Ground and Remote Sensing Data. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 241, 106197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attalah, S.; Elsadek, E.A.; Waller, P.; Hunsaker, D.; Thorp, K.; Bautista, E.; Williams, C.; Wall, G.; Orr, E.; Elshikha, D.E. Evaluating the Performance of OpenET Models for Alfalfa in Arizona. In Proceedings of the 2024 ASABE Annual International Meeting, Anaheim, CA, USA, 28–31 July 2024; American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers: St. Joseph, MI, USA, 2024; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson, P.D.; Porter, J.R.; Wilson, D.R. A Test of the Computer Simulation Model ARCWHEAT1 on Wheat Crops Grown in New Zealand. Field Crops Res. 1991, 27, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brisson, N.; Ruget, F.; Gate, P.; Lorgeou, J.; Nicoullaud, B.; Tayot, X.; Plenet, D.; Jeuffroy, M.-H.; Bouthier, A.; Ripoche, D.; et al. STICS: A Generic Model for Simulating Crops and Their Water and Nitrogen Balances. II. Model Validation for Wheat and Maize. Agronomie 2002, 22, 69–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntington, J.L.; Pearson, C.; Minor, B.; Volk, J.; Morton, C.; Melton, F.; Allen, R. Appendix G: Upper Colorado River Basin OpenET Intercomparison Summary; US Bureau of Reclamation: Washington, DC, USA, 2022.

- Abbasi, N.; Nouri, H.; Nagler, P.; Didan, K.; Chavoshi Borujeni, S.; Barreto-Muñoz, A.; Opp, C.; Siebert, S. Crop Water Use Dynamics over Arid and Semi-Arid Croplands in the Lower Colorado River Basin. Eur. J. Remote Sens. 2023, 56, 2259244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiß, M.; Menzel, L. A Global Comparison of Four Potential Evapotranspiration Equations and Their Relevance to Stream Flow Modelling in Semi-Arid Environments. Adv. Geosci. 2008, 18, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabari, H.; Talaee, P.H. Local Calibration of the Hargreaves and Priestley-Taylor Equations for Estimating Reference Evapotranspiration in Arid and Cold Climates of Iran Based on the Penman-Monteith Model. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2011, 16, 837–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K.; Irmak, A. Treatment of Anchor Pixels in the METRIC Model for Improved Estimation of Sensible and Latent Heat Fluxes. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2011, 56, 895–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagle, P.; Bhattarai, N.; Gowda, P.H.; Kakani, V.G. Performance of Five Surface Energy Balance Models for Estimating Daily Evapotranspiration in High Biomass Sorghum. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2017, 128, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.G.; Morton, C.; Kamble, B.; Kilic, A.; Huntington, J.; Thau, D.; Gorelick, N.; Erickson, T.; Moore, R.; Trezza, R.; et al. EEFlux: A Landsat-Based Evapotranspiration Mapping Tool on the Google Earth Engine. In Proceedings of the 2015 ASABE/IA Irrigation Symposium: Emerging Technologies for Sustainable Irrigation—A Tribute to the Career of Terry Howell, Sr. Conference Proceedings, Long Beach, CA, USA, 10–12 November 2025; American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers: St. Joseph, MI, USA, 2015; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Irmak, A.; Ratcliffe, I.; Ranade, P.; Hubbard, K.G.; Singh, R.K.; Kamble, B.; Kjaersgaard, J. Estimation of Land Surface Evapotranspiration with a Satellite Remote Sensing Procedure. Gt. Plains Res. 2011, 21, 73–88. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.; Senay, G.B.; Singh, R.K.; Verdin, J.P. Uncertainty Analysis of the Operational Simplified Surface Energy Balance (SSEBop) Model at Multiple Flux Tower Sites. J. Hydrol. 2016, 536, 384–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhungel, R.; Anderson, R.G.; French, A.N.; Skaggs, T.H.; Ajami, H.; Wang, D. Intercomparison of Citrus Evapotranspiration among Eddy Covariance, OpenET Ensemble Models, and the Water and Energy Balance Model (BAITSSS). Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 304, 109066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Profile Depth, m | FC, m3 m−3 | PWP, m3 m−3 | Soil Texture | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sand, % | Silt, % | Clay, % | Texture Class | |||

| 0.0–0.3 | 0.153 | 0.064 | 69.0 | 23.0 | 8.0 | Sandy Loam |

| 0.3–0.6 | 0.148 | 0.064 | 71.0 | 22.0 | 8.0 | Sandy Loam |

| 0.6–0.9 | 0.130 | 0.058 | 77.0 | 17.0 | 7.0 | Loam Sandy |

| 0.9–1.2 | 0.144 | 0.075 | 78.0 | 12.0 | 10.0 | Sandy Loam |

| 1.2–1.5 | 0.129 | 0.063 | 80.0 | 13.0 | 8.0 | Loam Sandy |

| 1.5–1.8 | 0.107 | 0.051 | 85.0 | 9.0 | 6.0 | Loam Sandy |

| ALEXI/DisALEXI | ETSWB, mm | ETSIM, mm | Statistical Indicator | |||

| NRMSE, % | MBE, mm | Se, % | R2 | |||

| 573.31 | 455.36 | 34.40 | −0.97 | −20.57 | 0.72 | |

| eeMETRIC | ETSWB, mm | ETSIM, mm | Statistical Indicator | |||

| NRMSE, % | MBE, mm | Se, % | R2 | |||

| 573.31 | 543.88 | 26.88 | −0.24 | −5.13 | 0.69 | |

| geeSEBAL | ETSWB, mm | ETSIM, mm | Statistical Indicator | |||

| NRMSE, % | MBE, mm | Se, % | R2 | |||

| 573.31 | 434.99 | 36.92 | −1.14 | −24.13 | 0.59 | |

| PT-JPL | ETSWB, mm | ETSIM, mm | Statistical Indicator | |||

| NRMSE, % | MBE, mm | Se, % | R2 | |||

| 573.31 | 418.96 | 36.46 | −1.28 | −26.92 | 0.77 | |

| SIMS | ETSWB, mm | ETSIM, mm | Statistical Indicator | |||

| NRMSE, % | MBE, mm | Se, % | R2 | |||

| 573.31 | 592.93 | 22.57 | 0.16 | 3.42 | 0.74 | |

| SSEBop | ETSWB, mm | ETSIM, mm | Statistical Indicator | |||

| NRMSE, % | MBE, mm | Se, % | R2 | |||

| 573.31 | 554.10 | 29.85 | −0.16 | −3.35 | 0.61 | |

| Ensemble | ETSWB, mm | ETSIM, mm | Statistical Indicator | |||

| NRMSE, % | MBE, mm | Se, % | R2 | |||

| 573.31 | 529.85 | 29.62 | −0.36 | −7.58 | 0.57 | |

| LI-710 | ETSWB, mm | ETSIM, mm | Statistical Indicator | |||

| NRMSE, % | MBE, mm | Se, % | R2 | |||

| 573.31 | 598.52 | 23.68 | 0.21 | 4.40 | 0.81 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Elsadek, E.A.; Attalah, S.; Williams, C.; Thorp, K.R.; Wang, D.; Elshikha, D.E.M. Comparing Cotton ET Data from a Satellite Platform, In Situ Sensor, and Soil Water Balance Method in Arizona. Agriculture 2026, 16, 228. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16020228

Elsadek EA, Attalah S, Williams C, Thorp KR, Wang D, Elshikha DEM. Comparing Cotton ET Data from a Satellite Platform, In Situ Sensor, and Soil Water Balance Method in Arizona. Agriculture. 2026; 16(2):228. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16020228

Chicago/Turabian StyleElsadek, Elsayed Ahmed, Said Attalah, Clinton Williams, Kelly R. Thorp, Dong Wang, and Diaa Eldin M. Elshikha. 2026. "Comparing Cotton ET Data from a Satellite Platform, In Situ Sensor, and Soil Water Balance Method in Arizona" Agriculture 16, no. 2: 228. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16020228

APA StyleElsadek, E. A., Attalah, S., Williams, C., Thorp, K. R., Wang, D., & Elshikha, D. E. M. (2026). Comparing Cotton ET Data from a Satellite Platform, In Situ Sensor, and Soil Water Balance Method in Arizona. Agriculture, 16(2), 228. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16020228