Are Rural Residents Willing to Pay for Sanitation Improvements? Evidence from China’s Toilet Revolution

Abstract

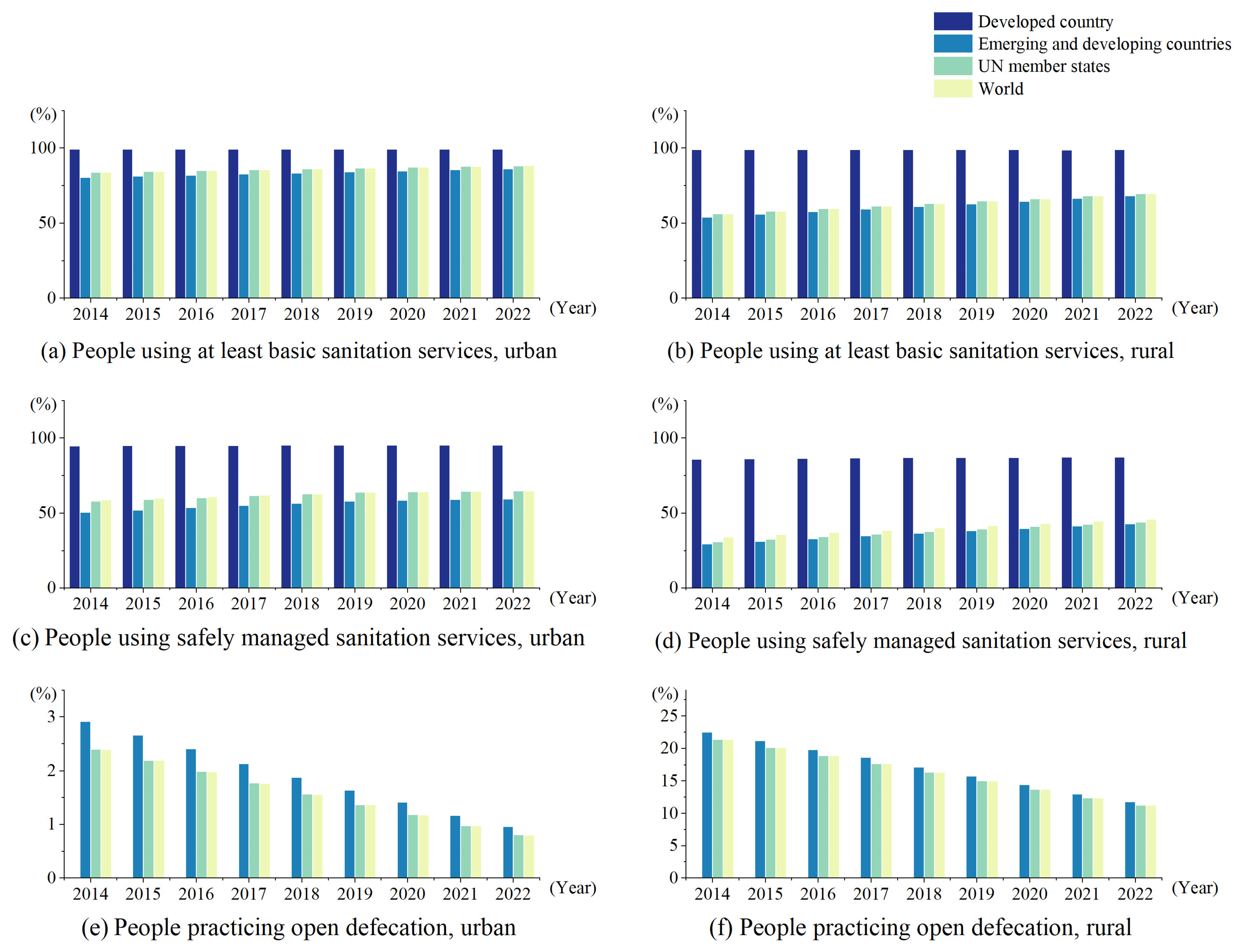

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Rural Living Environments

2.2. Rural Toilet Revolution

2.3. Willingness to Pay

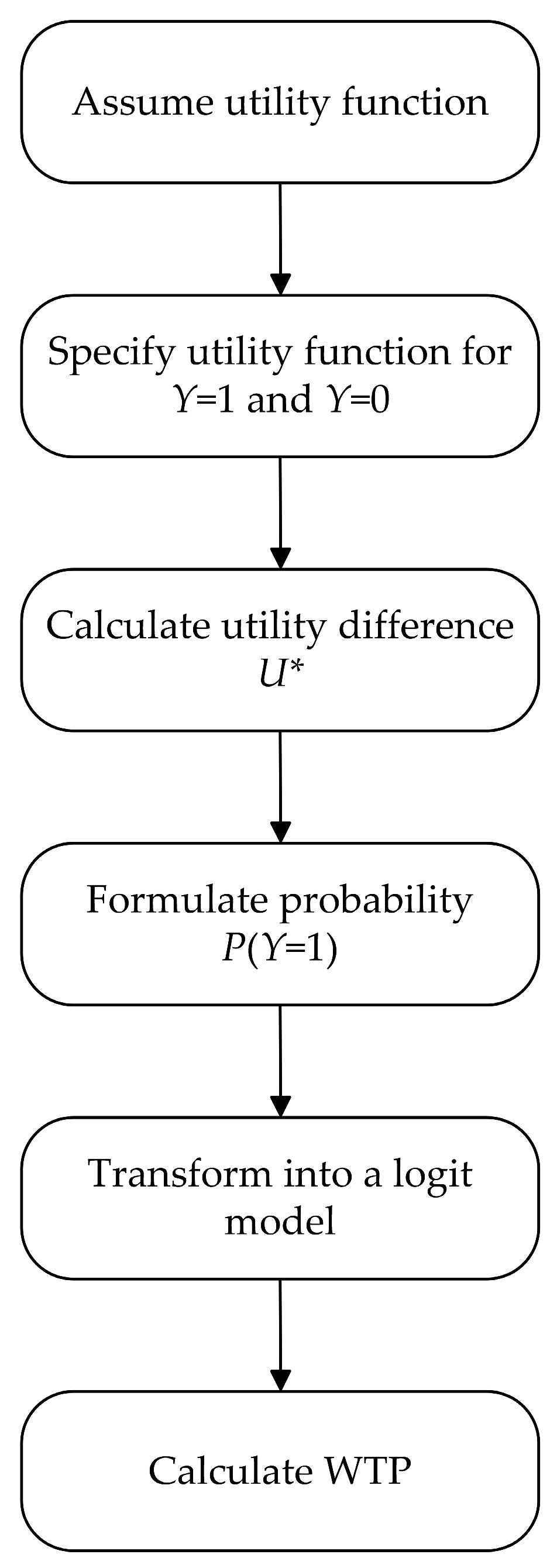

3. Theory

4. Material and Methods

4.1. Research Design

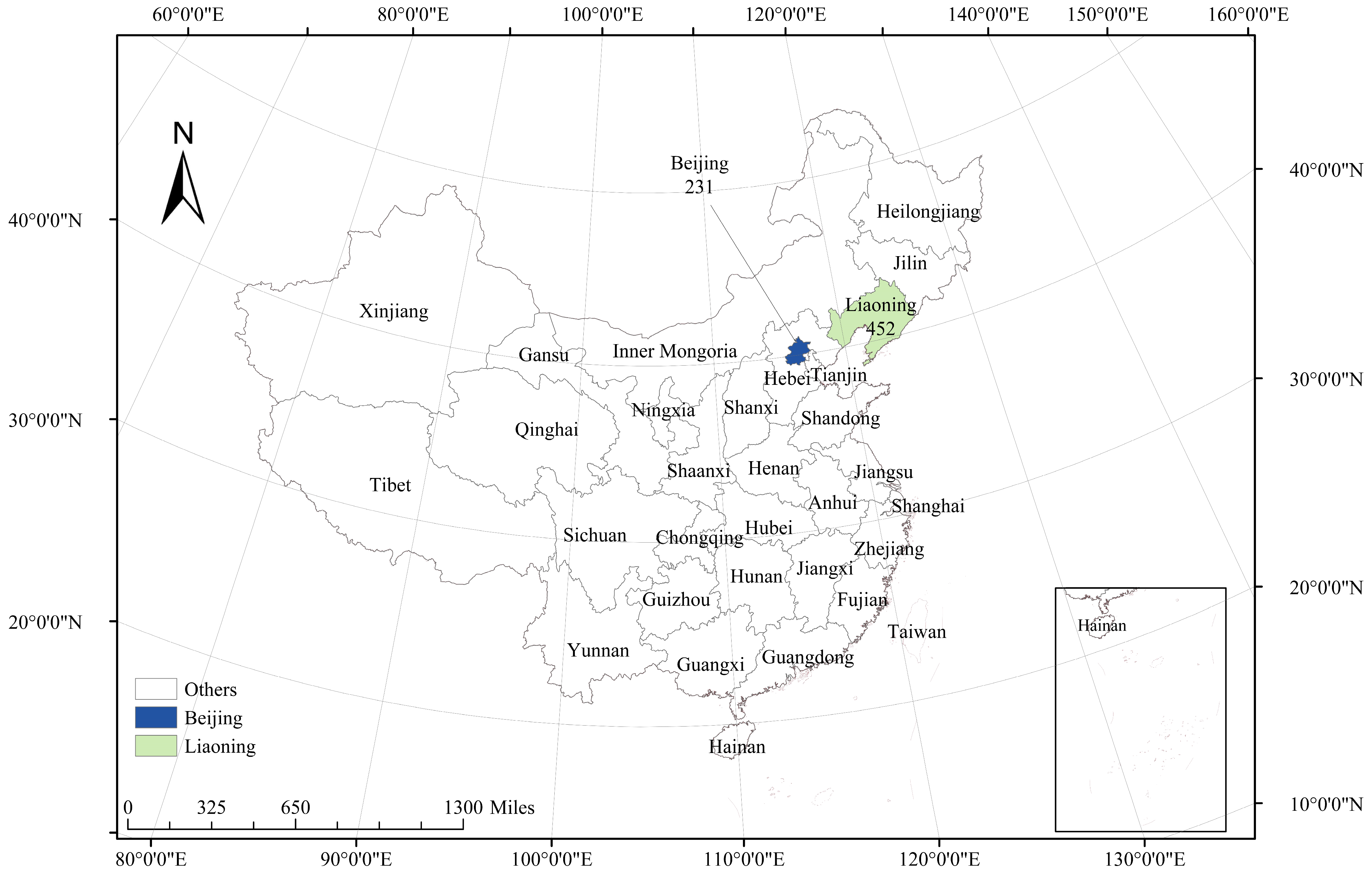

4.2. Data Source

4.3. Variable Selection

4.4. Modeling

5. Results

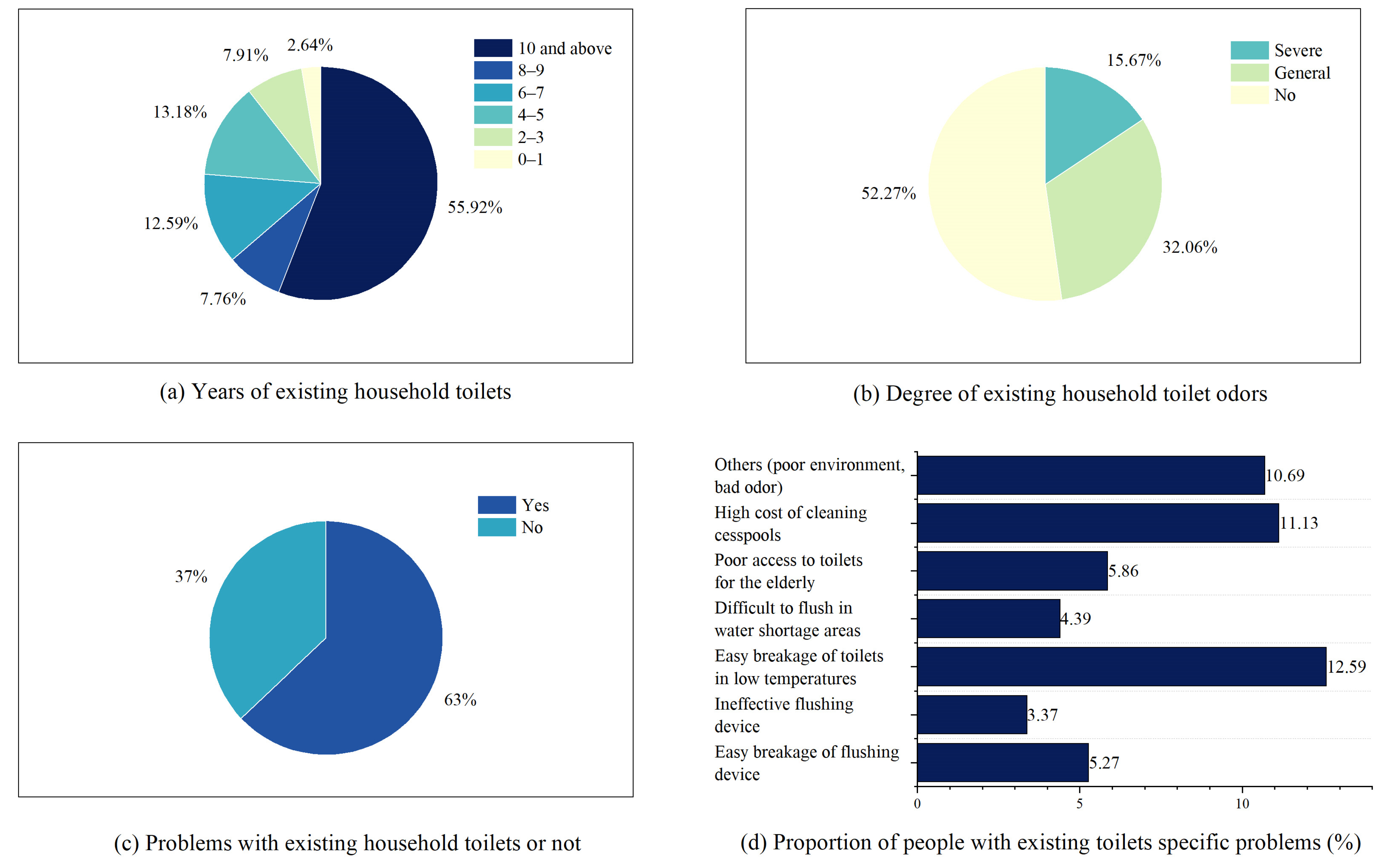

5.1. Usage of Rural Toilets

5.2. Rural Residents’ Willingness to Renovate Sanitary Toilets

5.3. Average Willingness to Pay of Rural Residents for Sanitary Toilet Renovation

5.4. Comparison of Willingness to Pay Among Different Rural Residents

6. Discussion

7. Conclusion and Policy Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- World Health Organization; United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Progress on Household Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene 2000–2020: Five Years into the SDGs; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fewtrell, L.; World Health Organization. Water, Sanitation and Hygiene: Quantifying the Health Impact at National and Local Levels in Countries with Incomplete Water Supply and Sanitation Coverage; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization; United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Progress on Sanitation and Drinking Water—2015 Update and MDG Assessment; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Prüss-Ustün, A.; Bartram, J.; Clasen, T.; Colford, J.M.; Cumming, O.; Curtis, V.; Bonjour, S.; Dangour, A.D.; De France, J.; Fewtrell, L.; et al. Burden of Disease from Inadequate Water, Sanitation and Hygiene in Low- and Middle-income Settings: A Retrospective Analysis of Data from 145 Countries. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2014, 19, 894–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschi-Pinto, C. Estimating Child Mortality Due to Diarrhoea in Developing Countries. Bull. World Health Organ. 2008, 86, 710–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) (Ed.) Children in an Urban World. In The State of the World’s Children; United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF): New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, J.; Mcphedran, K. A Literature Review of the Non-Health Impacts of Sanitation. Waterlines 2008, 27, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Sun, F.; Yang, J.; Li, J.; Liang, J.; Yang, M.; Liu, W. Situation and Treatment Methods of Ecological and Environmental Problems during the Process of Urbanization in Rural Areas of China. Nat. Environ. Pollut. Technol. 2021, 20, 1781–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutton, G. Global Costs and Benefits of Reaching Universal Coverage of Sanitation and Drinking-Water Supply. J. Water Health 2013, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duflo, E.; Greenstone, M.; Guiteras, R.; Clasen, T. Toilets Can Work: Short and Medium Run Health Impacts of Addressing Complementarities and Externalities in Water and Sanitation; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, W.-P. Seven Trials, Seven Question Marks. Lancet Glob. Health 2015, 3, e659–e660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, J.E.; Cumming, O. The Impact of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene on Key Health and Social Outcomes; Sanitation and Hygiene Applied Research for Equity (SHARE) and UNICEF: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF); World Health Organization. State of the World’s Sanitation: An Urgent Call to Transform Sanitation for Better Health, Environments, Economies and Societies: Summary Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Klarin, T. The Concept of Sustainable Development: From Its Beginning to the Contemporary Issues. Zagreb Int. Rev. Econ. Bus. 2018, 21, 67–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manioudis, M.; Meramveliotakis, G. Broad Strokes towards a Grand Theory in the Analysis of Sustainable Development: A Return to the Classical Political Economy. New Political Econ. 2022, 27, 866–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Population Having Neither a Bath, nor a Shower, nor Indoor Flushing Toilet in Their Household by Poverty Status. Eurostat Database [Dataset] 2022. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/product/page/SDG_06_10 (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Li, Y.; Cheng, S.; Chen, X.; Gao, M.; Chen, C.; Huba, E.-M.; Li, Z.; Crittenden, J.; Li, T. What Makes Residents Participate in the Rural Toilet Revolution? Environ. Sci. Ecotechnol. 2024, 19, 100343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhang, H. Do You Live Happily? Exploring the Impact of Physical Environment on Residents’ Sense of Happiness. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2018, 112, 012012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; He, D.; Kuang, T.; Chen, K. Effect of Rural Human Settlement Environment around Nature Reserves on Farmers’ Well-Being: A Field Survey Based on 1002 Farmer Households around Six Nature Reserves in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimutai, J.J.; Lund, C.; Moturi, W.N.; Shewangizaw, S.; Feyasa, M.; Hanlon, C. Evidence on the Links between Water Insecurity, Inadequate Sanitation and Mental Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0286146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Solangi, Y.A. Analyzing the Relationship between Natural Resource Management, Environmental Protection, and Agricultural Economics for Sustainable Development in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 450, 141862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Tan, L.; Zhang, C.; Li, Q.; Wei, X.; Yang, B.; Chen, P.; Zheng, X.; Xu, Y. Assessment of Environmental and Social Effects of Rural Toilet Retrofitting on a Regional Scale in China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 812727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhou, X.; Simha, P. Leveraging a Sanitation Value Chain Framework Could Address Implementation Challenges and Reinvent China’s Toilet Revolution in Rural Areas. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1390101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, M. Public Finance at Scale for Rural Sanitation—A Case of Swachh Bharat Mission, India. J. Water Sanit. Hyg. Dev. 2018, 8, 359–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harter, M.; Inauen, J.; Mosler, H.-J. How Does Community-Led Total Sanitation (CLTS) Promote Latrine Construction, and Can It Be Improved? A Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial in Ghana. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 245, 112705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Li, Z.; Uddin, S.M.N.; Mang, H.-P.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, L.; Zhang, L. Toilet Revolution in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 216, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cheng, S.; Li, Z.; Song, H.; Guo, M.; Li, Z.; Mang, H.-P.; Xu, Y.; Chen, C.; Basandorj, D.; et al. Using System Dynamics to Assess the Complexity of Rural Toilet Retrofitting: Case Study in Eastern China. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 280, 111655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Simha, P.; Perez-Mercado, L.F.; Barton, M.A.; Lyu, Y.; Guo, S.; Nie, X.; Wu, F.; Li, Z. China Should Focus beyond Access to Toilets to Tap into the Full Potential of Its Rural Toilet Revolution. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 178, 106100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Zhou, X.; Simha, P.; Mercado, L.F.P.; Lv, Y.; Li, Z. Poor Awareness and Attitudes to Sanitation Servicing Can Impede China’s Rural Toilet Revolution: Evidence from Western China. Sci. Total. Environ. 2021, 794, 148660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Jin, F.; Zhu, Y. The Impact of Access to Sanitary Toilets on Rural Adult Residents’ Health: Evidence from the China Family Panel Survey. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1026714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Zhou, W.; Zheng, T.; Huang, F. Health Effects and Externalities of the Popularization of Sanitary Toilets: Evidence from Rural China. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Yang, F.-X.; Fan, D.-S.; Yang, Z.-N. The Spatial Effects of Rural Toilet Retrofitting Investment on Farmers’ Medical and Health Expenditure in China. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1135362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Shen, Y. Sanitation and Work Time: Evidence from the Toilet Revolution in Rural China. World Dev. 2022, 158, 105992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.; Yang, Z.; Zhou, H. Study on Rural Residents’ Willingness to Pay for Environmental Sanitation Improvement and the Factors Influencing It—Taking the Example of Toilet Renovation. J. Manag. World 2012, 89–99. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzby, J.C.; Skees, J.R.; Ready, R.C. Using Contingent Valuation to Value Food Safety: A Case Study of Grapefruit and Pesticide Residues. In Valuing Food Safety and Nutrition; Routledge: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Boccaletti, S.; Nardella, M. Consumer Willingness to Pay for Pesticide-Free Fresh Fruit and Vegetables in Italy. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2000, 3, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanayo, O.; Ezebuilo, U.; Maurice, O. Estimating the Willingness to Pay for Water Services in Nsukka Area of South-Eastern Nigeria Using Contingent Valuation Method (CVM): Implications for Sustainable Development. J. Hum. Ecol. 2013, 41, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuhmann, P.W.; Bangwayo-Skeete, P.; Skeete, R.; Seaman, A.N.; Barnes, D.C. Visitors’ Willingness to Pay for Ecosystem Conservation in Grenada. J. Sustain. Tour. 2024, 32, 1644–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spash, C.L. Non-Economic Motivation for Contingent Values: Rights and Attitudinal Beliefs in the Willingness To Pay for Environmental Improvements. Land Econ. 2006, 82, 602–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.C.; Roberts, J.A.; Barreto, M.L.; Cairncross, S. Demand for Sanitation in Salvador, Brazil: A Hybrid Choice Approach. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 72, 1325–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, K.; Kong, F.; Zhang, N.; Lei, N.; Sun, C. Analysis of the Factors Influencing Willingness to Pay and Payout Level for Ecological Environment Improvement of the Ganjiang River Basin. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Han, Y.; Qiao, X.-J.; Randrup, T.B. Citizen Willingness to Pay for the Implementation of Urban Green Infrastructure in the Pilot Sponge Cities in China. Forests 2023, 14, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ran, B. Network Governance and Collaborative Governance: A Thematic Analysis on Their Similarities, Differences, and Entanglements. Public Manag. Rev. 2023, 25, 1187–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodin, Ö. Collaborative Environmental Governance: Achieving Collective Action in Social-Ecological Systems. Science 2017, 357, eaan1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Tang, Y.; Xue, S.; Zhang, K. Study on Cooperative Strategies of Rural Water Environment Governance PPP Project between Companies and Farmers from the Perspective of Evolutionary Game. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 138–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Liu, N. Research on Citizen Participation in Government Ecological Environment Governance Based on the Research Perspective of “Dual Carbon Target”. J. Environ. Public Health 2022, 2022, 5062620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyim, P. Tourism Collaborative Governance and Rural Community Development in Finland: The Case of Vuonislahti. J. Travel Res. 2017, 57, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopmans, M.E.; Rogge, E.; Mettepenningen, E.; Knickel, K.; Šūmane, S. The Role of Multi-Actor Governance in Aligning Farm Modernization and Sustainable Rural Development. J. Rural Stud. 2018, 59, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bani, B.K.; Damnyag, L. Farmers’ Willingness to Pay for the Provision of Ecosystem Services to Enhance Agricultural Production in Sene East District, Ghana. Small-Scale For. 2017, 16, 451–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olum, S.; Gellynck, X.; Juvinal, J.; Ongeng, D.; De Steur, H. Farmers’ Adoption of Agricultural Innovations: A Systematic Review on Willingness to Pay Studies. Outlook Agric. 2020, 49, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Zhang, Y.; He, B.-J. Public Willingness to Pay for and Participate in Sanitation Infrastructure Improvement in Western China’s Rural Areas. Front. Public Health 2022, 9, 788922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Nan, Z.; Liu, J. The Willingness to Pay for Irrigation Water: A Case Study in Northwest China. Glob. NEST J. 2013, 15, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahad, S.; Jing, W. Evaluation of Pakistani Farmers’ Willingness to Pay for Crop Insurance Using Contingent Valuation Method: The Case of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province. Land Use Policy 2018, 72, 570–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P.; Tang, H.; Zhu, S.; Jiang, P.; Wang, J.; Kong, X.; Liu, K. Distance to River Basin Affects Residents’ Willingness to Pay for Ecosystem Services: Evidence from the Xijiang River Basin in China. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 126, 107691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchio, R.; Annunziata, A.; Parga Dans, E.; Alonso González, P. Drivers of Consumer Willingness to Pay for Sustainable Wines: Natural, Biodynamic, and Organic. Org. Agric. 2023, 13, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickerstaff, K. Risk Perception Research: Socio-Cultural Perspectives on the Public Experience of Air Pollution. Environ. Int. 2004, 30, 827–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wang, S.; Yu, Y. Consumer’s Intention to Purchase Green Furniture: Do Health Consciousness and Environmental Awareness Matter? Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 704, 135275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Janvry, A.D.; Sadoulet, E. Social Networks and the Decision to Insure. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 2015, 7, 81–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, M.; Zhao, Z.-Y.; Li, H.; Rehman, A. The Influence of Consumers’ Intention Factors on Willingness to Pay for Renewable Energy: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 21747–21761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemu, M.H.; Olsen, S.B. An Analysis of the Impacts of Tasting Experience and Peer Effects on Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Novel Foods. Agribusiness 2020, 36, 653–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Li, H.; Li, Q.; Mi, L. Assessing Willingness to Pay for Upgrading Toilets in Rural Areas of Shaanxi and Inner Mongolia, China. Desalination Water Treat. 2019, 156, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ding, X.; Li, D.; Li, S. The Impact of Organizational Support, Environmental Health Literacy on Farmers’ Willingness to Participate in Rural Living Environment Improvement in China: Exploratory Analysis Based on a PLS-SEM Model. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Qiu, M.; Zhou, M. Correlation between General Health Knowledge and Sanitation Improvements: Evidence from Rural China. npj Clean Water 2021, 4, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, J.M.; Bianchi, E.C.; Sánchez, C. Determinants of Household Recycling Intention: The Acceptance of Public Policy Moderated by Habits, Social Influence, and Perceived Time Risk. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 136, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; van den Brink, H.M.; Groot, W. College Education and Social Trust: An Evidence-Based Study on the Causal Mechanisms. Soc. Indic. Res. 2011, 104, 287–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, Z.; Sun, D.; Liu, G. Residents’ Willingness to Pay for Water Pollution Treatment and Its Influencing Factors: A Case Study of Taihu Lake Basin. Environ. Manag. 2024, 74, 490–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrnes, J.P.; Miller, D.C.; Schafer, W.D. Gender Differences in Risk Taking: A Meta-Analysis. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 125, 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.; Tian, Z.; Fan, M. Do the Rich Have Stronger Willingness to Pay for Environmental Protection? New Evidence from a Survey in China. World Dev. 2018, 105, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saari, U.A.; Damberg, S.; Frömbling, L.; Ringle, C.M. Sustainable Consumption Behavior of Europeans: The Influence of Environmental Knowledge and Risk Perception on Environmental Concern and Behavioral Intention. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 189, 107155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yang, B.; Sun, C. Can Payment Vehicle Influence Public Willingness to Pay for Environmental Pollution Control? Evidence from the CVM Survey and PSM Method of China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 365, 132648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Zeng, D.; Li, Q.; Cheng, C.; Shi, G.; Mou, Z. Public Willingness to Pay and Participate in Domestic Waste Management in Rural Areas of China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 140, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, K.; Xu, D.; Qi, Y.; Deng, X. Do Clean Toilets Help Improve Farmers’ Mental Health? Empirical Evidence from China’s Rural Toilet Revolution. Agriculture 2024, 14, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, V. Explaining the Outcomes of the “Clean India” Campaign: Institutional Behaviour and Sanitation Transformation in India. BMJ Glob. Health 2019, 4, e001892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutton, G.; Patil, S.; Kumar, A.; Osbert, N.; Odhiambo, F. Comparison of the Costs and Benefits of the Clean India Mission. World Dev. 2020, 134, 105052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, S.; Gune, S.; Bruckner, T.A.; Strominger, J.; Singh, P. Toilet Construction Under the Swachh Bharat Mission and Infant Mortality in India. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 20340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VerKuilen, A.; Sprouse, L.; Beardsley, R.; Lebu, S.; Salzberg, A.; Manga, M. Effectiveness of the Swachh Bharat Mission and Barriers to Ending Open Defecation in India: A Systematic Review. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1141825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novotný, J.; Borde, R.; Ficek, F.; Kumar, A. The Process, Outcomes and Context of the Sanitation Change Induced by the Swachh Bharat Mission in Rural Jharkhand, India. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanyangarara, M.; Allen, S.; Jiwani, S.S.; Fuente, D. Access to Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Services in Health Facilities in Sub-Saharan Africa 2013–2018: Results of Health Facility Surveys and Implications for COVID-19 Transmission. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, C.M.M.; Rosa, L.P.; Gomez, J.M.A.; D’Avignon, A. Achieving the Sustainable Development Goal 06 in Brazil: The Universal Access to Sanitation as a Possible Mission. An. Da Acad. Bras. De Ciências 2018, 90, 1337–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, N.; Budhathoki, S.S.; Lucero-Prisno, D.E.I.; Shrestha, G.; Bhattachan, M.; Thapa, J.; Sunny, A.K.; Upadhyaya, P.; Ghimire, A.; Pokharel, P.K. What Motivates Open Defecation? A Qualitative Study from a Rural Setting in Nepal. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0219246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Definition | Number of People | Proportion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Men | 309 | 45.24 |

| Women | 374 | 54.76 | |

| Age | 20–29 | 124 | 18.16 |

| 30–39 | 112 | 16.40 | |

| 40–49 | 187 | 27.38 | |

| 50–59 | 187 | 27.38 | |

| Above 60 | 73 | 10.69 | |

| Education (Educational level) | Below Primary School | 21 | 3.07 |

| Primary School | 54 | 7.91 | |

| Junior High School | 153 | 22.40 | |

| High School/ Middle School/ Vocational High School | 155 | 22.69 | |

| University/College | 281 | 41.14 | |

| Postgraduate and Above | 19 | 2.78 | |

| Income (Monthly household income) | <10,000 | 526 | 77.01 |

| 10,000–19,999 | 120 | 17.57 | |

| ≥20,000 | 37 | 5.42 |

| Variable | Define | Mean | Standard Deviation | Expected Direction of Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bid | Random price | 588.06 | 164.60 | - |

| Sex | 1 = Men, 0 = Women | 0.46 | 0.50 | + |

| Age | Age | 42.60 | 12.64 | + |

| age 1 | 1 = Age 20–29, 0 = Other | |||

| age 2 | 1 = Age 30–39, 0 = Other | |||

| age 3 | 1 = Age 40–49, 0 = Other | |||

| age 4 | 1 = Age 50–59, 0 = Other | |||

| Education | Educational level, 1 = below primary school, 2 = primary school, 3 = junior high school, 4 = high school/middle school/vocational high school, 5 = university/college, 6 = postgraduate and above | 4.18 | 1.06 | + |

| Income | Monthly household income (CNY one thousand) | 12.43 | 92.37 | + |

| income 1 | 1 = Monthly household income less than CNY 10,000, 0 = Other | |||

| income 2 | 1 = Monthly household income is 10,000–19,999 CNY, 0 = Other | |||

| House | Number of people in the household | 4.00 | 1.40 | + |

| Distance | Distance of the household from the city/district center (km) | 3.23 | 1.73 | - |

| Member | Whether the household is the main purchasing member of household necessities, 1 = Yes, 0 = No | 0.70 | 0.46 | + |

| Purchase | Frequency of household purchasing furniture, 1 = Basically not purchase, 2 = Occasionally purchase, 3 = Generally purchase, 4 = Often purchase, 5 = Always purchase | 2.28 | 0.93 | + |

| Familiarity | Knowledge of surrounding environmental sanitation, 1 = Never, 2 = Less, 3 = General, 4 = More, 5 = Very | 3.14 | 1.01 | + |

| Clean | Frequency of toilet cleaning, 1 = Not clean, 2 = Clean once a month, 3 = Clean weekly, 4 = Clean daily | 3.26 | 0.90 | + |

| Health | Perceived relationship between sanitary toilets and health, 1 = Very relevant, 2 = More relevant, 3 = General, 4 = Less relevant, 5 = Not relevant | 1.57 | 0.84 | - |

| Satisfaction | Satisfaction with existing toilet, 1 = Very dissatisfied, 2 = Less satisfied, 3 = General, 4 = More satisfied, 5 = Very satisfied | 3.44 | 1.06 | - |

| Unsanitary | Receptiveness to non-sanitary toilets, 1 = Not acceptable, 2 = Less acceptable, 3 = General, 4 = More acceptable, 5 = Completely acceptable | 2.23 | 1.11 | - |

| Relatives | Proportion of relatives and neighbors using sanitary toilets, 1 = 0–20%, 2 = 21–40%, 3 = 41–60%, 4 = 61–80%, 5 = 81–100% | 2.91 | 1.53 | + |

| Reformation | Weather have participated in a toilet renovation, 1 = Yes, 0 = No | 0.18 | 0.39 | + |

| Variable | Willing to Pay CNY 300 for Toilet Renovation | Unwilling to Pay CNY 300 for Toilet Renovation | Chi-Square Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.46 | 0.44 | 0.0762 |

| Age | 42.60 | 47.04 | 80.3276 ** |

| Education | 4.18 | 3.57 | 48.4058 *** |

| Income | 12.43 | 6.56 | 62.2321 * |

| House | 4.00 | 3.91 | 6.1355 |

| Distance | 3.23 | 3.42 | 10.5045 ** |

| Member | 0.70 | 0.68 | 0.1804 |

| Purchase | 2.28 | 2.21 | 11.0054 ** |

| Familiarity | 3.14 | 3.11 | 3.3761 |

| Clean | 3.26 | 3.22 | 2.6801 |

| Health | 1.57 | 1.89 | 22.9398 *** |

| Satisfaction | 3.44 | 3.51 | 3.2460 |

| Unsanitary | 2.23 | 2.47 | 14.1750 *** |

| Relatives | 2.91 | 2.78 | 6.7853 |

| Reformation | 0.18 | 0.22 | 0.9728 |

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | dy/dx | Coefficient | dy/dx | |

| Intercept | 0.2557 | −0.0193 | ||

| Age | −0.0087 | −0.0017 | ||

| Age 1 | 0.6562 * | 0.1280 * | ||

| Age2 | 0.1086 | 0.0212 | ||

| Age3 | 0.3718 | 0.0725 | ||

| Age4 | 0.3461 | 0.0675 | ||

| Education | 0.3355 *** | 0.0659 *** | 0.2996 *** | 0.0584 *** |

| Income | 0.0062 | 0.0012 | ||

| Income1 | −0.3181 | −0.0620 | ||

| Income2 | 0.0339 | 0.0066 | ||

| Health | −0.2245 ** | −0.0441 ** | −0.2250 ** | −0.0439 ** |

| Number of obs | 683 | 683 | ||

| Wald chi2(16) | 42.34 | 47.7 | ||

| Prob > chi2 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | ||

| Log pseudolikelihood | −395.4366 | −393.1451 | ||

| Variable | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | dy/dx | Coefficient | dy/dx | |

| Intercept | 1.7797 | 1.7585 | ||

| Bid | −0.0056 *** | −0.0009 *** | −0.0057 *** | −0.0009 *** |

| Sex | 0.4002 * | 0.0675 * | 0.4178 * | 0.0687 * |

| Age | 0.0046 | 0.0008 | ||

| Age 1 | −0.7593 | −0.1248 | ||

| Age 2 | −0.0583 | −0.0096 | ||

| Age 3 | −0.5295 | −0.0870 | ||

| Age 4 | −0.5342 | −0.0878 | ||

| Education | 0.2321 * | 0.0392 * | 0.2649 * | 0.0435 * |

| Income | 0.0070 | 0.0012 | ||

| Income 1 | 0.7497 | 0.1232 | ||

| Income 2 | 1.3597 *** | 0.2234 *** | ||

| House | 0.0464 | 0.0078 | 0.0344 | 0.0057 |

| Distance | −0.0492 | −0.0083 | −0.0634 | −0.0104 |

| Member | 0.2740 | 0.0463 | 0.2512 | 0.0413 |

| Purchase | 0.2368 | 0.0400 * | 0.2623 * | 0.0431 * |

| Familiarity | 0.1248 | 0.0211 | 0.1294 | 0.0213 |

| Clean | 0.2410 * | 0.0407 * | 0.2660 * | 0.0437 * |

| Health | −0.1536 | −0.0259 | −0.1490 | −0.0245 |

| Satisfaction | −0.2443 ** | −0.0412 ** | −0.2841 ** | −0.0467 ** |

| Unsanitary | −0.0473 | −0.0080 | −0.0841 | −0.0138 |

| Relatives | 0.0635 | 0.0107 | 0.0570 | 0.0094 |

| Reformation | 1.4249 *** | 0.2405 *** | 1.5844 *** | 0.2603 *** |

| Number of obs | 476 | 476 | ||

| Wald chi2 (16) | 68.09 | 75.38 | ||

| Prob > chi2 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | ||

| Log pseudolikelihood | −240.6871 | −235.6558 | ||

| Variable | Women | Men | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | |||||

| Coefficient | dy/dx | Coefficient | dy/dx | Coefficient | dy/dx | Coefficient | dy/dx | |

| Intercept | 1.3135 | 0.6444 | 3.6423 * | 4.1435 ** | ||||

| Bid | −0.0057 *** | −0.0010 *** | −0.0058 *** | −0.0010 *** | −0.0057 *** | −0.0009 *** | −0.0058 *** | −0.0009 *** |

| Age | 0.0089 | 0.0016 | −0.0029 | −0.0004 | ||||

| Age 1 | −0.7243 | −0.1237 | −0.7181 | −0.1063 | ||||

| Age 2 | 0.0073 | 0.0013 | −0.2263 | −0.0335 | ||||

| Age 3 | −0.6552 | −0.1119 | −0.3006 | −0.0445 | ||||

| Age 4 | −0.4082 | −0.0697 | −0.6756 | −0.1000 | ||||

| Education | 0.3324 * | 0.0598 ** | 0.3564 * | 0.0609 * | −0.0017 | −0.0003 | 0.0784 | 0.0116 |

| Income | 0.0033 | 0.0006 | 0.0170 | 0.0025 | ||||

| Income 1 | 1.4055 * | 0.2401 * | −0.3570 | −0.0528 | ||||

| Income 2 | 2.1663 *** | 0.3701 *** | 0.0911 | 0.0135 | ||||

| House | 0.0712 | 0.0128 | 0.0473 | 0.0081 | −0.0402 | −0.0060 | −0.0170 | −0.0025 |

| Distance | −0.0545 | −0.0098 | −0.0748 | −0.0128 | −0.0637 | −0.0095 | −0.0623 | −0.0092 |

| Member | 0.3530 | 0.0635 | 0.3172 | 0.0542 | 0.3083 | 0.0462 | 0.2414 | 0.0357 |

| Purchase | 0.2378 | 0.0428 | 0.3056 | 0.0522 | 0.2938 | 0.0440 | 0.2728 | 0.0404 |

| Familiarity | 0.0437 | 0.0079 | 0.0826 | 0.0141 | 0.2340 | 0.0350 | 0.2394 | 0.0354 |

| Clean | 0.3027 | 0.0545 | 0.3715 * | 0.0635 * | 0.1258 | 0.0188 | 0.1384 | 0.0205 |

| Health | −0.1290 | −0.0232 | −0.1388 | −0.0237 | −0.2186 | −0.0327 | −0.1880 | −0.0278 |

| Satisfaction | −0.3560 ** | −0.0641 ** | −0.4280 ** | −0.0731 ** | −0.0402 | −0.0060 | −0.0626 | −0.0093 |

| Unsanitary | 0.0785 | 0.0141 | 0.0356 | 0.0061 | −0.2447 | −0.0366 | −0.2646 | −0.0391 |

| Relatives | 0.0505 | 0.0091 | 0.0569 | 0.0097 | 0.0537 | 0.0080 | 0.0537 | 0.0080 |

| Reformation | 1.5264 *** | 0.2747 *** | 1.6625 *** | 0.2840 *** | 1.4504 ** | 0.2172 ** | 1.3685 * | 0.2025* |

| Number of obs | 259 | 259 | 217 | 217 | ||||

| Wald chi2(16) | 37.66 | 45.77 | 30.99 | 40.91 | ||||

| Prob > chi2 | 0.0010 | 0.0050 | 0.0088 | 0.0025 | ||||

| Log pseudo-likelihood | −138.2769 | −132.7919 | −99.3171 | −98.3362 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lyu, X.; Wang, Z.; Wachenheim, C.; Zheng, S. Are Rural Residents Willing to Pay for Sanitation Improvements? Evidence from China’s Toilet Revolution. Agriculture 2025, 15, 821. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15080821

Lyu X, Wang Z, Wachenheim C, Zheng S. Are Rural Residents Willing to Pay for Sanitation Improvements? Evidence from China’s Toilet Revolution. Agriculture. 2025; 15(8):821. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15080821

Chicago/Turabian StyleLyu, Xinyang, Zhigang Wang, Cheryl Wachenheim, and Shi Zheng. 2025. "Are Rural Residents Willing to Pay for Sanitation Improvements? Evidence from China’s Toilet Revolution" Agriculture 15, no. 8: 821. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15080821

APA StyleLyu, X., Wang, Z., Wachenheim, C., & Zheng, S. (2025). Are Rural Residents Willing to Pay for Sanitation Improvements? Evidence from China’s Toilet Revolution. Agriculture, 15(8), 821. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15080821