Detoxification Responses of Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) to Serratia marcescens (Bizio) Strain Tapa21 Infection Revealed by Transcriptomics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Growth of Plants and Rearing of Insects

2.2. Isolation of Bacterial Strains

2.3. Screening and Identification of Biocontrol Bacterial Strains

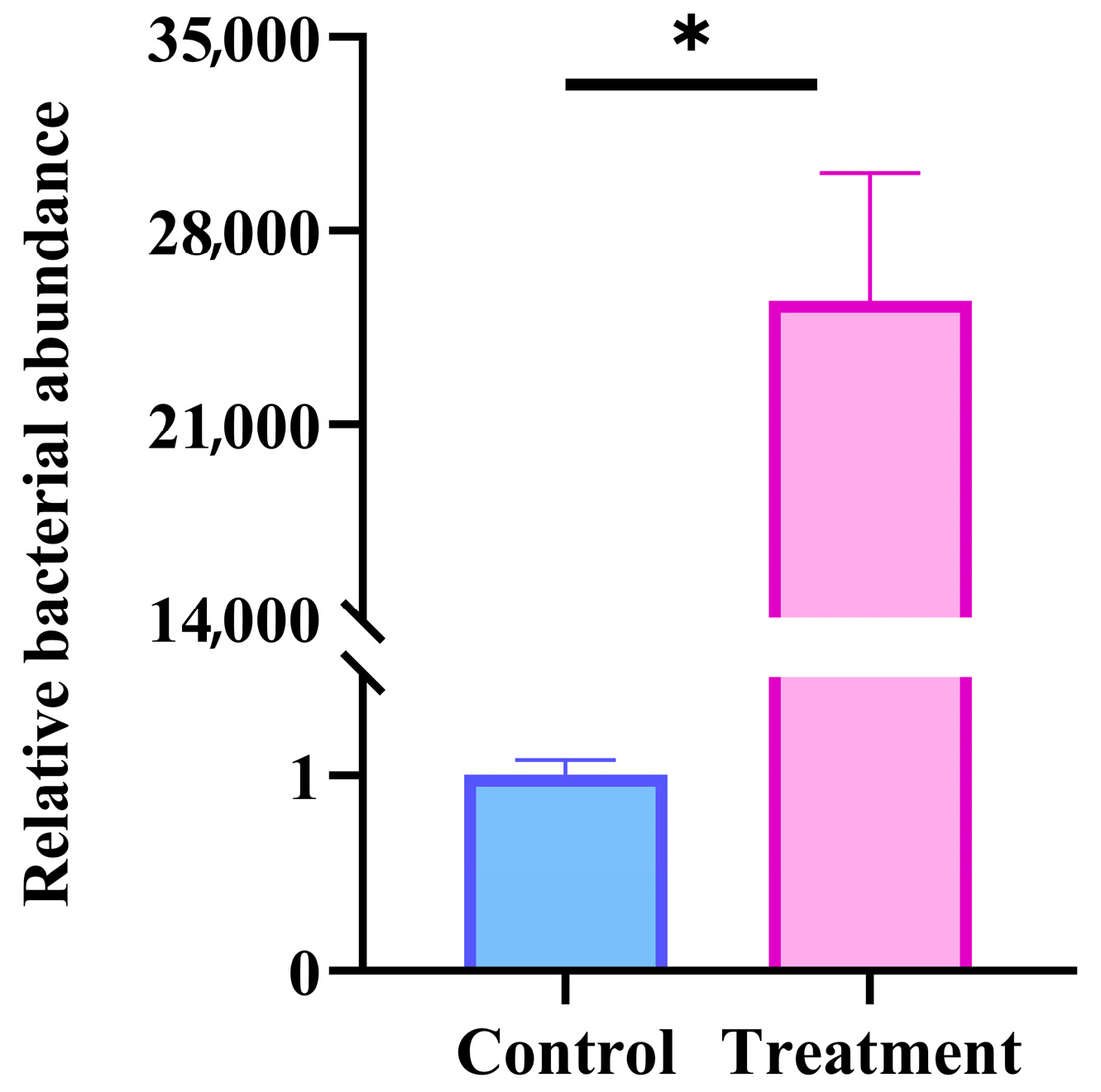

2.4. Detection of the Bacterial Load in Tuta absoluta Infected by Tapa21

2.5. Pathogenic Test of Tapa21 Against Tuta absoluta

2.6. Sample Collection and RNA Extraction

2.7. Library Construction and Sequencing

2.8. Data Preprocessing and Quality Control

2.9. Differential Gene Expression Analysis

2.10. Functional Annotation and Pathway Enrichment Analysis

2.11. Analysis of Gene Expression Levels

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

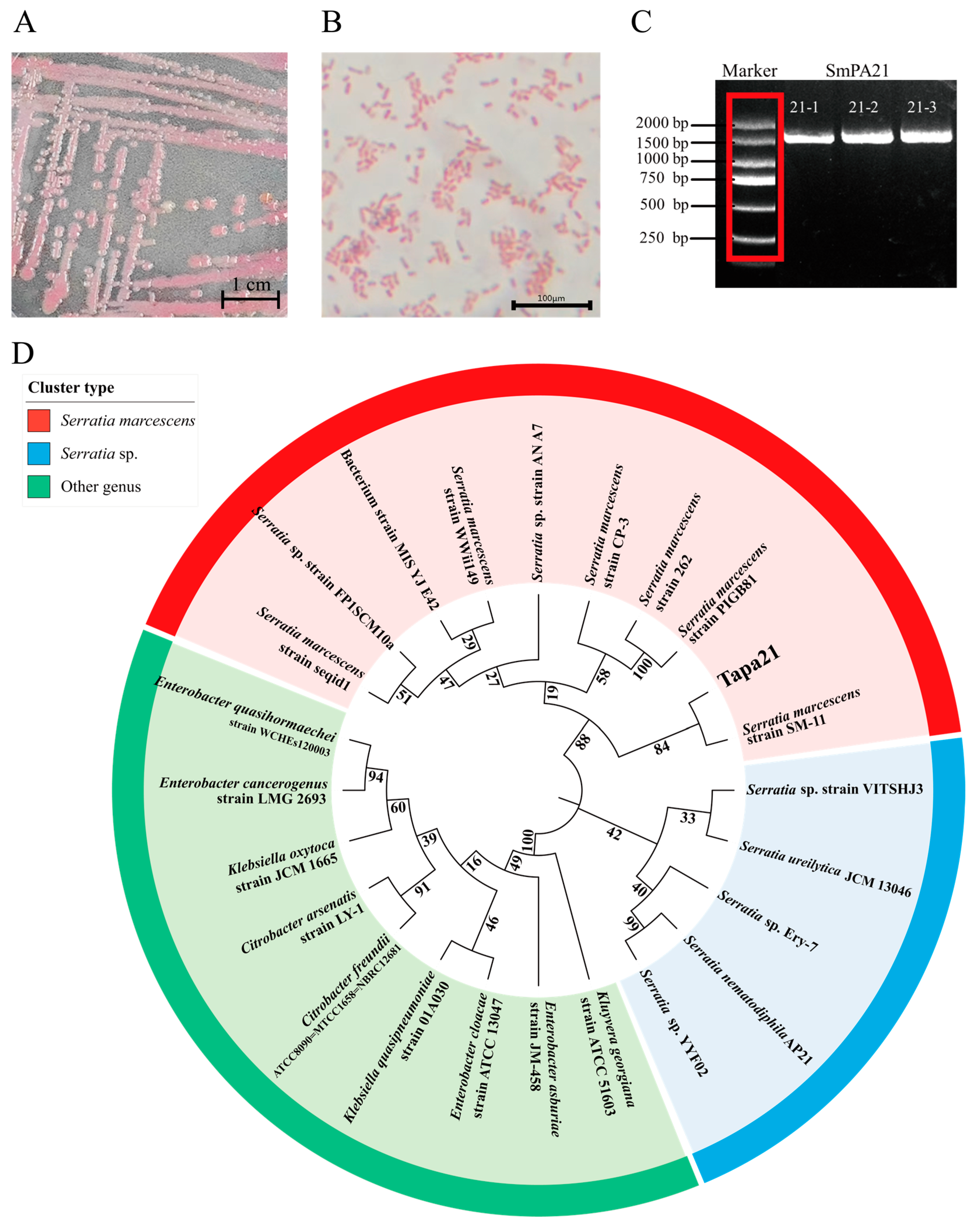

3.1. Isolation of Bacteria and Screening of Biocontrol Bacteria

3.2. Identification of Biocontrol Bacteria

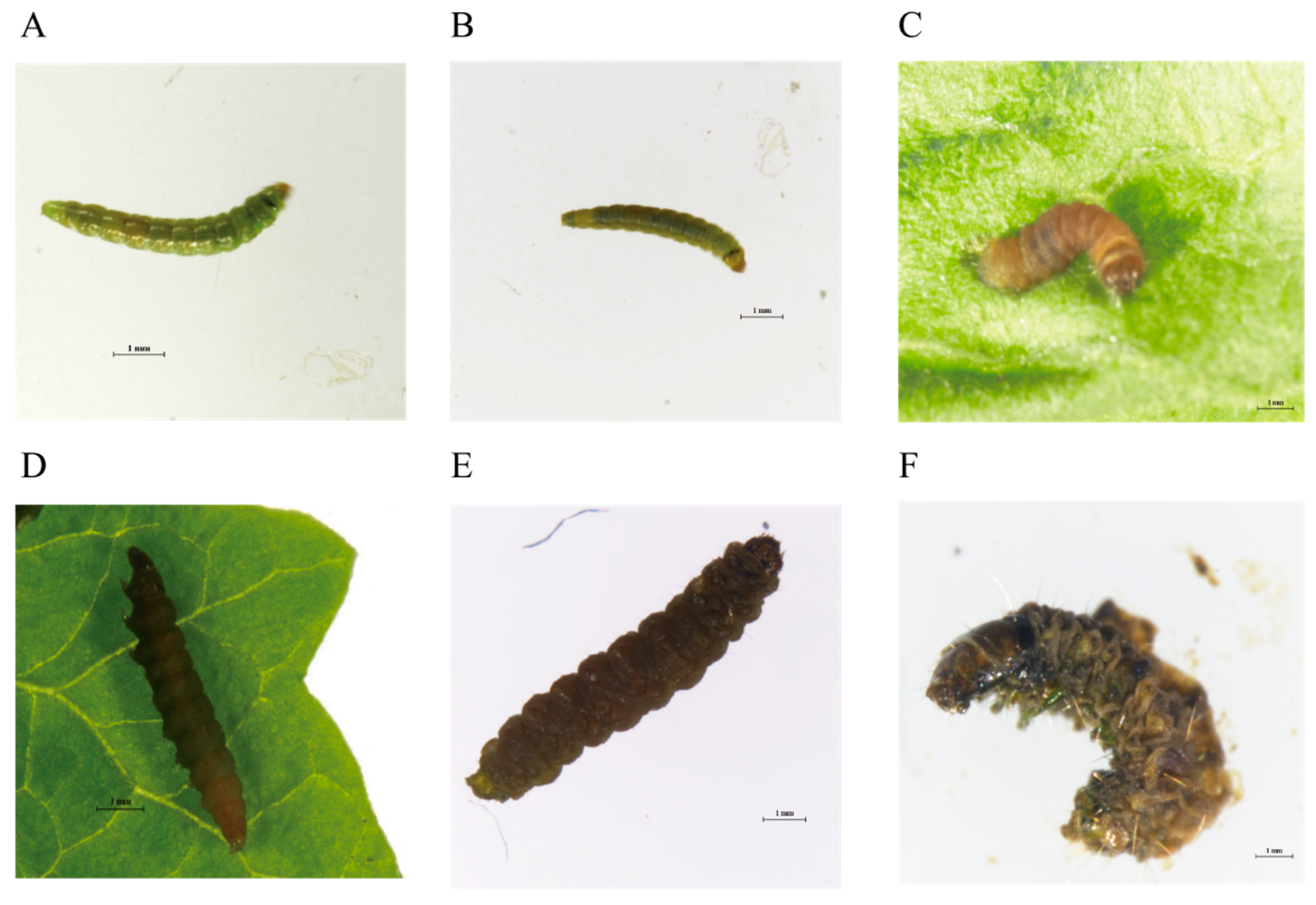

3.3. Symptoms of Tuta absoluta Infected by Tapa21

3.4. Pathogenicity Determination of Tapa21 Against Tuta absoluta

3.5. Transcriptome Profiling of Tuta absoluta

3.5.1. Analysis of RNA-Sequencing Data

3.5.2. Identification and Functional Analysis of DEGs

3.5.3. GO Enrichment Analysis of DEGs

3.5.4. KEGG Pathway Enrichment Analysis of DEGS

3.5.5. Pathway Analysis

3.6. Experimental Validation of Transcriptomic Data via RT-qPCR

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Patricia, E.C.C.; Mark, A.M. Classification of Tuta absoluta (Meyrick, 1917) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae: Gelechiinae: Gnorimoschemini) Based on Cladistic Analysis of Morphology. Proc. Entomol. Soc. Wash. 2021, 123, 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Urbaneja, A.; Vercher, R.; Navarro-Llopis, V.; Porcuna Coto, J.L.; García-Marí, F. La polilla del tomate, Tuta absoluta. Phytoma España La Rev. Prof. De Sanid. Veg. 2007, 194, 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, M.; Bhattarai, N.; Pandey, P.; Chaudhary, P.; Katuwal, R.J.; Khanal, D. A review on biology and possible management strategies of tomato leaf miner, Tuta absoluta (Meyrick), Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae in Nepal. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPPO Global Database Tuta absoluta (GNORAB). 2024. Available online: https://gd.eppo.int/taxon/GNORAB/distribution (accessed on 30 October 2024).

- Mahlangu, L.; Sibisi, P.; Nofemela, R.S.; Ngmenzuma, T.; Ntushelo, K. The differential effects of Tuta absoluta infestations on the physiological processes and growth of tomato, potato, and eggplant. Insects 2022, 13, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannou, A.J.; Romeis, J.; Collatz, J. Response of the tomato leaf miner Phthorimaea absoluta to wild and domesticated tomato genotypes. Pest Manag. Sci. 2025, 81, 1345–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, R.; Barman, A.K.; Sharma, S.R.; Kafle, L.; Kim, S.M.; Lee, K.Y. Biology, distribution, and management of invasive South American tomato leafminer, Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) (Lepidoptera; Gelechiidae), in Asia. Arch. Insect Biochem. 2023, 114, e22056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivekanandhan, P.; Swathy, K.; Sarayut, P.; Patcharin, K. Biology, classification, and entomopathogen-based management and their mode of action on Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) in Asia. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1429690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.F.; Ma, D.Y.; Wang, Y.S.; Gao, Y.H.; Liu, W.X.; Zhang, R.; Fu, W.J.; Xian, X.Q.; Wang, J.; Kuang, M. First report of the South American tomato leafminer, Tuta absoluta (Meyrick), in China. J. Inter. Agri. 2020, 19, 1912–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Huang, C.; Xian, X.; Liu, W.X.; Wan, F.H.; Desneux, N.; Zhang, G.F.; Zhang, Y.B. Modeling the spread patterns and climatic niche dynamics of the tomato leaf miner Tuta absoluta following its invasion of China. J. Pest Sci. 2025, 98, 2417–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.F.; Zhang, Y.B.; Xian, X.Q.; Liu, W.X.; Li, P.; Liu, W.C.; Liu, H.; Feng, X.D.; Lv, Z.C.; Wang, Y.S.; et al. Damage of an important and newly invaded agricultural pest, Phthorimaea absoluta, and its prevention and management measures. J. Plant Prot. 2022, 48, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.H.; Wang, X.S.; Zhao, X.Y.; Jia, D. Analysis of suitability of quarantine pest Tuta absoluta in China. Shaanxi J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2022, 50, 579–585. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.K.; Wu, S.Y.; Lei, Z.R. Occurrence, harm and control of tomato leaf miner, a new agricultural invasive organism in Ningxia. Chin. Cuc. Veg. 2022, 35, 111–116. [Google Scholar]

- Tarusikirwa, V.L.; Machekano, H.; Mutamiswa, R.; Chidawanyika, F.; Nyamukondiwa, C. Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) on the “Offensive” in Africa: Prospects for integrated management initiatives. Insects 2020, 11, 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.Y.; Zhang, Q.K.; Zhang, Y.; Diao, H.L.; Zhang, Z.K.; Tang, L.D.; Zhang, T.Y.; Zhang, X.M.; Lei, Z.R. Advances in integrated pest management of Phthorimaea absoluta. J. Plant Prot. 2023, 49, 6–12+21. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, X.J.; Zhang, C.; He, Y.Q.; Zhou, Q.H.; Li, D.; Zheng, L.M.; Ouyang, X.; Zhang, Z.H. Analysis of world tomato production based on FAO data from 1980 to 2019. Hunan Agric. Sci. 2021, 11, 104–108. [Google Scholar]

- Xi, M.Z.; Wang, Z.L.; Liu, X.X.; Li, Z.H.; Zhang, X.; Lv, Z.Z.; Han, P. Assessment of the economic loss to the tomato industry caused by Tuta absoluta in China based on @RISK. J. Biosaf. 2022, 31, 300–308. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, J.E.; Assis, C.; Ribeiro, L.; Siqueira, H. Field-evolved resistance and cross-resistance of Brazilian Tuta absoluta (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) populations to diamide insecticides. J. Econ. Entomol. 2016, 109, 2190–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, X.; Yin, Y.Q.; Li, X.Y.; He, K.; Zhao, X.Q.; Li, X.Y.; Luo, X.Y.; Mei, Y.; Wang, Z.Q.; et al. A chromosome-level genome assembly of tomato pinworm, Tuta absoluta. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, S.Y.; Ming, F.C.; Dai, Y.T.; Wang, K.; Dong, R.; Zhang, Y.J.; Wang, S.L. Occurrence, pesticide resistance, and integrated pest management of the invasive pest Tuta absoluta. China Veg. 2025, 06, 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.F.; Zhang, Y.B.; Liu, W.X.; Zhang, F.; Xian, X.Q.; Wan, F.H.; Feng, X.D.; Zhao, J.N.; Liu, H.; Liu, W.C.; et al. Effect of trap color and position on the trapping efficacy of Tuta absoluta. Chin. Agric. Sci. 2021, 54, 2343–2354. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, X.B.; Meng, J.Z.; Zhao, G.A.; Yang, D.M.; Yang, Y.Y.; Chen, X.J.; Shen, Y.F. Evaluation of trapping effect on Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) with different hanging heights of traps and different sex attractants in field. Plant Quar. 2023, 37, 44–47. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, W.X.; Li, L.L.; Jiang, W.F.; Cheng, Y.Z.; Song, Y.Y.; Cui, H.Y.; Lv, S.H.; Yu, Y.; Men, X.Y. Hazard risk of Tuta absoluta to tomato industry in Shandong province and its monitoring and control research progress. Shandong Agric. Sci. 2023, 55, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Lv, B.Q.; Lu, H.; Wang, S.; Tang, J.H.; Wang, S.C. Invasive risk analysis of the tomato leafminer Tuta absoluta in Hainan Province. Pertanika J. Trop. Agric. 2023, 43, 66–73. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, W.; Lu, L.; Hu, L.T.; Liu, L.; He, N. Prediction of the potential global distribution of Tuta absoluta different periods under climate change. China Plant Prot. 2025, 45, 30–38+95. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.L.; Shi, C.H.; Xu, D.D.; Zhang, Y.J. Screening of efficient insecticide against invasive Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) and detection of its resistance gene mutation. China Veg. 2021, 11, 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Siqueira, H.Á.A.; Guedes, R.N.C.; Picanço, M.C. Insecticide resistance in populations of Tuta absoluta (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae). Agric. Forest Entomol. 2000, 2, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lietti, M.M.; Botto, E.; Alzogaray, R.A. Insecticide resistance in argentine populations of Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae). Neotrop. Entomol. 2005, 34, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, R.; Roditakis, E.; Campos, M.; Haddi, K.; Bielza, P.; Siqueira, H.; Tsagkarakou, A.; Vontas, J.; Nauen, R. Insecticide resistance in the tomato pinworm Tuta absoluta: Patterns, spread, mechanisms, management and outlook. J. Pest Sci. 2019, 92, 1329–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langa, T.P.; Dantas, K.C.; Pereira, D.L.; de Oliveira, M.; Ribeiro, L.M.; Siqueira, H.A. Basis and monitoring of methoxyfenozide resistance in the South American tomato pinworm Tuta absoluta. J. Pest Sci. 2022, 95, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osama, E.; Ahmed, B.; Fawzy, E. Impact of pesticides on non-target invertebrates in agricultural ecosystems. Pest. Biochem. Physiol. 2024, 202, 105974. [Google Scholar]

- Gruss, I.; Bączek, P.; Ćwieląg-Piasecka, I.; Jędrzejewski, S.; Magiera-Dulewicz, J.; Twardowska, K. Assessing the ecotoxicological effects of pesticides on non-target plant species. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2025, 197, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, N.F.; Fu, L.; Dainese, M.; Kiær, L.P.; Hu, Y.Q.; Xin, F.F.; Goulson, D.; Woodcock, B.A.; Vanbergen, A.J.; Spurgeon, D.J.; et al. Pesticides have negative effects on non-target organisms. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaoğlan, B.; Alkassab, A.T.; Borges, S.; Fisher, T.; Link-Vrabie, C.; McVey, E.; Ortego, L.; Nuti, M. Microbial pesticides: Challenges and future perspectives for non-target organism testing. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2024, 36, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wend, K.; Zorrilla, L.; Freimoser, F.M.; Gallet, A. Microbial pesticides-challenges and future perspectives for testing and safety assessment with respect to human health. Environ. Health 2024, 23, 49. [Google Scholar]

- Sandeep Kumar, J.; Jayaraj, J.; Shanthi, M.; Theradimani, M.; Venkatasamy, B.; Irulandi, S.; Prabhu, S. Potential of standard strains of Bacillus thuringiensis against the tomato pinworm, Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae). Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control. 2020, 30, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jallow, M.F.A.; Dahab, A.A.; Albaho, M.S.; Devi, V.Y. Efficacy of Nesidiocoris tenuis (Hemiptera: Miridae) and Bacillus thuringiensis (Berliner) for controlling Tuta absoluta (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) in greenhouse tomato crops under Kuwait hot desert climate. Int. J. Pest Manag. 2022, 70, 1149–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.F.; Zhang, Y.B.; Zhang, J.; Liu, W.X.; Wang, Y.S.; Wan, F.H.; Shu, C.L.; Liu, H.; Wang, F.L.; Zhao, L.; et al. Laboratory toxicity and field control efficacy of biopesticide Bacillus thuringiensis G033A on the South American tomato leafminer Tuta absoluta (Meyrick), a new invasive alien species in China. Chin. J. Biol. 2020, 36, 175–183. [Google Scholar]

- Tayier, A.; Wumuerhan, P.; Ma, Z.; Wang, H.Q.; Lu, Y.; Fu, W.J.; Liu, F.; Wusiman, B.; Ma, D.Y. Evaluation of the control effect of Bt-G033A mixed with 3 insect growth regulators on Tuta absoluta Meyrick. Chin. J. Biol. 2024, 40, 770–775. [Google Scholar]

- Eski, A.; Erdoğan, P.; Demirbağ, Z.; Demir, İ. Isolation and identification of bacteria from the invasive pest Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) and evaluation of their biocontrol potential. Int. Microbiol. 2024, 27, 631–643. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- González-Cabrera, J.; Mollá, O.; Montón, H.; Urbaneja, A. Efficacy of Bacillus thuringiensis (Berliner) in controlling the tomato borer, Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae). BioControl 2011, 56, 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, A.C.; Wanderley-Teixeira, V.; Silva, C.T.; Teixeira, Á.A.; Siqueira, H.A.; Cruz, G.S.; Neto, C.J.C.L.; Lima, A.L.; Correia, M.T. Labeling membrane receptors with lectins and evaluation of the midgut histochemistry of Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) populations with different levels of susceptibility to formulated Bt. Pest Manag. Sci. 2018, 74, 2608–2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selale, H.; Dağlı, F.; Mutlu, N.; Doğanlar, S.; Frary, A. Cry1Ac-mediated resistance to tomato leaf miner (Tuta absoluta) in tomato. Plant Cell Tissue Org. 2017, 131, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.Q.; Zhou, W.W.; Ren, Y.F.; Zhang, J.Y.; Liu, X.L.; Ding, N. A type of Serratia marcescens and Its Application in the Green Control of Tuta absoluta. CN118638666A, 13 September 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y.H.; Wang, W.Q.; Du, G.Z.; Shen, Y.F.; Meng, J.Z.; Xiao, W.X.; Chen, B. Structure, diversity and function prediction of intestinal tract bacterial composition of Paralipsa gularis (Zeller) a new maize pest. J. South. Agric. 2024, 55, 355–365. [Google Scholar]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. HISAT: A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertea, M.; Pertea, G.M.; Antonescu, C.M.; Chang, T.C.; Mendell, J.T.; Salzberg, S.L. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapnell, C.; Williams, B.A.; Pertea, G.; Mortazavi, A.; Kwan, G.; van Baren, M.J.; Salzberg, S.L.; Wold, B.J.; Pachter, L. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010, 28, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, E.P.V.; da Silva Felipe, S.M.; de Freitas, R.M.; da Cruz Freire, J.E.; Oliveira, A.E.R.; Canabrava, N.; Soares, P.M.; van Tilburg, M.F.; Guedes, M.I.F.; Grueter, C.E.; et al. Transcriptional Profiling of SARS-CoV-2-Infected Calu-3 Cells Reveals Immune-Related Signaling Pathways. Pathogens 2023, 12, 1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashburner, M.; Ball, C.A.; Blake, J.A.; Botstein, D.; Butler, H.; Cherry, J.M.; Davis, A.P.; Dolinski, K.; Dwight, S.S.; Eppig, J.T. Gene ontology: Tool for the unification of biology. Nat. Genet. 2000, 25, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S.; Kawashima, S.; Okuno, Y.; Hattori, M. The KEGG resource for deciphering the genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, D277–D280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Wang, L.G.; Han, Y.; He, Q.Y. ClusterProfiler: An R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. Omics 2012, 16, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M.D.; Wakefield, M.J.; Smyth, G.K.; Oshlack, A. Gene ontology analysis for RNA-seq: Accounting for selection bias. Genome Biol. 2010, 11, R14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Cai, T.; Olyarchuk, J.G.; Wei, L. Automated genome annotation and pathway identification using the KEGG Orthology (KO) as a controlled vocabulary. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, 3787–3793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaffl, M.W. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001, 29, e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.C.; Mu, T.; Feng, X.F.; Yu, B.J.; Zhang, J.; Gu, Y.L. Identification of key candidate genes for milk fat metabolism in dairy cows based on transcriptome sequencing. Acta Vet. Et Zootech. Sin. 2022, 53, 3421–3433. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, C.W.; Liu, G.F.; Wang, Z.Y.; Yan, S.C.; Ma, L.; Yang, C.P. Response of the gypsy moth, Lymantria dispar to transgenic poplar, Populus simonii × P. nigra, expressing fusion protein gene of the spider insecticidal peptide and Bt-toxin C-peptide. J. Insect Sci. 2010, 10, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Shi, R.R.; Xu, P.D.; Huang, W.; Liu, C.Q.; Wang, J.; Shu, C.L.; Zhang, J.; Geng, L.L. A Novel Vpb4 Gene and Its Mutants Exhibiting High Insecticidal Activity Against the Monolepta hieroglyphica. Toxins 2025, 17, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, B.; Lv, C.; Li, W.; Li, C.; Chen, T. Virulence of entomopathogenic bacteria Serratia marcescens against the red palm weevil, Rhynchophorus ferrugineus (Olivier). PeerJ 2023, 11, e16528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honger, J.; Monson, R.E.; Rawlinson, A.; Salmond, G.P.C. Draft genome sequences of Serratia marcescens strains CAPREx SY13 and CAPREx SY21 isolated from yams. Genome Announc. 2017, 5, e00191-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, L.M.; Tisa, L.S. Friend or foe? A review of the mechanisms that drive Serratia towards diverse lifestyles. Can. J. Microbiol. 2013, 59, 627–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, R.; Qi, X.; Feng, K.; Xia, X.; Tang, F. Identification and characteristics of a strain of Serratia marcescens isolated from the termites, Odontotermes formosanus. J. Nanjing For. Univ. 2019, 43, 76. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, W.; Zheng, R.; Liao, Y.; Kuang, F.; Yang, Z.; Chen, T.; Zhang, N. Evaluating the biological potential of prodigiosin from Serratia marcescens KH-001 against Asian citrus psyllid. J. Econ. Entomol. 2021, 114, 1219–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devi, S.; Saini, H.S.; Kaur, S. Assessing the pathogenicity of gut bacteria associated with tobacco caterpillar Spodoptera litura (Fab.). Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 8257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohan, M.; Selvakumar, G.; Sushil, S.N.; Chandra Bhatt, J.; Shankar Gupta, H. Entomopathogenicity of endophytic Serratia marcescens strain SRM against larvae of Helicoverpa armigera (Noctuidae: Lepidoptera). World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 27, 2545–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.J.; Zhou, J.X.; Ali, A.; Fu, H.Y.; Gao, S.J.; Jin, L.; Fang, Y.; Wang, J.D. Biocontrol efficiency and characterization of insecticidal protein from sugarcane endophytic Serratia marcescens (SM) against oriental armyworm Mythimna separata (Walker). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 262, 129978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Cheng, Y.X.; Guo, L.B.; Wang, A.L.; Lu, M.; Xu, L.T. Variation of gut microbiota caused by an imbalance diet is detrimental to bugs’ survival. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 771, 144880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, A.; Wang, T.; Pang, F.; Zheng, X.; Ayra-Pardo, C.; Huang, S.; Xu, R.; Liu, F.; Li, J.; Wei, Y.; et al. Characterization of a novel chitinolytic Serratia marcescens strain TC-1 with broad insecticidal spectrum. AMB Express 2022, 12, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodrík, D.; Bednářová, A.; Zemanová, M.; Krishnan, N. Hormonal regulation of response to oxidative stress in insects-an update. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 25788–25816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Chai, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, Z.; Gao, L.L.; Ma, R. Transcriptome analysis and identification of major detoxification gene families and insecticide targets in Grapholita molesta (Busck)(Lepidoptera: Tortricidae). J. Insect Sci. 2017, 17, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardini, L.; Christian, R.N.; Coetzer, N.; Ranson, H.; Coetzee, M.; Koekemoer, L.L. Detoxification enzymes associated with insecticide resistance in laboratory strains of Anopheles arabiensis of different geographic origin. Parasite. Vector. 2012, 5, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braglia, C.; Alberoni, D.; Garrido, P.M.; Porrini, M.P.; Baffoni, L.; Scott, D.; Eguaras, M.J.; Di Gioia, D.; Mifsud, D. Vairimorpha (Nosema) ceranae can promote Serratia development in honeybee gut: An underrated threat for bees? Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1323157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raymann, K.; Coon, K.L.; Shaffer, Z.; Salisbury, S.; Moran, N.A. Pathogenicity of Serratia marcescens strains in honey bees. MBio 2018, 9, e01649-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, T.; Rescigno, M. Host-bacteria interactions in the intestine: Homeostasis to chronic inflammation. Wires. Syst. Biol. Med. 2010, 2, 80–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baur, M.; Schulz, N.K.E.; Greune, L.; Länger, Z.M.; Eirich, J.; Finkemeier, I.; Peuß, R.; Dersch, P.; Kurtz, J. Immune priming in the insect gut: A dynamic response revealed by ultrastructural and transcriptomic changes. BMC Biol. 2025, 23, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhang, K.; Yin, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Kong, X.; Tang, L.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, Z. Serratia marcescens in the intestine of housefly larvae inhibits host growth by interfering with gut microbiota. Parasite. Vector. 2023, 16, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, C.; Sharma, S.; Meghwanshi, K.K.; Patel, S.; Mehta, P.; Shukla, N.; Do, D.N.; Rajpurohit, S.; Suravajhala, P.; Shukla, J.N. Long non-coding RNAs in insects. Animals 2021, 11, 1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graveley, B.R.; Brooks, A.N.; Carlson, J.W.; Duff, M.O.; Landolin, J.M.; Yang, L.; Artieri, C.G.; Van Baren, M.J.; Boley, N.; Booth, B.W. The developmental transcriptome of Drosophila melanogaster. Nature 2011, 471, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, T.; He, W.; Shen, X.; Zhao, Q.; Bai, J.; You, M. Genome-wide identification and characterization of putative lncRNAs in the Diamondback moth. Plutella xylostella (L.). Genomics 2018, 110, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.J.; Song, Y.J.; Han, H.L.; Xu, H.Q.; Wei, D.; Smagghe, G.; Wang, J.J. Genome-wide analysis of long non-coding RNAs in adult tissues of the melon fly, Zeugodacus cucurbitae (Coquillett). BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, S.J.; Zhang, Q.C.; Liu, C.X.; Shen, H. Transcriptome of Musca domestica (Diptera: Muscidae) larvae induced by bacteria. J. Entomol. Sci. 2024, 59, 66–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Zhang, C.; Yang, H.; Ding, B.; Yang, H.Z.; Zhang, S.W. Characterization and functional analysis of toll receptor genes during antibacterial immunity in the green peach aphid Myzus persicae (Sulzer). Insects 2023, 14, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, P.; Mei, X.; Li, R.; Xu, Y.; Qiu, Z.; Xia, D.; Zhao, Q.L.; Shen, D.X. Transcriptome analysis of immune-related genes of Asian corn borer (Ostrinia furnacalis [Guenée]) after oral bacterial infection. Arch. Insect Biochem. 2023, 114, e22044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Wang, Z.; Tang, F.; Feng, K. Immune Defense Mechanism of Reticulitermes chinensis Snyder (Blattodea: Isoptera) against Serratia marcescens Bizio. Insects 2022, 13, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsakas, S.; Marmaras, V.J. Insect immunity and its signaling: An overview. Invertebr. Surviv. J. 2010, 7, 228–238. [Google Scholar]

- Darby, A.M.; Keith, S.A.; Kalukin, A.A.; Lazzaro, B.P. Chronic bacterial infections exert metabolic costs in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Exp. Biol. 2025, 228, jeb249424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, R.; Lee, B.; Grewal, S.S. Enteric bacterial infection in Drosophila induces whole-body alterations in metabolic gene expression independently of the immune deficiency signaling pathway. G3 2022, 12, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartling, M.T.; Thumecke, S.; Russert, J.H.; Vilcinskas, A.; Lee, K.Z. Exposure to low doses of pesticides induces an immune response and the production of nitric oxide in honeybees. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 6819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pasquale, G.; Salignon, M.; Le Conte, Y.; Belzunces, L.P.; Decourtye, A.; Kretzschmar, A.; Suchail, S.; Brunet, J.L.; Alaux, C. Influence of pollen nutrition on honey bee health: Do pollen quality and diversity matter? PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e72016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiotsuki, T.; Kato, Y. Induction of carboxylesterase isozymes in Bombyx mori by E. coli infection. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1999, 29, 731–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, K.; Luo, J.; Ding, X.; Tang, F. Transcriptome analysis and response of three important detoxifying enzymes to Serratia marcescens Bizio (SM1) in Hyphantria cunea (Drury) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Pest Biochem. Physiol. 2021, 178, 104922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Schuler, M.A.; Berenbaum, M.R. Molecular mechanisms of metabolic resistance to synthetic and natural xenobiotics. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2007, 52, 231–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, K.; Song, Y.; Zeng, R. The role of cytochrome P450-mediated detoxification in insect adaptation to xenobiotics. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2021, 43, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, X.; Bai, R.; Shi, Y.; Tang, Q.; An, S.; Song, Q.; Yan, F. RNA interference of the P450 CYP6CM1 gene has different efficacy in B and Q biotypes of Bemisia tabaci. Pest Manag. Sci. 2015, 71, 1175–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Dong, J.; Wu, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Ma, E. Knockdown of cytochrome P450 CYP6 family genes increases susceptibility to carbamates and pyrethroids in the migratory locust, Locusta migratoria. Chemosphere 2019, 223, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, L.; Williams, D.R.; Aguiar-Santana, I.A.; Pedersen, J.; Turner, P.C.; Rees, H.H. Expression and down-regulation of cytochrome P450 genes of the CYP4 family by ecdysteroid agonists in Spodoptera littoralis and Drosophila melanogaster. Insect Biochem. Molec. 2006, 36, 801–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranson, H.; Nikou, D.; Hutchinson, M.; Wang, X.; Roth, C.; Hemingway, J.; Collins, F. Molecular analysis of multiple cytochrome P450 genes from the malaria vector, Anopheles gambiae. Insect Mol. Biol. 2002, 11, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Sheng, C.; Li, M.; Wan, H.; Liu, D.; Qiu, X. Expression responses of nine cytochrome P450 genes to xenobiotics in the cotton bollworm Helicoverpa armigera. Pestic. Biochem. Phys. 2010, 97, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strain | Colony Color 1 | Colony Size 2 | Surface Texture 3 | Colony Margin 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tapa02 (Figure 1A) | Cream | Medium | Rough | Undulate |

| Tapa12 (Figure 1B) | Pale white | Small | Smooth | Entire |

| Tapa13 (Figure 1C) | White | Small | Rough | Undulate |

| Tapa21 (Figure 1D) | Red | Medium | Smooth | Entire |

| χ2 Value 1 | LC50/LT50 2 | Toxicity Regression Equation | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2.65 (3) | LC50 = OD600 = 0.52 (0.33–0.65) | Y = 0.86X − 0.45 | 0.94 |

| 12.83 (5) | LT50 = 5.29 days (4.64–6.18) | Y = 0.38X − 2.01 | 0.91 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Basit, A.; Cai, X.; Shang, L.; Wang, Z.; Li, B.; Li, X.; Zhao, Y.; Hou, Y. Detoxification Responses of Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) to Serratia marcescens (Bizio) Strain Tapa21 Infection Revealed by Transcriptomics. Agriculture 2026, 16, 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010048

Wang Y, Basit A, Cai X, Shang L, Wang Z, Li B, Li X, Zhao Y, Hou Y. Detoxification Responses of Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) to Serratia marcescens (Bizio) Strain Tapa21 Infection Revealed by Transcriptomics. Agriculture. 2026; 16(1):48. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010048

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yuzhou, Abdul Basit, Xiangyun Cai, Luohua Shang, Zhujun Wang, Baiting Li, Xiujie Li, Yan Zhao, and Youming Hou. 2026. "Detoxification Responses of Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) to Serratia marcescens (Bizio) Strain Tapa21 Infection Revealed by Transcriptomics" Agriculture 16, no. 1: 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010048

APA StyleWang, Y., Basit, A., Cai, X., Shang, L., Wang, Z., Li, B., Li, X., Zhao, Y., & Hou, Y. (2026). Detoxification Responses of Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) to Serratia marcescens (Bizio) Strain Tapa21 Infection Revealed by Transcriptomics. Agriculture, 16(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010048