Driving Mechanisms of the Integration of Ecological Farms and Rural Tourism: A Mixed Method Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

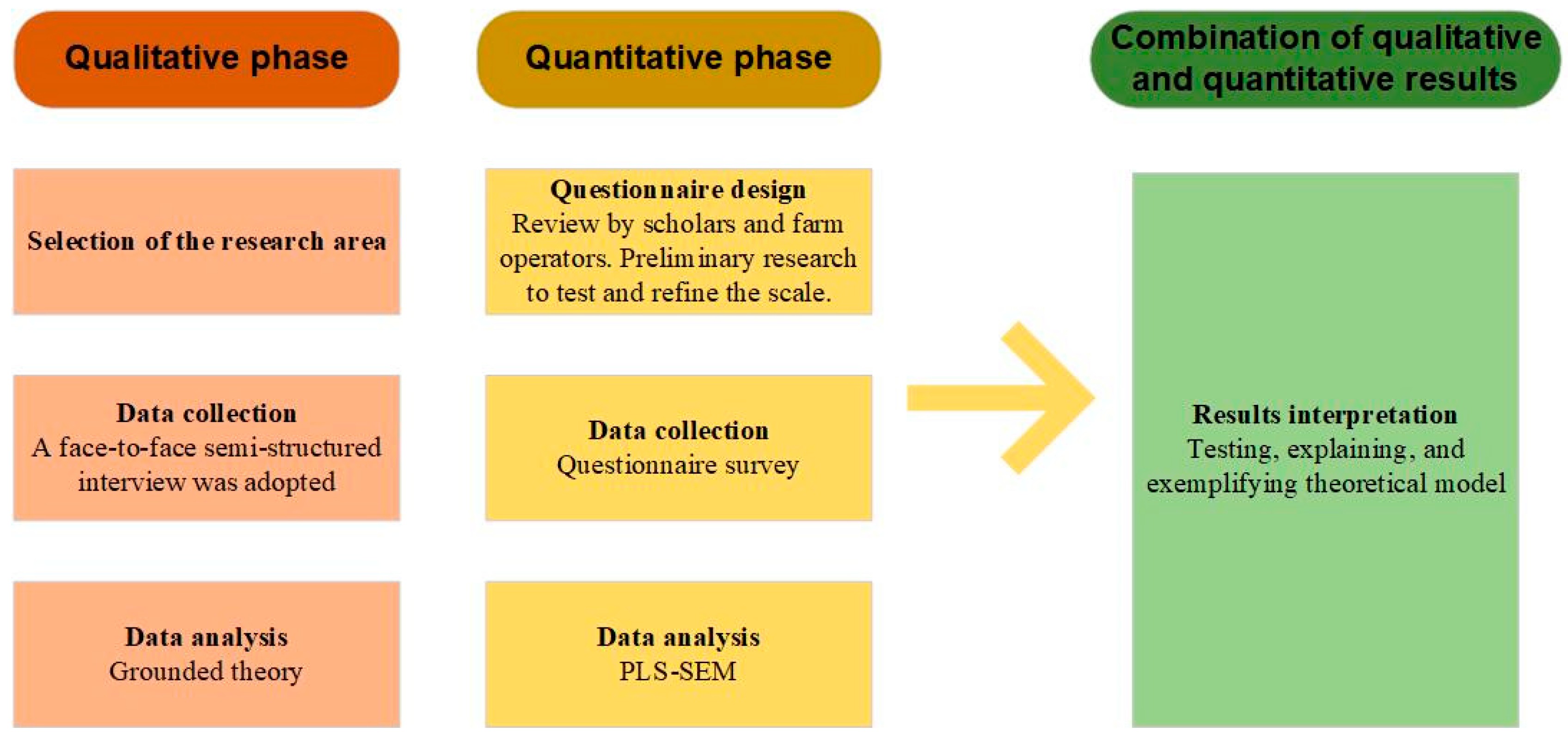

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Qualitative Research Based on GT

2.2.1. Data Collection

2.2.2. Coding

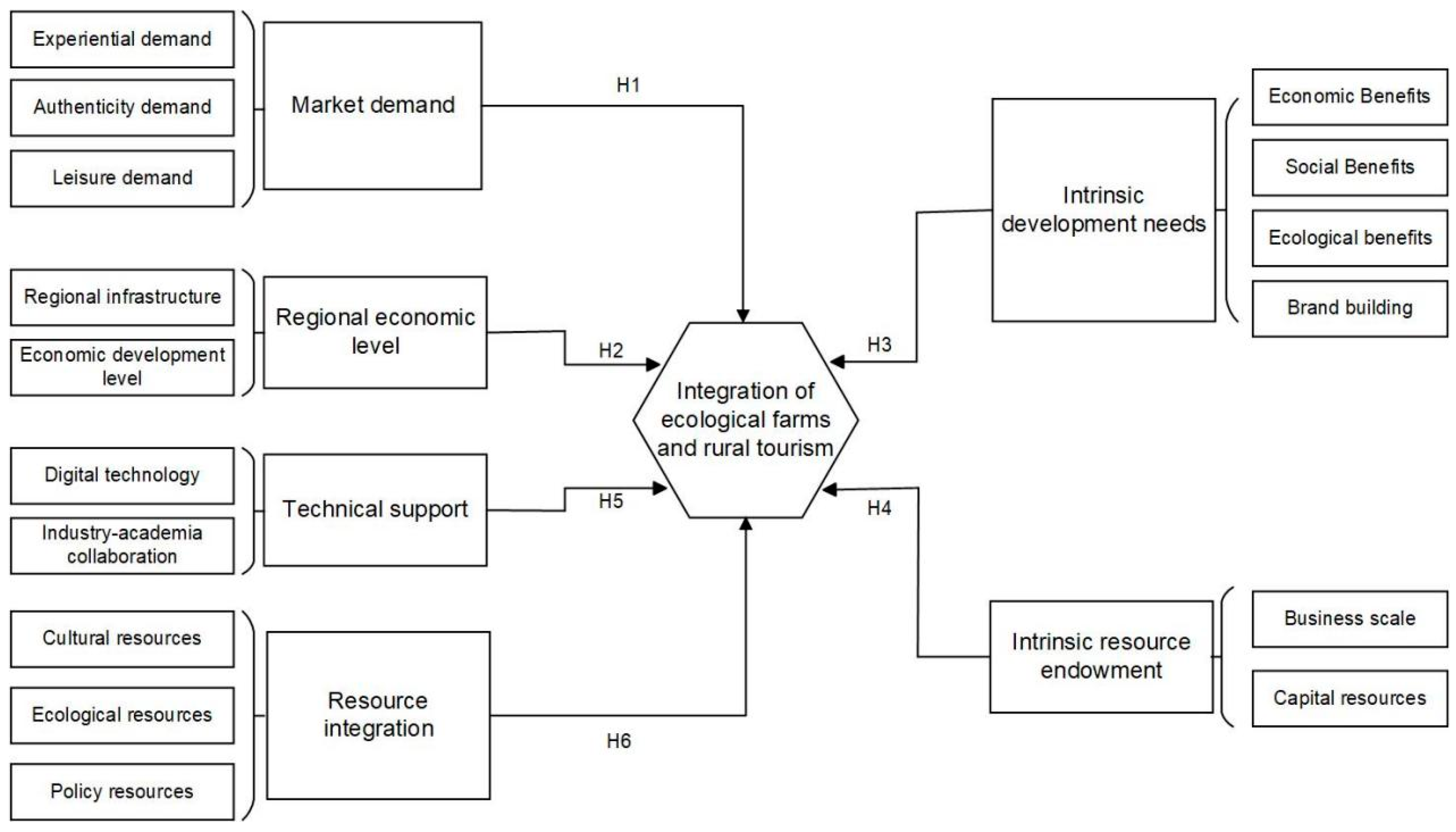

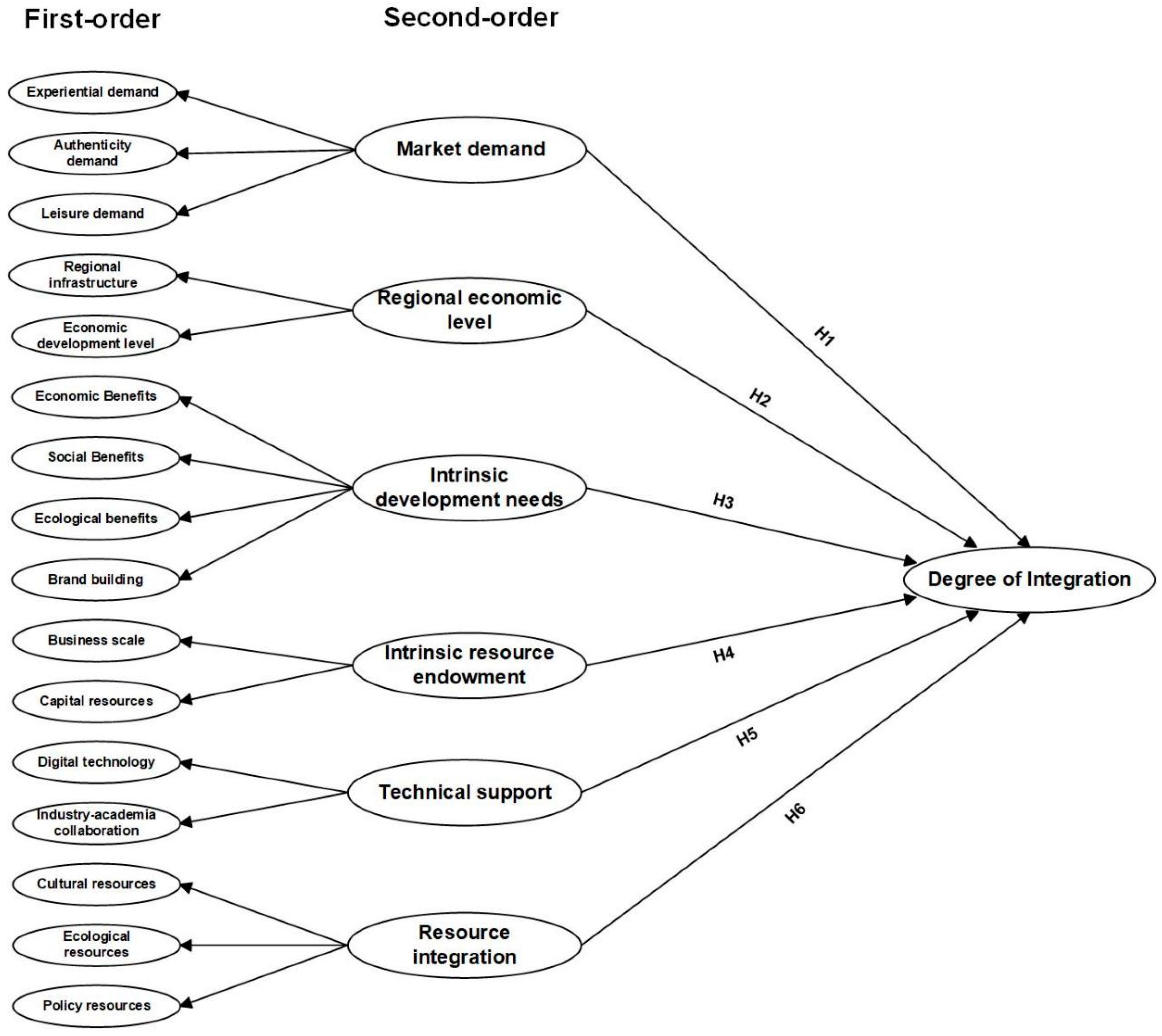

2.3. Quantitative Research Based on PLS-SEM

2.3.1. Questionnaire Development

2.3.2. Data Collection

3. Results

3.1. Results of GT Analyses

3.1.1. The Impact of Market Demand on the Integration of Ecological Farms and Rural Tourism

3.1.2. The Impact of the Regional Economic Level on the Integration of Ecological Farms and Rural Tourism

3.1.3. The Impact of Intrinsic Development Needs on the Integration of Ecological Farms and Rural Tourism

3.1.4. The Impact of Intrinsic Resource Endowments on the Integration of Ecological Farms and Rural Tourism

3.1.5. The Impact of Technical Support on the Integration of Ecological Farms and Rural Tourism

3.1.6. The Impact of Resource Integration on the Integration of Ecological Farms and Rural Tourism

3.2. PLS-SEM Analysis Results

3.2.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2.2. Research Model

3.2.3. Results of Model Evaluation

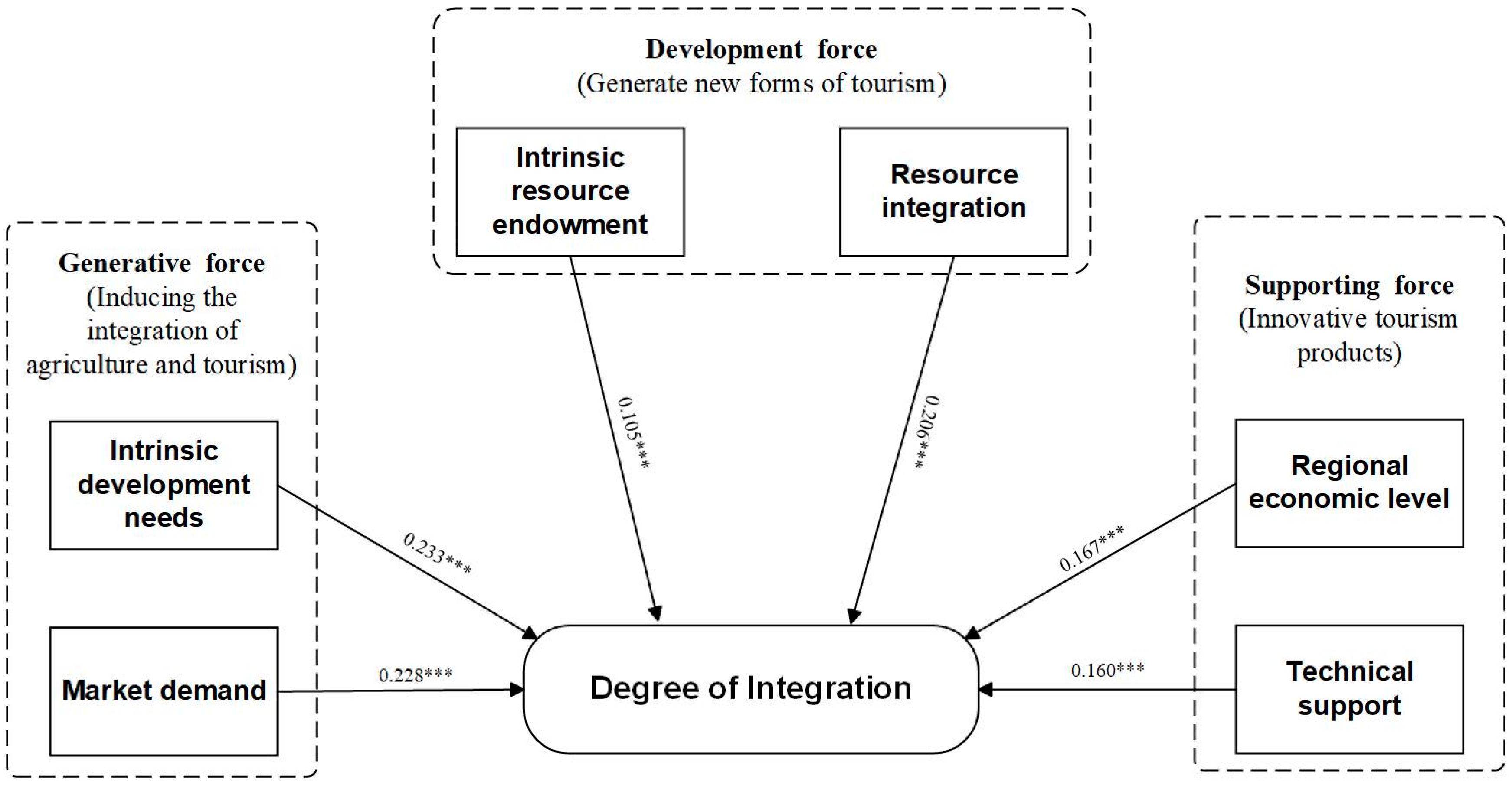

4. Discussion

4.1. Integration Mechanism Between the Ecological Farms and Rural Tourism

4.2. Impact on Literature

4.3. Impact on Practice

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GT | Grounded Theory |

| PLS-SEM | Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling |

| ED | Experiential Demand |

| AD | Authenticity Demand |

| LD | Leisure Demand |

| RI | Regional Infrastructure |

| EDL | Economic Development Level |

| EB | Economic Benefits |

| SB | Social Benefits |

| EB | Ecological Benefits |

| BB | Brand Building |

| BS | Business Scale |

| CaR | Capital Resources |

| DT | Digital Technology |

| IC | Industry-academia Collaboration |

| CuR | Cultural Resources |

| ER | Ecological Resources |

| PR | Policy Resources |

| DOI | Degree Of Integration |

Appendix A

| Interviewee | Interview Content |

|---|---|

| Ecological farm operator | ① Has this farm been integrated with rural tourism? What was the earliest reason for wanting to integrate with rural tourism? ② What do you think are the advantages of this farm in developing rural tourism? ③ What problems has this ecological farm encountered in the process of integrating with rural tourism? And what is your view on the future development trend of the integration of ecological farms and rural tourism? |

| Tourist | ① What was the main reason for coming to this ecological farm? ② What is your evaluation of this ecological farm? |

| Village cadre | ① Have you participated in the integration of ecological farms and rural tourism? ② What have you done specifically? |

| Member of a rural cooperative | ① Are tourism profits distributed according to the proportion of land owned by farmers? ② How can agricultural resources (such as organic agricultural products and idyllic landscapes) be transformed into tourism products? How can cooperatives mobilize the resources of farmers, such as land, labor, and traditional skills, to participate in tourism projects? ③ Has a regional alliance been formed with surrounding scenic spots and travel agencies? |

| Government employee | ① What is the current attitude of the government towards the integration of ecological farms and rural tourism? ② What specific support policies are currently in place? ③ What difficulties have been encountered in the implementation of these policies? |

References

- Hatan, S.; Fleischer, A.; Tchetchik, A. Economic valuation of cultural ecosystem services: The case of landscape aesthetics in the agritourism market. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 184, 107005. [Google Scholar]

- Rong-Da Liang, A. Considering the role of agritourism co-creation from a service-dominant logic perspective. Tour. Manag. 2017, 61, 354–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Barbieri, C.; Valdivia, C. Agricultural landscape preferences: Implications for agritourism development. J. Travel Res. 2014, 53, 366–379. [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri, C. Assessing the sustainability of agritourism in the US: A comparison between agritourism and other farm entrepreneurial ventures. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 252–270. [Google Scholar]

- Grillini, G.; Sacchi, G.; Streifeneder, T.; Fischer, C. Differences in sustainability outcomes between agritourism and non-agritourism farms based on robust empirical evidence from the tyrol/trentino mountain region. J. Rural Stud. 2023, 104, 103152. [Google Scholar]

- Lacombe, C.; Couix, N.; Hazard, L. Designing agroecological farming systems with farmers: A review. Agric. Syst. 2018, 165, 208–220. [Google Scholar]

- Andéhn, M.; L Espoir Decosta, J.P. Authenticity and product geography in the making of the agritourism destination. J. Travel Res. 2021, 60, 1282–1300. [Google Scholar]

- Phillip, S.; Hunter, C.; Blackstock, K. A typology for defining agritourism. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 754–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, C.G.; Barbieri, C.; Rich, S.R. Defining agritourism: A comparative study of stakeholders’ perceptions in missouri and north carolina. Tour. Manag. 2013, 37, 39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Flanigan, S.; Blackstock, K.; Hunter, C. Generating public and private benefits through understanding what drives different types of agritourism. J. Rural Stud. 2015, 41, 129–141. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Cai, J.; Sliuzas, R. Agro-tourism enterprises as a form of multi-functional urban agriculture for peri-urban development in china. Habitat Int. 2010, 34, 374–385. [Google Scholar]

- Lupi, C.; Giaccio, V.; Mastronardi, L.; Giannelli, A.; Scardera, A. Exploring the features of agritourism and its contribution to rural development in italy. Land Use Policy 2017, 64, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgroi, F.; Donia, E.; Mineo, A.M. Agritourism and local development: A methodology for assessing the role of public contributions in the creation of competitive advantage. Land Use Policy 2018, 77, 676–682. [Google Scholar]

- Arru, B.; Furesi, R.; Madau, F.A.; Pulina, P. Economic performance of agritourism: An analysis of farms located in a less favoured area in italy. Agric. Food Econ. 2021, 9, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, J.; Li, R.; Zhang, L.; Jing, Y. Spatially illustrating leisure agriculture: Empirical evidence from picking orchards in china. Land 2021, 10, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.; Fesenmaier, D.R.; Fesenmaier, J.; Van Es, J.C. Factors for success in rural tourism development. J. Travel Res. 2001, 40, 132–138. [Google Scholar]

- Ollenburg, C.; Buckley, R. Stated economic and social motivations of farm tourism operators. J. Travel Res. 2007, 45, 444–452. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Dou, X.; Li, J.; Cai, L.A. Analyzing government role in rural tourism development: An empirical investigation from china. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 79, 177–188. [Google Scholar]

- Pehin Dato Musa, S.F.; Chin, W.L. The role of farm-to-table activities in agritourism towards sustainable development. Tour. Rev. 2022, 77, 659–671. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, D.; Sun, D.; Wang, Z. Exploring the rural revitalization effect under the interaction of agro-tourism integration and tourism-driven poverty reduction: Empirical evidence for china. Land 2024, 13, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panyik, E.; Costa, C.; Rátz, T. Implementing integrated rural tourism: An event-based approach. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1352–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wetzels, M.; Odekerken-Schröder, G.; Van Oppen, C. Using PLS path modeling for assessing hierarchical construct models: Guidelines and empirical illustration. MIS Q. 2009, 33, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Valle, P.O.; Assaker, G. Using partial least squares structural equation modeling in tourism research: A review of past research and recommendations for future applications. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 695–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun Tie, Y.; Birks, M.; Francis, K. Grounded theory research: A design framework for novice researchers. SAGE Open Med. 2019, 7, 2105894927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birks, M.; Mills, J. Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Makri, C.; Neely, A. Grounded theory: A guide for exploratory studies in management research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2021, 20, 2119180822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory; Sage Publications: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Domi, S.; Belletti, G. The role of origin products and networking on agritourism performance: The case of tuscany. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 90, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Zheng, S. Coupling coordination between agriculture and tourism in the qinba mountain area: A case study of shanyang county, shanxi province. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 31859–31878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, G.; Timonen, V.; Conlon, C.; O Dare, C.E. Interviewing as a vehicle for theoretical sampling in grounded theory. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2021, 20, 1070791133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research Techniques; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Acun, V.; Yilmazer, S. Combining grounded theory (GT) and structural equation modelling (SEM) to analyze indoor soundscape in historical spaces. Appl. Acoust. 2019, 155, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timonen, V.; Foley, G.; Conlon, C. Challenges when using grounded theory: A pragmatic introduction to doing GT research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2018, 17, 1068568262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Chen, B. Rural tourism in china:‘root-seeking’and construction of national identity. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2024, 60, 141–151. [Google Scholar]

- Benitez, J.; Henseler, J.; Castillo, A.; Schuberth, F. How to perform and report an impactful analysis using partial least squares: Guidelines for confirmatory and explanatory is research. Inf. Manag. 2020, 57, 103168. [Google Scholar]

- Bachi, L.; Ribeiro, S.C.; Hermes, J.; Saadi, A. Cultural ecosystem services (CES) in landscapes with a tourist vocation: Mapping and modeling the physical landscape components that bring benefits to people in a mountain tourist destination in southeastern brazil. Tour. Manag. 2020, 77, 104017. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Zhu, K.; Liu, L.; Sun, X. Pollution-induced food safety problem in china: Trends and policies. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 703832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elands, B.H.; Lengkeek, J. The tourist experience of out-there-ness: Theory and empirical research. Forest Policy Econ. 2012, 19, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Wong, I.A.; Duan, X.; Chen, Y.V. Craving better health? Influence of socio-political conformity and health consciousness on goal-directed rural-eco tourism. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2021, 38, 511–526. [Google Scholar]

- Giaccio, V.; Giannelli, A.; Mastronardi, L. Explaining determinants of agri-tourism income: Evidence from italy. Tour. Rev. 2018, 73, 216–229. [Google Scholar]

- Tew, C.; Barbieri, C. The perceived benefits of agritourism: The provider’s perspective. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 215–224. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, Y.; Xu, C. Land consolidation and rural revitalization in china: Mechanisms and paths. Land Use Policy 2020, 91, 104379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastenholz, E.; Marques, C.P.; Carneiro, M.J. Place attachment through sensory-rich, emotion-generating place experiences in rural tourism. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 17, 100455. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Yao, Z.; Guo, Z. Willingness to pay and preferences for rural tourism attributes among urban residents: A discrete choice experiment in china. Econ. Anal. Policy 2023, 77, 460–471. [Google Scholar]

- Eusébio, C.; Carneiro, M.J.; Kastenholz, E.; Figueiredo, E.; Da Silva, D.S. Who is consuming the countryside? An activity-based segmentation analysis of the domestic rural tourism market in portugal. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2017, 31, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohorodnyk, V.; Finger, R. Envisioning the future of agri-tourism in ukraine: From minor role to viable farm households and sustainable regional economies. J. Rural Stud. 2024, 108, 103283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galluzzo, N. A quantitative analysis on romanian rural areas, agritourism and the impacts of european union’s financial subsidies. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 82, 458–467. [Google Scholar]

- Kanwal, S.; Rasheed, M.I.; Pitafi, A.H.; Pitafi, A.; Ren, M. Road and transport infrastructure development and community support for tourism: The role of perceived benefits, and community satisfaction. Tour. Manag. 2020, 77, 104014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouzi, Z.; Azadi, H.; Taheri, F.; Zarafshani, K.; Gebrehiwot, K.; Van Passel, S.; Lebailly, P. Organic farming and small-scale farmers: Main opportunities and challenges. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 132, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Robinson, G.M.; Bardsley, D.K.; Xue, Y.; Wang, B. Multifunctional agriculture in a peri-urban fringe: Chinese farmers’ responses to shifts in policy and changing socio-economic conditions. Land Use Policy 2023, 133, 106869. [Google Scholar]

- Paniccia, P.M.; Baiocco, S. Interpreting sustainable agritourism through co-evolution of social organizations. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Timothy, D.J.; Zhong, C.; Zhang, X. Influential factors in agrarian households’ engagement in rural tourism development. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2022, 44, 101009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandth, B.; Haugen, M.S. Farm diversification into tourism–implications for social identity? J. Rural Stud. 2011, 27, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Huang, H.; Sun, Y.; Li, Z.; Du, H. The evolutionary game in regulating non-agricultural farmland use within the integrated development of rural primary, secondary, and tertiary industries. Land 2024, 13, 1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzubi, A.A.; Galyna, K. Artificial intelligence and internet of things for sustainable farming and smart agriculture. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 78686–78692. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Z.; Wang, S.; Boussemart, J.; Hao, Y. Digital transition and green growth in chinese agriculture. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 181, 121742. [Google Scholar]

- Da Liang, A.R.; Nie, Y.Y.; Chen, D.J.; Chen, P. Case studies on co-branding and farm tourism: Best match between farm image and experience activities. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 42, 107–118. [Google Scholar]

- Khairabadi, O.; Sajadzadeh, H.; Mohamadianmansoor, S. Assessment and evaluation of tourism activities with emphasis on agritourism: The case of simin region in hamedan city. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 105045. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Chai, S.; Chen, J.; Phau, I. How was rural tourism developed in china? Examining the impact of china’s evolving rural tourism policies. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 28945–28969. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, X.; Wu, M.; Ma, L.; Wang, N. Rural finance, scale management and rural industrial integration. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2020, 12, 349–365. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, J.R. Multidimensional constructs in organizational behavior research: An integrative analytical framework. Organ. Res. Methods 2001, 4, 144–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, P.M.; Jarvis, C.B. The problem of measurement model misspecification in behavioral and organizational research and some recommended solutions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W.; Wen, Z.; Hau, K. Structural equation models of latent interactions: Evaluation of alternative estimation strategies and indicator construction. Psychol. Methods 2004, 9, 275. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Yuan, X.; Yuan, X.; Liu, S.; Guan, B.; Sun, J.; Chen, H. Evaluating the sustainability of rural complex ecosystems during the development of traditional farming villages into tourism destinations: A diachronic emergy approach. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 86, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brune, S.; Knollenberg, W.; Stevenson, K.T.; Barbieri, C.; Schroeder-Moreno, M. The influence of agritourism experiences on consumer behavior toward local food. J. Travel Res. 2021, 60, 1318–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.M.; Kubickova, M. Agritourism microbusinesses within a developing country economy: A resource-based view. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 17, 100460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomej, K.; Liburd, J.J. Sustainable accessibility in rural destinations: A public transport network approach. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 222–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cayla, J.; Maizi, N.; Marchand, C. The role of income in energy consumption behaviour: Evidence from french households data. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 7874–7883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapuz, M.C.M. The role of local community empowerment in the digital transformation of rural tourism development in the philippines. Technol. Soc. 2023, 74, 102308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, K.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Li, F.; Li, X. Push and pull in the sustainable development of ecological landscape and ecological resources: A dual perceptions of tourists and service staff. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 31, 2402–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godin, B.; Lane, J.P. Pushes and pulls: Hi (s) tory of the demand pull model of innovation. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 2013, 38, 621–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skuras, D.; Petrou, A.; Clark, G. Demand for rural tourism: The effects of quality and information. Agric. Econ. 2006, 35, 183–192. [Google Scholar]

- Fleischer, A.; Tchetchik, A. Does rural tourism benefit from agriculture? Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 493–501. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, G.; Chen, W. Agritourism experience value cocreation impact on the brand equity of rural tourism destinations in china. Tour. Rev. 2023, 78, 1315–1335. [Google Scholar]

- Pesonen, J.; Komppula, R. Rural wellbeing tourism: Motivations and expectations. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2010, 17, 150–157. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.; Wang, J.; Gao, X.; Wang, Y.; Choi, B.R. Rural tourism: Does it matter for sustainable farmers’ income? Sustainability 2021, 13, 10440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Hung, K. Poverty alleviation via tourism cooperatives in china: The story of yuhu. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 26, 879–906. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Yang, R.; Chen, M.; Su, C.J.; Zhi, Y.; Xi, J. Effects of rural revitalization on rural tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 47, 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, C.W.; Goo, J.; Huang, C.D.; Nam, K.; Woo, M. Improving travel decision support satisfaction with smart tourism technologies: A framework of tourist elaboration likelihood and self-efficacy. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2017, 123, 330–341. [Google Scholar]

- Di Domenico, M.; Miller, G. Farming and tourism enterprise: Experiential authenticity in the diversification of independent small-scale family farming. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 285–294. [Google Scholar]

- Fotiadis, A.; Yeh, S.; Huan, T.T. Applying configural analysis to explaining rural-tourism success recipes. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1479–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretty, J. Intensification for redesigned and sustainable agricultural systems. Science 2018, 362, eaav0294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z. Quantifying the industrial development modes and their capability of realizing the ecological value in rural china. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 203, 123386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, K.; Moscardo, G. Encouraging sustainability beyond the tourist experience: Ecotourism, interpretation and values. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 22, 1175–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Selective Coding (Core Category) | Axial Coding (Initial Category) | Open Coding (Initial Concept) | Example of An Original Statement | Serial Number | Reference Points |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Market demand | Leisure need | Leisure vacation | “It’s the weekend, it’s hard to take a day off, bring the family to fish, breathe fresh air, don’t want to do anything, just come to escape the heat”. | T18 | s153 |

| Health and wellness | “It’s really cool, with high oxygen ions and such good tea, wellness at its best, and I’ve rented apartments for wellness”. | T18 | s161 | ||

| Sightseeing experience | “Look, there are terraces in front of us, tea here, and the scenery is stunning, especially cozy with the clouds after the rain”. | T18 | s166 | ||

| Experiential need | Educational experience | “We have a farming museum here, and we also let the students experience digging sweet potatoes, so that they can understand farming culture”. | T18 | s153 | |

| Production experience | “When the rice flowers bloom, many tourists come to the fields to catch their own fish to eat, which is very delicious”. | T5 | s41 | ||

| Gourmet experience | “The specialty of our farm is hot pot, so we use this specialty and combine it with the loquat garden to create a hot pot loquat garden. At night, our place is lit up with flashing lights, and people come here to drink and enjoy the night view. When the loquats are ripe, you can also pick them while eating hot pot, which will increase the bond between you”. | T3 | s40 | ||

| Authentic need | Avoidance experience | “It’s so comfortable here, a temporary escape from the hustle and bustle of the city”. | T18 | s193 | |

| Authentic | “Our terraced fields allow us to experience the original ecological environment”. | T1 | s190 |

| Main Variable | Sub-Variable | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Market demand | Experiential demand | The development of tourism projects at this ecological farm addresses the recreational needs of visitors. (ED1) |

| The development of tourism projects at this ecological farm addresses the educational needs of visitors. (ED2) | ||

| The development of tourism projects at this ecological farm meets the aesthetic needs of visitors. (ED3) | ||

| Authenticity demand | The development of tourism projects at this ecological farm addresses the tourists’ desire to escape the hustle and bustle of urban life. (AD1) | |

| The development of tourism projects at this ecological farm meets the tourists’ yearning for a sense of place. (AD2) | ||

| The development of tourism projects at this ecological farm caters to the visitors’ desire for authenticity and rustic experiences. (AD3) | ||

| Leisure demand | The development of tourism projects at this ecological farm meets the leisure and vacation needs of visitors. (LD1) | |

| The development of tourism projects at this ecological farm addresses the health and wellness needs of visitors. (LD2) | ||

| Regional economic level | Regional infrastructure | The surrounding rural roads of this ecological farm facilitate the integration of the ecological farm with rural tourism. (RI1) |

| The strong network signal of this ecological farm facilitates the integration of ecological farming and rural tourism. (RI2) | ||

| The good network signal along the route to this ecological farm can facilitate the integration of the ecological farm with rural tourism. (RI3) | ||

| Economic development level | The high income of local permanent residents can facilitate the integration of ecological farms and rural tourism. (EDL1) | |

| The high level of leisure consumption among local permanent residents can promote the integration of ecological farms and rural tourism. (EDL2) | ||

| This ecological farm, being in close proximity to the urban area, facilitates the integration of ecological farming with rural tourism. (EDL3) | ||

| Intrinsic development needs | Economic benefits | The development of rural tourism projects at this ecological farm enables the farm to achieve greater profitability. (EcB1) |

| The development of rural tourism projects by this ecological farm enables farmers to achieve increased income. (EcB2) | ||

| The development of rural tourism projects at this ecological farm has enabled the diversification of its operations. (EcB3) | ||

| The development of rural tourism projects by this ecological farm enhances the value of agricultural products by transforming the production landscape of ecological farm products. (EcB4) | ||

| Social benefits | This ecological farm can provide job opportunities for local farmers. (SB1) | |

| The development of rural tourism projects by this ecological farm has enabled local farmers to obtain greater income. (SB2) | ||

| The development of rural tourism projects by this ecological farm enables visitors to taste and purchase fresh and safe organic food. (SB3) | ||

| Ecological benefits | The development of rural tourism projects at this ecological farm enhances soil conditions through the improvement of cultivation methods. (ElB1) | |

| The development of rural tourism projects at this ecological farm facilitates the establishment of an ecological circulation system within the farm. (ElB2) | ||

| This ecological farm develops rural tourism projects to enhance the local living environment. (ElB3) | ||

| Brand building | This ecological farm utilizes news media to promote the integration of agriculture and tourism through reporting. (BB1) | |

| This ecological farm collaborates with major tourism platforms to promote agricultural products. (BB2) | ||

| This ecological farm participates in promotional activities for agricultural products, including tourism products. (BB3) | ||

| This ecological farm participates in tourism conferences and other events to introduce its agricultural products to customers. (BB4) | ||

| This ecological farm enhances the quality management of agricultural products through the development of tourism projects. (BB5) | ||

| This ecological farm develops tourism projects to enhance farmers’ service awareness. (BB6) | ||

| Intrinsic resource endowment | Business scale | The land scale of this ecological farm can support the development of rural tourism. (BS1) |

| The agricultural output of this ecological farm can meet the demand for picking and purchasing by tourists engaged in rural tourism. (BS2) | ||

| The annual revenue of this ecological farm can support the development of rural tourism. (BS3) | ||

| Capital resources | The funds raised by this ecological farm can support the development of rural tourism. (CaR1) | |

| The operator of this ecological farm has invested sufficient capital for the development of rural tourism. (CaR2) | ||

| The investment ratio of external funding to self-financing in this ecological farm is appropriate for rural tourism development. (CaR3) | ||

| Technical support | Digital technology | This ecological farm currently applies advanced agricultural production information technologies, such as precision irrigation and remote sensing technology, in the development of tourism products. (DT1) |

| This ecological farm currently employs advanced digital technologies for measuring temperature, humidity, and other production-related parameters in the development of tourism products. (DT2) | ||

| The tourism information technologies mastered by this ecological farm, such as the monitoring and forecasting system for tourist numbers and the online booking system, facilitate the development of tourism products. (DT3) | ||

| This ecological farm possesses its own live streaming technology, which can facilitate the development of tourism products. (DT4) | ||

| Industry-academia collaboration | This ecological farm collaborates with research institutes and universities on agricultural technology. (IC1) | |

| This ecological farm collaborates with research institutes and universities for the development of tourism products. (IC2) | ||

| Resource integration | Cultural resources | The folk customs of the location of this ecological farm can facilitate the integration with rural tourism. (CuR1) |

| The cultural techniques of the location of this ecological farm can facilitate the integration with rural tourism. (CuR2) | ||

| The folk art present at the site of this ecological farm can facilitate the integration with rural tourism. (CuR3) | ||

| The traditional cuisine of the location of this ecological farm can promote the integration with rural tourism. (CuR4) | ||

| Ecological resources | The biodiversity surrounding this ecological farm can facilitate the integration of rural tourism. (ER1) | |

| The ecological quality surrounding this ecological farm can facilitate the integration with rural tourism. (ER2) | ||

| The ecological environment protection at the site of this ecological farm can facilitate the integration with rural tourism. (ER3) | ||

| Policy resources | The existing government financial subsidy policies for the integration of agriculture and tourism can promote the convergence of ecological farms and rural tourism. (PR1) | |

| The existing financial loan policies for the integration of agriculture and tourism are well-established and can promote the convergence of ecological farms and rural tourism. (PR2) | ||

| The existing tax reduction policies for the integration of agriculture and tourism can effectively promote the convergence of ecological farms and rural tourism. (PR3) | ||

| The existing certification system enhances the integration of ecological farms and rural tourism. (PR4) | ||

| The existing land transfer policies are well-structured and can facilitate the integration of ecological farms and rural tourism. (PR5) | ||

| Degree of Integration | This ecological farm promotes mutual enhancement, win-win benefits, and balanced development with rural tourism. (DOI1) | |

| The tourism and leisure value of this ecological farm has been explored. (DOI2) | ||

| The ecological tourism products in this region have become more diversified and enriched due to the development of ecological farms. (DOI3) |

| Characteristic | Description | Number | Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 935 | 89.82 |

| Female | 106 | 10.18 | |

| Education | High school and below | 295 | 28.34 |

| Associate degree | 136 | 13.06 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 587 | 56.39 | |

| Postgraduate degree | 23 | 2.21 | |

| Age | ≤40 | 42 | 4.03 |

| 41–55 | 581 | 55.81 | |

| 56–65 | 334 | 32.08 | |

| >65 | 84 | 8.07 | |

| Years of management operation | Within 1 year | 42 | 4.03 |

| 1–3 years | 146 | 14.02 | |

| 4–6 years | 230 | 22.09 | |

| 6–9 years | 529 | 50.82 | |

| Over 9 years | 94 | 9.03 | |

| Total | 1041 | 100.00 |

| First Order | Items | Loadings | CA | CR | AVE | Second Order | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ED | ED1 | 0.842 | 0.783 | 0.873 | 0.697 | Market demand (MD) | 0.843 | 0.643 |

| ED2 | 0.845 | |||||||

| ED3 | 0.818 | |||||||

| AD | AD1 | 0.844 | 0.784 | 0.874 | 0.699 | |||

| AD2 | 0.842 | |||||||

| AD3 | 0.822 | |||||||

| LD | LD1 | 0.882 | 0.742 | 0.886 | 0.795 | |||

| LD2 | 0.901 | |||||||

| RI | RI1 | 0.844 | 0.788 | 0.876 | 0.702 | Regional economic level (REL) | 0.843 | 0.729 |

| RI2 | 0.838 | |||||||

| RI3 | 0.832 | |||||||

| EDL | EDL1 | 0.876 | 0.836 | 0.901 | 0.753 | |||

| EDL2 | 0.870 | |||||||

| EDL3 | 0.857 | |||||||

| EcB | EcB1 | 0.833 | 0.844 | 0.895 | 0.681 | Intrinsic development needs (IDN) | 0.876 | 0.638 |

| EcB2 | 0.833 | |||||||

| EcB3 | 0.794 | |||||||

| EcB4 | 0.841 | |||||||

| SB | SB1 | 0.878 | 0.854 | 0.911 | 0.774 | |||

| SB2 | 0.889 | |||||||

| SB3 | 0.873 | |||||||

| ElB | ElB1 | 0.868 | 0.833 | 0.900 | 0.749 | |||

| ElB2 | 0.871 | |||||||

| ElB3 | 0.859 | |||||||

| BB | BB1 | 0.812 | 0.844 | 0.912 | 0.633 | |||

| BB2 | 0.801 | |||||||

| BB3 | 0.785 | |||||||

| BB4 | 0.833 | |||||||

| BB5 | 0.763 | |||||||

| BB6 | 0.776 | |||||||

| BS | BS1 | 0.857 | 0.823 | 0.894 | 0.739 | Intrinsic resource endowment (IRE) | 0.835 | 0.717 |

| BS2 | 0.857 | |||||||

| BS3 | 0.864 | |||||||

| CaR | CaR1 | 0.833 | 0.780 | 0.872 | 0.695 | |||

| CaR2 | 0.839 | |||||||

| CaR3 | 0.829 | |||||||

| DT | DT1 | 0.857 | 0.861 | 0.906 | 0.706 | Technical support (TS) | 0.819 | 0.697 |

| DT2 | 0.854 | |||||||

| DT3 | 0.834 | |||||||

| DT4 | 0.816 | |||||||

| IC | IC1 | 0.874 | 0.702 | 0.870 | 0.770 | |||

| IC2 | 0.881 | |||||||

| CuR | CuR1 | 0.850 | 0.840 | 0.893 | 0.675 | Resource integration (ReI) | 0.838 | 0.634 |

| CuR2 | 0.826 | |||||||

| CuR3 | 0.813 | |||||||

| CuR4 | 0.798 | |||||||

| ER | ER1 | 0.831 | 0.763 | 0.864 | 0.679 | |||

| ER2 | 0.828 | |||||||

| ER3 | 0.813 | |||||||

| PR | PR1 | 0.806 | 0.858 | 0.898 | 0.637 | |||

| PR2 | 0.792 | |||||||

| PR3 | 0.817 | |||||||

| PR4 | 0.793 | |||||||

| PR5 | 0.783 | |||||||

| DOI | DOI1 | 0.859 | 0.790 | 0.877 | 0.704 | |||

| DOI2 | 0.817 | |||||||

| DOI3 | 0.841 | |||||||

| AD | BB | BS | CaR | CuR | DOI | DT | ED | EDL | ER | EcB | ElB | IC | LD | PR | RI | SB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD | 0.836 | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| BB | 0.203 | 0.796 | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| BS | 0.181 | 0.186 | 0.859 | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| CaR | 0.139 | 0.177 | 0.435 | 0.833 | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| CuR | 0.148 | 0.148 | 0.131 | 0.184 | 0.822 | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| DOI | 0.367 | 0.338 | 0.319 | 0.252 | 0.357 | 0.839 | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| DT | 0.202 | 0.146 | 0.211 | 0.192 | 0.192 | 0.35 | 0.84 | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| ED | 0.469 | 0.148 | 0.144 | 0.118 | 0.178 | 0.34 | 0.183 | 0.835 | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| EDL | 0.211 | 0.131 | 0.173 | 0.157 | 0.154 | 0.32 | 0.205 | 0.126 | 0.868 | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| ER | 0.147 | 0.126 | 0.102 | 0.122 | 0.48 | 0.305 | 0.214 | 0.172 | 0.162 | 0.824 | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| EcB | 0.155 | 0.468 | 0.158 | 0.152 | 0.14 | 0.321 | 0.118 | 0.159 | 0.116 | 0.099 | 0.825 | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| ElB | 0.192 | 0.518 | 0.176 | 0.18 | 0.197 | 0.364 | 0.164 | 0.183 | 0.145 | 0.144 | 0.534 | 0.866 | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| IC | 0.167 | 0.1 | 0.192 | 0.195 | 0.156 | 0.31 | 0.431 | 0.204 | 0.128 | 0.113 | 0.135 | 0.117 | 0.878 | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| LD | 0.457 | 0.162 | 0.174 | 0.135 | 0.18 | 0.39 | 0.17 | 0.433 | 0.189 | 0.181 | 0.185 | 0.189 | 0.179 | 0.891 | □ | □ | □ |

| PR | 0.124 | 0.092 | 0.132 | 0.167 | 0.474 | 0.314 | 0.151 | 0.162 | 0.183 | 0.459 | 0.089 | 0.175 | 0.115 | 0.164 | 0.798 | □ | □ |

| RI | 0.186 | 0.125 | 0.208 | 0.154 | 0.178 | 0.359 | 0.252 | 0.178 | 0.456 | 0.161 | 0.141 | 0.213 | 0.158 | 0.191 | 0.192 | 0.838 | □ |

| SB | 0.172 | 0.532 | 0.156 | 0.135 | 0.16 | 0.354 | 0.15 | 0.169 | 0.154 | 0.123 | 0.543 | 0.551 | 0.109 | 0.17 | 0.092 | 0.158 | 0.88 |

| □ | AD | BB | BS | CaR | CuR | DOI | DT | ED | EDL | ER | EcB | ElB | IC | LD | PR | RI | SB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| BB | 0.243 | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| BS | 0.225 | 0.219 | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| CaR | 0.178 | 0.214 | 0.542 | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| CuR | 0.181 | 0.172 | 0.158 | 0.226 | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| DOI | 0.465 | 0.404 | 0.396 | 0.32 | 0.438 | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| DT | 0.245 | 0.166 | 0.251 | 0.234 | 0.227 | 0.425 | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| ED | 0.597 | 0.178 | 0.179 | 0.151 | 0.219 | 0.432 | 0.221 | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| EDL | 0.26 | 0.153 | 0.209 | 0.194 | 0.183 | 0.393 | 0.242 | 0.157 | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| ER | 0.19 | 0.152 | 0.129 | 0.158 | 0.598 | 0.394 | 0.264 | 0.22 | 0.204 | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| EcB | 0.189 | 0.541 | 0.19 | 0.187 | 0.165 | 0.391 | 0.137 | 0.195 | 0.138 | 0.123 | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| ElB | 0.237 | 0.602 | 0.212 | 0.223 | 0.236 | 0.448 | 0.194 | 0.227 | 0.173 | 0.18 | 0.634 | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| IC | 0.225 | 0.127 | 0.253 | 0.262 | 0.204 | 0.416 | 0.555 | 0.276 | 0.168 | 0.155 | 0.174 | 0.152 | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| LD | 0.598 | 0.199 | 0.223 | 0.177 | 0.228 | 0.507 | 0.213 | 0.565 | 0.239 | 0.241 | 0.234 | 0.24 | 0.248 | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| PR | 0.15 | 0.105 | 0.157 | 0.203 | 0.557 | 0.379 | 0.176 | 0.198 | 0.216 | 0.566 | 0.104 | 0.207 | 0.149 | 0.206 | □ | □ | □ |

| RI | 0.236 | 0.15 | 0.258 | 0.196 | 0.219 | 0.455 | 0.306 | 0.226 | 0.562 | 0.207 | 0.173 | 0.263 | 0.213 | 0.251 | 0.233 | □ | □ |

| SB | 0.209 | 0.609 | 0.185 | 0.166 | 0.191 | 0.431 | 0.175 | 0.205 | 0.182 | 0.153 | 0.637 | 0.652 | 0.141 | 0.212 | 0.107 | 0.192 | □ |

| Hypothesis | Relationship | Path Coefficient (β) | p Values | Result | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | MD→DOI | 0.228 | 0.000 | Supported | 0.453 |

| H2 | REL→DOI | 0.167 | 0.000 | Supported | |

| H3 | IDN→DOI | 0.233 | 0.000 | Supported | |

| H4 | IRE→DOI | 0.105 | 0.000 | Supported | |

| H5 | TS→DOI | 0.160 | 0.000 | Supported | |

| H6 | ReI→DOI | 0.206 | 0.000 | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xiao, X.; Xiang, P.; Wang, H.; Xia, M. Driving Mechanisms of the Integration of Ecological Farms and Rural Tourism: A Mixed Method Study. Agriculture 2025, 15, 764. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15070764

Xiao X, Xiang P, Wang H, Xia M. Driving Mechanisms of the Integration of Ecological Farms and Rural Tourism: A Mixed Method Study. Agriculture. 2025; 15(7):764. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15070764

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiao, Xia, Pingan Xiang, Haisong Wang, and Maosen Xia. 2025. "Driving Mechanisms of the Integration of Ecological Farms and Rural Tourism: A Mixed Method Study" Agriculture 15, no. 7: 764. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15070764

APA StyleXiao, X., Xiang, P., Wang, H., & Xia, M. (2025). Driving Mechanisms of the Integration of Ecological Farms and Rural Tourism: A Mixed Method Study. Agriculture, 15(7), 764. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15070764